CHAPTER 18

Plants for Restoration

The restoration of native plants in disturbed forest ecosystems challenges all our knowledge and ingenuity. Locally and regionally we are losing species at accelerating rates. We can no longer assume that plant communities will recover on their own, nor that we will be able to transplant wildlings effectively. In many past rescue efforts, most transplants typically survived only a few years before disappearing from their new locations. Present commercial propagation includes only a small percentage of native species in any given area in the East.

Because restoration of native plant communities is still a developing field of knowledge, every restoration project is really a living laboratory. Every project presents learning experiences in how to propagate local ranges of species, knowledge necessary if we hope to return these plants to, and sustain them in, the wild. It also presents opportunities to develop landscape designs and management practices that are bioregional in focus and more sustainable over time.

Where you cannot restore conditions for effective natural reproduction of indigenous species, you will need to become an active agent of recruitment, assisting the reproduction and growth of plants in new areas. Protected landscapes and other biological reserves may ultimately be vital as sources of seeds and other propagules that can potentially be introduced into new ranges as well as for the creatures that depend on and support vegetation. Germ plasm and seed banks are an important component, but it is even more vital to sustain plants (and animals) on the ground, by fostering their recruitment, reintroducing them when needed, and controlling invasives.

Our knowledge of native plants is riddled with large gaps and pervasive misperceptions. For example, one widely held misperception is that native species are less suited to many modern landscape conditions than exotics. This is simply not true. Natives are, by definition, very well adapted to the local climate and terrain. The real problem is that severe disturbance reduces the landscape potential to a very few species whether they are invasive exotics or aggressive natives. While the full breadth of native communities is not sustainable in the urban environment, many native species thrive there and can be used to create rich and compelling landscapes if appropriately managed. It is also important to note that while exotic food sources are used by wildlife, they do not appear necessary to their survival. Native plant communities, on the other hand, are vital to indigenous animals.

No ready-to-use, comprehensive national inventory of ecological resources is currently available, although organizations such as the National Institute for the Environment, the National Biological Survey Act, and the National Ecological Inventory have been initiated to gather this information. The Nature Conservancy, in a public-private partnership with state fish and wildlife agencies and scientists, has been documenting species to develop the Natural Heritage Network, an ongoing record of the status of potentially endangered plants and animals. A Natural Diversity Index is being compiled for each state. This effort released a 1997 Species Report Card: The State of U.S. Plants and Animals. To obtain information about indigenous local species, contact your state chapter of The Nature Conservancy and other environmental agencies and organizations, as well as botany departments at universities and native plant groups, and keep the lines of communication open with them. As your project progresses, your discoveries and learning will provide new information that you can share with researchers and organizations, adding to the “terrestrial ark” that we need to save the richness of our forests.

Working with the System

Enormous problems face any plant restoration effort, whether it is at a governmental or individual level. Soil conservation, fish, wildlife, and forest services at the federal and state levels are already involved in plant propagation, distribution, and planting programs and determine much of what is planted through recommendations incorporated into the regulatory process. For example, the lists of species currently recommended by the Natural Resources Conservation Service for erosion and sedimentation control serve to define what type of seed is widely available in the nursery trade. Unfortunately, these lists also tend to stifle the use of native plants, in part because plant specifications developed for state departments of transportation are typically used as the standard conventions for the vast bulk of construction projects. Therefore, these species dominate the inventories of nurseries and discourage the introduction of natives. In New Jersey and Pennsylvania, for instance, only one of the thirty or so plants recommended is native. When confronted with this fact, the agencies’ response is often that these are the species that the nurseries have. Such circular arguments guarantee that native species will not be introduced into the trade and thus our landscapes.

One important problem is that some of the plants most commonly used as quick stabilizers are not only invasive, but they also retard the return of native plant communities. Although tall fescues — including the popular variety “K-31,” are very invasive, they are among the most widely recommended, used, and researched grasses. Included in almost every specification for lawns and roadsides, they are difficult to eradicate from the landscapes they invade and have strong allelopathic effects on other species, especially trees and shrubs. Fescue toxicity is estimated to cost livestock producers up to $200 million annually (Burchick 1993). Ironically, at present, some native milkweeds are listed as agricultural weeds despite the fact that they are vital native host plants to the monarch butterfly.

Anyone wishing to use native species often must spend considerable time and effort justifying any deviation from accepted conventions, and obviously it would be difficult to totally revise the lists overnight, but their emphasis could be shifted gradually to phase in native plants. Even a small experimental plot can demonstrate that native plants are generally more practical, easier to maintain, and more stable for use in landscaping than introduced species.

One of the most important initiatives at this time may be the Federal Native Plant Conservation Committee, which was established in 1994 in a memorandum of understanding. The memorandum was signed by seven governmental agencies — the U.S. Forest Service, Soil Conservation Service, Agricultural Research Service, Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and National Biological Survey — as well as five nongovernmental organizations — The Nature Conservancy, Center for Plant Conservation, National Association of Conservation Districts, Soil and Water Conservation Society, and Society for Ecological Restoration. Their eventual recommendations could be instrumental in addressing the growing crisis of biological pollution. On April 26, 1994, President Bill Clinton also signed a memorandum, motivated by the Report of the National Performance led by Vice President Al Gore, that directs the federal government and federally funded projects to use “regionally native plants for landscaping” and “construction practices that minimize adverse effects on natural habitat.” The government recognizes the cost-effectiveness of such an approach and directs the Department of Agriculture “to conduct research on the suitability, propagation, and use of native plants for landscaping.” Demonstration projects will encourage reduced use of fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation and increased energy efficiency.

The possibilities for existing institutions and agencies to play a positive role in the preservation of native plant communities are almost limitless and require only a shift in program and product emphasis. The state of Illinois has demonstrated real leadership in this area. As in most other states, the Illinois state-run nursery program once grew a wide array of fast-growing, easy-to-propagate, invasive exotics. In fact, after twenty years of producing autumn olive, the nursery was producing 20 percent of the total state output, or more than 1 million seedlings a year by 1982. But all that changed in 1983, when the Seedling Needs Committee, representing the divisions of Wildlife Resources, Forestry, Public Lands, Planning, and Natural Heritage, and area nurserymen, decided that producing exotics was not necessary if suitable native substitute species could be found. The committee shifted its emphasis to native species.

Today, the state nursery is now propagating fifty-two species of native woody plants as well as prairie grasses and wildflowers that are started from seed collected in state parks and conservation areas by biologists, foresters, volunteers, and maintenance personnel. Several dozen species are made available each year and no exotic species are subsidized. Public education has been an important part of this effort and has included very accessible materials such as a one-page flyer on controlling the invasive garlic mustard. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources also shares seed with the state’s Department of Transportation. This department has advised commercial growers of the growing demand for regional native seed because of their new planting policy, which calls for planting native communities beyond the mowline along state roads.

Other states are recognizing the benefits of going native. The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation in cooperation with the Virginia Native Plant Society has held conferences on invasive plants and developed informative flyers such as the “Invasive Plant Species of Virginia.” The Wisconsin Departments of Natural Resources and Transportation are preparing to grow native seed on three prison farm sites. The Minnesota legislature defeated — but may reconsider — an innovative program to develop native seed as an alternative agricultural crop and also allows for repayment of start-up loans with native seed supplied to state agencies. The Natural Resources Group of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation has developed a native species planting guide for New York City and vicinity that is organized by plant community types suited to different environmental conditions and is intended, in part, to stimulate a native-based nursery industry.

Wild-Collected Plants

In addition to all the other challenges to their survival, popular native species face the serious problem of being overcollected in the wild. Unfortunately, at this time it is difficult for the consumer to avoid wild-collected plants because of the lack of regulation at the state or federal level. In many cases, a collected plant simply has to be held in a nursery for a single season to be labeled as “nursery-grown.” Look instead for a “nursery-propagated” label.

In an attempt to prevent the overcollection of wild plants, nine organizations formed a coalition in 1991 to petition the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to amend its Guides to the Nursery Industry to eliminate confusion and possible deception about the original source of plant material; make the guidelines conform with standards applied to international trade laws and the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES); and eliminate the unfair competitive advantage enjoyed by nurseries that sell relatively cheap wild-collected plants instead of more expensive propagated ones.

At this writing, the FTC had yet to respond to the petition, which was signed by the Natural Resources Defense Council, California Native Plant Society, Environmental Defense Fund, Garden Club of America, Mt. Cuba Center for the Study of Piedmont Flora, National Audubon Society, Native Plant Society of Oregon, New England Wildflower Society, TRAF-FIC (USA), Native Gardens (Greenback, Tennessee), Niche Gardens Nursery (Chapel Hill, North Carolina), Montrose Nursery (Hillsboro, North Carolina), and the American Association of Nurserymen. In the meantime, the Mail-Order Association of Nurserymen adopted a labeling code of ethics, but it is voluntary and not legally enforceable.

Some progress is also being made at the local level. Rhode Island, for example, has a “Christmas Greens” Law, which protects evergreens commonly used as winter decoration. The Virginia Native Plant Society, in conjunction with local officials, has developed a comprehensive program directed toward the protection of ground pines.

Extraordinary Efforts, Positive Results

The challenges of restoration will require all the skills of the horticulturist and the botanist. Once-common species close to the edge of extinction, such as the American chestnut, deserve special efforts, not unlike those directed toward rare and endangered animals. There are encouraging signs that progress is possible. The American Chestnut Foundation is among several groups endeavoring to breed disease-resistant strains suitable for reintroduction into natural forests. Another fruitful line of investigation is the use of the so-called hypovirulent strains that are nonlethal strains of the blight organism that do not injure the trees but prevent more virulent strains from infecting them. And most recently, the firm of Hoffman LaRoche has announced some progress in developing disease-resistant American chestnuts via genetic engineering. The restoration of this once-predominant canopy tree of much of the eastern forest with its phenomenal utility to wildlife may happen in the foreseeable future.

The survival of a few species is undermined by our lack of knowledge about their reproductive processes, which in turn restricts our ability to reintroduce them to a site. For many plants the form of the juvenile is strikingly different from the adult and may have different pH, nutrient, and moisture requirements. In many cases the juvenile forms have never even been seen or at least have not been recognized. The seedling may not only look different, but it also often germinates under different conditions than it requires to grow as an adult.

To cite one example, until Jean Marie Hartman, an ecologist and landscape architect at Rutgers University, began to study swamp pink, the juveniles had almost never been seen in the wild. More important, in trying to propagate this plant, she and her students realized that seedling mortality for transplants was nearly 100 percent until they reached a certain size, at which time they could be planted successfully in the environments favored by either juveniles or adults (personal communication). This kind of information is vital for conservative species, especially before field plantings are undertaken with valuable plants.

The real work of restoration is to learn from mistakes while keeping the goal in sight. This all takes time, but remember that time is relative. Many of us, horticulturists and foresters included, are often quick to abandon a native plant under stress and substitute an exotic species. For example, the current vogue to replace plantings of flowering dogwood with Korean dogwood, the host of the anthracnose disease that infects native dogwood populations, only serves to further jeopardize the native species. There is a similar rush to find hemlock species from Asia that are adapted to the hemlock wooly adelgid as substitutes for the native hemlock.

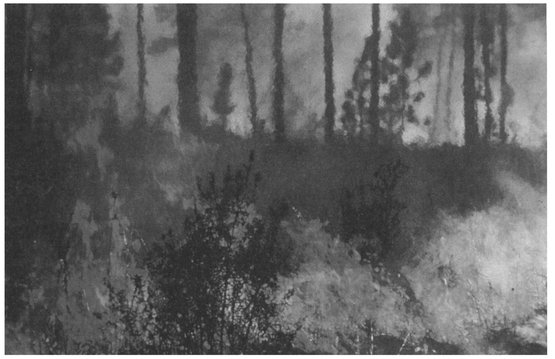

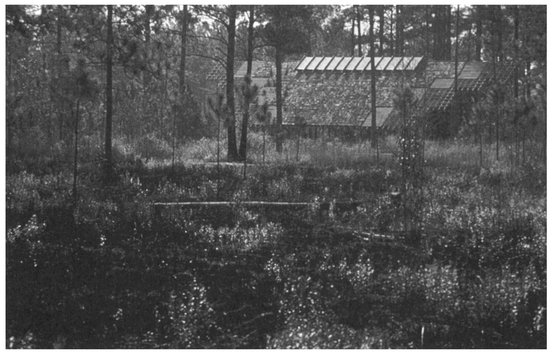

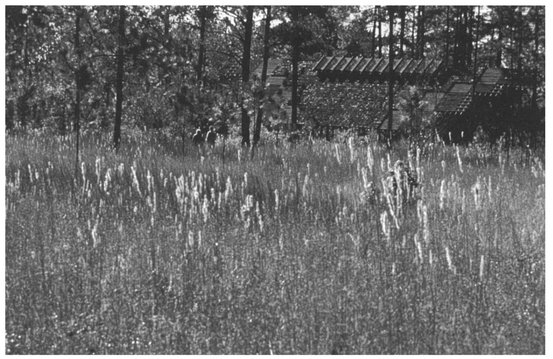

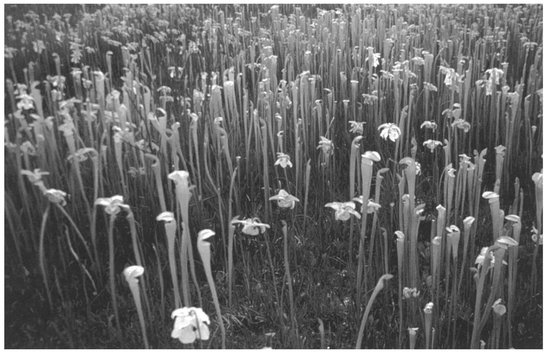

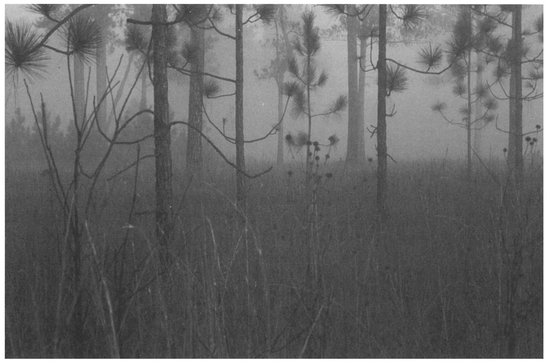

The Crosby Arboretum in Picayune, Mississippi, which is dedicated to the plants of the Pearl River Basin, exemplifies the concept of a bioregional arboretum. At the very outset the arboretum’s board looked beyond the boundaries of their site to seek to preserve the biodiversity of the region by acquiring crucial natural areas and joining in shared conservation agreements to protect others. At the same time, the arboretum is restoring natural habitats on the Pinecote Visitor’s Center site on land that was previously both logged and farmed. Using innovative technologies such as prescribed burning (Figures 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5), the arboretum is pioneering the management of southeastern coastal plain landscapes in a gardenesque setting. This applied research as well as the growing collection of indigenous plants that is fully documented and monitored will be invaluable in the effort to restore local ecosystems and to develop a regionally appropriate landscape vocabulary. The ultimate goal is to re-create conditions where natural recruitment processes are reestablished.

The Role of Nurseries

For many people, nurseries are a primary source of information about plants and play an important role in local landscape selections. Some nurseries are already making an effort to behave more responsibly when it comes to growing and promoting plants. An article about purple loosestrife in the April 1994 issue of Network News, the newsletter of the Eastern Native Plant Alliance, illustrates one East Coast nursery’s growing awareness of its role in sustaining natural systems:

White Flower Farm [Litchfield, CT] will not offer purple loosestrife after this spring, the (1994) catalogue announces, because it has become a major pest along waterways throughout America, “crowding out native plants that don’t share its vigor.” To the nursery’s credit, the statement adds, “Because marshy areas in the Northeast have been filled with Lythrum for as long as we can remember, we were slower than we should have been in taking the problem to heart.”

Changes over the last several years in the catalogue’s description of purple loosestrife provided a glimpse of the way this nursery’s decision evolved. Throughout the late 1980s “good for naturalizing” was given as one of loosestrife’s merits, though in 1989 the catalogue noted that seedlings had never been found near stock plants.

For several years the description said, “Yes, there are wetlands in the Northeast where Lythrum is a common weed and some will stick their nose in the air at it for this reason.” In the Fall 1990 catalogue that statement was replaced by, “Yes, there are wetlands in the Northeast where Lythrum salicaria is a common weed and it should not be encouraged by further planting.” By 1992 the suggestion of defensiveness was gone, and the listing emphasized that the plants offered were not L. salicaria but sterile hybrids of L. virgatum, “no threat to wetlands.”

The [1993] catalogue, noting bans on the sale of Lythrums in some states, expressed the opinion that existing vast populations would “almost certainly overwhelm” local control efforts and that the circumstances “were not occasion for excluding Lythrums from all gardens.” It did warn, however, that the “self-sterile hybrids” offered “can and will interbreed with local populations if not deadheaded.” Meanwhile the number of states to which varieties offered in the catalogue could not be shipped had grown from one, Minnesota, in 1989 to six in 1993 and eight in 1994, four in the Midwest, one in the Southeast, and three on the west coast (2–3).

Figure 18.1. The managers of the Crosby Arboretum research and demonstrate prescribed burning to restore successional habitats suitable for natural areas and home landscapes alike. (Photo by Ed L. Blake Jr./The Crosby Arboretum)

Figure 18.2. The meadow around the Pinecote Visitor’s Center just after prescribed burning at the Crosby Arboretum. (Photo by Ed L. Blake Jr.lThe Crosby Arboretum)

Figure 18.3. Within weeks of the fire a rich meadow again glows in the afternoon sun. (Photo by Ed L. Blake Jr.lThe Crosby Arboretum)

Figure 18.4. This pitcher plant bog, known locally as a buttercup meadow, is sustained by periodic burning; it would otherwise succeed to forest. (Photo by Ed L. Blake Jr.lThe Crosby Arboretum)

Figure 18.5. Longleaf pine, once the predominant community, requires fire to stimulate growth of its seedlings. (Photo by Ed L. Blake Jr.lThe Crosby Arboretum)

The times are changing rapidly, as this response written by Julie Manson, Environmental Council on behalf of Smith and Hawken to a letter of complaint by the authors illustrates:

Thank you for your letter of concern regarding the Porcelain Berry.

I referred your question to our plant buyer who replied that there are areas where this plant is not invasive. Nevertheless, due to the concerns you mention we will not offer Porcelain Berry in the future, either through our stores or catalog.

Here in California we wage our own battle against invasive species such as Pampas Grass. I am reading with interest the information you sent on this topic, and will keep it for future reference.

Both consumers and nurseries play important roles in what plants get planted. In time, the growing interest in native species may drive the phase-out of problem exotic species as much as regulatory restriction.

Changing Markets

The market for native species differs from the current market in important ways. One of the most difficult problems for the landscape restorationist is obtaining locally indigenous species and subspecies for use. Unfortunately, the economics of plant production has resulted in large centralized growing facilities that serve very extensive regional markets. “Superior” native varieties, like nonnatives, are propagated vegetatively and distributed widely. These are often significantly different from local native varieties and, in places, may jeopardize indigenous species. There is no seed production nursery for native grasses and wildflowers in the East, so even when we try to plant a native meadow in New York or New Jersey, we cannot use local subspecies unless we have collected local seed. The differences are often strikingly apparent. To cite just one example, Indian grass grown from midwestern seed dwarfs its eastern counterpart. These plants may persist and/or hybridize with native subspecies and become a problem for restoration.

There are several reasons for these nursery trends that fit poorly with the needs of indigenous species. First, there is pressure to develop varieties that meet the industry’s level of predictability. Second, growers are increasingly relying on production methods that produce a salable crop the quickest — that, unlike the slower methods of reproduction, such as seed, reduce the genetic diversity of the population and increase the risk of creating a supercompetitor.

Large-scale propagation is in some cases the answer to curbing wild collection of native plants. Modern propagation efforts have already reduced the collecting of wild populations of carnivorous plants used indoors in terraria or as decorations. Many of the newer technologies, such as tissue culture, have greater application in this market where the full range of natural diversity is not required. Nonetheless, it is advisable to maintain adequate genetic diversity in cultivated populations as well. Tissue culture also offers the opportunity to expand the numbers of threatened local subspecies to better ensure their survival.

The responsibility to think ecologically is as great when one is trading in native species as it is with nonnatives. The possibility of creating mutant strains that may threaten local subspecies diversity is very real because of the kinds of practices that characterize the plant production industry today. A more ecological approach would be to foster smaller-scale, localized propagation and production in a larger context that is monitored and managed. To do so, propagation standards for both industry and institutions are needed to protect local levels of subspecies diversity and ensure responsible propagule collection, informative labeling, and appropriate distribution.

There is, fortunately, a vigorous and growing trend toward the bioregional nursery that is focused on a specific regional landscape. These nurseries often show great creativity in their marketing programs, informing the consumer about unfamiliar native plants and the role the home gardener can play in sustaining natural systems. The Pinelands Nursery in New Jersey, for instance, holds an annual daylong conference that informs local landscape architects, contractors, agency personnel, and interested individuals about native plants and techniques for their establishment.

Not only are educated consumers and industry personnel embracing the concept of biodiversity, but they also are beginning to grasp its economic benefits. Simply having well-managed habitats is becoming a valuable asset. The Native American community on Walpole Island in Michigan, which has maintained the high quality of its indigenous prairie by burning, is now collecting and supplying native seed in a program developed by the School of Natural Resources and Environment at the University of Michigan in Lansing.

But even a well-developed regional nursery system may not be adequate to meet the needs of those restorationists working on the most critical habitats. The most fruitful course of action is often to propagate locally indigenous plant material using seeds and propagules from the site itself and from the immediate locale under similar habitat conditions. Skilled collectors and propagators are needed to meet this demand, and your project may be just the place to do it.

For the innovative contractor there also is a growing market for a wide array of landscape management services related to restoration that provide less-costly and environmentally better alternatives to conventional maintenance. The same corporations that once sought lawn-mowing services for vast areas of turf are now seeking those with skills in woodland management and meadow installation. Sustainable landscape management and sustainable horticulture are in. Pesticides, peat, inorganic fertilizers, and mowers are out.

Landholders and regulatory agencies are increasingly looking toward the reestablishment of stable vegetated riparian corridors to address non-point-source pollution control and flood management that also provide multiuse greenways. New products related to these services include a wide array of soil stabilizers made entirely of organic materials, such as the fiberschine, a coconut fiber roll that is used to anchor wetland plants along shorelines. In addition to the growing market for specialized plant materials and products for soil bioengineering and other innovative techniques, there is a demand for qualified installers as well as contractors with specialized skills.

The Home Gardener

By being a thoughtful and informed consumer the home gardener plays an important role in restoration. What we do in the home landscape mirrors our actions in the community landscape and is a reflection of how we perceive our relationship to the larger natural world. It will take a great many fine and innovative gardeners to wean us away from lawn and provide attractive alternatives to current landscape conventions. Concurrently, there is a great need for public education to link the public’s preferences to a broader understanding of the environmental consequences and benefits of the choices they make.

When we are aware of what is happening in the landscapes around us, the possibilities are endless. The Florida atala butterfly, presumed to be extinct in 1965 when the last known colony was destroyed, probably owes its existence to nursery plants and homeowners. In the 1980s, when a small number of larvae of the subspecies were found, the repopulation success story was supported by a widespread community effort to plant its host species, a cycad called coontie.

There is something quite preposterous about our devotion to the landscape styles of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries at a time when we must address the future of our landscape. Beneath our lawnmowers and asphalt is an invisible forest that represents the richest and most complex landscape type that can be attained given our climate. After centuries of beating back the forest, we now find ourselves sadly winning this age-old battle. It will take equal effort to bring the forest and all of its richness back.