As DUSK SETTLED over the Philippine Sea on 19 June, the air battles quickly tapered off and soon stopped. Aboard the American ships there was an air of jubilation. Pilots who had already landed waited for squadron mates to land, so as to swap stories. Sailors kept telling each other of the many Japanese planes they had seen diving into the ocean leaving greasy trails of smoke or the geysers of water thrown up by the few near-misses. From admiral to seaman, all hands were satisfied that the Japanese air units had suffered a shattering defeat.

What was less satisfying to Admiral Mitscher was TF 58’s position during the day. When Raid I had come in around 1000 Mitscher’s flagship the Lexington had been over 100 miles from Guam, but due to the constant launchings and recoveries throughout the day, the task force’s course had been east by south. By 1500 the Lexington was only twenty miles from Guam’s northwest tip.

At this time, however, Spruance ordered a change of course to the west, to close the Japanese fleet. But that was easier ordered than done. Mitscher first had to zigzag to the north and recover his aircraft. This took almost five hours. It would be 2000 before he could definitely head west.

About an hour after the Lexington had turned away from Guam, Spruance radioed Mitscher: “Desire to attack enemy tomorrow if we know his position with sufficient accuracy. If our patrol planes give us required information tonight no searches should be necessary. If not, we must continue searches tomorrow to ensure adequate protection for Saipan. Point Option should be advanced to the westward as much as air operations permit.”1

(Point Option is a moving point based on a carrier’s planned position for any given time. Therefore, theoretically, an aviator on a mission knows just where his carrier will be at a later time.)

At 2000 TF 58 took up a course of 270 degrees and all ships went to 20 knots. A half hour earlier Mitscher had detached Harrill’s TG 58.4. It was to remain behind off Guam. On the 17th, while the other groups had topped off their destroyers, Harrill had supposedly dallied. Now he thought his destroyers needed fuel. Harrill asked to be left behind while he fueled.2 Mitscher and Spruance conferred and decided TG 58.4 could cover Guam and Rota while the rest of TF 58 headed west. Though fifteen carriers used against an enemy force now woefully deficient in aircraft might seem to be a case of overkill, no one could foresee the outcome of the battle, and all the carriers might be needed. However, Harrill’s force was now a burden and would slow the chase of the enemy.

Though supposedly in a similar fuel predicament as Harrill, Jocko Clark radioed Mitscher, “Would greatly appreciate remaining with you. We have plenty of fuel.” Mitscher shot back, “You will remain with us all right until the battle is over.”3 Harrill’s days as a task group commander were numbered.

Task Group 58.4 spent the next two days keeping Guam and Rota under surveillance. On the 20th the Essex launched four night fighters at 0208 to harass the two islands. Nothing happened over Rota, but the two F6Fs assigned to Guam discovered Tiyan airstrip (near Agana) to be lighted. They promptly shot up the field and the lights went out. The Japanese were not to be deterred, and at 0410 they turned the lights back on and began sending planes into the air. Four planes got off the ground, but three were quickly sent tumbling back in flames by the waiting Hellcats.4

A dawn fighter sweep found little of interest on the two islands. Harrill’s group spent much of the day fueling from the Lackawanna and Ashtabula and receiving replacement aircraft from the escort carrier Breton. An afternoon sweep by twenty Essex planes encountered eight Zekes west of Orote Point. Ensign J. W. Power’s plane was bracketed by a pair of fighters, and he was last seen heading for a cloud with a Zeke close behind. One Zeke was shot down and another damaged. The rest of the Zekes contented themselves with staying in the clouds.

Two strikes and an intruder mission the next day encountered little more than the usual heavy antiaircraft fire. One SB2C was lost in an afternoon strike on antiaircraft positions on Marpi Point. Harrill’s force remained near Guam until the rest of TF 58 returned on the 23rd.

Meanwhile the remainder of TF 58 headed west. Enemy planes still pestered the task force. During the evening several small raids closed with TG 58.1 but did not get within gun range. Admiral Lee again had his battle line twenty-five miles ahead of TG 58.3. Mitscher and Spruance badly needed information on the Mobile Fleet’s whereabouts. All they had were the Albacore’s and Cavalla’s attack reports (the latter’s report having been received at 2132) and a PB4Y contact report made at 1120. Additionally, at 1957 Spruance received an HF/DF fix that put the enemy somewhere around 10°30’N, 136°30’E at 1800. By then the Japanese were moving far north of that fix.

A plan to send out a long-range search by night fighters and the Enterprise’s radar-equipped Avengers had been considered by Mitscher but rejected. He did not want to lose any more distance than absolutely necessary in this downwind chase; a launch now would lose some of that precious distance. Also, Mitscher (and a number of other top-ranking carrier officers of that time) had a deep-seated dislike of any form of night operations. A further consideration was that most of Mitscher’s night fighters had been used in the Turkey Shoot, while the torpedo pilots had spent several hours counting RPMs as they orbited outside the battle area. The crews needed sleep if they were to be in good shape for a battle the next day. Mitscher decided he would have to rely on PBM searches from Saipan.

At 2207 TF 58 changed course to 260 degrees and picked up speed to 23 knots, the best speed for economical fuel use. (The restrictive factor here was the destroyers. They were fuel-limited and a faster speed would cause them to burn too much of the precious stuff.) Shortly after 2300 the task force entered the area of the afternoon air battle, an’d several U.S. airmen were picked up. The speed and course of TF 58 had been planned to close the distance with the Mobile Fleet—but it did not. The Americans did not know exactly where Ozawa’s ships were, and were heading toward what they thought was the Japanese retirement track. Actually, Ozawa had already changed his course to the northwest and was beginning to open the distance.

For the Japanese, 19 June had not been a happy day. The loss of the Taiho and Shokaku was very apparent; the loss of so many aircraft was not yet so. A feeling of unease pervaded the Fleet, but the officers and men of the Mobile Fleet were not yet ready to give up.

Though only one hundred planes had returned to their ships, most of the Japanese commanders were still optimistic: Ozawa probably because he was isolated on the Haguro, the others because of the reports of the sinking of four carriers, the damaging of at least six others, and the shooting down of a fantastic number of the despised “Grummans.” Tokyo even got into the act when it broadcast that eleven American carriers and many other ships had been sunk! Some of this information had come from pilot’s reports, but much of it had been supplied by the incredibly sanguine Kakuta on Tinian. Why he would continue to send such patently false messages is still a mystery.

A and B Forces had changed course to the northwest at 1532 (just when the Taiho was being blown apart) to head for a rendezvous with C Force and the supply ships. Ozawa had arrived on the Haguro at 1706. It would not be until the next day, however, that he would learn just how many aircraft he had remaining. At 1900 Ozawa signaled his ships his intention to fuel the Mobile Fleet the next morning. This signal was followed shortly before midnight by another message ordering his ships to “proceed in a northwesterly direction and maneuver in such a way as to be able to receive supplies on the 21st.”5

In Tokyo Admiral Toyoda had been following the battle (as much as he could since communications were temporarily lost when the Taiho went down) and early on the 20th he radioed Ozawa, “It has been planned to direct a running battle after reorganizing our forces and in accordance with the battle conditions. (1) On the 21st, Mobile Fleet shall reorganize its strength and take on supplies. Disabled vessels shall proceed to the homeland. Also, part of the aircraft carriers shall proceed to the training base. [This was Lingga.] (2) On the 22nd, according to the situation, you shall advance and direct your attack against the enemy task force, cooperating with the land-based air units. After this has been done, you shall dispatch your air units to land bases. Thereafter, operations shall be carried on under the commander of the 5th Base Air Force. The aircraft carriers shall proceed to their training base. (3) After the 22nd, according to the conditions, you shall manage most of your craft in mopping up operations around Saipan.”6

At 0530 on the 20th, both sides began launching their first searches. Kurita’s C Force launched nine Jakes to search 300 miles between 040 and 140 degrees. These floatplanes were followed a little over an hour later by six Kates from Admiral Obayashi’s carriers, searching between 050 and 100 degrees. Neither group sighted any U.S. ships, though the Kates saw two enemy carrier planes at 0713. However, some of the searchers were seen by American pilots, for three Jakes and a Kate failed to return, victims of the Hellcats.

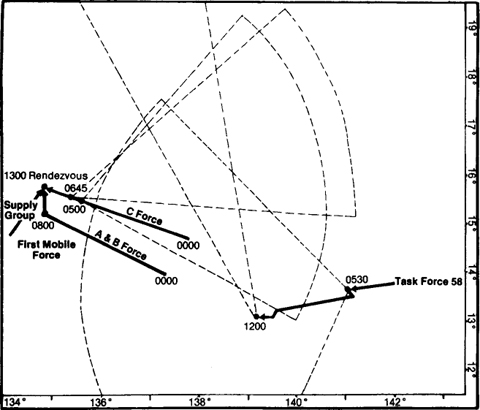

Movement of opposing forces 0000-1200, 20 June 1944.

When Kurita received the report of the sighting of U.S. planes, he wanted to retire west as quickly as possible. But Ozawa, when finally given the sightings after a long delay, was more confident. He thought the sightings were false. The Mobile Fleet would still refuel on the 20th and prepare for another battle the next day.

As the Japanese were launching their first search planes, Mitscher was sending his own planes out. Incredibly, this was still a routine effort. At this time, there seemed to be no thought of sending Avengers or Hellcats off on long-range missions. The planes flew their normal 325-mile search patterns. With no word on the position of the Japanese Fleet since the submarine attacks and the HF/DF fix, this was an amazingly short-sighted use of the planes.

The American planes went out to their limit, covering an area between 250 and 355 degrees. Only a few enemy aircraft were seen. The Enterprise’s air group commander, “Killer” Kane, picked off two of them. The first plane, a Jake, went down quickly. Forty minutes later a plane identified as a Jill, probably a Kate, was seen heading directly for the formation of two Avengers and the fighter. One turret gunner got off a few rounds before his guns jammed, then Kane took over. With a three-second burst Kane set the enemy’s belly tank on fire. The fire spread rapidly. The pilot pulled up to 700 feet, then dove for the water. At 200 feet he jumped from his plane, but his chute streamed. “Plane and pilot hit with a splash. The Jap’s body could be seen underwater with a pool of blood forming above.”7

Just some 50 to 75 miles farther west from the 325-mile limit were the Japanese ships. If Mitscher had sent his planes a bit farther the Japanese would have been seen and the dusk attack could have been avoided.

As the dawn search droned on without results, Spruance and Mitscher became increasingly concerned that the Japanese had escaped. Spruance signalled Mitscher, “Damaged Zuikaku may still be afloat. If so, believe she will be most likely heading northwest. Desire to push our searches today as far to westward as possible. If no contacts with enemy fleet result consider it indication fleet is withdrawing and further pursuit after today will be unprofitable. If you concur, retire tonight towards Saipan. Will order out tankers in vicinity Saipan. Zuikaku must be sunk if we can reach her.”8

“Zuikaku” was actually the now sunken Shokaku.

As noon approached Mitscher was listening to his Air Officer Gus Widhelm propose a special search-strike by Hellcats. Widhelm had estimated that the Japanese were probably headed northwest at 15 knots while covering the “Zuikaku.” His idea was to send twelve Hellcats, each carrying 500-pound bombs and belly tanks, out 475 miles to find the Japanese. These fighters would be escorted by eight other F6Fs. Mitscher reluctantly approved Widhelm’s plan.

At noon the twelve fighter-bombers, flown by volunteers and led by Air Group 16’s skipper, Commander Ernest M. Snowden, began rumbling down the Lexington’s deck. In the air they were joined by their escorts from the San Jacinto. All took up a heading of 340 degrees. After the fighters left, Mitscher brought TF 58 around from 261 degrees to a course of 330 degrees. At this time the task force was 315 miles west of Guam.

Once again the men of TF 58 settled down to wait.

Thirty minutes after the Hellcats had departed, the last ships of the Mobile Fleet reached the fueling rendezvous at 15°20’N, 134°40’E. The rendezvous could not be considered orderly or disciplined. In fact, it was a real mess. With Ozawa still unable fully to control his ships from the Haguro, the fleet milled around in a disorganized manner, making little headway in the important matter of fueling. Though the oilers had been in position and ready to deliver fuel since 0920, the combatant vessels had straggled in over the next few hours, and none had taken on fuel.

Aboard the Lexington Commander Ernest M. Snowden, Air Group 16’s skipper, reports about the unsuccessful search for the Japanese Fleet that was led by him. (U.S. Navy)

Tempers were short and the officers and men jumpy—afraid that U.S. planes would catch them during the vulnerable process of fueling. Ozawa finally ordered the fueling to begin at 1230, but this order was cancelled when a false sighting of enemy planes was reported. The Mobile Fleet continued to mark time as TF 58 gradually closed the distance.

At 1300 Admiral Ozawa was at last able to transfer to the Zuikaku. With communications now capable of handling the fleet staff, Ozawa finally learned how bad his losses had been the day before. But Ozawa, bolstered (and badly misled) by the disingenuous reports from Kakuta, was more than ready to carry the battle to the enemy the next day.

Also at 1300 the Chitose and Zuiho sent three Kates searching 300 miles to the east. One of these planes spotted two carriers and two battleships at 1715, but by the time the report reached Ozawa it was of no value. The Americans were already on their way.

At 1330 eight Avengers covered by four F6F’s took off from the Enterprise to search between 275 and 315 degrees out to the usual 325 miles. The Wasp also contributed two fighters and two Helldivers. Scouting between 295 and 305 degrees were Lieutenant Robert S. Nelson and Lieutenant (jg) James S. Moore in their Turkeys, escorted by Lieutenant (jg) William E. Velte, Jr.

Aboard the Lexington and the other ships of TF 58 the waiting for a report—any report—on the whereabouts of the Japanese was becoming oppressive. Captain Burke was stalking back and forth in the Lexington’s flag plot, cursing softly to himself. Gus Widhelm was ready to sell for fifty dollars his thousand-dollar bet that TF 58 planes would bomb the enemy fleet. It was obvious that Snowden’s fighters had not seen anything. The only hope of spotting the Japanese in time to launch a strike today now lay in the eight Avengers and two Helldivers.

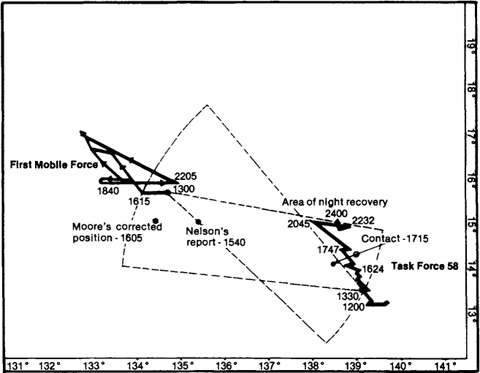

Movement of opposing forces 1200-2400, 20 June 1944.

Nelson’s little group had taken up a course of 297 degrees for the outbound leg. The trio cruised at 150 knots for best range and flew between 700 and 1,500 feet because of some high haze. An hour and a half after takeoff, Nelson saw an enemy plane but decided to let it go and keep searching. At 1538, when he was getting close to the end of his outbound leg, Nelson saw something slightly to his left and about 30 miles ahead. It was a ripple on the horizon. Nelson led his group into a nearby rain shower in order to close in unseen and climbed to 3,000 feet. Two minutes after he had seen the ripple, Nelson was able to view what no man in TF 58 had yet seen—the Japanese Mobile Fleet.

“Enemy fleet sighted, time 1540, Long. 135-25E., Lat. 15-00N., course 270° and speed 20 knots,” Nelson sent back to TF 58 by voice radio and morse code. “Two groups, one heading west and one heading east. Ten ships in northern group and twelve in southern. They seem to be fueling. Large CV in Northern Group.”9 The Enterprise fliers had seen Ozawa’s A Force, with the Zuikaku, the cruisers Myoko and Haguro, and seven destroyers. Nelson could not make out the southern group of ships (probably B Force) clearly, but thought it contained two or three carriers, some oilers, and the usual screen.

For thirty minutes more Nelson, Moore, and Velte shadowed the Mobile Fleet, sending out more reports. Their report sent at 1606 was a very important one. When doublechecking Nelson’s navigation plot, Moore found a longitudinal error. The new fix placed the Japanese ships 60 miles farther west at 15°35’N, 134°30’E. This was the correct position but placed the closest enemy vessels over 275 miles from TF 58. It was a long way to fly!

At 1610, when it appeared that several enemy planes were taking an interest in them, and the Zuikaku sent a burst of flak in their direction, the three fliers beat it for home. They had completed their job and done it well.

Meanwhile, another group of searchers had come upon the enemy ships at 1542. Ensign E.W. Laster was the first to see them. The three pilots watched the ships (apparently vessels of C Force) for a few minutes before turning for their carrier. A contact report was sent immediately, followed a short time later by the amplification, “Two groups, one group ten miles north of the other. 10-12 ships, one CV, four BB and six cruisers. 134-12E, 14-55N, course 000, speed 10 knots.”10

Even before these reports had reached him, Mitscher was signalling his ships, “Indication that our birdmen have sighted something big. Speed 23.”11 This was at 1518, and where he got this report is unknown. But finally, shortly after 1540 when Nelson’s message reached Mitscher, the gloom in the Lexington’s flag plot suddenly broke. The Japanese had been sighted for sure.

Nelson’s report had been garbled, however, and it took a few minutes to get confirmation of Nelson’s sighting from other ships that heard it. At 1548 Mitscher signalled his carriers to “Prepare to launch deckload strike”.12 On the Lexington the task force navigator had been plotting the enemy’s position. Incredulous whistles broke the air when he came up with the plot. It was a long way to fly!

Mitscher huddled with his staff, deciding if the distance was too far for his fliers. In a few moments the decision was made. They would go, but it would be close.13

No one knew better than Marc Mitscher that this attack was going to be risky. A man with great compassion for his fliers, he also knew that the job must be done. After the battle he said: “The decision to launch strikes was based on so damaging and slowing enemy carriers and other ships that our battle line could close during the night and at daylight sink all ships that our battle line could reach. . . . It was believed that this would be the one last time that the Japanese could be brought to grips and their navy destroyed once and for all. . . . Taking advantage of this opportunity to destroy the Japanese Fleet was going to cost us a great deal in planes and pilots because we were launching at the maximum range of our aircraft at such a time that it would be necessary to recover them after dark. This meant that all carriers would be recovering daylight-trained air groups at night, with consequent loss of some pilots who were not familiar with night landings and who would be fatigued at the end of an extremely hazardous and long mission. Night landings after an attack are slow at best. There are always stragglers who have had to fight their way out of the enemy disposition, whose planes are damaged, or who get lost. It was estimated that it would require about four hours to recover planes, during which time the Carrier Task Groups would have to steam upwind or on an easterly course. This course would take us away from the position of the enemy at a high rate. It was realized also that this was a single-shot venture, for planes which were sent out on this late afternoon strike would probably not all be operational for a morning strike. Consequently, Commander Fifth Fleet was informed that the carriers were firing their bolt.”14

“Launch first deckloads as soon as possible,” Mitscher signaled his carriers. “Prepare to launch second deckload.”15 Mitscher also told Spruance, “Expect to launch everything we have. We will probably have to recover at night.”16

Aboard the big carriers Bunker Hill, Enterprise, Hornet, Lexington, Wasp, and Yorktown and the light carriers Bataan, Belleau Wood, Cabot, Monterey, and San Jacinto* pilots whistled too, as the target information flickered on the teletype screens in the ready rooms. But these were not happy whistles. The usual exuberance of the fliers was considerably dampened by this information. In many of the ready rooms Mitscher’s final instructions were boldly chalked onto blackboards—“GET THE CARRIERS!”

Over the loudspeakers came the order, “Pilots, man your planes!” Pilots and crewmen raced for their aircraft. For this launch there was no bantering or good-natured ribbing among the fliers. They all knew this was going to be a rough mission. At their planes the pilots quickly strapped in with the help of their plane captains, and just as quickly glanced at their fuel gauges. All planes had been topped off, but with the exception of the Hellcats, they would be cutting it awfully close.

“Start engines!” came over the bullhorn, and a whine, followed by the pistol-shot bark of cartridge starters, cut through the air. A tentative chug sounded for a few seconds, then the engines settled into a throaty roar.

Immediately the deck signalmen began coaching the first aircraft into position. The carriers had begun to swing around to the east at 1621 and picked up speed to 23 knots. The order “Launch aircraft!” came, and at 1624 Lieutenant Henry Kosciusko lifted his Hellcat off the Lexington’s flight deck.

On the other flattops the deck crews were also sending their planes off as fast as possible. The hard-working deck crews performed wonders, and ten minutes after Kosciusko had taken off, the last plane had left its carrier. It had been a superbly executed (and for many carriers, a record low time) launch. At 1636 TF 58 came back northwestward.

As TF 58 was launching its planes, Admiral Ozawa was studying an interesting message from the cruiser Atago. The cruiser had picked up the report from Nelson’s little group informing Mitscher of the revised position of the Mobile Fleet. It was obvious that his ships had been discovered, but it took Ozawa another thirty minutes to order all fueling stopped. He next ordered his ships to change course from west to northwest and increase speed to 24 knots.

While his planes were being launched, Mitscher received the depressing news that the enemy was some 60 miles farther west than had originally been thought. After consulting his staff, Mitscher decided to hold the second deckload for use the next day. “Have launched deckload strike,” he informed Admiral Spruance at 1644. “Expect retain second deckload for tomorrow morning.”17

The eleven carriers had dispatched 240 planes against the Mobile Fleet. Fourteen of these aborted for various reasons and returned to their ships. Of the planes that continued on, 95 were Hellcats (some carrying 500-pounders), 54 were Avengers (only a few of which were carrying torpedoes; the rest, four 500-pound bombs), 51 were Helldivers, and the remaining 26 planes were Dauntlesses flying out for their last carrier battle.

There was no organized rendezvous as usually practiced by the squadrons. Each unit set off to the northwest on its own, gradually joining up with other squadrons on the way. The pilots climbed their planes painfully slowly to altitude, then when reaching cruising altitude, they leaned their engines as much as possible to conserve fuel. The chase after the enemy was going to be a long, slow haul.

About thirty minutes after takeoff the fliers received the shocking information that the Japanese were about 60 miles farther west.

Bombing 16’s Lieutenant Commander Weymouth got his information directly from Nelson. Nelson told Weymouth the “main body” was located at 15 30’N, 133 30’E and was heading west at 15 knots. The tanker force was about 20 miles southeast of the warships.18

Weymouth thanked Nelson and began plotting the new position. All around him the other pilots were also furiously figuring. The intercom chatter, today quite subdued, died away to almost nothing as the pilots realized the import of the new position report. It was an emotional moment in this dramatic flight.

In the cockpits of the droning planes the pilots and crewmen (some not yet out of their teens) silently figured their chances. They still had a long way to go, and it would be a long way back—to a night landing. The strain on these young fliers was tremendous. They couldn’t relax their vigilance for a second, as they couldn’t be sure when a Zeke might come screaming down to knock one of them blazing into the sea. They did not want to let their comrades down by flying all the way to the target and then not get a hit. The thought of a water landing also weighed heavily on them. But they continued west.

Commander Jackson D. Arnold, the skipper of the Hornet’s Air Group 2, had already made his plans for a water landing. “I had decided,” he later said, “that if the enemy fleet finally was discovered even farther west then originally plotted it would be best to pursue and attack, retire as far as possible before darkness set in, notify the ship by key, then have all planes in the group land in the water in the same vicinity so that rafts could be lashed together and mutual rescues could be effected.”19

While the American planes were slowly closing the distance, Ozawa was busy getting the Mobile Fleet organized. The report of the sighting of two enemy carriers had reached him at 1715. Still undismayed by his losses, Ozawa had Admiral Obayashi launch a small raid of seven torpedo-carrying Kates led by three radar-equipped Jills. If caught by darkness after attacking TF 58, these planes were to continue on to Guam and Rota. Shortly before 1800 Ozawa told Kurita to prepare his ships (the heavy vessels screening Obayashi’s carriers) for use as a diversionary force in a possible night action. The Americans came on the scene before the order was executed, and it is probably just as well for the Japanese that it was never carried out, since the Mobile Fleet was then too strung out.

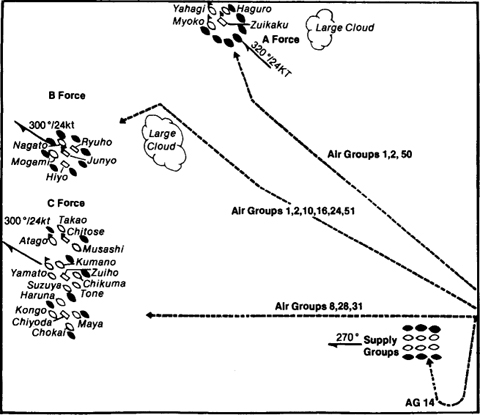

The Mobile Fleet was badly lopsided. Farthest to the north was A Force and the Zuikaku. Accompanying her were the cruisers Myoko, Haguro, and Yahagi and seven destroyers. A Force was heading 320 degrees and making 24 knots. About 18 miles to the southwest of the remains of CarDiv 1 was Admiral Joshima’s B Force and CarDiv 2. The two big carriers Junyo and Hiyo and the light carrier Ryuho were screened by the battleship Nagato, the cruiser Mogami and eight destroyers. (The Mogami had been ordered to join C Force, but this had not been done when the attack came in; which was probably just as well since both A and B Forces had few screening vessels already.) Both B and C Forces were steaming a course divergent (300 degrees at 24 knots) from A Force. This did not help the antiaircraft defenses of the Mobile Fleet. Some eight miles farther south was Admiral Kurita’s C Force, with Admiral Obayashi’s CarDiv 3 in formation. Here was the firepower of the Mobile Fleet. Ostensibly the Van Force, Kurita’s ships were now out of position to intercept attackers from the east, but they could still throw out a lot of steel. The force’s three light carriers were fairly even with each other on a north-south line. Each was surrounded by an extremely close screen of heavy ships and destroyers. At the north end of the formation was the carrier Chitose, covered by the superbattleship Musashi and the cruisers Takao and Atago. The Zuiho was next in line, escorted by the second superbattleship Yamato and the cruisers Chikuma, Kumano, Suzuya, and Tone. On the south flank was the Chiyoda. Guarding her were the battleships Kongo and Haruna and the cruisers Chokai and Maya. Adding their weight to the firepower of C Force were seven destroyers and the light cruiser Noshiro. Finally, bringing up the rear about 40 miles to the east and slightly south were the vulnerable oilers of the 1st and 2nd Supply Forces. These six oilers were escorted by a like number of destroyers. Heading 270 degrees and unable to make the 24 knots the Mobile Fleet was doing, these vessels were rapidly being left behind.

Shortly after 1800, radars on C Force ships supposedly detected the incoming attack. The reported bearing (230 degrees relative) was in no way related to the actual bearing of the American planes. It is possible that the detection and/or bearing was either operator error or one of those “glitches” that confounded radar operators on both sides during the war.

The first accurate sighting of the attackers was made at 1825 by a scout plane searching just to the east. The Americans were reported splitting into four groups for the attack. It was another few minutes, however, before an American pilot saw any part of the Japanese fleet.

The scene as the Americans came upon the Mobile Fleet was one that Hollywood could not have staged any better. To the west the sun, a blood-red ball that reminded many pilots of the “meatballs” (slang for the national insignia or Hinomaru) on Japanese planes, was low on the horizon. Its rays dyed scattered clouds stacked from 3,000 to 10,000 feet, brilliant reds, oranges, and golds. Between A and B Forces lay a big cumulus buildup swelling to over 14,000 feet. Another large cloud formation lay northeast of A Force. To accompany this backdrop was a fireworks display like nothing the Americans had ever seen. Bursts of red, blue, black, pink, yellow, and lavender flak, with some spectacular white blossoms flinging out streamers of phosphorus, speckled the sky. It was magnificent—and very, very deadly.

The battle that now took place was a wild, incoherent melee. In the twenty to thirty minutes of daylight that were left to them, the Americans dove on the enemy ships in uncoordinated attacks from every direction. There was no time to join up, orbit looking for the right target, and make a textbook approach and attack. For most, there was just time to make one pass and get out. The action was so fast and furious, and spread out over so large an area, that many of the attackers never saw an enemy plane. In fact, it was believed and reported to Admiral Mitscher that not more than thirty-five fighters had attacked the Americans. Actually, Ozawa was able to clear his decks of forty Zeke fighters and twenty-eight fighter-bombers. No matter the actual number, those that did intercept seemed to be a veteran group which managed to escape the Turkey Shoot.

Most of the air groups zeroing in on the Mobile Fleet had either not seen the oiler group straggling along in the wake of the faster ships or had passed it up in favor of “bigger game.” But these valuable ships were not to escape unscathed. The Wasp’s Air Group 14 saw to that.

Led by Lieutenant Commander Blitch, the Wasp group consisted of sixteen Hellcats without bombs, twelve SB2CS carrying one 1,000-pound and two 250-pound GP bombs each, and seven Avengers, each with four 500-pound GP bombs. As he followed the Bunker Hill’s planes, Blitch saw the Supply Group. However, he did not see the rest of the Mobile Fleet. Relying on reports from another group’s planes of two carriers to the south, Blitch led his force in that direction. This was a mistake, as he found out after flying south about 40 miles. He decided to do a “180” and attack the oilers.

His decision was based on two thoughts: his planes were getting low on fuel, and he figured that “this time [TF 58] would chase the Jap Fleet instead of running away from it [and he] decided to knock out the fleet oilers in order to prevent a speedy retirement, which would require refueling by them.”20

As he neared the Supply Group, Blitch studied his target intently. Against four of the oilers he sent three “2Cs” each. A fifth oiler—the last in line—received the attention of four Turkeys. The last three torpedo planes were to attack whatever targets looked particularly inviting. Blitch divided his fighters into two groups, eight of which were to strafe the destroyers and the remainder to provide cover, then proceed to the rendezvous 10 miles west of the Supply Group.

As the planes dove to the attack, the two columns of three oilers each divided sharply. One column began a hard turn to port, while the other followed suit to starboard. The Americans discovered that the Supply Group was no patsy, as destroyers and oilers alike threw up a wall of flak. Many of the attackers took numerous 25-mm and 37-mm hits as they dropped down.

The Helldivers, followed closely by the Avengers, did a job on the slow-moving oilers. The Seiyo Maru took several bombs that started a large blaze. The Genyo Maru was ripped open by four near-misses and coasted to a stop. A third oiler, the Hayasui Maru, was hit by one bomb and near-missed by two others. The other oilers and a pair of destroyers also received considerable attention with near-misses and strafing. The Hayasui Maru’s damage control party was efficient and was able to put out the fire caused by the bomb. She reached safety. The other two oilers that were hit were not so lucky. The damage to the Seiyo Maru and the Genyo Maru was so extensive that they were scuttled that evening, the surviving crewmen being rescued by destroyers.

A group of Zekes jumped Air Group 14 as it headed for the rendezvous. Five Helldivers that had become separated from the rest of the planes encountered six fighters that knocked down one of the bombers. The enemy planes were finally driven off by Hellcats from another group. Another bunch of Zekes were waiting at the rendezvous, and for a few minutes a furious battle took place between the opposing fighters. Though Fighting 14 claimed five enemy fighters, the squadron lost Lieutenant E. E. Cotton. Cotton and a Zeke pilot disappeared in a brilliant flash as they flew head-on into each other. The remainder of the Air Group reformed and began the long flight back to the Wasp.

To the west of the Supply Group, all three parts of Ozawa’s force were now coming under attack in a wild and confusing scene. With so little time left before darkness settled over the ocean and with fuel running low, the attackers did not take time to set up coordinated attacks, but made “every man for himself” runs from every possible direction. In fact, it appears that one group leader might have been a bit too eager to get in and get back out: “Pilots . . . reported being greatly disconcerted at hearing a transmission of the task group flight leader to the planes of his home carrier, telling them to make a quick attack so as to get back to base and into the traffic circle before other planes arrived.”21 However, Admiral Clark would later absolve the leader of any blame, saying, “The radio transmission to hurry home was made to the fighters with a view of getting them landed and out of the way before the heavier planes came back short of fuel.”22

The attack on the Mobile Fleet, 20 June 1944.

At the northern edge of the Mobile Fleet, the Zuikaku hurriedly launched nine fighters as the Americans approached. These nine Zekes, along with eight others already airborne, were all that the Zuikaku could muster after the Turkey Shoot. The attackers now boring in on this force came from TG 58.1. Leading them was Air Group 2’s skipper, Commander Arnold. As he drew near, Arnold saw Ozawa’s A Force to the north and, separated by a big cumulus buildup, Joshima’s ships 15 miles to the southwest. But what caught Arnold’s eye was the big carrier alone to the north. He had seen the Zuikaku before in the Coral Sea and did not want to let this veteran escape again. Quickly Arnold ordered his planes to attack the Zuikaku.

The flattop was steaming northwest at 24 knots when the Hornet planes attacked. On each side of her bow, 1,600 yards away, were the Myoko and Haguro. In an approximately 2,200-yard circle around the carrier were the Yahagi and seven destroyers. Although not supposed to lead the attack, Lieutenant H. L. Buell’s division was in the best position to make a run on the Zuikaku, and so he was given permission to lead the way. In an 80-degree dive, Buell led the first six Bombing 2 Helldivers down. The enemy ships opened up with a colorful pyrotechnic display. Into the fiery show the planes dove, releasing their thousand-pounders at about 2,500 feet. The flattop was slewing around in a hard starboard turn as Buell’s group dropped on her and presented a “good lengthwise stem-to-stern target.”23 The fliers thought they had made two or three solid hits on the ship, for explosions and fires were seen to start on her.

Lieutenant Commander G. B. Campbell led a group of eight planes around a large cloud just north of A Force in order to dive into the wind and out of the setting sun. These planes pushed over from 12,000 feet and also released their 1,000-pound GP and SAP bombs at 2,500 feet. As Campbell attacked, he saw “one big hole with a fire down inside near the island.”24 Most of the crews noticed large fires raging from amidships forward. Like the pilots of the other division, these Helldiver fliers thought they had scored telling hits on the Zuikaku.

When he pulled out of his dive, Ensign E. D. Sonnenberg was jumped by a Zeke. His gunner pumped a stream of .30-caliber fire at the fighter, apparently damaging it, for it beat a quick retreat. Another Zeke made a run on Sonnenberg’s Beast, but it was also chased off by his gunner’s fire.

As the last Hornet plane pulled out of its dive and screamed over the escorting vessels (treating some of them to strafing), Lieutenant Commander J. W. Runyan led his thirteen Yorktown Helldivers down from 15,000 feet against the carrier. (The “Yorktown had been called upon to launch twelve VB in this attack. However, mindful of the unreliability of the SB2C aircraft, fifteen had been launched. Two had been forced to return to base due to minor operational difficulties.”)25 The antiaircraft fire was extremely intense, buffeting the planes all the way down and following their retirement. Runyan could see a “large hole rimmed with fire apparently emanating from the hangar deck below.”26 The Bombing 1 pilots all released their bombs between 1,000 and 2,000 feet. One hit was observed aft of the island, another on the port side opposite the island, and a third on the stern. Several more bombs were close near-misses. The Zuikaku was burning and smoking heavily now, and the last two Yorktown pilots broke out of their dives to attack (with unknown results) a nearby heavy cruiser.

The Zuikaku is surrounded by bomb bursts as she twists and turns to escape the attacks.

Following close on the heels of the dive bombers were six Hornet torpedo planes—four of which carried torpedoes, the other two, four 500-pound bombs. The glide-bombing attacks were easily deflected by the violently maneuvering Zuikaku. But the VT-2 pilots certainly tried hard enough. Lieutenant (jg) K. P. Sullivan was boring in on the carrier and was just about to release his torpedo when he discovered a flak burst had jammed his bomb-bay doors. As he passed over the Zuikaku’s stern, Sullivan saw a heavy cruiser dead ahead and decided to try again. After a few jerks on the emergency release handle, his torpedo did drop. The cruiser turned toward Sullivan and his “fish” missed to the right.

Ensign V. G. Stauber also had his troubles. As he made his run-in, he found that he had forgotten to open his bomb-bay doors. Breaking to the right and down the Zuikaku’s starboard side, he proceeded to make a run on a heavy cruiser. Remembering to open his doors this time, Stauber dropped his torpedo which ran “hot and true.” His turret gunner excitedly reported a spout of dirty water and smoke at the end of the torpedo’s track. But it was not a hit. What it actually was will never be known. The Japanese reported no hits to any vessel in A Force other than the Zuikaku. Possibly the torpedo “prematured,” or a near-miss from a dive bomber caused the apparent hit.

The last planes to attack the Zuikaku came from the light carrier Bataan. The ten VF-50 Hellcats carried 500-pound bombs. Lieutenant C. M. Hinn took six fighters to the east, and Lieutenant Clifford E. Fanning led his division west in order to bracket the carrier. Nearing the enemy ships, Hinn’s group entered the cloud just north of A Force. Out of the cover of the cloud they dove on the ships from 8,000 feet. Two pilots circled west to dive on the Zuikaku from that direction, while Hinn led the rest of his planes against a heavy cruiser. The Bataan pilots did not notice what their bombs did, though they did see one bomb tumbling end-over-end, its tail fins missing.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Fanning’s division had run into a hornet’s nest. As he led his team in a circle around the Zuikaku, Fanning saw two Zekes pouncing on a pair of unsuspecting Hellcats. Firewalling his fighter, Fanning was able to get on the tail of one of the Zekes, and gunned it down. The other enemy plane broke away and was not seen again. The division pulled up to 17,000 feet, dropped their belly tanks, and began spacing out in preparation for their attacks on the burning flattop. Just then about fifteen or twenty Zekes, painted up dirty green with shiny black cowls, jumped them. The division broke up and it became every man for himself.

Two Zekes zipped in front of Fanning and he broke sharply left to get behind them. Just as he lined up on one fighter, tracers arced over his wings. Fanning rolled right, but the enemy’s fire apparently had parted his right rudder cable, for his Hellcat went into a flat spin. The Japanese pilot followed him down and gave him another burst. There was an explosion and his windshield was covered with oil. All his flight controls suddenly went free, and Fanning began thinking about leaving his plane. But since he still had plenty of altitude and did not want to bail out over the Japanese fleet, he stayed with his plane a bit longer. His patience was rewarded, for he was finally able to pull out at 10,000 feet.

Although the “oil” that coated his windshield turned out to be hydraulic fluid, not oil, and although the big Pratt and Whitney R-2800 kept ticking over, Fanning’s situation still was not bright. Besides his rudder problem, the right aileron cable and part of his left flap had been shot away; two-thirds of his right stabilizer had buckled and was hanging straight down; his radios were knocked out; and he had several shrapnel splinters in his left shoulder and one over his left eye. But Fanning decided to try for the Bataan anyway.

When the Zekes first jumped them, Lieutenant Wiley A. Stoner and Ensign Cyrus S. Beard had split-essed instead of scissoring. As he pulled out, Beard saw an F6F being attacked by an enemy fighter. He shot the Zeke off the American’s tail, but not before the Hellcat staggered up in a climb, then fell off on a wing. (Beard thought the pilot was Stoner, who did not return from the fight.) He did not have time to follow the other Hellcat down because of all the Zekes around him. The next few minutes were just a blur to Beard as he twisted and turned to escape his assailants. He was able to destroy one more Zeke before he broke off the action. One incident in these chaotic minutes remained imprinted in Beard’s memory: “He found himself in a spin and saw a Zeke shoot down over him and then pull up sharply above. As the Jap reached the top of his zoom, he seemed to flip right around on his tail and start down again without once swerving out of his original line of flight. Beard nosed down, picked up a little speed and then pulled up straight into the enemy plane, hoping to divert him from his dive. Placing his pipper squarely on the Jap’s spinner, he held the trigger in a long no-deflection burst. Just as Beard’s plane stalled out, the Jap whizzed past missing him by what seemed like about three feet.”27

Beard was sure he had damaged the fighter, but could not follow the Zeke down. As he nosed over, another Zeke shot away his radio aerial. He headed for the safety of a cloud. Finally evading the Zekes, Beard joined three other F6Fs and headed for home. The fourth member of the division, Lieutenant (jg) William Y. Irwin, shot down one fighter and damaged two more before setting out to the east.

As the Americans left the area, they could see the Zuikaku burning furiously. The carrier was in serious trouble. Besides the bomb hits and near-misses, she had been strafed several times, causing some injuries topside. Fires on the hangar deck were getting out of control rapidly, and her damage control parties were being forced to use hand fire extinguishers, the Zuikaku’s water mains being knocked out. The order “Abandon Ship!” was given, only to be cancelled a few minutes later when the damage control personnel began to make headway against the fire. The fires were eventually brought under control, and the Zuikaku reported her “fighting and navigational capabilities not impaired.”28 Perhaps they weren’t impaired, but she had precious little left of her main battery (her planes) to fight with. She eventually made it back to Japan and was repaired—in time to be sunk four months later.

While the Zuikaku was undergoing her ordeal, the main body of the U. S. planes were falling on Joshima’s B Force. His ships were beating a healthy 24 knots to the northwest when they were first seen. Besides the antiaircraft fire put up by his ships, Joshima’s B Force had the protection of the largest group of fighters left in the Mobile Fleet—about thirty-eight. He would need their help.

Among the first planes to drop on B Force were fourteen bomb-toting Hellcats led by Commander Arnold. After he had sent his dive and torpedo bombers toward the Zuikaku, Arnold had turned southwest toward the carriers of CarDiv 2. The Hornet fighters closed up behind him. Picking out a flattop to attack, Arnold chose what he identified as a light carrier. If he and the rest of the Hornet fliers were correct in their ship identification, then they attacked the Ryuho. (Ship identification was a field in which aviators on both sides were sometimes not very precise. To compound the problem, during the battle the Americans consistently erred in calling Joshima’s Hiyo and Junyo, the “Hitaka” and “Hayataka.” This was caused by a misreading of the Japanese characters for the names of these two ships.) The “Rippers” dove on the carrier, claiming at least one hit, but Japanese records show only near-misses that caused minor damage.29

Following closely behind the Hornet planes were some more bombladen fighters, this group from the Yorktown. Air Group 1’s CO, Commander Peters, and his division stayed at altitude to coordinate and observe the action. Peters later commented, “The AA fire from scattered ships and the wide area in which forces were involved made it comparable to watching a ten ring circus with a sniper shooting at you from behind the lions cage.”30

While Peters’s little group remained high, “Smoke” Strean led eleven “Top Hat” fighters to the west between A and B Forces looking for enemy fighters. When he found none, Strean turned back toward Joshima’s ships. Strean saw a likely-looking target, identified as a “Hitaka-class carrier,” in the southwestern part of the force. When he got within range, Strean took his pilots down from 10,000 feet in 60-degree dives. Most releases were made around 2,500 feet, with the pilots pulling out at 1,000 feet. The young fliers claimed three hits and five near-misses. One bomb was seen to go through the edge of the flight deck and explode in the water close aboard. One pilot who dove too steeply unloaded his bomb on a light cruiser instead, missing it by just a few yards.

Whether the ship the Yorktown fighter pilots attacked was the Hiyo or the Junyo is still unknown. Both ships were damaged during the confusion of the attacks, but by what groups is impossible to determine.

The next Yorktown planes to attack were five torpedo-carrying and three bomb-laden Avengers, all led by Lieutenant Charles W. Nelson. He took the five planes with torpedoes between the two enemy forces, then made a steep left-hand diving turn through some clouds toward B Force. Breaking out of the clouds at 2,500 feet, the Americans leveled off at 350 feet. The Ryuho was the target. Darting in at 220 knots, the Avenger pilots waited until 1,000 yards from the carrier before dropping their torpedoes. They claimed two hits on the flattop, as well as one more on a destroyer which “blew up and sank.” Another “fish” was aimed at a cruiser which overlapped the light carrier, but it apparently missed. As Nelson pulled out, his Avenger was smashed by flak and it plunged burning into the sea. The other Avengers were attacked in their pullouts by Zekes, but these were driven off by the gunners and the timely arrival of an unidentified F6F.31

The three TBMs with bombs had initially turned toward A Force, but finding themselves alone, turned back against Joshima’s ships. A glide-bombing attack from 10,000 to 2,500 feet was made on a large carrier. Lieutenant Robert L. Carlson’s plane was hit by antiaircraft fire and it tumbled down in flames. The other three aircraft claimed three hits on the carrier.

Again, Japanese and American claims of hits do not reconcile. No destroyer was hit and, certainly, not all of the hits on the carriers of B Force can be attributed to any single unit. Commander Peters, high above the action, was skeptical about the claims of the attackers.

“Observations made by pilots of attacking planes are almost totally unreliable,” he said later. “The camera is the only good observer. From the air, a bomb hit doesn’t appear much different from the AA fire of the ship during the plane’s approach. Hits can be estimated more by the lack of splashes in the water than by any other method. Naturally, if a fire is started it is readily visible.”32

Meanwhile, four torpedo-armed Belleau Wood Avengers had been among the first planes over the Mobile Fleet. Lieutenant (jg) George P. Brown led the quartet. Initially the Belleau Wood aircraft had been part of the force targeted for the Zuikaku. But when the other TG 58.1 planes scooted north to attack that ship, Brown saw the Hiyo. It appeared that the flattop was not under attack at that time, and Brown wanted to get a hit on a carrier badly. Now he was going to get his chance.

The cloud between A and B Forces attracted his eye. He took his group down through it in a 50-degree dive from 12,000 feet. A 180-degree turn was made while descending so as to have the setting sun behind the planes when they made their runs. When they broke through some scattered clouds at 2,000 feet, the Avenger pilots found they still had about 5,000 yards to go before they would be able to drop their torpedoes. Nevertheless, they bored in, spreading out for an “anvil” attack on the carrier. Brown came in on the bow just off to port, while Lieutenant (jg) Benjamin C. Tate approached off the starboard bow and Lieutenant (jg) Warren R. Omark made his run from the starboard quarter. Ensign W. D. Luton, flying the fourth Avenger, got separated from the others during the turn and went searching for other game.

When the planes broke out of the clouds, intense antiaircraft fire began smudging the sky around them. Brown’s big Avenger was hit several times as he descended for his final run. Parts of the left wing were ripped off, and a blaze broke out in the fuselage. Brown pulled up and his radioman, ARM2C Ellis C. Babcock, and gunner, AMM2C George H. Platz, immediately bailed out. They drifted down into the middle of the fleet where they had ringside seats for the remainder of the battle.

With his crewmen away, Brown stayed with his plane and returned to his attack altitude. Nothing was going to stop him from his attack, not even a terrible wound that must have made flying the big TBF extremely painful. The fire soon burned itself out. The Hiyo was heeling over in a sharp turn to port when Brown dropped his torpedo. It ran hot, and probably hit. After his drop, Brown flew the length of the carrier hoping to draw fire away from his comrades now making their runs.

Tate’s torpedo also ran hot but might have missed. (The Japanese later claimed that only one aerial torpedo hit, but then said that a submarine torpedo also hit, causing a “large conflagration.”33 Since no sub was present then, it can be inferred that two aerial torpedoes hit or that an internal explosion occurred. Finally, bailed-out crewmen floating nearby say three torpedoes hit.)

In any event, Omark’s torpedo ran hot and true. The Hiyo was fully in her turn when Omark came barreling in at 240 knots and 400 feet. His torpedo smashed into the carrier’s side about a quarter of a length from the bow. Water rushed through the hole and flooded the engine room. The carrier coasted to a stop near where Babcock, Platz, and a Lexington Avenger crew were observing the scene from water level. Ensign Luton had also attacked another carrier, but with no results, so far as he and his crew could tell.

As the Belleau Wood planes pulled away, defending fighters flashed in. Lieutenant Tate’s plane had already been hit by antiaircraft fire several times. The top of his stick had been shot off, and he could not use his wing guns. The turret gun was also jammed and out of commission. Two Zekes positioned themselves on either side of him and took turns making passes on the Avenger. Tate bluffed them by turning into them on each attack, and the Zekes would break off. Tate was finally able to escape when he found a friendly cloud. After popping back out of the cloud, he joined with a TBF flying low on the water. It was Brown. His plane was a blackened, mangled mess. Brown was seriously injured, blood pouring from his wounds. Tate tried to shepherd him home, but Brown could not fly a straight course and Tate eventually lost him in the growing darkness.

Omark had also been jumped by the enemy—one Zeke and two Vals—but his turret gunner drove them off with accurate fire. After shaking off the enemy, he headed east and soon overtook Brown, still pressing doggedly for home. Omark led his shipmate toward the task force as darkness settled over the Philippine Sea. Brown’s flying grew increasingly erratic, and Omark finally lost him when Brown flew into a cloud. Brown never returned to the Belleau Wood.

Antiaircraft fire had hit Luton’s Avenger and jammed his bomb-bay doors in the open position. Luton went as far as he could before the drag of the doors exhausted his fuel supply, then set his plane in the water. He and his crew were rescued the next day.34

The Belleau Wood lost one more plane during the attack and in a rather unusual way. In the initial attack the Fighting 24 Hellcats, three of which were carrying 500-pounders, were jumped by several enemy fighters. The bomb-laden Hellcats quickly dove away to drop their bombs with unobserved results. The other fighters mixed it up with the Zekes. Lieutenant (jg) V. Christensen scored a probable but had his own plane shot up in the process.

Ensign M. H. Barr evaded one Zeke then saw a Hellcat being chased by a pair of enemy planes. As the trio flashed by, he exploded one Zeke and sent the other away smoking. Still another Zeke made a run on Barr but overshot and Barr was able to put some damaging bursts into it. Barr then saw Lieutenant (jg) R. C. Tabler being chased by a Zeke and dove down to chase the enemy away. Just then “all hell broke loose.”35

Heavy shells had torn into his plane and fire broke out in the cockpit. Barr threw open his canopy, unbuckled his seat belt and began to climb out. More tracers whizzed by and the fire went out, so he decided to climb back in and try to get away from the Japanese fleet. His situation was grave. The blast of machine-gun fire had torn up his wings and fuselage. Two to three inches of gasoline were sloshing about the cockpit. His hydraulic system had been shot out, as well as most of his instruments, and his engine was barely running.

Finally, Barr decided to ditch. Despite a fire in his wing and the fact that his left wing “kept ‘falling off’ and looked as though it would crumble,”36 he was able to make an easy water landing. He climbed into his raft and watched Tabler fly back toward TF 58. Barr was rescued the next day. Barr later claimed (and was backed up by Tabler, who had witnessed the incident) that it was an overeager Hellcat pilot who had brought him down. But he was lucky. The six .50-calibers in a Hellcat had devastating power.

The attacks on B Force were not over yet. Trailing behind the Yorktown and Hornet groups were the planes from the Lexington’s Air Group 16 and the Enterprise’s Air Group 10. The two groups were built around the aging but still well-liked Dauntless dive bomber. The Lexington had sent fourteen of them, accompanied by six Avengers and nine Hellcats. (Two fighters, one TBF, and one SBD had returned earlier with mechanical problems.) Actually, VB-16 still had fifteen SBDs in the attack for Lieutenant (jg) Jack L. Wright, having landed on the Enterprise with an emergency the day before, launched from that carrier and bombed with VB-10, then rejoined his own unit for the flight home. The Enterprise sent eleven dive bombers, five torpedo planes, and twelve fighters. None of the Avengers carried torpedoes. Tagging along with the big carriers’ aircraft were two more bombtoting Avengers—all that the San Jacinto could send.

Ralph Weymouth, leading the Lexington group, saw the large oil slick that many of the earlier attackers had seen, and changed course to 300 degrees to follow it. The other planes, bobbing and weaving gently in the air, followed. Shortly after changing course a pilot saw some ships ahead. As he neared them, Weymouth could see they were the oilers and escorts of the Supply Group. Weymouth kept going, ignoring the supply vessels. Other pilots, whose sharpness of eye was not up to that of their skipper’s, took the oilers to be carriers and wondered what the hell he was up to. Weymouth knew his job, however, and had better targets in mind.

At 1845 he changed course ten degrees to the right to pass under the overhang of the huge thunderhead sitting to the east of Joshima’s ships. As the Lexington planes came around the north side of the cumulus mass, what appeared to be the entire Japanese Navy was suddenly spread out before the Americans.37

Indeed, it was much of the Japanese Navy. To the northwest was the Zuikaku, burning and smoking and under attack by another group. Far to the west was another body of ships, too distant to be identified. Fifteen miles ahead, Weymouth saw what he guessed were two “Hayataka”-class carriers, two or three Kongo-class battleships, two to four Mogami and Tone-class cruisers, and four to six destroyers or light cruisers. About four miles east-southeast of this formation was a Chitose-class light carrier with its screen. Weymouth’s eyesight was not too bad, although only the battleship Nagato and the heavy cruiser Mogami were actually present, along with eight destroyers.

As the Lexington planes eased around the cloud, the pilots heard an urgent “Tallyho!” on the radio, and seven of the fighters zoomed up to engage the enemy. All they found were more Hellcats. Disgustedly, the VF-16 pilots reversed course. The Lexington bombers were nowhere in sight! They had seemingly vanished; the seven fighter pilots would not see the other planes until after the battle. The only fighters left to protect the bombers were the two flown by Alex Vraciu and Ensign Homer W. Brockmeyer.

The two F6F pilots and the rest of the Lexington fliers were surprised when eight Zekes from the Zuikaku suddenly slashed into them from out of the clouds. The enemy attack was well planned, and they blasted Lieutenant (jg) Warren E. McLellan’s Avenger out of the sky on the first pass. McLellan did not know he was under attack until “about fifty tracers appeared to pass through (his) plane and go directly out ahead and slightly upwards.”38 He honked back on the stick and the plane shot upwards, but by now his cockpit and the center section of the plane were afire. McLellan was unable to reach the mike to tell his crewmen to bail out, but ARM2C Selbie Greenhalgh and AMM2C John S. Hutchinson needed no urging to abandon ship. With his cockpit becoming a blowtorch, McLellan leaned out of his plane as far as possible, placed his feet on the instrument panel and pushed himself out. Under the billowing silk of their chutes, the three men drifted down into the rapidly expanding darkness. In the meantime, the other Avengers were able to keep the Zekes at a distance with accurate fire.

When the Zekes appeared, Vraciu found himself with plenty of company. He and Brockmeyer were boxed in by the enemy planes. The two pilots began to scissor as the Zekes darted in. But there were too many of them, and one got in behind Brockmeyer. Before Vraciu was able to get a clear shot at the enemy plane, Brockmeyer’s Hellcat was hit and spiraled down, leaving a heavy trail of smoke. Vraciu exploded his partner’s assailant with two bursts. Vraciu then smoked another Zeke with a head-on pass, but did not see it crash. As quickly as the fight started, it was over. The remaining Zekes raced ahead to catch the SBDs, leaving Vraciu with the sky to himself.

The Dauntlesses were not to be easy pickings. The rear-seat men had seen the attacks on the TBFs and were waiting for the enemy to close. A fusillade of .30-caliber fire met the enemy planes, and they were unable to get close enough to do any damage. The Zekes pulled away as the fleet’s fantastic antiaircraft fire display began reaching for the Dauntlesses. The dive bombers were now at 11,500 feet, having dropped slightly from their cruising altitude during the fighter attack. Weymouth had led his pilots to the west as he had studied the targets. Now he brought them around in a left-hand turn toward the pushover point. They would be making an upwind attack to the east. At his signal the SBDs lined up in their bombing order.

At 1904 Weymouth pushed over toward his target—the southern “Hayataka.” (This should have been the Hiyo, but it appears the Lexington fliers attacked the Junyo.) At 1,500 feet he dropped his bomb and began his pullout. His gunner thought he saw a smoke billow up near the carrier’s island. Following closely behind Weymouth—so closely that there were three or four bombs in the air simultaneously—were eleven other SBDs. The pilots thought they had hit their target at least six more times. After the battle the Japanese stated that the Junyo had received two hits near the stack and six near-misses.39

Three of the Bombing 16 pilots did dive on the Hiyo. Lieutenant (jg) George T. Glacken found himself out of position almost directly over the Junyo. He decided to drop his bomb on the carrier to the north. Just as he released, the Hiyo heeled over in a turn and his bomb hit just off the stern. Lieutenant Cook Cleland and Ensign John F. Caffey followed Glacken, claiming hits on the flattop’s fantail and aft of the island. “The ship was smoking heavily and there was a fire on the flight deck as these planes retired.”40

Coming in at the same time as the dive bombers were the Torpedo 16 Avengers, led by Lieutenant Norman A. Sterrie. The TBFs were each carrying four 500-pound SAP bombs. As with the other bomb-toting torpedo planes, they had to use the glide-bomb technique. Sterrie led his planes down from 9,000 feet. Airspeed quickly built up to over 300 knots, faster than the TBFs were supposedly stressed for, before the pilots pickled out their bombs between 1,800 and 3,000 feet. Their speed was so great that one plane had its right-hand bomb-bay door crushed; the bombs on that side skipping erratically into space when dropped. Another Avenger lost its center canopy when the speed proved too fast. The Lexington fliers thought they had hit their target—most likely the Junyo—at least three times.

The two San Jacinto Avengers came in as the Lexington fliers were making their attacks. The VT-51 pilots, Lieutenant Commander D. J. Melvin and Ensign J. O. Guy, thought they had actually made the first attacks on a carrier—probably the Hiyo—for they saw no dive bombers making any move toward the ship. Guy released his bombs from 5,000 feet and did not see any results, though Melvin was sure his wingman had scored two hits. Melvin, meanwhile, was having a problem. He had not noticed that his bombs had not released until he began his pullout. Pushing over again, he found he was in a good position for an attack on a destroyer. From 2,500 feet he manually released his bombs and watched one hit inside the ship’s bow wave. “The other three did not hit the water but were all believed to be hits on board the starboard side near the base of the forward gun mount, for there was a violent explosion at this point that spread along a great portion of the ship’s side.”41 Since the Japanese reported no damage to any destroyer in the action, it is probable that the explosions Melvin saw were actually the flashes of the ship’s antiaircraft guns opening up on him.

The dive and torpedo bombers had not lost any of their number during the attack. But now they were going to have to fight their way out. Some very angry Japanese, employing a variety of guns, were trying their best to see that the Americans did not get home.

Weymouth decided the quickest way back was directly over several destroyers and cruisers. This turned out to be almost as exciting as the actual attack. Every ship within range opened up. By jinking and pulling every evasive maneuver they could think of (including ducking in their cockpits now and then when a shell burst too close), the Lexington fliers finally made it through the curtain of flak. But old enemies—the Zekes—were waiting for them.

Ten to twelve Zekes made passes on the Avengers as they headed for the rendezvous at 500 feet. Sterrie’s plane drew the attention of four fighters. One Zeke made a level run from the rear and the gunners were unable to track him. The enemy pilot made a fatal error, however, by half-rolling and climbing away. The turret gunner had a perfect shot and stitched the Zeke’s belly with forty rounds of .50-caliber fire. The fighter whipped over and dove into the sea.

As the TBFs fought off their attackers, the Dauntlesses were undergoing their own ordeal. When Cleland and Caffey pulled out from their attacks, a Zeke was waiting for them. The fighter came in from the right side on Cleland, but Cleland’s gunner picked him off with several bursts into the belly. A puff of smoke belched from the Zeke, a wheel dropped down, and the fighter staggered off to land in the water near a destroyer. Before the Americans could enjoy their victory, a Val or Judy with its wheels down came in from the left side. Cleland could not turn into the attack, for a two-foot flak hole in his right wing made control a little touchy. Caffey took over, charging into the enemy plane with all guns firing. The Japanese pilot took off for a quieter area.

After the rest of the SBDs had run the gauntlet of ships’ fire, eight Zekes ganged up on Weymouth’s section of three planes. Their attacks were generally lackluster, with only three making determined passes. The Zeke’s amazing maneuverability impressed the Americans even while they were under attack. The first two fighters were driven off by the combined fire of the three rear-seat men. The third Zeke pilot was more aggressive. This fighter started for Weymouth, then settled for Lieutenant (jg) Jay A. Shields’s plane. Its wing and cowling guns twinkled as it bored in closer. The three gunners returned the fire, getting hits in the fighter’s engine, but it kept coming. Lieutenant Thomas R. Sedell, Shields’s longtime roommate, saw his friend suddenly shudder violently. His head snapped back and his goggles flew off; he appeared to be screaming. He slumped over his stick and his SBD plunged into the water. As the plane started down, Shields’s gunner, ARM2c Leo O. LeMay, started to stand up in the rear cockpit with his guns spraying wildly. The guns kept firing until the ocean engulfed LeMay. The Zeke pilot had little time for elation. As he pulled up, his engine cut out and with its prop turning over slowly, his plane slammed into the sea.42

By now, Hellcats from various groups were dropping on the Zekes. Several enemy planes were shot down and the rest driven off. The Lexington planes, many damaged and one missing from each squadron, regrouped and pointed their noses east for the long flight back.

Air Group 10’s attack came about the same time as Air Group 16’s. “Killer” Kane, wearing a special helmet to protect his head still tender from his being shot down four days earlier, led the group. As he came straight in from the east, Kane saw that the Ryuho had drawn away from the other carriers by several miles. She was now in an excellent position for a dive-bombing attack.

Leaving four fighters for high cover, Kane took the remaining eight F6Fs down shortly after 1900 for strafing runs. Kane’s division raked the light carrier from stern to bow with long bursts beginning at 5,000 feet and carrying through to 2,500 feet. The other division probably strafed the Junyo. Behind the fighters came the SBDs under the command of Lieutenant Commander James D. “Jig Dog” Ramage. His planes were carrying 1,000-pound bombs, and his pilots were hoping to place them where they would do the most good.

Ramage led six Dauntlesses against the Ryuho. In their bombsights the carrier’s bulk seemed to jump at them as they drew closer. Ramage’s bomb just missed astern, but close enough to probably do some damage. Four of the next five SBDs also had near-misses, and one plane could not get its bomb to release. The last pilot to dive was Lieutenant (jg) Albert A. Schaal; his thousand-pounder sliced through the aft port corner of the flight deck. Six Zekes had followed (but not too closely) the Dauntlesses down, then sped ahead to catch the dive bombers on their pullouts.

While Ramage went after the Ryuho, Lieutenant Louis L. Bangs had taken his division of six SBDs farther west. He saw another carrier, apparently the Hiyo, that appeared to be in trouble and this made a tempting target. The Hiyo was damaged by the Belleau Wood attack. Bangs pushed over with three planes from 9,000 feet. All three hit the carrier. Bangs’s bomb hit the fantail, knocking a group of aircraft clustered there into the water. Lieutenant (jg) Cecil R. Mester’s dropped just forward of the first hit, and Lieutenant (jg) Donald Lewis followed up by planting his bomb just aft of the island on the starboard side. “A sheet of flame enveloped the side of the ship.”43 The remaining dive bombers, which included Lieutenant (jg) Wright from the Lexington, registered near-misses on an unidentified light carrier.

The Enterprise’s bomb-laden Avengers jumped the Ryuho the same time the dive bombers did. Lieutenant Van V. Eason led five planes in on the light carrier. Eason had initially spotted the Zuikaku and had tentatively planned on attacking her. Then he had seen the Ryuho at a closer distance and at that time not under attack. Though his planes were at 12,000 feet and well above their normal starting altitude for a glide-bombing attack, Eason decided the advantages of position in relation to the Ryuho outweighed any disadvantages. So, at 1915 Eason made a steep diving turn to the left, and the rest of the Avengers dropped into trail behind him.

The dives were fairly steep (about 50 degrees) and, just like their Lexington comrades, the VT-10 pilots were soon watching their airspeed needles flick past the redlines. Eason held his Avenger in the dive to 3,500 feet, then toggled his bombs at the wildly careening carrier. As he pulled out, Eason thought two of his bombs had ripped into the Ryuho. Right behind came Lieutenant (jg) Joseph A. Doyle. He released his bombs between 4,500 and 5,000 feet. As he pulled out, “two red balls on a silver grey wing flashed by in front of (him) going straight down.”44 The Zeke disappeared. Doyle laid his bombs close to the carrier’s bow and thought he also had gotten a pair of hits. As Lieutenant (jg) Ernest W. Lawton brought his big Avenger screaming down, the high speed and changing air pressure blew out his canopy glass with a crack that sounded like an AA-shell explosion. Lawton imagined he felt blood on his neck. By 5,500 feet his airspeed had built up to over 350 knots and he could not hold his sight on the carrier any longer. He released his bombs at 5,000 feet. One hung up and the other three fell off both sides of the Ryuho’s bow. Lieutenant C. B. Collins was fourth to push over, and his bombs were laid neatly across the flattop’s forward deck—one each in the water off both sides and two near the forward elevator.

Last to dive was Lieutenant (jg) Ralph W. Cummings. Like those before him, he was not happy about having to start his dive at such a high altitude, but resolved to do the best he could. As he later told his debriefing officer, at 8,000 feet he was “boresighted ahead and inside of a carrier turn that would do credit to a DD. We were set to release when Lindsey informed me that the bomb-bay doors weren’t open. When had that ever happened to me? Bomb-bay doors not open over a Jap carrier!!

“So we snarled a little, I guess, roller-coastered into a second dive, opened bomb-bay doors and from then on it was dive-bombing from 7,000 feet. Just about as we released something seemed to tear all the glass out in my hatch port side. As we pulled on out I had time to worry about being hit and noticed also that something had kicked out a lot of glass in the second cockpit port side.”45 Only three of his bombs released and all apparently missed.

The Enterprise planes pulled out to the east and beat it for home. Zekes were waiting but were not very aggressive. One fighter made a stern pass on Eason’s TBF. Due to fogging of his turret glass, Eason’s turret gunner did not fire at the Zeke until it began to break away. A long burst sliced into the Zeke’s belly. The plane slowrolled onto its back, broke into flames and crashed. Another fighter met Lawton’s and Collins’s Avengers and was badly holed before it limped off. A group of fighters jumped the SBDs of Bangs and Mester, putting 7.7- and 20-mm slugs into Mester’s wing and engine. The Wright Cyclone kept chugging away and the Zekes were finally driven off.

“Killer” Kane’s fighters waded into the Zekes harassing the Enterprise bombers. Kane and his wingman, Ensign J. L. Wolf, finished off one of the enemy planes. Wolf also got another fighter, the VF-10 pilots claiming seven in all. Ensign John I. Turner had already mixed it up with several Zekes, claiming a probable, when another pair of fighters made an overhead run on him. These two scored. Turner’s oil line was cut and the fluid covered his windshield. He made it about 30 miles farther east before he had to ditch. Twenty-four hours later he was picked up by a Wichita floatplane.

“Usual story. Folly to dogfight Zekes,” Kane later commented. “Jap pilots on this occasion better than those previously encountered, but our VF had no difficulty shooting them down if division and section tactics were followed.”46

The Enterprise planes flew east. The bomber pilots were happy. They thought their bombs had mangled and possibly sunk the Ryuho. But they were wrong. Though damaged, the Ryuho was still steaming and fighting.

The third unit in Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet, farthest to the south in the formation this day, was C Force. The three light carriers in this force were by far the best protected of any of the flattops in the Mobile Fleet, having four battleships and several cruisers as escorts. But, as related previously, earlier maneuverings had placed this potent unit out of position to do much damage to most of the attackers. The Americans were not going to let C Force off scot-free, however.

Actually, C Force was the first group in the Mobile Fleet to be attacked. Commander Ralph L. Shifley, Air Group 8’s skipper, led forty-two planes from the Bunker Hill, Monterey, and Cabot against Kurita’s vessels. At 1812 the oiler group had been sighted, but passed up in favor of better targets. Fifteen minutes later C Force was seen. At the same time a lookout on the Chiyoda saw the U.S. planes. His report was soon followed by a single antiaircraft shell, deep red in color, bursting over the center of the Japanese formation at 14,000 feet. This burst was in turn immediately followed by a barrage of shells. Though it appeared that the ships were not firing at specific targets but utilizing an area coverage, the display was every bit as fantastic—and deadly—as those by the other two forces. As only twenty-two planes were available, thirteen of which were Zekes, this antiaircraft fire was C Force’s primary defense, and the ships “fiercely attacked [the Americans] by concentrating entire fire power.”47

“The northern force contained two CVs, one was seen in the central force, and one in the southern force,” Shifley thought. “Although accurate observation was difficult, a second CV may have been in the central force. Each force was screened with BBs, CAs, and DDs. A BB of the Kongo class was in the outer screen of the southern force. There was an additional BB on the north flank of the southern force, but it was too distant to be identified.”48 Shifley also noted that only a few destroyers were available to screen the big ships.

Since it appeared that the southern group had the largest carrier, Shifley ordered his fliers to attack those ships. Thus, the Chiyoda, with the Kongo and Haruna in attendance, drew the attention of virtually all the Americans. Lieutenant Commander James D. Arbes split his twelve-aircraft group into two units—Arbes taking a division of six planes against the Chiyoda from the southeast, while Lieutenant Arthur D. Jones led the remaining SB2CS in from the north.