Figure 1.1 The mode of developmental state in South Korea and Taiwan.

An analysis of the developmental regime of statist mobilization and authoritarian integration in the anticommunist regimentation

Hee-Yeon Cho

Before the economic crisis, the South Korean development model was a ‘successful’ model to be emulated by others. Such a conception of a successful model means that the contradictions and problems inherent in this model have not been illuminated at all. However, the crisis of the South Korean economy provided the momentum for an epistemological turning moment, which has allowed us to recognize the ‘unsuccessful’ aspects, and approach the South Korean development model as a model of crisis and contradiction.

This chapter aims to analyze the structure of the Korean development model as simultaneously a basis for rapid successful growth and its sudden crisis around the mid-1990s in the wake of the East Asian financial crisis. The chapter looks at the model’s characteristics of operation and its transformations. In this study, I explore: the structure that enabled this growth, especially political-social structure; how the same structure came to be a factor in the crisis; and in what direction the South Korean development model is currently transforming.

The ‘developmental state theory’ (Johnson 1987, 1999; Amsden 1989; Evans 1995; Wade 1990; Gereffi and Wyman 1990) focused on an interventionist role for the achievement of economic growth. The developmental state theory explaining the East Asian economic miracle focuses only on the relation between the state intervention and the resulting phenomenon, that is, growth (Cho and Kim 1998: 128–132). My preference is to use the term ‘the developmental regime’ (rather than ‘the developmental state’), in order to bring to the fore the systemic and multi-faceted characteristics of the South Korean growth-oriented regime, not the phenomenal aspects of the ‘autonomous’ state intervention. I think we should not focus only on the state’s role but also see the whole structure in which more factors than the state interact.

In addition, the concept ‘regime’ is also preferred because it allows me to talk about socio-political reorganization as well as economic. Even when ‘the developmental state theory’ scholars discuss this growth, they approach it only as an economic process. In my view the growth is as much a socio-political process as it is an economic one. This is because economic growth is growth of not only the secondary industry, industrial production growth or the material production, but also socio-political reorganization of a society towards growth (Bonefeld 1987).

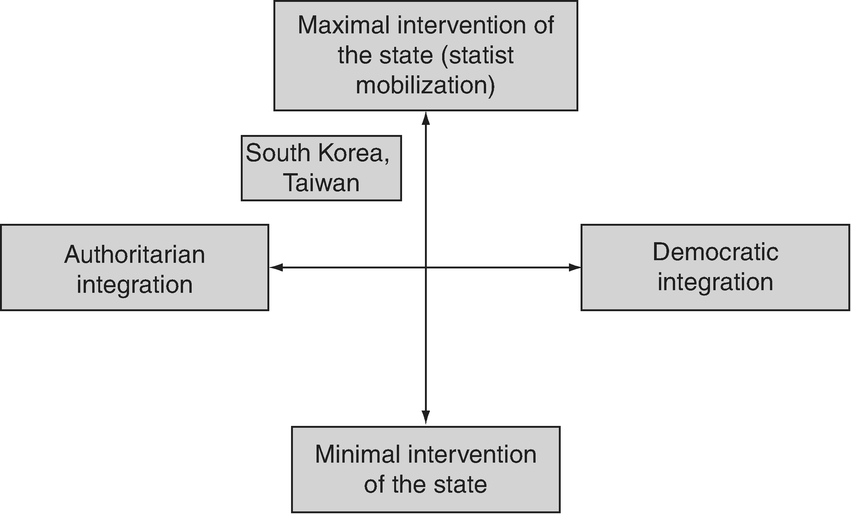

Conceiving of the growth as a socio-political reorganization includes the following two aspects. The first is the raising and distributing of material and human resources towards growth, especially in ‘resources-poor countries’ (Perkins 1994). The second is the societal integration of the members of one society towards the target of growth, that is, a kind of pro-growth integration of the working class, the popular sector and other classes. The way of raising and distributing resources is diverse from maximal intervention of the state to minimal one, while the way of the integration from very much authoritarian to very much democratic one.

Raising and distributing such resources is performed basically through the market. However, the state intervenes in this process. It is not correct to regard the state theory and market theory in East Asian development analysis as directly opposite. Rather, we can say that raising and distributing resources is performed in the interaction between the market and the state. Such interaction varies from the maximal intervention of the state to minimal one, all of which are combined with the market. Maximal intervention of the state and minimal one can be posited as poles in the same continuum, rather than the state and the market. The point is that the state’s intervention in economy is not seen as contrary to the market so the question is really whether the state’s intervention is market friendly or anti-market. For example, the state’s intervention in South Korea was market friendly: it just aimed to make business and market flourish and develop rapidly, overcoming diverse obstacles to market and business development.

In addition, we should see the difference in the way of political integration in the process of economic growth. One regime achieving a high economic growth can be democratic, however other one achieving the same growth can be authoritarian. We can characterize diverse regimes from democratic to authoritarian ones according to their political features of the developmentally oriented system.

In this sense the South Korean developmental regime, especially Park Chung-Hee’s regime, can be defined as that of maximal state intervention and authoritarian integration. This can be shown Figure 1.1. In the view of mobilization and distribution of resources, it can be defined as the regime of maximal intervention of the state, while the regime of authoritarian integration in the view of integration. I would define the maximal intervention of the state in South Korea as statist mobilization.

Figure 1.1 The mode of developmental state in South Korea and Taiwan.

There has been a precondition for the developmental regime to emerge and function smoothly. I want to conceptualize such a precondition as ‘the anticommunist regimented society’. The mobilization for growth in the maximal statist form and integration in the authoritarian form has been helped by the anticommunist regimented social situation and has been made possible by utilizing and amplifying such a situation.

If social regimentation means that a certain society is regimented in a way to promote disciplinarization of social and political behavior to be accommodated to the dominant rule, factors which contribute to this social regimentation can come from many origins (e.g. Confucian culture, militaristic confrontation with foreign country, a specific historical experience, a certain ideological situation). By the concept of ‘the anticommunist regimented society’, I want to imply that such regimentation in South Korea comes mainly from societal confrontation with communism, although many other factors were involved.

The formation and reproduction of the developmental regime in South Korea can not be fully analyzed without considering interactional influences of the Cold War and the civil war. In South Korea, the intense conflict after Independence in 1945, in which social forces were polarized into left-wing and right-wing groupings, developed into the civil war. This civil war ended up dividing the Korean peninsular into a capitalist-oriented ‘right-wing’ ‘region’ and a socialist-oriented ‘left-wing’ ‘region’ (South and North Korea).

What is important in the formation of ‘the anticommunist regimented society’ is that, in the process of the violent conflicts accompanying the civil war, oppositional figures and groups were widely removed from the public arena. Actually as a result of oppression by the American Occupation Forces and the South Korea government (together with impact of the civil war), the working class movement and popular opposition movement were nearly crushed. Only progovernmental right-wing organizations could exist without the threat of death or imprisonment. Such a civil war, and the hot confrontation between them, transformed the external logic of the Cold War into an internalized consensual one, which continued to regulate social and class relations.

The internalization of the Cold War logic was helped by the popular conception that the commitment of the US had been decisive for the survival of South Korea during the Korean War. If we say that the rise of the East Asian developmental state was born out of the ‘politics of survival’ (Castells 1992), the strongest evidence can be found in South Korea. In this situation, the confrontation between South Korea and North Korea was mechanically reproduced on its own without any regard to the origins of such a confrontation. What is unique to this situation is that such self-reproduction of confrontation was internalized to become a self-censoring mechanism. This anticommunist regimented society has been reproduced easily by the fact that the Civil War was not over, but stayed in truce. That is, this characteristic of ‘society in truce’ made possible the continual domestic reproduction of Cold War-like confrontation. In contemporary histories in South Korea, this situation has been systematically fortified by the purposeful efforts of the dominant group to preserve the logic of confrontation.

In this respect, ‘the anticommunist regimented society’ in postwar South Korea can be defined as one in which the Cold War logic was, through the historical experience of the civil war, transformed into an internally consensual one and it regulated social relations and behaviors of the populace, resulting in labor discipline and popular acquiescence.

The phenomenon, which emerged in the formation of the anticommunist regimented society, is that the old landlord class was weakened so as not to block the socio-political reorganization by the developmental regime. Ironically, the confrontation between the socialist North Korea and capitalist South Korea pushed South Korea to carry out relatively progressive land reform, thus weakening the landlord class.

Although the discontent and the demands for land reform by peasants functioned as a driving force for the passing and enforcement of the land reform law in the parliament, in which assemblypersons with landlord class background occupied a majority, the land reform was forwarded by the radical North Korea land reform and an experience of revolutionary land distribution during the civil war. Land reform ‘law was passed, but not one hectare was redistributed before the North Koreans occupied the South Korea in the summer of 1950: whence came a revolutionary dispossession in all but the “Pusan perimeter” holding area’ (Cumings 1989: 12).

The ‘quite progressive’ land reform, the erosion of the material base of the landlord class and the breakdown of the former landlord class as a dominant class with effective oppositional potential against pro-bourgeoisie modernization (Lie 1991: 71) were factors that made East Asian societies go on different routes from the most Latin American societies. Because the landed oligarchies can function as potent brakes on economic growth, removal of the landlord class is an important social condition for capitalist industrialization. It is the peculiarity of the East Asian Cold War (unlike Latin America) that it contributed to land reforms, weakening the landlord class as a result. Here we can see the dual impact of the Cold War confrontation: on the one hand it contributed to opposition movements being wiped out, and, on the other hand, it led to yhe demise of the landlord class. Only under these social conditions, could the developmental regime from the 1960s become possible. And only under these conditions could statist mobilization and authoritarian integration proceed without serious threat because, in the anticommunist regimented social condition, the socio-political barrier to statist mobilization and authoritarian integration has lowered.

The formation of the anticommunist regimented society brought with it the reversion of the power in capital–labor relation in favor of the former, and the reversion of the power in state–civil society relation in favor of the former. In such an anticommunist regimented society we can see a great imbalance between both the state and civil society and between capital and labor, facilitating both statist mobilization and authoritarian integration.

In a sense, capitalism depends on the regimentation and disciplinarization of labor to fit into capitalistic order: an organization of labor in an industrial army analogous to a military army. The developmental regime from the 1960s could integrate the working class to the new capitalistic order as well as stabilize capital’s domination over the labor process by extending the existing social regimentation and disciplinarization in anticommunist regimented society to the labor process.

What is emphasized here is that the anticommunism in this period has been very hostile to North Korea. This anticommunist regimentation was like regimentation based on the ‘pseudo-wartime’ control, in particular via creating a social atmosphere of threat in the name of national security.

Under the condition of the anticommunist regimented society, the Korean developmental regime went on to perform the statist mobilization and authoritarian integration from the early 1960s. The statist mobilization and authoritarian integration for growth happened in the following way. First, concerning the statist mobilization of the whole society towards growth, the state intervened to support export- oriented companies and give massive support to birth of new capitals. State intervention activities, directed to constructing capital itself and valorizing constructed capital, was economic on the one hand but also political and social on the other. The state exploited all possible policy measures to support export enterprises and the accumulation of capital. For describing this kind of the state’s role, Amsden used such expression as ‘getting the prices wrong’ (Amsden 1989: 139). However, I would use such expression as ‘getting all fundamentals wrong in favor of growth and export’. As is well known, it took the form of ‘industrialization drive policy’, especially ‘export drive policy’. For this, the state intervened in the form of one-sided allocation of all economic resources towards export (e.g. allocation of credits to targeted industries and infant industries). It led the market, not merely followed it, especially through ‘industry-specific’ policies (Wade 1990: 233–236). The state actively led a strategic allocation of socio-economic resources to targeted industries and enterprises.

The statist mobilization was also done in relation to the money capital circuit. The state gave export enterprises easy access to internal savings and foreign loans. In the name of the so-called ‘export-finance’, export enterprises could receive subsidies and favors in getting bank loans easier than other enterprises. The fact that the banking system has been under the state’s control made it easier for the state to channel the stream of credit in favor of export. In addition, the state supported the enterprises, especially big enterprises and public enterprises, to borrow money in the international financial market under the guarantee of the state to back up weak credit of the enterprises. In this sense, export enterprises could enjoy privileged status in access to both domestic savings and foreign loans.

However, the statist mobilization in favor of export-oriented industrialization extended beyond economic policy to ‘getting the whole society wrong’. Here we can indicate diverse ideological interventions to inculcate social norms that fitted with incipient capital accumulation and that promoted new identities in its favor. The state has been an important agent in reproducing social norms to encourage obedience to a new order of capital. It also reproduced behaviors in favor of accumulation (e.g. savings rather than consumption). In addition, it endorsed a certain identity of the individual as a provider of low-wage labor, a production element and a provider of capital in shortage through voluntary savings. The state also promoted a new identity in the image of a self-sacrificial hard-worker in high labor intensity industries, as a self-employed worker and as a self-dependent breadwinner with self-responsibility to the individual and family security, not dependent on the state etc.

In addition, the state intervened significantly in the reproduction of a low-wage labor system. The state played an active role in keeping low-wage labor power in potential surplus and making a certain level of skill sustained, especially through legislation, e.g. new labor laws, or detrimental revisions of existing labor law.

This statist mobilization was supported by authoritarian integration. The pre-existing legal institutions (e.g. the law such as National Security Law) were crucial to the state’s intervention in reproducing a stable production system based on low-wage labor, and suppressing the opposition to such a system. Compared to the 1960s when consensus was manufactured via the modernization project, the developmental regime in the 1970s tried to integrate the labor and whole society in the more authoritarian way. The Yushin regime in the 1970s was that of harsh authoritarian integration near to totalitarianism.

In summary, the developmental regime was based on the anticommunist regimentation. It means that anticommunism formed a kind of social basis for the South Korean developmental regime. In this sense, the developmental regime in South Korea can be called the ‘anticommunist’ developmental regime. This means that anticommunism and developmentalism were combined and interacted with each other in the South Korean context. In addition, if we look at its mode of operation, we can see it has operated in the way of maximal statist intervention (statist mobilization) and authoritarian integration. The maximal statist intervention and authoritarian integration were basic characteristics of the operational mode of the Korean developmental regime. In this sense, the South Korean developmental regime was a statist one on the one hand and an ‘authoritarian’ one on the other. In the South Korean regime, developmentalism was combined with statism and authoritarianism. Therefore, we can say that the developmental regime is an anticommunist, statist and authoritarian one, in that political and social reorganization of South Korean society towards a growth orientation was made possible by anticommunism and was reproduced in statist and authoritarian mode. In other words, the South Korean developmental regime is characterized as the regime of statist mobilization and authoritarian integration based on the anticommunist regimented society.

The regime of statist mobilization and authoritarian integration in the anticommunist regimented social context gets confronted with crisis with democratization.

Despite the comprehensive intervention of the state, helped by the anticommunist regimented social situation, a crisis of the developmental regime began to be manifested in the mid and late 1970s. In the early stage, especially during the so-called ‘economic take-off’, the situation of the anticommunist regimented society channeled people into the voluntary accommodation to the developmental regime and the development itself.

However, from the early 1970s, opposition to such a developmental regime (statist mobilization and authoritarian integration) began to expand. The weakening of the regimentation effect of the anticommunism contributed to a revival of oppositional struggles, specifically opposition to authoritarian integration of the working class. In addition, opposition to diverse intervention of the state in one-sided favor of capital expanded. Diverse struggles began to be manifested around such issues as increasing inequality, preferential treatment of big business, corruption, environmental degradation, harsh and long-term dictatorship, restriction of freedom, exploitation of women etc., all of which have looked before as if they had been necessary for development. Opposition to these situations activated diverse social struggles and developed increasingly into political struggles, which had been restrained in the first stage of economic take- off.

What should be pointed out here is that direct and deep involvement of the state in the reproduction of the developmental regime resulted in a ‘statization of struggles’. Struggles on various levels converged on the state, and had an implication of resistance against the state. This ‘statization of struggles’ gave a structural potential to the ‘statization of the crisis’, once struggles began to spread and develop.

Concretely, a disintegration of the developmental regime that existed hegemonically in the 1960s, began to take place in the 1970s. Contradictions in the industrialization process began to manifest themselves. The developmental regime started to show internal disintegration. Popular sector and oppositional activities and movements increased, and at the same time the developmental regime turned into a more rigid authoritarian regime in response to the deepening crisis. Accordingly, the previous developmental regime with a certain level of hegemony could not but transform itself to a ‘more repressive one’ that is a more authoritarian one. Ironically, it was the ‘successful’ growth that led to the creation of new social conditions for an internal rupture in the hegemonic order.

In South Korea, the developmental regime began to be confronted with serious conflict. This was because the all-out statist mobilization of the whole society for growth gave rise to a rapid industrialization, on the one hand, and more condensed structural contradictions on the other. Conflict originated from the structural condition that late industrialization by the developmental regime could not but relocate scarce resources into some targeted areas in extreme in equality in favor of the bourgeoisie in so short a time, and that it was inevitably accompanied by a higher alienation of the popular sector and more acute conflicts.

Opposition movements publicly began to crystallize, strengthening alliances in response to the deepening contradictions of the regime. The growth of the opposition and activation of the popular sector made the previous hegemonic status of the state impossible to preserve. As a result, statist mobilization could only be obtained coercively through external repression, in the authoritarian way. With the intensification and expansion of opposition movements, the hegemonic incorporation of the popular sector to the developmental regime, with the help of the anticommunist regimentation, which made possible the predominance of the state over the society, began to change. This provided a fertile condition for opposition alliances to develop more manifestly and with greater organization.

This meant that the developmental regime hasn’t been able to sustain itself politically. The opposition alliance, called ‘Minjung movement’, which began to be crystallized in the 1970s and existed only as a loose horizontal network, developed into a more organized form in the 1980s. We can say that in the 1960s the developmental regime was still ‘hegemonic’, but in the 1970s it began to disintegrate, although it did not break down fundamentally. However, in the 1980s there was an oppositional alliance that was sufficiently developed to engage in ‘strategic interactions’ (Cheng and Kim 1994: 127–128). Such a development of the opposition necessitated the democratic change of the former developmental regime. It meant that the South Korean society entered the road of the democratic transition.

The important issue in the democratic transition is whether the transition occurs from the top-down in a conservative way under the initiative of the previous developmental alliance, or from bottom-up in a radical way under the initiative of the oppositional alliance (Cho 1998: 60–82). The process of political change until now shows that so far South Korea’s experience belongs to the former form of transition. Even though the anticommunist regimented society and the developmental regime faced a major crisis, the oppositional alliance could not overcome it in a revolutionary way, and it was unable to dismantle the repressive state structure or to disrupt its dominant agencies. Therefore, oppositional forces had a limited leverage in rearranging the regime in its own way. In brief, political democratization during this period proceeded as a conservative democratization from above. In the conservative democratization from above, the developmental regime of statist mobilization and authoritarian integration undergoes a compromise-like transformation.

The issue here is whether the problems and contradictions of the developmental regime can be reformed in the democratic transition or not.

First, let’s see the economic structural problems of the developmental regime. East Asian economic growth theories, including the developmental state theory, were based on the expectation of continual successful economic growth in East Asia. However, the sudden economic crisis, including the IMF’s relief finance to South Korea, turned many scholars to consider the reality of East Asia from the point of view of crisis. Some scholars argue that the causes of the crisis are different from those of successful growth, and so try to find some unique factors to contribute to crisis. In my opinion, successful growth and economic crisis are different sides of the one coin. In my view, factors that contributed to growth, have converted to be causes of crisis, when they fell into the inertia of degradation and corruption. The problems that drove the South Korean economy into crisis should be regarded as inherent to statist mobilization and to the authoritarian integration regime.

The aforementioned regime of statist mobilization is characterized by the comprehensive role of the state in raising and allocating economic resources and concentrating those resources in a few selected areas and companies. A kind of selectivity in this state role has existed. In this mobilization and allocation, special relations were formed among the government bureaucrats, big companies, banks and other actors concerned. In the early rapid economic growth, this special relationship could save the ‘transaction costs’ among different economic actors. During that period, the special relationship has been a trade-off relation of subsidy on the side of the government, and economic performance on the side of capital (Johnson 1987; Weiss and Hobson 1995). A kind of tension between capital and government was there.

However, as the developmental regime degraded to become a long-term dictatorship, more authoritarian and politically more unstable, such a relation became a relation of political trade of corrupt political funds and economic subsidy. The government bureaucrats and politicians gave some companies economic preference, including banking loans, and the latter gave, in return, political slush money to the former. Here we can see the so-called ‘crony’ capitalism or ‘corrupt’ capitalism, which means the distorted, irrational relation among government, banks, entrepreneurs and so on. In the process of growth, this distorted relation has been more fixed and structured.

The special relation between the government and business has been expressed more seriously between the government and Chaebol. Through this collusion, the Chaebol could get favored access to the financial resources under the state’s control, while politicians and bureaucrats could get access to political slush funds. A kind of closed circuit of corruption has been formed and reproduced.

Under this structured relation, big companies, especially Chaebol, could perform overinvestment and ‘overdiffused’ investment in unrelated areas. The Chaebol’s monopolistic position in the distribution of credit has strengthened its monopolistic position in the market. In this structure, Chaebol could try debtridden diversification and expansion (Kim 1997). This is also connected to the poor and ineffectual management of banks. Chaebol’s expansion-oriented management and the poor management of the banks reproduced each other. In this sense, the ‘crony’ relation which might have contributed to economic growth in the early stage, but transformed to its opposite, thus a fertile ground for economic crisis.

In order to explain this transformation, we should indicate that the statist mobilization and authoritarian integration which have been effective in organizing rapid economic growth have also been effective in repressing the counter-forces against the subsequent degradation of the growth-oriented regime. In a one- sided growth-oriented society, it is very difficult to develop checking systems. Due to this, the economy, which rushed to rapid economic growth, rushed to rapid economic crisis too.

These kinds of problems have been expressed, in concentrated form, in Chaebol. In South Korea, where there has been a strong big-business bias in statist mobilization and in the allocation of resources, the problems became more serious and threatened the South Korean economy, when debunked. In South Korea, in which the policy bias was in favor of big companies, Chaebol continued to be strong and the monopolistic economic power of Chaebol has been greater than in any other economies, with the result that it brought a greater and more sudden crisis to South Korean economy.

The theoretical point here is that the simple distinction between the predatory and developmental state (Evans 1995: 43–50) does not make sense. In a sense, we have to talk about the ‘predatory’ characteristics of the ‘developmental’ state (Cho 1998: 53–58). The close connection itself among the government bureaucrats, entrepreneurs, banks and politicians, formed by the successful intervention of the state in mobilization and allocation of resources itself, could be inherently corrupt and always have the potential for such distorted relation. In reality, the South Korean state has been a developmental one, on the one hand, and on the other, a state degraded to be a predatory, even rent-seeking, one. It is exemplified by the fact that former president Roh Tae-Woo collected as much as 600 million dollars in slush money from the big companies.

If there had been a checking system or countervailing power backing it, a certain level of the developmental regime could not be so easily reverted to a predatory one. Although there has been much critique and opposition against collusion among political and economic elites, this democratic reform or breakdown of such a collusion was not accepted by government bureaucrats as a reform agenda. As a result, the regime of statist mobilization and authoritarian integration, especially the Chaebol system, has been reproduced in inertia without the chance of reform.

The great imbalance between the state and civil society and between capital and labor, which enabled the functioning of the statist mobilization, prevented the development and institutionalization of the countervailing system against the degradation of the close relation among the main economic actors. We cannot find causes of successful growth and crisis separately. The causes of growth themselves are also ones of crisis. In this sense, we can say that the developmental regime of high growth is also one of potentially high crisis.

Confronted already with the development of the political opposition movement, the developmental regime couldn’t but change to a post-developmental regime, precipitated by its economic crisis.

Therefore, we can say that the ‘old’ developmental regime has changed to a ‘new’ one, that is, a ‘neo-developmental regime’, in the wake of democratization from the 1980s on, and economic crisis in the mid-1990s. This new regime has different characteristics from the old one in many aspects.

First, this developmental regime is new in that it has a democratic political form, changing its former authoritarian character. It can be said to be a ‘democratic’ neo-developmental regime.

The way in which a developmental regime is transformed might be different between countries, depending on the class relations, power relations and the type of democratization. The momentum of transformation for the South Korean developmental regime was created by the June democratic uprising in 1987. The military authoritarian government led by Chun Doo-Whan, which symbolized the anticommunist, statist and authoritarian developmental regime was confronted with people’s strong opposition from the mid 1980s. As I mentioned, this critical political period saw the emergence of ‘the conservative democratization from above’ over ‘the radical democratization from below’, by way of division of the opposition forces, including opposition parties and dissident camps. After this, the South Korean developmental regime began to transform itself following the road of the conservative democratization from above.

While the struggle before 1987, which was characterized by the retreat of the military authoritarian government, aimed at the possible transformation of the developmental regime itself, the struggle after 1987 has developed around the direction of the transformation, i.e. whether the regime’s reform is of any substance. With the retreat of the military authoritarian government in 1987, and the emergence of civilian government in 1993 (Kim Yong Sam’s government) and an oppositional party government in 1998 (Kim Dae Jung’s government), the ‘authoritarian’ developmental regime has changed increasingly to a ‘democratic’ developmental regime. People can now see a civilian-ele cted government rather than the past authoritarian ‘un-elected’ government.

In this process, the authoritarian integration has changed to the democratic. Under the democratic regime, social movements could enjoy relatively autonomous arenas of activities. Under the past one, there was exclusive repression of the institutional political arena and civil society by the authoritarian regime. The change has made it possible for diverse social groups to organize themselves and express their demands openly without fear of persecution. The people’s movement could strengthen itself politically and organizationally. At the same time, the so-called citizens’ movements expanded to include new areas with new issues. This was an important context, for the shift from authoritarian to democratic integration.

This political change means that the political form of the developmental regime has changed from an authoritarian to a democratic one. We can say that there is a ‘democratic’ neo-developmental regime after 1987. As said earlier, the South Korean regime has diverse aspects: statist, authoritarian, anticommunist, develomentalist. Although the ‘authoritarian’ character itself is one aspect of the reality of the developmental regime, the opposition of people to the regime focused on such political aspects as its authoritarian and dictatorial characteristics. The sharp opposition to the ‘authoritarian’ aspect of the developmental regime could develop into radical opposition to the developmental regime itself. The main thrust of opposition movement in the 1960s and 1970s was to criticize the long reign of the dictator, Park Chung-hee. However, the opposition movement in the 1980s had a radical orientation whose militant aim was to overcome the developmental regime itself.

This radicalization of the opposition was because of the increasing hardening of the authoritarian regime and the degradation of the regime to fascistic dictatorship. This ‘revolutionization’ ironically precipitated the transformation of the authoritarian regime to the democratic one.

Second, the neo-developmental regime should be defined as a ‘neoliberal’ one. The former statist character of the regime has transformed itself, as development proceeded. Statist mobilization meant that the state could keep a very strong state initiative in economic decision making, and that the state could ‘mobilize’ the population in a certain direction for development. The former was expressed in such phenomena as the economic planning agency playing the authoritative role over the individual entrepreneur or collective capitalist enterprises. A good example of the latter can be found in the ‘New Village Movement’, which mobilized people, especially rural people, to renovate rural residential space and encouraged people to be committed to hard work. However, this type of statist mobilization was in effect no longer valid. It is because such a way of statist mobilization became increasingly perceived as out-of-date to the general population. Although a kind of ‘state corporatist’ organization in charge of such a mobilization, e.g. the Korean Samaeul-Undong Center (Association for the New Village Movement organization), still existed, it was not what it used to be.

In the pressure to change, state initiatives in the economy changed in the following way. First of all, business acquired more initiative in economic decision making and the relation between the business and the state became that of a ‘collaborative symbiosis’ rather than a ‘hierarchical one’ (Cho and Kim 1998: 152). The important characteristic of the statist mobilization was comprehensive intervention in business and the strong role of the state bureaucrat in economic decision making. Before, the state acted in a ‘dirigiste’ way in economic life. Economic decision-making policy in this one-side way has weakened, and the market and corporate sector, or capital in the broad sense, came to enjoy more autonomy. Collaboration and consultation now characterize the relation between business and the state (Doner 1992).

In addition, the decrease in state initiative is also seen in a much greater privatization of state- owned enterprises, which has been happening from the 1980s. In this aspect, global neoliberalism makes a favorable environment for a decrease in state initiative in the economy. In its early stage, the Chun Doo-Whan’s government adopted both a privatization policy and a policy that opened South Korea to the global economy as an exit from the stalemate of the heavy-chemical industries in the late 1970s. Until the 1970s, the South Korean economy developed in a relatively closed environment, in which the domestic market was protected from the entry of foreign capital with the help of the ‘umbrella of the Cold War’ (Arrighi, 1996). The combination of the increase of the foreign debt and pressure for opening of the domestic market from abroad pushed Chun’s government to open the economy, and, as a result, incorporation into the global economy proceeded rapidly. In this sense, we can say that the ‘neo-developmental regime’ is a neoliberal one.

This transformation of the ‘old’ developmental regime has been encouraged by neoliberal globalization stream, the dominance of which comes from diverse factors such as breakdown of socialism, rapid progress of information and telecommunication revolution and so on. Its core momentum is transnationalization of the capital movement, intensification of competition between businesses and, as a result, the national state is necessitated to adopt a new market-friendly policy and a new growth-encouraging policy (Cho, 2000: 164).

What is interesting is that civilian government, relatively free from the political burden of dictatorship, becomes a strong engine for a new developmentalism. The former authoritarian government lacked political legitimacy and popular support and has been, ironically, constrained to adopt the strong developmental drive in its late stage. Under the authoritarian regime, dictatorship and developmentalism were combined and perceived as the same. However, the Kim Yong- Sam’s government was the first civilian-elected one, and so was not beset by political legitimacy issues. Because of this, the first civilian government could adopt a new growth-oriented economic policy strongly under the banner of ‘strengthening the international competitiveness’. After it enforced a few anti-authoritarian political actions, including dismissing the former political military elite and taking corrupt politicians and public officials to court and so on, during the early stage (the year 1993–1994), it moved to enforce strong developmental policy packages. While the former economic policies were oriented towards supporting the incipient industries and helping business settle down, now they are oriented towards supplementing weak international competitiveness and providing the infrastructure and so on.

The aforementioned economic crisis and emergence of the opposition party government, the Kim Dae-Jung’s government, has not contributed to reflection on, or fundamental change of, the developmental regime. Rather it has led to a new refreshment of the old developmental regime. The Kim Dae-Jung’s government adopted policies aimed at a democratic reform of the old developmental regime, including reform of Chaebol, and, at the same time, enforced new developmentalist economic policies in the name of overcoming economic crisis and reconstructing a new successful ‘trade state’.

This new developmental inclination was made possible by the separation of ‘politics’ and ‘economy’ that is the ‘authoritarian’ politics and ‘growth-oriented’ economic policies. The change from ‘authoritarian’ regime to ‘democratic’ one has weakened the dispute over the developmentalist character of the regime, and, as a result, political opposition to such a character has weakened. The civilian-elected government, free from controversy over political legitimacy, adopted neoliberal economic policies quite radically and such policies were met with a low degree of opposition. This curious combination of ‘democratic’ regime and neo-developmentalist economic policies, that is, promotion of the latter by the former, is exactly what the policy of so-called ‘low-intensity democracy’ strategy aimed (Graf 1995).

Third, however, this change does not mean that the state initiative has disappeared. Certain room for maneuver for the state can exist. For example, the Keynesian welfare state can move to purely neoliberal type of the state, or neocorporatist, or neostatist one (Peck 1996) under the influence of the global neoliberalism. The South Korean state moved towards a ‘soft’ statist type. It is a transformation of developmental regime, rather than overcoming the developmental regime. In South Korea, the neoliberal character of the state’s activities and strong neostatist intervention is ironically combined.

The combination of the new soft type of statist intervention and market-friendly developmentalism survives intact. In South Korea, the success of the president’s performance is evaluated still in terms of the economic growth rate. The state initiative functions strongly in a way to support the business activities in a different way intervening with the supply-side management by promoting innovation in product, process organization, market and so on. This state initiative is performed mainly in order to ‘coordinate’ the diverse economic activities and areas. Although the state initiative in such areas as the past ‘micro’ control of the economy and guidance of the market has weakened, such macro areas as making of rules for the new business area, selecting the macroeconomic guideline and so on, still exist intact. If the state initiative under the old developmental regime has been a kind of ‘mobilizational’ in the more vertical way, that under the new one is a kind of ‘coordinational’ in the more horizontal way.

This coordination role is necessitated by changes brought by globalization and informatization. The globalization and informatization bring with them new economic activities and new relations in new areas (e.g. electronic business). Therefore we can say that the state holds its initiative in a new ‘coordination’ role such as coordinating relations between new economic actors, making a new regulatory rule and channeling certain economic actors to new areas. The state plays still a vital role in ‘the domestic mediation of international challenges’ (Weiss and Hobson 1995: 187). In this sense, the state initiative in the form of mobilization has weakened, but its role in coordination or economic governance is still strong. Moreover, the state in South Korea is still playing an important role in amplifying the infrastructural base for development. This infrastructural base includes even the informational one. The state intervenes in encouraging and supporting innovation in supply side such as production process, technology (Jessop 1994: 263–264) and so on.

In addition to this general economic situation, the economic crisis in the late 1990s contributed to preserving state initiative. During the economic crisis, such urgent tasks as reforming big business (Chaebol), restructuring financial industries including banks, made the state initiative even stronger than before. In the process of the economic reform, the statist characteristic of the South Korean developmental regime was not considered a serious problem. The economic crisis was viewed as typical of ‘market failure’ and the moral hazards of big business, and so ‘state failure’ was overshadowed. The emergence of the first opposition party government in 50 years has given the general public a new expectation for the state initiative in removing the market failure and moral hazards of the Chaebol. Because of this, the state could keep its initiative in the form of state coordination in relation to business. What is more important is that the class character of the state did not change at all and the market-friendly intervention of the state in the economy continued to be the main characteristic of the state activities, although the ‘pro-business’ intervention was counterbalanced by the class and social struggles. For example, the 4 River Development Project of the Lee Myung-bak government, which amounts to more than 20 billion US dollars, can be an example of recovery of state initiative in the quite old form. In this sense, I would say that the neo-developmental regime is a kind of ‘soft’ statist type of neoliberal one.

Based on this discussion, we can say that the ‘old’ developmental regime has changed into a neo-developmental one. This is different from the former regime in that it takes a political form of democratic regime, based on democratic integration. However, it continues to keep the state initiative in a new ‘soft’ form’ in such a way to coordinate the economy and intervening in the economy in the market-friendly way. However, the neo-developmental regime has not obtained a stable basis for public consensus. The struggle against the multi-faceted destructiveness of the neo-developmental regime is dynamically still underway even under the so-called ‘neo-conservative’ Lee-Myung-bak government (Cho 2008).

Amsden, Alice. 1989. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization, NY: Oxford University Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni. 1996. ‘The Rise of East Asia: World Systemic and Regional Aspects’, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 16(7).

Bonefeld, Werner. 1987. ‘Reformulation of State Theory’, Capital and Class 33.

Castells, Manuel. 1992. ‘Four Tigers with a Dragon Head: A Comparative Analysis of the State, Economy and Society in the East Asian Pacific Rim’, in R. Appelbaum and J. Henderson eds, States and Development in the Asian Pacific Rim, London: Sage Publications.

Cheng, Tun-jen and Eun Mee Kim. 1994. ‘Making Democracy: Generalizing the South Korean Case’, in Edward Friedman, ed., The Politics of Democratization: Generalizing East Asian Experiences, Boulder: Westview Press.

Cho, Hee-Yeon. 1998. The State, Democracy and the Political Change in South Korea, Seoul: Dangdae.

Cho, Hee-Yeon. 2000. ‘Civic Action for Global Democracy: A Response to neo-liberal globalization’, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 1(1).

Cho, Hee-Yeon and Eun Mee Kim. 1998. ‘State Autonomy and its Social Conditions for Economic Development in South Korea and Taiwan’, in Eun Mee Kim ed., The Four Asian Tigers: Economic Development and the Global Political Economy, San Diego: Academic Press.

Chu, Yin-wah. 2009. ‘Eclipse or Reconfigured? South Korea’s Developmental State and Challenges of the Global Knowledge Economy’, Economy and Society 38(2).

Cumings, Bruce. 1989. ‘The Abortive Abertura: South Korea in the Light of Latin American Experience’, New Left Review 173(January/February).

Doner, Richard F. 1992. ‘Limits of State Strength: Toward an Institutionalist View of Economic Development’, World Politics 44(3).

Evans, Peter. 1995. Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gereffi, Gary and Donald L. Wyman. 1990. Manufacturing Miracles: Paths of Industrialization in Latin America and East Asia, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Graf, William. 1995. ‘The State in the Third World’, Socialist Register, London: Merlin Press.

Jessop, Bob. 1994. ‘Post-Fordism and the State’, in Ash Amin ed., Post-Fordism: A Reader, Oxford: Blackwell.

Johnson, Chalmers. 1987. ‘Political Institutions and Economic Performance: The Government–Business Relationship in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan’, in Frederic Deyo ed., The Political Economy of the New Asian Industrialism, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Johnson, Chalmers. 1999. ‘The Developmental State: Odyssey of a Concept’, in Meredith Woo-Cumings ed., The Developmental State, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kim, Eun Mee. 1997. Big Business, Strong State: Collusion and Conflict in South Korean Development, 1960–1990, Albany: State University of New York Press.

Lie, John. 1991. ‘Review: Rethinking the “Miracle”-Economic Growth and Political Struggle in South Korea’, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Studies 23(4).

Peck, Jamie. 1996. Workplace: The Social Regulation of Labor Markets, New York: Guilford Press.

Perkins, Dwight H. 1994. ‘There are at least Three Models of East Asian Development’, World Development 22(4).

Wade, Robert. 1990. ‘Industrial Policy in East Asia: Does it Lead or Follow the Market?’ in Gary Gereffi and Donald L. Wyman eds, Manufacturing Miracles: Paths of Industrialization in Latin America and East Asia, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Weiss, Linda and John M. Hobson. 1995. States and Economic Development: A Comparative Historical Analysis, Cambridge: Polity Press.

World Bank. 1993. The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.