Longing for the Spring Campaign

On the morning of March 24, 1863, the II Corps division of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock assembled near the banks of the Rappahannock River. Evergreens of pine and laurel and holly stood out among the brown trunks of winter-slumbering maples and oaks. The attention of the men, however, was focused inwardly toward the center of their hollow-square formation. There, three men convicted of cowardice were about to be drummed out. The perpetrators’ heads had been shaved on one side, and they bore large boards emblazoned “Coward.” Followed by sentries with fixed bayonets, the cowards were marched in front of the lines. “The Rogue’s March” thundered in their ears from a hundred drums and fifes. Sgt. C. Hickox of the 27th Connecticut Infantry, part of Col. John R. Brooke’s fourth brigade, watched in fascination. “The performance was as ceremonious as a grand review,” he later wrote.1

The division had formed “in sight of Fredericksburg, and on the ground where Washington had chopped the cherry tree and ridden the colt, and lived and played when he was a little boy,” Hickox reported. Probably unknown to him, his lone division outnumbered Washington’s entire Valley Forge army.

“Dimly beyond,” Hickox later wrote, “we caught the outline of the rebel works as the sunshine lifted gracefully the mist above the graves of our ten thousand Dead.”

Watching the public spectacle inflicted on the cowards had its desired effect on Hickox, who admitted he might have played a little possum at the division hospital. “I left the hospital, threw my medicine in the fire, and got well,” he admitted in obvious good humor. “The habit of eating is an old one, but having become obsolete among soldiers, has been revived by Joseph Hooker. For the first time since leaving Washington I have all the good food I want.”

He concluded on a darker note, however—one that had become familiar throughout the army: “I wish every copperhead of the North might be made to pass the same ordeal at the point of a bayonet.”2

While resentment continued to boil toward the threat back home, Federal soldiers more and more cast their gaze across the river toward Fredericksburg and Lee’s army in the hills beyond.

* * *

Soldiers and officers alike had observed “the Rebels” throughout the “Valley Forge.” Being so close for so long, with standing orders not to provoke or engage, both sides had been respectful, and some men had even engaged in occasional humorous banter and antics.

“The rebel officers are tall and nervy, being well dressed, having a fine suit of gray; their badges of rank being upon the coat collars instead of their shoulders, like ours,” wrote a member of the 108th New York, “R. E.,” to the Rochester Democrat and American. “Their soldiers, however, are a motly looking and motly clad lot of ‘fellows.’ We discovered a goodly sprinkling of Uncle Sam’s boys’ clothing among them. We couldn’t help thinking that they must be either contemptibly mean or awfully hard up, else they would have sufficient pride to choose and demand a military dress—one that should be uniform and national.” “R. E.” described their officers as talkative and gallant with the ladies.3

A recurring theme continued in soldier letters and unit resolutions: the Army of the Potomac harbored a deep respect for its Confederate foes, especially the common soldier of Lee’s army. Regardless of their appearance, “Lee’s Miserables” had earned the Federals’ awe by their battlefield courage.

Cavalry Problems Linger

Not all Confederates sat atop the far heights, however. At 5:00 p.m. on March 14, Daniel Butterfield sent cavalry commander George Stoneman a dispatch from spy Ernest Yager: “Enemy under the impression that this place (Dumfries) has been evacuated and is ravaging the country.” Yager noted 250 of Hampton’s cavalry were headed toward the Occoquan and moving freely between Brentsville and Dumfries. He had seen no Federal cavalry to oppose them.

Although willing to deal with the situation, a March 15 affair showed that Stoneman’s cavalry corps wasn’t necessarily ready. A small patrol of the 8th Illinois Cavalry—one corporal and six cavalry troopers—was captured between Dumfries and Occoquan. The patrol had gone to Occoquan at 4:00 p.m. and was returning about 8:00 p.m. About 3 ½ miles above Dumfries, they were ambushed by a dismounted party of 20-25 men “lying in a marsh on both sides of a deep ravine through which they had to pass.”

When filing his report about the incident, the regiment’s Capt. John M. Southworth guessed that the Federals had tried to run off on foot to avoid capture; three of their sabers had been found nearby.

Stoneman endorsed Southworth’s report on the seventeenth and included a tirade. “These annoyances will continue until some stringent measures are taken to clear that section of the country of every male inhabitant, either by shooting, hanging, banishment, or incarceration,” he growled. “I had a party organized some time ago to do this, but the commanding general did not at that time think it advisable to send it out.”

Lieutenant Colonel David Clendenin was faulted for sending less than a platoon on patrol. In arresting him on March 16, his commander, Alfred Pleasonton recommended that “the rebel partisans and bushwhackers be cleared out from the vicinity of Occoquan and Brentsville [both in Prince William County] by a command from this division. One brigade with a few guns would suffice.”

Stoneman wasn’t so sure. “A great portion of the country is of such a nature that it is impossible for cavalry to operate in it, and to perform the duty properly will require the cooperation of an infantry force,” he predicted in his March 17 tirade. “The country is infested by a set of bushwhacking thieves and smugglers who should be eradicated, root and branch.”4

Hooker’s reply, issued on March 26, was telling. “If there are any of the male portion of the community operating as bushwhackers or guerrillas against our troops, and the facts can be proven, let them be arrested and brought in,” he ordered. “The commanding general cannot understand why our cavalry cannot operate where the enemy’s cavalry prove so active.”5

Cavalry duty in the area was not all excitement. “Once more our detachment is engaged in the necessary, but severe, duty of picketing,” lamented “Genesee,” an 8th New York Cavalry trooper, in his March 25 letter to the Rochester Daily Union and Advertiser. To the southwest of Dumfries, the line had been drawn in closer “owing to the great numbers of men required to picket such contended lines as were first formed,” he explained. “During our stay in Stafford our horses and selves became much recruited, so the we became prepared to do more effective service considering our little experience than could have been expected from raw troops on their first enterprise.”

Enemy activity against the 8th Illinois and 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiments had sparked a sharp response from the 8th New York, which mounted a strong reconnaissance and boldly went out into the forests, sabers clanking. “We crossed Cedar River, where we expected to find the enemy, but he had prudently left in good season, and we were compelled to return to camp, which we reached about 6:00 p.m., having been eighteen hours in the saddle and traveled over fifty miles, through mud and mire in the fruitless pursuit of our wary foe.”6

Fruitless, perhaps, but the Federal cavalry was becoming more aggressive, and troopers like “Genesee” were sounding far more confident than at the month’s beginning. They now operated at night, rode deeper into enemy country, and maintained good order. Their Confederate counterparts still outmatched them, however, due to the eternal motivational difference between soldiers operating in foreign spaces and those protecting their own. Counter-insurgency or rear-area security operations remained illusive. When Union cavalry could or would not venture outside perimeters, then the Confederates—regular or irregular—still owned the night.

Hooker expected more. “I know the South, and I know the North,” he contended as part of a furious, windy discussion with Stoneman. “In point of skill, of intelligence, and of pluck, the rebels will not compare with our men, if they are equally well led. Our soldiers are a better quality of men.” This North-centric nonsense was followed with a more accurate assessment: “[The Federals] are better fed, better clothed, better armed, and infinitely better mounted; for the rebels are fully half mounted on mules, and their animals get but two rations of forage per week, while ours get seven.” With a better cause, he held, “we ought to be invincible, and by God, sir, we shall be!”7

No more surprises, Hooker ordered—and he granted Stoneman full arrest, cashiering, and execution powers. Perhaps worst of all, he threatened to take command of the cavalry himself.

All of Hooker’s personal flaws were thus revealed. The Cavalry Corps’s problems were in leadership, and not in the personnel, horses, equipment, etc. Hooker, however, was not the solution and neither were his other command selections, excepting Buford and Gregg. At this point, Stoneman and company had commanded for a little over one month. The question facing the commanding general was whether he should have worked with these commanders or replaced them and, if the latter, with whom? The clock was working against a quick fix.

As the month progressed, Hooker received continual reminders of lingering problems. On March 20, Col. Charles Candy of the 66th Ohio, stationed at Dumfries, reported that his scout, Clifford, had witnessed enemy rampaging, “pressing men into their service, and driving good Union families from their homes.” Candy asked why no cavalry were deployed there, even promising them food and fodder.

A few days later, on March 29, Hooker received the unwelcome news that Confederate cavalry had again raided far above the Rappahannock. At noon that day, five miles above Dumfries, 100 Confederate cavalrymen attacked Candy’s cavalry pickets. Candy reported that eight of the patrol were missing and presumed captured. Details remained sparse: the skirmish occurred on the Telegraph Road, and a deserter from the 5th Virginia Cavalry revealed the Confederates had come from the Rapidan. Major E. M. Pope of the 8th New York Cavalry, commanding the pickets, described the “disaster” as of 6:30 p.m. that evening. He had ordered Capt. C. D. Follett to send out scouts, but Follett found only six men returned after his lieutenant and 11 additional troopers were taken.8

Averell’s Revenge: The Kelly’s Ford Raid

Although the Federal cavalry’s overall performance remained uneven and the commanding general’s frustrations remained high, there were important signs of improvement.

Fitz Lee’s late-February Hartwood Church raid had virtually invited retaliation when Lee taunted his old friend, William Averell. Perhaps motivated by their lackluster Hartwood performance, Fitz Lee’s note, Joe Hooker’s goading, or all three, some life surfaced in the cavalry corps. On March 16, “pursuant to instructions” from Butterfield, Averell led his 2nd Division—a force of more than 3,000 cavalrymen and six artillery pieces—out from the army’s defensive perimeter. They headed for Culpeper Court House, where he hoped to surprise Fitz Lee’s cavalry. Averell’s orders were “to attack and rout or destroy him.”9

Battle of Kelly’s Ford (March 17, 1863). At 4:00 a.m. on March 17, Brig. Gen. William Averell crossed the Rappahannock with 1,800 men, expecting the aggressive Fitzhugh Lee to seek him out for battle. Lee obliged, and after a back-and-forth series of charges and countercharges, the Rebels withdrew three-quarters of a mile. Averell rode after them, and the two sides settled into an extended battle that lasted until 5:30 p.m. Averell withdrew and filed an enthusiastic report. “[O]ur cavalry has been brought to feel their superiority in battle,” he asserted. “They have learned the value of discipline and the use of their arms.”

En route, Averell was informed that some 250 to as many as 1,000 Confederates and one artillery piece were operating north of Brentsville. In response, he requested a cavalry regiment be sent toward Catlett’s Station and picket posts be established covering flank approaches from Warrenton, Greenwich, and Brentsville. Inexplicably, this reasonable request was refused, so Averell detached 900 men to secure his flank and turned southwest.

A second concern had to be addressed: Averell’s artillery battery had marched farther than the rest of his command—some 32 miles from Aquia Creek to Morrisville—and arrived in poor condition at 11:00 p.m. on the 16th. It required rest and repairs.

Averell had sent forward detachments about 2-4 hours ahead of his main body to check for Rebel scouts and secure approaches to the Rappahannock fords. From Mount Holly Church, Federal scouts observed enemy campfires between Ely’s and Kelly’s Fords and heard drums beating retreat and tattoo at Rappahannock Station. Confederate cavalry were also reported.

In related action, at Morrisville, Lt. Col. G. S. Curtis of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry was placed in command of all pickets above the Rappahannock. He directed Lt. Col. Doster of the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry to take 290 men and drive the Rebel pickets toward Rappahannock Station; return to Bealeton; and then post pickets. They encountered only “a small party of guerrillas at Bealeton Station.”10

At 4:00 a.m. on March 17, Averell’s force crossed the Rappahannock with 1,810 men under Col. Alfred N. Duffie, Col. John B. McIntosh and Capt. Marcus A. Reno (1st, 2nd and Reserve Brigades, respectively). Accompanied by the 6th Independent New York Battery, commanded by Lt. George Browne Jr., Averell opted to cross at Kelly’s Ford, which he knew best. It took them four hours to reach the ford.11 There, they found abatis—cut trees overlapped and pointed in the enemy’s direction—blocking both banks and “80 sharpshooters” covering the obstacles.

McIntosh dispatched his “ax-men” under Lt. Gillmore of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry to cut away the obstacles, a pointless, time-consuming effort. Afterward, two dismounted squadrons, protected by an empty mill-race near the ford tried three times in vain to dislodge the Rebels. Averell sent other troops to cross a quarter-mile below Kelly’s, but the river was too deep to cross and banks too steep to climb.

In desperation, Lt. Simeon A. Brown and 20 troopers of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry made another attempt at the ford. This time they negotiated the abatis and captured 25 Confederates. On the Federal side, ten men and 15 horses were casualties thus far.

Averell didn’t use his artillery lest he alert the enemy “while astride the stream.” Once across, he assumed a defensive posture on the far shore—an odd decision on the surface considering his objective was Culpeper Court House. Personally knowing Fitz Lee’s character and position, though, Averell expected to be rapidly challenged. His defensive disposition gave him time to water his horses and rest.

When Lee’s reaction did not materialize, Averell moved ahead, with Duffie’s men leading. A quarter mile forward, they finally spotted the expected Confederate advance. Averell maneuvered the 4th New York to the right and 4th Pennsylvania to the left; ordered both to engage by carbine; and made a section of artillery ready to engage. Averell positioned three of Reno’s squadrons in reserve behind McIntosh on the far right. A fourth squadron filled a gap between the 4th Pennsylvania and 4th New York.

Those two regiments initially faltered, but Averell and his staff restored order as two or three enemy columns approached at a trot to his right. There, McIntosh and Gregg attacked. Duffie defended against a Rebel assault with the 1st Rhode Island, 4th Pennsylvania, and 6th Ohio—with the 4th New York in reserve—on Averell’s left. Averell took Reno’s three reserve squadrons at a gallop to support Duffie. Two squadrons of the 5th U. S. Cavalry and the 3rd Pennsylvania were committed and drove back the Confederates. Due to mud and distance, however, the charge could not bag the withdrawing 300-500 Confederates.

For 30 minutes, Averell regrouped, recovered stragglers, and reset his defenses. Anchored on the road to his left by Lt. Sweatman and his 5th Cavalry Regulars, Averell advanced three-quarters of a mile “from the field we had won.” Behind the fire of two guns, the Confederates counterattacked both flanks. The Union advance continued on the right, but the Confederates penetrated on the left. Controlled by lieutenants Browne and Rumsey (Averell’s aide), the left held and the advance continued, though slowed by Confederate fires set in the field, which Averell’s men beat out with overcoats.

From entrenchments, the Confederates continued fighting with three guns—two 10-pounder Parrots and one 6-pounder. The Rebels successfully coordinated artillery fires with their cavalry advance. The Federals held them off and advanced on the right before encountering infantry positions. Their own artillery, suffering severe technical and supply problems, was out of action and unable to support them. Averell, informed that Southern infantry was on his flank, assumed they planned to encircle him. At 5:30 p.m. he “deemed it proper to withdraw” across the Rappahannock.

On the far bank, Averell tallied Union casualties at 78 killed, wounded, and missing, and guessed that the enemy may have suffered as many as 200 casualties. That number later came in at 133 men and 170 horses of Lee’s Brigade—roughly equivalent to Union losses at Hartwood.12

Averell’s over-enthusiasm was evident:

The principal result achieved by this expedition has been that our cavalry has been brought to feel their superiority in battle; they have learned the value of discipline and the use of their arms. At the first view, I must confess that two regiments wavered, but they did not lose their senses, and a few energetic remarks brought them to a sense of their duty. After that the feeling became stronger throughout the day that it was our fight, and that the maneuvers were performed with a precision which the enemy did not fail to observe.13

Averell pronounced a “universal desire of the officers and men of my division to meet the enemy again as soon as possible.”

Unreported, Averell left a retaliatory note for Fitz Lee in response to the note Lee left during his Hartwood Raid. In that first missive, Lee told his Yankee friend he rode a better horse, to visit sometime, and bring coffee; Averell’s response announced his arrival and a deposit of coffee.

The raid improved the cavalry corps’s morale. Butterfield was impressed, too, but Hooker less so. Typically, he had disapproved Averell’s request for an additional regiment for flank security and then criticized him for leaving a third of his men behind. Hooker also felt that Averell could and should have done more.

Averell, given the state of the cavalry, felt he took an important step toward respectability. The raid certainly excited the secretary of war. “I congratulate you upon the success of General Averell’s expedition,” Stanton wrote to Hooker. “It is good for the first lick. You have drawn the first blood, and I hope now soon to see ‘the boys up and at them.’”14

To that point, Averell’s raid on Kelly’s Ford was the war’s largest cavalry-on-cavalry fight. But universal joy in Yankeedom exposed the Federals’ deep-seated inferiority. After all, this was in the war’s twenty-third month. Averell’s force outnumbered Fitz Lee’s brigade; and they only penetrated at best three miles into the Confederate outer defenses. On the other hand, as Stanton stated, this was an important “first lick” and first steps are seldom decisive. Most importantly, the raid demonstrated the Federals could raid, surprise Stuart’s cavalry, and engage their opponents in cavalry battle.

Of equal interest, this raid shocked the Confederates, necessitating rare spin-control on their side. Simply put, the Yankees weren’t considered capable of such action. Like many raids, Kelly’s Ford’s impact was more psychologically than militarily successful. Word was served on Stuart’s men: Federal troopers could no longer be assumed to be huddled close to defensive perimeters and campfires.

An unintended consequence of the raid was the death of Confederate Maj. John Pelham. The boy-hero of Stuart’s Horse Artillery at Fredericksburg and elsewhere, Pelham had spontaneously joined in the cavalry fight and fell mortally wounded. Boy-heroes, especially well-publicized ones, aided home front morale; but, their deaths had a contrary, often tenfold impact. “The Gallant Pelham’s” death delivered a body-blow to Stuart, his cavalry, and the South. The loss, wrote Stuart, “has thrown a shadow of gloom over us not soon to pass away.”15

The death of Maj. John Pelham during a fight with Federal cavalry was of little tactical importance, but the death of the Southern war hero highlighted an important lesson the Federals were trying to make: the days of uncontested Confederate cavalry dominance were over. LOC

Other Shuffles

The cavalry corps was not the only unit in the army facing trouble. March 18 brought a death-knell for Thaddeus Lowe’s Aeronautics Corps. Chief Quartermaster Rufus Ingalls received a letter from inventor “B. England, of 1724 Rittenhouse Street in Philadelphia” that under-bid and over-promised Lowe’s operations. Ingalls bucked the letter to Hooker’s headquarters, which showed it to an irate Lowe. He penned a lengthy rebuttal—which, of course, became public and led to testimony by disgruntled former Lowe employee Jacob C. Freno, attacking Lowe personally. Such ruminations consumed the balloon corps’ time. For Hooker, already unimpressed by the aeronauts, this was more reason for skepticism.16

Another figure lacking the commander’s confidence, Brig. Gen. Daniel P. Woodbury, commander of the army’s engineer brigade, met with grief, too. Woodbury’s career had not survived the late pontoon debacle at Fredericksburg. He received no formal blame, but was reassigned to command the District of Key West and Tortugas in the Department of the Gulf (Dry Tortugas being unofficially dubbed “America’s Devil’s Island”). Within 18 months, he would be dead from yellow fever. Brigadier General H. W. Benham filled Woodbury’s position with the Army of the Potomac.

More shuffling occurred. On March 20, Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel was reassigned from the XI Corps to the Washington Defenses. Stahel would come back to the Army of the Potomac a few months later as part of the cavalry corps, but Pleasanton would have him removed. Stahel would serve out the rest of the war in various cavalry capacities, eventually earning the Medal of Honor for actions at Piedmont.

Hooker would not name Stahel’s replacement until March 31. Special Order No. 87 assigned Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard to temporary command of the XI Corps. The same order placed Brig. Gen. John Gibbon under General Couch’s command in the II Corps to take Howard’s place.17 “General Howard is assigned to the command of the Eleventh Corps, formerly Sigel’s, and goes tomorrow, taking his two aides, Lieutenants Howard and Stinson,” II Corps Surgeon Frank Dyer noted prophetically. “We all regret his leaving very much and fear that the Eleventh Corps may not enhance his reputation. General Gibbon comes here.”18

The previous day, after two months commanding the army, Hooker added eight more officers to his staff in General Order No. 32: Brig. Gen. G. K. Warren, chief engineer staff officer; Col. E. Schriver, inspector-general; Lt. Col. N. H. Davis, assistant inspector-general; E. R. Platt, Capt., 2nd U. S. Artillery, judge-advocate-general; Maj. S. F. Barstow, assistant adjutant-general; Col. George H. Sharpe, 120th New York, deputy provost-marshal-general; Capt. Ulric Dahlgren, aide-de-camp; and Capt. Charles E. Cadwalader, 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, acting aide-de-camp.

Two months into his tenure, Hooker continued to render additional efficiencies in logistics, too. On March 19, headquarters announced, in General Order No. 77, that some pack-saddles arrived and were to be issued to the army corps roughly equally except for VI Corps, which got more than any corps. Inexplicably, II Corps received none. Perhaps they had been previously issued. Pack-saddles would be used—two each—by regiments to carry officers’ shelter-tents and rations. The rest would be used to carry 2-3 ammunition boxes per horse, depending on relative horse strength. This was a revolutionary innovation, and the general order specified daily loading and unloading drills. Animals detailed to this “ammunition-pack” would be drawn from the ammunition train (and wagons without horses were to be turned-in). This promised a major improvement in mobile resupply of infantry ammunition, allowing the pack animals to move smoothly with the units into action. However, substitution of unpredictable mules—obstinate, but available and sure-footed—initially threatened this reform. The contrary creatures could foil the best logistician’s intentions. But, perhaps analogous to the army itself, mules could be re-trained.19

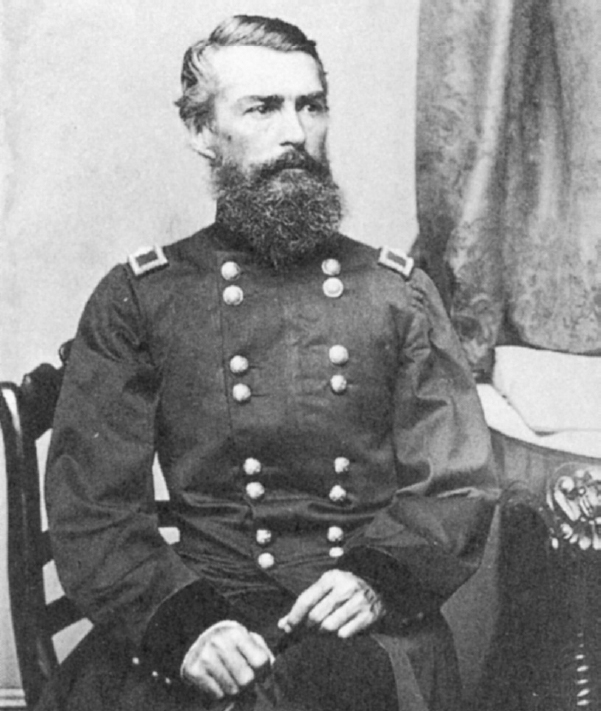

Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, called “Old Prayer Book” by some of his subordinates because of his strict religious faith, seemed an unlikely choice to lead the XI Corps. Hooker made the choice, in part, because he intensely disliked the other potential candidate, Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz. “I would consider the services of an entire corps as entirely lost to this army were it [the XI Corps] to fall into the hands of Maj. Gen. Schurz,” Hooker contended. LOC

Another important reform of the army’s ordnance service took place on March 25 under G. O. No. 30. Whether Hooker aimed at readiness for a move or firming-up ammunition- and arms-handling procedures, the forward thinking order required basic loads of ammunition be kept on hand: “Infantry: 140 rounds with that in the cartridge boxes [40 rounds]; Cavalry: 100 rounds for carbine and 40 rounds for pistol with that in the cartridge boxes; and Artillery: 250 rounds with that in the ammunition chest.” The 20 rounds previously carried by infantrymen in their knapsacks would be expended in due course, perhaps through marksmanship training, but not replenished. Thereafter, those rounds would be issued on the eve of battle and carried in pockets. After covering the minutiae, the order fixed the main responsibilities on division ordnance officers, who were relieved from other duties to report to division headquarters.

Another valuable innovation resulted: reserve ammunition wagons would be marked with corps and division symbols, and infantry, cavalry, or artillery ammunition wagons would be “color-coded”—representing the branches with horizontal blue, yellow, or red stripes respectively. The army’s main ammunition depot would be marked by a crimson flag marked “Ordnance Depot, U.S.A.” On the march, when brigades were dispersed, division ordnance officers could detach stores to brigades. Care would be given in battle to deploying ammunition trains to facilitate resupply. Divisions would draw on the army ordnance depot for resupply munitions. Unserviceable and condemned ammunition would be turned in through regimental quartermasters. Division ordnance officers would have a staff with an acting ordnance noncommissioned officer and a clerk. Extra-duty men on ordnance duty would report to him and be kept on his extra-duty rolls. Now, clearly marked mobile resupply ammunition wagons could be moved closer to the units and pack trains.20

Another reform came from up the tracks in Washington. Railroader Herman Haupt sent Hooker a copy of instructions he had cut to his chief engineer, A. Anderson. “You will take measures to have everything in readiness to meet the wishes and second the movements of the commander of the Army of the Potomac,” he wrote, “sparing no labor or necessary expense to secure the most effective action when called upon, and to provide the materials and men necessary for the purpose.” Significantly, Haupt ordered Anderson to assemble the necessary force to support movement, apply to the army commander for details of soldiers, and gain support from the army’s chief quartermaster for transportation of all kinds and forage for his animals. “When active forward operations are resumed,” Haupt added, “the all-important object will be to secure the reconstruction of [rail] roads and bridges and the reopening of communications in the shortest possible time.” Haupt advised Anderson to have all the required men assembled and moved forward; but, to use them constructing or repairing existing lines or assisting in building blockhouses for protection of rail bridges. Oxen, also needed for an advance, would be gainfully employed hauling ties and wood.21

Haupt’s order is instructive as another indicator of a contemplated offensive, which was exactly what Henry Halleck had in mind. “Old Brains” wrote to Hooker on March 27. “Dispatches from Generals Dix, Foster, and Hunter, and from the west, indicate that the rebel troops formerly under Lee are now much scattered for supplies, and for operations elsewhere,” he shared. “It would seem, under these circumstances, advisable that a blow be struck by the Army of the Potomac as early as practicable. It is believed that during the next few days several conflicts will take place, both south and west, which may attract the enemy’s attention particularly to those points.” Halleck’s suggestion that the army could launch an offensive on the basis of his message—even if it originated from Lincoln or Stanton—betrays his feeble strategic understanding. While Hooker was making real progress in every aspect of his army, the general-in-chief of all the armies was puttering.22

One of the most important reforms Hooker made came on March 21 in a circular of significant military-historic importance:

For the purpose of ready recognition of corps and divisions in this army, and to prevent injustice by reports of straggling and misconduct through mistake as to its organization, the chief quartermaster will furnish without delay the following badges, to be worn by the officers and enlisted men of all the regiments of the various corps mentioned. They will be securely fastened upon the center of the top of the cap. Inspecting officers will at all inspections see that these badges will be worn as designated:

First Corps, a sphere—First Division, red; Second, white; Third, blue.

Second Corps, trefoil—First Division, red; Second, white; Third, blue.

Third Corps, lozenge—First Division, red; Second, white; Third, blue.

Fifth Corps, Maltese cross—First Division, red; Second, white; Third, blue.

Sixth Corps, cross—First Division, red; Second, white; Third, blue. (Light Division, green.)

Eleventh Corps, crescent—First Division, red; Second, white; Third, blue.

Twelfth Corps, star—First Division, red; Second, white; Third, blue.

The sizes and colors will be according to pattern.

Railroads proved to be the great lifeline of the Army of the Potomac. It fell to Brig. Gen. Herman Haupt to keep them running effectively. LOC

Corps insignia were first implemented as a way to facilitate organization and order, but they quickly became sources of pride for the men. NPS

The circular originated corps/division badges and was the Army’s first systematic use of them. Unit pride and morale improvement skyrocketed. The new symbols adorned every soldier and wagon. Fancier versions of corps badges, some jeweler-quality, appeared for sale in New York and Philadelphia. Later, the badges identified the wearer and linked him to his division’s or corps’ fortunes or misfortunes.23

The corps/division badges offered another opportunity in the endless efforts to count the numbers of men in the army. In an effort to determine how many badges the quartermaster’s department needed, the army on March 21 tallied the following:

First Corps: 15,510

Second Corps: 15,337

Third Corps: 17,438

Fifth Corps: 15,467

Sixth Corps: 22,076

Eleventh Corps: 12,880

Twelfth Corps: 11,933

Cavalry: 11,937

Total: 122,578

Total, without cavalry, 110,641.24

Ten days later on March 31, as part of its routine end-of-the-month reporting, the army took yet another opportunity to reckon its own strength. Headquarters strengths came in as follows: General and staff, 66 officers and two enlisted men; Provost guard, 159 officers and 2,345 enlisted men; Regular engineer battalion, two officers and 351 enlisted men; Volunteer engineer brigade, 28 officers and 544 enlisted men; and Signal Corps troops, 22 officers and 77 enlisted men. The Artillery reserve reported 53 officers and 1,362 enlisted men. The corps reported as follows:

Organization, Commander / Officers / Enlisted Men

First Corps, Maj. Gen. J. F. Reynolds / 972 / 15,586

Second Corps, Maj. Gen. D. N. Couch / 1,013 / 15,893

Third Corps, Maj. Gen. D. E. Sickles / 1,004 / 17,591

Fifth Corps, Maj. Gen. G. G. Meade / 845 / 15,786

Sixth Corps, Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick / 1,204 / 22,384

Eleventh Corps, Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz / 643 / 13,224

Twelfth Corps, Maj. Gen. H. W. Slocum / 711 / 12,452

Cavalry Corps, Brig. Gen. G. Stoneman / 594 / 11,811

Totals (Including HQs and Arty) / 7,316 / 129,408

Present for Duty: 136,94925

Rules of War?

Not all of the army’s reforms worked as well as the corps/division badges. New rules for paroles and exchanges, in contrast, were simply bizarre. On March 17, Hooker—despite trying to kill Robert E. Lee’s nephew that day—sent him a polite communiqué. Adhering to orders and perhaps feeling that Lee’s 32-year U. S. Army tenure had endeared him to War Department orders, Hooker enclosed a copy of No. 49, dated February 28. Paroles were to be written in duplicate with correct names and ranks; failing to do so invalidated parole. Only commissioned officers could parole themselves or their commands. Paroles on battlefields—either entire troop bodies or mass prisoner dismissals—were forbidden. “An officer who gives a parole for himself or his command on the battle-field is deemed a deserter and will be punished accordingly,” Hooker explained. Officers could only pledge paroles individually, and no non-commissioned officer or enlisted man could give his parole except through an officer. No prisoner of war could be compelled to pledge his parole.26

Laughable even then, a prisoner whose parole process was later found invalid by his government was supposed to turn himself over to enemy captivity. No one could pledge to never take arms against his adversary or allies. Parole pledging was voluntary, but not binding. “Paroles not authorized by the common law of war” were forbidden and pledging unauthorized paroles was punishable. The final paragraph required the order to be sent by all army commanders to current opponents. How such nonsense survived into even the nineteenth century would be worth separate study. No doubt many hours of whale oil were burnt plumbing the depths of “the common law of war.” What any of this foolishness meant to the general, field or company officer, or common soldier must be left to dubious conjecture.27

“Everyone Has Something to Do”

Even as Averell and his cavalry were making a show of themselves to the west at Kelly’s Ford, the Irish Brigade observed March 17 in much lighter fashion—proving that life was not perpetually bleak during the “Valley Forge.” St. Patrick’s Day offered the Irishmen the chance to relieve the tedium with steeplechase horse racing and sack races It whetted their appetites for food and drink, too. Celebratory fare included “thirty-five hams, and a side of an ox roasted; an entire pig stuffed with boiled turkeys; an unlimited number of chickens, ducks and small game.” Ample drinking materials included “eight caskets of champagne, ten gallons of rum, and twenty-two of whiskey”—all to satisfy the hunger and slake the thirst of the lusty Hibernians.28

“General Meagher and staff celebrated by giving a steeplechase on the parade ground of the division,” recalled adjutant Josiah Favill of the 57th New York Infantry. “A course was carefully laid out, ditches dug, hurdles erected, and valuable prizes offered to the contestants. The conditions were simply that none but the commissioned officers of the division could ride, which was sufficiently liberal.” A crowd of officers participated, while “Meagher, glorious in fancy undress uniform liberally covered with gold braid,” entertained generals and lady friends. Among the attendees in Hooker’s retinue was Princess Agnes Salm-Salm, the wife of Prince Felix, the colonel of the 8th New York Infantry; Favill described her as “a beautiful and fearless horse woman.”29

The race, with only a few serious falls, was deemed a success. Infantry guards maintained decorum, but festivities lasted into the night, and things finally teetered toward chaos when Meagher and his brigade surgeon challenged each other to mortal combat. Matters assumed a threatening aspect. The following morning, however, when alcoholic effects had subsided, the surgeon apologized and peace resumed. To the surprise and disappointment of the brigade, Hooker struck a surprising party-pooper tone that day. “All fast riding and fast movements of wagons through the army were to cease immediately,” he said in General Order No. 28. Provost marshals and guards were to enforce the order.30

Nonetheless, the St. Patrick’s Day festivities inspired non-Irish Pennsylvanians, Michiganders, New Yorkers, Indianans, and Mainers to new celebratory heights. On March 28, the men of Brig. Gen. David Bell Birney’s III Corps division extended the limits of frivolity at “Bell Air” with horse racing, greased pole climbing, and sack races. Entertainment also included an “Ethiopian Concert”—a minstrel show. The division erected a 120-by-60 foot reviewing stand, and “real women, be-silked, be-furred, and bonneted” attended the frolics. Reportedly present were Maj. Gen. Hooker, Pennsylvania Governor Curtin, unnamed “distinguished statesmen,” and “officers from the different corps.” One observer noted that “General Sickles [the murderer] of Key had his lady there.”31

Peak soldier morale was achieved when companies within a regiment or regiments within a brigade vied with one another to prove or demonstrate themselves best. Within elite units, the goal was to be “the best of the best” without greatly diminishing other units. Competition, unless unhealthy or excessive, defaulted to unit pride, an “intangible” crucial to combat readiness. Of course, pitting one’s mettle against the enemy provided the truest test, but for most men in the Army of the Potomac during the “Valley Forge,” the enemy was seldom encountered on a day-to-day basis. Thus, standing well among fellow units reflected a competitive edge.

Soldier “Marker” exemplified this when he described the rivalry between the 16th and 27th New York regiments in a letter that appeared in the March 26, 1863 edition of the Rochester Union & Advertiser. “The 16th New York,” he began, “whose fame is widespread as that of the 27th, and belonging to the same brigade, hails from St. Lawrence county, the home of Preston King, and the hot-bed of Republicanism. Suffice it to say,” he continued,” two years’ service has changed the radical sentiments of its warrior representatives. From the first Bull Run to the present day it has figured in nearly every conflict registered on the banner of the Army of the Potomac and has invariably sustained a fighting reputation. Colonel, now Major General Davies, was the first commander, a strict disciplinarian, and a military man in every sense of the word.” Under Slocum and Davies as the brigade commanders, great jealousy existed between the 27th and the 16th, “as both were worshipped, and with good cause, in the eyes of their own regiment. Since then, the feeling has gradually worn away, leaving only a generous spirit of rivalry between the two regiments.”32

Morale was also lifted throughout the army by myriad food boxes shipped to soldiers “by loving hands”—a sentiment common at the time. Packages produced universally happy results; however, they also experienced a wide range of success on the tricky path from hearth to hut. Inconsistent Northern mail services, shipper carelessness, corruption by officers and clerks, and physical dangers all conspired to keep packages from waiting soldiers. When one arrived intact, celebrations erupted among recipients and friends (always numerous at that point). When the system failed, results were predictable. An incident in the 19th Massachusetts Infantry was recalled in 1899 with gallows humor: “Some of the boxes had been a long time on the road, and when they arrived the contents were in uncertain condition. It was hard to tell the tobacco from the mince pie.” One of the packages had been expected by the regimental adjutant. The officers gathered to see him open it. “The cover was removed and the smell was not quite equal to the arbutus, but we hoped it was only the top. Another box was found inside containing what was once a turkey, but was now a large lump of blue mould. Nothing in the box was eatable.” The officers held council and concluded the turkey needed decent burial. The remains “lay in state,” a wake was held, and a solemn procession conveyed the body to the open grave. “Negro servants” served as drum major and pall-bearers. The quartermaster, with the carbine reversed, was the firing party; and a chaplain pro tempore was appointed. At graveside, words and poetry sent the turkey to eternity before returning to camp to mourn “for the spirits that had departed.”33

Colonel Joseph Snider of the 7th Virginia (Union) Infantry reflected on spiritual matters of a more sincere type. “I try to remember God’s holy day, though speaking in general terms, a soldier knows no Sunday,” he wrote on Sunday, March 15. “And now, while I am writing, the sound of martial music is heard in many directions—and men are marching off to do duty, as guards and pickets for our camp—This would seem verry strange out in Morgantown—but such is the soldier’s duty—and such is the necessities of war.”34

Snider wrote with a fondness for the routine he saw around him. “You would be interested, in seeing the smoke ascending from thousands of little log huts—and promenading some of our nicest streets. Our Towns are regularly laid out—and hence we have alleys, Main streets, front streets, broad streets and our Towns have no hotels, no mattresses. No feather beds—a board with a blanket constitutes the beds. There is one particular difference in our towns and others in the country—we have no loafers here—everyone has something to do—and has got to do it.”35

Sergeant Thomas White Stephens of the 20th Indiana Infantry made March diary entries that showed how busy the typical soldier was.36 On the first through third, he performed guard, caught up on reading, listened to a good sermon at the 10th Pennsylvania’s camp, and noted reconnaissance balloon ups and downs. On the third, the regiment was reassigned to J. H. Hobart Ward’s 2nd Brigade; on the fourth, they moved their camp 4-5 miles to near Potomac Creek Railroad Bridge. For several days amid more plentiful wood, they built shelters and settled in. On the eleventh, he favorably noted three comrades’ returns from hospital and a dress parade—off-set by some miscreant stealing a set of his washed drawers. Dysentery returned on the twelfth and thirteenth, but he persevered through letter writing, drawing clothing (drawers at .50 cents, and leggings at .75 cents), a haircut from his brother, and modest purchases of tea at the sutler’s.

On March 14, Stephens noted increased spirit: “An order, from Gen. Birney was read this evening on dress parade, that Regimental Commanders prepare and send to headquarters a report of all soldiers, who have distinguished themselves on the battlefield, such soldiers to receive a silver cross (medal of valor), to be worn over the ‘Red patch’ on the left breast.” Another order directed that no soldier under arrest or who is reported for straggling could wear the “‘Red Patch.’—Only those, who have been in battle, are entitled to wear it.”37

On March 15, Stephens’s health improved: “Thank God for his goodness and mercy to me. O that I love him, more, who is all love, love.” He read his Bible and “Pollok’s Course of Time.” On the 16th, he read “‘Harper’s Weekly’, &c.” and listened to an Indiana Senate speech read by a Captain Reed. Duty ended with company inspection. Noting heavy cannonading up-river on the seventeenth, Stephens was on picket duty on the eighteenth, reached by a march of 8 miles. He had “precious seasons” of “secret prayer,” proclaiming them the “sweetest, best moments of my life, thus spent!” On picket some 25-30 Confederate prisoners were taken. Presumably in picket reserve on March 19 and 20, he read and prayed: “In bowing in secret prayer, today, felt the presence of One I love best, my nearest, best friend. O how sweet thus to commune with my Saviour: with Jesus my Redeemer.”38

On March 20, Stephens “took a very bad cold, have a cough,” but managed prayer and enjoyed a daily ration of beef and soft bread. They returned to camp on muddy roads on the twenty-first. Tired and sick, a good night’s rest made him feel better on March 22 (Sunday). His spirits were enlivened by a new cap (.65 cents) and a box from home; the box contained much needed pain-killer, six pounds of butter, tea, a few cakes, box of cayenne pepper, preserves, and arithmetic and grammar books. Also received were: a “Methodist discipline,” handkerchiefs, suspenders and dried huckleberries. Stephens gushed, “God bless our kind friends at home.” After evening inspection, he turned-in with his Harper’s Weekly. On the twenty-third he sent a “haversack of things home” with a friend.

His cold persisted. Remaining in his tent, Stephens “used pain-killer pretty freely” before evening dress parade. On the forenoon of March 24, he was subjected to “very close inspection” by one of General Ward’s aides. His sickness persisted, so he continued applying the pain-killer. Either because or in spite of it, he felt God’s peace and love. On the twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth, Stephens had a headache (he made no connection with the “pain-killer”). He read his Bible and “Pollok’s,” rating both highly. He described a review three miles away on March 26 for generals Sickles and Birney and Pennsylvania’s Governor Curtin. They also received sad news of Maj. Gen. Sumner’s death in Syracuse. On the twenty-seventh, Stephens recorded a “general row in the 99 Pa. Regt.” after evening roll call in which several were injured. He cleaned his weapon on March 28 and read. The twenty-ninth and thirtieth included company inspection, feeling poorly, company drill, and a noon review for Indiana’s Governor Morton and generals Ward and Meredith. Whether for its brevity or content, the troops repaid the governor’s short speech with three cheers. Stephens cleaned his weapon again and awoke on March 31 to snow. Perhaps favorably, the snow melted quickly and he returned to reading his Bible and Methodist discipline, despite continued stomach sickness.39

Henry Butler of the 16th Maine Infantry Regiment described another common activity. “We have been drilling the skirmish drill,” he said. “The way we have to do is to practice loading on our backs and then turn on our bellies and fire. Tomorrow morning I have got to go out on picket and stay three days.”40

“L. A. V.,” a soldier with the 15th New Jersey, wrote positively to his hometown newspaper about the twice-daily company and battalion drills, deemed “necessary for our efficiency in the field as well as our health.” “The army is fine spirits,” he added, “and though disease has made sad havoc in our ranks, we still retain in memory the duty we owe our beloved country, and shall make it manifest at the proper time. Copperheads at the North hold your peace, and we will make peace.”41

This overall sense of purpose, coupled with Hooker’s reforms, did so much for morale that even the grousing took a lighter tone. “Our Co. (Co. F) is acting as Provost Guard to the 3rd Div. 1st Army Corps—Cap’t. Mitchell is Pro[vost] Marshal, Gen. Doubleday is commanding the 3rd Div,” wrote Lt. William Oren Blodget of the 151st Pennsylvania Infantry on March 21 from their camp near Belle Plain. Blodget sardonically proclaimed Doubleday “deficient considerably” as a commander because he neither drank whiskey, left his command, or refused to fight. That the general refrained from keeping a mistress also struck Blodget as exceptional. He deemed drunkenness and profanity desirable in privates as the government could waste resources confiscating their whiskey and passing out religious tracts. He ridiculed uneven justice for officers and enlisted men; the weather; and the antiwar movement—hoping for another 200,000 men in the field to finish the war. “Every day increases the disparity of strength and will continue to do so whether we are victorious or not,” Blodget concluded. “All we have to do is to call out our men.”42

A soldier in the 140th Pennsylvania was waiting for that call. “The roads are drying fast, but I can’t see anything to indicate a move,” he admitted. “Old Hooker hasn’t told me when it is going to be, for he does everything sly and we can’t tell much about it. He doesn’t do like Burnside did, let everyone know his moves, and I think it is the best way.”

That didn’t stop the Keystoner from wondering: “All the papers say the rebs are starving and their pickets say they have been on half rations for a month … [and] they are falling back to Richmond,” he continued, “but they appear plenty around here yet. But when Old Hooker is ready we will know how many there is of them and I don’t think that will be long… There is a much better feeling among the men and they are all willing to try it again. If the rebs lose Fredericksburg they can never stop us without more men, for they can never get as good a position this side of Richmond.”43

Corporal Amory Allen of the 14th Connecticut Infantry echoed similar thoughts on March 24. “We expect to move over the river soon and some where else,” he wrote. “Old Hooker will not keep us idle long after the mud is dried up for he is an old fighter and the rebels are very anxious to know where he is about to strike the blow.” In his letter, Allen revealed his recent promotion to first corporal. “[I] expect to be one of the colour guards and if I do that will excuse me from picket duty and many other duties,” he pointed out. Expressing pride in such dangerous duty as color guard demonstrated an important increase in morale.44

Captain Frank Lindley Lemont of the 5th Maine Infantry wrote on March 26 with his prediction that the army would move within two weeks. “I don’t know where we shall make a strike, or when, but you may rest assured that Hooker’s boys will leave their mark whenever and wherever he say the word,” he vowed. “There is a good deal of fight in the Army of the Potomac and in the next battle they will show of what mettle they are made. Joe Hooker is a fighting man and so must every man be under him. I don’t know as we shall succeed in the next battle, but we intend to and we are under a [general] who will press forward as long as he has a man who can walk without crutches.”45

Looking ahead often provoked anxiety, especially in light of past engagements. Marye’s Heights, standing beyond the town on the far side of the river, offered a clear reminder of those travails to anyone who happened to forget. Those who had “seen the elephant” in battle intuitively understood that they were all, to use a later infantryman’s phrase, “fugitives from the law of averages.”

As a result, religion continued its surge through the camps. John Cole, a general agent for the United States Christian Commission (U.S.C.C.), noted the vigor with which many soldiers attended to their spiritual lives, and it invigorated him. “I am well with the exception of a cold and am enjoying my work greatly,” he reported early in the month. “Indeed no money could tempt me to leave it, we are being prospered wonderfully, I can almost say that there is a revival at this place, we had a meeting tonight about 200 persons present and a deep interest was manifest, we have a prayer meeting every night and they are well attended, one night every person came to his feet as desiring the prayers of Christians.”

Bibles and tracts had been distributed in mind-numbing numbers. Cole had another 80,000 Bibles—a grant from the American Bible Society—about to be distributed by 20 delegates (10 from New England) at four or five “stations.” “We find every where a great desire to receive Testaments & books,” Cole added, “and we every where meet the most marked consideration from officers and men.” He singled out Treasury Secretary Chase and Maj. Gen. Howard for their significant assistance. His report ended: “I trust God will bless us in our efforts. I feel that we need the prayers of the Christian church every where that our labors may be crowned with success.”46

The U.S.C.C. had been looking after the spiritual—and, increasingly, the material—comforts of these men for over a year. Soldier’s aid societies in Northern communities and the U. S. Sanitary Commission added additional food, clothing, and other supplies. Citizens collected, made, or sometimes purchased and forwarded “donations” to the soldiers. For example, from Falmouth, Surgeon J. Wilson Wishart of the 140th Pennsylvania Infantry thanked Miss Helen Lee (a relation of Federal Colonel Lee) on March 24: “It gives me great pleasure to acknowledge the receipt of a number of copies of the Soldier’s Hymn Book and also some Tracts, the gifts of yourself.”47

Civilian volunteers pretty much came and went at will—a freedom of action denied every general, officer, and enlisted soldier. Cole was among those who could do so. He’d spent much of March in the camps but returned to Philadelphia later in the month to rally more aid. “Here again on a flying visit,” he wrote on March 29. “Start at Midnight for Aquia again. I am very busy arranging the ‘move’ that the newspapers assert to be coming soon. I have now about 35 delegates to look after and feel somewhat anxious as to the turn matters may take. But after all we are in the Lord’s hands and what is best will be done.”48

The U.S.C.C. had six stations by then, Cole explained, “and a glorious work at each.” At Falmouth, they had a large room near the bridge that once connected Falmouth with Fredericksburg. “Here in sight of that beautiful city we hold nightly prayer-meetings with an average attendance of 150 or 200,” he declared. “[A]t another small room where we live, we have a ‘Sunday School.’ We have gathered in the little ‘Secesh’ children who have been deprived of any religious instruction, and there teach them our Sunday School hymns and lessons from the Gospel. The parents are very grateful.” At another station—“Stoneman’s it is called, which is almost in the center of the army”—they held nightly prayer meetings in a long tent or succession of tents. “God has blessed our work here signally,” Cole beamed, “many have been converted, the tent is always crowded to overflowing and every night men are awakened to a sense of their lost condition.” Finally, Cole spoke of “still another station” where delegates assisted every night “the good Mrs. [Ellen] Harris at the ‘Lacy House’ her large room there is crowded every night, she is directly opposite Fredericksburg and in almost talking distance of the Rebs.”49

Curiously, Cole seemed to overlook Stafford’s wartime desolation, but he did end with one other important observation: “The army is in splendid condition and Hooker will fight.”50

Such an assessment no doubt would have pleased President Lincoln, who was thinking that very night on matters of war and peace. On his desk sat a U. S. Senate resolution calling for a national prayer of confession. Lincoln could have handled the paperwork perfunctorily, but instead, on March 30, he chose to make it an expression of abiding faith:

And whereas it is the duty of nations as well as of men, to own their dependence upon the overruling power of God, to confess their sins and transgressions, in humble sorrow, yet with assured hope that genuine repentance will lead to mercy and pardon; and to recognize the sublime truth, announced in the Holy Scriptures and proven by all history, that those nations only are blessed whose God is the Lord.

And, insomuch as we know that, by His divine law, nations like individuals are subjected to punishments and chastisements in this world, may we not justly fear that the awful calamity of civil war, which now desolates the land, may be but a punishment, inflicted upon us, for our presumptuous sins, to the needful end of our national reformation as a whole People? We have been the recipients of the choicest bounties of Heaven. We have been preserved, these many years, in peace and prosperity. We have grown in numbers, wealth and power, as no other nation has ever grown. But we have forgotten God. We have forgotten the gracious hand which preserved us in peace, and multiplied and enriched and strengthened us; and we have vainly imagined, in the deceitfulness of our hearts, that all these blessings were produced by some superior wisdom and virtue of our own. Intoxicated with unbroken success, we have become too self-sufficient to feel the necessity of redeeming and preserving grace, too proud to pray to the God that made us!

It behooves us then, to humble ourselves before the offended Power, to confess our national sins, and to pray for clemency and forgiveness ….

All this being done, in sincerity and truth, let us then rest humbly in the hope authorized by the Divine teachings, that the united cry of the Nation will be heard on high, and answered with blessings, no less than the pardon of our national sins, and the restoration of our now divided and suffering Country, to its former happy condition of unity and peace.51

Offense and Defense on the Rappahannock River

Demonstrating the true activity of the “winter encampment,” on March 25, the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry mounted a riverine expedition southeast into Westmoreland County. Under the command of Lt. Col. Lucius Fairchild, the Iron Brigade soldiers boarded the steamer W. W. Frasier at Belle Plain Landing at 4:00 p.m.—26 officers and 241 enlisted men, accompanied by 20 attached cavalrymen. Moving to the Potomac River, they traveled through the night and steamed 60 miles into Confederate-held territory.

Anchoring at daylight, the disembarked cavalry reconnoitered for three hours toward Lower Machodoc Creek. The W. W. Frasier then moved down river to meet them. The entire force remained three days, commandeering supplies and materiel: 15 horses and mules; 300 pounds of bacon; 230 bushels of wheat; 25 bushels of oats; 15 bushels of beans; 3,000 bushels of corn; two harnesses; two anchors; and a chain cable from a destroyed “rebel schooner.”

On the morning of March 28, the cavalry squad and 23 infantry volunteers—presumably mounted on the captured animals—departed under Capt. James D. Wood to return overland. This detachment rode or herded 48 confiscated horses and mules back to Belle Plain by the twenty-ninth. The remaining force had returned by steamer at 8:00 p.m. the previous night. They brought with them four civilians from Richmond County; a Confederate soldier—presumably a deserter—named Everett and his wife and child; another lady and child; and 30 “contrabands” now headed for freedom. While not the stuff of glory, such raids demonstrated tactical creativity and potentially kept the Confederates off-balance. They also secured needed supplies and animals—and deprived the enemy of them.52

The raids illustrated one of the very concerns weighing on Hooker’s mind. Recalling earlier contingency plans for fortifications to defend Aquia Landing from raids and attacks, Hooker issued detailed instructions on March 30 addressed to commanding officers at Aquia Creek Landing, Accokeek Creek Railroad Bridge, and Potomac Creek Railroad Bridge. A positive action by army headquarters, it was nevertheless written in Hooker’s characteristic tone and overly prescriptive style, and although lengthy, it is worth reprinting here in full:

Commanding Officer, Aquia Creek Landing: The defenses of this place consist of a line of slashing, running from King’s house, on Aquia Creek, south to Accakeek Creek, strengthened by two redoubts and an advanced redoubt near Watson’s house, occupying a position from which the enemy might shell the landing. These redoubts are numbered from right to left, No. 1 being near the Watson house, No. 2 on the Stafford Court House road, and No. 3 near the railroad. The enemy might attack, first, to force their way at once to the depots; secondly, to reach the hills over the depots to shell the latter; thirdly, by shelling depots from the north side of Aquia Creek, and simultaneously engage or threaten the redoubts and shell the depots from the north side. The first two attacks would fail if the advanced redoubt and defensive line were held. To do this, Redoubt No. 1 will have a garrison of 100 men and no guns; Redoubt No. 2 a garrison of 200 men and two 3-inch guns; Redoubt No. 3 a garrison of 100 men and four 3-inch guns, these guns in Redoubt No. 3 being outside the work. There should be a post of one company where the slashing ends at Aquia Creek, to prevent cavalry moving along the shore, and a reserve of 800 men near Redoubt No. 2, to move when needed. One gunboat, at least, should be kept at Aquia Creek, to prevent the enemy from putting a battery in position on the north side of Aquia Creek, to shell the depots, and should be assisted by the guns taken from the redoubts and placed on the hills immediately over the landing, these hills completely commanding the north shore of Aquia Creek. In case the defensive line were forced, the gunboat would be of service in the immediate defense of the depots.

The commanding officer will keep up an efficient system of outposts and lookouts, so that there may be no possibility of surprise. It is doubtful if a cavalry raid would attempt to break through the line without first carrying one of the redoubts. The reserve should move to the threatened point, and, keeping a sufficient sub-reserve, take an active part in the defense. If Redoubt No. 2 or No. 3 were attacked, the reserve would form to its right and left, under its cover, and, if the enemy were repulsed, should charge to complete its overthrow.

The guns of these works are intended to fire at the enemy’s troops, not his guns. If the enemy should at any time shell a redoubt, the garrison should cover themselves by a parapet, or, if it was certain that no enemy was near, a part might get in the ditches, returning to the work the moment the artillery fire ceased. If any assault was made, the garrison should mount on the parapet and bayonet the enemy back into the ditch.

As Redoubt No. 1 is isolated, and must take care of itself, it should have a good officer in command.

The commanding officer will be held responsible that the works are kept in perfect repair.

Commanding Officer, Accakeek Creek Railroad Bridge: The garrison for the upper redoubt will be 100 men; for the lower, 25 men. When not surrounded by other troops, the commanding officer must take every precaution against surprise, keeping the garrison at the works and maintaining sufficient guards and lookouts both by day and night. If the attack were in the day, an attempt would probably be made to carry the works, as would be difficult to burn the bridge without. This attempt might be preceded by shelling. Ordinarily no reply should be made to this, as the guns are intended to fire at troops, and not to run the risk of being disabled by a superior artillery. The garrison should shelter themselves behind the parapets; or, if it is certain the enemy are not near the works, a part might get in the ditches, returning to the work the moment the artillery fire ceases. If the enemy attempts an assault, as soon as he reaches the ditches the garrison should rush on the parapet and bayonet him as he attempts to ascend.

At night the enemy might try to burn the bridge without taking the works. In this case a part of the garrison of the upper redoubt should move down to the bridge, keeping in good order, and attack the enemy, knowing the ground well. Having a secure place to fall back on, they would have every advantage over him. If the lower redoubt were taken, the bridge would be defended with musketry and canister from the upper.

More men can fight in these works than can well sleep in them. In case of an alarm, all railroad guards and others in the vicinity should at once rally upon the works.

The commanding officer will be held responsible that the works are kept in perfect repair.

Commanding Officer, Potomac Creek Railroad Bridge: The garrison for the upper redoubt will be 75 men; for the lower, 75 men, with two 3-inch guns outside; for the stockade, at the south end of bridge, 50 men, and for the block-house at the northern end, 30 men.

When not surrounded by other troops, the commanding officer must take every precaution against surprise, keeping the garrison at the works, and maintaining efficient guards and lookouts both by day and night. If the attack were in the day, an attempt would probably be made to carry the works, as it would be difficult to burn the bridge without. This attempt might be preceded by shelling. Ordinarily no reply should be made to this, as the guns are intended to be fired at troops, and not to run the risk of being disabled by a superior artillery. The garrison should shelter themselves behind the parapets; or, if it is certain the enemy are not near the works, a part might get in the ditches, returning to the work the moment the artillery fire ceases. If the enemy attempts an assault, as soon as he reaches the ditches the garrison should rush on the parapet and bayonet him as he attempts to ascend.

At night the enemy might try to burn the bridge without taking the works. In this case a part of the garrison of the two upper redoubt should move down to the bridge, keeping in good order, and attack the enemy. Knowing the ground well, and having a secure place to fall back on, they would have every advantage over him.

A good officer should have command of the upper redoubt, which should be held to the last, as, if this were taken, it would be difficult to hold the lower. More men can fight in these works than can well sleep in them. In case of an alarm, all railroad and other guards in the vicinity should at once rally upon the works.

The commanding officer will be held responsible that the works are kept in perfect repair.

Memoranda with regard to the artillery,—The engineers ask for ten guns—six for the defenses of the landing at Aquia Creek and two for each of the railroad bridges. Should it be deemed necessary to move the guns from the works at the landing to fire across Aquia Creek, a field battery should be furnished—two sections of guns, under a captain at Redoubt No. 3 (Comstock’s numbers), one section at No. 2, the caissons, stables, &c., at a central position between and in rear of these ….

The captain of the battery at the landing should be directed to have men properly drilled and instructed, and be required to see that the ammunition, magazines, &c., are kept complete and in good order.53

Lingering Problems, but Overall Improvement

By March 25, Maj. Rufus Dawes had returned from leave to rejoin the 6th Wisconsin of the Iron Brigade at Belle Plain. “I am safe and sound in camp,” he declared. “There are great preparations everywhere in the army for hard campaigning and hard fighting.” His former commander, Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler, now led the nearby 2nd Brigade of the I Corps’ 1st Division. In the 6th Wisconsin, the governor had commissioned Col. Edward S. Bragg as commander, Rufus Dawes as lieutenant colonel, and John F. Hauser as major. “The regiment is fine trim this spring,” Dawes reaffirmed. “My visit home was pleasant indeed and I shall go into the new campaign with courage and hope, renewed by the sympathy and encouragement I received at Marietta.”54

Yet the army Dawes returned to had itself been undergoing renewal. War Democrat Lt. John C. Griswold[,] 154th New York Infantry, summarized three months of changes in a March 16 letter:

On our arrival at Falmouth 3 days after the defeat at Fredericksburg we found the soldiers in a condition bordering on insubordination. Some regiments went so far as to declare that they would never go into another fight with the rebels, that there was no use trying any more for we could never subdue them by force, that it was nothing but a damn nigger war, and that sooner it was settled on peace terms the better. My faith in our final success is stronger today than it was 3 months since. All that is wanting is a united effort & a firm determination on the part of the whole people to sustain the government; & it resolves into a mere question of time as to our final success.55

“I suppose the army is in good Condition now,” wrote McClellan-supporter James E. Decker of the 1st New York Artillery on March 23. “If we had little Mac to lead us on we would be all ready for work but I suppose we will have to be ready as it is. Hooker is a good man.”56

“I think there never was a commander of this army that had the confidence of the whole army to the same degree that Hooker has got,” wrote James T. Miller of the 111th Pennsylvania on March 30, “and I expect he will give us a chance to see the elephant before long.”57

The passing calendar and improving weather made it clear enough that the campaign season was approaching, but more importantly, a sense of expectancy hung nearly palpable in the air, and everyone in the army could feel it. “Everything goes on improving, the weather and the roads, the dispositions of the army,” wrote a soldier from the 26th Wisconsin in a letter published in the Milwaukee Sentinel, “even the administration seems to be endowed with a better spirit, and with a new enthusiasm, I may almost say, a certainty of victory, we long for the approaching Spring campaign. Hooker is full of energy, and gaining the general confidence. Our cavalry performed some daring tricks, and promises to be of use hereafter. Besides, our infantry and artillery, if well led, are superior to that of the enemy, and with a cheerful heart the patriot may contemplate the future, it dawns.”58

The coming campaign, predicted the Badger, would be “the bloodiest of the whole war,” “fighting will be done with the rage of desperation,” and “blood will flow in streams, and many a one of our young regiment will also have to sacrifice his life.” Such sacrifice would not be in vain and, “in spite of all impediments, in defiance of all the efforts of your true friends (?) of the North [i.e., Copperheads],” the army would be victorious and destroy the “contemptible slaveholding oligarchy.”

The infantryman of the 26th continued:

the soldier does not forget that at this moment he is the only pillar of the country, that all who care for liberty, equality, in short, for the Union, cling to him as the last anchor of hope, and his courage, his zeal increases with danger. He knows very well that under present circumstances, his personal welfare (I will not say his security) is closely allied with the welfare and success of the Union. All that is sacred to man, the love of fatherland, liberty, his personal honor, incites him to the fulfillment of his duty, and that he yet wavered, stands as firm as a rock.

Copperhead leaders were conceptually culled from the people. Their “peace” doctrine was, continued the editorial, “Obtained by means of our arms, peace is the glorious aim the patriot strives for, the much wished for end of bloody combats the wearied soldier longs for the regeneration of the Union, the beginning of her everlasting happy continuance. That peace however the peace party can and will procure for us is the beginning of everlasting reproach, disgraceful oppression, and as a necessary consequence, an eternal dissension.”

“In the Army as everywhere,” the Wisconsinite continued, adding that it was the “general view of the soldiers here,”

the opinion of the ignorant, uneducated is determined by success only. If our Army is victorious, then our cause is a glorious one, and an immense patriotism takes hold of the masses. But if we are met with misfortune, if we are repulsed, we become discouraged, and the whole story is nothing but humbug! Yes, many among us there are, whose patriotism is solely dependent upon the quantity of the rations, the regular appearance of the paymaster, etc…. The disposition of the Army rests alone in the spirit that prevails with the thinking, educated portion of the soldiers and the officers. If this portion is imbued with the right spirit, then all the bearing of ill will from abroad cannot demoralize the Army.

Like Dawes’ March 16 speech in Marietta, the Wisconsin infantryman’s letter captured the quiet revolution underway in the Stafford camps. “Indeed, all I said in my speech about the army is strictly true,” Dawes affirmed back in camp. “I am glad to be on the record in that speech. I don’t want stock in anything better than that kind of doctrine just now.”59

March 1863 ended, then, with universal signs of resurgent spirit and fighting capacity. Most of what Hooker and Butterfield had attempted, and no doubt hoped for, was taking place at the hands of better corps and division commanders. Within brigades and regiments, leadership experience was finally paying off. New, spirited units were reinforcing the old regiments. The cruel winter gave way to spring. Rest and relaxation had improved morale as much as the other steps: better food; more timely pay; better unit pride, cohesion and spirit; the officers and men finally united against a common foe (the Copperheads); positive steps taken to make cavalry, intelligence, picket duty, straggler control, medical service, communications and tactical logistics, and ordnance support all more effective. Objectively, any or all of these measures could have been taken earlier. The grim qualitative realities, an inability to overcome teamwork shortfalls, and an indecisive execution of missions continued to drag on army resurgence.

But, as April rose on the horizon, further improvement awaited, as did a natural desire for action. “Spring time has come, and as the birds and insects give vent to their voices, one is led to think of the good old times in Jersey when peace and tranquility reigned supreme,” mused soldier “L.A.V.,” of the 15th New Jersey stationed at White Oak Church. “The calm evenings give occasion for many remarks of the following import: ‘What a pleasant evening for promenading. O that I were home gallanting a handsome Miss, enjoying nature’s splendor, &c.”

But his letter soon turned to the serious business on everyone’s mind. He knew the entire nation waited to see the army resurgent. “The universal confidence in Joe Hooker will, I believe, insure us of victory,” he predicted; “if not, we will try again, for this country must be saved intact, and there shall be no peace until the traitors cease to tread the soil so gallantly won by our Revolutionary sires. The day of compromises is past, and our Independence must be sustained at the point of the bayonet, if necessary.”60

1 CHJHCF. Cites: “Lancaster Daily Express of April 3, 1863;” Copy of original. BV 182, part 3, letters of Sgt. C. Hickox to his cousin, Miss Charlotte Hickox of Solon, Ohio.

2 Ibid.

3 CHJHCF. Cites: “Rochester Democrat and American of March 20, 1863,” in which this letter appeared, dated March 14, appeared.

4 OR, 25, part I, 45-47.

5 Ibid.

6 BV 317, part 6, FSNMP. Letters in the Rochester Daily Union and Advertiser, published on April 1, 1863 from correspondence of March 25.

7 Hooker’s diatribe is from Hebert, Fighting Joe Hooker, 186; this was quoted from Frank Moore, Anecdotes, Poetry and Incidents of the War: North and South 1860-1865 (New York, NY), 305.

8 OR, 25, part I, 74-75.

9 Ibid., 47-64.

10 Ibid.

11 McIntosh’s report incorrectly says 6:00 a.m.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid. Part II, p. 148 for Stanton’s full response (March 19).

15 Ibid. Stuart quote in OR, 25, part II, 858. The story of Pelham’s death is recounted in detail in Burke Davis, J.E.B. Stuart: The Last Cavalier (New York, NY, 1957), 271-277. Additional reaction can be found in Jeffry D. Wert’s Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J. E. B. Stuart (New York, NY, 2008), 208-210.

16 Evans, War of the Aeronauts.

17 OR, 25, part II, 150, 167.

18 Chesson, ed., J. Franklin Dyer, Journal of a Civil War Surgeon, 63-64.

19 OR, 25, part II, 148-149.

20 Ibid., 156-158.

21 Haupt, Reminiscences of General Herman Haupt.

22 OR, 25, Part II, 160-161.

23 OR, 25, part II, 152. This was the origin of shoulder and combat patches/badges in the U. S. Army.

24 Ibid., 151. There was intent to have a distinctive corps badge for the cavalry. An elaborate one was developed with crossed sabers on a blue field atop and radiating eight-point star.

25 Ibid, 167. Corps staff and troops later wore versions showing all division colors.

26 Ibid, 145.

27 Ibid.

28 St. Clair Mulholland, A Story of the 116th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion. (Philadelphia, PA, 1903), 77, as quoted in Jane Conner, Lincoln in Stafford, 37.

29 Favill, Diary of a Young Officer in BV 196, part 1, FSNMP. Princess Agnes Salm-Salm’s story is summarized in Jane Hollenbeck Conner, Sinners, Saints and Soldiers in Civil War Stafford, (Stafford, VA., 2009).

30 OR, 25, part II, 147.

31 Oliver Wilson Davis, Life of David Bell Birney, Major General United States Volunteers (Philadelphia, PA, 1867), 119, 126-127; Gilbert Adams Hays, comp., Under the Red Patch: Story of the Sixty-third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers (Pittsburgh, PA, 1908), 176, both quoted in Jane Conner, Lincoln in Stafford, 37-38. BV 317, part 4, FSNMP, Decker letters.

32 CHJHCF. Data in text.

33 Adams, Reminiscences of the Nineteenth Massachusetts Regiment, Chapter 7.

34 BV 327, part 5, FSNMP, Letters of Col. Joseph Snider (1827-1904), 7th Virginia (U. S.) Infantry. This letter was written from Headquarters, 1-3-II AC, “Camp near Falmouth, Va.” West Virginia did not become a state until June 20, 1863, therefore used Virginia in unit title.

35 Ibid.