Chapter 6

… To Gather Together What Exists in a Dispersed State …1

Jörg Laue

“Als Mr. Cage etwa ein Jahr alt war, ließ sich sein Vater – ein, wie wir wissen, veritabler Erfinder – die Entwicklung eines der ersten U-Boote patentieren. Gerade dessen genial einfaches und in mehreren Tiefseeversuchen erprobtes Ortungssystem aus aufsteigenden Luftbläschen aber verhinderte eine Serienfertigung wegen erwiesener militärischer Untauglichkeit. Das Patent des behördlich so bezeichneten Cage’schen Faraday’schen Unterwasserkäfigs geriet bald in Vergessenheit. Und erst als der Zufall es wollte, daß Mr. Cage sich Jahrzehnte später an eben jenem Tag, als er die New Yorker Premiere des Zeichentrickfilms Yellow Submarine gesehen hatte, den Nachlaß seines Vaters hervor nahm, tauchte es wieder auf. Sogleich entschloß er sich, den Beatles die pazifistische Verwirklichung des väterlichen Patents zu gegebener Zeit mit einer kleinen Komposition zu danken.”2

Preliminary remark

Before I start I would like to make a little preliminary remark reflecting on my Exeter experiences four weeks ago:

I had already progressed a good deal in my preparation for this Hildesheim session when, in the course of the Exeter workshop sessions, I learnt that devising theatre is a (more or less) precisely sketched term, which describes a certain theatre-practice or conception of theatre, whereas in German we speak of postdramatisches Theater (and not only since Hans-Thies Lehmann, as he himself admits, see Lehmann 2008). To me it is interesting that something is expressed by a verb in English, while in German it is expressed by an adjective, which indicates a kind of temporal shift between the genres, a progression so to say. Already this displacement, with all its implications, seems, to me, to be worth a keynote itself.

I couldn’t find that specific meaning of devising in any dictionary, which not only resulted in a bit of a naïve definition, but maybe even in a failing of the use of the term.

In our final discussion in Exeter we’d been talking for a while about how Composed Theatre could be defined in regard to its conditions and processes. And Matthias, if I remember and understood it right, made an important and efficient distinction between an ontological definition-approach on the one hand, and a practical and process-orientated definition on the other hand, which seem to be incompatible.3 (Maybe this distinction is even one between verb and adjective).

And me – meanwhile I had learnt about the meaning of the term devising in a theatre- context and at the same time had a phrase – or rather a definition of Adorno’s Ästhetische Theorie in mind: Definitionen sind rationale Tabus (Adorno 1973: 24). Definitions are rational taboos, I thought, shouldn’t we instead go on devising this term in a process-related sense rather than finding a definition, which per definitionem has got a final, a definitive, that is, an excluding and limited meaning. But this, might be, was again just a failing, a displacement of the term from its theatre-context into the context of philosophical thought in terms of art.

But anyway, in case I used the term devising in a naïve manner, but surely in an unknowing way, afterwards this seemed to me an efficient failure, thus I decided not to change anything in the already prepared parts of my workshop-session concerning that term – not least because I’m very much interested in failures, incidences and coincidences in my work, which I mostly consider to be much more productive than a precisely defined knowledge. “Know how to forget knowledge, set fire to the library of poetics”, as Derrida says in Qu’est- ce la poesie?, “gewußt wie man das Wissen vergißt, die Bibliothek der Poetiken angezünde” (Derrida 1990).

Lecture performance

In one of his conversations with Daniel Charles John Cage said: “We must construct, that is, gather together what exists in a dispersed state. As soon as we give it a try, we realize that everything already goes together. Things were gathered together before us; all we have done is to separate them. Our task, henceforth, is to reunite them” (Cage 1981: 215).

Ich hoffe in diesem Performance-Vortrag zeigen zu können, daß mit diesem kurzen Zitat bereits eine Menge gesagt ist.

Within this lecture performance I hope to demonstrate that a great deal is already expressed by this brief quotation.

As Andrzej Wirth, who was my professor at university, was preparing a speech that he had to give on the occasion of getting an award for his life’s work earlier in 2008, he asked me for a brief text that should explain the influence of the American avant-garde theatre on my work.

I sent the following Drei kurze Absätze für Andrzej to him:

Als wesentlich einem musikalisch aufzufassenden Zeitvergehen verpflichtete Performances profitieren meine Projekte unter anderem maßgeblich von der Bezugnahme auf zwei kompositorische Konzepte, die auf den ersten Blick weit auseinanderliegen mögen: einerseits das polyphone Denken Johann Sebastian Bachs, wie es sich in der Verwendung von obligaten Stimmen ausdrückt; andererseits das radikal-demokratische Materialdenken John Cages, besonders wie es sich in seinen späten Kompositionen in der Verwendung von flexiblen Zeitklammern zeigt.

Dabei widerspricht die organisatorische Strenge Bachscher Polyphonie nicht etwa dem hohen Maß an Entscheidungsfreiheit und -verantwortung, welches der Umgang mit Cages flexiblen Zeitklammern erfordert. Sondern in Gegenteil findet in den Performances, die ich mit der LOSE COMBO realisiere, beides als Präzision des Zufälligen und Unvorhersehbaren autonomer und gleichberechtigter Performance- Stimmen zueinander. Bei dem in meinen Arbeiten realisierten Konzept performativer Polyphonie ergänzen und bedingen Unvermeidlichkeit und Flexibilität einander.

Die Impulse, die von Cage – und eben nicht nur von seinem kunstphilosophischen Denken, sondern ebensosehr von seinen Kompositionen – ausgingen, kommen meines Erachtens in ihrer Tragweite bis heute – zumindest jenseits der (engen) Musikwelt – noch nicht annähernd zur Geltung (was selbst bei Bach kaum anders ist). Implizit und explizit versuche ich diese Impulse in meiner Arbeit aufzugreifen und fortzusetzen.

In preparation for this workshop I asked Andrzej Wirth for a recording of a roughly translated version of that brief text, as follows:

The performance-pieces, I realise with LOSE COMBO, are obliged to a passing of time, which is essentially musical. They benefit from the reference to two compositional concepts, which – at first glance – may seem to be far apart: on the one hand the polyphonic thinking of Johann Sebastian Bach, as you will find it in the usage of obligate parts; on the other hand John Cage’s concept of a radically democratic use of material, especially in the way it is realised in his latest pieces applying flexible time-brackets.

Yet there is no contradiction between the strictness of organization in Bach’s polyphony and the great extent of discretion and responsibility, as it is required by the use of flexible time-brackets. Quite the opposite: both concepts come together within the performances-pieces I do: they are merged as a precision of the accidental and unforeseeable of autonomous and equal performance-parts. In accomplishing the concept of what I call performative polyphony, unavoidability and flexibility complete and require one another.

From my point of view the enormous impulses, which were initiated by Cage – not only his philosophical thought in terms of the arts, but also his compositions – aren’t yet recognised for its outstanding impact, especially beyond the (narrow) scope of contemporary music. (By the way, this is more or less the same with Bach.) What I’m trying to do in my work, implicitly as well as explicitly, is to pick up and carry on with those impulses.

Bevor ich fortfahre, möchte ich mich dafür entschuldigen, daß ich auch weiterhin die ganze Zeit ablesen werde. Das hat vor allem mit der gewählten Workshop-Form zu tun.

Before I go on I would like to apologise for reading all the time, even further on.

This mainly has got to do with the chosen workshop-form.

Ich habe eine ganze Zeit überlegt, wie ich diese Workshop-Session entwerfen könnte, welche Form sie mit Rücksicht auf meine künstlerische Arbeit haben könnte, ob ich einfach von der Arbeit berichten, oder sie besser demonstrieren sollte?

It took me some time to think about in what way I could devise this workshop- session, what form it may have, in regard to my artistic work, whether I should just talk about the work, or superiorly demonstrate it?

Aber ich habe dann entschieden, beides zu tun – das eine und das andere, das eine, indem ich das andere tue, das andere, indem ich das eine tue, und zwar in Form eines Performance-Vortrags.

But I decided then to do both – the one and the other, the one while I’m doing the other, the other while I’m doing the one, that is, in form of a lecture-performance,

eines Performance-Vortrags weitgehend über Prozesse des Entwerfens eines Performance-Vortrags, mit Rücksicht auf das, was Processes of Devising Composed Theatre heißen könnte,

a lecture-performance mainly on processes of devising a lecture-performance, taking into consideration what Processes of Devising Composed Theatre may mean, and that is, in two languages, at least at first.

und zwar in zwei Sprachen, zunächst zumindest.

In two languages – although I was informed right from the beginning that the working language at both workshop places – Exeter as well as Hildesheim – would be English. It certainly – more or less – would be possible for me to explain something in English, but not to demonstrate the process of devising a lecture-performance on Processes of Devising Composed Theatre, because devising a performance to me always has got to do with – transformation. In this case: translation.

Lecture performance, Composed Theatre, performance – with regards to its devising I can’t see a difference, in principal. One of the main things I’m doing in my work is different kinds of transformations of material. Later on I will give an example of a transformation process concerning one of my performance-pieces, which at the same time will give you an example of what I call performative polyphony.

But now I have to go back right to the beginning.

Aber jetzt muß ich noch einmal zum Anfang zurückkehren.

Mostly for devising a project there is a more or less coincidentally chosen (that may sound like a contradiction, I know) starting point, which generally refers to a certain topic or a wider topical context. Or sometimes there is a formal or thematic request, a given task, as for this event. I am thankful for such situations – because this prevents me from having to make an initial decision, thus the beginning is always a haunting thing. And, by the way, everything in a way remains a beginning all the time. But besides, and at the same time, there are also leaps, leaps that are leaping the permanently beginning.

In genau diesem Moment des Schreibens über Anfang und Sprung hat solch ein leap stattgehabt.

At that particular moment of writing about beginning and leap such a leap has taken place.

An essential part of the work is giving its persistent beginnings a quality of a continuous leaping, which becomes a kind of flow, a decelerating movement, which makes one forget beginnings as well as leaps.

The fact that the topic “Processes of Devising Composed Theatre” is already set at the beginning – or to be more precise, even before the beginning, as a starting point that sets a task – is a good thing, because it is not more than four words to think and talk about. It is not more than four words that are sufficient to establish even more ways to devise a lecture- performance. Generally this is my approach: taking the beginning as a given occasion, taking it seriously, and then, let’s see where it is drifting and what it is touching upon in the working process.

From its very beginning the whole process is guided by coincidental beginnings/leaps that will lead from one detour to another.

And as you can clearly see, I got on such a detour right from the start. Taking the beginning seriously may also mean simply missing it. Quoting John Cage, I neglected to talk about those four words, explicitly.

Somehow, even to be asked is a way of setting a task. In the case of the quoted Drei kurze Absätze für Andrzej the starting point, on the one hand, was just to be asked; and on the other hand, there was a theme: influences of the American avant-garde theatre. As you have heard, I didn’t know to say that much about it. Being asked to relate my performance-work to theatre, I preferred to write about composers. At least for that reason it seemed to me to be a good beginning for this ongoing lecture-performance, which has become a demonstration on gathering together what exists in a dispersed state.

Wie Sie sehen können, bin ich noch einmal am Anfang, mit einer kleinen Verschiebung allerdings, einer Transformation sozusagen, das explizite Thema dieses Performance-Vortrags betreffend.

As you can see, I’m back at the beginning again, though, with a little displacement, a transformation, so to speak, concerning the explicit subject of this lecture- performance.

Displacement, in its various meanings, is another important subject concerning the working processes of performative polyphony. But, while demonstrating, I have to postpone talking about it, because I owe you at least one more reason for having chosen those Drei kurze Absätze für Andrzej as a– displaced – beginning. It’s not just because of its thematic impact, but also because those paragraphs are an obvious example of something that exists in a dispersed state. That brief text was definitely never meant to be a part of a performance or a lecture-performance or a speech that I would do. Using disseminated material, practising displacements and replacements has got a lot to do with gathering together what exists in a dispersed state. As soon as we give it a try, we realise that already everything goes together. That is, right from the beginning, from one displacement to the next.

A long time before I began to write down this lecture-performance it seemed very obvious to me to begin by quoting another lecture-performance – at least to give a short introduction into my work. For several reasons – and I already mentioned a few – I had to postpone that former beginning, instead I’m starting to introduce it right now.

Last year I went to South Africa for a six-month residency. In Cape Town I was invited to present my work in an already imposed, formal structure called 20:20 at the Western Cape section of the Visual Arts Network of South Africa. 20:20 stands for a strictly defined limitation: twenty seconds for twenty images. I did exactly, as follows, except for one word:

For this presentation I wrote down a brief text, built out of 20 sentences, out of exactly 20 words each.

Maybe it’s impossible to count and to listen to them simultaneously, but you need not, I promise, I did count.

First of all I have to apologise for reading, and for my deficient English too (this was sentence number three).

There is an order of the sentences and of the images as well, but there is no calculated relation in between.

I decided to present 20 images, each ten seconds, twice, while I was reading and presenting 20 sound-pieces, just once.

And I decided not to give any further information on the images and sounds, because there weren’t enough words left.

In 1994 I founded the collective LOSE COMBO that does live-art-projects that combine the genres of performance, concert and installation.

Working simultaneously with video, sound, texts and site-specific installations, the projects are often based on selected historical or literary material.

Informed by John Cage’s concept of chance music dealing with flexible time-brackets, the material is developed into complex polyphonic compositions.

Organised in a kind of performance-score, each image, live and recorded sound or light-movement becomes a ‘voice’ of the composition.

With regards to a specific experience of a decelerated passing of time each material gets its own space of time.

In 2004 I began a project-series called Ghost Stories of Media that conjures abstruse aspects of selected media or medial phenomena.

Part one, LOSE COMBO’s BLOOMSDAY, is related to James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, and focuses on questions of telegraphy and biometrics.

Part two, HERTZ’ FREQUENZEN, is dedicated to the accidental discovery of electromagnetic radio waves in the late 19th century.

Part three, FARADAY’S CAGE, deals with the phenomenon of magnetism, which is the starting point of history of media itself.

Part four, BRAUN light, focuses on the hardly mentioned disappearance of the picture tube and the loss of its light.

Last year I started a new project-series called time-labyrinths that investigates the complex non-linear structure of the perception of time.

The first part, HYDRA’S TRACES, is a concert and performance-installation in two parts that lasts three hours during dusk.

Its first half includes a brief comment on the performance-structure and a concert of Morton Feldman’s extended trio-piece Crippled Symmetry.

Its second half deals with different aspects of Hydra – not just the mythological monster, but also astronomical and biological aspects.

That was 6 minutes and 40 seconds –a precisely framed space of time. To speak in musical terms: a fixed time-bracket within lots of (more or less) fixed time-brackets, sentences as well as images, which can even be described as sequential measures or visual bars. The images as well as the layered sounds, as technically organised material, are to be fixed at a given time, but the placement of the sentences remains flexible, in this case until its performance.

I’m not sure whether this example is suitable to give any impression of what a decelerated passing of time may be. Maybe it is too short to mark the difference between that kind of experience and a simple boredom, which emerges from the everyday passing of time.

In other words, evoking a shift/change resulting in a decelerated experience of time sometimes needs some more time.

But furthermore, and first of all, that specific experience is the result of a compositional practice, which has got to do a lot with a certain usage of time-brackets – flexible as well as fixed time-brackets, which are to be handled in as flexible a manner as the working process will ever allow.

In the course of this final practice the different performance-materials, which were developed in broadly separate work steps (texts and video-sequences as well as multichannel sound-installations or instrumental compositions), have to be layered by taking care of particular time-brackets, durations and extensions, but not with regards to any external references, except a– usually ascertained – space of time, which becomes the decelerated one.

So as not to demonstrate the first after the second work step, I will postpone explaining more about this compositional practice concerning the organisation of different performance- materials, but – as already announced – go on giving an example for a transformation process of a single performance-material.

The result of this transformation process is a piece for piano, flute and percussion I did for the performance BRAUN light. It is called rgb. As I mentioned before, the thematic starting point of this performance was the rarely mentioned disappearance of the picture tube and the loss of its specific light – its light beyond the function of generating images – that is images that normally make one forget the quality of the picture tube light, instantly. In a sense the performance is about what Heiner Müller calls: “Das Verlöschen der Welt in den Bildern – The dissolution of the world into images” (Müller 1971: 14).

At the end of the nineteenth century, the German physician Ferdinand Braun succeeds in the groundbreaking development of the so-called cathode ray tube, which enables the magnetic control of light-points, out of which images are to be generated.

Figure 1: New York Times article on the first electronic television.

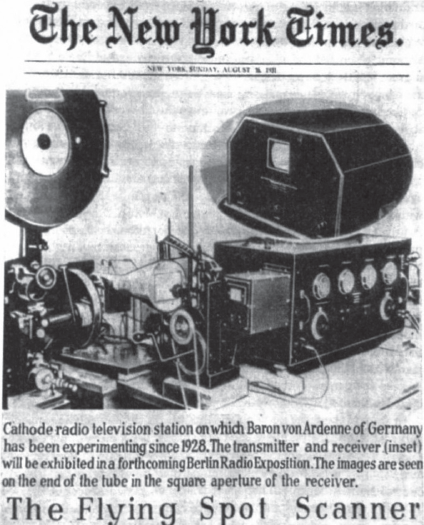

In the early thirties of the twentieth century, Baron Manfred von Ardenne, a German natural scientist and engineer, presents the first electronic television ever at the Berlin Radio Exposition –a sensation, worldwide.

Figure 2: Ardenne’s cathode radio television.

Its screen is a square, about 5 by 5cm, which is equal to 10.000 pixels. During that early moment the Ardenneian, so-called cathode radio television allowed for the transmission of movie-pictures only.

Figure 3: First video-still shot by Ardenne.

This is supposed to be the first video-still in the history of electronic television –a photo shot taken by Ardenne himself during his first transmission experiments. To be more precise it is the adapted scan of a reproduction of that photograph. This is apparent not only because the shape of the reproduction isn’t a square anymore, but because the process of transformations must have begun even before I found it in a book. (By the way, I didn’t find out anything about the name of the movie, nor about the actresses’ names.)

This first video-still ever is the graphical basis for the rgb-piece for the BRAUN light performance. Skipping a few work steps, I took the scanned video-still –a coloured scan of a brown-coloured reproduction of a black and white photograph of Ardenne’s black and white TV transmission – then I took the image, with its millions of colours, and reduced its huge amount of pixels to just 10.000 by using the rgb-colour-mode for digital image editing, which – as you all know – is, at the same time, (the name of) a common colour-TV-mode.

Figure 4: Video-still in adapted resolution and in rgb-colour-mode.

In other words, I adapted the resolution of the first electronic TV transmission to the supposedly first video-still, which is a document of this transmission. What you can see here is the result of that transformation step: about 10.000 computer-rgb-pixels – red, green, blue, its mixed colours yellow, magenta, cyan as well as black and white. For some reasons (I’d like to skip) it is indeed less than 10.000 pixels, but anyway it is a similar resolution to the one Ardenne’s screen worked with. Maybe you can still identify the image?

Figure 5. Figures 5–12 show further steps in the adaptation/ transformation process as described in the text.

In a next work step I simply isolated the three basic colours of the pixel-image: red, green and blue – three colours for three musicians, which at the same time are the three image- generating colours of a colour TV picture tube.

Figure 6. In the following work steps I isolated each colour and assigned it to one of the instruments: red for the piano

Figure 7. green for the percussion

Figure 8. and blue for the flutes. These are the blue pixels of the transformed video-still. For a moment I will just go on with the part of the flute. But it’s the same transformation procedure according to the piano and the percussion part.

Figure 9. These are the flute-pixels again. I simply changed their blue colour into grey, while the shapes of the pixels stay the same. In its approximate centres I placed the scaled-down identical pixels in their original colour. Or the other way around: I scaled-up the empty spaces in between the blue pixels.

Figure 10. In a next work step I divided the coloured-within-grey-pixels-images into 5 by 5, which is equal to 25 segments of the same size each. Each segment retains the proportions of the basic pixel image as well as the video-still. Every single segment becomes the graphical basis for one sheet of an instrumental part – in this case, of the flute. The 25 sheets are numbered sequentially, as follows: first row: one to five, second row: six to ten, third row: eleven to fifteen, and so on.

Figure 11. This is the left segment of the top row. The distances between the grey pixels keep the proportions of the former basic colour pixels, as well as the proportion between the scaled- down blue pixels and the grey pixels – where they are centred remains the same all the time.

Figure 12. This is the first sheet of the flute part, using the left segment of the top row.

Every single sheet has got 4 staves. In the case of the flute-part four staves at once contain the whole range of all flutes – piccolo to bass flute. (In the case of the piano-part four staves at once contain the whole range of the piano; in the case of the percussion-part two staves at once contain the whole range of the glockenspiel. It is a glockenspiel for the simple reason that the percussion part is orientated by the range of the percussion-instrument, which is used in Morton Feldman’s composition Why Patterns? – the piece that we played in the second part of the BRAUN light performance. However, the percussion player is free to use different percussion instruments, and not only the glockenspiel. The piano player is also free to play inside-piano, and not only to use the keyboard; similarly the flute player is free to create sounds by using any articulation-techniques that the several flutes may provide.)

There is an exact graphical relation between the sizes of the staves and the ranges of the instruments, that is to say the spaces between the lines in a stave as well as between the ledger lines vary from one instrument to another. In other words, the vertical dimensions of the graphical segments are exactly covered by the ranges of the instruments.

Every single segment lasts 80 seconds. From this, follows the whole sequence of 25 segments, which are to be played conjoined one after another, lasting exactly 33 minutes and 20 seconds. That is a precisely framed space of time, a fixed time-bracket within 25 fixed time-brackets, which can even be described as visual bars or a kind of raw time- pixels. Within those 25 fixed time-brackets there is a big amount of flexibility because of the temporal arrangement of each instrumental part.

Each coloured pixel marks the pitch of a single sound event. Within a time-bracket of 80 seconds every grey pixel marks a time-bracket wherein such a single sound event may take place. That means at first that the duration, as well as the exact moment of every single sound event, remains basically flexible within a marked space of time.

At the same time there are several possibilities as to how to interpret the four staves, which result in an 80-second time-bracket:

Each musician is free to decide whether he would like to play:

| • | one stave after another, which means every stave lasts 20 seconds; or |

| • | two staves at the same time twice, which means 40 seconds two times; or |

| • | four staves at the same time, which means 80 seconds at once; or its mixed versions |

| • | two single staves after another and two staves at once (20 + 20 + 40 seconds); or the other way around |

| • | two staves at once and two single staves one after another (40 + 20 + 20 seconds); or |

| • | one single stave at first, two staves at once and another single stave at the end (20 + 40 + 20 seconds). |

These six different possibilities imply 216 possible combinations of the three instrumental parts for just one 80-second time-bracket. That gives 5,400 possible combinations for the 25 segments of the whole rgb-piece.

Depending on the musician’s basic decision as to how a single segment is to be played, the durations of the grey-pixel-time-brackets vary. In other words, they become flexible, but they nevertheless keep a precise marking of the maximum duration of a single sound event.

Reading the top stave of the first sheet of the flute-part as a single one that is to be played within 20 seconds means that the sound event marked above the top stave would take place approximately in between second 2.5 and second 4.5. That implies a maximum duration of about 2 seconds. In this way of reading, this sound event would definitely be the first sound of the flute.

Reading both upper staves simultaneously, which is to be played within 40 seconds, the same sound event would take place approximately in between second 5 and second 9; it could be the first sound of the flute to be heard, but it doesn’t need to be because the first sound event marked in the second stave could even take place before.

Reading the four staves simultaneously within 80 seconds, the sound event marked above the top stave, which would now need to be realised in between second 10 and second 18, definitely wouldn’t be the first sound of the flute anymore, because the first pixel assigned to the lowest stave in this case would take place in between second 0 and second 4, approximately.

There is a chronology of the segments, and there are kinds of junctions, which require decisions every 80 seconds (by the way, there are even a few possibilities to re-decide within an 80-second time-bracket), while the chronology of the sound events marked by the pixels may change, or become indeterminate, as well as the moments of its realisations and its durations.

Because the pitches are only fixed relating to four staves simultaneously (in the case of the flute and the piano), respectively relating to two staves simultaneously (in the case of the glockenspiel), a lot of decisions concerning the temporal arrangement necessarily also entail decisions concerning the pitches. Apart from the fact that the coloured pixels may also mark non-tempered pitches this is the main reason to abandon any clefs.

But because I want to continue talking a little about the layering of separately developed performance-materials, and its particular time-brackets, I won’t go on talking about pitches, clusters, noises, timbres etc. anymore. I will also omit further tricky – and occasionally paradoxical – details that have to be considered concerning the arrangements of the time- brackets.

The rgb-piece is one separately developed sonic performance-material, which becomes one layer of the BRAUN light performance. With regards to its 33:20 time-bracket it is a completely autonomous performance-‘voice’ in the sense of performative polyphony. As well as the trio, which is one layer of the performance, its parts are layers of the piece as well as of the whole performance. That is, the three parts of the rgb-piece are to be realised independently from one another. This means that each part should just be played in relation to its particular time-brackets, but not with regards to the pixels of the other parts or its common (transformed) starting point. Besides an arrangement concerning the basic characteristic style of the trio as well as of the whole performance, which is almost given by its time-passing calmness, there are no further directions. That is to say that for the musicians being aware of the piece, as well as of the performance, means not listening to, or caring about what the others are doing. To them it is just important that there are pixel- precise time-bracket-structures, which, at the same time, leave room for a huge range of flexibility. These structures require a high degree of precision because of their principally unlimited possibilities of realisation. While the decision as to when the rgb-piece is to be played in the course of the performance is fixed at a given time; in the case of the musicians, their decisions remain open until their actual realisation.

Besides Heiner Müller’s text Bildbeschreibung (published as Explosion of a Memory in English), which we divided into two parts that are to be read by two performers, there is also a third sonic material: a six-channel-audiotape, which lasts 57 minutes. The duration of the tape (which I consider to be some kind of devised silence – but that would be another issue …) marks the fixed time-bracket of the first part of the BRAUN light performance. As well as the three sonic performance-materials – trio, text, audiotape – there are also layers of the performance: the tape itself is layered by hundreds of sounds, which mainly result from lots of electro-acoustic transformation processes of just two samples, both lasting a few minutes.

It was only by chance that I learnt about receiving funding for the BRAUN light project while I was in the middle of nowhere in Argentina, where I held a workshop on Strategien des Nebeneinanders, Strategies of Juxtaposing – what to me means a mode of layering and placement in terms of organisation of material. For that incidental reason, and with regards to the thematic starting point of the project, I brought two Argentinean everyday-life sound- samples with me, on which, coincidentally, TV sounds are to be heard in the background. We must construct, that is, gather together what exists in a dispersed state. Out of these recordings I generated hundreds of sounds for the BRAUN light audiotape. That is, I transformed a few sounds out of those two samples, and afterwards transformed lots of sounds out of the transformed sounds … and out of those … and so on … That transformation process resulted in a huge amount of sounds of derivates of derivates of sounds, which singularly last about 3–7 minutes. Thereby a single sound – or often a series of almost similar sounds –is usually not developed with any other sounds, which already came up, in mind, even less the resulting audiotape. I just care about the particular sound I’m actually working on, what it means, just listening, changing a little bit, listening again. Producing sounds for an audiotape and organising the tape out of the sounds – that is mainly placing, layering, editing and mixing – are totally separate work steps.

By the way, this is the same with the visual performance-material, especially the videotapes. But I won’t talk about it anymore in the course of this prepared lecture-performance because too much time has passed in the meantime.

(I’m sorry that the tendency of this lecture-performance on devising a lecture-performance on gathering together what exists in a dispersed state has increasingly changed to a lecture on a specific performance. This is not because I’m reading all the time – musicians normally read too, and performers (at least in LOSE COMBO performances) read aloud as well. So I guess this change (or displacement) is mainly to do with the usually intended purpose of a lecture, which is to inform. Lectures are meant to aim at a comprehensible result, that is to say they never start without an aim, a target so to speak. In a way the starting point of a lecture even inverts to its opposite. Thus a lecture, layered or not, goes straight along a time-line describing a horizontal movement, with information and comprehension almost always in lockstep. While a performance, which is layered because of the time-brackets of its separately developed materials that were gathered together, becomes a time-space. Within that kind of time-space there is no need for any external aim. It is just taking place. In a sense its vertical dimension prevents one from aiming at anything else, and therefore enables a decelerated passing of time).

Figures 13, 14 and 15: LOSE COMBO feat. Trio Nexus: BRAUN light, performance | concert | installation; Villa Elisabeth, Berlin 2008 Copyright david baltzer/bildbuehne.de.

More or less at the beginning I mentioned that I don’t see a difference between devising a lecture-performance and a performance, in principal. However, concerning its perceptions and experiences there might be outstanding differences.)

But I have to come back: while the development of each single performance-material normally needs a lot of time, usually a couple of weeks, the layering of the several materials, that is placing and moving and trimming, the whole assembling-process, takes place within a few days. And the result of this process is always just one out of a virtually infinite range of possibilities. The main thing is working out one supposable good possibility. It almost always feels like there isn’t enough time. But at the same time everything already goes together. For that reason I usually prefer to come to an end abruptly, at an unforeseeable moment, that is surprising in the course of the working process, even to me. Although there are just a few days, and, one might think, too little (mostly technical) rehearsals, at the end of it all a performance is devised a lot faster than I could have ever imagined.

And that is the same with a lecture-performance.

References

Adorno, Theodor W. (1973) Ästhetische Theorie, Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Cage, John and Charles, Daniel (1981) For The Birds, Boston and London: Marion Boyars.

Derrida, Jacques (1990) Was ist Dichtung?, Berlin: Brinkmann & Bose.

Hans-Thies Lehmann, Karen Jürs-Munby and Elinor Fuchs (2008) ‘Lost in Translation?’ in The Drama Review, 52:4, pp. 13–20.

Müller, Heiner (1971) “Traktor” in H. Müller, Geschichten aus der Produktion 2, Berlin: Rotbuch.

Note

1. This text is almost identical with the one of the lecture-performance I gave in the course of the workshop series on Processes of Devising Composed Theatre. While I presented this text and several videos, images and sounds simultaneously in the course of the lecture-performance, for this publication I only pasted a few images into those passages that explicitly refer to the shown visual material.

2. This brief text was part of the performance Faraday’s Cage, which I did together with LOSE COMBO feat. Kammerensemble Neue Musik at St. Elisabeth-Kirche Berlin in 2006.

3. See chapter 15: “Composed Theatre – Discussion and Debate” in this book.