IN THE DARKNESS of the early hours of 19 June, the ships of TF 58 sliced through the waters of the Philippine Sea, heading east. Trailing some 350 miles to the west was Admiral Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet.

Though it was dark, on both sides there was activity on the ships and in the air. Aboard the carriers, aircraft were being gassed and ammunition loaded. Mechanics were carefully checking over the planes. Below decks, pilots and seamen alike tossed fitfully as they thought of what daylight might bring. Others less concerned or more able to control their fears were asleep almost as soon as their heads hit the pillows. On all ships, lookouts carefully searched the sky for that blob that was a little blacker than the darkness, carefully scoured the water for a small ripple that might be the wake of a periscope. Up on the bridges and in the “flag countries” of the ships, admirals and ensigns, captains and seamen were discussing the possibilities of action on this day.

Bogeys were on the scopes for some time after midnight, but few closed. Then, at 0100 a snooper (probably from Guam) began dropping flares near TG 58.1. The destroyer Cowell fired on the plane and a night fighter was sent after the intruder, but neither had any success. Equally unsuccessful was the destroyer Burns’s attempt to put out the flares by the unconventional method of depth-charging them.

Far to the west, Lieutenant H. F. Arle and his crew had been out in their PBM for over two hours when the radar operator picked up something on his scope. It was 0115. Forty glowing blips concentrated in two groups could be seen on the scope. Arle had hit the jackpot—the Japanese Fleet! (Actually, only Kurita’s C Force had been picked up, but that was good enough.) The ships were only seventy-five miles northeast of the Huff/Duff fix.

Arle immediately began sending his contact report. There was no reply from any station. Again and again the message was sent, and again and again there was no answer. Arle’s report had been heard, but not by those to whom he was sending it. A plane from another command some distance away heard the message but did not offer to relay it. At Eniwetok the seaplane tender Casco also heard the message but then sat on it.

Arle continued scouting and did not return to the Garapan roadstead until shortly before 0900. By then the information was useless. Thus, an atmospheric “glitch,” and some poor judgment by those who did receive the report, combined to keep the Americans from using one of the most potentially valuable sighting reports of the entire battle.

The Enterprise began sending fifteen Avengers off on a search mission at 0218. Every forty-four seconds one of the big planes was catapulted from the “Big E’s” deck. Finally, Bill Martin (back in the cockpit following his sojourn in the waters off Saipan) led the radar-equipped Avengers westward. Martin’s VT-10 was one of the few U.S. squadrons proficient in night flying. In February they had shown their capabilities with an outstanding night attack during TG 58’s raid on Truk.

Now the Avengers were flying to find the Japanese. For one hundred miles they flew on a course of 255 degrees until they reached an arbitrary fix called Point Fox. At 0319 they reached Point Fox and separated to search individually. For another 225 miles, narrow five-degree sectors were flown between 240 and 270 degrees. But again the Americans missed the Japanese by a hair’s breadth. Kurita’s C Force was still about forty-five miles away. Only a couple of obvious aircraft targets and a submarine contact marred the blankness of the radarscopes.

Ozawa, meanwhile, was forming the Mobile Fleet into its battle disposition. By 0415 the movement was completed and Ozawa’s force was ready for action. Between 0430 and 0445 Ozawa sent out sixteen Jakes (of which ten would not return) from C Force, which was now at about 13°15’N, 138°05’E. The floatplanes were to search between 315 and 135 degrees and range out to 350 miles. A second-phase search of thirteen Kates and one Jake from CarDiv 3 and the cruiser Chikuma was launched between 0515 and 0520. Seven of these planes were lost during the searches. These planes were to search between 000 and 180 degrees to a distance of 300 miles. Ten minutes after the last Kate had taken off, the Shokaku began launching eleven Judys, with two Jakes from the Mogami tagging along. They were to scout an incredible 560 miles.1

Thus, by 0600 Ozawa had forty-three planes out searching for the Americans. One of these planes was forced back by engine trouble, but it was searching a sector where there were no U.S. ships. With this number of planes on search missions and most of the rest being readied for the impending strikes, the number of planes available for other tasks was very limited. Only small CAPs were flown over the Mobile Fleet, and antisubmarine patrols had to be called off altogether—a decision that would hurt the Japanese a few hours later.

Snoopers began appearing near TF 58 (now heading east by north) shortly after 0500. All escaped interception. By 0530 Mitscher’s flagship Lexington had reached 14°40’N, 143°40’E, about 115 miles west-southwest of Tinian. At this time the ships turned to the northeast to begin launching the dawn search, CAP and antisubmarine patrols.

Although enemy ships again were not seen, the searchers (especially those from the Essex) had a profitable morning shooting down enemy aircraft. Two Jakes, two Kates, and a Jill were picked off by the pilots of Fighting and Bombing 15. Hellcat driver Lieutenant J. R. Strane got the first two kills. Strane was escorting a “2C” when the bomber pilot pointed out a Jake about ten miles away, heading northeast. The Americans passed over and behind the blue-black painted Jake, then Strane whipped his Hellcat around and got a perfect full deflection shot at the enemy’s left side. Six .50-caliber guns poured slugs into the Jake’s left wing and cockpit. The wing began to burn as the floatplane pulled up sharply. At 500 feet the Jake suddenly began spinning and corkscrewed into the water. Nothing remained on the surface but one pontoon.

A few minutes later Strane latched on to what he identified as a dark brown Jill. This time the enemy crew was more observant and tried to run for it. The Jill disappeared into a cloud and Strane followed it in. When he broke out the Jill was off his port beam. Before the Jill could duck into another cloud, Strane had gotten good hits on its wing and fuselage. As the enemy plane melted into a nearby cloud, it was burning. Strane kept after it. A few seconds later both planes popped out of the cloud. The Jill was dead ahead. Strane got in another good burst and the Jill’s rear gunner, who had been firing, was silenced. Strane overshot the dive bomber, and as he passed he could see its pilot slumped forward. With flames pouring from the left wing, the Jill slowly began to climb. Then it stalled out, began to spin and went straight in from 3,000 feet.

Another Essex search team was also doing quite well against Japanese aircraft. A blue-black colored Jake was spotted low under a cloud by the dive-bomber gunner and pointed out to Ensign J. D. Bare in his Hellcat. Bare climbed to 500 feet to get above the Jake and began to close. The floatplane turned away, then turned back toward him. Bare got off a short burst that peppered the tail of the enemy plane. Realizing his predicament, the Japanese pilot hauled his plane around sharply and began a wingover. The Hellcat pilot stayed on his tail and fired only twenty rounds when the Jake exploded and dove into the sea.

About thirty minutes later, the pilot of the Helldiver, Lieutenant (jg) Clifford Jordan, saw a Kate heading west-southwest at 1,500 feet. Jordan waggled his wings at Bare and they began climbing up to the Kate’s altitude. As Bare was having difficulty picking up the torpedo plane, Jordan made the attack. The Japanese crew apparently spotted their attackers for they turned toward them and headed for the water. Jordan made one pass, firing a long burst with his 20-mm guns. Flames spouted around the Kate’s cowling and cockpit. It staggered, fell off on a wing and slammed into the water. The Kate’s rear gunner was firing even as his plane hit.

Bare and Jordan were not through yet. At 0935 the two ran into another Kate, this one heading northwest at high speed. The two pilots swung around and took up the chase. After five minutes at military power, Bare was able to get in range. The Kate was faster than he thought and Bare missed astern with his first burst. With only one gun firing, Bare was able to start the Kate smoking with a second burst. Jordan took over as Bare dropped back to recharge his guns. The Helldiver roared in with both its fixed and free guns firing, but no damage was seen. Guns recharged, Ensign Bare came back into the fray and set the Kate ablaze with a good solid burst. The Kate pulled up and its pilot jumped out, but he was too low. His chute was just starting to open when he hit the water.

The American commanders were now getting somewhat jumpy, not having found the Japanese Fleet. Spruance ordered Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill off Saipan to get more long-range patrol planes into the air and to extend their range to 700 miles. The Americans figured they were “going to have the hell slugged out of [them]” and were “making sure that [they] were ready to take it.”2

On Tinian Admiral Kakuta called up fifteen Zekes and four bombers from Truk to reinforce the few planes still flyable on Guam. With this support, the Japanese could count on only fifty planes available at Orote field. It was a far cry from what had been planned, yet Kakuta was still sending Ozawa and Toyoda glowing reports about the successes of the land-based planes and the masses of them still available. Kakuta’s reports would not be helpful to the Japanese cause.

Enemy air activity increased around the task force as the carriers were launching planes for the morning searches and CAPs. At 0549 a lookout on the destroyer Stockham suddenly saw an enemy plane diving out of a low cloud directly at the ship. “It was a complete surprise and the first Jap plane that most of [the] ship’s personnel had ever seen.”3 The ship a made a hard swing to starboard. The plane’s bomb landed in the Stockham’s wake and failed to explode. The destroyer Yarnall then shot the plane down.

About the same time as the attack on the Stockham, TF 58 radars picked up bogeys near Guam. Four Monterey Hellcats were vectored over to take a look. They found two Judys, one of which was sent into the sea in an inverted spin.

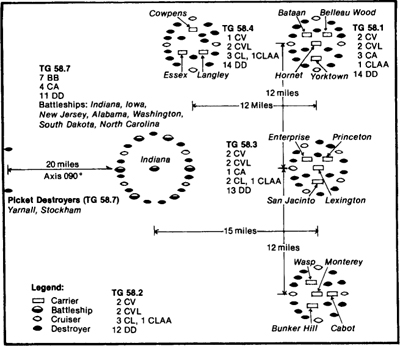

Disposition of TF 58 at start of action, 19 June 1944.

The sun began peering over the eastern horizon at 0542. With just a few clouds in the area, it looked like it was going to be another fine day. It also appeared that the rest of the day would probably be exciting. The situation was becoming “definitely tense.”4

With Japanese air activity around Guam increasing, Admiral Spruance rightly became concerned with the possibility of enemy attacks from there. He suggested to Mitscher that if the dawn searches were again unsuccessful, a strike against Guam and Rota might not be a bad idea. Mitscher was not too keen on the suggestion; he told Spruance that he did not have enough bombs to neutralize both islands, and that all he could do was watch the situation with fighters until the Japanese tired of the game.5

Spruance’s suggestion was sound; it would have been well for Mitscher’s planes to plant a few bombs on the runways, to keep the Japanese planes out of action. Though the number of planes on Guam were not enough to be considered a decisive factor, the island was to remain a hot spot throughout the day. The carrier commanders, however, were more interested in their opposite numbers and attacks on Guam were considered purely secondary. Admiral Montgomery sent a message addressed to Mitscher, but really intended for Spruance, saying, “I consider that maximum effort of this force should be directed toward enemy force at sea; minor strikes should not be diverted to support the Guam–Saipan area. If necessary to continue divided effort, recommend detachment of sufficient force for this purpose.”6 No division of TF 58 took place, however.

About 0600 destroyers of TG 58.7 knocked down a Val which had probably come from Guam. Another snooper went down to the guns of the Cabot’s CAP. At 0619 TF 58 changed course to the west-southwest. It was hoped that the task force could get close enough to the enemy to be able to launch strikes. But four launches between 0706 and 0830 slowed the advance considerably. At 0930 TF 58 was only about eighty-five miles northwest of Guam and by 1023 it was not much farther west than when it had started the morning.

At 0540 several ships had picked up signs of activity over Guam on their radars. At this time Guam was ninety miles distant. A division of Hellcats from the Belleau Wood was vectored over to take a look. When the four fighters arrived over Orote at 0600, they found the field a beehive of activity. Orote was certainly not out of action.

Lieutenant C.I. Oveland, leading the quartet, was studying the situation when puffs of flak blossomed a couple of thousand feet below. As he led his planes away from the flak, Oveland (like any good fighter pilot) kept his head on a swivel and saw four Zekes trying to bounce the Belleau Wood planes from above and behind. Yelling “Skunks!” over the radio, Oveland at the same time racked his F6F around in a tight turn. The other three pilots followed suit and the Hellcats came roaring head-on into the Zekes. Oveland fired and his victim snapped over into an aileron roll that continued until the fighter smacked into the water. At the same time Lieutenant (jg) R. C. Tabler got another Zeke that went straight in.

The action was just beginning. More Zekes jumped into the fight before the Americans could reform. Oveland evaded one attacker by diving out of the action at over 400 knots indicated. When he climbed back to 15,000 feet and saw more enemy planes jumping into the fight, Oveland decided to call for help from TF 58. Meanwhile, a Zeke tried to pick off Tabler but was picked off himself when Tabler’s wingman sawed off half the attacker’s right wing with his six “fifties.” Tabler took shots at two Zekes but had to break away when four other fighters started edging in from behind. One of the enemy pilots Tabler was chasing threw what looked like a coiled band of metal over the side of his aircraft. Though it flashed close to Tabler’s plane, the coil caused no damage. The fourth member of the division, Ensign Carl J. Bennett, lost the other three pilots during the battle and had been shot up in the process. One shell came whistling through his canopy, showering plexiglass that cut the back of his head. Bennett still had time to smoke a “Tony” for a damaged claim. Oveland finally got his group reformed. Though enemy planes remained nearby, they had gotten wary and made no more attacks.

Following Oveland’s call for help, Admiral Clark sent twenty-four more fighters to Orote and advised Mitscher of the situation. Meanwhile, TG 58.2 radars noted another group of enemy planes near Guam. Cabot fighters were sent to intercept and were about ten miles northwest of Guam when they heard Oveland’s report. Within minutes they were mixing it with a group of Zekes. Six of the enemy fighters fell under the guns of the Hellcats, with Lieutenant C. W. Turner leading the way with three Zekes.

Following this action, things calmed down over Orote for a short while; the Japanese planes had either been shot down, left the area for safer climes or, more likely, landed and taxied to carefully camouflaged parking areas for refueling and rearming. On the latter point the Yorktown air group commander later commented, “Pilots were unanimous in the opinion that the field was practically deserted while photographs showed a considerable number of planes.”7 Mitscher was probably now wishing he had sent planes to Guam and Rota at dawn to keep the fields unserviceable; it was obvious TF 58 would be in for a hard time today.

The lull over Guam was short, as action heated up again shortly after 0800. Another group of enemy planes in the vicinity of Guam was detected at 0807. Fifteen Hornet and Yorktown fighters were already on the scene and quite a few more from other carriers were sent to help out. At 0824 the enemy was tallyhoed and an hour-long series of fights around Guam began. Belleau Wood fighters were again in the thick of the action.

Eight of the VF-24 F6Fs were jumped by about fifteen Zekes at 0845 near Orote. Big scorer for the Americans was Lieutenant (jg) R. H. Thelen, who downed three of the enemy fighters. Thelen bagged his first by following the Zeke through a slow roll and twisting dive. The Zeke blazed and went in. Two more Zekes came in on Thelen and his wingman, Lieutenant (jg) E. R. Hardin, from 12 o’clock low. Thelen flamed one but the other Zeke, though smoking, broke around to get on Hardin’s tail. Hardin led the Zeke in front of Thelen, who proceeded to stop the attack by sending the enemy plane down in flames. As Thelen led his division home, one more enemy pilot attacked, but Lieutenant (jg) L. R. Graham got this one from dead astern. The Zeke exploded, throwing its pilot out. The Japanese flier was able to pull his ripcord and floated down under his chute, landing just offshore. The Fighting 24 pilots claimed seven Zekes destroyed and six others as probables or damaged.

The Bunker Hill had sent twelve Hellcats to Guam, arriving over Orote at 0920. Planes were taking off and landing at the field, and there were many enemy aircraft in the area. The VF-8 pilots began engaging Zekes and Hamps almost immediately. Combat extended from 16,000 feet down to sea level. Lieutenant (jg) H. T. Brownscombe’s plane was hit several times in the first moments of the battle and he scurried for the safety of a cloud to assess the damage. When he discovered that, aside from a knocked-out gun, his damage was minor, he tried to rejoin his division. However, whenever he popped out of the cloud, he discovered a bunch of angry Japanese pilots buzzing around. Twice he came out of the cloud to find an enemy fighter in his sights. Both were blasted out of the sky. Finally, Brownscombe was able to edge away and rejoin his teammates.

The four planes led by Lieutenant (jg) L. P. Heinzen dropped down to strafe the airfield. One Zeke was hit as it was taking off and it ground-looped in a cloud of dust and smoke. Heinzen and his wingman, Lieutenant (jg) E. J. Dooner, dropped on a Topsy and a Zeke trying to land, and shot them both down. Dooner’s Zeke smashed into a group of parked aircraft. The two fliers then mixed it up with another pair of Zekes. Henzen got one, but Dooner’s oil line and gas tank were hit in the exchange of fire. The pair headed back for the Bunker Hill, but before they reached her, Dooner had to set his plane down in the water. Just as the Hellcat touched down, it exploded. Dooner did not get out. Though the loss of Dooner had taken some of the joy out of the victories, the thirteen planes the VF-8 pilots had shot down partially made up for his loss.

When some VF-16 fighters arrived over Orote most of the air battles had dwindled, but several Zekes could be seen taxiing on the field, along with a number of other planes parked around the field. The Americans immediately dropped down through moderate antiaircraft fire to strafe the runways. In repeated strafings, five or six of the parked aircraft were probably destroyed and several others damaged. None of the planes would burn, however, and it was thought they might have been degassed.

By the time the fighting around Orote was over the TF 58 pilots had claimed thirty Zekes and five other planes. This accounting is perhaps suspect (as were so many aerial claims by both sides during the war), but it is an indication of the intensity of the fighting. While some of the planes shot down had come from Guam, many were from Truk and Yap. Even though the enemy had lost heavily in the fights, Orote was far from being out of the battle. As the Americans rushed back to the task force in response to an urgent “Hey, Rube!”, a great deal of activity could still be seen on the airfield.

While the battles were going on over Guam, Japanese scouting efforts had paid off. At 0730 a Jake crew returning from the limit of their search spotted their quarry. They picked out two carriers, four battleships, and ten other vessels—apparently Lee’s and Harrill’s groups. A contact report was immediately transmitted to Ozawa. This report was designated the “71” contact. It placed the Americans 160 miles almost due west of Saipan. Four minutes later another Japanese plane verified the previous report, sighting fourteen ships including four battleships. The pilot of this Jake soon saw four more carriers. Ozawa now had the information he needed to launch his attack.

Ozawa figured he was about 380 miles from the Americans, with his van force about eighty miles closer to the enemy. He was just where he wanted to be. His planes could hit the Americans easily, but the enemy could not hit back. But Ozawa was now operating under a badly flawed premise. Buoyed, but tragically misled, by the overly optimistic reports by Kakuta of smashing victories by the land-based planes and of a safe haven on Guam, Ozawa was ready for the decisive battle.

At 0807, shortly after receiving the “7I” report, Ozawa brought his A and B Forces around to due south to keep his range at about 380 miles from the enemy. C Force turned southwest to close slightly with the rest of the Mobile Fleet.

Aboard the Japanese ships everyone was eager for action—and none more so than Admiral Obayashi. Impatient to get at the enemy and wondering why Ozawa had not yet given the order to launch, Obayashi began launching his own strike at 0825. Preceded by two Kates from the Chitose (sent out at 0800 as pathfinders), sixteen Zeke fighters, forty-five Zeke fighter-bombers, each carrying a 550-pound bomb, and eight torpedo-laden Jills left the Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuiho. Not waiting for the planes of the other carriers to join them, the pilots of the 653rd Air Group flew east—to destruction.8

Ozawa had not been timid about launching his planes. He had merely been awaiting more contact reports. When no further updates reached him, he began launching the planes of his carrier division. At 0856 the first Zeke left the deck of the Taiho. The Shokaku and Zuikaku also began launching planes. This strike of the 601st Air Group, led by Lieutenant Commander Akira Tarui, was Ozawa’s big punch—twenty-seven Jills carrying torpedoes; fifty-three Judys, each with a 1,000-pound bomb; and forty-eight Zekes providing escort. Two more Jills were sent ahead as pathfinders. Finally, the Taiho launched a Judy equipped with packages of “Window” to be used to create confusion on the American radar screens.9

The strike Ozawa launched from his own group of carriers was larger than that Admiral Nagumo had sent against Midway. But the year was 1944, not 1942; the Japanese were the underdogs now. In addition, Ozawa made a serious error in not coordinating his attacks. Instead of one massive blow that might have had a chance of breaking through the defending fighters, the two groups were spaced out far enough in time for the Americans to attack each in overwhelming numbers. (Given Obayashi’s impetuosity, a coordinated attack may have been impossible, anyway.) The planes from Admiral Joshima’s carriers, which could have proved useful, were also held back for the time being. Perhaps Ozawa was reserving Joshima’s planes for cleanup work.

As the planes of the 653rd Air Group thundered east, the Hellcats of TF 58’s CAP were already busy. At 0927 three Essex planes were vectored to investigate one of the bogeys that were beginning to speckle the task force’s radars. This one turned out to be a returning Avenger with an inoperative IFF. Four minutes later an unfriendly contact was picked up by the Hornet some 40 miles to the north. A Bataan division sighted the bogey, a Zeke, shortly and dropped it in the water. Several other bogeys escaped the CAP a short time later.

It was 0930 when Admiral Mitscher finally received the 0115 PBM sighting. His comments upon receipt of the message are unrecorded, but they must have come right from the heart.

While the CAP was swatting down a few enemy planes, one snooper was flitting about its job unmolested. Plane No. 15, which had been launched from CarDiv 1 about 0530, was on the inbound leg of its search pattern when it ran across a group of American ships at 0945. The pilot immediately reported sighting three carriers and a number of other vessels at 12 22’N, 143 43’E. This report was called the “15 Ri” contact by the Japanese. Unfortunately, the pilot of this search plane forgot to correct for compass deviation, and the reported point was miles south of TF 58’s actual position.

Fifteen minutes later another searcher had better luck in plotting the position of TF 58 units when he observed several vessels, including carriers, at 15 33’N, 143 15’E. This position was about 50 miles north of the “7I” point and was designated the “3 Ri” contact. As these searchers sent back their reports and Ozawa readied more strikes, the first two waves of attackers swept in toward TF 58.10

At 0957 the Alabama picked up the planes of Obayashi’s 653rd Air Group at a distance of 140 miles. The Iowa, Cabot, and Enterprise quickly verified the contact. A few minutes later the task force flagship Lexington also had contact. The bogeys were bearing 260 degrees from the task force and were in two groups at 121 and 124 miles. Their altitude was estimated as 20,000 feet.

All ships not already at General Quarters quickly set the condition. Lookouts strained their eyes staring through binoculars, trying to pick out the speck of an enemy aircraft before it got too close. All 5-inch mounts that could rotated to face west. The 40-mm guns whined as their barrels weaved about in anticipation of the battle.

At 1005 Mitscher ordered the task groups, “Give your VF over Guam, ‘Hey Rube!’”11 Lieutenant Joe Eggert, TF 58’s fighter director, sent out the old circus cry for help and then settled down for a busy few hours. Eggert, along with the five task group fighter directors (TG 58.1—Lieutenant C. D. Ridgeway; TG 58.2—Lieutenant R. F. Myers; TG 58.3—Lieutenant J. H. Trousdale; TG 58.4—Lieutenant Commander F. L. Winston; TG 58.7—Lieutenant E. F. Kendall) had a big responsibility during the battle. It was their job to see that enough fighters were vectored to the right spot at the right time to handle each raid, while seeing that sufficient planes were held back for later attacks. While Eggert handled fighter direction for the entire task force, each task-group controller handled the planes of his group. Any fighter director could allot aircraft to the director on an individual ship or even shift planes between task groups. It was an enormously complicated job that was handled superbly by all concerned.

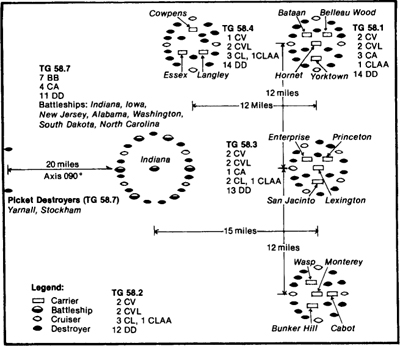

Movements of opposing forces 0000-1130, 19 June.

Movements of opposing forces 0900-2400, 19 June.

One area that could have caused problems during the day was communications. At this time TF 58 was in the process of changing over to newer radio equipment, and there were only two channels available that were common to all ships. Although these channels were badly overworked throughout the day, they held up, and the fighter directors were able to keep in touch with their planes.

Besides the excellent work of the fighter directors and the efficient use of radar, this day the Americans had an ace in the hole. Lieutenant (jg) Charles A. Sims, a Japanese language expert, was aboard the Lexington and was able to monitor the enemy fliers’ radio chatter, thereby learning their plans in advance.

Most of the carriers were not in an ideal position to receive an attack, for their decks had been spotted for a strike against the Japanese fleet. Decks had to be cleared for use by the fighters, so Mitscher launched all his dive bombers and torpedo planes to orbit to the east until the battle was over. Any planes on the hangar decks that could not be launched immediately were dearmed and defueled.

At 1010 TF 58 was ordered to prepare to launch all available fighters. Nine minutes later came the “execute.” Task Force 58 swung around to the east and into the wind. Mitscher ordered his ships to assume their air defense formation.12 By heading eastward TF 58 would be drawing away from Ozawa’s ships, but would be able to launch and land planes at will.

By now TF 58’s formation was slightly askew. Instead of the nicely aligned formation that had been planned, TG 58.1 was twelve to fifteen miles due east of TG 58.3, while TG 58.4 was bearing 340 degrees, TG 58.2 160 degrees and TG 58.7 260 degrees from TG 58.3. These groups were also about twelve to fifteen miles distant from the flag group.

The first fighters began leaping off the decks at 1023 as Eggert was already vectoring the CAP’s from the Princeton, Essex, Hornet, Cowpens, and Monterey. Not wanting to get caught with his Hellcats below the attackers, Eggert sent most of them clawing up to 24,000 feet, while keeping some down low in the direction of the attackers.

VF-I Hellcats on the Yorktown prepare to launch on 19 June 1944. The Hornet is in the background.

Within fifteen minutes, about 140 Hellcats had been launched, while 82 others already airborne streaked west. The launch was swift, but now the Americans were helped by the Japanese. When the enemy planes (now designated as Raid I) closed to 72 miles they began to orbit. Their lack of training had begun to tell, and it would eventually prove immensely costly to them. Instead of diving in and closing with the enemy—knowing their targets and tactics like veterans would—they were being told by their group commander just what they were supposed to do. This briefing took almost fifteen minutes and provided the Hellcats with the time to gain valuable altitude and distance toward the enemy. It also provided the task force with that extra time to launch the last of the fighters. As the last F6Fs took off, the planes that had been over Guam began returning for refueling and rearming. Lieutenant (jg) Sims had now found the attacker’s radio frequency and was relaying the gist of the Japanese leader’s briefing to Eggert.

Their briefing over, the enemy fliers broke out of their orbit to start their run-in toward their targets. They were met by a wall of Hellcats ranging from 17,000 to 24,000 feet. More fighters were waiting lower, ready to pounce on any enemy plane that might try to sneak through at low altitude.

Fifty-five miles from the task force, Commander Charles W. Brewer, skipper of the Essex’s Fighting 15, spotted the enemy. It was 1025. Brewer estimated the raid as twenty-four “Rats” (bombers), sixteen “Hawks” (fighters) and no “Fish” (torpedo planes). Brewer had missed some of the planes. Eight torpedo planes had been sent, along with sixteen fighters and forty-five fighter-bombers. The enemy planes were at 18,000 feet. Sixteen of the planes (identified as Judys; actually Zeke fighter-bombers) were bunched together. Two four-plane divisions of Zeke fighters were at the same altitude; one division on each flank. Bringing up the rear, between 1,000 and 2,000 feet higher, were sixteen more Zekes. These were in “no apparent pattern of sections or divisions.” Behind the onrushing enemy planes streamed thick contrails. (The atmospheric conditions causing the contrails would give the ships’ crews a view of the battle few had seen before.)13

Brewer’s planes were in a perfect position for a “bounce.” Brewer rolled over from 24,000 feet and led his four planes in for an overhead pass. Lieutenant (jg) J. R. Carr took his four fighters in from the other side and the enemy formation was thus bracketed. The eight Essex fighters slashed into the enemy and the formation disintegrated.

Brewer picked out the formation leader as his first target. When he closed to 800 feet he opened fire and the Zeke blew up. Passing through the debris of the plane, he pulled up shooting at another Zeke. Half a wing gone, the enemy plane plunged flaming into the sea. Brewer picked off another fighter with a no-deflection shot from about 400 feet and the plane spun into the water in flames. Clearing his tail, Brewer saw a fourth Zeke diving on him. Racking his big Hellcat around, Brewer was quickly embroiled in a hot fight with the Zeke.

Commander Brewer was able to get on the Zeke’s tail and began snapping short bursts at the violently maneuvering fighter. The Zeke pilot “half-rolled, then after staying on his back briefly pulled through sharply, followed by barrel rolls and wingovers.”14 The maneuvers did not save him. His plane caught fire and spiraled into the ocean. After this kill, Brewer found the raid had been broken up. He had had an excellent interception—four for four.

Brewer’s wingman, Ensign Richard E. Fowler, Jr., also had a good day. On the first pass Fowler sent a Zeke smoking into the water. Diving through to 6,000 feet, Fowler jumped a couple of circling Zekes but overshot and found them, plus one more, glued to his tail. Another Hellcat distracted the enemy, and Fowler pulled around after them. He tried a 60-degree deflection shot at one and was amazed to see the plane suddenly snap roll in the opposite direction. Then he noticed that ten feet of the Zeke’s wing was missing. The enemy pilot bailed out, but his parachute did not open.

Fowler turned toward another Zeke off his right side. When he opened fire the Zeke began to “skid violently from left to right, and then started to whip even more violently sideways.”15 The Zeke’s vertical stabilizer had been sawed off. Fowler kept pumping shells into the doomed plane until it burst into flames. He then joined two more Hellcats chasing a Zeke, but when the enemy plane reached a cloud the other pilots turned back. Fowler kept going and caught the Zeke on the other side of the cloud. Though firing at an extreme range of 1,500 feet and with only one gun working, he sent the fighter into the ocean. Fowler wound up this interception by damaging another Japanese plane with his one gun.

On the other side of the Japanese formation, Lieutenant (jg) Carr was doing quite well also. His first victim was a Zeke that blew up immediately. Carr pulled up in a wingover and found another fighter a “sitting duck.”16 His .50-caliber slugs torched the fighter and it spiraled in. Another Zeke then jumped him and he pushed his Hellcat over. The dive left both the enemy and his wingman behind, and Carr now climbed back into the battle alone. As he climbed he picked off another fighter-bomber with a short burst to the engine and wing root. The plane exploded. Carr’s fourth and fifth victories were a pair of fighter-bombers he picked out 2,000 feet above him and paralleling his course. He pulled up on the right-hand Zeke and set its port wing on fire. Something left this plane which may have been the pilot, but Carr was too busy skidding onto the tail of the other plane to take much notice. Carr set this plane afire just aft of the engine and it started down. He split-essed to catch it, but it blew up before he could fire again. As he pulled out, he saw the first Zeke splash. No more enemy planes were visible as he climbed back up, so he headed for the Essex. On the way he tried to count the oil slicks and splashes in the water but stopped after seventeen. This first onslaught by the Essex pilots had been devastating. Twenty enemy planes were claimed and the slaughter was only beginning.

Shortly after Commander Brewer led VF-15 into the Japanese planes, more Hellcats waded into the fight. From the Cowpens came eight Fighting 25 F6Fs; a number of fighters from the Hornet, Princeton, Cabot, and Monterey followed, plus a few eager beavers from other flattops. The Cabot and Monterey pilots piled into the battle with vigor and claimed twenty-six more Japanese planes between themselves. The VF-31 pilots were especially effective, with five of the “Flying Meataxers” cleaving fifteen planes from the enemy formations. Lieutenant J. S. Stewart splashed three Zekes, as did Lieutenants (jg) F. R. Hayde and A. R. Hawkins, but the top scorer for the squadron was Lieutenant (jg) J. L. Wirth, with four planes.

As the Monterey fliers closed the attackers, a number of aircraft could be seen falling in flames. The VF-28 pilots added to the number in the next few minutes. Lieutenant D. C. Clements hit one Zeke with a high-speed pass from astern and the plane went down burning. As Clements rolled out, he saw two Zekes at his nine o’clock position. He tried a 90-degree deflection shot at one but missed. The Zeke began a climbing slow roll. Clements followed him through, snapping short bursts throughout the roll. As the Zeke dished out, it burst into flames. Clements next took out after another fighter which led him through some violent maneuvers followed by a 7,000-foot dive. He had been getting hits in the cockpit and engine area, but the Zeke would not burn. Finally, he rolled over the Zeke and saw the pilot slumped over the stick. The plane then slammed into the water. Clements next met another Zeke in a head-on pass, but with only one gun working, could do little damage. Finding his adversary a little too tenacious, he called for help and his wingman blew the Zeke off his tail.

Fighting 28’s high scorer was Lieutenant O. C. Bailey with four fighters. Bailey got his first Zeke with a full deflection shot from astern, and the plane left a corkscrew trail of smoke as it spun into the water. While attacking another fighter, Bailey overshot his intended target, but the enemy pilot turned toward Bailey’s wingman, Ensign A. C. Persson, who got him with a 45-degree attack from the rear. Another Zeke was seen low to starboard and the two Americans dove to the attack. The Zeke pilot tried to outscissor him, but Bailey got on the fighter’s tail and flamed it. The pilot bailed out.

By now no more enemy planes were evident and Bailey and Persson turned back toward the task force. As they neared TG 58.7, they were fired on by “friendly” ships and Persson’s F6F was hit. His left wing was badly damaged and his radio knocked out. Bailey shepherded his wingman back to the Monterey where Persson made a no-flap landing. Though the landing was good, the plane had been so damaged by the antiaircraft fire that it was unceremoniously stripped of all usable items and shoved overboard.

After seeing Persson safely home, Bailey headed back to where the action was. Flying at 20,000 feet, he saw a pair of Zekes about 4,000 feet below him. He rolled over and came in from astern. Bailey began firing at 400 yards at the trailing Zeke and continued until about 250 yards away. At this point the fighter burst into flames, flopped over on its back and went straight in. Bailey recovered underneath the other Zeke, pulled up and raked the plane with a burst. The Zeke dived away but after a short chase, Bailey nailed his fourth plane.

Commander William A. Dean, of the Hornet’s VF-2, saw twenty to twenty-five parachutes and “several dye markers in the water” during the course of the battle. The eight Hornet pilots claimed twelve enemy aircraft. Lieutenant (jg) Daniel A. Carmichael, Jr. led the Fighting 2 pilots with two Jills and a Zeke. A significant observation was made by Lieutenant (jg) John T. Wolf during a pass on a Zeke. With only one gun working and low on ammunition, Wolf scared one of the enemy pilots into dropping his belly tank and “what appeared to be a bomb.” During his debriefing Wolf told his intelligence officer about the incident and the I.O., correctly assessing the report, underscored Wolfs remarks when passing the word along. For the next few hours the American fliers would be considering Zekes as possible threats to the ships, not just in fighter combat.17

The eight Cowpens pilots came into the attack at 20,000 feet and only about 20 miles from the task force. The Americans knocked down five Jills and four Zekes, but it cost them. Lieutenant (jg) Frederick R. Stieglitz was heard over the radio to say “scratch one fish” and was last seen in the air giving hand signals to indicate that he shot down two planes, but he never returned to the “Mighty Moo” to confirm his score. Ensign George A. Massenburg was plagued by a “rough” engine and was pursued for a time by a Zeke, but a fellow pilot chased the enemy plane away. However, Massenburg’s engine finally seized and he had to set down in the water. Though he was seen to get into his life raft, he was not recovered.

In spite of the vicious onslaughts by the defending fighters, about forty of the Japanese planes broke through. Their formation had been cut up, however, and the survivors pressed on in small gaggles. Once again they were met by Hellcats, and once again smoke trails smudged the sky. Six pilots of the San Jacinto’s VF-51 found ten of the enemy fighting it out with about thirty U.S. planes several miles west of the task force. They shouldered their way into the brawl and claimed six enemy aircraft.

By this time the remaining Japanese planes were drawing close to the battleships of TG 58.7. Aboard the Stockham the sailors watched the enemy planes dropping out of the sky “like plums.”18 A few of the enemy fliers were also watching the Stockham, and they attacked the ship and the other “tin cans” of DesDiv 106. (The destroyers probably looked like easier targets than the bristling battlewagons.) These attacks, however, were no more successful than most for the day, and the destroyers escaped unscathed.

In a last-gasp effort, several planes broke through to attack the battleships. At 1048 the ships of TG 58.7 began firing. Gunfire from the Indiana tore the wing off a plane attacking her, and it crashed just 200 yards ahead of the battleship. Another plane went after the South Dakota and scored the only bomb hit of the day on a U.S. ship at 1049. Twenty-seven men were killed and twenty-four wounded, but the explosion didn’t slow the tough battleship even one knot. The South Dakota gunners claimed their attacker, but their fellow gunners on the Alabama (steaming close by) said the plane got away.

Two more Japanese planes glided in on the Minneapolis from astern. One of them dropped a 500-pound bomb that landed only a few feet off the ship’s starboard side. Several gas, oil, and water lines were ruptured and a small fire started. Three seamen were injured. One of the planes was shot down and the other retired from the area in obvious difficulty. Another dive bomber attacked the Wichita but only got two near-misses before it was shot down. Forty-millimeter fire from the Indiana punctured a smoke generator on the San Francisco, causing the ship to lay down a large trail of smoke. It was some time before her crew was able to jettison the generator.

By 1057 the hard-working fighter director Eggert could report that the radar screens were clear. Raid I was over. Only eight fighters, thirteen fighter-bombers, and six Jills were able to return to their carriers. Though antiaircraft fire had knocked down some of the attackers, it had been the fighters that had done most of the damage. At one point during the action Admiral Reeves had even signaled his ships, “Try to avoid shooting down our own planes. They are our best protection.”19

The American losses, though light in comparison to those suffered by the Japanese, were nevertheless tragic to the men of TF 58. Besides the twenty-seven men killed on the South Dakota, four pilots were listed as missing in action, including the Princeton’s air group skipper, Lieutenant Commander Ernest W. Wood. A number of Hellcats had been shot up and several had to be pushed over the side.

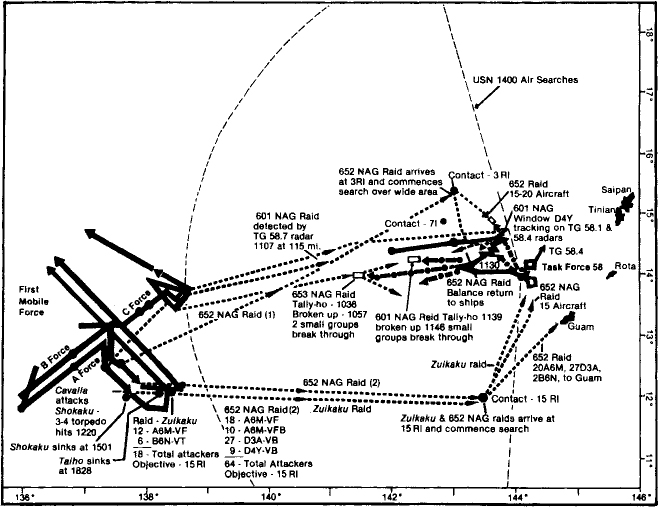

Another Japanese plane goes down under the fire of the TF 58 ships.

During the respite, TF 58 was landing, servicing, and rearming as many fighters as it could. Most of the bombers and torpedo planes were still orbiting to the east, waiting for some word on what to do. Admiral Reeves had an idea. At 1103 he asked Mitscher, “Desire issue following instructions my airborne deckloads before fuel depletion: Enterprise VT search ten-degree sectors to 250 miles median line 260 true. Attack groups follow along median line thirty miles behind. Search planes retire on contact, concentrate and attack in coordination other planes.20

“Approved, approved. Wish we could go with you,” Mitscher replied.21 But Reeves’s plan was stillborn, as it proved impossible to break through the confusion on the radio channels to issue the necessary orders. The bombers continued their merry-go-rounds to the east.

A Hellcat lands on the Lexington to rearm during the 19 June 1944 air battle. (National Archives)

Though he was willing to release some of his planes to go after the enemy, Mitscher was expecting more attacks; and he would not be disappointed. Just ten minutes after reporting his screens clear, Eggert had picked up another bogey on the Lexington’s radar at the incredible distance of 160 miles, bearing 250 degrees from the ship. This was Ozawa’s big punch from the Shokaku, Zuikaku, and Taiho.

This raid by the 601st Air Group was cursed by bad luck from the beginning. As the Taiho was launching her planes, Commander James W. Blanchard was at the periscope of the Albacore watching the activity. Blanchard had been patrolling the southwest corner of the new square Admiral Lockwood had set up when Ozawa’s own A Force stumbled across the sub’s path.

Blanchard submerged and watched the targets steam past. The Albacore’s position was about 12 20’N, 137 00’E. A large carrier, a cruiser and several other ships could be seen seven miles away, 70 degrees off the port bow. Blanchard brought his crew to battle stations. The submarine built up speed and closed the enemy. As Blanchard watched a second carrier was seen. Although he did not know it, the large eight-rayed flag he could see flying from this carrier was Ozawa’s own flag. Unlucky Taiho. She was in a better position for an attack than the flattop Blanchard had originally seen.

Blanchard had a beautiful setup for a right-angle shot at the Taiho. The big carrier was 9,000 yards away and the torpedo run would be 2,300 yards. Just then a destroyer got in the way, and Blanchard decided to close in for a torpedo run of under 2,000 yards. He took another quick look. It appeared to be a perfect setup for a spread of six “fish.” Then his luck changed. After all the information was fed into the Albacore’s torpedo data computer, the TDC refused to come up with a solution. Wrong information had been fed into it and it would not supply an answer.

Blanchard was beside himself. The Taiho was making 27 knots and the range would soon start to open rapidly. He decided to shoot a spread of six torpedoes by eye and hope for the best. At 0909:32 the torpedoes were sent on their way. A minute later, Blanchard noted three pugnacious-looking destroyers headed his way, so he went deep.22

Warrant Officer Sakio Komatsu had just lifted his Jill off the Taiho’s armored deck when saw one of the Albacore’s torpedoes bubbling toward the ship. Without hesitation he wheeled his plane around and dove it into the torpedo. A geyser of water, smoke, and debris marked his passing. It was a brave, but ultimately futile effort. Two minutes after it had been fired another torpedo slammed into the Taiho’s hull.23

This torpedo, the only one to hit, struck the Taiho’s starboard side near the forward gasoline tanks. The ship’s forward elevator jammed and gasoline and oil lines ruptured. But the carrier’s speed slackened only one knot and no fires broke out. To the ship’s damage-control officer the damage was only minor and repairs would quickly be accomplished. The Taiho raced on. The Albacore underwent a rather unenthusiastic depth-charging, and afterwards Blanchard would only claim possible damage to the carrier. It would be months before the truth would be learned.

Unaware of what was going on below, Lieutenant Commander Tarui led his planes toward TF 58. Eight soon dropped out because of various mechanical problems and returned to their carriers. Tarui then made the mistake of leading his planes over C Force. The ships’ gunners were trigger-happy and, on the bizarre reasoning that enemy planes would appear at high altitude and from the west—not the east—they opened fire. Two planes were shot down and eight others damaged badly enough to have to turn back.24 It must have been a disconcerting experience for the young Japanese crews to undergo this completely surprising encounter before getting anywhere near the enemy.

Lieutenant Commander Tarui regrouped his force and they plunged ahead. Shortly after 1100 they were close to TF 58. Tarui now made the same error his predecessor had made on Raid I—he began to brief his inexperienced crews on their part in the attack. Naturally this took time, and the Japanese planes circled and crossed over each other as the briefing went on. And Lieutenant (jg) Sims was again near the radio listening to Tarui’s instructions and passing them on to Eggert. Once more a pause by the enemy had enabled the Americans to climb above the attackers and to fly far enough west so that the enemy would be under constant air attack before getting anywhere near the U.S. ships.

Ten Essex Hellcats, led by the air group skipper, Commander David McCampbell, were waiting at 25,000 feet when they received instructions to intercept the enemy. The pilots poured the coal to their fighters and took out after the bogeys. At 1139 McCampbell spotted Raid II. It appeared there were about fifty Zekes and Judys. (Actually there were almost twice as many.) The Japanese planes, now about 45 miles from the task force, looked like they were in one big formation of three-plane sections and nine-plane divisions and were stacked about 1,500 feet deep. At the time of the sighting, the Hellcats had almost a 5,000-foot altitude advantage.

Leaving four planes as high cover, McCampbell took the rest down for a fast pass from the side. McCampbell’s first target was a Judy on the left side of the formation about halfway back. He had intended to cut his victim out of the pack, dive below him and continue under the enemy formation to the other side. However, McCampbell’s plans changed abruptly when his ‘fifties blew the Judy up in his face. McCampbell pulled up and charged across the formation “feeling as though every rear gunner had his fire directed at (him).”25

On the other side he picked off another Judy which burned and fell out of control. Working toward the front of the formation, McCampbell claimed a probable on a Judy that fell away smoking. He was now in position to attack the formation leader and his two wingmen. As he jockeyed for position on the leader, McCampbell noticed that what he had thought to be one large formation was actually two; one group was 600 feet lower and about 1,000 yards off to the side. His first pass on the leading plane seemed to have no effect. Breaking down and to the left, McCampbell swung around for another pass. This time he attacked the leader’s left wingman from 7 o’clock above. The Judy exploded in a ball of fire.

McCampbell again broke down and to the left which placed him to the left and below the leading Judy. He pumped a continuous stream of bullets into the Judy until it “burned furiously and spiralled downward out of control.”26 By this time the guns of his fighter were suffering stoppages and McCampbell pulled away to recharge them. He then returned to the battle. The Japanese formation had been hacked to pieces, but the remaining enemy pilots doggedly pressed ahead. Another Judy, apparently the leader of the lower formation, came into view. McCampbell immediately began a high-side run on him. Only the Hellcat’s starboard guns fired and McCampbell was thrown into a wild skid. The Judy took advantage of this unplanned maneuver and began a fast dive. McCampbell took up the chase, firing short bursts with his operative guns. Finally the impact of the ‘fifties took effect. The Judy pulled up and over and dove into the sea.

The fighting during the “Turkey Shoot” was not all one-sided. Here an Essex flier is helped from his Hellcat after being wounded during the battle. (U.S. Navy)

McCampbell was now out of action and returned to the Essex. Destined to become the Navy’s leading ace of the war with thirty-four aerial victories and a number of ground kills, he had shot down five Judys and claimed one probable in this one action. During the fight he noted that the enemy fliers took very little evasive action when they were attacked, except for some violent fishtailing which only slowed their planes down.

The rest of the VF-15 pilots claimed fifteen and one-half Zekes and Judys. (One pilot shared a Zeke with a pilot from another squadron.) While most of the Japanese planes were dispatched rather easily, some of the Essex fliers found the enemy could fight back. Ensign G.H. Rader did not return from the battle and Ensign J. W. Power, Jr., was wounded by a Zeke pilot whose plane he destroyed. Ensign C.W. Plant had knocked down four Zekes, but his next encounter was not too pleasant. While chasing a Zeke, Plant had another fighter lock onto his tail. Unable to shake the Zeke, he could hear the 20-mm and 7.7-mm shells “splattering off the armor plate.”27 Another F6F came by, finally, and shot the Zeke off his tail. When Plant got back to the Essex, 150 bullet holes (including one in each prop blade) were counted in his fighter. Another Fighting 15 pilot reported a “not unpleasant” experience when the container for his plane’s water injection fluid broke, filling the cockpit with alcohol fumes.28

For six minutes VF-15 had the Japanese all to themselves. Then the hapless enemy fliers were pounded from all sides by newly arriving Hellcats. Fighters from most of the carriers piled into the confusing melee. One of the pilots just entering the battle was Lieutenant (jg) Alexander Vraciu, who already had thirteen victory flags painted on his Hellcat. Six more would be added at the end of the day.

Vraciu’s first kill was a Judy that he exploded from only about 200 feet away. Two more Judys were then seen. Vraciu eased his fighter in behind the two planes and began to fire. His fire was returned by the rear gunner of the right-hand Judy. But the power of the six machine guns in the Hellcat’s wings proved too much. The dive bomber belched a puff of smoke, immediately followed by a continuous stream of black smoke. The plane began its final dive. The rear gunner continued firing until his plane sliced into the water.

Vraciu was quickly onto the other Judy. Several short bursts produced the desired results. Fire and smoke suddenly appeared and the Judy fell out of control. Vraciu had shot down three enemy planes in almost as many minutes. The mass of planes made him apprehensive, however; it seemed there were too many attackers for the defending fighters to handle. A fourth Judy pulled slightly out of formation and Vraciu plunged back into the fight. From dead astern he fired a long burst. The dive bomber burst into flames and fell awkwardly out of the sky.

He gave a quick glance to the tumbling Judy, but was more interested in a trio of dive bombers rapidly approaching their pushover points. With the engine of his F6F straining, Vraciu crept up on the trailing Judy. Flak bursts were beginning to blacken the sky, but Vraciu kept after his quarry. Finally he was within range and squeezed the trigger. The stream of shells literally disintegrated his target.

Vraciu did not waste time admiring his handiwork. The other Judys were now in their dives. He screamed down after the leading plane. Black puffs speckled the sky around him as he closed his target. When he got close enough he began to fire. For a few seconds nothing seemed to be happening and then—a bright flash! The Judy vanished, apparently undone by the explosion of its bomb.

Lieutenant (jg) Alex Vraciu happily signals his score for the interception.

Vraciu looked around. The enemy formation was gone; wiped out by the constantly attacking Hellcats and the deadly flak. He headed back to the Lexington, detouring around some “friendly” flak on the way, and was soon aboard his carrier. As he taxied up the deck, he looked up at the bridge. Admiral Mitscher was looking down at him. Grinning, Vraciu held up six fingers. As he climbed out of his cockpit after parking, Vraciu was greeted by a flock of well-wishers, including Mitscher. After the congratulations were over, Mitscher asked a photographer to take a picture of Vraciu and himself, “not for publication, to keep for myself.”29

The VF-16 pilots had good shooting, claiming four Jills, nine Judys, two Kates, and seven Zekes without loss. Before the day was over they claimed twenty-two more planes downed, with only one plane lost in an operational ditching.

As the battle swirled overhead, Admiral Reeves recommended to Mitscher that TF 58 head west “turning into the wind only as necessary to land aircraft or takeoff.” Mitscher approved this suggestion, and at 1134 told his task group commanders to “make as little to the easterly as practicable but land planes at discretion.”30

The Essex and Lexington fliers were not the only ones to be scoring against the enemy planes. Lieutenant Commander R.W. Hoel led twelve Bunker Hill fighters into the action around 1130. Unfortunately, most of the VF-8 fighters were unable to intercept the attack. However, Hoel was able to lead his division into a group of twelve Zekes that had so far escaped attack. He shot down one fighter immediately and almost got another.

Hoel next made an attack on a Judy which spiraled into the water. A Zeke tried to break up his attack, peppering Hoel’s Hellcat with 20-mm and 7.7-mm shells that caused his own guns to go into automatic fire and burn themselves out. Though his wingman finally chased the Zeke away, Hoel’s plane was in bad shape. Hoel tried to make it back to the Bunker Hill, but at 4,000 feet the stick slammed all the way forward and his Hellcat went into an inverted spin. Hoel bailed out, receiving two fractured ribs in the process, and was shortly picked up by a destroyer.

The VF-8 pilots had not had a good interception, claiming only four Zekes and a Judy, but that was still five less planes to worry about later. The pilots told their debriefing officers, “No new information. Zekes continue to burn.”31

Pilots of the Bataan’s VF-50 had better luck in their interception, claiming five Zekes, four Judys, and a Jill plus two others as probables. Lieutenant (jg) P.C. Thomas, Jr., chased a Zeke for some time before dunking him. The enemy pilot was very good, staying below 1,000 feet and timing his evasive maneuvers expertly. “It was like catching a flea on a hot griddle.”32 Unfortunately for the enemy pilot, he was boxed in by five F6Fs and was committed to a reasonably straight course. Finally the Zeke pilot stayed in one place too long and Thomas’s shells exploded his plane.

As he turned for home, Thomas saw another Zeke putting on an “amazing exhibition” of aerobatics for four other Hellcats. “At about 300 feet he started slow rolling and completed some fifteen in succession. He would dive to about 50 feet and then jink up and down between there and a matter of five to ten feet above the waves. Probably he hoped to entice some F6 into following his maneuver and mushing into the water. Several times he pulled into a half loop, flew on his back for a few seconds fishtailing, and then pulled up in an outside loop. Finally he completed a full loop under 500 feet and was caught by a burst that flamed him as he started to level out.”33

Ensign E. R. Tarleton had already downed a Judy when he spotted a Jill being stalked by another Hellcat. The American was out of range, but the Jill’s rear gunner kept firing a few short bursts at him. With the attention of the enemy crew on the other F6F, Tarleton was able to sneak in from 8 o’clock and explode the plane. As he pulled up Tarleton saw the other Hellcat, its prop windmilling, crash into the water. The pilot never got out of his sinking plane.

Planes from the two light carriers in TG 58.2, the Monterey and Cabot, were also active against the Japanese attackers in Raid II. In a series of battles ranging from 23,000 feet down to below 10,000 feet the Monterey pilots claimed six Jills and a Zeke, and the Cabot fliers scored with four Zekes and a Judy plus two Zekes damaged. One of the Fighting 28 Hellcats was hit by “friendly” flak, but the pilot nursed his plane back to the Monterey, where it was stripped then pushed overboard.

Yorktown planes also gave the Japanese troubles. Before the day was over, the VF-1 fliers would claim thirty-four fighters and three bombers downed and five other planes as probables. Four more enemy aircraft were destroyed on the ground at Guam. Commander “Smoke” Strean led ten Hellcats into the battle at 24,000 feet. About 60 miles from the Yorktown the fliers encountered about fifty planes 4,000 feet lower, with an equal number of enemy planes at about 14,000 feet. As the lower group was already being set upon, Strean led his planes against the top cover. Strean and his wingman had good results, each picking off a Zeke and a “Tony.” (More likely a Judy. The Yorktown pilots consistently reported Tonys during the day.)

The fight was now becoming more and more furious and confused, with battles from above 20,000 feet down to sea level. Lieutenant R. T. Eastmond knocked off one Zeke. As he pulled out, he counted seventeen aircraft falling out of the sky in flames. Eastmond saw another Zeke nearby and walked a burst across the enemy’s cockpit. The Zeke suddenly spun, almost hitting Eastmond, and smashed into the water. Eastmond next saw a Zeke closing on an F6F. With his wingman he dove to the attack but was unable to close fast enough before the Zeke had sent the Hellcat into the sea. The Zeke got out of the area untouched.

A VF-1 Hellcat is signaled off from the Yorktown on 19 June 1944 on an intercept mission. The target information is given the pilot via the blackboard. Note the “Top Hatter” insignia on the aircraft. (U.S. Navy)

Lieutenant (jg) C. H. Ambellan had already exploded two fighters when he saw a third diving toward the task force. He took up the chase down to sea level but was unable to get in a good shot at the wildly maneuvering Zeke. Finally only one gun was firing. By kicking the hydraulic chargers, he got his three starboard guns to fire. They were enough. The Zeke broke into flames, disappearing in “one big orange puff” when it hit the water.34 Ensign C. R. Garman had entered the fight with Ambellan but was not seen after the first pass and never returned to the Yorktown.

The Fighting 1 pilots were not finished tearing into the enemy aircraft. Lieutenant R. H. Shireman, Jr., led his division down from 20,000 feet into a mass dogfight at 10,000—13,000 feet. Shireman peppered a Zeke during a stern run, but his speed was so great he overshot his target. It did not matter. His victim was in an inverted spin and never pulled out. Lieutenant (jg) G. W. Staeheli sighted a Judy diving on a destroyer from 5,000 feet. He was able to blow the Judy’s cowling off. The plane rolled over on its back and fell into the water.

The other two members of Shireman’s division scored also. Lieutenant (jg) W. P. Tukey had already downed one Zeke when he caught another at 15,000 feet. This Zeke dove into the sea, leaving a large green stain spreading slowly over the sea. Ensign R. W. Matz met a Judy head on. His six ‘fifties were too much for the dive bomber, which burst into a solid sheet of flame. Matz’s canopy was partially open and when the Judy passed overhead he could feel the heat. Matz wound up the battle with another Zeke and two probables.

Although Commander McCampbell had believed that the Japanese planes would not break through the Hellcats, about twenty succeeded in breaching this defensive wall. The Stockham, still on picket duty in front of TG 58.7, had her hands full during a hectic twenty minute period as enemy planes came at her from every direction. She was not damaged by these attacks and shot down three of her attackers. Two more were claimed as probables. During these attacks the men on the Stockham watched as the “battleships, cruisers, and destroyers . . . put up a tremendous barrage which, together with the burning planes all around the horizon, created a most awesome spectacle.”35

Many of the planes that broke through were knocked down by ship’s fire, but some fell to the fighters. Lieutenant William B. Lamb from the Princeton’s VF-27 found himself in the company of twelve Jills with only one of his six guns working. (As can be seen, the failure of several guns was not uncommon to U.S. fighters on this day.) For a time he flew formation with the Jills, staying just out of range of their fire. After radioing their course and altitude to the ships, Lamb waded into the enemy and destroyed three of them with his one gun.

Four pilots of the Enterprise’s VF-10 “Grim Reapers” worked their way into the enemy planes nearing the ships. Lieutenant Donald Gordon and Lieutenant (jg) Richard W. Mason caught a Judy pushing over into its dive on a battleship. One pass by each pilot was all it took to ensure the Judy would never pull out of its dive. Less than a minute later Gordon and Mason saw another Judy low on the water. Both pilots later told their debriefing officer that they saw the Judy drop a torpedo. (Since a Judy was a dive bomber, it is doubtful this particular plane was carrying a torpedo.) The Judy flamed briefly as Gordon fired into it, then torched completely and crashed following Mason’s pass.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Marion O. Marks and Ensign Charles D. Farmer saw two Jills in their torpedo runs against the battleships. Marks latched onto one Jill, but was unable to bring it down on his pass. Farmer then took over, firing two long bursts from dead astern. The torpedo plane vanished in a violent explosion. The other Jill was not seen again.

From 1150 until about 1215 the battleship of TG 58.7 came under attack by dive and torpedo bombers. Two Jills thought the South Dakota looked like a juicy target but were chased off by antiaircraft fire from the Alabama. While the Alabama gunners were concentrating on the Jills, a Judy sneaked in on the battleship and dropped two small bombs which missed and caused no damage. The Indiana, in the meantime, was doing her share by shooting down five enemy planes and evading their attacks. One torpedo launched at the speeding ship mysteriously exploded only fifty yards from her. At 1214 another Jill attacked the Indiana from the “starboard side flying very low. It had no torpedo. . . . About 100 yards off it caught fire, swerved upward a short distance, and then glided down striking the ship at the waterline. . . . The plane bounced off the ship and immediately sank, leaving (a) swirl.”36 The Indiana rushed on with only minor damage. The Iowa was also attacked by a Jill, but its torpedo scored a clean miss.

A geyser of smoke and spray erupts from the premature explosion of a torpedo aimed at the Indiana. The attacking plane also goes down in flames. Photo taken from the Wichita. (National Archives)

Aboard the nearby cruiser San Francisco the ship’s Automatic Weapons Officer received a superficial wound on a finger during the action, probably from friendly 40-mm fire. “To encourage his gun crews to greater effort he held up his bleeding finger and shouted, ‘The bastards have drawn blood, shoot them down!’”37

Around noon enemy planes gave Admiral Reeves’s TG 58.3 some exciting moments. A Judy and three Jills zeroed in on the Enterprise and Princeton, the latter steaming about 2,000 yards off the Enterprise’s starboard beam. Though the planes had been detected by radar, lookouts did not pick them up until they were only 6,000 yards away. The Judy was the first to attack, dropping down on the “Big E” in a shallow dive. Taken immediately under fire, the plane bored in to drop its bomb about 750 yards off the carrier’s starboard quarter. Hit repeatedly by fire from many ships, the Judy wobbled away to crash about 4,000 yards ahead.

As the dive bomber crashed, the first Jill darted in aiming at the Princeton. Before the Jill was able to drop its torpedo it was shot down by the light carrier. The second Jill was also splashed by the combined gunfire of the carriers and their screen. The last Jill was aiming at the Enterprise and was able to drop its torpedo before its right wing was blown off (apparently by 5-inch fire from the Enterprise). The torpedo exploded in the carrier’s wake. The Jill went into a spin, then plunged vertically into the sea 300 yards from the Princeton.

Holding down the southern end of TF 58’s formation was Admiral Montgomery’s TG 58.2. About 1145 lookouts on the Wasp spotted two planes 20,000 yards distant. They were thought to be “unfriendly” but there was no positive identification. The forward lookouts tracked the planes until they disappeared behind the ship’s island and into some clouds. The aft lookouts were ordered to pick up the planes, which were now reported as “friendly,” and keep an eye on them. Suddenly, one of these “friendlies” turned and made for the Wasp. The plane, now identified as a Judy, came in fast from the starboard quarter. The Wasp’s 40-mm and 20-mm guns were on it quickly, but the plane was able to drop its bomb. The 550-pound bomb landed just off the carrier’s port beam, spraying the ship with shrapnel. One sailor was killed instantly by a fragment and several others wounded. The Judy, smoking and in apparent difficulty, finally crashed about 12,000 yards ahead of the ship.

The Bunker Hill was also undergoing her share of harassment. At 1203, lookouts on the carriers sighted two Judys emerging from a cloud at 12,000 feet and only four miles away. The planes were just pushing over into their dives. Though the forward 5-inch mounts could not bear, eight other 5-inch guns were immediately firing, along with seven 40-mm quad mounts and fifty-three 20-mm guns.

The Bunker Hill has a close one. What appears to be the aft half of a Judy can be seen at the middle left. (National Archives)

Hits were made on the two planes almost immediately, but one pressed home his attack. The other Judy pilot apparently disliked the heavy fire and started to turn toward the Cabot. A direct hit blew it in half, with its nose landing off the Bunker Hill’s starboard bow and its tail off the stern. The pilot was thrown from his plane, his parachute opening. The other attacker was able to drop his bomb before his aircraft was hit. Both bomb and plane landed close aboard the carrier’s port elevator. The near-miss was surprisingly effective—two men killed and seventy-two wounded, the port elevator knocked out, fires in Ready Rooms 1 and 2, several fuel tanks and vents ruptured, and numerous small holes in the side of the ship. The Bunker Hill shook off these wounds, however, and remained in the battle.

By 1215 the task force radars were again clear of bogeys. The enemy had been dealt another savage blow. Of the 128 planes that had been launched in this raid, only 31 (16 Zekes, 11 Judys, and 4 Jills) returned. To the west of the task force, many fires still burned and many oil slicks fouled the water.

Miles away, Admiral Ozawa was unaware of the disaster that had befallen his first two attack waves. Even if he had known of the losses to his air groups there was little he could have done. And he was struggling with other problems. Around 1100 his force had been spotted by a Manus-based PB4Y.38 Then he had run afoul of American submarines and was suddenly minus two carriers!

Crewmen aboard the Lexington catch a few minutes’ sleep on the hangar deck during a lull in the action.

After the Taiho had been hit by the one torpedo from the Albacore’s tubes, she continued on without slackening speed. To her crew the damage was trifling. After all, wasn’t this brand-new vessel virtually “unsinkable”? Air operations continued as the Taiho steamed at 26 knots. But now she was a time bomb waiting for the moment to go off.

Clumsy attempts to repair ruptured fuel and oil lines and to pump overboard the fuel in damaged tanks had been made by the ship’s damage control parties. Large quantities of gas were spilled on the hangar deck as it was being pumped over the side. Then, an inexperienced damage control officer made a disastrous decision. In an effort to dissipate the fumes seeping from the tanks, he ordered the ventilating ducts opened. The effect was just the opposite of what he had planned; it only spread the volatile Tarakan petroleum fumes, and the equally dangerous avgas fumes, throughout the ship.

As the Taiho plowed ahead, her crew unmindful of the disaster to come, another of Ozawa’s carriers suffered a fatal blow. Ozawa’s A Force was about sixty miles away from the Albacore’s point of attack when it had the misfortune to stumble across another U.S. submarine, the Cavalla. Commander Kossler had followed Admiral Lockwood’s order to trail the Mobile Fleet and now, many hours later, was ready for “a chance to get in an attack.”

At 1152 Kossler raised his periscope to take a look around. “The picture was too good to be true!” he later wrote.39 Off the Cavalla’s port bow was a large carrier and two cruisers. A destroyer, the Urakaze, was about 1,000 yards on the sub’s port beam. The carrier was the Shokaku and she was busy launching and recovering planes. Kossler took the Cavalla in closer to make sure the flattop was not a “friendly.”

Three times Kossler took a periscope sighting while the Urakaze steamed unsuspectingly close by. The Japanese screening forces, already weakened by their losses around Tawi Tawi, were now further hindered by their own lamentable showing in antisubmarine warfare. The Cavalla was able to get within the screen and make a good setup on the Shokaku. Kossler sneaked another peek at the carrier.

A big “Rising Sun” flag was visible. The Cavalla’s sailors readied their torpedoes. Kossler planned to fire six of them, figuring that at least four would hit. The first five torpedoes shot out of the tubes and streaked toward the Shokaku. Another quick glance was taken at the Urakaze. She was still apparently unconcerned with what was going on about her. Kossler fired his last torpedo as he took the Cavalla deep.40

As the Cavalla’s torpedoes bubbled past her, the Urakaze woke up and charged the sub. As he went deep, Kossler heard three solid hits, then the Urakaze and several other destroyers were upon him. Eight depth charges exploded fairly close to the Cavalla to start a three-hour working over of the sub. Over one hundred depth charges were eventually dropped, with at least fifty of them exploding very close. But the Japanese hunters didn’t stay with their attacks and let the Cavalla escape.

Although Kossler had heard only three explosions, four torpedoes had actually slammed into the Shokaku at 1220. The big carrier slowed and fell out of formation. Flames raged through the ship and explosions tore her apart. The Shokaku’s damage control personnel were better than the Taiho’s and got many of the fires under control, but they could not contain them all. And all the while, the deadly fumes from ruptured gas tanks, and tanks carrying the Tarakan petroleum, were seeping throughout the ship.

The Shokaku was doomed. Her bow settled lower and lower in the water. Finally the water began to pour into the ship through her open forward elevator. Shortly after 1500 the fires cooked off a magazine and this explosion, intensified by volatile fumes, ripped the carrier apart. What was left of her turned over and sank at 12°00′N, 137°46′E. The Shokaku took with her 1,263 officers and men (out of a complement of about 2,000) and nine aircraft.

A short distance away the crew of the Cavalla heard and felt the tremendous explosions and breaking up sounds of the dying carrier. Kossler later radioed Admiral Lockwood, “Believe that baby sank.”41 Lockwood radioed back, “Beautiful work Cavalla. One carrier down, eight more to go.”42

Also nearby was the Taiho. Her life was now being counted in minutes. Though Ozawa “radiated confidence and satisfaction,”43 and had launched planes for Raids III and IV, his confidence was misplaced. Just one half-hour after the Shokaku had exploded, the Taiho’s turn came. At 1532 a violent explosion shook her. Her armored flight deck split open and bulged up; the sides were blown out of the hangar deck; holes were torn in her hull bottom. Many of her crew were killed in this one monstrous blast. The Taiho began to settle. Ozawa wished to go down with his flagship but was finally dissuaded by his staff. A cruiser and a pair of destroyers were ordered to close for rescue attempts. Ozawa, his staff, and the Emperor’s portrait were taken by lifeboat to the destroyer Wakatsuki. From there they were transferred to the cruiser Haguro, arriving on that vessel around 1706. By this time the Taiho was a raging cauldron. No ship could get close enough for rescue work. At 1828 another thunderous explosion rocked her. She heeled to port, kept going over and then went down stern first. Her losses were great—1,650 men out of a crew of 2,150, plus thirteen planes.

Ozawa’s big problem now (besides the obvious and traumatic one caused by the loss of the two carriers) was communications. Although the Haguro was flagship of the 5th CruDiv, she was hardly equipped to handle the business of a Fleet flagship. Only the Zuikaku was properly equipped and she was not nearby at this time. To compound Ozawa’s problems, the only set of codes for direct communication with Combined Fleet had gone down with the Taiho. It was only after a code common to all flag officers was used that contact was restored.

The Japanese had continued aerial operations, even through the submarine attacks. Between 1000 and 1015 Admiral Joshima’s CarDiv 2 launched fifteen Zeke fighters, twenty-five Zeke fighter-bombers, and seven Jills of the 652nd Naval Air Group. These planes would make up what the Americans called Raid III.

These planes were heading for the “7I” contact when they were radioed new instructions at 1030. They were now to attack the enemy at position “3 Ri” which had been reported by a searcher at 1000. Plotted about fifty miles north of “7I”, the “3 Ri” target was actually located farther south. Unfortunately, only twenty planes received these instructions and headed for their new target. The rest of the formation kept on for “7I”. Upon reaching this position these planes found nothing. After searching vainly for some time, the enemy aircraft returned to their carriers.