CHAPTER 20

The North Woods of Central Park

The ongoing restoration of the North Woods of Central Park illustrates a comprehensive approach to the challenge of establishing a more positive relationship between people and the landscape. After decades of neglect, misuse, and overuse that had left the park in shambles, the North Woods is a model for other urban wildlands.

The renewal of Central Park began in 1980 with the creation of the nonprofit Central Park Conservancy. In 1985 the conservancy published Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan. Since then, the conservancy has raised millions of dollars and coordinated with the Department of Parks and Recreation to renovate the park.

Despite successes elsewhere in the park, by 1984 all efforts to restore its more natural areas had come to a halt, stymied by controversy and disagreement over what constituted restoration. The initial efforts began as restoration of the historic vistas that were part of Frederick Law Olmsted’s design, but those who valued the site as a seminatural area feared that design-oriented management would seriously affect wildlife. When some large trees were cleared to reopen one historic vista, opponents brought the proposed work to a halt.

There were what seemed to be irreconcilable differences among the various users and caretakers, as if the disparate individuals and agencies involved could never share a similar vision of the landscape or cooperate to address management issues. Those responsible for long-term care of the site questioned the maintainability of a natural area in Central Park. Some, for example, favored the use of nonnative plants recommended by fish and wildlife agencies to attract wildlife while others saw these plants as invasive pests. Security problems also loomed large. Nor were there any successful models of a habitat restoration in an urban forest. The degradation continued unabated.

In 1988, the conservancy began working with Andropogon Associates to break the deadlock and develop a restoration and management plan for the woodlands of Central Park, including the 90-acre forest at the northern end of the park that is now known as the North Woods. Andropogon’s objective was to integrate the restoration of the landscape into the daily workings of the agencies responsible for its care and to involve the public in the project. The following account describes many of the strategies that have been integral to the growing success of this project and the steps that were taken in the process.

A Participatory Process

Because so many different people and agencies have effects on the landscape, the restoration process must provide for long-term continuity and be participatory and broadly representative if it is to be effective. The work process therefore began with a set of interviews to identify the key players and their concerns and perceptions about the landscape. The initial summary report described areas of agreement and disagreement and led to the establishment of the Woodlands Advisory Board, individuals representing the Sierra Club and Audubon Society, the Parks Council, the Institute of Ecosystem Studies, the U.S. Forest Service, and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation as well as conservancy staff and local citizens.

From the outset the board determined that all decisions would be made by consensus. If the group could not reach agreement, no action would be taken at all. There was a lot of incentive to reach consensus because if the board could not come together to address urgent issues such as security, then others, who might not value the woodlands so highly as a natural area, would eventually do something.

Since its inception, the board has met monthly. Despite some initial fears that a consensus-driven, participatory process would be too cumbersome, the board has made timely decisions and has been able to take immediate action on several fronts at once. At the same time, the board has provided a solid foundation for pursuing long-term design development that is informed by monitoring.

While many innovative city projects are brought to a sudden halt when administrations change or when the one individual who spearheaded the effort moves on, this project has already survived severe personnel and funding cuts to the parks department. The process has led to a remarkable degree of integration of the project into the workings of the parks department and the conservancy. Within a few years of the board’s creation, every member was well informed about this landscape, and multiple layers of in-house expertise had been developed in plant identification, exotics management, and path construction. A large constituency, both public and private, now participates in and supports the restoration of the North Woods.

Developmental Process

By proceeding one step at a time and then reassessing our strategies, we can be more responsive to the special and unique qualities of each place.

• The restoration plan evolves as it grows from the knowledge gained in the process of managing the site.

Because there was so little agreement about how to implement a restoration plan, the advisory board agreed to take a developmental approach in which each step depended upon the success of the previous stage. The board started with field trials and established short-term goals and criteria for success.

• Each phase of restoration opens new opportunities and reveals previously hidden aspects of the site, both positive and negative.

The advisory board made no attempt to craft a comprehensive, grand master plan. At the outset no one had enough information or knew the capacity of this landscape to recover, if natives would reproduce when exotics were controlled, or if inappropriate user activities could be modified at all. The board’s willingness to agree to remove exotics depended on whether previous removals met the goals of no increase in erosion and sedimentation or trampling. The board did not agree to a natives-only policy until it could demonstrate that an adequate array of native species would survive and persist on the site.

Prioritizing Local Damage Control

• Your first priority is to reduce the levels of ongoing damage and stress to the site.

The board knew it had to take some action immediately, before all data and planning were complete, or the deterioration of the landscape would continue. It targeted four problems that required ongoing efforts to manage:

- Off-trail biking, trampling, and vehicles. There can be no forest recovery, whether natural or managed, with constant disturbance to the soil surface. If restoration is the goal, then virtually all the millions of visitors to Central Park need to stay on paths in the woodlands. This issue cannot be addressed without involving the entire community. Those who use the landscape must take part in order for an effective solution to be developed. The issues are multifaceted and range from needed infrastructure improvements to public relations and policy enforcement.

- Poor stormwater management. Over the years, poor maintenance of the path system and drainage infrastructure as well as extensive areas of denuded soil led to spiraling levels of damage. The original Olmsted plan included a drainage system for adjacent streets that separated urban stormwater from the park’s water features. Over time, however, the outlets clogged without maintenance and stormwater overflowed road margins, severely damaging the park’s landscapes. The path drainage features designed by Olmsted also collapsed without maintenance. The proliferation of unofficial desire-line trails created by off-trail users, especially mountain-bike trails that ran straight down the slopes, further exacerbated runoff and erosion. Restoration of the infrastructure was a prerequisite to restoring the landscape.

- Proliferation of exotic plants. Norway and sycamore maples as well as Japanese knotweed were overrunning the woodlands and were among the few species reproducing successfully. Although the board initially had little confidence that native communities could be sustained in the park landscape, even with management, it agreed to suspend planting invasive exotics in the North Woods and to limit their expansion by management, which included monitored removals.

- Lack of maintenance and security. Although Central Park is relatively safe compared to the city at large, every incident occurring there is front-page news. It is as important for people to feel safe as it is to be safe. The need for adequate visibility provided incentive to remove the exotic maples and knotweed where they formed virtual tunnels over the pathways, creating a very uninviting aspect with limited views. The board was very cautious, however, because the clearing of understory undertaken in the 1960s and ‘70s to increase visibility for security reasons had lasting negative effects on native understory and ground-layer vegetation. Trash and debris also undermined perceived security in the woods, so maintenance was given high priority

Building Local Expertise

• Restoration is a local effort that requires new skills and expertise in the local community.

There is pressure on every major park system to cope with inadequate budgets and, often, a shrinking workforce, at the same time that park use in general is increasing and outdoor recreation is expanding exponentially as an industry. Hiring freezes and cutbacks take an annual toll, heavy equipment is often used instead of laborers, and the overall quality of care is diminished. In the face of these challenges, the Central Park Conservancy instituted many innovative solutions to deal with the bureaucratic and financial hurdles that characterize the management of public land. One of the most important was its commitment to building its own staff to perform the restoration work. The shift in emphasis toward restoration requires a great deal of specialized knowledge and skills by those who are responsible for the landscape but in turn offers the chance to work smarter, not harder.

A crucial step toward the actual implementation of the program was the hiring of a woodlands manager who began to document site conditions, coordinated volunteer activities, and served as an advocate and a caretaker whose first concern was the landscape. This role is crucial to the success of a restoration and may be filled by an individual or a team, but it cannot be assigned to those for whom the landscape is only a peripheral concern. Even though time and budgets are limited, the woodland manager’s priorities are very different from those of others in the park. Today, it not hard to understand why this landscape is improving when you walk through the forest with a person who knows every tree seedling personally, who will remark about which volunteered naturally or which were planted and when, and where the seed came from. The woodland manager of the North Woods, Dennis Burton, has recently written a book titled The Nature Walks of Central Park (1997) in which he describes the sometimes-surprising wildness of the park.

From the outset, it was clear that volunteers were not enough to complete a forest restoration. The park needed increased funding for maintenance and, more important, increased staffing. The conservancy pioneered the use of in-house crews in addition to outside contractors on capital projects as a way of building their organization. The restoration of the Glenspan and Huddlestone arches that bridge the stream that runs through the North Woods was the first capital project in the woodlands (Figure 20.1). The conservancy bid on and won the contract to perform the landscape management and planting, which permitted the hiring of three individuals for the eighteen-month contract period. The goal was to use that time not only to initiate extensive on-site management, but also to demonstrate how important it is to have workers in that part of the park. This approach provided flexibility and facilitated a more experimental approach to the work than would have been possible in a conventional contracting procedure. The conservancy worked closely with the Department of Parks and Recreation throughout the project. The team modified the design in the field based upon what was discovered daily in the course of the work, but each decision was guided by clear overall policy and guidelines.

The woodlands manager reviewed all the work and supervised a planting crew that today continues as the woodlands management crew for ongoing maintenance of the landscape. The woodlands crew provides a comprehensive array of physical services, from litter removal and limited stonework, to seed and plant collection, new planting, watering, and exotics control. Crew members also provide impromptu tours for visitors and participate in informal educational and public relations programs. The presence of the crew in the area also greatly enhances real and perceived security, and is reflected in the funding received from the Use and Security Task Force of the Department of Parks and Recreation to maintain the crew. The project built a high degree of in-house expertise, perhaps the greatest asset of all.

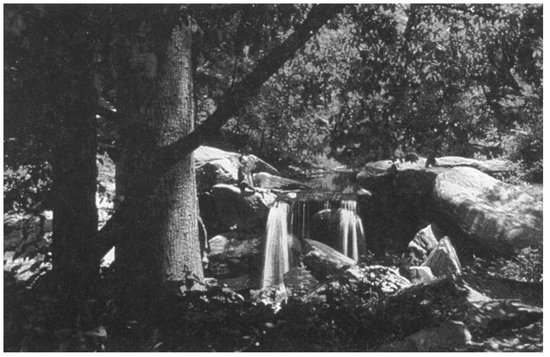

Figure 20.1. The restoration of portions of the stream called the Loch and the Glenspan and Huddlestone arches at either end of this creek provided opportunities for restoration of the surrounding woodlands. (Photo by Sara Cedar Miller/Central Park Conservancy)

Providing Appropriate Access

• Without appropriate infrastructure for access, almost any use of a site can be damaging.

Walkers and other users tend to stay on trails that are inviting and go to places of interest. If a design seeks only to restore past character and does not take current uses and environmental conditions into account, it will fail. While there was a general goal to retain Olmsted’s original path design in the North Woods, the board agreed to several modifications, including a few “adventure” trails in areas where extensive trampling had occurred. Andropogon conducted a workshop on trail construction at the site with the conservancy staff designers, the construction manager, and the construction crew. The narrow trails they designed are as natural in appearance as possible, constructed of large stepping stones, and are also expected to have lower maintenance costs over their useful life than dirt or woodchip trails. The new trail (Figure 20.2) near the Huddlestone Arch replaces over five separate outlaw trails that once coursed downslope to the stream that runs through the valley but have now been regraded and replanted. Designed to convey stormwater downslope without gullying, the trail provides access to the water’s edge. It gives the visitor a sense of leaving the main trail to explore while staying on a reinforced ground surface. New bridges and large boulders bring the walker close to the water while protecting the soil surface (Figure 20.3).

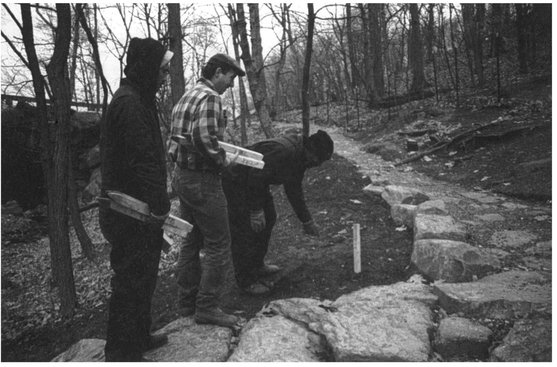

Figure 20.2. In-house staff in Central Park completed a new stone trail to replace several unofficial trails. The trail retains and recharges runoff in several infiltration pits along its length. (Photo by James Yap)

Creating Positive Uses

• The park user must play a key role in restoration if we expect to change how the public uses its parks.

Volunteer labor is a crucial component of the restoration process, not because it saves money, but because it builds positive uses and educates (Figure 20.4). In Central Park, volunteers control exotics, stabilize slopes, and gather and plant seeds of native species from elsewhere in the park; they are also a growing and well-informed constituency that advocates for the natural values of the landscape. In Central Park, what began as a restoration project now has grown to become a major focus of visitors services in the North Woods, providing them with the opportunity to learn about and participate in the woodlands restoration.

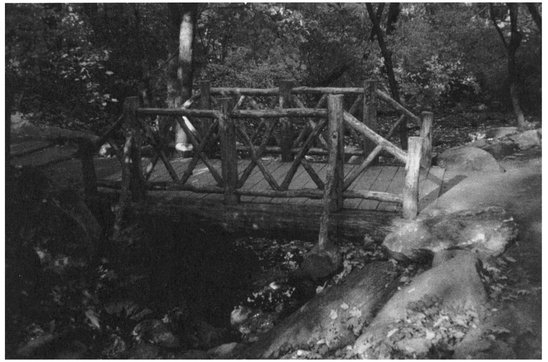

Figure 20.3. Replacing bridges and adjacent stonework protects the site while providing access for visitors. (Photo by Dennis Burton/Central Park Conservancy)

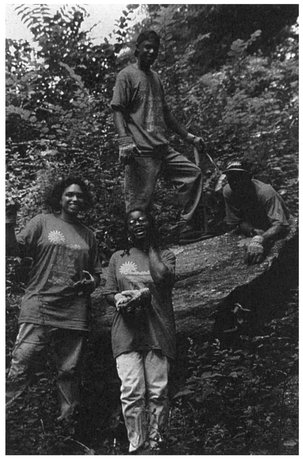

Figure 20.4. A volunteer crew under the direction of Dennis Burton, the woodlands manager of the North Woods in Central Park, spent many hours stabilizing eroded soil and removing trash and exotic invasives. (Photo by Sara Cedar Miller/Central Park Conservancy)

At the park’s interpretive facility on 110th Street, volunteers keep a wildlife log as part of the growing bio-journal of the site. Volunteers note what species they’ve sighted and where, any special conditions, their names, and the date. Two members of the advisory board developed a checklist of the birds of Central Park and a field card for the growing numbers of younger, local birdwatchers in the park. Nikon, in response to a plea in the North Woods newsletter, “Woodswatch,” generously loans binoculars to children for this effort.

At the present time, over sixty-six schools in the city are involved in North Woods programs. Students are planting trees, shrubs, and wildflowers and measuring the growth and survival of both planted and volunteer vegetation; they also are digitizing and keeping monitoring records for the Biodiversity Project, a program to monitor any deliberate gaps created by removing exotic maples and assess the management of gaps aimed at promoting natural communities.

The conservancy’s participatory approach is especially important in its effort to prevent off-trail biking. In the past, careless riders cut numerous new trails into the slopes, which then become conduits for stormwater. The public education program emphasizes the role that cyclists can play in restoring the landscape. Today, young cyclists are signing pledges not to go off-trail or ride recklessly.

The Ramble Project

The North Woods is not the only woodland in Central Park. The Ramble, another small woodland area in Central Park, was one of Olmsted’s favorite designs. A jewel-like landscape, the Ramble is a highly dramatic terrain that centers around a constructed rivulet called the Gill. Hills steepened with added fill surround this artificial stream, but by 1995 much of their surface was barren. Mountain bikers, who love the steep slopes, were responsible for high levels of damage, but many other off-trail users, ranging from casual daytime strollers to evening cruisers, were also responsible. Although the landscape had been deteriorating rapidly, it was still known as one of the hottest birding sites in the Northeast. It is strategically important to birds crossing the megalopolis and one of the best places for a stopover.

The board had agreed years before that a comprehensive approach was needed in the Ramble and decided to couple a program of public education and enforcement with a highly visible restoration project in the heart of the Ramble. This approach required substantial groundwork before any physical work projects were begun. A series of meetings with a range of groups from police to bikers publicized the ongoing restoration program and the effort to keep bikers and walkers from going off-trail in the natural areas of the park. New signage in the Ramble alerted the visitor to its status as a protected New York City ecosystem and spelled out the rules for appropriate use of the area. The next step was to restore a highly visible site as a demonstration area. The advisory board selected one of the most damaged sites in the Ramble, where the exposed roots of a few cherry and locust trees still clung to barren soil crisscrossed with ruts and trails. In 1996 the ground crew started by installing fencing that ran right across a popular shortcut and were prepared to repair it daily if necessary. Signs were placed on-site to explain the Ramble Project to the visitor.

Since then the staff has been evaluating two techniques for dealing with compacted soils on the Ramble site. The first entails reworking the entire compacted surface and protecting it with “erosion blanket,” affectionately called “trauma blanket” by park workers. Jute mesh is staked in place over a thin woodchip layer covering the bare soil, and undecomposed leaves are put on top of the jute. The second method, “vertical staking,” consists of branches driven into the ground like wooden stakes every 6 or 8 inches. Installation requires minimal surface disturbance. The branches convey water and moisture downward into the root zone and loosen the surface as they decompose.

As it turned out, the fence never needed repairing. The ground layer has rebounded beyond all expectations — which demonstrates just how much of the problem is due to disturbance and how resilient a landscape can be if stress is reduced. Sometimes an exclosure works as well with people as it does with animals.

A Monitored and Documented Process

• Documenting and evaluating the consequences of management are necessary parts of management.

In the North Woods project, the board decided that all actions at the site should enhance its biological health and diversity and that ongoing monitoring was required to assess impacts on its ecological systems. To this end, the Natural Resources Group, a division of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, completed a baseline vegetation survey of the North Woods. A map delineating all major vegetation types is updated periodically during the restoration process, and detailed field notes record site conditions and species present at the site.

The conservancy and parks department staff and volunteers have begun numerous other monitoring projects and field trials as management questions arise. They also maintain a management log and photographic records. The documentation process daily grows more integral to the ongoing care of this landscape, although there is still a long way to go before the North Woods will be considered an adequately monitored site.

Although there was no initial agreement on all implementation strategies, the board agreed to several initial principles to guide its management directions in the interim, one of which was to monitor all actions. Among the first issues to arise was the debate over native versus exotic plants. The group held many divergent opinions but agreed upon an interim strategy that new planting, at least for the time being, should be indigenous to the area and that some limited exotics removal should be undertaken and evaluated. The results of the monitoring have so far been encouraging and suggest that native species can be sustained if exotics management is undertaken. Since all landscapes in the park require some maintenance, this approach appears to be successful.

The cautious removal of exotics was the first step in the process. Norway maple, sycamore maple, and Japanese knotweed were targeted as the three most aggressive and prevalent exotics. The initial goal was to prevent the incursion of exotic invasive plants by removing exotics from the few relatively healthy remaining areas where native plants were still present and reproducing. The next objective was to remove exotics from those areas where they were just becoming established. Lastly, in degraded areas where no natives were reproducing, the goal was to simply contain the invasives and prevent their further expansion.

The Natural Resources Group established field trials, including control plots, to assess conditions resulting from the removal of exotic saplings under 4 inches in caliper. Deborah Lev, the biologist who set up these plots, remarked on the difficulty of finding any two sites in the North Woods that were sufficiently comparable to set up valid experimental plots. Like other urban woodlands, Central Park is both quite simplified yet highly variable because of its past uses.

Soon after exotics removal began and when the competition from invasives was lessened, the native species returned. Each year brings new surprises. In the first year there was a wavelet of tulip poplar seedlings, and by the second and third years, young red oaks started to appear. One year conditions favored sassafras. Red maple, white ash, sycamore, and sweetgum are also appearing on their own. The next generations of native trees are now present, not because canopy was removed to stimulate reproduction, but because the understory was opened up by the removal of the exotic saplings. Of course, the exotic maples have also found opportunities in the newly opened understory after their larger siblings were removed, and they still are the most numerous understory plants although their numbers are reduced. Management is still necessary to sustain the newly appeared native saplings, and the long-term success of the natives remains uncertain, but progress can be measured in the growing number of natives.

One of the most surprising species that is reproducing well in the North Woods is mockernut hickory, a plant rapidly disappearing from many suburban and rural woodlands. Its appearance here is probably due to the heavy and fertile seedfall of the mature specimen hickories elsewhere in the park. A more detailed and quantified study of hickory recruitment is under way and includes mortality assessments on oak and hickory seedlings.

Over time, support for the natives-only policy has grown steadily as the habitat quality has improved and the aesthetic character has been enhanced. Early fears that native communities could not reproduce the drama of the Olmsted landscape have largely evaporated. People now recognize that the North Woods is the only place in Central Park dedicated solely to native plant and animal communities.

When the board decided to tackle the large exotic maples whose seeds provide an endless and immediate source of propagules, the woodlands manager developed a detailed inventory that was intended to help prioritize removals. Because more than one-quarter of the North Woods’ canopy trees over 6 inches in trunk diameter are Norway or sycamore maple, the board needed to plan removals so that woodland conditions were sustained. The inventory included information on the size and condition of each tree and noted trees in the understory that would grow rapidly if overstory were removed.

Then one day, literally out of the blue, came the inevitable change in plans. A severe windstorm coursed through the park, bringing down over 150 trees, including two of the largest oaks in the North Woods. While the board was developing the Biodiversity Project, to monitor gaps resulting from removal of the maples, its task shifted to monitoring real gaps. The board elected to replant trees in the Red Oak Gap, as one of the study sites is named, to see if that would jump-start succession; in the Black Oak Gap, they decided to simply remove exotic maples and knotweed as they appeared. Now, each summer, youth interns measure the growth of all understory species, including both planted and volunteer vegetation. In addition, the woodlands manager and staff keep detailed records of all management to permit ongoing assessment and revision of the techniques and strategies. The information from these studies, in turn, informs the ongoing evolution of the restoration and management plan.

Enhancing Recruitment

• Center your planting strategy around enhancing natural recruitment rather than replacing it.

If we want to sustain native communities in their habitats, we must apply our propagation skills to restoration. If we make a commitment to this goal, it is possible to maintain the gene pool of each genetic neighborhood.

The changing priorities in Central Park illustrate planting strategies centered on enhancing recruitment. At the outset, the object was to plant something native that would survive and to remove seedling- and sapling-size exotic maples. As native species appeared, priorities shifted. Very early on tulip poplar was especially widespread, so the Woodlands Advisory Board decided not to plant it anymore and to concentrate on species that were not reproducing. Each season is somewhat different. Tulip poplar seemed to establish in a wet year, but a summer of drought saw numerous sassafras stems appear in the understory. Oak and hickory are so special in the park that every seedling is an event.

The same shift in priorities occurred with the ground layer. The project members first used native woodland aster, divided and plugged as well as seeded, because it worked. Now that the ground layer is better established, they are focusing on other species. As native species appear on their own or establish successfully, they are deleted from a proposed planting list consisting of native species known to have been on the site in an 1857 survey of the landscape before the park was built. While many of the tree species found in 1857 are still present in the area, most plants of the ground and shrub layers are absent and no natural means of transport to the site are available. The policy is to reintroduce plants several times, knowing that different seasonal conditions will favor different plants.

The board is increasingly aware of the importance of sustaining local subspecies and the need to find plant sources in the genetic neighborhood of the park. Some native species that are currently unavailable in the trade are being propagated in place in the park and also grown under contract with local propagators. Although initial baseline monitoring showed that there was little environmental rationale to past plantings, all new plantings reflect native communities and natural patterns. As the potential of this landscape is revealed, those responsible for its care raise their expectations.

Because the managers of Central Park are trying to look at whole systems, it is not surprising that they have turned their attention to the soil. They first tackled the problem of extensive areas of bare and compacted soil. The solution included a restored path system that focused on meeting the needs of the visitor while stabilizing and protecting the soil. But even where they had successfully reestablished a continuous litter layer, the ground was still very different from that of a more natural forest and far from a habitat for salamanders and other creatures of the woodland floor. The webby mycelia of fungi binding leafy mats that are so conspicuous in the litter of a natural forest were noticeably absent. Mushroom fruiting bodies were also uncommon, but earthworms were as thick as in a cornfield. The standard, routine soil tests gave no information about the living components of the soil.

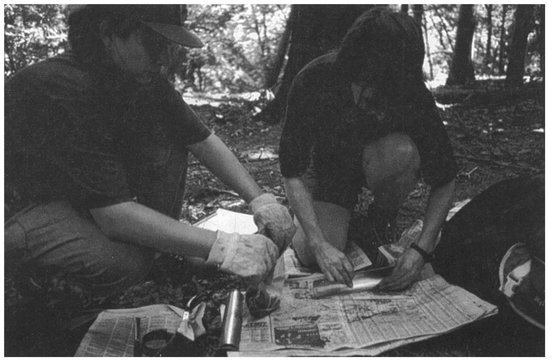

The Central Park Conservancy and the New York Department of Parks and Recreation initiated several new tests intended to examine the soil more closely. Margaret Carreiro of Fordham University and her graduate students (Figure 20.5) are completing the first study ever of mycorrhizae under urban conditions. It should be noted that this is literally a groundbreaking study, for not only is it the first of its kind in the eastern temperate forest, but the effort required purchasing increasingly powerful augers to deal with the tremendous levels of compaction in the soils. One of her students, Emer Macguire, looked at the ectomycorrhizae, which are common fungi associated with forest trees. The initial results suggest that fungal populations are reduced but not absent, although they occur at greater depths than would be typical of a less-disturbed soil with less surface compaction. Carreiro et al. will later compare their frequency with that on oaks in less-disturbed wooded areas that serve as the site restoration models on the outskirts of the city.

Figure 20.5. Researchers in Central Park take soil cores to study the impacts of disturbance and urban conditions on the soil fungi associated with oak trees in both lawns and woodlands. (Photo by Sara Cedar Miller/Central Park Conservancy)

Another student, James Butler, who is working with Steward Pickett, an ecologist from the Institute for Ecosystem Studies, is evaluating the mycorrhizal potential of differing soils, including those of Central Park.

Early on the Woodlands Advisory Board set the goal of becoming a research center for urban forestry. Today, important research is being performed in the North Woods.

There is no end of interesting ways to look at restoration in the context of this complex site. To the historian there is a wealth of uninterpreted information in this park, from the Revolutionary-era soldiers’ encampments and the ruins of the famous Mount Saint Vincent’s Hospital to the remnants of a Native American village. For the landscape architect the design by Olmsted and Vaux is still timely and yet consistent with the current focus on restoring the natural ecosystems of the park.

The ultimate success of this project is dependent upon changing how the park is used and perceived. Nothing conveys this message so well as coming upon the woodland crew and volunteers at work. Much has been accomplished in only a few years, and it appears probable that, with effective management, the North Woods can sustain a remarkable amount of wildness in the heart of the city and the grandeur of Olmsted’s original vision.