Don Mattingly was a great hitter because he learned something new from every game he played.

After spending time with Mickey Vernon, I began to gain a lot of confidence in my swing. Lou Piniella, a legendary figure with the New York Yankees teams under manager Billy Martin, was the next guy to have a big impact on my success. Lou was hanging around the batting cage during my first spring training with the Yankees, watching me swing the bat, and told me to use my bottom hand to generate power and to pull the ball more.

Lou was still playing at this point, and he later became a successful hitting coach and manager for several teams. He took the time to show me how to use the bottom hand in my swing; this shred of instructional advice was the last piece of the puzzle for me in my learning curve from a good prospect to a major-league hitter.

Mark Texeira of the Texas Rangers is one of best young players in the game today.

As a left-handed hitter, my stronger hand was my top hand. I had always heard about “getting on top of the ball,” and I looked at the statement to mean quite literally to “hit the top of the baseball.” Now, that would mean to keep the barrel above the ball and above your hands. So if you swing down into the ball, it is like swinging an ax down into a tree.

For the most part, you want the swing to begin in a downward path; your hands are around your ears or shoulders, and let’s say the upper part of the strike zone is a little bit higher than your belt. And so the bat is coming down on the ball, and you are swinging through the ball to finish the swing.

If the pitch is inside or sinking, you still want to use the bottom hand to get down on the ball. This bottom-hand work creates backspin, and that’s how my power jumped to the point where I could hit more than thirty home runs for the Yankees.

Lou Piniella’s message was simple: I should use my bottom hand to try to hit down on the top half of the ball, to hit line drives and grounders, but the net effect was to increase my power by using my bottom hand more to correct and improve the swing, grounded in the simple foundation we built in chapter 1.

I was always taught that with two strikes in the count, I should cut my swing back a little bit or even choke up on the bat to shorten my swing.

If you put the ball in play, you can make something good happen: You might hit a roller through the hole or hit a flare over the infield. The shortstop might bobble a hard grounder. If you don’t hit the ball, you have absolutely no chance of helping your team.

The game has changed a lot since I was playing in the eighties and nineties. My generation of players, guys like Willie Randolph, were embarrassed to strike out as much as the hitters do today.

I believe there’s validity to the value of any hitter cutting down his swing to make contact with two strikes. If you put the ball in play, you’ve got a better chance to help your team.

Fall back on the foundation we built in chapter 1: A square (square = straight line to the ball) stance; a square stride, with the bottom hand going to the ball; movement from Point A to Point B. This is the foundation for a shorter swing that will cut down on your strikeouts and improve your ability to make contact with consistency.

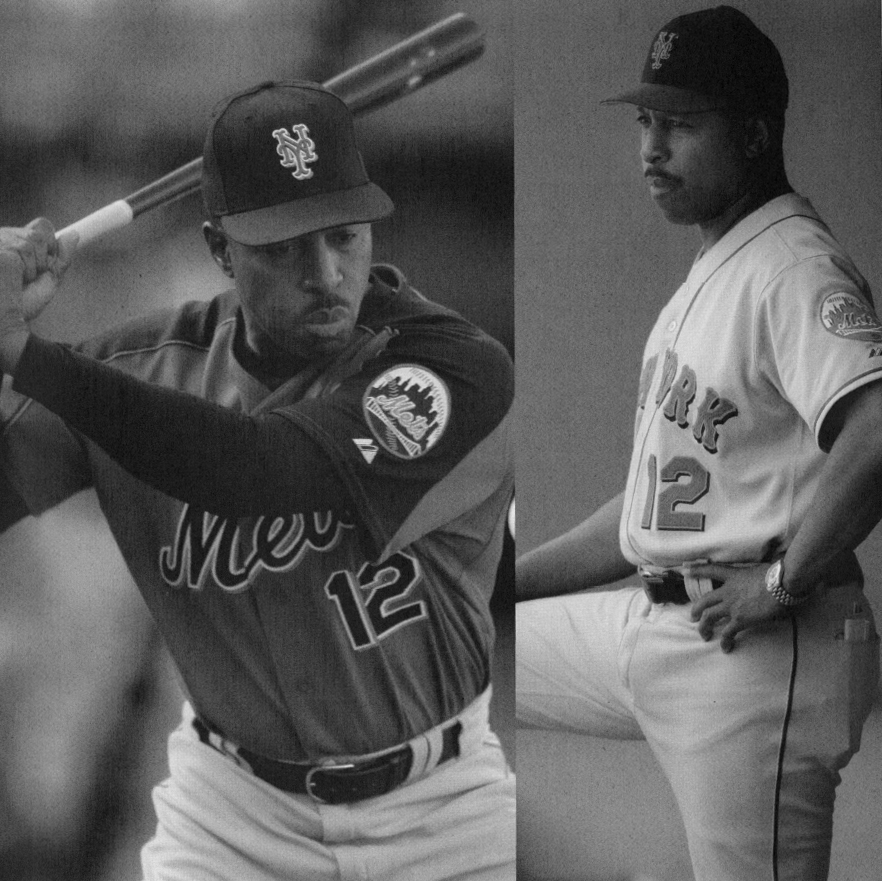

It looks like a need a shave and an attitude adjustment in this photo.

The best way for a young hitter to prepare is to watch the pitcher. Pay attention when he’s warming up before the game. Check out his delivery and stuff while you’re standing in the on-deck circle or sitting in the dugout. Get an idea about what kind of stuff he has and whether he’s throwing strikes.

Pay attention and watch!

That’s true of so many things in this game. Pay attention to what’s going on right in front of you. Don’t let your mind wander and start thinking about where you’re going to eat after the game. Try to use the time in the on-deck circle to your advantage. Consider all the things the pitcher may try to do to get the better of you.

Nothing ever happens without the baseball! If you always know where the ball is, you will never get in any trouble. This is true whether you’re running the bases, playing defense, or trying to find the release point (the point at which the pitcher is releasing the baseball from his hand).

It’s that simple, really. Coaches get so complicated, trying to force kids to think about where their hands and feet are going on the swing. Once you are playing a game, the focus must be on seeing the ball. Keep your head as still as possible. You don’t want a lot of movement when the pitcher delivers the baseball, or it will make it harder to read the ball coming out of his hand.

Your eyes need to be able to give you useful information. Once the pitch comes out of his hand, I want you to focus on the ball. Some pitchers will tip their pitches by throwing fastballs straight over the top or breaking balls with a three-quarter delivery. The change in delivery may tell you what pitch he’s throwing.

But you can’t achieve anything as a hitter unless you can see the baseball. Always study a pitcher as he is getting ready to start his windup. Follow him with your eyes as he goes into his stretch.

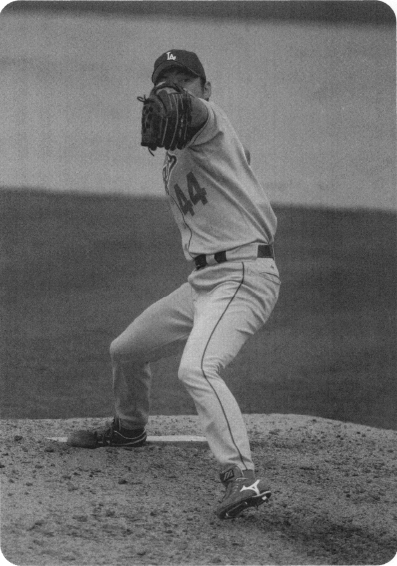

The goal as a hitter is to try to find the spot where a pitcher is releasing the baseball (middle photo). Once the pitch comes out of his hand, I want you to focus on the ball. Always study a pitcher as he is getting ready to start his windup. Follow him with your eyes as he goes into his stretch.

Don’t let all sorts of extra motion in his delivery throw you off track in analyzing what pitch he’s throwing. Stay in the box, don’t abandon your solid foundation, and by studying the pitcher you will be able to find his release point and hit the ball.

Making adjustments at the plate fits in with the whole idea of keeping hitting as simple as possible. The foundation we’ve been talking about creates a straight and smooth stride—without unnecessary head movements; a direct path to the pitch; and perfect balance. That means you are never moving forward until you move back. Your eyes will focus on the baseball coming from the release point. And you will be able to see the breaking ball and the fastball and the change-up.

Early on in my career, I struggled against soft-tossing pitchers, the guys who changed speeds effectively. I had to learn how to adjust my thinking during the at bat. This ability to make adjustments is a skill that only comes with experience. After facing guys who change speeds, you will formulate a plan to sit back on the off-speed stuff and still have the confidence to be able to hit the fastball.

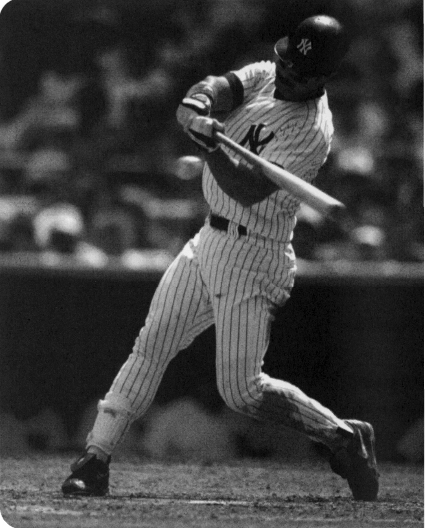

(Left to right): Hideki Matsui is a great breaking-ball hitter; notice how his head stays still during the swing. Remember to be true to the foundation of the swing when hitting a breaking ball—no unnecessary head movement, a direct path to the pitch, and perfect balance

Think about what happens when two cars pass each other on the highway. Let’s say that you are traveling in one direction and I’m traveling in the other direction, and we’re both going 70 mph. I’m not going to have any idea of how fast you’re moving as we pass, nor am I likely to get a clear look at you because I’m only going to see you as a blur of motion.

But if I’m standing still and you’re cruising at me at 70 mph, I can see you coming the whole way. As you get closer, I can see every detail of your car. I can judge the speed. I would know when to get out of the way.

The same thing happens with hitting a baseball. If your balance is off—if you move forward instead of going back to initiate your swing—you’ll have too much head movement to see the ball clearly and you won’t get a good look at the pitch.

Let’s get back to the basics: if everything with your mechanics is solid, there’s no reason why you won’t be able to see the spin or rotation on the ball. But it’s still going to take practice, as hitting a breaking ball is one of the toughest things you’re going to have to learn. And any pitcher who can throw the curveball and the fastball over for strikes is going to be tough to hit against.

Let’s make it even more simple: You have to see the baseball to hit a breaking ball. The breaking ball is tough to hit because it’s in the strike zone for only a split second. The fastball is in the strike zone for a longer time so it’s easier to adjust, but with a curve or a slider you have a very limited window of opportunity to hit the ball while it’s in the strike zone. Now, as you are moving from Point A to Point B with your mechanically sound swing, pop the whip (move back before going forward) to make contact right in that very small window. Bam!—hit that pitch where it’s thrown.

But it still goes back to staying strict with the foundation: A slight, smooth head movement; smooth eye movement; you are seeing the ball come to you; your mechanics are square and in a straight line.

I was probably better than most young hitters in adjusting to hitting the breaking ball when I went into pro ball. I didn’t have much head movement. I didn’t have a long stride. I had a solid foundation of good mechanics.

I credit Rod Carew for showing me the way to build the base that allowed me to hit a good breaking ball. In emulating Rod, I hit with less movement, had a short stride and compact swing, and hit the ball where it was pitched. I wanted to see where the ball was pitched before deciding where to hit it, and that meant being patient enough to wait until the ball reached a certain spot.

Obviously, it helps to have an understanding of the strike zone to become a complete hitter, a guy who can hit any pitch and use the whole field. I took a lot from Rod’s game and it helped to mold me as a player, but I didn’t have his speed and had to be true to what I did best.

You may never be Michael Jordan—or Don Mattingly, for that matter. I could do some things well, but I was no Rod Carew. At the end of the day, you have to work hard to get the most out of your unique skills. Be true to yourself and you can’t go wrong.

Whatever happened in the past is gone. You can’t let the failure of your last ten at bats have an impact on your next ten at bats.

I define a slump as an extended negative period. In baseball, perhaps you’ve been hitless for three or four games. In life, it could mean you had a bad haircut, but you have to give it time to grow back. It is just a temporary setback.

Let’s say I’m spraying line drives all over the field and none of them are dropping for hits. I’m popping the ball up too much. I’m not seeing the ball well. But that’s in the past!

Slumps need to be put in the rearview mirror. Those last ten at bats are gone. They are over. You’re never going to get them back. Move ahead to your next game, which is the only thing you can control. You can’t be thinking that four days from now, you’re going to have to play five games in a row. Focus on the game today. Focus on your next at bat.

It all comes back to keeping things simple. Get a good pitch to hit. Hit a ball hard. Win that individual battle with the pitcher four or five times per day. That’s what baseball is all about. Then you string all those individual battles together. If at the end of the year you’ve had one hundred at bats and you can say you won seventy out of a hundred battles—"I got a good pitch to hit, I hit the ball hard seventy out of a hundred times,” then that’s pretty impressive.

Say to yourself when you’re fighting a slump: “I don’t care if I get any hits. I don’t care where the ball goes. I’m going to hit the ball hard four times today. And I’m going to take whatever I get from that experience and be positive.”

At that point, you can walk away and look in the mirror and can say that you won those battles. Even though you didn’t get any hits, you still won those battles. If you keep winning those battles, you will hit .300 someday. The hits will fall, and you’ll be successful and consistent.