Chapter 1

Composed Theatre: Mapping the Field

Matthias Rebstock

Symptoms of Composed Theatre

In what follows, the question ‘what is meant by the term “Composed Theatre”’ will be addressed by taking a historical approach, looking for its traces and forerunners. The assumption is that, since the sixties, a field of artistic practice has arisen that is situated between the more classical conceptions – and institutions – of music, theatre and dance, and that is highly characterised and unified by making use of compositional strategies and techniques and, in a broader sense, by the application of compositional thinking. As a first step, this field can be exemplified by some of the main figures working in it and developing it: composers like Heiner Goebbels, Georges Aperghis, Manos Tsangaris, Carola Bauckholt, Daniel Ott, Robert Ashley or Meredith Monk; theatre directors like Robert Wilson, Christoph Marthaler or Ruedi Häusermann; in dance, part of the work of Xavier le Roy, William Forsythe and Sasha Waltz, ensembles and theatre-collectives such as Theater der Klänge in Düsseldorf, Die Maulwerker and the LOSE COMBO both in Berlin, Cryptic in Glasgow or the Post-Operativ Productions in Sussex; most of them having some roots in the work of composers such as John Cage, Mauricio Kagel, Dieter Schnebel or in the Fluxus movement.

By introducing the term ‘Composed Theatre’, the aim is to focus on this – necessarily non-homogeneous – field because within it, artistic processes are currently moving forward in a way that gain momentum from mutual influence and exchange of practices and positions, and that this, so far, has not been taken into account by academic research, which usually still focusses only on aspects, questions or positions relevant to the particular discipline of the researcher.1 But as Composed Theatre is something that may be said to exist between art forms, so an interdisciplinary approach is required to describe and account for it. This being in between not only has consequences for academic purposes but also for the educational system. If it is true that contemporary theatre and performance in general – not just within Composed Theatre – challenges the separation of the art forms that had taken place in the second half of the eighteenth century, somehow recalling or bringing forward an integrated concept of theatre, then this should also lead to changes in an educational system in which interdisciplinary courses are still very rare. I will return to this problem towards the end of this chapter.

But let us first go back to what is meant by the term ‘Composed Theatre’. In the discussions during the two conferences on “Processes of Devising Composed Theatre” from which this book has emerged, it quickly became clear that the term ‘Komposition’ in German is very strongly linked to the field of music.2 ‘Komposition’ in German usually means musical composition. In English, however, it means something being put together in a much broader sense, which is not per se linked to music at all. So obviously the concept of Composed Theatre needs some clarification here, because if ‘composition’ or being ‘composed’ was to be taken in the broad sense – as the Latin origin ‘componere’ (= ‘place together’) suggests – Composed Theatre would cease to mean anything precise at all, as theatre in this sense is always composed. So a first important specification is that the term has to be taken in its musical sense. That means, if the field of interest is characterised by the use of compositional strategies and techniques, these strategies, techniques and ways of thinking are typical of musical composition and, moreover, are applied no longer just to musical material but to such extra-musical materials as movement, speech, actions, lighting or whatever you have in the realm of theatre.

A second characteristic or symptom3 of Composed Theatre consists in the aesthetic conviction of the independence and absence of hierarchy among the elements of theatre or, to put it another way, in the conviction that in principle no element should so dominate that the others would be reduced to illustrating, underpinning or reinforcing the first. Georges Aperghis makes this very clear when saying:

The visual elements should not be allowed to reinforce or emphasise the music, and the music should not be allowed to underline the narrative. Things must complement themselves; they must have different natures. This is an important rule for me: never say the same thing twice […]. Another thing has to emerge that is neither one nor the other; it is something new.

(Aperghis 2001)

Similar statements could be found from most of the artists within the field.4 Interestingly enough, there is a certain latent tension between this first conviction – which implies that each element is not only treated with equal rights but also accorded its own rules and strategies – and a second one, namely that the organisation and interaction of all such elements should follow musical or compositional principles. Thus, the relations between these independent and equal elements and the overall structure of the pieces are governed by compositional means.

Thirdly, Composed Theatre is not only – or even not necessarily – characterised by compositional strategies at the point of performance but also – or even only – during the artistic processes of creation. A performance may not show any typical sign of compositional strategies; yet, without applying such strategies, the composer, the director or the ensemble would not have come to the same result. This means that dealing with the field of Composed Theatre requires a consideration, not only of the performances but also of the working processes if we are to determine in what sense compositional thinking drives these processes. Typically – though not in all cases – within the working process there are phases of experimenting, generating new material, structuring of material, structuring of progressions and combinations and finally creating the formal overall structure, and all these phases may be governed by compositional principles.

What can be seen as a fourth characteristic of Composed Theatre is that the working processes will generally differ from those within traditional theatre. What usually happens, to put it simply, is the separation of the different stages of production: text – musical composition – staging – performance. And for each step it is pretty clear who has the last say. Composed Theatre, however, very often is devised theatre, or at least works against hierarchical normsand with a more collective approach, leaving more space for each individual to bring in their own competences and personality than there is in traditional theatre work. The performers will very often get involved in the developing process of the piece itself, and the segregation of the different steps of production is less strict, thus giving way to a more integral approach of mutual influence and exchange. As a result it is very often unhelpful to attempt to distinguish between a piece or a composition on the one hand and a way of reading, interpreting and staging it on the other. Consequently Composed Theatre, fifthly, can be understood as a genre that basically exists only in its perfomances: it is only in the moment of performance that the different elements come together, and everything before that moment points to it. This directly affects the role of notation and scores within Composed Theatre. Constituting the necessary way to facilitate the performance, they cannot in themselves represent the work or the piece. The composition process is prolonged through the process of staging until the very moment of the performance. That is why so many composers in the field also take responsibility for staging and directing their pieces themselves (e.g. Dieter Schnebel, Mauricio Kagel, Heiner Goebbels, Georges Aperghis and so on).5

Thus, ‘Composed Theatre’ refers to the creative process and the performance of pieces that are determined by compositional strategies and, in a broader sense, by compositional thinking. But ‘compositional thinking’ is an elusive term. The quest is for a definition that is sufficiently broad to accommodate the needs of different art forms, but sufficiently specific to give full value to the musically derived concept of composition as the productive theatrical force. We are looking for something beyond the metaphorical. The musical titles Kandinsky gave to his paintings are just metaphorical. But what of Vsevolod Meyerhold’s claim that theatre performances should be ‘put together like orchestral compositions’, or Dieter Schnebel’s reference to ‘visible music’? Is this more than a metaphorical way of speaking?

Things get more difficult as the concept of composition or compositional thinking, even if restricted to the field of music itself, is subject to historical changes. These changes take place in response to the other art forms and their techniques. For example, the musical techniques of phrasing, interpunction etc. are derived from an aesthetics that understands music as a kind of language, but this transfer from the realm of language to the realm of music is a matter, not only of terminology but also of thinking and understanding. And equally, when looking at the music of Ockeghem, Dufay or Josquin des Pres, one can easily see that the idea of building musical pieces on a system of complex proportions is heavily influenced by architecture – itself historically influenced by the idea of the ‘harmony of the spheres’ proposed by Pythagoras and his followers. So can there be anything specifically musical within ‘composition’, and what would that be when the realm of music in a strict sense is left and one enters the field of theatre? In the following these questions will be addressed from a historical perspective in order to cast some light on the developments through which the practices of today have been adopted. My assumption is that it is these common historical threads and aesthetic influences, more than a single clear-cut definition, that hold together the field of what we now call Composed Theatre with all its very different forms.

Richard Wagner and the Gesamtkunstwerk

It might be suprising to start with Richard Wagner, as opposition to Wagner’s music-theatre and his pathos and heroism seems to be a position most representatives of Composed Theatre have in common. However, in his aesthetic writings Wagner was the first and certainly the most radical to claim that in theatre all elements should come together with equal rights. And Carl Dahlhaus points out that the most important achievement of Wagner’s was yet something else: the ‘aesthetic revolution’ of Wagner was his claim

daß das Theaterereignis nicht bloßes Mittel zur Darstellung eines Kunstwerks, dessen Substanz der dichterisch-musikalische Text bildet, sondern selbst das eigentliche Kunstwerk sei, als dessen Funktion man Dichtung und Musik auffassen müsse.6

Wagner with his Gesamtkunstwerk was certainly not the first to pursue ‘synthetic visions’. Rather he is relying upon and developing the ideas of early Romantic writing, especially the idea of the unity of the arts and the overcoming of their separation.7 But whereas, for early Romanticism, theatre was an inferior art form, Wagner put it on the same level as literature and music, an elevation that has been sustained until today. And at the same time his ideas of intermedial relations were of enormous influence on further theatre development:

Der Musikdramatiker setzt Worte, Töne und Bildentwürfe auf der Ebene der Partitur in Beziehung. Der Regisseur, wie ihn Edward Gordon Craig fünfzig Jahre später exemplarisch entwarf, betreibt diese intermediale Kompositorik mit dem Arsenal der Bühne. Der Schritt von dem, was Wagner ‚Gesammtkunstwerk’ [sic!] nennt, zu Craigs Konstitutionsformel, die Theater als ‚Gesamtheit der Mittel’ begreift, ist winzig.

(Hiß 2005: 56)8

Musicalisation of theatre

As early as in 1969 Marianne Kesting wrote a remarkable paper, “Musikalisierung des Theaters: Theatralisierung der Musik” (Kesting 1969).9 She gives a historical outline of these two threads converging in the sixties in a fluid interplay of art forms such as Experimental Theatre, Happenings, Fluxus, Mixed Media, Instrumental Theatre, Experimental Music and so forth that can also be taken as a first peak of Composed Theatre. Reconstructing history along these two separate but converging threads is still a valid approach, one that is adopted in what follows here. Of course, historical developments in theatre and music did not take place separately from each other. They touched whenever the separation of the arts was radically questioned: in Futurism, Dadaism, including the MERZ-Bühne of Kurt Schwitters, at the Bauhaus or in the writings of Antonin Artaud etc. But none of the great composers has ever formed part of one of these avant-garde movements10 and mostly the different art forms were still so clearly distinguished that it makes sense to look first at theatre and then at music separately.

Theatre, which has always integrated other forms of art, became a model case for interdisciplinary art in the early twentieth century. This new kind of theatre no longer considered itself as ‘represented literature’; it liberated itself from the primacy of language.11 The theatrical reforms of the avant-garde are connected primarily by their fundamental critique of language. Language was toppled from its throne, where it had stood uncontested for centuries at the pinnacle of the hierarchy of theatrical elements. Edward Gordon Craig aimed for a reform, after which “the Art of the Theatre would have won back its rights, and its work would stand self-reliant as a creative art, and no longer as an interpretative craft” (Craig 1957: 178). Meyerhold sought to supplement spoken language by using biomechanics to transfer the laws of mechanics to the actor’s body. In Dada soirées, meaning in language was banished by all means of textual collage, simultaneous poems and sound poems that emphasised language’s qualities of sound and noise; the forms of abstract theatre practised in Futurism or by Oskar Schlemmer of the Bauhaus neglected to bestow any role upon language; and in Artaud’s work, language was integrated into theatrical elements that were to be structured according to musical principles.

The crisis of language is intimately associated with the crisis of narrative. If the semantic dimension of language retreats into the background, then there is no longer a linear plot or story told on stage that has the power to determine the form of the theatre. This theatre requires other structural principles and new concepts of form. The ways to approach this problem are divergent, but what they do have in common is the search for forms of non- narrative theatre. Theatre is no longer the staged interpretation of a literary text, but rather an independent, creative art form: “The art of theatre is neither a spectacle nor a play, neither staging nor dance. It is the totality of elements of which these individual areas are comprised” (Craig 1959: 138). These forms of theatre all tend towards totality, towards the Gesamtkunstwerk, although not in Wagner’s understanding of the term as, for Wagner, the text-based narrative was an essential feature of his musical drama. Here, totality refers to the entirety of the elements that comprise the theatre; it becomes a point of intersection, a site at which various elements come together in the presence of the audience: space, colour, light, movement, sound, language, etc. Meyerhold speaks of an “independent total theatre […]

10. Kandinsky, however, asked Schönberg to join the Bauhaus. But Schönberg rejected as he was afraid of antisemitism in the city of Weimar; see Kienscherf (1996: 186).

that should summon not just the spoken word, but also music, light, the ‘magic’ of the visual arts and the rhythmic movements on the stage” (Meyerhold 1930: 253). Meyerhold pushes the theatre in the direction of choreography and dance and deploys musical terminology in the description of what makes a production significant and revealing:

We saw that we would have to piece together this performance according to all of the rules of orchestral composition. Every actor, taken individually, isn’t singing yet; they need to be embedded in groups of instruments or roles; these groups again need to be interwoven in a highly complicated orchestration; the lines of the leitmotifs have to be raised up in this complicated structure, and actors, light, movement, even objects – similar to an orchestra – everything has to be conducted together.12

This idea of composing all elements according to a musical model also shapes the theatre experiments of Oskar Schlemmer at the Bauhaus and the visions of László Moholy-Nagy, whose ‘theatre of totality’ is “an organisation of precise form and movement, controllable down to the last detail, that should be the synthesis of dynamically contrasting phenomena (of space, form, movement, sound and light)” (Moholy-Nagy 1925: 155). For Moholy-Nagy, the human actor becomes completely superfluous, “because, however cultivated he may be, he can at most perform an organisation of movement that is at best related to the natural physical mechanism of his body” (Moholy-Nagy 1925: 154). Moholy-Nagy envisions a mechanisation of the theatre. The crucial idea here is that of a moving, sound-producing image. Narrative, text and actors do not play roles in this ‘theatrical apparatus’; instead, there are moving surfaces of colour, light and film projections, mobile objects, etc. In contrast to Meyerhold and Schlemmer, Moholy-Nagy does not view the “synthesis of dynamically contrasting phenomena” as synaesthesia, understood as the metaphysical correspondence of specific colours with specific sounds or other stimuli; instead, Moholy-Nagy emphasises the contrasts of the elements: “I can imagine a total stage performance as a great, dynamic, rhythmic compositional process that combines the greatest colliding masses (accumulation) of resources – tensions of quality and quantity – in an elementally compressed form” (Moholy-Nagy 1925: 158).

In contrast to the Bauhaus and its abstract experiments in theatre, Dadaism sought to destroy this precise arrangement and organisation of different elements: anti-art, anti- work, anti-artist. At the end of a senseless and brutish war, Dadaists wanted protest rather than reform; instead of order, they sought a provocative declaration of chaos in art. The Dadaists were enthusiastic about noise and Bruitism, not in the sense of the Futurists and their apotheosis of war, but rather as a means to shout down the bourgeois order that had led Europe into World War I and the battlefields of Verdun. Dadaist techniques therefore have less to do with composition than de-composition or the destruction of the status quo: “assemble, collage, transform, alienate, reduce, destroy, ridicule” (Goergen 1994: 6), techniques that John Heartfield described in 1919/20 as ‘dadaing’. The de-compositional techniques of Dada are distinguished by their potential application to every kind of material; for example, one could cut up newspaper texts, or even musical compositions or images, and rearrange them in collages. In this sense, Dadaism pursues a ‘negative total theatre’.

Dadaism developed two techniques that assumed major significance in the late 1950s, particularly through John Cage: simultaneity and the incorporation of the incidental. Hugo Ball reports, “Hülsenbeck, Tzara and Janco performed a ‘poème simultan’. It was a contrapuntal recitation in which three or more voices speak, sing, whistle or otherwise produce sounds at the same time” (Ball 1916: 104). By presenting different texts at the same time, each of their respective meanings is on the one hand distorted because the audience cannot follow the individual poems; on the other hand, the overlapping creates a new text in which the fragments of the individual texts flow into one another and create unforeseeable relationships with one another. The effect on the audience cannot be predetermined; it is incidental and completely different for every member of the audience, depending on where his or her attention is directed and which associations these ‘live collages’ trigger for them.

In addition to Dadaist productions, Antonin Artaud’s theatrical utopia exercised a major influence on various exponents of New Music and Composed Theatre.13 Boulez was the first to make the connection between Artaud and developments in serial music, which at that time got into crisis. In 1958, Boulez wrote, “I don’t feel compelled to puzzle out Artaud’s language, but I have stumbled onto the fundamental problems of contemporary music in his writings” (Boulez 1972: 123). Artaud demanded a theatre that was liberated from the ‘chains of literature’, and that was to be created on and for the stage. And he also emphasised the totality of “all the means of expression utilizable on the stage, such as music dance, plastic art, pantomime, mimicry, gesticulation, intonation, architecture, lighting, and scenery” (Artaud 1958: 39). For Artaud, however, the term ‘totality’ is reserved for something else, for the totality of the human being and of life: “Renouncing psychological man, with his well- dissected character and feelings, and social man, submissive to laws and misshappen by religions and percepts, the Theatre of Cruelty will address itself only to total man” (Artaud 1958: 122). This totality aims for an ecstasy, for the ‘cruelty’ of human existence as a glance behind the mask of civilisation:

Theatre will never find itself again […] except by furnishing the spectator with the truthful precipitates of dreams, in which his taste for crime, his erotic obsessions, his savagery, his chimeras, his utopian sense of life and matter, even his cannibalism, pour out, on a level not counterfeit and illusory, but interior.

(Artaud 1958: 92)

Artaud wants to reconstruct the ancient connection between art and life in (religious) ritual through his theatre. To do this, however, the separation between the stage and the audience must be overcome: “We abolish the stage and the auditorium and replace them by a single site, without partition or barrier of any kind, which will become the theatre of action” (Artaud 1958: 96). It is precisely this connection between art and life that both the Happenings and Fluxus movements strove for with their respective theatres of action; indeed, their adherents viewed themselves as Artaud’s successors. Yet their neo-Dadaist spirit stands in opposition to the requirements of exactitude and precision in Artaud’s theatrical compositions, referenced above by Boulez:

Once aware of this language in space, language of sounds, cries, lights, onomatopoeia, the theatre must organize it into veritable hieroglyphs, with the help of characters and objects, and make use of their symbolism and interconnections in relation to all organs and on all levels. […] Meanwhile new means of recording this language must be found, whether these means belong to musical transcription or to some kind of code.

(Artaud 1958: 90, 94)

For the generation of young composers and artists in Germany and Austria after World War II, the contact to these avant-garde movements from the pre-war years had been cut off by National Socialism and therefore had to be rediscovered.14 At the same time a new type of theatre arose, primarily in France, that attached itself to several points of the theatre reforms of the early twentieth century, although it reacted in a unique way to the destruction and senselessness of war: the theatre of Beckett, Ionesco, Genet and many others, which Martin Esslin grouped together under the generic term ‘Theatre of the Absurd’ (Esslin 1996). Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano, the subtitle of which describes it as an ‘anti-play’, premiered in Paris in 1950; The Chairs followed in 1951. In 1952, Beckett published Waiting for Godot, which also premiered in Paris in 1953. And then there was Endgame, which, under curious circumstances for a French play, premiered in London in 1957.

Ionesco and Beckett both integrate the coarseness and grotesqueness of popular theatre and the gags and situational comedy of the vaudeville show. Vladimir and Estragon clearly refer to the tradition of the comic duo, even to the tragicomedy of silent films. Language plays a crucial role in the Theatre of the Absurd, but it is a language that revolves in emptiness, that can no longer move anything in reality, that does not set any narratives in motion and that is completely unsuitable as an instrument of perception. The language of this theatre engages in clichés and stereotypes; thus, for example, the text of The Bald Soprano is based on a collage of sentences from an English conversation book. It gets entangled in itself, disintegrates or falls completely into nonsense, as in Lucky’s famous monologue in Waiting for Godot, which is a parody of an academic lecture. And in The Chairs, the longed-for speaker finally arrives, only to reveal that he is mute.

The Theatre of the Absurd eschews psychological motivations for its characters’ stories, which follow patterns or archetypes, or remain – superficially – nonsensical. The individual stories do not come together into a coherent or evolving narrative; instead, these works focus on unfolding a basic metaphor over time, corresponding to the situational and pictorial character. This lends the works the form of a “complex poetic image, a complicated pattern of complementary images and themes that are interwoven in a manner similar to the themes in a musical composition” (Esslin 1996: 313). For example, the repetition of the exact same lines of text in Waiting for Godot, the structural meaning of pauses and the principle of variations upon motifs are all striking features. The structural principles of music permit the translation of basic, static, content-based situations into a regimented temporal framework.

The fundamental criticism of text and language as primary elements in the theatre has been levelled since the end of the nineteenth century. This critique led to a crisis of the psychological character and linear uninterrupted dramaturgy and has given rise to forms of theatre that were forced to secure the coherence of their works on the basis of other non-textual, non-dramatic approaches, integrating principles of structure and form that contributed to compositional approaches and ways of thinking.

Theatricalisation of music

Composing the non-musical: Die glückliche Hand by Arnold Schönberg

If we look at the complementary movement and look for music-theatre forms that start off by making the music itself theatrical or that which apply compositional means to theatrical elements, we inevitably find ourselves returning to the visions of Arnold Schönberg, and in particular the famous music of lights in his Die glückliche Hand op. 18 from 1913. In a text that he wrote for the 1928 performance of this ‘drama with music’, he found a very precise and telling way to describe his vision of a new kind of music theatre:

Figure 1: Arnold Schönberg: extract of Die glückliche Hand, bars 127–131. Copyright by Universal Edition.

Mir war lange schon eine Form vorgeschwebt, von welcher ich glaubte, sie sei eigentlich die einzige, in der ein Musiker sich auf dem Theater ausdrücken könne. Ich nannte sie – in der Umgangssprache mit mir: mit den Mitteln der Bühne musizieren.15

Schönberg’s libretto describes, in very symbolic language, a dream. A man, of whom it is said that he incorporates the ‘supernatural’, encounters a woman who gives him something to drink. He falls deeply in love with the woman as she had given life back to him. He touches her hand, but she goes away with another man. In the third picture the man comes to a kind of goldsmith’s studio where he makes a golden diadem with only one stroke on the anvil. The workers around him get furious, but before they can attack him there is “a crescendo of the wind” accompanied by a “crescendo of the stage lights” as it says in the score. Finally in the fourth picture the man finds himself back in the situation he was in at the start, and everything in between turns out to have been a dream he is going through over and over again.

The “crescendo of the stage lights” is described very precisely in the score: “Es beginnt mit einem schwach rötlichen Licht, […] das über Braun in ein schmutziges Grün übergeht. Daraus entwickelt sich ein dunkles Blaugrau, dem Violett folgt.”16 But it is also directly synchronised with the music, the crescendo of the wind and the acting of the man. For this Schönberg even develops a special kind of notation.

This passage is the most elaborate realisation of what Schönberg means with his idea of “composing using the means of the stage”. However, this idea is decisive for the whole piece and for all theatrical elements. In a letter of 14 April 1930 Schönberg writes to Ernst Legal of the Berlin Kroll-Oper about the staging of Die glückliche Hand:

Der Aufbau der Bühne und das Bild wird aus tausend Gründen haarscharf nach meinen Anweisungen erfolgen müssen, weil sonst nichts stimmen wird. […] Ich habe auch die Stellungen der Schauspieler und die We ge, die sie zurückzulegen haben, genau fixiert. Ich bin überzeugt, daß man das genau einhalten muß, wenn alles ausgehen soll.17

And in his text on the occasion of the Breslau-performance he points out:

Es würde gewiß zu weit führen, wenn ich alle Beispiele nennen wollte, die einen Begriff von diesem Musizieren mit den Mitteln der Bühne geben. Ich glaube aber sagen zu können, dass es jedes Wort, jede Geste, jeder Lichtstrahl, jedes Kostüm und jedes Bild tut: keines will etwas anderes symbolisieren als das, was Töne sonst zu symbolisieren pflegen. Alles will nicht weniger bedeuten, als klingende Töne bedeuten.18

Schönberg is clearly convinced that the effect the piece will have on the audience does not depend solely on the quality of the music but that all the elements in a performance of the piece contribute equally to the effect, and therefore he, as the composer, also organises these visual elements and fixes them in the score.

Schönberg who, as is well known, was also a remarkable painter, was strongly influenced by the synaesthetic ideas of the time.19 And what we see in Die glückliche Hand is that he composes more or less equivalent processes in the music, the wind, the lights and the movement to reinforce the effect of the whole. So even though one can say that here, maybe for the first time, visual elements such as lights are (musically) composed in a rather strict sense, the theatrical elements do not yet hold their own, are not yet of equal status. In other words: what we see is not yet the polyphony of the elements. If we look for early examples of this idea, so crucial in Composed Theatre, we would have to turn to the scores of the Mechanical Eccentric by Moholy-Nagy from 192520 or to the writings of film-maker Sergei Eisenstein. In his essay “Vertical Montage”, Eisenstein tries to develop a specific methodology for the montage of image and sound in film “by which correspondences between depiction and music are set up” (Eisenstein 1940: 271). But these correspondences no longer imply that sound and image should reinforce each other, but that they can carry different meanings and that, with this tension between the media or elements, a third meaning can be achieved.

Separation of elements: L’Histoire du Soldat by Stravinsky

In the field of music-theatre, Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat (1918) was a milestone with respect to a new way of organising the different theatrical elements. In this piece –a kind of anti-Wagnerian-opera – we find text (narrator), music (small ensemble) and acting (including dance and pantomime) placed on a stage divided into three parts: music and text at the sides, the theatrical part in the centre. So while in opera all comes together

culminating in the singer, who performs text, music and a theatrical role all at the same time, here each element is visually but also structurally independent from the others. And it all comes together only in the perception of the audience, thus making the audience an active part of the performance. Stravinsky makes this anti-operatic approach even more clear as he rejects singing altogether. The text is an adaptation of a Russian fairytale. Charles Ferdinand Ramuz, who wrote the text, retained its epic form, so that there is neither dramatic dialogue nor psychologically delineated characters. Instead they are like archetypes. As Ramuz pointed out: “Wir würden die alte Tradition der Gauklerbühnen, der Wanderbühnen, der Jahrmarkttheater wieder aufnehmen.”21 Stravinsky’s music follows this non-psychological approach in that he takes up forms of popular music (ragtime, tango, waltz) and works with them, alienates them etc. He consciously abandons Wagner’s through-composed form, returning to single numbers that can stand on their own and that are interpolated into the narration. So the character of the whole piece is one of distance and alienation, adopting popular theatre and music forms and bringing art very close to the world of people’s ordinary lives. L’Histoire du Soldat is, therefore, the first example of an epic music-theatre that became very successful in the twenties and thirties, especially in the collaboration between Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, but that also had great impact on the New Music Theatre of the sixties and seventies: small forms, non-psychological characters, no (operatic) singing, no dialogue, separation of the elements, empathy with popular or trivial culture (cabaret, music hall, variety etc.)22 and, last but not least, the emphasis on the visual and corporal aspect of making music. Stravinsky put the musicians on stage not only to demonstrate the separation of the elements of music-theatre, nor just for practical reasons, but in service to his conviction: “We nn man die Musik in vollem Umfang begreifen will, ist es notwendig, auch die Gesten und Bewegungen des menschlichen Körpers zu sehen, durch die sie hervorgebracht wird.”23

“Towards theatre”: John Cage24

Although historic and aesthetic contexts are completely different, there is a striking echo of Stravinsky in John Cage’s observation that “[r]elevant action is theatrical (music [the imaginary separation of hearing from the other senses] does not exist), inclusive and intentionally purposeless” (Cage 1955: 14). But Cage does not only mean that the visual

aspect of making music is an essential part of music. He is set on radically challenging the very concept of music and composition, and thus, by implication, he also challenges what has been said about Composed Theatre so far. In one way or another, ‘composition’ in music has always been understood as an intentional process of building meaningful musical structures and forms that guarantee the unity of a musical piece. And it is exactly this notion that John Cage and the composers of the New York School disposed of:

Cowell remarked at the New School before a concert of works by Christian Wolff, Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, and myself, that here were four composers who were getting rid of the glue. That is: where people had felt the necessity to stick sounds together to make a continuity, we four felt the opposite necessity to get rid of the glues so that sounds would be themselves.

(Cage 1959: 71)

This rejection of the old concept of composition is twofold: firstly, the aim is to avoid any kind of continuity between sounds or events, and, secondly, composing no longer has to do with the intentions of the composer but, quite to the contrary, the ‘new’ composer must develop a technique that will negate the interference of his intentions. Cage’s concept of composition only becomes productive for the discussion of Composed Theatre if we view it together with the equally radical change in the concept of music. Already in 1937 Cage had denied that there was any difference between noise and music, thus embracing within the concept of music any kind of sound: “Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating. The sound of a truck at fifty miles per hour. Static between the stations. Rain. We want to capture and control these sounds, to use them not as sound effects but as musical instruments” (Cage 1937: 3). With this Credo Cage puts himself in line with Edgard Varèse and also with futurism and its vision of a music of noises as described by Luigi Russolo in The Art of Noises (1916). But in the fifties John Cage went even further, opening music to any kind of action, with or without sound: “Where do we go from here? Towards theatre. That art more than music resembles nature. We have eyes as well as ears, and it is our business while we are alive to use them” (Cage 1957: 12).

For Cage, there are two approaches that lead to the theatre – one via the material and the other via the listener. By opening music to the sounds of everyday life – that is to the sounds of the environment (see 49330) and to the other arts – actions of any type can now be used as musical material. It is still music, though, because the only dimension that, elusively perhaps, remains fixed for Cage is that of time, the temporal shifts between (sound) event and silence. The second approach, via the listener, is based on Cage’s fundamental conviction that human experience is total: it is not divided between the different channels of sensory perception, neither in everyday life nor in art. Music is not just what is heard but also what is seen; it is the comprehensive experience of an action. And therefore “relevant action is theatrical”.

In 1952, Cage and David Tudor created a performance that pursued Cage’s idea of indeterminacy to its logical extreme, an action that radically questioned the idea of a musical work. The untitled event took place during a summer course at Black Mountain College, an interdisciplinary art school founded by Joseph Albers along the lines of the Bauhaus in Dessau. The untitled event was also interdisciplinary: participants included the composers John Cage and Jay Watt, the dancer Merce Cunningham, the musician David Tudor, the visual artist Robert Rauschenberg, and the writers Charles Olsen and Mary Caroline Richards. Cage’s composition consisted of nothing more than directions for periods of time (‘time brackets’) that prescribe to the actors when they act (or can act) and when they cannot. The actions themselves were determined by the actors without further discussions. During the action, Rauschenberg’s White Paintings – which Cage also animated for his famous silent piece 49330 – hung from the ceiling; Cage stood on a ladder reading a text from Meister Eckhardt and later performed a piece for radio. Tudor played a piece for prepared piano, Olsen and Richards read poems, while Cunningham danced through the room chased by an angry dog. Rauschenberg projected abstract slides and a film. Coffee was served during the performance. The audience was apparently thrilled, and Cage was pleased because the performance met his desire for the absence of intentionality. It was “purposeless in that we didn’t know what was going to happen” (Cage 1955: 15).

Here we see that, for Cage, the idea of non-intenionality is intrinsically linked with another idea that has become extremely important since: the idea of experiment or of the experimental. Cage at first, as he explains in his essay “Experimental Music” (Cage 1957), refused to call his music experimental. But later he accepted it. “What has happened is that I have become a listener and the music has become something to hear” (Cage 1957: 7). For Cage, music becomes something to hear only if the composer is in the same position as any other listeners insofar as, like them, he does not know in advance what exactly is going to happen, what there will be to be heard. And ‘composing’ means exactly that: the creation of such listening situations. This requires techniques to bypass the preferences and intentions of the composer and to avoid purposeful structures.

Where, on the other hand, attention moves towards the observation and audition of many things at once, including those that are environmental – becomes, that is, inclusive rather than exclusive – no question of making, in the sense of forming understandable structures, can arise (one is a tourist), and here the word ‘experimental’ is apt, providing it is understood not as descriptive of an act to be later judged in terms of success and failure, but simply as of an act the outcome of which is unknown.

(Cage 1955: 13)

Cage’s idea of the experimental is still vivid in the field of Composed Theatre – as in one way or another it continues to inspire the majority of contemporary art. But the focus seems to have changed somewhat. Most artists and ensembles try to develop strategies that deliver results that are unforseen and non-intentional, and therefore “experimental” in the sense Cage uses the term, be it by introducing chance operations or by researching the phenomenal qualities of certain artistic materials or questions etc.25 But all this usually happens as one part of the process of devising. For the performance, however, most artists come back to the more traditional concept of composition, that is the ‘forming of understandable structures’ such that the composer/the performers do know the outcome – at least within a certain range of chance – in advance.

But even if the aspect of non-intentionality has lost some of its impact, other features of Cage’s concept of composition and music are still extremely influential for the field of Composed Theatre. Most important is (1) the wide concept of music itself as outlined above. Music is not just any sound or noise but any event happening, any action being performed within a certain time span, be those actions artifical or environmental. Consequently, there is no difference between events to be heard or to be seen. Cage’s broad concept of music shifts towards theatre, negating not only the separation of the senses but that of the arts, too. And if composition is not about making structures there is also no question of selecting some elements rather than others. Everything can happen simultaneously. In this way Cage’s version of Composed Theatre is (2) the most radical realisation of the idea of non-hierarchy between, and independence of, the theatrical elements that is crucial to Composed Theatre.

As in the case of the untitled event, Cage’s pieces since 1952 are no longer fixed objects but (3) processes. “To approach them as objects is to utterly miss the point. They are occasions for experience, and this experience is not only received by the ears but by the eyes, too” (Cage 1958: 31). The untitled event exists only in the very moment of performance. It is unique and unrepeatable. What the ‘piece’ is, or is about, what it ‘means’ is completely left open to the experience of every single spectator – and all of them will experience something quite different. So Cage’s music – or theatre – (4) is directed to the perception and the individual experience of its spectators in the very moment of performance.

That Cage’s pieces are, in fact, processes, also implies that they are not completed by Cage but left open for the performers. They are indetermined. For Cage indeterminacy is one way to ensure that his own intentions do not enter his pieces and performances. But for the performers it requires an involvement in the compositional process of a particular version of a piece, making them co-composers. For example, in his Songbooks (1970) Cage gives rules and instructions to work out singles pieces, but how this is done will very much depend on each performer, his or her experience, taste, capacities etc. That means that Cage asks for – and makes himself dependent on –a certain kind of performer who is willing to get involved in the development of the pieces themselves rather than ‘just’ giving good interpretations of those pieces. With this (5) Cage changed the notion of authorship, opening the way to a less hierarchical and more collective way of working.

Cage’s aesthetics rapidly spread into different forms of art. The untitled event inspired a new interdisciplinary and performative form, the Happening. When Cage gave classes on experimental music at the New School for Social Research in New York in 1956, among his students were a few composers, including George Brecht and To shi Ichiyanagi, but mostly fine artists, photographers and film-makers, among others Allan Kaprow, Dick Higgins, Scott Hyde and Al Hansen.26 Cage’s aesthetics triggered Fluxus and Performance Art and had a great impact on contemporary dance, especially through his collaboration with Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg and Jaspar Jones. Today, Cage’s ideas are still especially efficacious in interdisciplinary contexts and therefore also in the field of Composed Theatre.

Total organisation of parameters: Composed Theatre and the spirit of serial music

If we examine early serial music, there seems to be very little that points in the direction of Composed Theatre. Serial music precluded any kind of extra-musical meaning, expression and subjectivity. Yet there are some features within the compositional basis of serial music that have become highly relevant for Composed Theatre. And it was the clash of this highly organised structural music with the aesthetics of John Cage and the early happenings that unleashed enormous productivity in the field of music-theatre in the sixties, making this period the true starting point of Composed Theatre. The central aesthetic qualities to which the serial composers devoted themselves were musical order and structure.

Order means: the merging of the individual into the whole, of difference into unity. The criteria for order are evocativeness and disambiguity. The goal of ordering is to approach the conceivable perfection of order in general and in its particulars. […] In total order, everything is equal in its individuality. The sense of order is founded in the disambiguity between the individual and the whole.

(Stockhausen 1952: 18)

The doctrine that all parameters are equal, reified via serial organisation, is initially related here solely to musical material in the narrow sense, namely tones, sounds and, with the early pieces of electronic music, noises as well.27 But it comes as a consequence of the emancipation of new materials that serial procedures and methods can be applied not only to tones, sounds and noises but also in principle to any material that can be arranged as scales and can be quantified in this way. One of the essential discoveries of serial music for composers was that the processes and strategies of composition are separate from the material used. Composition was understood as a set of specific methods of organisation that are no longer bound to specific material. And this step made composition with non-musical materials possible. Mauricio Kagel formulated this in his often-cited remark: “You can use sound materials. You can compose with actors, with cups, tables, busses, and oboes, and finally compose films” (Kagel in Prox 1982). So following the internal logic of serial music, European composers finally arrived at a point quite similar to one that Cage had already made in the early fifties, even if on the basis of completely different aesthetic beliefs, when he sustained that virtually everything could turn into musical material.

In his 1959 essay “Musik und Raum”, Stockhausen depicts the development of electronic music as an immediate consequence of the principle of equality of all musical parameters.

Since 1951, we have been confronted in composition with the striving for an equality of all of the characteristics of sounds: all of them should be involved in the same degree in the formative process so that you can always represent new creations in the same light. It turned out, though, that this equality of tonal qualities is extremely difficult to achieve.

(Stockhausen 1959: 69)28

Such exact proportioning, especially within the parameters of timbre and dynamics, “demands automatic electro-acoustic processes” (Stockhausen 1959: 69).

And there is another decisive point in the theatricalisation of music that is associated with electronic music. Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge was performed for the first time on 30 May 1956 in the large studio of the Cologne broadcasting centre. Stockhausen placed five groups of loudspeakers around the audience and allowed sounds and noises to be projected into the space and to move through the room. If spatial effects in music had previously tended to be a musical by-product or dramaturgical effect, now the sound space or sound movement became a component “essential for understanding the work” (Stockhausen 1959: 60).

In Gruppen für drei Orchester (1957), Stockhausen applied the principle of spatial loudspeaker distribution to three orchestras of identical instrumentation, and grouped them around the audience. It was only a small step to move from wandering sounds to wandering musicians, who then actually carried their sounds through the room.29 This is where music came into motion, and movement “is the fundamental element of Instrumental Theatre and is taken therefore into account during musical composition. Movement on the stage becomes an essential feature for differentiating from the static character of a normal musical performance” (Kagel 1960: 123).

The rapid development of instrumental techniques, in the context of the emancipation of timbre as an effective parameter, also led – indirectly though – to a theatricalisation of music, and turned concert-going into a visual experience. Schnebel, for example, wrote the following about the performance of Boulez’s Polyphonie X in Donaueschingen in 1951: “The conductor flailed out unusual tempo changes. The exorbitant difficulties of the instrumental parts created a game that somehow called to mind difficult gymnastic exercises” (Schnebel 1968: 8). There is also a theatrical element when a cellist, as in Kagel’s Match, suddenly threads his bow between the strings and the body of the cello and draws it across the underside of the strings. Here the action that an instrumentalist must perform to create a specific sound receives more attention than the sound that is produced. The action is liberated from its mere functionality; it is emancipated and constitutes its own independent theatrical element.

The use of unusual instruments has a similar effect, whether it be the sirens set in motion with a hand crank in Varèse’s Ionisation (1930/31), or the unusual percussion instruments, such as brake drums and anvils, that Cage uses in First Construction (in Metal) (1939). Such instruments entail a visual component; they belong to a specific context outside the art world, and they bear these associations with them as they are brought into the art world. In a similar way, the search for new sounds leads to the playing of traditional instruments in ‘inadequate’ ways; Cage for example often treats the piano like a percussion instrument.

One piece that combines all these elements is Cage’s Water Music (1952). The pianist sits in front of an enormous score. There is a pail of water and a radio next to him and a duck-call whistle around his neck. He starts a stopwatch and turns the radio on. For 21 seconds nothing else happens. The pianist listens, as does the audience. Depending on where the piece is performed, the radio plays static, music or overlapping broadcasts. Later the pianist plays a few musical gestures, stands up to throw playing cards into the body of the grand piano, sits down again, waits. He blows the whistle and submerges the whistle, still whistling, in the pail of water, pours water from one vessel into another, stands up to prepare a few sounds, plucks a single note, waits. Various actions are repeated. The piece is over when the stopwatch shows 6’40”.

Water Music can be considered an example of Composed Theatre. The objects used are heavily loaded with associations from the everyday world: the radio, pail, duck-call and playing cards. Without representing anything in particular, these objects incorporate their content into the piece. But these objects are used exclusively as musical instruments, on an equal basis with the piano. The actions required to operate these unusual instruments are just as unusual as the instruments themselves. The audible dimension of these actions appears to some degree as a by-product of visible actions – and not vice versa, as we are accustomed to, for example, from the movements that orchestral musicians make when they perform. When the pianist stands up and throws a few playing cards one after the other onto the grand piano’s strings, the audible effect of this musical action is less striking than the visual element of its enactment. Heinz-Klaus Metzger notes

Cage recognised at that time that one can scale the audiovisual compositions of actions, that a scale of purely visual actions can be constructed, beginning with a movement that is soundless, to gestures that make a little bit of noise, to the other extreme of a gesture that one can only hear and cannot see at all.

(Metzger 1960: 260)

Cage, however, was never concerned about such scaling or even an exact composition of these relationships. Metzger is clearly arguing here from the context of serial music, for which the possibility of scaling is the prerequisite for being able to work with something as musical material. Even if Metzger’s remark does not apply to Cage, the option of being able to compose actions serially, and especially the opportunity to contrast the audible and visible sides of these actions, played a crucial role in the development of New Music Theatre in Europe. Musical action, which was originally conceived as an organic whole in the making of music, turns out to be just as divisible into discrete parts as the individual musical sound.

Composition with stage sets: Die Himmelsmechanik by Mauricio Kagel

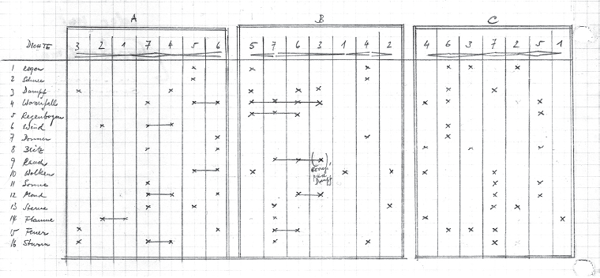

Mauricio Kagel’s Die Himmelsmechanik (1965) provides a particularly clear exemplification of how composition shaped by the experiences of serial music goes beyond its influences and leads to its own form of Composed Theatre. The piece is identified by a subheading in the score as a Composition with stage sets. In an Italian-style theatre the parts of a stage set move about: “At first, grey-pink clouds drift by, then a blue vapour appears in which the sunrise totters upward. As if by accident, the moon appears for a brief moment. He comes back though, marries the sun, such that only the full moon remains” (Schnebel 1970: 173). And all the movements of these set pieces are precisely notated in the score, where they follow a compositional and not a narrative logic. If we study Kagel’s sketches for Himmelsmechanik, it becomes clear that Kagel actually organised the procession of stage images in a very strict serial manner at the level of material organisation:

Figure 2: Sketch by Mauricio Kagel for the disposition of elements for Himmelsmechanik. Copyright by Paul-Sacher- Stiftung, Basel.

In the first step, Kagel de-composes the weather into 16 discrete elements, assigning a graphic symbol to each element. Twelve elements are represented with stage images only, that is, only in a visual way; rain and fire are represented acoustically and visually, and thunder and wind only acoustically. Kagel applies a quasi-symmetrical ‘series’ to the list of elements, read out from the middle: 3 2 1 7 4 5 6. Each one of these numbers determines how many elements appear simultaneously and at what intensity they will appear. Which elements would appear Kagel initially decided at random.30 Ultimately, this sketch remained a preliminary study. That is to say that Kagel did not follow this material organisation during the composition process. What is crucial, however, is the compositional thinking shown here in the creation of theatrical processes, thinking that is deeply influenced by the experience of serial composition. If the structural procedure at the material level is completely separated from the results at the level of perception, it follows that serial procedures can be applied to other non-acoustic materials; whether to temporal distances or statistical occurrences that are serially organised, or to the procession of weather conditions, makes no difference, as this level of organisation exists below the borders of perception. The only prerequisite, as stated above, is that the affected processes can be scaled in discrete units that can be represented by means of number series. These elements of serial music go far beyond this music to exercise a critical influence on Composed Theatre, in which compositional processes are applied to non-musical materials and media without a second thought. Here, in a very literal sense, the various elements of theatre are composed.

Composition of body language and sign language: The Composed Theatre of Dieter Schnebel

At the end of this chapter, I want to give two further examples that illustrate the application of compositional procedures to theatrical material: Körper-Sprache (1979/80) and Der Springer from the Zeichensprache cycle (1989), both by Dieter Schnebel. Körper-Sprache. Organkomposition für 3–9 Ausführende is the first composition by Dieter Schnebel in which he completely renounces the acoustic dimension. Körper-Sprache, like Schnebel’s more famous Maulwerke, is less a composition than it is a set of directions or handouts to the performers for the creation of a composition. As in Maulwerke, Schnebel composes a process rather than a result, one that can be written out into a work-like complex and performed, yet does not necessarily need to be so. Such a performance – and this is interesting in the context of Composed Theatre – does not necessarily lead us to believe that it has anything to do with music. An uninformed spectator, unfamiliar with Cage’s broad definition of music, would probably say that it was a form of abstract dance or theatre. But the way in which Schnebel organises the process, how he structures the material panels that comprise the composition, reveals that the piece is conceived through and through as a musical composition. And Schnebel’s own debt to his experience of serial composition can also be clearly seen.

Figure 3: Section from the introduction to Dieter Schnebel: Körper-Sprache (1979/80). Copyright Schott Music.

Schnebel starts off by subdividing the continuous field of possible human movements into discrete units in order to generate a matrix of combinatory possibilities to which any serial technique could in principle be applied.

In his introduction to the score, Schnebel writes:

By means of such quasi-mathematical division of physical movements, we can create mathematical combinations: 1+2, 1+3, 1+4, 2+3, 3+4, 1+2+3, 1+3+4, 2+3+4, 1+3a, 1b+2a, 3b+4g etc. […] This structure, with its seemingly pure formality and cool- headed analytical nature, facilitates on one hand acquisition and rehearsal as well as concentration; on the other hand, the structure corresponds to the limbs themselves and denotes empathy with the body’s structure, its connections – and its life.

(Schnebel 1980)

Almost exactly ten years after Körper-Sprache, Schnebel completed the Zeichensprache cycle, which premiered on 3 May 1989. Zeichensprache can be understood as a composed version of Körper-Sprache: the four regions of the body – head, arms, torso and legs – correspond to individual pieces. In contrast to Körper-Sprache, however, Zeichensprache no longer guides the performers to their own fully composed versions of the piece. One could say that Zeichensprache is a work instead of a process, meaning that Schnebel composes concrete actions and movements for a defined, straightforwardly performable piece. And, also in contrast to Körper-Sprache, Zeichensprache adds the acoustic dimension in the form of utterances, and Schnebel composes the relationship of these two levels with high precision. I will exemplify this with his piece Der Springer.

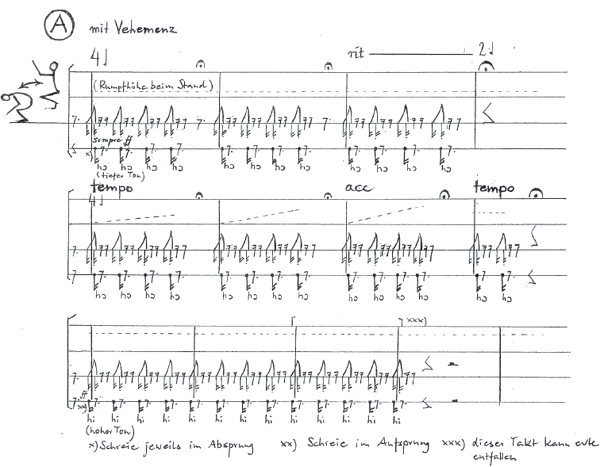

Figure 4: First page of Dieter Schnebel: Der Springer (1989). Copyright by Schott Music.

The piece begins with the exposition of the basic material: regular jumps from a half- upright position, with a sound uttered each time at the moment when the performer lands on the ground. From the audience’s perspective, this material is viewed as a unit, as a gesture of strength and resoluteness, perhaps also as a sign of stubbornness.

Schnebel de-composes this homogeneous basic material into three levels that he then writes as three independent layers into the score: the height of the torso, the jumping movements, and the sounds. It is interesting to see how, from this original gestural-musical unit, these three levels are emancipated as independent elements so that one can perceive the alternation between homophonic and polyphonic structures, and finally how a highly expressive piece of Composed Theatre arises from this analytical, technically composed grasp of movement, one that proscribes every type of psychological or narrative motivation – which appears to be a basic prerequisite for the musical quality of non-musical material to appear at all in the foreground of perception.

In the first system, all three layers are synchronised, preserving the perception of a unified gesture. Schnebel plays here with just one element, namely the alternation between the metrical similitude of the jumps and the non-metricised pauses. In addition, there is a ritardando in the third repetition of the jumping blocks. In the second system, an additional element is added to this structure: torso height is introduced as an element in its own right. Everything else remains the same. Instead of the ritardando, there is an accelerando at the end of the third group. For the third system, there are three decidedly new elements that remain constant within the staves: the pauses fall away, creating a greater, less inhibited flow of energy; the vocal action is performed offbeat for the first time, at the beginning of the jump rather than at the end. And the vocal changes to ‘hi’ (to be pronounced as ‘hee’) instead of ‘ho’. In accordance with the brighter vocalic ‘i’, a sound situated higher in the mouth, Schnebel now also prescribes a more upright torso position, enforcing a correspondence between physical movement and vocal colour.

The second part of the piece contrasts with the first one primarily in that, instead of the impulsive jumps, there is a flowing hop from leg to leg, accompanied by continuously flowing breathing that corresponds exactly to the individual hopping steps. The first line exposes the new basic material that then varies in the two following lines. Schnebel – and with him the performer – plays here in a virtuosic performance with rhythmical shifts between and within the individual layers, so that the levels finally fall apart completely and movement, having collapsed into its individual parts, stops. The length of the breaths is distributed differently over the number of hops; the hops become increasingly irregular in a series from right and left, and the torso movement varies in its own tempo through the rhythm changes. Finally, the tempo of vocal shifts gets faster and faster.

Figure 5: Second page of Dieter Schnebel: Der Springer (1989). Copyright by Schott Music.

Figure 6: Third page of Dieter Schnebel: Der Springer (1989). Copyright Schott Music.

In the third and last part, a clear reference is made to the beginning of the piece. There is however a final separation of the originally whole gestural unit: the exclamation of sound, which has up to now always corresponded to the energy of the jumps or hops – either as an offbeat collection of energy or as a descending energetic landing – disengages from this causal structure and becomes its own independent voice: the vocal accent always shifts by a sixteenth note against the jump. And finally, at the very end, there is a single moment that is motivated by content: a brief choked sound and then a relaxed posture, ‘as if to jump’ – but perhaps also as a sign of victory?

Composed Theatre and Postdramatic Theatre

For the field of Composed Theatre the sixties and seventies have been a period of enormous innovation in which new ideas arose faster than they could actually be assimilated. And, as is well known, this dynamic was driven by an impetus to break down the borders between the arts on the one hand and between the arts and everyday life on the other. There is, for example, the Happening that found its place in the fine arts but that was heavily influenced by John Cage; the Happening works with all kinds of material and deploys diverse performance elements in its presentational mode, leading eventually into Performance Art. There is Fluxus that, at least at the beginning, was mainly pioneered by people from the arts scene, but was understood as musical performances by its representatives. There is the dance scene, for which the collaboration between Cage, Cunningham and Rauschenberg or Jones was highly influential. Or the Judson Dance Group, which worked with chance operations à la Cage, or the German choreographer Pina Bausch who, from the late seventies, integrated spoken text into her performances, bringing them closer to theatre. There is the whole field of new electronic media, manipulated to serve individual artistic visions and leading on to the creation of new fields of mixed media, intermedia or, later, multimedia.

Thus, even if we pick out just a few examples from this whole field of performative art forms, what we see is that the separation of the arts can no longer be determined by the old criteria that dictated that music should work with sound and time, fine arts with colours and space, dance with bodily movement etc. The concept of artistic material – which at least within music was of enormous importance to the evolution of New Music – loses its power: fine artists integrate temporal aspects, musicians integrate spatial elements, dance integrates language and film etc. As with the other art forms, Composed Theatre is then best understood through an exploration, not of the materials used, but rather of the strategies and techniques it employs, how these materials are treated. Looking at Composed Theatre from the perspective of the theatricalisation of music, basically two forms have emerged: one that composes the different and independent elements and means of the theatre according to musical strategies and techniques and another that works with the intrinsically theatrical aspect of performing music with one’s body.

In the realm of theatre, Hans-Thies Lehmann has categorised developments since the early seventies as Postdramatic Theatre (Lehmann 2006). Some of the characteristics of this Postdramatic Theatre come very close to those of Composed Theatre. Indeed, where Lehmann speaks of the “musicalisation” of the theatrical elements, and points out that this not only means that music has become an ever more important part within current theatre but that the guiding concept was that of “theatre as music” (Lehmann 2006: 91), Postdramatic Theatre coincides with the idea of Composed Theatre. Unsurprisingly, then, some of the other symptoms of Postdramatic Theatre are identical with those so far identified with Composed Theatre; Simultaneity and non-hierarchy of the theatrical elements, for example. Consequentely some of the artists Lehmann includes in his Postdramatic Theatre are the very composers that we also name as representatives of Composed Theatre: Heiner Goebbels, Meredith Monk or John Cage.

As Lehmann tries to cover a very wide field of theatre practices over the last three decades, and as he is not trying to give a definition but rather a “panorama of Postdramatic Theatre” (Lehmann 2006: 68), it is not problematic for his project that some of the symptoms come close to contradicting each other. For example, he states that Postdramatic Theatre has the “structure of dreams” (Lehmann 2006: 84) but at the same time is characterised by the “irruption of the real” (Lehmann 2006: 99); and he says that Postdramatic Theatre is essentially a musicalised theatre but at the same time he suggests that it follows a “visual dramaturgy” (Lehmann 2006: 93). What is of interest for us, here, is only the question of how the concepts of Postdramatic Theatre and Composed Theatre relate to one another: Composed Theatre is part of Postdramatic Theatre because of the set of shared symptoms just mentioned, but Composed Theatre also transcends Postdramatic Theatre simply because it includes phenomena from music theatre, scenic concerts, musical performances etc.; that is, phenomena that Lehmann excludes because his focus is still on theatre and not on music, or more precisely the space in between music and theatre.

Where the two concepts overlap, Lehmann refers – besides the composers already mentioned – to the theatre of Robert Wilson, to Einar Schleef and his “choral theatre” (“Chortheater”, Lehmann 1999: 233) and finally to the theatre of Christoph Marthaler. In the case of Wilson, it is arguable that he should be seen as a practitioner of Composed Theatre. Obviously the precision and the formal character of movements, lights and choreographies make his theatre very musical. But this seems to be true in a metaphorical way rather than in a literal sense. Wilson’s artistic strategies and his thinking might more usefully be related to visual thinking than to compositional thinking. With Einar Schleef it is different. There is no doubt that the way he treats language, movement, gesture etc. is musically composed in a strict sense. In his Ein Sportstück (text by Elfriede Jelinek) we encounter scenes in which rhythm, intonation, articulation and dynamics are precisely and richly formed, led by musical rather than semantic demands. In that sense, it is a musical composition made with words, just as we find in the works of Kurt Schwitters, Hans G Helms, John Cage or Robert Ashley. Some of Schleef ’s scenes are even conducted by a hidden conductor, so that the onstage singers actually become a musical choir. And in the famous 7–8 Chor31 within Ein Sportstück we find a polyphonic structure between the rhythm of the physical movement of the choir (on different levels), the text, spoken by the choir in unison, and the rhythm that evolves from the bodies moving through sectors of light and no-light. These theatrical compositions by Schleef could be easily written out as scores, as David Roesner has demonstrated (Roesner 2003). Schleef himself, however, does not work in the way a composer would normally do. He does not compose ‘in his mind’ or ‘on paper’, creating a score in abstraction from the (sound) materials and in advance of his actors’ interpretation of that score. On the contrary, he works out his compositions together with his actors in rehearsals and approaches the final result in constant feedback with what he hears and sees. And the precision of these results is achieved, not by a precise form of notation but by repetition, so that even the finest nuances finally sink down into the corporal memory of the actors.32

Where the concept of Composed Theatre is concerned, it is important to note that the question is not whether (in this case) Einar Schleef himself understands his way of working as composing in the musical sense, nor whether he consciously applies musical strategies. Obviously, there are differences between composers who explicitly compose and theatre directors who may work with compositional means in a more intuitive way. But these differences are not decisive in determining whether or not a piece can be categorised as Composed Theatre. This, finally, depends on the question if it is adequate and revealing to describe the piece or its working process in that way or not.

The case of Christoph Marthaler is, again, different, as Marthaler is a trained musician and had worked for many years as a musician and composer of stage music before he started his successful career as a stage director. That Marthaler’s theatre pieces, especially the devised pieces, are driven and determined by the application of compositional strategies is quite obvious. His background in music is, perhaps, most evident in his use of repetitions or, more precisely, the constant and often provocative recurrence of the same material, sometimes in exact repetition, sometimes with subtle variations. These repetitions have a twofold function (as in musical pieces, too). On the one hand, they function structurally. Marthaler’s devised pieces33 do not follow a plot or story. They are situated in just one basic situation, similar in that respect to the theatre of Beckett or Ionesco. Typically it is some kind of waiting situation. The dramaturgy of the pieces – Marthaler himself often calls them ‘Abende’ (‘evenings’) – that evolves from these basic and static situations is mainly a musical dramaturgy, and working with repetitions is one of the basic strategies to organise the divergent material in such a way that it, nevertheless, holds together. On the other hand, of course, these repetitions are also part of the process of building meaning. The characters are waiting for something from the outside to come because they themselves lack any energy, any vision, anything meaningful and reliable enough to allow them to develop some sort of coherent action that could change their situation, help them ‘escape’. Instead they are occupied with absurd, often slapstick-like activities and rituals that bring the theatre of Marthaler close to the Theatre of the Absurd in which both the reference to mundane activities and the repetition are characteristic. And, most notably, from time to time these isolated, lonely characters of Marthaler’s theatre start to sing together with a beauty and perfection that is in stark contrast to their deficient individualities, and that momentarily gives a glimpse of a ‘metaphysical horizon’ of truth and sense that is extinguished as soon as they stop singing.

But it is not this direct use of music and singing that makes Marthaler’s theatre an important example of Composed Theatre but the organisation of the different elements in general: choreographic elements, noises and the musical approach to language etc. One of the devices of Marthaler’s theatre, for example, is the frequent transition between meaningful text or language and pure nonsense which, by the way, brings his theatre into a straight historical line from Dadaism. Very often this effect is simply achieved by several characters talking at the same time, a strategy that Marthaler himself calls ‘Ballung’ (‘compression’) and by which the focus slowly shifts from the meaning of what is said to the musical qualitiy of how it is said or rather how it sounds. The most impressive example of this is probably the speech that Graham F. Valentine performs in Stunde Null oder Die Kunst des Servierens. Here it starts with completely correct sentences – in fact, quotations of speeches that had been made by politicians, military officials etc. in 1945 after Germany had lost World War II, a moment of crisis that in Germany is often referred to as ‘Stunde Null’, that is ‘hour zero’. At first Valentine starts to switch between different languages, mixing German, Russian, French and English; but the more he goes on the more nonsense phrases appear, and it is not surprising that these nonsense sections refer to a sound poem by the Dadaist Kurt Schwitters.34 And, finally, characteristic of Marthaler’s theatre are the elements of Instrumental Theatre. Here, he was influenced and inspired by Mauricio Kagel, John Cage and by the work of Fluxus, with whom he also shares his humour.

To return to the twofold function of the repetitions, Marthaler provides us with a good way to address a more general point about Composed Theatre: when we speak of compositional strategies, or when Lehmann speaks of musicalisation as a symptom of Postdramatic Theatre, this is not a revival of the old form–content debate we extensively find in music aesthetics of the nineteenth century. The application of musical or compositional thinking and acting within theatre is not much served by a determination to separate the formal or structural aspects of theatre from its content or meaning. On the contrary, what this theatre is about, what it makes us experience, is conveyed by means of musical devices. It is no longer the written text, the drama, that stands at the top of the hierarchy of theatrical elements but – in a non-hierarchical, postdramatic way – every element can be part of the meaning-making process, and can shift from the foreground to the backgound of perception of any single spectator or listener. And this constant shifting is facilitated by compositional devices and strategies.

Conclusion: Composed Theatre – mapping the ‘scene’