CHAPTER 10

Use, Misuse, and Mismanagement

Our frequent use of wildlands for recreation is testament to the important and exhilarating sense of freedom we experience in them. But inappropriate behavior by humans, both intentional and inadvertent, is all too common in urban and suburban wildlands. Off-trail bicycle use, horses, and vehicles as well as trampling damage habitat and disturb the soil.

Our parks are also damaged by antiquated management practices. Despite current knowledge about environmental effects, the bulk of landscape management practices still consist of actions largely destructive to native landscapes — extensive mowing, application of herbicides and pesticides, poor erosion and sedimentation control — as well as a narrow horticultural perspective on plants. The most common management mistakes are made over and over again and have resulted in direct damage to natural areas as well as degradation to adjacent sites.

Off-Trail Use

Decline of the landscape following off-trail use is a familiar scenario. It begins with damage to herbaceous and small woody vegetation. Some plants are killed when stepped upon; others die from compaction and erosion around their root systems. New plants may not even be able to germinate because the remnant forest exists on steep, easily eroded terrain or in poor, compacted soils.

Before we can address the restoration of plant life, we must ensure that the ground is not subjected to continuing disturbance. Control of off-trail damage from trampling and wheeled vehicles often offers the greatest immediate improvement to the health of woodlands, but it is not always easy to accomplish.

For many people, simply being able to leave the beaten path is at the heart of their sense of contact with nature. It seems so harmless, and we all do it, from the birdwatcher to the dog walker, but the impacts are severe and often underestimated. A survey of the ground-surface condition in Central Park conducted in 1982 revealed that more than one-quarter of the nonturf areas were bare ground, nearly all of it caused by trampling or bicycles. More than two and a half miles of new mountain-bike trails were opened up in the northern wooded section of Central Park in a single season alone.

The rapidly growing use of mountain bikes (Figure 10.1) has created an accelerating problem for managers of natural areas. The Bicycle Institute of America reports that sales of mountain bikes have increased in the United States from 200,000 in 1983 to more than 11 million in 1989, and the figure is still rising. Land managers walk a narrow line between the need to preserve the land and the need to enhance the public’s enjoyment of it.

Trails blazed by cyclists often run up and down slopes, so their erosion is not surprising. Additional controversy over multiple trail uses is stirred up by the difference in user speeds. Mountain bicyclists can go quite fast down hills and often startle walkers and equestrians, much to their annoyance and mutual endangerment. Since the widths of new paths may be narrow (some are only 12 inches wide), passing is a constant problem. User conflicts may be serious.

The National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management have declared that mountain bikes are “a mechanical form of transport,” and as such, like motorized vehicles, are banned from use in designated wilderness areas under the Wilderness Act. Cross-country-bike use is permitted on some nonwilderness trails. Enforcement, however, is difficult, since bikers are not easily pursued except by another off-trail vehicle, which, in turn, also damages vegetation. Walkers often complain that enforcement personnel do not take off-trail infractions seriously

While a ban on mountain bicycles and off-road vehicles in wilderness areas has given some protection over thousands of acres, there is still a great deal of controversy when it comes to urban parks of limited area near dense populations, where damage is rampant and increasing. Off-trail use of bicycles, motorcycles, and all terrain vehicles often goes unaddressed in urban wildlands simply because control is difficult.

One of the most crucial and difficult decisions may simply be determining where mountain bikes and other vehicles can be used appropriately and where they should not be allowed. All users feel they have a place in a park system, whether or not they are aware of the damage they cause. At the very least, sustaining natural landscapes will require that the use of wheeled vehicles be managed to prevent avoidable degradation of the environment. Interestingly, recent studies show that bicycle tires do not cause any more erosion than walkers; so the greater issue is to get all users to cooperate by keeping to the paths and conforming to trail rules, and for taxpayers and local governments to commit to adequate maintenance. We need to establish and follow performance standards to determine when and where use should be discontinued or modified.

Figure 10.1. Mountain bikes often cut steep trails that concentrate runoff and damage the ground surface. (Photo by Clare Billett)

All too often, not providing enough amenities to users leads to off-trail use. Even where the trail system is adequate, users, both pedestrians and riders, may create new, unofficial “desire-line” trails. These “outlaw,” or “rogue,” paths may be hard to distinguish from an official path that is in disrepair, so expecting the visitor not to use it is unreasonable. Elsewhere, trampling is due to poor design and poor trail maintenance rather than usage. In all these cases, damage is inevitable because the trail system does not meet the users’ needs, even for desirable activities. To keep delicate relic landscapes out of harm’s way, the restorationist must carefully evaluate and justify each footstep, and plan trails to take visitors where they want to go.

Landscape Mismanagement

When we see park maintenance people at work or when we tend the wilder fringes of our yards, we like to think we are doing something good for the landscape, but often we are not. Chances are the work commenced with clearing out the landscape — removing briars, poison ivy, and common herbaceous species such as pokeweed. The problem is that the twigs and natural debris that build the soil disappeared along with the trash, as well as desirable plants of value to wildlife. Soil itself may have been raked to remove objectionable bits from the surface, taking more of what little dirt remained. One of the most destructive but common practices, acquired from horticulture, is overly simplistic ground-plane management.

Much of this misuse and management is attitudinal, rooted in our failure to recognize that landscapes are living systems with their own patterns and organizational principles. Forests are composed of complex interrelationships that take time to develop. They are not static objects to be manipulated at will. Nor will restoration bring about an instant transformation. It took time to mess up the landscape, and it will take time to restore it. A living system is not like a garden or a capital project; you can’t do it all at once — it will require ongoing, sustained effort.

Conventional management tends to focus on isolated tasks such as litter removal or lawn mowing. As long as these activities are completed on schedule, maintenance is considered done, sometimes regardless of the level of continuing degradation of resources, both natural and cultural.

We have institutionalized bad landscape management habits that are costly and damaging, such as deferred maintenance. Landscapes under public management, such as edges of roadsides and rights-of-way, are bushwhacked until they support invasives almost exclusively. Site impacts that degrade adjacent natural habitats, such as erosion, are still routinely ignored. Because management is usually started too late, instead of when problems first become evident, too much ground is lost. Our efforts should go toward sustaining what we still have now, rather than trying to re-create it later. A habitat should not become degraded before we turn our attention to it.

As land managers, we have often failed to confront the most difficult problems, the ones that drive changes occurring in the landscape. We have allowed the details to divert us from the big issues. The landscape has been degraded and maintenance has been deferred to the degree that we now fail to uphold reasonable standards. Most construction standards, for example, mandate only a temporary cover of quick-germinating grass to meet regulatory requirements where there may formerly have been forest. A corollary problem is the use of standardized specifications for a wide range of environmental conditions. Our failure to customize our techniques and approach to each region produces unnecessary damage to native communities and preempts opportunities to work with, rather than against, natural processes. This is as much a problem in professional practice as it is in construction and maintenance.

Overuse of Heavy Equipment

There is also an unfortunate pro-equipment bias in our culture. A good example is the general myth that the use of heavy equipment always saves time and money. It’s true that it can take manual workers days to move dirt that a bulldozer can move in hours. But it is also true that equipment use has many other, greater costs, not all of which are acknowledged, including the debt payment on the equipment, maintenance, mobilization expenses, and higher labor costs.

More rarely recognized, the use of heavy equipment results in added costs for access roads and from the direct damage done by vehicles. The larger the equipment, the more likely that a larger-than-necessary area will be affected, which, in turn, creates the need to manage a far larger area than would otherwise have been undertaken. This is one of the reasons there are ever fewer leftover places in the landscape. Both the landscape and our budgets are victim to our heavy equipment mentality.

Costs in health and safety, like the costs of deferred maintenance, are usually overlooked as well. A host of environmental changes, from soil compaction to air pollution, are intimately associated with our tendency to motorize, electrify, and oversize most tasks that were once accomplished with manual labor. A gasoline-powered mower spews out the same load of some air pollutants as thirty average cars for every hour of operation. Southern California’s Air Quality Board has called for replacing nearly 2 million pieces of gasoline-powered lawn and garden equipment in Los Angeles. Lawnmowers alone account for 25,000 serious injuries and seventy-five deaths yearly; one in five victims is a child.

Our management of all landscapes, from turf to woodlands, tends to be quite consistent: we too frequently apply the same principles no matter what the situation. Let’s take a look at some of our conventional landscape management practices and compare them to the perspective of sustainable restoration.

Woodlands and Forests

Often, conventional recommendations made in the past by foresters and horticulturists were inappropriate for natural forest and woodland areas. Take the use of exotics, which they routinely recommended for wildlife enhancement. Such concepts as “create more edge” or “thin the canopy to stimulate regeneration” have little relevance today in fragmented woodlands. Even though some individual trees may be a century old or more in urban woodlands, the prevalence of invasives and native species characteristic of early stages of forest regrowth, as well as the absence of old-growth species, attest to the relative youth of these landscapes. However, these woodlands also may be rightly termed senescent when there is a canopy of older trees and no reproduction of canopy replacement species because of suppression by vines, exotics, trampling, or any number of other chronic disturbances.

The directive to thin canopy to stimulate understory regeneration is almost always inappropriate in remnant woodlands because it tends to favor the wrong species. Woodlands in the megalopolis are fragmented and disturbed, often with a discontinuous canopy. Many older woodlands are increasingly losing canopy and are subject to blowdowns, in part because of increased storm intensity and frequency resulting from higher global temperatures, and in part because of damage from chronic disturbance. Successional species such as black cherry, black locust, and mulberry, as well as even more problematic invasives such as Norway maple, are favored by thinning — not the more desirable mast species of oak, hickory, and beech.

In the early part of this century it was fashionable to thin remnant woodlands to “beautify” them. Middlesex Fells in Boston, cleared of understory to “open it up” around 1920, showed a dramatic loss of many once-common native species in a recent recensus. The impacts of thinning practices in Prospect, Central, and countless other parks in the fifties and sixties to increase visibility and perceived safety are still felt today.

A forest consists primarily of long-lived plants whose reproductive sites develop aboveground. These plants are not “rejuvenated” by cutting, as turf is. The actual damage may go unobserved because something usually regrows. It is the shift from native wildflowers to more vines and exotics that often goes unnoticed. But every time the forest is cut, it is further simplified.

A corollary problem is the too-tidy forest that has not necessarily been brush-hogged but where too much of the understory has been weeded away. With it wildlife shelter and food vanish, as well as the next generation of forest plants. Overvigorous removal of exotics has the same result. The moral of the story is: Do not clear more than will be replaced naturally by adjacent native vegetation or what you are able to replant and tend.

We must remember that the ground is the cradle of the landscape, the place of regeneration. We must make every effort to avoid unnecessary soil disturbance, such as grubbing (digging out roots of undesired plants) and rototilling. These methods may be appropriate for renovating a horticultural bed planting but are not suited to woodlands. If the surface is presently stable, even if it is supporting only exotic invasives, beneath the soil will be roots of numerous different plants, often originating a great distance away. Tree roots, for example, are completely opportunistic, seeking any favorable ground, and easily extend 30 or more feet beyond the farthest reach of their branches.

Grubbing and rototilling also disrupt fragile microorganisms and may damage fungi associated with plants, mycorrhizae, on which good forest growth depends. Such disturbance can also stimulate many root sprouts of certain trees that can strongly alter the character of a site.

Lawns and Meadows

The greatest mismanagement of lawns is simply that they are used far too extensively. More land in the United States is maintained as turf than is managed under wilderness designation. Overlarge turf areas are damaging to adjacent environments and preempt other landscape types, including indigenous communities. All remnant natural landscapes would benefit if we could drop our attachment to lawn.

Turf is, in fact, so widespread that much of it is simply undermaintained, especially in areas where turf may have been inappropriate or difficult to maintain in the first place (Figure 10.2). Unfortunately, where turf is well maintained, the off-site impacts — high levels of pesticides and water usage, air pollution — are often even more severe. Well-watered and fertilized lawns grow faster and require more mowing. “Cost-saving” techniques such as close mowing, often 1 1/2 inches or less, like that employed on a golf course — have grown in popularity, but, unfortunately, the grass soon suffers from desiccation and may need more fertilizer and irrigation. Cropping too closely also results in early dormancy of desirable cool-season grasses and early appearance of crabgrass and other turf weeds, which then are likely treated with pesticides. When modern mowers cut very close, they frequently scrape the ground where the terrain is uneven, resulting in a skinned soil surface with only patches of remaining vegetation.

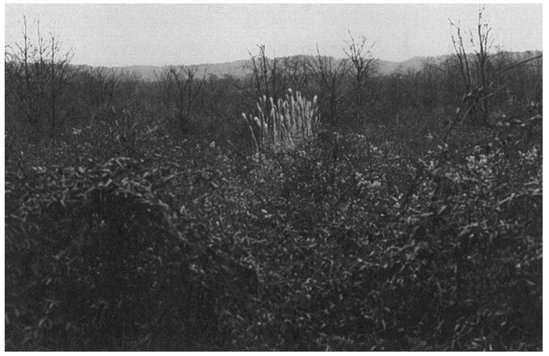

Even when we relinquish lawn, the resulting released landscapes often bear little resemblance to the waving grasslands and wildflower meadows of the past. Thinking that a meadow means no management at all is a common fallacy. In a climate that supports forest, a meadow is by definition a managed landscape. In a disturbed landscape, an unmaintained meadow overwhelmed with heaping Japanese honeysuckle (Figure 10.3) or Japanese knotweed serves as a continuous source of infestation to other natural areas and will not help in changing public perceptions of the messiness of “natural” landscapes.

Figure 10.2. Many lawn areas are riddled with bare places and poorly maintained, poor quality turf, especially under trees.

Figure 10.3. Honeysuckle, miscanthus, and other weedy exotics have completely taken over this abandoned farmland in a protected preserve.

In the end, most mismanagement is based on misinformation and, in particular, a failing to see long-term trends. Sustainable landscape management is a holistic approach that seeks to complement and work with natural systems. It is primarily centered on places rather than tasks. This larger ecosystem focus informs site-specific management and provides a context for evaluating the success of management. It is time that we confront the wide-ranging consequences of conventional landscape maintenance. It is time to give up myths about the natural landscape that have dominated horticulture, landscape architecture, and forestry. We must turn to newly acquired skills to restore ecosystems.