CHAPTER 17

Soil as a Living System

What most struck the woodland manager of Central Park on a visit to the Adirondacks was a forest floor so soft he could plunge his hand into it. The ground was visibly alive and completely different from the dead concretized soil of the urban forest in Central Park. Soil wears its problems on the surface. Where trampling or high rates of decomposition prevail, the litter layer and topsoil are entirely absent. Until recently, the annual leaf fall in the woodlands of Central Park typically did not accumulate or even persist from one year to the next. With no litter layer, there was no nursery for the next generation of the forest.

Nearly a decade of woodland management is rebuilding the ground layer in Central Park’s woodlands at the north end of the park. The site is becoming increasingly stabilized as erosion is controlled and bare areas are replanted. The many small saplings and seedlings that were planted or that volunteered after exotics removal help to hold the ground. During the icebound 1993–94 winter season, some remains of autumn’s leaves persisted under the blanket of ice until spring. That was a turning point for the woodlands. The following winter was unusually mild, and by spring 1995 there was a relatively continuous litter layer.

In time, the organic litter on the forest floor will create humus, an organic soil horizon. Within it, most of the life of soil occurs. As organic matter is continually broken down into humus, it becomes incorporated into the mineral layers of the ground surface to build topsoil.

Soils are forming all the time, and like vegetation, integrate and express all of the ecosystem’s processes. Soil is a reflection of climate, parent material, topography, vegetation, and time. The layers of soil tell a more recent history than the rocks beneath.

The soil’s abiotic, or nonliving, factors are generally the primary focus of conventional soil assessment. Much of our thinking in the past was oriented toward an “ideal” soil model that balanced sand, silt, clay, pore space, moisture, minerals, and organic matter. These standards determined whether a native soil was judged poor or good, and where soils did not conform to the ideal, soil amendments were used to modify texture, acidity, fertility, or other characteristics. Many early mitigation, stabilization, and restoration projects suffered from this agricultural/horticultural approach. Standard soil specifications, for example, call for routine topsoil stripping, fertilizing, and liming even though many disturbed or made soils are already less acid than in their native condition because of the repeated addition of lime by means of concrete rubble and urban dust. Most regulations related to development sites, highways, landfills, and abandoned mines require from 3 to 6 inches of topsoil spread over new soil surfaces before revegetating. That topsoil comes from somewhere, so the restoration of one site frequently means the destruction of another. We need more research on alternatives to topsoil, especially those that reuse waste materials appropriately to amend local soils and that avoid environmentally costly products such as fertilizers and peat. Even where topsoil has been stockpiled on a site before construction, the living organisms it contains die within days.

The Soil Food Web

A food web is the structure of relations among the organisms within an ecosystem based on what each consumes. Primary producers consume water, minerals, carbon dioxide, and a few other things to produce organic matter, which is consumed by most of the rest of the creatures that are, in turn, consumed by still others. Some organisms have very specialized food requirements while others feed quite omnivorously.

Both soil and water are media in which plants and animals live and grow. And in a very real way, both are living systems. One of the most important contributions to the history of water management occurred with a shift in perspective that originated with Ruth Patrick and others. When one views water as a living system, its quality is measured by the richness of its biota, instead of physical and chemical factors such as flood levels or biological oxygen demand. Its biological components are a defining measure of health that reflect a more complex array of factors. This same kind of revolution is happening in our perception of soils.

In 1968 Ruth Patrick wrote about aquatic food webs:

The various pathways in the food web and the various types of interrelationships of species to each other are two of the most promising avenues of research.

Most food webs are composed of at least four stages [;] . . . the stages tend to be few because so much energy is lost between stages. . . . Since the stages of the food web are few, . . . diversity is expressed by many species forming each stage or level in the food web.

This strategy of many species at each trophic level has developed a food web of many pathways which seems to give stability to the system . . . [W]e see there are many food webs within systematic groups as well as between groups. It should also be pointed out that the size and the rate of reproduction vary considerably in each of the major systematic groups. These types of variability in food chain, size of organisms, and reproductive rates help to ensure the maintenance of the various systematic groups, and in turn preserve the trophic stages of the food web of the whole community (1968, 37).

Soil ecosystems are strikingly similar. Like aquatic systems, they have a great deal of redundancy. Very simple systems with simple food webs can be drastically altered by the appearance or disappearance of one or a few species. In more complex systems there may be multiple ways in which energy flows through the food web. Thus the more complex systems are said to have redundancy and are not so dramatically changed when a few species change. Many soil components even lie dormant until favorable conditions occur. The full soil structure is not required for most basic soil functions.

Rather than focusing simply on the nonliving aspects of soil, restoration should enhance its living components, primarily bacteria, fungi, and microfauna. Most of the work of forming humus is done by plant roots and by animal life in the soil, which depend on a permeable soil crust, stratified soil layers, and appropriate amounts of organic matter. There are up to 3,000 arthropods per cubic inch of productive soil. A litter layer of leaves 1 1/2 inches thick and a yard square might contain 5,000 miles of fungal filaments.

Plants are the primary producers of organic matter in the forest soil system. Ants and other invertebrates initiate the breakdown of ground-layer litter. Soil microorganisms including fungi, bacteria, protozoa, and actinomycetes continue this process of converting organic matter into soil minerals that in turn become available as nutrients to plants. In food-web nomenclature, these organisms are “consumers.” Primary consumers (herbivores) feed directly on the “producers,” which are the plants; secondary and tertiary consumers are predators and parasites, which feed upon each other as well as upon herbivores. Food webs also contain other decomposers and detritivores that feed on litter, such as mites, woodlice, and earthworms. Woodlands typically support more diverse assemblages of soil organisms than grasslands. If soil organisms are included in the species count, temperate rain forests are richer in biodiversity than tropical rain forests.

The soil food web performs the primary function of the soil, which is to cycle energy and nutrients, including nitrogen, sulfur, and phosphorus. Native soil systems are very efficient and succeed in recycling, for example, upwards of 80 percent of the nitrogen in the system. The cycling of nitrogen is intimately associated with the cycling of carbon, which is tied up largely in organic matter. Nitrogen, in part, determines the rate at which carbon is broken down. Bacteria and fungi take up the nitrogen as they decompose soil organic matter, and some fix atmospheric nitrogen. This nitrogen too is released into the soil to be again available to plants. Nitrogen’s slow release from an organic to an inorganic form, which is available to plants, is called “mineralization.”

The microbial community performs three major functions: as discussed above, conversion of organic nitrogen to a plant-available form such as ammonia; nitrification when ammonia is converted to nitrates; and denitrification when nitrogen is recycled into the atmosphere as a gas. The soil microbial community also contributes to soil stability, another vital function. Fungal hyphae knit bits of organic matter together to create a denser, stronger litter layer and upper soil horizon.

Not all soil food webs are the same. Fungi appear to dominate in forest soils, bacteria in agriculture soils. Thus, soil communities change over time as the landscape succeeds to forest. The nature of the vegetation determines the nature of the fuel/food available for soil organisms. Grasslands litter, a relatively easily decomposed herbaceous material, does not typically contribute all of the soil’s organic matter. The extensive root systems of grasslands are also a major source of the soil’s organic matter. The roots of grasses exude carbon directly into the soil as sugar, amino acids, and other forms to feed soil fungal associates and activate bacteria and other microbes.

As the landscape matures, the litter becomes more difficult to break down. While herbaceous litter is primarily cellulose, the litter of the forest becomes increasingly higher in lignin, the woody component of plants. Tree leaves have more lignin than grasses, and the leaves of late successional species, like beech and oak, typically have more lignin than ash, tulip poplar, and other early successional species. In woodlands an important shift occurs as leaf fall and other litter become the most important sources of organic matter, rather than the direct contribution of carbon by the roots as in the grasslands. There are also larger volumes of wood on the ground in the form of fallen twigs and limbs, which directly foster fungi because bacteria are unable to decompose lignin. The mycorrhizal filaments from tree roots reach up into the old wood to extract the valuable nutrients. Insects such as beetles and ants are also able to break down wood. Wood in contact with the soil and standing dead trunks, “snags,” create many opportunities for various wood and soil invertebrates of the forest.

The soil communities continue to change along with the vegetation communities. Over time, the cycling becomes less rapid. In a humus-rich forest soil, the organic matter that remains the longest is rather stable organic compounds that degrade much more slowly. By then the humus is important more as a site for important chemical processes and for the physical qualities it gives the soil than as a stockpile of nutrients. The humus, for instance, increases the water holding capacity of the soil.

Another important role of dead wood is to serve as a water reservoir for the forest in times of drought. Dead wood, especially larger logs approaching a foot or more in diameter, soaks up water like a sponge and retains it for long periods. Old logs or stumps make great nursery sites by carrying vulnerable seedlings through dry spells. Salamander populations also depend on large logs for needed moisture, which is, in part, why they are absent so long after clearcuts and timbering, although they may number one or two per square yard in old-growth forests. Logs increase local stormwater retention as well by inhibiting overland flow and by absorbing water in place.

Fungi in general foster acid soil conditions, whereas bacteria can increase alkalinity. The bacteria and their predators in grasslands help maintain the soil’s pH and the form in which nitrogen is made available, as well as nutrient cycling rates that work to the advantage of grasses. Where fungi are more abundant, as in natural forests, the nitrogen is converted to ammonium, which is strongly retained in the soil system. In bacteria-dominated systems, the bacteria convert nitrogen to nitrate instead of ammonium. Nitrate leaches more easily from soils than ammonium; however, the growing patterns of grasses tolerate this condition. But when woodland soils become bacteria dominated, rapid leaching may leave most native old-growth species poorly nourished while invasive exotics and some early successional natives are flush with nutrients. Some species are more sensitive than others to soil nutrition. Conifers do not grow in bacteria-dominated soils whereas agricultural crops cannot be grown in fungi-dominated soils. Indeed, in woodlands, a high ratio of bacteria to total biomass is an indicator of disturbance (McDonnell, Pickett, and Pouyat 1993). These factors, which seem to be dependent upon soil organisms, play a greater role in succession than previously recognized (Ingham 1995).

Damaged Soil Systems

Soils are far more damaged and damageable than we realize, but the problem is often hidden. The cumulative effects on forest systems and other environments, of acid rain, nitrogen deposition, global warming, ozone thinning, unnecessary grading, and stormwater changes have left a legacy of severely altered soil conditions and totally modified soil food webs. The consequences and remedies are still largely unknown.

Many of these changes are so pervasive that we take them for granted. Take earthworms, many nonnative, which now are abundant throughout the urban forest system. In fact, they are not part of the historic community of living creatures in native forests and are typically associated with more disturbed landscapes. Earthworms in general increase soil fertility by initiating the breakdown of organic matter, aerating and mixing the upper soil, and creating a microenvironment that stimulates the bacteria that convert ammonium to nitrate. High earthworm populations also foster nitrification by supplying the oxygen necessary to convert ammonium to nitrates. They take a system already disturbed by added nitrogen and push it farther from normal by consuming the litter layer five times as rapidly as fungi and converting excess food into nitrate. The same kind of self-reinforcing cycle can be seen when aquatic systems fill with algae (Nixon 1995). Each shift in the soil character will in turn ripple through the entire system. Unfortunately, in many woodlands that look mature because they have larger trees, there is a lag in the succession of the soil, which may still be dominated by earthworms and bacteria and impoverished in terms of types of fungi, invertebrates, and other, more efficient paths for nutrient cycling.

Building Soil Systems

The objective in restoration is to restore the nutrient cycling and energy flow of the historic soil system. First, work to protect existing soil resources and then explore techniques to increase the overall biomass of the soil and to foster the diversity of native soil flora and fauna.

Recommendations

• Identify, protect, and monitor areas of native soil that are relatively undisturbed.

Most areas contain places where there is less-disturbed soil that can serve as rough models of local soil conditions. Studying the more natural soils at the same time remediation is being documented in a disturbed landscape will provide a standard for measuring the success of different approaches. The natural sites also serve as propagation sources for locally adapted microorganisms.

• Reduce local sources of soil contamination, including added nitrogen.

Evaluate local air pollution impacts, especially that of automobile exhaust. Removing roads wherever possible is of paramount importance, especially in more natural areas. What is convenient, even to the restorer, such as easy access, may be lethal to the most jeopardized species. Educate the community about regional air pollution impacts. Many other management practices, such as pesticide use, also affect the realm of the soil. The most popular herbicide, for example, glyphosate, which is often used to control exotics, enhances conditions for bacteria but makes a poor substrate for the development of forest fungi.

• Recognize that the user is inseparable from the solution.

No treatment of soil will make it impervious to compaction, erosion, and other such disturbances. Confine all use in forests and other natural landscape fragments to designated trails to minimize degradation from feet, hooves, and wheels. Prohibition alone never is enough. Users will stay on trails to the extent that trails create the elements of satisfaction that keep them there and provide access to desired destinations. The gradual building of the litter layer and the absence of bare soil off the trail are hallmarks of success.

• Minimize “working the soil.”

Despite a lot of knowledge about the damage done to living systems by constant perturbation, there is still a tendency to overwork soil. Beyond the familiar structural damage, such as that caused by working a heavy soil while it is wet or the erosion that accompanies any soil disturbance, the soil’s level of microorganisms is also severely affected. For example, plowing and any mechanical disturbance to the soil will tend to foster the rapid growth of bacteria, which in turn generate exopolysaccharides, which cause the soil to slump in rain. Other substances make soil hard to wet, or hydrophobic. Cultivating soil is almost always deleterious to natural areas and constantly resets the time clock back to disturbance rather than allowing more complex, stable, and diverse soil systems to develop. We need to try new techniques, such as planting new seedlings in logs or stumps, to avoid soil disturbance while enhancing survival. Another technique is vertical staking, wooden twigs driven vertically into the soil. Vertical staking serves to aerate and loosen the soil without damaging the roots of existing vegetation, and it avoids the need to completely turn the soil. In addition, it favors the development of fungi instead of bacteria because it incorporates wood into the soil.

• Reevaluate the usefulness of current methods of stockpiling topsoil.

Harris, Birch, and Short (1993) describe the progressive impacts of stockpiling, which is a frequently used method to retain a site’s topsoil during construction. The first phase is an instantaneous kill of many of the living creatures in the soil that occurs with the initial removal and stockpiling. During the next few months there is a flush of bacterial growth as well as fungi but only in the upper soil on the outside of the pile, the new “topsoil.” During the next half year or so the soil stratifies in layers. The primary distinctions reflect the amount of oxygen in the soil because of its depth in the pile or level of saturation with water. The developing layers consist of both near-surface aerobic and deeper anaerobic zones as well as a shifting transition area between them. When the soils are restripped and replaced elsewhere, there is another instantaneous kill of most living organisms followed by a flush of bacterial growth.

• Experiment with alternative strategies that better preserve native soil food webs when moving soil is necessary.

Experiment with methods that keep soil horizons intact, such as moving blocks of soil. Practitioners are using and modifying equipment like old sod forks and front-end loaders as well as developing new equipment, such as John Monro’s soil mat lifter, described in Part III, for this purpose.

• Reevaluate the addition of organic matter to enrich disturbed soils.

The continuous rain of airborne nutrients onto soils in the form of acid rain and nitrogen deposition from air pollution raises serious concerns about many traditional management practices with regard to the use of organic matter as a soil additive and our almost automatic addition of nutrients to disturbed soils. Researchers have shown repeatedly that fertilizer benefits weed species. Creating less-hospitable conditions in the conventional sense can actually enhance the performance of native species. Using elemental sulfur on test plots, Jean Marie Hartman at Rutgers University and her co-workers (1992) lowered the pH and reduced nutrient availability in a mixed meadow to foster native species over exotics. Many invasives, both native and exotic, are nitrophiles and do poorly under such conditions.

• Reevaluate the use of mulch and soil amendments that are harvested from landscape communities other than those native to the site.

Because to a great extent soil organisms are what they eat, bringing in organic material from other sources will not necessarily foster the growth of the same soil organisms as are in the desired native community. In an artificial soil such as made land or a highly contaminated soil, it’s not the addition of organic matter but what kind we use that will impact the nature of plant succession on the site. The more indigenous the existing landscape, the more important it is to minimize the use of dissimilar materials.

• Reevaluate the conventional management of brush, dead wood, and leaves. Even where no additional fertilizer is added, it is important to modify our management of dead wood and vegetative debris to more closely mimic natural conditions. This sounds obvious, but how often is organic matter collected from a site, taken to another location to be composted, and then used at still another location when it is “well rotted”? Under more natural forest conditions, however, the major contribution of organic matter is not well-rotted compost but rather wood, twigs, and leaves that slowly break down in the place where they fall. Adding wood and raw, rather than composted, leaves more closely mimics the natural scenario.

• Develop new ways of observing and monitoring soil health.

Unfortunately, standard soil tests are of limited assistance to the restorationist. For example, nitrogen levels are poorly evaluated when they are measured only as concentrations at any one time rather than as total flux over time. Conventional tests also ignore the biotic component altogether. A number of researchers are working on new methods. One, Jim Harris, of the University of East London in England, who has been monitoring soil changes associated with restoration, has developed a set of techniques for measuring the size, composition, and activity of a soil’s microbial community. These measurements can be used for comparison with a less-disturbed target community to assess the level of recovery of the soil system. He and other researchers have developed methods that, at least in England, have increased fungal populations with significant beneficial impacts to soil development and nutrient cycling.

• Build populations of soil fungi.

As noted earlier, heavy nitrogen enrichment from air pollution and increased compaction, erosion, and sedimentation have tended to favor the growth of bacteria over fungi and invertebrates. Thoughtful management promoting the development of fungi, through appropriate treatment of the soil, soil surface, and litter layer, can help restore indigenous food webs in forest soils.

Management to Foster Fungi and Other Forest Organisms

Because only fungi can break down lignin, the woody component of plant matter, allowing dead wood and woody debris to remain on the ground layer is a major component of the effort to rebuild soil fungi. Raw woodchips and small limbs on the soil surface provide an ideal matrix for the rapid development of a dense fungal network in the soil that, unlike bacterial decomposers, also provides surface stabilization. The webby, sticky quality of the mycelia of fungi serve to knit the surface particles and litter to reduce erosion and conserve moisture that is vital to the life of forest soil. While a deep layer of woodchips can create a growth-suppressing mulch that later floods the area with nutrients, a very thin layer of woodchips stimulates the development of more complex soil biota while limiting the overall rate of the addition of nutrients. Wood’s slow rate of decomposition is also important where rates of decomposition have accelerated dramatically. Because lignin has a very low decomposition rate, it is a more durable ground cover that promotes the development of a stable litter layer.

Occasionally it may be necessary to inoculate the soil or vegetation with mycorrhizal fungi, although in most cases local sources of inoculum are likely to be available from wind and animal dispersal. Where soils are high in nutrients it may be more important to manage nutrients and foster fungi than directly inoculate, especially if inoculation is not required to establish plant species. Small amounts of soil from analogous sites nearby or woodchips colonized by local mycorrhizae may be used to inoculate sites where natural processes have not been effectual, where there is a substrate limitation, such as thin soil over bedrock, or where plant-specific requirements do not occur.

Jim Harris recommends using thin blankets of fresh woodchips from 1/2 to 1 inch thick, which create ideal surface conditions for the development of fungi. Within weeks, a network of fungi colonizes the surface so densely that the woodchip layer can actually be shaken loose from the soil by hand and moved elsewhere to inoculate an area nearby with local fungi. This method, local harvesting and dispersal of indigenous fungi, should become an important part of soil management programs and is preferable to using a mass-produced commercial inoculum for restoration purposes.

We can also manage blowdowns better than by simply removing fallen trees, as is the current convention. Instead, we can minimize the hazard of a falling tree to area walkers while mimicking more natural processes of decomposition that encourage the growth of fungi and invertebrates in the soil by partially upending the stump. The upended root mass reveals a near-perfect seedbed for native species and maintains enough of the tree’s still living roots to maximize the extent to which its nutrients are passed directly to neighboring trees.

Commercially produced mycorrhizae have been very successful in reforesting drastically disturbed lands, such as mine spoils, all over the globe. Sites in Kentucky, for instance, where soils were extremely acid, with pH values as low as 2.8, have produced pulpwood for harvest in just fifteen years from inoculated seedlings (Cordell, Marx, and Caldwell 1991). When considering such products, however, evaluate their potential impact on native subspecies of mycorrhizae. Like commercial plant propagation, this approach risks the hastening of extinctions of local varieties. We still need to develop appropriate procedures and protocols for disseminating fungi and other soil organisms as much as we do for larger plants and animals. Such techniques are well developed in the western states but have only recently been applied in the East.

Fire also acts as a stimulus to many wood fungi and invertebrates and reduces bacteria, which in turn fosters the growth of fungi. In a study of changes in beetle populations following fire in boreal coniferous forests in Finland, scientists found a sudden appearance of a diverse group of beetles that feed on wood fungi (Muono and Rutanen 1994), which in turn implies an even more rapid response by fungi. These wood-fungi-feeding forest beetles are fire specialists and represent an important evolutionary adaptation at an ecosystem level to recurrent fires of the past and are a side-benefit of restoring natural patterns of fire to the forest.

Native soil conditions and biotic communities and processes need to be the models for our interventions in restoring native habitats. The remaining remnants of native soil are, therefore, bioreserves for the richness that once characterized our soil heritage. The approach should be to restore, rather than replace, soils. Soil made in place is favored over the imported topsoil. Instead of reintroducing missing components with inputs from outside the environment, we should instead focus on fostering the restoration of remnant and indigenous communities of soil biota, which furthers the general goal of “restoring-in-place” to the extent feasible. By doing so, we also minimize the casual dispersal of local subspecies of soil microorganisms and exotic soil organisms. In the worst-case scenarios, such as areas where soil is completely depleted, some materials from outside will be needed, but even in these situations the soil-building resources inherent to the site should be used to the maximum extent possible.

Soil Protection and Restoration During Construction

Construction for utility lines, roads, and rights-of-way are frequent intrusions into parks and natural areas. Typical pipeline construction, utilizing a 75-foot-to-100-foot wide construction zone and equipment that sometimes weighs more than 20 tons, causes serious soil compaction, damaging the roots of trees adjacent to the right-of-way and destroying the soil as a living medium and reservoir of forest reproduction. In Morristown, New Jersey, when the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission mandated that the Algonquin Gas Transmission Company route a new 36-inch natural gas pipeline through a mature oak-beech forest in the Loantaka Brook Reservation, the Morris County Park Commission negotiated for an opportunity to develop alternative strategies.

In protecting this site, the commission’s primary goal was to preserve the forest as an intact ecosystem. Protection measures focused on maintaining a continuous tree canopy overhead to minimize forest fragmentation and on preserving soil biota and structure. Working closely, Andropogon, the contractor Napp-Greco, and Algonquin, the pipeline engineers, devised and implemented the following strategies:

• Realign the route.

Realigning the proposed route to follow existing park trails and other existing seams of disturbance reduced forest clearance and the extent of soil disturbance.

• Minimize disturbance to the adjacent habitat.

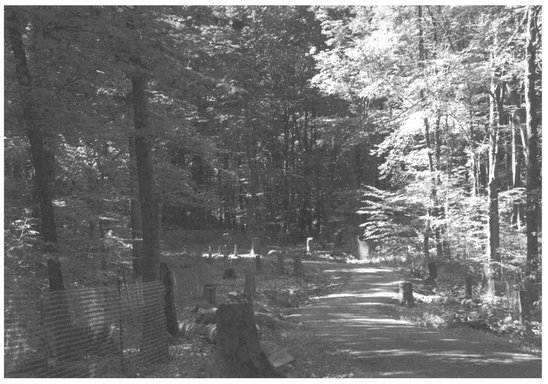

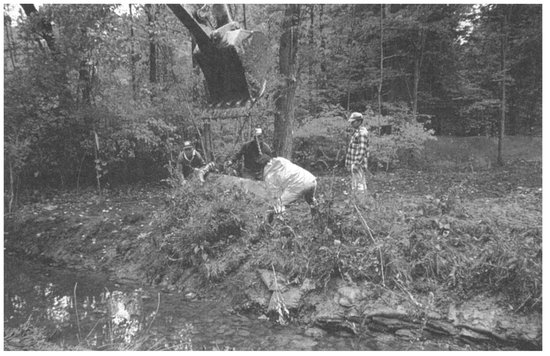

Construction did not begin until the construction zone was fenced along the entire route through the park. Qualified arborists felled the trees, which were lowered with ropes into the construction zone, to prevent damage to the adjacent forest. Wherever possible, they left the tree stumps in the soil (Figure 17.1).

• Reduce the width of the construction zone from 75 to 35 feet.

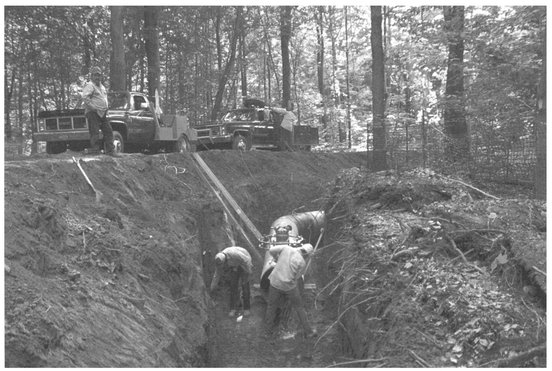

Working with heavy equipment on top of the linear pile of soil that was excavated from the trench eliminated that portion of the corridor needed for separate soil stockpiling. This method also reduced soil compaction and reduced most damage by serving as a cushion for heavy equipment. Welding the pipe in the trench instead of alongside it also limited the area of disturbance (Figure 17.2).

Figure 17.1. The pipeline right-of-way was fenced and cleared before any work to limit damage to adjacent woodlands took place.

Figure 17.2. Welding the pipe in the trench rather than alongside it further reduced soil damage.

• Retain the soil structure intact to the extent feasible.

The restoration goal was to reestablish the rich forest ground layer, which required that the soil structure and its reservoir of life remain intact. Regulatory agencies in charge of soil protection mandate only minimal restoration, concentrating primarily on separating topsoil from subsoil and stabilizing the bare ground with turf grasses after the soil is replaced.

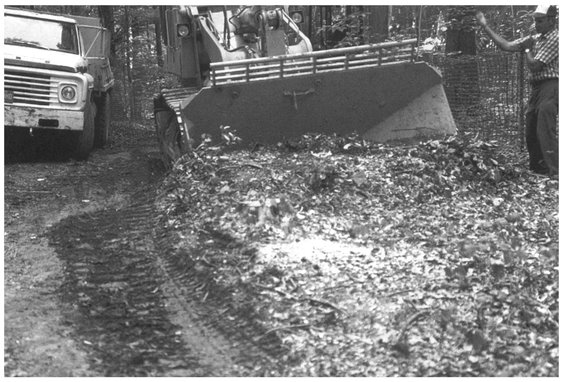

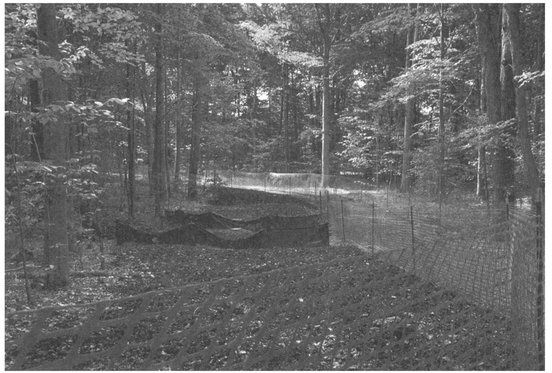

Andropogon’s alternative restoration proposal was to harvest the upper soil layers in blocks, before digging the trench, to preserve the existing stratification of the soil and to ensure the continuity of soil microorganisms, woody rootstocks, bulbs, corms, and seeds. Napp-Greco, the contractor, developed a specially adapted front-end loader blade to remove the soil blocks from the forest floor over the pipeline trench (Figure 17.3). These were stored alongside the open trench for a few days and then replaced over the backfilled trench. Upon completion of each day’s run of pipe, workers narrowed the fencing to just the path width to protect the newly transplanted blocks of soil. The spaces between the reinstalled mats were mulched with leaves from the local Shade Tree Commission (Figure 17.4).

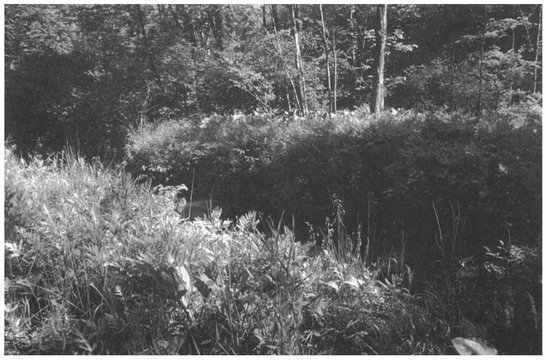

After construction, the impact on the forest floor was limited. Canopy cover was largely intact and a thick regrowth of ferns, wildflowers, shrubs, and small trees resprouted on the forest floor (Figure 17.5). The contractors used the same technique along the disturbed stream corridors, except that a rich herbaceous ground layer was harvested and rescued from a site where a parking lot was under construction. These soil blocks were stockpiled on wooden skids and then staked in place along the steep stream banks by diagonally split lengths of two-by-fours (Figure 17.6). Regrowth was dense and lush and has resisted invasion by weedy species (Figure 17.7).

Figure 17.3. The modified bucket of this front-end loader lifted large blocks of soil intact, which were stockpiled beside the trench for a day or two before they were replaced.

Figure 17.4. After each section was completed, a narrower fenced area allowed for access but protected the replaced woodland sods.

Figure 17.5. One season later, the ground layer rebounded. New trees were also planted.

Figure 17.6. Wetland sods, rescued from a construction site and transported on skids, replaced the degraded vegetation along a disturbed stream corridor with a more historic plant community.

Figure 17.7. Lush growth a season later has resisted exotic invasion well.