Rituals and Meditations

Ross Nichols, the most significant Druid teacher and writer of the twentieth century, defined ritual memorably in a single crisp phrase: “Ritual is poetry in the world of acts.” 48 Just as a well-crafted poem uses the tools of language to help the reader experience something of the mood or experience that inspired it, a well-crafted magical ritual uses a much broader set of tools—words, gestures, physical props, and mental imagery—to help the ritualist enter into different states of consciousness and come into contact with the powers and insights each of these states of consciousness has to offer.

Put another way, magical ritual is, among other things, a performing art. Like every other performing art, it takes a certain amount of practice to be able to do it well, and the more work you put into preparation and practice, the better the results will be. Unlike most performing arts, it’s not done for spectators. In the rituals given in this book, you are the audience as well as the performer. That has certain advantages—among other things, you’re guaranteed the best seat in the house!—but it also places certain requirements on you as performer as well as audience. To do it well, to accomplish the work of self-initiation that the rituals of Merlin’s Wheel are meant to accomplish, it’s important to understand what you’re doing, and to practice it often enough that you don’t have to fumble with half-familiar words and actions while you’re doing it.

That’s a little easier than it might otherwise be, because the ceremonies of Merlin’s Wheel are assembled from a set of shorter rituals and practices, each of which has a specific magical function in the larger structure. (This sort of modular structure is standard in modern traditions of ceremonial magic.) Each of those shorter pieces can be learned and practiced by itself and then brought into the larger ritual at the appropriate point. What’s more, the shorter ceremonies and practices that make up the mystery rituals of Merlin’s Wheel have many other magical uses, so the work you’ll need to put into learning and rehearsing them will pay off many times over as you pursue your own magical path.

As we discussed in Chapter Three, each of the eight rituals can be performed at three different levels: the Ovate Circle or beginning level, the Bardic Circle or intermediate level, and the Druid Circle or advanced level. The same principle of building larger structures from smaller parts applies here as well. The ceremony you learn and perform at the Ovate level isn’t discarded when you pass to the Bardic level; instead, new elements are added to the existing structure. The same thing happens as you transition to the Druid level. When you start performing the rituals on the Bardic level, in other words, the year of experience you’ve put into the Ovate rituals will carry over into the framework of the Bardic rituals, and by the time you get to the rituals of the Druid level, you’ll already have two years of experience with some parts of the ceremony, and one year with other parts.

The Ovate Workings

These are the simplest versions of the eight rituals of Merlin’s Wheel and can be performed by anyone, even a complete beginner, who is willing to learn the very basic ritual practices used at this level. Each of the Ovate rituals includes the following steps:

1. Perform the opening ritual.

2. Invoke the energies of the season with the Octagram and an invocation.

3. Read aloud the symbolic narrative of the season.

4. Meditate on the narrative and the energies of the season.

5. Release the energies of the season with the Octagram and words of thanks.

6. Perform the closing ritual.

The opening and closing rituals are also assembled from parts, and those parts are best learned one at a time, beginning with the most basic ritual action you’ll need to know, the Rite of the Rays.

The Rite of the Rays

This is an opening and closing gesture, the simplest of the ritual methods taught in the system of magic used in this book. It combines gesture, voice, and imagination in a single magical act. Its purpose is to orient the self toward the divine, symbolized by the Three Rays of Light— / | \ —the Druidical symbol of creation.

The words used in the Rite of the Rays are in the Welsh language, and mean in English “Alawn, Plennydd, and Gwron, the Three Rays of Light.” The three names Alawn, Plennydd, and Gwron mean “harmony,” “light,” and “virtue,” and according to tradition, they were the names of the three original bards of the island of Britain. They also have a deeper meaning, which will be discussed a little later in this chapter.

The final word in the ritual is “Awen,” which is one of the great sacred words of Druidry, filling much the same role in Druid Revival symbolism and spirituality that the famous word Om (Aum) has in Hindu and Buddhist mysticism, or the various names of God have in traditions descended from one of the monotheistic religions. Awen is the spirit of inspiration, the spiritual presence inside every being that gives insight into the depths of being. In ritual it is always pronounced as though divided into three syllables, “AH-OO-EN,” with each syllable drawn out and held for the same length of time as the others.

None of these words are simply spoken, though; in the jargon of the operative mage, they are vibrated. This is a particular mode of speaking or chanting names, words, and phrases of power. To vibrate a word is to utter it in such a way that it produces a buzzing or tingling sensation in your body. To learn how to do this, take a vowel sound such as “ah” and draw it out, changing the way your mouth and throat shape the sound until you feel the sensation just described. Once you can do this reliably, you can proceed to learn the Rite of the Rays, which is done as follows.

First, stand straight, feet together, arms at sides, facing east. Pause, clear your mind, then visualize yourself expanding upward and outward, through the air and through space, until your body is so large that your feet rest on the earth as though on a ball a foot across; the sun is at your solar plexus, and your head is amongst the stars. Then raise your hands up from your sides in an arc above your head. Join them palm to palm, fingers and thumbs together and pointing upward. Then draw them down until your thumbs touch the center of your forehead. As you do this, visualize a ray of light descending from infinite space above you to form a star of brilliant white light above the top of your head. Vibrate the word MAE (pronounced “MY”).

Second, draw down your joined hands to the level of your heart, and visualize a ray of light shining from the blazing star above your head down the midline of your body, and descending into infinite space directly below you. Vibrate the word ALAWN (pronounced “ALL-own,” the last syllable rhyming with “crown”).

Third, leaving your left hand at heart level, move your right hand down and to your right in an arc until it forms a diagonal line from shoulder to fingertips. The palm should finish facing forward. As you do this, visualize a ray of light shining from the star of light above your head along the line of your right arm, and descending into infinite space below and to your right. Vibrate the word PLENNYDD (pronounced “PLEN-nuth,” with the “th” voiced as in “these,” rather than unvoiced as in “thin”).

Fourth, make an identical motion with your left hand, extending it down and to your left until it too forms a diagonal line from shoulder to fingertips. As you do this, visualize a ray of light shining from the star of light above your head along the line of your left arm, and descending into infinite space below and to your left. Vibrate the words A GWRON (pronounced “ah GOO-ron”).

Fifth, cross your arms across your chest, right arm over left, with your fingertips resting on the front part of your shoulders. Visualize all three rays of light and vibrate the words Y TEYR PELYDRYN GOLEUNI (pronounced “ee TEIR pell-UD-run go-LEY-nee”). Then, in a single smooth motion, raise your elbows upward and sweep both arms up, out, and down to your sides, then bring them palm to palm at groin level and raise them to the center of your chest, turning the fingers upward and bringing the thumbs to touch your chest. Vibrate the word AWEN (pronounced “AH-OO-EN,” with each of the three syllables held for an equal length of time). This completes the ritual.

Practice the Rite of the Rays daily for at least a week before going on to learn the Lesser Ritual of the Pentagram. Simple though it is, the Rite is not a mere formality. It contains a wealth of magical potential that can be understood only through practice, and time spent mastering it will not be wasted.

The Lesser Ritual of the Pentagram

This is one of the workhorse rituals of the system of magic used in this book, a basic magical practice with many applications. It is done in two forms, summoning and banishing. The summoning form clears a space of unwanted and unbalanced forces, and calls in the powers of the four elements in a balanced way. The banishing form clears the space again and returns the powers of the elements to their normal condition.

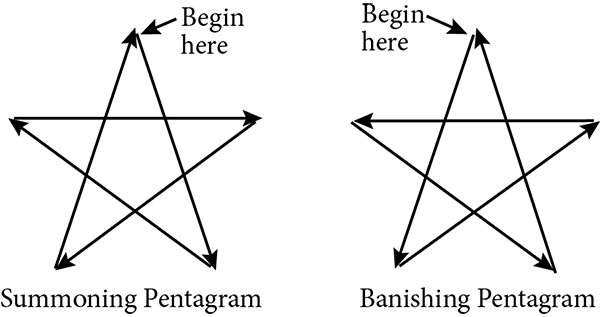

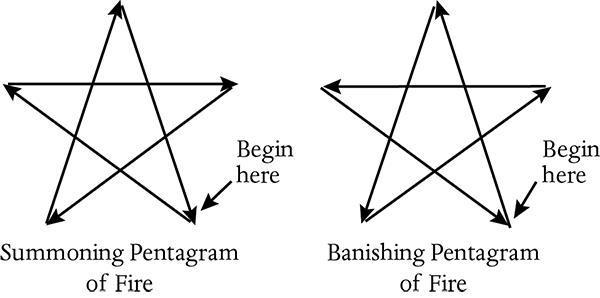

The difference between the two forms is purely a matter of how the pentagrams are traced: in the summoning ritual the pentagram is traced clockwise from the uppermost point, while in the banishing ritual it is traced counterclockwise from the same point. The summoning ritual is done at the beginning of a ceremony, the banishing ritual at the end.

This differs from the way that pentagrams are traced in the Lesser Ritual of the Pentagram as it’s usually practiced, and this is quite deliberate. The standard way of tracing pentagrams in modern magical practice comes from the traditions of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and is rooted in Judeo-Christian symbolism. Thus the basic all-purpose banishing in Golden Dawn practice, and the traditions that descend from it, uses a pentagram traced from the point of earth to the point of spirit, the same gesture used to banish the element of earth. Why? Because an enduring theme of Christian teaching is the rejection of everything earthly as evil.

That attitude isn’t to be found in Celtic Pagan traditions of the sort that underlie the rituals of Merlin’s Wheel, nor is it present in the traditions of the Druid Revival that have shaped the magic used in this book. Instead, these see the world of matter as a place of learning and delight—not a trap from which the soul must struggle free. Thus the method for tracing the pentagrams used here does not treat the earth as something to be banished! Instead, it draws on Druid teachings about the creation and dissolution of the world at the beginning and end of the great cycles of time.

To summon the subtle energies of magic at the beginning of a rite, we bring energy down from spirit in a clockwise pattern, passing through the points of the pentagram assigned to fire, air, water, and earth in that order, and returning to spirit: the order in which nwyfre,49 the life force, descended through the elemental planes in the creation of the world, according to Druid philosophy. To banish, in turn, we trace the pentagram counterclockwise from the point of spirit, through the points of earth, water, air, and fire in that order, and returning to spirit: the order in which nwyfre will ascend through the elemental planes at the dissolution of the world.

Figure 4–1: Summoning and Banishing Pentagrams

With these changes kept in mind, the Lesser Summoning Ritual of the Pentagram is performed as follows:

First, standing in the center of the space in which you are working, face east and perform the complete Rite of the Rays.

Second, go to the eastern quarter of the space. Using the index and middle fingers of your right hand, with the others folded under your thumb in the palm of your hand, trace a pentagram in the air in front of you in the first fashion shown in figure 4–1, starting down and to the right from the topmost point and then continuing clockwise around to the same point. The pentagram should be upright, two or three feet across, with the center around the level of your shoulder. As you trace the line, visualize the pentagram taking shape before you, as though your fingers were drawing it in a line of golden light. When you have finished, point to the center and vibrate the divine name HEU’C (pronounced “HEY’k”).

Third, with your extended fingers, trace a line around the circumference of the space a quarter circle to your right, ending at the southern quarter. Visualize the line in golden light as you trace it. Trace a pentagram in the south in the same way as you did in the east, point to the center, and vibrate the divine name SULW (pronounced “SILL-w”).

Fourth, repeat the process, tracing a line another quarter of the way around the circle to the west, visualizing it in golden light, and trace and visualize the pentagram as you did in the east and south. Point to the center of the pentagram and vibrate the divine name ESUS (pronounced “ESS-iss”).

Fifth, repeat the process once more, tracing a line around to the north, tracing and visualizing a pentagram there, and vibrating the divine name ELEN (pronounced “ELL-enn”).

Sixth, trace a line as before back around to the east, completing the circle, then return to the center and face east. Extend your arms down and out to your sides, once again taking on the posture of the Three Rays of Light. Say: “Before me the Hawk of May and the powers of air. Behind me the Salmon of Wisdom and the powers of water. To my right hand, the White Stag and the powers of fire. To my left hand, the Great Bear and the powers of earth. For about me stand the pentagrams, and upon me shine the Three Rays of Light.”

As you name each of these things, visualize it as solidly and intensely as you can. You are surrounded by the elements—a springtime cloudscape to the east, a summer scene of blazing heat to the south, an autumn seascape to the west, and a forest in winter to the north—with the animal guardians visible against these backgrounds. The pentagrams and circle form a pattern like a crown surrounding you, and the Three Rays of Light shine down from the starry center of light above your head as in the Rite of the Rays.

Seventh, perform the complete Rite of the Rays as before. This completes the ritual.

The Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram is performed exactly the same way as the Summoning version, except that the pentagram is drawn the other direction, counterclockwise from the topmost point, as shown in Figure 4-1.

Both these rituals should be practiced regularly so that you can do them without having to follow a script. It takes around five minutes to do each of them, so a very modest investment of practice time will be enough to learn them. The payoff from that investment, in terms of the effects you will get from the practice of the seasonal rituals, will be well worth the time spent.

Opening and Closing a Temple

The Lesser Ritual of the Pentagram is the most important step in preparing a space for the ceremonies of the mysteries of Merlin’s Wheel, but it doesn’t stand alone. In most systems of modern ceremonial magic, including the one used in this book, a more extensive ritual that includes the Pentagram Ritual is used to open a temple of the mysteries before the ceremony begins. Another similar ritual is used to close the temple once the ceremony is finished.

In ancient times, of course, the temples of the mysteries were exactly that: sacred buildings, as large and splendid as the local community could support, which were only used for ceremonial purposes. In the waning years of the ancient world, as religious intolerance made the public celebration of the Mysteries impossible, those who preserved the traditions downsized their facilities to match their resources, and people took to celebrating the mysteries in their own homes. The habit of celebrating the rituals of alternative religious traditions in living rooms goes back a surprisingly long way, and that is the custom we’ll be following here.

The temple you will be establishing for the eight seasonal rituals, in other words, will be a convenient room indoors or a private outdoor space, which can be used for ordinary purposes on every other day of the year. The requirements are simple: a place for an altar in the center of the space, a place for a chair in the west, ample room to walk around on all sides, and privacy.

|

Date |

Festival |

Color |

|

December 21 |

Alban Arthan |

Brown |

|

February 2 |

Calan Myri |

Violet |

|

March 21 |

Alban Eilir |

Orange |

|

May 1 |

Calan Mai |

Green |

|

June 21 |

Alban Hefin |

Gold |

|

August 1 |

Calan Gwyngalaf |

Red |

|

September 22 |

Alban Elfed |

Blue |

|

November 1 |

Calan Tachwedd |

Black |

Table 4–1: Colors of the Festivals

The altar can be any convenient flat-topped surface large enough to hold two bowls and three candlesticks. For best results it should rise to somewhere between your knees and your waist. The altar is covered by an altar cloth, which may be a plain unhemmed length of fabric, or something as elaborate and beautiful as your budget or your sewing skills permit. You may use a plain white altar cloth, which is standard in Druidical practice, or an altar cloth of a different color for each of the eight celebrations, as shown in Table 4-1.

On the altar go three white candles in candlesticks, a bowl or small cauldron of clean water, and a bowl or small cauldron of sand, which is used for burning incense. You may use any kind of incense you prefer. If you’re using stick incense, simply thrust the end of the stick into the sand, while if you’re using cone incense or loose incense on charcoal, the cone or charcoal can be set on the sand.

As with the altar cloth, the candlesticks and the bowls or cauldrons can be as simple or as elaborate as you wish and can afford. They are placed on the altar as shown in Figure 4-2; the cauldron or bowl on your left, as you stand at the west of the altar facing east, is for water, and the one on your right is for incense.

74 Figure 4–2: Arrangement of the Altar

Figure 4–2: Arrangement of the Altar

You can also decorate the altar according to the season—for example, if you live in the northern temperate zone, you might choose holly or fir boughs in the winter, flowers in the spring, greenery in the summer, and ripe fruit or ears of grain in the autumn. If your local seasonal cycle has a different pattern, follow that pattern and choose your altar decorations accordingly. The point of the seasonal decor is not to follow a rigid symbolic scheme, but to help you link the legendary cycle of the life of Merlin in your imagination with the cycle of the year, and with the subtle cycles of your own consciousness and its awakening into greater light and life.

Finally, put a chair on the western side of the space, facing the altar. Once you have set up the space, put clean water in the water bowl or cauldron, light the incense, then sit in the chair facing the altar for a few moments to calm your mind and clear every other concern from your thoughts. All your attention should be on the ritual you are about to perform. When you are ready, stand up, go to the west side of the altar, and begin.

The opening ritual is performed as follows:

First, stand on the west side of the altar, facing east. Raise your right hand, palm facing toward the east, and say: “In the presence of the holy powers of Nature, I prepare to open this temple of the mysteries. Let peace be proclaimed with power, throughout this temple and in the hearts of all who stand herein.”

Second, perform the Lesser Summoning Ritual of the Pentagram, tracing the pentagrams clockwise from the top point. Begin and end on the west side of the altar, facing east.

Third, take up the cauldron or bowl of water in both hands and raise it high above the altar. Say: “Let this temple and all within it be purified with the waters of the sacred well.” Carry the cauldron to the eastern quarter of the space. Holding the cauldron in your right hand, dip the fingers of the left hand into the water, then flick droplets of water off your fingers three times—once down and to your right, once down and to your left, and once straight down. This pattern represents the Three Rays of Light / | \ .

Carry the cauldron around to the southern quarter and repeat the same action, sprinkling droplets of water three times in the same way. Proceed to the western quarter and then to the northern quarter, repeating the same action in each, so that the four quarters have been cleansed and purified with water in the sign of the Three Rays of Light. Return to the eastern quarter, completing the circle; raise the cauldron of water in both hands, and say: “The temple is purified.” When this is done, return to the west side of the altar, facing east, and replace the cauldron in its proper place on the left side.

Fourth, take up the cauldron or bowl of incense in both hands, and raise it high above the altar. Say: “Let this temple and all within it be consecrated with the smoke of the sacred fire.”

Next, carry the cauldron of incense to the eastern quarter of the space. Holding the cauldron in your left hand, use your right hand to wave the smoke upward from the cauldron three times—once up and to your left, once up and to your right, and once straight up. This pattern represents the Three Rays of Light in another form \ | /.

Carry the cauldron around to the southern quarter and repeat the same action, directing the incense upward three times in the same way. Proceed to the western quarter, then to the northern quarter, repeating the same action in each, so that the four quarters have been blessed and consecrated with incense in the sign of the Three Rays of Light. Return to the eastern quarter, completing the circle; raise the cauldron of incense in both hands, and say: “The temple is consecrated.” When this is done, return to the west side of the altar, facing east, and replace the cauldron in its proper place on the right side.

Fifth, circumambulate the temple. This is an ancient rite, practiced in many traditions, that involves simply walking around a sacred place or object in a clockwise direction. From where you stand west of the altar, go around the north side of the altar to the east and begin to circle the altar, keeping it always on your right side. Every time you pass the east, cross your arms upon your chest, right arm over left, and bow your head, without stopping or breaking the rhythm of your pace. Circle the altar in a clockwise direction, from east to east, three full times, then circle back around to the west side of the altar and face east.

Sixth, when the circumambulation is finished, return to the west side of the altar and face east. Say: “I invoke the rising of the Eternal Spiritual Sun! May I be illumined by its rays.”

Then imagine before you, in the east, the first brilliant flash of the rising sun. As you watch, it slowly emerges from below the horizon, great and golden, its rays flooding the temple with light and life. Visualize the rising sun until it has cleared the horizon and appears whole before you. When this is done, raise your right hand, palm forward in salutation, and say, “In the presence of the holy powers of Nature, I proclaim this temple of the mysteries duly open.” This completes the opening ritual.

At this point, if you are practicing the opening and closing ritual by themselves, go to the chair in the west, sit down, and enter into meditation for a short time. If you are performing one of the eight seasonal rituals of Merlin’s Wheel, proceed to the ritual. Either way, when you are finished, return to the west of the altar, facing east, and begin the closing ritual, which is performed as follows:

First, purify the temple again with water, exactly the way you did in the opening.

Second, consecrate the temple with fire, exactly as in the opening.

Third, starting from west of the altar facing east, circumambulate the temple in the reverse direction, going counterclockwise, with the altar always to your left side. Do this so that you pass the east three times, then return to the altar. Standing again at the west side of the altar, facing east, say: “In the name of Hu the Mighty, Great Druid God, I set free any spirits who may have been imprisoned by this ceremony. Depart unto your rightful habitations in peace, and peace be between us.”

This practice of formally releasing any spirits who may be imprisoned by a ceremony goes back centuries in Western occult practice. The traditional teaching behind this is that ritual workings produce a vortex of magical forces, and spiritual beings of various kinds can become caught in the vortex. Giving them “license to depart,” as some old magical texts describe this, is common courtesy, and it also ensures that you won’t have unwanted spiritual beings inhabiting your ritual space after the working is finished!

Fourth, perform the Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram, tracing the pentagrams counterclockwise from the uppermost point.

Fifth, standing at the west of the altar facing east, raise your right hand, palm facing the east, as you did in the opening. Say: “In the presence of the holy powers of Nature, I proclaim this temple closed.” This completes the closing ritual.

For best results, this ritual should also be practiced until you can do it from memory, but it will take you a little more time to learn this than it took to learn the other rituals that have already been presented. If you don’t have time to memorize the opening and closing ritual, take the time to rehearse it a few times, so that you don’t have to fumble with it during the actual performance of the rituals. Even a little familiarity with the ritual will improve the results of the working considerably.

The Octagram

This is one of the distinctive symbolic patterns of the system of magic used in this book. At the Druid level, a complete ritual, the Ritual of the Octagram, uses this pattern to summon and banish the influences of the Tree of Life. At the Ovate and Bardic levels, the octagram is used by itself for this purpose, along with a spoken invocation.

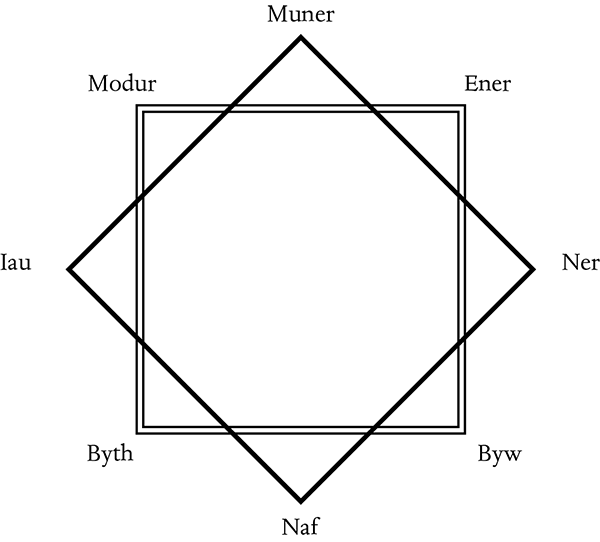

As explained in Chapter Three, the work of self-initiation calls on energies from seven of the spheres of the Tree of Life, plus an eighth point that sums up and focuses the energies of the three highest spheres. Since we work with these eight powers, the geometrical figure called the octagram—a star with eight points—allows us to symbolize those powers in visual terms, and to summon and banish them in ritual work. The Spheres of the Tree of Life are assigned to the octagram in the pattern shown below.

Figure 4–3: The Symbolic Octagram

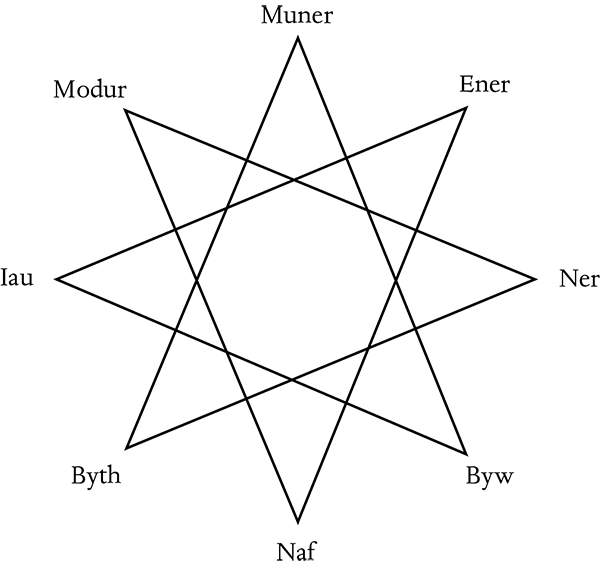

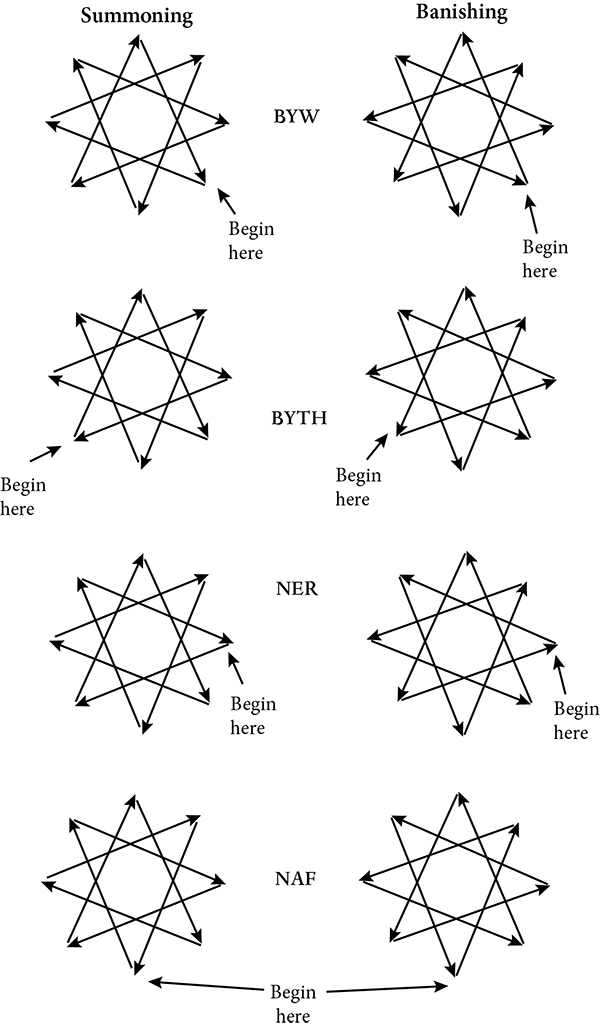

In ritual work, on the other hand, a different version of the octagram is used, so that it can be traced in a single unbroken gesture. Using this version of the octagram, just as in the pentagram ritual, we trace clockwise from any given point to summon the powers associated with that point, and counterclockwise to banish those powers.

Figure 4–4: The Ritual Octagram

Symbolic Narrative

Each of the eight ceremonies of Merlin’s Wheel has a narrative that is read aloud in the course of the ritual. If you compare these to the accounts of Merlin’s life in the legends surveyed in Chapter Two, you’ll notice that no one legend includes all the details included in the symbolic narratives used here, or does so in exactly the same order. On the other hand, it’s also true that no two of the legends of Merlin include all the details in the same order as any of the others!

The lesson to be learned here is that the legends of Merlin aren’t sacred scriptures of the sort circulated by most of the mainstream religions of our society, and shouldn’t be treated as such.50 Like the varied stories about Demeter and Persephone that gave the mysteries of Eleusis, Agrai, and Andania their core narratives, the stories about Merlin take many shapes and have given rise to a wide range of different magical traditions and ritual celebrations. Neither the accounts of Geoffrey of Monmouth, nor the varied creations of medieval minstrels, nor these rituals can claim to offer “the one true story” about Merlin. Each narrative has its own lessons to teach and its own insights to communicate.

The symbolic narrative in each ritual of Merlin’s Wheel should be read aloud, slowly and clearly, as though you were a wise elder reciting an ancient wisdom tale to a circle of young initiates. The reason it’s important to read the narrative aloud is that this takes advantage of a little-known detail of the way the human nervous system works. When you read something aloud, it gets processed by the auditory centers on the sides of the brain, not just the thinking centers in the forebrain; it affects more of your brain and thus has stronger effects on your consciousness.51 To the deeper levels of yourself, the experience of reading a narrative aloud has most of the same effects as hearing someone else read it, and this helps build the initiatory effect of the rituals.

Meditation

Many people these days think of meditation as something mysterious and exotic, but meditation has been part of magical training in the Western world since ancient times, and it plays a central role in the kind of initiatory magic taught in this book. The eight ritual workings of Merlin’s Wheel each include a period of meditation in which the archetypal images and energies of the eight stations of the wheel settle into place in your consciousness. To make the most of that experience, you’ll need to learn at least a little about meditation—and that means you’ll need to work through some preliminary exercises, then practice meditation several times, before you begin the ritual work.

You may want to consider doing more than this. The regular practice of meditation is the most basic practice in most systems of magical initiation, and for good reason. It develops skills that make every other kind of magical work easier and more powerful, and also brings the kind of self-knowledge and self-awareness that keep the initiatory process on track. Ten or fifteen minutes a day of meditation will take you further, faster, than any other practice that exists. If daily practice is more than you can handle, one or two times a week will still bring good results. On the other hand, if this isn’t the time for you to take on that form of magical training, you can still benefit from the meditation phase of each of the rituals.

For the preliminary exercises, you’ll need a place that’s quiet and not too brightly lit. It should be private—a room with a door you can shut is best, though if you can’t arrange that, a quiet corner and a little forbearance on the part of your housemates will do the job. You’ll need a chair with a straight back and a seat at a height that allows you to rest your feet flat on the floor while keeping your thighs level with the ground. You’ll also need a clock or watch placed so that you can see it easily without moving your head.

The posture for Western meditation is much simpler, and more comfortable for most people, than the more famous postures used in Asian traditions. Sit on the chair with your feet and knees together or parallel, whichever is most comfortable for you. Your back should be straight but not stiff, your hands resting on your thighs, and your head rising as though a string fastened to the crown of your skull pulled it gently upward. Your eyes may be open or closed as you prefer; if they’re open, they should look ahead of you but not focus on anything in particular. Practice the posture once or twice before starting work on the preliminary exercises.

The key to meditation is learning to enter a state of relaxed concentration. The word “relaxed” needs to be kept in mind here. Too often, what “concentration” suggests to modern people is a state of inner struggle: teeth clenched, eyes narrowed, the whole body taut with useless tension. This is the opposite of the state you need to reach. The exercises below will help you get to the state of calm and unstressed focus in which meditation happens.

Preliminary Exercise 1. Put yourself in the meditation position, then spend ten minutes or so just being aware of your physical body. Start at the soles of your feet and work your way slowly upward to the crown of your head. Take as much time as you wish. Notice any tensions you feel without trying to force yourself to relax; simply be aware of each tension. Over time this simple act of awareness will dissolve your body’s habitual tensions by making them conscious and bringing up the rigid patterns of thought and emotion that form their foundations. Like so much in meditation, though, this process has to unfold at its own speed.

While you’re doing this exercise, don’t let yourself fidget and shift, no matter how much you want to. If your body starts itching, cramping, or reacting in some other way, simply be aware of the reaction, without responding to it. These reactions often become very intrusive during the early stages of meditation practice, but bear with them. They show you that you’re getting past the levels of ordinary awareness. The discomforts you’re feeling are actually there all the time; you’ve simply learned not to notice them. Once you let yourself perceive them again, you can relax into them and let them go.

Preliminary Exercise 2. Put several sessions into the first exercise until the posture begins to feel comfortable and balanced. At this point it’s time to bring in the next ingredient of meditation, which is breathing. Start by sitting in your meditation position and going through the first exercise quickly, as a way of “checking in” with your physical body and settling into a comfortable and stable position. Then turn your attention to your breath. Draw in a deep breath and expel it slowly and steadily, until your lungs are completely empty.

When every last puff of air is out of your lungs, hold the breath out for a little while. Then breathe in through your nose, smoothly and evenly, until your lungs are full. Hold your breath in for a little while; it’s important to hold the breath in by keeping the chest and belly expanded, not by shutting your throat, which can hurt your lungs.52 Breathe out through your nose, smoothly and evenly. Each phase of the breath—breathing in, holding in, breathing out, holding out—should be approximately as long as the others, but you should let your body tell you how long to make each phase. This is called the Natural Breath, and while you’re at this stage of learning you should continue doing it for ten minutes by the clock.

While you’re breathing, your thoughts will likely try to go straying off toward some other topic. Don’t let them. Keep your attention on the rhythm of the breathing, the feeling of the air moving through your nostrils and your lungs. Whenever you notice that you’re thinking about something else, bring your attention gently back to your breathing. If your thoughts slip away again, bring them back again. This can be frustrating at first, but as with all things, it gets easier with practice.

Do the second preliminary exercise several times, until you’re comfortable with it. At this point it’s time to go on to actual meditation.

Practicing Meditation. The kind of meditation that’s central to traditional methods of magical initiation differs from the sort of thing taught in most Asian mystical traditions in that it uses the thinking mind, rather than silencing it. To do this, you need a theme—that is, an idea or image you want to understand. Sit down in the meditation posture, and spend a minute or two going through the first preliminary exercise, being aware of your body and its tensions. Then begin the fourfold breath and continue it for five minutes by the clock. During these first steps, don’t think about the theme, or for that matter, anything else. Simply be aware, first of your body and its tensions, then of your breathing, and allow your mind to become clear.

After five minutes, let your breathing become normal and turn your attention to the theme of the meditation. In each of the eight rituals, the theme will be the ritual itself, but while you’re learning to meditate you’ll need a more general theme, and the one I recommend for the purposes of this book is Merlin himself. Imagine him in one of the following eight forms—the wise infant in the arms of his mother; the child prophesying before King Vortigern; the boy standing amid the stones of Stonehenge; the young man receiving the infant Arthur from Ygerna’s servants; the grown man at Arthur’s coronation at Stonehenge; the man of middle years in the forest, beneath an apple tree; the old man at the seashore, standing beside Taliesin and Bedivere as the boat comes to carry the wounded Arthur away; or the wise elder seated outside his hermitage with his sister Ganieda, contemplating the heavens. Choose one of these, hold it in your mind, and see what ideas rise in your thoughts in response. Then choose one of these ideas and follow it out step by step, thinking about what it says to you, taking it as far as you can.

If you’re meditating on Merlin as the wise infant, for example, imagine him in his mother’s arms, looking out at the world with eyes that have far more than an infant’s awareness in them. You don’t have to visualize it, simply think about it, and pay attention to any ideas that rise in response. You might think of other mythological figures born of virgins who had unexpected knowledge from an early age—the biblical account of Jesus as a child going to the Temple and discussing scripture with the elderly scholars there, for example, has many parallels in legends from around the world. You might think of your own infancy, or of infants you have known; you might think about what infancy symbolizes, or speculate about why the wise child in mythology is always born around the winter solstice; or you might think of something else entirely. There are no wrong answers in meditation; the important thing is to pay attention to what your own mind has to teach you.

Unless you have quite a bit of experience in meditation, your thoughts will likely wander away from the theme again and again. Instead of simply bringing them back in a jump, follow them back through the chain of wandering thoughts until you reach the point where they left the theme. If you’re meditating on Merlin the wise infant, for example, and suddenly notice that you’re thinking about your grandmother instead, don’t simply go back to Merlin and start again. Work your way back. What got you thinking about your grandmother? Memories of a Thanksgiving dinner when you were a child. What called up that memory? Recalling the taste of the roasted mixed nuts she used to put out for the guests. Where did that come from? Thinking about squirrels. Why squirrels? Because you heard the scuttling noise of a squirrel running across the roof above you, and it distracted you from thinking about Merlin.

Whenever your mind strays from the theme, bring it back up the track of wandering thoughts in this same way. This approach has two advantages. First of all, it has much to teach about the way your mind works, the flow of its thoughts, and the sort of associative leaps it likes to make. Second, it develops the habit of returning to the theme, and with practice you’ll find that your thoughts will run back to the theme of your meditations just as enthusiastically as they run away from it. Time and regular practice will shorten the distance they run, until eventually your mind learns to run straight ahead along the meanings and implications of a theme without veering from it at all.

During your practice sessions, spend ten minutes meditating in this way and see what you learn about Merlin, and about yourself, in the process. As a good minimum, you may want to consider meditating eight times, once on each of the eight forms of Merlin, before your first ritual working. That should give you enough experience with the method that you can get something out of the practice even the first time you work one of the rituals of Merlin’s Wheel.

The Bardic Workings

This second stage of the rituals of Merlin’s Wheel builds on the foundations laid by the rituals of the Ovate Circle, bringing the power of creative imagination into the work. It also makes use of summonings and banishings of the four elements to heighten the magical dimension of the ritual. Each of the Bardic rituals includes the following steps:

1. Perform the opening ritual.

2. Perform one of the Elemental Summoning Rituals of the Pentagram.

3. Invoke the energies of the season with the Octagram and an invocation.

4. Perform the Composition of Place.

5. Read aloud the symbolic narrative of the season.

6. Meditate on the narrative and the energies of the season.

7. Dissolve the Composition of Place.

8. Release the energies of the season with the Octagram and words of thanks.

9. Perform one of the Elemental Banishing Rituals of the Pentagram.

10. Perform the closing ritual.

The basic framework is the same, as already mentioned, but two additional stages are added at the beginning and end of each ritual. The Elemental Rituals of the Pentagram are used to summon and banish the forces of the individual elements and will need to be learned and practiced before you use them in ritual. The Composition of Place is simply a matter of reading a description of a scene and imagining that scene as vividly as you can, and can be done by most people without advance practice. A clear understanding of the theory and purpose of both these parts of the ritual, however, will make both of them more effective when you use them.

The Elemental Rituals of the Pentagram

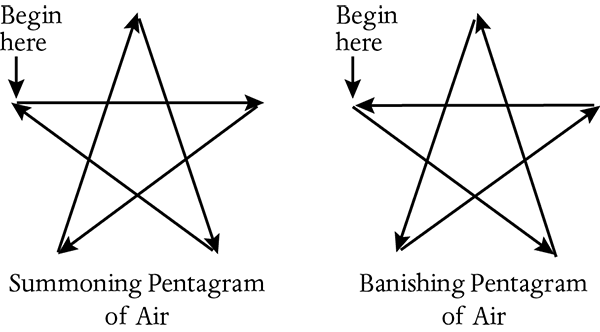

There are four Elemental Rituals of the Pentagram, one for each of the four traditional elements of earth, water, air, and fire. They follow the same structure as the Lesser Ritual, but trace the pentagrams differently, call on different divine names, and use different words when calling on the powers of the four quarters.

The Ritual of the Earth Pentagram. This is performed with one of the two pentagrams of earth, as shown below—the first to summon, and the second to banish. Begin with the Rite of the Rays, as in the Lesser Ritual, then go to the east and trace the earth pentagram. Point at the center and vibrate the divine name CERNUNNOS (pronounced “ker-NOON-os”). Proceed as in the Lesser Ritual to the other four quarters, drawing a line of light as you go, tracing the same pentagram and vibrating the same name in each. When you have completed the circle and return to the altar, say: “Before me the fertile plains, behind me the rolling hills, to my right hand the tall mountains, to my left hand the deep caverns, for about me stand the pentagrams and upon me shine the Three Rays of Light.” Then end with the Rite of the Rays as usual.

Figure 4–5: Pentagrams of Earth

The Ritual of the Water Pentagram. This is performed with one or the other of the two pentagrams of water, as shown below—the first to summon, the second to banish. Begin with the Rite of the Rays, as in the Lesser Ritual, and go to the east and trace the water pentagram. Point at the center and vibrate the divine name SIRONA (pronounced “si-ROE-na”). Proceed as in the Lesser Ritual to the other four quarters, drawing a line of light as you go, tracing the same pentagram and vibrating the same name in each. When you have completed the circle and return to the altar, say: “Before me the dancing streams, behind me the great ocean, to my right hand the strong rivers, to my left hand the quiet lakes, for about me stand the pentagrams and upon me shine the Three Rays of Light.” Then end with the Rite of the Rays as usual.

Figure 4–6: Pentagrams of Water

The Ritual of the Air Pentagram. This is performed with one or the other of the two pentagrams of air, as shown on the next page—the first to invoke, and the second to banish. Begin with the Rite of the Rays, as in the Lesser Ritual, and go to the east and trace the air pentagram. Point at the center and vibrate the divine name BELISAMA (pronounced “BEL-ih-SAH-ma”). Proceed as in the Lesser Ritual to the other four quarters, drawing a line of light as you go, tracing the same pentagram and vibrating the same name in each. When you have completed the circle and return to the altar, say: “Before me the rushing wind, behind me the silver mist, to my right hand the shining sky, to my left hand the billowing cloud, for about me stand the pentagrams and upon me shine the Three Rays of Light.” Then end with the Rite of the Rays as usual.

88

The Ritual of the Fire Pentagram. This is performed with one or the other of the two pentagrams of fire, as shown below—the first to invoke, and the second to banish. Begin with the Rite of the Rays, as in the Lesser Ritual, and go to the east and trace the fire pentagram. Point at the center and vibrate the divine name TOUTATIS (pronounced “too-TAUGHT-is”). Proceed as in the Lesser Ritual to the other four quarters, drawing a line of light as you go, tracing the same pentagram and vibrating the same name in each. When you have completed the circle and return to the altar, say: “Before me the lightning flash, behind me the fire of growth, to my right hand the radiant sun, to my left hand the flame upon the hearth, for about me stand the pentagrams and upon me shine the Three Rays of Light.” Then end with the Rite of the Rays as usual.

Figure 4–8: Pentagrams of Fire

These rituals, as already noted, need to be learned and practiced before you use them in one of the seasonal ceremonies. Having them committed to memory is best, but it’s enough at first to have done each of them several times so that you can do them with only a glance at a “cheat sheet” giving the pentagrams, names, and words.

The Composition of Place

The human imagination is one of the great tools of magic, and ceremonial magic uses it in a galaxy of ways. The practice of Composition of Place is one of these. It’s simply a matter of building up an imagined location as vividly as possible so that the symbolic qualities of that location will pervade the space in which the working takes place.

Those words, “as vividly as possible,” can be taken more strongly than they should. So many of us have been exposed to so much visual media—television, movies, video games—that many people tend to think that this sort of photographic, hyperrealistic imagery is the only kind that matters. Not many people can achieve that level of mental imagery even with extensive training, and very, very few can do anything of the kind the first time they try. If you’re not one of those few, don’t worry about it. The kind of imagery you experience in your daydreams and your memories is quite vivid enough for our purposes.

It may be helpful to remember that these images are meant to be taken symbolically, not literally. Like the symbolic narratives introduced in the Ovate Circle, they are meant to involve the deeper levels of your mind, not just the surface layers of ordinary thinking. Dragons don’t exist in our world, but they are still powerful symbols; in exactly the same way, the image of a barefoot woman in a cold winter scene (for example) may not be historically accurate but it communicates certain symbolic meanings far more precisely and powerfully than any mere rehash of historical details can do. The question to ask yourself in meditation, as you consider the images you’ve built up in the Composition of Place, is not “did this actually happen?” but “what does this mean?” As the famous British mage Dion Fortune wrote about a different set of magical pictures, “these images are not descriptive but symbolic, and are designed to train the mind, not to inform it.” 53

It’s a good idea, before you use the Composition of Place in a ritual, to read through the description at least twice and get a general sense of the image you’re going to build up. Once you’ve done that, start from the beginning of the description and imagine each detail in the order in which they’re described. Once you’ve finished, spend a few moments seeing the entire image as a whole as clearly as you can.

You’ll almost certainly find that the first time you imagine each of the images in Merlin’s Wheel, you’ll be able to perceive only a vague sketch of the image described in the ritual. Here as elsewhere, though, practice makes perfect—and something more than mere practice is involved. Each time you perform the Composition of Place with a specific image, that image becomes easier to call back to mind later because you’re literally building it on the subtle planes of being with your imaginative efforts. As you continue working with the rituals of Merlin’s Wheel, year after year, the Composition of Place will become more and more vivid and charged with emotion until it forms a powerful element of the whole rite.

As each ritual winds up, finally, you’ll be asked to dissolve the Composition of Place. This is much easier than the Composition of Place itself; you simply picture the image you’ve created dissolving and going away, so that its influence doesn’t stray from your magical work into the details of everyday life. If you think of the building up of the Composition of Place as being like fiddling with the dial of an old-fashioned radio to get the station you want, and the dissolving of the Composition of Place as giving the dial a good twist to make sure the radio won’t keep on playing that station, you’ll understand the gist of what’s going on.

The Druid Workings

These are the complete forms of the rituals of Merlin’s Wheel, and they expand on the framework already developed to provide an initiatory experience that can be repeated year after year with good results. Each of the Druid rituals includes the following steps:

1. Perform the opening ritual.

2. Perform one of the Summoning Rituals of the Octagram.

3. Perform the Composition of Place.

4. Read aloud the symbolic narrative of the season.

5. Call down the energies of the season into the communion mead, and drink it.

6. Meditate on the narrative and the energies of the season.

7. Dissolve the Composition of Place.

8. Release the energies of the season with words of thanks.

9. Perform one of the Banishing Rituals of the Octagram.

10. Perform the closing ritual.

The ceremonies of the Druid level involve two changes from the Bardic level. First, the elemental pentagram rituals are replaced by the rituals of the octagram, which call on the influences of the Tree of Life directly. Second, a communion ceremony is used to bring those influences into the physical body of the practitioner by charging a cup of mead (or honey water, for those who don’t feel it appropriate to use alcohol) with the energies of the season using ritual methods, offering some to the deity who governs that seasonal festival, and drinking the rest. The act of taking consecrated food or drink into the body of the participant was a common feature of mystery initiations in ancient times, and it plays an important part in the workings of Merlin’s Wheel once the necessary skill with ritual has been attained.

The Octagram Rituals

There are sixteen octagram rituals, one to summon and one to banish for each of the eight points of the octagram and the eight energies of the Tree of Life they command. As with the elemental pentagram rituals, the differences between one and another octagram ritual are simply which point you choose to start tracing the octagram, which direction you trace it, which color of light you visualize as you trace the line, and which divine name you vibrate while pointing to the center.

92

Figures 4–9a and 4–9b: Octagrams

93

Figures 4–9a and 4–9b: Octagrams

|

Sphere of the Tree |

Color |

|

Iau |

White |

|

Ener |

Blue |

|

Modur |

Red |

|

Muner |

Yellow |

|

Byw |

Green |

|

Byth |

Orange |

|

Ner |

Violet |

|

Naf |

Indigo |

Table 4–2: Colors for the Ritual of the Octagram

In the octagram rituals, the Rite of the Rays and the tracing of an octagram in each of the four quarters is combined with a ritual called the Invocation of Celi. In the traditions of the Druid Revival, Celi is the Hidden One, the mysterious divine source from which all things flow, who appears in certain legends as an unseen presence piping on the hills, and in certain others as the secret fire of blessing and magic. In the rite, three gestures are used to invoke the three aspects of Celi. A great deal of Druidical teaching is concealed in these three signs, and they and their titles make good themes for meditation.

The Ritual of the Octagram is performed as follows:

First, perform the Rite of the Rays, just as in the Pentagram ritual.

Second, go to the eastern quarter of the space and trace the appropriate octagram to summon or banish, beginning from the point corresponding to the Sphere whose influence you want to work with, and tracing clockwise to invoke and counterclockwise to banish. As you trace the octagram, visualize your fingers drawing a line of light in the color corresponding to the Sphere, as shown in Figure 4-2.

Third, trace a line of the same color with fingers or wand around to the southern quarter of the space and repeat the process, tracing the same octagram as before. Then do the same to the west and north, and finally return to the east, having traced the same octagram in each quarter and also traced a circle entirely around the place of working, as you do when you perform a pentagram ritual.

Fourth, return to the center and perform the Invocation of Celi. This is done with the following words and actions:

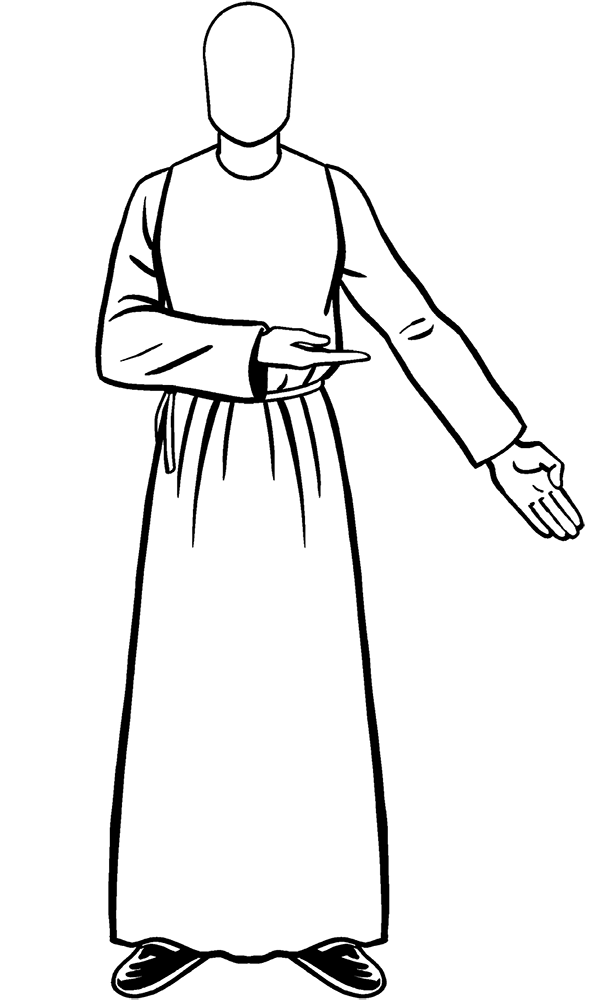

Make the Sign of the Bounty of Nature, as follows. Extend your left hand down and out to your side in a straight line, hand extended, palm facing forward. Place your right hand, palm up, at the level of your solar plexus, so that your forearm is parallel to the ground; your elbow is extended out to your side. Say aloud: “The Bounty of Nature.”

Figure 4–10: Sign of the Bounty of Nature

Make the Sign of the Cauldron of Annwn, as follows. Raise both arms to the sides, curving them to form the outline of a cauldron; the hands are a little above head level, with the fingertips pointing straight up and the palms facing each other. Say aloud: “The Cauldron of Annwn.” (This word is pronounced “ANN-oon.”)

Figure 4–11: Sign of the Cauldron of Annwn

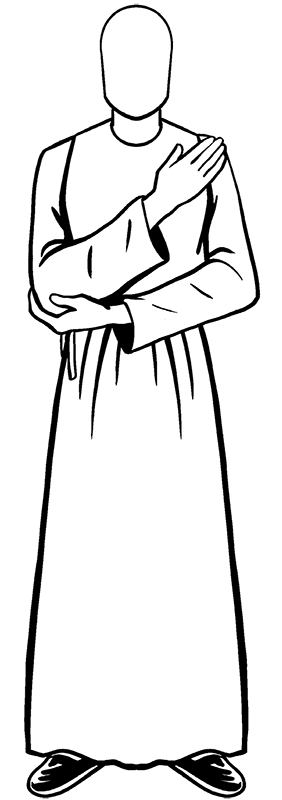

Make the Sign of the Child of Light, as follows. Bring the fingertips of your right hand to the point of your left shoulder; allow your right forearm to rest across your chest in a diagonal line so that your right elbow is at your right side; bring your left hand across so that the fingers cup the right elbow, the left forearm being parallel to the ground and the left elbow being at the left side. Say aloud: “The Child of Light.”

Figure 4–12: Sign of the Child of Light

Sweep your hands out and down, straightening your arms and holding them out from your body at an angle so that your arms and body form the sign of the Three Rays of Light. Say: “All are one in the infinite CELI.” (The name Celi is vibrated, and pronounced “KEH-lee.”)

Fifth, perform the Rite of the Rays again to finish the ritual.

Like the Pentagram Rituals, the Octagram Ritual should be practiced several times before you try to use it in a ceremony. Committing it to memory is best, but if this is difficult, it’s sufficient to become familiar enough with the ritual that you can do it smoothly with a glance at a “cheat sheet” to remind you of the right point of the octagram to begin with and the right color to use for the line you trace. The tracing of the octagram itself may require a little practice, as it’s a somewhat complex figure. Take the time you need to learn how to trace it, and the resulting ritual work will be better for it.

The Consecration of the Mead

For each of the ceremonies of the Druid Grade, you will need a cup, chalice, or horn containing mead, which is placed on the altar. A drinking horn has long been traditional for this purpose in the Druid Revival, but not everyone can obtain one of these; a ritual chalice or, if that isn’t an option for you, an ordinary wine glass will be sufficient.

Mead is available at many American liquor stores these days, and it’s also the easiest of alcoholic beverages to brew yourself.54 If you are underage, or for some other reason either should not or do not wish to use an alcoholic beverage in ritual, you can make a workable substitute by mixing a teaspoonful of honey into a cup of hot water. Stir thoroughly until the honey is dissolved, then let the mixture cool to room temperature.

You will need enough mead (or honey water) to pour out an offering, and still have as much left as you wish to drink. If you can perform the ritual outside, the mead can be poured directly on the ground. If not, you will need a wide bowl large enough to receive the offering, which can be set on the floor or on any convenient flat surface near the altar. After the ritual, the mead in the bowl should be taken outside and poured on the ground, or into running water.

The horn, chalice, or glass of mead goes onto the altar before the ritual begins, and remains there until the fifth step of the ritual. At this point you recite the invocation, calling on the deity who presides over that station of Merlin’s Wheel to be present and bless you, then perform a ritual called the Analysis of OIW.

The word OIW is a cryptogram. In the traditions of the Druid Revival, it is used in place of a certain very secret name or word of power, which is called the Secret of the Bards of the Island of Britain. This ritual discloses one part of its meaning, by way of a myth of origins found in old Welsh Druid writings. Here is one version of the story:

Einigan the Giant beheld three pillars of light, having in them all demonstrable sciences that ever were, or ever will be. And he took three rods of the quicken tree, and placed on them the forms and signs of all sciences, so as to be remembered; and exhibited them. But those who saw them misunderstood, and falsely apprehended them, and taught illusive sciences, regarding the rods as a God, whereas they only bore His Name. When Einigan saw this he was greatly annoyed, and in the intensity of his grief he broke the three rods, nor were others found that contained accurate sciences. He was so distressed on this account that from the intensity he burst asunder, and with his parting breath he prayed God that there should be accurate sciences among men in the flesh, and there should be a correct understanding for the proper discernment thereof. And at the end of a year and a day after the decease of Einigan, Menw, son of the Three Shouts, beheld three rods growing out of the mouth of Einigan, which exhibited the sciences of the Ten Letters, and the mode in which the sciences of language and speech were arranged by them, and in language and speech all distinguishable sciences. He then took the rods, and taught from them the sciences—all, except the Name of God, which he made a secret, lest the Name should be falsely discerned; and hence arose the Secret of the Bards of the Island of Britain.55

Einigan the Giant, Einigan Gawr in Welsh, is the Adam of the Druid Revival traditions, the first of all created beings. (His name is pronounced “EYE-ne-gan,” with the “g” hard as in “get” rather than soft as in “gel.” In ancient Celtic times this name was Oinogenos, “the one born alone”—another divine title like those we surveyed in Chapter Two.) The three pillars or rays of light he beheld were the rays of divine power that created the world and spelled out the secret name of Celi the Hidden One. Each ray has a name, and these are the same three names you recite in the Rite of the Rays: Gwron, the Knowledge of Awen, is the left hand ray; Plennydd, the Power of Awen, is the right hand ray; and Alawn, the Peace of Awen, is the central ray.

The Analysis of OIW is performed as follows:

Stand at the west of the altar, facing east, and say aloud, “In the beginning of things, Einigen Gawr, the first of all created beings, beheld three rays of light descending from the heavens, in which were all the knowledge that ever was and ever will be. These same were three voices and the three letters of one name, the Name of the Infinite One. Gwron, Plennydd, and Alawn; Knowledge, Power, and Peace.

“A, Knowledge, the sign of the Bounty of Nature.” Make the Sign of the Bounty of Nature, just as you did in the octagram ritual.

“W, Power, the sign of the Cauldron of Annwn.” Make the Sign of the Cauldron of Annwn.

“N, Peace, the sign of the Child of Light.” Make the third Sign, the Sign of the Child of Light.

“A.” Make the Sign of the Bounty of Nature again. “W.” Make the Sign of the Cauldron of Annwn again. “N.” Make the Sign of the Child of Light again. “AWEN.” (Pronounce this “AH-OO-EN,” drawing out the syllables, and making the three Signs again, one with each syllable.) Then lower your arms and continue: “As in that hour, so in this, may the light that was before the worlds descend!” Visualize a ray of light descending from infinite space above you into the cup or horn of mead, transforming the mead into pure light.

Hold that image as long and as intensely as you can. When your concentration begins to waver, release the image and lift up the cup or horn of mead in both hands. Say: “[Name of deity], receive this offering as I receive your blessing.” Pour out some of the mead onto the ground or into the offering bowl. Then raise the cup or horn again and drink the remainder, concentrating on the idea that the energies you have invoked in the ritual are entering your body with the mead to become part of you.

The rituals and other practices covered in this chapter are the tools you’ll need to enact the mysteries of Merlin’s Wheel. Once you’ve learned the elements of the Ovate workings and practiced them enough to do them fairly smoothly, you’re ready to begin. In the chapters ahead, we’ll walk through the eight rituals of Merlin’s Wheel in each of the three circles, and show how the ritual elements come together to help attune your consciousness with the deep spiritual realities woven into the tale of the god Moridunos-Maponos, Merlin the Mabon—a tale that never happened, but always is.

48. See Nichols and Kirkup, The Cosmic Shape, for a detailed exploration of this theme.

49. Pronounced “NOO-iv-ruh.” Nwyfre is the Druid name for that subtle energy of life called prana in Sanskrit, qi in Chinese, and so on.

50. A good case can be made, for that matter, that the stories about Jesus collected in the New Testament would reach more people and make more sense if they were treated as symbolically meaningful legends rather than turned into sacred scripture and believed in a rigidly literal way.

51. This is why many people find that it’s easier to memorize something if you read it aloud.

52. If you’re not sure whether or not you’re closing your throat while you hold your breath, try drawing in a little more breath if you’re holding it in, and pushing out a little if you’re holding it out. If your throat is closed, you’ll feel it pop open.

53. Fortune, The Cosmic Doctrine, 11.

54. The Compleat Meadmaker by Ken Schramm is a good introduction to the art of making mead in small batches at home.

55. Williams ab Ithel, The Barddas of Iolo Morganwg, 49–51.