Chapter 13

Composing with Raw Materials: Daniel Ott’s Music-theatre Portraits and Landscapes

Christa Brüstle

Composition is generally understood as doing something constructive, a creative activity. Composition or compositio is the “science of producing harmony by assembling and joining consonant and dissonant notes” (Walther 1732: 178)1 as Johann Gottfried Walther defined it in 1732. Composition was then seen as a science; it later became the creative act of a genius and, in the twentieth century, a method, process and construction – whereby the activity and creativity (of a composer) has always remained in the foreground. As Arnold Schönberg wrote:

After many unsuccessful attempts during a period of approximately twelve years, I laid the foundation for a new procedure in musical construction which seemed fitted to replace those structural differences provided formerly by tonal harmonies. I called this procedure Method of Composing with Twelve Tones Which are Related Only with One Another.

(Schoenberg 1941: 218)

Taking pleasure in the creative act, even physical pleasure, was stressed by Stravinsky:

All creation presupposes at its origin a sort of appetite that is brought on by the foretaste of discovery. This foretaste of the creative act accompanies the intuitive grasp of an unknown entity already possessed but not yet intelligible, an entity that will not take definite shape except by the action of a constantly vigilant technique. […] The very act of putting my work on paper, of, as we say, kneading the dough, is for me inseparable from the pleasure of creation. So far as I am concerned, I cannot separate the spiritual effort from the psychological and physical effort; they confront me on the same level and do not present a hierarchy.

(Stravinsky 1970: 65–67)2

One can imagine the craftsman right in front of us, piecing things together bit by bit and in so doing creating a complete whole. The archaic English term for this activity is ‘to perform’, which has in common with the modern word performance only that something is being constructed and completed.3

As far as the pianist and composer Daniel Ott is concerned, composition does not start with one’s own constructive activity; when composing his musical pieces and music theatre projects, what is there is much more the starting point and field of work at one and the same time. Natural surroundings and landscapes, for example, are resources the Swiss artist, who grew up in picturesque Grub in Appenzell canton, repeatedly uses as venues. Urban and industrial areas are composite locations that are rich in history and have many starting points for audible and visible events. Even transit routes or (forgotten about) non- places create their own atmospheres that one only comes across when used, for example, in the music theatre journey Südliche Autobahn (Berlin 2007) or in the music theatre piece Paulinenbrücke (Stuttgart 2009).4 But what is already there relates not only to exterior spaces, as one also finds room for manoeuvre and social relations, personal experiences and memories, an education, a job, a working environment, in short, personal circumstances of the past and present – everything is present, everything is ‘there’. The basic condition for creating art with it and from it is a mix of sensitivity, attentiveness, observing, leaving and finding.5 The first thing to ask is not ‘What can I do with the material?’ but ‘What does the material and/or the material found do with me?’ This approach reveals Ott’s link to John Cage, whose vision of music theatre he shares: “There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear” (Cage 1958: 8).

Daniel Ott’s music theatre projects are Gesamtkunstwerke in a very practical sense, as they emerge from teamwork. The composer sees the performers as co-authors whose experiences, memories and personal circumstances, whose reactions to particular places, and whose relationships to the work flow into the development of a music theatre project. Different artistic fields should also communicate ‘without any hierarchy’.

At the composer/author level, this means that ideas are not pre-sorted into categories as soon as they appear. I consider it important to be open to stimuli/ideas/research, to accept ideas “as ideas” – to investigate where they might lead is then the second or third step … only later does the question arise: “What can I implement with my skills and possibilities? Where must I depend on experts (co-authors/performers) from other areas?”

(Ott 2001: 51)

Ott attributes this working method partly to his active interest in Pina Bausch. He got to know her dance theatre projects more closely in the late 1980s while studying composition in Essen. He also quotes Hans Wüthrich, referring to the Swiss composer’s psycho-acoustic portraits, “that is, composition with another ego”.6

From her piece Kontakthof (1978) onwards, Pina Bausch’s working method explicitly involved asking questions of her ensemble in order to develop her works, questions intended to “gather material on particular themes; […] from the personal answers, which depend on the mood and cultural origin of each dancer’s personality, and which probably have different forces of expression, emerge words, sentences, gestures, poses, movements – small scenes are created” (Schulze-Reuber 2005: 73).7 In Ott’s work, too, an experimental working process gives rise to performable concepts and stages, or versions of a performance, based on the found (present) material, its context and whatever triggered the material. In other words, syntheses, montages, combinations and compressions of music, images, actions, figures now begin to develop that may, for example, be integrated into an existing landscape or staged independently. In this sense, Daniel Ott’s work is also related to Dieter Schnebel’s experimental methods, for example, Schnebel’s works Maulwerke (1968–74) or Körper-Sprache (1979–80). The core principle of both these well-known pieces is not based on prescribing a set order of action or a narrative structure; instead they begin with ‘drills’ or ‘exercises’ in which the basic elements of speech articulation or individual body movements are isolated to be tried out in sound studies or rhythmic studies. Schnebel intends that ‘complete processes’ should develop from these exercises, that is, performance versions for a particular group of performers and for a particular place. Daniel Ott also considers the openness arising from this principle to be very significant.

After all, the ‘open form’– a rather dated concern of the Avant-garde movement – is still an important precondition of my work: the unfinished, fragmentary, temporary, incomplete as an opportunity to take ideas further – the gap that enables me to interrupt a process (my own or from elsewhere) with new ideas. Working with the open form also means to me ‘work in progress’: engaging with themes/materials without having any idea of the form which may later emerge.8

(Ott 2001: 54)

This process does not create music theatre, however; music and theatre are ‘there’ from the beginning. A musician does not need to become an actor; he is one already, although most musicians who have gone through the traditional western musical education would not emphasise this. But in the context of music, the roles are particularly clear: conductor, orchestra musician, soloist, popular musician, bass, organist – a whole range of social frameworks and contexts, which could be extended, demand not only the appropriate music but also the ‘embodiment’ of particular roles to satisfy the audience’s expectations. In everyday life, we encounter the unity of music, sound and action directly, when walking or running, in traffic, when cooking and eating (the list could be extended at will). Ott presupposes the ‘permeability’ of the artistic and everyday dimensions in his music theatre projects. “The effort necessary to maintain ‘open boundaries’ within artistic fields and the exchange between them, resulting in a complete work of art, also applies beyond these fields; that music theatre ‘relates to’ – stands in a relationship to – its social and political environment – directly or indirectly” (Ott 2000: 54). Daniel Ott’s music theatre is always socially reflective art. This process includes making music together, for example with improvisation. It also implies letting the individual music of the musicians themselves – such as dance music, folk music, favourite pieces – become part of the composition of what already exists and what is being created.

skizze – 7½ bruchstücke (1992)

Five musicians with five instruments are present: bass clarinet (Uwe Moeckel), percussion (Christian Dierstein), violin (Melise Mellinger), viola (Barbara Maurer) and cello (Lucas Fels). The percussion comprises two saw blades, eleven glass bottles (to be broken), a bottle piano, a caña rociera (an instrument made from a split bamboo cane and used as a rattle), a pair of cymbals (lined with felt, completely damped), a metal rod, a felt and a wooden drumstick, a double bass bow, a metal sheet on which sand is rubbed by the feet, branches, two wooden boxes, a large glass bell jar, three ‘tuned’ wine glasses, a water container, gravel, sand and a small drum on which sand trickles. As an initial orientation, the question mentioned above is posed: What does the material and/or discovered material do with me? In addition, one might ask: What elements, aspects, questions, effects do the musicians and their instruments produce? The composer is confronted with this question and later the audience considers it in a different way. First, the musicians are virtuosi on their instruments. How did that come about? Which instruments do they play, and why? Has Barbara Maurer always played the viola? What made Christian Dierstein choose percussion? Did Melise Mellinger learn to play the violin as a child? Did Uwe Moeckel always want to play the clarinet? It is easy to imagine these questions arising during private conversation, just by the way. The answers are to be found in the piece, whereby it becomes clear that the musicians are reflecting on what has made them and is still making them what they are. Musical autobiographies or portraits? Does this mean that the piece is directly linked to the people who developed it or who contributed to its development? Would it be different with different musicians? “The musicians’ answers to my questions influence the composition process in various ways. Either through quotations or the direct inclusion of found material – or through structural ideas – an idea from outside often arouses the necessary resistance to my intentions, thereby teasing out new ideas. How directly this joint formation process leaves traces on the performance depends particularly on the willingness and possibilities of the musicians. The aspect of reproduction of a composition by other performers fades into the background: sometimes it is possible to make an adaptation for new performers. Some of my works remain unique; they can only be staged by the performers with whom they were created” (Ott 2000: 53).9

The piece skizze – 7½ bruchstücke was first performed in Witten in 1992. It comprises 7½ images in which the musicians alter their basic actions and positions on the stage. A score documents precisely what structures and topics were discussed and decided on during the formation process. So the score is documentation that also gives instructions for the performance. It contains the sounds to be played, note by note; the rhythm of actions, words and sentences to be spoken are set down precisely. The musicians are also actors; they act themselves and about themselves; their roles emerge from their profession. For example, take Christian Dierstein, a percussion specialist for new music, a perfectionist with an extraordinary sensitivity to sound. His range of instruments, described above, is not unusual in new, experimental music: it is the norm. Breaking branches rhythmically, which he does at the opening of the piece over a quiet background of music from the other players, or throwing glass bottles violently into a wooden box, are quite familiar sound events in this context. They recall pieces by Nicolaus A. Huber, for example, where similar events occur (Daniel Ott studied composition under Huber from 1985 to 1990). So the percussionist is very active; in the second image, he takes seven precisely measured steps from left to right at the back of the stage, turning on his heels each time; in addition to the aggressive bottle breaking, he throws gravel at the saws, stirs in the broken glass, and throws sand at the drum. And what does he say while doing this? “It’s simply – you get it – simply unbelievable – get it – simply not – never get rid – unbelievable – you get – it’s un- – it’s simply un- – you simply never – get rid of it”.

An echo of the softer, more reflective sound events in the following third image provides a quiet moment before all the performers start speaking again. The percussionist starts pacing feverishly again and now more details are revealed: “It’s unbelievable – you can hardly get rid of it – such a– such violence, that comes from marching – such militarism is almost always there with percussion.”10 What actually is percussion? The monologue and the reflections continue. “The way of using exotic instruments is somehow colonial – even the expression – ‘beating a drum’ – as if it’s all about beating – the rociera or caña rociera – an instrument made of bamboo – used like castanets – at the fiesta del rocio – ‘beating a drum’ – beating is the least of it – ‘drum’ – the words themselves are violent – beating a drum also means: plucking, pulling, shaking and.” As if to show possible continuations, in the next image, the fourth, the musicians are all standing in a row, looking towards the back of the stage and working with their feet. The fourth image develops into a joint step-dance with accompaniment.

The example of the percussionist shows that Ott does not simply provoke answers to his questions, but also initiates monologues. Chains of linked thoughts are expressed, associations woven in, related topics mentioned. This may recall Robert Ashley’s ‘involuntary speech’ in his Automatic Writing (1979) or the musicians murmuring as if in their sleep in Michael Hirsch’s Hirngespinste (1996). Speaking while music-making, speaking about music-making while music-making, reflecting on speaking about music-making while music-making; this also links with Mauricio Kagel’s ‘instrumental theatre’, for example Sur Scène (1959/60) or Sonant (1960/…).11

In Daniel Ott’s piece, speaking is also story-telling, recounting one’s own experiences, and not suppressing the related emotions but giving them space. The speaking and actions are not simply carried out, do not simply happen, but transport anger, grief, regret, contentment and calm. The string players also take their experiences with their instruments, their relationships to their instruments, as their starting point. Barbara Maurer first played the violin, then the viola: “well yes, it was nothing special – just an average instrument, and when it’s a gift you don’t look so closely – end of last century”. Melise Mellinger, who starts speaking with Barbara Maurer in the second image, was forced to; in the penultimate image she is finally able to articulate more clearly: “I would – I was forced to practice the violin – I got postcards showing landscapes or beautiful actors as a reward.” Lucas Fels, cellist in the Arditti Quartet since late 2005, is less personal in his report, talking (probably) about his instrument. He also first presents speech fragments, hints, in the second image (“was a bit too big –a bit sawn off – was too big”) that later come together to form a coherent statement, especially in the fifth image – after the step-dance – when all three strings players come forward and describe and praise their instruments. Now the cellist chants:

seventeen-twenty bologna, it’s the only cello made by the violin-maker florinus guidantos of bologna, made in 1720, a bit was sawn off here because the instrument was too big –a very special instrument, fantastic sound – there was woodworm in the f-holes.

Mixed with his resentment and pride in his instrument’s history is his anger at having to suppress his south Baden dialect, and the cellist lapses into his dialect now more than ever. Again a chain of associations is triggered, which leaves open the question of its origins and continuation in the piece.

A film version of skizze – 7½ bruchstücke was produced in 1993 in collaboration with Reinhard Manz, entitled 7½, and its first public viewing took place in Witten the same year. In the announcement of a television broadcast of the film in August 1993, the author gave this interpretation: “Scenes of pristine natural beauty for the opening – followed by the musicians’ world, full of neuroses, compulsive repetition and legitimation crises, each musician trapped in an imaginary cage and each sound the product of alienated work.”12 But is the ensemble really in crisis, are the musicians autistic and is the music they play really the product of alienation? This interpretation hardly seems appropriate to the highly professional formation of the ensemble recherche from Freiburg, which is playing here. But how can one interpret the players’ interactions that occur quite naturally, that in fact hold the piece together?

The percussionists’ actions dominate the beginning of the piece; the other instruments ‘accompany’ them. Sustained notes from the strings (violin and viola flageolet) and clarinet and brief rhythmic accents are the quiet background or sound shadow for the breaking of the branches. In the second image, the dynamics change; impulsive sound-gestures by the ensemble seem to heighten the breaking bottles in the box. This is followed by all the performers speaking, showing isolation but also a group dynamic – everyone has something to say. The word ‘chaos’ is mentioned – and not by chance. In the third image, a thoughtful pause takes place, which may succeed in reorganising the articulation emerging out of the silence. Yet the complex overlap of the sentences recurs, more intense in its dynamic withdrawal. Image four provides perhaps the greatest contrast: all performers standing in a row, all looking in the same direction, all performing to the same rhythm. Image five synchronises the string players’ speaking; a further rhythmic link is attempted in the sixth image, but now there is a protest. “No, that’s not quite true!” Melise Mellinger interrupts the procession of her male colleagues, who are moving in an orderly line from right to left on stage. The move away from this is gradually linked to a return to individualisation.

“The 7½ images must be staged during rehearsals”, writes Daniel Ott in his score for the piece. He requires neutral stage lighting, a “well lit stage during the whole piece”. The performers should have individual dark clothing and shoes with hard soles. He also specifies the initial positions of the chairs on stage and the precise position of the percussion. The staging is accordingly less a performance strategy than a creation strategy; the latter “creates the actuality of what it shows” (Fischer-Lichte 2004: 324).

ojota (1997 onwards)

The different versions of the ojota cycle are examples of Daniel Ott’s ‘work in progress’. Ojota uses shoes, steps, paths and traces. “I looked into different languages and cultures for synonyms for shoes or steps when searching for an overall title for the cycle. I finally discovered the word ‘ojota’ in Quechua, a pre-Columbian indigenous language still spoken in the Andean Highlands of Peru and Bolivia. There is no word in Quechua for shoe – as the word ‘shoe’ appears to be of European origin – but there is a word for (wood) sandals, namely ojota” (Ott 2001: 55).13 The starting point for the shoe pieces are elementary and personal experiences of walking. Mixing sound and movement into walking in different shoes and on different paths recreates a new basis that needs no seeking out, rather, and at most, emphasised or stage managed in the sense of “letting something current emerge” (Fischer-Lichte 2007: 22). There is also a broad cultural historical and artistic perspective in which walking has a role to play.14 We may think of Thomas Bernhard’s story Gehen from 1971, another key text for Daniel Ott. Extracts from texts become material for him, such as five pairs of shoes made of leather, wood and iron that were used in the first version of ojota in 1997, in which a drummer goes on his way. In this contribution to the collective composition Zwielicht – Hornberg. Sonnenuntergang/Sonnenaufgang (Rümlingen), the drummer Christian Dierstein walks a stretch “almost one kilometre in length with changing surfaces underfoot: forest floor, gravel, meadow, wooden boards, grit and a tarred road”. He moves “wearing different shoes (made of different material) on his feet and hands – and the mobile sounds produced this way could interact with the sound events and images that crossed the drummer’s path” (Ott 2001: 56). Structuring and shaping walking, above all giving it rhythm, belong to the essential, compositional aspect of the piece. One cannot see the drummer in this piece as a musician merely performing one of Ott’s scores, however, as Dierstein’s own additions are integrated into the piece.

The composition consisted ultimately of sound events while walking, of pauses and changes of shoes as well as of virtuoso sections ‘trodden’ into acoustically appropriate points in the piece. As he changed his shoes, Dierstein gave accounts of experiences with shoes and stretches of path that he had remembered during rehearsals, as well as recalling associations with the process of walking from various cultural journeys.

(Ott 2001: 56)

One can call Daniel Ott’s approach to his work as encyclopaedic in the widest sense. This touches very closely on the working methods of Mauricio Kagel. However, Ott’s use of material is less about pre-structuring and preparing it (with Kagel, as well as with Schnebel, a consequence of parametric thinking) and much more about linking it. The heterogeneous material is not pre-arranged, but rather composed on the basis of aspects of its effect – not only in the sense of symbioses or synergies, but also in the sense of contrasts and contradictions. Composition becomes staging, staging composition. Matthias Rebstock asked an important question in this respect when he asked the composer how he went from the “improvised building blocks, that have a lot to do with the musicians, to a finalised composition” (Ott 2000: 97). It is worth studying the answer, but only the first paragraph can be given here for reasons of space. Ott replied:

You can basically say that yes there are pieces in which everything develops from a point, and those that are based on a find to which the composer responds. You can see such finds, which were not my invention, in ojota III, and there isn’t just one such point, but different ones. I currently find it exciting to link both together. I did not invent the shoe, nor samba. They are like pins on the map – and it is the path between them I compose.

(Ott 2000: 97)

After the sound events of walking on a small stage were conveyed in ojota II (1998), and the shoe sounds combined with a mobile instrumental ensemble (musica temporale, Dresden), new personal and musical arrangements were presented in ojota III. For the premiere of ojota III at the Donaueschinger Musiktage in 1999, Ott worked with Anna Clementi (vocals), Françoise Rivalland (santur and cymbal), Chico Mello (guitar, clarinette), Simone Candotto (trombone) and Christian Dierstein (drums).15

The starting point for the composition was improvisation and the performers’ memories of shoes/steps/paths/traces from the five cultural journeys and in their five mother tongues: Italian, French, Portuguese, Friulan and German. I linked these finds with my own associations and refined them, created compositional sequences from them, and discussed them with the stage designer Sabine Hilscher and the dramaturge Matthias Rebstock. The performers became co-authors, their mother tongues music.

(Ott 2001: 57)

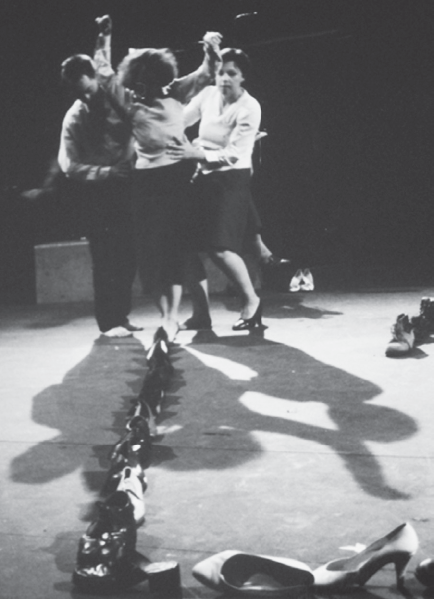

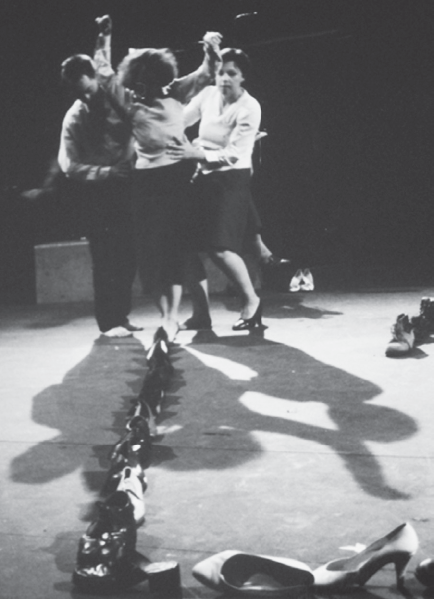

Even the structure of this version of ojota is based on three ‘sound finds’ that emerged during rehearsals: fandango, serenade and waltz.16 These also structure the dramaturgy, the density and the tempo of the sequences. There are two ‘shoe changes’ that end parts one and three and which initiate a ‘cloakroom situation’ – personal accounts from the performers that are simultaneously interpreted in the languages ‘present’. However, this rough arrangement provides no information about the wealth of aspects that are implicitly and explicitly interwoven and made into a theme in this piece about shoes. The pairs of shoes that come onto the stage one after the other at the start, from high-heeled shoes and clogs to worn-out brogues, pumps and sandals, is possibly an allegory of this arrangement. Each pair of shoes could tell a story. The stage designer Sabine Hilscher specialises in such items and naturally selected the shoes on the basis of their sound. This selection criterion was surely important in part three when some of the pairs of shoes perform solo.

You can not only tread paths in shoes, as the shoes themselves become trails on the stage, the rows of shoes giving the space a clear shape at the start. The drummer positions them in rhythmic sequences and Anna Clementi uses them as pathways, as if they were rocks in a stream, the water flowing between them.

In the south Brazilian fandango, musicians play complex rhythms using their wooden shoes and the musicians in ojota III hark back to this tradition. Continuing this tradition freely is also intended. While the first part presents group work that ends with ‘frozen’ scenes and a silent fandango, the middle section of the piece focusses on the ‘lonely balladeer’ Chico Mello with his guitar. His performance is contrasted by the musician Anna Clementi, loud and hysterically invective in a dressing gown (‘Aunt Rosina’) in the ‘long corridor of a house in Catania’, as well as by Françoise Rivalland stomping around clumsily on stilts. The trombonist later enters and exits the stage in the role of a character from a small Italian town. His small, exhilarating gestures are enough to identify him as an actor. The panorama of the shoes and their contexts thus overlap with the functions of the characters on the stage: private individuals, folk musicians, and the performers of a piece, actors, stage workers, narrators, translators and living sculptures.

Figure 1: Scene from Daniel Ott: ojota III (1999). Copyright Sabine Hilscher.

This spectrum is extended in the next project – ojota IV (2000, Theater Bielefeld) – and is directed towards the audience’s situation as well as the duration of the performance and the number of performers (seven singers, two actors and six musicians).

Together with the dramaturges Matthias Rebstock and Roland Quitt, a version emerged in which location changes by the performers and audience divided up the evening into smaller sections. This meant that spectators could experience aspects of the pathways/ steps/walking theme.

(Ott 2001: 60)

The arrangement of the piece is close to open-air theatre, but it is more akin to music theatre projects of the 1960s and 70s, for example Meredith Monk’s Juice: A Theatre Cantata in 3 Installments (1969) and Vessel: An Opera Epic (1971). Both of these projects by Monk are performed in three different stages. The locations in Juice become smaller and more private, while those in Vessel become larger and more public.17 The fourth ojota project by Ott “kidnaps” the listeners and spectators in a hall on the outskirts of Bielefeld before the audience is then brought (in part two) into the “bitter February cold” where, “from behind a massive gravel/sand/waste landscape”, a “self-luminous procession” emerges, “which is chased off by the actors (with Bernhard texts)” (Ott 2001: 60). The performance of ojota III follows in part three (‘inside’) after an acoustic transition in full darkness. Ojota IV “is a workshop and journey of self-discovery, a trip to the frontiers of art and an allegory for vagrancy” (Loskill 2000: 64). For the middle section outdoors, Ott interweaves sentences from Thomas Bernhard’s Gehen into the panorama of the ‘shoe work’.

Bernhard’s story must have been more than a mere source of text for ojota, however. The complexity of its descriptions of events, the overlay of quotations, the merging of voices as well as the presentation of people and objects in this text, and the similar expressions relating to speaking, walking and thinking that are frequently repeated though in a different way, were certainly formal reference points during the creation of ojota. This refers not only to the increase in the number of associations with shoes in the individual pieces, but also to the working process divided into several parts. The cycle in Ojota V was further developed for three performers with shoes, tables, stools and an accordion (Drochtersen-Hüll, 2002).

Hafenbecken I & II. umschlagplatz klang (2005/2006) and other compositions for public spaces including landscapes

Alongside pieces that use the concert hall as a stage, or pieces for extended theatre spaces, Daniel Ott regularly develops projects for public venues such as city spaces, industrial areas or natural landscapes. Even ski-lifts have been used, for example in skilift / klang, “open air music for trumpet, brass band, ski-lift masts and ringing bells” (Heiligkreuz/Entlebuech 2003). He has even created his own experimental field in this area with the Festival Rümlingen in Switzerland, in which many international artists now take part.18 The starting points for these projects are again the characteristics of the existing environment, particularly buildings, functional industrial facilities, scenic water structures, hills, woods, meadows, railway lines or roads running through. (Hafenbecken I & II. umschlagplatz klang for 68 instruments was conceived for a performance at the Rhine Harbour in Basel and received its premiere in 2006 with the Basel Sinfonietta). It was created together with the director Enrico Stolzenburg, the costume designer Angela Zimmermann and the lighting designer Michael Gööck.19

Behind the sound event ‘Hafenbecken I & II. umschlagplatz klang’ were the musicians Guido Stier and Numa Bischof from the Basel Sinfonietta (of which Bischof is the former managing director), who were looking for music for a ‘moving orchestra’ in a particular location in Basel – i.e. they were explicitly looking for music to be played outside of a concert hall. After considering various locations (Lange Erlen, Kasernenareal, etc.), we opted for Rhine Harbour in Basel. The first sound experiment took place in November 2002 with ten musicians from the Basel Sinfonietta in the large hall of the transhipment yard. There were further experiments over the next three years to continue to investigate the acoustic and ‘theatrical’ possibilities of the entire location more precisely.

(Ott and Stolzenburg 2006)

As with the music theatre projects mentioned above, a performance plan used at the end was developed gradually during the rehearsal phase. “The first question we asked ourselves was ‘How does the location “itself ” sound without using any additional sounds?’ On first inspection, we noted the strong smells at the harbour and we heard the sound of water, seagulls squawking, ship horns, metal welding, sounds from the railways, cranes, ships and the unloading of goods from containers –a different acoustic environment with sounds from all four directions and which fluctuated heavily depending on the time of day and light. How could additional sounds from musical instruments be linked with the harbour sounds without disturbing the existing sound characteristics of the location? We adopted an improvisational approach to the music in the different sound experiments that began three-and-a-half years before the first performance. Many ideas came about jointly with the orchestra musicians involved in the project” (Ott 2008: 37).

A ‘constructed’ level of sound was added to the improvised harbour music and this emerged from the number 17. A 17-tone series was derived (with quarter tones) from the 17 stations in the first part of the project. “Each of the 17 stations in the first part of the performance has its own ‘main music’ and its own interval; the 17-note chord emerges at the beginning, and the first tone is naturally the ‘Rhine sound’ E flat major” (Ott and Stolzenburg 2006). One can see here how Ott finds the tones for his music. Even rhythmic structures stem in part from data he has ‘found’, for example in ojota I they emerged from the proportions of changes in light (sunrise, sunset, civil twilight, nautical twilight, darkness).

Hafenbecken I & II. umschlagplatz klang was performed in three stages. In the first section, with 17 stations, live sounds were ‘installed’ or sound sources were set in motion in particular locations of the harbour. The audience wandered between the different locations or with the ‘moving orchestra’. There were drums on a filling system, electric guitars on a travelling railway carriage or double bass players on a boat and trombonists on construction cranes. The second stage, after sunset, saw “common sound signals and 68 very quiet chords, harmonies with minimal differences that the harbour ‘coloured’ in the advancing twilight” (Ott 2008: 39). The third section was room music for the harbour’s large freight hall.

The musicians streamed into the hall at the beginning of part three, distributed themselves in the playing positions on the various floors around the spectators and then left the hall at the end in the opposite direction. In doing so, they continued the movement they had started, the stream of sound disappeared in the distance and they traced an arc to the open start of the evening.

(Ott 2008: 39)

Daniel Ott’s place-related projects and landscape compositions provide particular evidence of his impulse to create musical and theatrical perceptual offers, but which can barely be perceived as stagings. One has to see them as artistic settlements and remove them from the given setting in order to make the ‘natural’ surroundings apparent. Ott thereby brings the audience into ‘experimental’ situations in different ways. If the public loses its orientation in ojota IV, as the path and goal were not revealed when the spectators were kidnapped and taken from the theatre, then everything in the landscape composition remains open: so where do the listeners and spectators go in order not to miss the ‘artwork’? Ott’s ‘communication’ with the public is explained more clearly using two concluding examples.

Ott was in charge of the musical arrangement of Peter Zumthor’s Swiss Pavilion for the Expo 2000 in Hanover. Zumthor had built a wooden house – called Swiss Sound Body – that was an open structure whose inner space was organised like a labyrinth with many corridors and open spaces that opened up like yards. Ott’s musical furnishing and ‘performance’ in the building was part of a complete staging concept: alongside Ott, Plinio Bachmann was responsible for writing/words, Max Rigendinger for gastronomy, Karoline Gruber for staging and Ida Gut for clothing.20

The music formed one element in the house: “There was music for 12 hours on each of the 153 days the Swiss Pavilion was open. Each of the fifteen musicians played for five to six hours each day between 9.30am and 9.30pm in shifts of roughly three hours and in accordance with a changing plan in the sound rooms and corridors of the sound body: six accordionists, six hammered dulcimer players and three musicians who improvised with changing instruments (trombone, tuba, trumpet, alphorn, saxophone, voice, etc.)” (Ott 2001: 64). It was envisaged from the outset that there would be ‘acoustic rooms’ in Zumthor’s building, for example, certain open spaces or places where people could communicate. They encouraged people to linger and listen. The music thus grabbed the visitors’ attention for a certain period of time and at the same time created an individual atmosphere. In this way, the building was a ‘tuned space’ from which individual voices stood out.

The basic sounds provide sound material above which the musicians improvise; accordionists and hammered dulcimer players investigate the possibilities offered by the basic sounds during the rehearsal phase. Improvisation rules and variation possibilities are tested/discarded/developed further; in the sound body, the freely improvising musicians respond to the basic sound and provide additional stimuli: the basic sound is different every day, is always changing.

(Ott 2001: 65)21

Figure 2: Sketch by Daniel Ott, book Wittener Tage für neue 2009, p. 15.

Visitors were also surprised by particular sound events (e.g. eruptions or breaks). By turning a corner in the labyrinth, one could suddenly find oneself in an opening that was immersed in a particular atmosphere. The wood acted as a sound absorber, so although one suspected that something was happening, one was not prepared for what exactly would happen. An acoustic homogenisation of the building was linked with numerous local events.22 It was not intended for the focus to be on the allusions to Switzerland, but it seems obvious that the country is being symbolically transported into an architectural body that is open on all sides and a home and resting place for ramblers. This also relates to sound ecology, the presence of natural or social ‘soundscapes’ that were captured in Ott’s project for the pavilion and installed there.

The interpreters play their own music in the windows: folk music from their native countries, their own style of music. For me, this is an opportunity to make the diversity of the 350 participating musicians and their music audible throughout the exhibition.

(Ott 2001: 66)

In contrast to many music projects where sounds from landscapes or urban spaces are ‘captured’ in electro-acoustic compositions and displaced in other spaces, musicians performed the soundscape of the Swiss Pavilion fresh each day. The focus of the work was not on a constant, identical musical arrangement of the space, but on its ‘living’ metamorphosis.

Daniel Ott’s landscape composition Blick Richtung Süden was conceived for the Witten New Chamber Music Days 2009. The composer and the director Enrico Stolzenburg commented on the project as follows:

The public stands on the platform at the foot of the tower at Hohenstein that was built in memory of the industrialist and parliamentarian Louis Berger in 1902. There is a breathtaking view south of the floodplains of the Ruhr, a panorama of nature and civilisation: road traffic and trains pass through the idyllic riverscape with small islands, meadows and hill ranges, the Ruhr swells up at the water works, and the quarry, the Witten-Bommern Bridge and the neighbouring industrial site show the area was shaped by man. One can hear traffic and industrial sounds alternating with rather chance sounds produced by nature and animals. For beholders of the scene, a sound postcard opens up that captures the contradictions of the southern Ruhr region in a unique and concentrated way. The acoustics of the area are largely dependent on the season – e.g. the water levels of the Ruhr determine the intensity of the noise at the power plant – we form the final dramaturgy of our sound image during the rehearsals before the performances in which both amateur musicians and clubs from Witten and the surrounding area also took part.23

Figure 3: Daniel Ott: Blick Richtung Süden (2009). Copyright Enrico Stolzenburg.

In the landscape composition for five trumpets, two trombones, one clarinet, percussion, live electronics, homing pigeons, canoeists and brass band (in Witten), the brass instruments are predominant and enter into a dialogue with far off places.

Sounds are captured and blasted out; from a far-off meadow, even from the platform of a sluice, four trumpeters and two trombonists send out […] their sound signals in the direction of the Berger Tower from where a fifth trumpeter replies. Tape recordings boost the landscape’s sounds. The sound image is enhanced by lively gestures from sport and play activities far off and close by, among the latter a squadron of canoes approaching the sluice from a distance.

(Rohde: 2009)

The scenery is described differently in another report: “A ‘concert installation’ made up of sounds from nature, civilisation […] and echo-like brass calls between valley and tower, and in which art and reality, chance and purpose mix together until they can no longer be recognised. Whoever had the opportunity to attend this ‘sound postcard’, which exaggerates the aesthetic contradictions of the southern Ruhr region […] on several occasions was able to experience how the visual and acoustic colours of the staging were subject to change on a daily basis” (Wieschollek 2009: 80).

Working with existing natural, architectural and industrial elements, and those developed by society, a staged, perceptual offer was created. The recipients, those present, on the one hand absorb a Gesamtkunstwerk, listen to a staged overall situation and observe an artistically arranged big picture, at least in some sections, but on the other hand they understand the performance of the artwork’s various components in individual and selective reception stages, that is, they follow the artistic linking of the individual elements.

Conclusion

Music and theatre are inseparable in a very specific way in Daniel Ott’s works. It is not just that a musician, a visible artist on the stage, becomes a stage character at the same time, or is one already; biographical, professional and social influences, individual characteristics, inclinations and aversions, short-term and long-term goals, interests, associations and special skills – all of a person’s characteristics and contexts imaginable play a role in or feed into Ott’s works of music theatre. Everyday life becomes music theatre. This not only concerns the people involved in the works; even harbour basins, ski-lifts or railway viaducts and sections of landscape are themselves natural or constructed theatre locations that become music theatre. Music is attached to existing sounds, embedded in a soundscape and used as a staging tool, the latter noticeable at varying degrees of intensity. One may ask why the composer has dedicated himself more intently to public spaces and large scenic dimensions in recent years and what development possibilities they offer him. Firstly, the research work to be carried out ahead of a project is changing considerably: more time for the development of the landscape, historical factors or land-use plans and the social as well as acoustic structure of an occupied landscape need to be considered, for example. The information collected at this stage is probably more substantial and comprehensive than that acquired in the work with musicians from a small ensemble, but it is probably less personal and acquired from a greater distance. In any case, the composer is still always the one that registers, that is, takes in, what ‘is there’ in the first instance and the impressions of his work colleagues are added to this. In this way, Ott is a filter and a coupling that respectively sorts and connects the existing elements, associated thoughts, new material, far-off geographical areas as well as aspects that are immediately to hand. Communicativeness, openness and loose ends are all part of this working process. The performers involved do not merely execute Ott’s instructions but are co-creators of the pieces and projects. There is no question about the authorship of the works, however, as the artistic direction and organisation of processes is in the hands of just one person’s (or a management team). That said, Ott is not a supervisor who gives orders during these work processes; he is more a contact man and an instigator, a catalyst and an achiever.

(Translation: Nick Woods)

References

Cage, John (1958) “Experimental Music”, in Cage, John (1961), Silence, Hanover: Wesleyan University Press.

De Certeau, Michel (1988) “Praktiken im Raum”, in Michel de Certeau, Kunst des Handelns, translated by Ronald Voullié, Berlin, pp. 179–238.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika (2007) “Theatralität und Inszenierung”, in Fischer-Lichte, Erika, Horn, Christian, Pflug, Isabel, and Warstat, Matthias (2007) Inszenierung von Authentizität, Tübingen and Basel: A. Francke, pp. 9–28.

—— (2004) Ästhetik des Performativen, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Hönig, Roderick (ed.) (2000) Klangkörperbuch, Lexikon zum Pavillon der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft an der Expo 2000 in Hannover, Basel, Boston and Berlin: Birkhäuser Verlag Jowitt, Deborah (1997) Meredith Monk, Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press. Loskill, Jörg (2000) “Reise in das Schuh-Land. Daniel Otts Ojota IV in Bielefeld”, in Opernwelt 41, vol. 4.

Manz, Reinhard (2007) Hafenbecken I & II, DVD, point de vue DOC, Basel.

Von Matt, Sylvia Egli et al. (2008) Das Porträt, Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft.

Ott, Daniel (2008) “Am Umschlagplatz Klang: Anmerkungen zum Experimentellen in der Musik”, in Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 169.

—— and Enrico Stolzenburg, Musik für ein “bewegtes Orchester” an einem besonderen Ort, www.sinfonietta-archiv.ch/PPL/Saison06/Text_S1_2006.htm (accessed on 18 June 2010).

—— (2001) “Voraussetzungen für ein Neues Musiktheater – Gesamtkunstwerk”, in Kolleritsch, Otto (2001) Das Musiktheater – Exempel der Kunst (= Studien zur Wertungsforschung, vol. 38), Vienna and Graz: Universal-Edition, pp. 50–81.

—— (2000) “ojota – Schuhe, Schritte, Wege. Gespräch zwischen Daniel Ott und Matthias Rebstock”, in Sanio, Sabine, Wackernagel, Bettina and Ravenna, Jutta (2000), Klangkunst – Musiktheater. Musik im Dialog III (= Jahrbuch der Berliner Gesellschaft für Neue Musik 1999), Saarbrücken: Pfau-Verlag.

Rebstock, Matthias (2007) Komposition zwischen Musik und Theater. Das instrumentale Theater von Mauricio Kagel zwischen 1959 und 1965 (= sinefonia 6), Hofheim: wolke Verlag.

—— (2005) “‘Just do your Job’: Rollenkonzepte im neuen Musiktheater”, in Ott, Daniel, Ott, Lukas and Jeschke, Lydia (2005) Geballte Gegenwart. Experiment Neue Musik Rümlingen, Basel: Christoph Merian Verlag, pp. 44–7.

Rohde, Gerhard (2009) “Klingende Landschaften: Wittens Tage für neue Kammermusik drängen ins Freie”, Neue Musikzeitung 58, vol. 6, www.nmz.de/artikel/klingende-landschaften (27 March 2010).

Rust, Sarah (2009) “Igor Strawinskys Poétique musicale – Ein musikästhetisches Credo”, MA thesis, Freie Universität Berlin 2009.

Schoenberg, Arnold (1941) “Composition with Twelve Tones (1)”, in Schoenberg, Arnold (1975), Style and Idea, edited by Leonard Stein, London: Faber &Faber.

Schmidt, Jochen (2002) Pina Bausch ‘Tanzen gegen die Angst’, Munich: Econ & List Taschenbuch- Verlag, pp. 87–98.

Schouten, Sabine (2007) Sinnliches Spüren: Wahrnehmung und Erzeugung von Atmosphären im Theater (= Recherchen, vol. 46), Berlin: Theater der Zeit.

Schulze-Reuber, Rika (2005) Das Tanztheater Pina Bausch: Spiegel der Gesellschaft, Frankfurt am Main: R. G. Fischer.

Martin Seel (2002) Sich bestimmen lassen. Studien zur theoretischen und praktischen Philosophie, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp

Simpson, J. A. and Weiner, E. S. C. (ed.) (1989) The Oxford English Dictionary, vol. 11, Oxford.

Straus, Erwin (1930) Die Formen des Räumlichen. Ihre Bedeutung für die Motorik und die Wahrnehmung, in Straus, Erwin (1960), Psychologie der menschlichen Welt. Gesammelte Schriften, Berlin, Göttingen, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 141–78.

Stravinsky, Igor (1970) Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons, Cambridge: Harvard University Press [1947].

Johann Gottfried Walther (1732) Musikalisches Lexikon oder musikalische Bibliothek, Leipzig, reprint: Richard Schaal (ed.) (1953), Kassel and Basel: Bärenreiter.

Wieschollek, Dirk (2009) “Landschaft mit Klangwolke. Die Wittener Tage für neue Kammermusik gehen hinaus ins Freie”, Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 170, vol. 3.

Note

1. If not stated otherwise all translations of quotations originally in German are by Nick Woods.

2. For the questionable authorship of Stravinsky’s writing and the context of the quoted statement, see Rust 2009.

3. Cf. Simpson and Weiner 1989: 543.

4. For further information about Daniel Ott’s works and current projects, see www.danielott.com.

5. Cf. Seel 2002.

6. Cf. Ott 2000: 95.

7. Cf. also Schmidt 2002: 87–98.

8. The stages of work which go into a journalistic portrait, starting with reflection on themes and research, are also comparable; cf. also von Matt 2008.

9. Cf. Rebstock 2005.

10. All quotations from Daniel Ott, skizze – 7½ bruchstücke, score, dated 8 March 1992.

11. Cf. also Rebstock 2007.

12. “Zwischen Cage und Fellini: Daniel Otts 7½”, in Basler Zeitung, 11 August 1993. Cf. also www.danielott.com/presse/ (06 June 2010). The film was broadcast on the Swiss TV channel DRS.

13. See also Ott 2000: 94–8.

14. Cf. for example de Certeau 1988.

15. Cf. the DVD documentary of the premiere in Donaueschingen by Reinhard Manz, point de vue DOC, Basel 1999/2008.

16. Cf. Ott 2001: 57.

17. Cf. Jowitt 1997.

18. Cf. Ott 2005.

19. Cf. Manz 2007.

20. Cf. Ott 2001: 63 et seq.

21. The basic sound “is made up of 153 sounds and 23 eruptions […] The sounds are rather flat, wide – sound colours making their way through the space. The eruptions are loud, flamboyant, rhythmic, imprecise, intermittent – i.e. they surprise. The basic sound and eruptions always alternate differently. The basic sound is a new plan each day. The existing or pre-composed sounds were adjusted to the sound body during sound tests early in 2000 in which almost all the musicians took part. During the tests, the musicians responded to the basic sound with their own scenic ideas and sound improvisations. To a certain extent, the musicians are therefore co-composers” (Hönig 2000: 88).

22. On the sound homogenisation of the space, cf. Straus 1930. On the creation of atmospheres, cf. Schouten 2007.

23. Wittener Tage für neue Kammermusik 2009, programme book, Saarbrücken: Pfau-Verlag 2009, p. 14. Cf. Rohde: 2009.