Raúl Martínez Rodríguez, Fernando Galán del Río

Introduction

Nowadays, muscle injuries are among the most common sports injuries suffered by athletes, accounting for up to 10–55% of all acute sports-related injuries (Ekstrand et al. 2011). Furthermore, recurrence rates for muscle strains are high, between 16% and 30%. It is well known that recurrent injuries lead to longer absences from competition than the average injury (Mueller-Wohlfahrt et al. 2013). Different modifiable risk factors to prevent injury recurrence have been recommended, including avoidance of the disproportionate development of a fibrotic scar during muscle healing (Opar et al. 2012, Järvinen et al. 2005, Baoge et al. 2012).

The regeneration of the injured myofibers and the formation of a connective tissue scar between the stumps, are processes that simultaneously compete and co-work (Järvinen et al. 2005). As therapists, we need to appreciate the factors that may influence these parallel processes. Research suggests that the mechanical environment during muscle healing is a key feature. For instance, it is known that persistent scarring may increase the overall mechanical stiffness of the myofibrous tissue it replaces. It may also hinder potential muscle regeneration and, ultimately, lead to an incomplete functional recovery that includes changes in muscle tissue lengthening mechanisms, and in eccentric strength (Silder et al. 2008).

In sports medicine, diagnostic and therapeutic processes need to be optimized in order to minimize absences from sport, and to reduce high injury recurrence rates. To achieve this, it is necessary for modifiable risk factors to be recognized and analyzed, including, but not limited to, insufficient warm-up, muscle fatigue, muscle strength imbalance, neuromuscular inhibition, poor motor control of the pelvic and trunk muscles, limited flexibility, or premature return to active sport (Freckleton et al. 2013, McCall et al. 2015). In addition, appropriate manual control of the myofascial tissue’s mechanical properties, and suitable handling of mechanical loads through different training programs, can enhance the development of more regenerative and less recurrent functional scars.

However, a new question arises: are we able to control this balance during the repair process? The mechanobiology of muscle, has been comprehensively reviewed and established. This focuses particular attention on the benefits of early mechanical loading, set in the improved alignment of regenerating myotubes. It also pays attention to faster regeneration, as well as to atrophy minimization of surrounding myotubes (Khan & Scott 2009). Nevertheless, the high rate of recurrent injuries suggests that the prevailing understanding of potential risk factors related to muscle re-injury, and its detection, is not adequate. In this context, it is necessary to highlight the importance of the tensional environment, related to the high–low tension of the ‘non-contractile’ structures, and the role of the mechanical properties of muscle fascia in regeneration and reparation processes, during muscle healing.

This chapter proposes a manual approach, based on the intentional alteration of the mechanical environment (manual matrix remodeling) in each of the three phases of muscle healing: degeneration and inflammation, muscle regeneration and fibrosis or remodeling. It should be recognized that the last two phases usually closely overlap.

The authors of this chapter have developed a scar modeling technique that attempts to reverse the matrix state from high to low tension, a process that is decisive in the physiopathology and healing process of myofascial injuries, with controlled mechanical stimuli

through the combined use of torsion, shear, traction, axial and compressive vectors on scar tissue.

Normal muscle and muscular connective tissue relationships

Muscular tissue has traditionally been studied by the conventional precepts of descriptive anatomy, at the expense of the study of the fascial tissues, considered from the beginnings of anatomical study as a surrounding tissue that lacks a relevant function. The term ‘myofascia’ refers to the skeleton of muscle fibers, or musculoskeletal cell matrix, including the epimysium, perimysium and endomysium. The advancement of scientific knowledge of this tissue in the last thirty years has enabled us to understand the relevance that the intra-, inter- and extramuscular connective tissue has in the mechanotransduction and transmission of forces to the skeleton through connective tissues linking the skeletal muscle to fascial structures and tendon. Thus, it is worth mentioning that chronic loading leads both to increased collagen turnover as well as, dependent on the type of collagen being considered, some degree of net collagen synthesis. These changes modify the mechanical properties and the viscoelastic characteristics of the muscular fascia, decreasing its stress susceptibility, and likely making it more load resistant (Kjaer 2004).

Nevertheless, the enthusiasm that has been brought about by this emerging paradigm shift may be possibly leading us to make the same mistakes we made when putting stress on the study of the fascia by anatomically and functionally separating it from the muscular tissue. In sport medicine and functional anatomy, it is essential to understand the bidirectional interaction between these two tissues whose histologic compositions differ.

Relevance of muscle–connective tissue interfaces in mechanotransduction of skeletal muscle

Thanks to electron microscopy, and to selective digestion–maceration techniques, as well as to studying anatomy from a less analytic and more functional point of view, we can acknowledge the intimate functional relationships between the intra-, inter- and extramuscular connective tissue, and the muscular tissue. In short, muscular tissue is closely bound to muscle fiber through several continuous connective bows. The mechanically competent links that transmit external forces to the muscle cell surface and underlying cytoskeleton, through integrins and dystrophin–glycoprotein complexes, derive from the interfascial trabecular system of muscular connective tissue (Järvinen et al. 2005, Passerieux et al. 2006, Passerieux et al. 2007). These focal adhesion complexes are of great importance during the connection of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and molecular myofibers. Strong linkages such as these provide stability to the muscular fiber’s sarcolemma, and actively participate in the bidirectional mechanical communication between the connective tissue and the muscle. In addition, many of these linkages are to be found in the myofascial areas that hold the greatest mechanical tension. There are a large number of these close to the musculotendinous junctions, due to an intertwined architecture that provides them with a larger distribution area (Kääriäinen et al. 2000b).

Relevance of mechanical properties in mechanotransduction of skeletal muscle

Curiously the majority of these focal adhesion complexes, skeletal muscle cell nuclei and satellite cells, are located in the most mechanosensitive areas, as the interactive interface between the basal lamina and the skeletal muscle sarcolemma (Kääriäinen et al. 2000a). Thus, mechanical information is received by the nucleus in a more rapid and efficient way, thanks to its peripheral location in the areas subject to more fascial pretension. Interestingly, associations have been made between the growth of the muscle, increased protein synthesis, activation of satellite cells, and release of growth factors and mechanical signaling, related to physical activity and loading (Khan & Scott 2009). However, although skeletal muscle is able to generate external mechanical forces, their development

and maintenance not only depends on contraction forces, but also on the relationship between musculoskeletal cell matrix and muscle cells. In other words, mechanical properties of connective tissue and fascial pretension condition and enhance the bidirectional signaling mentioned above.

Myofascial injury repair

Muscle regeneration and repair by connective tissue

Regeneration implies the substitution of a damaged tissue by another one with histologic characteristics that are identical. Unfortunately, only bones, corneas, livers and fingertips can go through a total regeneration

process. The muscle cell is long, multinucleated and amitotic with no ability to regenerate, per se

. In any case, satellite cells, that are physically located between the muscle cells’ basal membrane and sarcolemma, remain in a quiescence state until they are activated by chemical or/and mechanical signaling (Järvinen et al. 2007).

Satellite cells are essential for skeletal muscle regeneration since they are able to activate, divide and change into myoblasts and finally into myotubes, that regenerate the injured muscle by fusing with healthy muscle fibers (Järvinen et al. 2005). Nevertheless, unlike rodents and other small animals, the repair process result in humans often consists of an excessive proliferation of collagen and fibrous tissue deposition, with a variable amount of regenerated and functional fibers. The scar is of course indispensable to the creation of a scaffold and anchorage, that helps to keep the stumps together, and thus able to withstand any external forces applied to the muscle (Järvinen et al. 2005).

Role of mechanical environment in repair process after muscle injury

There are different factors that might decisively condition these concomitant processes. When a tissue is damaged, the disruption of normal tissue integrity produces a biomechanical cascade that includes the following events, among many others: the activation of satellite cells that are the primary stem cell responsible for regenerating muscle, and the release of several ECM growth factors that immediately start the repair process (Järvinen et al, 2007).

Tissue responses to injury not only depend on chemical signaling, but also on the mechanical environment, since mechanical tension critically determines cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, migration, and development (Katsumi et al. 2005). It is interesting to note the experiments of Engler et al. (2006) who found that, depending on the biomechanical properties of the substrate, mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into neural, muscular, or bony cells. This demonstrated the strong effect of local mechanics on progenitor cells. Specifically, in muscle healing, the conjunctive presence of external mechanical stress and tissue stiffness (high-tension matrix), as well as active transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), is essential to convert fibroblasts into contractile myofibroblasts. These last contribute to the reconstruction of injured tissue by secreting new extracellular matrices, and by exerting high contractile force (Hinz 2007, Lieber & Ward 2013). Interestingly, research findings suggest that tissue stiffness and myofibroblast contractile forces partly control TGF-β1 activation (Hinz 2009). In other words, the rapid onset, and excessive proliferation and activation of fibroblasts in a mechanically rigid environment, might decisively lead the regenerative process towards an excessive concentration of connective tissue scarring in the gap between the ruptured muscle stumps and the nearby area. Moreover, the fibrotic scar might produce a physical barrier that restricts the advancement of myotubes, trying to reconnect and complete each fiber’s regeneration. Likewise, the myotubes’ growth and advancement rhythm depends on the distance between the scar’s ends. This distance might also be conditioned by fascial pretension states, and the elastic energy, stored

secondary to the high speed and high amplitude of the injury mechanism, in pre-stressed fascial tissues. Ultimately, fibrotic scar tissue appears also to be of considerable significance for muscle re-innervation. This is because muscle injuries damage the intramuscular nerve branches at the site of the injury and, subsequently, an interposed scar that is too dense or voluminous may limit the penetration of axon sprouts through a scar to form new neuromuscular junctions that optimize motor re-innervation.

In essence, from a functional point of view, it is necessary to review the relevance not only of the structural changes happening during muscle healing, but also of the mechanical environment and viscoelastic properties of the scar and surrounding myofascial tissue during the repair process as well as during the follow-up after the return to physical activity. The following sections describe the three phases of pathobiology (Baoge et al. 2012, Järvinen et al. 2000, Järvinen et al. 2005, Järvinen et al. 2007, Opar et al. 2012, Järvinen et al. 2013), as well as the therapeutic approach proposed by the authors that includes a scar modeling technique to control the mechanical properties of myofascial tissue during the repair and remodeling phases.

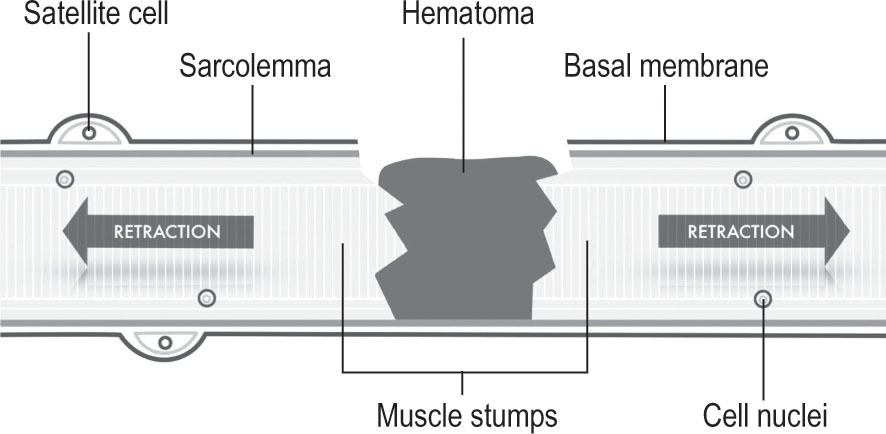

Destruction and inflammation phase (

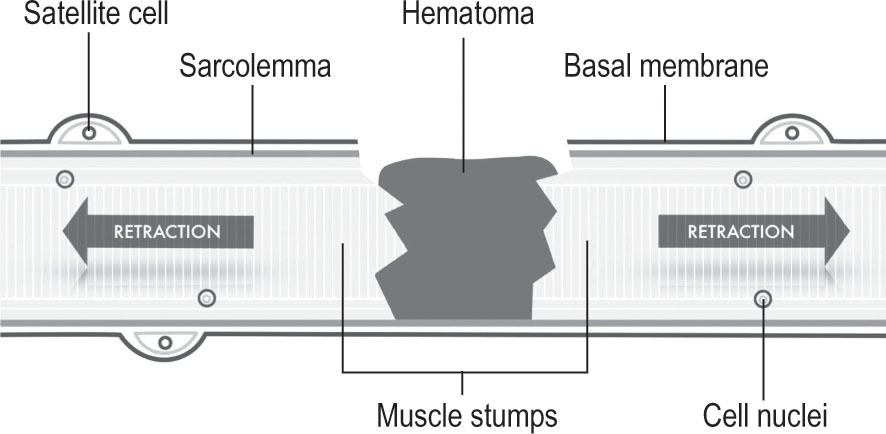

Fig. 19.1

)

Muscle healing after injury: inflammation phase

Following acute tissue injury, the destruction phase is characterized by the rupture and consecutive retraction of the myofibers as well as by the appearance of a hematoma in the gap between the ruptured muscle stumps. The damaged fibers, in turn, tend to necrotize at their ends, approximately between one and two millimeters inwardly towards the intact basal membrane. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory cell reaction, consisting on infiltrating blood derived from inflammatory cells (that eventually are transformed into macrophages), invades the injury site, setting up activities to reinstate tissue homeostasis. By phagocytosis, macrophages remove the necrotic myofibers and regulate the release of growth factors and cytokines. The biochemical signaling, together with growth factors contained by extracellular matrix, can trigger muscle regeneration and, at the same time, can activate myofibroblastic differentiation of fibroblasts and increase skeletal muscle fibrosis through the differentiation of myogenic cells into fibrotic cells in injured skeletal muscle (Li et al. 2004, Cencetti et al. 2010). In other words, these growth factors are not only strong myogenic activators but are also potential activators of connective tissue and myofibroblasts. After 24 hours, the satellite cells, a set of undifferentiated reserve cells, are activated and begin to proliferate.

Figure 19.1

Destruction and inflammation phase. It implies the rupture and consecutive retraction of the myofibers as well as the formation of a hematoma in the gap between the ruptured muscle stumps.

Manual approach in inflammation phase

Release of the elastic energy stored

Considering that the susceptibility for sustaining a muscle strain injury is greatest in high-force eccentric contractions from a lengthened position, an inadequate viscoelastic behavior of the myofascial tissue, that is essential to dissipate and absorb the kinetic energy in lengthening required during eccentric terminal movements, is usually related to

a higher risk of muscle strain injury (Schmitt et al. 2012). Thus, it is crucial to release the elastic energy stored in the mechanical environment of the injury and adjacent areas after the muscle strain injury. It should be taken into account that if perimysium are separated in the injured area, the retractile response produced is approximately 35% of the real length between the junctions and uninjured normal joint (Järvinen et al. 2007). The increased local pretension should be released to reduce the retraction of the myofibers as well as the gap between the stumps. At this early stage, being still in the initial acute phase (first 24–72 hours), the manual approach consists of manually freeing the intermuscular septa and the injury’s surrounding restrictions. The wound itself should not be directly treated (

Fig. 19.2

). This is intended to intentionally modify the transmission of joint-to-joint axial tension through the lateral unpacking of the fascial system in those areas where septa and intermuscular interfaces are present. This could considerably hold back the retractile diversionary action produced by the loss of continuity of the damaged myofascial tissue.

The fibrotic phase depends on factors such as the type, severity, location and functional implication of the damaged myofascia as well as the appropriate inflammatory response and treatment protocol. To avoid the excessive and non-functional accumulation of collagen in the mid-term it would be essential to carefully drain the hematoma in order to subsequently minimize the size of the connective tissue scar. To this end, it is important to open interfascial spaces, not only from a mechanical point of view, as mentioned above, but also with the purpose of draining the hematoma. To achieve this, it is recommended that the intermuscular septa between muscles should be treated. It is interesting to note that hematomas that move towards the surface, or the subdermal area associated with a visible ecchymosis in the skin, are a symptom of a good outcome. The appearance of big hematomas, in the mechanical environment of the injury, on an intramuscular level, exerts distractive forces that limit the wound’s stumps approach. Thus, when the drainage is inadequate, the natural response of the fibroblast would consist of encapsulation of the hematoma. Some weeks later, this evolves into a fibrous scar tissue with mechanical properties that are very different from the myofibrous tissue it replaces, hindering, in the mid-term, potential muscle regeneration (Silder et al. 2008).

RICE protocol

RICE (

R

est,

I

ce,

C

ompression and

E

levation) is generally used in this first phase. During the acute phase, this traditional protocol may be enhanced with the approach cited above and with the possible use of specific and intelligent manual treatment to modify the mechanical environment. Additionally, compression is recommended, not only to improve the hematoma drainage after manual treatment of intermuscular septa, but also to reduce the gap between the ruptured muscle stumps and ease the muscle repair (

Fig. 19.4

).

Figure 19.2

Direct technique of fascial therapy on the intermuscular septa.

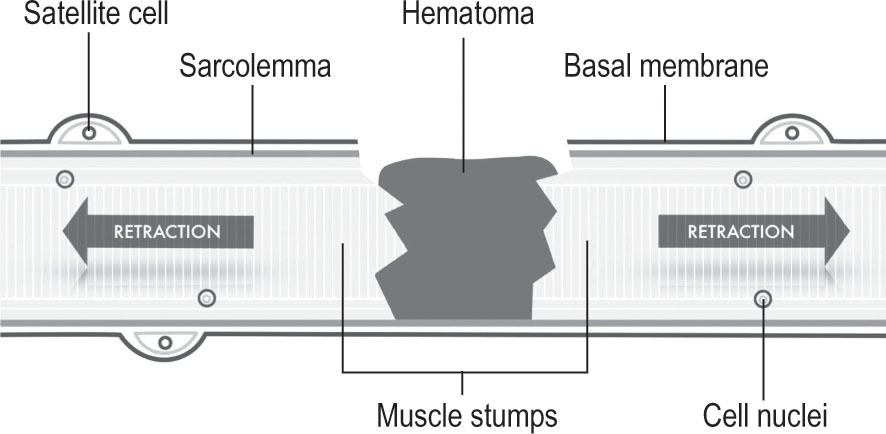

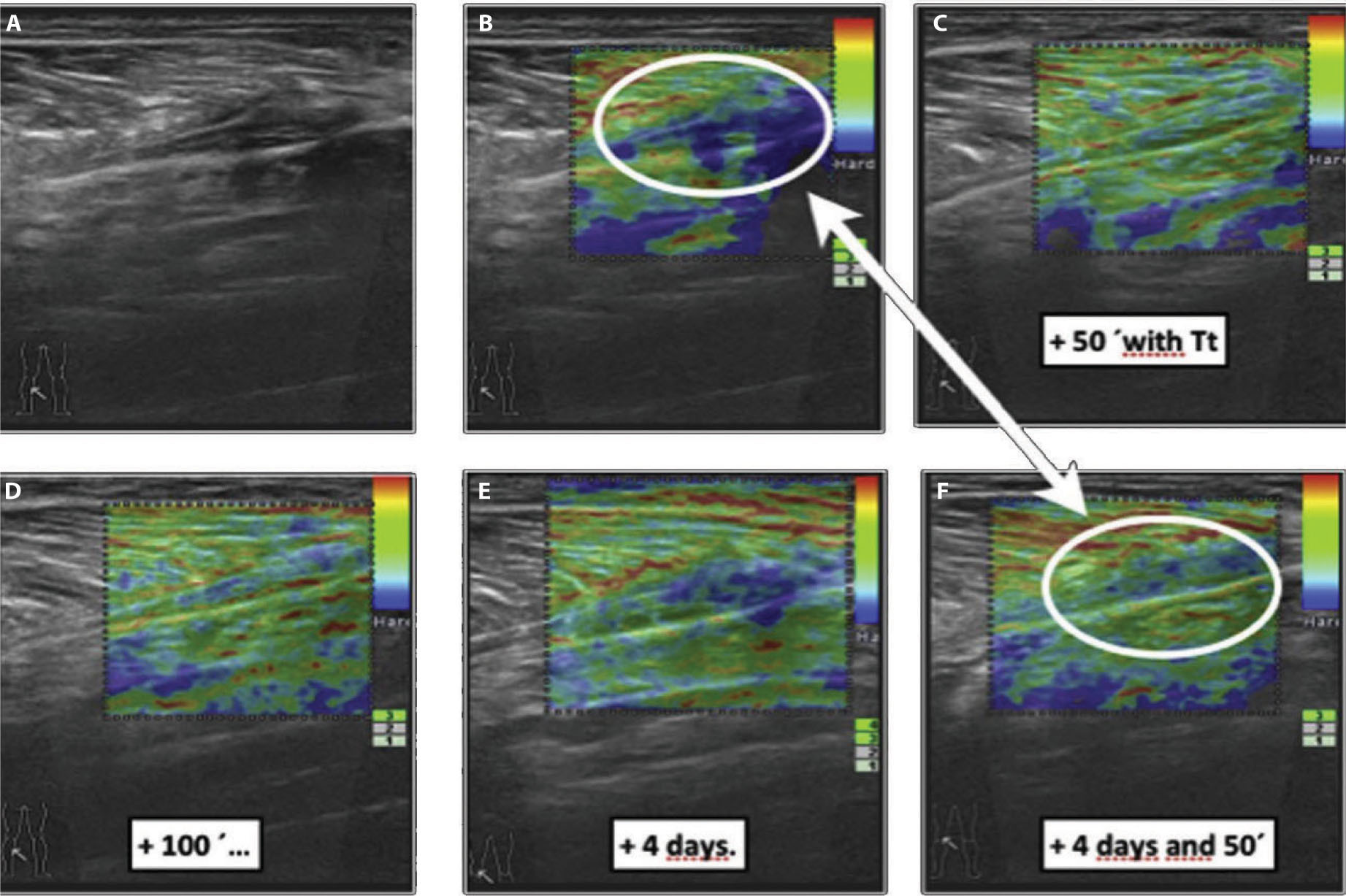

Figure 19.3

Echographic B mode and its respective sonoelastography. Images of a muscle injury (rupture of the fibro-adipose septa near the myotendinous junction of the medial gastrocnemius) over a 3-day evolution. The red color section refers to the drainage of the hematoma towards the surface. This is only noticeable in the sonoelastography image. In a clinical setting, this image is a good outcome marker.

Regeneration and fibrosis phase

Muscle healing in regeneration phase

After the acute phase, the repair and remodeling phase begins. It consists of two simultaneous processes related to the regeneration of the myofibers and reorganization of scar tissue. Initially, fibroblasts begin to fill the gap formed between the two ends of the injured muscle thanks to the production of proteoglycans and collagen type III which is placed in a primary matrix comprising blood derived fibrin and fibronectin cross-links. It is worth remembering that satellite cells were activated 24 hours after the rupture that took place in the endomysium’s basal membrane, caused by the muscular fiber damage.

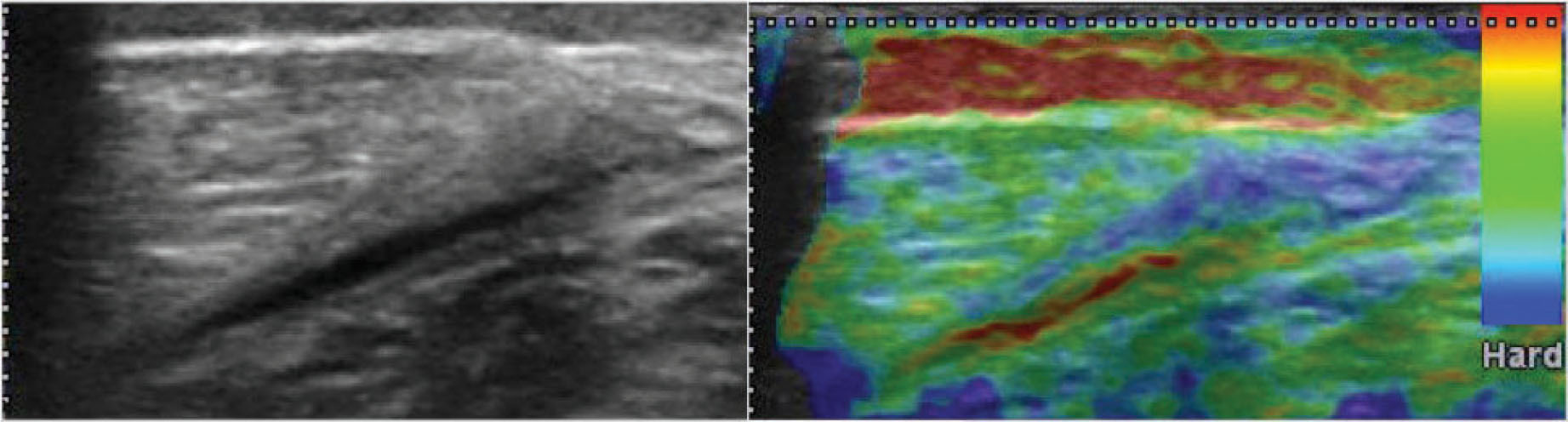

These satellite cells then separate into myoblasts that are later joined to create multinucleate myotubes. These myotubes use the former basal membrane, which is already injured, for scaffolding and anchorage, with the purpose of advancing progressively. Myotubes eventually acquire their mature state as muscular fibers. This way, each end of the fiber attempts to reach the other side of the wound. It is worth enhancing the final conic aspect, like a tunneling machine, that new muscular fibers will acquire. The whole process is coordinated, not only through release of growth factors that activate satellite cells, but also through muscle cell–extracellular matrix interactions dependent on the mechanical properties of myofascial tissue (Järvinen et al. 2007, Opar et al. 2012, Järvinen et al. 2013). As noted above, tissue stiffness and myofibroblast contractile forces partly control the TGF-β1 activation that leads to the formation of fibrotic scar tissue (Hinz 2009). In other words, the rapid appearance of a dense and stiff scar, and the excess of fibroblast activity, might decisively tip the supportive and competitive muscular regeneration process towards an excess of proliferation of connective tissue scar. From a mechanical point of view, a critical situation arises since scar tissue is stiffer than the contractile tissue that it replaces and can alter the mechanical environment of muscle fibers (

Fig. 19.5

).

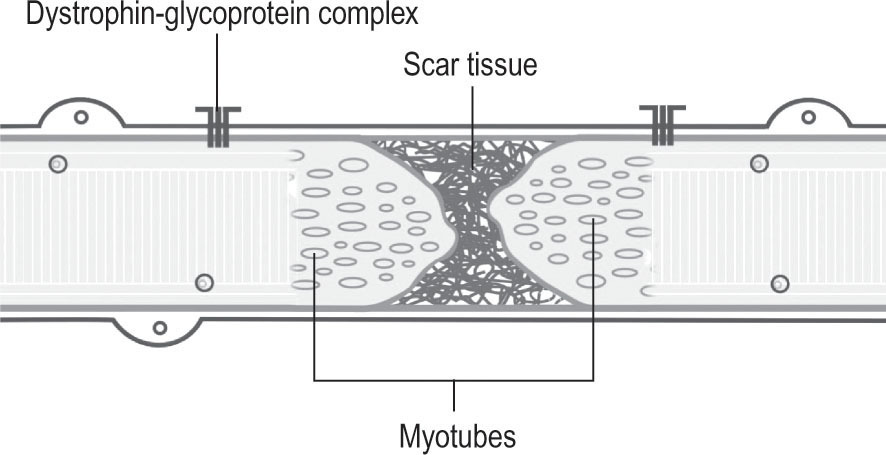

Muscle healing in fibrotic phase

The regeneration phase happens at the same time as the fibrosis and remodeling phase. This last phase is related to the formation and mainly to the maturing of a connective tissue scar. Due to this, matrices will increase their tension and stiffness in kilopascal (kPa) and the scar will become more resistant to tension; it is considered that, in a period of ten days, the scar should demonstrate sufficient tension to resist moderated traction stimulus. Likewise, the presence of specific profibrotic growth factors increases in order to ease the transformation and proliferation from fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. These have an important function because, thanks to the contractile ability of their cytoskeleton, they are able to approximate and join, as far as possible, the edges of the wound. Nevertheless, redundant activity of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts may cause an excessive proliferation of collagen; in other words, a dense and stiff scar tissue that is formed within the injured muscle. Thus, the newly formed myofibers mature, although the connective tissue scar interrupts the muscle’s regenerative process, by creating a physical barrier that determines the way the new myotubes penetrate the scar so as to reconnect themselves and complete each fiber’s regeneration (Opar et al. 2012, Järvinen et al. 2013, Lieber et al. 2013). Similarly, the volume of the interposed scar might limit the penetration of intramuscular nerves, as well as of new blood vessels. The abjunctional stumps may remain denervated when the sprouts are unable to pass through it (Järvinen et al. 2013) (

Fig. 19.6

). Following the ‘elastographic evolution control’ (an application developed by the authors of this chapter), we can have access to concise information about the maturing state of the scar and of the surrounding tissue to contribute to, or restrain, the biosynthetic activity of the fibroblast.

Figure 19.4

Ultrasound and sonoelastographic control images of a muscle injury (rupture of the fibro-adipose septa near the myotendinous junction of the medial gastrocnemius) over a 3-day evolution. The difference between the hematoma’s size and the existent space at the fascial level, with or without a local compression component, is noticeable.

Figure 19.5

Regeneration phase. At this point, fibroblasts begin to fill the gap formed between the two ends of the injured muscle. Fibrotic scar tissue formation is partly controlled by tissue stiffness. Macrophages simultaneously play an important role because they clean up necrotized remains leaving the basal membrane unharmed so that it can work as scaffolding in the future

Figure 19.6

Fibrosis phase. This is the characteristic appearance of musculotendinous small unions in repairing processes. Fibers are linked through scarring tissue, whose mechanical properties differ from those of the muscular fiber.

Manual matrix remodeling in regeneration and fibrotic phases

As mentioned above, a pure competition between fibroblasts and satellite cells begins during this phase. The prosperity in the meeting of myotubes determines the success of the repair process. Thus, in a clinical setting, we often see that the excessive stimulation of fibroblasts through intense programs based on too eager and intensive application of mechanical loads will modify this balance towards scars, where the presence of fibrosis mechanically restrains the meeting of the newly created myotubes, so limiting regeneration. At this stage, manual treatment should aim to prevent excessive maturing of the scar’s neocollagen, in order to allow the advancement of myotubes and new nerve fibers that should reinnervate the new tissue.

This is the moment when the scar modeling technique is applied (approximately from the 10th day) to modify the mechanical properties of the scar and the adjacent areas. The authors of this chapter have developed a technique that attempts to reverse the matrix state from high to low tension, with controlled mechanical stimuli through the combined use of torsion, shear, traction, axial and compressive vectors on scar tissue. All this is done in order to produce a continuing tension against a barrier until a release of tension is perceived (Pilat 2003). We suggest that the pursuit of tensional homeostasis by the therapist’s manual treatments, guided by the liberation of ‘jumps’ of accumulated elastic energy in the interfaces, could cause the 3D reorganization of fascial interfaces on a macroscopic level, resulting in tensional normalization on the microscopic level (tensional re-harmonization between the cytoskeleton and extracellular membrane through receptor integrins). This re-harmonization acts to normalize cell function and provide medium-term remodeling of the extracellular matrix (Martínez Rodríguez & Galán del Rio 2013).

The different stages of scar modeling technique (

Fig. 19.7

) are described in detail:

1.

Contact phase. This involves an initial vector compression, delivered by the second, third and fourth fingers of one hand. The applied pressure should be enough to reach the level of the scar, where the first resistance is met.

2.

Stimulation phase. From this point, an axial and/or spiral/circular component is added to the initial vector compression until a further resistance barrier is reached. This way, a combination of elastic barriers will have been engaged by the fingers of the therapist. This combined compression and torsion is maintained for some time (30–90 seconds).

3.

Release phase. At this point, depending on the tissue response to the initial stimulus, it is usual to perceive a release of stored elastic energy in the form of ‘local unwinding’. This is followed by a progressive decrease of the initial tension as contact is maintained and as reorganization of tissues in the scar area occurs, leading to a spontaneous repositioning of the fingers as the barrier modifies.

4.

This process should be repeated as many times as needed (usually three to five) in order to finally notice a normalization of the initial feeling of tension.

Summary of proposed mechanisms

Inflammation phase: manual matrix remodeling

•

Release the elastic energy stored to reduce the retraction of the myofibers as well as the gap between the stumps via manual treatment over intermuscular septa.

•

Hematoma drainage to reduce the size of the connective tissue scar via manual treatment over intermuscular septa (neurovascular tracts in which the blood vessels, lymphatic and nerves are embedded).

•

Compression to diminish the gap between the ends of the fiber and to complement hematoma drainage.

Repair phase: manual matrix remodeling (scar modeling technique)

•

Manually lead the collagen denaturalization in the area through controlled thixotropic reaction.

•

Coordinate the reorientation of the new collagen fibers and modulate the excessive proliferation of intermuscular connective tissue.

Figure 19.7

Scar modeling technique. Contact phase, stimulation phase and release phase as described above.

An illustrative case history (

Fig. 19.8

)

We propose the use of real-time sonoelastography (RTSE) as an imaging test to evaluate the mechanical properties of myofascial tissue. These images depict a traditional example of a color-coded display of an elastogram at the distal myotendinous junction of the medial gastrocnemius and soleus, which is superimposed on the B-mode ultrasound image. The break of the fibro-adipose septa near the myotendinous junction of the medial gastrocnemius and soleus muscle matches the elasticity curve that can be seen. This image, representing a strain, is very useful when comparing the level of stiffness through colors from red (soft, i.e. fluid collection) to blue (hard, i.e. fibrotic scar tissue) with green indicating an intermediate level of stiffness. The circular regions of interest (ROIs) were placed upon the hardest reference of the color-coded image (visualized in the elastogram) and near the center of the wounded area (visualized in the B-mode sonogram) associated with the reparative process between medial head gastrocnemius and soleus.

At first, this patient’s clinical diagnosis was based on the display of sudden pain, related to a snapping sensation and weakness on the lower extremity, in the posterior mid-calf. Six weeks later, the patient referred to stiffness and a decrease in functional capacity, including fear of being re-injured due to an increased eccentric loading at longer muscle lengths. In

Figure 19.8B

, the contrast of the elastic properties between fibrotic scar (blue color) and normal tissue can be seen. After just 50 minutes of manual treatment (including the scar modeling technique), differences can be appreciated from the pre-treatment state, and immediate effects of elasticity changes (thixotropic reaction). Interestingly, changes are observed in mechanical properties after 4 days, especially after the patient has gone through a second treatment with scar modeling technique - as shown in

Figure 19.8F

. Consistently throughout our clinical experience, we have observed that once the relative elasticity (heterogeneous image with stiffer areas) evolves to a more organized and homogenous color-coded image, the patient usually experiences a decreasing sensation of stiffness and fear of re-injury. Given that connective tissue fibroblasts appear to be highly mechanosensitive, it is necessary to inhibit the biosynthetic activity reducing the fascial pretension and extracellular matrix mechanical stress. In order to achieve this, we use the scar modeling technique, both in the scar and in the surrounding areas, as well as manually treating the intermuscular septa related to the muscle strain injury.

•

Maintain a ‘low tension state’ in the scarring area in order to extend the regenerative phase and allow the advance of the myotubes until they meet the progress of the new vessels and the re-innervation of new fibers.

•

Postpone the strengthening of integrin–dystrophin complexes on myofascial connections between sarcoma and basal membrane in order to promote the advancement of myotubes.

•

Control the excessive proliferation of myofibroblasts amid the regenerative phase.

•

Contribute to the ‘thixotropic agility’ of the scar tissue by supplying it with mechanical properties that promote the behavior of the surrounding myofascial tissues.

Figure 19.8

Elasticity curve of a scar in the distal myotendinous junction of the medial head gastrocnemius and soleus. It is possible to see differences between pre-treatment and immediate effects in elasticity changes (thixotropic reaction) after 50 and 100 min of scar modeling technique. Interestingly, changes in mechanical performance/behavior can be seen after 4 days and a second treatment with scar modeling technique.

References

Baoge L, Van Den Steen E, Rimbaut S et al 2012 Treatment of skeletal muscle injury. ISRN Orthopedics 2012:689012

Cencetti F, Bernacchioni C, Nincheri P et al 2010 Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces transdifferentiation of myoblasts into myofibroblasts via up-regulation of sphingosine kinase-1/S1P3 axis. Mol Biol Cell 15:1111–1124

Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Waldén M 2011 Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am J Sports Med 39: 1226–1232

Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE 2006 Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126:677–689

Freckleton G, Pizzari T 2013 Risk factors for hamstring muscle strain injury in sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 47:351–358

Hinz B 2007 Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Invest Dermatol 127:526–537

Hinz B 2009 Tissue stiffness, latent TGF-beta1 activation, and mechanical signal transduction: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of fibrosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 11:120–126

Järvinen TA, Kääriäinen M, Järvinen M, Kalimo H 2000 Muscle strain injuries. Curr Opin Rheumatol 12:155–161

Järvinen TA, Järvinen TL, Kääriäinen M et al 2005 Muscle injuries: biology and treatment. Am J Sports Med 33:745–764.

Järvinen TA, Järvinen TL, Kääriäinen M et al 2007 Muscle injuries: optimising recovery. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 21:317–331

Järvinen TA, Järvinen TL, Kalimo H 2013 Regeneration of injured skeletal muscle after the injury. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J 24: 337–345

Kääriäinen M, Järvinen TA, Järvinen M et al 2000a Relation between myofibers and connective tissue during muscle injury repair. Scand J Med Sci Sports 10:332–337

Kääriäinen M, Kääriäinen M, Järvinen TA et al 2000b Integrin and dystrophin associated adhesion protein complexes during regeneration of shearing type muscle injury. Neuromuscul Disord 10:121–132

Katsumi A, Naoe T, Matsushita T et al 2005 Integrin activation and matrix binding mediate cellular responses to mechanical stretch. J Biol Chem 280:16546–16549

Khan KM, Scott A 2009 Mechanotherapy: how physical therapists′prescription of exercise promotes tissue repair. Br J Sports Med 43:247–252

Kjaer M 2004 Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiol Rev 84:649–698

Martínez-Rodríguez R, Galán del Río F 2013 Mechanistic basis of manual therapy in myofascial injuries. Sonoelastographic evolution control. J Bodyw Mov Ther 17:221–234

McCall A, Carling C, Davidson M et al 2015 Injury risk factors, screening tests and preventative strategies: a systematic review of the evidence that underpins the perceptions and practices of 44 football (soccer) teams from various premier leagues. Br J Sports Med 49:583–589

Mueller-Wohlfahrt HW, Haensel L, Mithoefer K et al 2013 Terminology and classification of muscle injuries in sport: the Munich consensus statement. Br J Sports Med 47:342–350

Li Y, Foster W, Deasy BM et al 2004 Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces the differentiation of myogenic cells into fibrotic cells in injured skeletal muscle: a key event in muscle fibrogenesis. Am J Pathol 164:1007–1019

Lieber RL, Ward SR 2013 Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. Structural and functional consequences of skeletal muscle fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305:241–252

Opar DA, Williams MD, Shield AJ 2012 Hamstring strain injuries: factors that lead to injury and re-injury. Sports Med 42:209–226

Passerieux E, Rossignol R, Chopard A, et al 2006 Structural organization of the perimysium in bovine skeletal muscle: Junctional plates and associated intracellular subdomains. J Structural Biology 154:206–216

Passerieux E, Rossignol R, Letellier T, Delage JP 2007 Physical continuity of the perimysium from myofibers to tendons: Involvement in lateral force transmission in skeletal muscle. J Structural Biology 159:19–28

Pilat A 2003 Inducción miofascial. McGraw Hill Interamericana, Madrid

Schmitt B, Tim T, McHugh M 2012 Hamstring injury rehabilitation and prevention of reinjury using lengthened state eccentric training: a new concept. Int J Sports Phys Ther 7:333–341

Silder A, Heiderscheit B, Thelen DG et al 2008 MR observations of long-term musculotendon remodeling following a hamstring strain injury. Skeletal Radiol 37:1101–1109