King Philip II received a much-awaited shipment in spring 1576. The sender was Francisco Hernández, a physician who had spent more than five years researching and writing about the flora and fauna of New Spain. The cargo included sixteen large volumes with text and images describing and depicting more than three thousand plants, as well as live and dried specimens.1 It also included “Historiae animalium et mineralium novae hispaniae” (History of animals and minerals of New Spain), a copiously illustrated Latin treatises on quadrupeds, birds, reptiles, insects, and aquatic beings, and pelts, feathers, and dissected animal bodies.2 The king found the illustrations so pleasing that he displayed several in his quarters in the Escorial palace, where they dazzled visitors.3 Reflecting the excitement spawned by the “Historiae animalium” in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, one visitor marveled at “all of the animals and plants that can be seen in the Occidental Indies in their own native colors . . . the caiman, the spider, the snake, the serpent, the rabbit, the dog and the fish with its scales, the most beautiful feathers of so many different birds, the claws and the beak.” He exclaimed at “the greatest delight” one felt in looking at them.4

The accompanying text generated almost as much delight and excitement as the beautiful paintings. Even though, much to his dismay, Hernández failed to publish his “Natural History,” it circulated in manuscript and eventually made its way into print in the seventeenth century. The European scholars who viewed the images and read the texts responded so strongly because of their epistemological novelty—a novelty produced by the entanglement of Indigenous and European epistemologies. Scholars have long recognized that Hernández relied on Nahua labor and knowledge to write and illustrate his natural history. However, the full extent to which Indigenous expertise and labor contributed to the natural history has gone unnoticed, largely due to Hernández’s disavowal of it. Yet, like the footprints that dotted their pictorial works, Nahua experts left their marks on every page of the “Historiae animalium.” By finding, identifying, and connecting these marks, it is possible to offer a more complete account of the production of this seminal zoological text. By centering “Historiae animalium” in the history of the natural sciences, I am contributing to an on-going, collective effort to make visible the Iberian world’s centrality to the momentous epistemological changes of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries traditionally designated the “Scientific Revolution.”5 The reconstruction of the inception, production, and reception of the “Historiae animalium,” however, reveals an even larger erasure in the history of early modern science—that of Indigenous knowledge, and, more precisely, its appropriation and disavowal by European colonizers.6 It is no small paradox that what made this knowledge so attractive to colonizers such as Hernández was the radically different way Indigenous people interacted with nonhuman beings, and, therefore what they perceived and understood about them.

THE ORIGINS OF the “Historiae animalium” lie, in part, in a 1569 edict appointing Hernández “protomédico of the Indies.”7 A subsequent 1570 royal decree instructed the physician to “go to the Indies and consult all the doctors, medicine men, herbalists, Indians, and other persons with knowledge in such matters . . . and thus you shall gather information generally about herbs, trees, and medicinal plants in whichever province you are.”8 Hernández was a logical choice for this position and assignment. He had studied at the prestigious University of Alcalá de Henares, and had embarked on ambitious translations of the works of Pliny and Aristotle. He also had practical experience overseeing botanical expeditions in Andalucía, and he had served as a royal chamber physician. After a short stay in the Caribbean, Hernández arrived in New Spain in February 1571. For the next three years, he was mostly itinerant, covering vast distances with a large retinue, reaching Querétaro to the north, Guerrero to the west, the Tehuantepec Isthmus to the south, and Gulf Coast regions to the east. During his travels, Hernández usually lodged at Franciscan monasteries or friar-run hospitals. Reflecting back on these travels in the years after he returned to Spain, he, like Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, cast himself as a heroic researcher. He boasted of tolerating strange foods that “took a long time to get used to,” extreme weather (“the intense heat, and the great cold”), and challenging travel conditions like “impassable mountains, rivers, swamps, vast lakes, and expansive lagoons.” He particularly emphasized the dangers and discomforts he faced because of nonhuman creatures, both large and small. Hernández reported encountering “monstrous creatures swimming in the lakes, which have stomachs vast enough that they can swallow men whole” and “thousands of nasty insects everywhere that lacerated my tender skin with their bloodsucking stings.”9 For the last phase of his stay in the Americas, beginning in March 1574, the physician lived in Mexico City. There he organized and revised his data, experimented with materia medica, and tended to patients in the Hospital Real de Indios and continued his research on animals and plants. Sharing his lodgings with numerous caged birds provided by trappers, Hernández observed their behavior and listened to their mellifluous songs and garrulous chattering,

By 1576, Hernández was past his deadline. The impatient king had responded to the request for (another) extension by writing “that this doctor has frequently promised to send these books, but he never does” and so instructed the viceroy of New Spain to order the naturalist to “pack them up and send them on the first ship for safe keeping.”10 And so, in late March, a ship left the port of Veracruz bearing Hernández’s five animal treatises totaling 414 chapters, ranging from a few sentences to several pages in length. The treatises concerned quadrupeds (40 chapters), birds (229 chapters), reptiles (58 chapters), insects (31 chapters), and aquatic animals (56 chapters).11 In an apologetic letter to King Philip, Hernández explained that the works were still in draft form, and thus “not as clean or as ordered,” as he intended: “I am still now finishing writing what more there is to be discovered and am perfecting the books.”12 He kept working on the natural history during his remaining months in New Spain, bringing another twenty-two volumes of manuscripts when he returned to Spain at the end of 1577.13

From Hernández’s perspective, his project ended in failure because he never saw it in print. Despite—or perhaps because of—his enthusiasm for the illustrations, Philip II did not give permission for the book’s publication. The royal rationale for this decision remains obscure. Some scholars believe that it was prompted by pique over repeated delays, others because the elderly physician was in failing health, or perhaps because Hernández strayed from the medical objectives of his mandate by discussing other characteristics and uses of American plants and animals. The king commissioned another physician, the Neapolitan Antonio Nardo Recchi, to make a “useable” digest of the natural histories, titled “De materia medica Novae Hispaniae: libri quatuor” (Materia medica of New Spain in four books) completed between 1580 and 1582.14

THE TRUE NOVELTY of “Historiae animalium” becomes apparent only in comparison to most of its precursors, including Oviedo’s natural histories. Like Oviedo before him, Hernández modeled his project on that of Pliny. In a letter to Philip II, Hernández referred to the entirety of this opus as “the natural things of New Spain (las cosas naturales de la Nueva España) that I am describing, experimenting, and drawing,” and elsewhere as “the history of natural things of the Indies,” thereby making explicit his ambition to pursue the Plinian project in the Americas.15 Like Oviedo, Hernández emphasized that his work was based on firsthand, sensory experience. But Oviedo’s natural histories included 61 animal entries, less than a fourth of the number that appear in Hernández’s work.16 Moreover, the animal entries consist almost exclusively of text: Oviedo’s faunal illustrations were limited in the printed works to rudimentary woodcuts of a manatee and iguana, despite the fact that he had many more drawings in his manuscripts.17

For the illustrations, Hernández clearly took inspiration from the natural histories created by authors in northern Europe. His models were those found in the works on animals, birds, and fish by the renowned humanists Pierre Belon, Guillaume Rondolet, and, above all, Conrad Gesner’s Historiae animalium (1551–1558),18 notwithstanding the fact that works by Gesner, a Protestant, were among those prohibited by the Inquisition.19 These scholars’ influence can also be seen in the organization. Like Gesner, Hernández followed Aristotle for his subdivisions rather than those found in Pliny or medieval encyclopedias. But the “Historiae animalium” also diverged from these antecedents in important ways. The natural histories of Gesner, Belon, and Rondolet had different epistemological foundations than Hernández’s work. The former were, above all, humanist philological projects, as Brian Ogilvie has demonstrated. These humanists saw their primary task sifting through and collating the work of prior “authorities,” a process of “textual collection and comparison” rather than composing entries based on their own empirical observations.20 The divergence of “Historiae animalium” from earlier European natural histories can be attributed, in large degree, to Hernández’s reliance on Indigenous expertise.

BEGINNING WITH THE seminal work of Germán Somolinos d’Ardois, scholars have long emphasized the contribution of Indigenous labor and knowledge to the “Historiae animalium.”21 Indeed, the 1570 edict commanding Hernández to interview “old Indians” and Indigenous healers acknowledged that this expertise was imperative for the project.22 It is well known that the Spaniard relied on Native people to translate for him, guide him, carry him in litters, capture live animals, and collect specimens.23 However, the full degree of his debt to Indigenous labor and knowledge has not been fully appreciated, largely because Hernández himself was loath to credit it and sometimes actively concealed it.

The influence of Indigenous expertise on Hernández’s natural history project likely began even before the protomédico set foot in the Americas due to the intersection of Hernández’s work and that of the Tlatelolco scholars.24 In 1569, the Tlatelolco scholars had completed a draft of the twelve Nahuatl books of the “Historia universal.”25 The lead author, Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún, sent the manuscript to the leaders in his order, but the response was not what he had hoped. Some of the order’s leaders thought the project was worthy of “much esteem” and merited additional funding to bring it to completion; others opposed continued support. Sahagún later wrote that they were hostile to the project because its associated costs violated the order’s vow of poverty. Nevertheless, it seems even more likely that this opposition stemmed from anxieties that the project would memorialize idolatry rather than eradicate it, as Sahagún and his supporters claimed. After the “Historia universal” fell out of favor with the Franciscan leadership, Sahagún decided to seek patronage elsewhere. He sent a “Breve compendio” (Brief compendium) to the Pope, hoping that he might get papal sponsorship for his project. Hedging his bets, he wrote a “Sumario” (now lost), which he described as “a summary of all the Books and of all the chapters of each Book and the Prologues wherein all that is contained in the Books is briefly stated,” and persuaded well-connected Franciscan allies to present it to the president of the Council of the Indies in Spain. In the short run, neither strategy panned out. In the words of the friar, “nothing happened to the texts for the next five years.”26 This is not entirely true. In fact, Sahagún was required to submit the manuscript to his order for review, and copies were dispersed among different Franciscan monasteries in New Spain. Furthermore, the “Sumario” arrived in Spain soon after the king had appointed Hernández to his bio-prospecting mission. It is likely that Hernández became aware of the “Historia universal” shortly before he left for the Americas, and the physician likely carried Sahagún’s “Sumario” (or a copy of it) when he disembarked in summer 1570.

Hernández’s decision to include animals in his natural history may be a result of his exposure to the Nahuatl “Earthly Things” (Yn ixquich tlalticpacyotl) and to the Indigenous experts he met during his travels. The instructions that accompanied the royal decree compelled Hernández to collect botanical information. However, the protomédico’s correspondence with Philip II makes clear that his own understanding of the project had exceeded its original medical-pharmacological scope. In September 1572, he wrote, “I have so far drawn and painted three books full of rare plants”—in fact the illustrations were made by Nahua artists as discussed below—“most of them of great importance and medicinal virtue, as your Majesty will see, and almost two more [books] of terrestrial animals and exotic birds, unknown in our world, and I have written a draft of whatever could be discovered and investigated about their nature and properties, a subject on which I could spend my entire life.”27 By March 1573, Hernández had completed a volume containing illustrations of “200 animals, all exotic and native to this region” as well as text describing “the nature, climate, of the places to which they are native, the sounds they make, and their characteristics.” While his aspirations to be the Pliny for the “New World” might partly account for the creep in his project’s scope, he also explicitly credited Indigenous knowledge in his private correspondence, though not in the manuscripts he hoped to publish. In private communication, however, he employed greater candor. For example, in a letter to Philip II, he acknowledged that this knowledge came from “Indians, whose experience stretches over hundreds of years here.”28 The published manuscripts and drafts of “Historiae animalium” offer clues to his itineraries while researching animals. The extensive discussion of waterfowl suggests Indigenous contacts in Tlatelolco-Tenochtitlan and Texcoco, as he often mentioned these sites in reference to water birds.29 His reliance on Indigenous knowledge also appears in lexical traces; almost all of the entries for animals native to Mexico employ Nahuatl names (see figs. 11.1, 11.2, and 11.3). In most cases, the Nahuatl term was presented as the primary signifier, followed by a literal translation, often revealing the Nahua practice of naming animals after defining features related to a distinctive aspect of their appearance, vocalization, or behavior.

One of the most foundational contributions of Nahua scholars to the “Historiae animalium” can be found in Hernández’s obvious though unacknowledged use of “Earthly Things.”30 He likely saw a draft of the “Historia universal” during one of those stays with the Franciscans, as copies of the manuscript were dispersed among different Franciscan houses.31 A comparison of the “Historiae animalium” and “Earthly Things” reveals that some details for entries on the monkey and coyote concur to such an extent that coincidence is implausible.32 Moreover, Hernández’s chapter on the quetzal is mostly a Latin translation of the entry penned by the Tlatelolco authors in Nahuatl.33 Hernández’s use of this Nahuatl manuscript is significant as it displays the influence of the Nahua authors on his manuscript, and suggests that these authors worked directly with him. Because the Spaniard knew little Nahuatl, he depended on Indigenous interpreters and translators. In a letter dated March 20, 1575, among the many in which he asked for an extension of his due date, he asserted that he needed extra time so that “an Indian who is translating my books into Mexican (e.g., Nahuatl)” could finish them, and in another letter he referred to the task of “translating [drafts] into Spanish and Mexican.”34 From this, we can infer that his collaborators included one or more people capable of translating from Latin into Nahuatl. This suggests that the translations were made by one or more of the Tlatelolco seminarians, perhaps Antonio Valeriano, who was renowned for his mastery of Latin.35

I believe that in addition to their work as translators, editors, and perhaps even coauthors of “Historiae animalium,” the Tlatelolco scholars also conducted research under the auspices of Hernández.36 The evidence for this scenario comes from a comparison of the “Historiae animalium” with the final version of “Earthly Things”—book 11 of the Florentine Codex. The latter contains forty-three “new” entries (i.e., not present in the 1565 draft).37 Two are quadrupeds: the tlacaxolotl (tapir) and the tzoniztac (perhaps a weasel-type animal).38 These entries include details that suggest influence rather than coincidence—in other words, the overlap between the new entries in the Florentine Codex and those in the “Historiae animalium” seems too precise to be a function of independent reporting. Both texts relate, for example, a belief that a chance encounter with a yellow-headed tzoniztac augured impending death, whereas an encounter with a white-headed one foretold a long yet impoverished life.39 The entries for the tapir offer the detail that the animals ate and then defecated cacao beans, which were then foraged for by commoners.40 The remaining forty-one new entries in the Florentine Codex are about birds. Many were either waterfowl who lived near Lake Texcoco (27) or raptors (9).41 These entries reflect, respectively, Hernández’s focus on the marshland birds that were in proximity to his base in Mexico City, and attentiveness to his royal patron’s interest in falconry.42 Moreover, the new raptor entries embedded Spanish terms within the Nahuatl text, such as “alcón” (falcon) and “gavilán” (hawk).43 Another clue that the new entries were added during or after the Nahua authors worked on Hernández’s project is that they often introduced redundancy into the text. The Florentine Codex included, for instance, a short entry for a raptor known as “tlhoquauhtli” [tlhocuauhtli] that was in the early draft and then a new, longer entry for a bird of the same name. Likewise, the Florentine Codex had two entries for the pelican.44

If the new entries in book 11 resulted from research conducted under the protomédico, then they can shed light on the research methods developed by the Nahua scholars in both projects. A notable aspect of a number of the entries on marshland birds is frequent mention of atlaca, suggesting them as the source for the information about aquatic animals. The literal meaning of atlaca is “people of the water,” although Alonso de Molina translated the term as marinero (sailor or boat people), “gente malvada” (tough people); other contemporary sources suggest that it could be synonymous with fishermen.45 Thus, it appears to be an appellation for commoners who made their living from the water. For instance, the authors wrote in the new entry for the pelican (atotolin) that the bird “does not fly very high; sometimes the atlaca only chase it in boats; they spear it.”46 The atlaca also told the Tlatelolco scholars about the acuitlachtli, described as a creature with a head “like those of the forest-dwelling tecuani (people-eaters)” and the tail of a caiman who “lived there Santa Cruz Quauhacalco, where there is a spring.” “The heart of the lagoon,” he was held responsible for making the water overflow, the fish well up, and agitating the mud like an earthquake. In other words the acuitlachtli—seemingly out of place in the section on aquatic birds—personified the lagoon itself. The atlaca “can testify, for they saw [the animal] and they also capture it.”47 The scholars were able to use their local contacts in Tlatelolco to interview these knowledgeable locals, who were intimately familiar with the lake environment and the dangers lurking in its flood-prone waters.48

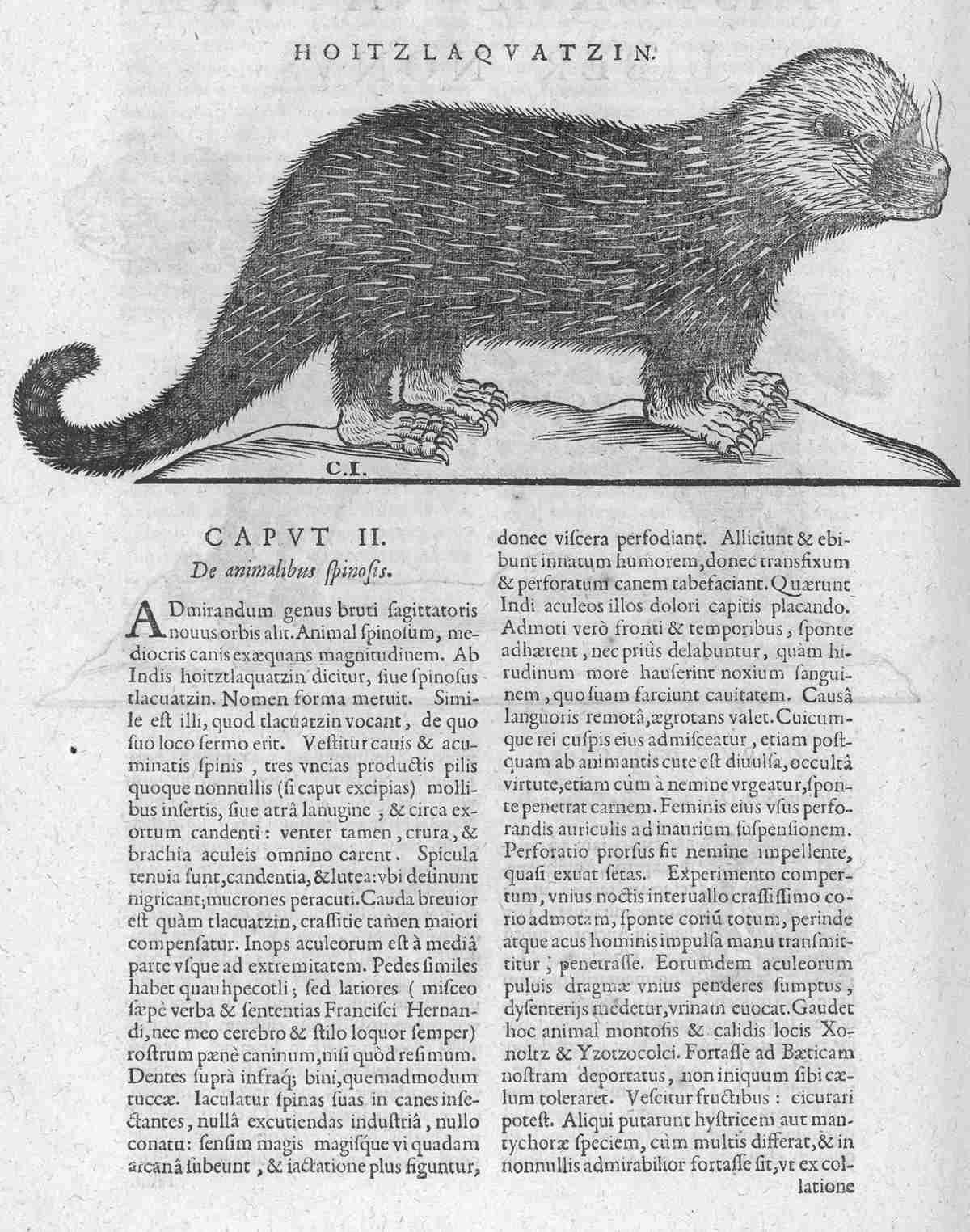

Given Hernández’s reliance on Indigenous expertise at every stage of the project, it is not surprising that much of the knowledge about animals transmitted in “Historiae animalium” was related to predation and familiarization. The details about animals’ appearances, sounds, tastes, and behaviors comprising the entries in the “Historiae animalium” are observations often derived, directly or indirectly, from these Indigenous modes of interaction. We have already seen how familiarization may have been a prerequisite for some of the most detailed descriptions of animals’ appearances and behaviors in the “Historiae animalium.”49 As discussed in Chapter 7, familiarized animals appearing in the treatise on quadrupeds include the raccoon (fig. 11.1), peccary, possum, porcupines (fig. 11.2), coati, monkeys, and squirrels.50 Among the birds were a woodpecker, tepetototl (Crax rubra), parrots, and songbirds who “delight with their song those who hear them.”51 Familiarized reptiles included the rattlesnake (fig. 11.3) and the tapayaxin (mountain horned lizard).52 This mode of interaction facilitated Hernández and the Nahua researchers’ access to live animals whose appearances—and behaviors—could be described in great detail.

Figure 11.1 Raccoon in Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae (Antwerp, 1635), p. 175. Reproduction courtesy of John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.

Predation also underpinned many descriptions. Such entries featured specific information about the manner in which people hunted, snared, fished, or otherwise captured wild animals. In the chapter on the caiman (“aquetzpalin or crocodile that others call Cayman”), Hernández observed admiringly that despite the enormity and ferocity of the animal, Indigenous children would lasso them by the neck and tow them to the shore.53 Hernández’s descriptions of the properties of animals’ flesh, bones, feathers, and fur were related to predation. He focused frequently on edibility and offered his opinions about flavor.54 Various parts of the “hoactzin” bird, for example, were used in remedies—the bones were used for pains caused by cuts, a smoke made from its feathers restored “reason” to those sickened by rage, and ashes made from feathers “admirably” cured victims of the “French disease” (syphilis).55 The feathers of the cozcaquauhtli (king vulture), were, according to Hernández, applied to ulcerous sores, and its flesh was cooked and fed to those suffering from them.56 He also mentioned prey whose bodies had medical, aesthetic, and sartorial uses. He noted the rabbit fur woven into tunics and cape and the peccary skin lining the inside of cloaks. Armadillo (ayotochtli) “related as much to war as to peace” for its tail could make blow darts and the shell was decocted for medicinal preparations.57 Moreover, Indigenous hunters provided Hernández (and his collaborators) with the specimens that often became the basis of his entries.

It is not only details about hunting practices and the appearances, behaviors, and habitats of prey animals that reveal predation’s constituent role in the “Historiae animalium’s” epistemology. This mode of interaction generated a mode of observation and description. The quetzal entry is exemplary in this regard. It is no coincidence that the description of the quetzal whose feathers were valued above all others for making ritual garments is the most detailed about coloring and shape. Nor is it a coincidence that it was the entry that Hernández chose to transcribe it in its entirety from “Earthly Things.” The significance of the quetzal entry is twofold: it reveals the authorship of the Tlatelolco scholars and provides a descriptive model for other entries. In other words, teixiptla helped transform the practices of natural history.58

The quetzal entry also reveals elements of cosmogrammatic logic that were likely invisible to Hernández—but not to his Nahua collaborators. A revealing divergence exists between the two surviving versions of “Historiae animalium,” the manuscript draft and the seventeenth-century print edition based on the Escorial manuscript that Hernández sent to the king. In the draft, the quetzal entry appears first among the birds, as it did in the 1565 draft of “Earthly Things.”59 However, the quetzal chapter appears second in the version that Hernández sent to Spain, following the chapter about the “hoacton foemina” (female heron).60 In both versions, the quetzal’s singular and supreme importance in Nahua sacred geography was conveyed by chapter placement, but the differences are telling. By putting the heron first, the Nahua scholars alluded to the Mexica’s origin story, in which the heron was the bird of Aztlan, the beautiful land associated with the western quadrant where they first attempted permanent settlement. The placement of the quetzal after the heron in “Historiae animalium” alludes to a particular central Mexican understanding of history, one that pays homage to migrating ancestors. In book 9 of the “Historia universal,” featherworking informants explained that during early Chichimec times, heron feathers were “precious” and “corresponded to those of the quetzal” as “they were used to make the forked heron feather device” with which “the winding dance was performed.”61 The juxtaposition of the heron and the quetzal is a way of signaling that the Mexica live in the center, at the crossroads of different biomes of Mesoamerica, for these are feathers of the birds of the East and the West. Given that Hernández, unlike the Tlatelolco authors, did not usually organize animals in accordance with Mexica priorities, this trace suggests the intentionality of the unnamed and barely acknowledged Nahua scholars rather than that of the protomédico employing them.

Importantly, Hernández’s lack of acknowledgment—or, more precisely, his disavowal—of his Nahua collaborators was a consistent feature rather than an accidental product of his method.62 Hernández’s acknowledgment of his dependence on Indigenous expertise and knowledge most often took the form of complaints, as when he lamented Native people’s unwillingness to comply with his requests for information or demands to share their arcane knowledge: “I will not speak of the perfidious confabulation of the Indians, the perverse lies with which they mocked me . . . nor the many times I confided in false interpreters . . . so that it is necessary to recognize the savage condition of the Indians, never sincere, reluctant to reveal their secrets.”63 Hernández disavowed their contributions partly because he was concerned about perpetuating and perhaps even reinforcing “superstitious” or even “idolatrous” beliefs, bodies of knowledge from which he sought to distance himself. In the chapter about the acitli (an aquatic bird—perhaps a western grebe64), Hernández discussed a belief “told by the Indians.”65 “They say,” wrote Hernández, that the duck “can summon the winds when pursued by hunters, making waves that overturn canoes and drown the pursuers”—something they do if the hunters don’t succeed in killing them after five arrows are shot. This belief is similar to others held by hunters that proscribe pursuing too aggressively those prey that elude capture or killing. The Spaniard scorned such “childish beliefs and lies,” attributing them to “the credulity and shallowness of these people.” For example, when discussing the cocotzin, which he identified as a kind of dove slightly larger than a sparrow, he scoffed at a local belief that, if it was cooked and fed to a woman without her knowing what she was eating, it would cure her of jealousy. Tellingly, he added, “The theologians can investigate whether this can be so.”66 In addition, he related a belief of the “Indians” that sighting the hoactzin augured misfortune, and that hearing the song of the cuapachtototl (one that resembled laughter) was a bad omen held “by the Indians before they were illuminated by the splendid light of the Gospel.”67 Hernández’s effort to remove information related to what he considered “childish beliefs” and “lies” reveals his anxiety about potential contamination by superstition or idolatry. The result was that most entries describe only appearance and behavior, leaving aside details related to cosmology. In this respect, the “Historiae animalium” lacks the magical and mythological references found in Pliny’s “Natural History” that he was simultaneously editing.68 Part of what would become known as “disenchantment” had its origins in Europeans’ efforts to appropriate Indigenous knowledge without assimilating their alleged superstitions.

IN 1671 THE paintings and drawings of animals and plants that Philip II displayed to distinguished visitors, along with the sixteen volumes of text, were destroyed by a fire at the Escorial palace. Three Indigenous men, Pedro Vázquez, Anton [?] and Baltasar Elías, made these bedazzling images while in Hernández’s employ. The protomédico expressed more appreciation for the artists who he trained to paint plants and animals than he did for the many other Indigenous experts who worked for him. The physician uncharacteristically articulated his high regard for them,69 going so far as to request that the king command some of his “Indian painters” to accompany him to Peru on a proposed but unrealized research trip.70 And though his letters reveal a reluctance to pay the Indigenous workers in his service adequately, he made provisions in his will to ensure that three of his painters received what he thought was proper compensation: “I desire that in the event that His Majesty does not recompense the Mexican painters in the amount that I requested, that to each of the three, namely Pedro Vázquez, and Anton and Baltasar Elías, to each or to his heirs be given thirty ducats from my estate.”71 Nevertheless, per his customary practice, Hernández also complained about these Indigenous artists, thereby revealing that he regarded their contributions as crucial. He wrote, “I cannot begin to count the mistakes of the artists, who were to illustrate my work, and yet were the greatest part of my care, so that nothing, from the point of view of a fat thumb, would be different from what was being copied, but rather all would be as it was in reality.”72 In the text of the “Historiae animalium” itself, Hernández alluded to the labor of these Indigenous artists, as in the entry for the hoactzin bird, “who lives in warm regions, such as Yauhtépec, (Oaxaca) and that rests almost always in trees that are next to rivers, where we saw it and made sure to hunt it and paint it.”73 Here and elsewhere, the fourth person both reveals and buries the contributions of his collaborators.

Despite the enormous loss wrought by the Escorial fire, we do know something about the images made by Vázquez, Anton, and Elías. Two of the seventeenth-century publications based on Hernández’s works—Nieremberg’s Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae (1635) and the Lincei Academy’s Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus (1648–51)—feature woodcuts made from the original paintings (figs. 11.1, 11.2, 11.3).74 The illustrations made for the “Historiae animalium,” like those in Gesner’s and other humanist zoological texts, privilege the ocular and, more specifically, the one-way gaze.75 It might seem obvious that an image emphasizes what can be known through the sense of sight, but it is possible for images to emphasize other forms of sensory apprehension. Images in a tonalamatl emphasize sound, with scrolls emitting from the mouths of people and other animals; smell, through the representation of flowers; and movement, through footsteps. The images in the “Historiae animalium” also exhibit what art historian Janice Neri called “specimen logic,” in which “objects” are removed “from their contexts and plac[ed] . . . against the blank space of a page for the viewer’s inspection.”76 It seems likely that Hernández showed the Nahua illustrators examples from Gesner, or the other humanist zoological books, so that they could depict animals in this pictorial mode. These images show the animal alone with minimal or no background elements.77 Sometimes they include a few elements to suggest a landscape, but they are generic and do not suggest interaction with other beings, as is the case with the raccoon (fig. 11.1). In the case of the porcupine (fig. 11.2) and rattlesnake (fig. 11.3), background elements are entirely absent. The images, even more than the text, are worlds apart from the animals (and other beings) painted in the tonalamatl and other postclassic artifacts. For example, the cosmograms depict animals within relational networks, showing connections among different forms of life (animals, plants, soil, water, sun). In contrast, the images in the natural history portray decontextualized, self-contained organisms.

Figure 11.2 Porcupine in Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae, (Antwerp, 1635), p. 154. Reproduction courtesy of John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.

Figure 11.3 Rattlesnake in Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae (Antwerp, 1635), p. 368. Reproduction courtesy of John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.

Even so, some traces of Indigenous pictorial modes survive in these images. The coiled posture of the rattlesnake is more reminiscent of late postclassic sculpture than the European tradition that tended to depict snakes while undulating rather than coiled.78 But perhaps the images’ biggest debt to Indigenous practices and beliefs about nonhuman animals is that of familiarization. It is no accident that the most naturalistic engravings with the most precise detail disproportionately depict animals that were also discussed as objects of familiarization, for example, the raccoon, porcupine, rattlesnake, possum, and peccary.79 It makes sense that the artists would render most vibrantly those animals whom they could draw from life. Although these naturalistic representations are stylistically European, they were made possible because the artists had close access to living animals. Paradoxically, the “specimen” images, even though they were deeply rooted in European aesthetic tradition and antithetical to postclassic Indigenous pictorial and epistemological conventions, were entangled with Indigenous people and modes of interaction. The drawings would have been impossible without the Indigenous artists whom Hernández trained and admired, or the practices that resulted from predation and familiarization that provided ample access to live and dead specimens. Thus the “Historiae animalium” was the result of the commingling of European and Indigenous epistemologies and the modes of interaction that underpinned them.

IT IS HARD to overstate the excitement generated by Hernández’s coproduced “Natural History of New Spain.” Although never printed, it became a sensation among literati in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.80 Well-known figures in natural history across Europe, including José de Acosta, Ulisses Aldrovandi, Carlos Clusius, and Johannes Laet, expressed, in both published remarks and private correspondence, their desire to see the works.81 Aldrovandi, the Italian polymath, for instance, was desperate to see the manuscripts and wrote to a contact whom he hoped could help get access to “the court of king Philip,” where there was “a truly regal book with paintings of various plants and animals and other new things from the Indies.”82 Before long, portions of the natural history began to circulate in print. In 1615, Francisco Ximénez, a physician and Dominican friar based in Huaxtepec (one of the places Hernández stayed during his travels), published a translation of Recchi’s digest in Mexico City.83 In 1628, the Lincei Academy in Rome (also a patron of Galileo) published a very limited print run of the Recchi digest in Latin, along with a lengthy commentary entitled “Animalia Mexicana.”84 Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, a Jesuit scholar at Imperial College in Madrid who had access to the volumes housed in the Escorial and the “drafts” that Hernández had retained for himself, extensively transcribed material from the “Historiae animalium” in Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae (Antwerp, 1635).85 And in 1649, the Lincei Academy published the entirety of the text of the “Historiae animalium” as an appendix in its massive Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus, seu, Plantarum animalium mineralium Mexicanorum historia.86 As already mentioned, both the Rome and Madrid publications featured woodcuts based on the original illustrations. Many more works published in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries transcribed or translated entries that first appeared in the “Historiae animalium.”

Another impact of the “Historiae animalium” was its emulation by other authors. Particularly important in this respect is the Dutch imperial Historia naturalis brasiliae (1648).87 Among its authors and sponsors was Johannes de Laet, who expressed admiration and envy for the project led by Hernández.88 Its primary researchers, Georg Marcgrave and Willem Piso, who were based in Mauritstaad (Recife), relied heavily on Indigenous (primarily Tupinamba) knowledge and labor.89 They also depended on familiarization and predation to generate knowledge about Brazilian animals. In the entry for the parakeet, “called by the Brasilians Tui,” they explained that “these become very tame, so that they will take meat out of one’s mouth and permit one to stroke and handle them.” In the entry for the cabure, they note that the bird “plays with men like an Ape, making mowes and antic mimical faces, and snapping with its Bill.”90

The “Historiae animalium” also found emulators in members of the Royal Society of London, including John Ray, Francis Willughby, and Hans Sloane.91 The works on fish, birds, and mammals that Ray and Willughby published in the 1670s have long been seen as pivotal in the history of zoology, an epistemological break far removed from the sixteenth-century humanist scholarship about animals.92 In the preface to The Ornithology (1678), written after Willughby’s death, Ray asserted such novelty.93 He explicitly and implicitly contrasted his and Willughby’s methods with those of earlier humanists like Gesner and Aldrovandi and, in doing so, articulated the “epistemic virtues” of the ideal naturalist, a term only recently coined.94 Ray wrote that he and Willughby “did not as some before us have done, only transcribe other mens’ descriptions, but we our selves did carefully describe each Bird from the view and inspection of it lying before us.” He insisted that authority came, above all, not from bookish “Authors” (he claimed that he and Ray “rectified many mistakes in the Writings of Gesner and Aldrovandus”) but from people whose occupations gave them direct experience working with animals, such as falconers, “fowlers,” and “a fisherman of Strasbourg.” He considered that textual description was necessary but insufficient and that images drawn by skilled artists from life were key: “elegant and accurate Figures do much illustrate and facilitate the understanding of Descriptions,” if these “Pictures” are “drawn in colours by the life” and “drawn by good Artists.” Ray thought the naturalist ought to reject enchanted “fables, presages or ought else pertaining to Divinity, Ethics, Grammar, or any sort of Humane Learning.” Instead, he was to “present” the reader “only with what properly relates to their Natural History.” Although Ray implied that he and his collaborators were the inventors of these new methods, the “Historiae animalium” had laid the groundwork for them.95

In fact, the “epistemic virtues” named by Ray were first advanced in the “Historiae animalium.” This earlier and much emulated work coproduced by Hernández and Indigenous experts modeled the epistemic virtues of observation, vocational mastery, life-drawn images, disenchantment, and disavowal. Some of these virtues are inseparable from the history of Indigenous ways of knowing: Hernández depended on Nahua scholars who were able to translate “Earthly Things” and interview the atlaca (“water folk”) and numerous other unnamed Indigenous hunters, fishers, and tamers to understand how animals sounded, looked, and behaved. Hernández relied on the Nahua artists Vazquez, Anton, and Elías to describe, draw, and paint animals from “life.” And Hernández not only depended on this multitude of Indigenous experts; he also learned about new modes of observation and description that had their basis in Indigenous ideals of teixiptla and other elements of predation and familiarization.

Other emergent epistemic virtues in the “Historiae animalium” emerged from Hernández’s desire to maintain colonial hierarchies and guard against idolatrous contamination. Hernández’s rejection of “fables” and “presages”—what he qualified as “childish beliefs and lies that originate in the credulity and shallowness of these people”—is inseparable from broader colonial anxieties about cultural contamination. In other words, the “disenchantment” that is often thought to characterize modern science cannot be understood without colonists’ desire to appropriate Indigenous knowledge while maintaining a sense of cultural superiority. This epistemic virtue, in turn, is related to acts of disavowal—efforts to repackage Indigenous knowledge as European: in the case of Willughby and Ray, to claim Ibero-American innovations as English. Just as Hernández was discomfited by the heterodox beliefs of his Indigenous interlocutors, Protestants Willughby and Ray were uneasy about Catholicism, the “bad Religion” of their Spanish sources.96

One of the most significant legacies of the “Historiae animalium” was its contribution to constructing the naturalist and the specimen. This natural history was the progenitor of the later modern scientific framework that simultaneously insists on humans’ fundamental commonalities with other animals and humans’ entitlement to dominate them. In other words, it laid the groundwork for epistemologies that emphasized the common ancestry shared by humans and other animals and distinguished humans from other animals by segregating the knowing subject (a European man) from the passive object (an animal).

LATER GENERATIONS OF European and settler-colonial naturalists were not the only ones affected by their contact with the “Historiae animalium.” So, too, were the Tlatelolco scholars who returned to the “Historia universal,” the project directed by Sahagún in the wake of the scholars’ experiences working under Hernández. Resumption of work on what became the Florentine Codex was made possible by a change in the Franciscan order’s leadership in New Spain. Sahagún reacquired the manuscripts, and from fall 1575 through 1577, the Nahua scholars returned to the workshop in the Colegio de Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco.97 The team of “grammarians” and scribes was now joined by a number of illustrators.98 They also faced a new set of challenges. In the late summer of 1576, the severe outbreak of epidemic disease raging through New Spain reached Mexico City. In November 1576, Sahagún wrote that “many people have died, die and every day more are dying . . . the number of dead has always gone increasing: from ten [to] twenty, from thirty to forty, from fifty to sixty and to eighty die every day.”99 Members of the Tlatelolco team were among the epidemic’s victims.

Book 11 of the Florentine Codex differed in several respects from the draft composed by the Tlatelolco scholars more than a decade before. As discussed previously, the text included forty-three new animal entries. It reorganized some sections, and, as in the rest of the books of “Historia universal,” the right column featured the Nahuatl text, while Spanish translations and copious colorful images shared space in the left column (see figs. 8.1, 11.4). For the images, the illustrators drew upon both Indigenous and European pictorial traditions.100 They depicted some of the animals in the specimen style, while they placed others in narrative sequences, often in vertically arranged panels. The Spanish “translation,” as Kevin Terraciano has pointed out, should be considered as an independent text as it often diverged from Nahuatl in significant ways.101 It was previously assumed that Sahagún was responsible for the translation, but Victoria Ríos Castaño has argued that some or all of it was likely the work of the Nahua scholars.102

In some respects, book 11 displays closer alignment with European antecedents than the earlier draft. This is evident in the book’s new organization. The chapters were reordered in a schema that was closer to that of Pliny than that of the encyclopedias, with the animal chapters preceding those on plants.103 Within the animal chapters, the organization no longer accorded to the cosmogramic logic affording primacy to animals of the arboreal canopy. Instead, by featuring land-based quadrupeds before birds, it followed the European tradition found in Pliny and the encyclopedias alike, perhaps reflecting Hernández’s influence on the project. The Spanish title, “Book 11 is a Forest, Garden and Orchard of the Mexican Language,” echoed that of the Hortus Sanitatis (“Garden of Health”) and emphasized the text’s linguistic uses, perhaps to assuage concerns about potentially heretical content.104

Although book 11 was “more” European than the earlier drafts of “Earthly Things” in some ways, the Tlatelolco scholars also managed to assert their voices and perspectives more strongly in this work. Or, in the words of Iris Montero Sobrevilla, the Nahua collaborators turned the natural history into a “powerful” form of “indigenous memory-keeping.”105 This is the case despite—or perhaps because—the authors appear to have composed these entries during or after working on Hernández’s natural history research project. A close analysis of the new entries reveals that the Nahua contributors expressed their views of nonhuman animals in ways that were strikingly divergent from Hernández and, it would seem, Sahagún. Small but notable differences suggest that the authors were, in a sense, talking back to Hernández by offering divergent opinions about the taste of certain animals’ flesh. In some instances where Hernández declared the flavor of particular birds unappetizing, the authors of book 11 praised it. Both sources agreed, for example, that the xalcuani was a migratory bird who sometimes inhabited marshlands (Hernández identified it as a type of duck) and whose Nahuatl name derives from “it always eats sand.” Hernández concluded that its “fishy aftertaste” rendered it “not pleasing as a food,” whereas the Tlatelolco seminarians insisted that the birds were “edible, savory.”106 Hernández considered the flesh of the tzonyayauhqui greasy and fatty. The seminarians, while conceding that “it is fat, like tocino” (inserting the Spanish word for bacon in the middle of the Nahuatl text, asserted that the bird’s flesh was “good-tasting.”)107 Somewhat more provocative is the scholars’ presentation of the tapir’s flavor profile. The “Historiae animalium” entry simply states that it “contains both the flavor of animals and birds.” The Tlatelolco authors described it more evocatively: “Not of only one flavor is its flesh; all the various meats are in it: human flesh, wild beast flesh—deer, bird, dog.”108 We can read in these small but telling divergences an expression of the Nahua scholars’ disagreement with disrespectful and exploitative colonizers like their demanding and unappreciative employer Hernández. We can also see the scholars’ insistence that the game found distasteful by the Spaniard was, in fact, quite delicious. The scholars’ observation that the flesh of nonhuman animals could be comparable with that of human animals might express a desire to commemorate practices that had become forbidden. Perhaps this provocative act was prompted by the apocalyptic atmosphere produced by the devastating epidemic outbreak.

The Nahua authors’ desire to refute Hernández’s perspective on their culture and traditions went beyond disagreements about flavor and mouthfeel of game. A number of the entries offer more details about omens, origin stories, and traditional ritual practice than the entries written in the 1560s. Perhaps this shift indicates Sahagún’s looser grip during this final phase of production, when he was racing the clock against the killing spree of epidemic disease and the project patrons’ increasing unease. A new entry that offers a particularly potent example of this shift in tone and approach is that for the “quauhtlotli,” a bird of prey.109 It was also, according to the entry, known as a “tlhoquautli.” The authors inserted the Spanish word falcon (“alcon”) in the Nahuatl description. The “Historiae animalium” includes an entry for “quauhtlotli” which Hernández (or one of the Nahua scholars) translated as “Arborum Accipitrum” (forest falcon) and identified as a “sacrum falconem,” that is “almost the same as that of our lands,” although “more beautiful and fierce than those of the Old World.”110 Although contemporary scholars disagree about the species or even genus of this bird,111 the aplomado falcon (falco femoralis) seems a likely candidate.112

Although Hernández provided no descriptive details of this bird’s beauty or fierceness, his Nahua collaborators did. The entry for the cuauhtlohtli in the Florentine Codex is much more precise about the falcon’s appearance, behaviors, and the methods employed to take it captive. The authors noted that the “bird has dark gray feathers, and a yellow bill and legs,” while the “hen is somewhat large, and the cock somewhat small,” the latter a characteristic of the aplomado. Regarding the raptor’s manner of hunting, they observed that “When it goes flying over birds . . . it does not strike them with its wings; it only tries to seize them with its talons” until the prey “can no longer fly,” a practice common to eagles who generally use talons to hunt. If the cuauhtlohtli “succeeds in catching one, it at once clutches [the prey] by the breast then it pierces its throat; it drinks its blood, consumes it all. It does not spill a drop of the blood.” (Like falcons, their method of killing is to use their beak.) When ready to consume its catch, the bird “plucks out the bird’s feathers.” In this manner, the bird eats three times daily, “first before the sun has risen; second, at midday third when the sun has set.” Regarding their parenting style, the birds, who bear “only two young,” rear them “in inaccessible places,” nesting in the “openings of the crags.” Regarding their capture, the hunters find their nesting places and there “place a duck” and “in its breast cage,” they “conceal a snare, though some only wrap the snare around it.”113

Embedded near the end of the entry is a different sort of detail. The authors wrote, “And this falcon gives life to Uitzilopochtli because, they said, these falcons, when they eat three times day, as it were give drink to the sun (tonatiuh); because when they drink blood, they consume it all.” Although brief, this text is dense with imagery and associations. With the reference to the deity Huitzilopochtli and the sun, it evokes the migration story of the Mexica and the sun’s role as an apex predator, who like the eagles with whom it is identified, feeds on blood (see fig. 7.3). It also suggests the ritual practice of feeding the sun with quail multiple times throughout the day. Although the authors distance themselves slightly from the content by including what Paul Haemig has characterized as the warning phrase “they said,” they refrain from condemning ritual practices, unlike several entries in the 1565 draft.114

In the left column, an abbreviated Spanish “translation” precedes the images. This translation describes the bird’s manner of piercing the throat and plucking the feathers of prey and notes that “the males and females go separately and the female is larger and the better hunter,” omitting information about the sun and Huitzilopochtli entirely. The Spanish-language silence is not surprising.115 Perhaps Sahagún made the translation, or perhaps the Nahua scholars produced the abbreviated and anodyne Spanish to distract from the inflammatory and heterodox content of the Nahuatl text.

If the Spanish “translation” removes the potentially incendiary information in the Nahuatl text, the pictorial version intensifies and exceeds these provocations. No pictorial equivalent of a “warning phrase” appears. Instead, the images even more potently connect the behavior of these falcons to practices and beliefs underlying predation and familiarization. The images appearing on the second page of the entry are arranged in a vertical column of three panels (fig. 11.4). The intentionality of the illustrator is demonstrated by the fact that the image includes a whited-out portion. In the upper panel, a raptor seizes a smaller bird, the latter surrounded by falling feathers of green and red hues. In the middle panel a mother bird nests with her two young ones in a remote crag. In the bottom panel, a figure with a man’s body and a hummingbird head offers a human heart to the cuauhtlohtli in the sky above him. Like the tonalamatl cosmogramic tradition that likely inspired them, these images can be read in multiple ways. The upper and middle panels correspond closely to the naturalistic description in the text: The top panel depicts cuauhtlohtli’s mode of catching prey with talons and plucking them of their feathers, and the middle one shows the female tending to her young.

Other interpretations are possible. The three panels also allude to the foundation story of Tenochtitlan. The middle panel recalls Mexica origins in the cave of Chicomoztoc amid the rocky, austere landscape associated with these northern biomes. The bottom panel suggests the casting of Copil’s heart that will give rise to the nopal cactus, and Huitzilopochtli’s promise to the Mexica’s ancestors that they will know where to settle when the eagle bird alights on the cactus.116 The upper panel depicts the moment when Mexica knew they had found the place to found Tenochtitlan: Although the nopal cactus is absent, the image, like other colonial-era Mexica cosmograms, shows a bird of the North and the West eviscerating colorfully plumed birds of the East and the South, some painted the blue-green of the quetzal, and others red, suggestive of macaws or roseate spoonbill.

The image also conveys the universality of familiarization: everything that provides food must also be fed. The identities of the figures in the bottom panel are, perhaps purposefully, ambiguous.117 The cuauhtlohtli can be read as a solar entity (tonatiuh)—as the text itself suggests as well as the pictorial imagery of the tonalamatl and other postclassic artifacts that depict the sun as an eagle. The hummingbird-man might represent a tlamacazqui, one of the “priests” who wore the garb of the deities they served, as seen in the Borgia cosmogram (figs. 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.4). If this is the case, this panel depicts a priest feeding a human heart to Huitzilopochtli, in his solar incarnation and as the deity who encouraged the Mexica to wage war against other communities, thereby ensuring the sun a constant supply of food. It resembles, in content if not style, the Codex Borgia image depicting the coyote-skeletal tlamacazqui feeding a blood offering to the sun and the earth (fig. I.2). Like those in the Borgia tonalamatl, the image in book 11 conveys the essence of familiarization: the sun, the most apex of predators, must be fed blood and hearts, sustenance that enables it to feed the crops on which people subsist.

Figure 11.4 Cuauhtlotli (raptor) in Florentine Codex, bk. 11, fol. 48r, ca. 1575–1577, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Med. Palat. 220, c. 199v. Reproduction used by permission of the Ministry for Heritage and Cultural Archives. All rights reserved.

FOR THE INDIGENOUS peoples of Mesoamerica, hunting, taming and spiritual practice were commingled. Precise understanding of animal behavior and exquisitely detailed apprehension of bodily appearance were highly valued by the inhabitants of Mesoamerica before and after the European invasions. These faculties linked hunting and taming practices to the ritual use of feathers, skins, and pelts. Europeans would learn from these practices of observation and description in ways that would transform their own natural history traditions. This fact should not blind us to their origins in Indigenous America. European scholars and researchers—most notably Hernández and the northern European naturalists conventionally associated with “modern” zoology who followed him—stripped away anything they considered “fabulous.” But the Tlatelolco scholars saw no reason to do so. Their story is as integral to modern natural history as those of Hernández and his successors.

One of the most significant legacies of the “Historiae animalium” was its construction of the modern naturalist. It modeled the tasks of the naturalist: identifying animal species, closely observing and describing appearances and behaviors, collecting specimens, and drawing from life. The labor and knowledge that made this zoological compendium possible was primarily Indigenous: the knowledge of hunters, tamers, atlaca and amanteca (featherworkers)—whose practices were conditioned by predation and familiarization—fills the pages. It was the Nahua Tlatelolco scholars and artists who creatively entangled the European genre of natural history and specimen drawing with the knowledge produced by those who worked directly with other species. The “Historiae animalium” was, of course, also the work of Francisco Hernández. His anxieties about Native idolatry and his commitment to colonial social hierarchies also left their mark on his opus. The Spanish protomédico ensured that entries were disenchanted: they were, mostly, purified of “superstitious” and “childish” beliefs, resulting in text that not only had less ritual content than the Florentine Codex but also lacked the fantastical creatures that had characterized classical and medieval European works. Hernández disavowed Indigenous contributions: despite his enormous—and occasionally acknowledged—dependence on this expertise, he equated the exemplary naturalist with himself, an elite European man. Perhaps by realizing the entangled Indigenous and colonial origins of the modern biological sciences, we can appreciate their roots in ontologies that have long recognized the multiplicity and capacities of the inhabitants with whom people share the earth.