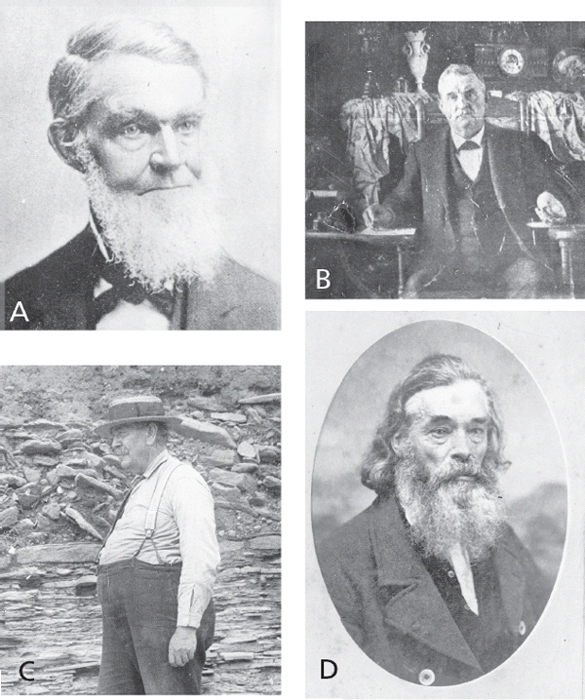

Figure 2.1. Members of the Cincinnati School of Paleontology who were amateur paleontologists: A. U. P. James, publisher and owner of the James Book Store. B. S. A. Miller, attorney. C. Charles Faber, realtor. D. C. B. Dyer, who, after he retired as a maker of soap and candles, devoted himself to fossil collecting. Photograph of Dyer from an old album in the possession of Richard Arnold Davis (© Richard Arnold Davis); all others from the Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati.

The rocks beneath and around Cincinnati were deposited in an interval of time universally called the Ordovician Period. This time unit was proposed formally in 1879. In the second half of the nineteenth century, beginning even before the Ordovician Period was named, there was in the region of Cincinnati, Ohio, a group of paleontologists who have been called the “Cincinnati School of Paleontology.” There is no single, definitive list of the members of the Cincinnati School, and different authors have included different people as members, depending on the purposes of their compilations. Nor is there a definitive list of iron-clad criteria as to who should be considered a member and who should not. Nonetheless, the individuals included in the body of this chapter have a number of characteristics in common.

First, they were all serious collectors of local fossils. But they went beyond that. They did not just amass hordes of fossils. They also assiduously studied their finds and where they found them. But they went beyond that, too. They shared their finds with one another, and they shared their information about fossils and their thinking about fossils not only within the local fossil-collecting community, but with the world as a whole, through publication.

A significant number of the members of the Cincinnati School produced lists of fossils, indices, bibliographies, and other compilatory works. But these are just one aspect of an essential criterion for inclusion in the Cincinnati School, namely, publication.

Second, there is a geographic component. Whether born in Cincinnati or not, individuals spent a significant portion of their lives, especially their formative years, in the type-Cincinnatian outcrop area. Moreover, all or most of their published work was published locally—in scientific journals or in books or other publications that were printed in the Cincinnati area.

Third, they all were amateurs, in the sense that finding and publishing about fossils was not how they made their livings. This criterion is a bit difficult to apply consistently, however, because some did sell fossils and some did sell books and other published matter. Moreover, a lucky few went from humble, amateur beginnings in the Cincinnati area to become respected members of the geologic and paleontologic profession as a whole. But even they began as local amateurs.

Fourth, there is a time-and-place component. The Cincinnati School of Paleontology was essentially a phenomenon of the period between the American Civil War and shortly after the succeeding turn of the century. All of the members were associated with the Cincinnati Society of Natural History during that period (and some, with the Western Academy of Natural Sciences that preceded the society). In present-day “buzz-word” terminology, they comprised a “learning community.” They worked together; they shared resources; they communicated with one another; they encouraged one another; they competed against one another. Above all, they stimulated one another to perform at a higher level than they otherwise might have done. The whole was more than the sum of its parts. There was true synergism in the Cincinnati School of Paleontology.

Although called a school, the Cincinnati School was not one, nor did it have any formal relationship with any college or university. (The University of Cincinnati, as such, was not founded until 1870, and there was no Department of Geology there until the first decade of the twentieth century, when the Department of Geology and Geography was initiated.)

But we need to put the Cincinnati School into more of an historical perspective. In the second decade of the nineteenth century, Cincinnati was the largest city west of the Alleghenies, and a local physician, Daniel Drake, figured that the city needed a first-class museum. Hence, he spearheaded the establishment of the Western Museum. As part of the preparations for the opening of the new museum, a taxidermist and artist named John James Audubon was hired and worked for the organization for about a year, before moving on eventually to become the most famous bird artist the United States has produced. In any case, the Western Museum opened in 1820.

Unfortunately, there was a depression in the 1820s, and the Western Museum fell upon hard times. To make matters worse, Dr. Drake had left the area. Although able to continue its operations, the Western Museum sank to being little more than a chamber of horrors.

Daniel Drake returned to the area in the 1830s. He still figured that the city needed a first-class museum, so he spearheaded the establishment of the Western Academy of Natural Sciences. By the time the ink was dry on the document signed at Appomattox Court House that ended the American Civil War, the Western Academy of Natural Sciences was moribund, and the Western Museum was little more than a collection of curiosities and a chamber of horrors.

In the late 1860s the cultural and civic leaders of Cincinnati figured that the city needed a first-class museum, and the Cincinnati Society of Natural History was established in 1870. About a year after the founding of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History, the handful of remaining members of the old Western Academy of Natural Sciences decided to transfer all the assets of the academy to the new society, including its money, specimens, and library. In return, the members of the academy were to be members of the society for life. Thus came into being the Cincinnati Society of Natural History that was a part of the lives of all the members of the Cincinnati School.

Here follows an account of each of those members. (In appendix 2 are briefer entries for other individuals who had connections with the type-Cincinnatian area, with its rocks and fossils, or with both. Some of these people occasionally have been referred to as members of the Cincinnati School.)

Figure 2.2 A. Cover of an 1849 publication of the Western Academy of Natural Sciences published by U. P. James, a member of the Cincinnati School of Paleontology, and his brother. B. Cover of the Cincinnati Quarterly Journal of Science, volume 1, number 1, published in January, 1874, by S. A. Miller, a member of the Cincinnati School of Paleontology. C. Cover of the Journal of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History, volume 1, number 1. D. Cover of The Paleontologist, Number 4, published in July 1879 by U. P. James, a member of the Cincinnati School of Paleontology.

Uriah Pierson James (Figure 2.1A) was born in the state of New York in 1811, the son of a carpenter. In 1831 he and his brother, Joseph, traveled to Cincinnati, where U. P. worked as a printer. By the end of the 1840s he was a publisher and the proprietor of the James Book Store. In the shop he always stocked the latest in geological books, and he displayed fossils in the windows.

U. P. James

U. P. James was very active in the intellectual life of Cincinnati. He served a term as president and was long-time treasurer of the Western Academy of Natural Sciences. When Charles Lyell, probably the foremost geologist in the world, visited Cincinnati in the 1840s, James was one of his hosts. About the same time, U. P. James became one of the charter members of the Cincinnati Astronomical Society (according to a list at the Cincinnati Observatory, February 11, 2007). He was one of the surviving members of the Western Academy when it was dissolved and its assets were donated to the Cincinnati Society of Natural History in 1872, whereupon he became a life member in the society.

Figure 2.3. A. Albert Gallatin Wetherby was professor of natural history at the University of Cincinnati before he relocated to Harvard University and malacology. B. George W. Harper, long-time principal of Woodward High School, where he facilitated the start of the careers of students Ray S. Bassler and John M. Nickles. C. “Friendly enemies”: left to right, August F. Foerste, Amadeus W. Grabau, and Edward O. Ulrich, during the International Geological Congress in Washington, D.C., 1934 (picture taken by Ray S. Bassler). Photograph of Wetherby courtesy of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University (© President and Fellows of Harvard College); that of Harper, courtesy of the Archives and Rare Books Library, University of Cincinnati; “Friendly enemies,” from the Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati.

Figure 2.4. Field work in the early days. A. John M. Nickles (left) and Ray S. Bassler, collecting from an exposure of the Kope Formation, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1900. B. E. O. Ulrich at the contact between the Kope and Point Pleasant Formations on the banks of the Ohio River below Covington, Kentucky, 1901. These exposures are now underwater. (A and B from Bassler Archive, Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., courtesy of JoAnn Sanner.)

Figure 2.5. Four Cincinnatians who became leading professional paleontologists. A. Charles Schuchert, Professor, Yale University. B. John M. Nickles, U. S. Geological Survey, 1942. C. Ray S. Bassler, U. S. National Museum. D. E. O. Ulrich, U. S. Geological Survey. (All photographs from the Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati.)

Figure 2.6. Urban outcrops in Cincinnati, where members of the Cincinnati School found their inspiration. A. The Bellevue House, on the site of the present Bellevue Hill Park, ca. 1895. The stratigraphic section exposed below begins in the Kope Formation, spans the entire Fairview Formation and Miamitown Shale (a small “step” below crest), and is topped by the Bellevue Limestone. Clifton Avenue runs below the exposure, which was designated as the type section of the Fairview Formation by Ford (1967). (Image courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society Library, Cincinnati Museum Center.) B. Exposure of Maysvillian strata (probably Corryville and Mt. Auburn Formations) at corner of Clifton Avenue and Calhoun Street (right), Cincinnati, 1900. Note, at left, trolley car and McMicken Hall of the University of Cincinnati. This exposure has been leveled and is presently the site of the University of Cincinnati College of Law. (From the Bassler Archive, Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., courtesy of JoAnn Sanner.)

U. P. James’s fossil collection was widely renowned. Louis Agassiz, one of the foremost paleontologists in this country, visited Cincinnati, and, after seeing James’s collection, proclaimed it one of the finest he had ever seen. James’s favorite fossils seem to have been bryozoans, which he considered to be corals. Many of the type-specimens in his collection ended up at the United States National Museum; other material went to the University of Chicago and to the University of Cincinnati.

Not only was James the author of many papers about local fossils, but he was the publisher of many others. Indeed, James was the publisher of the journal The Paleontologist (Figure 2.2), which ran for seven numbers, beginning in 1879. He also published a catalogue of Cincinnati freshwater mussels and another of local plants.

U. P. James retired from the bookstore business in 1886. He died in 1889 and was buried in Cincinnati’s beautiful Spring Grove Cemetery. (Becker 1938; Bradshaw, pers. comm.; Caster 1951, 1981, 1982; Croneis 1963; Cuffey, Davis, and Utgaard 2002; Hendrickson 1947; Howe, Fisher, and Keckeler 1889; J. F. James 1889; Shideler [1952] 2002; Anon. 1849, 1878.)

Joseph F. James

Joseph Francis James almost certainly was inducted into the wonders of fossil collecting by his father, U. P. James (above). However, Joseph’s interests in natural history were broader than were his father’s; the son published not only about fossils, but about physical geology, botany, and other subjects.

Joseph F. James began as a clerk in his father’s bookstore, but he became the first of the Cincinnati School to gain professional status. He was elected to membership in the Cincinnati Society of Natural History in 1876 (Cincinnati Society of Natural History, 94), and he long was associated with that institution as a member, officer, staff member, and author of papers in its journal. After a two-year stint in business pursuits in California and adjacent states, he was elected custodian of the society in 1881 and held that position for six years. The position of custodian involved a good deal more than janitorial work; it would appear that he was in charge of day-today operations of the society’s building. Meanwhile, he was also professor of medical botany at the Cincinnati College of Pharmacy.

In 1886 James was elected to the chair of Botany and Geology at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, “but this position was lost two years later through the disruption of the faculty arising from religious prejudices” (Gilbert 1898, 2). “When religious beliefs were under fire at Oxford, professor James was accused of being an agnostic and defended as being essentially a Unitarian. So far as I knew it, his religion was an unswerving devotion to science” (Gilbert 1898, 3).

For one year, he was professor of natural history at the Agricultural College of Maryland, during which time he also did work for the United States Geological Survey. Then, in 1889 James was appointed assistant paleontologist with the United States Geological Survey in the Division of Paleozoic Paleontology, in Washington, D.C. Two years later, he became assistant vegetable pathologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, also in Washington, D.C., and served in that position for four years. During those four years, James devoted his evenings to the study of medicine and graduated with a medical degree from Columbian University (now George Washington University) in 1895. He spent the winter of 1895–1896 in New York and London doing hospital work and bacteriological study, after which he set up in medical practice in Hingham, Massachusetts.

Joseph F. James was a prolific author, not only in paleontology, but also in geology and botany. Not counting many items in newspapers and magazines, his output amounted to well over one hundred scientific papers about equally spread among those three areas, along with a number of others on miscellaneous subjects. Some of his paleontologic papers were co-authored with his father, U. P. James. The younger James was the author or co-author of a number of taxa in the type-Cincinnatian, and at least one was named after him.

Joseph F. James died on March 29, 1897, in Hingham, Massachusetts, and his ashes were buried in Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery. (Becker 1938; Caster 1982; Croneis 1963; Cuffey, Davis, and Utgaard 2002; Gilbert 1898; Shideler [1952] 2002; Anon. 1879, 1882, 1885b, 1886a.)

C. B. Dyer

Charles Brian Dyer (Figure 2.1D) was born on April 1, 1806, near Dudley Castle, Worcestershire, England. Having had to support himself and his mother, he had little formal education, if any. He came to Cincinnati in 1828 and set up as a manufacturer of soap and candles. Around 1850, having made what he considered to be a sufficient sum, he retired and devoted himself to fossil collecting.

Dyer was one of the original members of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History, and he co-authored papers with S. A. Miller (see below). One of these was the report of a committee on the geological nomenclature of the type-Cincinnatian appointed by the society (S. A. Miller et al. 1879); of the ten members of that committee, six of the individuals are generally recognized as members of the Cincinnati School, and all of them have been listed in one place or another as collectors of local fossils.

However, it is for his avid collecting of fossils that C. B. Dyer is best remembered. As a young man, he enjoyed hunting, but upon retirement he abandoned the gun in favor of the hammer—and live game in favor of long-dead fossils. He was a well-known collector of fossils during his lifetime, to the extent that, in the 1870s, fossils from his collection were figured in publications of the Ohio and New York Geological Surveys and elsewhere (Hall 1872a, b; Meek 1872a, b, 1873). In 1880 his personal collection, which weighed more than 17,000 pounds (!), was sold to Harvard University for its Museum of Comparative Zoology. “The arrangements for this fortunate disposition of important scientific material apparently were made possible by Nathanial Southgate Shaler” (Croneis 1963, 82).

However, C. B. Dyer is not only known for his collecting activities in the local area. Around 1857 he became interested in the beds at Crawfordsville, Indiana, famous for Carboniferous crinoids, and he made extensive excavations there. He also traded Ordovician fossils from the Cincinnati region to the Hovey Museum at Wabash College, in Crawfordsville. The crinoid collection thereby assembled by Dyer was sold by him to the British Museum of Natural History, and it was the first large group of specimens from Crawfordsville to be sent abroad (Van Sant and Lane 1964).

Through his work with S. A. Miller, C. B. Dyer was involved in the naming of many taxa of local fossils, including annelid worms, bryozoans, snails, sponges, starfish and other echinoderms, trace fossils, and others. Moreover, at least one genus and twelve species of fossils were named after him, including the well-known species of crinoids originally designated Glyptocrinus dyeri Meek, 1872, now assigned to Pycnocrinus.

According to records at Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery, C. B. Dyer died on July 11, 1883, in Harrison, Ohio, near Cincinnati. (Becker 1938; Byrnes et al. 1883; Caster 1982; Croneis 1963; S. A. Miller and Dyer 1878a, 1878b; Raymond 1936; Sherborn 1940; Shideler [1952] 2002.)

S. A. Miller

Samuel Almond Miller (Figure 2.1B) is certainly the most important of the “amateurs” of the Cincinnati School. He was born near Athens, Ohio, in 1837. By profession he was a lawyer; he had studied at the Cincinnati Law College and was admitted to the bar in 1860.

S. A. Miller was also involved in publishing. In 1861–1862 he published the Marietta, Ohio, Republican, which, interestingly enough, was a Democratic newspaper. In 1874 and 1875, he was the proprietor of the Cincinnati Quarterly Journal of Science; many important papers on Cincinnatian fossils were published in that journal. After two years or so, Miller (and L. M. Hosea, who had become co-proprietor) ceased production of the journal after eight numbers had appeared. When the Cincinnati Society of Natural History commenced its own journal in 1878, it was rather similar to Miller’s defunct one. This is hardly surprising given that Miller had been a founding member of the society and had been campaigning for the society to publish its own journal (Anon. 1875). As an active member of the society, he served at various times as vice president, president, curator of paleontology, and an editor of their journal, in addition to presenting papers at their meetings. S. A. Miller was one of a committee of ten established by the society to consider the geological nomenclature of the type-Cincinnatian, and he was the first author of their report (S. A. Miller et al. 1879). As indicated in the section about C. B. Dyer above, six of the individuals on that committee are generally recognized as members of the Cincinnati School, and all of them have been listed in one place or another as collectors of local fossils.

Miller was active elsewhere in the community, too. He served on the local school board, ran for the U. S. Senate, and also for circuit court judge. He did not win his elections, however; it seems that he refused to take any contributions.

In 1882 Miller was considered for the position of Ohio state geologist, to succeed John Strong Newberry. (Edward Orton actually got the job.) Miller was awarded an honorary doctorate by Ohio University, where, years before, he had been a student for one year.

Miller produced a great many publications devoted to fossils, often co-authored with other Cincinnati-area collectors, such as C. B. Dyer and Charles Faber. Lael Bradshaw concluded that Miller named over 1000 taxa (Bradshaw, pers. comm.). But Miller is perhaps best known for his compilations of knowledge: The American Palaeozoic Fossils (1877), North American Mesozoic and Cenozoic Geology and Palaeontology (1881), and North American Geology and Palaeontology for the Use of Amateurs, Students, and Scientists (1889, with supplements in 1892 and 1897). The last volume listed, according to Kenneth Caster, is probably the most used volume about American paleontology ever compiled and certainly was the most ambitious private publication in paleontology ever.

Miller’s compilatory works were looked down upon by most professionals, but were used by them nonetheless. Caster recounted a story about his professor, G. D. Harris, to the effect that Harris’s own professor, Henry Shaler Williams, was disdainful of Miller’s works. In Caster’s words: “’Yet,’ said Harris, ‘Miller’s great North American Geology and Paleontology was always on Williams’ desk, and on the desk of every other paleontologist of the land!’” (Caster 1982, 24).

Nor did S. A. Miller confine his work to fossils from the Cincinnati region. He also worked on those of Illinois, Missouri, and Wisconsin. Miller’s fossil collection must have been fantastic; one newspaper account reported that it contained over a million specimens! According to Bradshaw, he rose early and worked on fossils until 10 am, then went to his law office until supper; after supper he worked a couple more hours on fossils.

This schedule must have taken its toll, for Caster recorded that Miller was addicted to drink. According to the late Walter Bucher, one-time professor in the Department of Geology at the University of Cincinnati: “Miller often cadged a quarter from an advocate across the hall to buy a shot of bourbon” (Caster 1982, 25). Caster used to give an expanded version of the story: when thirsty for a drink, Miller used to go to the lawyer’s office to borrow a quarter. The lawyer would take a type-specimen as collateral. The lawyer was supplied with money from the Walker Museum in Chicago. Miller lived long enough that every specimen marked “type” went to Chicago. Michael S. Chappars, curator at the University of Cincinnati Geology Museum in 1936, discovered that Miller had not marked all his types as such. Hence, the University of Cincinnati got about half of Miller’s types by accident (Caster 1982, pers. comm.). On the other hand, a 1912 letter from Ray S. Bassler to C. D. Walcott said that Miller “sold whenever impecunious to Gurley” (Sherborn 1940, 97); and Sherborn indicated that most of Miller’s types were at the University of Chicago in the collection of W. F. E. Gurley (with whom Miller had published a number of scientific papers).

S. A. Miller willed both his collection and his library to the University of Cincinnati. The library is intact, but is not easy to use because “. . . Miller had bound it into volumes, the only criterion of organization being enough papers of the same page-dimensions to make a conveniently sized volume. His interests ranged widely, and most volumes are highly eclectic” (Caster 1982, 26).

According to record 61331 at Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery, where he is buried, S. A. Miller died on December 18, 1897, of “cancer of liver and uraemic poisoning.” (Bradshaw, pers. comm.; Brandt and Davis 2007; Caster 1951, 1981, 1982, pers. comm.; Croneis 1963; Cuffey, Davis, and Utgaard 2002; Merrill 1924; Sherborn 1940; Anon. 1875, 1878.)

By now it has become obvious that a number of threads of our story are intricately intertwined. Various members of the Cincinnati School have tie-ins with the Cincinnati Society of Natural History, with the University of Cincinnati, or with both. Another thread in the skein is Woodward High School, as we shall see. But let us follow the University of Cincinnati thread for a bit.

A. G. Wetherby

Albert Gallatin Wetherby (Figure 2.3A) was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1833, but his family later moved to the Cleveland, Ohio, area. After graduating from college, he spent several years teaching in a country school, with summers spent farming. In 1861 he moved to Cincinnati and was appointed principal of Woodburn School, one of the public schools in the city, and spent some nine years there. In a eulogy written by George W. Harper, another member of the Cincinnati School, it is reported that Wetherby was appointed professor of natural history at the then new University of Cincinnati in 1870 and stayed there six years. However, according to the University of Cincinnati Record of Minutes No. 2, a volume in the archives of the University of Cincinnati, Wetherby’s time at the university began in the autumn of 1877, and he is listed as “Ass’t. Prof. A. G. Wetherby of Natural History.” In January of 1878 he was appointed “Curator of the Museum in the University,” and in March of that year, his title was changed to professor of natural history (Board of Directors, University of Cincinnati, 46, 65, 77, 80, 100, 117). Wetherby listed himself as “A.M., Professor of Geology and Zoology, University of Cincinnati” (Wetherby 1880, 1881). His last entry in the catalogues of the University of Cincinnati is for 1884–1885: “Albert Gallatin Wetherby, A.M., Professor of Natural History.”

Wetherby left the University of Cincinnati to pursue a career in business, first with the American and European Investment Company and, later, as a manager of some timber and mining lands of the Roan Mt. Steel and Iron Co. in North Carolina. He died on February 15, 1902, in Magnetic City, North Carolina.

Wetherby’s interests were many and varied. In addition to being a student of fossils, he was, at various times, curator of entomology and curator of conchology at the Cincinnati Society of Natural History. He co-authored with another member of the Cincinnati School, John Mickleborough, a list of type-Cincinnatian fossils (Mickleborough and Wetherby 1878a, b). He authored a number of other papers on fossils, especially, but not exclusively, echinoderms (Wetherby 1879a, 1879b, 1880, 1881). In the first-cited of those, he named the genus Enoploura, and interpreted the animals of that genus to be crustaceans. Wetherby’s failure to recognize that he was dealing not with crustaceans, but with echinoderms, brought down on him the wrath of Henry Woodward of the British Museum of Natural History. His contributions as a member of the Cincinnati School of Paleontology notwithstanding, most of Wetherby’s publications are not about paleontology, but rather about present-day molluscs.

Wetherby is one of many examples of the fact that the lives and careers of the members of the Cincinnati School were intertwined. For example, John M. Nickles studied under Wetherby at the University of Cincinnati, and George W. Harper wrote a eulogy about Wetherby. Wetherby was one of a committee of ten who wrote a report on the geological nomenclature of the type-Cincinnatian (S. A. Miller et al. 1879); six of the individuals on that committee are generally recognized as members of the Cincinnati School, and all of them have been listed in one place or another as collectors of local fossils. (Brandt and Davis 2007; Caster 1982; Harper 1902; Johnson 2002; S. A. Miller et al. 1879; Mickleborough and Wetherby 1878a, b; Nickles 1936; Wetherby 1879a, 1879b, 1880, 1881; Anon. 1876, 1878, 1879.)

John Mickleborough

John Mickleborough, Ph.D., was the principal of the Cincinnati Normal School from 1878 until 1885. This school was a part of the Cincinnati public school system that was dedicated to training teachers. The Cincinnati Board of Education suspended the operation of the Normal School in 1900, but that was a decade and a half after Dr. Mickleborough had departed Cincinnati for New York, where he became the principal of the Boys High School in Brooklyn.

Mickleborough had been nominated for membership in the Cincinnati Society of Natural History in July of 1876 (Cincinnati Society of Natural History, 90), and he became an active member of the society; for example, he served on the Publications Committee and as a member of a committee on the nomenclature of the rocks of the type-Cincinnatian that included five other individuals generally recognized as members of the Cincinnati School (S. A. Miller et al. 1879). And as noted above, in the section about A. G. Wetherby, Mickleborough and Wetherby co-authored an important list of type-Cincinnatian fossils (Mickleborough and Wetherby 1878a, b). But his most significant publication is his 1883 paper on trilobites, which includes a description of a specimen of Isotelus from the type-Cincinnatian with preserved appendages. Mickleborough was rather ahead of his times in his realization that the appendages of trilobites are similar to those of present-day chelicerate arthropods.

In addition to authoring publications on fossils, Dr. Mickleborough, as a professional educator, also wrote in the field of education, for example, on a method of teaching addition and subtraction in the primary grades that was promoted by John B. Peaslee, superintendent of schools in Cincinnati, and called by Peaslee “The Tens Method” and by Mickleborough “The Peaslee Method.” (Bassler 1947; Brandt and Davis 2007; Caster 1982; Lathrop 1900, 1902; Mickleborough 1883; Nickles 1936; Shotwell 1902; Venable 1894; Anon. 1886.)

Charles Faber

Although the caption of his photograph in the Department of Geology at the University of Cincinnati indicates that Charles Faber (Figure 2.1C) was a realtor, Kenneth Caster (1982) claimed that he was a manufacturer of leather belting. But both sources recognized him as a fossil collector. In the 1880s and 1890s his name appeared as an author of record, both alone and as a co-author with S. A. Miller. As such, he was involved in the naming of a number of taxa of fossils from the type-Cincinnatian.

According to the same photograph caption, Faber lived until 1930, late enough that Shideler went collecting with him. According to Shideler ([1952] 2002, 3), Faber was, “. . . like the typical old timer he was[,] very secretive and suspicious. He wasn’t telling anybody anything. It took me two years to get him softened up and educated so that he was willing to come out with his information. So we started going around to a number of the old secret localities where S. A. Miller got his types.”

Like most of the other members of the Cincinnati School, Faber was associated with the Cincinnati Society of Natural History. In fact, he was proposed for membership in the society in 1885, at the same time as Charles Schuchert and Ernst Vaupel, and he was duly elected.

Faber sold his original collection to the University of Chicago for $5000, according to Shideler, and it included specimens described by S. A. Miller. Being an inveterate fossil collector, however, he proceeded to amass a second collection. This one was bequeathed to the University of Cincinnati. The collection came with some money to provide for a curatorial position and for paleontological publications. The first holder of the curatorial position was Carroll Lane Fenton, who went on to write, along with his wife, what is arguably the best book of its time for amateur fossil collectors (Fenton and Fenton 1958). The late Kenneth E. Caster was also a well-known Faber curator. (Bassler 1947; Becker 1938; Caster 1982; Faber 1886, 1929; S. A. Miller and Faber 1892a, b, 1894a, b; Shideler [1952] 2002; Anon. 1885a, b.)

D. T. D. Dyche

Dr. Dyche, of Lebanon, Ohio, is one of the less well-known members of the Cincinnati School. He authored several papers on fossil crinoids of the type-Cincinnatian. In naming a species of conodont, Prioniodus dychei, U. P. James honored Dr. Dyche as one “who has done so much in collecting and developing so many of the finest Crinoids, etc., found in the Cincinnati Group . . .” (1884c, 147–148). There is, in the Warren County Historical Museum, in Lebanon, Ohio, what is labeled as the dental cabinet of David Tullis Durbin Dyche. We have not been able to verify whether D. T. D. Dyche, the member of the Cincinnati School, is the same person as David Tullis Durbin Dyche, the dentist. (Becker 1938; Dyche 1892a, b, c; U. P. James 1884c.)

E. O. Ulrich

Edward O. Ulrich (Figures 2.3C, 2.4B, 2.5D) was born February 1, 1857, in Cincinnati, but shortly thereafter the family moved to Covington, Kentucky, just across the Ohio River. The “O” stands for “Oscar,” but it was not a name given to him by his parents; Edward Ulrich gave himself that name after a hero in one of the stories he read as a boy. He seems to have been a sickly child, and was frequently absent from school. He was introduced to fossils by his minister, the Reverend Henry Herzer, when he was seven years old.

After quitting school, he was a surveyor for a couple of years and worked on the Eden Park Reservoir, which, to this day, supplies drinking water to downtown Cincinnati. He was a student at Baldwin-Wallace College for two years, but he did not finish college. During the 1876–1877 school year, he was a student in the Medical College of Ohio in Cincinnati, an independent institution at that time, but absorbed into the University of Cincinnati in 1915 (Broaddus, pers. comm.). Again, he did not finish work for a degree. Formal education and he did not get on too well, because “he insisted he was taught too much he didn’t want and too little that he did” (Bassler 1945, 333).

In 1876, Ulrich was elected to membership in the Cincinnati Society of Natural History. The following year he was elected curator of paleontology, an unpaid position. About that time the society acquired its own building, and, in the minutes of the society for the first meeting held in the new building on November 6, 1877 (Cincinnati Society of Natural History), it is recorded:

“The matter of appointing a janitor for the Building coming up, propositions were received from Messrs. E. O. Ulrich, Talbot, and J. C. Shorten.

“Professor Wetherby moved that the Society proceed to ballot for a janitor, the person elected to be subject to such rules as the Society may adopt, agreed to. The ballot resulted as follows: Mr. Ulrich received 28 votes. Mr. Shorten received 7 votes. Mr. Talbot received 3 votes and thereupon Mr. E. O. Ulrich was declared elected. Mr. Ulrich’s proposition is as follows,

Cincinnati Nov. 6th 1877

To the Cincinnati Society of Natural History

The undersigned is an applicant for the position of Janitor or Custodian of the Society’s building; am willing to devote my entire time to the interests of the Society, for the consideration of $300.00 per annum, and the Society to allow me one room for a sleeping apartment.

Respectfully yours,

E. O. Ulrich

Ulrich’s association with the Cincinnati Society of Natural History brought him into contact with U. P. James, Joseph F. James, Charles B. Dyer, S. A. Miller, and other members of the Cincinnati School. For example, Ulrich was one of six members of the Cincinnati School who served on a committee on the nomenclature of the rocks of the type-Cincinnatian (S. A. Miller et al. 1879). Nor did his contacts come only with Cincinnati folk. For example, as early as 1886, Ulrich went collecting with August F. Foerste, who went on to become one of the foremost workers on fossil cephalopods in the United States. Although the position at the society was called “custodian,” Ulrich apparently was in charge of day-to-day operations at their facility.

In addition to the labors associated with that job, and later on, Ulrich worked at various times as a carpenter, for various state geological surveys, and part-time for the United States Geological Survey in Tennessee. One of his main sources of income, however, was the production of thin-sections of bryozoans, which he sold to buyers both in the United States and Europe. In order to collect sufficient specimens and make thin-sections from them, Ulrich employed other local aficionados of fossils, including Bassler, Nickles, and Schuchert. (Kenneth Caster [1982] has credited Ulrich with the trait of enlisting the assistance of local youths, thereby changing their lives. This calls up the image of the kindly old man helping the local kids; it happens, though, that two of Ulrich’s three best-known protégés, Schuchert and Nickles, were only one and two years younger than Ulrich, respectively.)

In 1897, Ulrich was hired permanently by the United States Geological Survey and stayed there for the rest of his career, eventually becoming the head of the stratigraphic section, and in effect the arbiter of stratigraphic decisions in the country. Although specimens and thin-sections provided by Ulrich are present in many institutions all across the land, his personal collection went mainly to the United States Geological Survey and thence the United States National Museum. Ulrich officially retired in 1932, but continued scholarly work as an honorary associate in paleontology at the Smithsonian Institution.

Ulrich authored or co-authored many taxa of animals of all kinds. One of these was a species of ostracod crustacean named after the man of the cloth who had introduced him to fossils. Ulrich wrote: “I name it after Rev. H. Herzer, now of Berea, O., who was the first to awaken in me the latent love for nature that has since grown almost to a passion, and become an inexhaustible source of keenest enjoyment” (Ulrich 1891, 209).

Ulrich received many honors. Baldwin-Wallace College, which he had attended for a time, awarded him both an honorary master’s degree and an honorary doctoral degree in 1886 and 1892, respectively. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and was awarded their Mary Clark Thompson Medal. He was elected president of the Paleontological Society for the year 1915; this society was then and is now the premier professional paleontological organization in the United States. In 1932, Ulrich was awarded the Penrose Medal of the Geological Society of America, the highest honor to which a geologist may aspire.

On the other hand, Ulrich seems to have been involved in some less-than-honorable activities. The most surprising is that he backed an attempt to prevent the election of Charles Schuchert to the presidency of the Geological Society of America, despite the fact that Schuchert had been a protégé and colleague of Ulrich from the old Cincinnati days. The proximate cause for this was that Ulrich had proposed recognition of two major chunks of rock between the Cambrian and the Ordovician Systems, the Ozarkian and Canadian. However, Schuchert did not enthusiastically adopt the Ozarkian and the Canadian Systems in the prestigious textbook on historical geology of which he was co-author. There also was a dispute as to whether Ulrich or Schuchert had “invented” the paleogeographic map (neither had, but it certainly was Schuchert who made them famous).

The ultimate cause, however, was the fact that Ulrich was extraordinarily knowledgeable on all things stratigraphic and paleontologic. From childhood, he had had an uncanny memory. Kenneth Caster (pers. comm.) claimed that, decades after visiting a locality, Ulrich could recall the stratigraphic section there inch by inch, with great accuracy and precision, along with its fossil contents. Thus, Ulrich was supremely self-confident. In discussions, he “to put it mildly, made his position clear.” He “was in congenital disagreement until the day of his death on Washington’s Birthday, 1944” (Croneis 1963, 85). However, one should not conjure up a picture of a grumpy old man. Ulrich was known for his genial disposition, and, indeed, was known as “Uncle Happy.” (As it turned out, Ulrich’s “new” systems never did gain widespread acceptance, but in the meantime, Schuchert did get elected.)

Ulrich was an early worker on Paleozoic ostracodes and conodonts. He is especially well known for his work with bryozoans, having been one of the pioneers in the use of thin-sections to understand the animals. However, his extensive record of publications includes scientific papers on representatives of almost every major group of invertebrates; not only the ones mentioned above, but also, annelid worms, brachiopods, molluscs, sponges, and trilobites. (Bassler 1945; Becker 1938; Bradshaw 1989; Brandt and Davis 2007; Byers 2001; Caster 1951, 1981, 1982; Croneis 1963; Cuffey, Davis, and Utgaard 2002; Merrill 1924; Sherborn 1940; Shideler [1952] 2002; Ulrich 1891. Ulrich’s personal bibliography is immense; a good place to start a search for his works is Bassler 1945.)

Charles Schuchert

Charles Schuchert (Figure 2.5A) was born in 1858, the son of a cabinet maker; the family was poor, and Karl (as he was christened) spent his life well into his twenties trying to keep body and soul together. He attended school through the sixth grade, then, at age twelve, went to a mercantile school to learn bookkeeping, at which point he began to work at his father’s furniture factory. However, the factory burned down in 1877; Charles revived the enterprise, but it burned again in 1884. Meanwhile, Schuchert did take some drawing courses at the Ohio Mechanics Institute in Cincinnati, and he mastered lithography.

Schuchert’s introduction to fossils came in 1866, when a laborer working near the Schuchert home tossed the eight-year-old lad a fossil that had come out of the excavation. Some time thereafter, Schuchert’s father took him to see the roomful of fossils owned by one William Foster—”which opened to me an unknown world” (Becker 1938, 193). The boy was completely hooked. Then, at about age seventeen, Schuchert saw the fossils in the windows of the establishment of U. P. James. They met, and the elder James used some of the young man’s fossils in his published work. Schuchert also heard about C. B. Dyer’s collection and sought out his acquaintance. In 1877, he met Ulrich, “who was to turn me from an amateur into a professional paleontologist” (Becker 1938, 193).

As a serious amateur fossil collector, and as one trained in lithography, Schuchert was hired by Ulrich as the ideal assistant for preparing lithographs for the Illinois and Minnesota geological surveys. This was 1885 through 1888.

In that last year, James Hall, the dean of American paleontologists, visited Cincinnati and was so impressed by Schuchert’s collection that he hired him to become an assistant for the New York Geological Survey (and, incidentally, obtained his collection of fossils). In 1893, Schuchert joined the United States Geological Survey, and, a year later, he went to the United States National Museum, also in Washington, D.C. Eventually, he came to occupy the most prestigious geological professorship in North America, that at Yale University.

Schuchert began attending meetings of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History in 1878. However, it was not until 1885, after he had left the furniture business for good, that he formally was proposed as a member. As it happens, Charles Faber, Ernst Vaupel, and Schuchert all were nominated at the same time.

Schuchert was born in Cincinnati, but in some respects it is not fair to call him a member of the Cincinnati School, because he did not really publish anything locally. He had 234 scientific publications, but none appeared in the local journals. Although he did not invent the paleogeographic map, he brought it to its mature state. And, up until the time of his death, in 1942, he was also the foremost authority on fossil brachiopods of North America.

Like some other members of the Cincinnati School, Schuchert was honored during his lifetime. He was awarded an honorary master’s degree by Yale University in 1904, and honorary doctorates were awarded him by New York, Harvard, and Yale Universities. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and was elected president both of the Paleontological Society and of the Geological Society of America. Like Ulrich before him, Schuchert was awarded the prestigious Penrose Medal of the Geological Society of America in 1934. Moreover, one of the medals awarded by the Paleontological Society bears his name. Not bad for a kid who never made it to high school! (Bassler 1945; Becker 1938; Brandt and Davis 2007; Byers 2001; Caster 1951, 1981, 1982; Clark 1943; Croneis 1963; Cuffey, Davis, and Utgaard 2002; Dunbar 1943; Kaesler 1987; Knopf 1952; Shideler [1952] 2002; Twenhofel 1942; Yochelson 1973, 1975; Anon. 1885a.)

John M. Nickles

John Milton Nickles (Figures 2.4A, 2.5B), on the other hand, clearly was a member of the Cincinnati School. Indeed, he was the first of the Cincinnati School actually associated with the University of Cincinnati; he received a bachelor’s degree in 1882 and a master’s degree in 1891. While at the university, he studied geology under A. G. Wetherby.

He had attended Woodward High School, in Cincinnati, and had been encouraged in his geological interests by George W. Harper, the principal, and by a fellow student. “My boyhood companion, Ernst H. Vaupel, inducted me into collecting fossils during my second year at Woodward High School. Previously we had together collected snail shells and fresh water mussels from the Ohio River at low water and then ‘deer horns’ (worn cyathophylloid corals) from the drift material fill of the Marietta and Cincinnati Railroad (now B & O) made through Mill Creek valley” (Nickles 1936).

By the time he graduated from high school in 1878, he had started a bibliographic work on the local bryozoans, and he already was acquainted personally with Ulrich and Schuchert. After stints of teaching in Arkansas and then Illinois, where he was a high school principal, he returned to Cincinnati, although for a number of summers he had spent vacations with Ulrich collecting bryozoans all over central and eastern North America.

In 1899 Nickles met Ray S. Bassler at the residence of E. O. Ulrich in Newport, Kentucky. Nickles and Bassler collaborated to produce United States Geological Survey Bulletin 173—Synopsis of American Fossil Bryozoa (Nickles and Bassler 1900). About the same time, Josua Lindahl, the director of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History and former state geologist of Illinois, asked Nickles to prepare a paper on the geology of Cincinnati; this was published in the society’s journal in 1902 and is used to this day. In the summer of 1909, Nickles prepared a manuscript geologic map of the West Cincinnati Quadrangle for the proposed Cincinnati Folio of the United States Geological Survey; this has yet to be published.

In 1903 Nickles was appointed to the United States Geological Survey in Washington, D.C., apparently on the strength of the bryozoan bibliography that had appeared in 1900; of course, his friendship with Ulrich did not hurt. Until his death in 1945, he devoted himself to compiling bibliographies, including the Bibliography of North American Geology, the Annotated Bibliography of Economic Geology, and the Bibliography and Index of Geology Exclusive of North America, which were published over a number of years. In all, his contribution to these amounted to thirty-eight volumes, comprising a total of 14,361 pages—a fantastic accomplishment! (And it all was done “the old-fashioned way”—there were no computers in that far-distant day and age!)

Nickles authored a respectable pile of publications on bryozoans, but he deliberately sacrificed the paleontological reputation that would have been his in order to serve the science of geology in the thankless task of compiling the bibliographies, and it is for his bibliographies that the geological community forever will be indebted to him. (Bassler 1947; Brandt and Davis 2007; Caster 1951, 1981, 1982; Croneis 1963; Cuffey, Davis, and Utgaard 2002; Nickles 1902, 1936.)

George W. Harper

George W. Harper (Figure 2.3B) was a brilliant pedagogue and amateur geologist. Actually, calling him a geologist is too narrow an assessment, for he was, at one time, the curator of entomology at the Cincinnati Society of Natural History and, at another, curator of meteorology, and his name is associated with the study of freshwater mussels in the Cincinnati area.

Harper was born in Franklin, Ohio, in 1832, but spent the vast majority of his life in Cincinnati. He graduated from Woodward College, in Cincinnati, in 1853, valedictorian of his class, and began teaching at Woodward. He was principal of Woodward High School from 1865 through 1900. Somewhere along the line he was awarded a master’s degree from Denison College (now, Denison University) and a doctorate from Princeton University. In 1873, when the University of Cincinnati was still new, he assisted in organizing classes and in putting the institution in order; in fact, he is counted as an interim president of the university (Grace and Hand 1995, 139). Moreover, he served on the board and as president of the College of Medicine and Surgery of the university for a number of years.

Harper was elected to membership of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History in 1871 (Cincinnati Society of Natural History, 20). His association with the society was long and extensive. At various times he served as curator, librarian, member of the publishing committee, vice president, and president. Moreover, he served as a member of the committee on the nomenclature of the rocks of the type-Cincinnatian chaired by another member of the Cincinnati School and including four others (S. A. Miller et al. 1879).

Woodward High School, in Cincinnati, was headed by “kindly principal George W. Harper, a geologist in his own right, whose particular desire in life was to train students of geology” (Bassler 1947, iv). For example, he facilitated the progress of John M. Nickles and Ray S. Bassler by allowing them to re-arrange their schedules at the school so as to be able to work with Ulrich in paleontologic endeavors. Moreover, in 1896, he co-authored a paleontological paper with Bassler, then a high school senior (Harper and Bassler 1896). George W. Harper died in 1918. (Bassler 1947; Caster 1965, 1982; Cuffey, Davis, and Utgaard 2002; Dury 1910; Harper 1886, 1902; Johnson 2002; Kramer 1918; Martin 1900; Anon. 1876, 1878, 1885b, 1886a, b.)

Ray S. Bassler

Raymond Bassler (Figures 2.4A, 2.5C), as he was christened, was born in Philadelphia in 1878. At the age of two he moved to Cincinnati with his family. His father, Simon Stein Bassler (that is, Sgt. S. S. Bassler, of the U.S. Army Signal Corps), was one of the founders of the United States Weather Bureau.

Although a handwritten card in the archives of the University of Cincinnati gives his full name as “Raymond Smith Bassler,” he assumed the professional form of his name after having made acquaintance with the scientific works of John Ray and E. Ray Lankester, and, thereafter, he signed himself as “Ray S. Bassler” (Caster 1965, P167).

Bassler attended Woodward High School, where George W. Harper was principal. During his freshman year, he met Ulrich and became his technical assistant. Bassler was free to work for Ulrich in the afternoons, because Harper allowed him to compress his classes into the mornings. As previously noted, while only a high school senior, Bassler co-authored a paleontological paper with Harper in 1896.

In 1896 Bassler entered the University of Cincinnati, which had no geology department at the time. Bassler continued working with Ulrich, however. This work was invaluable experience; as Bassler said, “The thin-sections of Paleozoic Bryozoa prepared the hard way during our eight years association were equivalent to several college courses at least, and the time was not otherwise lost, for over a thousand slides were left for future publications” (Caster 1965, P168).

Bassler spent considerable time at the facilities of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History. The late Ellis Yochelson related a story told to him by Bassler that the young man was alone in the building one day when a gentleman with a brilliant white beard showed up and asked to be shown around the place. Bassler did so, and, afterwards, the bearded visitor departed on his way back to Albany, New York. Thus, Bassler met James Hall (1811–1898), perhaps the foremost paleontologist in the country (Yochelson, pers. comm.).

Ulrich left the Cincinnati area for Washington, D.C., in 1900, and Bassler followed in March of 1901, withdrawing from the University of Cincinnati, before completing his senior year.

Bassler worked privately for Ulrich and went to school part-time at Columbian University (now George Washington University); he was able to transfer credits back to the University of Cincinnati and was awarded a bachelor’s degree in June of 1902. About that same time, Bassler began working for the United States National Museum (where Charles Schuchert was his immediate supervisor). This association with the National Museum lasted for nearly six decades, as Bassler rose through the ranks to become head curator of geology in 1929. After his retirement, in 1948, he continued as an honorary research associate until his death in 1961. Meanwhile, he earned his master’s and doctoral degrees at George Washington University, in 1903 and 1905, respectively; thereafter he was associated with the university for the next thirty-eight years, including service as professor and head of the Geology Department.

Bassler must have had a sense of humor. Kenneth Caster passed on a story he had heard from Bassler: As a professor in Washington, D.C., Bassler used to take classes to the zoo. One day he was leading such a group, and he noticed that an elderly lady, who seemed slightly familiar, was trailing along after the group. In any case, he stopped by a boulder of Pre-Cambrian rock on the zoo grounds and informed his students that the rock was one billion years old. At this point, the elderly lady interrupted: “But, Professor Bassler, I believe that you have made a mistake. It happens that I was here last year when you brought your students. At that time you said that the rock was a billion years old. So, this year, it must be a billion and one” (Caster, pers. comm.).

During the summer of 1909 Bassler did a manuscript geological map of the East Cincinnati Quadrangle for the proposed Cincinnati Folio of the United States Geological Survey. This map was never published.

During his life, Bassler was an author of over 200 papers, many of which were lengthy works. He was the foremost expert on Paleozoic bryozoans and was one of the pioneers in Paleozoic ostracodes and in conodonts, thereby encouraging the development of micropaleontology. It was Bassler’s timely completion of the bryozoan volume of the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology that allowed that project to get off the ground, which might not have happened without the appearance of Bassler’s volume (Bassler 1953). Among his most valuable works is a bibliography and index of American fossils from the Ordovician and Silurian (Bassler 1915).

Kenneth Caster used to call a 10× hand-lens a “Bassleroscope” (Caster, pers. comm.). According to Caster, Bassler refused to use a compound microscope; hence, his understanding of fossils was arrived at without the benefit of higher magnification (Caster 1965, 1981). If that were true at one time, Bassler must have seen the light, at least with respect to bryozoans: “. . . we can not be sure of the position of any form in the scheme of classification until we have learned its internal structure by means of thin sections examined microscopically” (Nickles and Bassler 1900, 9). Moreover, according to Ellis Yochelson, Bassler had a compound microscope on his desk, and it appears in photographs Yochelson had seen (Yochelson, pers. comm.).

Bassler was recognized for his great accomplishments during his lifetime. He was elected secretary of the Paleontological Society and served in that position from 1910 to 1931, and then he became president of the society. In 1933, he was president of the Geological Society of America.

When Ray S. Bassler died in 1961, the Cincinnati School of Paleontology was no more—except in their vast numbers of fossils in museums around the world and in their publications in libraries. He was the last survivor. (Bassler 1933; Becker 1938; Brandt and Davis 2007; Caster 1965, 1981; Croneis 1963; Harper and Bassler 1896; Nickles 1936; Nickles and Bassler 1900; Shideler [1952] 2002.)

The Cincinnati School in Retrospect

Although a number of the members of the Cincinnati School of Paleontology did serve stints as school principals in real life, the Cincinnati School had no classrooms, nor did it offer courses. It did not even have a football team! Nonetheless, its members definitely made the grade. This is so despite the fact that, to the majority of the Cincinnati School, paleontology was not a profession, but rather an avocation. To call these individuals “amateurs” is at once true and unfair. Although they did not make their livings as paleontologists, their published works have held up as well as much of what was authored by the actual “professionals” of the day. Moreover, some of the members of the Cincinnati School did, in fact, go on to become amongst the leading “professionals” of their time.

It is primarily through the efforts of the Cincinnati School of Paleontology that the Cincinnati area is truly world famous for its fossils. It was due to their work that the Cincinnati region is the North American standard for the span of geologic time during which its rocks were deposited and the organisms that were to become its fossils lived.

However, it was not only the members of the Cincinnati School who have worked on the rocks and fossils of the type-Cincinnatian. There were, and continue to be, a great many others involved. In appendix 2 of this book, we have compiled brief biographies of some of these other individuals and of institutions associated with the study of the geology and paleontology of the Cincinnati region.