3

Digital Desire

“Raise your hand if you do not watch porn.” Audiences hesitate, then laugh uncomfortably. Almost nobody raises their hands. I bring up this question in my talk circuits in Hamburg, Panama, Copenhagen, and Amsterdam when speaking about future digital trends. This provocation evokes the same response across audiences—digital-marketing specialists, entrepreneurs, policymakers, investors, and programmers.

At one telecom conference, a manager comes up to me after the event and tells me that I talked about the “elephant in the room.” He says his Latin American team deliberately ignores customer metrics on mobile data usage for porn. This way they don’t need to disclose these trends as doing so may cause panic among state officials. Online porn keeps their businesses going and enables mobile uptake among digital newbies—the tech industry’s best-kept open secret.

A health and development magazine asks me to edit my op-ed and delete a section on sexuality in health care in developing countries. In the editorial, I had written about how health care has been historically geared toward population control and family planning instead of toward normalizing sex and sexuality as essential parts of human experience. Youths want to discover themselves and their desires, and these metrics can reveal honest patterns of young people’s intimate needs and wants, especially in Global South countries where sex is taboo. The editor agrees but says she is concerned about their public health readership, which is focused on family-planning interventions and has more conservative values. Sex is like Voldemort: that which cannot be named.

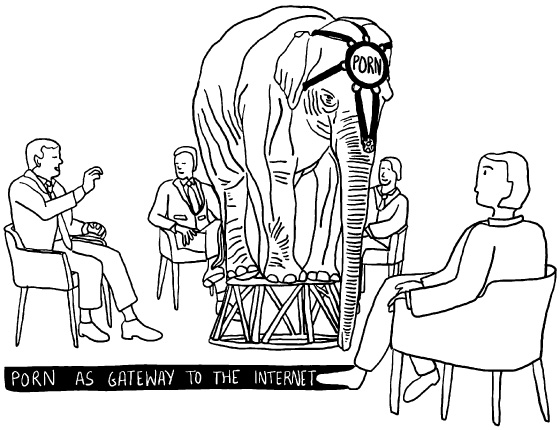

Despite society’s moral panic, porn is and always has been the gateway to the internet. Thirty-five percent of all internet downloads are related to porn, and women make up one-third of porn-viewing audiences.1 Few public institutions provide content that speaks to youths coming of age, especially about sex. Youth have few people or places to turn to for information or reassurance about their bodies, sexualities, and sexual insecurities. It is no wonder that porn has become an educator for teens across the Global South.

We need to shift the social mindset of a war on vulgarity by making peace with sex. Policymakers and tech entrepreneurs should take a pleasure-positive approach to sex and sexuality on the internet that considers normalizing sex and recognizing its stealth data politics.

Indecent Proposal

Governments, especially in the Global South, are proactive about moral controls. Ministries crack down on “indecent” content. Officials instruct their information technology (IT) divisions to weaponize content moderators, digital vigilantes, and machine learning technologies to be the moral police for the digital age. The definition of porn has expanded in patriarchal states. For instance, influencers in Iran face long jail sentences for promoting “vulgar” content that spans workout videos, dancing, and fashion.2 China hunts down live streamers who post homosexual content, which their government perceives as “obscene.”3 Kissing in public is taboo in India and can result in obscenity charges.4 Indonesia blocks thousands of porn sites and other websites deemed immoral. This is part of its Internet Sehat (Healthy Internet) program, which strives to reduce “prohibited information,” including “blasphemy,” and content that “creates community anxiety” and “disturbs public order.”5 According to the 2022 Internet Censorship report comparing global internet restrictions, 82 percent of Asian countries restrict online pornography, and twenty-seven of them have instituted full bans.6 These restrictions include bans on torrents, pornography, social media, virtual private networks (VPNs), and messaging/VoIP apps.

Similarly, the Gulf region exercises moral control on the internet by blocking adult sites. Even browsing these sites is a serious, punishable offense. Yet six Muslim states rank among the ten countries that watch the most porn.7 These figures are underestimated as sex-related content has pervaded social media and is hard to track. Encrypted spaces are thriving with the sharing of intimate, and often nonconsensual, sexual content. Whether we are trying to shop, pay our bills, chat with a friend, or look up the news, sex has a way of getting our attention online. Despite these moral controls, youth make headway on the internet in producing and consuming content on love, sex, and relationships. And youth in the Global South are much like teens worldwide, for whom sex and sexuality are fundamental pathways to self-development.

Metrics of Intimacy

Facebook campaigns on sex and pleasure in Egypt, Kenya, and Mexico appear visibly dead with almost no likes, comments, or shares. Yet activists are encouraged by their millions of loyal stealth followers, tracked using back-end metrics. The Facebook page Love Matters Naija, a Nigerian nonprofit initiative on “love, sex & everything in between,” is a case in point. Data on audience engagement allows this agency to shape its content on sexuality to feed this silent revolution. Engagement metrics and intimacy proxies are the landscape of digital desire in the Global South. Posts on Love Matters Naija, however, are frank, open, unfiltered, and can stir up heated debate on sex:

Nipples are not an erogenous zone for everybody. It is not everybody that gets turned on from nipple stimulation. It is better not to assume that sucking the nipple will just turn anybody on. There are some people that can reach cloud 12 if their nipples are sucked. There are others that even if you suck from now till the end of this year, nothing will stand or get wet.

Which one of these two types of people are you?8

One man responds, “Mere seating close to my partner turns me on,” while another remarks, “A man that has money and know how to segz. Anywhere he touches on lady’s body, that lady must turn on by force.” A woman complains about men commenting on this post instead of women: “My question is why is there no lady answering the question bcoz I think the question is for us.”

Set up in 2018, this page gained 400,000 fans on Facebook within 18 months. The Arabic page is even more popular, with 2.5 million followers in 2022, and some of their videos watched over 72 million times. Compared to the Nigerian page, the Arabic page has even fewer comments and likes.

In June 2022, I was invited to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of RNW Media, an international digital media organization based in Haarlem in the Netherlands. It was RNW that established the Love Matters program in India in 2011 and then scaled it across Asia, Africa, and the Arab world through a social franchise model. Subsidized initially by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the campaign grew in numbers, funding, and collaborations and continues to help millions of young people to have open and respectful conversations about love, sex, and relationships that are otherwise censored or considered taboo.

For the anniversary, local leaders of the Love Matters initiatives in Burundi, Lebanon, and the Arab world were flown in to share their experiences of growing this movement online. Sandy Abdelmessih, project manager for Love Matters Arabic, explained how her team updates their strategies daily by looking closely at the metrics, which often don’t match the comments section. They have found encouraging signs of high youth motivation for their content. As Abdelmessih remarks,

There is an assumption always that you cannot speak about or put content about masturbation online because people would feel like this is so inappropriate and you’re encouraging people to do behaviors that are prohibited by a religion and that does not fit our culture. But surprisingly the pieces about masturbation are always on the top visited pages on our website and we receive around 18 million page views per year.9

While millions visit and follow their platforms, she states that Egyptian officials argue against circulating “these kinds of topics” in the public, pointing out that people will learn about sex after marriage. She concludes wryly, “Obviously all Egyptians do not masturbate.”

Risky Content

My FemLab team interviewed several NGOs in India between March and June 2022 to understand how they create digital content to engage their audiences on matters regarding sexuality and found similar challenges. One nonprofit expressed frustration about how moralistic some people can get online, which leaves little room for an open conversation about sex.

There needs to be a place for people to put out their personal narratives without them being held up to such perfect political standards. . . . I know people have got little pissed at any content about—like the topic of porn really kind of angers people. Because everyone immediately imagines about the worst-case scenario of possibilities, but our position has always been okay it is a part of people’s lives, we can’t just ignore it and directly add to the shame that is already there.10

We found that platforms like Facebook and Instagram are more conservative when it comes to sex. Their default strategy for “risky” content is to censor, ban, or make it invisible. An activist shares her experience:

I mean sometimes they [digital platforms like Facebook] don’t even allow there to be drawings of nude bodies. And even like the kind of posts that we can promote . . . like a video on abortion is just impossible . . . we had to change the text, not mention sex or abortion directly in the caption in order to promote a video which also almost defeats the purpose, because it gets classified as solicitation.11

Mahwish Gul, a development management consultant, explains why we need an app just to talk about menstruation in Pakistan, where two-thirds of teenage girls are unaware of menstruation at the time of their first period. This knowledge deficit creates anxiety, guilt, and distress, as expressed by a thirteen-year-old girl who says, “I thought this only happened to me. I thought my mother would be angry to know this. I thought she would say it happened because I did something to myself.”12

Gul collaborated with the East West Center in Hawai‘i and the Center for Communication Programs in Pakistan to develop the #HelpSaira app. This tool uses storytelling to get teenage girls, parents, and other community members to engage with common prejudices against menstruation and offer model responses to combat notions of wrongdoing. Alongside many sex education organizations and activists, Gul faced an uphill battle to bring topics around sex, sexuality, and sexual preferences into the open. Patriarchal institutions saw these efforts as “foreign imports” that challenged their culture and traditions. Yet metrics gathered from user responses to the app have the potential to counter these falsities and push the state to initiate and shape public awareness campaigns around these taboo subjects, and, perhaps, establish sex education programs in schools.

Toxic Taboos Online

Metrics-based activism is not a standalone technique of outreach. NGOs have found working with artists, influencers, and entertainers and organizing in-person festivals and workshops to be effective in getting their campaigns out. Mediators navigate the balance between nudging people to keep an open mind while not imposing their own views. Organic approaches with targeted content using metrics such as gender, age, location, engagements, and popular themes based on pageviews help reach the most vulnerable groups.

According to a 2020 study from the Pew Research Center on global laws and norms around same-sex marriage and LGBTQIA+ rights, public opinion remains divided according to country, region, and economic development.13 While significant progress has been made across regions, including South Africa, India, and South Korea, toward acceptance of homosexuality, factors such as religion continue to present obstacles to acceptance.

Taboos of touch are complicated by cultural factors like caste. The morality around “untouchability” is further structured by the caste system in India. As globalization scholar Arjun Appadurai explains, “We live in a world where the senses have both expanded and shrunk” based on our caste positioning.14 In this immersive digital world, while digital tools can allow for cross-caste contact and communication, they also enable targeted contact of Dalits, the so-called untouchables, through invasive biometrics of fingerprinting, tracking, carding, and other surveillance. In such cases, Appadurai argues, “Social warmth is not only not welcome, it is dangerous, since it might well promote other sorts of intimacy which endanger the haptic order of caste.”15

Sex taboos, institutional silence, and cultural shame have pushed young people to seek alternative spaces to learn about sex and sexuality. Many youths view porn sites as places that encourage society to perceive women as sex objects and set unrealistic standards and expectations. Yet they still seek them out as a refuge for sex education due to the lack of legitimate alternatives.16

Pornhub Education

Informal learning has a long history of filling the gaps missed by formal education. Channels like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram have become the go-to portals to learn how to fix a pipe, renovate a roof, braid hair, do makeup, improve your pronunciation, and fill out forms. British journalist Chris Stokel-Walker describes YouTube as having a “do-it-yourself ethic; it is punk TV for the 21st century.”17 Today we all expect to learn from YouTube. What is less expected is seeing youth flock to Pornhub to learn about not just sex but even calculus.

One of Pornhub’s most popular global trends in 2021 was the “How to . . .” search.18 Youth turned to this site to learn about sexual positions, anatomy, and pleasure points, searching “how to touch a woman,” “how to use a condom,” and other burning questions around sex. Some even became sex tutors and hoped to monetize their content. In 2021, Pornhub witnessed instructional searches increase by 244 percent, with more than two hundred thousand videos tagged or titled as “how to” videos. Sex coach Stacy Friedman claims that since the pandemic, there has been uptake from people keen to learn how to enjoy their sexuality.19 Pornhub took notice of this trend and set up a “Real Sex Education” portal.

Pallavi Barnwal, a sex coach for Indians, explains how difficult it is for Indian couples to talk about sex and how that often results in damaging their relationships.20 This is despite India being one of the largest porn consumer nations worldwide, ranked third after the United States and Britain. Barnwal learned the hard way how important it is to speak about issues around sex, having been brought up in a conservative household. She explains how much of our anxiety around sex is not just in the act itself, but in the full ritual around it: “I get dozens of messages from people asking me what to do on a wedding night—not just physically, but how to appear not too shy and not too experienced.”21

Pornhub is not the only one listening. #LearnOnTikTok is one of the most popular hashtags on TikTok, and according to Pentos, an analytics company, videos on this channel have been viewed more than 412 billion times.22 TikTok has become proactive in its sex education agenda with “sex positive” channels and creator spotlights for these accounts. The channel “Asian sex education” has almost 400 million views; on it, “relationship experts” address topics such as how to use a tampon, how to come out to your parents, kissing during sex, long distance tips for sexting, issues with body hair, sex talk, dealing with anxiety, and even learning math.

You may luck out if you are willing and able to get in front of the camera and speak plainly and without condescension on what you are passionate about. Some content creators have realized that the best way to reach youth is to go where they hang out digitally. When classrooms and tutorial centers shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic, many tutors were on the brink of despair. Taiwanese math tutor Shun-Wei Chang, who goes by Changhsu on his channel (@changhsumath), contemplated suicide because of his mounting debt.23 Instead he decided to shoot videos teaching calculus. He quickly realized the competition online, when it came to education videos, was fierce: EdTech had exploded. He set up shop instead on Pornhub with the slogan, “Play Hard, Study Hard!” It worked. His videos have racked up almost two million views, and students now purchase his course packages on his website.

Over the years, content creators have learned that once you have gained an audience’s attention and trust, it is easier to become a guru on other subjects. Amateur creators school themselves on various trends in politics, fashion, and cryptocurrencies to build up to super-influencer status. They view the world as their digital oyster. Take the case of the Peruvian fashion influencer Salan (@salandela on Instagram), who shares her opinions on fashion, politics, abortion, sex, racism, women’s rights, and other socially contentious issues. In her 2021 interview with the Peruvian journalist Jimena Ledgard for Rest of World, she remarks, “I am rather lucky that brands are all about ‘disruptive’ influencers now. They have embraced my political positions, even if they are controversial.”24

It is a sink-or-swim predicament for influencers, since followers punish them for their silence by unfollowing them. Gen Z Peruvians are at a pivotal point of political awakening, given Peru’s social upheaval and numerous corruption scandals. Youth today demand that influencers align with them and take a stand on their issues. Content creators, therefore, walk a precarious line between virality and staying hidden from state censors. Being in the wrong place at the wrong time can become a career killer. Sometimes, when an influencer takes a stand, they might end up being “invited for tea” by the state. Talking about sex remains an art form, while sex education online continues to be on the waiting list of social acceptance.

Invited for Tea

It’s not every day you are invited to tea by your government. This is not the Bridgerton version of Regency niceties. In China, being “invited to tea” is code for being interviewed, especially when you have violated specific laws and regulations.

Media scholars Jian Lin and Jeroen De Kloet argue that the Chinese internet governance rules are “not just about ‘restructuring the economy,’ but also about restructuring culture and society.”25 They investigated the use and regulation of Kuaishou, China’s first short-video platform, founded in 2011 and nicknamed “Snack Video.”26 It quickly became the most downloaded app on Google Play and App Store in eight countries, including Brazil, Pakistan, and Indonesia. Its initial popularity was due to the app targeting people from rural areas and second- and third-tier cities. Given their business model, the app relied more on e-commerce than on advertising revenue, and the algorithm rewarded content creators boasting highly engaged user bases. Chinese media praised the platform in the early years for “revitalizing Chinese rural culture.”27 The app gave a platform to young people from lower socioeconomic classes who were otherwise deemed invisible.

Li Tianyou, known as Tian You, was a high-school dropout who turned into an internet celebrity by telling stories of his everyday village life. He became popular for live streaming his rap-like performances, building a follower base of thirty-five million viewers. The honeymoon came to an end when one of his songs expressed anger at the growing wealth inequality and discrimination that rural youth like himself faced. In early 2018, China Central Television, the state-controlled network, turned against him and accused him of talking about pornography and drugs in his live-streaming performances. This quickly led to all Chinese platforms banning Tian You and ending his career overnight.28

LGBTQIA+ content also falls into the “immoral” category. Creators dealing with such content are at risk of losing their platforms. The widespread internet crackdown by the Chinese state in 2021 on content deemed inappropriate, wrong, or harmful pushed many platforms to act swiftly or face steep penalties. Queer groups on WeChat were erased, while profiles, influencers, accounts, and entire apps were banned.29 Blued, a location-based dating and live-streaming service for gay and bisexual men, somehow stayed afloat. For a platform with over sixty million registered users worldwide, it is no small feat.30 Blued positions itself as an entertainment and sexual-health company and rarely mentions words like “gay” or “LGBTQIA+,” instead using “diversity” and “community” in reference to its user base.

However, cosmetic semantic changes aren’t sufficient to stay afloat. Blued launched “He Health” in 2019, a site that allows for discreet discussions about sexually transmitted infections and other matters that can be discussed with doctors in private.31 The platform serves as a pharmacy where users can submit their prescriptions online. The parent company, BlueCity, succeeded in garnering a state internet hospital license for telehealth consultations. However, privacy concerns always loom when dealing with sensitive data and morality laws. A gay-rights activist in China shares his concern that these internet crackdowns could inadvertently reveal users’ identities, as “some people are not really out to the public, and they don’t want their sexual orientation to be revealed.”32

Amid these regulatory regimes, even digital humans in the metaverse may not escape unscathed. Standards are a must. The world is facing a tsunami of deepfake sexual content used to blackmail people, generate child pornography, and create misinformation and political upheaval. China is setting standards for digital assistants, virtual influencers, and gaming avatars. On January 28, 2022, China’s State Internet Information Office released a proposal to control deep synthesis technology, which covers deepfakes, virtual scenes, machine-generated audiovisual content, and other emerging digital content. All generative synthetic content must be labeled, and “destabilizing content ranging from subversive incitements to pornography to intellectual property violations” will be banned.33

The morality of a society will be the key driver in interpreting such regulations, from the most humane and rights-focused cultures to amplified surveillance of our intimacy and personhood.

Sexbots for Better, for Worse

Virtual assistants, digital influencers, and avatars are already a multimillion-dollar industry. They are everywhere, helping people bank, shop, travel, and access sexual pleasure. Loneliness is particularly a push factor, a market opportunity for digital companions. Global searches for “romance” and “romantic” on Pornhub more than doubled during the pandemic, and searches for “passionate” and “bromance” have increased significantly.34 This comes at a time when loneliness among youth has risen significantly, amplified by COVID-19 lockdowns.

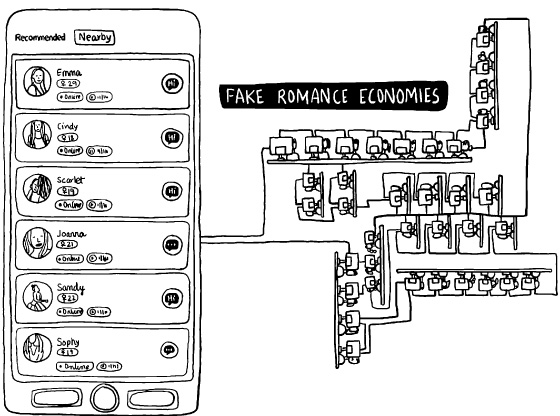

Decades of gender bias in the Global South have also contributed to female infanticide and a skewed gender ratio among younger age groups today. In 2018, men outnumbered women by 70 million in China and India.35 This leaves a lot of young men lonely and vulnerable to digital scams. One such predatory app is L’amour, a Chinese app that became the most downloaded dating app in India.36 In 2019, 14 million users downloaded it, in comparison to Tinder’s 6.6 million downloads over the same period. Indian journalists Snigdha Poonam and Samarth Bansal investigated this app and unearthed a disturbing machinery of exploitation behind it.

They found that ads like “Find a girlfriend in a week” pop up on the Facebook timelines of many young Indian men. This promise of love draws many of them to download the app. Once in, they receive continual push notifications to upgrade their subscriptions so they can chat with girls and unblock supposedly incoming messages from girls. Automated messages such as “Ayesha very interested, and she wants to talk to you,” “Mia is calling, don’t miss out on her,” “Ipshita is inviting you to a video call” inundate the young men. Some cave and pay money to chat with the pretty girls, only to learn that they have been caught up in an internet romance scam. Bots, instead of real girls, are on the receiving end of the young men’s serenades.

Within months negative reviews of this app appeared all over the internet. Despite reviews such as “girls are fake computer control profile so don’t install this app,” and “Google, please keep a sharp eye on L’amour app. It’s totally fake app. It’s only eat people’s money on the name of love,” L’amour stayed available on Google Play.37 As Poonam and Bansal point out, “fraud is never far from any dating service with a mass reach.”38 This app is one among many that follow the trend of boom and bust, minting money under the license of a rising desire for intimacy.

Not all sexbots are deceptive, however. Some are upfront and part of a legitimate, albeit niche, industry designed by men, for men, to cater to one of the highest of human demands—the need for intimacy. Sex robot expert Kate Devlin argues that people seek companionship first and foremost and that sex is secondary to that aspiration.39 The near future is not some smart sex doll with an AI personality, like the image made popular by science-fictional Hollywood movies like Ex-Machina and Her in which humans fall in love with highly advanced humanoids. Our future is of a humbler kind with the right cocktail of live streamers, their fans, and virtual stickers to express the gamut of this romance economy at a price.

East Asia has moved fast on this trend. In Korea users took to live-streaming apps as early as 2006, and most female live streamers engage with male fans by sharing mundane moments. These users eat, sleep, chat, dance, and live their lives in front of their cameras. 17Media is one such live-streaming platform, launched in 2015 in Taiwan. Within two hundred and fifty days it exceeded ten million downloads, thirty million global users, and ten thousand hours of content production daily, beating the growth rates of Instagram and Facebook.40 The app hit a nerve as many young men moved from villages to work in cities, a common phenomenon in the Global South. A representative case is that of a middle-aged factory worker, Junji Chen, who barely has a social life given his crushing work hours. This leaves him isolated and desperate to connect with his favorite live streamer, who goes by the name of Yutong. While Junji has not met her in person, he expresses his affection for her through virtual stickers that can cost him a third of his salary.

These intimacy trends have undoubtedly fostered new concerns about data privacy violations by tech platforms.41 Much of this information is deeply sensitive, given the growing number of morality laws in the Global South. Bioethics experts fear that this growing digital culture will negatively influence how women are represented, treated, and related to.42 Feminists are concerned that these digital tools will replicate toxic behaviors where conversation is porn-style and robots are treated like prostitutes.43

While such fears are legitimate, there must be conversations about the role of and right to sexual fantasy. Much research on sexbots remains speculative, driven by morality concerns instead of the experiences of millions deprived of basic human companionship and comfort. We have a gap between utopian visions of sexual happiness and dystopian perspectives of sexual enslavement. Media design scholars Nicola Döring, Rohangis Mohseni, and Roberto Walter argue that we have a false dichotomy between humanoid artifacts such as sex dolls and robots, on the one hand, and chat bots, avatars, and immersive virtual-reality pornography, on the other.44 Dolls and robots offer the physical satisfaction of touch, stimulation, care, and presence. These tactile needs are fundamental, and their value cannot be underestimated for the millions deprived of these sensorial experiences. Avatars and bots can cater to other forms of desire, tailored to the user’s sexual and social experiences. By combining both affordances, we could provide the “right degree and mixture of materiality and virtuality.”45

Human imagination is powerful and can fill the gap of desires to fit our needs. Sometimes, the less sensorial a digital interaction, the more intimate it can get. Companionship, compassion, and care constitute much of this intimacy ecosystem. However, with increasing online misogyny, the internet may become a space more for men, by men, with sexbots as their future companions.

Digital Abstinence

The current digital culture of increasing misogyny, trolling, doxing, and hate speech targeted disproportionately toward women is shifting digital absence into digital abstinence. Yet retreating from the internet is a negotiated act as the pull factors of entertainment, gossip, socializing, fashion, and romance bring girls back online.

Media educator and UX research partner Kiran Bhatia spent four years in India studying how children from low-income families engaged with digital media. She, media scholar Manisha Pathak-Shelat, and I analyzed her data and confronted an alarming finding—“good girls” are not supposed to go online.46 For instance, Zenab, a fourteen-year-old Muslim girl from a conservative religious family, was brought up to believe that digital technologies spoil girls and ruin their reputations. While she parrots the same argument, her digital behavior reveals more nuance. She operates her Facebook account with some other girl’s photo and name. She regularly comes online to “stalk” her classmates and justifies her online presence as “keep[ing] an eye on what others are doing.”47

Girls use a variety of deceptive strategies to get online. They trade their lunches for mobile top-ups, get their boyfriends to give them secret mobile phones while allowing them to track them online, push shopkeepers to share their Wi-Fi passwords, and pretend to use their limited access for homework while surreptitiously lurking on Facebook. Their digital presence takes a moralistic stance. Many girls are first in line to “slut-shame” other girls who are active on social media, post photos with “scandalous and vulgar” clothes, or show themselves with male friends and friend them.48 They call out girls with “loose characters” and ban them from their social circles. It doesn’t take much to get condemned. A teen girl justifies this digital policing by saying:

In rich societies, girls can do anything, and no one will blame them. For people from my [small town in a conservative family] society, those girls are of weak character. I do not want to be like them. I want to use the phone but just to see what others are doing. . . . Maybe like their photos so that they know I am also on social media.49

Those that defy the rules of online engagement face the wrath of their peers. Another teen girl explains this condemnation:

Why do you share your photos—obviously, you want people to see and then you blame them for seeing? Are you that stupid to share your photos online. . . . Photos can be misused. Do you know what boys do with these photos of girls in their private time? Chiiii. I would never want to be that type of girl, you know!50

Digital reticence is not unique to girls in India. My team found similar behaviors in my project on digital media use among Venezuelan refugees in Brazil for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Rumor mills among girls and women on romance scams, “revenge porn,” and online harassment influence their perceptions. Rita, a twenty-year-old girl in the settlement, reflects on why she thinks twice before posting anything on her timeline:

That friend of mine who gets a lot of likes uploads photos in a top, in lingerie. But I’m not going to do that crazy stuff, because there’s a lot of harassment that comes with that. There is a lot of harassment on social media.51

There is pride among many girls in being offline, as they see themselves as upholders of their families’ virtue and their communities’ honor. Yet they yearn to be seen by their peers and want to feel part of this digital social network. These girls view it as a smart move to be offline but find it emotionally hard to resist being online. They live their online lives in a space between digital demonization and desire.

Safe Space for Romance

Tech entrepreneurs in the Global South recognize the glacial pace of cultural change and some provide alternative ways to participate online. Soulgate, an “algorithm driven virtual social playground where people can create, share, explore, and connect” is one such experiment.52 With more than thirty million users in China, this app connects young people with similar interests using algorithms, but with one major difference—they can only communicate through avatars. To be clear, Soulgate is not a dating app: it does not aim to build offline relationships for its user base, and so it does not allow its users to use their real names, photos, or voices. The platform’s purpose is for young people to drop their labels of job, income, status, and gender and connect with others like them, to “have no lonely person in this world.”53

Anonymity is meant to deliver the freedom to connect and experience digital intimacy. In the last decade, despite good intentions, many apps using anonymity produced increasing sexual harassment online and privacy violations, resulting in their bans. A classic case was the ban of the Secret app in 2014 due to the proliferation of nonconsensual sexual content using their anonymity feature.54 A more recent case is that of Telegram, an end-to-end encrypted chat platform that came under scrutiny in 2022 for allowing the sharing of women’s intimate pictures without their consent. The BBC conducted an investigative report on this matter that revealed how this platform’s minimal content moderation and anonymity resulted in the nonconsensual sharing of thousands of photos and videos of women in at least twenty countries.55

Some tech entrepreneurs see the bias toward visual content in innovation as the core obstacle to intimacy. FRND is a dating app launched in India in 2019 and targeted at second- and third-tier towns. With over five million registered users in 2021, FRND claims to provide “a safe, secure and fun environment for boys and girls to chat anonymously via audio streaming” with a goal of creating a “dating ecosystem for the next billion internet users.” Further, FRND does not allow real pictures, only AI-generated avatars. Their business model utilizes virtual gifting to monetize online courtship between strangers. Bhanu Pratap Singh Tanwar, CEO and cofounder of FRND, explains that by providing a safe platform through public anonymity for Indian youth, especially girls, companies can profit from this untapped romantic market.56

Privacy-driven apps have become synonymous with dating apps. However, building designs based on fear and shame alone would be a disservice to one of the most important joys for human beings—sex. Some organizations are taking the lead to shift their approach from privacy driven to pleasure based. Anne Philpott, director of the Pleasure Project, an international education and advocacy organization, puts “the sexy into safer sex” by promoting pleasure-based education. Her team has analyzed studies on such interventions over two decades and found that being pleasure-centric not only adds fun to our social equation but also has positive impacts on condom use, safe sex, mental health, and happiness.57

What we need are designs for desire that center care, compassion, touch, and intimacy, especially at a time when our lives are becoming increasingly remote and lonely.