The Bedraggled Army

Dissatisfaction swept over the Army of the Potomac like a midwinter blizzard. Morale plummeted. Men grew bitter. Hope froze.

The chill was far worse than anything Rufus Dawes had seen back in Wisconsin, and it was only late December. The 24-year-old major of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry, born on the Fourth of July in 1838, had watched conditions worsen ever since the debacle in Fredericksburg earlier in the month. Major General Ambrose E. Burnside had led the army to its most lopsided defeat of the war thus far, and the ill winds began blustering shortly thereafter. The squall hit furiously, almost as soon as the army retreated across the Rappahannock River into Stafford County.

“The army seems to be overburdened with second rate men in high positions, from General Burnside down,” Dawes wrote. “Common place and whisky are too much in power for the most hopeful future. This winter is, indeed, the Valley Forge of the war.”1

Dawes, whose great-grandfather rode with Paul Revere on the famous midnight ride in 1775, wasn’t the only Union soldier to allude to the Revolution. “As something of the spirit of ’76 still continues to course through your veins, and as the heroic deeds of our ancesters still bring tinges of patriotic pride to your cheeks, whenever recounted, I will beg the liberty of giving you a short chapter clipped from this present age,” wrote Nathaniel Weede Brown of the 133rd Pennsylvania Infantry in a letter from “Camp near Fredericksburg.” As a “War Democrat,” Brown had conflicted feelings. “This rebellion,” he wrote, “concocted in iniquity and carried on for no other purpose than for the abolition of slavery and the aggrandizement of partisan spite, has cancelled the lives of thousands, destroyed property to the amount of millions.” To Brown, “the butchery and pillage” had just begun. He praised his comrades’ bravery in “fighting in a doubtful cause—for no one can tell what we are really fighting for.”2

President Lincoln did what he could to bolster the army’s flagging spirits. “Although you were not successful, the attempt was not an error, nor the failure other than an accident,” he said, but his praise sounded faint. “The courage with which you, in an open field, maintained the contest against an entrenched foe, and the consummate skill and success with which you crossed and re-crossed the river, in face of the enemy, show that you possess all the qualities of a great army …. Condoling with the mourners for the dead, and sympathizing with the severely wounded, I congratulate you that the number of both is comparatively so small.”3 Small consolation it seemed.

Major Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry may have been the first person to connect the winter of 1862-63 with the Continental Army’s Valley Forge winter of 1777-78. LOC

Ironically, on a December 18th nearly 85 years earlier, Congress had offered praise to another bedraggled American army, calling for a national day of Thanksgiving. General George Washington, leading his ragamuffin band into Valley Forge, paused the army’s march in recognition of the honor.

Now, in 1862, the Army of the Potomac headed into its own Valley Forge, although they had no way to know it. Quickly, though, it became a winter of discontent. Army morale plummeted precipitously in the days and weeks after Fredericksburg. Not even Christmas brightened spirits. “We are suffering very much with cold and hunger,” wrote Lt. Albert P. Morrow of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry—known as Rush’s Lancers—on December 25. “The roads are in such wretched condition that we can’t transport supplies and we can’t buy a single article in this miserable poverty-stricken country.”4

Across the North, things looked just as bleak albeit for different reasons. “[The American people] have borne, silently and grimly, imbecility, treachery, failure, privation, the loss of friends and means, almost every suffering which can afflict a brave people,” editorialized the venerable Harper’s Weekly. “But they cannot be expected to suffer that such massacres as this at Fredericksburg shall be repeated.”5 Unseemly as it appeared, the Union was apparently losing.

“In fact the day that McClellan was removed from the command of this Army the death blow of our existence as the finest army that the World ever saw was struck,” wrote Maj. Peter Keenan of the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry. “What was once, under that great leader, the ‘Grand Army of the Potomac’ is today little better that a demoralized and disorganized mass of men.”6

Twice offered command of the Army of the Potomac before he accepted it, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside knew the job would be too much for him. He finally accepted so political rival Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker wouldn’t get it. Burnside was right, as he proved on the Fredericksburg battlefield in December and on the “Mud March” in January 1862, as well as with his inability to administratively manage the army entrusted to him. LOC

Theater of Operations (Winter, 1862-1863). Fredericksburg sat midway between the opposing capitals. After the December 1862 battle there, followed by an aborted Federal maneuver known as the “Mud March,” the armies went into winter quarters on opposite sides of the Rappahannock River. The Federal supply line depended on the railroad from Aquia Landing, where goods were shipped in from Washington along the Potomac River. The road network northward through Stafford Court House, Dumfries, and onward provided an extra communication and transportation link, although Federals worried about its vulnerability to Rebel raids. The Southern supply line reached up from Richmond along the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad, as well as along the Telegraph Road. Both armies stretched their influences west, although the Federal grip, in particular, became more tenuous the farther it reached beyond the main army, which concentrated along its roads and rail lines.

The army began to hemorrhage more than 200 deserters a day, which immediately sapped the army’s strength and will. By month’s end, the first 2,000 of at least 25,000 deserters had faded from the front. With Washington access tightly sealed at the Potomac River, most made it only as far as Alexandria, where they huddled around campfires with fellow “skedaddlers.” Burnside began the unpleasant but necessary process of rounding them up. On December 24, he issued General Order No. 192. “In order to facilitate the return to duty of officers and men detained at the camp of convalescents, stragglers, &c., near Alexandria,” Burnside ordered an assistant provost marshal general to “repair to Alexandria and take charge of all such officers and men in the various camps of that vicinity as are reported ‘for duty in the field.’”7 Each corps sent an officer and armed troops to round up stragglers and ship them to Stafford’s Aquia Landing, where the returnees were systematically re-clothed, re-equipped and re-armed. Pointedly, Burnside used Regular Army troops to police up volunteer deserters and stragglers.

Although Burnside’s provost marshal force and infantry and cavalry patrols arrested men lacking passes, substantial numbers of men still slipped through. The main desertion path flowed through Aquia-Dumfries-Occoquan. Soldiers walked or caught rides with sutlers, civilians, or fellow soldiers, some of whom brazenly stole wagons. In a common ruse, deserters posed as “telegraph repair work details.”

The wounded had a far easier desertion route through the numerous Washington general hospitals. Once sufficiently recovered, a wounded soldier—frequently aided unwittingly by good-hearted U. S. Sanitary or Christian Commission workers or citizens—easily escaped.

For the non-wounded, desertion from the army’s sector was best achieved by crossing the Potomac River into southern Maryland. Boats hired by deserters were almost certainly operated by men engaged in covert activities. The Confederate Signal Corps and Secret Service’s “Secret Line” operated throughout the war with impunity from Aquia and Potomac Creeks in Stafford all the way up to Maryland. Rebel boatmen were happy to row as many Yankee deserters across the river as possible, probably demanding substantial fees.8

Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart kept Federal occupiers on their toes by threatening supply lines and testing perimeters. LOC

Compounding Union problems, Confederate Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown (Jeb) Stuart, who gained lasting fame for his June and October 1862 cavalry raids around Federal armies, launched a large-scale operation to Dumfries and Fairfax Station on December 27-29, 1862. While of little direct threat to the Federal defenses, this revealed the Federal cavalry’s continued haplessness. Stuart’s ability to raid through and around Union defenses at will frustrated top Union commanders. It also exposed the vulnerability of Aquia Landing, the main Federal logistics center.9

By December 30, the army’s Quartermaster General, Montgomery C. Meigs, had seen enough and let General Burnside know it. “In my position as Quartermaster-General much is seen that is seen from no other stand-point of the Army,” wrote Meigs, who was bureaucratic, patriotic, strategically sound, and naive all at once. “I venture to say a few words to you which neither the newspapers nor, I fear, anybody in your army is likely to utter.” Meigs warned the treasury was rapidly depleting, although prices, currency, and credit remained intact. He sensibly worried about horse feed prices: “Hay and oats, two essentials for an army, have risen,” but it was “difficult to find men willing to undertake their delivery and the prices are higher than ever before.” Meigs feared supplies would run short of fail altogether. “Should this happen,” he noted, “your army would be obliged to retire, and the animals would be dispersed in search of food.” After repeating his warning that the war’s cost was leading to fiscal disaster, Meigs then turned to strategy. “General Halleck tells me that you believe your numbers are greater than the enemy’s, and yet the army waits!” he wrote. “Upon the commander, to whom all the glory of success will attach, must rest the responsibility of deciding the plan of campaign.”

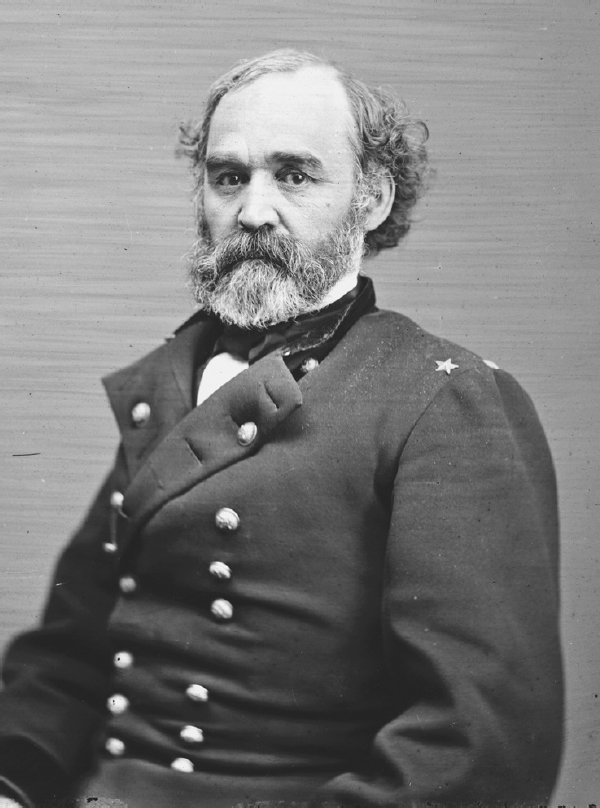

Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs ascended to his position because the previous quartermaster general, Joseph E. Johnston, resigned to join the Confederate army. Meigs proved exceptionally brilliant and effective at his job, although the winter of 1862-63 would prove his greatest challenge to date. LOC

General Meigs finally arrived at his main point: “Every day weakens your army,” he wrote; “every good day lost is a golden opportunity in the career of our country—lost forever. Exhaustion steals over the country. Confidence and hope are dying.”

“An Entire Army Struck with Melancholia”

That the Army of the Potomac could be so weakened spoke volumes about the spiritual gangrene that infected it. “An entire army struck with melancholy,” said an officer with the 140th New York, writing to his hometown paper in Rochester. “Enthusiasm all evaporated—the army of the Potomac never sings, never shouts, and I wish I could say, never swears.”10

The army had been significantly bruised—and undoubtedly humiliated—by its loss at Fredericksburg in December, where the 135,000-man army suffered 12,653 casualties—1,284 killed, 9,600 wounded, 1,769 missing.11 In the immediate aftermath, with Christmas calling soldiers home, the army was hemorrhaging another 25,000 men.

That still yielded about 97,647 after-battle effectives.12 By the end of January 1863, army returns showed some 147,144 combat arms troops. Such a number suggests the army was able to replace and regenerate sufficient combat power drawing on the Washington defenses and on the states. It also suggests personnel accountings may have been padded, confused, or concealed.13 At any rate, there were sufficient men on hand for an “army of quantity”—especially since that army only had to engage an enemy army roughly half its size.

Questions lingered, however, over whether the “army of quantity” was also an “army of quality.” Two years of war had seen heavy attrition in most regiments, injuries, deaths and disease that had reduced them, on average, to about 400 men each out of an original 1,000. Many individual companies reported only 25-30 effectives. Units like the 110th Pennsylvania had so few effectives in early January 1863 that it consolidated its companies from eight to four. However, as most army units had fought at least five battles, the survivors at least had substantial combat experience.

The army was also well-armed. Fully 74 percent of its riflemen carried first-class rifles: .58 Caliber Springfield Model 1861 Rifle Muskets [46%]; .577/.58 Caliber Enfield Rifle Muskets [25%]; or comparable weapons [3 %]. However, when cumulative losses necessitated the redistribution of soldiers within a regiment—such as the 110th Pennsylvania, mentioned earlier—it frequently led to bizarre weapons combinations because soldiers typically kept their original weapons. Such hodge-podges were an ordnance sergeant’s nightmare. For example, Company A, 46th New York Infantry, had eight different weapons on hand in six different calibers.14

Along with their individual armaments, soldiers had the backing of a strong technical specialist infrastructure: administration; ordnance; quartermaster and commissary; signal; and railroad. The army was also backed by the North’s extensive technological, economic, transportation, and industrial superiority.

However, crowing about the Union’s material superiority as the end-all is woefully simplistic, just as it’s equally simplistic to categorically dismiss the quantity and quality of Southern troops’ weapons, equipment, and clothing. Antebellum Congresses had chronically ignored military preparedness, thereby creating institutionalized organization and mobilization issues. It wasn’t that the United States was wholly unprepared for the Civil War; it was wholly unprepared to fight any war.

Historian Fred A. Shannon, writing in the 1920s, suggested that poor food and supply practices made military life unnecessarily difficult. Shannon emphasized a “shortage of supply, poor methods of distribution, inferior materials and workmanship, and [the soldier’s] own improvidence—the latter being largely the result of poor army organization and worse discipline.”15

Poor leadership and administration brought excessive desertions. Pervasive sickness, aided by indifferent camp sanitation and hygiene, brought unnecessary deaths. It took half the war—until roughly the period of this study—for supplies to reach acceptable levels, although the quality of those supplies never fully made muster. Shoes, overcoats, uniforms, and other equipment were all deficient in quality, and soldiers suffered. Understanding the men in this study depends on clearly recalling all of these dimensions.

The Citizen-Soldiers of the United States

Despite its institutionalized deficiencies, the army possessed substantial war-fighting potential. What it most lacked was a winning combination of fighting leaders and troops who knew how to work together with their combat support and service support in the face of a formidable foe.

Naturally, the army’s human element was crucial. It’s surprising then, per Shannon, that the common soldier ranked “as the least-considered factor in the prosecution of the Civil War” by the government.16

The Army of the Potomac, like all Northern armies, consisted almost completely of citizen-soldiers. As such, the men embodied inherent contradictions: Citizens, as the nation’s sovereigns, possessed the power to vote in or vote out their political leaders and vested them with authority to act in their names. They also influenced other voters (e.g., spouses, parents, relatives, friends, etc.). Paradoxically, once in service as soldiers, they became pawns of the political and military leaders to whom they had directly or indirectly granted power.

Early in its history, America had rejected large standing armies in peacetime, so the federal government maintained only a small professional, or “regular,” force. Wartime armies, in contrast, consisted of citizen armies comprised of militia (standing reserve forces) and volunteers (forces assembled in emergencies). These elements, when cobbled together, became “the Armies of the United States” for that war. A remarkable aspect of U. S. mobilization was the institutionalized marginalization of professional soldiers, who generally had to resign in order to gain volunteer appointments.

Such disparate and untrained forces required time and experience to come together effectively, and leading such citizen-armies was far more art than science. A commander had to demonstrate sincere respect—even affection—for his subordinates, yet still be able to order them to risk life and limb with reasonably unquestioning attitudes. This delicate balance was best achieved when commanders of good character were trusted by their men with an implicit compact that soldiers’ lives would not be unnecessarily risked or wasted. Gaining that trust required time. Until then, wartime officers typically began with comparatively little institutional respect from their subordinates. They had to earn the respect of their troops.

Unfortunately, the United States never had a reliable system for picking or training all of its officers to be those kinds of leaders, so results were uneven and improved only gradually during war. Some historians have gone so far as to rate the process as a “little short of disastrous.”17 In the Civil War, direct or indirect political influence within a state was the surest path to selection and promotion for Union officers—hardly the best process to ensure an army of quality. “It is no less than madness to put an officer at the head of a great Army in the field because some ordinary uninstructed men call him smart,” one officer groused.18

At their worst, citizen-officers were strutting popinjays and incompetents, appointed through political influence or nepotism, who conducted military affairs from the poorest foundations: arrogance, martinet tendencies, and insecurity. Their military skills and knowledge were suspect, and their decisions were frequently driven by expediency—to gain promotion or curry favor; avoid explanations and accountability; or dominate powerless subordinates. Officers of this ilk relished personal comforts and recreation, and ignored the well-being of their troops. Historically, these officers made military leadership in a democracy more difficult. The crucible of combat tended to clean up mistakes but, unfortunately, at substantial collateral costs. “Led on to slaughter and defeat by drunken and incompetent officers,” mourned a Connecticut private, “[the ‘soldier of today’] has become disheartened, discouraged, demoralized.”19 One bright spot was that these types of officers usually managed to weasel out of line duty, in a sense self-selecting themselves out.

At their best, though, citizen-officers listened and learned. They developed tactical skills and instincts and administrative abilities that grew steadily through study and practice. They led by example and with prudence, accomplishing assigned missions with minimal losses. They applied good sense and judgment to their commands, and they respected themselves and their soldiers. Their soldiers, in turn, grew to trust them.

Good officers recognized that the key to the army’s effectiveness rested there, at the bottom of the military food chain, with the private soldiers—although few of those soldiers would have understood that fact, even were it explained to them. Success ultimately depended on them. “All we want is competent leaders, men who are capable of the duties to be performed,” said one Mainer, understanding the officer-infantry dynamic just fine, “and we will show the country that we are a mighty army, a conquering host.”20

They were indeed quintessentially American soldiers. As the song goes, “they left their plows and workshops, their wives and children dear,” and answered the nation’s call to arms. They understood that, all questions of manhood and bravery being equal, their side would ultimately prevail because of its economic and industrial strength and its “righteous” cause, the preservation of the Union (emancipation as a cause still remained controversial within the army at the end of 1862). Confident soldiers, “knowing” their side would ultimately prevail, were correspondingly reluctant to risk, sacrifice, or waste themselves. It is universally correct that those who persevered over time did so out of loyalty to their comrades.21

They were also quintessentially American soldiers because they came from all over America: from Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Maryland, Delaware, and (West) Virginia.22 A very small percentage had served in the antebellum Regular Army, but more than 98 percent of them were nonprofessionals.

If they did not vary greatly from general Union Army averages, the soldier of the Army of the Potomac was about five-feet, eight-inches tall and weighed about 143.5 pounds. Thirty percent had brown hair, 25% dark hair, and 24% light hair. About 45% were blue-eyed, 24% had gray eyes, and 31% were brown-eyed. Sixty percent had light complexions. Forty-eight percent were farmers; 24% mechanics (a conglomerate term for those skilled at hand work); 16% laborers; 5% businessmen; and 3% professionals (generally limited then to lawyers, physicians, clergymen and teachers). Another 4% worked in “miscellaneous occupations.” Ages ranged from late-teens to late-20s, with a sprinkling of “older men” in their 30s and 40s. A few, mainly drummer boys and musicians, were as young as 11 or 12 years. A smaller number were over 50 years. A more rigorous statistical rundown puts their average enlistment age a little higher at 25.8 years, and with a median age of 23.9 years.23

They were, therefore, a typically American army of citizen-soldiers, predominantly “fair-haired,” “blue-eyed,” “20-something” farm boys caught up by history’s tides in their nation’s greatest trial. They toughed-out their long, brutal war because they did not want to let down their comrades, families and homefolks (at least those home folks that supported them).

Their average educational level is not known, but, from their writings it can be reasonably speculated to average about six to eight years (four months per year) of formal education. They were literate and could, with wide variation, express ideas and feelings in writing. That fluency had its downside, too. At least one surgeon, for example, lamented the “wholesale swearing among officers and men.” “Why this profanity I cannot imagine,” wondered Dr. Daniel M. Holt of the 121st New York. “It is like water spilt upon the ground; lost to all appearances, yet watering and vitalizing evil passions and ultimately developing a nature fraught with propensities to evil, as naturally as smoke curlingly ascends the zenith.”24

Culturally, the soldiers were innocents set afoot in a strange land with strange sights, unprepared to face troubling realities.25 Few had traveled more than 50 miles from their homes before the war. Most had never seen a black or “foreign” person. Their trip south was to a different world—Virginians were not the only Americans who considered their state “a country”—and these erstwhile Northern farmers, mechanics, businessmen and students carried their pride and prejudices to war. Most became more enlightened, but, in the end, it was not necessary for soldiers to love the people for whom they were fighting to free or protect; carrying out their missions with as little malice as possible was sufficient. Although some war-related hatred did naturally evolve, Union soldiers were not indoctrinated to hate. “You Yankees don’t know how to hate,” one Rebel blurted to a Pennsylvania cavalry officer during the post-battle truce in Fredericksburg in December of 1862. “You don’t hate us near as much as we hate you.”26 For Confederates, whose home territory was being invaded and occupied, the war was by-and-large far more personal.

Three revealing examples demonstrate the experiential confusion faced by the average young soldier in the Army of the Potomac.

In the first instance, a Hoosier named “J. Hawk” issued a War Democrat diatribe on January 9. “This grand army is the worst demoralised it ever was,” he complained. “The boys all say compromise and in fact they say they never come here to free the negroes. At best, I had thoughts of fighting for anything only the restoration of the union, which might have been done before this late hours if our Generals had not worked against each other for the sake of honor, the Generals wate for that Abolition President and War department.”27

In the second instance, on January 12, Lt. George Breck of the 1st New York Light Artillery reported: “Small and large flocks of contrabands continue to pass our camp on their way to Washington. There is every variety of the African. Little negroes and big negroes, with all the intermediate sizes, from—we will not say how many days old, to four score years of age and upwards.” Breck described a “comical sight” in ox carts, wagons and afoot. He revealed his cultural sources referring to “Uncle Toms and Aunt Dinahs, Sambos and Topsys—a complete representation of the colored population, of the ‘poor slave,’ passengers for Freedom—swarming northward in response, we suppose, to the emancipation edict.” Alluding to those he witnessed, Breck described a second exodus to freedom, adding, “They go to Belle Plain or Aquia Creek, and are thence transported to Washington, all their traveling appurtenances being confiscated by government, through the quartermasters, at the place of landing.” Somewhat sympathetically he added, “What provision is made for them on their arrival at the Federal Capital we do not know.”28

In the third instance, a few months later, a young 8th Illinois Cavalry trooper, DeGrass L. Dean, thanked Mrs. J. F. Dickinson of King George County for her kindness to him while on picket duty at their farm (Hop Yard): “[T]hough an enemy to your Country, yet remember me as a friend.” Lieutenant Henry H. Garrett, 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry, also thanked her for kindnesses during the previous (1862) Christmas period.29

Amidst that sea of disparate experience and strange uncertainty, one thing that grounded the men and gave them context was the army’s internal culture—a less quantifiable factor than the demographics that defined them. The soldiers adopted the views, language, practices, and attitudes of their units and fellow soldiers to a remarkable extent. As the war progressed, the ranks thinned, and the chances of survival declined, these internal cultural traits became even more pronounced. Individualism, far rarer than wished or believed, became rarer still in mid-war. Common ideas and attitudes ran through the camps as readily as dysentery. A Pennsylvania surgeon, in as good a position to know both as anyone, remarked on a typical example: “You have no idea how greatly the common soldiers are prejudiced against the negroes.”30 Even more universal was the contempt soldiers had for political meddlers in Washington and pessimistic naysayers on the homefront. The men circled wagons and banded together to withstand the onslaughts of the perceived uncaring outer-world, and their units became their world instead.

That homogeneity covered social views, as well. The army was insensitive and prejudiced concerning racial, ethnic, regional, denominational, class and other social issues—no doubt attitudes that carried over from the larger society. In particular, blacks and post-1840s Irish-Catholic and German immigrants were decidedly “outside the circle” of the relatively homogeneous mainstream population of Scots-Irish-Protestants and English-Protestants. With regard to race specifically, their views were awash in ignorance and flavored by minstrelsy and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They abounded with anti-foreign “know nothing-isms,” prejudiced jokes and criticisms of “darkies,” “niggers,” “‘ouirishmen’,” “paddies,” “papists,” “Germans,” and “Dutchmen.” Despite their common sacrifice and suffering in nearly two years of war, such men were still looked down upon and referred to only by ethnic slurs. With specific regard to anti-black racial prejudice, the incessant use of “nigger—already a socially offensive term in many places in the North—was sometimes used for intentional effect, but sometimes born of complete ignorance. A simple manifestation of white societal dominance, it was a political code-word, especially among Democrats, that expressed political outrage about the Emancipation Proclamation and Lincoln’s expanded war aims.

Despite other shortcomings, patriotism and faith provided the bedrock for most Northern soldiers. Patriotism remained evident even during this darkest of periods and among the most discontented men.31 Faith, for the majority who professed it, followed suit. Biblically informed that man did not live by bread alone, faith relieved their suffering and strengthened their resolve. A substantial component of the army’s morale derived from its extensive religious activities. Although no one this side of heaven could read men’s hearts to discern sincerity from hypocrisy, ample evidence showed religion was alive in soldiers’ lives. Ministers and religious workers flourished, and faith revivals blossomed. U. S. Christian Commission delegates and workers, American Bible and Tract Societies, and the U. S. Sanitary Commission personnel all provided substantial spiritual support.

During stable periods, with time for reflection, soldiers came to grips with their faith. Conversely, sedentary and isolated camp life also bred vices (e.g., drinking, gambling, and sexual dalliances). These realities curiously interacted: religious soldiers, repulsed by moral decay, were compelled toward church activities and religious expressions. Perceived sanctimoniousness sometimes drove secular men to drink and rebel.32

Naturally, there were different experiences. Soldiers from strong religious families generally maintained their faith. Others with no religious backgrounds at all, grasping for meaning in a long bloody war and hard life, found new solace in the gospels. Generational differences amongst the soldiers revealed significant traits. Those born before 1822—members of the “Transcendental Generation”—tended to be idealists, prone to deep spirituality and generally unable to compromise on principle, possessing “inner-driven passions.” They almost always believed themselves “right,” even when their views changed. Transcendentals were the driving forces in religion and literature of that era, and they influenced the other generations in close quarters. Those soldiers born after 1822—the “Gilded Generation,” which made up most of the actual combatants—were more reactive, realistic, cynical, pragmatic, and non-idealistic. The third cohort, the “Progressive Generation”—those born after 1843—adapted to the carnage and became pragmatists for life.33

“Of one thing at least we may be confident,” wrote Rev. A. M. Stewart, chaplain of the 102nd Pennsylvania Infantry: “the incoming period will be greater than its predecessor—fuller of stirring, important, and decisive events. Jesus is revolutionizing the globe, and each successive annual not only brings nearer, but with accelerated speed, His reign of peace and love.”34

On the Hoof

There was also a significant non-human component of the army. Largely overlooked by historians were the army’s 60,000-70,000 horses and mules, generically termed “animals.” They provided all of the logistical “lift” and mobility for the vast force. They also represented a vast number of mouths to feed and hooves to shoe, and they produced tons of manure that needed to be disposed of. Unfortunately, unlike the men, we only have accounts about them, not by them. Nevertheless, these fellow actors in the drama were documented adequately and deserve analysis.

A 1911 study reflected that Civil War animals were the victims of general problems in organizing and training the Federal cavalry. They too paid an unpreparedness price—“a tremendous loss in horse-flesh”—especially during the war’s first two years. Some 284,000 horses had been furnished to fewer than 60,000 Federal cavalrymen during the first two years of the war alone—an astounding four horses per man. The study blamed non-combat animal deaths on “ignorance of inspecting and purchasing officers, poor horsemanship by untrained men, control of tactical operations of cavalry by officers ignorant of its limit of endurance, the hardships inseparable from the great raids of the war, and … oftentimes gross inefficiency and ignorance on the part of responsible officers as to the care of horses in sickness and in health.”35

Winter weather and constant use kept blacksmith shops working constantly to keep horses and mules sufficiently shod, but high demand taxed thin resources. LOC

The animal care system was incomplete during the “Valley Forge” winter, but it paid great dividends afterward.36 Veterinary surgeons were added (on paper) beginning in March 1863, but they proved difficult to find and recruit in adequate numbers. Probably as an expedient, veterinary sergeants were added to company tables of organization about this time. The cavalry therefore depended on its own inadequate resources to maintain large numbers of animals.

The 1911 study continued: “The bane of the cavalry service of the Federal armies in the field was diseases of the feet. ‘Hoof-rot,’ ‘grease-heal,’ or the ‘scratches’ followed in the wake of days and nights spent in mud, rain, snow, and exposure to cold, and caused thousands of otherwise serviceable horses to become useless for the time being.” Prior to these events, the army’s remount replacement needs exceeded 1,000 a week.37

Mules, as recalled by Warren Lee Goss in 1890, had specific ties to the “Valley Forge” army. “I believe it was General Hooker who first used the mule as a pack animal in the Army of the Potomac,” he wrote. The stoic creatures drew both Goss’s admiration and consternation. Six normally pulled a wagon. Remarkably sturdy and hardworking in battle and on the march, their steadiness under fire was noteworthy. Alternatively, the mules’ notorious “independence of thought and action” befuddled handlers and supply recipients. Goss wrote mules lacking feed were known to eat “rubber blankets, rail fences, pontoon boats, shrubbery, or cow-hide boots, with a resignation worthy of praise.” Despite such destructive eating habits, the mule was rated the most effective animal in dealing with Virginia’s “miry clay” and mud. Goss added, “Not least among [the army’s] martyrs and heroes was this unpretentious, plodding, never-flinching quadruped.”38

Pack mules, as an innovation, initially left something to be desired. “I don’t know who it was that during the war invented the pack mule system,” Goss admitted. “The pack mule, when loaded with a cracker box on each side and a medley of camp kettles and intrenching tools on top, was, to express it mildly, grotesque. At times, when in an overloaded, top-heavy condition, I have known him to run his side load into a tree, and in this manner capsize with his load, and it was comical to see him lying on his back with a cracker box on each side, and his heels dangling dejectedly in the air, a picture of patience and dignity overthrown; and in his attitude looking like a huge grasshopper.”39 Other observers described mules divesting their pack loads by scraping split-rail fences until their loads tumbled. However comedic their appearance, mules suffered heavy losses: killed in battle; worked to death in interminable mud, sleet and snow; or killed by apathy, poor feeding and mishandling.

Despite their large size, equines were extremely fragile. Although they’d been long used by armies, horses were not naturally fitted for war. “In the wild, they travel in herds, moving and eating constantly,” says historian Jerrilynn Eby MacGregor. “Their stomachs are quite small relative to the rest of their body size and they were ‘designed’ to spend most of their waking hours nibbling at grasses and other vegetation. Left on their own, they wouldn’t normally have access to a large volume of food at any one time. Because they are grazers, most of their food is quite fresh. Vegetable matter that has died and molded would never be willingly consumed by a horse left to its own devices.”40

Even in camp, horses had special risks. Confined horses in pens or stables drastically changed their eating patterns. Ideally, they received two large meals a day, along with hay to chew on, and their feed would be “fresh and free from mold spores, dust, or other contaminants.” More aggressive horses, often at risk of their own lives, would eat other animals’ food. The army’s animals were, like its men, highly susceptible to then-unknown bacterial and viral infections. Infections, especially among confined animals, could spread rapidly, even wildly.

An army might move on its stomach, as the old saying goes, but it doesn’t move at all without horses. Equines provided essential service for cavalry and artillery—not to mention basic transportation and communication services—and comprised a unique set of challenges for the quartermaster’s department. LOC

Operational areas like Stafford imposed special tyrannies on animals. Mosquito-borne infections abounded in soggy, swampy areas. Fungus affected animals’ skin, and such infections, often called “rain rot,” were highly contagious and easily spread by shared saddles or saddle pads. Every part of the horse was susceptible, but especially backs and belly, making it impossible to put saddles on infected horses. Wet hooves were prone to fungal infections, most commonly “hoof-rot” and “thrush.” Of particular concern was the “frog”—the soft, triangular-shaped wedge of tough flesh on the bottom of each hoof, which helps pump blood up from the animal’s feet and legs. The deep crevice on each side of the frog, when constantly wet, was particularly vulnerable to fungal infections. “Thrush,” highly contagious, caused the frog to become so tender and inflamed that animals were immobilized.41

Animals had unique logistics requirements. Ensuring reliable horseshoe resupply necessitated mobile “traveling forges” traveling with company-level equestrian units in the cavalry, artillery, and quartermaster departments. Forges were amply equipped with a bellows, windpipe, air-back, sheet-iron fireplace back, fireplace, fulcrum and bellows-support pole, bellows hook, vise and coal box—all on two wheels. Accompanying limbers had tools such as chisels, hammers, tongs, approximately 200 pounds of horseshoes, and 50 pounds of nails. Well-made and well-applied horseshoes were absolutely essential, especially for animals worked on rough, stony terrain. In the wild, the hooves of unshod horses wore down naturally; at work, horses’ feet experienced greater wear and tear. If worn down to nubs, the horses became unserviceable. Shoes, necessary for working horses, could further contribute to their demise. Expertise in shoeing was especially critical—a nail placed too near the hoof’s quick could make an otherwise healthy animal lame. A shoe coming partially free could twist around and cause damage to an animal’s other feet or legs. A lost front shoe needed to be replaced immediately or the remaining one had to be pulled, or risk lameness.42

Federal horse procurement should have been relatively simple given that approximately 4.7 million horses existed in 1860 in the North and West. However, as with manpower, no reliable mobilization system existed prior to the war to provide necessary animals. Initially, from April 1861 to July 1862, individual soldiers could provide horses that could be “rented” to the army at 50 cents per day (owners bore responsibility for replacements). After July 1862, the Federal government procured all animals. Unfortunately, that still involved states, mustering authorities, and individual regiments. Initial animal purchase amounted to $20,000,000 for 150,000 horses. Such volume resulted in fraudulent sales and other criminality.43

The months-long occupation of Stafford during the “Valley Forge” winter was especially harsh on animals. “In the months following the Union repulse at Fredericksburg,” said one account, “Union cavalry horses suffered so extensively from lack of cover and forage that many animals ate each other’s manes and tails down to the flesh. Horses died on the picket lines by the scores.”44 Meigs had worried in December 1862 that the army might have to turn its animals loose to forage—a practice routinely exercised by cavalry units on extended picket/outpost duty and on raids and patrols. One horse-savvy witness during the winter noticed that the army’s unserviceable horses were regularly turned loose to fend for themselves.

The Burden of the Wagon Train

The Army of the Potomac also had well-documented evolutions in its “man-animal-wagon” history. The army struggled for its entire existence to determine proper numbers of wagons for baggage, ammunition, and food trains. Lack of standardized loads created variances, which in turn led to logistics problems. Wagon allowance per regiment was a special concern. Meigs started with the Napoleonic standard of 12 wagons per 1,000 men—in other words, roughly a dozen wagons per regiment in 1861. Commanders, however, submitted requests ranging from 6 to 15 wagons per regiment. These basic numbers affected campaigns, tactics, and operations.45

Road conditions affected things even further. On good roads, four horses could pull a wagon laden with 2,800 pounds. A six-mule team on a macadamized road, meanwhile, could pull 4,000-4,500 pounds per wagon. In all cases, that included five-ten days’ grain for the animals pulling the freight. Good roads, incidentally, could allow speeds of only 2 to 2½ miles per hour—the typical speed for infantry not on a forced march. Of course, good roads during the Civil War were a rarity, and in Stafford, in particular, they were seldom existent without “corduroying” (laying parallel logs across the roadbed).

Each wagon, of course, came with its own animal team. That meant every wagon train needed to carry adequate feed for those animals. Supply trains typically carried 12 pounds of grain per horse and 9-10 pounds per mule, plus 14 pounds of hay or fodder, or a total food weight of 26 pounds per horse and 23-24 pounds per mule. Each animal additionally required about 15 gallons of water a day.46

Actual reported numbers of the army’s wagons and animals varied as widely as those of manpower. On the Peninsula, the army began with a standard of 45 wagons per 1,000 men and had 21,000-25,000 animals for about 5,000 wagons supporting about 110,000 men. These far exceeded Meigs’ Napoleonic standards.

To alleviate the pressure, the army’s chief quartermaster, Rufus Ingalls, looked to acquire more animals. By the end of October 1862—despite a severe hoof-and-mouth epidemic in the weeks after the battle of Antietam—he managed to acquire 3,911 baggage and supply wagons and 37,897 animals. Those additions brought the army to nearly 6,000 wagons—including, presumably, 1,000 ambulances—and 60,000 animals by the Fredericksburg campaign. This force was calculated capable of hauling ten days’ supplies, and about half were allotted for subsistence for men and animals.

Fredericksburg and the subsequent “Mud March” operations in January took further tolls. By March 1863, the army’s inventories fell to 53,000 horses and mules and 3,500 wagons. Reduction in wagons did have a positive effect, though, in that it freed more animals—as many as 22,000 mules—for use as pack animals, capable of carrying the equivalent of 1,800 wagons. This effectively raised the carrying capacity to 5,300 wagon-equivalents or 33 “wagons” per 1,000 men (regiments at this point were averaging 400 men; many were half that size).47

By Chancellorsville, Ingalls estimated that the army achieved a balance of some 20 wagons per 1,000 men, hauling seven days’ worth of supplies. When it actually marched to Chancellorsville in April, the army had 4,300 wagons (30 per 1,000 men); 8,889 horses and 21,628 mules, and 216 pack mules (1 animal per 4 men).

To simply count beasts, however, overlooks a crucial fact: hauling an individual pack load is more difficult than hauling a wagon. In other words, the animals and their roles were not interchangeable. Readily re-supplying combat units closer to the scene of action, as appealing as that was, was trumped by difficulties managing long columns of independent-minded pack animals.48

Subsistence (and nourishment) requirements—whether in battle, on the march, or in camp—were equally elusive. A 1,600-pound horse drew about 70-75 percent of its necessary daily nourishment from the supplies carried by the train. The remainder—again per Napoleonic concepts—was to be foraged. But, again, what worked for Napoleon didn’t necessarily work in America. Statistical analyses suggest that American conditions made foraging more difficult than it had been in Europe.49 If the animals’ efforts required more strenuous exertions, then they were only able to get about 60 percent of their basic nourishment. Mules drew a greater percentage of their nourishment from feed than horses—80-90 percent. As a result, a “hidden nutritional factor” resulted in high animal attrition. This nutritional deficit persisted through the Fredericksburg campaign and into the “Valley Forge” winter and led to animal losses. Subsistence improvements were enhanced by standardization—what historian Edward Hagerman terms “baggage reform,” or the amount of baggage that moved with the army.

Despite its flaws, the army’s logistical and transportation systems were improving by the winter of ’62-’63, approaching a level where the entire army—then eight infantry corps with cavalry and artillery—could operate for ten days away from its logistics base. Much of that was due to improvements in railroad operations, which facilitated army resupply in static situations and during campaigns by advance stockpiling and managed movements. Railroad and complementary waterborne support, where operative, reduced dependence on inferior roads.50

Reckoning proper numbers of wagons and their effective coordination with road, rail, and steamboat resupply continued for the rest of the war. These macro-dimensions set the scene for increased army micro-focus on the individual soldier’s carrying capacity for weapons, equipment, and supplies. The key was development of well-founded standard operating procedures that factored in experience and changing operational conditions. Where norms were developed, analyzed, and tested, they proved significant and set new standards.

“Interior Administration”: A Concealed World of Sin

These were many of the things Meigs had fretted about when he wrote to Burnside in late December. “In my position as Quartermaster-General much is seen that is seen from no other stand-point of the Army,” Meigs had written.

Ninety-six years later, writing with the benefit of hindsight, the faculty of the United States Military Academy saw many of the same things Meigs commented upon. The faculty examined the army’s general military effectiveness at the end of Burnside’s tenure—which would last less than a month after Meigs wrote to the congenial but befuddled commander. In an under-stated, professional, and telling historical judgment, the faculty wrote: “When Hooker had relieved Burnside after the disastrous Fredericksburg campaign, he found the Army of the Potomac in a low state of morale. Desertion was increasing, and the army’s own interior administration—never too good—had deteriorated.”51

The military-bureaucratic term “interior administration” conceals a world of sin. The army was as political a beast as anything in Washington, and the intrigue, subterfuge, and bickering that went on was at least as serious a threat to its survival as the Army of Northern Virginia. Poisonous and unproductive internal relations at every level of the army damned and delayed its progress as an effective field force.

Perhaps most significantly, the Army of the Potomac’s “interior administration” was demonstrably inferior to that in Robert E. Lee’s army, where mission-type orders, civil social discourse, personal interaction, common purpose and trust, and comradely feelings permeated. The Army of the Potomac, at the beginning of January 1863, had a long way to go to achieve a level of basic military teamwork and cooperation remotely worthy of the terms.

Official records, especially correspondence between generals and officers of this period, shed necessary light. Seemingly, no commander could issue an order to a subordinate without including a snide or sarcastic comment or a vacuous tutorial on performing the simplest task. Phrases like “send a good brigade” or “have it commanded by an energetic officer” belied a command in which insecurity shadowed and distrust permeated seemingly every command. Similarly, officers could not share problems with superiors without being concerned about rebuff or ridicule.

Analogous problems existed in the army’s external relations with Washington authorities. The political atmosphere of the capital clouded the text of even the simplest written orders. Commanders felt second-guessed or judged by some higher authorities, politicians, or inquiry boards. The army’s officer corps, infected with demonstrable careerists, political hobgoblins, opportunists, and dysfunctional factions (or perceived factions), could never presume loyalty from any quarter, above or below.

Fortunately, there were men of merit and conviction who negotiated these obstacles and rose to more responsible positions. They just needed the time to do it. In fact, that was the one thing this entire army required: more time.

With these aspects as background, we can now begin to unravel the chronology of the army and its men and animals in their 1863 “Valley Forge.”

1 Rufus R. Dawes, Service With the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Marietta, OH: E.R. Alderman & Sons, 1890), 115.

2 BV 74, part 11, FSNMP.

3 Abraham Lincoln, “Message to the Army of the Potomac,” December 22, 1862 as collected by Don E. Fehrenbacher, ed., Lincoln: Speeches and Writings 1859-1865 (New York, NY, 1985), 419.

4 Eric J. Wittenberg, Rush’s Lancers: The Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War (Yardley, PA, 2007), 70.

5 Harper’s Weekly, December 27, 1862.

6 BV 271, part 1, 204; FSNMP. Maj. Peter Keenan, letter, 1/30/63.

7 Field-printed order, Author’s Collection.

8 “Secret Line” descriptions in: William A. Tidwell, James O. Hall, and David W. Gaddy, Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln (Baton Rouge, LA, 1988); William A. Tidwell, April ’65: Confederate Covert Action in the American Civil War (Kent, OH, 1995).

9 Brigadier General Vincent J. Esposito, USA (Ret.), ed., The West Pont Atlas of the American Wars (New York, NY, 1959), Volume I.

10 John J. Hennessy, “We Shall Make Richmond Howl: The Army of the Potomac on the Eve of Chancellorsville,” in Gary W. Gallagher, ed., Chancellorsville: The Battle and Its Aftermath (Chapel Hill, NC, 1996), 1-35. The letter, signed “Adjutant,” appeared in the February 3, 1863, Rochester Democrat and American.

11 Thomas L. Livermore, Numbers and Losses, 96.

12 An ordnance-based analysis by NPS Historian Eric J. Mink demonstrates that, as of December 31, 1862, the army reported 80,569 rifles in its line infantry inventory. Subtracting that rifle inventory number would yield a remaining 17,078 non-rifle-bearing soldiers, a reasonable number to accommodate line and staff officers, staff noncommissioned officers and military support functionaries (not including large numbers of hired and volunteer civilians).

13 A cautionary note: because of the dubious nature of some of the record-keeping, all unit/organization numbers used here or in any work are mere illustrative “snapshots” or estimates.

14 BV 322, part 9, FSNMP. The 110th Pennsylvania consolidated its remaining companies as follows: A with K; B with D; E with F; and G with I. Additional weapons data provided by NPS/FSNMP historian Eric J. Mink, based upon returns of December 31, 1862.

15 Fred A. Shannon, “The Life of the Common Soldier in the Union Army, 1861-1865,” Chapter 7 in Michael Barton and Larry M. Logue, ed., The Civil War Soldier: A Historical Reader (New York, NY, 2002). Original article published in Mississippi Valley Historical Review (March 1927), Vol. 13, No. 4, 465-482.

16 Ibid.

17 See Shannon, for one.

18 Francis Augustín O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 491. O’Reilly’s original source was a December 19, 1862, letter by Gen. Erasmus Keyes, speculating on a rumored change of command.

19 Stephen Sears, Chancellorsville (Mariner Books, New York, 1996), 16. Author Sears quotes from a February 14, 1863, letter by Private Robert Goodyear of the 27th Connecticut Infantry to “Sarah,” found in the archives of the U. S. Army Military History Institute in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

20 George Rable, Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! (University of North Caroline Press, Chapel Hill, 2002), 400.

21 James M. McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (Oxford, UK, 1997).

22 West Virginia would not become a separate state until the summer of 1863.

23 Appendix in Ralph Newman and E. B. Long, The Civil War: An American Iliad, 2 vols. (Grosset & Dunlap, 1956), vol. 2.

24 James M. Greiner, Janet L. Coryell, and James R. Smither, eds., A Surgeon’s Civil War: The Letters & Diary of Daniel M. Holt, M.D. (Kent, Ohio, 1994), 65.

25 Newman and Long, The Civil War, Vol. 2, 219, 221-222.

26 Catton, Glory Road, 69-70.

27 http://www.rootsweb.com/~inhenry/letters1863.html (accessed on January 25, 2000).

28 Information on transiting slaves provided by John Hennessy from FSNMP files.

29 BV 120, FSNMP.

30 Paul Fatout, ed., Letters of a Civil War Surgeon (West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 1996), 53. The letters are those of Maj. William Watson of the 105th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

31 Rable, Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!, 400.

32 Recent scholarship has illuminated the war’s spiritual aspects. See George Rable’s God’s Almost Chosen People: A Religious History of America’s Civil War (Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2010) and Steven E. Woodworth’s While God Is Marching On: The Religious World of Civil War Soldiers (Univ. Press of Kansas, 2003).

33 William Strauss and Neil Howe, Generations: The History of America’s Future (New York, NY, 1991).

34 Alexander Morrison Stewart, Camp, March and Battlefield; or, Three and a Half with the Army of the Potomac (Philadelphia: J.B. Rogers, 1865).

35 Captain Charles D. Rhodes, General Staff, U. S. A., “The Mounting and Remounting of the Federal Cavalry,” in Francis Trevelyan Miller, ed., The Photographic History of the Civil War, 10 vols. (Castle Books, NY, 1957), Vol. 4, The Cavalry, 322-336.

36 The crown jewel of the animal care system was a preparation, rehabilitation and remount depot at Giesboro Point, near Washington. It was completed in July 1863 at a cost of over $2 million and was capable of treating 30,000 animals.

37 Captain Charles D. Rhodes, General Staff, U. S. A., “The Mounting and Remounting of the Federal Cavalry,” in Miller, ed., The Photographic History of the Civil War, vol. 4, The Cavalry, 322-336.

38 Warren Lee Goss, “Carrier of Victory? The Army Mule,” Civil War Times Illustrated (July 1962), Vol. 1, No. 4, 17-19. Derived from Warren Lee Goss, Recollections of a Private: A Story of the Army of the Potomac (Thomas Y. Crowell and Co., 1890).

39 Ibid.

40 Correspondence with Jerrilynn Eby MacGregor.

41 Ibid.

42 Captain Charles D. Rhodes, General Staff, U. S. A., “The Mounting and Remounting of the Federal Cavalry,” in Miller, ed, The Photographic History of the Civil War, Vol. 4, The Cavalry, 322-336.

43 Ibid.

44 John V. Barton, “The Procurement of Horses,” Civil War Times, Illustrated (December 1967) Volume VI, No. 8, 16-24.

45 Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (Indiana Univ. Press, 1992), provides important insights on mobility and sustainability. See also Chapter 2, “Tactical and Strategic Organization,” and Chapter 3, “More Reorganization: The Army of the Potomac,” and especially 44-46, 62-65, 70, and 73-74.

46 Ibid. Required water consumption amount from National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

47 Ibid.

48 Hennessy, “We Shall Make Richmond Howl.”

49 Citing a 1960 Military Affairs 24 article by John G. Moore.

50 Hennessy, “We Shall Make Richmond Howl.”

51 Esposito, West Pont Atlas, Map 84.