Chapter 3

‘Happy New Ears’: Creating Hearing and the Hearable

Petra Maria Meyer

One makes a cross-check: if during the performance of a piece of music in a concert hall a sound rings out (a chair that falls over, a voice that doesn’t sing or the coughing of an audience member) then we feel that something in us is torn, there is a break in some substance or a rent in some law of association; a world falls apart, a spell is broken.

(Valéry 1991: 71)

Historically, music has always been an indicator of changes in listening habits and perception. These changes have also influenced other art forms that work with musical structures and compositional processes. In as much, music is a significant element of theatre, dance, performance art, of radio and film art. Also in sound installations in the field of fine arts, if nothing other than everyday sounds are heard in a concert hall and ‘a chair which falls over, a voice which does not sing, or a spectator who coughs’ are declared pieces of music. They are acoustic events with which ‘the world disintegrates’ and which French philosopher Paul Valéry cites as a cross-check. The legendary 49330 by composer and Nestor of New Music, John Cage, performed in 1952 in the Maverick Hall in Woodstock (USA), became an acid test through which the world opened itself anew.1

Pianist David Tudor entered the stage, sat at the piano, opened the lid and closed it again. This procedure was carried out three times. Not once did he place his fingers on the keys, not one sound was heard. Nevertheless, a composition by John Cage was performed, in an interpretation by the pianist David Tudor, who allowed the piano to be silent – Tacet2 – it is silent. The composition has a real time of 49330 and is divided into three movements, which the pianist structures in gestures. Thus, a new audible space was opened up and a new auditory experience was cultivated towards ‘everyday sounds’, which have always surrounded us, by nothing more nor less than a temporal frame with which the frame of concert music was broken. Since ‘Tacet’ concerts no longer have to consist of musical notes, and silence and sounds are no longer treated as opposites. Moreover, it has become clear that reality and ‘life’ consist of many musical events that ‘art and life’ can intertwine and music can become theatre – not least due to the use of gestures. John Cage has always been particularly close to the theatre arts, not only due to his long co-operation with dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham.3

You see, at the beginning, the music experts didn’t want to accept my work as music. In the thirties, they said frankly that what I was doing was wrong. But dancers accepted it. And so I became almost immediately accepted in the theatre world, and the theatre encompasses the fine arts, poetry, singing. Theatre is where we are at home […] I think the thing that differentiates me from others, […] what made it different, was that it was theatrical. My experiences are theatrical.

(Cage in Furlong 1992: 91)

From the musicalisation of theatre by Adolphe Appia through the theatricality of music by John Cage, the ‘instrumental theatre’ of Mauricio Kagel up to the ‘optical music’ of Robert Wilson, on to the ‘conceptional compositions’ of theatre by Heiner Goebbels or the multitude of forms in which Christoph Marthaler stages theatre as music, theatre has shown itself a model medium of new compositional processes in interaction with music and the acoustic arts.

For the world of tonal music, litmus tests existed even before Cage. Here, one can refer to futuristic concerts using self-constructed sound-makers4 and the ‘musique concrète’ of Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, which in the 1940s used randomly found sound material, machine noises or animal sounds as compositional material, and manipulated these electro- acoustically. This also revolutionised music. Today, it is possible to say that atonality and twelve-tone music did not drastically change music. Rather, the multimedial ‘emancipation of sounds’ and music’s discovery of silence were innovations which paved the way to acoustic material dissolving its boundaries in many, widely differing arts and media. In the course of these changes, which included tones made by the body, the sounds of breathing, sighing or screaming, which dealt with a sound poesy of the Dadaists, with Lettrists or representatives of ‘poésie sonore’ and with a ‘théâtre du cri’ of Antonin Artaud in theatre, poetry and acoustic arts, the listening experience and the ways things are heard and listened to have all altered to some extent.

The further line of thought is three-part. First, the efficiency of the sense of hearing will be established, while conducting a differentiation of the various ways of hearing or listening. Secondly, a fundamental ‘acoustic turn’ will be noted, which owes something in particular to a medial-technical change. Both parts indicate compositional processes within new frame conditions of hearing and audibility in theatre, which thirdly will be reflected using concrete examples. Composed Theatre is always an exercise in listening.

Hearing, listening and ‘close listening’

In Ancient Greek thought, where the foundations of occidental thought, speech and even history are to be found, the sense of hearing was highly esteemed. This seems physiologically plausible since the sense of hearing shows a particular perceptiveness for temporal processes and is capable of paying attention to the smallest dynamic differences. Erwin Straus in his seminal book Vom Sinn der Sinne [Of the Meaning of the Senses] formulated this precisely by saying: “In seeing we detect the skeleton of things, in hearing them their pulse” (Straus 1956: 398). While the eye is particularly adept at measuring, at estimating spatial dimensions with regard to recognising structures and at recording all that is permanent or constant, the sense of hearing’s capabilities lie equally clearly in its increased ability to perceive temporal changes. Since the ear can perceive the smallest of sounds and amplitudes, it can recognise minimal changes. Always trapped in time, in a state of tension between remembered past and expected future, the ear records events at the moment they are executed, in their very creation. If the eye is particularly responsible for grasping static situations, the ear is for dynamic processes. While the eye adheres particularly to present conditions and even tends to dominate the present, the ear opens itself up to temporal processes, to continuous events, which transcend analytical division. In contrast to the sense of sight, which observes what is seen from a distance and often has to keep its distance to see at all, the sense of hearing is an external sense, which is characterised by an absence of distance. A listener is always in the thick of things. The external sound space presses into the interior, the listener is surrounded by the sounds, is penetrated by them.

Since hearing is operative not only to the front but all around the listener, it can follow sounds in all directions in a given space. With the help of a reverberation or an echo the ear can also determine the size of a space. It can differentiate simultaneous acoustic sounds in a space. One talks of the ‘cocktail party effect’ in order to make clear that hearing can pick out and understand a single voice from the miscellaneous sounds of heterogeneous, acoustic mixes. In this respect anthropologists regard the sense of hearing as the sense of time and space par excellence. And from a psychological point of view, the sense of hearing records spatial-temporal situations like no other sense.

In this context then it makes sense to differentiate between hearing as a physical process and listening as a psychological act. Furthermore, different types of listening (and perception) can also be distinguished. Listening to signals is practised by humans and animals.5 The ear is the ‘preferred sense of attention’, which Paul Valéry claims keeps watch where the eye can no longer see (Valéry 1993: 33). A second type of listening in the sense of deciphering a code and its signs or essential contexts can be understood as specifically human. According to Roland Barthes, this second type of listening is also particularly religious (1990: 254). The Ancient Greeks opened their ears to the sounds of the leaves on the Dodona oak trees and deduced prophecies from these natural sounds.

One must add an attitude to one of Barthes’ marked practices of listening, which attempts to postulate and detect a ‘beyond’ of the meaning (Barthes 1990: 253), that is, it tries to shake off dark, unclear, dumb meaning. It is this attitude through which the worldly events of life are listened to. A common sense of listening and examination from Heraclitus via Leibniz, Herder to Nietzsche becomes more sensible for a “total sound of the world” (Nietzsche 1967–77: 817).

If theatre is staged not only from the opsis, that which is seen, but also from the akoe, movement which is heard, then this sensibility is evident from Greek tragedy, which according to Nietzsche was born of ‘the spirit of music’, to productions by Einar Schleef, who by using a particular sense of rhythm staged multiple voices in each dialogue in exact vocal instrumentation and choral intensity. Being aurally open to the richness of changing melodies in different languages as well as the acoustic accents of diverse cultures is a quality to be found from Peter Brook to Ariane Mnouchkine to Heiner Goebbels. In theatre, however, not only are the many-voiced and broad range of vocal tones in varying situations made audible, but the auditorium can be staged as part of the listeners’ space, thus opening up as an acoustic circle. Theatre-makers know how to design their surround- environments diversely in terms of acoustics. They constantly draw upon their audiences’ particular hearing abilities in different ways when they introduce sound objects from different directions and, like Robert Wilson, use them as striking key sounds. Wilson, who in stagings such as Black Rider or Alice, structures heterogeneous, associatively linked time- spaces in dream logic, thereby follows a particular perception of hearing, which has also been deliberated in philosophy.

Where a ‘common sense of hearing’ ensues from the organ which does not shut down at night, one can find from Leibniz to Nietzsche an inclusion of diurnal and nocturnal petite perceptions (Leibniz) of dream perceptions and of the unconscious. The sense of hearing permits no fixed demarcation between waking and sleeping, between waking consciousness and dream consciousness.

Friedrich Nietzsche in particular developed a physical-philosophical, seminal ‘philosophy of hearing’ as well as an ‘acoustic-gestural paradigm’.6 Since the sense of hearing is a perception which of its essence is non-distant, it remains involved with body, life and soul. With regard to the new definition of ‘common sense’ as a ‘physical common sense’ it therefore plays a central role. It does not however become the new primacy of the senses. Seen both physiologically and philosophically as the physical aperture to the world, the sense of hearing is inextricably linked to the other human sense organs in such a way that removing the ear would result in a limitation of one’s ability.

Even Henri Bergson in his time and image philosophy of the physical, which has considerably influenced film theory (cf. Deleuze 1989 and 1991), remains strongly oriented towards the acoustic phenomenon field, without taking a one-sided slant towards just one sense organ. He constantly draws examples from the acoustic field in order to clarify limited cognitive ability due to physically measurable, chronometric time, setting this in opposition to an uncountable and immeasurable ‘experienced time’, perceived through the great diversity of discoveries and perceptive experiences. In this context Bergson reminds us of the striking of a clock, which may be perceived in two ways. Taking in the sound in the sense of measured time, the hearer would count four homogeneous strokes in space and come to the perceptive impression of a total of the sounds heard: the clock has struck four, it is four o’clock. However when attending “to every single awakened perception” the hearer reaches a completely different impression of the sounds: “instead of lining up next to each other, they merged into each other” and sound like a “musical phrase” (Bergson 1994: 96). If the ‘spatial time’ suggests that different points in time appear homogeneous, ‘experienced time’ creates the experience that there is no homogeneity in the real-time experience, since there can never be two identical points in time. With each repeated chime of the clock, nothing is repeated since the second sound differs from the first in that it is the second and as such is perceived by one’s consciousness at an altered configurative level. Due to this fact, the second sound has a different quality for the perceiver from the first. The “durée”, designated by Bergson as a “qualitative diversity” (1994: 81) of time, which is experienced as a qualitative process of change and creation, is thus particularly accessible to the sense of hearing, requiring however a different type of listening than the deciphering type.

When theatre no longer serves to represent a plotted dramaturgical course or narrated time, but rather seeks to make time an experience, then it creates ‘time within time’, experienced in ever changing ways, as Vladimir expresses in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. From Beckett to Wilson, decelerated courses of movement and events as well as multifarious games with repetition and variation in reduced, even minimalist stage compositions reveal that theatre artists increasingly compose theatre with a changing attitude as regards listening. In this context, Bergson’s bias towards the creativeness of time appears to be seminal, for it corresponds to the central value which has been adapted by a no longer identity-constituting, difference-generating repetition used today in compositions of widely different media (Cf. here: Meyer 2004: 227–37). “Would it be repetition? Only if we thought we possessed it, but since we don’t, it is free and we are too” (Cage 1987: 141).

A qualitative and difference-oriented listening attitude also corresponds to a third form of listening, exemplified in various contexts by Roland Barthes. This form of listening is aimed at significance (Barthes 1990: 249). It does not owe itself to the appearance of a significat as the effect of recognition but is rather the effect of the “mirroring of the signifiers which are continually competing to be heard, which continually produces new ones without ever causing the sense to shut down: this phenomenon of mirroring is called significance (it differs from ‘meaning’) […]” (Barthes 1990: 262/263). With regard to this “field of art” (1990: 262) Barthes refers to the difference between listening to a piece of classical music and a composition by Cage. If based on his education and sensibility the listener of the classical piece is required to decipher from the piece what he can – since the composition is usually encoded, just as the architecture of the same era – then he or she is required to do so differently when listening to Cage: “[…] with Cage’s music however I hear each individual sound one after the other, not in its syntagmatic expansion but in its raw and quasi-vertical significance” (Barthes 1990: 263).

In other studies, Barthes clarifies this significance by naming it signifiance.7 In contrast to the sign-theoretical meanings of Ferdinand de Saussure’s signifiant and signifié, semiotically, signifiance is something which ‘happens to a signifier’, which sensually generates meaning, that is, it is that which appears due to the mostly neglected materiality and mediality of the sign-carrier and can trigger another associative chain of reference.8 The graininess of a voice (Le grain de la voix), the dynamic of a movement, the idiosyncrasy of a gesture or the outline of a piece of handwriting are significant here since a signifier refers to a movement of the body (Barthes 1990: 258), which originates from the voice or the gesture of a musician when playing – something which Mauricio Kagel did systematically in his ‘instrumental theatre’. The shift in attention of a signified to a signifiance corresponds to the shift in attention undertaken by the composer Kagel: to produce from the tones to be composed the musical practices, the notes and sounds via gestures.

According to Barthes, a central significance of listening as a sensually generated sense, which is not the same as meaning, has only become possible since the discovery of the unconscious and of a different kind of psycho-analytical listening with evenly suspended attention. Listening is no longer performed only in complete consciousness and as an intentional act. An altered hearing ability rather has the function of “gauging unknown spaces” (Barthes 1990: 261). Barthes argues that in this sense not only the unconscious is to be heard but also the implied, the indirect, the omitted, the additional, the extended and polysemy, overdetermined and the overlapping. Significance, which in this sense unfolds within this inter-subjective space, requires “attention” to the “in-between of body and discourse” (Barthes 1990: 259). It is geared less towards that which is said than that which is not said or even prohibited. Nothing that is said or makes a sound is to be heard. Rather, this type of listening is directed at whoever is talking and at how something is heard. The way and manner in which and through which something is heard is at the same time formed by a media-technical modification.

‘acoustic turn’

In the nineteenth and twentieth century, not only optical media such as photography and film altered their perceptions and commemoration culture. The advancement in sound recording and playback technology, powerful loudspeakers and Dolby Surround systems were part of a sensual generation of meaning, which today enables a multifaceted art and culture of listening. The range of artistic approaches composed of notes, tones and sounds, which work with the whole diversity of the acoustic world, is correspondingly multidisciplined and multimedial. These arise from acoustically altered, social frame conditions. Radio communication, telephones, radios, audio books, Walkmans, podcasts, ‘audio on demand’ and other auditive potentials and offers of web-based communications have made this central position of the acoustic dimension within the cultural change to a sensual certainty.

The resultant central importance of the audible, the increasing acoustic designs in various social fields and a constantly growing range of acoustic arts allows us to speak of an ‘acoustic turn’.9 Although artistically and media-pedagogically this ‘turn’ has long been completed, academically it is still slowly being processed. While due to the primacy of the optical, hearing and the auditive elements in audio-visual culture were too long ignored, artists have been contributing to the dawning of a perception-consciousness for some time and have opened up an experimental field of new ways of listening in completely different media.

On the radio, poets, composers, artists and theatre-makers have brought forward in audio plays, acoustic art, sound art – the names vary – individual artistic forms generated from media-specific technology, which have advanced to seminal art forms and have aesthetically completely altered not only radio but also theatre, film or sound installations.

Cinema and theatre are particular listening spaces for acoustic stagings in which sound design and soundtracks are becoming increasingly important. The common elements of a temporally limited theatrical or musically composed structural sequence, which radio plays, film and theatre plays all have in common, have led to diverse bi-medial concepts. Soundtracks become audio films in radio, radio plays are performed on stage and often presented as performance art. Theatre or audio play dramaturgy has changed to intermedial dramaturgy. Composition has become a multimedial structural principle. Composers such as John Cage or Mauricio Kagel composed theatre, film and/or radio plays in equal measure. Kagel’s ‘Componere’ became the artistic practice of organising time, which he applied to a wide variety of material and media. He composed using “sounding and non-sounding materials, actors, cups, tables, omnibuses and oboes” (Kagel 1982: 121).

In the following I would like to treat various, more concrete examples in greater depth. They originate from three different areas of theatre, from dance, music and straight theatre, and should make clear the overall relevance of acoustic and compositional concepts for theatre as well as their diversity.

In the theatre of the twentieth and twenty-first century there was and has been acoustic staging at all levels. The structuring of both time and space, a creation of atmosphere, an atmospheric design or the creation of tension, as well as characterisation have been attempted acoustically. In dance also, the acoustic level has taken on a central significance. A heightened awareness that dance allows the use of what happens in the visible stage-space in interaction with acoustic events within various listening spaces, can also be found in the dance theatre of the 1970s. The example of a neglected choreography by Pina Bausch should also support the relevance of a third form of listening, which Roland Barthes “ultimately (regards) as a small theatre, in which those two modern deities wrestle with each other, evil and good, power and desire” (Barthes 1990: 260).

Bluebeard – Listening to a Tape Recording of Béla Bartók’s Opera ‘Duke Bluebeard’s Castle’, a choreography by Pina Bausch

The dance theatre of Pina Bausch pursues psychological and physical interests, consciously eliminating the division between dance and theatre. Choreographer and dancer Pina Bausch, who died in 2009, played with signs of signs of a cultural behavioural code, referring theatrically to the social system and social – particularly gender-specific – roles, in an excessive presentation, recognisably alienated. By means of the language of movement, she also transcended cultural encoding by stripping off all masks in an attempt to refer back to traces of a body memory. At the end of the Expressionist dance movement she set an internal scene of soulful-thoughtful processes in opposition to a decorative theatre scene and the illusion of a plotted ballet. In her choreography, this led not only to unusual series of movements, through which the intensity could be released, but also to other acoustic and musical concepts.

Even the title of the choreography ‘Bluebeard – Listening to a Tape Recording of Béla Bartók’s Opera “Duke Bluebeard’s Castle”’, which Pina Bausch staged in 1977,10 emphasised the audio-visual structure. Since Pina Bausch’s choreography lasts approximately 120 minutes, whereas Bartók’s opera only lasts 60, one surmises someone has approached the opera to which Béla Balázs composed a libretto as a ‘stage ballad’, on which the opera is based11 in a way that orients itself towards the genre of tape composition. Originally introduced into the world of sagas as a fairy tale by Charles Perrault, the Bluebeard material was taken up by Ludwig Tieck and in 1797 became a folk tale with widespread effect. In 1910, Hungarian author Béla Balázs, who today is better known as a film critic and was at the time particularly interested in fairy tales came back to the material, and his friend Béla Bartók composed the music. The opera was first performed in Budapest in 1918.

Figure 1: Sketch of the stage design for Bluebeard’s Castle by Rolf Borzik.

In the opening sequence of Pina Bausch’s choreography one sees dancer Jan Minarik start the tape recorder and approach a woman lying on the floor. The floor is covered with leaves and the female dancer, who also characterises Judith, is lying on her back.12 She holds both arms stretched upwards while Jan Minarik lies on top of her. Together they slide noisily across the stage, then he gets up and stops the tape recorder, rewinds and starts the musical sequence again. He once again approaches the woman lying on the floor, lies on top of her again and they slide across the floor, again and again.

A ‘sound machine’ becomes the stimulator of desire and in equal measure memory’s energy source. Since both the musical course and the continual plot course stops and restarts, a different intensive temporal ordering of physical movements is created, which can also be understood as memory movement. In variations of the Freudian process, to remember, repeat, work through, one could talk in this case of repeating, working through, remembering. This process allows an intensive penetration into the memory movement of the body, which Pina Bausch tried to release in the rehearsal process with her dancers.

Via this dual process, which draws on human body memory as well as on a distorted, thereby altered reproduction technique of a tape recording as memory medium, not only memories and expectations due to a foreknowledge of Bartók’s opera are damaged. Rather, an enormous increase in the intensity of the movements is effected. Observed from a media-studies point of view, the disturbance in the technical reproducibility brings about an increased development of awareness of the media technology on the stage, causing a reflecting upon the media-specifically different intensity of repetition and difference in theatre. Since for each reproduction – which varies from slightly to considerably in its beginning and its end, never exactly repeating the same musical sequence – the same, but never identical, scenic action is performed several times on stage. Thus the choreography simultaneously transfers the reproduction technique to the repetition structure of theatre, where only difference is always repeated. Another qualitative time experience, which enables an intermedial interplay, becomes equally manifest: with the aid of the tape recording montage an emphasis of time is just as possible as a manipulation thereof via fast-forward or slow-motion, forward and backward leaps in time, simultaneity of the past and the present. In the interaction with the choreographed movements, these time phenomena can be experienced as durée in the sense of Henri Bergson.

This conception of a particular memory space uses an intermedial procedure to help us recall Bartók’s opera in our cultural memory in a new manner, while opening up new time- spaces for dance via altered compositional procedures. If in Pina Bausch’s choreographies one usually finds collages of various musical interjections from different genres (easy listening, jazz or classical music), here an opera is played from a tape recorder and composed anew using the ‘cut-up method’.13 The opera becomes the raw material, from which altered forms of a tape recorder composition can be generated in a self-referential process. Not only compositional but also psychological possibilities can thus be exploited. A tape may contribute to repeating the associative sequences as well as interrupting and diverting fixed associative series. In this sense, media technology becomes thematic and scenic. It begs the third form of listening in the sense of Roland Barthes, which focusses on what happens to the listener as well as on power and desire in theatre.

Although Bartók’s composition here experiences a transformation, is dismantled and composed anew, each fragment retains the remembrance in the material. Basic thematic focal points in the story of Bluebeard, who kills his wives and is the prototype of desire and power, are strikingly sensualised. The painfulness of the scene depicting a failing sexual relationship increases rather than decreases with each repetition. This heightened painfulness also becomes perceptible at the acoustic level. Emotional connotations of the rustling leaves give rise to associations of rape and complement the sounds of the basses and cellos from the tape, which surge at the listener’s ear with a melody similar to a folk song. A multitude of body sounds, of a body sliding and running over leaves, of seething and heavy breathing, of various bodily contacts etc. are presented along with the rich palettes of colour, sound and sensation of Bartók’s non-illustrative yet suspenseful, intensive music. Here, dance puts the effect of the body itself on stage audio-visually. These acoustic accompaniments and vocal sounds and cries which accompany the tumult in the body, the noise potential made audible by the physicality of a human body and the materiality of things, directly oppose the transcending power of opera music in their concrete worldliness. Using an intermedial intervention Pina Bausch brings the music back down to the ground of the physical aspects of being human and the world of things and equipment.

Along with the moveable tape machine, which the Bluebeard figure14 Minarik uses violently against the Judith figure, “direction vectors, speed and time” (de Certeau 1988: 218) are quasi-integrated into the spatial concept of the stage designer. In a multitude of ways, the audience experiences compositionally, scenographically and choreographically that something is being done to this place and that space is being constructed in such a way in performance.

Figure 2: Scene from Bluebeard – Listening to a Tape Recording of Béla Bartók’s Opera ‘Duke Bluebeard’s Castle’, a choreography by Pina Bausch. Photograph by Ulli Weiss.

Scenographically the tape becomes the musical sounding body and handy object on the stage conceived by Rolf Borzig, since above and beyond its function as a prop it becomes a co- actor, enabling a transformation of Bartók’s opera. Along with this transforming and rendering conscious of the media-technical composition of music, thanks to an intermedial strategy, a choreographic work is created in the performance space generated by the movements of the dancers. Here, the audio-visual emphases of the physical aspects of the human body and of the space itself are essential. Borzik’s space concepts for choreographies by Pina Bausch always offered lots of space to walk, skip, strut, shuffle, hurry along, run, for walking steps and sliding bodies. In this case it always concerns the specific movements themselves and their acoustic expression, their audio-visual course in performance. The spatial concept of the scene as performed is accordingly expanded via a leaf-covered floor space, used and danced upon with sounds, which is quasi-penetrated by natural and cultural space, inside and outside.

In thematisation of the choreography Bluebeard – Listening to a Tape Recording of Béla Bartók’s Opera ‘Duke Bluebeard’s Castle’ as a prototypical example of acoustic and compositional practices in the field of dance theatre is self-evident simply because the space- time feeling of Bartók’s opera is decidedly altered and the transcendental power of the music forms a paradox to the process of the tape composition. At this level of the perception, Pina Bausch’s choreography proves itself also to be in opposition to a deciphering listening. The dismantled opera corpus allows no recognitive hearing. Instead, it enables a new encounter with a listening space ‘tuned’ by Bartók, which is enriched with sounds and voices of the physical space of action.

If Pina Bausch enabled a remembering of the new, which John Cage had already strived for using non-determination, via strategies of difference-generating repetition in intermedial interplays of tape compositions and dance, Heiner Goebbels exploits repetition differently again in order to release the richness of the acoustic.

Die Wiederholung/La Reprise/The Repetition, a theatre composition by Heiner Goebbels

The Repetition, a multilingual musical theatre production, which the composer, musician and radio playwright Heiner Goebbels produced in 1995 in the ‘Bockenheimer Depot’, the auditorium of the Frankfurter Schauspielhaus and the TAT (Theater am Turm), is based not on a libretto nor on a dramatic text, but on a text- and music-collage. The title refers to the philosophical reflections from Die Wiederholung (La Reprise/The Repetition) and other texts by the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, who wrote as a poet under several pseudonyms. Excerpts from different texts by Alain Robbe-Grillet also appear as does a transformation of the film script L’ànnée dernière à Marienbad by Alain Resnais and a musical key text amongst the intertextual references: the song Joy in Repetition by Prince. Accordingly, Heiner Goebbels subtitled the performance text of The Repetition: ‘nach Motiven von / based on / d´après Kierkegaard, Robbe-Grillet & Prince’. Additional musical set pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Johannes Brahms, Frédéric Chopin und Heiner Goebbels himself were also included. Together they constitute a quasi-heterogeneous text material spanning existential philosophy and nouveau roman and musical material, which in this theatre composition ranges from the classical music of the eighteenth and nineteenth century up to the rock/pop and jazz of the twentieth.

The cast can be seen as the consistent equivalent of a programmatic musicalisation of the theatre. It is moreover multilingual, due to a multiple duplication of the language sounds: Marie Goyette is a French-speaking, classical pianist, John King an English-speaking musician and Johan Leysen a German-speaking, Dutch actor.

Here, too, the author follows the concept of figuration and transfiguration, for the roles of the actor and musician on stage are not the representative embodiment of characters. Far more, they are actors who appear using their own names. In the course of the piece, the repeated, and thus constantly varyingly de- and re-semantisised text material is divided between them. Their corporeality is the medium for scenic figuration and transfiguration, the voice is a changing instrumentalisation of repeated text material.

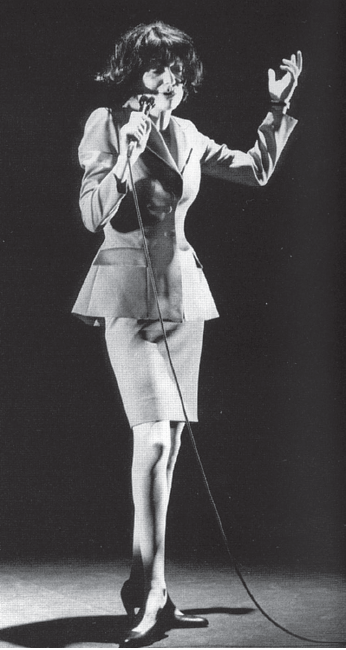

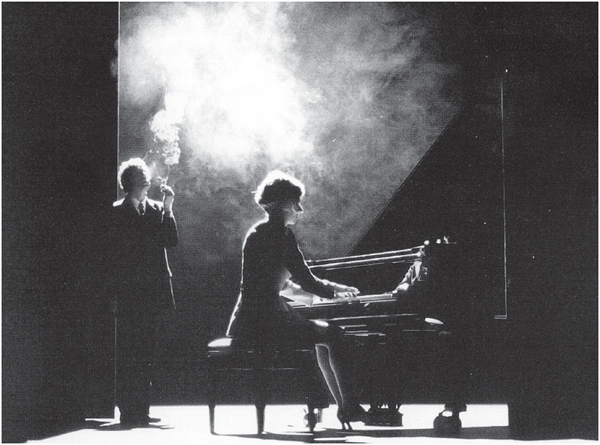

Figures 3, 4 and 5: Marie Goyette, John King and Johan Leysen in Heiner Goebbels’ Die Wiederholung / La Reprise / The Repetition. Photographs by Wonge Bergmann (3–4) and Harmut Becker (5).

Like Pina Bausch, Heiner Goebbels also uses repetition not only as a focal point of content but as a basal structuring principle, relinquishing coherence in a linear context, in order to generate sensual meaning in a different manner. Kierkegaard’s central question of a philosophical experiment, “whether something loses or gains due to its being repeated” (Kierkegaard 1955: 3), here becomes a test of theatre as a medium of non-repetition par excellence.

The listener is thus manoeuvred back and forth between attitudes of listening via repetition and differentiation of a text in various languages. The attention of the listener is shifted from the sense of the word to the sense of the sound and at other times from the sense of the sound to the sense of the word according to the comprehensibility of each word. Repetition thus proves itself to be an iterative dislodging in an acoustically musical linguistic movement of transformation. This shifts from one actor to another, from a female voice to a male, from one language to another, from a foreign language to one’s own, from a linguistic ‘abroad’ to ‘home’, from the rather silent and sounding language to a spoken language. Although the text is repeated, the difference triumphs, which can only be experienced thanks to the repetition. The effect of that which has been sounded and said twice is multiplied, without its novelty value wearing off. In fact, the repeated text is represented in varying ways by the difference in the vocal structures of the two languages German and French. Thus Søren Kierkegaard’s perception of the relation between repetition and remembrance can be physically experienced through hearing: “Remembrance and repetition are the same movement just in opposite directions. For what we remember, has been, is repeated backwards, whereas the actual repetition is remembers ahead” (Kierkegaard 1955: 3). What is seen is quasi the gestural and proxemic sensualisation of the process by an actor.15 A remembrance stimulated by repetition from the very beginning characterises the events at the same time as time markers, whose sense of relation changes in the course of performance time.

An aesthetic of interruption can also be found in Goebbels’ staging, in which an auditively and visually multiple ‘play’ of fade-ins and fade-outs takes place. It operates sometimes tentatively and sometimes with abrupt clarity. A change between accelerated, dynamic and stopped courses of events, ‘instants immobilisés’ according to Robbe-Grillet, at the same time combine thematic motifs with compositional processes.

In this context, one is reminded of Cage’s ‘Tacet’. A silent stage minute is quasi set free in a silent scenography consisting of one minute of stillness, a minute of an absence of movement within a halted event, which Johan describes in the performance as ‘one minute’s non-motion’.16 When this sequence is introduced with the words, “from the auditorium you hear not the faintest sound”, then the audible occurs as a de-staging in the auditorium and around it – or not. Not only does Heiner Goebbels’ theatre composition generate sensual sense but is also a meta-theatre of self-reflection. In this self-reflection, the relation between theatre and music as well as between classical or rather ‘serious’ music and popular music is included at diverse levels.

‘Prince and the Revolution’ was not just the name of the band at the beginning of mega- star Prince’s career; it is also the title of a lecture by Heiner Goebbels, which, significantly, has been published, five times in different forms. This seems justifiable inasmuch as the composer accuses the classical new music of a wilful ignorance with regard to the rock and pop sector, thus causing a considerable delay in musical form principles, which had already been inventively tried and exceeded in other musical areas. According to Goebbels, it is disco culture in particular and an experimental subculture to which innovation drives can be attributed. From this he draws the appropriate compositional consequences: an openness and sensibility of perception for a permanently changing musical reality become conceptional.

In working with available material, de- and re-contextualisation, according to Goebbels, is only acceptable as a new artistic practice as long as it is not randomly re-worked. The foundation for this should be a reflected process equipped with a consciousness of history and regard for the material (see Goebbels 1989). In the age of collections, of nouveau roman and of the king of crossover, Prince, nothing less than such a compositional concept of a composer is performed self-reflectively by the theatre composition The Repetition, which so to speak puts itself to the Kierkegaardian test of “whether something loses or gains due to its being repeated”. Here, Goebbels opts for the revolution of repetition in Robbe- Grillet’s work and the revolution of the mix in Prince’s, this particular musical personality who combines “soul, motown, rhythm & blues, country, folk rock, jazz” (see Goebbels 1989) in his own particular way, a unique way which shows itself in the mix, the sound, the microphonisation of the voice or the use of echo, in the macrostructure of the arrangement and the microstructure of each detail. This is what the ‘revolutions’ of Robbe-Grillet and Prince have in common: they are transgressions, excess in the manner of how something sounds, is combined, mixed, interwoven, how it becomes dynamic, energetic, effective, exciting and surprising, beyond revolutionary content and ideals.

Repetition, in Goebbels’ music theatre production of the same name, proves itself to be a different ordering of the interlacing of various events using a reduced range of permutable elements. As in Pina Bausch’s choreography a spatial concept by Erich Wonder supports the stage action. A curved wall on the revolve ensures that the room itself begins to move, it is altered, it withdraws from view and reopens partly or in full to the audience’s gaze. Varying views of the space, perspectives and panoramas are created due to time becoming spatial and space becoming temporal as the revolve is used as space journey with no particular direction, clockwise or counter-clockwise. The theatre machinery runs in no one particular direction but rather in various directions simultaneously. Mutually connected sequences occur discontinuously, cues emphasise the heterogeneity of the audible and visible. Thanks to repetition there even occurs a sense-stimulating shift in attention and a reflection- provoking paradoxical time specification.

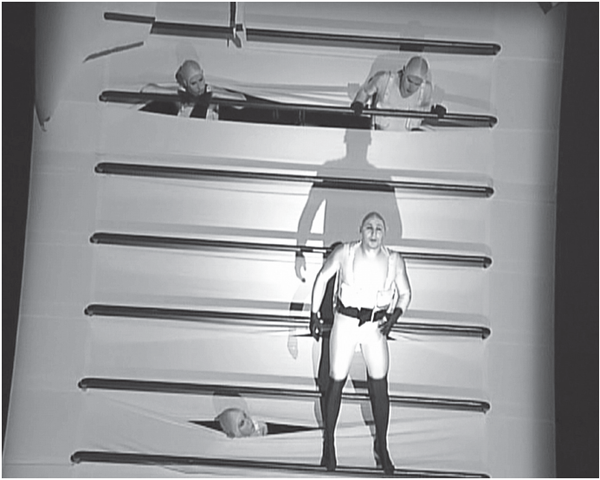

Figures 6 and 7: “I knocked, didn’t you hear?” / “Yes: I said come in” (Repeated lines from different scenes from Heiner Goebbels’ Die Wiederholung / La Reprise / The Repetition). Photographs by Wonge Bergmann (top) and Hartmut Becker (bottom).

The musical treatment of language in Goebbels’ staging is seminal for spoken theatre. Differences between the sounds of the various languages serve to emphasise a constantly varying time dimension from one language to another. This is further elaborated in the switches between emphatically slow, even hesitant speech to rapid, witty exchanges.

In Goebbels’ work the word material in this manner is mainly determined by its temporality and thus dealt with as music, as opposed to the usual manner of dealing with word texts, in which the temporal dimension has virtually no effect on the content of the words. This structuring principle of repetition simultaneously connects the unfolding of text time to the remembrance time of the observer who is quasi challenged to recall so that, what has previously occurred through remembering penetrates that which occurs later. Thus the perception of the repetition varies due to this time-based penetration. This variation provokes the observer to listen in a different manner and challenges him/her to be more open to what sensually occurs on the level of linguistic signs.

Here, composer and radio playwright Heiner Goebbels clearly draws on his radio experience. Acoustic art in radio works with language, sound and music as acoustic materials with equal rights. This art has experimented with many forms so that the similarity of language and music may be experienced: that they are sounding events in time. More recent theatre productions also draw thereon.

Letter to the Actors, ‘Theatre of the Ears’ by Valère Novarina

Following in the footsteps of Antonin Artaud and Samuel Beckett, French-Swiss writer, director and painter Valère Novarina programmatically named his theatre a ‘Theatre of the ears’/‘Le théâtre des oreilles’ (Novarina 1996) declaring the actor to be an oral and sonorous excretion organ. Novarina wants a “pneumatic actor” (1993: 95) and harks back to pneuma, which in Ancient Greece comprised body and spirit, undivided. Thus in this sense the actor’s breath is his spirit. He takes language as material which of itself knows where it should go, knows as language whereof it speaks and therefore requires no cognitive author subject that gives it access to reason. Rather, he aspires to an understanding arising beyond the intellect: a physical, existentially anchored hearing and listening that takes over from the abstractly comprehending understanding. A staging of Novarina’s Letter to the Actors, a play, which director Philip Tiedemann staged at the Düsseldorf Theatre in 2005/2006,17 should in conclusion serve to clearly exemplify the characteristics of the ‘Theatre of the Ears’.

Figure 8: Scene from Brief an die Schauspieler by Valère Novarina, directed by Philip Tiedemann.

The first thing the audience perceives in this play, however, is writing. At the opening a curtain covered in writing can be seen (see figure 8). The letters are blue on a whitish- transparent background, which like a shower curtain resists the penetration of the glance while ever hinting at what is behind it. In this way from the very beginning the semitransparent curtain allows an act of seeing that is linked to the imagination and inner vision. The audience simultaneously hears a simple percussive tone sequence to which the actors move. Each actor wears a blue-white leotard that covers their whole body, leaving only their face to be seen. Yet it is not only the faces, which serve to tell apart the shapes in, the same colours and clothes. Varying colour distributions of white-blue to blue-white, varying letters on their backs mark the difference rather than the individuality of these actors who otherwise remain nameless. Already on the level of outward appearance such anonymous heterogeneity is enacted. This serves to abstract from a psychologically realistic character conception to the benefit of an intensity of physical processes. Accordingly the audience’s attention is directed to other events. A strongly built man wears mainly white and appears particularly physical as a result. The colour white emphasises physical shapes and plays upon shape, in particular revealing breathing to the onlooker’s gaze; blue on the other hand distinctly covers up any unevenness. Franz Lehr made his mark on the scenography with characteristic costumes and an idiosyncratic set.

Figures 9 and 10: Scenes from Brief an die Schauspieler by Valère Novarina, directed by Philip Tiedemann.

After the curtain opens the letters on the actors’ back come together for a moment to form the word ‘play’. In the scenographic space of the theatre it is literally a question of an audio-visual ‘Hör-Spiel’,18 which in the interplay of media makes the audience read and listen in turn. An angled piece of writing paper, designed as a white sheet with blue lines to correspond to the costumes, is accordingly the central stage element of the scene. Programmatic words, beginning with ‘The Text’, are projected onto this particular white surface. There follows a laser beam onto the paper surface, piercing through this point from behind.

The point becomes a hole, the ending of a sentence, a beginning that pushes out over every sentence. Then the opening is enlarged to a mouth aperture (see figures 9 and 10). One after another several round holes are made in the paper through which can be seen mouths which the actors push through from behind to finally pronounce the word ‘text’. They do this polyphonically, voices as instruments, thus supporting the undertaking to re- encode the writing sheet into a score or the notation of a sound poem composition. With the continuing enlargement of the holes, through which heads finally emerge, the writing sheet expands more and more to the scenography. The paper of course is ripped, the actors crawl through and take their seats on a transformed performance text scaffold. There they hang like musical notes on a score, forming together at times a ‘body’ and group into ever changing audio-visual images (see figures 9 and 10).

What Novarina means by “pneumatic actor” (1993: 95) may thus be sensually experienced. Here the body is clearly used as a resonance body, as an instrument. Audible breathing sounds form initial sounds of varying intensity. The physical action of expressing is varied, at times immensely increased, when words are eruptively expelled from the body, making it shake. In evident correspondence to variations on acoustic arts the spoken material, in Tiedemann’s staging, is deformed and deconstructed, transferred into sound associated forms composed as a rhythmical flow of language in vocal polyphony.

One singled-out scene serves as an example of the kind of listening attitude that is expected of the audience. In this indicative scene the scaffold becomes a climbing frame for a children’s game and an experiential area, prior to language acquisition. It becomes a “trotte bébé” (Lacan 1975: 63) in the sense of Jacques Lacan. A burly, particularly physical actor in a mainly white leotard hangs by a belt from the scaffold (see figures 11 and 12).

He tilts back and forward and makes sounds, cries, chuckles, while next to him an actress translates the pre-language utterances apparently into understandable speech. It is not difficult to perceive the scene as an acoustic re-staging of the visually oriented act which Jacques Lacan introduced as the primal scene of self-recognition and self-delusion: “the mirror as formative of the function of the I” (Lacan 1975: 61–70).

Figures 11 and 12: Scenes from Brief an die Schauspieler by Valère Novarina, directed by Philip Tiedemann.

In contrast to the merely illusionary given wholeness in the mirror, described by Lacan, in Tiedemann’s elaborated scene it is an acoustic reflection of the sound material in the form of coded speech that can be penetratingly felt in all its delusion. In the scene the smooth slickness with which the mirror stadium is able to charge up the imaginary with an illusion is missing.

Here the actor is visibly and audibly tormented, emphasising this effort in sound, physiognomy and gesture by punishing himself not only with his hands but also with his tongue, smacking himself therewith. “Of all the animals we are the only ones who have this hole”, the translator says finally, enabling the theatre-goer to listen in a deciphering manner. Paradoxically it becomes evident in this scene – wherein single utterances are translated into a generalised, codified spoken language – that Novarina is attempting to restore words to tones and body sounds. Here it is insistently sensualised that words do not fall from the heavens, they are expressed physically. These tones sensually generate sense: signifiance. They may be perceived in the form of signs, symptoms or sound poetry, but in no case do they translate into a meaningful language of words. The translation is shaped by the discourse in between. Let us at this juncture repeat and recall further reflections of Roland Barthes regarding the third manner of listening, following the psychoanalytical turn: significance, which in this sense unfolds in the inter-subjective space, requires an “attention to the in- between of body and discourse” (1990: 259). Accordingly, Novarina’s play also displays an interwoven meta-theoretical text level.

Philosopher Valère Novarina provides a meta-theoretical, self-reflecting level that is connected with the communication medium of writing, the medium of inscribing regulations, of theory par excellence in addition to the sound poetry level of the performance, in which the body shows what it does. If the theatre-goer at the beginning of the episodic sequence is confronted with writing, which in Tiedemann’s staging of Novarina’s Letter to the Actors is the first thing to appear on stage, it would seem that the theory, theoria,19 has been there before the piece. The etymological relationship between theory and theatre seems to be implied here. In Novarina’s work the theoria, subject since Plato to the primacy of the optical, experiences an acoustic turn: here, the theatre stage is reconverted to a listening stage.

Conclusion

An acoustic turn, implemented in various ways, is to be noted in all forms of theatre. Based on altered acoustic and musical practices a compositional practice for dance, music and theatre forms becomes seminal in equal measure. This practice no longer offers staging which are faithful to the original text or a traditional dramaturgical structuring of the plot. Rather, through repetition strategies, intensities are experienced which are accessible due to a physical knowledge of the world and a new way of listening.

Differences and similarities may now be summed up. In Pina Bausch’s choreography the medium of technical reproduction is used not only to remind of the new – as with Goebbels – but also to make painfully aware of the compulsion to repeat. In Goebbels on the other hand technological reproduction has the particular function of breaking through an established level of fiction. Differentiation, shifts of attention and new experiences of qualitative time, which may be released through repetition, can yet be found in all the examples of dance, music and spoken theatre cited here. Repetition is also structural in all these examples; it is used contextually and is recognisable in its double function.

If repetition within the framework of conventional structures serves to constitute identity through citations, repetition which may be iterated in the sense of Jacques Derrida is also associated with otherness (see Derrida 1988: 291–314) in Heiner Goebbels’ staging concept the ongoing new creation of contexts becomes particularly manifest. When in Philip Tiedemann’s staging of Novarina’s Letter to the Actors the sounds are translated into conventional speaking language, another aspect becomes audible. The translation can be understood because it cites coded spoken language and draws upon discourse; at the same time the production of sounds refers to the body, the physical. Two different aspects of performing are experienced. In order to perform on stage representative language which relates to the world, the performance consists of pneumatic sound sequences in the form of acoustic and physical events in the world, appearing no longer symbolic but rather symptomatic. All the theatre pieces cited here were developed out of an altered listening attitude to the world; they all stimulate a new kind of listening as a way to experience and understand anew the physical, the psyche and life, existence and the world.

(Translation: Colin Moore)

References

Balázs, Béla (1968) Ausgewählte Artikel und Studien, Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó.

Barthes, Roland (1966–73) OEuvres complètes, Tome 2, Paris: Seuil.

—— (1990) Der entgegenkommende und der stumpfe Sinn, Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Bergson, Henri (1994) Zeit und Freiheit, Hamburg: Europäische Verlagsanstalt.

Burroughs, William (1986) Electronic Revolution/Elektronische Revolution, Bonn: Expanded Media.

Cage, John (1987) Silence, Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

De Certeau, Michel (1988) Kunst des Handelns, Berlin: Merve.

Deleuze, Gilles (1989) Das Bewegungs-Bild, Kino 1, Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

—— (1991) Das Zeit-Bild, Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Derrida, J. (1998) Randgänge der Philosophie, Wien: Passagen.

Furlong, William (1992) Audio Arts, Leipzig: Reclam.

Goebbels, Heiner (1989) “Prince and the Revolution”, in Albrecht Riethmüller (ed.), Revolution in der Musik: Avantgarde von 1200 bis 2000. Kassel: Bärenreiter, pp. 103–29.

Heidegger, Martin (1954) Vorträge und Aufsätze, Pfullingen: Klett-Cotta.

Kagel, Mauricio (1982) “Im Gespräch mit Lothar Prox, Abläufe, Schnittpunkte – montierte Zeit”, in Alte Oper, Frankfurt (ed.) Grenzgänge – Grenzspiele: Ein Programmbuch zu den Frankfurt Festen ’82, p. 121.

Kierkegaard, Søren (1955) Die Wiederholung, Düsseldorf und Köln: Meiner.

Lacan, Jacques (1975) Schriften I, Frankfurt/Main: Olten.

Meyer, Petra Maria (1993) Die Stimme und ihre Schrift. Die Graphophonie der Akustischen Kunst, Wien: Passagen.

—— (1998) “Als das Theater aus dem Rahmen fiel. Zu John Cage, Marcel Duchamp und Merce Cunningham”, in: Erika Fischer-Lichte, Friedemann Kreuder and Isabel Pflug (eds.) Theater seit den 60er Jahren. Grenzgänge der Neoavantgarde, Tübingen: Francke, pp. 135–95.

—— (2001) Intermedialität des Theaters. Entwurf einer Semiotik der Überraschung, Düsseldorf: Parerga.

—— (2004) “Intensität der Zeit in John Cages Textkompositionen”, in: Günther Heeg and Anno Mungen (eds.), Stillstand und Bewegung. Intermediale Studien zur Theatralität von Text, Bild und Musik, München: epodium , pp. 227–37.

—— (ed.) (2008) Acoustic Turn, München: Fink.

—— (2010) “Der audio-visuelle Raum: Pina Bauschs Choreographie, Blaubart – Beim Anhören einer Tonband-aufnahme von Béla Bartóks Oper Herzog Blaubarts Burg” in Sabiene Autsch and Sara Hornäk (eds.), Die Kunst und der Raum – Räume für die Kunst, Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 31–54.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (1967–77) Sämtliche Werke. Kritische Studienausgabe, ed. by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, München: de Gruyter.

Novarina, Valère (1989) Le théâtre des paroles, Paris: POL.

—— (1993) “Letter for the Actors”, The Drama Review, 37/2 Summer 1993, pp. 95–104.

—— (1996) The Theater of the Ears (Le Théâtre des Oreilles). Translated by Allen S. Weiss, Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Press.

Straus, Erwin (1956) Vom Sinn der Sinne, Göttingen: Springer.

Valéry, Paul (1991) “Poésie Pure (Notizen für einen Vortrag)” in Paul Valéry, Werke, Bd. 5. Zur Theorie der Dichtkunst und vermischte Gedanken, Frankfurt/Main: Insel Verlag, pp. 65–74.

—— (1993) Cahiers 6, translated by Bernhardt Böschenstein, Hartmut Köhler and Jürgen Schmidt- Radefeldt, Frankfurt/Main: Fischer.

Note

1. Cf. in detail: Meyer 1998.

2. The Latin word tacet, meaning silence, in music indicates that in an instrumental piece or folk music the voices in the movement or for the rest of the piece pause or are silent.

3. Cf. in detail regarding the cooperation between Cage and Cunningham: Meyer 2001: 183–252.

4. Cf. Luigi Russolo’s The Art of Noise/L’arte dei Rumori (1913) and his noise-generating devices called Intonarumori.

5. Roland Barthes differentiates between three forms of listening: (1) listening to signs or evidence (2) a decoding listening and (3) a listening which would not be thinkable without a psychoanalytical discovery of the unconscious and which is geared towards ‘signifiance’. Cf. Roland Barthes, ‘Zuhören/Listening’, in Barthes 1990: 249–63. In my thesis I follow partly Roland Barthes and expand his theories however with recourse to other philosophers.

6. Cf. also in detail regarding Nietzsche’s “Philosophy of Hearing”: Meyer 1993: 53–117.

7. “Qu’est-ce que la signifiance? C’est le sens en ce qu’il est produit sensuellement” (Barthes 1966–73: 1526).

8. Cf. here in detail: Meyer 2001.

9. Cf. Meyer 2008. The symposion of the same name, at the Muthesius Academy of Design and Fine Arts in Kiel, held in 2006, was the basis for this publication.

10. Cf. in detail with regard to this choreography paying special attention to the concept of space: Meyer 2010: 31–54.

11. Cf. Béla Balázs, Herzog Blaubarts Burg. Anmerkungen zum Text/Captain Bluebeard’s Castle. Comments on the Text, in Balázs 1968: 34–7.

12. The relationship not only changes between the stagings but parts are performed by different dancers also within the staging: for example, by Beatrice Libonati and Malies Alt or Meryl Tankard.

13. In the 1950s the ‘Cut-Up’ method was propagated by the painter Brion Gysin and the writer William S. Burroughs. In doing so, the film montage technique was transferred to the process of writing for the first time. Tape recording compositions in relation to this process as well as filmic games – such as the non-camera film – followed in the 1960s. See also: Burroughs 1986.

14. Character concepts have also changed under the new medial conditions of theatre arts. In this context one increasingly assumes dynamic concepts, which set themselves apart from a longdominant tradition via a change in terminology of figuration and transfiguration.

15. A detailed analysis of Heiner Goebbels’ composition The Repetition has been published elsewhere: cf. Meyer 2001: 267–324.

16. This and all other citations from the performance text The Repetition are taken from the manuscript kindly provided by Heiner Goebbels.

17. Original performance under the direction of Philip Tiedemann, 4 March 2006 at the Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus.

18. The German word for radio play means, translated literally, ‘hear-play’ or ‘hearing-play’.

19. Cf. Heidegger 1954. Heidegger makes clear that Theatre is “the view, the look in which something is shown” and that “to have seen this look is knowledge” (Heidegger 1954: 48).