Projection and the Negative of Love

AS AMERICANS PURSUED behaviorism and cognitive stereotypes in the hopes of solving the riddle of xenophobia, Europeans followed alternative strategies. After all, there was much room to differ. Behaviorism featured actions without actors, while psychologies of the stereotype were models of thought shorn of thinkers. In Europe, those absences seemed glaring and would be taken up.

In Western and Central Europe, models of the mind emerged that focused on the concept of “projection.” Projection was an old idea and, at first blush, rather simple. We stare out at complex, ambiguous realities and unwittingly discover feelings, ideas, attributes, and identities out there that actually emanate from our own minds. The pre-Socratic philosopher Xenophanes of Colophon may have been the first Westerner to recognize this human proclivity. An exiled itinerant, he noticed that when Homer or Hesiod described the gods, they bore a great resemblance to the authors themselves. Since then, many—from Plato to the post-Kantian idealists—have observed how we clothe the outer world in our own predilections, how we falsely and unwittingly generalize from our own condition.

The original theory of projection did not account for xenophobia, but rather its opposite. By willfully seeing ourselves in others, we flatten out differences and turn those who may be quite distinct into beings no different from ourselves. Numerous thinkers saw romantic love, the national family, and other collectives as derived from Xenophanic projection. “Sympathy,” as deployed by eighteenth-century thinkers from Adam Smith to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and the nineteenth-century German idea of “empathy,” that process of feeling one’s way into another, both held at their core the kind of projection that can be boiled down to this: “I am like you.”

Projection could quickly degenerate into a self-centered, complacent stance. If we all relied on projection to know the world around us, perhaps reality might be concocted, close to a dream. This worry found its way into debates on the philosophical problem of other minds. How do we know anyone else has a mind? We can’t see it, touch it, or confirm its presence. The less spooky version of the question veers from whether we are surrounded by zombies who have no minds at all to the more modest problem of how we truly know anything that goes on inside another’s head. In 1865, John Stuart Mill acknowledged that the only stream of consciousness we could know was our own, but he refused the skeptic’s conclusion that we had no evidence of “our fellow creatures” and were “alone in the universe.” Between my sensory inputs and my behavior, Mill argued, I directly know of a third element, my mental experiences. I am right to infer that other humans have an analogous inner experience. And so the only way to know another’s mind, in fact, was through projection.

Mill’s solution was attacked. Weren’t his conclusions unverifiable, mere analogies, and unjustified generalizations based on a single case, that is, his own? In addition, didn’t similar effects in nature commonly have a multiplicity of causes? So why were his mental processes necessarily those of another? In the 1920s, philosophers, particularly those centered at Cambridge University, took up this head-scratching conundrum. The refined, at times esoteric, philosophical debates engaged by Ludwig Wittgenstein, Bertrand Russell, Gilbert Ryle, and others paralleled a rising tide of social and political challenges in a global community, in which confident claims about knowing the mind of “primitives” and foreigners began to be challenged. If Wittgenstein asked whether his itch really was the same as your itch, his red the exact replica of your red, an administrator at the East India Company, like John Stuart Mill, could be forced to consider whether what he claimed to know about a Bengalese farmer’s mind was all a projection.

By the time Wittgenstein took up this problem, the notion of projection as delusion had been employed by psychiatrists and neurologists, none more influential than Sigmund Freud. The son of Galician Jews who immigrated to Vienna, Freud attended university and medical school in Vienna, where he joined a generation committed to scientific knowledge, secular ethics, and liberal politics. They lived in the center of Emperor Franz Joseph’s struggling empire, a sprawling multiethnic entity, so polyglot that its parliament was a Babel of languages. Amid vast ethnic and linguistic differences, a unifying force was widespread anti-Semitism. As they had in Spain long before, Jews became a symbolic enemy that united many who might otherwise have been quite foreign to each other.

Deeply influenced by the thought of his time, Sigmund Freud also was boldly, at times radically, innovative. He rebelled against theories of degenerative heredity, that mark of Cain that magically explained an array of illnesses and often stigmatized the Jews. Instead, Freud began to consider the role of psychological forces alone in mental health and illness. Toward that end, he assumed that the mind—like other biological entities—existed in a dynamic balance. Disruptive ideas and affects needed to be regulated or neutralized. But how? If external threats like a lion were managed by the “fight or flight” response, what to do when the threats came from within?

Around 1895, Freud came to conclude that the mind must possess some sort of self-regulating, defensive system. Defenses allowed the psyche to manipulate or even dispel disruptive ideas from consciousness, and thereby regain the repose that came with not knowing or not feeling one’s own distress. One primal defense was projection. Writing to his colleague, the physician Wilhelm Fliess, he declared: “Whenever an internal change occurs, we have the choice of assuming either an internal or an external cause.” In choosing to locate the cause outside of ourselves, we take advantage of “the mechanism of projection for purposes of defense.”

While inaugurating projection as a defense, Freud powerfully altered the term’s original meaning and engendered an ambiguity that would long befuddle readers. Sometimes in his vast writings, he used projection in the older manner: his first notions of transference, for example, take off from Xenophanes. The Viennese physician spoke of inner “stereotypes”—in the printing press sense—prototypes of qualities and relations with significant others that, once imprinted on a child, were replicated. In this manner, bosses, lovers, and doctors unconsciously became our parents. Sibling competition took shape on a factory line, and a new boyfriend somehow seemed to do the same mortifying things as one’s father. Thus old dramas magically kept being restaged. From this one could neither run nor hide. What was shall always be. Sameness ruled.

However, simultaneously, Freud developed a totally contrary, quite original theory of defensive projection, which involved two steps. The first was repression, the internal capacity to make some intolerable thought or feeling or memory unconscious. Then, in paranoia for example, unconscious ideas or affects were projected onto another. If Xenophanes’s conception erased external difference, this did exactly the reverse. It constructed a “not Me,” from all I shudder at and reject in myself. The equation could be boiled down to this: you are what I am not. You are what I loathe (in myself). Freudian projection artificially created interpersonal difference. Peace was restored internally, while war was declared on a concocted enemy. A perfect and sanitized Me had become conflict-free by dumping its shameful and guilt-ridden contents onto some unwitting Not-Me.

What was expelled here was precisely what must not be my own. Inner strife was thereby resolved by creating conflict with an eerily familiar foe. The stalker, the permanent enemy, and the threatening foreigner were laden with all that was repelled from the self. And so these tense encounters strangely resembled reunions; they were misted with an uncanny sense of return. Never has the motto “Hold one’s enemies close” been more to the point. Through this kind of projection, our enemies possessed parts of our own inner lives. Thus the con man denounced his accountant as a secret schemer; the philandering spouse became obsessed by oddly dubious evidence of his partner’s infidelity; and the brutally quieted and intimidated child, ashamed of his own helplessness, brutally intimidated the class weakling.

The problem with projection was not only did it impact reality testing, it also mandated warfare that was unending. No compromise or rational peace could be worked out when the enemy was psychically so required. Defensive projection allowed for an internal peace only as long as the battle with the enemy was engaged. If the dreaded ones were defeated, new enemies would be required to contain what otherwise felt unbearable.

Xenophanes’s projection glibly assumed commonality, while Freudian projection made for an equally unreal relation. If knowing others was constantly a matter of imagining and inferring, projective theories now embraced two polar kinds of distortion, the first a presumption of sameness that falsely papered over individual difference, and the second a fantasized disjuncture that created hostile division.

For Freud, defensive projection first made sense of severe cases of paranoia. Hallucinated devils and tormenting voices escaped from the diseased mind and occupied the air. However, he increasingly began to see that the same mechanism was involved in the phobias. As troubling feelings disappeared from within, a localized terror took their place. The patient now was frightened of a mouse or crossing an empty square. Rid of the intolerable anxiety that stemmed from their own urges, feelings, and ideas, the sufferer became consumed by the scary embodiment of those urges. There was no shock or buzzer here. For Freud, the trauma was simply the oppressive demand to be civilized. “Life, as we find it, is too hard for us; it brings us too many pains,” he would write in his masterful dystopian essay, Civilization and Its Discontents.

After Freud, the thinker who expanded psychoanalytic models of projection most was Melanie Klein. Klein was an original who had the courage of her convictions and then some. Born in Vienna in 1882, she married and moved to Budapest in 1910, where the young mother became depressed and went into analysis with Sándor Ferenczi. He encouraged her to work with children, and after she met Freud at the psychoanalytic congress of 1918, she was inspired to make child analysis her calling. Observing fearful children, she noted that they were fretful whether their teachers were bullies or lovely and kind. Was this projection, even at such a tender age? A terror-ridden, obsessional six-year-old named Erna concocted imaginary games in which Klein would undergo “fantastic tortures and humiliations.” The girl lustily partook of “rages which were vented on objects in my room, such as cushions, etc.; dirtying and destroying of playthings, smearing paper with water, plasticine, pencils and so forth.” All this was a source of great mirth, but once her wild games ceased, fears and phobias came roaring back. Freudian projection, Klein concluded, played a central role not only in paranoiacs but also in children—that is, in all of us.

During the late nineteenth century, psychologists had noted that tranquil year-old infants became “exceedingly bashful” before someone they did not know, a state the psychoanalyst René Spitz would later call “stranger anxiety.” That seemed to normally pass by around the age of two. But what caused it? Klein argued that projection was the culprit. Aggression in the very young was an overwhelming force that could only be managed by such a forceful expulsion. Little Erna awoke to a fairy tale–like world inhabited by “split” representations of all good and all evil beings. Projection created a mother-witch, and splitting preserved an angelic, all-good mother. The child shuddered before her monsters. Early childhood, Klein suggested, was a horror movie of our own making. In what Klein dubbed the “paranoid position,” good and evil never mixed. Beings were one or the other. Normally, as the child matured, she developed capacities for ambivalence and guilt, and could manage her aggression so that others were allowed to take on more nuance, be whole beings.

Melanie Klein concluded that little Erna had something to teach us about sociopathic murderers. Through projection, the child/criminal must get “rid of his objects in part to silence the intolerable threats” inside. Anxiety compelled him to “destroy” the villain, which when successful only led to an increase in anxiety and the need to act again. And so, the self-pitying murderer believed “it is because he is persecuted … that he goes about destroying others.” Meanwhile, outsiders, strangers, and foreigners need do little to fulfill the role of enemy. The Great War, Klein suggested, was a fine example of this projective dynamic in action. It had been driven by the “phantastic belief in a God who would assist in the perpetration of every sort of atrocity … in order to destroy the enemy and his country.”

AS WEIMAR PSYCHOANALYSTS wrote about projections and fantasied enemies, a fragmenting Europe began to seize on its imagined ghouls. The League of Nations’ Institute of Intellectual Cooperation called on Klein’s colleague, the British doctor Edward Glover, to consider the psychology of war, and help them comprehend paranoid, homicidal types whose commitment to hatred was complete. In 1933, the League sponsored an exchange between Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud. The two fabled thinkers wondered if there was a way to harness and direct human aggression elsewhere. Freud’s conclusions were not encouraging. Three years later, another analyst, R. E. Money-Kyrle, described to the Oxford University Anthropological Society the newly consolidated “paranoiac” theory of war. War was a process in which projected fantastic distortions justified and moralized one’s own sadism. All sides claimed they acted in self-defense. All sides used whatever means necessary. War was a communal form of mass projection that created xenophobic paranoia against vilified strangers, and when it spread, it was a collective form of suicide.

Here Money-Kryle stumbled upon a seemingly understated part of the trouble: war was the act of a collective. So too were race riots in Chicago, pogroms in Kiev, and “bear hunts” in Aigues-Mortes. These acts of terror were attributable to rioting crowds. As Europe’s order collapsed before their eyes, a few analysts dared to move from their consulting rooms to group psychology to consider how projected hatreds created mobs.

By the time the psychoanalysts turned their attention to mass psychology, this field had been a focus of study, fostered in part by European colonists. The most famed effort came from the Frenchman Gustave Le Bon. Born in 1841, Le Bon began his career as a physician, who hoped to make it big with a series of thin books. Readers found them too thin. Interested in race, craniology, and collective minds, Le Bon took up colonial anthropology and Spencerian evolutionary theories. The experts who championed those theories did not take up him. Undeterred, Le Bon applied for a grant to study the inhabitants of Algeria, but was rejected. He went anyway, whipped off a book, and promptly applied for the same grant to go to India. This time, his resolve was rewarded. After penning books on the French colonies, the Arabs, and then the inhabitants of India, Le Bon began to consider a general theory of groups.

Group psychology posed grave epistemological problems; was there even such a thing as a group mind? There was, Le Bon concluded. A fierce nationalist, he had grown greatly worried about the Asian and African rabble, and the potential of a mass revolt from colonized peoples as well as France’s internal enemies, the socialists. In search of a model for such eruptions of collective madness, he turned to models of hypnotic suggestion. The French doctor Hippolyte Bernheim claimed that suggestion—in which an idea passed effortlessly from one mind to another—unconsciously occurred in normal interactions, not just among the hypnotized. Dazzling rhetoricians could play the role once reserved for a Mesmerist. When he came upon that notion, Le Bon had an “aha!” moment and dashed off the work that made his fortune, The Psychology of Crowds.

When individuals merge into a crowd, Le Bon proposed, they literally lose themselves. In so doing, they become a herd, deeply susceptible to suggestion. Crowd deliriums were due to contagious ideas traveling like lightning, not from one rational subject to another, but rather to less than fully conscious beings in the mass. Le Bon’s “law of mental unity” meant that each member of the group sought to imitate the other. To manipulate a group, he wrote, “it is necessary first to take account of the sentiments by which they are animated to pretend to share them, and then try to modify them, by provoking, by means of rudimentary associations, certain very suggestive images.” With the right demagogue, mass suggestion and imitation worked like charms. Almost always. An Arab or Chinese crowd was much more vulnerable than an English crowd. “Stronger” races demonstrated less susceptibility to such irrational behavior. Beware, then, the mass hysterias of inferior races, the Frenchman warned. This, he later added, included Germans.

In 1921, when Sigmund Freud began to consider mass psychology, he had to go through Le Bon, who was considered seminal despite his nationalism, racism, and reactionary politics. After a careful approach and some weak praise, Freud slowly put the knife in. Le Bon’s explanatory notions, the crowd’s credulity and suggestibility, were simplistic, not racial at all, but rather universally rooted in the helpless dependence of childhood. In crowds, those deferential feelings were revived through a Xenophanic projection in which the subject symbolically experienced the group leader as a parent. Therefore, the leader was imbued with love normally reserved by their followers for themselves. Rather dangerously, the leader also took command of what once derived from one’s parents; the group members re-externalized their conscience and imbued their leader with this self-regulatory function. As parents once directed their children, he dictated what was right and wrong. Leaders capable of attracting such projections possessed what sociologist Max Weber called “charisma,” what Le Bon called “prestige,” and what Freud considered the capacity to elicit an infantile abdication of individual will.

This shared, if twisted, kind of love between supplicant and superior bound individuals into a group, created cohesive and unified teams, and even made for nations. To dissent, to fail to yield to the charismatic chief, Freud proposed, would be seen as treachery. The crowd turned on individuals who opposed them. Outsiders were a threat and an affront. “Opposition,” Freud later wrote, “is not necessarily enmity; it is merely made an occasion for enmity.” Strangers, aliens, and foreigners offered such an occasion. Before such heterogeneity, the crowd redoubled their commitment to their leader, tightened their identifications with each other, and turned their fury outward.

For Freud, there was not a little bit of irony in all this. After 1910, the doctor had become the domineering patriarch of a Freudian movement; colleagues were turned into childlike disciples or viciously attacked and excommunicated. By 1914, all the most creative followers—Eugen Bleuler, Alfred Adler, Wilhelm Stekel, and Carl Jung—had departed. The movement crumbled and then, after the Great War, Freud discovered that regrouping psychoanalysts were no longer as interested in being an infantilized group that followed his paternal lead.

By the time he sat down to write Civilization and Its Discontents in 1930, the Viennese thinker had watched the decay of liberalism in Europe and had grown more pessimistic. Once he had insisted that sexual libido was the sole source of unconscious human motivation. He had demolished Alfred Adler for proposing that aggression was equally a force with which to be reckoned. Of Adler, he wrote to a colleague, “he has created for himself a world without love, and I am in the process of carrying out on him the revenge of the offended goddess Libido.” However, after the slaughters of World War I, Freud came to the view that Eros, the goddess of love, had a rival, an inherent aggressive drive he called Thanatos. Lately it seemed this force was winning.

Consider the stranger, Freud wrote. In Judeo-Christian society, the moral demand was to be xenophilic, to love him. Like Saint Francis of Assisi, we should spread our sublimated erotic force out over all of God’s creations. “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” we are urged. Love someone who has shown me no affection? Hard to do, the aged psychoanalyst conceded. To join a civilized brotherhood or sisterhood, we must repress the aggressive forces that charge our own desires and individuality. When an outsider appeared, he was a powerful magnet for such repressed aggressiveness. Strangers, Freud wrote, echoing Georg Simmel, were unwitting objects of pent-up frustration from the civilized:

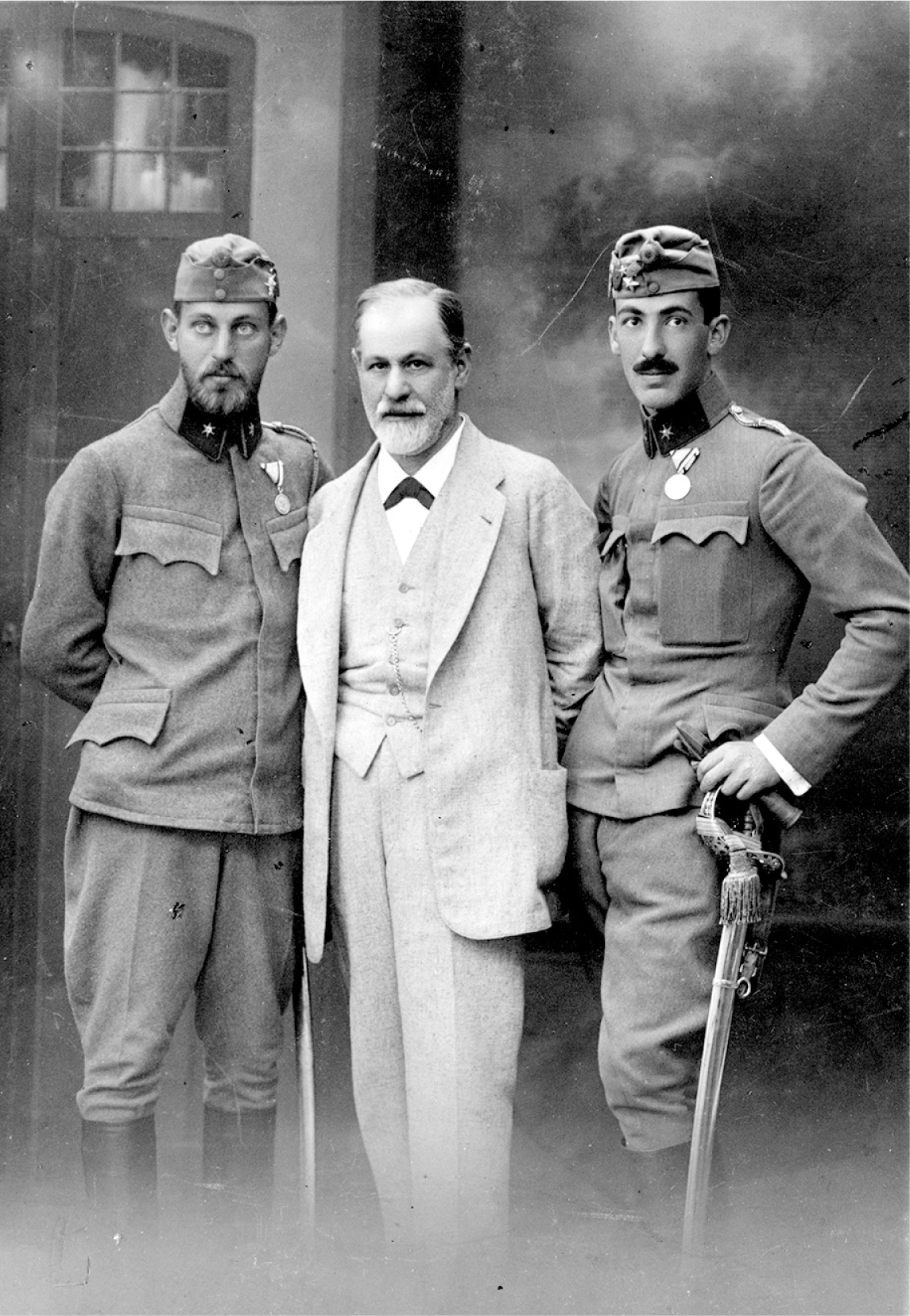

Sigmund Freud with two of his sons during World War I

The advantage which a comparatively small cultural group offers of allowing this instinct [aggression] an outlet in the form of hostility against intruders is not to be despised. It is always possible to bind together a considerable number of people in love, so long as there are other people left over to receive the manifestations of their aggressiveness.

Groups, Freud asserted, need somebody to hate. Through the offices of projection, they were therefore created. However, Freud could not but note that such aliens were, comically enough, often hardly different from the beloved insiders. Spaniards despised the Portuguese. The English and the Scottish sneered at each other. North and South Germans could not countenance their inscrutable compatriots. For anyone looking on from afar, it was absurd. Freud dubbed this quarrelsomeness “the narcissism of minor differences.” As for the Soviet experiment with communism, its zeal for equality, Freud predicted, would psychically require scapegoats. For the impossible demands of fraternity, by the laws of defensive projection, would lead to a perpetual war against those who were denounced as selfish, strangers who refused immersion into the commune.

WITH THE 1933 ELECTION of Adolf Hitler, virulent anti-Semites massed in Germany and were on the march. Others frantically sought to make sense of this swirling hatred. Psychoanalytic efforts ranged from the Freudo-Marxist account by Wilhelm Reich’s The Mass Psychology of Fascism to extrapolations from family pathologies by, among others, John Bowlby. Social psychologists, like Kurt Lewin, also tried to make sense of this madness. Trained in the Gestalt tradition by which the whole was greater than the sum of its parts, Lewin would coin the term “group dynamics”; he argued that groups acquired distinct emergent properties that organized them and directed their actions. After emigrating to the United States, he devoted much energy to comprehending how groups made up of quite dissimilar beings—for example, men, women, children, or an array of individuals who happen to share a religion—unite around the interdependence of shared tasks or a common fate. Lewin sought to use this model to comprehend and then intervene when groups turned on minorities, work taken up by others after his untimely death in 1947.

However, the most substantial attempt to comprehend the origins of such paranoia and xenophobia came from someone who was by training not a psychologist nor a psychoanalyst, economist, or sociologist. In fact, he and his colleagues scorned any such distinctions as “the departmentalization of the mind.”

Theodor Wiesengrund-Adorno was born in 1903 to a wealthy German wine merchant who had converted from Judaism, and a Corsican mother whose passion for music was handed down to her son. His was a warm family, so that, even as an adult, “Teddy’s” playful letters were animated by “Mummi, my Hippo Cow,” “Archibald Hippo King,” “Piggybald,” “Giraffe,” “Ancient Wondrous Hippo Cow Lady,” and others. This display of whimsy and ease would contrast with the boy’s intellectual severity. While in Frankfurt am Main, Wiesengrund-Adorno first seemed destined to be a pianist and composer. However, he began his doctoral studies in philosophy and, in 1921, fatefully introduced himself to Max Horkheimer, a much older student who also had attended a psychology seminar taught by Adhémar Gelb. Max, the student wrote home, came “from a well-to-do family” and displayed “a certain detached interest in scholarship.” Two years later, Wiesengrund-Adorno met another passionate searcher named Walter Benjamin. They too became fast friends.

In 1925, after finishing his doctorate, Teddy moved to Vienna to study with the famed atonal, twelve-tone composer Alban Berg. There he immersed himself in the Viennese scene, experimented with avant-garde music, and, as a critic and journalist, honed his sensibility. However, his compositions disappointed him, and the young man—who was by his own admission “brutally serious”—deemed himself a failure. While the power, beauty, and transformative possibilities of musical experience remained a point of orientation, Wiesengrund-Adorno returned to Frankfurt to join the Institute for Social Research.

The Frankfurt Institute had become a force when Wiesengrund-Adorno’s friend, Max Horkheimer, took charge in 1931. Following Horkheimer’s lead, the Institute focused on, among other pursuits, an integration of social and historical analyses with in-depth, individual psychology, or, to put it simply, a synthesis of Marx and Freud. A loose affiliation with the Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Institute helped, and integrative work that sought to make for a psycho-politics commenced with the work of Erich Fromm and, later, Herbert Marcuse. Having studied Gestalt psychology as a doctoral student, intrigued by the Freudians, Wiesengrund-Adorno also threw himself into that ferment, just as the Institute launched studies that linked patriarchal authority in families with political power and economics.

As the Frankfurt community began to bear fruit, it was dispersed. With the Nazis on the rise, Wiesengrund-Adorno fled his homeland in 1934. Overnight, this atheist, born of a Christian mother and a converted Jewish father, learned that, in the Nazi symbolic order, he was simply a Jew. He made his way to the philosophy department at Oxford University. Horkheimer fled too, and reconstituted the Institute on Columbia University’s campus in New York City. Relations between the two exiled friends soon began to sour. On October 25, 1934, Horkheimer wrote, “I really must vent my growing resentment toward you,” and went on to list Wiesengrund-Adorno’s silence, slippery activities, and unreasonable demands. The next summer, Horkheimer wrote again of the young man’s haughty and unpleasant behavior, declaring that if his friend cared to repair their relations, he would need to come to New York to do so. By the fall of 1936, however, the old friends were again thick as thieves. Horkheimer became not just Wiesengrund-Adorno’s confidant, but also his ally, financial savior, editor, and at times coauthor.

Through Horkheimer, this displaced exile landed a plum position at the Princeton Office of Radio Research. It was a job for which he seemed well suited. Not only was he an expert on classical and avant-garde music, but he had also thought deeply about propaganda and the way radio had been weaponized by the Führer, who regularly beamed his speeches into German living rooms. Wiesengrund-Adorno told his parents that he was moving to America to study “pop songs and monopolistic propaganda.”

Now using only his mother’s name, Theodor Adorno arrived in the New World, but his landing was not soft. Aloof, melancholic, and dismissive, he clashed with his boss, the patient sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld. As for American radio, Adorno argued that popular music destroyed individuality, was conformist, commodified, regressive, depoliticized, passive, masochistic, meaningless, and false. Otherwise, he loved the stuff. Adorno was even immune to the beauty of that great American idiom, jazz.

Not surprisingly, Adorno’s position was terminated, and in 1941 he followed an ailing Max Horkheimer to warmer climes. In California, though, Adorno felt like a man from another planet. He had left behind Hegel and twelve-tone music for astrologers and Bugs Bunny. However, in his deep alienation, Adorno was not alone. Other brilliant German exiles had settled on the West Coast, including the novelist Thomas Mann, director Fritz Lang, actor Peter Lorre, and composer Arnold Schönberg. All fit Georg Simmel’s description of the stranger; free of American mores, they gazed upon this new landscape with wide eyes. And one thing they peered at was the film industry, with its mix of entertainment, stereotypes, and force-fed notions. It was an anti-art that Adorno savaged as a mindless and debased product, belched up by the “Culture Industry.”

Theodor Adorno

Adorno acutely felt his homelessness. In Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, his mix of autobiography and philosophical epigraphs, he wrote: “The past life of the emigres’ is, as we know, annulled.” “For a man who no longer has a homeland,” he added, “writing becomes a place to live.” Thus he came upon his solution. Feverishly, he wrote.

In a span of six years, Adorno completed three major works, all of which involved his interlocuter, Max Horkheimer. Written between 1944 and 1947, Minima Moralia was first conceived of as a birthday gift for Max. The two men then cowrote a cri de coeur called Dialectic of Enlightenment. At first glance, this work seemed perverse. Instead of following the liberal attack on fascism as a group regression from civility to tribal barbarism, Adorno and Horkheimer attacked the Enlightenment. That project of banishing premodern myth and defeating fear with science and reason had become its own antithesis, they contended. Scientific demand for certainty had resulted in a desiccated Cartesian man, whose intolerance of mystery resulted in the need to dominate not just nature but also other men. “Progress,” that once liberating force, had become totalitarian. Circulated secretly for years, this influential work was published by a Dutch press in 1947. By then, the authors had added a final section on anti-Semitism that foreshadowed their next effort.

After saving many European scholars by sponsoring their emigration, the Institute for Social Research was dangerously low on funds. Adorno himself was impoverished and at times desperate. He played with the idea of training to become a psychoanalyst so as to make his way out of penury. Then, Horkheimer approached the American Jewish Committee with a proposal to edit a series of book-length studies on anti-Semitism. Anxious to make sure Nazism did not take root in the United States, the sponsors agreed to fund the most “exhaustive study of prejudice ever attempted.”

The AJC research series that emerged was called Studies in Prejudice, but its five publications would be eclipsed by one. At just under 1000 pages, The Authoritarian Personality contained a mass of empirical studies conducted by a group of six psychologists. The lead author, tasked with the job of pulling all this together, was Adorno. To do so, he would argue that defenses like Freudian projection were commonplace for those who grew up under brutal patriarchs at home. Such upbringings laid the groundwork for men and women who were submissive followers of tyrants as well as angry, scapegoating anti-Semites.

In all this, Adorno leaned on research conducted in Germany by his Frankfurt colleagues. As the ranks of Nazis swelled, Horkheimer had been bewildered by the failure of the proletariat to act in its own self-interest. He had commissioned Erich Fromm, the new head of the Institute’s social psychology division, to study why the working class had not risen up against the Fascists. Over 3000 questionnaires were distributed and analyzed for the presence of three character types: the Authoritarian, the Revolutionary, and the Ambivalent. This turn to character structure followed a new generation of psychoanalysts like Franz Alexander and Wilhelm Reich, who considered stable defensive patterns far more central to therapy than analyzing neuroses. In the end, however, Fromm’s study was not published. By the time it was ready to go, Horkheimer was concerned that the analysis, with its valorization of the Revolutionary character, was far too Marxist for America. Instead, it was incorporated into the Institute’s 1936 Studies on Authority and the Family, another effort to understand how harsh parental authority yielded submissive and masochistic followers, all too willing to yield to leaders, and frustrated individuals who found relief in sadistic attacks on outsiders.

While in Frankfurt, Adorno had not been centrally involved in these projects, but Horkheimer chose him for this one, knowing he needed the income badly. In March of 1943, Adorno informed his parents that the anti-Semitism research had been funded; a few months later, he announced that he would take joint leadership of it. The gathering of data and clinical cases would be done by others—especially Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel Levinson, and Nevitt Sanford—but when the work was published in 1949, a great deal of the credit would go to its first author. Prior to this, Adorno had considered the vilification of Jews but had never made it central to his thought. In 1940, he suggested that Jews were the symbolic stranger, the perpetually wandering exile; later, he and Horkheimer proposed that Jews served specifically as scapegoats in capitalist economies. While the true exploiters remained mystified, the rage of the downtrodden came down on Jews, who were falsely said to be the primary beneficiaries of this rigged system. All that made sense, until the California data began to roll in.

The team went in search of anti-Semitic attitudes (A-S), as well as passions that were ethnocentric (E), pre-fascist (F), or based on political-economic ideology (PEC). The results showed strong correlations between anti-Semitism and ethnocentrism, which was defined as a general dislike of all other ethnicities. This, they found, also correlated with an uncritical admiration for one’s own group. American haters of Jews, the research showed, hated a lot of non-Jewish foreigners and were blind enthusiasts for the United States. Anti-Semitism, they discovered, was part of a larger pattern of discrimination in which the choice of victim was not so determining. Anti-Semitism had “little to do with the qualities of those against whom it is directed,” and therefore, if the out-group was tangible, if there was a tradition for such disdain, then the objects of hatred were exchangeable. Checking this hypothesis, the team broadened their questionnaires to test for xenophobic attitudes toward Armenians, Greeks, African Americans, and Mexicans. Jew haters tended to hate many of them, too.

Why? For Marxists like Adorno and his Institute colleagues, class conflict seemed like the answer. However, to their dismay, none of the study’s scales were highly associated with any one class, income group, or profession. Dockworkers and fat cats apparently succumbed to prejudice equally. Since Marx was wrong, they shifted to Freud. The researchers delved deeper into psychology, relying on a series of projective tests and clinical interviews. Originally in search of anti-Semitism, they discovered that the nature of their prey had changed. Now the critical question seemed to be: what lay at the foundation of xenophobic prejudice? How did these pre-fascistic, antidemocratic attitudes develop?

The answer was in the book’s title. To explain the “Authoritarian Personality,” Adorno took off from the studies of Freud and Fromm. All children, in this model, used projection to rid themselves of shameful and guilt-ridden thoughts and feeling. Therefore, in childhood, the outer world became home to these revenants, all the denied aspects of inner life. Normally, such primitive defenses were superseded as the maturing child took up psychic defenses that did not so drastically distort reality. Not so for the child of extremely harsh, authoritarian parents. That child was forced into a superficial, overly submissive stance. He became compliant, while idealizing and adoring his terrifying figures of authority. When interviewed by Adorno’s colleagues, such subjects blandly reported that their parents were perfect. They had great difficulty considering even minor flaws in their attitudes or conduct. At the same time, the subjects raged against an array of outsiders. Forced to submit to authoritarian parents, these children grew up to be authoritarians themselves; they projected their rage onto those deemed “weak” in their culture. Once they had families, the same projections molded their children. Thus authoritarians raised cowed and angry progeny who were destined to repeat the same pattern.

Products of such childhoods, Adorno argued, became hollow men, so deferential as to be unable to fully introspect. Stubbornly conventional, they filled themselves up with stereotypes and eagerly found groups to disdain. As for the particular choice of vilified object—Jew, African American, Mexican, Chinese, Turk—that was secondary. The basic need was to have someone to despise. For the Authoritarian Personality, hate had become their great passion. Of such a person, Adorno wrote, “he falls, as it were, negatively in love.”

Strangers played an unwitting role in this drama:

The primary hostile reaction is directed against foreigners per se, who are perceived as “uncanny.” This infantile fear of the strange is only subsequently “filled up” with the imagery of a specific group, stereotyped and handy for the purpose. The Jews are a favorite stand-in for the child’s “bad-man.” The transference of conscious fear to the particular object, however, the latter being of a secondary nature only, always maintains an aspect of accidentalness. Thus, as soon as other factors interfere, the aggression may be deflected, at least in part, from the Jews to another group, preferably one of still greater social distance.

Brutally silenced children had grown up to be both masochistically acquiescent to conventional authority and sadistically inclined toward outsiders. Stabilized by projection and comforting stereotypes, the Authoritarian Personality found relief in hatred. Filled with rage for the lowly Jew or Negro, he stood guilt-free and superior. According to this model, the embrace of stereotypes was hardly a matter of just going to the wrong movie. There might be an accidental quality to which minority was demonized, but once discovered, these became what Adorno called a point of “orientation.” If all evils were the fault of the Mexicans or the Jews, a simple ethical map emerged that made the source of many troubles clear.

Adorno emphasized something psychoanalysts knew: the rewards of hatred could be so compelling that they withstood assaults from reality. The prejudice against miserly Jews survived all the direct encounters with kind, generous Jews. Echoing Melanie Klein, Adorno noted that bigoted respondents made exceptions for the good Jew. Still, they were the exception. And so their hatred lived to define another day.

The model Adorno and his coworkers pieced together expanded on more limited notions of stereotypes or projection. This theory could not be accused of psychological or sociological reductionism, for the contributors worked hard to make room for each. And their conclusions were alarming. Education or increased contacts between groups was not enough. “Experience is determined by stereotypy,” Adorno warned, and so before such an engagement could be ameliorative, the Authoritarian Personality would need to be undone.

Though sprawling and difficult to fully digest, The Authoritarian Personality was immediately hailed as a “landmark,” unparalleled in its integration of detail and insight. Writing in the Saturday Review, the American sociologist C. Wright Mills called it the most influential work of the decade. Others judged it to be the most complete study of prejudice ever written. In the popular press and academic circles, it was pored over, and soon it generated a flood of new research. It was also subjected to criticism. Wasn’t the “Authoritarian Personality” a crude typology, itself no more than a stereotype? Adorno replied that he was just the messenger: conformist and authoritarian culture made for identical, mass-produced man, ground down by brutal families and flattened by mass culture.

What could be done? To name a problem was hardly to solve it. The Frankfurt thinkers had long critiqued such nominalism as bankrupt. It lacked a dialectic by which it might be held up to critical examination. What personality contrasted with this type? In the Frankfurt studies done in Germany, the opposing character structure was “Revolutionary,” he for whom “the freedom and independence of the individual was the prime goal.” In postwar America, that would not fly. Instead, the group looked to the “Democratic Personality.” Tolerant, quick to accept difference, she was raised not by a rigid patriarch but rather by an emotionally engaged, forgiving mother, who had no preoccupation with dominance and submission. The message was clear: the family, that primal community, needed to be reformed. Society, the authors concluded, did not require a political revolution, but rather a revolution in the home.