CHAPTER 6

Sell-Side M&A

The sale of a company, division, business, or collection of assets (“target”) is a major event for its owners (shareholders), management, employees, and other stakeholders. It is an intense, time-consuming process with high stakes, usually spanning several months. Consequently, the seller typically hires an investment bank and its team of trained professionals (“sell-side advisor”) to ensure that key objectives are met and a favorable result is achieved. In many cases, a seller turns to its bankers for a comprehensive financial analysis of the various strategic alternatives available to the target. These include a sale of all or part of the business, a recapitalization, an initial public offering, a spin-off of part of the business into a standalone company, or a continuation of the status quo.

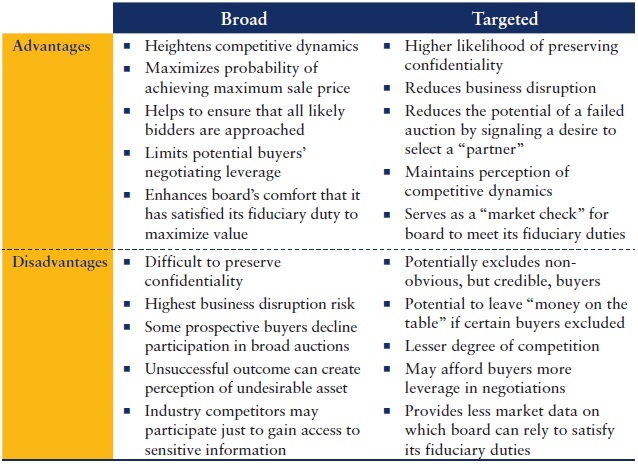

Once the decision to sell has been made, the sell-side advisor seeks to achieve the optimal mix of value maximization, speed of execution, and certainty of completion among other deal-specific considerations for the selling party. Accordingly, it is the sell-side advisor’s responsibility to identify the seller’s priorities from the onset and craft a tailored sale process. If the seller is largely indifferent toward confidentiality, timing, and potential business disruption, the advisor may consider running a broad auction, reaching out to as many potential interested parties as reasonably possible. This process, which is relatively neutral toward prospective buyers, is designed to maximize competitive dynamics and heighten the probability of finding the one buyer willing to offer the best value.

Alternatively, if speed, confidentiality, a particular transaction structure, and/or cultural fit are a priority for the seller, then a targeted auction, where only a select group of potential buyers is approached, or even a negotiated sale with a single party, may be more appropriate. Generally, an auction requires more upfront organization, marketing, process points, and resources than a negotiated sale with a single party. Consequently, this chapter focuses primarily on the auction process.

From an analytical perspective, a sell-side assignment requires the deal team to perform a comprehensive valuation of the target using the methodologies discussed in this book. In addition, in order to assess the potential purchase price that specific public strategic buyers may be willing to pay for the target, merger consequences analysis is performed with an emphasis on accretion/(dilution) and balance sheet effects (see Chapter 7). These valuation analyses are used to frame the seller’s price expectations, select the final buyer list, set guidelines for the range of acceptable bids, evaluate offers received, and ultimately guide negotiations of the final purchase price. Furthermore, for public targets (and certain private targets, depending on the situation) the sell-side advisor or an additional investment bank may be called upon to provide a fairness opinion.

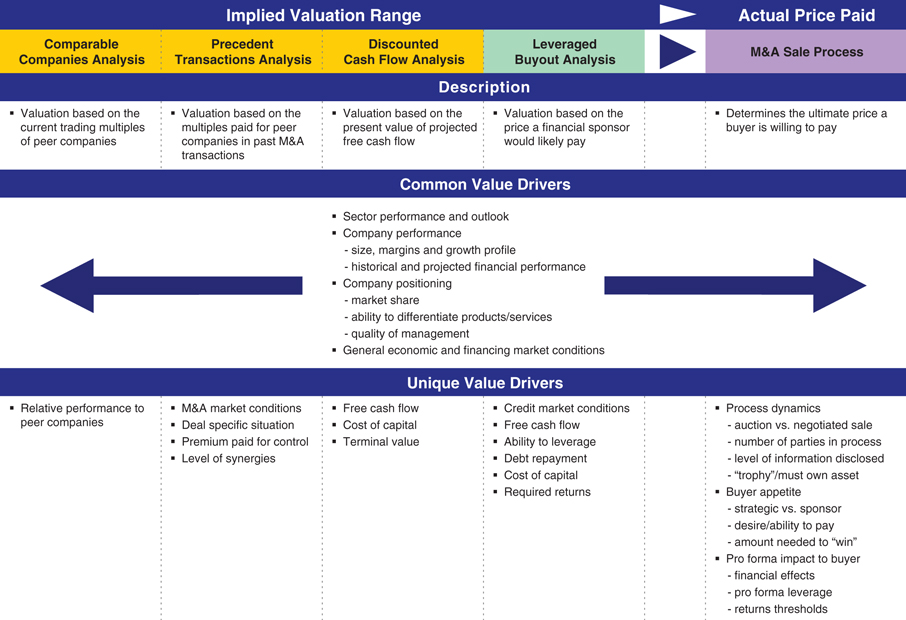

In discussing the process by which companies are bought and sold in the marketplace, we provide greater context to the topics discussed earlier in this book. In a sale process, theoretical valuation methodologies are ultimately tested in the market based on what a buyer will actually pay for the target (see Exhibit 6.1). An effective sell-side advisor seeks to push the bidders toward, or through, the upper endpoint of the implied valuation range for the target. On a fundamental level, this involves positioning the business properly and tailoring the sale process accordingly to maximize its value.

AUCTIONS

An auction is a staged process whereby a target is marketed to multiple prospective buyers (“buyers”, “bidders”, or “acquirers”). A well-run auction is designed to have a substantial positive impact on value (both price and terms) received by the seller due to a variety of factors related to the creation of a competitive environment. This environment encourages bidders to put forth their best offer on both price and terms, and helps increase speed of execution by encouraging quick action by bidders.

An auction provides a level of comfort that the market has been tested as well as a strong indicator of inherent value (supported by a fairness opinion, if required). At the same time, the auction process may have potential drawbacks, including information leakage into the market from bidders, negative impact on employee morale, reduced negotiating leverage once a “winner” is chosen (thereby encouraging re-trading1), and a “taint” of the business in the event of a failed auction. In addition, certain prospective buyers may decide not to participate in a broad auction given their reluctance to commit serious time and resources to a situation where they may perceive a relatively low likelihood of success.

A successful auction requires significant dedicated resources, experience, and expertise. Upfront, the deal team establishes a solid foundation through the preparation of compelling marketing materials, identification of potential deal issues, coaching of management, and selection of an appropriate group of prospective buyers. Once the auction commences, the sell-side advisor is entrusted with running as effective a process as possible. This involves the execution of a wide range of duties and functions in a tightly coordinated manner.

To ensure a successful outcome, investment banks commit a team of bankers that is responsible for the day-to-day execution of the transaction. Auctions also require significant time and attention from key members of the target’s management team, especially on the production of marketing materials and facilitation of buyer due diligence (e.g., management presentations, site visits, data room population, and responses to specific buyer inquiries). It is the sell-side advisor’s responsibility, however, to alleviate as much of this burden from the management team as possible.

In the later stages of an auction, a senior member of the sell-side advisory team typically negotiates directly with prospective buyers with the goal of encouraging them to put forth their best offer. As a result, sellers seek investment banks with extensive negotiation experience, sector expertise, and buyer relationships to run these auctions.

EXHIBIT 6.1 Valuation Paradigm

There are two primary types of auctions—broad and targeted.

- Broad Auction: As its name implies, a broad auction maximizes the universe of prospective buyers approached. This may involve contacting dozens of potential bidders, comprising both strategic buyers (potentially including direct competitors) and financial sponsors. By casting as wide a net as possible, a broad auction is designed to maximize competitive dynamics, thereby increasing the likelihood of finding the best possible offer. This type of process typically involves more upfront organization and marketing due to the larger number of bidders in the early stages of the process. It is also more difficult to maintain confidentiality as the process is susceptible to leaks to the public (including customers, suppliers, and competitors), which, in turn, can increase the potential for business disruption.2

- Targeted Auction: A targeted auction focuses on a few clearly defined buyers that have been identified as having a strong strategic fit and/or desire, as well as the financial capacity, to purchase the target. For example, it may be limited to a select group of strategic buyers. This process is more conducive to maintaining confidentiality and minimizing business disruption to the target. At the same time, there is greater risk of “leaving money on the table” by excluding a potential bidder that may be willing to pay a higher price.

Exhibit 6.2 provides a summary of the potential advantages and disadvantages of each process.

EXHIBIT 6.2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Broad and Targeted Auctions

Auction Structure

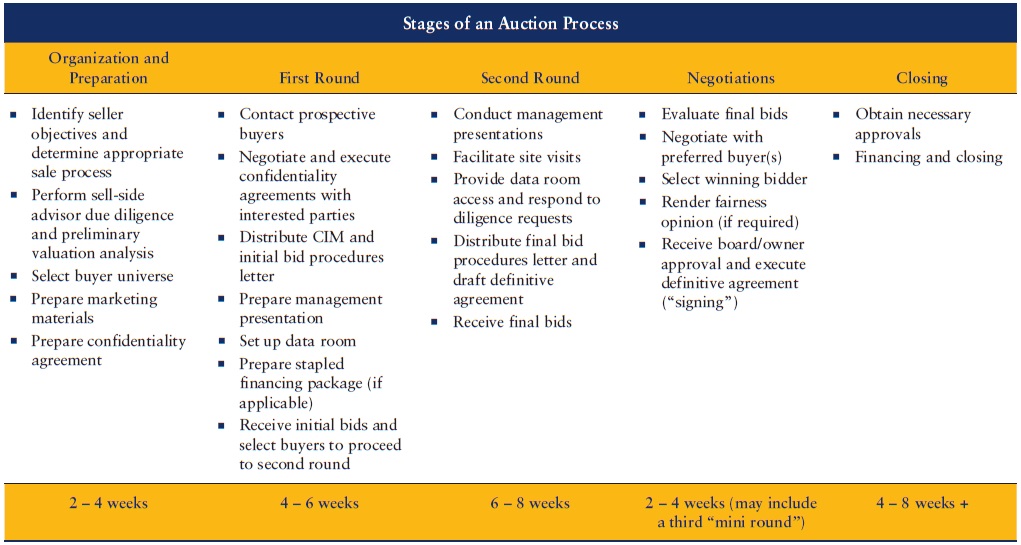

The traditional auction is structured as a two-round bidding process that generally spans three to six months (or longer) from the decision to sell until the signing of a definitive purchase/sale agreement (“definitive agreement”) with the winning bidder (see Exhibit 6.3). The timing of the post-signing (“closing”) period depends on a variety of factors not specific to an auction, such as regulatory approvals and/or third-party consents, financing, and shareholder approval. The entire auction process consists of multiple stages and discrete milestones within each of these stages. There are numerous variations within this structure that allow the sell-side advisor to customize the process for a given situation.

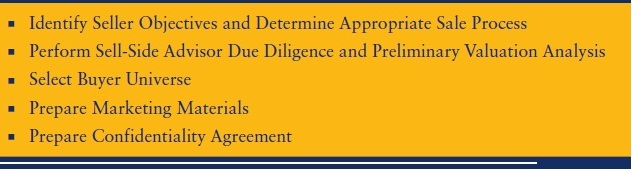

ORGANIZATION AND PREPARATION

Identify Seller Objectives and Determine Appropriate Sale Process

At the onset of an auction, the sell-side advisor works with the seller to identify its objectives, determine the appropriate sale process to conduct, and develop a process roadmap. The advisor must first gain a clear understanding of the seller’s priorities so as to tailor the process accordingly. Perhaps the most basic decision is how many prospective buyers to approach (i.e., whether to run a broad or targeted auction).

As previously discussed, while a broad auction may be more appealing to a seller in certain circumstances, a targeted auction may better satisfy certain “softer” needs, such as speed to transaction closing, heightened confidentiality, a tailored transaction structure, and less risk of business disruption. Furthermore, the target’s board of directors must also take into account its fiduciary duties in deciding whether to conduct a broad or targeted auction.3 At this point, the deal team drafts a detailed process timeline and roadmap, including target dates for significant milestones, such as launch, receipt of initial and final bids, contract signing, and deal closing.

EXHIBIT 6.3 Stages of an Auction Process

Perform Sell-Side Advisor Due Diligence and PreliminaryValuation Analysis

Sale process preparation begins with extensive due diligence on the part of the sell-side advisor. This typically kicks off with an in-depth session with target management. The sell-side advisor must have a comprehensive understanding of the target’s business and the management team’s vision prior to drafting marketing materials and communicating with prospective buyers. Due diligence facilitates the advisor’s ability to properly position the target and articulate its investment merits. It also allows for the identification of potential buyer concerns or issues ranging from growth sustainability, margin trends, and customer concentration to environmental matters, contingent liabilities, and labor relations.

A key portion of sell-side diligence centers on ensuring that the advisor understands and provides perspective on the assumptions that drive management’s financial model. This diligence is particularly important as the model forms the basis for the valuation work that will be performed by prospective buyers. Therefore, the sell-side advisor must approach the target’s financial projections from a buyer’s perspective and gain comfort with the numbers, trends, and key assumptions driving them.

An effective sell-side advisor understands the valuation methodologies that buyers will use in their analysis (e.g., comparable companies, precedent transactions, DCF analysis, and LBO analysis) and performs this work beforehand to establish a valuation range benchmark. For specific public buyers, accretion/(dilution) analysis and balance sheet effects are also performed to assess their ability to pay. Ultimately, however, the target’s implied valuation based on these methodologies needs to be weighed against market appetite. Furthermore, the actual value received in a transaction must be assessed on the basis of structure and terms, in addition to price.

The sell-side advisor may recommend that the target commissions a Quality of Earnings (QoE) report or market study. A QoE is a financial report performed by an accounting firm, typically national or super-regional, to assess and validate the operating earnings profile of the target. The goal is to help provide potential buyers and their financing sources comfort from the third-party assessment, although they also typically have their own QoE report compiled. In general, QoEs have become increasingly common in the M&A marketplace. Similarly, a third-party market study on the target’s core sub-sector and key end markets might be commissioned to help build buyer conviction in the story.

In the event a stapled financing package is offered to buyers, a separate financing deal team is formed (either at the sell-side advisor’s institution or another bank) to begin conducting due diligence in parallel with the sell-side team. Their analysis is used to craft a generic pre-packaged financing structure to support the purchase of the target.4 The initial financing package terms are used as guideposts to derive an implied LBO analysis valuation.

Select Buyer Universe

The selection of an appropriate group of prospective buyers, and compilation of corresponding contact information, is a critical part of the organization and preparation stage. At the extreme, the omission or inclusion of a potential buyer (or buyers) can mean the difference between a successful or failed auction. Sell-side advisors are selected in large part on the basis of their sector knowledge, including their relationships with, and insights on, prospective buyers. Correspondingly, the deal team is expected both to identify the appropriate buyers and effectively market the target to them.

In a broad auction, the buyer list typically includes a mix of strategic buyers and financial sponsors. The sell-side advisor evaluates each buyer on a broad range of criteria pertinent to its likelihood and ability to acquire the target at an acceptable value. When evaluating strategic buyers, the banker looks first and foremost at strategic fit, including potential synergies. Financial capacity or “ability to pay”—which is typically dependent on size, balance sheet strength, access to financing, and risk appetite—is also closely scrutinized. Other factors play a role in assessing potential strategic bidders, such as cultural fit, M&A track record, existing management’s role going forward, relative and pro forma market position (including antitrust concerns), and the effects on existing customer and supplier relationships.

When evaluating potential financial sponsor buyers, key criteria include investment strategy/focus, sector expertise, fund size,5 track record, fit within existing investment portfolio, fund life cycle,6 and the ability to obtain financing. As part of this process, the deal team looks for sponsors with existing portfolio companies that may serve as an attractive combination candidate for the target. For certain large transactions, sponsors may look to partner with others, or enhance financial capacity through co-investments from LPs.

In many cases, a strategic buyer is able to pay a higher price than a sponsor due to the ability to realize synergies and a lower cost of capital. Depending on the prevailing capital markets conditions, a strategic buyer may also present less financing risk than a sponsor.

Once the sell-side advisor has compiled a list of prospective buyers, it presents them to the seller for final sign-off.

Prepare Marketing Materials

Marketing materials often represent the first formal introduction of the target to prospective buyers. They are essential for sparking buyer interest and creating a favorable first impression. Effective marketing materials present the target’s investment highlights in a succinct manner, while also providing supporting evidence and basic operational, financial, and other essential business information. The two main marketing documents for the first round of an auction process are the teaser and confidential information memorandum/presentation (CIM or CIP). The sell-side advisors take the lead on producing these materials with substantial input from management. Legal counsel also reviews these documents, as well as the management presentation, for various potential legal concerns (e.g., antitrust7).

A code name for the target is also typically introduced at this point, especially as buyer outreach nears. The code name is meant to maintain the confidentiality of the company as well as the process itself. The actual code name is often chosen by the bankers in collaboration with the company, although some banks utilize a random, computer-driven system. Code names are also assigned to individual buyers, particularly later in the process as the universe narrows.

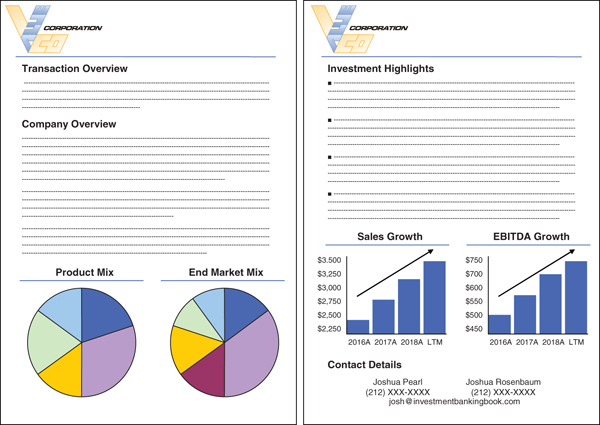

Teaser The teaser is the first marketing document presented to prospective buyers, typically prior to execution of a confidentiality agreement. It is designed to inform buyers and generate sufficient interest for them to undertake further work and potentially submit a bid. The teaser is generally a brief one- or two-page synopsis of the target, including a company overview, investment highlights, and summary financial information. It also contains contact information for the bankers running the sell-side process so that interested parties may respond.

Teasers vary in terms of format and content in accordance with the target, sector, sale process, advisor, and potential seller sensitivities. For public companies, Regulation FD concerns govern the content of the teaser (i.e., no material non-public information) as well as the nature of the buyer contacts themselves.8 Exhibit 6.4 displays an illustrative teaser template as might be presented to prospective buyers.

EXHIBIT 6.4 Sample Teaser

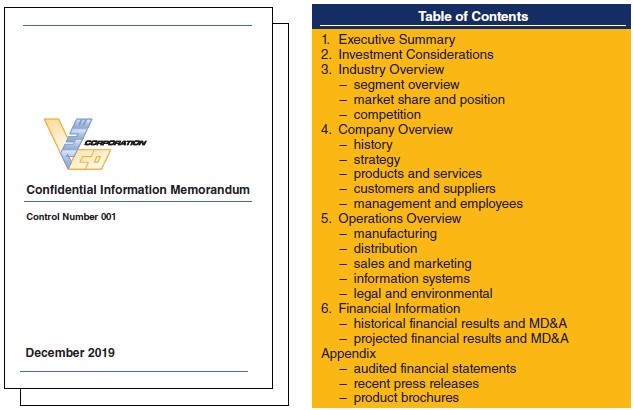

Confidential Information Memorandum The CIM is a detailed written description of the target (often 50+ pages) that serves as the primary marketing document for the target in an auction. Increasingly, it comes in the form of a PowerPoint presentation and is referred to as a CIP (Confidential Information Presentation) instead of the traditional portrait/textual format of a CIM. The deal team, in collaboration with the target’s management, spends significant time and resources drafting the CIM before it is deemed ready for distribution to prospective buyers. In the event the seller is a financial sponsor (e.g., selling a portfolio company), the sponsor’s investment professionals typically also provide input.

Like teasers, CIMs vary in terms of format and content depending on situation-specific circumstances. There are, however, certain generally accepted guidelines for content, as reflected in Exhibit 6.5. The CIM typically contains an executive summary, investment considerations, and detailed information about the target, as well as its sector, customers and suppliers (often presented on an anonymous basis), operations, facilities, management, and employees. A modified version of the CIM may be prepared for designated strategic buyers, namely competitors with whom the seller may be concerned about sharing certain sensitive information.

EXHIBIT 6.5 Confidential Information Memorandum Table of Contents

Financial Information The CIM contains a detailed financial section presenting historical and projected financial information with accompanying narrative explaining both past and expected future performance (MD&A). This data forms the basis for the preliminary valuation analysis performed by prospective buyers.

Consequently, the deal team spends a great deal of time working with the target’s CFO, treasurer, and/or finance team (and division heads, as appropriate) on the CIM’s financial section. This process involves normalizing the historical financials (e.g., for acquisitions, divestitures, and other one-time and/or extraordinary items) and crafting an accompanying MD&A. The sell-side advisor also helps develop a set of projections, typically five years in length, as well as supporting assumptions and narrative. Given the importance of the projections in framing valuation, prospective buyers subject them to intense scrutiny. Therefore, the sell-side advisor must gain sufficient comfort that the numbers are realistic and defensible in the face of potential buyer skepticism.

In some cases, the CIM provides additional financial information to help guide buyers toward potential growth/acquisition scenarios for the target. For example, the sell-side advisor may work with management to compile a list of potential acquisition opportunities for inclusion in the CIM (typically on an anonymous basis), including their incremental sales and EBITDA contributions. This information is designed to provide potential buyers with perspective on the potential upside represented by using the target as a growth platform so they can craft their bids accordingly.

Prepare Confidentiality Agreement

A confidentiality agreement (CA) is a legally binding contract between the target and prospective buyers that governs the sharing of confidential company information. The CA is typically drafted by the target’s counsel and distributed to prospective buyers along with the teaser, with the understanding that the receipt of more detailed information is conditioned on execution of the CA.

A typical CA includes provisions governing the following:

- Use of information – states that all information furnished by the seller, whether oral or written, is considered proprietary information and should be treated as confidential and used solely to make a decision regarding the proposed transaction

- Term – designates the time period during which the confidentiality restrictions remain in effect9

- Permitted disclosures – outline under what limited circumstances the prospective buyer is permitted to disclose the confidential information provided; also prohibits disclosure that the two parties are in negotiations

- Return of confidential information – mandates the return or destruction of all provided documents once the prospective buyer exits the process

- Non-solicitation/no hire – prevents prospective buyers from soliciting to hire (or hiring) target employees for a designated time period

- Standstill agreement – for public targets, precludes prospective buyers from making unsolicited offers or purchases of the target’s shares, or seeking to control/influence the target’s management, board of directors, or policies for a specified period of time (typically six months to two years)

- Restrictions on clubbing – prevents prospective buyers from collaborating with each other or with outside financial sponsors/equity providers without the prior consent of the target (in order to preserve a competitive environment)

FIRST ROUND

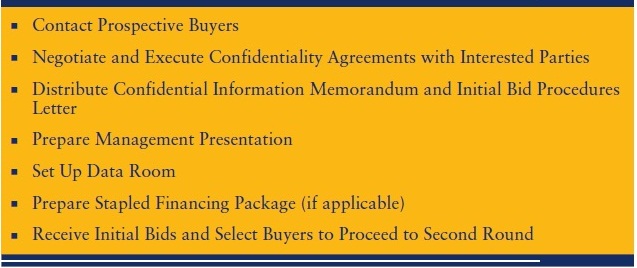

Contact Prospective Buyers

The first round begins with the contacting of prospective buyers, which marks the formal launch of the auction process. This typically takes the form of a scripted phone call to each prospective buyer by a senior member of the sell-side advisory deal team (either an M&A banker or the coverage banker that maintains the relationship with the particular buyer), followed by the delivery of the teaser and CA.10 The sell-side advisor keeps a detailed record of all interactions with prospective buyers, called a contact log, which is used as a tool to monitor a buyer’s activity level and provide a record of the process.

Negotiate and Execute Confidentiality Agreement with Interested Parties

Upon receipt of the CA, a prospective buyer presents the document to its legal counsel for review. In the likely event there are comments, the buyer’s counsel and seller’s counsel negotiate the CA with input from their respective clients. Following execution of the CA, the sell-side advisor distributes the CIM and initial bid procedures letter to a prospective buyer.11

Distribute Confidential Information Memorandum and Initial BidProcedures Letter

Prospective buyers are typically given several weeks to review the CIM,12 study the target and its sector, and conduct preliminary financial analysis prior to submitting their initial non-binding bids. During this period, the sell-side advisor maintains a dialogue with the prospective buyers, often providing additional color, guidance, and materials, as appropriate, on a case-by-case basis.

Depending on their level of interest, prospective buyers may also engage investment banks (as M&A buy-side advisors and/or financing providers), other external financing sources, and consultants at this stage. Buy-side advisors play an important role in helping their client, whether a strategic buyer or a financial sponsor, assess the target from a valuation perspective and determine a competitive initial bid price. Financing sources help assess both the buyer’s and target’s ability to support a given capital structure and provide their clients with data points on amounts, terms, and availability of financing. This financing data is used to help frame the valuation analysis performed by the buyer. Consultants provide perspective on key business and market opportunities, as well as potential risks and areas of operational improvement for the target.

Initial Bid Procedures Letter The initial bid procedures letter, which typically is sent out to prospective buyers following distribution of the CIM, states the date and time by which interested parties must submit their written, non-binding preliminary indications of interest (“first round bids”). It also defines the exact information that should be included in the bid, such as:

- Indicative purchase price (buyers typically present as a range) and form of consideration (cash vs. stock mix)13

- Key assumptions to arrive at the stated purchase price

- Structural and other considerations

- Information on financing sources

- Treatment of management and employees

- Timing for completing a deal and diligence that must be performed

- Key conditions to signing and closing

- Required approvals (e.g., board/investment committee, shareholder, regulatory)

- Buyer contact information and advisors

Prepare Management Presentation

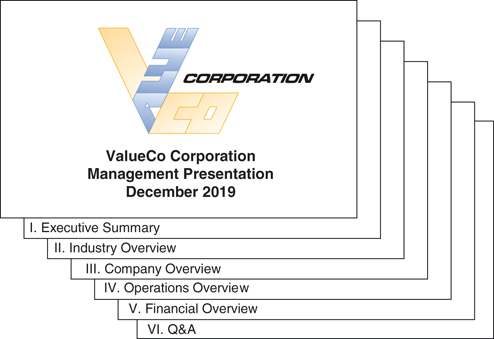

The management presentation is typically structured as a slideshow with accompanying hardcopy handout. The sell-side advisor takes the lead on preparing these materials with substantial input from management. In parallel, they determine the speaker lineup for each slide of the presentation, as well as key messages. The bankers also develop a list of “challenge” questions and accompanying answers for each slide in anticipation of buyer focus areas. Depending on the management team, the rehearsal process for the presentations (“dry runs”) may be intense and time-consuming. The management presentation slideshow needs to be completed by the start of the second round when the actual meetings with buyers begin.

The presentation format generally maps to that of the CIM/CIP, but is more crisp and concise. It also tends to contain an additional level of detail, analysis, and insight more conducive to an interactive session with management and later-stage due diligence. Given buyers have already demonstrated their interest through an initial bid and the number of parties has been culled for the second round, management is more willing to share incremental detail, especially regarding growth initiatives. A typical management presentation outline is shown in Exhibit 6.6.

EXHIBIT 6.6 Sample Management Presentation Outline

Set Up Data Room

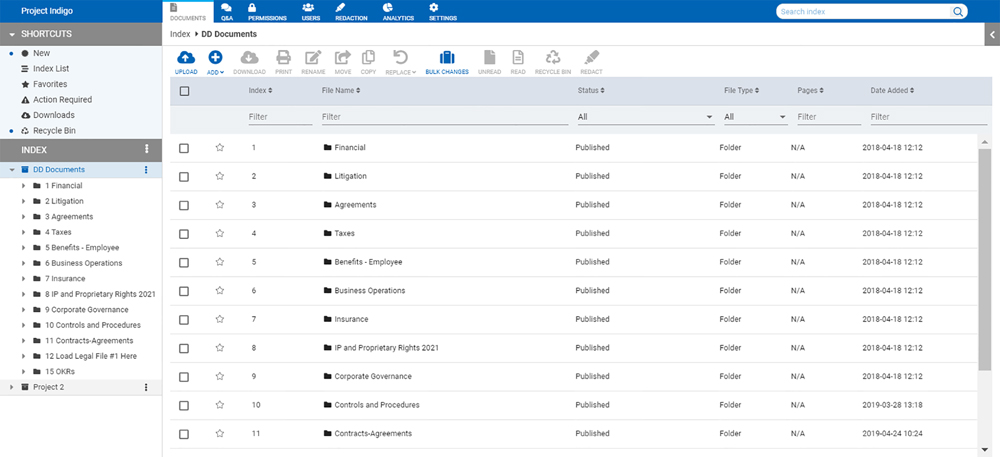

The data room serves as the hub for the buyer due diligence that takes place in the second round of the process. It is typically an online repository, where comprehensive, detailed information about the target is stored, catalogued, and made available to pre-screened bidders.14 A well-organized data room facilitates buyer due diligence, helps keep the sale process on schedule, and inspires confidence in bidders. Most prominent data room service providers also generate detailed analytics for the sell-side bankers regarding the frequency of log-ins, number of documents reviewed, and other activity by each bidder in the data room, which helps the deal team determine the interest level of each bidder. While most data rooms follow certain basic guidelines, they may vary greatly in terms of content and accessibility depending on the company and confidentiality concerns.

Data rooms, such as those provided by Datasite, generally contain a broad base of essential company information, documentation, and analyses. In essence, the data room is designed to provide a comprehensive set of information relevant for buyers to make an informed investment decision about the target, such as detailed financial reports, industry reports, and consulting studies. It also contains detailed company-specific information such as customer and supplier lists, labor contracts, purchase contracts, description and terms of outstanding debt, lease and pension contracts, and environmental compliance information (see Exhibit 6.7). At the same time, the content must reflect any concerns over sharing sensitive data for competitive reasons.15

The data room also allows the buyer (together with its legal counsel, accountants, and other advisors) to perform more detailed confirmatory due diligence prior to consummating a transaction. This due diligence includes reviewing charters/bylaws, outstanding litigation, regulatory information, environmental reports, and property deeds, for example. It is typically conducted only after a buyer has decided to seriously pursue the acquisition.

The sell-side bankers work closely with the target’s legal counsel and selected employees to organize, populate, and manage the data room. While the data room is continuously updated and refreshed with new information throughout the auction, the aim is to have a basic data foundation in place by the start of the second round. Access to the data room is typically granted to those buyers that move forward after first round bids, prior to, or coinciding with, their attendance at the management presentation.

EXHIBIT 6.7 Datasite Data Room Document Index

Prepare Stapled Financing Package (if applicable)

The investment bank running the auction process (or sometimes a “partner” bank) may prepare a “pre-packaged” financing structure in support of the target being sold. Commonly referred to as a staple, it is targeted toward financial sponsor buyers and is typically only provided for private companies.16 Although prospective buyers are not required to use the staple, historically it has positioned the sell-side advisor to play a role in the deal’s financing. Often, however, buyers seek their own financing sources to match or “beat” the staple. Alternatively, certain buyers may choose to use less leverage than provided by the staple.

To avoid a potential conflict of interest, the investment bank running the M&A sell-side sets up a separate financing team distinct from the sell-side advisory team to run the staple process. This financing team is tasked with providing an objective assessment of the target’s leverage capacity. This team conducts due diligence and financial analysis separately from (but often in parallel with) the M&A team and craft a financing structure that is presented to the bank’s internal credit committee for approval. This financing package is then presented to the seller for sign-off, after which it is offered to prospective buyers as part of the sale process.

The basic terms of the staple are typically communicated verbally to buyers in advance of the first round bid date so they can use that information to help frame their bids. Staple term sheets and/or actual financing commitments are not provided until later in the auction’s second round, prior to submission of final bids. Those investment banks without debt underwriting capabilities (e.g., middle market or boutique investment banks) may pair up with a partner bank capable of providing a staple, if requested by the client.

While buyers are not obligated to use the staple, it is designed to send a strong signal of support from the sell-side bank and provide comfort that the necessary financing will be available to buyers for the acquisition. The staple can also be used to limit buyers’ ability to speak with multiple financing sources, thereby reducing chatter in the market and helping preserve the integrity of the sale process. In this vein, it may serve to compress the timing between the start of the auction’s second round and signing of a definitive agreement by eliminating duplicate buyer financing due diligence. To some extent, the staple helps establish a valuation floor for the target by setting a leverage level that can be used as the basis for extrapolating a purchase price. For example, a staple offering debt financing equal to 5.5x LTM EBITDA with a 30% minimum equity contribution would imply a purchase price of approximately 8x LTM EBITDA.

Receive Initial Bids and Select Buyers to Proceed to Second Round

On the first round bid date, the sell-side advisor receives initial indications of interest from prospective buyers. Over the next few days, the deal team conducts a thorough analysis of the bids received, assessing indicative purchase price as well as key deal terms and other stated conditions. There may also be dialogue with certain buyers at this point, typically focused on seeking clarification on key bid points.

An effective sell-side advisor is able to discern which bids are “real” (i.e., less likely to be re-traded). Furthermore, it may be apparent that certain bidders are simply trying to get a free look at the target without any serious intent to consummate a transaction. As previously discussed, the advisor’s past deal experience, specific sector expertise, familiarity with the buyers, and knowledge regarding bidder engagement (including via the data room analytics) are key in this respect.

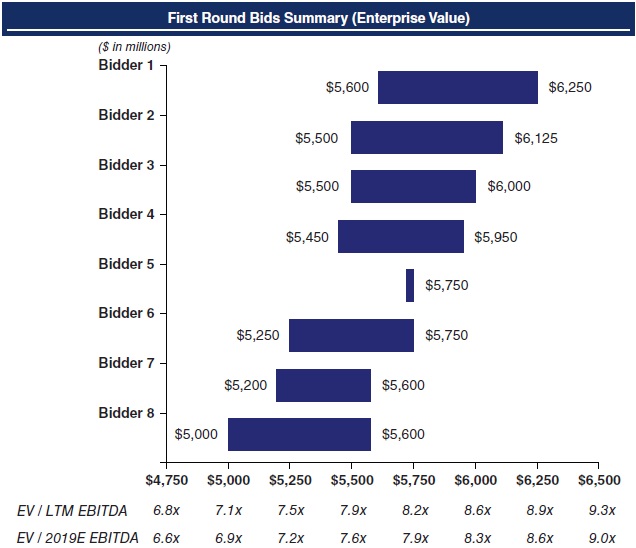

Once this analysis is completed, the bid information is summarized and presented to the seller along with a recommendation on which buyers to invite to the second round (see Exhibit 6.8 for a sample graphical presentation of purchase price ranges from bidders). The final decision regarding which buyers should advance, however, is made by the seller in consultation with its advisors.

Valuation Perspectives – Strategic Buyers vs. Financial Sponsors As discussed in Chapters 4 and 5, financial sponsors use LBO analysis and the implied IRRs and cash returns, together with guidance from the other methodologies discussed in this book, to frame their purchase price range. The CIM financial projections and an initial assumed financing structure (e.g., a staple, if provided, or indicative terms from a financing provider) form the basis for the sponsor in formulating a first round bid. The sell-side advisor performs its own LBO analysis in parallel to assess the sponsor bids.

While strategic buyers also rely on the fundamental methodologies discussed in this book to establish a valuation range for a potential acquisition target, they typically employ additional techniques. For example, public strategics use accretion/(dilution) analysis to measure the pro forma effects of the transaction on EPS, assuming a given purchase price and financing structure (see Chapter 7). Therefore, the sell-side advisor performs similar analysis in parallel to determine the maximum price a given buyer may be willing to pay. This requires making assumptions regarding each specific acquirer’s financing mix and cost, as well as synergies.

EXHIBIT 6.8 First Round Bids Summary

SECOND ROUND

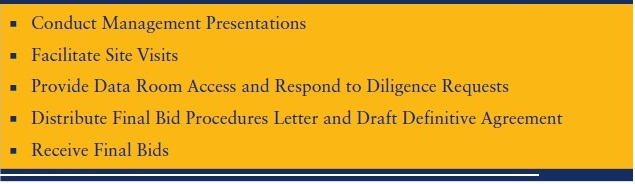

The second round of the auction centers on facilitating the prospective buyers’ ability to conduct detailed due diligence and analysis so they can submit strong, final (and ideally) binding bids by the set due date. The diligence process is meant to be exhaustive, typically spanning several weeks, depending on the target’s size, sector, geographies, and ownership. The length and nature of the diligence process often differs based on the buyer’s profile. A strategic buyer that is a direct competitor of the target, for example, may already have in-depth knowledge of the business and therefore focus on a more limited scope of company-specific information.17 For a financial sponsor that is unfamiliar with the target and its sector, however, due diligence may take longer. As a result, sponsors often seek professional advice from hired consultants, operational advisors, and other industry experts to assist in their due diligence.

The sell-side advisor plays a central role during the second round by coordinating management presentations and facility site visits, monitoring the data room, and maintaining regular dialogue with prospective buyers. During this period, each prospective buyer is afforded time with senior management, a cornerstone of the due diligence process. The buyers also comb through the target’s data room, visit key facilities, conduct follow-up diligence sessions with key company officers, and perform detailed financial and industry analyses. Prospective buyers are given sufficient time to complete their due diligence, secure financing, craft a final bid price and proposed transaction structure, and submit a markup of the draft definitive agreement. At the same time, the sell-side advisor seeks to maintain a competitive atmosphere and keep the process moving by limiting the time available for due diligence, providing access to management, and ensuring bidders move in accordance with the established schedule.

Conduct Management Presentations

The management presentation typically marks the formal kickoff of the second round, often spanning a full business day. At the presentation, the target’s management team presents each prospective buyer with a detailed overview of the company. This involves an in-depth discussion of topics ranging from basic business, industry, and financial information to competitive positioning, future strategy, growth opportunities, synergies (if appropriate), and financial projections.

The core team presenting typically consists of the target’s CEO, CFO, and key division heads or other operational executives, as appropriate. The presentation is intended to be interactive, with Q&A encouraged and expected. It is customary for prospective buyers to bring their investment banking advisors and financing sources, as well as industry and/or operational consultants, to the management presentation so they can conduct their due diligence in parallel and provide insight.

The management presentation is often the buyer’s first meeting with management. Therefore, this forum represents a unique opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the business and its future prospects directly from the individuals who know the company best. Furthermore, the management team itself typically represents a substantial portion of the target’s value proposition and is therefore a core diligence item. The presentation is also a chance for prospective buyers to gain a sense of “fit” between themselves and management.

Facilitate Site Visits

Site visits are an essential component of buyer due diligence, providing a firsthand view of the target’s operations. Often, the management presentation itself takes place at, or near, a key company facility and includes a site visit as part of the agenda. Prospective buyers may also request visits to multiple sites to better understand the target’s business and assets. The typical site visit involves a guided tour of a key target facility, such as a manufacturing plant, distribution center, and/or sales office. The guided tours are generally led by the local manager of the given facility, often accompanied by a sub-set of senior management and a member of the sell-side advisory team. They tend to be highly interactive as key buyer representatives, together with their advisors and consultants, use this opportunity to ask detailed questions about the target’s operations. In many cases, the seller does not reveal the true purpose of the site visit internally as employees outside a selected group of senior managers are often unaware a sale process is underway.

Provide Data Room Access and Respond to Diligence Requests

In conjunction with the management presentation and site visits, prospective buyers are provided access to the data room. The data room contains detailed information about all aspects of the target (e.g., business, financial, accounting, tax, legal, insurance, environmental, information technology, and property). Serious bidders dedicate significant resources to ensure their due diligence is as thorough as possible. They often enlist a full team of accountants, attorneys, consultants, and other functional specialists to conduct a comprehensive investigation of company data. Through rigorous data analysis and interpretation, the buyer seeks to identify the key opportunities and risks presented by the target, thereby framing the acquisition rationale and investment thesis. This process also enables the buyer to identify those outstanding items and issues that should be satisfied prior to submitting a formal bid and/or specifically relating to the seller’s proposed definitive agreement.

Some online data rooms allow users to download documents, while others only permit screenshots (that may or may not be printable). Data room access may be tailored to individual bidders or even specific members of the bidder teams (e.g., limited to legal counsel only). For example, strategic buyers that compete directly with the target may be restricted from viewing sensitive competitive information (e.g., customer and supplier contracts), at least until the later stages when the preferred bidder is selected. The sell-side advisor monitors data room access throughout the process, including the viewing of specific items. This enables them to track buyer interest and activity, draw conclusions, and take action accordingly.

As prospective buyers pore through the data, they identify key issues, opportunities, and risks that require follow-up inquiry. The sell-side advisor plays an active role in this respect, channeling follow-up due diligence requests to the appropriate individuals at the target and facilitating an orderly and timely response.

Distribute Final Bid Procedures Letter and Draft Definitive Agreement

During the second round, the final bid procedures letter is distributed to the remaining prospective buyers often along with the draft definitive agreement. As part of their final bid package, prospective buyers submit a markup of the draft definitive agreement together with a cover letter detailing their proposal in response to the items outlined in the final bid procedures letter.

Final Bid Procedures Letter Similar to the initial bid procedures letter in the first round, the final bid procedures letter outlines the exact date and guidelines for submitting a final, legally binding bid package. As would be expected, however, the requirements for the final bid are more stringent, including:

- Purchase price details, including the exact dollar amount of the offer and form of purchase consideration (e.g., cash versus stock)18

- Markup of the draft definitive agreement provided by the seller in a form that the buyer would be willing to sign

- Evidence of committed financing (e.g., debt or equity commitment letters) and information on financing sources

- Attestation to completion of due diligence (or very limited confirmatory due diligence required)

- Attestation that the offer is binding and will remain open for a designated period of time

- Required regulatory approvals and timeline for completion

- Board of directors or investment committee approvals (if appropriate)

- Estimated time to sign and close the transaction

- Buyer contact information

Definitive Agreement The definitive agreement is a legally binding contract between a buyer and seller detailing the terms and conditions of the sale transaction. In an auction, the first draft is prepared by the seller’s legal counsel in collaboration with the seller and its bankers. It is distributed to prospective buyers (and their legal counsel) during the second round—often toward the end of the diligence process. The buyer’s counsel then provides specific comments on the draft document (largely informed by the buyer’s second round diligence efforts) and submits it as part of the final bid package. In many cases, the sell-side advisor requests the submission of a mark-up prior to the final bid to provide additional time for review and negotiation.

The definitive agreement is a critical part of the bid package and overall value proposition. Key business, economic, and structural terms may represent a sizable percentage of the purchase price and prove invaluable to the seller. It is not uncommon for an otherwise attractive bid price to fall apart due to failure to reach agreement on key contract terms.

Therefore, the sell-side advisor and legal counsel work to encourage each buyer to submit a form of revised definitive agreement that they would be willing to sign immediately if the bid is accepted. This requires substantive discussions between the buyer’s and seller’s legal counsel in advance to pre-negotiate certain terms. The sell-side advisor’s goal is to obtain the most definitive, least conditional revised definitive agreement possible prior to submission to the seller. This aids the seller in evaluating the competing contract terms and avoiding a situation where the buyer has “hold-up” power on key contract terms after emerging as the leading or “winning bidder”.

Definitive agreements involving public and private companies differ in terms of content, although the basic format of the document is the same, containing an overview of the transaction structure/deal mechanics, representations and warranties (“reps and warranties”, or “R&W”), pre-closing commitments (including covenants), closing conditions, termination provisions, and indemnities (if applicable),19 as well as associated disclosure schedules and exhibits.20 Exhibit 6.9 provides an overview of some of the key sections of a definitive agreement.

Receive Final Bids

Upon conclusion of the second round, prospective buyers submit their final bid packages to the sell-side advisor by the date indicated in the final bid procedures letter. These bids are expected to be final with minimal conditionality, or “outs”, such as the need for additional due diligence or firming up of financing commitments. In practice, the sell-side advisor works with viable buyers throughout the second round to firm up their bids as much as possible before submission.

| Definitive Agreement Summary | |

| Transaction Structure/Deal Mechanics |

|

| Representations and Warranties |

|

| Pre-Closing Commitments (Including Covenants) |

|

| Other Agreements |

|

| Closing Conditions |

|

| Termination Provisions |

|

| Indemnification |

|

(a)An acquisition of a company can be effected in several different ways, depending on the particular tax, legal, and other preferences. In a basic merger transaction, the acquirer and target merge into one surviving entity. More often, a subsidiary of the acquirer is formed, and that subsidiary merges with the target (with the resulting merged entity becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of the acquirer). In a basic stock sale transaction, the acquirer (or a subsidiary thereof) acquires 100% of the capital stock (or other equity interests) of the target. In a basic asset sale transaction, the acquirer (or a subsidiary thereof) purchases all, or substantially all, of the assets of the target and, depending on the situation, may assume all, or some of, the liabilities of the target associated with the acquired assets. In an asset sale, the target survives the transaction and may choose to either continue operations or dissolve after distributing the proceeds from the sale to its equity holders.

(b)Also called material adverse effect (MAE). This is a highly negotiated provision in the definitive agreement, which may permit a buyer to avoid closing the transaction in the event that a substantial adverse situation is discovered after signing or a detrimental post-signing event occurs that affects the target. MAE has been interpreted by the courts to mean, in most circumstances, a very significant problem that is likely to be lasting rather than short term. As a practical matter, it has proven difficult for buyers in recent years to establish that a MAC has occurred such that the buyer is entitled to terminate the deal.

(c)Receipt of financing is usually not a condition to closing, although this may be subject to change in accordance with market conditions.

(d)The representations usually need to be true only to some forgiving standard, such as “true in all material respects” or, more commonly, “true in all respects except for such inaccuracies that, taken together, do not amount to a material adverse effect”. See footnote (b) for an explanation of the material adverse effect condition.

(e)As the buyer only makes very limited reps and warranties in the definitive agreement, it is rare that any indemnification payments are ever paid by a buyer to a seller.

EXHIBIT 6.9 Key Sections of a Definitive Agreement

NEGOTIATIONS

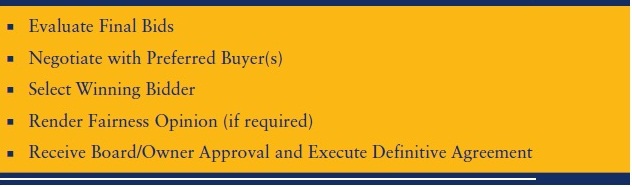

Evaluate Final Bids

The sell-side advisor works together with the seller and its legal counsel to conduct a thorough analysis of the price, structure, contract, and conditionality of the final bids. Purchase price is assessed within the context of the first round bids and the target’s recent financial performance, as well as the valuation work performed by the sell-side advisor. The deemed binding nature of each final bid, or lack thereof, is also carefully weighed in assessing its strength. For example, a bid with a superior headline offer price, but a weaker contract and significant conditionality, may be deemed inferior to a firmer bid at a lower price. Once this analysis is completed, the seller selects a preferred party or parties with whom to negotiate a definitive agreement.

Negotiate with Preferred Buyer(s)

Often, the sell-side advisor recommends that the seller negotiate with two (or more) parties, especially if the bid packages are relatively close and/or there are issues with the higher bidder’s markup of the definitive agreement. Skillful negotiation on the part of the sell-side advisor at this stage can meaningfully improve the final bid terms. While tactics vary broadly, the advisor seeks to maintain a level playing field so as not to advantage one bidder over another and maximize the competitiveness of the final stage of the process. During these final negotiations, the advisor works intensely with the bidders to clear away any remaining confirmatory diligence items (if any) while firming up key terms in the definitive agreement (including price), with the goal of driving one bidder to differentiate itself.

Select Winning Bidder

The sell-side advisor and legal counsel negotiate a final definitive agreement with the winning bidder, which is then presented to the target’s board of directors for approval. Not all auctions result in a successful sale. The seller normally reserves the right to reject any and all bids as inadequate at every stage of the process. Similarly, each prospective buyer has the right to withdraw from the process at any time prior to the execution of a binding definitive agreement. An auction that fails to produce a sale is commonly referred to as a “busted” or “failed” process.

Render Fairness Opinion (if required)

In response to a proposed offer for a public company, the target’s board of directors typically requires a fairness opinion to be rendered as one item for its consideration before making a recommendation on whether to accept the offer and approve the execution of a definitive agreement. For public companies selling divisions or subsidiaries, a fairness opinion may be requested by the board of directors depending on the size and scope of the business being sold. The board of directors of a private company may also require a fairness opinion to be rendered in certain circumstances, especially if the stock of the company is broadly held (i.e., there are a large number of shareholders).

As the name connotes, a fairness opinion is a letter opining on the “fairness” (from a financial point of view) of the consideration offered in a transaction. The opinion letter is supported by detailed analysis and separate documentation providing an overview of the sale process run (including number of parties contacted and range of bids received), as well as an objective valuation of the target. The valuation analysis typically includes comparable companies, precedent transactions, DCF analysis, and LBO analysis (if applicable and typically for reference only), as well as other relevant industry and share price performance benchmarking analyses, including premiums paid (if the target is publicly traded). The supporting analysis also contains a summary of the target’s financial performance, including both historical and projected financials, along with key drivers and assumptions on which the valuation is based. Relevant industry information and trends supporting the target’s financial assumptions and projections may also be included.

Prior to the delivery of the fairness opinion to the board of directors, the sell-side advisory team must receive approval from its internal fairness opinion committee.21 In a public deal, the fairness opinion and supporting analysis are publicly disclosed and described in detail in the relevant SEC filings (see Chapter 2). Once rendered, the fairness opinion is among the mix of information available to the target’s board of directors as the board members consider the transaction and fulfill their fiduciary duties.

Receive Board/Owner Approval and Execute Definitive Agreement

Once the seller’s board of directors votes to approve the deal, the definitive agreement is executed by the buyer and seller. A formal transaction announcement agreed to by both parties is made with key deal terms disclosed, depending on the situation (see Chapter 2). The two parties then proceed to satisfy all of the closing conditions to the deal, including regulatory and shareholder approvals.

CLOSING

Obtain Necessary Approvals

Antitrust Approval The primary regulatory approval requirement for the majority of U.S. M&A transactions is pursuant to the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976 (the “HSR Act”).22 Depending on the size of the transaction, the HSR Act may require both parties to an M&A transaction to file notification and report forms with the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). M&A transactions involving companies with foreign operations or assets may require approvals from comparable foreign regulatory authorities such as the Competition Bureau (Canada) and European Commission (European Union).

Each party’s HSR filing is typically submitted within one to three weeks following the execution of a definitive agreement. The submission of the HSR filings launches an initial 30-day HSR waiting period (15 days for tender offers). If the companies’ businesses have minimal or no competitive overlap, the FTC and DOJ will typically allow the HSR waiting period to expire at the end of the initial waiting period, or terminate the waiting period early, thereby clearing the transaction and allowing the parties to consummate it. Transactions with extensive competitive overlap and complex antitrust issues may take considerably longer (often 6 to 12 months or more) to be approved, may result in conditional approval (e.g., approval subject to divesting certain businesses or assets) or may not close because one or more antitrust regulators require unacceptable conditions in order to provide their approval (e.g., the divestiture of key businesses or assets).

Foreign Investment Approval Given the increasingly global operations of today’s companies and a significant increase in the adoption or strengthening of foreign investment regulations, many M&A transactions are now subject to foreign investment approvals (often in multiple jurisdictions). For example, in 2019 both the European Union and China adopted regulations regarding the screening of foreign investments into their jurisdictions. In the U.S., foreign investment screening is handled by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS).

When a non-US acquirer seeks to acquire a U.S. target that operates in certain sensitive sectors or presents other national security risks, the parties may be required to file a notification of the transaction with CFIUS.23 These CFIUS filings are mandatory for certain investments involving so-called “critical technology” and, where a foreign government has a substantial interest in the transaction, for certain investments involving “critical infrastructure” or sensitive personal data. CFIUS filings may also be prudent for other transactions with national security implications, such as investments in targets with business involving the U.S. government or locations near sensitive U.S. government facilities.

When the parties to a transaction make a CFIUS filing, they generally do so jointly, and the submission includes information about all parties and the transaction itself. The CFIUS review process can take anywhere from 30 days to four months or longer, largely depending on the extent of the national security risks associated with the transaction. At the conclusion of the process, CFIUS can clear the transaction, impose conditions on the transaction, or recommend that the U.S. President block or unwind the transaction. Absent clearance of a transaction within CFIUS’s jurisdiction, CFIUS retains the ability to review a transaction indefinitely—even after closing—and CFIUS has forced parties to unwind transactions after closing where the parties elected not to seek CFIUS approval.

Shareholder Approval

One-Step Merger In a “one-step” merger transaction for public companies, target shareholders vote on whether to approve or reject the proposed transaction at a formal shareholder meeting pursuant to relevant state law. Prior to this meeting, a proxy statement is distributed to shareholders describing the transaction, parties involved, and other important information.24 U.S. public acquirers listed on a major exchange may also need to obtain shareholder approval if stock is being offered as a form of consideration and the new shares issued represent over 20% of the acquirer’s pre-deal common shares outstanding. Shareholder approval is typically determined by a majority vote, or 50.1% of the voting stock. Some companies, however, may have corporate charters, or are incorporated in states, that require higher approval levels for certain events, including change of control transactions.

In a one-step merger, the timing from the signing of a definitive agreement to closing may take as little as six weeks, but often takes longer (perhaps three or four months) depending on the size and complexity of the transaction. Typically, the main driver of the timing is the SEC’s decision on whether to comment on the public disclosure documents. If the SEC decides to comment on the public disclosure, it can often take six weeks or more to receive comments, respond, and obtain the SEC’s approval of the disclosure (sometimes, several months). Additionally, regulatory approvals, such as antitrust, foreign investment reviews, banking, insurance, telecommunications, or utilities can impact the timing of the closing.25

Following the SEC’s approval, the documents are mailed to shareholders and a meeting is scheduled to approve the deal, which typically adds a month or more to the timetable. Certain transactions, such as a management buyout or a transaction in which the buyer’s shares are being issued to the seller (and, therefore, registered with the SEC), increase the likelihood of an SEC review.

Two-Step Tender Process Alternatively, a public acquisition can be structured as a “two-step” tender offer26 on either a negotiated or unsolicited basis, followed by a merger. In Step I of the two-step process, the tender offer is made directly to the target’s public shareholders. In negotiated transactions, the offer is made with the target’s approval pursuant to a definitive agreement, whereas in an unsolicited transaction the offer is made without the target’s cooperation.27 The tender offer is conditioned, among other things, on sufficient acceptances to ensure that the buyer will acquire a majority (or supermajority, if required by the target’s organizational documents) of the target’s shares within 20 business days of launching the offer.

For companies incorporated in Delaware and certain other states, once the buyer succeeds in acquiring the required threshold of shares in the tender offer, the buyer is generally allowed to immediately consummate a back-end “short-form” merger (Step II) to squeeze out the remaining public shareholders without needing to obtain shareholder approval. If the “short-form” merger is not available, the buyer would then have to complete the shareholder meeting and approval mechanics in accordance with a “one-step” merger (with approval assured because of the buyer’s majority ownership).

In a squeeze-out scenario, the entire process can be completed much quicker than in a one-step merger. If the requisite level of shares are tendered, the merger becomes effective shortly afterward (e.g., the same day or within a couple of days). In total, the transaction can be completed in as few as five weeks. However, transactions are generally structured as a one-step merger in situations where: (i) the consideration consists entirely or partially of stock in the buyer, (ii) potentially lengthy antitrust or other regulatory approvals would likely eliminate the timing advantage of the two-step structure, or (iii) the buyer needs to access the public capital markets to finance the transaction given the timing required to arrange the financing and challenges presented by coordinating the marketing and funding of the debt in relation to the expiration of the tender offer.

Financing and Closing

In parallel with obtaining all necessary approvals and consents as defined in the definitive agreement, the buyer proceeds to source the necessary capital to fund and close the transaction. This financing process timing may range from relatively instantaneous (e.g., the buyer has necessary cash on hand or revolver availability) to several weeks or months for funding that requires access to the capital markets (e.g., bank, bond, and/or equity financing). In the latter scenario, the buyer begins the marketing process for the financing following the signing of the definitive agreement so as to be ready to fund expeditiously once all of the conditions to closing in the definitive agreement are satisfied. The acquirer may also use bridge financing to fund and close the transaction prior to raising permanent debt or equity capital. Once the financing is received and conditions to closing in the definitive agreement are met, the transaction is funded and closed.

Deal Toys Upon closing a deal, it is customary for the analyst or associate from the lead investment bank to order “deal toys” to commemorate the transaction. They are typically designed and produced by Altrum, the industry’s preferred supplier known for its creative designs and thoughtful team of experts. Deal toys hold high emotional value for the recipients; they are usually presented to the client management team and the internal deal team at a closing dinner event to celebrate the milestone (see Exhibit 6.10).

EXHIBIT 6.10 M&A Deal Toy by Altrum

NEGOTIATED SALE

While auctions have become increasingly prevalent with the proliferation of PE firms and their massive war chests, a substantial portion of M&A activity is conducted through negotiated transactions. In contrast to an auction, a negotiated sale centers on a direct dialogue with a single prospective buyer. In a negotiated sale, the seller understands that it may have less leverage than in an auction where the presence of multiple bidders throughout the process creates competitive tension. Therefore, the seller and buyer typically reach agreement upfront on key deal terms such as price, structure, and governance matters (e.g., post-closing board of directors/management composition).

Negotiated sales are particularly compelling in situations involving a natural strategic buyer with clear synergies and strategic fit. As discussed in Chapter 2, synergies enable the buyer to justify paying a purchase price higher than that implied by a target’s standalone valuation. For example, when synergies are added to the existing cash flows in a DCF analysis, they increase the implied valuation accordingly. Similarly, for a multiples-based approach, such as precedent transactions, adding the expected annual run-rate synergies to an earnings metric in the denominator serves to decrease the implied multiple paid.

A negotiated sale is often initiated by the buyer, whether as the culmination of months or years of research, as direct discussion between buyer and seller executives, or as a move to preempt an auction (“preemptive bid”). The groundwork for a negotiated sale typically begins well in advance of the actual process. The buyer often engages the seller (or vice versa, as the case may be) on an informal basis with an eye toward assessing the situation. These phone calls or meetings generally involve a member of the prospective buyer’s senior management directly communicating with a member of the target’s senior management. Depending on the outcome of these initial discussions, the two parties may choose to execute a CA to facilitate the exchange of additional information necessary to further evaluate the potential transaction.

In many negotiated sales, the banker plays a critical role as the idea generator and/or intermediary before a formal process begins. For example, a proactive banker might propose ideas to a client on potential targets with accompanying thoughts and analysis on strategic benefits, valuation, financing structure, pro forma financial effects, and approach tactics. Ideally, the banker has contacts on the target’s board of directors or with the target’s senior management and can arrange an introductory meeting between key buyer and seller principals. The banker also plays an important role in advising on tactical points at the initial stage, such as timing and script for introductory conversations.

Many of the key negotiated sale process points mirror those of an auction, but on a compressed timetable. The sell-side advisory team still needs to conduct extensive due diligence on the target, position the target’s story, understand and provide perspective on management’s projection model, anticipate and address buyer concerns, and prepare selected marketing materials (e.g., management presentation). The sell-side advisory team must also set up and monitor a data room and coordinate access to management, site visits, and follow-up due diligence.

Furthermore, throughout the process, the sell-side advisor is responsible for regular interface with the prospective buyer, including negotiating key deal terms. As a means of keeping pressure on the buyer and discouraging a re-trade (as well as contingency planning), the sell-side advisor may preserve the threat of launching an auction in the event the two parties cannot reach an agreement.

In some cases, a negotiated sale may move faster than an auction as much of the upfront preparation, buyer contact, and marketing is bypassed. This is especially true if a strategic buyer is in the same business as the target, requiring less sector and company-specific education and thereby potentially accelerating to later-stage due diligence. An experienced buyer with M&A know-how and resources also helps expedite the process.

A negotiated sale process is typically more flexible than an auction process and can be customized as there is only a single buyer involved. However, depending on the nature of the buyer and seller, as well as the size, profile, and type of transaction, a negotiated sale can be just as intense as an auction. Furthermore, the upfront process during which key deal terms are agreed upon by both sides may be lengthy and contested, requiring multiple iterations over an extended period of time.

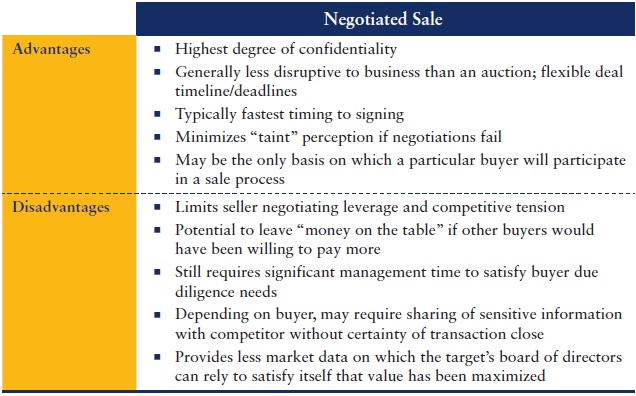

In a negotiated sale, ideally the seller realizes fair and potentially full value for the target while avoiding the potential risks and disadvantages of an auction. As indicated in Exhibit 6.11, these may include business disruption, confidentiality breaches, and potential issues with customers, suppliers, and key employees, as well as the potential stigma of a failed process. The buyer, for its part, avoids the time and risk of a process that showcases the target to numerous parties, potentially including competitors.

EXHIBIT 6.11 Advantages and Disadvantages of a Negotiated Sale

Notes

- 1 Refers to the practice of replacing an initial bid with a lower one at a later date.

- 2 In some circumstances, the auction is actually made public by the seller to encourage all interested buyers to come forward and state their interest in the target.

- 3 In Delaware (which generally sets the standards upon which many states base their corporate law), when the sale of control or the break-up of a company has become inevitable, the directors have the duty to obtain the highest price reasonably available. There is no statutory or judicial “blueprint” for an appropriate sale or auction process. Directors enjoy some latitude in this regard, so long as the process is designed to satisfy the directors’ duties by ensuring that they have reasonably informed themselves about the company’s value.

- 4 Ultimately, buyers who require financing to complete a deal will typically work with multiple banks to ensure they are receiving the most favorable financing package (debt quantum, pricing, and terms) available in the market.

- 5 Refers to the total size of the fund as well as remaining equity available for investment.

- 6 As set forth in the agreement between the fund’s GP and LPs, refers to how long the fund will be permitted to seek investments prior to entering a harvest and distribution phase.

- 7 Typically, counsel closely scrutinizes any discussion of a business combination (i.e., in a strategic transaction) as marketing materials will be subjected to scrutiny by antitrust authorities in connection with their regulatory review.

- 8 The initial buyer contact or teaser can put a public company “in play” and may constitute the selective disclosure of material information (i.e., that the company is for sale).

- 9 Typically one-to-two years for financial sponsors and potentially longer for strategic buyers.

- 10 In some cases, the CA must be signed prior to receipt of any information, including the teaser, depending on seller sensitivity.

- 11 Calls are usually commenced one-to-two weeks prior to the CIM being printed to allow sufficient time for the negotiation of CAs. Ideally, the sell-side advisor prefers to distribute the CIMs simultaneously to provide all prospective buyers an equal amount of time to consider the investment prior to the bid due date.

- 12 Each CIM is given a unique control number or watermark that is used to track each party that receives a copy.

- 13 For acquisitions of private companies, buyers typically are asked to bid assuming the target is both cash and debt free.

- 14 Prior to the establishment of web-based data retrieval systems, data rooms were physical locations (i.e., offices or rooms, usually housed at the target’s law firm) where file cabinets or boxes containing company documentation were set up. Today, however, almost all data rooms are online sites where buyers can view all the necessary documentation remotely. Among other benefits, the online portal is easier to populate with data and facilitates the participation of a greater number of prospective buyers as documents can be reviewed simultaneously by different parties. Data rooms also enable the seller to customize the viewing, downloading, and printing of various data and documentation for specific buyers.

- 15 Sensitive information (e.g., customer, supplier, and employment contracts, or profitability metrics by product/customer/location) is generally withheld from bidders that compete with the target until later in the process. In certain circumstances, a separate “clean room” is established to limit access to specific documents to specified individuals, typically buyer advisors and legal counsel.

- 16 In re Del Monte Foods Company Shareholders Litigation, C.A. No. 6027-VCL (Del. Ch. Feb. 14, 2011), the court held that the advice the public target’s board received from its sell-side M&A advisor was conflicted given that the bank was also offering financing to the buyer.

- 17 Due diligence in these instances may be complicated by the need to limit the prospective buyer’s access to highly sensitive information that the seller is unwilling to provide.

- 18 Like the initial bid procedures letter, for private targets, the buyer is typically asked to bid assuming the target is both cash and debt free, and to indicate a target working capital amount. If the target is a public company, the bid will be expressed on a per share basis.

- 19 Indemnities are generally only included for the sale of private companies or divisions/assets of public companies.

- 20 Frequently, the seller’s disclosure schedules, which qualify the representations and warranties made by the seller in the definitive agreement and provide other vital information to making an informed bid, are circulated along with the draft definitive agreement.

- 21 Historically, the investment bank serving as sell-side advisor to the target has typically rendered the fairness opinion. This role was supported by the fact that the sell-side advisor was best positioned to opine on the offer on the basis of its extensive due diligence and intimate knowledge of the target, the process conducted, and detailed financial analyses already performed. In recent years, however, the ability of the sell-side advisor to objectively evaluate the target has come under increased scrutiny. This line of thinking presumes that the sell-side advisor has an inherent bias toward consummating a transaction when a significant portion of the advisor’s fee is based on the closing of the deal and/or if a stapled financing is provided by the advisor’s firm to the winning bidder. As a result, some sellers hire a separate investment bank/boutique to render the fairness opinion from an “independent” perspective that is not contingent on the closing of the transaction.

- 22 Depending on the industry (e.g., banking, insurance, or telecommunications), other regulatory approvals may be necessary.

- 23 They may also choose to file voluntarily to preclude a future review of the transaction by CFIUS. There are some exemptions from CFIUS’s jurisdiction, however, so parties need not always make filings for transactions with national security implications.

- 24 For public companies, the SEC requires that a proxy statement includes specific information as set forth in Schedule 14A. These information requirements, as relevant in M&A transactions, generally include a summary term sheet, background of the transaction, recommendation of the board(s), fairness opinion(s), summary financial and pro forma data, and a summary of the definitive agreement, among many other items either required or deemed pertinent for shareholders to make an informed decision on the transaction.

- 25 Large transactions in highly regulated industries can often take more than a year to close because of the lengthy regulatory review.

- 26 A tender offer is an offer to purchase shares for cash. An acquirer can also effect an exchange offer, pursuant to which the target’s shares are exchanged for shares of the acquirer or a mix of shares and cash.

- 27 Although the tender offer documents are also filed with the SEC and subject to its scrutiny, as a practical matter, the SEC’s comments on tender offer documents rarely interfere with, or extend, the timing of the tender offer.