Avant la lettre, or The Black Legend

WORDS ARE TOOLS. They do things. What was Rodolfo Lanciani trying to do when he obliquely wrote of xenophoby? What problems did this word name and perhaps even help solve? I began to dig around in earnest, searching archives, newspapers, and databases, and quickly discovered that, much like the assumptions regarding Greek antiquity, the OED had it wrong. “Xenophobia” originated three decades before Lanciani’s essay, but his meaning, the xénos as rival nation, was right on the mark. This neologism first applied to a new, wild kind of patriotic fervor, before it changed shape and took on meaning in the contested geopolitical ideologies of West and East, the never-addressed subtext of Lanciani’s essay.

Before diving into that, however, we need to step back. For if around 1880 there was a moment of xenophobia’s birth, there was a much longer period of gestation, a slow, less-visible process by which the ancient, antithetical assumption that strangers were enemies began to break down. Paradigm shifts, the historian of science Thomas Kuhn argued, do not take place until so many exceptions accrue that they can no longer be explained away. It would require another book to fully explore the many anomalies and slow conceptual cracks that gradually wore away at this presumption. Instead, let us pick up these fissures as they began to widen during the beginning of Western modernity, a period of nation building and expansion abroad, in which the problem of domestic minorities and foreign aliens became increasingly critical. The prehistory of that moral and political peril called xenophobia may be grasped by zooming in on the creation of the very first modern Western empire, for there the dynamics of host and stranger played out in extremis.

The sun never set on the kingdom of Spain. That polity consolidated in 1492 when the rulers of Castile and Aragon linked arms to end Iberian Muslim rule. Before that, for the prior seven centuries, the Moors had overseen a relatively tolerant society in which Christians and Jews were allowed to retain their religious identities. Non-Muslim subjects were not equals; for example, they were required to pay higher taxes. However, they could retain their beliefs and coexist. Centuries of intermingling gradually blurred the lines between groups. Muslim musicians and jugglers performed at Christian festivals; Jews and Christians took up the Arabic tongue. During droughts, plagues, and calamities, all three faiths joined forces so as to cover their celestial bases. In Cordoba, Seville, and Granada, denizens practiced what one scholar has called “toleration without a theory of toleration.”

Christian Castilian emissaries ask the Muslim Almohad king to join their alliance

When Ferdinand and Isabella conquered the Moors’ last stronghold in Granada, that changed. Devout Catholic monarchs now presided over hundreds of thousands of Muslims, Jews, and intermixed populations, all of whom were accustomed to religious freedom. At the same time, the conquerors faced challenges from a host of feudal lords. Regions like Asturias, having never succumbed to Muslim rule, saw no reason why they should now cede their autonomy. Catalans, Basques, and others showed a similar reluctance. And so, as the King and Queen raised their red-and-orange-striped flag over the majestic Alhambra, Spain was a nation only in name.

These rulers confronted a central problem of political life: how to unite disparate clans and tribes into a nation, a group with a common past, when in fact such a past did not quite exist. How could they incentivize the many to become one? The Crown quickly trotted out moves from the Roman and feudal playbook; they bribed local lords and sought to curry favor. However, forging one Spain remained dizzyingly difficult due to the many hybrid identities that had emerged under Moorish rule. Numerous Christians and some Jews, during those centuries, had converted to Islam. Would they return to their older faiths? Mozarabs were Christians who, under Muslim rule, retained their faith but adopted Arabic as their mother tongue. Would they now speak Spanish? As for the hundreds of thousands of Mudejares, those vanquished Moors, what place for them existed in what was once their homeland?

Out of a mix of piety and cunning purpose, Isabella and Ferdinand found a solution: by simple edict, they would make the least demographically Christian nation in all of Europe into the purest. Catholicism became the rallying cry of the kingdom; the one Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church would unite many into one. Becoming Spain now meant rooting out enemies of the faith and uniting their otherwise disparate subjects through fear. Their method was not novel; the ancient historian Sallust noted that, as long as the Romans were frightened of a common enemy—in their case, the Carthaginians—they remained united in purpose. Victory and the end of hostilities preceded disaster, as Rome descended into internal disputes and eventually civil war.

In pursuit of a purely Catholic Spain, the King and Queen relentlessly prodded, provoked, and made symbols of the Moors and the Jews, now that nation’s common enemies. These outsiders faced banishment or forced conversions, yet even those who took Christ into their hearts would be forever suspected of having done so just to save their skins. Muslim converts to Christianity, the Moriscos, remained uneasily in Spain for a century before, in 1609, having been suspected of being a potential secret column for the Turks, all 300,000 were expelled. That act of ethnic cleansing found its way into Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote, where Sancho Panza encountered an old friend, that dear Morisco Ricote, hidden among German pilgrims. He was sneaking back home to retrieve the gold he had buried before he fled. Later, Sancho happened upon Ricote’s daughter, who had transformed herself into a pious Catholic. Cervantes played this for comedy, but the anxiety was real. As the girl loudly recited her Hail Marys, who knew what lurked in her heart?

Worries regarding fake converts reached a fever pitch with Spain’s Jews. Even in more tolerant times, Iberian Jews had been periodically targeted by mobs and flash frenzies. During those episodes, many Jews converted, becoming the so-called New Christians or “conversos.” Then, on March 31, 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella issued an Edict of Expulsion: they demanded that all 250,000 Jews immediately depart from Spain. As for the New Christians, they remained but under a cloud of suspicion: how could anyone tell a real converso from a fraud?

Enter the Inquisition. Established in the Vatican during the thirteenth century, the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Spain was invoked by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1478. While other Inquisitions sought out heretics like the Cathars in southern France, the Spaniards focused on the strangers among them, those false converts. Confessions were extracted through gruesome methods such as placing the victim on metallic impaling devices, waterboarding, hanging them by the wrists, placing their heads in a vice, or pulling them apart with the rack. Muslim or Jewish witnesses would be called to testify on the hidden practices of their supposedly “Christian” neighbors, and in the process old scores could be settled. At least 15,000 victims were murdered for their supposed lack of sincerity toward their savior, Jesus Christ.

The centripetal force created by the search for these strangers-within grew, as subversives and subterranean heretics were said to lurk everywhere. And yet, so few visible differences between Iberian Muslims, Jews, and Christians remained after centuries of interbreeding. How might one truly discern those who served in a secret network of infidels, those traitors who—it was said—had wormed their way into the courts, the army, and even the church? Fearmongers suggested that New Christians—like Ricote’s daughter—were poised to destroy the nation’s institutions from within. This was therefore a matter of survival.

Since matters of faith could be lied about, the Inquisitors began to focus on limpieza de sangre, the genealogical purity of one’s Christian ancestors. The nation’s subjects would now be those with pure blood, with clear Christian ancestry. With this new mission, the Inquisition turned its sights from tricky conversos to those Spaniards who were openly Jewish and Muslim. As a tool for nation building, this never-ending witch hunt was both effective and deeply corrosive. It spun wildly and knew few limits. Only the foolish or the very powerful dared to question the excesses of the Inquisition. Well-placed clerics like the Jesuit Juan de Mariana, or that ambivalent Inquisitor, Luis de Páramo, might raise questions, but others who challenged this institution might easily find themselves accused.

By the time Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand died, their strategies of dividing the populace by faith and then bloodlines had transformed Spain. Under their rule, rigid Catholic beliefs created a perpetual process of uniting “us” in our fear of “them.” Once dazzlingly pluralistic and diverse, Iberia consolidated and became the most inflexible of Catholic countries, one that advertised its purity of ancestry, a claim so absurd as to constantly require vigorous justification. Rooting out the hidden heretics and traitors became symbolic, hence always required, eternal, unreal. For centuries, the bureaucratized institution of such cleansing, the Inquisition, shouldered its unending mission. It would not cease until 1826. For its bonfires were not meant to kill merely a few, scattered heretics, but rather the ghostly spirit of a Semitic and Moorish past.

If the Iberian Moors practiced toleration avant la lettre, it could be said that the Spanish nation that followed it provided an example of the opposite. Out of a shared hostility to heretical beliefs, Spain bound itself together. Subjects were to be zealots in the pursuit these national goals. Shared hatred of aliens and enemies pulled a diverse people together. A religiously and ethnically mixed nation embarked on a quest to deny its past and purify its future. If these tasks were partly fantastic and thereby infinite, so much the better, for then the bonds of the nation would never loosen.

AS THE SPANISH NATION consolidated around blood and Cross, their desire to rid themselves of strangers ran into a cosmic-sized irony. For just as Ferdinand and Isabella declared victory over the Saracens and expelled the Jews, their fantasy of Catholic homogeneity encountered millions of would-be subjects who were so different as to be almost from a dream. That year, the Spanish-funded, navigational wizard from Genoa, Christopher Columbus, stumbled upon islands thick with heathens. Reports filtered back across the Atlantic of dark-skinned beings whose world had been unmapped, unknown, unspoken of even in prophecy. If attacks on religious heretics at home led to the torture, exile, and murder of thousands, Spain’s attempts to create the first modern global empire in the New World unleashed mass murder of a different order.

To be fair, no European nation was prepared to take in the nearly unfathomable differences confronted in the New World. For wide-eyed Spanish and Portuguese sailors, tossed between wonder and fear, it seemed as if they had fallen off the edge of the earth. They had set sail for a known destination. And though these were not the Indies, though these were not Indians, the newcomers named them thus anyway, alerting all who could see to the trouble ahead. The discoverers defined this land and these people in a way that signaled the hegemony of their own illusions.

In sources from antiquity or the Bible, in maps that marked Asia, Europe, and Africa, there was no mention of these creatures. Were they even human? Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo wrote:

They have no heads … not like other people. They are so thick-skulled that Christians hold as a basic principle never to hit them on the head in battle so as to avoid breaking their swords. As their skull is thick so is their intelligence bestial and ill-disposed.…

Perhaps this was Atlantis, or maybe Arcadia. A few of Hernán Cortés’s conquistadors, upon spotting the painted beings awaiting them on the coast, scoured their inner map of humanity and concluded these must be wandering Jews. A Dominican scholar, Diego Durán, dedicated himself to showing that these natives were one of the lost tribes of Israel. Columbus first believed that he had stumbled upon a kind of Eden; the natives, he wrote, “are the best people in the world and the most peaceable.” They were the naked children of Paradise, the unfallen. When some rose up against him, he swiftly changed his tune. The inhabitants, he declared, were ugly, bloodthirsty, scheming savages, as well as sodomites, demon-worshippers, and cannibals.

Still, hearing of so many lost souls, all to be won over for Christ, Ferdinand and Isabella sank to their knees and wept. A sacred evangelical mission commenced, but it was quickly overwhelmed by a more mundane one. Tapping the New World’s gold and silver, the homeland became the wealthiest power in the Western world. To make this empire run, however, required a great deal of labor. Here, the counsel of Aristotle would prove useful. Since these barbarians were subhumans, many cited the Greek sage, arguing they could be justly enslaved. Columbus so advised Queen Isabella. However, the Queen preferred not to empower the conquistadors by allowing them to amass small armies of chattel. Instead, she declared that these brown people were her vassals. Legal subjects of Spain, they were not owned by the conquistadors, but nonetheless were compelled to do whatever work their masters demanded.

This did not end the debate, nor did it put a stop to de facto slavery. Driven by the need for bodies to work fields and mines, the colonists continued to press their view that these indigenous inhabitants were intended by Nature and God for servile domination. Enforced labor killed legions. Epidemics of smallpox and other diseases—we know now—did much of the rest. Millions perished.

After Hernán Cortés’s razing of the Aztec kingdom and Francisco Pizarro’s devastation of the Inca empire, qualms began to be voiced about these missions. Were these “just wars” countenanced by the Church? In the university town of Salamanca, the finer points of justice were discussed by legal experts like Francisco de Vitoria. Disturbed by the violence in New Spain, but openly in search of legal grounds by which to protect the empire’s revenue stream, Vitoria equivocated and danced between possibilities. On another subject, he cited Saint Thomas, who wrote, “It is evil, but not so evil that it can never be good.” That might have stood as his motto.

However, even Vitoria was forced to go beyond routine justifications. He did not resort to theological claims or Aristotle, but he sought laws that gave these foreigners some standing. Travelers and traders, he reasoned, had a universal right to freely move about in another country. If they were impeded or restricted from movement or from proselytizing by their hosts, he argued, the newcomers justly could take up arms. This principle, Vitoria well knew, worked for the growing bands of Spanish conquistadors, but it raised questions about power asymmetries that might apply as hosts confronted strangers. Typically, one assumed the strangers were weaker, in need perhaps of shelter or aid. However, what if they were an invading army? One of Vitoria’s students sarcastically asked if it would be unjust for the hosts to impede the march of Alexander the Great and his fellow “travelers.” The Spanish had come to the Americas not as strangers in need of a bed, but as invaders. Should their hosts be morally obliged to entertain them? This question would dog debates over xenophobia.

Meanwhile, the natives of Mesoamerica and the Caribbean continued to die at appalling rates. Finally, the stark conflict between Christian brotherly love and these brutalities became too much. Standing before such decimation, a few priests began to search for the hole in their own morality that allowed for the dehumanization and annihilation of the “barbarians,” “heathens,” and “vassals.” On the island of Hispaniola, some Dominican friars decided they had had enough. On a warm morning in 1511, Father Antonio de Montesinos rose to deliver his Sunday sermon. In the pews, along with the local elite, was Governor Diego Columbus, the eldest son of the man who had named this island after Spain. Montesinos began thundering like an Old Testament prophet. You are sinners, he told them, with no better chance of reaching Paradise than a Moor. For you have grievously waged war on innocents. Did these Indians not have souls? Did they not deserve brotherly love? Then why did the Spanish treat them as cruelly as they did? By what right? The congregation filed out in shock.

That day, an agitated Governor Columbus demanded to meet with Montesinos. He summarily instructed this traitorous, impudent priest to recant on the very next Sunday. A week later, as Columbus and his fellow settlers settled into their seats, they found to their dismay that Montesinos had doubled down on his condemnations. Neither he nor his brothers would give sacraments to anyone who did not immediately free their vassals, he declared. Some in attendance were horrified. Others, like a young landowner named Las Casas, were not moved. The Indians were dying in droves because God wanted them to, he had heard others say, and God would soon wipe them off the face of the earth due to their sinful ways.

BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS was born to the sea. Raised in the great port city of Seville, he was one of the excited locals in the swollen crowd that gathered as Columbus returned from his earth-shattering voyage. The boy watched in awe as sailors paraded by with seven natives, green parrots, fine gold, and masks of stone and fishbone. Swept up by these sights, his father Pedro signed up to accompany Columbus on his next voyage. When Pedro returned, he brought his son a gift, a young black slave. None of this stirred the boy’s conscience. To the contrary, he wanted in.

In 1502, the eighteen-year-old boarded a vessel with his father and crossed over to Santo Domingo. A year later, he possessed a parcel of land with subjugated vassals to work it. He became acquainted with men in high places like Cortés and was there in the pews when Father Montesinos delivered his blistering denunciation. He didn’t care. “Greed increased every day, and every day Indians perished in greater number and the clergyman Bartolomé de Las Casas,” he later wrote of himself, “went about his concerns like the others.…”

At some later date, perhaps after witnessing a massacre of Taino Indians in Cuba, Las Casas became uneasy. He recalled Montesinos’s warning and, after some indecision, freed his vassals and returned home. After a long period of crisis, he finally took his orders as a Dominican priest. From that point on, a tonsured Father Bartolomé de Las Casas, haunted by what he had seen, made it his calling to let all know of the crimes the Spanish nation had committed. He risked the hot irons of the Inquisition to publicly denounce barbarous outrages, justified in the name of the Crown and Christ.

To make this point, Las Casas was relentless. He harnessed the power of the word, describing in vivid, unforgettable detail atrocities and acts of butchery. A reform-minded Dominican, Las Casas adapted familiar language of vice and corruption to make sense of these nearly unimaginable scenes. Analogies of rot and venom flowed freely from his pen. Still, the massacres in the New World beggared his capacities. There were no words that captured the easy demonization of other human beings, or the wiping out of whole tribes. He struggled to communicate the scope of these tragedies, the fields of the dead, this Gomorrah of sin. “Who will believe this?” he wrote. “I myself an eyewitness writing this, I can hardly believe it.”

As later commentators would note, he freely exaggerated and then, perhaps out of frustration, latched on to a symbolic reversal, one that would force his self-righteous readers to freeze in their tracks. God and goodness dwelled among these natives of the Americas. Kind and Jesus-like, they were worthy of full assimilation into the Spanish nation. However, the so-called Christians—who, according to Las Casas, included criminals whose sentences had been dismissed in exchange for service in the New World—were diabolical savages. “I left Christ in the Indies,” he wrote, “not once but a thousand times beaten, afflicted, insulted and crucified by those Spaniards who destroy and ravage the Indians.”

As for “just wars,” Las Casas could barely contain his disgust. Since the days of Pope Innocent, the Vatican had forbidden military actions based solely on political or religious differences. There was, however, one loophole. A just war could be waged in self-defense or to combat the biblical sins of idolatry or sodomy. Thus began the odd habit throughout the history of Catholic warfare, of highlighting the enemy’s supposed sexual proclivities. After his ascension in 1516, Charles V in Spain added a critical proviso: only those captured from a “just” war could be enslaved. For a war to be just, a 1513 document known as the Requerimiento had to be recited, in which the natives were offered the chance to immediately submit to both the Pope and the King of Spain. When the natives did not promptly agree, a just war commenced.

Las Casas didn’t know whether to laugh or cry at the absurdity of this public reading, proclaimed in a language foreign to the listeners, made by a gang of “cruel, pitiless, and bloodthirsty tyrants.” At times, these robbers, in the dead of night, leagues away from a sleeping village, dutifully read the Requerimiento before commencing their pillage. Even if the locals had heard and understood this proclamation, was there a nation on earth, he asked, who would not act as the Indians did when ordered to summarily relinquish their king and God? Las Casas dismissed Aristotle and the Pope, so as to ask his reader to look inward and consider whether the natives’ actions were different from anyone else’s. The ones fighting a “just” war, he bravely concluded, were the Indians who acted in defense of their families and their lands.

Illustration from Las Casas’s A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, 1552

Over the course of two decades, Las Casas furiously attacked the assumption that these New World strangers were Spain’s enemies. They were more moral than his own tribe. And over the years, his advocacy only grew more militant. Guiltily, he also repented for an earlier sin; he had supported bringing in African slaves to the Spanish colonies, in the hopes that they would save the weakened, decimated Indians. In retrospect, he recognized that this was a despicable act of complicity, an ignorant utterance, and perhaps unforgivable in the eyes of God. In penance, he redoubled his attacks on the brutal regime his nation had instituted abroad.

Somehow, Las Casas was allowed to keep up this crusade. Scholars have suggested that the King did not mind challenges that kept his restless, far-off colonists on their back foot. Furthermore, the Dominican had won favor in high places. In 1537, when Pope Paul III declared that the Indians were fully rational beings, some discerned Father Las Casas’s fingerprints on the decree. In 1550, the priest also took part in an epochal debate staged before King Philip at Valladolid. There he took on, among others, Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, a distinguished lawyer who, despite never having traveled to the New World, confidently rolled out Aristotle’s notion of natural slavery. While there was no official victor, only Las Casas’s arguments were printed in the official proceedings.

In 1552, Las Casas cemented his legacy with the publication of A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. “Everything that has happened,” it began, “since the marvelous discovery of the Americas … has been so extraordinary, that the whole story remains quite incredible to anyone who has not experienced it first-hand.” As the reader readied for exotic delights, he quickly discovered that what was nearly impossible to convey were Spanish “massacres,” “atrocities,” and “horrific excesses,” which annihilated “whole kingdoms.” Las Casas hammered this home: our nation has been the enemy of righteousness. We met the “simplest,” kindest people, and what did our countrymen do? “They hacked them to pieces,” he wrote, “slicing open their bellies with their swords … they grabbed suckling infants by the feet and, ripping them from their mother’s breasts, dashed them headlong into the rocks. Others, laughing and joking all the while, threw them over their shoulders into a river.…” If that was not grisly enough, he went on to describe how the Spaniards hanged and burned thirteen victims at a time, in honor of Jesus and his apostles, taking sadistic pleasure in binding them in a griddle of wood, so as to “grill them over a slow fire.” When images and language seemed to fail him, Las Casas grasped at numbers. After forty years of Spanish occupation, he estimated that twelve million natives had perished. Of three million pre-Columbian natives on Hispaniola alone, Las Casas reported, two hundred remained.

All this slaughter had been lost on the moral imagination of the West, the Dominican concluded, due to a confusion of identities. Spanish Christians were supposed to possess virtue, reason, and civilization; the indigenous strangers were enemies of all that was right and good. In truth, we were “ravening wolves” who devoured these lambs. The Spanish colonist was “like someone out of his mind and gone crazy. His mind is not his own, it is enveloped in clouds.…” “Such a type,” he continued, “is hardhearted, merciless, does not have faith, does not love peace, lacks love.…” Pointing to Saint Paul, he protested that these beings were also merely “strange in ways of speaking.” They were God’s children, while the subjects of the king were savages.

A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies infuriated the conquistadors. Gentle, kind Indians? Cortés scoffed in widely published letters that emphasized the Aztec practice of human sacrifice. Bernal Díaz, one of Cortés’s men, described Montezuma’s priests striding by him in a trance, their hair wild and stiff, caked in human blood. These natives smiled, he reported, but were ever ready to snatch out your heart. Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda went further: he argued that Spanish domination was just, for the conquerors were saving natives from homegrown tyranny and the sacrificial altar.

These rebuttals may have forced Las Casas to rethink his initial idealization of the natives and strive for a more complex, less Manichean position. What if we looked past tribal or national labels? What if we judged all inhabitants in the New World equally? What if only one standard applied? The Aztecs revered their God; they were devout, law-abiding men and women whose sacrifices showed that they passionately worshipped the divine. Such devotion made them more religious than most Spaniards, whose hunger for lucre drove them to heinous acts. As for human sacrifice, Las Casas did not hesitate to condemn it as a monstrosity. Still, this rite paled in comparison to the extermination of whole peoples.

With that, the Dominican’s moral journey landed him in a startling place. Who was “barbarous” and who was “civilized” seemed to depend not on sharing the same God, tribe, nation, or heritage but simply on one’s actions. The same moral principles could be applied to everyone. This breathtaking conclusion went against the powerful dividing practices that had long unified Spain. Everyone should be judged by the same principles; therefore, strangers were not necessarily the enemies of righteousness. We, the Christians, may be. Las Casas thus began to consider a moral system that applied to devotees of any religion. All this from a Dominican who never wavered in his own conviction that there was one true God, that Jesus Christ was his son, and that in that final hour, He would judge all.

Las Casas had no single word for the blood-crazed degradation that his kinsmen had perpetrated upon these New World strangers. Instead, he deployed hundreds of words strung together into a scream. Readers found it hard to look away from the lurid, stunning set pieces he created; they broke the heart of even the stoniest reader. He used the Christian language of universal souls and mortal sins against the Spanish, and brought to life a monster, the Great Goddess of Greed. Gold, silver, and self-interest led to the desire for more, more, and more again. Material lust drove his nation to treat these innocent strangers like devils and, despite a bloodbath, nary a soul protested.

“A MIRROR DOES NOT develop because an historical pageant passes in front of it,” wrote the novelist E. M. Forster. “It only develops when it gets a fresh coat of quicksilver—in other words, when it acquires new sensitiveness.…” Bartolomé de Las Casas applied a layer of reflecting paint onto the ideologies that made violence against strangers legitimate. He questioned the assumption that the foreigners were to be feared and hated, and declared that by labeling these strangers as subhuman, his own people had granted themselves license to do whatever served their own interest. By undermining the assumed righteousness of his own tribe, he opened up the dizzying possibility that ethics should not be distorted by tribal identity. Thus Las Casas became a central figure in an emerging modern ethic that, over time, would see such justifications as xenophobic.

Las Casas broke through a cordon sanitaire of prejudices that defended Imperial Spain from examining its self-defining practices in the New World. He forced his readers to reflect on a national identity so rigidly tied to a fantasy of blood and purity that it sanctified crimes against others. After flipping the equation and declaring the New World inhabitants to be good and his own tribe to be evil, he moved past that. Applying an impartial moral calculus, Father Las Casas concluded simply, ye shall know them by their acts. By that criteria, those who ritually sacrificed and ate humans were still more virtuous than his brothers and sisters who had laid waste to whole nations.

Publication of A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies led to Las Casas falling out of favor at home. Around Europe, however, newly created printing presses rushed out his revelations, accompanied by gruesome illustrations. Thus began what became known as the “Black Legend,” a condensation of Spanish history into hooded inquisitors and bloodthirsty conquistadors. For some two centuries thereafter, it stood as a stark warning of bigotry run amuck. Rivals like the French, the British, the Dutch, and the Germans used the Black Legend to distinguish themselves from their southern rivals. Protestants took Spain to be the prime example of Catholic zealotry. When the English sent Sir Walter Raleigh out to create a colony in the New World, each of his men received a copy of Las Casas’s book, which was intended to convey to the sailors and all they met that the English were not the Spanish.

The problem, however, was hardly restricted to Spain. Las Casas’s message filtered out into a Europe torn by its own wars of religion. In 1619, the new Holy Roman Emperor rescinded laws protecting religious freedom and decreed that the realm would be Catholic alone. Bohemia revolted, as did many other Central European Protestant nations. These battles were then joined by Sweden, France, Belgium, Spain, and England. During thirty years of war, death prospered. In 1648, all the inter-Christian killing finally ceased with the Treaty of Westphalia.

The philosopher Georg W. F. Hegel proposed that history moves in pendulum swings, as thesis is met by antithesis. Over the next decades, these dark chapters of the persecution of minorities at home and slaughters abroad can be seen as engendering such a reaction. After reading critics of the Spanish empire, the Frenchman Michel de Montaigne, in a famed essay on cannibals, summoned Saint Paul and wrote, “each man calls barbarians whatever is not his own practice.” Beyond such sheer relativism, a politics and ethics was needed that did not descend so easily into rank prejudice. In search of that framework, early modern thinkers turned to two related principles: radical egalitarianism and toleration.

A central architect of these views was the doctor, political operative, and philosopher John Locke. Raised as a Calvinist, Locke was nonetheless distressed by the “I heard it from God” insurrectionists he encountered during Oliver Cromwell’s reign. He struggled to find a rational basis by which the state would make way for differing faiths, while outlawing dangerous sects. God and natural law had created all human beings as equals, he believed, but could he justify this? The doctor and philosopher spent the next twenty years doing precisely that, and in the process inaugurated the Western notion of a natural, fallible, brain-based mind.

Understanding, for Locke, commenced at the same starting place for all humans. The mind began as a blank slate, then built up an associative web of knowledge from sensory inputs and memory. That meant human understanding was always partial and contingent, never more. Since absolute truths were unknowable, the state had no right to limit the liberty of others. Strange, even repugnant beliefs, as Locke wrote in his famous letters on toleration, needed to be accepted, as long as they did not threaten others or the state.

In 1688, the Glorious Revolution enshrined Locke’s credos and solidified a place in the public square for strange faiths that differed from the official Anglican Church. Religious groups, even those commanded by “fanatical enthusiasts,” were allowed to pursue their beliefs. Quakers, Lutherans, Calvinists, Diggers, Levelers, and more would not be defined as outsiders or enemies. Even if these religions might seem to be “false,” even if the followers might resemble the Devil’s spawn, diverse religious minorities would be politically accepted. Liberal toleration demanded that in contradistinction to the Spanish Inquisition, nations accommodate an array of dissidents who were, in their minds, capacities for knowledge, and essences, nothing more or less than equal.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as the secularizing Enlightenment gathered momentum, radical egalitarian tracts and disputations on toleration flourished. When in need of a powerful example of error, they often employed the Black Legend. François-Marie Arouet, famed as Voltaire, turned to Las Casas to help his readers grasp the nature of intolerance. The cries over Aztec human sacrifice were a smokescreen, he concluded, much hyped to cover up the greater crimes of the Spanish Catholics. Baron de Montesquieu also used the Spanish Conquest to make his point: he depicted Cortés as a hypocrite who spoke of freedom and justice while committing barbarities, and he pressed forward a daring position. Differences between the French and the Aztecs were not intrinsic. What one man or woman believed simply came, following Locke’s psychology, from local inputs. Humans were equal; only in their cultures did they differ.

In 1770, many of these Enlightenment strands came together in the first Western history of colonialization. Published anonymously in Amsterdam, the book became one of the most avidly read works of the time. A Philosophical and Political History of the Settlements and Trade of the Europeans in the East and West Indies, despite its heft, ran through fifty French, fifty-four English, twenty-nine German, fifteen Russian, and eleven Italian editions. Readers gobbled up accounts of far-off members of their species who lived so differently that it was hardly imaginable.

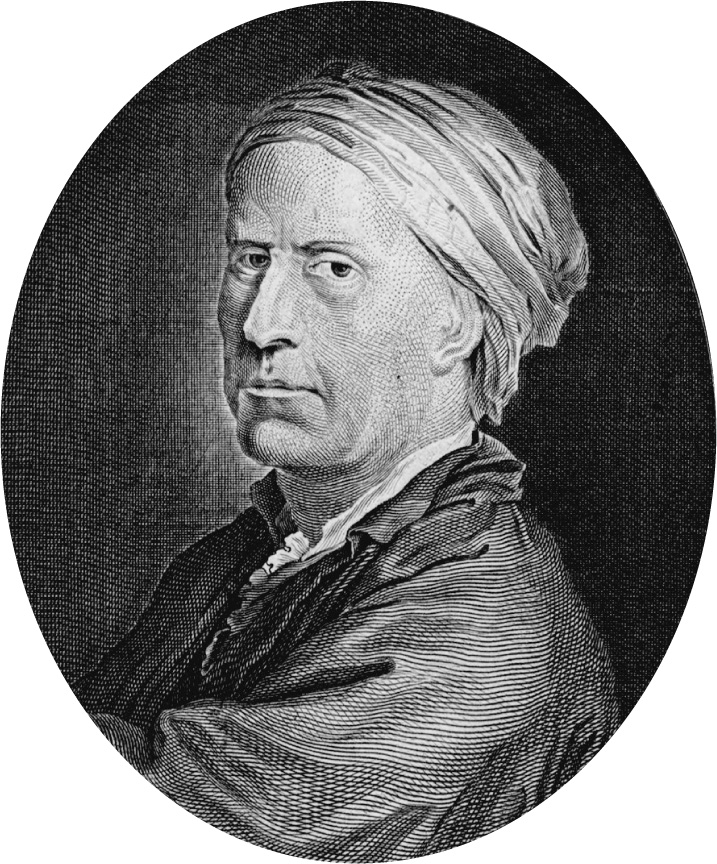

The author was Abbé Raynal, though he was no priest. Educated by Jesuits, Guillaume Thomas Raynal left the church to become a journalist and editor in prerevolutionary Paris. The immense success of his anonymously published six-volume magnum opus must have thrilled him, until his identity was leaked. As sales skyrocketed, the Catholic Church banned his book, which guaranteed continued success on the black market and Raynal’s exile. Somehow his clandestine collaborator, the brilliant polymath Denis Diderot, remained undiscovered.

The discoveries and conquests of the Dutch, English, and French each warranted one section in this work. The Spanish required three, and within them the authors were scathing. The conquest of the New World demonstrated the mad extremism of both the Catholics and the Aztecs. Religion was a universal source of zealotry, a prescription for seeing others as fallen and demonic. To pound home this point, Raynal and Diderot turned to their hero, Bartolomé de Las Casas, who:

summoned his nation to the tribunal of the whole universe, and made the two hemispheres shudder with horror. O Las Casas! Thou were greater by thy humanity, than all thy countrymen by their conquests. Should it happen in future ages, that these unfortunate regions which they have invaded be peopled again, and that a system of laws, manners and liberty should be established among them, the first statue that they would erect would be thine. We would see thee interposing between the American and the Spaniard, and presenting thy breast to the dagger of one, in order to save the other.

Guillaume Thomas Raynal

Natural law established human equality and freedom from tyranny, these philosophes believed, and as Western nations spread out to foreign lands, this meant that toleration must be exercised, even with very strange strangers. Only in that way could one transcend subjective prejudice, think and judge and act free of one’s biases. Raynal and Diderot called for a new dawn, in which these secular morals would hold back prejudice and make space for an array of foreigners, all of whom in their essence were equivalent.

Raynal and Diderot were not just utopian dreamers; they were among a chorus of radical prophets. Only six years after their book appeared, a revolution took place and the American Declaration of Independence enshrined these same beliefs. Thomas Jefferson returned from France, took out a quill, and wrote: “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable, that all men were created equal.” It was a good start. He passed his draft on to Benjamin Franklin, who crossed out “sacred and undeniable” and inserted “self-evident,” an irreligious phrase that took its authority from what was natural. And so, the ringing first words of this document insisted that a rejection of universal equality was bigoted, deluded, and false.

A secular ideal was being born in which a tolerant nation-state, predicated on universal human equality, might resist the easy demonization of inner and outer strangers. In the beginning, though, the only ones to be tolerated in fact were odd, weird, or deviant white freemen. Yet, even if the American founders wished it to be so, their hymns to liberty, equality, and toleration could not be so easily confined. These uplifting proclamations would be taken up in revolutionary France’s 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. They would inspire the first successful revolt by enslaved peoples, who in 1791 rose up in Saint-Domingue. In 1787, the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in Great Britain, and in 1794, the French outlawed slavery. Throughout Europe, Enlightenment reformers began to call for the civil emancipation of Jews.

Over the next century, promises of equality and toleration would rise, recede, and need to be renewed. For the powerful forces that led to the demonizing and degradation of strangers did not disappear. In the coming contest of ideas, however, there were new tools by which one could fight. “Zealots” and “fanatics” practiced “intolerance,” and in so doing, like Cortés and the Inquisitors, they committed crimes. To be intolerant was no longer just an idle accusation; it pointed back to horrifying histories of persecution and murder. A tradition now linked the poet of Hebrews and Saint Paul’s Letters to the Corinthians to Father Las Casas, Michel de Montaigne, John Locke, Denis Diderot, Abbé Raynal, abolitionists, and more. As partisan quarrels and conflicts repeatedly ignited, some would take a stand, placing themselves among Las Casas’s progeny, as they demanded that Westerners consider an expanded moral community, one that did not stop at national or religious borders and therefore did not restage the tragedies of the past.

BEFORE THE TERM “xenophobia” made its first appearance in the 1880s, what had been learned from the first modern European empire and its trials? The first lesson was that the dehumanization of strangers thrived on ignorance. Barbarism, following Saint Paul, might be due to the inability to comprehend each other. When Columbus approached “India,” the ocher-painted, pierced figures before him were unfathomable. This stoked fantasies and fears. However, when linguistic barriers fell and customs were decoded, a commonality could emerge. The shipwrecked Spaniard Cabeza de Vaca, having lived in the wilds with different American tribes, came to view these natives as not essentially different from his own people. They could be violent and gentle, greedy and generous, duplicitous, cruel, sensual, and warm.

However, for those who believed reason and knowledge would one day make the world sing together in harmony, there was a second problem. In Spain, the Moriscos and Jews were very well known to their fellow countrymen; they were friends, trading partners, lovers, and relatives. Urged on by the divisive strategies of their leaders, Catholics nonetheless began to consider Habib and Saul as dangerous Moors and Jews. Intimate knowledge and human contact was hardly the problem. Driven by the mandates of their monarchs, citizens came to be defined as internal strangers and enemies. The staying power of the Inquisition proved that within groups, leaders could endlessly stoke uncertainty about one’s safety and status, and thereby encourage scapegoating. The robed hunters of difference compelled many to secure their place among a symbolic “us” by turning on “them.”

Liberal toleration worked to unite heterogenous members of a political community around the acceptance of differences that did not threaten the state. If enshrined, toleration could act as a dam against the sins of tribalism. However, there was a third problem. Somewhere in the darkest corner of humanity, a force lurked that yearned to dominate others. For Las Casas, beneath the absurdity of the Requerimiento stood the heathen Great Goddess of Greed. Lust for lucre hid, but it bullied logic and coolly plotted out its crimes. Legal contests in Salamanca might weave around fine points, but the conclusion was predetermined: we need free Indian labor because we want silver and gold.

This same dark force marred the founding of the United States of America. While the writing of the Constitution declared that each citizen had an unalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, this stirring call contained a nearly fatal contradiction. Advocates of equality and liberty—heroic figures like George Washington, James Madison, and Jefferson himself—perched between self-interest and their own moral imaginations, choose the former. In this newly born nation committed to universal equality, other self-evident truths existed: they included seven hundred thousand enslaved African Americans, uncounted thousands of dispossessed Native Americans, and fully disenfranchised women.

During the writing of the Constitution, the question of how to declare war on inequality while perpetuating it nearly derailed the entire process. With evident disgust, abolitionists could not prevail on the others to outlaw slavery. Heated debates ensued over whether shackled Blacks were people or property. Were they to be represented or taxed? This debate ended in sick absurdity, when James Madison’s three-fifths compromise counted enslaved Blacks as that fraction. Then despite rancorous debates, the whole matter of slavery was hushed up and simply left out of the Constitution. A representative from Pennsylvania, John Dickinson, wrote: “The omitting the Word will be regarded as an Endeavor to conceal a principle of which we are ashamed.”

The forces that led to the Black Legend of Spain had hardly died. Ignorance, tribal bigotry, and lust for power continued to trouble the sleep of egalitarians and those committed to toleration. However, for late nineteenth-century thinkers distressed by such questions, Las Casas’s universal moral ruler, Locke’s liberalism, Raynal’s rich history of misdeeds, and the French and American revolutions, all acted as coats of quicksilver that enhanced the mirrors by which individuals and nations might examine themselves. In these ways, they might reflect upon their successes and inevitable failures, for despite all these efforts, the armies of division had hardly been vanquished. Instead, they had merely changed their names.