THE MOST INFLUENTIAL physician to ever preside over Western medicine observed that a man bitten by a rabid dog developed a raving form of madness. During the second century of the Roman Empire, Claudius Galenus wrote that “hydrophobia” was heralded by a frothing at the mouth and a bizarre aversion to water. So the “phobias” in medicine began, and as Galenic medicine reigned, there they remained. Around 1800, however, that limited notion of pathological fear changed gradually then all at once.

Soon after the French Revolution, an entirely new class of phobic troubles appeared. During the Jacobin Terror, Philippe Pinel, the French founder of “mental medicine,” noted that some of his traumatized patients suffered from a nervous state akin to canine madness. It too was marked by a foaming fear, but his patients’ troubles were preceded not by a dog bite, but rather by a sudden, violent emotion. Alienists began to follow the influential Dr. Pinel and refer to these patients, with their agitation, shortness of breath, and tight throats, as cases of “nervous hydrophobia.”

That was the first crack. After 1850, as more nervous specialists left the hospitals and opened outpatient offices, they happened upon many outwardly normal citizens who secretly suffered from what was called, among other things, anxiety, Angst, obsessions, morbid fears, and deliriums of doubt. In 1871, phobia would be added to that list, when the German alienist Carl Westphal wrote of a gentleman who came to him with an overwhelming terror of open spaces. The doctor suggested that this state was best named by combining the Greek word phobos with the prefix agora, the place of public assembly in ancient Athens. And so “agoraphobia” was born. Eight years later, another physician published a case report of an otherwise healthy fellow who became giddy and confused in narrow spaces. Grabbing a Latin prefix, the doctor dubbed this “claustrophobia.”

All of a sudden, a swarm of phobias seemed to menace the populace. Doctors reported cases of zoophobia, hematophobia, toxophobia, syphilophobia, monophobia, and phobophobia, the fear of being frightened. Demonophobia may have seemed silly to some, but what of theophobia, the fear of death? Anxieties revolving around contamination joined social phobia, gynophobia, and, lastly, pantaphobia, a terror of everything. In this gathering of great frights, the neo-Grecian compound term “xenophobia” made its debut. Roget’s Thesaurus listed “xenophobia” as a synonym for “repugnance” and cross-referenced it with “hydrophobia” and “canine madness.” Its cause—a violent shock or some strange inheritance—never was clear. Still, the term found its way into Thomas Stedman’s influential medical dictionary, defined as the “morbid dread of meeting strangers.” A quarter of a century later, Richard Hutchings’s psychiatric dictionary still listed xenophobia among its list of seventy-nine phobias.

Xenophobia, like most of Hutchings’s seventy-nine morbid fears, would have no future in medical discourse. By 1900, skeptics had begun to roll their eyes at this naming furor. Either phobias were a new plague, some said, or the physicians themselves were worked up into some frenzy. When a patient presented with a new dread, someone grabbed hold of a fancy prefix, added “phobia,” and presto, a malady was born. Some synthesizers, including Sigmund Freud, suggested these maladies were mostly symptoms of a very few underlying illnesses. Another commentator dryly noted that the number of human phobias seemed limited only by the Greek dictionary. He was being kind. There were also lots of choices from Latin.

As xenophobia splashed then sank into medical obscurity, it simultaneously bobbed up within political discourse. Around 1880, anonymous journalists in the British and French press began to describe an extreme trouble called xenophobia or xénophobie. From London and Paris, this expression spread, carried forth during the heyday of newspaper publishing.

During the last years of the nineteenth century, readership skyrocketed as hundreds of dailies and weeklies sprang up, thanks to increased literacy, decreased censorship, technical advances in printing, and telegraphic lines that ran under oceans. Centralized press agencies like Reuters emerged as nodal points for gathering and dispersing stories from abroad. During this fertile age for print journalism, xénos was linked to phobos, in a manner that might seem to be associated with medicine and science, but in reality had little relation to them. Instead, it made sense of a new kind of political antipathy, not so much the religious zealotry of earlier times, but a malady called “nationalism.”

After the American and French revolutions, as well as the Napoleonic wars, many nineteenth-century Western nations gradually altered their makeup. Once feudal European states secularized and adopted more republican values, by which sovereignty was vested in the people. Weakened traditional elites and religious authorities, once wielding the crown and cross, could no longer as effectively use such time-honored methods to ensure social order. Into this vacuum, nationalism emerged with different self-defining strategies intended to cement the commitment of the citizenry.

A state is a bounded geographic and political entity, but a nation may be little more than a shared group of ideas. While these might seem parochial, overvalued, or arbitrary, a firm commitment to them was lauded by that seminal, Counter-Enlightenment thinker, Johann Gottfried von Herder. Against the universal principles carried forth by Napoleon’s invading armies into Germanic lands, against abstractions like liberty, fraternity, and equality, this friend of Goethe sought to protect, preserve, and invest pride in one’s own nation and its mother tongue. A brilliant, wide-ranging thinker whose work on linguistics and anthropology would be seminal, Herder took a stand for the local cultures that he believed were menaced by French edicts. He defended the Germanic adaptations and solutions that made up their culture. Thus for Herder, national identity was founded not on natural law, philosophy, or ethics, but rather on history. It took shape from common customs and beliefs, and a body of defining stories. National unity and pride were supported by public monuments, the hoopla of rousing anthems, flags, festivals, shrines to the dead, and commemorative holidays. All this boosted the nation as the focus of individual loyalty and sacrifice, in places where the princes and priests were in hiding, and the populace was said to be king.

If patriotism and pride of place were sound results of these efforts, nationalism also found its way into the dark political arts. By undercutting the universality of Enlightenment principles, nationalism could be used to justify oppression, inequality, and division, and it had the power to unleash conflict based on hyped-up differences with other nations. That was a chronic problem, but also an advantage, since national enemies made even a quarrelsome, divided community sacrifice their young, pay their taxes, and remain closely united. Such rivals were best if irredeemable, thus available to be invoked at any time. Newly constructed national identities were especially likely to stabilize themselves by pitting a “unique” national character, just the way we are and always have been, against those of a rival. Minor discrepancies could be made immutable, essential. Ancient massacres and battles could be cultivated, taught to the young, and repeated in days of remembrance. Old wounds could be pried open and never allowed to heal.

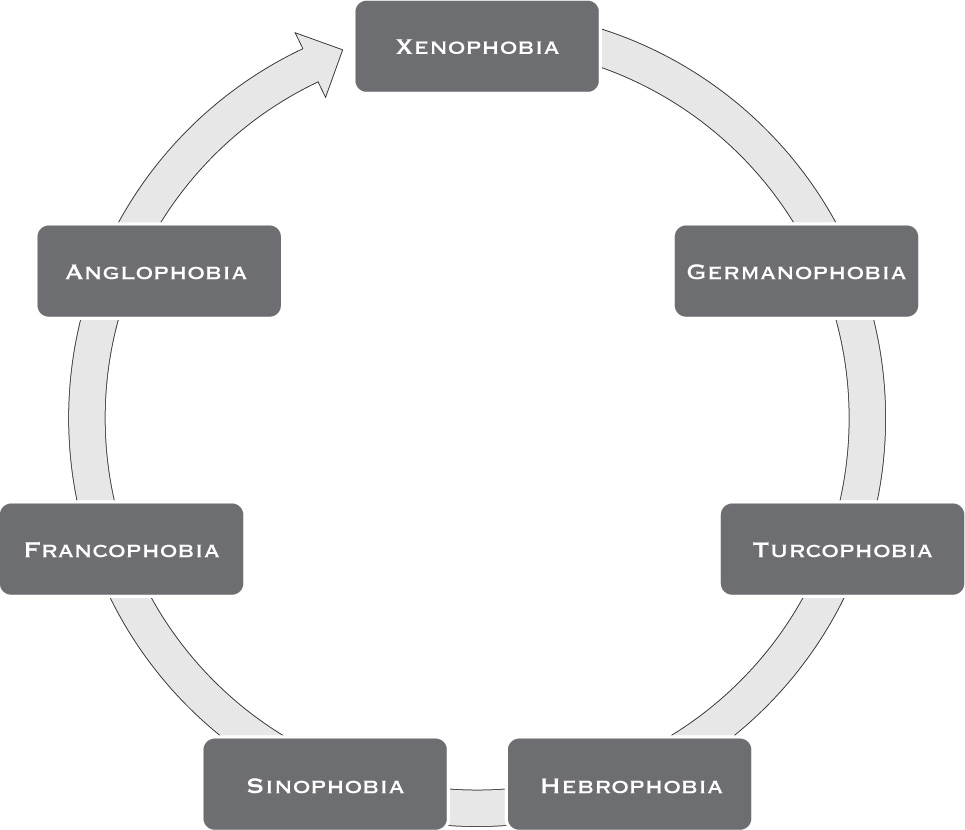

Such nationalist strategies proved to be potent, so much so that they risked spiraling out of control. Alarmed, commentators began to discuss the risk of stoking these embers. Take, for example, the burning hatred that existed between the British and the French. At war on and off for five hundred years, these nations during the nineteenth century were said to be ill. Londoners worried that France harbored many “Anglophobiacs” or “Anglophobists.” On other side of the Channel, French journalists commented on their readers’ ravenous appetite for anything that fed their “Anglophobia.” They wondered if the British public had equally succumbed to “Francophobes.”

Patriotic zealotry began to be referred to as a “phobia.” Given its position as the most dominant power on the globe, Great Britain was said to be the most popular target for such a wild animus. In 1793, Thomas Jefferson told James Madison that he worried his fellow former colonists harbored an irrational “Anglophobia.” Others concurred and noted that a near “delusional” Anglophobia had swept through the United States. Educated readers in London were bemused by the “illogical animosities” of the Germans, said to be nothing more than their Anglophobia. Fretting about such trouble was so common that it became ripe for humor. In 1845, Littell’s Living Age announced that Englishmen suddenly were in fashion in Paris; Anglophobia mercifully had been replaced by “Anglo-indifference, if not Anglomania.”

These phobias called attention to the demands that European nationalism placed on its members. And by 1870, the field of national phobias had grown more crowded. Heated rivalries led journalists, scholars, and diplomats to routinely claim that fair-minded, rational political dialogue had been supplanted by “Francophobia,” “Germanophobia,” and “Russophobia,” not to mention “Austrophobia,” “Sinophobia,” and “Turkophobia.” In addition, there was a phobia for that supposed nation of wanderers, a “Judeophobia” or “Hebrewphobia.”

As discussions of national prejudices mounted, an even more menacing distemper stepped forward. Some nations were so deeply hostile to rivals that they targeted all other nations. “Xenophobia” described such an overheated hatred. Extreme but mercifully rare, “xenophobia” was the most vicious form of ultranationalism. An early, revealing use of this anonymously coined term occurred in 1880 during a visit to London by the ardent Frenchman, Ernest Renan.

Born in 1823, Renan was a diligent, provincial boy who seemed headed for the priesthood. He excelled in his seminary studies and developed a passion for the Hebrew language, which he told his mother “holds the greatest charm for me.” A sensitive young man, he could feel the spirit course through him as he translated Solomon’s Song of Songs. He expanded his study to other Semitic languages at the Collège de France and became deeply immersed in philology. This, however, led to a profound crisis. Renan was dismayed to find that mistranslations of Hebrew guided certain matters of Catholic faith. Stung and shocked, the sincere youth forever renounced the Church. As a friend wryly observed, he “gambled his life on a comma.”

Renan turned his considerable energies to the Near East, Semitic languages, and the history of religion. In 1855, his General History of the Semitic Languages led him to offer a conclusion not just about these languages but about the “races” that created them. With evident pride, he proclaimed: “I am then the first to recognize that the Semitic race, compared to the Indo-European race, actually represents an inferior combination of human nature.” For that achievement, he would also be dubbed the first “anti-Semite.”

Five years later, the French government sent Renan on an archaeological expedition to Lebanon, a trip he undertook with his wife and his sister Henriette. The pilgrimage was life-altering. Inspired by the sights and smells of the Holy Land, Renan began to write a popular history of Jesus Christ. The project, though, was tinged with tragedy, for the originator of this idea, his sister, succumbed to malaria in the seaside town of Amchit. After returning to France, Renan published his biography of Christ, that “incomparable man.” Man? His Life of Jesus was swiftly denounced by the Church, and following that well-worn path, it became a bestseller.

After France’s humiliating loss to the Prussians in 1871 and the chaotic rise and fall of the Paris Commune, the once liberal Renan became a devout nationalist, an authoritarian, and an advocate of foreign conquest. France must become a colonial power, he declared, or it would descend into civil war. It must spread la richesse of being French. This was the Ernest Renan who arrived in London to deliver the Hibbert Lectures a decade later. By then, the traditional enemy of the English, the French, had established an empire that was growing at a staggering rate, and Ernest Renan was rightly considered a zealous nationalist.

Ernest Renan

Despite all that, Renan’s lectures in London were mobbed. To win the crowd over, he used flattery, telling them that England had established the one dogma that “our society” should always hold: “Liberty, respect for the mind.” He then launched into his history of Christianity, singing the praises of the Savior who rose above Judaism—a religion far too “primitive” to ever become global. He piled contempt onto Rome and the Pope. And then he departed, bathed in British adulation. The Daily News, stunned by Renan’s popularity on British soil, called it a “xenomania.” This stance, they added in what may have been a dig at the French, was always preferable to “xenophobia, which is of necessity and always unintelligent.”

A few years later, the Saturday Review, a London weekly, scolded those afflicted by an unthinking fear of and hatred for foreign nations. Discussing the many, shifting alliances in the Balkan states, an author was dismissed as both a rabid “Turcophobe” and “Austrophobe,” but even this bigot, the reviewer declared, was more tolerant than the Bulgarians. That nation harbored a distaste for all kinds; it suffered from “xenophobia.”

Xenophobia, for some, seemed to be nationalism gone utterly mad. Or was it the foundation beneath all the specific national biases? The French Baron d’Estournelles de Constant, a future Noble Peace Prize winner, believed it was the latter. He wrote: “before being Germanophobe,” the warmongers “were Anglophobe and Russophobe,” that is, always “xenophobe or demophobe.”

Such irrational loathing was not unlike those described by the medical men, only this time the illness struck whole nations. If the nation offered a powerful framework for identity—I am English, I am French, I am German—if it puffed itself up with ceremonies and song, it also might whip up fright and dislike for foreign nations, perhaps all other nations. The French sociologist Gaston Richard wrote: “It is only for the rhetoricians that modern patriotism, that attachment to national territory, resembles that of the Greek or Jewish zealot, a patriotism which, like the nationalism of our amiable contemporaries, was less altruism than xenophobia, the sacred hatred of the Impures.”

TABLE 1: NATIONAL PHOBIAS

One of the most influential thinkers to contemplate such risks was none other than the same Ernest Renan. In 1882 at the Sorbonne, he delivered a widely circulated lecture entitled “What is a Nation?” While some equated the nation with one’s bloodline and race, Renan—despite his own bigotry—rejected this as absurd. What race made up France? Celtic, Iberic, and Germanic, and more. No, the most noble nations were of mixed heritage and “mixed blood.” Purity of religion, ethnicity, and language defined no nation. Large, successful nations glued together multitudes. Diverse populations—Goths, Normands, Franks, Lombards, Catalans, and others—were fused into one, the French.

Across the Atlantic, the African American orator extraordinaire, Frederick Douglass, had made a similar case for a “composite nation,” one whose citizenry included Chinese immigrants, with “the negro, mulatto and Latin races,” offering all full citizenship and benefiting as a result. However, in such a composite, what was the glue that held everyone together? If states had geographic borders, what boundaries defined a nation? Nations, Renan declared, were not racial or hereditary, but man-made. A national community bonded over a set of remembrances, but perhaps more importantly, shared amnesias. Everyone would thereby inhabit the same memory-scape. They could recount the glorious and heroic legacy of their forebearers, and stare blankly ahead, when mention was made of episodes better left forgotten. Nations were forged by willful acts of communal imagination. Resting on such a foundation, nationalism fostered common goals for the future and encouraged anger and mourning for well-selected grievances and traumas. Of these two forces, Renan admitted, “griefs are of more value than triumphs, for they impose duties and require a common effort.”

Omelettes, as the proverb goes, can only be made by cracking eggs. For Renan, making a nation required a violent relation to one’s past. Continuities must be broken, failures erased, and false connections inserted so as to serve the nation, this dreamed-up creation. Citizens were emboldened by accounts that claimed “so-called” victims of their nation’s actions never existed or deserved what they got. For Renan, that also meant that shifting the boundaries of memory could be political dynamite. Prior members of the nation might suddenly seem like outsiders. Forgotten actions might bring to light injustice or illegitimate acts. In a flash, brothers might seem like foreigners, allies like enemies, and supposed enemies not so at all.

Tottering nations were often characterized by unresolved, competing narratives that sowed division and failed to resolve questions of identity. The “Turkish system,” Renan argued, which maintained an “absolute distinction” between religious groups, meant they would forever struggle to unite as one nation. What then might a nation do if it suffered from such instability? The Frenchman didn’t develop this point, but a few years later, a Parisian journalist in Le Figaro pointed to one outcome. Flanked by the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, Romania had recently liberated itself from Ottoman rule. On the edge of Europe, this newborn nation was home to Hungarians, Germans, Jews, Russians, and more. As it sought unity, it witnessed intense anti-Jewish attacks and seemed to stoke a broader anger toward surrounding nations. In 1895, this fervor had ramped up into a “xenophobia,” that “exaggeration” of patriotism that turned a virtue into a vice. The Romanians seemed to hate everybody, it was said, so as to more clearly and ardently know themselves.

TABLE 2: XENOPHOBIA, CIRCA 1890

XENOPHOBIA AS A PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESS |

a pathological fear of strangers |

XENOPHOBIC NATIONALISM |

an irrational political animus toward foreign nations |

The first usages of xenophobia never caught on. As a medical diagnosis, xenophobia was a flop, perhaps due to the proliferation of phobias that brought many others into disrepute; years later, the same irrational fear of strangers would resurface as “social phobia.” In journalistic and political circles xenophobia receded, for it always carried the whiff of exaggeration. After all, who actually feared and hated all other nations? And if drumming up hatred against a targeted enemy was a dangerous form of patriotism, what use was this general hatred, in which the enemy remained unnamed? When Rodolfo Lanciani used this term in 1909 to decry attacks on the Frenchman Gauckler, he was already being a bit precious. His choice was worthy of the italics he provided, and in line with the professor’s preference for innuendo and archaism. For by then, his concept of a nationalistic xenophobia was fast receding as another meaning took center stage.