5

Green Design

The design community is increasingly normalizing the idea that what is good for the planet is good for people. The American Institute of Architects has made a “materials pledge” to align their designs with values that support the planet and promote social equality. They are developing metrics to translate these values into standards, seeds for a paradigm shift that were sown a decade ago.1

In 2012 the European Commission reported that 80 percent of the environmental impact of products is determined at the design stage.2 The United Kingdom Green Building Council sounded the alarm on the construction industry being responsible for 25 percent of total UK greenhouse gas emissions, and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation reported that businesses could reduce global greenhouse gasses by rethinking how they design everyday products.3 In the last few years podcasts, pledges, and proposals have sprung up among diverse design communities to get on board with this paradigm shift. This time the money has followed. The 2022 Climate Tech report from Tech Nation revealed that climate tech investment raised an unprecedented $111 billion by startups and scale-ups globally.4

As early as 2016, the International Finance Corporation promised $23 trillion to the global agreement on climate change adopted in Paris, seeding climate-smart investments till 2030.5 This has come at a time when the world’s majority outside the West is paying a disproportionate price for decades of Western consumption. United Nations secretary-general António Guterres reminds us, “As is always the case, the poor and vulnerable are the first to suffer and the worst hit.”6 Environmental activists in the Global South call for “climate justice” to equitably redistribute the burdens of climate change. Yet European policymakers and activists rarely look beyond Europe’s fortresses to pioneer green regulations that will impact the world. They see themselves as the world’s regulators by establishing benchmarks, guidelines, and standards for the rest to follow. The “global” value chain starts and ends at their borders. US designers may embrace the rhetoric but not the practice of sustainable living of many at the margins.

“America first” often becomes “America only.” Corporate speech continues to define the billions of people living outside the United States as “rest of world.” In these circles of power, the “global” may be an inconvenience, a threat, high risk, or a weight that they must carry. To do things differently, we can learn from planetary care practices among Indigenous communities in the Global South. Striding forward doesn’t always mean leaving the past behind. There is value in culture for computing a future. We need to dive deep into diverse cultural contexts to avoid reinventing the wheel. Sustainability is indigeneity writ large.

Design for Planet

In 2021 design formally went green. The Design for Planet Festival was the first of its kind to bring together designers, architects, businesses, governments, and activists to rethink how to design our way out of the climate crisis. The festival was part of the prominent global climate summit known as the COP or Conference of the Parties. The United Nations has been hosting this global gathering of world leaders for three decades, but what started as a fringe interest in the planet’s well-being has now reached center stage in the global arena.

I was invited to give a keynote at the festival, in the second week of November 2021. This was going to be my first trip outside of the Netherlands since the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Between the antigen tests and the tram, train, and overnight ferry into Brexitland, travel had lost the allure it once had. However, as soon as economist Kate Raworth kick-started the festival by asking, “If you’re not designing for the planet, what planet are you on?” my passion was back.7

Since the release of Doughnut Economics in 2017, Raworth’s model has been the dominant template for sustainable design.8 She advocates for types of growth that balance “the needs of the living people with that of the living planet.” At the design festival, she posed some critical questions to ask when applying these models: What is our purpose? How can we best contribute? How are we networking and who are we connecting with to enable this purpose? Whose voices count in this process? Who owns these design interventions? How are these systems financed and what do they demand in return? In other words, are humanity’s actions and structures enabling the goals of regenerative and redistributive design?

Raworth points out that Indigenous cultures long ago figured out this balance while Western cultures remain outliers in their worldviews on the relations between humans and nature. Where Raworth stops, I begin. I am working on bringing the voices of the Global South into this conversation. I reminded the audience that what the design community proposes as sustainable strategies have been in practice for generations among Indigenous communities outside the West.

Indigenous Approaches to Design

Indigenous communities across the Global South have, for centuries, related to nature as a sentient being with its own moods, feelings, intelligence, and rights. As designers shift from human-centered to green-centered design, it pays to get out of their comfort zones. Policymakers can learn from Indigenous cultures to address the concurrent global crises. These lessons can aid them in rethinking relations between humans, nature, and technology. These alternative models can go beyond the profit-centric ownership model and the extractive or instrumental approach to sustainable design. The big four that can inspire designers and policymakers are the cultures of frugality, collectivity, subsistence, and repair.

The culture of frugality in resource-constrained contexts in the Global South makes more from less. Business gurus in the West encapsulated this as “frugal innovation” and “frugal engineering” in the early 2000s through an approach that focused on minimal design and economy of scale. This business model has made a comeback with endless seminars, labs, policies, and projects.9 Progressive economists push for the degrowth movement in which frugal living and conscientious consumption form the pathway to sustainable societies.

Women in the Global South nurture a culture of collectivity by allowing for the distribution of risk and caregiving. As ecofeminist Vandana Shiva asserts, “We are either going to have a future where women lead the way to make peace with the Earth or we are not going to have a human future at all.”10 The digital has appropriated this culture for crowdsourcing and crowdfunding, capitalizing on its networked effects.

Subsistence cultures, in Africa for example, have long practiced biodiversity for ecological sustainability. Now social entrepreneurs like the Food Innovation Network have moved into this territory. International NGOs like the Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, and the Wildlife Conservation Society and business coalitions such as Business for Nature have gotten on board with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s mission.

The culture of repair found among Indigenous communities in Latin America and South Asia extends the lives of things. Right to repair legislation has only recently gained legal credence in Europe.11

The fact is that people in the marginalized majority innovate because their survival depends on it. There is an existential urgency to their innovation. They must think outside the box, think laterally, and think creatively, as their communities’ futures are contingent on the planet’s future. As environmental activist Sunderlal Bahuguna puts it, “Ecology is the permanent economy.”12 Despite Indigenous practices, current climate change discourse blames the “population bomb” in Asia and Asia’s growing economy as key culprits in global warming. Moreover, policymakers advocate constraining the economy for ecology. Deep-seated hypocrisies drive this mindset.

Part I: Culture of Frugality

Advocating for frugality without historical reflection and responsibility and dissociating from current consumption behavior and context can exacerbate existing inequalities. This well-meaning worldview may result in pitting environmental sustainability against social equality.

Decolonizing Degrowth

The Global South is often viewed as a big culprit in global warming. China and India top the charts as the world’s biggest polluters outside the United States year after year.13 The Economist has put the onus on Asia to change the course of environmental degradation and expressed skepticism due to what it sees as low political will, weak administrative capacity, and deep investment in maintaining the status quo.14

Racialized roots undergird this worldview. In the 1790s Robert Malthus, an English cleric and economist, triggered a Western moral panic about the “breeding” in the Global South.15 This media narrative emerged during the Industrial Era, when the West was experiencing high population growth and increasing consumption. Meanwhile, the Global South was experiencing mass, early mortality due to colonialism and its violent aftermath.16 Anxieties prevailed over these “developing” nations taking over the world and consuming the planet’s resources.

The Malthusian “overpopulation” hysteria seems to recur with every generation. In 1967 the New York Times released a full-page advertisement, funded by a prominent population control group, blaming the “Third World” for the population bomb, which “threatens the peace of the world.”17 Even in 2022 the primatologist Jane Goodall appeared to have succumbed to the population bomb theory at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland. She remarked that human population growth is responsible for most environmental problems.18 This thinking is at odds with reality.

The UN refutes this persistent false narrative with cold facts—high-income countries have the highest material footprint per capita (29 metric tons per person), “60 percent higher than the upper-middle-income countries (17 metric tons per person) and more than thirteen times the level of low-income countries (2 metric tons per person).”19 The world’s wealthiest 10 percent produces up to 50 percent of the planet’s consumption-based carbon emissions, while the poorest half of humanity contributes only 10 percent.20

We have a problem when an American fridge uses more electricity than a typical African person.21 Western hypocrisy runs deep. Rich countries advocate for clean energy while importing fossil fuels. They can afford to be organic, “go local,” and celebrate their air quality while dumping their e-waste in the Global South.22 Aid agencies offer loans at debilitating interest rates for clean energy, often leaving African countries with little choice but to consume coal or look to their Asian neighbors for investment.

Blanket treatment of different contexts in the name of sustainable design can exacerbate inequality and entrench poverty. While the rich world is preoccupied with making clean energy, countries in Africa are focused on producing more energy—their pathway out of poverty.

Choice versus Condition

The degrowth movement’s advocacy of “voluntary” downscaling of consumption and production is tone-deaf to the realities of disadvantaged populations living with minimal means of survival. “There is an important difference between frugality as a choice and frugality as a social condition,” explains Brazilian development economist Roldan Muradian.23

Moreover, it is false to assume an incompatibility between socioeconomic mobility and environmental care. The degrowth movement fails to recognize that disadvantaged groups view dignified living and planetary well-being as symbiotic and fundamental to their place in the world. Muradian believes this movement of frugal consumption is a well-meaning but deeply delusional ecological project driven by educated, middle-income European groups.

Marginalized communities are not “too poor to be green.”24 Greening is not something Indigenous people “do,” but is essentially how they live.25 While Indigenous peoples constitute 6 percent of the global population, they protect 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity.26 The Sámi people living in the Arctic, for instance, can teach us coexistence through their core principle of eennâm lii eellim (land is life), which shapes their everyday behavior with nature.27 Many Indigenous communities across the world share similar worldviews in which nature enables their culture’s existence. This stands in contrast to Western extractive perspectives that commodify nature to serve people.

Muradian is not alone in critiquing some of the favorite eco-friendly design ideas of our time. Labor market specialists Jana-Chin Rué Glutting and Apoorva Shankar argue that well-meaning trends that strive to achieve a zero-waste system, such as the circular economy, apply a double standard to the Global South. Anglo-Saxon sustainability translates to high-tech solutions with little focus on the root cause of production and consumption. The circular-economy model of “going local” for “clean living” obfuscates the reality of globally integrated supply chains that systematically export waste from the North to the South.28

The data economy has added a new layer of racialized double standards to digital value chains. The metaphor “data is the new oil” is now a material reality. Data centers are big culprits in global warming, alongside single-use plastic items, automotive pollution, and fast fashion.29 With the rise of the next billion users, the questions remain: Who foots the bill for the next billion carbon footprints? Is digital inclusion coming at the price of environmental protection? Pitting inclusion against climate justice is a no-win undertaking. With the legacy of colonial resource extraction continuing through “data colonialism” practices to build AI-based tools, we need a concerted global effort to build digitally inclusive futures alongside a sustainable, planetary one.30

AI Footprints

Data centers have a bigger carbon footprint than the aviation industry.31 Far from being abstract, invisible, and intangible, data is very much physical and energy-consuming. The cloud is grounded by cables and concrete. From sensors to streaming, our everyday digital tools demand a slice of the energy pie.

Data is a critical commodity in the global AI race among governments and industries alike. Tech companies compete fiercely for what is viewed as a scarce resource. Youth in the Global South become data mines in low-rights environments where businesses can operate without the burden of the privacy regulations that exist in the West.32 To stay competitive in the data cold war with China, US companies go elsewhere to sharpen AI, improve cryptocurrencies, experiment on the blockchain, and develop new products and services that can be sold in wealthier markets. These exploitative actions come at an added environmental cost. Worldcoin is a case in point.

Sam Altman, best known as the former CEO of OpenAI, ChatGPT’s parent company, cofounded Worldcoin to build the largest biometric identity system and financial network as a public utility, “giving ownership to everyone.”33 He promises digital democracy—nothing short of radically making the world into a better place through tech. Altman envisions a postnational and postcapitalist world where all people on the planet can collectively enjoy the benefits of AI. Worldcoin uses a specially designed chrome orb that resembles a black crystal ball to collect iris scans in exchange for “free” coins.

Collective ownership demands individual investment in the form of personal biometric data. On the ground, however, an investigative team from MIT Technology Review discovered jarring practices.34 They interviewed thirty-five users, recruiters, and workers in six countries—Indonesia, Kenya, Sudan, Ghana, Chile, and Norway—and observed the user onboarding process at a registration event in Indonesia. The team interviewed social and tech experts and discovered major privacy violations as Worldcoin scanned hundreds of thousands of eyes, faces, and bodies in twenty-four countries, the majority of which were in the Global South. Web 3.0 experts expressed serious concerns about the security of the orb and the biometric data because of the single-identity goal—the opposite of the decentralization that defines blockchain technology. To build privacy, Worldcoin broke privacy.

Crypto altruism comes at a significant carbon cost. In the last decade, three hundred million people have begun using cryptocurrencies.35 This cryptomania is accompanied by energy-intensive Bitcoin mining that is equivalent to a small country’s electricity consumption on an annual basis. With the Russian invasion of Ukraine sending energy prices soaring across the world, many countries are tightening the rules. China’s crackdown on the crypto industry has sent Asian Bitcoin nomads to seek alternative homes for their hardware, including in China’s nemesis—the United States. Bitcoin miners look for predictable regulation, stable relations with governments, and affordable power.36 The search for a hospitable turf seems to be getting harder. Their startup energy demand is close to that needed to power downtown Dallas, making it politically contentious even in freewheeling Texas.

Bitcoin Babushkas

In the crypto-against-carbon debate, perceived value is key. Crypto enthusiasts defend themselves by arguing that they aim to dismantle traditional financial empires that have long been “too big to fail.” Crypto is not merely about creating a new global currency.

Banking systems need a radical overhaul. In 2023 alone, cascading collapses and the crises of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and Credit Suisse remind us only too grimly that the financial system needs a new, responsible, ethical design.37 Moreover, the WEF tells us that pitting carbon against crypto is a privileged Western worldview.38 The WEF underlines that 80 percent of the world’s population has limited freedoms and little access to stable economic systems. “Bitcoin babushkas,” grandmothers in Russia, drive mining to protect their family’s savings.39 Young Nigerians see Bitcoin as a symbol of protest against the redesign of their currency, the naira, which became a political Band-Aid applied to Nigeria’s economic crisis.40

For people in Kenya, Venezuela, and Brazil, crypto is a safer bet than traditional currencies. They have little choice but to adopt crypto as they desperately seek to preserve their savings, receive remittances, purchase basic goods, and keep their businesses alive through basic fiscal transactions. This is a big reason why emerging markets continue to rank as leaders in the grassroots adoption of cryptocurrencies. According to the 2022 Global Crypto Adoption Index published by Chainalysis, setting aside the United States, Vietnam, the Philippines, India, and Ukraine lead the rankings.41

The Global South’s crypto uptake is more reflective of the failure of the state and the market than it is proof of crypto’s superiority. Crypto’s volatility and instability doubly punish those already suffering from few options. We need independent global watchdogs to ensure that speculative technologies do not speculate at the expense of those most vulnerable. Promoters of innovations like Worldcoin need reminding that the process matters as much as the product and requires building regulation, governance, and enforcement at a global scale.

Imagined affordances of security, accountability, and trustworthy intermediaries need the boring essential bureaucracies to transform aspiration into reality. Otherwise, new technologies will offer false hope to those deprived of legitimate options. The value of energy use is as much determined by culture as it is driven by carbon. How, then, do we build a shared value system that puts the planet and societal equity on par for mutual flourishing?

Part II: Culture of Collectives

The power of collectives manifests through a critical mass of people exercising agency and not merely through the cumulation of people and data. It takes an imaginative reengineering of templates, codes, and labels to redefine power relations through the force of numbers.

Engineering Bio-empathy

Templates are the litmus test of our times. What we choose to keep in and leave out says something about the stories we want to share. When you crack the code, you crack the culture embedded within it. Values dictate a variety of ways in which we can construct a story, justify a practice, and mobilize an action.

“If thinking were easy, more people would get their kicks that way.” This was the byline for Alternatives, a Bengaluru-based critical- and creative-thinking center set up in the early 1990s. I remember reading their cryptic advertisement for a workshop in the Deccan Herald as a teen growing up in India. It promised abstract possibilities of storytelling to change narratives. I liked not knowing what I was getting into. I was a teenager, after all. Their center was beautiful chaos, with posters from US activist Ralph Nadar, public intellectual Noam Chomsky, and naturalist Henry David Thoreau. It had a ’60s vibe in the colors, codes, and curated slogans in designer fonts scattered across rooms.

Only five of us had signed up for this Bengaluru-based workshop. The organizers took us to Cubbon Park for our first exercise and told us to imagine being marooned on an island. Our new tribe would need new rules of engagement between ourselves and with the natural ecosystem around us. It was the first time I was made to account for nature in thinking of society. The group’s default mindset was instrumental. We devised a plan of natural extraction, a template that became the basis for our social design.

As architect Indy Johar remarked at the Design for Planet Festival, “Everyone and everything is entangled. . . . As designers we need to take responsibility for entangled values.”42 To build templates with bio-empathy, it helps to recognize that we are stewards and not owners of the nature that surrounds us.

A decade later, I was hired by PlanetRead, a Puducherry-based nonprofit organization in south India. They sent me to work in Kuppam, a rural town in Andhra Pradesh, for a year. My job was to execute a World Bank–funded project on “karaoke for social change” using same-language subtitles to sustain recently acquired literacy skills and bring about social change.43 During that time, my team and I built a repository of folk songs for YouTube. It turned out that folk songs were not naturally suited to the audio cultures of YouTube. For one, they could go on for hours, especially at village festivals. Their instrumentals, pitches, and lyrics were not in sync with the acoustics of Tollywood or Bollywood. In addition, folk content was either too religious or too political to be considered “pop.” We designed a template to make the rural palatable to the urban, until it resembled a convenient fiction.

The Power of Labels

In a data-driven world, labeling practices organize the knowledge that shapes our thoughts and feelings. The father of UX research, Don Norman, has mainstreamed the eco-friendly design approach by advocating that designers shift from being “unintentionally destructive to being intentionally constructive.”44 This includes critically examining how we label people, animals, and things. For instance, Norman points out that how we choose to label specific plants as “weeds” and certain insects as “pests” has little to do with their intrinsic value. This arbitrariness assigns plants and animals a value that dictates the amount of empathy they will receive.

This treatment can go both ways. Through relabeling we can retell a story. In my book The Leisure Commons, I applied the metaphor of public parks to reveal the underlying design structures and ideologies that shape the internet.45 I used the label “corporate parks” to highlight the growing privatization of the internet. I used “fantasy parks” to emphasize the branded empires of sponsored digital spaces we play within and “walled gardens” from the eighteenth century to capture the enclosures of public parks, drawing parallels to the closing of open web architectures.

Such entangling of histories and geographies are needed to remind us that what we value—our freedoms, play, generosity with each other—are not unique to a point in time or to a particular culture or group.

We Are All Animals

Labels of care require disrupting clusters and categories that people have come to believe are normal. Retraining datasets needs constant guidance, nurturing, and a roadmap to build and sustain empathy. The Internet of Animals author Deborah Lupton is quick to point out that Western cultures have long labeled humans as separate from and more than animals, when in reality, “people are animals too, however much many of us like to forget or deny this reality.”46 The repositioning of humans as animals may generate more empathy for animals.

By taking this perspective, consumers may experience moral outrage about the unprecedented scale of factory farming and the culling of millions of animals to safeguard human health. Recognizing the “speciesist bias in AI,” certain species being coded with less value than others, can help build solidarity across species.47 Image recognition software uses commodity terms such as hog and livestock for pigs. Food terms populate image databases where fish are found as angler trophies rather than in their natural habitat.

While these demeaning and devaluing terms can negatively influence how consumers relate to certain species, a positive spin can be just as damaging. Trained datasets portray birds in natural environments when only one-third of all living birds exist in the wild. Cows, pigs, and chickens are shown in free-range environments even though the majority of them are in factory farms.48

Lupton conducted an online survey about animals and digital care and asked her respondents an open-ended question about the kinds of design they would like to see to help them better understand and care for animals. Many of them suggested an app to help them with their care routines for pets: reminders to walk, feed, change water, deworm, vaccinate, groom, and perform other such mundanities gained prominence as respondents envisioned their ideal care app. While some found it desirable to track their household animals’ every move via smartphone, most participants wanted a new platform to help them understand animals better—software and devices to “translate the thoughts, feelings and needs of their pets and better communicate with them.”49

Labels stick when they fit into a larger and more compelling story. Storytelling as a tool and technique comes with a track record of helping us relabel ourselves more humbly in the larger natural ecosystem.

Part III: Culture of Subsistence

At the core of subsistence is the value of diversity. Subsistence agriculture has long illustrated the advantages of diversifying our ecology for mutual flourishing and regeneration of soil and produce. Women have led this movement and continue to do so, decentering the paradigm of capitalism and emphasizing that of care. We must adopt this worldview if we are to recode our way out of the climate crisis.

Carbon, Code, and Culture

Software without stories is a body without a soul. Many of us feel our phones are extensions of ourselves. What stops us from feeling the same with nature? By transforming a bionic self into an eco-self, nature and technology can cohabit in worlds of our making. This transition is no easy task. It demands fresh narratives, new worldviews, and alternative actions.

South African anthropologist Rosa Boswell explains how oceans shape people’s identities through African storytelling, or what she calls “blue heritage.”50 She and I were part of the April 2023 cohort of fellows at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio residency, which brings together artists, writers, activists, policymakers, and scholars from diverse disciplines to work on their projects in Bellagio, Italy.

As part of its tradition, residents give evening talks about their work and share worlds of intellectual habitation. Boswell’s talk on South African Indigenous narratives on nature and culture came at an opportune time as I wrote this chapter. She brought entangled values to life when connecting the desert and the ocean in Namibia. These seemingly unrelated topographies are inextricably linked as southwestern winds from the ocean push fog into the desert, giving life to what would otherwise be a deeply hostile environment. The Namibian desert enjoys the status of a world heritage site as over half of the animal species found in its dunes do not exist anywhere else in the world.51

Stories from communities that live inland and at the ocean capture a deep understanding of the interrelatedness of things, animals, and places that can be transposed to other spaces of inhabitation, including our digital worlds.

All Flourishing Is Mutual

The Amazon is a complex material ecosystem and a metaphor for design thinking in an ecological way. Social innovation, climate justice, political storytelling, and design can collectively serve a posthuman perspective if we remind ourselves that “all flourishing is mutual.”52

“People do not confine themselves to landscapes,” says Boswell when speaking of constructing identities; neither does our communication with our smartphones and digital platforms. Every email we write, every song we stream, every picture we upload tells a story in space and time. Batteries that power our smart devices are entangled with the mining of minerals that go into their making and result in dead yaks in the Tibetan River.53 Electric cars that promise a clean future are built on the dirty politics of backbreaking labor and induce drought in the so-called lithium triangle of Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile.54 Lithium mining in Chile consumes 65 percent of the region’s water, driving people and animals elsewhere. Cobalt, another critical ingredient for electric vehicles, brings cascading environmental and human damage as it demands extensive manual child labor in what are euphemistically labeled “artisanal mines.”55

The computing cloud is brought down to earth in data centers and cooled by bodies of water around them. Environmental activist Teal Lehto remarks that we need to instill an “ethic of water conservation in every industry” for the digital to be sustainable.56 Financial geographer Dariusz Wójcik connects the dots through an “atlas of finance,” drawing out the global political economy of green finance.57 Maps tell stories of where data centers are built, global labor is recruited, minerals are extracted, and devices are manufactured, and of where hardware goes to die. The catchphrase “follow the money” gains renewed salience in this greening endeavor.

What Boswell does with the ocean, ecological anthropologist Eduardo Kohn does with the forest in his book How Forests Think.58 His four years of ethnography among the Runa of Ecuador’s Upper Amazon reveal intimate physical and spiritual encounters. Kohn compels us to recognize that “seeing, representing, and perhaps knowing, even thinking, are not exclusively human affairs.”59 The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ strategic storytelling expert Lauren Parater cautions aid agencies to keep in mind that when constructing new designs, policies, and imaginaries, they need to equally attend to the “destruction, removal, and defuturing—or the reduction of possible futures—it creates in its wake.”60 She advises them not to forget what is lost when they celebrate what is gained.

Entanglements happen not just with values and geographies but across generations as well. We inherit systems, norms, and codes to live by, often by brute force. In correcting the past, we face the challenge of what needs to be kept and what needs to be discarded.

Monocultures of the Machine

Eco-feminist Vandana Shiva, in Monocultures of the Mind, accused Western development organizations of imposing their infrastructures, policies, and priorities on other societies, threatening biodiversity and self-generated solutions from below.61 Today we need a reminder as algorithmic structures and climate-based solutions take a similar approach. In channeling energies toward green designs, practitioners and policymakers need to go beyond the instrumental logics of top-down innovations such as the green revolution.

The green revolution was an innovative technocratic solution to world food shortages in the 1970s. This agricultural reform significantly reduced poverty by embracing modern techniques of high-yield seed varieties, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, controlled irrigation, and mechanization. However, these reforms have indisputably reduced biodiversity through monocultural production.62 Over the decades, we have seen its failures reflected in farmers’ high debt levels, pesticide dependence, degraded soil quality, and waterlogged deserts. Today’s singular solution can become tomorrow’s more complex problem.

In the data economy we face a new monocultural challenge. In 2022 two behemoths—Meta in the United States and Reliance in India—entered a partnership to mediate the food supply chain.63 This corporate synergy could translate to totalizing control over retail production and distribution by combining user data in ways that could threaten market diversification. Big projects of techno-utopian scale signal little trust in people. These consolidations solve problems of inefficiency while exacerbating problems of unfair competition, poor compensation, or even lack of cooperation with those experiencing these changes firsthand—the farmers.

Part IV: Culture of Repair

The virtue of repair is that it mends not just things but also trust. If we see our relationship with everyday things as long-term and meaningful, then we will design in ways that allow for repurposing, auditing, and fixing things in ways that can renew and regenerate. This demands a recognition that we are interconnected and live in a system of wonderful complexity, where repairing a part can change the whole.

Generation Lost

In her travels through rural China, activist-artist Xiaowei Wang speaks of a blockchain utopia entering farming communities.64 Ledgers and decentralized records for proof of validation are messiahs in this futuristic technoscape. Even the chickens go through proofing. Wang has found several AI-enabled organic chicken farms where chickens have tamperproof ankle bracelets with unique QR codes to track their steps, weight, location, and diet. As Chinese customers’ trust in the market falls, these scans rise so customers can “bond with their dinners.”65

AI generates a new intimacy with our food. Though rural farming was once invisible and inaccessible, today we have it in our living rooms and on our tablets. FoodTech venture capitalist firms like Bits x Bites promise a shift in trust in food safety from the social to the technical. These impressive and futuristic-sounding efforts do little to address a problem the agricultural sector faces worldwide: few farmers want to farm anymore.

While venture capital sees profit, the new rural generation sees loss. Much of what plagues this sector has little to do with tech and more to do with the fair distribution of profit, diversified produce for regeneration, and structured resilience for farmers in terms of adequate safety nets if they are to experiment and invest in new tech for old problems.

The Sachet Lesson

The late business guru C. K Prahalad and his 1990s “bottom of the pyramid” model convinced companies and governments to look at the global poor as a legitimate market.66 He argued that if we shifted our perspective to what these populations need, we could profit through economies of scale and do good at the same time.

Prahalad’s inspiration came from the shampoo sachets of 1970s India. Chinni Krishnan, a farmer turned entrepreneur, realized that he could make shampoo affordable to rural consumers by selling it in small packets instead of big bottles.67 This simple innovation sprang from observing a stark difference between middle- and lower-class consumer groups—while middle-class workers enjoyed monthly salaries, lower-class workers were daily wage laborers. This led to a radical overhaul of the Indian consumer market.

The sachet principle became a global market dictate for multinationals like Unilever and P&G to serve the Global South. It was a win-win solution for people and businesses but not for the environment.68 Being small, these packets fell through the cracks of recycling systems. They clogged drains, polluted water sources, littered the streets, and ruined pristine landscapes. Landfill usage was exponentially increased by this everyday wastage. Worse, it created a disposable culture among communities that historically would repair, recycle, and reuse. Going against plastic is no easy feat. Plastic is durable, inexpensive, heat and water resistant, and essential to billions of marginalized groups in difficult social conditions. The core failure of the bottom of the pyramid model was that it did not take into account that things are connected, which can result in a cascading effect of solving one problem but creating another, even larger one.

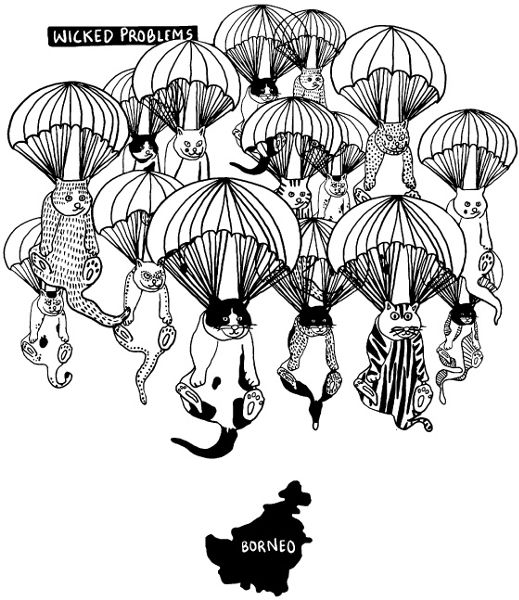

Parachuting Cats

Once upon a time, fourteen thousand live cats were parachuted into Borneo Island in Southeast Asia.69 In the 1950s the World Health Organization (WHO) tried to help the Dayak people of Borneo eradicate malaria in the region. Their quick-fix solution was to send helicopters to spray dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), an insecticide, over the region. In the short term, it worked. The mosquitoes died. Over the long term, however, it started to poison other insects and moved up the food chain, killing most of Borneo’s cats. This led to an explosion of rats and bigger problems of typhus and plague. The WHO had to respond immediately, taking the desperate measure of parachuting cats into this island at an enormous cost to control the rat population. Two decades later the United States banned the use of DDT, recognizing that it causes more harm than good.

What we have here is “a wicked problem,” an issue that lacks a clear solution due to its multifaceted nature and diverse stakeholder perspectives, as well as the emergence of new and often bigger challenges during attempts to tackle an existing one.70 To address a wicked problem and institute sustainable change, organizations need to recognize the interrelationship of people, places, and practices. We need to apply this type of thinking to some of the biggest challenges we face today, such as pandemics, climate change, and data governance. The common factors across the board are the intrinsically global nature of these problems and rising inequality where the negative impacts are felt most by marginalized populations. In the case of making cyber policies fair and just, we need to consider that data is inherently social—our everyday thoughts and feelings are not just extensions of ourselves but of how we are members of a global society. When we embark on problem-solving, we need to consider the humanity of the culture of code that steers us toward a joint future.

It’s Not a Contest

To ensure that we do not pit equity against sustainability, we need to invest our energies in finding solutions that address both values simultaneously. In 2022 an all-female team of students won the Earthshot Prize for coming up with an alternative to plastic packaging.71 Using seaweed cuts gas emissions by 36 percent, keeps profits at 41 percent, and reduces plastic use by 95 percent. The team members came from different disciplines—law, international policy, and finance—and saw plastic waste as an intrinsically global issue. Moreover, they sought to add value and not just solve a problem as they outlined new opportunities for livelihoods for coastal communities threatened by climate change.

Repairing our current systems has limits. While the culture of repair is commendable and often necessary, it still needs to work with that which is inherited, broken, fragile, and volatile. Designers, thinkers, and doers must remind themselves that in the process of creating a new tool, they may be creating a new legacy of practice. There is a deep responsibility in building new templates, codes, and labels that must work in tandem to ensure humanity’s and the planet’s flourishing. These become the building blocks on which the ecosystem of future life will rest.