2

Algorithms of Aspiration

A street vendor in Chiang Mai, Thailand, caught the internet’s imagination with her creative way of attracting customers. The twenty-three-year-old figured out the attention metrics, wore nothing underneath her cardigan, and got online to sell khanom Tokyo, a popular street snack.1 Posts on her Facebook page got tens of thousands of comments and shares, and the tactic boosted her sales. Morality aside, this was calculated creativity.

When the media speaks of the “creative class,” a concept pioneered by urban studies scholar Richard Florida almost two decades ago, it portrays young, latte-sipping creative entrepreneurs and hipsters in global cities like New York and Amsterdam.2 Few outlets cover people at the margins in the Global South—second- and third-tier cities—hours away from the global metropolises where a majority of the world’s young people reside. It is no wonder that there is cognitive dissonance in picturing future digital creatives being born out of poverty porn.

Global data trends say otherwise. A 2021 survey by Hootsuite and We Are Social, respected Silicon Valley creative agencies, suggests that “the ‘next big trend’ in digital won’t emerge from a Western market.”3 The creator economy, fifty million strong, is a powerful manifestation of how young people are taking control of their self-expression, learning, social networks, and livelihoods.4 Youth in the Global South are particularly determined to be at the forefront in shaping the digital future, as they cannot afford to sit and wait for their freedoms and future work opportunities. A majority of young people live with crippling pressures to conform to patriarchal and authoritarian rules. Social norms dictate how they present themselves online, what they wear and share, who they tag, where they check in, and what they say. These online behaviors can have harmful implications from sexual harassment and trolling to imprisonment and bodily violence.

Navigating such suffocating digital and social spaces demands extraordinary and everyday creativity. Youth at the margins are constantly at work to figure out how to game the public gaze, navigate censorship, and use the algorithms to feed their self-expression while remaining outwardly compliant. Taboos are tempting, especially those that suppress natural teen desires such as sexuality and romance. Youth have little choice but to be online entrepreneurs as governments fail to provide them with gainful employment. Creativity is not the prerogative of the privileged. Youth at the margins are a formidable force in driving digital creativity with their unmet aspirations. Everyday online creative acts can be found in their digital work and play, joy, informal learning, and efforts to build identities and solidarities, if we only stop and look.

Imitator Nations

Former Hewlett Packard CEO Carly Fiorina described China as an imitator nation in her interview with Time in 2015:

I have been doing business in China for decades, and I will tell you that yeah, the Chinese can take a test, but what they can’t do is innovate. . . . They are not terribly imaginative. They’re not entrepreneurial, they don’t innovate, that is why they are stealing our intellectual property.5

Fast forward to 2023, where little, yet everything, has changed. While the US Financial Times covers Chinese corporate espionage, China Daily touts its nation’s global innovation. The Financial Times reached out to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to learn how much of a nemesis China has become to the United States by stealing trade secrets, pirating software, and counterfeiting to the tune of $225–600 billion a year.6 China Daily counters this framing by arguing that China is a hub of global innovation. The Chinese media reminds the world that in 2018, China entered the global innovation index rankings of the top twenty most innovative countries in the world.

China’s list of achievements is impressive. It pioneered the world’s first quantum-enabled satellite, the world’s fastest supercomputer, the world’s largest and fastest radio telescope, the world’s first solar-powered expressway, the world’s largest floating solar-power plant, and the world’s thinnest keyboard.7 China Daily concludes confidently, “No matter how much the country’s creativity may differ from the West, China will lead the world as a global leader in science and technology by 2030.”8

We are witnessing a creativity turn in the Global South as Indigenous innovators are looking at their people as creative assets, legitimate markets, and content partners to help build their data products and services. Yet the imitator label remains a sticky factor that translates to few creative industries in the West tapping into these global shifts.

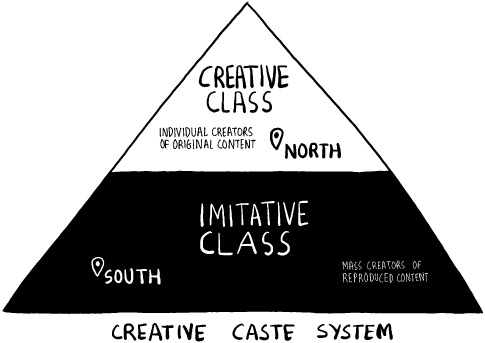

Creative Caste

Silicon Valley remains slow to recognize the geopolitical shifts in the creator economy. Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen explains how the West suffers from a “cultural captivity” syndrome, where a theory is born from the “accidental correlation between cultural prejudice and social observation.”9 Sen talks about the stickiness of how we imagine entire groups even when correlations die.

I call it the creative caste system, in which certain groups are believed to have an intrinsic ability to create original thought and content while others do not. Groups are marked by the nation and the context they happened to be born into. People’s gender, caste, race, and economic status play a part in how they are perceived on the creative spectrum, and the poverty stigma, in particular, runs deep. It is still a challenge for Big Tech to view low-income users as consumers, let alone as creators.10

In 2022 I gave a keynote on the next billion creatives to UX researchers from the usual suspects like Meta, Google, Amazon, Spotify, and other North American tech firms. After my talk several e-commerce strategists approached me to explore the potential of live streaming for the Global South. This Western awakening is happening among consultancy firms such as McKinsey Digital, too. It released an article in 2021 titled “It’s Showtime! How Live Commerce Is Transforming the Shopping Experience.”11 The gist of the article is to convince Western businesses to blend entertainment with purchasing by using live streaming for e-commerce. While Western tech is waking up to this supposedly novel opportunity, in China, this is old news. China’s creator economy is now a mature ecosystem with a market size of $20 billion in 2021. China is already home to the world’s biggest live-commerce player, Taobao, with a market share of 35 percent.12 By 2020, almost 30 percent of Chinese internet users shopped via live streaming. Chinese apps realized years ago that content creators need to be able to monetize their talents and fanbases, or they would look elsewhere to set up home. US tech still grapples with interoperability and content monetization.

While Silicon Valley is still harping on blockchain and the nebulous Web 3.0, India has gone ahead and set up the Unified Payment Interface (UPI). UPI is the Indian government’s digital public infrastructure allowing instant payments in peer-to-peer and customer-merchant networks. While crypto lords in the West battle each other over who will reign supreme, India has set up an easy-to-use, low-cost marketplace to help boost the creator economy and get the market working again. UPI has been so effective that Google has nudged the United States Department of the Treasury to consider it as a best practice while they design standards for open payment systems.13 Tech business analysts Vivek Wadhwa, Ismail Amla, and Alex Salkever argue that we should not be swept away by the “cool” factor of new tech like blockchain. Instead, the real revolution of tech tools lies in the “less flashy efforts” of open standards and interoperability, where India is way ahead of the game.14

More examples abound. Latin America is a driving force in e-sports and mobile game apps.15 African entrepreneurs are pioneering “data-lite” mobile apps to cater to their cost-conscious and mobile-first clientele.16 As the world’s eyes are fixed on Spotify to do right by musicians, Abu Dhabi has become a global hub for music-streaming apps, disrupting the global music industry.17 Anghami, a legal music-streaming app, has become the first Arab tech startup to go public on New York’s Nasdaq stock exchange. These Global South entrepreneurs have much in common. They are chronically underestimated, they must hit the ground running and deliver profits, and their price-conscious users demand added value for them to part with their money. Their only option is to think outside the box.

Out-Pirate the Pirates

Tech entrepreneurs in the Global South must innovate in environments where piracy is the norm, users come with constrained budgets, and streaming is a challenge with unreliable connectivity. By 2028, 70 percent of global subscriber growth for music-streaming services is estimated to take place in the Middle East, Latin America, Asia Pacific, and Africa. Anghami’s Lebanese cofounder, Elie Habib, explains, “Our start was to out-pirate the pirates.”18

The Spotify business model does not work for Arab users because most Arabic music is independent and not backed by a label. Anghami pays more to artists and less to labels. The company launched as mobile-first for scaling across emerging markets and invested locally. They started by building relationships with labels and musicians in the Middle East before going global. Educating users on streaming rather than finger-wagging on piracy helped build a loyal base. The startup needed to make revenue from the get-go, given the unappetizing deals from venture capital funding.

Diversity and culture are strengths, not barriers. World music is not some niche, but the norm. Habib believes that designers should cater to user aspirations and argues that music is intrinsically social. He remarks on how Spotify executives assume their users consume music alone when, in practice, users are deeply social and seek connection with others through music.19 Anghami found that most users shared music with others on WhatsApp and followed the playlists of those that matched their tastes to discover new music. His startup saw the potential in using machine learning to connect users with each other to build on this sharing culture.

While Spotify strategists remain unconvinced about the value of designing for mobile users in the Global South, Anghami leaders have built their business model around it, targeting the resource-constrained and those with precarious incomes. The startup takes this demographic into account by offering daily, weekly, and monthly subscriptions, multiple pricing tiers, and access on low-end mobile devices and 2G networks. Given the high demand for audiovisual entertainment from the next billion users’ demographic and rising mobile uptake, Anghami allows music videos on par with audio. Habib explains the key difference between emerging and Western markets: “It’s not just about launching a service but providing the ability for people to try it, taste it and then eventually commit to it.”20

Western creative industries can flourish if they break out of their caste molds. But public- and private-sector industries must first confront their traditional notions of who and what count as creative and how to treat them right.

The ABCD Principle

In the last few years several apps and platforms have emerged in the Global South with a business model that places the next billion user market at the center. The classic case is Reliance Jio, India’s major telecommunication platform, which made its data the cheapest in the world by catering to India’s vast low-income populace.21 The NBU market was not an afterthought, but the core customer base. Reliance Jio designed its marketing plan by looking at the data usage of this user group. Marketeers closely examined the kinds of content this segment consumed and produced and developed a marketing plan based on the patterns identified. It is called the ABCD principle—an acronym for astrology, Bollywood, cricket, and devotion—the four main areas young users pivot most of their data toward.

Several Asian social media apps, like TikTok, Bigo, and Kuaishou, grew exponentially across the Global South by targeting the underclass.22 This demographic produced content creators overnight due to the apps’ ease of use and data efficiency on cheap phones. Most importantly, what these applications had in common was how their algorithms gave the global poor a fighting chance to be visible online. Their algorithms encouraged serendipitous encounters with complete strangers from across the world.

NBU-friendly apps assume an innate thirst for a diversity of stories and double down on their users’ interest in fresh content. The apps enable users to rise through the social ranks despite their sociolinguistic contexts, and the platforms offer seamless experiences for messaging, live streaming, live video-calling, and short video formats, allowing content to scale across borders.23 As one Pakistani creator on Bigo, a free live streaming app, states, “I’m not even that famous, but when I go out on the street, people recognize me. . . . People want to see new faces. They don’t want to see the same old stars. They want to see someone real.”24

The digital economy in the Global South is in flux. There is a push for innovation, a pull from the underclass, and slow movement from the state to rein in these disruptive forces through regulation. One thing is uncontestable—the Global South is riding the wave of the creator economy. This should not be surprising. If data is king, then these regions win the crown with their rising young populations going online. China and India alone constitute most of the users in the world, and both have yet to reach market saturation.25 By 2030, young Africans are expected to constitute 42 percent of global youth and are in line to significantly disrupt the creator economy.26

The economy of scale is fed by Global South users’ aspiration and enthusiasm for change. Entrepreneurs have had to offer deep and added value to their customers in a highly competitive space with few rules to protect them, little infrastructure to support them, and limited numbers of users with disposable incomes. For decades Global South economies have been predominantly informal and precarious, and in many of these countries, formal employment is a rarity. Eight out of ten workers in Africa are informally employed, the highest share among all regions.27

Moreover, with less than 7 percent of the world enjoying liberal democracy according to the Democratic Index 2021, users are forced to become more creative when online.28 They constantly pioneer creative tactics to circumvent AI-driven state machinery and online censorship regimes. These everyday hacks contribute to the ripening of the creator economy, contrary to some mythical nationalistic quality of innate innovators.

While the creator economy in the West is targeted at the urban elite, the rest of the world is opening up to the marginalized majority. While Silicon Valley views the global poor as high risk, Global South entrepreneurs are increasingly seeing them as opportunities long neglected within the monopolistic tech ecosystem. By building for and with the world’s majority, you can scale up from the bottom.

Contested Creator Class

In 2022, Meta commissioned Richard Florida to revisit his concept of the creator class as it applies to the creator economy.29 Florida, in his report, admits that we need to expand our vision of who these creators are. He stays close to his comfort zone of the United States and extends his paradigm to include the middle class in response to a decade of criticism on his elitist approach to the creator economy. He admits that there is an “immense opportunity to forge a ‘Creator Middle Class.’”30 With the middle-income focus, the Southern creators at the margins are absent again. Florida spins the old yarn of how these creators are “scientists, techies, artists, designers, entertainers and professional knowledge workers in fields like management, healthcare and law,” calling them “passionate hobbyists” who are not creating for money, fame, or followers.

His model remains exclusive and out of touch. Who and what counts as creative needs an urgent rethinking by shedding the cultural baggage that demarcates the West from the rest.

Hacking Creativity

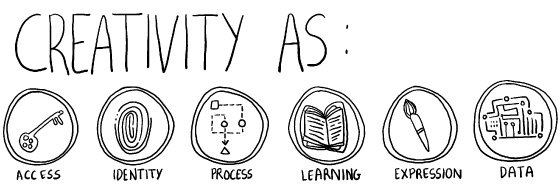

In 2022 a multinational design company hired me in order to gain insights on what digital creativity looks like in the Global South. They were looking to expand from their usual clientele of design professionals and other white-collar creative workers in the West. The company and I agreed to use India as a pilot study given its sociocultural diversity, high digital uptake, and its vast young creator economy. The goal for the pilot was to look at how creativity is defined, practiced, learned, shared, curated, and perhaps even monetized among Indian youth. I was given free rein to design the project and built a ten-person team, spread across different cities in India, that included design educators, videographers, digital ethnographers, and media scholars.31 I partnered with UX researcher Laura Herman to help shape a framework to approach this creator base and translate insights in ways that the design industry could utilize. Our framework looked at how digital creativity is shaped by access, identity, process, data, expression, and learning.

Creativity framework.

Our team investigated questions such as: What kinds of content do the youth aspire to create and why? Which design tools do they use? What was their creative process? How did they navigate issues of access, social and political surveillance, and other constraints when creating? Did they identify as creators? How did they learn to use these design tools? What kinds of creator communities did they belong to?

To narrow our scope, we focused on Gen Z—those born between 1997 and 2012—and targeted two types of groups: one of learners and educators in informal and formal learning contexts, and the other of communicators, artists, designers, small-business owners, entrepreneurs, civic collectives, and media organizations. Our designer-educator Siddhi Gupta led in-person workshops on hacking creativity for youths in different socioeconomic school settings. Next we contracted product designer and influencer Trupti Shirodkar to host a masterclass on her Instagram and YouTube channels to harness insights from her followers.32

Our learners came from three distinct economic brackets: low-, mid-, and upper-income schools. Diversity of the group was critical as we strived to balance gender, religion, caste, class, and other intersecting identities. We spoke to almost eighty creators, including card makers, design students, influencers, digital activists, artisans, designers, ghost creators (intermediaries between creators, clients, and companies), and small-business owners or “micro entrepreneurs” who have their businesses entirely on platforms like Instagram (the cloud-kitchen model, for instance).

A key insight from the pilot was that resource-constrained creators are the most enthusiastic, engaged, and experimental with their creativity online. They break and make rules and carve new pathways into the creator economy. Their creative journeys, however, face numerous barriers: access is limited, constrained, and comes at an economic and social price. Getting the internet’s attention is no small feat when you’re a linguistic minority, or when your content doesn’t resemble the neat Western aesthetics that pervade social media. Learning where to post, whom to tag, how to format, and what kinds of voiceovers to do means that education must be gotten on the go. Far from being deterred, these creators were determined to make their mark in this digital creative space.

Access as a One-Stop Shop

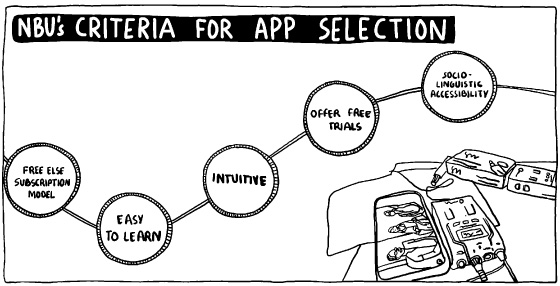

An eighteen-year-old design student works after her classes from 4 to 9 p.m. This leaves her with one hour for digital leisure every evening. In this limited time, she consumes and produces content. She does not want to spend a large amount of time learning how to use complicated design software. Instead, she opts for free, easy-to-use, and quick photo-editing applications. Most low-income youth, including her, have multiple jobs to supplement their family income, and girls are required to help with household chores on top of these jobs. For youths like her, time is money. They consume and create content quickly, scheduling their time like CEOs on the run. Moreover, they are not just mobile-first creators, but mobile-only. The odds of them being able to afford a tablet or laptop in their lifetime are slim.

Their biggest demand is to have a one-stop shop of creative tools. For them, portability is key. They spend hours hunting for the right tools, apps, templates, and software. Their criteria are that their suite of tools be free, intuitive, easy to use, mobile-based, and supportive of vernacular languages and designs. Their creative process is intrinsically social. They ask for tips on influencers to follow and YouTube clips to watch, and they trade ideas, run designs with peers, and basically chat on what is trending. Any tool that needs a lengthy tutorial is not meant for them, and due to their limited budgets, these youths don’t appreciate complex applications designed to intimidate them.

A creative community of sorts mobilizes when in-application support fails, as instructions on apps are often in English. Youths crave a creative hub where all this action can happen in one place, a demand shared across socioeconomic groups. Users from the wealthier class must switch between multiple devices (phones and laptops) and types of software when editing audiovisual content. This makes the creative process tedious and ill-fitting with the demands of the contemporary creator economy. Free apps can be “clunky,” however, admits a media manager for a small NGO. He doesn’t have his desired choice of templates or music overlays. Creating is a compromise when you don’t have the money, as “all the best stuff is like you have to pay for it,” he says.33

Piracy is the primary solution to access issues. Resource-constrained creators prefer free applications that replicate licensed software, and not just for the cost savings. These creators need software that can run on smartphones with low memory capacity, using less data. In addition, they perceive expensive applications as tools for users with advanced skills.

Culture mediates access. Parental control is heavy among middle- and upper-class groups, though less so among low-income groups. Parents watch their kids like hawks and expect them to be utility-driven in their content creation. Creativity is suspect and confounding to these helicopter parents. Youths exercise creative tactics to gain access free from parental surveillance. As one youth puts it, “I use Instagram from my father’s phone, but he doesn’t know.”34

Profiles and devices are not necessarily shared due to resource constraints. They can be strategic choices for (in)visibility, especially when the content is politically contentious. While a super-app of creative convergence is a dream across groups, creators expressed their reservations. They wonder if an affordable creative hub is a pipe dream.

Niche Is Scalable

Creators hunt for online niches to go mainstream. Remixing niches can create virality. Combining poetry and food marketing, or Kerala pickles and adventure travel, is the norm. As one aspirational influencer puts it, “My poetry should reach more and more people. I want to join hands with products or companies, may it be food products or specific products.”35

Micro entrepreneurs such as Goodboy Kitchen (@goodboy_kitchen on Instagram) combine the rising craze for special dog breeds among Indian elites with socially conscious marketing of plastic-free packaging—from Instagram to their doorstep. Cloud-kitchen models promise Kerala pickles from their farm to the diaspora’s table.

A niche can be simple, humble, grounded, and yet gain global attention if it hits the right emotive nerve. Village fashion influencers like Neel Ranaut (@ranautneel on Instagram) from Tripura have gone viral and gained more followers than most of the top fashion brands in India. Ranaut combines stones, petals, leaves, and flowers with adhesive tape and parades through their village. The cognitive dissonance of playing with gender identities, fashion trends, and village stereotypes have hooked millions on their profile.

In recent years, many low-income youths have become influencers through body flips, lip syncing to popular songs, and cool dance moves. Tanzanian village influencers Kili Paul (@kili_paul on Instagram) and his sister Neema Paul (@neemapaul155 on Instagram) have garnered millions of followers, from India in particular, as they move and groove while lip-syncing to popular Bollywood and Tollywood songs. In February 2022 the Indian High Commission honored Kili Paul for winning “millions of hearts” in India for his creative contribution.36

Small-time artists try their luck on Instagram by getting extremely specialized and contextual. Relatability boosts engagement. The local can transform into the universal by tapping into global aspirations for travel, food, entertainment, community, and intimacy. Content creators need to carve their niches and stay with it, as one ghostwriter for a media organization explains:

Whatever your niche, whatever be your category, on that basis you have to create content because people follow you from that point that this is a dancer, this is a food vlogger. . . . On that you can’t switch your niche. So, decide first your niche and then on that niche relevant content should be posted.37

Niches have limits. Micro entrepreneurs must balance scalability and selectivity due to limits in logistics. While their businesses may be entirely on Facebook, Instagram, or WhatsApp and promise unlimited growth, they still have limited offline production and delivery capacity. Artists have modest aspirations for follower counts since their price points are high and thereby affordable only for premium clientele. Civic activists may have specific causes that are tied to a mission or an event, which may not align with the medium of virality, as one NGO member shares:

The entire social media game depends a lot on making reels.38 But as an organization, it also gets difficult to make reels, because what are we supposed to do . . . the topics that we work on are so sensitive that we can’t make it, you know, we can’t always make certain things that goes along with the, you know, trending audios. But we can’t dance to audio, right? We can’t do the trends. So, we can’t jump into every trend with the sensitive topics that we have. So, it gets very difficult to engage at times.39

Typically, though, aspirational influencers aim for masses of followers to attract advertisers, paid partnerships, affiliate marketing, and ads on reels. They optimize many platforms, including Indian apps like ShareChat, Moj, Josh, Nojoto, and Chingari, beyond the usual suspects such as Facebook and Instagram.40

Many content creators recognize that their content is niche. To survive in this game, creators need to be authentic to their context. Their cultural capital, where they come from—their village, or what they wear, or what they eat, or how they dance—can be turned into useful data if remixed with the right K-pop dance or Bollywood song. What was once considered “primitive” is now prime for the algorithm.

Product Is Process

Creativity is collaborative. An aspirational influencer describes her creative process:

When I have to create a masterpiece, a very visually appealing content, and I do not want to deal with learning how to use a difficult application, I choose to collaborate. In such a situation, I get to focus on the content part of the project, like the storyline/plot, and the other team member who is an expert with an application will manage the visuals.41

You can create a digital “masterpiece” and yet share creative ownership. Young creators view themselves as creative “geniuses” as well as collaborators. They don’t view this as a contradiction; it is their creative reality. Aspirational influencers put tremendous energy into the creative process; staying trendy can be exhausting and putting their content out in the wild can be risky. It helps to have a creative community to transform concepts into content, test ideas in a safe space, and build relationships and buy-in with peers. Reciprocity is fuel to these creative fissures. Online groups play a vital role in reinforcing the collective creative identity of members. They help resource-constrained users access expensive applications and learn resources through designer-driven mentorship programs online, “giveaway” awards in competitions, and joint scholarships for licensed apps.

Marginalized creators find cultural belonging for their creative expression. They seek out “DIY Clubs,” hashtag networks, and curation communes. Followers also have a role to play in this creative collaboration. Aspirational influencers seek to co-create with their followers to keep the conversation going and deepen fan loyalty. Influencers and creators establish authenticity, trust, and credibility by sharing their raw products with their audience. At the same time, creators’ obsession with novelty gives way to remixing as the creative standard.

Remixing is at the core of self-expression and is well suited to digital cultures that are built through networks, cross-posting, and collaborations. Creators view the process of building on other people’s content as creative and critical in this trending culture. Youths are unapologetic and frank about their creative approach; as one of them explains, “Remixing content, mashing things up, and reviving old trends are very important because you do not always have something to say.”42 Content without visibility is meaningless, as one Gen Z youth puts it: “What is the point of making [something] if I can’t post [it].”43

Culture of Credit

Attribution over ownership is the new ethical code of practice among creators. Rising creatives value giving credit to originators via online tags to acknowledge inspiration. It is flattering for many creators to be copied; as one remarks, “I feel good that someone is copying. I feel that I must have at least done something good to warrant that.”44 However, it is inexcusable to not give due credit.

This is felt most acutely among rural and semi-urban creators. They are deeply tuned into the copyright regime as they have been at the receiving end of intellectual and creative theft from mass cultural industries for decades. They want content protection like watermarks and fair remuneration systems. However, in the face of these challenges, they are resilient, as one rural influencer defiantly remarks:

Today they [other content creators] might copy and take one or two creations of mine today or tomorrow, finally they will have to do something on their own, how long can they be dependent on me. If they take one or two palm full of water from an ocean, what difference will it make?45

Increasingly, creators are demanding that attributions be factored into the design of the platforms. With rising protests by influential creators of color, TikTok’s director of creator community Kudzi Chikumbu in a 2022 press statement announced the new “culture of credit.”46 The goal is to introduce features that will make the algorithm more equitable for underrepresented creators. Chikumbu promised creators that they would finally have crediting tools like the ability to directly tag or mention in the video inspirations behind their content. TikTok has added user prompts to nudge creators to give credit, educating users on the importance of crediting via features like pop-ups.47 TikTok also debuted an “originators series” that highlights trendsetting creators on their site every month to build awareness of creative attribution for a global creator community.48 While it is a step in the right direction, this does not fundamentally align with redistribution or profit sharing between creators and platforms. Moreover, attribution is still talked about in terms of individual creators online, with little attention to the offline social networks of creators that enable these creative products and processes.

Creativity has long been a collective process.49 This is especially so among artisans in the Global South. Our algorithmic cultures, however, are biased toward computing individual people’s products and processes. For instance, in Bangladesh, women make up 60 percent of the labor force in the creative industries but barely eke out a living from their creative work.50 Prominent heritage crafts like kantha are made by rural women who gather in a household and repurpose worn-out clothes with intricate embroidery. Ownership, here, is by the village where it is produced.

The pandemic pushed many of these artisans to sell their creations online, inspiring several social entrepreneurs like Shimmy and Bengal Muslin to step up and equip these women to leverage digital resources and boost their living. Many women artisans have had to rely on male family members who had better digital skills and access to mobile phones. These new intermediaries have resulted in further cuts from their already meager livelihoods.

There is a double standard on platforms like Etsy, which claims to be a digital space for “millions of people selling the things they love.” In practice, its typical creators are middle-class white women who do artisanal work as a hobby. Their craft is recognized as personal, handmade, and authentic. However, if the kantha women’s groups came on Etsy, they would be viewed as commercial and mass produced. In conventional design hierarchy, individual and unique creations trump mass products and collaborative processes. Templates are out to disrupt such hierarchies.

Template Is King, Vernacular Is Queen

Western designers hate templates.51 Many see templates as the beginning of the end of creativity. Then came Canva, cementing the hate. Canva is an Australian multinational graphic design platform that is used to create social media graphics and presentations, offering users with easy-to-use, ready-made templates that they can customize to produce professional designs. Founded by Melanie Perkins in Perth, Australia, in 2013, this template-driven design platform was valued at $40 billion in 2022. With a monthly user base of 75 million, it is considered one of the most influential design apps worldwide. This mass production of creativity has many designers in Silicon Valley appalled.

Drew Clemente, a systems administrator engineer, captures this angst in what he calls a “dangerous trend” of “bad design.” In a rant titled “Why Do Designers Hate Canva?” he speaks on behalf of his cabal by accusing Canva of producing designs that are crude, chaotic, unpleasant, garish, tacky, amateurish, and lacking in sophistication.52 He laments that their business model perpetuates a new aesthetic lacking in “basic design principles.” He detests Canva’s premise that “design is easy” and sees it as a direct insult to professional designers whose careers are threatened by this new worldview. He is convinced that Canva has made “the world a worse place” by making it “harder for people to appreciate good design when they see it.”

Against this passionate sentiment, the young content creators we interviewed in India see things differently. They swear by Canva. They do not believe in suffering through a rite of passage to reach a “designerly” level. They want to hit the ground running. They don’t think design is easy; they expect design to be easy. Amateur aesthetic overrides sophisticated designs in allowing creators to respond to trends in a timely manner and showcase their authenticity. Design principles, for them, take a back seat to what the trends demand. These youths have no intention of pretending to be professionals. Their amateur status sometimes gives them more credibility among their followers. What may be garish, tacky, and unpleasant to designers schooled in Western aesthetics may just work in the Global South, given the right mood, theme, and context. Creators place a premium on emotion as a driver for creative expression.

Across income groups, creators prefer using templates for three reasons: templates enable the foundational work of content creation, allow for aesthetic consistency, and make it easier to cross-share. Low-income creators are avid fans of these ready-made formats and features. They insist that contrary to the idea that templates reduce creativity, using templates frees them from technical functions and carves out more time for them to be creative. On the one hand, creators want to be original, but on the other, they want to fit in, and templates allow them to do both. Customizing templates then helps creators build ownership and originality. As one creator states, “If there is a template which has ABC elements, I try to remove 2–3 elements and then I edit . . . and make it my own and then I post it.”53 Some creators interpret “templates” to mean distinctive styles of content posted on their accounts.

Every bit of a creator’s decision-making personalizes their templates. Their choice of captions, tags, filters, hashtags, color schemes, post timing, and occasions contributes to making the template their own. Creators in NGOs recognize that some designs can be off-putting to their target audience and “very arty or out of reach.” There is a class dimension here; creators in NGOs are often middle-class, while their audiences may be from lower economic segments. “We try to make it as bright and nice and beautiful as possible in a way that doesn’t isolate or alienate the people.”54

Desi versus the Instagram Aesthetic

With twenty-two official languages and almost twenty thousand dialects in India, local or vernacular design is on the rise, catering to a variety of sociolinguistic needs.55 But vernacular design is not confined to linguistic needs; it also valorizes diverse cultural aesthetics. “Desi” (a colloquial term for Indian) aesthetic is becoming increasingly popular among civic collectives, artists, and a broader swath of middle-class youth in India. Young creators feel cultural pride in heritage designs and colorful palettes. They recognize that Western minimalism is just one aesthetic, and not the idealized taste marketed in design schools over generations. However, creators complain that some of these indigenous apps are too busy, dense, and unintuitive in their interfacing.

Aesthetics are not abstract principles. They are tools for mobility. The “Instagram aesthetic” is an aspirational aesthetic, especially for creators from rural and semi-urban areas. It gives their expression a “foreign vibe” with its minimalism and use of whites and soft color palettes. Marginalized creators see themselves as global citizens and make social media their digital neighborhood. This doesn’t negate their cultural capital. Creators generate desi templates for the numerous festivals, rituals, and events celebrated in India. Rural creators like their bling as it captures the festive mood. However, if the mood is more thoughtful, they adopt a more sober aesthetic. They try out drafts on indigenous short video apps like Moj, Josh, and ShareChat, before going “public” on Instagram.

Global South creators are aware of the creative tax they pay when using vernacular-based design. Western platforms’ grammar of virality does not easily allow for a diversity of languages, cultural slang, visual representation of emojis, and themes. The obstacles of font options, formats, and language syntaxes push them to strive for a purely visual aesthetic. At the end of the day, however, engagement metrics rule the roost and dictate aesthetic choice. This demands constant learning and applying if creators are to stay relevant, connected, and visible.

Jugaad Learning

I have previously written about how the global poor have been celebrated for “hacking poverty” through jugaad, an Indian term that means “to improvise, particularly as a response to scarce resources and rigid social systems.”56 The term has entered the Oxford dictionary with a definition that emphasizes its innovative angle—“the use of skill and imagination to find an easy solution to a problem or to fix or make something using cheap, basic items.”57

Jugaad as a creative practice is intrinsically cross-cultural. Chinese people call it shan-zai; Brazilians call it gambiarra or bacalhau, and Americans call it “hacking” or do-it-yourself (DIY). Jugaad strives to be more time-, labor-, and cost-efficient. As a product, it implies an affordable replica applied in different contexts, or an alteration to and even improvement on an existing feature, function, or entire design.

Jugaad through informal learning is increasingly taking on new and creative forms. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted formal public education and legitimized DIY learning among youth.58 Creators’ choices online have expanded significantly, helping them build their own “curricula” of mentorship, knowledge, and networks. Many low-income youths perceive lengthy online tutorials and formal curricula as out of touch, slow, inefficient, tedious, and unnecessarily complex, viewing these traditional methods as “passive learning.” To produce as you consume is the active way. Creators learn through YouTube videos and Instagram reels, with trial and error leading the way, as one aspiring designer explains:

I think training is not the right word, maybe practice like if I have. . . . For example the first time I did embossing, I learnt it from a video that I saw online, the first time I did it, it was a bit weird, and the embossing was falling off from places. Once I did that technique 5 or 10 times, with practice I got the hang of it.59

Another creator shares her challenge of trying to complete an online Domestika course but dropping out due to lack of time. She then joined creative communities online and started to fiddle around with different interfaces, to see what sticks and what doesn’t. “If it [online feature] works then I make it like a regular thing in my job. If X feature is working well and the output is nice, I’ll continue using it. If it doesn’t then I scrap it out.”60

Self-Taught Is Cool Yet Cumbersome

Self-teaching has become “cool” across different groups. Creators gain respect from their peers when they learn by doing. Creators’ DIY education can cover how to use software tools, set up a profile, and employ different tactics to increase reach and engagement. Experimentation unpacks the metrics that dictate their daily curricula. Since digital creativity demands nonstop content production and analysis, creators put a lot of pressure on themselves to be consistent in sharing content. Some creators record videos of their work to analyze later and gauge how far they have come: Why does one post gain attention while another post is ignored? What format works well for which type of content? What kinds of popular content forms should be remixed to optimize engagement? An aspirational influencer tries to figure out, “if I use a song that has only 7000 people using it, that might do well because that will show up on people’s pictures. And then it depends if I show my face. I get more views when I show my face.”61

Many creators strive for a formula to get the engagement right. A “successful” creation depends on the right mix of likes, comments, shares, and views that the posts generate. Some creators get specific, saying, “The engagement rate should be about more than 4 percent. Means above 4 percent it is best, means your content is working.”62 Some bet on the post’s timing to get it right. They have learned the optimal and active follower time the hard way. As one influencer explains, “If I posted in morning, I get between up to 10, I guess 10,000 views . . . afterwards, it goes up to 50 to 40,000 on Moj.”63

Learning isn’t a lonely activity. Creators need communities to learn from and with to feel protected and encouraged and to figure things out together. Many realize that being a creator is a “relatively lonely career.” They seek mentors to review their portfolios online—artists want others to help them price their art; designers want tips on trends, tools, and templates for inspiration; NGOs dealing with vulnerable communities want advice on how to protect their clientele through anonymous messaging, strategic blocking, and other tactics. Women creators seek solidarity as they are disproportionately harassed online. They tap into their forums to tackle issues such as sexual threats, as they face privacy breaches more frequently than their male counterparts. Creators receive a barrage of messages on social media platforms and rarely reply, constantly trying to learn how to manage their communication. They are also inundated with live show requests. Engaging with these kinds of varied requests can be tricky, especially for women creators, as it opens a pathway to inappropriate advances and comments. Creators are, therefore, eager to learn when to use video options and when to close tagging.

At the same time, jugaad learning doesn’t negate formal education. It comes down to desirable networks, time with mentors, and quality feedback. Creators talk of the struggle to get this support online; as one aspiring designer explains, “Learning a tool is a DIY thing, but your designs need a qualitative evaluation. You need someone to tell you what will work and what won’t.”64

Creators learn quickly that you need to perform or perish. They learn the hard way to gamify themselves, their emotions, their cultures, and their bodies, sometimes to their detriment. Their pedagogic toolkit is stacked with tips on navigating social harassment, especially if they are a part of the marginalized majority. Their communities have taught them ways to build solidarity, support, and resilience against platforms for fairer remuneration. Despite it all, they are optimistic about their digital futures. Their creativity is a mirror of their aspirations.

Next Billion Creatives

India is just one case among many Global South creator economies where we see creativity play out online every day. While on average 20 percent of internet users worldwide follow an influencer, in Brazil, the figure is double that. A consumer survey by Statista, a data company, shows that two-fifths of Brazilians say they bought a product because of an influencer, the highest share among the fifty-six countries surveyed.65 Nielsen, a market-research firm, estimates that Brazil has five hundred thousand potential influencers on social media, more than anywhere else in the world.66

In fact, these companies have discovered that the next billion creatives drive the creator economy. Creators from resource-constrained contexts are taking the lead, being self-driven and self-taught, given their limited options. The digital has created a niche that can help these creators scale. Southern creators pioneer clever shortcuts to enable their creative processes and learn on the fly due to limited leisure time. They are unapologetic about their economic status, and in fact take pride in producing more with less.

Their expressions find a virtual home and resonate with a global creative community, despite the dominance of the Western aesthetic on social apps. While their privacy matters, their visibility matters more. They are acutely aware of the fierceness of the attention economy and often use their data as currency. They are hungry for followers, likes, and comments, and keenly study their metrics to remix and reshare their posts to get it right. However, many refuse to call themselves “influencers” as they reserve this title for those able to monetize their content and earn a livelihood from it. A few detest the traditional view of an “influencer” who tries to peddle brands and get people to “buy stuff.” Most did not expect to be an influencer in the conventional sense of being able to attract hundreds of thousands of followers. Creators want to get rich and famous from content monetization but are realistic about their prospects. Their aspirations are to nurture a community beyond what they are born into, have fun, gain status, and, most importantly, make a mark “out there” through their digital expression. These creative climbers are aspirational influencers. They live by a code of digital creative practice and want to be recognized and respected by an online public. They believe that when you are true to yourself while creating content, you become relatable to others. They want to be seen and heard. It’s their entry point to a better future.