KAREN SMITH ROTABI AND CARMEN MÓNICO

KAREN SMITH ROTABI AND CARMEN MÓNICOTHE END OF WORLD WAR II in the late forties marked the beginning of the practice of formally adopting children internationally on a large scale. The practice is called intercountry adoption (ICA) and at least one million children have been adopted internationally since the early days, as the practice truly took off in South Korea in the mid-fifties. Half of all international adoptees have joined U.S. families (Selman, 2012). For children, the impact of ICA has been profound; the research on improvements in child development and health alone, make a strong case for the practice of ICA (Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2012; Miller, 2012). For individuals and couples who build their families through ICA, the opportunity to be matched with a child from another country is frequently a deeply satisfying experience in which their family life goal is realized. However, there have been problems in the actual ICA adoption process, including serious persistent problems in illicit adoptions (Ballard, Goodono, Cochran, & Milbrandt, in press; Gibbons & Rotabi, 2012). When this is the case, birth families are exploited; their circumstances of poverty typically leave them vulnerable and the emotional aftermath of an illicit adoption is profound.

PROTECTING VULNERABLE PEOPLE: INTERNATIONAL PRIVATE LAW AND A CHILD RIGHTS APPROACH

Attempts at reform are under way globally to regulate the market forces in ICA (Ballard et al., in press; Rotabi & Gibbons, 2012). Most notably, the Hague Convention of May 29, 1993, on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption (hereafter referred to as the Hague Convention or simply the HCIA), as of June 1, 2014, had ninety-three contracting states, including the United States. As international private law, the Hague Convention was developed to prevent the sales and abduction of children under the guise of ICA (Hague Conference on International Private Law [HCCH], 1993). The “best interests of the child” is the central value (McKinney, 2007). Recognized by adoption experts to be an important step forward (Gibbons & Rotabi, 2012; Roby & Maskew, 2012; Rotabi & Gibbons, 2012), the HCIA has been critical in reform efforts because of an unfortunate pattern of force, fraud, and coercion (Ballard et al., in press; Freundlich, 2000; Gibbons & Rotabi, 2012; Hollingsworth, 2003; Rotabi, 2012c; Rotabi & Gibbons, 2012).

Fundamentally, the primary purpose of the Convention is the protection of the child within his or her biological family and community. Consistent with the HCIA is a continuum of care—called the subsidiarity principle—oriented to preserving biological and kinship family life with child rights–best interests focus. Roby (2007) presents a child rights approach to ICA that is consistent with principles of the HCIA. Before adoption, children’s rights include (1) the right to life, maternal, prenatal care, and health care; (2) the right to grow up in a family; and (3) the right to grow up in his or her own culture. During adoption, children’s rights include (1) the right to a determination of adoptability, (2) the right to be placed with a properly prepared adoptive family, (3) the right to be matched with families who can and will provide for special needs, (4) the right of protection from becoming a commodity, (5) the right to competent and ethical professional care, and (6) the right to give consent or express own opinion. After adoption, children’s rights include (1) the right to full family membership, (2) the right to social acceptance, and (3) the right to have access to birth and identity records.

Importantly, children’s right to adoption by extended family, kinship, or other nationals is fundamental. Then, the possibility of ICA may be determined to be appropriate after these in-country options have been explored by professional social workers. Roby (2007) further identifies that countries should provide family support services and also adopt regulations aimed at eliminating unethical practices on the part of public servants, as well as private adoption agencies, and others involved in the ICA chain. The elements in Roby’s framework are useful when considering the practical implementation of the HCIA. Presented next are examples of adoption fraud that illustrate both the need for regulation as well as the points of fraud that must be addressed by the HCIA, and related laws. These cases serve as a backdrop—answering the obvious question of how illicit adoptions are carried out and thereby pointing to the directions of reform and greater accountability of ICA practices.

CASE EXAMPLES OF ADOPTION FRAUD

Child sales and abduction have been orchestrated in a variety of ways in numerous countries around the world. Contextual factors shape how illicit adoptions are orchestrated. Cambodia, Guatemala, Haiti, and Chad are presented as illustrative examples.

Cambodia

In Cambodia an adoption facilitator, employed by Seattle Adoptions International, orchestrated child sales into an adoption scheme in a systematic manner from 1997 to 2001 with an estimated $8 million in profit (Maskew, 2004; Roby & Maskew, 2012; Smolin, 2004, 2006). The investigating U.S. Federal Marshall reported the illegal activities to be consistent with organized crime, including such dynamics as money laundering (Cross, 2005). Law enforcement investigation as well as legal proceedings in the United States uncovered a chain of events related to child sales; impoverished families were approached in villages with bags of rice and relatively small sums of money given upon signature of child relinquishment documents. Once secured, the child then entered into a chain of falsehoods required to establish that the child was an “orphan.” Upon investigation, it was found that not only were the vast majority of the children not orphans, but many Cambodian families expected to stay in touch with their child. Some families reported that they thought their child was going to boarding school, whereas others understood that their child was going to a family in another country. They, however, expected visits with their child and that the child would return to Cambodia once he or she was a young adult. When it was understood the child would be living with another family, the concept of a legal severance of parental rights was most often not understood by Cambodian families (Cross, 2005).

In this particular case of Cambodia, the adoption facilitator served a relatively short jail sentence related to tax evasion because the laws were not sufficient, at that time, to prosecute on the grounds of child trafficking. After conducting an extensive analysis of the adoption fraud in Cambodia, Smolin (2006) concluded that this chain of illicit activities was orchestrated as “child laundering,” a practice similar to money laundering, whereby the money’s origin and the resulting illicit gain cannot be identified easily. Child laundering involves a chain of organized crime to change a child’s identity by issuing or altering a child’s birth certificate and deceitfully representing the child’s social history, as well as other falsehoods to obtain the child’s adoptability determination—that is the determination that the child is free and clear to be adopted internationally. As in money laundering, illegal transfers of money for child buying occurred; off-shore bank accounts were established and tax evasion transpired along with graft and corruption on the ground in Cambodia (Cross 2005; Maskew 2004; Smolin 2006).

Smolin (2006) asserts that fraudulent practices are orchestrated as part of a system that legitimizes and incentivizes practices of buying—trafficking—children under the guise of appropriate and ethical practices of adoption agencies. Smolin and others have scrutinized different illicit and unethical adoption practices used in other countries (Ballard et al., in press). Next, we look at so-called child rescue during the disaster in Haiti and Chad, and then we turn to Guatemala.

Haiti and Chad

An important case that further illustrates force, fraud, and coercion occurred in mid-January 2010 during the postearthquake period in Haiti, when a U.S.-based Christian group attempted to transport thirty-three Haitian children to the Dominican Republic for placement in a home, while they waited to be adopted (The Economist, 2010; New Life Children’s Refuge, n.d.). Once it became clear that the group was engaged in illegal removal of children from their families and community, members of the Idaho-based New Life Children’s Refuge were detained in Haiti for child trafficking; the missionaries were charged with child abduction and held in prison for several months (Rotabi & Bergquist, 2010). Members of the group eventually were released from prison, and this event reminded many adoption practitioners and scholars of similar attempts to “rescue” children during emergencies (Bergquist, 2012; Rotabi, Armistead, & Mónico, in press).

For example, in 2007, staff members of the French charity, Zoé’s Ark, were detained trying to airlift 103 children from Chad; they were charged with child kidnapping and six of them were jailed (Bergquist, 2012; The Economist, 2010; Rotabi & Bergquist, 2010). This particular case, like the Haitian case, received considerable media attention when the fraudulent chain was discovered. The child evacuation plan was disguised as an attempt to rescue children from the war in neighboring Sudan. Although the individuals involved in this “rescue” attempt were incarcerated in Chad, they eventually were pardoned after diplomatic intervention from France (Bergquist, 2012).

Guatemala

In recent history, Guatemala has the most notorious record of pervasive force, fraud, and coercion as related to ICA on a large scale. In this particular country, the complexity of fraud was rooted in a weak state as a result of a 36-year civil war (1960–1996). Also, Guatemala is one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere where human trafficking, in general, is recognized to be common in the twenty-first century (Estrada Zepeda, 2009). Furthermore, violence against women is so extreme at a societal and familial level that it is considered to be an endemic social problem (Estrada Zepeda, 2009).

These facts coincided with the country’s child adoption laws and other social protection regulations that were inadequate during the adoption boom years. An unknown, but significant, number of approximately 30,000 adoptions that took place between 2000 and 2009, were unethical at best and illicit at worst. The problems were such that the United Nations intervened with an investigation that resulted in an explosive report in the year 2000, when attempts were first made to regulate the system (United Nations, 2000).

Regardless of human rights reports and criticism, the ICA system persisted and by 2010 an extensive investigation by the Comision Internacional contra la Impunidad (International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala [CICIG], 2010) found evidence of the participation of members of state institutions in irregular adoptions, including “child laundering” activities by the Court for Children and Adolescents, which declared stolen and purchased children as “abandoned” to begin the adoption process. According to the CICIG report, the U.S. Embassy in 2005 conducted a study of prospective adoptive parents and found that they were paying exorbitant amounts for the adoptions (i.e., US$17,300 to $45,000 in adoption fees). The CICIG (2010) also found that the Office of the Attorney General authorities recognized that some of the birth mothers were being paid to relinquish their children. Family Court judges denied direct responsibility for making final decisions about the adoptions, and social workers handling those cases were not conducting home visits or field investigations to verify cases. They relied only on information provided by the lawyers processing the adoption. With Guatemalan lawyers in the main position of power, the adoption of children became a distorted process in which a small group of corrupt lawyers profited from illicit adoptions.

GUATEMALAN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS STEP IN TO PROTECT WOMEN AND CHILDREN

Under these conditions the human rights abuses were profound—a failure of the state to protect its children and families. In time, human rights defenders in Guatemala took up the cause to demand change, including filing critical legal cases. For example, Fundación Sobrevivientes or Survivors Foundation (Estrada Zepeda, 2009), provided legal assistance to a group of mothers experiencing child abduction in Guatemala (Mónico, 2013). One of the women is Ana Escobar.

Escobar’s case became known when the Associated Press reported about her child’s abduction (Associated Press, 2008a, 2008b). Escobar’s terrifying story of a child kidnapping unfolded in her workplace, a shoe store in Guatemala City. After her assault, Escobar sought help from the police only to be chastised by the officials as being a birth mother who had changed her mind—accused of already having profited from child sales. She searched and searched for her daughter. Then, upon a chance sighting of the young child when passing an official’s office where she was lodging a complaint, Escobar was finally able to plead with officials to DNA test the child that she claimed to be her daughter (Personal communication, A. Escobar, August 9, 2009). That test was positive and the ICA process was suspended for this particular child. It was, at this point in Guatemalan adoption history, the clearest single proven case of child abduction into adoption through organized criminal networks to carry out ICA fraud, which included judges, lawyers, care providers, and adoption agencies. This is evidenced, in part, by the fact that a previous DNA test linked Ana’s daughter to the woman who falsely claimed to be the child’s birth mother. Furthermore, during the required interview by the U.S. Embassy, this woman falsely claimed to be the birth mother as she verified her consent to the adoption. With such a backdrop of evidence, the world learned that DNA tests were false in Escobar’s case. Other cases of DNA fraud also have been documented as the media reported on the failings of Guatemala’s ICA system. For example, in another high-profile case, Guatemalan courts found a child to be abducted into adoption. A standing court order for the child’s return continues to be ignored by the U.S. family, with no resolution of the case (Rotabi, 2012a).

Legal claims have been observed in other countries to include Vietnam, India, the Marshall Islands, Samoa Islands, El Salvador, and elsewhere (Ballard et al., in press; Bergquist, 2012; Gibbons & Rotabi, 2012). The problem has been so pervasive that long-term attempts to truly regulate illicit adoption practices have been under way in earnest for well over a decade in the United States. Guatemala, too, has undertaken reform. Both countries are presented as case examples of HCIA implementation.

PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATION OF THE HAGUE CONVENTION: THE UNITED STATES AND GUATEMALA

To combat illicit practices—child sales and abduction—each HCIA signatory country agrees upon principles and standards, with the “best interests of the child” and the “principle of subsidiarity” being core to HCIA implementation. Each country implements the HCIA as per their context and resources; domestic adoption laws in each country are an important and integral component to effective application of the HCIA.

U.S. Implementation of the Hague Convention

In the United States, the Hague Convention entered into full force in April 2008. Part of U.S. implementation of the HCIA was the passage of the U.S. Intercountry Adoption Act of 2000 (IAA, P.L. 106–279 [2000]; Smolin, 2004, 2006). This particular law domesticates principles of the Hague Convention into U.S. legal code, and it creates regulatory mechanisms, including the possibility to effectively prosecute individuals involved in this form of child trafficking (Rotabi, 2008). Other countries that have ratified the Hague Convention and have undertaken the same process of domesticating the HCIA with congruent local legislation. This ensures that ICA laws are harmonized globally—thereby providing a uniform system and procedures that ideally enable and enhance the collaboration between interacting governments (Boéchat, 2013).

U.S. implementation of the HCIA has required substantial institutional changes, and in the twenty-first century, the new policies and procedures have affected practice considerably. Transformation of legal frameworks and policies interface with improved adoption agency systems. As such, greater professionalism within agencies and higher standards on the part of civil servants has improved the ICA system. Implications for practice, related to adoption agencies and professionals will be discussed later in the chapter, and we now turn to the implementation of the HCIA in a low-resource country with significant challenges in terms of regulatory and procedural change.

The Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption (HCIA) requires that a country develop their congruent domestic laws on adoption. For example, in the United States, the Intercountry Adoption Act was passed in 2000, and this legislation identifies the U.S. Department of State (DOS) as the central adoption authority and the DOS Office of Children’s Issues provides oversight of U.S. implementation of the HCIA. This regulatory role includes accreditation of adoption agencies as well as responding to illegal activities with powers to initiate investigations in collaboration with the Department of Justice. The Office of Children’s Issues may determine that another country is not within convention compliance and deem the country closed for child adoption by U.S. citizens.

Guatemala’s Hague Convention Implementation

Guatemala ratified the Hague Convention and a domestic law was passed by Guatemala’s Congress at the end of 2007 (Bunkers & Groza, 2012). The Guatemalan law focuses on the subsidiarity principle, which requires that a concerted effort is made to support the child’s welfare within his or her own community and country. In other words, when a child is orphaned or vulnerable, she must receive appropriate child welfare services before ICA (Rotabi & Gibbons, 2012). When that is not possible, a child can be made available by appropriate government authorities, called the Central Authority in the HCIA.

Fundamentally, this idea of subsidiarity translates into a continuum of care in which a child identified to be at risk of an out-of-home placement ideally would receive family support services to prevent her permanent removal from biological family and community life (HCCH, 2008). Biological family support is fundamental to promote the child’s care within the family system, and when that fails, alternative care in the community is the first step for social service authorities to take. This community care may include guardianship and other forms of care, and foster care is appropriate in some countries. Then, when this option is not possible and adoption is identified as a plan, domestic adoption is the priority (HCCH, 2008). Only when a domestic adoption has been ruled out, may a child be identified as appropriate for ICA as per the subsidiarity principle; institutional childcare is not a priority over ICA (HCCH, 2008).

A thorough investigation of the child’s social history is necessary when possible, and other case management strategies are required to engage the family to explore all options to preserve the family system, including kinship care. Such an approach, when done well, is time-consuming and often results in delays in child ICA placement. As a result, criticism has been lodged, and the debates about this issue are quite compelling (Bartholet & Smolin, 2012) when one considers the developmental and emotional problems experienced by a child when she must wait and languish in care in a residential institution (Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2012).

COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS OF THE HAGUE CONVENTION

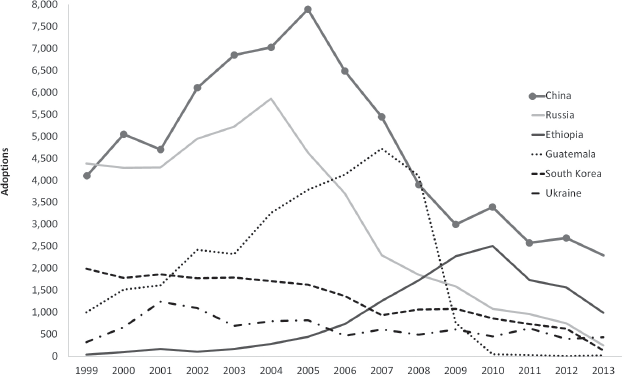

Even with many positive steps forward to ensure ethical practices, the HCIA has been criticized for a significant downturn in ICAs to the United States and elsewhere. When one examines the facts, however, the HCIA is only one part of the radical decline in the practice. Figure 2.1a depicts the downturn of ICAs to the United States in recent history.

FIGURE 2.1A Transnational Adoptions to the United States, 1999–2013

Source: U.S. Department of State, 2014.

FIGURE 2.1B U.S. Visas Issued to Orphans, 1990–2013

Source: U.S. Department of State, 2014.

One fact is indisputable, ICA to the United States was at an all-time high in 2004 with 22,884 adoptions, and then a free fall in ICA began, with a more than 60 percent decrease overall by 2013. This fact alone underscores that the Hague Convention is not the sole factor in the decrease because the related regulations did not enter into full force in the United States until 2008—some 4 years after the major decrease began (Rotabi, 2008). When looking at the top-three countries of origin in recent times, unique dynamics in Russia, China, and Guatemala help explain the story of the decrease.

The Russian ICA moratorium with the United States is the result of multiple international incidents that enraged both the general public in Russia as well as the political sector (Rotabi & Heine, 2010). Multiple political forces were at play in terms of U.S.–Russia foreign relations, including a completely unrelated human rights abuse incident in Russia that resulted in the death of a relatively prominent individual in a Russian prison. When the United States publicly condemned Russia for its treatment of this particular prisoner, Russian Parliament swiftly instituted an adoption moratorium, and this particular bitter moment between the two governments most certainly contributed to the final moratorium. A moratorium, however, had been debated for several years in Russian Parliament, and it is fair to say that multiple factors contributed to the cessation of ICAs to the United States. Russian Parliament voted to end ICAs to the United States in late 2012 as a result of child abuse and neglect at the hands of U.S. adoptive parents. By mid-2012, Russia counted nineteen deaths of Russian adoptees in the United States, and there were other instances of child maltreatment, including a high-profile child sexual abuse and pornography case (Rotabi, 2012b). Notably, Russia has not signed the Hague Convention, and thus this international private law has had little impact on Russian adoptions. These problems, however, most certainly have been associated with the decline in practice.

In the case of China, a Hague Convention country, the slowdown is related to a number of factors, including a shift to children who are called “special needs” because of medical and emotional challenges (Dowling & Brown, 2009). This is a change from the previous China programming that was consider highly efficient—translating into relatively expedient adoptions of largely healthy and relatively young girl children who were reported to be abandoned (Johnson, 2012; Johnson, Banghan, & Liyao, 1998; Vich, 2013). That now has changed, however, as child abandonment is far less frequent and child placement wait times for China are now more than 5 years. Other factors include more domestic adoptions taking place in China and shifts in the one-child policy and greater flexibility for citizens of China in their family-building options. With an improvement of economic circumstances, some Chinese families simply decide to pay a fine for their second child rather than abandon daughters (Vich, 2013).

The case of Guatemala has been explored, but it is important to note that this small Central American nation was the only country of origin that continued to have a truly significant increase in adoption after 2004 (Selman, 2012). The slowdowns in other countries actually put increasing pressure on Guatemala as a country of origin. This pressure combined with the fact that approximately 90 percent of the children were infants or toddlers who were relatively healthy (Casa Alianza et al., 2007). Also, adoptions were processed quickly, many families experienced a year or less of wait time for child placement, which is an exceptionally short waiting period as compared with other countries (Bunkers & Groza, 2012). As a result, Guatemala was a popular country for U.S. families. The extremely positive reputation among prospective families endured even though most other countries, like Canada and the United Kingdom, entered into adoption moratoriums with Guatemala before 2004 (CICIG, 2010; Rotabi, 2012b). In time, some families who have adopted from Guatemala have come to realize that the expedient process was actually indicative of a loose process that did not safeguard the rights of the child or their families of origin. Some adoptive parents have come to wonder about the ethics of their own cases (Larsen, 2007; Seigal, 2011).

Once Guatemala finally entered into adoption moratorium, there was a shift elsewhere and most notably to Africa and specifically Ethiopia (Rotabi, 2010), an often-cited country to have a noted increase in ICAs in recent times. The number of Ethiopian children adopted by U.S. families is still relatively small in the overall picture, as indicated in figure 2.1b. Dynamics of corruption in Ethiopia have gained attention in the international press, and procedures are of concern there and in other African countries (Bunkers, Rotabi, & Mezmur, 2012; Mezmur, 2010).

Even with the obvious need for greater regulation of ICAs from Africa, many countries such as Ethiopia have not yet signed the Hague Convention. Although there have been attempts to encourage African countries to join this international private law, progress has been slow. Some countries, however, appear to be seeking technical assistance from the Hague Conference on International Law Permanent Bureau and are making steps toward contracting the HCIA. The Hague Permanent Bureau has no ability to fund reform initiatives. Humanitarian assistance organizations are poised to assist in this particular aspect of change. Technical assistance, on the other hand, is available from the Hague Permanent Bureau for suggested systems improvement to better meet the obligations of subsidiarity according to the HCIA. Countries moving in that direction are reported to be Mozambique, Rwanda, Namibia, and the Seychelles (Africa Child Policy Forum, 2012). Notably, Uganda has also shown early signs of movement toward the HCIA, and this move is welcome by those making investments in child protection in this particular country, which has seen a remarkable increase in ICA in the past few years (Personal communication, Sylvia Namubiru, August 11, 2014).

Other countries have been on a steady decline, most notably South Korea, which has sent well over 100,000 children worldwide since the mid-fifties. Changes include a vibrant twenty-first-century economy and increasingly less stigmatized circumstances for illegitimate births. Also, in parallel, domestic adoptions are now outnumbering ICAs in South Korea. As such, these social conditions, as well as other factors, like birth control and women’s rights have an accumulative effect on ICA downturns. In the case of increased domestic adoptions South Korea is a success story. The country was previously criticized for ignoring their child protection problems and simply sending their orphaned and vulnerable children elsewhere (Fronek, 2006). Systems of care, however, have been built and social services are far more responsive to the needs of children and their families. South Korean adoption declines are an example of global changes in ICA that are not related to moratorium of the practice, but rather to a decrease resulting from social change. This trend is expected to continue globally as systems of childcare are strengthened and economic conditions improve around the world.

PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE HAGUE CONVENTION AND IMPACT

In this era of reform, we now turn to the impact of the HCIA on (1) adoption agencies and professionals, (2) birth families, (3) adoptive families, and (4) child development.

Impact of the Hague Convention on Adoption Agencies and Professionals

Given the problems outlined thus far, the process and procedures for ICA have been strengthened considerably in the United States and Western Europe where most children are adopted. The most predominant changes have been at the adoption agency level. Improvements include the policies and procedures that do not allow adoption agencies to intervene before attempts to support children and families prior to adoption, as per the subsidiarity principle. Furthermore, adoption agencies and their professionals must be vigilant to prevent child sales and abduction.

Among the Hague Convention–related requirements is greater financial transparency in adoption agency transactions. In practical terms, this translates to adoption agency accountability for how money is handled—for example, salaries based on ordinary professional compensation without opportunity for bonuses or contingency fees based on the number of children placed into adoption. In the United States, a set fee schedule also must be provided for prospective families in their earliest contact with the agency (Council on Accreditation [COA], 2007). This particular area of regulation is important to prevent a bait-and-switch scheme in which families have an expectation for adoption fees and then those costs escalate over time in a leveraging of prospective parents as they become attached to a particular child.

Other areas of improvement, at the agency level, include child placement standards for case planning (a case management requirement), preadoption training of families (with 10 verified educational hours), ICA adoption training of agency personnel (high-quality staff development and training activities), and ethics in general. In the United States, these areas are covered in agency accreditation standards with clear obligations to provide evidence (e.g., training certificates and case plans; COA, 2007).

Another practice area is the preparation of individuals and couples to be culturally aware and ready to integrate culture into adoptive family life. Although some agencies are more committed to this aspect of care than others, Bailey (2006) identifies a practice model that “promotes assessment of parents’ cultural understanding, education of children’s identity needs, and provision of resources and support for their education of the child’s birth culture” (7). In this model, adoption agency staff become knowledgeable and deliver culturally competent services. In addition, in the best cases, adoption agency staff members provide support for parents as “cultural vanguards for their internationally adopted children” (7), and they perform their professional work based on standards promoting (not undermining) the best interest of the child.

Some agencies have transformed into far more effective and ethical organizations than others; however, fundamentally, agency accreditation has been the most important practical change in the United States as a result of the HCIA. Under this new system, financial transparency requirements not only protect children from being sold into ICA but also provide prospective adoptive families greater protections, too. For example, one family’s fees may not be used to pay for services related to another family’s adoption (COA, 2007). This safeguards application fees on a per-case basis so that if an agency is suffering mismanagement or some other crisis, money cannot be moved from one case to another without accountability. Even with greater financial transparency, there is no actual official documentation of average ICA costs, but it is known that commonly prospective families pay as much as US$25,000–40,000. Costs vary depending on the sending country and circumstances as well as agency operating procedures.

Another critical requirement is that agencies must have funds set aside for the operational budget (several months of monthly expenses) for unforeseen problems and difficult financial times. Furthermore, agencies now must have appropriate insurance and bonding (COA, 2007). All of these steps help to ensure that agencies are managing financial resources in a manner that protects individuals and families, including the children identified for adoption.

Additionally, professional standards include oversight and supervision by qualified professionals, most often master’s level social workers (MSWs) with both credentials and appropriate experience. Also, when an agency is evaluated for accreditation, complaints against the agency are reviewed, including complaint documentation, held by state child placement licensing authorities (COA, 2007). This is a particularly important element of agency evaluation as complaints are reviewed and queried as appropriate.

Finally, under the IAA (2000), adoption service providers and professionals can be prosecuted for child trafficking. Although no such convictions under this particular law have been made to date, the message is clear for all of those engaged in ICA. Adoption agency directors and their boards of directors now may be held accountable for the practices taking place under their administration (Rotabi, 2008). As a result, the obligation to supervise those working both in the United States as well as the second country is taken more seriously with regulatory controls. This is particularly true in terms of supervising those providers in a low-resource area where graft and corruption often is pronounced (COA, 2007). As a result, there are multiple agency vulnerabilities in terms of force, fraud, and coercion (Smolin 2004, 2006).

Although the HCIA is an important step forward, concerns about the implications, at the agency level, have been raised. Bailey (2009) conducted a study with agency personnel providing adoption and ICA services; the study analyzed both the intended and unintended consequences of ICA practices during HCIA implementation in the United States. Most participants considered that the new regulations would provide safer and better adoption practices for families and children, particularly through the standardization of procedures and agency transparency, and the reduction of fraud and corruption. Some expressed concerns over the increased costs of insurance and administrative burden adoption agencies would be required to assume, and the danger of displacing small agencies out of ICA operations, regardless of their ethical performance. In addition, the increased paperwork required from prospective adoptive parents could make the adoption process more costly and cumbersome for everyone involved, possibly making the wait for legitimately adoptable children even longer than before (Bailey, 2009). This concern about a child waiting longer for adoptive placement, in the post-HCIA era, is a legitimate concern and it will be addressed later in the chapter.

Impact of the Hague Convention on Birth Families

Social protection of the most vulnerable is the goal of the HCIA and birth family rights are considered and preserved throughout the international private law. Protections are oriented to appropriate social casework and family support taking place before a child’s departure from his or her country of origin. The idea of a continuum of care—oriented to preserving the child’s social and cultural life in their family and community of origin—was discussed earlier when considering the implementation of the Hague Convention in Guatemala. And, although this approach may seem straightforward, there are many challenges at the practical level, when one accounts for the vast differences among the countries of origin.

As a result, the Hague Permanent Bureau has also provided a Guide to Good Practice (HCCH, 2008), which was developed by adoption and legal experts. Practical recommendations are presented, including a macro-orientation to the bureaucratic structures and policies necessary for regulation to prevent improper financial gain. The requirement for a Central Authority in each country is given consideration as an oversight body; a collaborative relationship between the two Central Authorities involved in one child’s case is included in this process. Additionally, direct practice implementation guidance is provided, including ethical consent and relinquishment processes (obtaining consents without inducements), unbiased counseling, the prevention of improper financial gain, legal processes (including necessary documentation of identity and preservation of child and family social history), and so forth.

Impact of the Hague Convention on Adoptive Families

The HCIA has affected adoptive families in various ways. Improved practices include training of families in the necessary knowledge about the medical and emotional needs of children. Furthermore, cross-cultural considerations are presented to families. With appropriate training as well as enhanced support of adoption agencies—as required by accreditation standards (COA, 2007)—families are now more likely to identify special needs earlier and to seek help from relevant professionals. For example, families now receive detailed information about attachment disorders and medical risks. Also, supportive resources and referrals to services, when necessary, are now an expectation as a clear and reliable service area of adoption agencies. This is an area of system strengthening that supports adoptive families as well as holds them accountable for seeking social care, when necessary.

Another area of impact on adoptive families is the prerequisite home studies (Crea, 2012). Standards for home studies have improved considerably with far greater controls in place to verify backgrounds; financial ability to adopt, including appropriate health insurance; and other critical areas of adoption readiness (COA, 2007). Motivational factors for the individual’s or the couple’s desire to adopt are considered to ensure that the adoption placement is truly appropriate in terms of a child’s permanency in their new family system. Improvements in home studies is one of the most obvious areas of impact in terms of interface with adoptive families—completing a HCIA-compliant home study is not an insignificant task and the individual’s or the couple’s motivation to adopt inevitably is tested during this intensive assessment process. Now, the process is far more holistic and detailed, and the home study is even worded with legal language not unlike a legal affidavit.

Finally, individuals and couples involved in ICA are now far more knowledgeable about their roles and responsibilities in the prevention of child buying. Although it may be argued that knowledge alone does not prevent corruption, the reality is that roles and responsibilities are now outlined by adoption agencies. Any family that engages in graft and corruption, such as offering a bribe, now does so with full knowledge that they are in violation of the law. This is an enhancement of previous practices, before HCIA implementation, in which families were largely unaware of the dark side of ICA in impoverished countries. When families found themselves navigating difficult ethical terrain in the past, in the pre-HCIA era, they were not armed with the necessary knowledge to manage their behavior in the context of a low-resource nation. It is an overreach to say that knowledge alone is enough, but families now enter into the ICA transaction with enough information to be held appropriately accountable if and when a problem arises.

IMPACT OF THE HAGUE CONVENTION ON CHILD DEVELOPMENT

In academic literature, child development has received considerable attention, and the developmental gains and health recovery of most adoptees, after placement into their adoptive families, is astounding (Dalen, 2012; Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2012; Miller, 2012). Note, however, that the Hague Convention does not specifically address child development outcomes; rather, it sets forth regulatory approaches to ethical adoptions as necessary to secure human rights and set forth a positive trajectory of growth and development, in cases in which the child is appropriate for ICA. As such, targets for child development and healthy growth in general are not explicitly outlined in the HCIA. At least two areas of concern, however, are worthy of a closer look: issues of child attachment and attachment disorders in addition to transracial and transcultural dimensions.

Child Attachment and Attachment Disorders

Attachment disorders are a pronounced area of concern that occurs more frequently for children who have experienced child abuse, neglect, and institutionalization. As touched on earlier, one of the major critiques of the HCIA is bureaucratic delays in processing of children who meet the criteria of an ethical ICA, thereby exposing them to further damage associated with institutional care, including attachment disorders (Bartholet & Smolin, 2012).

Howe (2006) has defined attachment as a “system of protection at times of danger,” adding that attachment behaviors are triggered “whenever the highly vulnerable human infant experiences anxiety, fear, confusion, or feelings of abandonment” (p. 128). Attachment disorders and trauma have been found to be associated with long stays in institutions and the abuse and neglect to which children adopted internationally may have been exposed, which can cause antisocial behavior and learning disabilities after adoption (Stelzner, 2003). Even when children are adopted young, trauma and broken attachments may result in serious socioemotional problems related to attachment disorders (Roberson, 2006).

Transracial and Transcultural Dimensions

The intrinsic nature of ICA as transracial and transcultural became visible in high-resource countries engaged in ICAs, such as the United States. Bailey (2006) asserts that adoption in the United States should be seen as a history of both, interracial and transracial adoption. Historically, the preference of U.S. prospective adoptive parents has been for young, healthy, light-skinned children from foreign countries, with a majority of adopted children being girls (Barrett & Aubin, 1990). One of the major reasons more girls have been adopted historically is China’s major role as a country of origin. That country’s one-child policy has resulted in more abandoned girl children in the past. More recently, the demand for darker skinned children from countries in Africa has become a dynamic.

Hollingsworth (2008) points out that identity with a cultural group is a critical element of children’s developmental outcomes, particularly when physical characteristics of the adoptee differ substantially from their family. Underscoring racial difference is important; the majority of families who adopt are white, whereas most children available for adoption are of color. The presence as a child of color in a white family is remarkable. Research indicates that some internationally adopted children report their “wish to be white like their parents and peers” (Juffer & Tieman, 2012, p. 212).

Often adoptive families and the children receive marked social attention (both positive and negative) as they go about their daily lives. As a result, children adopted internationally, as well as their families, have little ability to just blend in and live with the privacy of their adoption. It is a remarkable feature of the family system and many outsiders respond with comments like “you are so lucky” (referring to an impoverished background or birth family and subsequent rescue) or other remarks may be less direct but indicative of misinformed assumptions about ICA, including ideas like “you must be thankful” (Hopgood, 2010). There are also more subtle experiences of difference and discrimination in the greater society; some problems related to race are profound in terms of identity, self-esteem, and adoptee outcomes.

Hubinette (2012), a Swedish adoptee of color and researcher, asserts that racial issues among transnational adoptees of color tend to become the “elephant in the room” that often adoptive families ignore and do not want to talk about. He asserts that a white colorblindness occurs, excluding the cultural identity of adoptees, while defending and legitimizing the proposition that ICA is “successful.” Hubinette (2012) takes a highly critical position when he further points out that this framing parallels a profitable adoption industry, underscoring the utility of such a narrative in further perpetuating a practice that he views as largely exploitative.

Turning to the evidence, Hubinette points out damning evidence in Sweden where international adoptees living in Sweden experience higher rates of substance abuse, criminality, and mental illness, and the statistics for the latter are startling. According to Hubinette (2012), “in fact, no other demographic subgroup in Sweden has a higher suicide rate than adult intercountry adoptees, as completed suicide is four to five times higher among the group than among the Swedish majority population” (p. 224). Poor adoptee child and later adult adoptee adjustment in this largely racially homogenous society of Sweden—where people of color live with great difference and discrimination according to Hubinette—requires critical discourse and social policy considerations in this Nordic country and elsewhere. This is an area for additional transracial adoption research with outcomes oriented toward adult adoptees and their mental health, including morbidity and mortality rates.

CULTURAL COMPETENCE IN SOCIAL WORK AND ICA PRACTICES

The ecological model, strengths perspective, and empowerment theory are at the heart of culturally competent practice in social work (Browne & Mills, 2011). A truly culturally competent model requires a paradigm shift to “multiculturalization” in social work practice (Fong, 2011). It must include an “intersectional culturally humility perspective” or the ability to embrace diversity, an openness to reflective learning, and the acceptance of cultural differences (Ortega & Faller, 2011). Cultural humility may be the result of systematic self-evaluation and self-critique of the power dynamics inherent in the client–patient relationship (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998), and this humility may be obtained through a variety of cross-cultural exposures, including international voluntary experiences (e.g., Schuldberg et al., 2012) or work with immigrant and refugees in the United States. A cultural competence model for ICA must aim at enhancing cultural awareness, enabling knowledge acquisition, developing critical skills, and inducing learning; it must promote biculturalization of interventions with adoptees and their families, and it must include constant monitoring of personal and organizational progress toward aiming that competence (Fong, 2011). In fact, cultural competence is considered a “relational, dialogical process (a dialogue rather than an emphasis of worker’s competence) between worker and the client, between cultures, and between people and contexts” (Lum, 2011, p. 3). Cultural competency in social work requires the consideration of various functions (practitioner, agency, community levels) as well as the various dimensions (micro, meso, and macro levels) of the model, and ethical standards and competencies must be upheld in the profession to engage in culturally competent practice (Lum, 2011).

Attending to guidelines, two models for ICA practices are considered here. Vonk (2001) argues that although parents have “to transform a particular set of attitudes, knowledge and skills into the ability to meet their children’s unique racial and cultural needs … [social workers] must engage in a long-term development process towards cultural competence” (p. 248). Racial awareness, multicultural planning, and survival skills are necessary components of that culturally competent parenting practice, which must include pre- and postadoptive training (Vonk, 2001). Baden and Steward (2000) offer a model for understanding and nurturing cultural and identity experiences within transracial and transcultural adoptive families, which takes account of parents, as well as extended families, and their social and environmental contexts. The model identifies sixteen

identities of transracial adoptees and are made up of the degrees to which they have knowledge of, awareness of, competence within, and comfort with their own racial group’s culture, their parents’ racial group’s culture, and multiple cultures as well as the degree to which they are comfortable with their racial group membership and with those belonging to their own racial group, their parents’ racial group, and multiple racial groups of those reared in racially and/or culturally integrated families. (p. 309)

These models exemplify the application of cultural competence principles in ICA practice. Thus, a culturally competent practice in ICA must consider the interaction of transracial and transcultural adoptive parents with their internationally adopted children, as well as the relationships between those families formed through ICA and their agency service providers.

In spite of the importance of developing culturally competent approaches in ICA practices, the Hague Convention, as enacted in the United States, requires only 10 hours of training for prospective adoptive parents, among which cultural competency is only one of suggested and not required contents (COA, 2007). Furthermore, training of agency personnel has the same ambiguity—cultural competence as a suggested area rather than absolute requirement. This area of training obligation in U.S. agency practice is loose as standards lack clear expectations (COA, 2007), allowing for agency discretion to choose from among a range of training topics, rather than an absolute requirement based on best practices in family–child adjustment and adoptee outcomes.

CONCLUSION

This chapter provided an overview of policy and practical implementation of protective measures for ethical adoption practices, according to the HCIA. The backdrop of illicit adoptions offers illustrative examples, providing a basis from which to focus on how to regulate ICA practice. This chapter highlighted some of the major characteristics of adoption practices, using experiences in Guatemala and the U.S. implementation of the Hague Convention as case examples. In doing so, some of the issues of HCIA implementation are highlighted, including the fact that joining the international private law does not guarantee future ICA from a particular country.

Guatemala serves as a reminder that even signing the Hague Convention may result an indefinite moratorium for implementation so that the country can develop a consistent and humane alternative care and domestic adoption system.

We do not present the Hague Convention as a panacea. In fact, as authors, we know of no example of justice being fully served in cases of child sales or abduction gone before a court as a result of HCIA-related laws. This is poignant in regards to the biological family awaiting their daughter’s return to Guatemala—there is simply no justice in this case thus far. As a result, we conclude that the HCIA ultimately lacks true and meaningful enforcement in these sorts of cases.

Furthermore, although there are useful theoretical frameworks and practical examples to improve ICA practices, we recognize that the market forces make these improvements difficult to implement, as the unscrupulous entrepreneurs continue to exploit children and their families as orphans are constructed through various means of child laundering. Upon conducting an analysis of the decline in ICA, Selman (2012) lamented that even more creative methods and nefarious practices may emerge as the demand for healthy children continues with even greater pressure from the marketplace. One may argue that the child rescue attempts in postearthquake Haiti and the war-torn region of Sudan are examples of creative means of child abduction into adoption in this post-HCIA era, as discussed previously.

Although new illicit practices have not yet become apparent in documented trends, the sheer finances behind force, fraud, and coercion are not to be underestimated. This is particularly true across a range of low-resource countries that may have signed and ratified the HCIA, but remain largely lawless in the real or practical application of child protection laws and family support policies and practices. Currently, this is a concern in Cambodia as the United States may soon lift its moratorium. Extreme poverty and scant child protection systems, however, remain a serious problem in a country that has a notorious history of ICA fraud. Fundamentally, it is difficult for a destination country, like the United States, to truly enforce HCIA policies when a country of origin has limited resources and child protection capacity in terms of a solid partnership in ethical ICA.

Lastly and importantly, concerns about the slowdown of the adoption process are legitimate when one considers children languishing in institutional care or other difficult circumstances as they wait for an adoptive placement. Developing both ethical and efficient systems are imperative to address this problem. Although ICA offers an alternative to less than 1 percent of all orphaned and vulnerable children in the world, the overall positive outcomes of an ethical and successful ICA cannot be underestimated. For it is the right of every child to grow up in a family environment.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. What are the core problems with seeking informed consent from an impoverished birth mother who is interfacing with adoption agency representatives from high-resource countries?

2. Corruption is a problem in intercountry adoption (ICA). How may a social worker act in an unethical manner to “push through” an adoption case?

3. How might prospective adoptive parents become victims of fraud during the ICA process, especially as they interface with officials in a low-resource country? How might they become victims of fraud when interfacing with an unethical adoption agency?

REFERENCES

Africa Child Policy Forum. (2012). Africa: The new frontier for intercountry adoption. Addis Ababa: Author.

Baden, A. L., & Steward, R. J. (2000). A framework for use with racially and culturally integrated families: The cultural-racial identity model as applied to transracial adoption. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 9(4), 309–336.

Bailey, J. D. (2006). A practice model to protect ethnic identity of international adoptees. Journal of Family Social Work, 10(3), 1–11. doi:10.1300/J039v10n03_01

Bailey, J. D. (2009). Expectations of the consequences of new international adoption policy in the U.S. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 36(2), 169–182.

Ballard, R., Goodono, N., Cochran, R., & Milbrandt, J. (in press). The intercountry adoption debate: Dialogues across disciplines. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Bartholet, E., & Smolin, D. M. (2012). The debate. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 233–251). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Barrett, S., & Aubin, C. (1990). Feminist considerations of intercountry adoptions. Women and Therapy, 10(1–2), 127. doi:10.1300/J015v10n01_12

Bergquist, K. J. S. (2012). Implications of the Hague Convention on the humanitarian evacuation and “rescue” of children. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 43–54). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Boéchat, H. (2013, July 6). The grey zones of intercountry adoption: When adoptability rules are circumvented. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on Adoption (ICAR4), Bilbao, Spain.

Browne, C., & Mills, C. (2011). Theoretical frameworks: Ecological model, strengths perspective and empowerment theory. In R. Fong & S. B.C.L. Furuto (Eds.), Cultural competence practice: Skills, intervention and evaluation (pp. 10–32). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Bunkers, K. M., & Groza, V. (2012). Intercountry adoption and child welfare in Guatemala: Lessons learned pre and post ratification of the 1993 Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Cooperation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 119–131). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Bunkers, K. M., Rotabi, K. S., & Mezmur, B. (2012). Ethiopia: Intercountry adoption risks and considerations for informal care. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 131–142). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Casa Alianza, Presidential Commission for Human Rights (COPREDEH), Myrna Mack Foundation, Survivors Foundation, Social Movement for the Rights of Children and Adolescents, Human Rights office of the Archbishop of Guatemala, and the Social Welfare Secretariat. (2007). Adoptions in Guatemala: Protection or market? Guatemala City, Guatemala: Casa Alianza Publications.

Crea, T. M. (2012). Intercountry adoptions and home study assessments: The need for uniformed practices. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 265–272). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Dalen, M. (2012). Cognitive competence, academic achievement, and educational attainment among intercountry adoptees: Research outcomes from the Nordic countries. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 199–220). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Dowling, M., & Brown, G. (2009). Globalization and international adoption from China. Child & Family Social Work, 14(3), 352–361. doi:10.1111/j.1365–2206.2008.00607.x

Estrada Zepeda, B. E. (2009). Estudio Jurídico-social sobre trata de personas en Guatemala [Socio-judicial study on human trafficking in Guatemala]. Guatemala City, Guatemala: Fundación Sobrevivientes [Survivors Foundation].

Fong, R. (2011). Culturally Competent Social Work Practice: Past and Present. In R. Fong & S. B.C.L. Furuto (Eds.), Cultural competence practice: Skills, intervention and evaluation (pp. 1–9). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Freundlich, M. (2000). Market forces: The issues in international adoption. In M. Freundlich, Adoption and ethics (pp. 37–66). Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America.

Fronek P. (2006). Global perspectives in Korean intercountry adoption. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 16, 21–31.

Gibbons, J. L., & Rotabi, K. S. (Eds.). (2012). Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes. Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH). (2008). The implementation and operation of the 1993 Hague Intercountry Adoption Convention: Guide to good practice. Retrieved from http://www.hcch.net/upload/wop/ado_pd02e.pdf

Hollingsworth, L. D. (2003). International adoption among families in the United States: Considerations of social justice. Social Work, 48, 209–219.

Hollingsworth, L. D. (2008). Commentary: Does the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption address the protection of adoptees’ cultural identity? And should it? Social Work, 53, 377–379.

Hopgood, L. (2010). Lucky girl. New York: Algonquin Books.

Howe, D. (2006). Development attachment psychotherapy with fostered and adopted children. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 11(3), 128–134.

Hubinette, T. (2012). Post-racial utopianism: White color-blindness and “the elephant in the room”: Racial issues for transnational adoptees of color. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 221–229). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Johnson, K. (2012). Challenging the discourse of intercountry adoption: Perspectives from rural China. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 103–118). London, England: Ashgate Press.

Johnson, K., Banghan, H., & Liyao, W. (1998). Infant abandonment and adoption in China. Population and Development Review, 24(3), 469–510. doi:10.2307/2808152

Juffer, F., & Tieman, W. (2012). Families with intercountry adopted children: Talking about adoption and birth culture. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 212–220). London, England: Ashgate Press.

Juffer, F., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2012). Review of meta-analytical studies on the physical, emotional, and cognitive outcomes of intercountry adoptees. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 175–186). London, England: Ashgate Press.

Lum, D. (2011). Culturally competent practice: A framework for understanding diverse groups and justice issues (pp. 3–47). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Maskew, T. (2004). Child trafficking and intercountry adoption: The Cambodian experience. Cumberland Law Review, 35, 619–638.

McKinney, L. (2007). International adoption and the Hague Convention: Does implementation of the Convention protect the best interests of children? Whittier Journal of Child and Family Advocacy, 6, 361–375.

Mezmur, B. N. (2010, June). The Sins of the saviors: Trafficking in the context of intercountry adoption from Africa. Paper presented at the Special Commission of the Hague Conference on International Private Law. The Hague, Netherlands.

Miller, L.C. (2012). Medical status of internationally adopted children. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 187–198). London, England: Ashgate Press.

Mónico, C. (2013). Implications of Child Abduction for Human Rights and Child Welfare Systems: A Constructivist Inquiry of the Lived Experience of Guatemalan Mothers Publically Reporting Child Abduction for Intercountry Adoption. (Doctoral dissertation). Available from VCU Digital Archives, Electronic Theses and Dissertations, http://hdl.handle.net/10156/4373

Ortega, R. M., & Faller, K. C. (2011). Training child welfare workers from an intersectional cultural humility perspective: A paradigm shift. Child Welfare, 90(5), 27–47.

Roberson, K. C. (2006). Attachment and caregiving behavioral systems in intercountry adoption: A literature review. Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 727–740. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.07.008

Roby, J. L. (2007). From rhetoric to best practice: Children’s rights in intercountry adoption. Children’s Legal Rights Journal, 27(3), 48–71.

Roby, J. L., & Maskew, T. (2012). Human rights considerations in intercountry adoption: The children and families of Cambodia and the Marshall Islands. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 55–66). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Rotabi, K. S. (2008). Intercountry adoption baby boom prompts new U.S. standards. Immigration Law Today, 27(1), 12–19.

Rotabi, K. S. (June, 2010). From Guatemala to Ethiopia: Shifts in intercountry adoption leave Ethiopia vulnerable for child sales and other unethical practices. Social Work and Society News Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.socmag.net/?p=615

Rotabi, K. S. (2012b). Fraud in intercountry adoption: Child sales and abduction in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Guatemala. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes (pp. 67–76). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Rotabi, K. S. (2012c, October). The Second Russian-American Child Welfare Forum: Opening remarks of the Russian child rights commissioner about intercountry adoption, responses, and the spirit of child protection collaboration between the two nations. Retrieved from http://www.socmag.net/?p=776

Rotabi, K. S., Armistead, L., & Mónico, C. C. (in press). Sanctioned Government Intervention, “Misguided Kindness,” and Child Abduction Activities of U.S. Citizens in the Midst of Disaster: Haiti’s Past and its Future as a Nation Subscribed to the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption. In R. Ballard, N. Goodno, R. Cochran, & J. Milbrandt, (Eds.), The Intercountry Adoption Debate: Dialogues Across Disciplines. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Rotabi, K. S., & Bergquist, K. J. S. (2010). Vulnerable children in the aftermath of Haiti’s earthquake of 2010: A call for sound policy and processes to prevent international child sales and theft. Journal of Global Social Work Practice. Retrieved from http://www.globalsocialwork.org/vol3no1/Rotabi.html

Rotabi, K. S., & Gibbons, J. L. (2012). Does the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption adequately protect orphaned and vulnerable children and their families? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(1), 106–119. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9508-6

Schuldberg, J., Jones, C. A., Hunter, P., Bechard, M., Dornon, L., Gotler, S., Shouse, H., & Stratton, M. (2012). Same, same but different: The development of cultural humility through an international volunteer experience. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(17), 17–30.

Seigal, E. (2011). Finding Fernanda: Two mothers, one child, and a cross-border search for truth. Oakland, CA: Cathexis Press.

Selman, P. (2012). The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century: Global trends from 2001 to 2010. In J. L. Gibbons & K. S. Rotabi (Eds.), Intercountry adoption: Policy, practice, and outcomes (pp. 7–28). Surrey, England: Ashgate Press.

Smolin, D. M. (2004). Intercountry adoption as child trafficking. Valparaiso University Law Review, 39, 281–325.

Smolin, D. M. (2006). Child laundering: How the intercountry adoption system legitimizes and incentivizes the practices of buying, trafficking, kidnapping, and stealing children. Wayne Law Review 52(1), 113–200. Retrieved from://works.bepress.com/david_smolin/1

Stelzner, D. M. (2003). Intercountry adoption: Toward a regime that recognizes the “best interests” of adoptive parents. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, 35(1), 113–152.

Tervalon, M., & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competency: A critical distinction in defining physical training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and the Underserved, 9(2), 117–125.

United Nations. (2000). Rights of the child—report of the special rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, Ms Ofelia Calcetas-Santos. Retrieved from http://poundpuplegacy.org/node/30853

Vich, J. (2013, July 8). Realities and imaginaries on the Chinese transnational adoption program. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on Adoption (ICAR4), Bilbao, Spain.

Vonk, M. E. (2001). Cultural competence for transracial adoptive parents. Social Work, 46(3), 246–255.