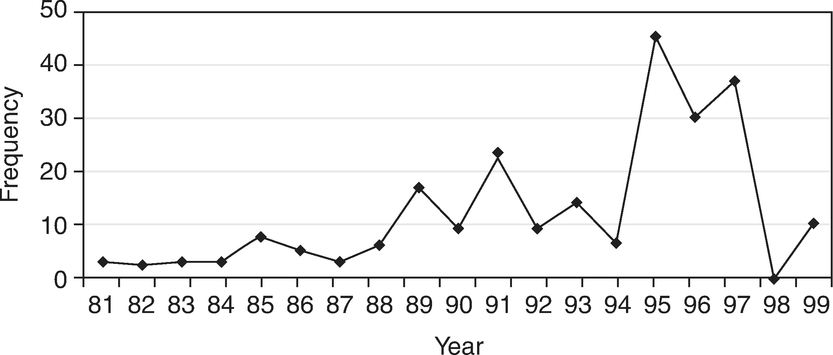

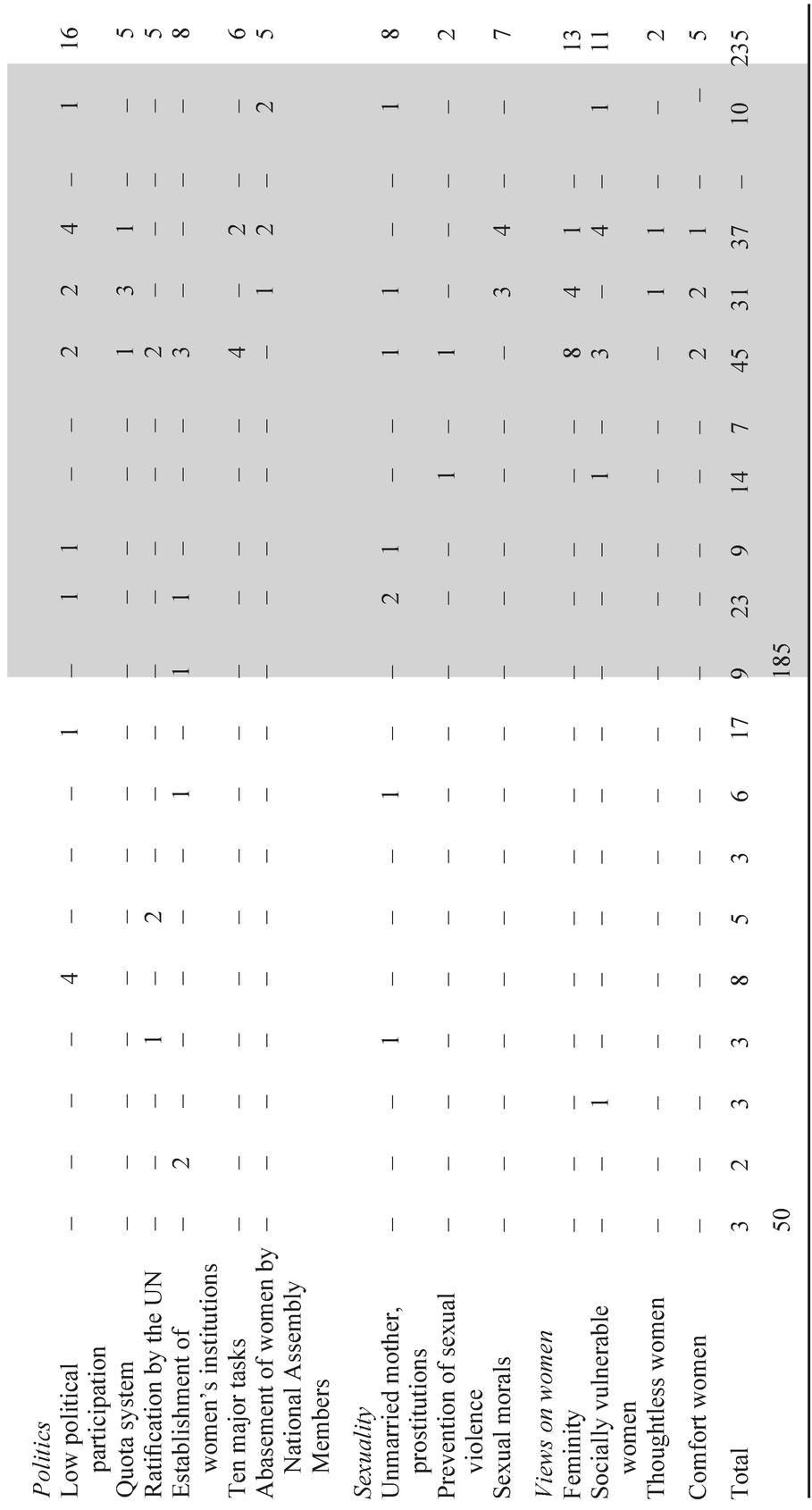

Figure 9.1 The trend of women-related issues discussed at the regular plenary sessions of the National Assembly by year.

Kyounghee Kim

Since the early 1990s, gender equality has become a major social policy issue in Korea as well as in the international society. In Korea, a number of unprecedented developments have since been made by gender policies, including the establishment of the Ministry of Gender Equality and positions of officers in charge of women’s policies in other ministries. At the same time, the women’s movement, which started as part of the democratization movement in the 1980s, has shifted the focus of its agenda to such women-specific goals as equal opportunity for employment, maternity protection, and women’s human rights, among other issues. It has also begun to participate in institutional politics, abandoning its previously antagonistic attitude toward the state.

Until the early 1990s, the government had little concern with women’s policies. Women’s issues that were dealt with in the National Assembly were mostly related to the mobilization of female manpower for economic development, birth control as part of the population policy, and using housewives as volunteers in society. The women’s movement did not look to the state for any substantial solution to women’s problems. Instead, it tended to criticize the idea of formal equality before the law. However, since the beginning of the 1990s, the state has been recognized as an arena in which to find a solution to women’s problems. The government and the women’s movement are both working to achieve equality de facto.

Gender equality, the proclaimed goal of women’s policies in Korea, is clearly expressed in the government’s policies on women and it is the major agenda of the women’s movement. However, even though the government and the women’s movement employ the same terminology, an analysis has yet to be undertaken to examine how each group uses the language in formulating women’s policies. Existing studies on the relationship between women’s policies and the women’s movement focus on the extent of legitimacy the state and the women’s movement have in politics and their impact on forming women’s policies (Kim 2000a; Kim 2000b; Jeong 1993; Ji and Gang 1988). Especially when it comes to women’s policies which deal with issues specific to women, most research has concentrated on the form in which such policies are legislated. Consequently, it has been difficult to identify the gap and tensions that exists between the formal political discourse of the state and the policy discourse of women’s movements.

In this context, by undertaking a frame analysis of the paradigm change in women’s policies of both the government and women’s movements in the 1980s and 1990s, the present study will examine the formulation and characteristics of the women’s agendas in Korea. A frame, as a central idea or “plot” that gives meaning to an event or an issue which is still unfolding, provides a position from which to suggest policy responses and direction in dealing with that issue. A collective action frame in social movements accounts for the causes of injustices which engender collective sufferings and the alternatives to them while interconnecting various experiences into a coherent point of view. It is formed within political, social, and cultural contexts through the strategies, tactics, and organizational methods of social movement organizations (Snow and Benford 1988, 1992; Snow et al. 1986).

In general, the frames of policies and social issues are not different from those of social movements in their concepts and characteristics. Existing methods of policy analysis have largely been concerned with the examination of legal bills or statutes. These methods are limited in that they have no choice but to deal with a few legal bills and their provisions at face value. In contrast, by organizing and clustering into packages ideas which are associated with a particular issue, the frame analysis can reveal the key ideas which give meanings to a series of events or speeches (Gamson and Modigliani 1989).

The present study attempts to analyze frames of the government and the women’s movement revolving around women’s policy issues by comparing the 1980s and the 1990s.

In examining frames of women’s policy issues of the women’s movement, this study focuses on activities of the Korea Women’s Associations United (KWAU) and analyzes the proceedings of its regular general meetings and its periodical Minju Yeoseong [Democratic Women]. The progressive women’s organizations in Korea formed the KWAU as a national association of 21 women’s organizations in 1987, contributed to the June democratization movement, and led women’s movements in the 1990s with the issues of women’s right to lifelong work, maternity protection, the elimination of sexual violence, national unification, comfort women, and politics of everyday life.

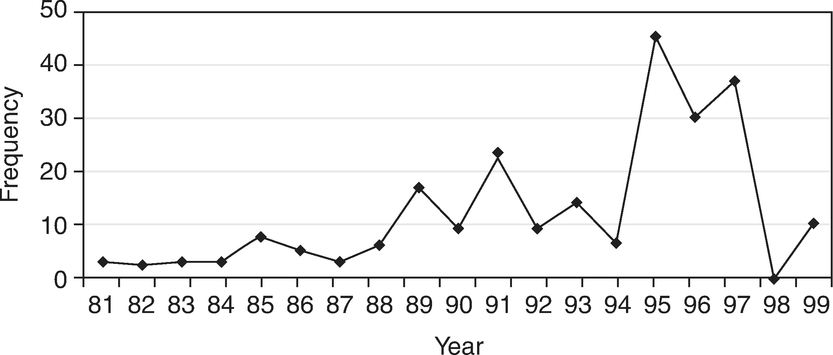

For the frame of the government’s official policies on women, I analyzed the records of the National Assembly. The analysis uses speeches delivered on women at the regular plenary sessions from 1981 to 1999 National Assembly. Since the National Assembly is Korea’s most important legislative institution, it is indispensable to the study of the policy-making process and the formation of discourse. The data for this study were obtained by searching the database of the National Assembly Library for all the records which include the word “women.” A total of 235 cases have been established by classifying the contents of speeches according to the themes they deal with and counting each theme as a case. Here the records of women’s affairs are roughly classified into family, labor, sexuality, welfare, and politics, for each of which specific issues are further identified. A frame can then be constructed by picking out the key ideas which underlie the specific issues. In addition, by quantifying how often a particular issue is brought up, I perform a content analysis to determine the tendency of increase or decrease of support for a particular package of ideas in each period.

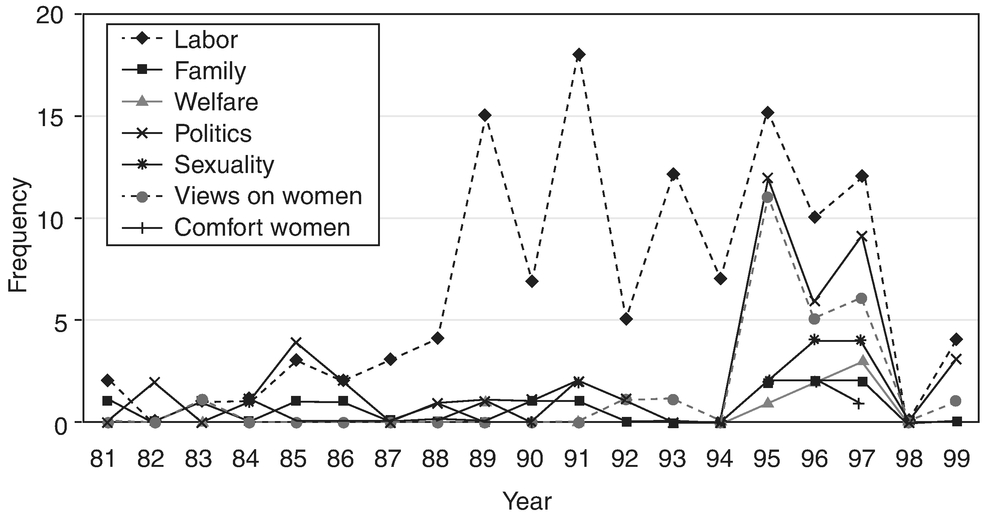

The results of the content analysis of policy agendas on women at the National Assembly are provided in Table 9.1. It shows that in the 1980s the government had no positive perception of women’s policies, and women’s agendas in the National Assembly were very few in number when compared to the 1990s.1 Among the total of 235 cases, 50 speeches were delivered in the 1980s, which amounts to about one-fourth of the 185 speeches that were delivered in the 1990s (see Table 9.1 and Figure 9.1). Among the specific issues discussed in the National Assembly: tele-work and maternity leave in the area of labor, the family law and the amendment of tax laws in the area of family, unemployed female heads of households and pensions in the area of welfare, femininity in the area of sexuality, and women drafted by Japanese military for sexual slavery, are new issues that have emerged in the 1990s (see Figure 9.2).

In the 1980s, women-related policies of the government were dominated by the population policy centered around birth control and the labor policy about utilization of female labor. Because there were no institutions to take full charge of women’s affairs, the government was not able to carry out consistent policies for women. Nevertheless, the United Nations’ (UN) policy orientation and

Figure 9.1 The trend of women-related issues discussed at the regular plenary sessions of the National Assembly by year.

Table 9.1 Women-related issues discussed at the regular plenary sessions of the National Assembly, by year and by issue

Figure 9.2 The trend of specific issues on women discussed at the regular plenary sessions of the National Assembly by year.

programs for women greatly affected the endeavors to make the problem of women a policy issue in Korea in the 1980s. As is shown in the analysis of the records of the National Assembly, the UN project of women’s development and the ratification of international treaties were the two major sources of external pressure which the Korean government could not avoid. Proclaiming the year of 1975 as World Women’s Year, the UN adopted the Women in Development (WID) approach to help solve women’s problems by undertaking various projects for women’s development throughout the 1980s. WID paid attention to the role of women alienated during the course of economic development in developing countries and recognized them as a resource that can be used for economic growth (Moser 1993; Miller and Razavi 1998). In this context, certain progress — such as the establishment of the Korean Women’s Development Institute in 1983, the setting up of the Basic Plan on Women’s Development in 1985, and the amendment of the Mother and Child Health Act in 1986 — was made which brought women’s issues to the level of policy discourse under the agenda of women’s development. However, such women- related organizations were isolated from the center of policymaking and implementation and their budgets occupied less than 1 percent of the total budget.

In particular, the demands women made during the course of the constitutional amendment and the struggle for democratization in 1987 compelled the government to stress the prohibition of discrimination against women in the economic sphere, the pursuit of women’s welfare and the protection of maternity in its policymaking. During this period, the government set the goal of women’s policies at the abstract level of “Co-participation of Men and Women, Co- responsibility for Society” (Second Minister of Political Affairs 1998). However, with the increase of women’s participation in economic activities and the expansion of the women’s movement, the Office of the Second Minister of State for Political Affairs was launched as the administrative organization to deal with the affairs of women. Major women’s policies formulated in this period include the enactment of the Gender Equality Employment Act in 1987 and its amendment in 1989 and the enactment of the Mother and Fatherless Child Welfare Act in 1989 (Kim 2000b).

In the 1990s, women’s policies eventually became all-inclusive and comprehensive for the realization of gender equality.

Among the specific issues discussed in the National Assembly, tele-work and maternity leave in the area of labor, the family law and the amendment of tax laws in the area of family, unemployed heads of households and pensions in the area of welfare, femininity in the area of sexuality and comfort women are new issues that have emerged in the 1990s (see Table 9.1).

The Kim Young-sam government (1993–1997) appointed three female ministers and a female vice-minister, set up the office of a secretary of political affairs in charge of women under the secretariat of the President, and established the Special Committee on Women’s Affairs in the National Assembly for the legislation of women’s policies. It also launched the Globalization Promotion Committee and included women’s issues in its ten priority tasks. It amended the Gender Equality Employment Act in 1995 and thereby prohibited the recruitment or employment of women on the basis of physical features, and enacted the Act on the Punishment of Sexual Crimes and Protection of Victims in 1994 (Namnyeo pyeongdeung-eul wihan gyosu mo-im 1994). By adopting the idea of gender mainstreaming in 1995, the major international strategy for women’s policies, the government enacted the Framework Act on Women’s Development which has been the basis for carrying out systematic women’s policies above and beyond those of the 1980s. In the Framework Act, the basic objectives of women’s policies are the realization of gender equality, the promotion of women’s participation in society, and the enhancement of women’s welfare. Based on the Framework Act, the government set up the First Basic Plan for 1998–2002 and selected 20 major tasks (Second Minister of Political Affairs 1998; Kim 1996).

While the women’s policies of the 1990s reached a considerable level of formality, we can find certain tendencies in the ways in which women-related problems are understood.

First, with respect to the area of labor, women’s economic activities tend to be seen in terms of using human resources to increase national competitiveness. This policy frame has been consistently sustained from the 1980s through to the 1990s. The following speech supports this point: “By expanding opportunities for employment for women including housewives, it can facilitate women’s employment and help solve the problem of high wage, such that it will relieve corporations of the wage burden” (October 30, 1996, Korean National Assembly Record). In the records of the National Assembly of the 1990s, the end of discrimination in employment and the expansion of childcare facilities are seen as important for increasing female participation in the workplace. Beginning from the 1990s, maternity protection (maternity leave), public work and volunteering services, tele-work, and flexible work have been proposed as ways to increase female participation in the labor market. The methods proposed to use the female workforce tend to draw a line between employed and unemployed women (or housewives). They suggest that unemployed women should be used in unpaid volunteer services or group activities. Also, the use of the female workforce in the 1990s is compared to the aged and the disabled who have been alienated from the labor market, as well as to immigrant workers. The analysis of the records of the National Assembly shows that discussion expanding women’s employment only in terms of using female workforce are not necessarily conducive to solving the fundamental obstacles to women’s economic participation — the age-old practice of discriminating against women.

Second, an analysis of the records indicates that from the end of the 1980s the National Assembly has intermittently raised the issue of women’s welfare, particularly in relation to those who need protection from the government. In the 1990s, the issue begins to be brought up in terms of globalization and quality of life — the government’s basic policy orientation. The welfare issue related to women is still monopolized by speeches about women who need social protection, such as prostitutes and low-income women, whereas the welfare of women in general is mentioned mainly in speeches which concern social insurance. What is to be noted in this regard is that women’s mental health is being raised as an issue. With no doubt it is a new issue when we consider that the issue of welfare has up to now focused on the material side of social life. The welfare of rural women who have been marginalized in women’s policies is also being raised.

Third, the political issues related to women are dominated by speeches about improving women’s low political representation and status that are little more than mere rhetoric. As a means of rectifying the low political representation of women, the establishment of an institution in charge of women’s policies and the adoption of the quota system are most frequently mentioned in the National Assembly. There are virtually no remarks that try to describe the significance of the low political representation of women’s matters and why it should be rectified.

Fourth, the policy frame of family stresses family as a unit of social reproduction and support: “The basic unit for community is family. It is in the framework of a warm family that the happiness of youth, housewives and the elderly people should be fostered” (October 22, 1996, Korean National Assembly Record); “The problem of the elderly suffering dementia is aggravated by the spread of nuclear and small-size families, the employment of women, the weakening of the traditional filial piety toward parents and the elderly, etc.” (July 7, 1999, Korean National Assembly Record). Besides, the population policy which gave priority to birth control in the 1970s and 1980s has now begun to shift because of the disproportionate gender ratio resulting from the preference of sons and the decline of the childbirth rate.

Finally, speeches on sexuality delivered at the National Assembly have concerned the following issues: unmarried mothers and prostitutes, sexual violence, and the corruption of sexual morals. Among the three, the first two are considered the consequences of the degradation of sexual morals. The following speech shows the frame of the sexuality-related agenda: “Since prevention goes first before anything else, it is necessary to cure our social ills and establish a morally healthy society” (July 12, 1995, Korean National Assembly Record). The images of women at the National Assembly are discriminating against mothers, sound working women, women as a socially vulnerable group who need protection, those who are blamed for familism and overconsumption, and others.

When women’s agendas are clustered according to policy frames, women’s policies of the 1980s and those of the 1990s exhibit differences in content but are almost identical in terms of policy frames (see Table 9.2).

The only difference lies in the area of family: whereas policy in the 1980s concentrated on birth control since population growth was thought to be an obstacle to economic growth, its focus had shifted in the 1990s to the problem regarding the disproportion between the two sexes and the decline in the childbirth rate.

Although women’s agendas proposed by the National Assembly have changed both in terms of quantity and diversity, they are not enough to achieve gender equality. The establishment of such institutional apparatuses as the Framework Act on Women’s Development and the Gender Equality Employment Act has encouraged women’s organizations to play the role of pressure groups to monitor the implementation of the laws since the early 1990s. Consequently, this has prevented women’s policies from becoming perfunctory or ending up as nothing more than political slogans. Furthermore, the difference between the women’s movement and the institutions in how they see the issue of women have always created tension or a conflict in the process of formulating women’s policies.

Given that the major social issues in the 1980s in Korea were the exclusionary and authoritarian rule of the military regimes, the grim reality of the divided nation, and the problem of working classes, issues concerning women were not primary. Under this circumstance, the women’s movement was no exception in making social democratization, national autonomy, and people’s acquisition of power as its own frame.

The Gwangju Uprising in 1980, the transfer of power to the Chun Doo-Whan regime, and strong anti-governmental struggles constituted the political background against which the working class-oriented women’s movements came into existence. In particular, the appeasement policy of the Chun regime in 1983 provided more expanded political space for social movements than ever before (Jo 1990; Wells 1995). It is in this phase of appeasement that many women’s movement organizations — such as the Alternative Culture, the Korea Women’s Hot Line, the division of Women’s Affairs of the United Front of Youths for the Democratization Movement, and the Women for Equality and Peace — were established. These organizations sought to distinguish themselves from the liberal women’s movement centered around the Korean National Council of Women (Yi 1998; Yi 1994; Yi et al. 1989). Participants in those organizations were mainly women activists who had been engaged in the students’ movement, women scholars who graduated from Ewha Womans University, social education trainees of the Christian Academy, and women worker activists of the 1970s.2

As the survival right of the urban poor and women workers became a social issue after 1984, the problem of working women emerged as an important agenda for the progressive women’s movement and became a focal point around which different women’s organizations began to consolidate (Jeong 1993). In pursuing women workers’ rights, progressive women’s organizations held the first Women’s Conference in 1985 under the slogan of “women’s movements along with nation, democracy and people” (Yi et al. 1998).

In the course of transition to democracy in 1987, the experience women had in participating in the social democratization movement brought into sharp relief the need for an independent and national association that could organize around various needs of women. In the political phase represented by the constitutional amendment, the political consciousness of the people in general was raised and a variety of issues that had never been raised before were brought to the attention of the public, including those related to female manufacturing and clerical women workers, housewives, sexual violence, religion, environment, and childcare. Taking advantage of the relatively open political atmosphere, 21 progressive women’s groups formed a nationwide organization called the KWAU while a number of large and small organizations such as the Korea Womenlink came into existence (Yi et al. 1998).

However, the transition to democracy and the upsurge of the problem of women did not automatically bring a favorable situation to women. It was the old political forces that won most of the elections held in the process of transition to democracy. During this period, the KWAU still concentrated its efforts on the task of how to have many women participate in the democratization movement. Ever since its inception, it continued to join the national alliance for the democratization movement and to participate in demonstrations demanding Constitutional amendment in support of the direct election of the President.

The establishment of the military government elected by popular vote and the embarkment of the National Assembly in which the opposition commanded the majority, resulted in the enactment and reformation of women’s policies, though in a way that was incomplete and distorted. In the late 1980s, the political activities of the KWAU were double-sided. Not only was it involved in the anti-governmental movement, but also at the same time that it strived for institutional changes and the legislation of women’s demands (Yi et al. 1998).

Besides, the collapse of the Eastern Bloc began to undermine the legitimacy which Marxism and Minjung [people] ideology had enjoyed in Korea and, consequently, called into question socialist and Marxist feminism which constituted the theoretical basis of women’s movements in Korea (Louie 1995; Sahoe-wa Sasang 1989).

This was because the women’s movement, as part of the general political culture centered around democratization and anti-governmental movement at that time, revealed its limitations in gaining the trust of a larger segment of women, those beyond women workers and poor women. In this respect, the institutional politics and public policies were not regarded as a space for solving women’s problems but rather as a target of criticism, while the government’s policies for women were also largely perfunctory.

Women’s rights were the frame of the progressive women’s movement in the early 1990s. The frame was critically questioning the imperfect democracy, and the argument that equal citizenship was in fact based on the exclusion of and discrimination against women formed the core of the frame. This frame was intended to correspond to the interests of women in general through such issues as lifelong equal work, the protection of maternity, sexual violence as the violation of human rights, and pacifism of women.

Equal employment was raised as the issue of “women’s right to lifelong work and the protection of maternity.” Recognizing that childbirth and rearing were the main obstacles to women’s social participation, which eventually led to gender inequality, the KWAU demanded the reevaluation of the protection of maternity, urged the public to consider the protection of maternity as a problem of labor, and took it as a means of securing the right to lifelong employment.3 Protection and equality, which have always been the foci of debate in feminism, co- existed without a conflict in the discourse of women’s rights of the KWAU. The concrete activities of the KWAU included the amendment of the Gender Equality Employment Act, the enactment of the Infant Care Act, the defense against the abolition of menstruation leave, and resistance to the enactment of the Act on Worker Dispatch System among others, most of which were intended to cope with the government’s labor policies that were unfavorable to women.4

This discourse of women’s rights corresponded to the needs and interests of women which became diversified after 1987 and, at the same time, fell within the contexts of international organizations like the UN and global feminism. With respect to the issues of protection and equality, the standards of international organizations played a role in justifying the discourse of women’s rights.

The agenda of sexual violence, which was the priority project of the KWAU during 1992 through 1993, aimed at a social campaign for the elimination of sexual violence and the enactment of laws for its prevention. More specifically, this project aimed at the conversion of the existing conception of sexual violence, the loss of chastity and morality on the part of the victim, to the violation of human rights (Korean Women’s Hot Line 1991). In order to achieve the enactment of laws concerning sexual violence, the KWAU organized an alliance among women. Taking advantage of the presidential election which was scheduled for this time, the enactment of the sexual violence prevention law was adopted as a campaign pledge by the presidential candidates. Although the issue of sexual violence had been raised ever since the establishment of the Korea Women’s Hotline in 1983, the focus of concern shifted greatly in the 1980s. That is, the issue of sexual violence was extended to cover the experiences of women in general, going beyond the efforts to politicize it as a control mechanism used by the non-democratic government against women activists and workers or to utilize it as part of the anti-US cause for national autonomy.

After the establishment of the civilian government in 1993, the women’s movement was dominated by the frame which adopted a “women’s perspective” as a way of seeing society. This discourse marked a turning point from the frame of women’s rights which had until then played a leading part, not only in changing social consciousness and government policies, but also in forming the identity of women in general in line with the broader popular trend toward feminism. In 1994, the KWAU redefined its own objectives as follows to promote cooperation and exchange between women’s organizations and to bring about gender equality, women’s welfare, democratization, and national unification. The programs which were designed to achieve these objectives, including lobbying for the enactment and improvement of laws and institutions for the promotion of women’s rights and interests, programs for women’s welfare and for women workers, and programs related to national unification, etc.5 Breaking from the previous view of women as “those who are oppressed,” the women’s movement turned the focus of its concern to the role of women as “those who transform and create a new society”.6 The frame was well in accord with the social discourse on the quality of life and globalization as well as the women’s policies of international institutions and global feminism. It was in the same context as the slogan for the Beijing World Conference on Women, “See the World with Women’s Eyes.”

Issues concerning the nation and national unification, which the progressive women’s movement continued to raise, were also interpreted within the discourse of a woman’s perspective. The programs for the national unification carried out by the women’s movement organizations in the 1990s can be seen as the combination of the issues of gender and nation, through which the KWAU tried to demonstrate that the pacifism of women can contribute to the unification movement. They also further stressed the need for women to continue to participate in the movements for the nation and democratization.

The frame of women’s perspective could expand itself socially and culturally by raising the issue of “everyday life politics.” In 1994, the KWAU created a catch phrase, “Open Politics, Everyday Life Politics.” Specifically targeting four local council elections held in 1995, it aimed at the political empowerment of women through politics in everyday life. Given that the political process in Korea was dominated by men, controlled by particular parties or groups, and that party politics was also based on a certain person or region, it was not easy for women to participate in politics. Under these circumstances, the KWAU saw participation in local councils as a relatively easier way to advance into the arena of politics.7 “Everyday Life” politics was based on the view that all the problems which arose in the private sphere of women’s everyday life could be politicized into social issues.

Frames of the women’s movement were realized as the “politics of engagement” at the level of practical activities. The demands that had been since the early 1990s for the right to lifelong work, the elimination of sexual violence as the violation of human rights, and unification and democratization, materialized into specific policies through engagement in the institutional politics. These features show that the women’s movement in the 1990s no longer saw the state as an antagonist, but as an arena where women’s problems could be tackled. This change of perception facilitated the process of turning organizations of the women’s movement into legal entities.

Whereas the women’s movement until 1987 could be characterized as activists centered, it was transformed in the 1990s into diversified and professionalized movements that reflected various strata, concerns, and interests of women.

Women’s policies in Korea up to the 1980s were largely determined from above. Since there have been few opportunities for realizing women’s agenda via official channels, the women’s movement itself has assumed the role of quasi-party and has thus contributed considerably to the development of women’s policies in the 1990s. Women’s policies, which have continued to be improved on since the mid-1990s, and the creation of institutions in charge of them in central and local governments, are valuable resources for the development of Korean women. In 1998, the Kim Dae-jung government established the Presidential Commission on Women’s Affairs as the government institution in charge of coordinating women’s policies. To strengthen the enforcement power of the Commission, it also appointed the officer in charge of women’s policies within the six Ministries of Labor, Health and Welfare, Justice, Government Administration and Home Affairs, Agriculture and Forestry, and Education and Human Resources Development. In 2001, the Commission was transformed into an independent state institution, the Ministry of Gender Equality.

Under the Kim Dae-jung government, one of the most remarkable phenomena was the emergence of feminist bureaucrats and politicians who majored in women’s studies and had activist experience in women’s movements. However, they have been facing the task of a feminist way to engage in politics within the government (Kim 2000). In addition, as the women’s movement led by the KWAU has begun to work under the banners of political engagement and gender mainstreaming since the 1990s, the relationship between the politics of engagement and alternative politics has become a point of issue (KWAU 2000).

Seen from the vantage point of the early 2000s, Korean society possesses such valuable resources as government organizations and feminist officials in charge of women’s policies, laws and institutions for the implementation of women’s policies, and the spread of women’s movements. The future of gender politics surrounding women’s policies in Korea depends on appropriately using these resources to achieve gender equality.

1 The data on 1998 and 1999 are missing or incomplete due to some difficulties involved in searching them. This can be attributed to the fact that the two consecutive years were the period of economic crisis during which it was difficult even to put women’s issues on the agenda in the National Assembly. Therefore, the two years are not included in the discussion of the results of analysis, but only their characteristics are briefly mentioned in the conclusion of this study.

2 Materials from the Christian Academy Study Group on Women and Society and Yeo-seong pyeong-u-hoe [Women’s Organization for Equality and Peace].

3 KWAU, Minju Yeoseong 9, 1990: 37.

4 KWAU, Jeonggi chonghoe, 1991.

5 KWAU, Jeonggi chonghoe, 1995.

6 Minju Yeoseong 18, 1995.

7 KWAU, Minju Yeoseong 17, 1994.

Christian Academy Study Group on Women and Society. Yeoseong-gwa sahoe [Women and Society]. Seoul, November 1978, December 1978, January 1979, February 1979, March to May 1979.

Gamson, William A. and Andre Modigliani. 1989. “Media Discourse and Public Opinion in Nuclear Power.” American Journal of Sociology 95: 1–38.

Jeong, Hyeon-baek. 1993. “Peonhwahaneun segye-wa yeoseong haebang undongron-ui mosaek: seong-gwa gyegeup munje-reul jungsim-euro” [The Search for Feminist Theories in the Changing World: Focusing on the Issues of Gender and Class]. Yeoseong-gwa sahoe [Women and Society] 4: 138–165.

Ji, Eun-hi and I-su Gang. 1988. “Han’guk yeoseong yeon-gu-ui jaseongjeok pyeongga” [A Reflective Evaluation of Women’s Studies in Korea]. In 80nyenodae inmunsahoeg-wahak-ui hyeondan-gye-wa jeonmang [The Present State of the Human and Social Sciences in the 1980s and their Prospect]. Seoul: Yeoksa bipyeong-sa.

Jo, Hi-yeon. ed. 1990. Han’guk sahoe undongsa [The History of Korean Social Movements]. Seoul: Juksan.

Kim, Bok-gyu. 2000. “Urinara yeoseong jeongchaek-ui byeonhwa-wa baljeon gwaje” [Changes in Women’s Policies of Korea and Tasks for Their Development]. Proceedings of the International Forum on the Government and Women’s Participation, the Korean Association of Public Administration, Seoul.

Kim, Elim. 1996. Yeoseong baljeon gibonbeop-ui naeyong-gwa gwaje [The Contents and Tasks of the Framework Act on Women’s Development]. Seoul: Korean Women’s Development Institute.

Kim, Mi-gyeong. 2000. “Yeoseong jeongchaek-gwa jeongbu yeokhal-ui byeonhwa” [Women’s Policies and the Changing Role of the Government]. Proceedings of the International Forum on the Government and Women’s Participation, the Association of Korean Public Administration.

Korean Women’s Associations United (KWAU) Special Committee for the Enactment of Laws on Sexual Violence. 1992. Hyeonhaeng seongpokryeok gwanryeon beop mu-eot-i munjein-ga [What are the Problems of the Current Laws on Sexual Violence]. Seoul: KWAU.

Korean Women’s Associations United (KWAU). 2000. Jeonggi chonghoe, 1990–2000 [Proceedings of the General Meetings, 1990–2000]. Seoul: KWAU.

Korean Women’s Hot Line. 1991. Seongpokryeok gwanryeon beop ipbeop-eul wihan gongcheonghoe jaryeojip [Collected Materials of the Public Hearings for the Legislation of the Laws on Sexual Violence].

Louie, Miriam Ching Yoon. 1995. “Minjung Feminism: Korean Women’s Movement for Gender and Class Liberation.” Women’s Studies International Forum 18: 417–430.

Miller, Carol and Shahra Razavi. 1998. “Gender Analysis: Alternative Paradigms.” Gender in Development Monograph Series #6. Geneva: UNDP.

Moser, Caroline O. 1993. Gender Planning and Development: Theory, Practice and Training, Routledge: London and New York.

Namnyeo pyeongdeung-eul wihan gyosu mo-im [The Group of Professors for the Sexual Equality Employment]. 1994. Jikjang nae seonghirong-eul eotteoke bol geot-in-ga? Seouldae seonghirong sageon-eul gyegi-ro [How to Perceive the Sexual Harassment in Workplace? With the Case of Seoul National University as a Momentum]. Proceedings of the Forum on Sexual Equality Employment, Seoul.

Sahoe-wa sasang [Society and Thought]. 1989. 80 nyeondae sahoe undong nonjaeng [The Controversies on Social Movement in the 1980s]. Seoul: Han-gil-sa.

Second Bureau of Political Affairs. 1998. Yeoseong jeongchaek gibon gyehoek [The Basic Plan on Women’s Policies]. Seoul: Second Bureau of Political Affairs.

Snow, David A. and Robert D. Benford. 1988. “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participation Mobilization.” International Movement Research 1: 197–217.

Snow, David A. and Robert D. Benford. 1992. “Master Frames and Cycles of Protests.” In Aldon Morris and Carol M. Muller. eds. Frontiers in Social Movement Theory. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Snow, David A., Burke Rochford Jr., Steven K. Worden, and Robert D. Benford. 1986. “Frame Alignment Processes, Micro Mobilization, and Movement Participation.” American Sociological Review 51: 464–481.

Yi, Hyojae. 1989. Han’guk-ui yeoseong undong [Women’s Movements in Korea: Yesterday and Today]. Seoul: Jeong-u-sa.

Yi, Mi-gyeong. 1998. “Yeosung undong –gwa minjuwha undong” [Women’s Movement and Democratization Movement] in Yeosungdanche yeonhap. Yeosungdanche sipny-unsa [The History of the Korean Women’s Association United 10 Years]. Seoul: Dongduk Women’s University.

Yi, Seung-hi. 1994. Yeoseong undong-gwa jeongchi iron [Women’s Movement and Political Theory]. Seoul: Nokdu.

Wells, Kenneth M. ed. 1995. South Korea’s Minjung Movement: The Culture and Politics of Dissidence. Manoa, Center for Korean Studies: University of Hawaii Press.