BRUCE D. PERRY, ERIN HAMBRICK, AND ROBERT D. PERRY

BRUCE D. PERRY, ERIN HAMBRICK, AND ROBERT D. PERRYTHROUGHOUT HISTORY, HUMANKIND HAS USED adoption—both “legal” and informal—to maintain and sustain family, community, and culture. Many factors contribute to the choice to adopt but, in its current manifestations, a primary factor remains the powerful positive emotional and social features, including empathy. The act of “adopting”—caring for the child (or offspring) of another parent as if they are your own—is a remarkable manifestation of love and empathy. Other species adopt; indeed, there are examples of cross-species adoption in the natural world (Holland, 2011). A central feature of adoption—in humans and other animals—is the expression of mutual, reciprocal affection. The adopter and adoptee both give and receive pleasure from the relational interactions. The mutual capacity to envision, manifest and grow a powerful emotional connection is at the heart of the successful adoption. This process—forming and growing a sustaining love—can be challenged by many trauma- and neglect-related effects on the development of the adopted child. Unfortunately, children who are adopted often have experienced maltreatment and other developmental adversities that affect the child’s relational capacities. This chapter will examine the impact of these developmental adversities on the child’s neurobiological development and explore the clinical implications of these adverse experiences in context of intercountry and transracial adoption.

SCOPE AND CONTEXT

Between 1999 and 2005, intercountry adoption became increasingly common in the United States, with 142,409 children identified as internationally adopted by the U.S. Department of State (n.d.). It is estimated that 70 to 90 percent of internationally adopted children are transracial adoptions (Lee, 2003). As will be discussed, earlier adoption is associated with better outcomes; unfortunately fewer than 20 percent of intercountry adoptions take place before the age of 1 year old (Johnson, 2002). Between 2006 and 2012, rates of intercountry adoption slowly decreased with only 99,530 children adopted within this seven-year span. This decrease in rates may be related to increased regulatory hurdles, such as intercountry adoption regulations fees; and, in part, to an increased awareness of the difficulties faced by families who have adopted internationally.

Preadoption Adversity

The majority of intercountry adoptees have experienced some form of adversity during development. An estimated 85 percent of internationally adopted children were institutionalized at some point (Loman, Wiik, Frenn, Pollak, & Gunnar, 2009). Early studies of institutionalized children documented less-than-ideal developmental environments (Mason & Narad, 2005; Spitz, 1945, 1946). Although each institution was somewhat different, well-intended but developmentally destructive practices were common, and in some settings remain so. Historically, orphanages were disease ridden and to minimize the spreading of disease, children were kept from playing with one another and frequently left alone in cribs, rarely handled by caregivers except for during feeding and changing. Rocking, touching, and speaking to the children rarely occurred. Institutions tended to be devoid of social interactions, relying on consistent routines with low ratios of caregiver to child (e.g., one caregiver for thirty or more infants). These practices persist in many settings. A recent study by Groark, McCall, and Fish (2011) evaluated the characteristics of several Central American orphanages. Most were found to be clean but had minimal staff–child interactions. The interactions that did occur lacked emotional responsiveness to the individual needs of the children. Staff worked long hours and frequently rotated between wards, leading to a lack of consistency in caregiving, all with minimal physical and sensory input. Children were not encouraged to play together, further decreasing social interactions.

Although not a certainty, many institutionalized children have had other developmental challenges—such as prenatal exposure to alcohol, neglect, traumatic stress, and attachment disruptions—all of which are known to impact the development of the brain and lead to a range of complex cognitive, emotional, behavioral, social, and physiological problems (Anda et al., 2006; Perry, 2008) that appear to be overrepresented in samples of international adoptees (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2008; Johnson, n.d.; Juffer & van Ijzendoorn, 2005; Loman et al., 2009). The risk of in-utero exposure to stress hormones and teratogens, such as alcohol and drugs, is estimated to be close to 60 percent (McCarthy, 2005). Furthermore, the probability that the immediate perinatal period before institutionalization was in chaotic, higher risk environment with less-than-ideal attachment experiences remains high. These early risks for attachment development are compounded in children who spent their first months or years in institutions with poor staff-to-child ratios and socially sterile environments.

Functional Consequences of Developmental Adversity

The emotional, social, cognitive, and physiological consequences of this kind of complex and multidimensional developmental trauma are significant and heterogeneous (De Bellis, 2005; Nelson, Bos, Gunnar, & Sonuga-Barke, 2011; Perry, 2002). When examining “international” adoptees as a group, statistically significant risks are seen for a host of problems. It is difficult to take general findings from grouped data, however, and apply to the individual child. Each child has a unique set of genetic gifts (or challenges) and epigenetic, prenatal, perinatal, and early childhood experiences; the behaviors of one institutionalized child may greatly differ from that of another. Following adoption from an international institutional setting, a child may have problems with attention, but many will not; a child may have problems with learning, but many will not; a child may have difficulties with relationships, but many do not. This complexity requires a careful examination of the individual’s developmental history (as well as it can be determined) and current set of strengths and vulnerabilities (Perry, 2009).

With this caveat, taken as “group,” a range of behavior problems and social skills deficits has been found in this population. These behavior problems are interrelated with cognitive challenges (Groark et al., 2011; Loman et al., 2009). Cognitive flexibility often is undeveloped in these children. These executive functioning impairments are common in maltreated children (Moffit et al., 2011; Piquero, Jennings, & Farrington, 2010). Some institutionalized children have been described as having “institutional autism” due to their difficulties reading and interpreting social nuances, mimicking the emotional responses of others, and demonstrating primitive self-soothing (O’Connor, Rutter, & English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team, 2000; Rutter et al., 1998). Many issues may not become evident until adolescence (Johnson & Gunnar, 2011) and can be confusing to caregivers who generally have seen typical development in their adopted child before this time.

Many institutionalized children may exhibit behavioral paradoxes (see “The Clinical Challenge”). In one moment, the child may demonstrate independent or even “parentified” behaviors and prefer to self-soothe, feed himself (or hoard food), and avoid physical affection, while in the next moment he may act completely infantile and seek physical comfort, rocking or even bottle-feeding. Others may seem to require affection at all times and exhibit separation fears as well as the inability to complete tasks independently. Impairments in self-regulation, or the ability to self-soothe when stressed, transition between novel tasks, persevere when challenged, and make adaptive behavioral choices likely will exist but will differ depending on the task and the context. For example, many children may find situations with high-intimacy expectations (such as family time) to be highly dysregulating and thus may exhibit poor self-regulation in the home, even though they are able to excel in less intimate school or daycare environments (see “The Clinical Challenge”; MacLean, 2003).

Neurodevelopmental Consequences of Developmental Adversity

One of the fundamental principles of neurodevelopment is “activity dependence”—basically, neural networks (and the functions that they mediate) develop, organize, and function optimally when they receive “appropriate” nature, timing, and pattern of experience. Although there is much to learn about the timing and nature of optimal versus necessary experiences required to express functional potential, it is clear that extremes of neglect, chaos, distress, and traumatic experiences can lead to a range of neurodevelopmental problems (Anda et al., 2006; Perry, 2008).

The mechanisms by which experience influences development takes place at multiple, often parallel, interactive systems, ranging from genome to neural network to whole-organ systems to a family and community. For example, (1) an overwhelming traumatic experience can alter immediate release of neurotransmitter at a range of neural networks associated with the stress response and influence synaptic dynamics leading to changes in local synaptic density and structure; (2) these immediate “adaptive” changes resulting from sensing and processing threat, in turn, working at a micro level, can alter gene expression via a variety of epigenetic mechanisms and lead to long-term changes in gene expression; and (3) working at a macro level will alter widespread neural systems in complex ways (e.g., by creating new “associations” between sensory cues simultaneously present during the traumatic experience). Collectively, these complex mechanisms can mediate long-term alterations at the level of the epigenome, neuron, neural network, broader stress-response systems, multiple organs, and, ultimately, the individual, family, community, and culture. Experiences—both good and bad—have echoes deep, wide, and long and are found deep into our biological core, and so it is with intercountry adoptees.

With the heterogeneous nature of the developmental experiences of the intercountry adoptees, it is not surprising that the few studies examining neurodevelopmental functioning in this population have found significant (but varied) differences from comparison populations (e.g., O’Connor et al., 2000; Rutter et al., 1998; Rutter & English and Romanian Adoptees Studies Team, 1999). Among the findings are altered local brain activity in various cortical areas (Chugani et al., 2001); decreases in brain size (and head circumference) in extreme total global neglect (Perry, 2002); altered connectivity between key brain regions (Eluvanthingal et al., 2006); neuroendocrine regulation differences (Bruce, Fisher, Pears, & Levine, 2009); altered hippocampal, amygdala, and corpus callosum size (Mehta et al., 2009); and various measures of brain electrical activity (Vanderwert, Marshall, Nelson, Zeanah, & Fox, 2010). De Bellis (2005) and Nelson et al. (2011) provide reviews of this small but growing body of research.

THE CLINICAL CHALLENGE

Twenty-five years ago many adoptive parents and their consulting medical teams had minimal understanding of the complex effects of these early life adversities on development. Although landmark studies describing some of the adverse effects of neglect, institutionalization, “psychosocial dwarfism,” and adoption existed (Dennis, 1973; Spitz, 1945, 1946; and, especially, Money’s excellent book from 1994), these were not widely incorporated into routine medical or psychological training. Indeed, the dissemination of these important learnings continues.

These early learnings about the potential challenges of intercountry adoption certainly were not part of the common understanding and awareness of the majority of adoptive parents. Over the ensuing years, the emotional, behavioral, learning, and physical health problems seen in adopted children and youth have stimulated more research and an increase in public awareness of these issues. Again, with the caveat against overgeneralizing to all intercountry adoptees, in several key clinical areas, a neurodevelopmental perspective can be helpful.

Altered Stress-Response Systems

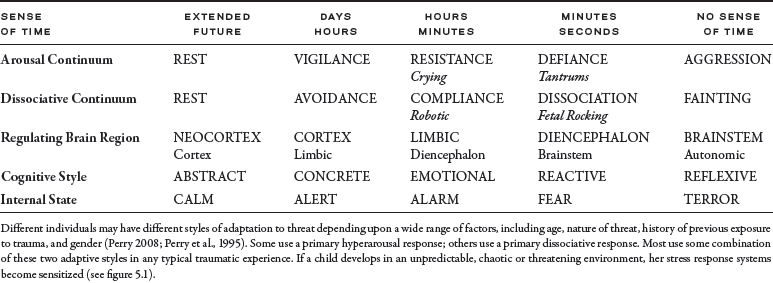

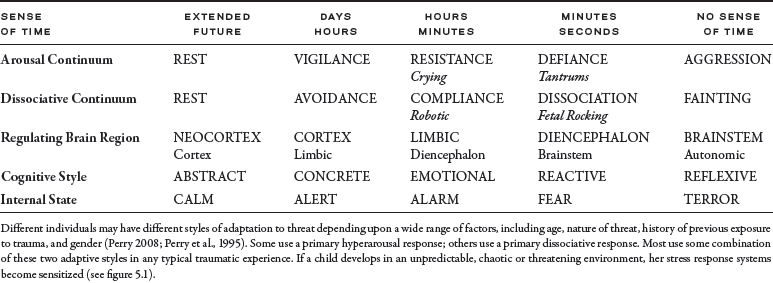

There are two major and interactive adaptive response patterns to significant threat: the arousal response and dissociation. The arousal response activates the individual and prepares them to flee or fight (Perry, 2008; Perry, Pollard, Blakley, Baker, & Vigilante, 1995). Dissociation is less well characterized and is engaged when there is a perception that fighting is futile or fleeing impossible; the dissociative response is more internalizing and is hypothesized to help the individual prepare to survive injury. Peripheral blood flow decreases and heart rate goes down; the release of endogenous opioids and dissociation at the cognitive and emotional level occurs. In many cases, both of these adaptive responses will be activated during the same complex traumatic experience. Both response patterns can become sensitized, such that future stressors or challenges will activate the most common adaptive pattern used in a similar situation in the individual’s past—for example, an infant physically abused in the context of a caregiving relationship who utilized a dissociative response to survive that inescapable painful event may, ten years later, “tune out” when the teacher raises his voice in frustration (see table 5.1).

TABLE 5.1 State-Dependent Functioning

As a child moves along the arousal–dissociative continuum in the face of novelty or threat, the internal state shifts. Different networks in the brain will activate while others deactivate. Although clearly oversimplifying the process, the more threatened the individual feels, the more functioning shifts from higher more complex and mature cortical networks to lower and more reactive systems. In the fearful child, this may manifest as a defiant stance. This typically is interpreted as a willful and controlling child. Rather than understanding the behavior as related to fear, adults often respond to the oppositional behavior by becoming angry and more demanding. The child, overreading the nonverbal cues of the frustrated and angry adult, feels more threatened and moves from alarm to fear to terror. These children may end up in a primitive minipsychotic regression or in a combative state. The behavior of the child reflects their attempts to adapt and respond to a perceived (or misperceived) threat.

Regression, a retreat to a less mature style of functioning and behavior, commonly is observed when we are physically ill, sleep deprived, hungry, fatigued, or threatened. During the regressive response to the real or perceived threat, less-complex brain areas mediate our behaviors. If a child has been raised in an environment of persisting threat, the child will have an altered baseline, such that the internal state of calm is rarely obtained. In addition, the traumatized child will have a sensitized alarm response, overreading verbal and nonverbal cues as threatening. This increased reactivity will result in dramatic changes in behavior in the face of seemingly minor provocative cues. All too often, this overreading of threat will lead to a fight or flight reaction and will increase the probability of impulsive aggression. This hyperreactivity to perceived threat can become a major problem in the home and classroom, impairing both social and cognitive development.

State-Dependent Disruption of Healthy Developmental Experiences

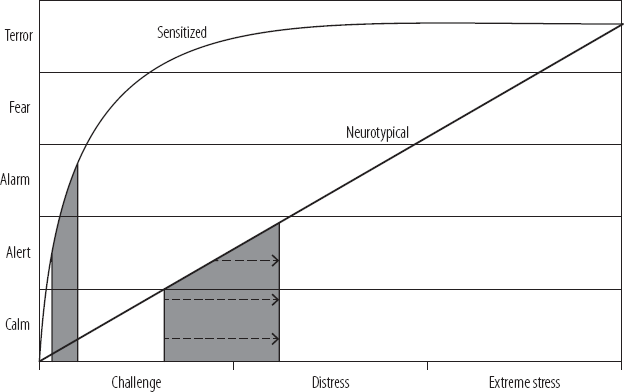

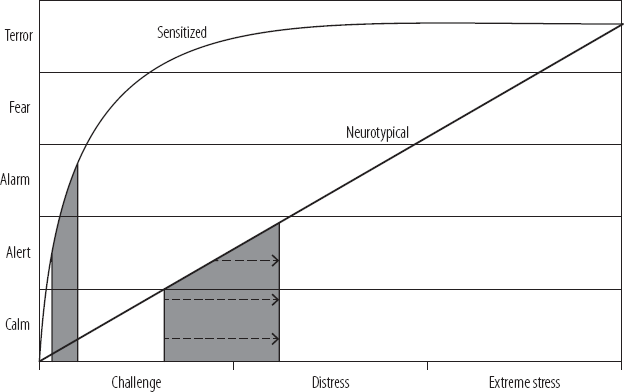

The whole process of development involves the sequential and iterative process of being exposed to new experience, leaving a comfort zone, and ultimately making the once unfamiliar familiar. This process requires activation of the stress-response systems; all novel stimuli will cause the stress-response systems to activate until the new stimulus is categorized. Simply stated—all development and all learning requires doses of stress activation. In typical, healthy developmental circumstances, these tiny doses of stress activation play a role in helping build resilience. Unfortunately, in children with previous developmental adversity, chaos, or trauma, their stress-response systems have become so sensitized that even minor challenges will result in major activation—the transition from play to lunch will elicit a response that would be appropriate for a serious threat, the whisper becomes a shout, and “not now” becomes “never.” The result is a confusing emotional and behavioral overreactivity that often confuses adults, peers, and the child (figure 5.1).

FIGURE 5.1 The Developmental Window: State Dependence. This figure illustrates two stress-reactivity curves; the straight black line indicates a neurotypical relationship between the level of external challenge, stress or threat and the appropriate proportional shift in internal state required to adapt, adjust, and cope with the degree of stress; with minor stressors, there are minor shifts in the internal state and with major stressors a larger shift in internal state is required. The top non-linear curve illustrates the distorted, sensitized stress-reactivity curve that results from patterns of extreme, unpredictable or prolonged stress activation such as is seen in many children from intercountry adoptions. In this case, there is a significant over-activity at baseline and an over-reaction even in the face of relatively minor challenges. Individuals with this level of sensitization require smaller “doses” of challenge. All learning—social, emotional, behavioral, or cognitive—requires exposure to novelty; a novel set of experiences that will, with repetition, ultimately become familiar and then ‘internalized’ or learned. The gray bars indicate the Developmental Window where enough—but not too much—stress activation (an appropriate “dose” of challenge) occurs to promote optimal learning. Too little novelty would lead to little stress activation and minimal learning, while too much activation leads to distress and inefficient internalization of information. With sensitized stress-response systems, the tolerable “dose” of challenge that can move the child into this optimal Developmental Window is very small (see thin gray bar); at the same time a neurotypical child can tolerate a larger “dose” of novelty (thick gray bar). In settings where the adult expectations for what a child or youth “should” be able to tolerate are not informed by an awareness of trauma-related alterations in these stress-reactivity curves, there are frequent misunderstandings that lead to escalation and significant behavioral problems.

The major neural networks involved in the heterogeneous stress responses (see previous discussion) can become sensitized with patterns of activation that are unpredictable, extreme, and prolonged. This pattern of stress activation is common in maltreated and traumatized children—such as many children from international adoptions. When this occurs, the major adaptive style used by the infant, toddler, or child—either the hyperarousal (activate) or dissociation (shutdown) or, in some cases, both styles—becomes overactive and overly reactive. The results are profoundly disruptive for subsequent development as these overreactions to novelty and stress will inhibit and distort the accurate processing of new experiences even if these are predictable, consistent, nurturing, and enriching. A major consequence of this sensitization is that it shifts the state-dependence curve and narrows the developmental window (also known as the learning or therapeutic window; see figure 5.1). Simply stated, to acquire new capacities (i.e., make new associations in neural networks), the individual has to be exposed to novel experiences that, in turn, create novel patterns of neural activity. For optimal development (or learning or therapeutic change) this novelty has to have a “Goldilocks” effect—that is, enough novelty to challenge and expand the existing comfort zone (the set of previously acquired and mastered capabilities) but not so much novelty (or demand) that the capacity of the individual to process and assimilate is overwhelmed. When someone has a sensitized stress-response system, exposure to any novelty or unpredictability can rapidly move the person from active alert to a state of fear, thereby interfering with the process of learning. The more sensitized the stress response, the narrower this therapeutic–learning window is (see shaded areas in figure 5.1) and the less likely it will be that the child can benefit from typical or even optimal developmental experiences. The result is a profound frustration from the seemingly endless number of repetitions required for a child to master a concept or learn a behavior. The key to addressing this problem is to ensure that the child is regulated before expecting her to internalize any new social or cognitive content. A sense of safety is the key to beginning to overcome the sensitized stress responses that can disrupt development; in turn, the most powerful sense of safety comes from the sense of belonging—being part of a relationship, family, community, and culture. Unfortunately, this is one area of significant challenge for many intercountry and transracial adoptees; a core sense of belonging is linked to the fundamental capacity to form and maintain relationships.

CLINICAL EXAMPLE

Edith is a 7-year-old Native American girl who was fostered from age 4 by a Caucasian mother and an African American father and then adopted by them at age 6. Key developmental adversities included prenatal exposure to alcohol, marijuana, and nicotine. She was removed from her biological mother following severe neglect in the first three months of life and lived in a dozen kinship and temporary shelter care and foster care settings during this time. The biological father was never involved in her life. Episodic efforts to establish and support the biological mother failed, and kin (all of them with significant challenges themselves) were unable to cope with the severity of her behavioral problems. During these many placements, Edith experienced additional chaos and trauma, including sexual abuse by an older foster child in one foster home. At the time of entering her ultimate adoptive home (age 4), she was nonverbal, unsocialized, and still in diapers. She had severe sleep problems and hypervigilance, with a profound behavioral reactivity to any challenge, frustration, or transition. Edith demonstrated a set of primitive self-soothing behaviors including rocking herself, biting and sucking her thumb, rhythmic humming, and hoarding of food. Despite her chronological age, she was developmentally below the 18–24 month level in most domains (i.e., cognitive, social, motor, and emotional) as determined by a set of standard developmental metrics and the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics Metrics (NMT; see Perry, 2013).

During the first year in her adoptive home (age 4 to 5), a series of early intervention services were initiated; this included an occupational therapy evaluation with sensory “diet” recommendations, a specialized therapeutic day program (trained in the NMT). She required significant somatosensory soothing from caregivers and her foster/adoptive parents; this typically involved rocking, swinging, therapeutic massage (multiple times during the day for 8–10 minutes). She required a very structured nighttime ritual that involved the use of bathing, brushing teeth, having her hair dried and combed, reading stories, and a 10–12 minute backrub. Despite this she continued to wake during the night several times a week, requiring significant soothing. She was easily upset (especially when she did not have “control” or when there was an unpredictable change in her routine. These episodes occurred multiple times a day on most days in the beginning but decreased to a rate of several times a week by age 6. The duration of these episodes ranged from twenty minutes to three hours. The carers could not identify specific “triggers” on most occasions–aside from the word “no”–or “not getting her way.” Edith entered public school and left the NMT–trained preschool setting at age 6. As she got older, the density of the somatosensory interventions was significantly decreased and her parents and school expected her to start to be more responsive to verbal direction, school and household rules, and age-typical social activities. She seemed to get worse; the rate of severe episodes increased. Consultation with mental health professionals resulted in diagnoses of ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder and she was placed on a series of medications with no apparent positive impact (as is often the case, these clinicians did not view any of these symptoms through a “trauma-informed” lens). After a year of continuing severe symptoms and expulsion from her new school, the family consulted The ChildTrauma Academy.

On initial consultation with her family and clinical team (at age 6.5), we viewed this profound overactivity and over-reactivity in regulation as a predictable result of her chaotic, traumatic earlier life (see table 5.1 and figure 5.1) and related developmental adversities. Her resting heart rate at this time was 120 (significantly elevated and consistent with a child in a persisting high-alarm state (see table 5.1). In addition, Edith’s reactivity (see figure 5.1) was such that minor frustrations (such as “no”) were able to precipitate major behavioral outbursts; transitions were very challenging. Her ability to benefit optimally from the positive cognitive and social experiences provided in the home and school was compromised by her high arousal and high reactivity. As she matured cognitively and developed improved communication skills she asked if she “belonged” to mom or to dad and raised other questions suggesting she was beginning to notice that she “looked” different from both mom and dad.

With this reframing of her problems, school and family resumed a more somatosensory rich, relationally mediated schedule of activities including a schedule of 10–15 minute hand and neck massages, frequent sensory breaks in school, elements of collaborative problem solving and pairing academic lessons (and therapeutic interactions) with rhythm such as music and motor movement (e.g., walking, rocking desk, jump rope). The medications were discontinued with no observed negative effects. Over the ensuing six months the rate and intensity of “meltdowns” decreased; she resumed her earlier positive process of catching up in social and cognitive domains. She was capable of talking about her biological family, her multiple transitions, and her new family. Key recommendations included reconnecting her with Elders and others in her tribe of origin. The whole family was encouraged to participate in any tribal activities with the intent of creating meaningful cultural connections that could help her (and her family) negotiate and celebrate the complex and diverse cultural history that will be part of her life.

The Intimacy Barrier

Humankind is a social species. We have survived and thrived on earth because we can form and maintain relationships to create larger, more functional, and flexible biological systems than the individual—we create families, communities, and cultures. Three of the most essential capabilities required for the survival of our species depend on “relational” neurobiology: the ability to (1) survive, (2) procreate, and (3) protect and support the vulnerable. First and foremost, to survive, a human needs other humans. We are born dependent and rely on the attention and supports (emotional and physical) of the adults in our life to survive. The relational nature of our very survival is obvious for infants and children but even into adult life, success depends on the capacity to connect, collaborate, coordinate, communicate, and be part of our “clan.” A single human can never be truly independent; we are once and always interdependent. Complex neurobiological systems mediate this healthy interdependence. Second, procreation, in turn, is obviously a relational activity that is required for our species to continue. And, finally, there must be some “pull” for us to protect and nurture those in our family and clan who are more vulnerable and less capable of caring for themselves. Some complex neurobiological pull motivates and sustains the exhausted mother as she once again wakes in the night to feed and comfort the crying, needy infant; tens of thousands of times in our lifetime dozens of adults have given us time, energy, attention, and resources that have allowed us to survive and thrive.

These three core essential functional capabilities involve the very same relational neurobiology involved in the core feature of adoption—the creation of a relational connection or bond. Our early experiences with others—especially carers—can shape our relational neurobiology in powerful ways—both good and bad. When these bonds are characterized by mutual affection and love, the process of adoption is easier; yet many adoptions are complicated by challenges in the creation and maintenance of these loving bonds. For many adopted children, their earliest developmental experiences with parents, caregivers, and other human adults were characterized by inconsistency; unpredictability; and, sadly, confusion, threat, pain, and overtly traumatizing experiences. These experiences can influence the development of the core neurobiology required to form and maintain relationships, thereby making future positive relational interactions more difficult to establish and maintain.

A complex set of associations between the stress response, reward, and relational neural networks creates a three-part core of healthy human functioning. This triad of health and resilience is created through thousands of synchronous, mutual relational interactions in the first year of life (Szalavitz & Perry, 2010; Tronick & Perry, 2015). Through the patterned, repetitive bonding interactions of the attentive, attuned, and responsive caregivers with the infant, sensory integration, self-regulation, relational, and cognitive capacities emerge. Early bonding interactions create core “attachment” capabilities and related relational associations. The fundamental neurobiological capacity to create these bonds is a product of our genetic gifts and how these gifts are expressed as a function of the nature, timing, and pattern of relational experiences—especially when we are young.

One of the most interesting manifestations of these primary associations created by your earliest relational experiences is that we will interpret emotions, particularly expressions of fear, in context of our culture of origin (Chiao et al., 2008). The sensory attributes (e.g., skin tone, vocalizations, expressions, facial features) of our family and clan during our early life provide us with the relational templates through which we interpret all subsequent relational experiences. Thus, the sociocultural context changes a child’s expectations for how to interpret his or her world—particularly signals of fear—and how to know when to come to the aid of a group member. Other research has shown that children have ingroup–outgroup biases and that children will consider other children who look similar to them to be nicer and smarter than children who do not (Dunham, Chen, & Banaji, 2013; for more discussion of this, see Szalavitz & Perry, 2010). This tendency to demonstrate bias is likely related to the long history of humankind’s tribalism—throughout history the major threat to humans was other humans. There was, and still remains, a need for ingroup collaboration to help survive outgroup aggression. The implications for transracial adoption are significant; the adopted individual—even when adoption occurs early in life—may not feel safe or accurately interpret emotional cues in the new group. Basically, they may not feel as if they belong. This sense will be exacerbated if there is a history of adversity that involves security and attachment issues and impaired ability to interpret social cues.

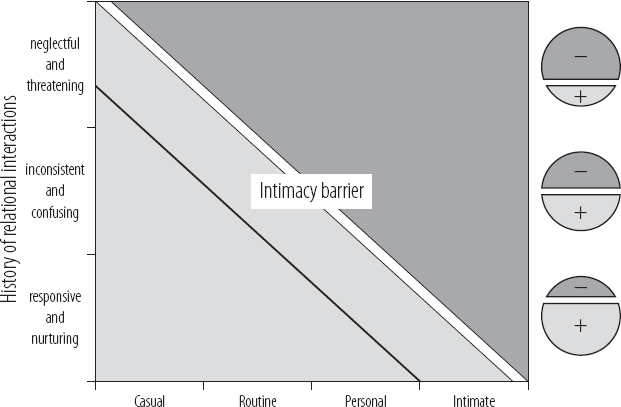

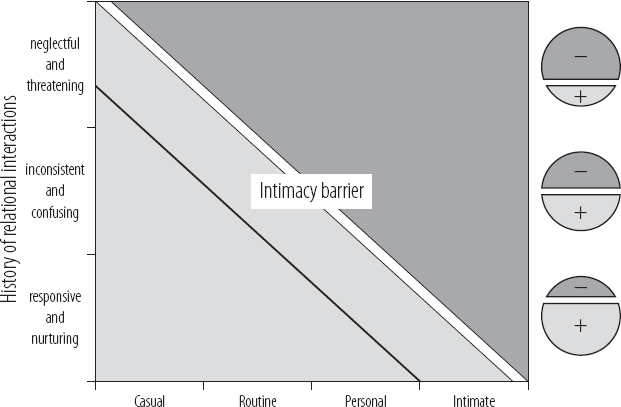

FIGURE 5.2 The Intimacy Barrier. As social interactions shift from casual to routinized (e.g., a structured social setting such as a classroom) to more personal and then finally intimate, the individual will interpret the social interaction in context of the ‘sensitivity’ of their Intimacy Barrier (the tangential white bar separating the dark gray from the light gray portions of the figure). If the individual had generally positive early life relational interactions (bottom “responsive and nurturing” row with larger light-gray “+”), his Intimacy Barrier will be “further out,” making him capable of tolerating casual, routine and personal interactions without feeling threatened and activating a defensive set of responses (see table 5.1). If, however, either the personal or ‘emotional’ space boundary is crossed without permission and a sense of control, even neurotypical individuals feel threatened (see Kennedy et al., 2009). Like all brain-mediated functions, the “Intimacy Barrier” is state-dependent. When an individual feels threatened their sense of personal physical and emotional boundaries (i.e., the Intimacy Barrier) shifts (thin black tangential line). For many children and youth from intercountry adoptions, the combination of relational sensitivity following early life attachment disruptions and a sensitized stress response reactivity lead to very confusing and complex challenges with interpersonal interactions.

A useful clinical concept, similar to the concept of personal space in proxemics (Hall, 1966) is the intimacy barrier (see figure 5.2). As described earlier, the set of early developmental experiences with caregiving adults creates an internal catalog of “associations” with human relational cues (e.g., tone of voice, eye contact, touch) and helps organize key areas of the brain involved in social affiliation and relational functioning, including the amygdala. The size of the amygdala in adult life, for example, a brain area very involved in interpreting and acting on threat related cues, correlates (positively) with the size and complexity of social networks (Bickart et al., 2011).

If the primary carers were present, attentive, attuned, and responsive, the child creates positive associations with human relational cues intended to convey interest, warmth, and comfort. Future positive social interactions with peers, teachers, and carers will be regulating and rewarding as long as they do not cross an invisible “intimacy” barrier. All humans have protective “boundaries” around specific emotional content (e.g., unsolicited conversation about your weight or sexual behaviors) and physical interactions (e.g., personal space, sexualized touch; Hall, 1966).

When this intimacy barrier is crossed without our permission, it is threatening. The stress-response systems (including the amygdala; Kennedy, Gläscher, Tyszka, & Adolphs, 2009) activate, and the individual will engage in protective behaviors; a variety of stress-response strategies may be used depending on the sensitivity of your stress-response system (see figures 5.1 and 5.2) and the adaptive preferences the individual may have developed (see table 5.1; Perry, 1995). If the individual utilizes a flock-freeze–flight–fight response, when someone crosses this barrier, verbalizations (e.g., raised voice, profanity, threats) or behaviors (e.g., pushing, hitting) may be used to attempt to push the offending person back across the intimacy barrier. If the predominant style of adaptation is dissociation, the child will avoid social interactions and, if this is not possible, will passively disengage. This can be confusing for peers, carers, and educators when their intended nurturing behaviors and words are met with either overt hostile and aggressive behavior or indifferent and dismissive attitudes.

For individuals with early life relational history of inconsistent or abusive care (all too common in intercountry adoptions), the set of relational associations created will push the intimacy barrier out further than with typical individuals (see the top “neglectful and threatening” row in figure 5.2). A person with a high degree of relational sensitivity often will misinterpret neutral or positive social interactions from peers as threatening and respond by either avoiding or disengaging (which leads to problems with social learning and peer interactions) or, worse, by using aggressive, hostile, or hurtful words or even behaviors to push peers, teachers, and parents away. In extreme cases, as the child grows up, this relational sensitivity can result in significant antisocial or even assaultive behaviors. Individuals in prison (90 percent of whom have histories of interpersonal trauma in childhood) have a much larger sense of personal space than the average person (Wormith, 1984), and often will respond to personal space violations with aggressive and violent behaviors.

CLINICAL EXAMPLE: RELATIONAL SENSITIZATION

Thomas is a 14-year-old boy adopted from an Eastern European orphanage at age 4 by a family in the United States who had two older biological children (9 and 12 at that time). In the first year in the U.S. he was noted to be in good physical health and seemed shy and somewhat overwhelmed by his new home but there were no major behavioral problems. He was somewhat touch defensive (although he would occasionally spontaneously seek physical affection from his mother). From age 4 to 6, his family provided much developmental enrichment with the intention of helping Thomas transition to a new country, new language, and new home. He had a language tutor, many “developmental” toys and video programs that he seemed to enjoy (possibly too much). He continued to be aloof to social engagement, had poor eye contact, and frequently rocked and quietly hummed when he was in social situations. The family viewed him as quiet and shy. His preference was to watch his “developmental” enrichment videos or play educational games on the computer. He was indifferent to peers in free-play situations and actively resisted their attempts (or adult encouragement) to socialize. His only major behavioral problems occurred when he was forced to stop his video games or when another person (adult, sibling, or peer) attempted to redirect his self-absorbed play. He was able to simply tune out verbal direction or interactions when he was engaged in an activity.

When in social interactions such as playing a game with a sibling, his behavior and mood were appropriate as long as he was in control (the game was of his choosing); he could change the rules to suit him; and he could order his partner around (and the partner would comply). Initially the siblings and parents tolerated this style of play. As he grew older, however, their efforts to teach him to share or follow the rules of the game precipitated odd and disruptive behavior (e.g., screaming, holding his hands over his ears, and rocking). When adults attempted to stop this, he would become very aggressive–biting, kicking, crying, and hitting. If left alone, these odd behaviors would last between 10 and 15 minutes, after which he would seem “fine” and act as if nothing had happened. When an aggressive episode was precipitated it would take over an hour to get back to baseline.

Thomas entered school at age 6. A long-lasting and serious deterioration ensued and his developmental progress plateaued. The episodes grew in frequency and intensity (as the social environment and relationally mediated demands of the teachers, aides, and carers increased). If left to his own devices his behaviors were odd but acceptable; he would make academic progress but in a pace and direction of his own choosing. He responded to imposed structure, redirection, and any physical proximity with a profound meltdown; when the teacher or staff attempted to physically withdraw him from the class (or physically comfort him) he would get aggressive, both verbally threatening and physically attacking them. He was expelled from school after school. Behavior at home deteriorated as well; he began to threaten his mother, especially when she attempted to be comforting or nurturing. Over time the family felt as if they were “walking on eggshells”—never knowing what would trigger Thomas and when he might have an aggressive meltdown.

A long history of failed placement at specialized schools, multiple mental health assessments, a parade of diagnoses (over twelve DSM diagnoses were assigned to him by various clinicians by the age of 13; more than twenty medications were used during this time, many simultaneously administered), and ultimately admissions to psychiatric hospitalizations and placements at residential treatment centers ensued. Along the way, any observed progress was short-lived. He was maintained in a series of out-of-home placements from age 8 to 14. At age 14 his treatment team consulted The ChildTrauma Academy.

Review of his history resulted in a reformulation of the traditional mental health perspective to a developmentally sensitive and trauma aware view. Among other core issues (he did demonstrate sensitized dissociative and hyperarousal behaviors; see table 5.1) was a profound relational sensitization. Physical and socioemotional interactions that might be considered “typical” and tolerable to most people were essentially evocative cues to him (see figure 5.2 and text on the Intimacy Barrier). These well-intended social and physical interactions provoked very reactive responses (see table 5.1 and figure 5.1). When the staff and family learned more about these processes and created parallel, predictable, patient, and regulated interactions where Thomas was given control over the frequency and intensity of intimate social and physical interactions, the number of aggressive episodes decreased and ultimately stopped. With a combination of regulating and relationally mediated educational, therapeutic, and enrichment experiences, Thomas made significant progress over the next six months and was able to return home with special in-home services supported by a developmentally informed school.

The tragic reality is that the maltreated child desperately wants to belong, wants to be loved and connected, but personal and intimate interactions elicit fear not comfort; unless the child initiates and controls the interactions, he or she will feel threatened. And if the child also has a sensitized stress-response system, even small violations of the emotional or personal space can result in extreme behaviors, including threats to kill or injure the parent.

The irony is that the more nurturing and loving the behaviors, the more overwhelming the child feels. These children rarely threaten to go kill a stranger—they threaten to kill the people or person who has been most caring and nurturing. Furthermore, when the threatened adult leaves or attempts to disengage from the disturbing interaction, the child (even as they say they hate you) will follow the adult and get even more dysregulated. This is likely due to the fact that they are not just sensitized to relational intimacy; they are sensitized to unpredictable abandonment. They want you present, but they don’t want you too close; and, if physical or emotional intimacy is to be introduced, they want to be in control. They want to play the game their way; they want to get a hug when they want it; they want to talk about something overwhelming when they bring it up. The primary clinical strategy is to be present, parallel, patient, and persistent—a much easier thing to say than to do day in and day out with a challenging child. The consequences of this complex and somewhat-distorted set of relational associations can be destructive for the creation of the mutual loving bonds required for successful adoption.

These complex interpersonal dynamics are complicated by the additional challenges posed by being “different” (by virtue of ethnicity, race, culture, or country) than the adoptive family. Adopted “children will likely simultaneously occupy multiple positions within the socio-cultural-political and structural fabric of society” (Ortega & Faller, 2011, p. 31). These intersecting group memberships likely will affect quality of life given that the child may struggle more than other children to form an identity, particularly during adolescence, and that the child may feel conflicted between identifying with a culture that feels “right” or “natural” and the culture in which they actually are raised. Bicultural children have been shown to arrive at self-judgments by using different parts of their brain when primed by stimuli associated with one culture versus stimuli associated with the other culture (Chiao et al., 2009). This may indicate that transracial children are often balancing multiple views of themselves and trying out which self-representations are most adaptive in which environments. Despite the fact that this balancing and fluctuating ultimately may be adaptive, it is likely stressful and adds complexity to the social experience. Teasing and bullying by peers may be increased and further confirm that the world in which the child lives is not safe or that the child may not express certain parts of themselves in certain environments. Children may even feel reluctant to share these experiences with their adoptive parents given the perceived stress it might cause the family (Docan-Morgan, 2011).

Children may be better at detecting emotional cues of people with similar backgrounds (Chiao et al., 2009), suggesting that children primed to be hypersensitive to threat may misread signals from unfamiliar cultural groups and potentially perceive threat when it does not exist. Just as institutionalized children have been described as having to learn English as their “second first language” (McCarthy, 2005, p. 9) given that they have language deficits in their native language and then are asked to learn a new language once arriving in the United States, children who have been transracially adopted may have similar struggles when “reading” emotional cues. Their ability to naturally interpret both threat and relational cues may be impaired because of a history of trauma, neglect, or institutionalization, and this impairment is exacerbated by difficulties interpreting facial expressions of unfamiliar racial or ethnic groups. The challenges for these children and their families under these circumstances can be considerable; the question remains what can we do to help?

KEY POLICY AND PROGRAM IMPLICATIONS OF A NEURODEVELOPMENTAL PERSPECTIVE ON ADOPTION

1. Agencies involved in the care of orphaned children and the administration of adoptions should strive to become more developmentally and trauma informed. Administration, staff, and consulting professionals should be exposed to the fundamental principles of neurodevelopment, attachment, and traumatology that influence the children and adoptive families they serve.

2. Adopting families should be given educational and psychoeducational materials that help outline the basic principles of neurodevelopment, attachment, and the stress response. Supportive consultation services should be provided to ensure a more positive transition and the opportunity to identify the child’s strengths and vulnerabilities to allow for proactive, rather than reactive, planning for educational, emotional, behavioral, and social needs.

3. Physicians and other professionals often involved in the care of intercountry and transracial adoptions must familiarize themselves with the various and complex challenges these children and youth face. Among the key areas of focus should be awareness and, ideally a mastery, of the emerging concepts related to trauma- and attachment-related problems often seen in this population.

CONCLUSION: WHAT CAN CAREGIVERS AND PROFESSIONALS DO TO HELP?

One of the most important things we can do is give families hope; ultimately, 90 percent of adoptive parents of institutionalized children are pleased with their decision to adopt and would consider adopting again (Pearlmutter, Ryan, & Johnson, 2008). The vast majority of these children will make significant developmental progress when provided with attention, enrichment, nurturing, and developmentally informed early intervention services. Improvement in cognitive capabilities is seen in foster care and following adoption (Nelson et al., 2011). Many intercountry adoptees receive early intervention services; this may account for the observation that internationally adopted children may not be at greater risk of developmental adversity than domestically adopted children (Juffer & van Ijzendoorn, 2005). The Bucharest Early Intervention Project was designed to understand how effectively early cognitive deficits can be remediated (Zeanah et al., 2003) and followed 200 children from birth. Some remained in institutions and others were placed into a foster care system that was created by intervention developers. The average age of placement in foster care was 21 months. The study also employed a control group of children raised with biological parents. Results indicated that foster care led to increased intelligence and scores on developmental screeners compared with the children who remained institutionalized. Both groups, however, performed more poorly than children raised with biological parents. Results also showed that results were best for children who were removed at earlier ages. Similarly promising outcomes have been found in other studies (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2008; Vanderwert et al., 2010).

Adoption has also led to improvements in cognitive functioning (van IJzendoorn, Juffer, & Poelhuis, 2005) compared with nonadopted biological siblings. Findings have suggested that adopted children’s cognitive abilities may “catch up” to environmentally matched peers following adoption. Yet, regardless of increases in intelligence and performance superior to nonadopted siblings, institutionalized children consistently performed less well in school than environmentally matched peers and had an increased prevalence of learning disorders. In short, special education services remain indicated for institutionalized children many years postadoption, despite postadoptive gains in cognitive functioning. Additionally, gains in intelligence can occur irrespective of gains in social, emotional, and behavioral domains—and difficulties in these domains can mask cognitive gains. What is perhaps most difficult for caregivers is to understand why their child functions well in one domain and poorly in another, or well in one context in a certain domain and not in another. This patchwork of developmental strengths and weaknesses can be confusing and frustrating, especially when emotional age does not match the child’s cognitive or developmental age (Perry, 2009).

Finally, a fundamental ingredient of all successful development is a sense of safety. For the child from a transracial or intercountry adoption, this sense of safety can be elusive. The potential trauma-related factors discussed earlier certainly can make this difficult; however, even without significant trauma-related issues, a sense of being different—in some ways, an outsider—often remains.

This sense of difference can be powerful and painful for the child. Children growing up in transracial households may feel constant pressure to acculturate and adopt cultural norms that are not their own. Helping the child learn about their country and culture of origin is important, as is allowing and encouraging peer and mentor relationships with other children who share similar racial, cultural, or ethnic backgrounds as the adopted child (e.g., Ortega & Faller, 2011). Simply being in a parenting or in the caregiving position confers power, and self-reflection and cultural humility is important to create a climate of acceptance and respect that can help a child feel fully embraced (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). Family members who are equally interested in learning about, respecting, and, in some cases, adopting their child’s cultural norms and traditions—even if the child is still learning those norms and traditions—could decrease stress on the entire family system. This can occur if family members are motivated to “instill the practice of adopting the client’s values as their norms” (Fong, 2001, p. 5) in an effort to create a safe and inclusive environment that promotes the child’s healthy development.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Discuss the role that early life relational disruptions may play in shaping the nature and severity of emotional and behavioral problems in the postadoption period. How is it that even brief periods of disruption in early life can continue to have such powerful impact later in life?

2. Describe the concept of “state dependence” and give examples of how a sensitized stress-response system can interfere with development even in safe, stable, and nurturing environment.

3. Describe the concept of the “intimacy barrier.” Elaborate on why this is an important concept when trying to understand and work with many intercountry and transracial adoptees.

REFERENCES

Anda, R. F., Felitti, R. F., Walker, J., Whitfield, C., Bremner, D. J., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., Giles, W. G. (2006). The enduring effects of childhood abuse and related experiences: a convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology, European Archives of Psychiatric and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186.

Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2008). Earlier is better: A meta-analysis of 70 years of intervention improving cognitive development in institutionalized children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73(3), 279–293.

Bickart, K. C., Wright, C. I., Dautoff, R. J., Dickerson, B. C., & Barrett, L. F. (2011). Amygdala volume and social network size in humans. Nature Neuroscience, 14, 163–164.

Bruce, J., Fisher, P. A., Pears, K. C., & Levine, S. (2009). Morning cortisol levels in preschool-aged foster children: Differential effects of maltreatment type. Developmental Psychobiology, 51, 14–23.

Chiao, J. Y., Harada, T., Komeda, H., Li, Z., Mano, Y., Saito, D. N., Parrish, T. B., Sadato, N., Iidaka, T. (2010). Dynamic cultural influences on neural representations of the self. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(1), 1–11.

Chiao, J. Y., Iidaka, T., Gordon, H. L., Nogawa, J., Bar, M., Aminoff, E., Sadato, N., & Ambady, N. (2008). Cultural specificity in amygdala response to fear faces. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20(12), 2167–2174.

Chugani, H. T., Behen, M. E., Muzik, O., Juhasz, C., Nagy, F., & Chugani, D. C. (2001). Local brain functional activity following early deprivation: A study of post institutionalized Romanian orphans. Neuroimage, 14, 1290–1301.

De Bellis, M. (2005). The psychobiology of neglect. Child Maltreatment, 10(2), 150–172. doi:10.1177/1077559505275116

Dennis, W. (1973). Children of the creche. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Docan-Morgan, S. (2011). “They don’t know what it’s like to be in my shoes”: Topic avoidance about race in transracially adoptive families. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 58, 336–355. doi:10.1177/0265407510382177

Dunham, Y., Chen, E., & Banaji, M. (2013). Two signatures of implicit intergroup attitudes: developmental invariance and early enculturation. Psychological Science, 24(6), 860–868 doi:10.1177/0956797612463081

Eluvanthingal, T. J., Chugani, H. T., Behen, M. E., Juhász, C., Muzik, O., Maqbool, M., & Makki, M. (2006). Abnormal brain connectivity in children after early severe socioemotional deprivation: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Pediatrics, 117, 2093–2100.

Fong, R. (2001). Culturally competent social work practice: Past and present. In Fong, R. & Furuto, S. (Eds.), Culturally competent practice: Skills, interventions, and evaluations (pp. 1–9). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Groark, C. J., McCall, R. B., & Fish, L. (2011). Characteristics of environments, caregivers, and children in three Central American orphanages. Infant Mental Health Journal, 32(2), 232–250.

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. New York: Doubleday.

Holland, J. (2011). Unlikely friendships: 47 remarkable stories from the animal kingdom. New York: Workman Publishing.

Johnson, D. E. (2002). Adoption and the effect on children’s development. Early Human Development, 68, 39–54.

Johnson, D. E., & Gunnar, M. (2011). Growth Failure in Institutionalized Children, Monographs of the Society for Reserach in Child Development, 76 (4), 92–126.

Juffer, F., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2005). Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees. JAMA, 293, 2501–2515.

Kennedy, D. P., Gläscher, J., Tyszka, J. M., & Adolphs, R. (2009). Personal space regulation by the human amygdala. Natural Neuroscience, 12, 1226–1227. doi:10.1038/nn.2381

Lee, R. M. (2003). The transracial adoption paradox: History, research, and counseling implications of cultural socialization. Counseling Psychology, 31(6), 711–744. doi:10.1177/0011000003258087

Loman, M. M., Wilk, K. L., Frenn, K. A., Pollak, S. D., & Gunnar, M. R. (2009). Post institutionalized children’s development: Growth, cognitive, and language outcomes. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(5), 426–434. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181b1fd08

MacLean, K. (2003). The impact of institutionalization on child development. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 853–884.

Mason, P., & Narad, C. (2005). International adoption: A health and developmental perspective. Seminars in Speech and Language, 26(1), 1–9.

Mehta, M. A., Golembo, N. I., Nosarti, C., Colvert, E., Mota, A., Williams, S. C. R., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2009). Amygdala, hippocampal and corpus callosum size following severe early institutional deprivation: The English and Romanian Adoptees Study Pilot. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 50, 943–951.

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., Houts, R., Poulton, R., Roberts, B. W., Ross, S., Sears, M. R., Thomson, W. M., & Caspi, A. (2010). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth and public safety. PNAS Early Edition. Retrieved from www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1010076108

Money, J. (1994). The Kaspar Hauser syndrome of “psychosocial dwarfism”: Deficient statural, intellectual, and social growth induced by child abuse. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books.

Nelson, C. A., Bos, K., Gunnar, M. R., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. (2011). The neurobiological toll of early human deprivation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 76(4), 127–146.

O’Connor, C., Rutter, M., & English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. (2000). Attachment disorder behavior following early severe deprivation: extension and longitudinal follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 703–712.

Ortega, R. M., & Faller, K. C. (2011). Training child welfare workers from an intersectional cultural humility perspective: A paradigm shift. Child Welfare, 90(5), 27–49.

Pearlmutter, S., Ryan, S. D., Johnson, L. B., & Groza, V. (2008). Romanian adoptees and pre-adoptive care: A strengths perspective. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 25, 139–156.

Perry, B. D. (2002). Childhood experience and the expression of genetic potential: What childhood neglect tells us about nature and nurture. Brain and Mind, 3, 79–100.

Perry, B. D. (2008). Child maltreatment: the role of abuse and neglect in developmental psychopathology. In T. P. Beauchaine and S. P. Hinshaw (Eds.), Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology (pp. 93–128). New York: Wiley.

Perry, B. D. (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical application of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14, 240–255.

Perry, B. D., Pollard, R. A., Blakley, T. L., Baker, W. L., & Vigilante, D. (1995). Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaptation, and “use-dependent” development of the brain: How “states” become “traits.” Infant Mental Health Journal, 16, 271–291.

Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., & Farrington, D. P. (2010). On the malleability of self-control: Theoretical and policy implications regarding a general theory of crime. Justice Quarterly, 27(6), 803–834.

Rutter, M., Andersen-Wood, L., Beckett, C., Bredenkamp, D., Castle, J., Grootheus, C., Keppner, J., Keaveny, L., Lord, C., O’Connor, T. G., & English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. (1999). Quasi-autistic patterns following severe early global privation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 537–549.

Rutter, M., & English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. (1998). Developmental catch-up, and deficit, following adoption after severe global early privation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39, 465–476.

Spitz, R. A. (1945). Hospitalism: An inquiry into the genesis of psychiatric conditions in early childhood. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 1, 53–74.

Spitz, R. A. (1946). Hospitalism: A follow-up report on investigation described in Volume I, 1945. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 2, 113–117.

Szalavitz, M., & Perry, B. D. (2010). Born for love: Why empathy is essential and endangered. New York: HarperCollins.

Tervalon, M., & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Heath Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125.

Tronick, E., & Perry, B. D. (2015). The multiple levels of meaning making and the first principles of changing meanings in development and therapy. In Marlock, G. & Weiss, H., with Young, C. & Soth, M. (Eds.), Handbook of somatic psychotherapy. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 345–355.

van IJzendoorn, M. H., Juffer, F., & Poelhuis, C. W. (2005). Adoption and cognitive development: A meta-analytic comparison of adopted and nonadopted children’s IQ and school performance. Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), 301–316.

Vanderwert, R. E., Marshall, P. J., Nelson, C. A., Zeanah, C. H., & Fox, N. A. (2010). Timing of intervention affects brain electrical activity in children exposed to severe psychosocial neglect. PloS ONE, 5(7), 1–5.

Wormith, J. S. (1984). Personal space of incarcerated offenders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 815–827.

Zeanah, C. H., Nelson, C. A., Fox, N. A., Smyke, A. T., Marshall, P., Parker, S. W., & Koga, S. (2003). Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: The Bucharest early intervention project. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 885–907.