A new wave in the social movements of Korea

Jinsun Lee

South Korea now leads the world in terms of Internet use, with 77.8 percent of the population identified as Internet users (KISA and KCC, 2010). Based on highly developed technological infrastructures, the Internet has been broadly used for progressive and oppositional civic actions and political campaigns in Korea since the 1990s. While a number of previous studies have analyzed the political uses of the Internet, most tend to focus more on the Internet as a “tool” of mobilization mainly adopted by “established institutions,” including social movement organizations (SMOs) and political parties. But this tendency will likely to fail to explain new, significant phenomena arising in Internet-based activism fields.

Recent years have witnessed individual Internet users who, neither mediated nor mobilized by any specific political organizations, are increasingly involved in social movements. As Earl and Schussman (2003) assert, new media technologies have reduced the incentives of established activist groups, such as social movement organizations, allowing “movement entrepreneurs” to emerge as new agencies who act outside the framework of institutions. Movement entrepreneurs are defined as non-professional individuals “who are motivated by individual grievances to undertake social movement activity and who rely on their own skills to conduct their actions” (Garrett, 2006, p. 211). As individual actors emerge, new technologies affect the internal structures of social movements, particularly structures relating to decision making and leadership. In lieu of organizational membership and hierarchical leadership, ad hoc and discretionary decision making and horizontal leadership become paramount in this new mode of activism. These changes, in turn, inspire citizen participants to foster alternative political ideals influenced by the logic of peer-to-peer networking and decentralized nomadism (Juris, 2005).

This study approaches current social movements in Korea through the framework of the netizen movement. Netizens – most of whom maintain independence from institutionalized political groups, such as social movement organizations, labor unions, and political parties – have broken new ground of civic activism in Korea. This chapter delineates the historical context in which the Internet and new media have been adapted to progressive and oppositional civic actions, and furthermore examines the ways in which these new forms of civic action have reshaped the political and social landscape of Korea.

The neologism “netizen,” a compound word of “Internet” and “citizen,” broadly refers to “people who use the Internet for a certain purpose” (Lee Byoungkwan et al., 2005). The definition of netizen, however, should be reconsidered in and tailored to specific cultural contexts. Hauben and Hauben (1997), who coined the term in their study on the impact of Usenet in the US, identified netizens as net users who are empowered by collecting, creating, and sharing information and knowledge with others, and who, at a grassroots level, help make the world a better place. In their view, the net – including Usenet, Free- Net, email, electronic newsletter, and the World Wide Web – is a “grand intellectual and social commune,” which anybody on the globe can access “to improve the quality of human life” (p. 3). Their view, however, tends to overemphasize the technological advantages of the net, neglecting what helps to situate, create, and develop the online citizenship of Internet users in specific historical and political context. To understand the varying meanings of the netizen, which may differ under relativistic conditions, one should examine the political and historical background where online citizenship is constructed.

In Korea, the netizen has diverse connotations. By netizens, some people refer to Internet-based protesters that are radical, “irresponsible, and inadvertent” (Lee Y., 2005). For others, netizens represent “reform-minded and participatory Internet users who have reshaped journalism and politics for the better” (Oh, 2004). This study defines netizens as amorphous and hybrid groups of Internet users who are aware of citizenship, participating in a variety of collective action in horizontally networked forms. In particular, this research focuses on Korean net-izens who autonomously participate in collective action, independently from institutionalized activist groups like SMOs and labor unions, and who have introduced innovative forms of movement repertoires in Korean social movements.

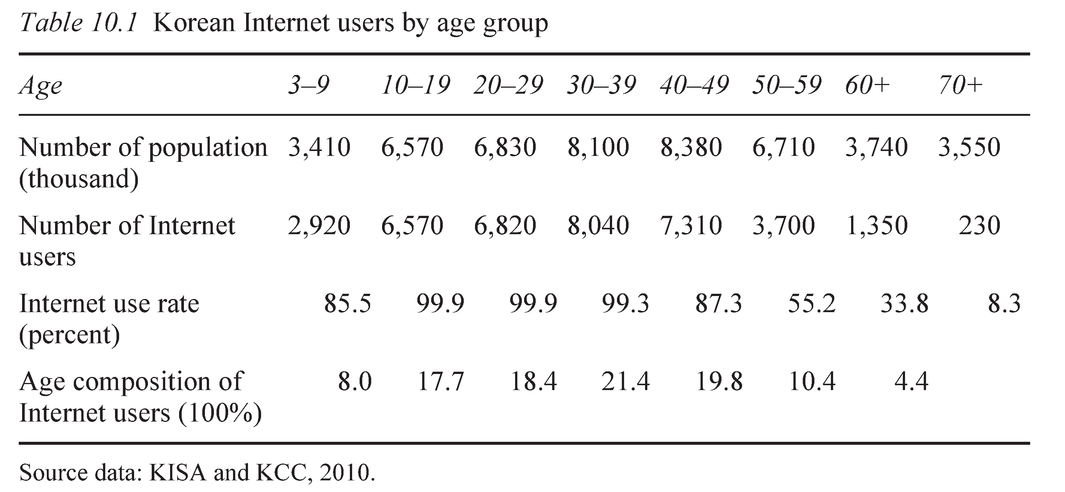

As of May 2010, 77.8 percent (approximately 37 million people) of the Korean population aged three or over are using the Internet (KISA and KCC, 2010). According to the demographic data measuring the age of Internet users, the largest age segment that uses the Internet comprises citizens in their 30s, followed by those in their 40s (Table 10.1).

While almost all of those in their teens and 20s (99.7 percent) and most of those in their 30s and 40s (90.2 percent) use the Internet, Internet usage rate in the

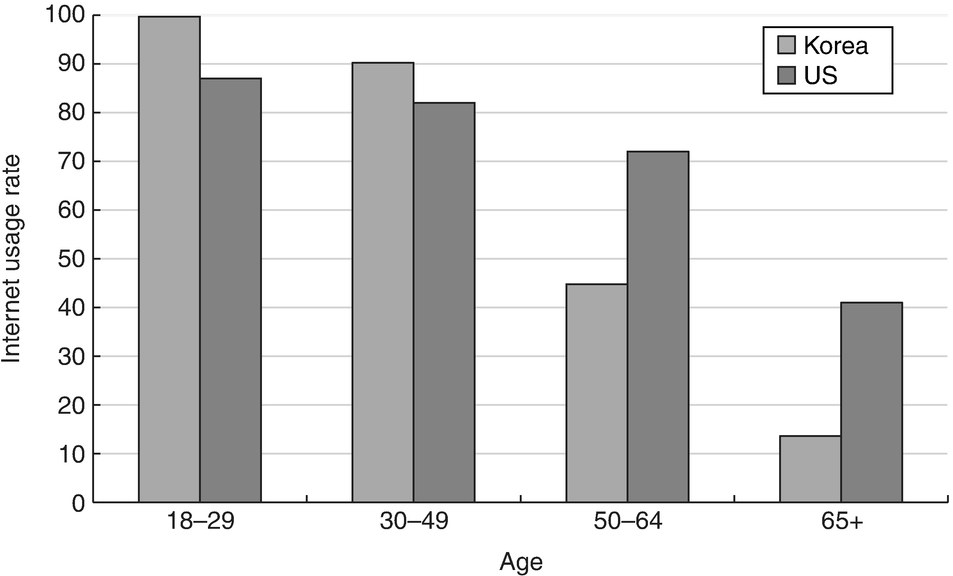

older generations (50 and over) abruptly declines: 44.8 percent in the ages 50–64, and 13.6 percent in the ages 65 and over. The 30–39 age segment accounts for 21.4 percent of Internet users, and the 40–49 segment accounts for 19.8 percent. Though in most countries the younger generation more actively uses the Internet, the age gap is more remarkable in Korea.1 For instance, a comparative study of Korean and American Internet users (NIDA, 2009) reveals that more young Koreans use the Internet than do young Americans (Figure 10.1). This finding implies that Koreans in the 30–49 age group play a more predominant role in shaping public opinion on the Internet than do the 50-and-over demographic.

On average, Korean Internet users stay online 14.7 hours weekly (KISA and KCC, 2010). With respect to the purpose of their Internet use, over 90 percent of users go online for gathering information or data (91.6 percent), for leisure

Figure 10.1 Koreans’ and Americans’ Internet usage by age (source: NIDA, 2009).

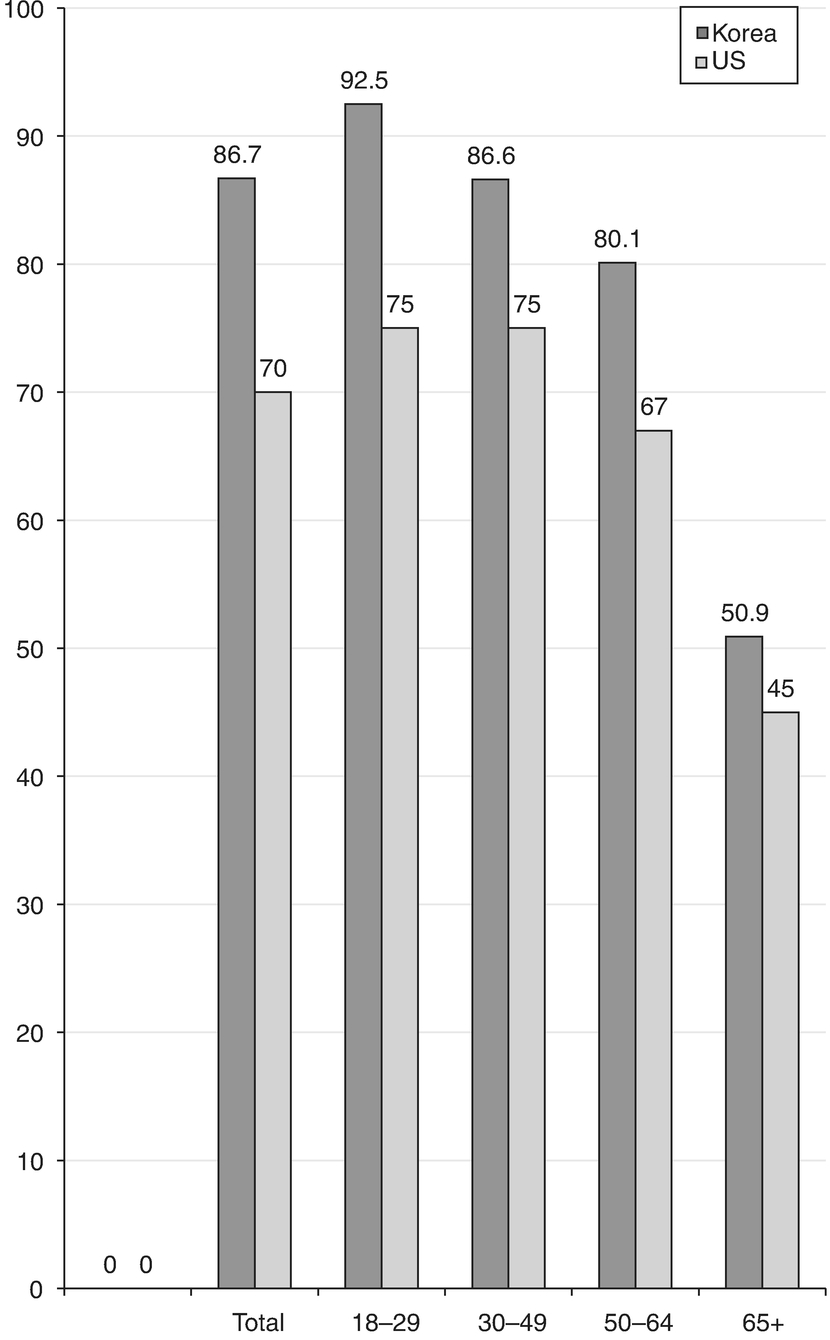

activities (89.1 percent), such as the consumption of music, games, and videos, and for emails and instant messengers (88.4 percent). Compared to US users, Koreans use the net less actively for online shopping and banking2 and more actively for reading online news (NIDA, 2009). An average of 86.7 percent of Korean users aged 18 and over read news online, which is higher than 70 percent of US users (Figure 10.2). In understanding the netizens’ actions in Korea, it is

Figure 10.2 Internet use for reading online news (source: NIDA, 2009).

noteworthy that: (1) those in their 30s and 40s constitute two major netizen groups; (2) those aged 50 and over are far less likely to be netizens; and, (3) Koreans actively use the net for information seeking and news reading.

By the netizen movement,3 this study refers to social movements mobilized and coordinated online or offline mainly by netizens. Since the pioneering use of the Internet in the Zapatista movement in the mid-1990s and the Seattle anti-WTO protest in 1999, social scientists have been paying increasing attention to the Internet’s impact on civic action at the global, national, and local level (Bennett, 2004; Bimber et al., 2005; Carroll and Hackett, 2006; Kahn and Kellner, 2004). While some scholars focus on the effectiveness of the Internet from the theoretical perspective of resource mobilization (Kahn and Kellner, 2004, 2005; Vegh, 2003), others identify the Internet, from the framework of new social movements, as a postmodern field of action where spontaneous participants seek to subvert dominant meaning and knowledge and rearticulate their identities (Froehling, 1997; Lievrouw, 2011; Poster, 1995; Van Aelst and Walgrave, 2004). Despite different theoretical approaches, many scholars agree that traditional theories do not fully take into account the main aspects of contemporary social movements, as Internet- based movements have fundamentally distinct features in agency, movement repertoires,4 and organizational forms of action (Bimber et al., 2005; Chadwick, 2005, 2007; Flanagin et al., 2006; Froehling, 1997).

Borrowing McLuhan’s famous the “medium is the message” thesis, Chadwick (2007) asserts that Internet-mediated communication substantially restructures not only movement repertoires but organizational values and ideological goals. Focusing on emerging forms of Internet-based communications, Chadwick characterizes digital network repertoires according to four principles: (1) creating convergent forms of online–offline action; (2) fostering “distributed trust,” or people’s tendency to trust the outcomes of collective decisions made on horizontal and leaderless networks more than claims produced by single, authoritative information sources; (3) fusing sub-cultural and political discourses; and (4) constructing “sedimentary online networks,” by which Internet-enabled protests can exist in the long term through loose but integrated communication infrastructures that reconfigure civic action in response to new demands.

Drawing on Chadwick’s framework, this study discusses the emergence of Korean netizens as newly rising movement actors who have pioneered changes in movement repertoires. Unlike Chadwick’s model, which addresses how SMOs innovate movement repertoires in the “national context of the contemporary US” (2005, p. 3), the Korean case demonstrates netizens’ predominant role in leading a new wave of collective action independent from conventional social movements. Providing an overview of a series of Internet-fueled civic campaigns since the 1990s, this section describes three historical stages in the netizen movement: (1) the formation of the netizen movement (1990–2000); (2) the evolution of the netizen movement (2000–2007), and (3) netizen-dominated social movements (2008 to present).

In the initial phase of the netizen movement, online networks began to emerge as alternative spaces in which radical and progressive users publicized social issues and organized their collective actions. As “PC tongsin” [Personal Computer Communication], computer-mediated networks that existed prior to the Internet, first emerged in the late 1980s,5 progressive college students and white-collar workers first adopted new technologies (Kim Gibo, 2006). The first indication of the netizen movement is found in the organization of “Bar-Tong-Mo”6 [The meetings for good communications] in November 1990.7 About 200 netizens declared the democratic mission of Bar-Tong-Mo:

Bar- Tong-Mo is an association of independent online users gathered to solve the problems in cyberspace ... Based on a culture of right-thinking communication, we, the members of Bar-Tong-Mo, aim to develop our knowledge and information about society and technology. We will also strive to solve the problems of cyberspace by proposing democratic alternatives and solutions. We will construct spaces open to everybody to expand the democratic power of online communicators.

(Min, 2002, p. 102)

Before long, Bar-Tong-Mo became a hub of progressive activists online. On the one hand, it embarked on the “consumer movement” to improve online service of IT companies and to extend freedom of expression. It successfully directed, for instance, the protest against an unexpected suspension of network services for the “Hitel [enamed from Ketel] User Association,” opposing Ketel’s arbitrary deletion of users’ postings and online censorship (Choi Se-jin, 2006; Min, 2002). On the other hand, Bar-Tong-Mo promoted “progressive social movements,” mobilizing support for political campaigns and petitions online and offline. In the presidential election of 1992, it dispatched its members to ballot- counting offices to monitor the counting processes and prevent the rigged election some had anticipated. The ballot-counting processes were reported online in real time and were compared with government reports by election management officials. From the beginning of the netizen movement, online–offline convergence of action was routine.

Among the most notable changes introduced by Bar-Tong-Mo was the adoption of non-hierarchical styles of communication. Bar-Tong-Mo recommended that netizens keep “netiquette” (net etiquette), which includes the usage of “Nim,” an honorific suffix, in addressing the online parties with whom one is communicating. In a Korean society where honorific expressions had been traditionally reserved for respected elders, the designation of online acquaintances with Nim – regardless of age, gender, and social status – was a pioneering action that promoted non-hierarchical and horizontal relationships among all online users. It is also notable that PC tongsin members were asked to avoid the specialist, elitist, leftist, and/or Marxist jargon that had been frequently used among activist groups. In the previous generation, when Marxist jargon was customary, radical or progressive activists were collectively called “Un-dong-kwon [an activist circle],” which might give the impression of exclusivity and self-centeredness. Some terms common in critical social science – such as mass, hegemony, propaganda, and anti-these – as well as some abbreviated words – like PD (people’s democracy) or NL (national liberation)8 – became signifiers of whether the speaker was Un-dong-kwon, and even of what ideological faction he or she belonged to (Kim Gibo, 2006). Aiming to share open discussions with anybody who might have different opinions – whether Un-dong-kwon or a layperson, PD or NL – the online community members agreed to restrict the use of factionalist language.

Following Bar-Tong-Mo on the Ketel (Hitel) site, many communities, such as Hyn-Chul-Yeon (Hyndai-Chulhak-Donghohwe [Modern Philosophy Forum]) on Chollian and Chan-Woo-Mul [Cold Springs] on Naunuri, were established, pursuing progressive social reform and online freedom of speech (Table 10.2). Although the number of online participants was fewer than one million until 1995, these incipient online communities pioneered the netizen movement in Korea.

As the Internet’s popularity soared in late 1990s, preexisting SMOs – including college student associations, labor unions, and civic activist organizations – rushed to adopt new media technologies for more effective resource mobilization. Many SMOs began to create “Closed User Groups” (CUGs) to share information among their members and launched homepages to promote

Table 10.2 Online activist communities in the 1990s

| Network server | Online communities | Political orientations |

|---|---|---|

| Hitel (formerly Ketel) | Bar-Tong-Mo [Meetings for good communications] Daejoong-Maeche-Monitoring-Donghohwe [Media Monitoring Club] Tonghap-Kwahak [Integrated Science] |

Social reform, speech freedom Media reform Progressive usage of IT science |

| Chollian | Hyun-Chul-Yeon [Modern Philosophy Forum] Hee-Mang-Ter [Places of Hope] |

Radical social reform Moderate social change |

| Naunuri | Chan-Woo-Mul [Cold Springs] Jinbo-Chungnyun-Donghohwe [Progressive Youths] Mae-Ah-Ri [Echo] |

Moderate social change Radical social reform Moderate social reform |

citizens’ participation.9 Three months before the General Election of 2000, approximately 500 Korean SMOs inaugurated a civic alliance named “Citizens’ Solidarity for the General Election” (CSGE).10 Pleading with voters and political parties to neither nominate nor support corrupt or unethical candidates, CSGE announced a blacklist of 86 candidates, regardless of their political party or affiliation. These CSGE Election Defeat Campaigns were greatly successful: 68.6 percent of the candidates on the blacklist were defeated in the election (Min, 2002). Surprised by citizens’ fervor for and active involvement in the campaigns, some commentators called the success of the Election Defeat Campaigns an “electoral revolution” or “the second June Civil Uprising” (Choi Jang-jip, 2000). The decisive factors of this success include effective utilization of the Internet and the flexible combination of online and offline campaigns (Choi Jang-jip, 2000; Min, 2002). Throughout the 2000 Election Campaigns, the SMOs played a leading role, while a relatively small number of online community activists supported them. Despite great differences in their forms of communication and leadership, SMOs and netizen groups collaborated tremendously during this formative period of the netizen movement. After expanding their movement after 2000, however, netizens began to reveal their own voices distinct from those of the SMOs.

The Korean netizen movement entered a new phase in 2002, when serial collective action, including the World Cup Cheering, the Candlelight Vigils, and the 16th Presidential election, occurred within a year.11 Even if the World Cup Cheering is not a political action in itself, it provided a significant opportunity to engage people in a large-scale collective action online and offline. The “Red Devils,”12 an Internet-based fan club for the Korean national soccer team, successfully mobilized 22 million people, directing street cheers across the nation. The Red Devils mainly appeal to those in their teens and 20s, a generational demographic which had been presumed to be politically apathetic. With no authoritarian leadership or hierarchical structure, the Red Devils carefully planned their massive cheers through online discussion and voting (Kim Young-chul, 2004). They discretionarily determined cheering slogans, dress codes, and mass events for each match, such as card sections in the stadium and street cheering in major cities (Cho-Han, 2004; Han, 2007). As many scholars assert, the World Cup experience strongly encouraged people to participate in online and offline actions in the 2002 Candlelight Demonstrations and the subsequent presidential election (Cho-Han, 2004; Han, 2007; Lee Hyun-Woo, 2005; Song, 2003).

In the midst of the World Cup Cheering in the summer 2002, a tragic accident occurred in Euijungbu, just north of Seoul, where the 2nd Infantry Division of the US Forces Korea (USFK) was stationed. On June 13, two middle-school girls, Mi- sun Shim and Hyo-soon Shin, were crushed to death by a US armored vehicle driven by two US soldiers. In November 2002, a US military tribunal in Korea acquitted the two soldiers of negligent homicide, and the accused left Korea soon after the judicial ruling. This case was adjudicated under the “Status of Forces Agreement”13 (SOFA) signed in 1966 between the US and South Korea, which allows the 37,000 US service members (and their dependants) stationed in South Korea to be tried in a US court. Though some oppositional social movement organizations14 had consistently highlighted the law’s unfairness and sought to expose the absurdity of the SOFA, most Koreans were reluctant to openly air complaints and grievances, as anti-Americanism had been long equated with pro-communism since the Korean War. The deaths of Hyo-soon and Mi-sun, however, provided a “tipping point”15 (Kim and Kim, 2005) that spawned anti-American sentiments in a mostly pro-American country (Han, 2007).

While mainstream media paid little attention to this incident, an anonymous citizen reporter of OhmyNews, a progressive online news site, triggered the start of nationwide demonstrations against the US juridical decision. On November 30, 2002, an OhmyNews citizen reporter with a virtual ID “Angma” [devils]16 first suggested holding candlelight vigils as a memorial to the two girls:

It is said that dead men’s souls become fireflies. Let’s fill downtown with our souls. With the souls of Mi-Sun and Hyo-Soon, let’s become thousands of fireflies ... Holding a candle and wearing black suits, let’s have a memorial ceremony for them ... We are not Americans who avenge violence with violence ... Let’s fill downtown with our candle-lights. Let’s put out American violence with our dream of peace.

Supporting Angma’s suggestion, a number of citizens began to gather each weekend at the Kwanghwa-moon square, demanding that: (1) President George W. Bush issue a public apology for the deaths of Mi-sun and Hyo-soon; (2) the SOFA be amended to eliminate immunity from prosecution for US soldiers; and (3) equal relations between Korea and the US be established. Approximately 422 candlelight demonstrations were held for at least 20 months, from November 2002 to June 2004.

Fueled by the unexpected success of the candlelight vigils, a number of SMOs decided to join the struggle, reorganizing an allied SMO committee, “Bum-Dae-Wee”17 (Kim Gisik, 2006). While Bum-Dae-Wee formally asserted that it would support citizens’ spontaneous involvement, some doubted that it successfully embraced the increasing autonomy of the netizens. While many netizens demanded free discussion equally open to all participants, the SMOs remained entrenched in hierarchical leadership when directing the vigils. Angma argued that the SMOs’ stubbornness resulted from their conventional leadership, which was predicated on vanguardism and authoritarian, top-down decision making:

Many people on the net said that they would go to the vigil because they truly wanted to do anything for the dead girls, even though they didn’t like the “Undong-kwon [activist circle]” ... They wanted to talk about their own stories as they did online. They wanted free and open discussion ... But for Bum-dae-wee, those people were still “ignorant masses” – that is to say, the masses that had to be informed and educated by SMO leaders.

In the midst of the vigils, a well-known online commentator “Ulcar-man” posted his observation on the progressive news carrier Daejabo:

A lot of their [SMOs’] flags blocking all the sights, [people were sitting in] a radial pattern around a podium, stunning speeches sounded through electric amplifiers, and VIPS engaged in routine agitationism ... all of their conventional movement repertoires were so tiresome and irritating.

The symbolic contrast between flags (representing SMOs) and candlelights (representing netizens) is noteworthy. Flags symbolize conventional social movements that tend to homogenize citizens under the banner of an organization, while candlelights here symbolize individuality and the equal status of the participants, who hold candles regardless of gender, age, political affiliation, and socioeconomic status. Later, Bum-Dae-Wee recommend that its affiliated SMOs not hold flags and factional pickets. However, the conflict between Bum-Dae-Wee and some netizen groups was never fully resolved. The two contentious parties were ultimately protesting in different directions.

Bum-Dae-Wee aimed to develop and transform the candlelight vigils into anti-American mass struggles. Spurred by widespread anti-Americanism mounting nationwide, it directed a march toward the US Embassy to visualize the hostile relationship between Koreans and US Power. As a demonstration around the US Embassy was legally prohibited, demonstrators could not avoid violent confrontations with the police, who had been ordered to keep the US Embassy from the protesters and subdue them if necessary. Dissenting from the Bum-Dae-Wee’s direction, Angma and some netizen groups shifted their focus more toward antiwar and pacifist issues:

Our candlelight vigils should be directed toward anti-war protest and peace rallies ... Current candlelight vigils (led by Bum-Dae-Wee) fail to effectively deliver the message of anti-war world peace, clinging to the discourse of national independence ... I object to marching toward the U.S. Embassy. It unnecessarily causes violent struggles. Peacefully holding a candle is enough to convey our will to oppose the Bush administration. Now it is time to move to the anti-Iraqi war protest, cooperating with the international society beyond the boundaries of nation-states.

(“Interview with Angma,” OhmyNews, January 3, 2003)

The candlelight demonstrations gradually declined after the separation of the netizen groups. However, the 2002 vigils offered a significant opportunity for the netizen movement to diverge from institutionalized social movements, representing a new wave of civic activism by non-institutionalized, networked individuals. Their differences were revealed in the movement repertoires and organizational forms, as well as by netizens’ political directions (Table 10.3).

A month after the 2002 Candlelight Vigils, in December 2002, the 16th Presidential Election newly demonstrated the critical power of netizens in shaping Korean politics. The support of progressive, Internet-savvy young voters carried to victory a new face in the New Millennium Democratic Party (NMDP),18 Roh Moo-hyun, who defeated dramatically conservative Grand National Party (GNP)19 candidate Lee Hoi-chang (who was backed by several major newspapers). The victory was stunning in light of the fact that Roh Moo-hyun steadily fell behind Lee Hoi-chang for most of the presidential campaign. There is little doubt that this surprising outcome was initiated by the foundation of “Nosamo” (a Korean acronym for “People who love Roh Moo- hyun”), an online-based supporter community for Rho (Lee Keehyung, 2005; Rhee, 2003). Conservative newspapers labeled this election “the victory of 2030 [those in their 20s and 30s] over 5060 [those in their 50s and 60s]” (Chosun, 2002). Many analysts spoke of a “revolution by netizens” (Kim Seong-Sun, 2003) and a “victory of new media” over old media, such as major right- wing newspapers (Kim and Johnson, 2006; Rhee, 2003). In the second stage, the netizen movement started to reveal its own voices independent from SMOs, as it collaborated and competed with existing SMOs, and successfully orchestrated the 2002 protests and the election campaigns.

In the third phase after 2002, the netizen movment continued to mature, reshaping the whole of Korea’s social movement landscape while the leadership of preexisting SMOs seriously declined. Unlike the 2002 Election, the Presidential Election of 2007 saw GNP candidate Lee Myung- bak elected by a great margin, representing a conservative victory.20 Observing a rapid upsurge of right-wing power on the web, some have expressed skepticism regarding the sustainability

of the progressive netizen movement (Daejabo, 2006; Lee Keehyung, 2005; Sisa Seoul, 2006; Yu Sukjin, 2006). Emphasizing contrastive outcomes between 2002 and 2007, they asserted that civic power on the net is only “temporary and ephemeral” (Dong, 2007). Within a half year, however, when the 2008 anti-US beef protests plunged President Lee into crisis, the netizen movement appeared not fleeting but rather reconfigured and reinvented, much as Chadwick (2007) refers to the resurgent potential of “sedimentary networks.”21

On April 18, 2008, a day before the summit conference of Lee Myung-bak and George W. Bush, the Lee administration announced that both parties had reached an agreement to resume the importation of US beef, which had been banned after a 2003 case of mad cow disease had been discovered in the US. This resolution sparked harsh criticism, for no other countries had agreed upon such a concessive, even humiliating, settlement, which included revoking the ban on beef older than 30 months and prone to mad cow disease. Subsequently, on April 29, the Korean television network MBC aired a segment of its documentary program PD Diary entitled “Is US Beef Really Safe?” The documentary accused the Lee administration of compromising public health standards in order to push a Free Trade Agreement between the US and Korea (BBC News, 2008). Following the program, a variety of online communities started online actions demanding the withdrawal of the settlement and the impeachment of the president, who gave up “national food sovereignty” (Cho H. 2010; Kyunghyang Daily, 2008; Sisa-In, 2009). On May 2, 2008, “Nationwide Movement to Impeach the President” (NMIP: http://café.daum.net/antimb) held the first anti-US beef candlelight vigil, which activated subsequent protests. Advancing upon the movement repertoires started in the 2002 candlelight vigils, the 2008 candlelight vigils exhibited evolutionary advancements in both size and scope.

First, a diverse range of people, including teenage groups and young female communities, appeared as new leaders throughout the 2008 vigils. Major leading groups were online communities that had been considered non-political and nonpartisan. At the initial stage, junior and senior high school students, who accounted for 60 percent of the participants (Joongang Daily, 2008), stimulated adult groups to join the protests.22 As time went by, age groups became more divergent and the number of participants increased. In particular, it is striking that young female netizens played a critical role online and offline. Namely, the “top three female communities,” which led online signature collection, conducted anti-Cho-Joong-Dong campaigns and mobilized unexpected groups of people for street protests, including members of non-political, consumerist online groups such as “Sangko” (café.daum.net/ssanguryo), which shares information about plastic surgery, Soul-Dresser (café.daum.net/SoulDresser), which discusses fashion trends, and Hwajangbal (café.daum.net/makingup), which reviews cosmetic products.

Second, the 2008 vigils proposed a new way of civic action that simultaneously raised a variety of national issues without centralized leadership. Though the vigils began with discontent fueled by the resumption of US beef imports, the protests went far beyond economic issues of international trade. As American beef was rather a symbol of the US superpower dominating a global economy, President Lee lifting the ban on US beef imports was interpreted as his slavish eagerness to gain the political support of Washington by “selling out the nation” (Kyunghyang Daily, 2008; Sisa-In, 2009). Censuring Lee’s dogmatism, protesters shouted a wide range of slogans against high unemployment, over-competitive education policies, the privatization of public companies, probusiness economic policies, and budget cuts in welfare. Different people proposed different agendas in different ways. Unlike the 2002 candlelight vigils, however, there was little conflict creating by dissonant sloganeering. The slogans here, despite their diversity, converged into “anti-Lee Myungbak.”

Third, the movement repertoires became unprecedentedly satiric and entertaining. While the police used water cannons to disperse people, young protesters sang and danced under the water. Families with children camped out on the downtown square during the vigils, enjoying impromptu concerts by voluntary citizens, as if they had come for a picnic (Christian Science Monitor, 2008; Lee S., 2008). When the police built a container barricade to stop demonstrators from advancing toward the President’s House, protestors put the signboard “Myung-bak’s Fortress” on the containers to deride President Lee as a clumsy coward struggling against his people. Observing the autonomous festival-like protests, one reporter described the 2008 vigil as the “protest 2.0” or “postmodern demonstrations” (Lee S., 2008):

This is strange. Even as anti-government demonstrations in South Korea go, this is an odd, odd scene ... “It’s like a festival. They are even using a laser projector to write their protest words in the air. It’s effective because it’s fun” ... With no leaders leading, the protest might be considered “ineffec-tive.” People are protesting individually, shouting different slogans, marching in different directions; different people with different agendas.

(“Party Time at South Korea’s Protest 2.0,” Asia Times, June 13, 2008)

Most importantly, the netizens took a predominant position, supplanting institutionalized activist groups, including SMOs and labor unions. While some neti-zens in the 2002 vigils challenged the authority and leadership of the SMOs, netizens in 2008 played a decisive role in leading the protests. As the SMOs had organized Bum-Dae-Wee as a control tower in the 2002 demonstrations, approximately 1,000 SMOs established the “Dachak-Wee”23 to lead the 2008 vigils. Unlike the Bum-Dae-Wee, however, Dachak-Wee hardly played a leading role throughout the protests (Kim Munjoo, 2008; Lee S., 2008; Weekly Kyunghyang, May 7, 2009).24 The 2008 vigils exhibit a new rise in the leadership of netizens in Korean social movements:

It is a revolutionarily distinct phenomenon that the (2008) vigils were led by online groups. This is rather dramatic as it was never expected. While the first candlelight protest in 2002 was suggest by a single netizen Angma, the 2008 vigils were suggested and projected by online communities, not a single person, such as “Alliance for MB Impeachment” and “Citizens’ Solidarity for Anti-MB Policies,” both of which have 180 thousand members in total ... Currently, the online groups has moved to the center of Korea’s social movements from the periphery. This is a just starting stage of their movement and their influence will be far more expanded in the future.

The 2008 protests became a historic milestone that represents a paradigm shift in Korean social movements. Since the 2008 vigils, Korean netizens have represented the most pivotal agency of civic activism, replacing SMOs’ centralized and hierarchical leadership with the netizens’ decentralized and nomadic autonomy. While Korean social movements until 2008 had been advanced by advocacy groups of professional activists, civic action after 2008 represents a new rise of “citizens that aspire to become an independent subject of talking, acting, and deciding, not satisfied with being mediated by institutionalized activists” (Kim Gisik, 2011).

The emergence of the netizen movement has exerted a dramatic impact on social movements in Korea. First, the political and cultural influence of traditional mainstream media has suffered a relative decline. Korean netizens have challenged the exclusive authority of mainstream media and conservative intellectuals by producing and distributing their own discourse and deconstructing texts produced by mainstreams. Netizens led, in opposition to mainstream media, collective action in the 2002 Candlelight Demonstrations, the 16th Presidential Elections, and the 2008 Protest. In addition, the netizen movement has blurred the distinctions between political and subcultural discourses, struggles and entertainments, and struggles and festivals. As netizens openly expressed their antiauthoritarianism by producing and using satirical image-graphics, black-humored songs, and parodic music videos, they constructed a sense of solidarity and collective identity in opposition to dominant hegemony. As political and subcultural discourses have converged, the traditional boundaries between struggle and entertainment have also become destabilized. In the netizen movement, protests were kinds of exciting adventures, even field-trips, rather than grave struggles. Political struggles were no longer defined – as they had been in previous generations – by street protests concomitant with violent clashes with the police. While this new form of “entertaining” civil action may at first seem frivolous, it has actually provided more secure social platforms on which citizens become empowered.

Further, the netizen movement has prompted novel forms of leadership. Horizontal communication forms, spontaneous involvement, and non- hierarchical and decentralized forms of leadership have challenged the conventions of institutionalized social movements. While it may be true that, as Chadwick (2007) has asserted, SMOs in Western countries have introduced some innovatively “non-hierarchical” forms of organization, in Korea it has been netizens who have offered alternatives to SMOs beholden to hierarchical, pseudo-political-party forms. Unlike European countries, where representative democracy and party politics had been introduced long ago, Korean society is still recovering from a decades-long authoritarianism, and Korean political parties and radical SMOs are still relying on the centralized leaderships that arose during the authoritarian regime. Although the SMOs and political parties in Korea have been adopting the Internet as a tactical tool, they have failed to adopt the deeper values of direct democracy embedded in the netizens’ movement repertoires. The Korean case suggests a distinct model in the evolution of social movements in the digital age, demonstrating that netizens can play a critical role in restructuring political environments in which political parties and SMOs lag far behind in innovativeness and progressiveness.

1 In particular, it is noteworthy that Koreans’ Internet usage rate in the 30–49 age segments (90.2 percent) is higher than Americans’ rate in that segment (82.0 percent), while American Internet usage in the 50–64 age segments (72.0 percent) is much higher than Koreans’ (44.8 percent).

2 Koreans use the Internet for online shopping (57.7 percent) or Internet banking (38.4 percent), while 71 percent of American users access the Internet for online shopping and 55 percent for online banking.

3 The netizen movement has also been referred to as Internet activism (Kahn and Kellner, 2004; Lee Jinsun, 2009), online activism (McCaughey and Ayres, 2003; Vegh, 2003), cyberactivism (McCaughey and Ayres, 2003), cyberprotest (Van de Donk et al., 2004), online movement (Kang, 1998), E-movement (Earl and Schuss-man, 2003), and computer-supported social movement (Juris, 2005). Despite its significance in the contemporary age, these definitions have not been clarified. At the most general level, many scholars broadly point to “political activism using the Internet” (Kahn and Kellner, 2004; Vegh, 2003).

4 According to Charles Tilly (1995), a movement repertoire is defined as “a limited set of routines that are learned, shared and acted out through a relatively deliberate process of choice” (p. 26).

5 Chollian, owned by Dacum, launched its bulletin board service in 1985, followed by Ketel (predecessor of Hitel and now Paran) in 1986 and Naunuri in 1994. Though the number of PC tongsin users as of 1990 was no more than 100,000, most online participants, composed mainly of student activists and progressive white-collar workers, enthusiastically discussed pressing issues and shared information to bring about media reform and social change (Kim Gibo, 2006).

6 Its full title is “Barun-Tongsing-ul-wihan-Moim”.

7 In the PC tongsin era, one of the online network service providers, Ketel, was repackaging news data from only two news outlets: Nae-Ue-Tongin, an extremely right-wing news carrier supported by the Korean Intelligence Service, and Maeil-Kyungjae, an economic news outlet. Some progressive Ketel users demanded that it extend news services to include Hankyoreh-Sinmun, by which they could access more politically progressive news and information. When their demand was refused by Ketel administrators, the Ketel users initiated an autonomous campaign to copy and post Hankyoreh news reports on the Ketel site by themselves (Min, 2002). Some activist participants involved in this campaign soon agreed to found their own network for progressive reform of cyberspace.

8 PD and NL represented two different activist groups: the PD group emphasized class liberation based on a Leninist revolutionary model, while the NL group stressed national liberation inspired by North Korea’s model.

9 According to a survey conducted by an SMO, Civic Action All Together (www.action.or.kr), 81.0 percent of Korean SMOs had their own homepages as of 2000; the major purposes of the homepages include PR (63.8 percent), information sharing (14.9 percent), and communication among members (10.6 percent). To support these SMOs and promote civic engagement in the new media age, Jinbonet was launched in 1998, with the voluntary participation of highly computer-literate activist technicians.

10 Its original Korean name is “Chongsun-Simin-Yeondae.”

11 The catalyzing event was the nationwide World Cup Soccer Cheering in May and June 2002, followed by the 2002 Candlelight Demonstrations beginning in November and the 16th Presidential Election in December of the same year.

12 The Red Devils fan club started with 200 members in 1997. By the time of the World Cup, it boasted 200,000 members. It has open membership: “Anyone who loves soccer can be a member of the Red Devils” (Red Devil’s Code of Conduct).

13 The full title is the “Agreement Under Article IV of the Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States of America and the Republic of Korea, Regarding Facilities and Areas and the Status of United States Armed Forces in the Republic of Korea.” This agreement was signed in 1966 as a supplementary pact of the Mutual Defense Treaty between the US and South Korea devised at the end of the Korean War in 1953.

14 SMOs such as “No Crimes by US Troops” and “Peace Korea” reported that approximately 52,000 crimes, including rape, murder, and kidnapping, were committed by 59,000 US service members stationed in Korea from 1967 to 2002.

15 According to sociologist Morton Grodzins, a tipping point is defined as a previously rare phenomenon becoming rapidly and dramatically more common.

16 As he drew the attention of the media, he disclosed his real name and identity: Kim Gibo, a white- collar salaryman in his 30s.

17 Abbreviation of Bum-Gukmin-Dachak- Wee.

18 In Korean, the New Millenium Democratic Party is Sae Chonnyeon Minjudang. It was a moderate liberal party, founded by President Kim Dae-jung, which served as a ruling party and a minority in the Korean National Assembly from 1997 to 2004.

19 In Korean, the Grand National Party is Hannara Dang. It was the conservative opposition party, which had 150 seats of a total of 273 seats as of December 2002.

20 In the 2007 Election, Lee Myung-bak garnered 48.7 percent of the vote, beating United New Democratic Party (the successor of New Millennium Democratic Party) rival Chung Dong-young, who had 26.1 percent of the vote. The electoral gap between Lee Myung-bak and his rival Chung Dong-young was the largest since the direct presidential election system was revived by the June Civil Uprising in 1987 (Chosun, December 20, 2007).

21 Chadwick (2007) has argued that online network-based social movements can reconfigure old networks over time in response to new demands or a perceived desire. For instance, MoveOn has switched its campaign issues in response to new demands, remobilizing supporters, and reorganizing its network power. While some scholars have questioned the permanence of Internet-enabled forms of political mobilization, Chadwick contends that Internet-based activism persists over time despite a lack of fixed membership or centralized control.

22 Teenagers are referred to as a new movement generation, following the 386 (those in their 40s) and the post-386 (those in their 30s) generation, the so-called “candlelight generation.” The teenage generation is characterized by proficient utilization of the Internet and mobile phones as major information sources and mobilization networks and identifies itself as informed net-based citizens (Kim Munjoo, 2008).

23 This is an abbreviated title of Kwangwoo-Byung-Dachak-wee [The Committee for the Solution of Mad Cow Disease].

24 For instance, when Dachak-Wee announced a meeting at the Chung-gye square on May 6, 2008, some leading online communities suggested a gathering in a different place, in front of the National Assembly on the same day. While merely 5,000 – most of whom were organization members – followed Dachak-Wee’s order, more than 20,000 citizens autonomously gathered in front of the National Assembly (Kim Munjoo, 2008).

BBC News. June 25, 2008. Q&A: S Korea beef protests. Retrieved on May 10, 2011 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/7457087.stm.

Bennett, W.L. 2004. Communicating global activism: Strengths and vulnerabilities of networked politics. In W.V.D. Donk, B.D. Loader, P.G. Nixon, and D. Rucht (Eds.), Cyberprotest: New media, citizens and social movement (pp. 123–146). New York: Routledge.

Bimber, B., Flanagin, A.J., and Stohl, C. 2005. Reconceptualizing collective action in the contemporary media environment. Communication Theory, 15(4), 389–413.

Carroll, W.K. and Hackett, R.A. 2006. Democratic media activism through the lens of social movement theory. Media, Culture and Society, 28(1), 83–104.

Chadwick, A. 2005. The Internet, political mobilization and organizational hybridity: “Deanspace”, MoveOn.org and the 2004 US Presidential campaign. Retrieved on October 16, 2007 from www.rhul.ac.uk/politics-and-ir/About-Us/Chadwick/pdf/A_Chadwick_Internet_Mobilization_and_Organizational_Hybridity_PSA_2005.pdf.

Chadwick, A. 2007. Digital network repertoires and organizational hybridity. Political Communication, 24(3), 283–301.

Cho, H. 2010. The fourth estate’s influence on deliberative democracies: Media framing of the 2008 US–South Korea beef imports controversy. GNOVIS, 10(3), Summer. Retrieved on May 20, 2011 from http://gnovisjournal.org/journal/fourth-estatesinfluence-deliberative-democraciesmedia-framing-2008-us-south-korea-beef-imp.

Cho-Han, Haejoang. 2004. Beyond the FIFA World Cup: An ethnography of the local in South Korea around the 2002 World Cup. Inter-Asian Cultural Studies, 5(1), 8–25.

Choi, Jang-jip. 2000. Korean democratization, civil society, and civil social movement in Korea: The significance of the Citizens’ Alliance for the 2000 general elections. Korea Journal, 40, 26–57.

Choi, Se-jin. 2006. If I can’t dance, it’s not my revolution. Seoul, South Korea: May Day Publication.

Chosun Ilbo. December 26, 2002. Young antiques and old treasures. Jin-sungho Column.

Christian Science Monitor. June 11, 2008. South Korea’s beef protests: Lee’s woes deepen. Retrieved on June 28, 2011 from www.csmonitor.com/layout/set/print/content/view/print/22999173.

Daejabo. 2006. Degradation of the Internet: Ideological struggles on the net. Retrieved on November 21, 2008 from www.jabo.co.kr/sub_read.html?uid=16003%A1%D7ion=section5.

Dong, A. December 18, 2007. The lack of passion in Internet election campaigns ... why? Retrieved on February 7, 2008 from http://blog.joins.com/media/folderlistslide.asp?uid=cjh59&folder=1&list_id=8871357.

Earl, J. and Schussman, A. 2003. The new site of activism: Online organizations, movement entrepreneurs, and the changing location of social movement decision making. Consensus Decision Making: Northern Ireland and Indigenous Movements, 24, 155–187.

Flanagin, A.J., Stohl, C., and Bimber, B. 2006. Modeling the structure of collective action. Communication Monographs, 73(1), 29–54.

Froehling, O. 1997. The cyberspace “War of Ink and Internet” in Chiapas, Mexico. Geographical Review, 87(2), 291–308. Retrieved February 3, 2006 from www.jstor.org/journals/00167428.html.

Garrett, R.K. 2006. Protest in an information society: A review of literature on social movements and new ICTs. Information, Communication and Society, 9(2), 202–224.

Han, Jongwoo. 2007. From indifference to making a difference: New networked information technologies (NNITs) and patterns of political participation among Korea’s younger generations. Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 4(1), 57–76.

Hauben, M. and Hauben, R. 1997. Netizens: On the history and impact of Usenet and the Internet. Los Alamitos, CA: Wiley-IEEE Computer Society Press.

Joongang Daily. May 3, 2008. Three mad cows spark rebellion against Lee. Retrieved on May 22, 2011 from http://joongangdaily.joins.com/article/view.asp?aid=2889347.

Juris, J.S. 2005. The new digital media and activist networking within anti-corporate globalization movements. Annals of the American Academy, 597(1), 189–208.

Kahn, R. and Kellner, D. 2004. New media and Internet activism: from the “Battle of Seattle” to blogging. New Media and Society, 6(1), 87–95.

Kahn, R. and Kellner, D. 2005. Oppositional politics and the Internet: A critical/reconstructive approach. In M.G. Durham and D.M. Kellner (Eds.), Media and cultural studies: Revisited (2nd ed.) (pp. 703–725). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Kang, Myung Koo. 1998. The grassroots online movement and changes in Korean civil society. Review of Media, Information and Society, 3, 109–128.

Kim, Daekyung and Johnson, T.J. 2006. A victory of the Internet over mass media? Examining the effects of online media on political attitudes in South Korea. Asian Journal of Communication, 16(1), 1–18.

Kim, Dongwhan and Kim, Hunsik. 2005. The mechanism of candlelight@ public squares. Seoul: Book Korea.

Kim, Gibo. 2006. Interview with Jinsun Lee. June 2006, Daeku, South Korea.

Kim, Gisik. 2006. Interview with Jinsun Lee. July 2006, Seoul, South Korea.

Kim, Gisik. 2011. Interview with Jinsun Lee. July 2011, Seoul, South Korea.

Kim, Munjoo. 2008. The beautiful new power: The birth of candlelights. Sae- Sa-Yeon [Research Institute for New Society] Column. Retrieved on June 10, 2011 from www.saesayon.org/journal/view.do?pcd=EC01&page=1&paper=20081212214122451.

Kim, Seong- Sun. 2003. Online journalism. Seoul: Dori.

Kim, Young- chul. 2004. Let’s meet in Kwang-hwa-moon. Seoul: Sangkak-kwa-Nukim publication.

KISA (Korean Internet Security Agency) and KCC (Korean Communications Commission). 2010. 2010 survey on the internet usage. Seoul: KISA. Retrieved on June 10, 2012 from http://isis.kisa.or.kr/eng/board/?pageId=040100&bbsId=10&itemId=315.

Kyunghyang Daily. July 8, 2008. Amazoness that lead the candlelight vigils at every crisis: Why we have held the candles? Retrieved on June 22, 2011 from http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=200807082309535&code=940707.

Lee, Byoungkwan, Lancendorfer, K.M., and Lee, Ki Jung. 2005. Agenda- setting and the Internet: The intermedia influence of Internet bulletin boards on newspaper coverage of the 2000 general election in South Korea. Asian Journal of Communication, 15(1), 57–71.

Lee, Hyun-Woo. 2005. The 2030 generation and governance by participatory politics. Seoul: Korea Information Strategy Development Institute (KISDI).

Lee, Jinsun. 2009. Net power in action: Internet activism in the contentious politics of South Korea. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

Lee, Keehyung. 2005. Mediated politics in the information age: The emergence of the ‘net power” and the politics of the Internet media in contemporary South Korea. Korean Journal of Communication Studies, 12(5), 5–30.

Lee, S. June 23, 2008. Party time at South Korea’s protest 2.0. Asia Times. Retrieved on June 20, 2011 from www.atimes.com/atimes/korea/JF13Dg01.html.

Lee, Y. 2005. New social movements in South Korea: Netizens, electronic democracy, social protest and democratization. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association, Hilton Hawaiian Village, Honolulu, Hawaii. Retrieved on January 13, 2009 from www.allacademic.com/meta/p_mla_apa_research_cita-tion/0/7/2/1/6/p72163_index.html.

Lievrouw, L.A. 2011. Alternative and activist new media: Digital media and society series. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

McCaughy, M. and Ayers, M.D. 2003. Introduction. In M. McCaughy and M.D. Ayers (Eds.), Cyberactivism: Online activism in theory and practice. New York and London: Routledge.

Min, Keongbae. 2002. Study on online social movement in the information age: The Korean case study. Seoul: Korea University Press.

NIDA (National Internet Development Agency of Korea). 2009. A comparative study of Internet usage between Korea and the U.S. Seoul: KISA. Retrieved on June 10, 2012 from http://www.nida.or.kr/notice/view.jsp?brdId=060315162928001000&aSeq=090706111900002001.

Oh, Yeon- ho. 2004. OhmyNews: a special product of South Korea. Seoul: Humanist publication.

Poster, M. 1995. CyberDemocracy: Internet and the public sphere. Retrieved on September 20, 2005 from www.hnet.uci.edu/mposter/writings/democ.html.

Rhee, In-Yong. 2003. The Korean election shows a shift in media power: Young voters create a “cyber Acropolis” and help to elect the president. Nieman Reports: International Journalism, Spring, 95–96.

Sisa- in. April 28, 2009. The candlelights have changed my life: Interviews with 100 people. Retrieved on May 25, 2011 from www.sisainlive.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=4323.

Sisa Seoul. June 30, 2006. It is because of Roh Mu- hyun. Retrieved on November 21, 2008 from www.sisaseoul.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=2160.

Song, Ho Keun. 2003. Politics, generation, and the making of new leadership in South Korea. Development and Society, 32(1), 103–123.

Tilly, C. 1995. Contentious repertoires in Great Britain, 1758–1834. In M. Traugott (Ed.), Repertoires and cycles of contention (pp. 15–42). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Van Aelst, P. and Walgrave, S. 2004. New media, new movements? The role of the internet in shaping the “anti- globalization” movement. In W.V.D. Donk, B.D. Loader, P.G. Nixon, and D. Rucht (Eds.), Cyberprotest: New media, citizens and social movement (pp. 97–122). New York and London: Routledge.

Van de Donk, W., Loader, B.D., Nixon, P.G., and Rucht, D. 2004. Introduction: Social movement and ICTs. In W.V.D. Donk, B.D. Loader, P.G. Nixon, and D. Rucht (Eds.), Cyberprotest: New media, citizens and social movement (pp. 1–25). New York and London: Routledge.

Vegh, S. 2003. Classifying forms of online activism: The case of cyberprotests against the World Bank. In M. McCaughy and M.D. Ayers (Eds.), Cyberactivism: Online activism in theory and practice (pp. 71–96). New York and London: Routledge.

Weekly Kyunghyang. May 12, 2009. A year after the candlelight vigils: What remains to us? Retrieved on June 20, 2011 from http://newsmaker.khan.co.kr/khnm.html?mode=view&code=115&artid=19840&pt=nv.

Yu, Sukjin. 2006. The changes in elections and Internet media. Presented at the Forum for Open Media and Open Society, June. Retrieved on January 1, 2011 from www.openmedia.or.kr/bbs/view.asp?dbn=BBS_seminar&sm=pds&code=60.