CHAPTER 22

Ground Stabilization and Soil Building

Restoration usually begins on the ground. Restabilizing the ground surface is a prerequisite to revitalizing the soil, which is essential to reestablishing native plant and animal communities. Existing problems tend to worsen without soil restoration. Once eroded, a path continues to channel and concentrate runoff, increasing its erosive force. A compacted area attracts more off-trail traffic that further inhibits germination and root growth. Although the damage to the ground in many fragmented landscapes often seems overwhelming and difficult to prioritize, it is essential to initiate repair of the landscape as quickly as possible.

The issues involved in soil restoration are complex and range from reducing negative impacts by users and managers to reintroducing invertebrates and fungi. All are complexly interrelated. Your first priority should be to focus on protection and restoration in those areas that support the most diverse native communities. Therefore, you will want to begin your restoration efforts in the areas that will best serve to protect the most intact natural communities that remain. Second, you should always avoid or minimize any new impact.

You will likely encounter many problems related to soil restoration on your site. This chapter describes strategies and techniques for stabilizing and building soil:

- Providing appropriate access

- Minimizing disturbance

- Retaining stormwater

- Removing fill and debris

- Stabilizing slopes and gullies

- Replacing and amending soils

- Repairing compacted soils

- Stabilizing the surface

- Managing dead wood and brush

Providing Appropriate Access

Restoration and management require appropriate access to the landscape so that visitors and managers may engage in positive uses of the site. The object is not to wall off natural areas, leaving nature to take its course, but to intervene intentionally to manage resources. Access is necessary; without good paths, people trample at will and do far more damage than they would otherwise. But determining what level and kind of access are appropriate is a difficult task. We generally overestimate our need to access a landscape, especially with vehicles, and underestimate negative impacts. Many natural areas are far too easily accessed and vandalized.

Guidelines for Access

• Evaluate the nature of current access, its impacts, and the real need for access.

Evaluate both legal and illegal access as well as the source areas. Correcting the problems may require working with local community groups to create new opportunities for positive uses and improve local site surveillance.

• Do not accept damage as a consequence of access; rather, accommodate access in ways that do not degrade the resource.

Focus on establishing positive access, such as multiuse trails. Determine the most minimal access requirements and evaluate how to meet them with the least impact.

• Where unauthorized vehicular access occurs, effective barriers as well as signage and periodic enforcement may be necessary.

Solutions range from fences and chains to berms and rock piles. The availability of materials should determine the nature of the barrier.

Guidelines for Nonvehicular Trails

A path is an attempt to balance impacts: it offers protection to the surrounding ground surface as well as a means to confine pedestrian or vehicular use, but it is also a source of disturbance. Open any new trail with great care. It will have long-term impacts on the landscape and entails a commitment to maintenance. Most paths in urban wildlands are undermaintained and become sources of stormwater damage, trash, and exotics. Often deterioration proceeds so far that outlaw trails are indistinguishable from once-paved paths.

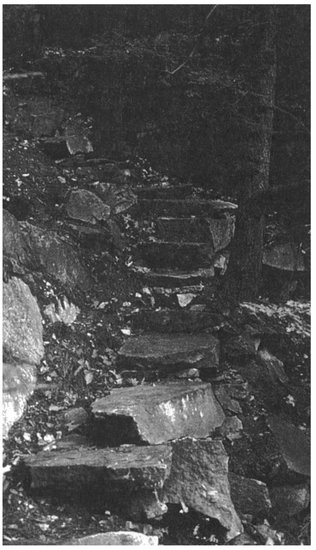

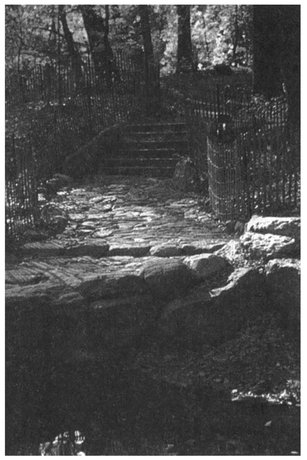

A multiple-scale trail system is often the most practical approach to dealing with differing site conditions and providing for visitor needs. The system might include a main trail accessible to vehicles for maintenance and security purposes as well as to wheelchairs and other assisted access. The secondary trail system might be for pedestrians only, or it might also include bike loops and horse trails. Consider a single-file adventure trail to permit limited access to special places that walkers consistently favor, such as an overlook or pond edge where a wider trail would be inappropriate. The use of large stepping stones or wood rounds on adventure trails minimizes construction of hard surfaces (Figure 22.1). Boardwalks and bridges are often the most successful access in lowlands.

Figure 22.1. Well-set stepping stones create an adventure trail that gives some of the feeling of going off the trail but without the impacts.

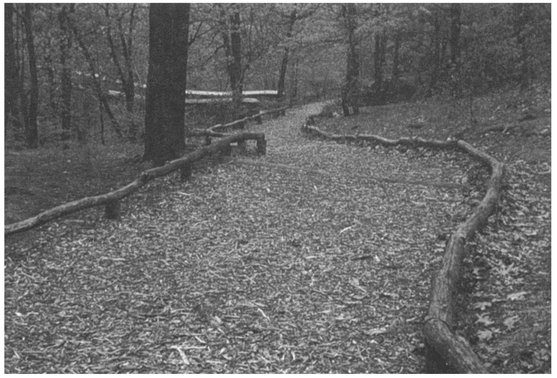

Wherever new pathways are proposed, first lay them out on the ground so they may be evaluated and modified as needed. The design of the trail is a crucial component in controlling erosion. Well-sited trails designed with the proper surface and drainage can minimize environmental impacts and are simply more maintainable. Signage is also important to inform the visitor about access. On heavily used trails, consider a low rail to contain walkers and protect adjacent vegetation (Figure 22.2).

• Monitor and repair all trails on a periodic basis.

The major purpose of trail maintenance is to control erosion. All access results in impacts. The only way to ensure against unacceptable levels of damage is to monitor and then take action when the first sign of damage is noted. Evaluate the condition of the infrastructure, identify potentially hazardous conditions, and recommend appropriate actions. Evaluate the condition of trees and branches overhanging major public walkways to help minimize the risk to visitors from falling limbs and trees.

• The path surface must be adequate to carry the level of traffic it receives.

Over time, the condition of the trail itself will illustrate the need for a more durable surface or better care. Periodic graveling may be needed where use is moderate. Where use is heaviest, a paved surface is typically required.

Bare soil is not an acceptable path surface in a heavily used park because it wears poorly and cannot be distinguished from an outlaw trail. When bare soil is visible anywhere, people feel free to trample far more casually than when paths are well maintained and erosion well controlled. Therefore, you will need to eradicate and revegetate all bare-earth, desire-line trails and restabilize all areas of bare soil. Boardwalk is an excellent solution in any fragile habitat, not only wetlands. It conveys a strong message to the visitor about the fragility of the landscape. A boardwalk effectively contains pedestrian movement and can often provide barrier-free access in uneven terrain with less site modification than is required for a shallow-grade path. Many simple boardwalk designs can be implemented by volunteers.

Several excellent trail maintenance handbooks are available. For copies, contact the publishers listed below:

Trail Building and Maintenance, 2d edition, by Robert D. Proudman and Reuben Rajala (1981). Appalachian Mountain Club, 5 Joy Street, Boston, MA 02108, 617-523-0636.

Trail Design, Construction, and Maintenance, by William Birchard, Jr,. and Robert D. Proudman (1981). The Appalachian Trail Stewardship Series. Appalachian Trail Conference, PO. Box 236, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425, 304-535-6331.

Appalachian Trail Fieldbook — A Self-Help Guide for Trail Maintenance, by William Birchard, Jr., and Robert D. Proudman (1982). The Appalachian Trail Stewardship Series. Appalachian Trail Conference, P.O. Box 236, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425, 304-535-6331.

Figure 22.2. In the New York Botanical Garden a low wooden rail substantially reduces off trail damage along the main path. (Photo by Marianne Cramer/Central Park Conservancy)

Trails Manual — Equestrian Trails, by Charles Vogel (1982). Equestrian Trails, Inc., 13741 Foothill Boulevard, Sylmar, CA 91342, 818-362-6819.

These manuals are geared to larger, wilder areas than many of those found in more urban areas, but the techniques are still applicable, especially where paths are largely unpaved. Also very worthwhile is a series of English trail manuals designed for volunteer conservation corps. The numerous topics covered illustrate the very sophisticated level of maintenance sustaining a public and private trail network in Britain that is centuries old in places. Compiled by Alan Brooks, The Practical Conservation Handbooks were revised in 1982 by Elizabeth Agate. Titles include Waterways and Wetlands and Footpaths. The handbooks are published by the British Trust for Conservation Volunteers, 36 St. Mary’s Street, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX10 OEU, telephone: 0491-39766.

For a thorough guide to developing and maintaining multiuse trails, consider Trails for the 21st Century: Planning and Design, edited by Karen-Lee Ryan et al., published by Island Press, 1993. This manual was developed by the Rails to Trails Conservancy in cooperation with the National Park Service.

Temporary Access

Before starting any site work, think carefully about its possible impacts. Well-meaning weeders trample soil no differently from walkers wandering off the trail. Select your route carefully, keeping to permanent trails to the extent possible.

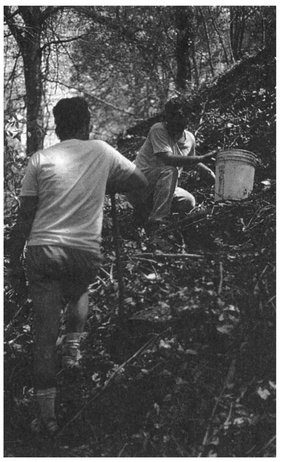

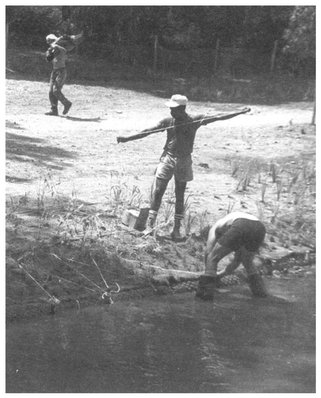

When working off-trail, consider using a bucket-brigade line to convey materials, including plants, to minimize trampling (Figure 22.3). Instead of everyone walking back and forth, the carefully placed individuals in the line pass materials back and forth from person to person. Route access through areas of disturbance or walk over exotics while avoiding those areas where native reproduction is still occurring.

Any access, even by small-wheeled vehicles, is potentially damaging. Use planks on the ground, for example, to keep from making wheelbarrow ruts. Several workers can carry fairly large loads, such as rocks in nylon cargo slings. For heavier loads, try using rollers. Study the site before starting work, and be sure everyone is informed about each step of the procedure.

Minimizing Disturbance

Finding a construction site in the Northeast that is not surrounded by dusty roads and muddy creeks is next to impossible. The use of protective site fencing to preserve natural areas is even rarer. Parks and wildlands often end up as dumping grounds and staging areas for adjacent construction projects. Even restoration work entails at least some level of additional disturbance. Consider advocating and/or instituting the following steps to minimize disturbance:

• Install fencing wherever potentially damaging activities, such as site work and construction, are carried out.

Fencing and enforcement are required to effectively contain large equipment. On an active construction site, inspect and repair fencing three times daily: once prior to starting work, at midday, and upon closing the site after work each day. Enforcement is important, it must start on day one, and must be reinforced repeatedly.

There are several major kinds of site fencing, each of varying strengths, from chain-link, for the most extreme situations, on sites where no access at all is permissible, to plastic site or wooden “snow” fencing (Figure 22.4) in the least problematic situations. Range and box wire fencing (Figure 22.5) are adequate for intermediate levels of protection. Be careful not to damage existing vegetation in the course of installing or removing fencing. For most types of fence, the shorter the distance between posts the sturdier the fence. But while strong fencing seems desirable, it is also expensive and may involve more damage during installation. A complementary program of education and enforcement may be more effective than increasing the strength of fencing.

Figure 22.3. A bucket brigade minimizes damage by workers on-site.

Figure 22.4. Site fencing keeps visitors on the renovated path while the landscape beside it grows after restabilization and planting.

Figure 22.5. Range fencing in Central Park protects small channel islands from disturbance while vegetation becomes established.

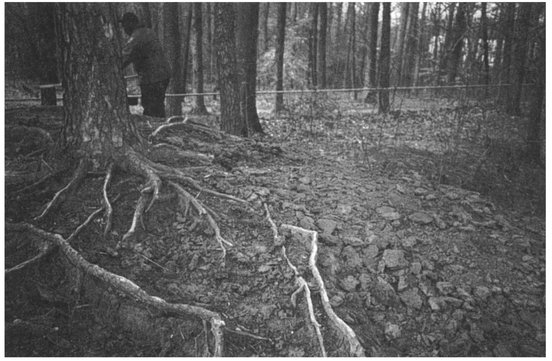

• Where fencing is used, either permanently or temporarily, extend protection to as large an area containing root systems as possible.

Begin the effort to protect roots by trying to determine where they may be. Assessing the exact pattern in which roots grow is not easy; people usually underestimate their extent. Roots are notoriously opportunistic and go where the gettin’ is good. The patterns of forest plant roots are complex, ranging over extensive ground in adaptive patterns rather than predictable ones. For an open-grown tree the rule of thumb for estimating the area of important roots is to start with the area of the outermost limit of the branches, extended by half again. Remember, though, that variability is high. Root systems in the forest often overlap. Study the visible indicators of the root zone, such as raised soil over roots that are close to the surface.

Remember, too, that fencing often alters walking patterns and may even lead to the creation of new desire-line trails. Walkers, for example, often follow the outside edge of a new fence.

• Evaluate the potential for damage and develop a strategy to minimize root damage where disturbance is inevitable.

Damage exceeding one-third of the root system is likely to lead to the death of even the most hardy specimen. Even when you decide to dig manually rather than using earth-moving equipment, you still may not be able to reduce root damage sufficiently and will need to explore other options. Where the damage will be too severe to save the tree, consider leaving the tree to die in place if it presents no likely hazard. Where a larger tree presents too great a liability, try cutting the top to remove the wide canopy only, leaving the trunk as a snag to serve as a den tree and insect habitat. Elsewhere it may be advisable to consider cutting down a tree that will be excessively damaged and encourage new shoots, called “coppice growth,” from whatever roots remain. In a few cases, horticultural root pruning undertaken at least a year or even several years prior to possible damage may be used to try to save special vegetation. In general, however, root pruning is very expensive and entails damage to adjacent plants and therefore should be avoided except in the most exceptional situations. Tunneling beneath roots is an option in some cases.

• Hand-dig wherever root impacts are probable.

Hand-digging is costly but not as expensive as attempting to replace the value of what might be lost. When excavating manually, attempt to save all roots 2 inches or greater in diameter. Wherever a root is cut or accidentally damaged, be sure to trim any ragged ends to leave a clean cut. Do not paint or treat the wounds in any other way. Be aware, however, that even hand-digging will do damage, especially to smaller plants, shallow-rooted species, and plants growing in thin soils.

• Keep any roots exposed by excavation damp or they will die.

Backfill as soon as possible; use wet straw or burlap as an interim cover if there is any delay. Remove any excavated trash from the spoil, and make sure no trash is disposed over the area of root excavation. Compact the backfill a few inches at a time to the original firmness, except at the surface if the soil had been overly compacted. Water the backfill to eliminate air pockets and moisten roots.

• Where root damage has occurred, evaluate the need for additional irrigation during drought conditions for at least a two-year recovery period.

Plants do not recover immediately from stress; it takes time for roots to regrow. Monitor the soil’s moisture to ensure that you water only when necessary to sustain valuable plants through a drought immediately after root loss. Do not fertilize a damaged plant because the resulting new growth typically creates an increased demand for water that the compromised roots are not able to meet. If the plant was not pruned beforehand, pruning the shoots to compensate for root loss may be advisable, although it should be done with caution. This once popular approach has recently been called into question by experiments at Cornell University demonstrating that pruning to make up for root loss does not benefit a newly transplanted tree. Instead, a new transplant seems to benefit from any and all leaves because of the net energy gained from its greater leaf area. Similar studies have not yet been carried out under forest conditions.

• Where trenching or excavation must be undertaken, take special measures to minimize damage.

You may wish to refer to a simple handbook on trenching, Trenching And Tunneling Near Trees: A Field Pocket Guide For Qualified Utility Workers. [Tree City USA Bulletin], edited by James R. Fazio. National Arbor Day Foundation, 100 Arbor Avenue, Nebraska City, NE 68410.

• Silt fencing and other runoff controls are needed wherever soil is exposed to increased erosion.

Erosion and sedimentation in natural areas caused by poor runoff control in nearby construction areas is commonplace. Be sure to work closely with your local soil conservation service agents to ensure better enforcement. Maintaining adequate erosion and sedimentation control on your own site is equally important, even for very small scale projects that are not subject to regulatory review.

Silt fencing may consist of hay bales staked in place or fabric barriers staked along the land’s contours to retard runoff and trap sediment. The most effective silt barriers start below grade in a shallow trench, but their installation means damage to soil structure that would not be acceptable in any relatively undisturbed area. Simple straw bales staked into the ground to secure them are less effective but usually entail much less damage. You can somewhat compensate for the lack of effectiveness by decreasing the spacing between the lines of bales. Always try to minimize the erosion potential overall by minimizing the amount of land area exposed at any one time. Likewise, do not clear the entire work area at once if it is not necessary.

Retaining Stormwater

You can make a variety of small changes to terrain to modify drainage characteristics of the landscape. Some techniques are only suitable where existing plants can be replaced with vegetation that is equally valuable. Many effective methods entail some soil disturbance. Soil bioengineering techniques such as brush layering and live staking, described later in this chapter, are exceptionally useful where flows are heavy and the establishment of vegetation would otherwise be impossible without added protection. These techniques are less suitable for a wooded stream corridor, where only limited soil disturbance can be tolerated. The most difficult areas to restabilize are woodlands because even minimal grading damages vegetation, and reestablishing plants is difficult because of shade or the specialized requirements of many forest species.

Wherever there are open areas such as lawn or even pavement, there are likely to be opportunities for collecting and storing excessive surface runoff until it can naturally infiltrate the ground. The most obvious choices for water storage impoundments are places where there is already occasional standing water and where a slight increase in the water level could improve retention and infiltration. This is especially true for lawn areas, where even a gentle slope can result in rapid rates of runoff.

Small-scale impoundments can retain rainwater long enough to greatly improve infiltration rates locally. They are advisable for lawn areas near woodlands, streams, and wherever rapid runoff presents a problem. A small berm, a dike to contain and direct runoff, even only 4 to 6 inches high, placed on the low side of a patch of lawn or open field can change drainage characteristics significantly (Figure 22.6). While no single such impoundment will make a great difference, many small sites placed throughout the landscape can decrease runoff at a regional scale.

Where the slope is long, low, and largely open, a sequence of berms and trenches can be effective in slowing stormwater movement downslope to effect better infiltration. The number, spacing, and sizing of the trenches and berms will vary with the site. The idea is to create many small opportunities for storage and infiltration. Remember that digging trenches and making berms are forms of disturbance that are not suitable where less-intrusive methods would work as well or where native soils or vegetation are undisturbed. On most sites you can build a berm with the soil from the trench and do not need to transport additional soil to the site.

Figure 22.6. This flat depression in the turf is also a retention area that fills with water for a few hours after a rain to create a round, ephemeral reflecting pool.

A series of berms and trenches as well as bands of tall grass to filter runoff can diminish damage due to runoff from such areas as athletic fields and other parklands to adjacent seminatural areas. Allow the berms and trenches to grow tall grasses and wildflowers if the site must otherwise be kept open for some purpose; otherwise the goal should be to manage for a gradual return to forest.

Under woodland conditions where the construction of berms and trenches on a slope may be too damaging, you can minimize the downslope movement of water by establishing a shallow berm along and outside the upslope edge of the forest in adjacent less-vulnerable landscapes. Depending on soil conditions, the berm can sometimes be augmented by a shallow, gravel-filled infiltration trench that runs parallel to the berm; otherwise the trench may silt in rapidly. A filter fabric lining in the trench between the soil and gravel will help maintain the berm’s permeability longer. Filter fabrics allow water but not small particles to pass through and therefore keep sediment from filling the gravel bed. Another important factor to consider is any potential impact to the stability of the slope (Figure 22.7). Remember that the berm must be at right angles to the slope or it will convey water in the downslope direction.

Although only a small volume of runoff can be held and recharged in this manner in any one place, if these measures are repeated throughout a watershed or continuously along a slope, you can achieve significant restoration of historic drainage patterns.

Figure 22.7. Typical sections for shallow bermed impoundments.

Shallow excavations are sometimes used to augment retention in upland areas. Shallow depressions maintained in turf grass tolerate periods of brief inundation. Low spots planted as a native wet meadow of ferns, sedges, rushes, or lowland trees and shrubs tolerate longer periods of standing water (Figure 22.8). As before, it is important that the runoff does not carry high sediment loads or these areas will silt in too rapidly. If bare soil areas are appropriately stabilized, however, sedimentation should not be a problem.

The sources of water for upland wetlands and shallow pools include floodwaters from adjacent streams and rainwater. If the outflow of a pool is between 1 and 2 feet higher than the new wetland’s lowest elevation, it will retain some water seasonally. If at all possible, construct a simple water-control structure to enable you to manipulate water levels, especially in the early years when vegetation is becoming established. All slopes should be shallow enough to be stable even without vegetative cover. If you vary the bottom elevations, you can avoid monocultures such as cattail.

Figure 22.8. Volunteers in Wissahickon Park in Philadelphia combined exotics removal with stormwater management by diverting small amounts of runoff to the depressions left behind where knotweed roots were grubbed and by planting native species, such as witch hazel and skunk cabbage.

Natural regeneration is likely to be best in new wetlands that are adjacent to existing wetlands. The suitability of plant species depends on the depth and duration of standing water. Some tree species, such as persimmon and buttonbush, will tolerate flooding for more than one year, while swamp white oak and basswood will tolerate less than a month during the growing season. Other species, primarily herbaceous, occur in areas that are permanently underwater. Blue iris and lizardtail, for example, are found in shallow water about a half foot or so in depth, while sweet flag and pickerelweed are more likely to be found between 6 and 18 inches in depth. Water lilies are still deeper. There are many excellent references on wetlands planting available. Restoring a more natural, that is, seasonal hydrologic regime to a wetland area can be very beneficial for germinating seeds that often require a relatively dry period.

Choose wetland plants with care. In some instances grasses, such as fescue, planted as temporary cover in basins persist to become future pests. Switchgrass is an excellent native substitute for exotic redtop and annual rye for stabilization purposes and will soon die out wherever there is standing water, permitting other species to become established.

When revegetating wetlands, consider using both seeds and plugs. Plugs, ready-to-plant seedlings, are more reliable and develop faster but are more costly. Seeds are prone to rotting in wetlands and may require reseeding.

In less-disturbed forests where erosion and sedimentation are not serious, consider creating a seasonal wetland to help restore historic hydrologic conditions. “Ephemeral pools” are seasonal wetlands. Because many are too small to be protected under wetlands legislation, ephemeral pools are being filled or converted to open water habitat. For some species, like salamanders, pools like these are essential because they dry up part of the year and so cannot support fish that prey on salamander larvae. Ephemeral pools require very low levels of sediment and minimal fluctuations in water level in order to sustain rich amphibian populations, so they are not necessarily good options for controlling excess runoff. Ephemeral pools also require proximity to forest because salamanders and many frogs cannot cross far over open fields, much less roads.

Many ephemeral pools are the result of seasonal high groundwater or perched water tables created by spring rains and snowmelt over soils with low permeability. These are called “vernal pools.” Groundwater-dependent pools generally have the least fluctuation and may therefore be quite shallow. Where pools must rely on surface water only they will also require refugia. “Refugia” are simply deeper areas in the pool that serve as a safe haven during periods of fluctuating water, which is likely when you have only surface water to support the pool. Where there is flowing water at least seasonally, it is also important to ensure that there are also areas of still water with vegetation where species can attach their eggs.

Improvements to in-stream habitats can also help to increase retention and reduce runoff as well as manage sediment. The general goal is to re-create the varied environments of a natural channel when they have been modified by excess runoff or channelization. Boulders placed in a stream channel provide cover for small creatures and vary the current, which in turn varies the habitat. Similarly, you can place channel-lining rocks to re-create natural patterns of riffles and pools, which typically recur approximately every six times the width of the stream. You can also excavate small pools in the channel bottom or create shallow plunge pools using low checkdams to restore more normal flow patterns.

The best journal on watershed management is Watershed Protection Techniques: A Periodic Journal on Urban Watershed Restoration and Protection Tools, published by the Center for Watershed Protection, 8737 Colesville Road, Suite 300, Silver Spring, MD 20910, 301-589-1890. They also publish an excellent book entitled Site Planning for Urban Stream Restoration.

The best journal on establishing wetlands is Wetland Journal, published by Environmental Concern Inc., P.O. Box P, St. Michaels, MD 21663, 410-745-9620.

For an excellent manual on how to protect streams, see Living Waters: How to Save Your Local Stream, by Owen D. Owens, published in 1993 by Rutgers University Press, 109 Church Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, 732-445-7762.

For stream restoration techniques, see Better Trout Habitat: A Guide to Stream Restoration and Management, by Christopher J. Hunter (Island Press, 1991), and Stream Analysis and Fish Habitat Design: A Field Manual, by Robert W. Gastonbury and Marc N. Gastonbury (1993), published by Newbury Hydraulics, Box 1173, Gibsons, British Columbia, Canada V0N 1V0, 604-886-4625.

An excellent manual on restoring a variety of habitats, including lowlands and streamsides, is Restoring Natural Habitats: A Manual for Habitat Restoration in the Greater Toronto Bioregion, prepared by Hough Woodland Naylor Dance, Ltd., and Gore and Storie, Ltd. (1995) for the Waterfront Regeneration Trust, 207 Queen’s Quay West, Suite 580, Toronto, Canada M5J 1A7, 416-314-9490.

Toronto, Canada, has an excellent school program geared to amphibian conservation and restoration that is described in For the Love of Frogs Build a Pond, published by the Metro Toronto Zoo (1992). Contact the Adopt a Pond Program, P.O. Box 280, Westhill, Ontario, Canada M1E 4R5.

Removing Fill and Debris

Reestablishing the historic terrain is an important aspect of restoring natural patterns. Therefore, the first step before initiating any ground stabilization is to evaluate the site to determine where and the extent to which grading has occurred and whether the natural terrain can be restored. You should also attempt to compare the vegetation that would be affected by regrading with what you feel can be reestablished.

The more recently the filling occurred (optimally, no more than a season or two), the more likely that removing the fill will save existing plants that were not cleared or severely damaged. Pull some fill away from the remnant tree trunks to examine the condition of the bark. Some species, such as sycamore, are more tolerant than others and may survive years under partial fill, sending numerous adventitious roots out from the buried portion of their trunks. Others, like tulip poplar, are much more sensitive and may show signs of bark rotting after only months. If the trees still appear alive and vigorous and do not show signs like dieback at the tips, loss of limbs, or broad areas of rotting bark, consider removing the fill. Substantial hand labor may be necessary to keep from further damaging the soil with heavy equipment.

• Sometimes fill removal is required just to reduce problematic grades and permit adequate slope stabilization.

Typically, a slope steeper than 3 feet horizontal to 1 foot vertical (about a 33 percent slope) on fill soils will have persistent problems of stability over the long term. Where the major vegetation has been killed by filling, complete regrading may be needed to restore the original terrain or at least reduce the slope’s steepness. Use the lightest equipment possible to minimize damage to the soil. A small dragline operated from the top of the slope to pull the fill away from the site may be a feasible method. Once the fill is removed, restabilize the ground as soon as possible.

• Reuse soil to the extent feasible and properly dispose of the remainder.

This step will require some real follow-through on your part. Transport is costly and disposal often creates environmental problems elsewhere. Reuse as much of what is removed as possible, separating the rocks and soil in the fill and using them elsewhere.

• When fill is left behind, it often causes long-term problems for vegetation management.

If the fill cannot be entirely removed, or too little can be removed to save existing vegetation, it may be necessary to cut down the dead or dying trees along walkways and wherever else they pose a hazard. Otherwise, leave dead trees in place for their value to wildlife. In either case, keep the trunk and branches for use on-site to restore the ground layer.

Filled slopes and valleys are often easily colonized by exotic invasives; therefore, control of exotics and replanting of native species are likely to be required on a continuous basis. Many such urban sites contain tons of construction rubble that years after deposition still support only mugwort, common reed, and a few isolated tree-of-heaven. The fill material is usually of very poor composition and may be excessively drained, very poorly drained, or both in patches. Adding a costly layer of topsoil is not enough to address the long-term problems of these areas, although it may support plants for a while before they start to die off.

Improving these areas is challenging. It is usually necessary to undertake detailed investigations of what comprises the fill before making any final decisions. At the very least, remove junked automobiles and old appliances, tires, and other large rubbish very carefully to avoid undue disturbance to the site. Remove all the trash you can. Any rubbish left behind is only an incentive for further dumping. As with graffiti, the most effective approach to dealing with trash is to promptly remove it.

In some places, construction rubble may be so mixed in with the fill soil that separation and removal of the rubble component is extremely difficult and removal of the entire layer too extreme. Do not expect such sites to support more than the toughest plant communities, at least for a long time. The presence of continuous cover alone will ameliorate extremely bad conditions by loosening soil and adding organic matter over time.

Never simply dispose of large boulders recovered from fill; they are usually extremely valuable. They can be used in streams to enhance habitat and make artificial “bedrock” surfaces to create single-file adventure trails. A boulder trail for climbing on or a path edged with boulders provides access and yet serves to protect the more sensitive areas of the landscape, such as the water’s edge.

Stabilizing Slopes and Gullies

Not all erosion problems can be solved by vegetation alone. Where erosion is severe and has created gullies, soil replacement and additional support are necessary to hold the terrain in place until vegetation can become reestablished. Where runoff rates are so rapid that even established vegetation is damaged by stormwater, replanting alone will be ineffective, at least until better watershed management reduces flow volumes and velocities. Where current rates of runoff cannot be reduced, it may be necessary to enlarge and/or reinforce the channel using techniques such as bioengineering.

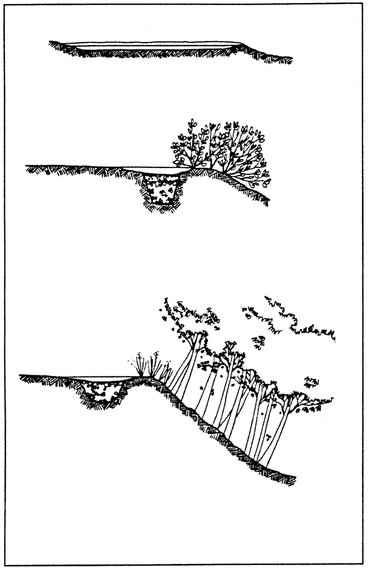

Biotechnical Slope Stabilization

“Biotechnical slope stabilization,” also called “soil bioengineering,” uses living and dead vegetation as well as various soil amendments to provide a greater degree of stability than that afforded by conventional grading and subsequent replanting. Under forested conditions, however, biotechnical slope stabilization may be of limited use because there is rarely adequate light to stimulate adequate shoot development. More important, many of the techniques entail significant soil moving, which is often not possible under forested conditions without causing undue damage. In general, it is best used in extreme circumstances, where there has been severe disturbance and there is no need to protect any remaining vegetation.

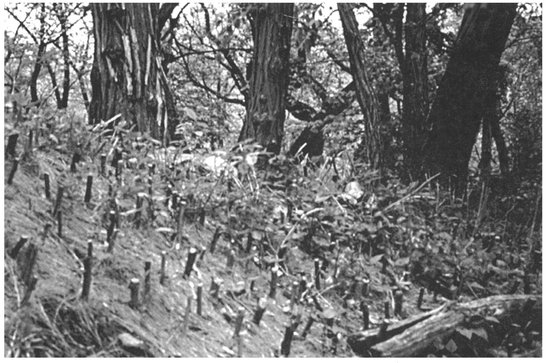

Live Staking

Live stakes are living pieces of stems or branches taken from trees or shrubs with the ability to root vigorously from cuttings that are driven into the soil and eventually root in place (Figure 22.9). In one bioengineering technique, they are used as vegetative stock for new plants and, like reinforcing bars in concrete, give added structural support to the soil. Soon after planting, the brush begins to develop roots, which further stabilize the soil column, often to a great depth, while the plants rapidly develop woody shoots above ground. Sometimes herbaceous cuttings are used as well as freshly cut branches that are still unrooted when planted.

Many native floodplain and wetland species — including willows of all kinds, many elderberries, shrub dogwoods, box elder, and, less reliably, sycamore, alder, and viburnum — are especially suited to this technique because of their tendency to root easily from cuttings, especially when covered with soil. Usually at least 40 percent willow is incorporated because it serves to stimulate rapid rooting of other species.

Figure 22.9. Live stakes will root deeply if they are driven in right side up and at a 45-degree angle.

Beyond its remarkable suitability for bank and slope stabilization, live staking is a useful planting method that employs lightweight materials that can be harvested locally. Although only a handful of species can be established this way, the rapid establishment and effective stabilization afforded by this method make it appealing in special circumstances.

Some hints, learned through experience:

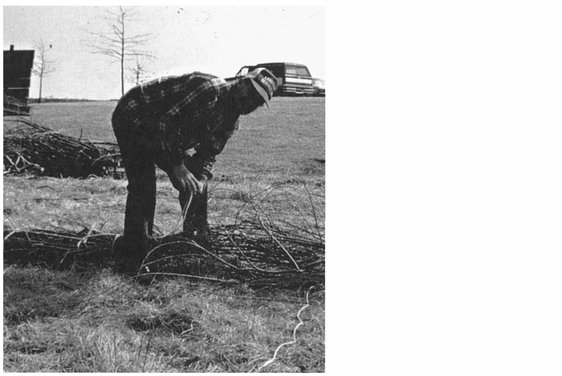

• Live staking works best with vigorous cuttings.

Look for firm green wood. You can harvest the same site repeatedly because species like willow, alder, and other plants used for live stakes sprout readily after cutting. This practice, called “coppicing,” has been practiced for millennia, especially for basketry, and uses the same materials that are ideal for bioengineering.

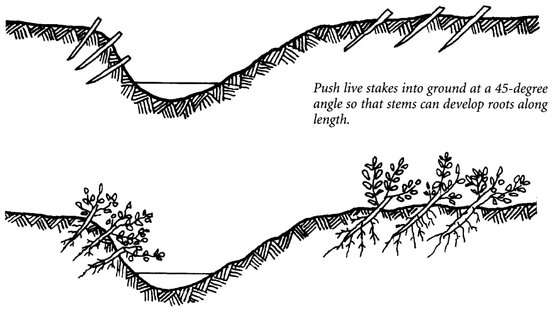

When unrooted cuttings are used, collect and plant them on the same day if possible and no more than twenty-four hours after harvesting. Keep them moist during that time; do not let them dry out completely. The window for installation is also very narrow, confined to the coldest part of the winter, when the plants are completely dormant, which is typically during the month of February and a bit of March. The season must be advanced enough that the ground can be worked but not so late that buds are swelling.

Each cutting must have at least two bud scars near the top of the shoot. Cut the larger or butt end of the cutting at a 45-degree angle to help drive it into the ground as well as to indicate which end goes into the ground. Upside-down stakes do not grow. Cut the top end blunt or square. Tamp the cuttings into the ground at a 45-degree angle to maximize rooting. Use a dead blow hammer that has sand or shot in the hammerhead to absorb the shock of the blow rather than splitting the stake. Discard any stakes that split. In hard soil you can use an iron bar to create a pilot hole before planting. You can also drive live stakes between rip-rap and gabions (rock-filled baskets) to help establish vegetation along armored streambanks.

Fascines

Fascines are fresh, long cuttings secured every foot and a half with wire or twine to create a long roll about 6 to 8 inches thick. A fascine works like a cable to reinforce a stream edge or steep slope. The cuttings can be from 5 to 20 feet long and are easily constructed on-site (Figure 22.10).

Place the fascine in a freshly dug trench nearly the depth of the fascine and cover with soil (Figure 22.11). Use your gloved hand or a wooden stake to work the soil into air pockets in the fascine. Drive 18-inch-long split wooden stakes through the fascine about every 3 feet to secure it in the soil.

Fiber Roll

A fiber roll, or “fiberschine,” is a long, sausagelike roll of coir (coconut) fiber or other material that reinforces banks and serves as the planting medium for vegetative cuttings and small seedlings planted after installation. The roughly textured coconut fibers, protected in a coir or jute mesh, take about five to seven years to disintegrate, and until then slow the flow of water, thereby causing sediment to drop and become trapped around the new plants. The living roots and shoots of growing plants in the fiber roll as well as the accumulated sediment gradually replace the dead coir fiber, which serves as a durable but temporary aid in stabilization (Figures 22.12 22.13 22.14 22.15).

Figure 22.10. Workers easily construct fascines on-site.

Figure 22.11. The upper surface of the fascine should remain exposed to light after the trench is refilled.

Where less durability is required, you can use cheaper materials, such as straw, for the rolls. Fiber rolls help to avoid the use of stone gabions or sheet piling, and can be used with live staking.

To effectively apply these techniques, you should consult manuals available on biotechnical slope stabilization. You might start with these excellent references:

Bioengineering for Land Reclamation and Conservation, by Hugo Schiechtl (1980). University of Alberta Press, 141 Athabasca Hall, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E8.

A Streambank Stabilization and Management Guide for Pennsylvania Landowners, published by Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources, Office of Resources Management, Bureau of Water Resources Management, and Division of Scenic Waters (1986). State Bookstore, P.O. Box 1365, Harrisburg, PA 17105.

Water Resources Protection Technology, A Handbook of Measures to Protect Water Resources in Land Development, by J. Toby Tourbier and Richard Westmacott (1981). The Urban Land Institute, 1090 Vermont Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20005.

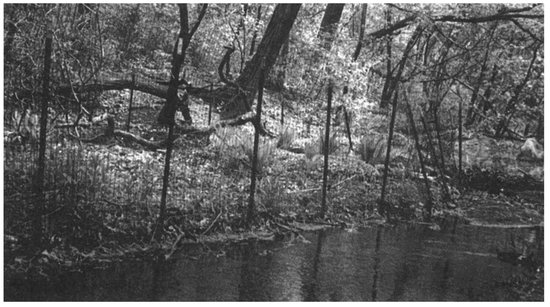

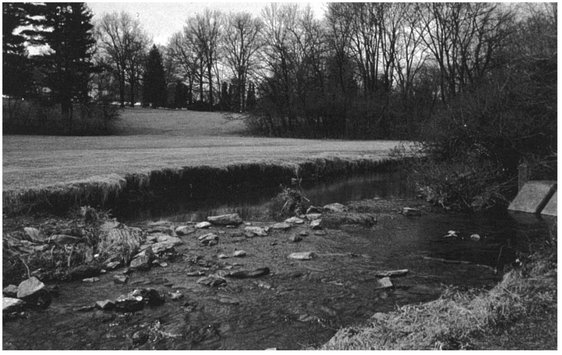

Figure 22.12. The stream in Trexler Park in Allentown, Pennsylvania, before restoration.

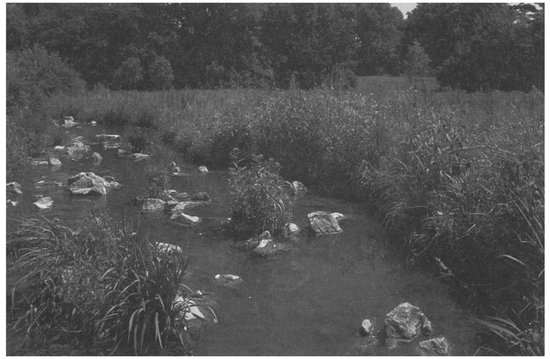

Figure 22.13. Creative Habitats in White Plains, New York, propagated sixty species of native plants and installed coir fiber rolls (fiberschines) to stabilize the new shoreline until the vegetation became established.

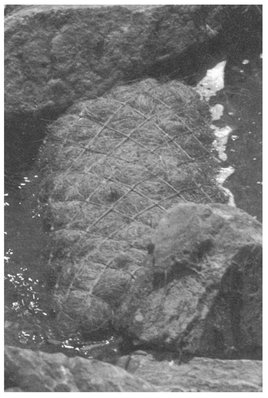

Figure 22.14. Close-up of a fiber roll.

Figure 22.15. Within a single season the corridor was transformed from an actively eroding channel to a richly vegetated wet meadow that stood up to several major storm events within weeks of installation.

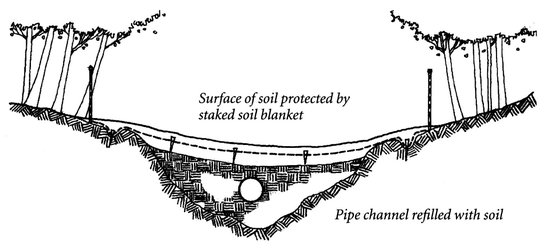

Figure 22.16. Where a pipe disgorges partway down a slope and gouges a gully, it is sometimes useful to extend the pipe and refill the gully. Evaluate where you can reduce the volume of water or provide retention for runoff without undue damage.

Biotechnical Slope Protection and Erosion Control, by Donald H. Gray and Andrew T. Leiser (1982). Van Nostrand Reinhold, 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020.

Workshops devoted to these techniques are held throughout the year across the country. Watch your local environmental newsletter for announcements.

Stabilizing Gullies and Erosion Channels

Where runoff has increased dramatically and has created deep gullies, the eroded gully is usually far larger than the actual volume needed to carry the runoff. This occurs because the increased velocity of runoff erodes the gully bottom and incises a deeper channel from which floodwaters cannot escape, which in turn increases the volume and velocity of the flow. In such cases, consider partially refilling and reinforcing the channel to allow it to carry the flow without eroding a deeper gully (Figure 22.16). Where the gully has been created by an outfall that conveys water partway downslope in a pipe but creates erosion where it emerges unpiped midway down the slope, consider extending the pipe to a point closer to the base of the slope where and if grades are shallower. You can then fill over the pipe and partially refill the rest of the ravine, leaving a large enough swale to carry surface runoff. The ground surface may not require further reinforcement if the outfall was the primary cause of the gully formation.

This slope protection method does not provide any retention and may aggravate storm surge-related problems, however. Ideally, retention should then occur at the base of the slope, although in many steep terrains that is difficult or not possible.

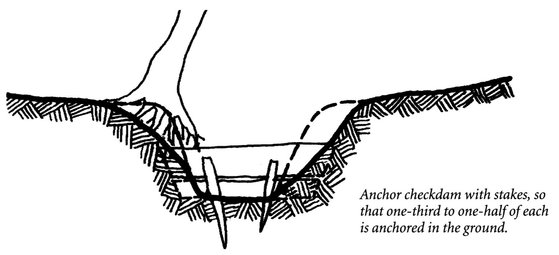

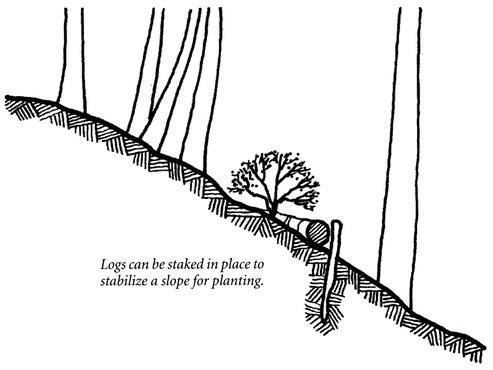

Where shallow gullies have formed, a series of low, wooden log checkdams or fiber rolls staked in place reduce the velocity of runoff and encourage the deposition of sediment within the gullies (Figure 22.17). Reducing the velocity of stormwater in turn reduces its capacity for erosion. Checkdams also foster sediment deposition all along the length of the gully rather than only at the bottom of the slope.

Figure 22.17. A stepped sequence of checkdams, designed as still pools and cascades, can reduce the erosive force of runoff in a channel. Checkdams slow the water enough for the sediment to settle out and accumulate inside on the slope above the dam.

Keep checkdams small and place them at frequent intervals. Start at the bottom of the slope and work upward (Figure 22.18). Locate the dams so that the top elevation of the downstream dam is no lower than the bottom elevation of the upstream dam or scour will occur. They also must be low enough to confine the flow of water within the gully or new channels will be cut at the sides in a major storm.

You can build checkdams from tree trunks and large branches found on the site. Checkdams made from wood typically do not last more than three or four years, by which time the site should be stabilized if runoff has been adequately controlled. You will not be able to complete gully restoration until the velocity of the runoff is reduced to a rate that does not adversely affect new vegetation once it is well established.

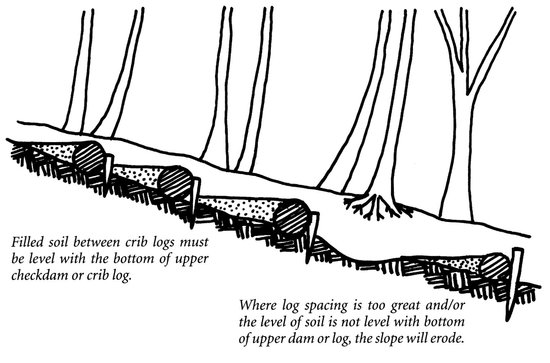

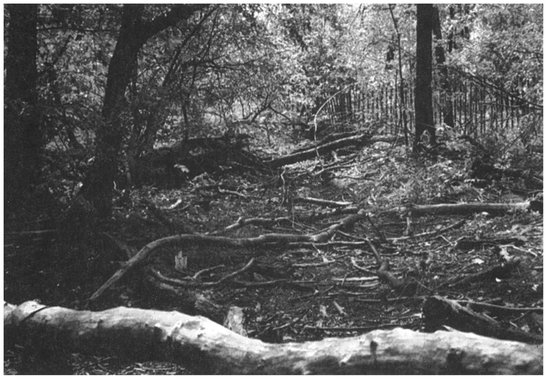

Cribbing

Cribbing is one of the most common techniques for repairing severely eroded slopes. Cribbing, or cribwork, generally consists of rigid supports, such as boards, logs, fiber rolls, or fascines, that are anchored in place like stair risers along the slope’s contours to slow the flow of water. They reduce the erosive force of runoff and encourage deposition and the gradual buildup of the slope.

You install cribbing like checkdams, starting at the bottom of the slope and working upward. Be sure to place the logs exactly parallel to the contours to ensure that you do not direct water downslope but rather hold it behind the log. Use a level to align the logs (as shown in Figure 22.18); then stake them to hold them in place. Drive the stakes to anchor the log at right angles to the slope and at 3-foot intervals along the logs.

Figure 22.18. The spacing of checkdams and cribbing is critical to erosion control.

Setting the log in a trench gives greater stability than placing it on the soil surface, but a trench is only appropriate where excavation will not unacceptably affect adjacent vegetation.

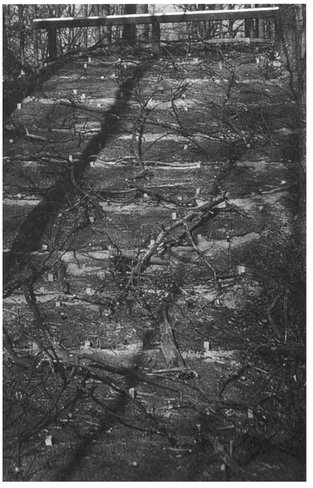

You can use untreated waste wood for cribwork. Where wood or logs are not available, you can use fascines made from brush. While they will not develop shoots under the shade of woodland conditions, they still serve to reinforce and retain soil and can be fashioned from locally available materials. Fiber rolls are also suitable. Place branches over the restored slope to help discourage trampling (Figure 22.19).

The two most common problems with cribwork are associated with commonly used, inappropriate cost-cutting measures. First, the “steps” may be spaced too widely, resulting in erosion between them and retarding permanent stabilization. Second, the size of each step may be increased to the point where no amount of deposition would ever create a natural terrain. Keep cribbing in small increments. You can always keep adding if you detect problems.

Evaluate the amount of sediment available to the site before deciding upon cribwork for long-term soil replenishment. In some places the soil available from runoff may never be enough to rebuild the slope, in which case it will indefinitely remain a stepped slope with exposed cribwork. The visible cribwork itself sometimes attracts trampling and even routine use because it provides a stairlike structure for climbing a slope.

These problems can be eliminated by immediately refilling the lost volume of soil to reestablish the desired grades rather than waiting for the process to occur incrementally over time. Although more costly, this “modified cribbing” is often well worth the effort because you can initiate the process of building a living soil surface and develop the landscape more rapidly.

Figure 22.19. A sequence of fascines with jute matting restabilizes this gully until new vegetation becomes established. Brush on the surface discourages trampling.

You can use a similar method to improve drainage on short segments of a path or slope: simply place a log or fascine at a slight angle to deflect water off the path. These “water bars” can also be constructed entirely of soil or soil and stone, depending on site needs. Remember to use many shallowly placed diversions rather than fewer larger ones. The water bar is sometimes augmented with a small, shallow trench just upslope of the water bar to direct the runoff.

Check Logs

Where erosion is very limited and dispersed, you can use logs to check the flow of stormwater. Place lengths of long limbs and logs smaller than 3 inches in diameter along slope contours and stake them in place. Such “check logs” (Figures 22.20 and 22.21) are also an excellent way to dispose of woody debris in the landscape. Be careful not to create a channel by gradually concentrating the flow of water. The object is multiple redirectings and small impoundments to hold the water over the soil surface long enough for the maximum amount of infiltration to occur.

Figure 22.20. Check logs help retain small amounts of rainwater in the upper surface until ground litter can develop.

Figure 22.21. A check log along a former outlaw trail in Central Park. (Photo by Dennis BurtonlCentral Park Conservancy)

Replacing and Amending Soils

As a rule, the soil native to the site is preferred, for so many reasons, including cost, so you will want to preserve it wherever possible. The less disturbed the soil is, the less likely that any soil amendments will be needed, regardless of what conventional soil tests suggest. Where no major soil changes have occurred, except the loss of the upper horizons, you have an opportunity to make new soil and replenish damaged soils. The object of soil restoration is to mimic the natural soil of the site as closely as possible while minimizing the addition of outside inputs. Therefore, a basic requirement of soil restoration is not to consider adding any plants to the site that would require alterations to the native soil.

Most sites have a long history of uncontrolled erosion, so you will almost always need additional soil for restoration purposes. Importing large quantities of topsoil is not the best solution, however; it’s more costly than adding and mixing soil amendments and has serious local environmental impacts where it is excavated. When replacing soil lost to erosion, do not overlook chances to recover lost soil from the site. Soil may accumulate at the base of slopes and gullies and can be reharvested in some cases, especially for small patch repairs. To improve locally available soil, choose appropriate amendments, which may include woodchips, humus, leaf mold, compost, gravel, sand, and expanded slate, depending on the conditions you wish to re-create. In the most disturbed conditions, waste products, such as dredge spoil, may also be suitable.

Changing Soil Structure

In some cases you may wish to modify the soil structure during the restabilization process. In very extreme cases of compaction, for example, it may be advisable to modify the upper soil layers to minimize the likelihood of recurrence, such as adding sand. These measures, however, are generally more useful in turf areas intended for heavy traffic. In woodlands and natural areas, controlling off-trail use and other causes of compaction is almost always more appropriate than modifying soil. Always emulate native soils to the extent feasible.

Where the soil is excessively clayey or silty, the addition of coarse material can make the soil less prone to compaction as well as drought because water movement is restricted in heavy soil. One practice is to add sand, in proportions of 5 to 30 percent; however, it may also excessively drain the soil during periods of drought. Or you can add gravel, which is less prone to droughtiness in the soil.

Where both drainage and water-holding capacity need to be enhanced you can add small particles of stone, such as shale or slate, that have been sintered, or heat-treated, to make them porous. Because these stone products, called “expanded stone,” are permeable, they absorb moisture, up to 10 percent by volume or more. Although more costly than sand or gravel, expanded stone has the advantage of improving moisture retention. Today, fly ash, a waste material collected in smokestack scrubbers, is used in reclaiming soils. In fact, it is being heat-treated to improve its texture for use in reclaiming soils contaminated by a zinc smelter in Blue Lick, Pennsylvania. Densely porous ceramics are also now available and, though costly, have the advantage of being more uniform and easier to specify than sintered stone.

Another amendment is diatomaceous earth, composed of the skeletal remains of single-celled algae and nearly entirely silica, which has a very high surface area. It is used as a soil additive to improve moisture retention and to reduce compactibility to some extent. Diatomaceous earth is also easy to specify because it is more uniform than sintered shales and slates.

All of these amendments are suitable only for application in limited areas of heavy use in more urban, redeveloped landscapes and should not be widely used in natural areas. Diatomaceous earth is a known hazard to miners and should be handled with caution.

In sandy, gravelly, or rocky soils, excessive drainage, rather than poor drainage, may be the issue, especially where erosion has removed the more organic upper soil layers as well as the vegetation. Finer-grained material can be worked into the soil as well as organic matter to improve tilth and water retention. In general, however, deviate as little as possible from the native soil condition. The object is not to make all soils suitable for turf but to reestablish conditions as nearly as possible to those preceding the disturbance.

Adding Organic Matter

The addition of organic matter, probably the most common and trusted form of amendment, can make a great difference in the survival of new plantings. There are almost always a variety of local sources of organic matter that can be obtained at little or no cost. Many municipalities, for example, now operate compost programs for yard waste. In more remote areas, adding organic matter may be as simple as adding leaves that have accumulated nearby. But take care to exercise restraint in the use of organic matter. The increased fertility and added nitrogen may in turn restrict the natural germination and survival of indigenous plants in favor of invasives.

In many cases, you can eliminate the need to import nutrients or soil simply by using the site’s own resources more efficiently. Think in terms of how nutrients are or can be cycled on the site and emulate the historic patterns that are likely to be less wasteful. Keep all dead wood on site, for example, instead of carting it away. Do not collect leaves from a site. Reduce the losses of nutrients and topsoil through better stormwater management. Where soil is more impoverished and an organic amendment is desirable, consider using raw wood or woodchips as the primary additives and add raw leaves and a few twigs to mimic the natural forest floor and provide a thicker layer of litter.

Save organic amendments for those sites where only subsoils remain, such as sand and gravel pits. In places like these, organic matter is more crucial to recovery.

Powdered rock dust is used widely for agricultural crops and gardens as an alternative to synthetic mineral fertilizers. Rock phosphate is a means of adding phosphorus. Granite is high in potassium. Greensand or glauconite is high in iron, potassium, and silica. Used as a mineral amendment, powdered rock dust can be sprinkled on top of or worked into the soil where restabilization is undertaken.

Although information on the impacts of rock dust on soil food webs, for example, is inadequate, its use in forests merits further evaluation. Consider a surface application in the fall, rather than in the spring. Forest applications are not worked into the soil, which would damage roots. Use lower rates of applications, one-half to one-third, than are recommended for croplands.

pH Modifications

Unless the native pH of the soil has been altered there is probably no need to modify pH. If you use a commercial soil test, remember that the accompanying recommendations will be geared toward adding lime to raise pH because turf and most vegetables are favored by a circumneutral (neither acid nor alkaline) pH. Many native soils, including extensive areas of the Northeast, are naturally somewhat acid and therefore support acid-tolerant communities, which are negatively affected when the pH is raised. This problem is further clouded by atmospheric acid deposition in the Northeast, which has lowered the pH of many soils and led to calls for liming of forests. Adding lime to make nutrients more available, however, does not necessarily help restore historic conditions of ammonium- versus nitrate-dominated soils. To answer questions about pH modifications in woodlands, we need far more study and many more field trials.

The most common method for raising pH is to add ground limestone to the soil. Where pH has been artificially lowered or where a temporary increase in pH is desired to increase germination of some species, the rule of thumb is to use 80 pounds per 1,000 square feet, or one and a half tons of ground limestone per acre, to raise the pH one point. Use pelletized forms of limestone, which produce less dust than simple ground limestone.

Prescribed burning offers a more natural method to temporarily elevate and re-create the pH of surface soils suitable for the germination of some species. Soil covered by fresh ash is an ideal seedbed for many species, such as oaks, as well as a variety of other less-expected species. Where burning is not an option, you can mimic similar conditions by raking small plots intended for reseeding with a straw rake to expose patches of the soil surface and sprinkling a little lime, possibly mixed with sand. Create small patches only to minimize erosion and the overall extent of modifications.

Landscape maintenance typically centers more often on raising rather than lowering pH, but those interested in habitat restoration in the Northeast face conditions where pH has been artificially elevated. While many natural landscapes are becoming more acidic, more neutral conditions often prevail in urban areas and on former agricultural lands. Soil pH is often elevated by the presence of concrete and mortar rubble from construction or the addition of lime for crops. In these cases, it is usually advisable to reduce the pH to reestablish the more acidic, native soil conditions that favor indigenous species and reduce competition from exotics. Powdered sulfur can be used for this purpose, although its application requires protective gear. A pelletized version that is reasonably dust-free is now available and preferable to powdered sulfur. Acidifying fertilizers that are commonly used for azaleas and rhododendrons and other evergreens are also suitable for individual woody plants that require lower pH levels. A general rule of thumb is to add 7 pounds of sulfur per 1,000 square feet, or 300 pounds per acre, to lower the pH one point. Where there are established plants, lower the amount of sulfur used by half and apply sulfur in the dormant season. Restoring the natural, lower pH typically favors native species over many exotic invasives.

Aluminum sulfate is also used to lower pH, although greater volumes are necessary (50 pounds per 1,000 square feet, or 1 ton per acre) and the added aluminum may be a problem because it can be toxic to many plants at elevated levels.

Charcoal is a highly absorbent material that can effectively immobilize many problem materials present in the soil. It has a long history of use as a soil amendment to “sweeten” soil and as an alternative to fertilizer, but relatively few studies document its effects. Several studies show its effectiveness even in such extreme cases as soils contaminated by herbicide spills. In laboratory conditions charcoal is commonly used in media for cloning plants or germinating seeds to enhance the survival of delicate, early plantlets. Consider the use and evaluation of charcoal as a soil amendment where contamination is present. Activated charcoal, a more expensive material, is more effective than ordinary charcoal and may be warranted in more problematic circumstances. Like wood, charcoal and partially carbonized woody material, which is sometimes referred to as “torreyized wood,” appear to strongly stimulate soil fungal growth.

You can purchase fungi and other microorganisms for use in a wide array of extreme environmental conditions. They have proven enormously successful under the most degraded of conditions, such as strip-mine reclamation. New mycorrhizal products enter the market each year and may prove invaluable in the most drastically altered soils. Their role in habitat restoration may be more limited and should be evaluated carefully, however, since the widespread use of a single species or strain can have devastating effects on native diversity. If possible, obtain local strains. You may find what you need in your area. Now that the importance of microorganisms is more widely known, people are collecting and propagating local fungi in the same manner as they are collecting and propagating other native plants. Seek out a local mycologist and make every effort to develop indigenous communities of soil microflora. To learn more, try to attend a workshop on soil fungi.

Replacing Soil

Take care when refilling even a small amount of soil in an area where large roots have been uncovered by erosion for an extended period of time. If the root has been exposed long enough to form a protective layer of bark along its surface, the surface will rot if reburied. No soil should be added over exposed roots although the elevations of the soil can be restored between them.

When adding any new soil, be sure to scarify the surface of the subsoil for better adhesion. Where the potential for erosion will not increase, incorporate any new soil material well into the surface of the existing subsoil. When refilling over cribwork or fascines, or where the depth to be refilled is more than 4 inches, the first 4-inch layer should be lightly compacted before a second layer is placed. Each layer should be compacted to a density that is as close as possible to the adjacent undisturbed soil. Do not shortcut the process by applying a thicker layer all at once and trying to compact it from the top. It won’t work, and the fill will be less stable. Additions of greater amounts of soil will require professional advice and engineering assistance.

Do not be overly concerned about evening out the terrain. You are not seeding a lawn where a smooth surface is advantageous; you are trying to re-create more historic conditions, which once were a terrain of pit and mound. The need to work around roots and other plants will help create a microtopography that will become more pronounced with time.

Except in the flattest terrain, blanket the soil surface to protect the area from erosion. Woody plants take a long time to become established. New plantings are typically very small when installed under woodland conditions and suffer high rates of mortality. (See “Stabilizing the Surface,” later in this chapter, for more information.)

Repairing Compacted Soils

Where compaction has occurred, repair the site as quickly as possible or the compacted surface will continue to serve as a barrier to root growth, inhibit the exchange of atmospheric gases, and restrict the infiltration of water. In combination with airborne pollutants and hydrophobic substances, an impermeable surface crust is formed on compacted soil. When fill is added over compacted soil, the crust acts as an impermeable membrane preventing roots from growing upward into the new soil and leaving the site permanently less stable, unless and until the compaction is corrected.

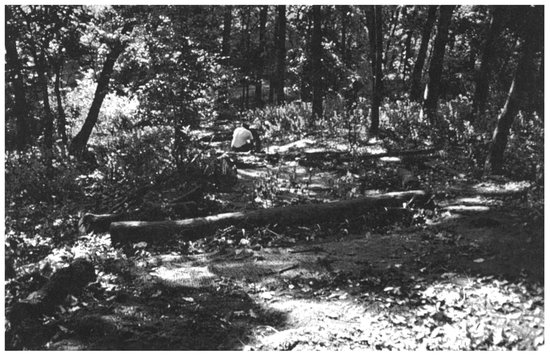

Hand Excavating to Correct Soil Compaction

Where complete replanting is anticipated, you can disrupt the soil surface more extensively than otherwise in order to decompact it. Work carefully, using hand rakes to avoid damaging tree roots that are alive below the zone of compaction. Try using mattocks where compaction is severe. There will be few, if any, living roots in this layer, so you are not likely to damage healthy roots if care is taken (Figure 22.22). Erosion, however, is a more difficult problem. Ironically, the soil may be quite stable when completely compacted, but as soon as it is loosened it is vulnerable to erosion and must be stabilized at the surface very quickly.

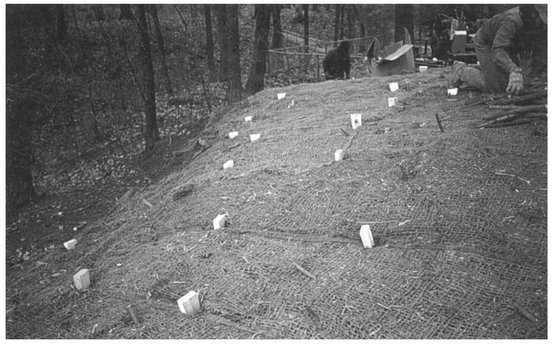

After the soil is loosened, add additional soil if necessary (Figure 22.23). You must then somewhat recompact the soil to restabilize the surface. Tamping by foot is adequate in most cases because the depth of loosening rarely exceeds a few inches. Then mulch with a thin layer of woodchips or raw leaves where woody cover is desired (Figure 22.24). Leave about 20 percent of the soil exposed. Depending on the extent of disturbance, a soil blanket, discussed later in the chapter, may also be necessary except in the flatter terrains (Figure 22.25).

Where compaction is locally extreme, an air gun is sometimes used to break up soils. It is reputed to minimize root damage under woodland conditions. The soil surface is, however, thoroughly disturbed, as it is with raking, and the process is very dusty. Protective gear is recommended.

Vertical Staking

Vertical staking (Figure 22.26) offers an alternative to thoroughly disturbing the upper soil to restore a compacted area and is especially appropriate where erosion is a serious threat and where vegetation should not be disturbed. Instead of loosening the entire surface area, try driving stakes made from cut branches vertically into the soil. Adjust the length of the cut branch depending on the depth of compaction and the amount of the stake you wish to leave above ground. This method loosens the ground at multiple sites to better convey water and air downward; at the same time it adds lignin to the soil.

In forested areas where raking or excavation could damage existing vegetation, vertical staking mimics the process of “piping” along the rotting roots of dead trees. After a tree dies, the decomposing roots leave long, continuous channels that are like pipes in the upper soil horizons, conveying water, nutrients, and gases vertically or laterally and serving to counteract compaction. Because only small areas are disturbed, numerous stakes can be driven into the ground around existing vegetation and no additional replanting is required for erosion control. In fact, the stakes themselves provide an added level of soil stability.

In a similar method, “vertical mulching,” 2-inch holes are drilled about 1 foot deep and then filled with composted woodchips. Vary the spacing of the holes based on the severity and extent of compaction and take care to avoid major tree roots.

Subsoiling

Where compaction is deep rather than at the surface and native plant communities are absent or reduced, the deep compacted layer can be broken with only minimal surface disturbance with a vibratory subsoil mole plow. This method damages existing trees and cannot be used in woodlands; however, in open landscapes where turf is being converted to meadow or where forest or a grassland is being enhanced to improve rainwater infiltration, it is very useful. Be sure to keep an adequate distance from the roots of existing woody plants, which extend, in many cases, beyond their canopies.

Figure 22.22. At the Richmond National Battlefield Park in Virginia, an unofficial trail had seriously compacted the ground. Workers used rakes and trowels to loosen the soil, taking care to leave exposed roots uncovered during the work process.

Figure 22.23. Loose soil gathered from the bottom of the slope was returned to the slope to reestablish the original grade, except where roots were exposed.

Figure 22.24. Raw leaves added as mulch enrich the soil and are anchored in place by soil blanket.

Figure 22.25. Jute extending up and down the slope in the direction of the flow of water was anchored with split wooden stakes at 4-foot intervals with 6 inches of overlap and stabilized the surface. This project was completed at a National Park Service training workshop under the direction of Robin B. Sotir and Associates of Marietta, Georgia.

Figure 22.26. Vertical stakes made from cut branches driven into compacted ground in a dense pattern convey water and moisture downward into the root zone and loosen the surface as they decompose, without disturbing surface stability.

Stabilizing the Surface

Surface stabilization in the forest presents a different range of concerns than those encountered in more open, sunny landscapes. Because quick seeding grasses do not persist in woodlands, conventional stabilization methods that rely on seeding do not work well, nor are they necessarily desirable under shady forest conditions. In forests it is the multilayered structure of trees and shrubs, as well as the herb and litter layers, that provides stability, not a dense carpet of herbaceous stems. The woody plants that are vital to forest stabilization may take several years or even decades, rather than months, to become established. Therefore mulch and a soil blanket, described later in this section, or some other surface protection are often required until a multilayered forest structure has developed.

The final mulch treatment to the soil is directed toward restoring fungi and other soil organisms. After the final grading and soil working are completed, spread on the soil surface a thin layer of woodchips, from 1/2 to 1 inch thick, to encourage the development of soil fungi. Scatter the woodchips, leaving about 20 percent of the ground uncovered, so that the soil remains bare and visible. This lignin-rich ground layer adds organic matter without enriching bacteria or earthworm populations. Fungi should develop rapidly. The thick, webby mat of growing mycelia adds structural support by adhering the mulch and soil particles together. Do not apply mulch to wet ground. Let the soil dry out beforehand, or you may encourage rotting of the newly installed plant material. Reapply mulch as necessary, but do not place a thick layer to save time later.

Where soils are especially sterile because of texture, such as waste piles or sites excavated deep into subsoil, for example, or damage from stockpiling, grading, contamination, or other causes, inoculating the soil with locally collected fungi may be advisable. You can colonize fungi from nearby landscapes with similar soils and vegetation that are less disturbed. The edges and less-disturbed areas of the site often offer good opportunities.

To prepare the transplants, place a layer of woodchips on the surface of the fungi-rich soil in small strips. The webby mycelia knit the woodchips into a delicate mat that can be harvested weeks later and moved to the more sterile site. Add raw leaves and a few twigs to mimic the natural forest floor and create a continuous litter-layer surface. Even simply adding a small amount of soil from a less-disturbed but analogous environment is an excellent way to introduce microorganisms. If the conditions are right, the fungi will spread rapidly from the inoculation area.

Please note, however, that you should not casually dispose of woodchips in a forest. Avoid using woodchips that might include treated wood. Chips from tree-of-heaven, walnut, and Norway and sycamore maples may inhibit growth through allelopathy. Where native communities are well established, any type of woodchip mulch can form a suppressive layer that inhibits herbaceous growth and the reproduction of many species. Where woodchips are used in a soil restabilization effort, a thick layer of mulch should be avoided for the same reason. Keep the layer thin and replenish periodically as necessary.

A soil blanket, also called an erosion blanket, provides additional protection for the soil surface on steep sites that are vulnerable to erosion or where runoff moves at high velocities. An erosion blanket is also useful where revegetation maybe hindered, such as in deep shade. The blanket treatment is not a cure-all that can be used everywhere and should be confined to those areas where remnant vegetation is minimal. Where existing vegetation is dense it will simply grow up under the blanket and dislodge it.

There has been a veritable explosion of soil blankets and other site stabilization fabrics. Here are several overall guidelines to assist you in choosing and installing appropriate material.

• Avoid products bound with netting, plastic, or fine string that can trap small animals.

The netting will break down with time, but it can have unacceptable impacts for a season or longer.

• Avoid nonbiodegradable materials that will not readily decompose, such as plastic or metal.

You can make a simple and effective blanket on-site that will hold up until new plants are adequately established by placing jute or coir matting over the woodchips. Where erosion potential is severe, erosion blankets made of coir, coconut husk fiber, provide a more durable and long-lasting surface protection than jute. Both are installed in the same manner, directly over the thin layer of woodchips. The matting comes in 6-foot-wide rolls and should be laid from the top to the bottom of the slope (rather than along the contour) with about 6 inches of overlap.

Secure the matting with wooden stakes at 3-foot intervals; do not use metal staples. You can make the stakes by splitting 12-to 18-inch-long two-by-fours diagonally to make two long wedges. Then cover the mat with leaves and light brush to disguise all traces of the repair work. Uncomposted leaves may be used on the ground surface as well as woodchips because the blanket secures them and does not allow slippage. These materials are readily obtainable and can be easily carried into the forest landscape; they’re light enough that equipment and vehicles are not needed.

Bonded fiber mulch, a cheaper alternative, may be useful in some severely disturbed forest applications. The mulch is made of gypsum mixed with wood fiber and sprayed onto the surface. It is relatively durable and does not tend to dry out as rapidly as cellulose fiber mulches. The gypsum breaks down with water, usually just as seedlings are developing. Its disadvantage is the vehicular access needed to bring in the required pneumatic sprayers used to install it; however, it may be useful on severely disturbed slopes bordering roadways, even in natural areas. The sprayers’ reach is about 300 feet. Although the potential effects of bonded fiber mulch on soil food webs are not known, this approach merits further investigation and trials on disturbed fringes of natural areas, since gypsum improves the structure of heavy clay soils and remediates some salt damage along roadsides.

More severe situations in which tensile materials and petroleum-based fibers are presumed to be necessary go beyond the scope of this guidebook. Before you decide to use them, however, consider that in many such situations, addressing comprehensive stormwater management would be far better than resorting to so artificial a solution.

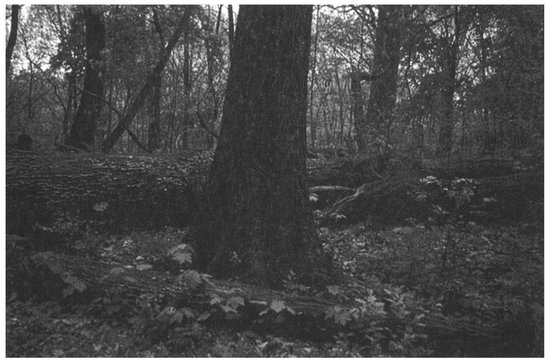

Managing Dead Wood and Brush

As a rule, individual dead trees should be left in the landscape as “snags” wherever possible. They are used as dens by many animal species and harbor insects and microorganisms that provide food for many other animal species. Woodpecker populations, for example, have increased dramatically in some places where gypsy moths have killed large numbers of oak trees.

A useful guideline is to leave at least three to five standing dead trees per acre for wildlife. Fallen logs and branches are also important to leave in place because they absorb and hold moisture like a sponge. Large logs are especially valuable to forest-floor creatures like salamanders. Two large and sound logs, in excess of 1 foot in diameter and 20 feet in length, and rotting logs, are recommended. Where logs are abundant, some can be moved to other locations where there is too little dead wood. The logs can also be along slopes placed to help control erosion. Partially submerged logs can be placed along shorelines to benefit fish, birds, and amphibious organisms. Logs in a stream both aerate water and provide additional habitat opportunities. Leaf litter and woody debris also can be reused elsewhere to add organic matter to eroded sites and to foster the restoration of important soil fungi and insects.

You can also use stumps, trunks, and limbs to construct checkdams, check logs, and soil stakes, as described earlier in this chapter. Where access is limited and chipping wood is not feasible, you can use the fine branches to build the litter layer. Brush may be temporarily effective in limiting access and discouraging trampling. When depositing brush on a slope to help control erosion, seek to create as natural an appearance as possible, mimicking the appearance of fallen limbs.

Figure 22.27. A brush pile oriented to receive some direct sunlight provides shelter for small creatures.

Figure 22.28. Logs laid on the ground disappear quickly and are excellent seedbeds for planting.

Figure 22.29. The ancient forest is filled with dead wood. Downed trees can be important assets for re-creating historic mixed-age, mixed-species forests.

A brush pile, if well sited with a sunny exposure, provides attractive and relatively safe shelter to wildlife in a small fragment of natural habitat, where small mammals and reptiles are often more visible and easily attacked. Such a shelter is also valuable in reducing mortality in winter and from vandalism. Brush piles also improve long-term soil quality and provide habitat for soil organisms.

To make a brush pile, select a sunny site, preferably away from human activity. Make the pile as compact as possible, placing logs at the bottom on the ground and laying larger limbs across the top to minimize wind damage.