THERE IS AN excellent saying often attributed to Gandhi, although in fact it comes from Central Africa: ‘Whatever you do for me but without me, you do to me,’ words that succinctly sum up the tragedy of today’s electoral-representative democracy. Even with the best of intentions, those who govern the people without involving them, govern them in only a limited sense. In the eighteenth century, much of the population was illiterate and large areas of any country inaccessible, practical facts which had to be taken into consideration when the decision was made to hold elections. But is that still the case today?

In August 1988 the American periodical The Atlantic Monthly published a remarkable article by one James Fishkin. It was only two pages long, but the content surprised many. It appeared just a few months before the presidential elections that brought George Bush Sr to power after an election battle against Michael Dukakis. Both candidates were nominated by their parties after a long series of primaries and caucuses up and down the nation. Since in the United States the earliest primaries are always held in the states of Iowa and New Hampshire and are the subject of intense media coverage, those states receive far more attention than they actually deserve. After all, whoever does well there will be given plenty of airtime and whoever does badly there might as well give up, since the financiers will pull out. Even before party supporters can take a close look at the candidates, the argument has largely been decided by the private laws of the media and sponsorship.

Is that right? Fishkin wondered. How democratic is it? As a young professor at the University of Texas, he was well versed in recent literature in his field. He was familiar, for example, with Beyond Adversary Democracy by political scientist Jane Mansbridge, which had been published a few years earlier. Mansbridge argues that there are two democratic traditions in America, adversary and unitary, one hostile and one respectful, one of parties doing battle and one of consultation between citizens. Of course Fishkin was also familiar with Strong Democracy by Benjamin Barber, published in 1984 and one of the most influential books on political theory in the final decades of the twentieth century. Barber distinguishes between strong and weak democracies and claims that today’s conflict-ridden representative democracy is typical of the weak variety.

These were interesting times. John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas, two of the most important political philosophers of the post-war era, appealed for greater citizen participation in the conversation about what the future of our society should look like. Such a conversation could be rational and it would make for a fairer democracy at a time when more and more researchers were warning of the current system’s limitations.

Shouldn’t those new ideas be put into practice somewhere? In his article in The Atlantic, Fishkin proposed bringing together 1,500 citizens from all over America for two weeks, along with all the presidential candidates for the Republicans and the Democrats. The citizens would be able to listen to the candidates’ plans and consult each other. Their deliberations would be shown on television, so that other citizens could also make well-founded choices. Fishkin deliberately adopted two aspects of Athenian democracy: participants would be chosen by lot and they would receive an allowance, to guarantee maximum diversity. ‘Political equality stems from random sampling. In theory, every citizen has an equal chance of being chosen to participate.’ The fair distribution of political opportunities: the Athenian ideal rises from the ashes, but what Fishkin had in mind with his sample was more than just another opinion poll: ‘These polls model what the public is thinking when it is not thinking … A deliberative poll models what the public would think if it had a better chance to think about issues.’

The term ‘deliberative democracy’ was born, a democracy in which citizens don’t merely vote for politicians but talk to each other and to experts. Deliberative democracy is a form of democracy in which collective deliberation is central and in which participants formulate concrete, rational solutions to social challenges based on information and reasoning. To prevent a few assertive participants from hijacking the group process, smaller subgroups are normally used, with professional moderators and the outline of a scenario. The literature on deliberative democracy has proliferated over recent years, but its inspiration is 2,500 years old. Fishkin wrote: ‘This solution to the problem of combining political equality and deliberation actually dates back to ancient Athens, where deliberative microcosms of several hundred chosen by lot made many key decisions. With the demise of Athenian democracy, it fell into desuetude, then oblivion.’93

Fishkin made his proposal in all seriousness. He went in search of forms of organisation and of resources but had not reached a final analysis by the time of the 1992 election. How was everyone to be flown in? Where could they stay? Two weeks was a very long time and 1,500 citizens a great many. He adjusted his proposal, deciding that bringing six hundred people together for a weekend was more achievable and statistically still representative. After a few smaller deliberative projects he organised in Britain, he was ready by the time Bill Clinton and Bob Dole came to do battle in 1996. From 18 to 21 January, in Austin, Texas, the first deliberative opinion poll took place, called the National Issues Convention. Fishkin received support from, among others, American Airlines, Southwestern Bell, the city of Austin and PBS, America’s Public Broadcasting Service, which between them donated four million dollars. PBS devoted more than four hours of broadcasting time to reporting on the initiative, so that the broader public could follow the deliberations between the citizens chosen and the presidential candidates. But despite this generous support, Fishkin faced a good many hostile reactions and several opinion-makers decried the proposal. Even before the event began, journalists all over America received copies of the magazine Public Perspective which warned against the initiative.94 Citizens deliberating was considered to be impossible or at least undesirable, and in any case dangerous.

James Fishkin did not allow himself to lose heart. As an academic he wanted to find out what effect consultation like this would have on people. He had them fill in questionnaires – before, during and after the discussions – to see how their insights developed. Beforehand the participants were given files containing factual information, and they had a chance to speak to each other and to experts. Would that change their views? Observers were at any rate impressed: ‘The sense of common purpose, the demonstration of mutual respect and the good sense of humour shared by most participants created a group atmosphere tolerant of conflicting views.’95

The conclusions of the objective soundings were radical and the difference between ‘before’ and ‘after’ turned out to be extremely striking. The consultation process had made the citizens significantly more competent and more sophisticated in their political judgements as they had learned to adjust their opinions and had become more aware of the complexity of political decision-making. It was the first time that scientific proof had been provided to show that ordinary individuals could become competent citizens, if they were given the right instruments. Fishkin believed his experiment offered opportunities for strengthening the democratic process by getting away from ‘poll-driven mass democracy, from sound bites and democracy by slogans’ to an ‘authentic public voice’.96

The work of James Fishkin brought about a real deliberative turn in political science, and the fact that deliberative democracy can give a powerful boost to the ailing body of electoral-representative democracy is no longer doubted by any serious scholar. Citizen participation is not just a matter of being allowed to demonstrate, to strike, to sign petitions or to take part in other accepted forms of mobilisation in a public space. It needs to be institutionally embedded. Fishkin has meanwhile organised dozens of deliberative opinion polls all over the world, often with impressive results.97 Texas, the state where he has worked, drew lots on several occasions as a way of selecting people to come and talk about clean energy, not the most obvious subject for an oil state. As a result of deliberations between those citizens, the percentage of people who said they would be willing to pay more for wind-generated and solar power rose from 52 to 84%. Because of that increased support, by 2007 Texas had become the state with the most windmills in the United States, whereas ten years earlier it was way behind in that field. In Japan the discussion was about pensions, in Bulgaria about discrimination against the Roma, in Brazil about careers in public service, in China about urban policy, and so on, and each time the deliberations led to new legislation. Deliberative democracy also turned out to work in societies that were deeply divided, like that of Northern Ireland. Fishkin had Catholic and Protestant parents discuss reforms to education and it became obvious that people who were in the habit of speaking more about each other than with each other were in fact able to work out perfectly practical proposals.

Elsewhere too new models of citizen participation were sought after. Since the 1970s Germany has made use of Planungszellen, literally ‘planning booths’ and in 1986 Denmark introduced the Teknologi-rådet (Technology Council), a body that works in parallel with parliament to allow citizen involvement in issues related to the consequences of new technology, such as the use of genetically modified organisms. France has since 1995 had a Commission Nationale du débat Public, which enables citizen participation in matters of the environment and infrastructure. Britain is set to work with Citizen Juries, and in 2000, Flanders established the Instituut Samenleving en Technology (Institute of Society and Technology) to involve citizens in technology policy. These are merely a few examples but the website participedia.net has information about hundreds of consultative projects set up over recent years, and the list is growing by the day.

Cities in particular proved fruitful ground for experiment and in New York residents spent two days deliberating what was to be built at Ground Zero, while in Manchester the subject under discussion was crime prevention. In the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre and countless other cities in South America, participative discussions take place in which citizens can become directly involved, deciding on the budgetary policy in their city. In Wenling, China, citizens chosen by lot are able to advise senior party officials about the priorities within large infrastructure projects. In South Rotterdam and Genk in 2013 a large sample of residents discussed the major socio-economic challenges of the future.

Participatory democracy is not limited to national or local democracy, however. The European Union adopted deliberative democracy on a large scale (Meeting of the Minds in 2005; European Citizens’ Consultations in 2007 and 2009) and declared 2013 the Year of Citizens.

Irrespective of whether it’s a matter of citizens’ juries, mini-publics, consensus conferences, deliberative opinion polls, Planungszellen, débats publics, citizens’ assemblies, people’s parliaments or town hall meetings, the organisers have consistently found it worthwhile to hear the voices of citizens in between elections. Electoral-representative democracy has been enriched by a form of aleatoric-representative democracy.

Every deliberative project needs to decide what its citizens’ panel will look like. If citizens can sign up on their own initiative, you can be certain they are motivated and will get involved. The disadvantage of self-selection, however, is that the panel will mainly feature articulate, highly educated white men aged over thirty, the so-called ‘professional citizens’, which is hardly ideal. If people are recruited by lot, there will be more diversity, more legitimacy, but also greater costs, as putting together a good, representative sample is expensive and the non-voluntary participants will have less prior knowledge and can more easily fall prey to a lack of interest. Self-selection increases efficiency, drawing lots increases legitimacy. Sometimes an in-between form is adopted, with the drawing of lots followed by self-selection, or self-selection followed by the drawing of lots.

How not to do it was made clear in April 2008 when the Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd called together a thousand residents for a citizens’ summit about Australia in 2020. He was in search of the ‘best and brightest’ in the country, a slogan that could have come from the late eighteenth century. Citizens had to nominate themselves, present a list of their own qualifications and submit a written account of how they would participate in the process. No compensation was available for travel expenses and overnight stays – and this in a country as vast as Australia. How many poor Aboriginal women from the north would have been eager to book a ticket to Canberra? It was a way of replacing the elected aristocracy not with a democracy but with a self-elected aristocracy, which would mean going from bad to worse. Citizen participation then becomes ‘a meritocratic conclave’.98

Of all the consultation processes of recent years there are five that I believe stand out as the most audacious and momentous. Moreover, they happened at a national level. Two took place in Canada, the others in the Netherlands, Iceland and Ireland. They all came about over the past decade or so (in Ireland the process lasted until late 2013), they all had a temporary mandate and considerable government financing and they all concerned an extremely important subject: reform of electoral law or even the constitution. Here we were truly at the heart of democracy. This was something rather different from allowing citizens to join in discussions about windmills or corncobs.

Figure 4 brings together the basic data for each of those projects. I distinguish between two phases. The first ran from 2004 to 2009 and included citizens’ forums in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Ontario and in the Netherlands, three projects that concerned reform to existing electoral law, or at least the development of a proposal for reform.

The second phase started in 2010 and is still under way. It includes the Constitutional Assembly in Iceland (Stjórnlagaþing á Íslandi) and the Convention on the Constitution in Ireland (An Coinbhinsiún ar an mBunreacht), two projects that considered proposals for changes to the constitution. In Ireland eight articles of the constitution were examined, in Iceland the entire text. It is no small matter to invite citizens to rewrite the constitution and it’s surely no coincidence that two countries that took a real battering from the credit crisis of 2008 have dared to take democratic innovation so far. The bankruptcy of Iceland and the recession in Ireland severely tested the legitimacy of the prevailing model. Their governments had to do something to win back trust.

In 2004 British Columbia made the first move with the most ambitious deliberative process of modern times anywhere in the world. The Canadian province decided to entrust reform of its electoral law to a random sample of 160 citizens. Canada was still using a British electoral system that works according to the majority principle, whereby a candidate with a slight lead in a given constituency wins outright (winner takes all, in contrast to the proportional system). Was this fair? Participants in the citizens’ assembly saw each other regularly for almost a year. Adjusting the rules of the electoral game is the kind of thing that political parties find hard to achieve by themselves, as rather than serving the common interest they continually have to ask themselves to what degree a new proposal will hurt them.

The idea of working with independent citizens seemed sensible in Ontario as well. The province had three times as many residents as British Columbia, but here too invitations were sent to a large, randomly chosen group of citizens who were on the electoral roll. Those interested were asked to attend an informative meeting where they could decide whether or not to take part. Out of that group of candidates a representative panel of 103 citizens was chosen by drawing lots: there were to be fifty-two women and fifty-one men, at least one of them would be a Native Canadian and the age pyramid would be respected. Only the chair was appointed. Of the participants ultimately chosen by lot, seventy-seven turned out to have been born in Canada and twenty-seven were from elsewhere. They included childminders, bookkeepers, labourers, teachers, civil servants, entrepreneurs, computer programmers, students and care workers.

Although the Netherlands uses a form of proportional representation, the political party D66 has been appealing for years for improvements to the rules. When that party was engaged in negotiations to form a government in 2003 it persuaded its coalition partners to set up a Citizens’ Forum to look at the electoral system, based on the Canadian precedent. Enthusiasm in the other parties was rather lukewarm, but if that was what it took to persuade D66 to enter the coalition, they could live with it. When D66 left the government as a result of early elections in 2006, the project was allowed to quietly fade away, so quietly in fact that most Dutch people, even regular newspaper readers, never even heard of it or can barely remember anything about it. That was a shame, since in Canada it produced some interesting work.99

In all these three cases, recruitment took place in three steps: 1) A large random sample of citizens was chosen from the electoral roll by the drawing of lots, and they received invitations by post. 2) A process of self-selection followed, so anyone interested could come to a meeting and put their name forward for the next stage. 3) From those candidates the final group was chosen, again by drawing lots, with attempts being made to achieve a balanced distribution of age, sex and so forth. It was therefore a system of sortition, followed by self-selection, followed by sortition.

In all three places, consultation lasted between nine and twelve months, during which time the participants had their first chance to talk to experts, look at documentation and become familiar with the subject matter. After that they consulted with other citizens and each other, then finally they formulated a concrete proposal for a new electoral law. (We should note, incidentally, that citizens in Ontario chose a different electoral model from those in British Columbia: deliberation is not manipulation in a predetermined direction.)

What is striking to anyone who reads the online reports of those Canadian and Dutch citizen-parliaments is the degree of nuance in arguments for a technically refined alternative. Anyone who doubts whether ordinary citizens chosen at random are capable of making sensible and rational decisions really ought to read those reports. Fishkin’s findings were confirmed once again.

However, what also becomes obvious is that none of the three projects exerted a real influence on policy. Sensible input but hardly any concrete output? Right. In all three cases the proposal from the citizens’ assembly had to be endorsed in a referendum. It seems drawing lots was still too unfamiliar a democratic instrument to enjoy intrinsic legitimacy, rather as if the verdict of an American jury needed to be ratified by referendum. But that’s simply how it was, and as a consequence, the work of dozens of citizens carried out over many months was to be judged by the population in a few seconds. In British Columbia 57.7% of citizens voted in favour, a large proportion but not quite enough to reach the required threshold of 60%. (In a fresh referendum in 2009 enthusiasm shrank to 39.9%.) In Ontario only 36.9% of citizens voted in favour while in the Netherlands Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende’s cabinet decided not to adopt the advice of the Citizens’ Forum, which it had financed to the tune of more than five million euros.

Democratic renewal is a slow process so the reasons for the ultimate failure of that process in Canada and the Netherlands should prove extremely instructive. The causes are several and worth noting: 1) Citizens who voted in the referendum had not been following the deliberations so their raw opinion in the voting booth was in stark contrast to the informed opinion of participants.100 2) Citizens’ forums are merely temporary institutions with a limited mandate, so their voice carried less weight than that of formal, established bodies. 3) Political parties often had an interest in discrediting a proposal or simply ignoring it, since reform to the electoral system would have cost them power (in the Netherlands the government decided not even to hold a referendum but simply to ditch the proposals).101 4) Commercial media in Canada were often extremely hostile to the citizens’ assemblies, irrespective of the content of the proposals, while in Ontario the press was actually hysterically negative.102 5) The citizens’ forums often had no seasoned spokespeople or adequate campaign budgets available; the verdict was pronounced in the media, but the money available was spent on the actual work rather than marketing. 6) Referendums about complex proposals for reform will perhaps always work to the advantage of the No camp – if you don’t know, say No! In the case of the European Constitution it was sufficient for opponents to sow doubt so the Yes camp had to work harder and put more effort into communicating. The question we should ask is whether referendums are a suitable way of taking decisions on complex matters.103

Over recent decades the referendum has often been presented as an effective means of reforming democracy. In a time of individualisation and with organised civil society weighing less heavily than it once did, many thought it would be useful to ask the opinion of the population directly, although this enthusiasm has cooled somewhat since the referendums on the European Constitution in the Netherlands, France and Ireland. They still enjoy great popularity, as was shown by the holding of referendums on independence in Catalonia and Scotland, and on Britain’s membership of the European Union. Referendums and deliberative democracy are similar in the sense that they turn directly to the ordinary citizen to ask his or her opinion, but other than that they are completely at odds with each other. In a referendum you ask everyone to vote on a subject that usually only a few know anything about, whereas in a deliberative project you ask a representative sample of people to consider a subject about which they are given all possible information. A referendum very often reveals people’s gut reactions; deliberations reveal enlightened public opinion.

Citizens’ assemblies may do great work, but sooner or later they have to declare their findings, which is always a difficult process, because the seclusion of civil consultation is suddenly exposed to the glaring light of the public arena. As it turns out, the fiercest opponents consistently come from the camps of the political parties and the commercial media, a phenomenon as widespread as it is intriguing. Where does that hostility come from? A question many academics and activists are asking themselves. Whereas civil society often has a positive attitude to citizen participation – if only because trades unions, employers’ organisations, youth movements, women’s organisations and other players in social life have been engaged in it for more than a century – the press and politicians often tend to be scornful. Is it because they are used to serving as the gatekeepers of public opinion and do not want to give up that privilege? That is almost certainly part of the story. Because press and politicians act within the old electoral-representative system they may find it difficult to cope with newer forms of democracy. Another possibility that cannot be excluded is that those who are accustomed to working top-down find it hard to cope with what comes from the bottom up.

But there are other factors at play. Political parties are always anxious about their voters and although we are familiar with the fact that many citizens distrust their politicians, the idea that politicians can be just as distrustful of their citizens is still new to us. Recall the research by Peter Kanne, which showed that nine out of ten politicians are suspicious of the population. If politicians collectively believe that the population by definition thinks differently from the way they do, then we should not be surprised if they are primed to be sceptical about citizen participation.

The media have their doubts as well. Deliberative processes with citizens chosen by lot are often intense experiences for the participants but they do not fit easily into the format of contemporary reporting. They are slow, there are no leading figures, no familiar faces and no major conflicts. Citizens simply sit at round tables talking, Post-its and marker pens to hand, with little to attract an audience. Parliamentary democracy is theatre and sometimes produces great TV, but deliberative democracy has little drama and is difficult to shape into a story. In Britain, Channel 4 once broadcast a series called The People’s Parliament, which employed James Fishkin as an advisor and used hundreds of citizens, chosen by lot, to debate controversial subjects such as youth crime and laws on striking. The series was abandoned after a few episodes as it simply did not grab the viewer’s interest.104 This too helps to explain the reservations in the media.

Iceland took account of the unfortunate outcomes of the Canadian and Dutch experiments, and to forestall the danger that the work of a citizens’ panel might be ditched before it had a proper chance, far-reaching adjustments were made. For a start, instead of choosing some hundred to 160 citizens by lot, only twenty-five took part, and they were selected by voting. Candidates had to produce thirty signatures. A total of 522 people came forward. The rest of the population went to the ballot box to choose the team of twenty-five. (As a result of squabbling between the official political parties, the vote was later declared null and void, at which point the parliament selected the group itself, but that is beside the point. The philosophy was that the constitutional forum must be elected.) Secondly, there was a desire to avoid the activities of this one small group lacking legitimacy among citizens and politicians. Thousands of citizens were therefore asked to discuss the principles and values of the new constitution beforehand, while seven politicians put together preliminary advice in a 700-page document. This was intended to take the wind out of the sails of later critics. The organisers also deliberately chose not to shut the team of twenty-five up in a black box from which it would emerge after months of internal consultation with a ready-made constitution. Instead, while compiling its new document, the assembly posted provisional versions of constitutional clauses on the website every week. The feedback that came in via Facebook, Twitter and other media led to newer versions that were also placed online and so on, the process enriched by almost four thousand comments. Transparency and consultation were key, the International Herald Tribune describing it as the first constitution to be produced by crowdsourcing.

All this had its effect. When the proposed constitution was put to the citizens of Iceland in a referendum on 20 October 2012, two-thirds voted in favour. To an additional question that had arisen during deliberations by the constitutional assembly, namely whether the natural resources of the island that were not in private hands should become the property of the nation, no fewer than 83% answered in the affirmative.105

Even though after several years parliamentary approval has yet to be given, the Iceland adventure is without doubt the most impressive example of deliberative democracy thus far. Was it the great openness of the whole process that made it so successful or was it the decision to elect the participants rather than drawing lots? It is difficult to say. The election certainly brought competent people to the fore, and this was good for efficiency as within four months a new constitution had been written. However, it was less good for legitimacy. How diverse is a constitutional assembly of twenty-five people if seven of them are in positions of leadership (at universities, museums or trades unions) and of the rest five are professors or lecturers, four are media figures, four artists, two lawyers and one a clergyman? Even the father of singer Björk, a prominent trade unionist, managed to get a place on it. There was just one farmer.106 The composition of the panel was perhaps the weakest link, methodologically speaking, in the entire Icelandic consultative process. The impressive transparency of the process may have contributed more to the mass approval of the proposed constitution than the composition of the citizens’ panel. So the question remains: would a team of citizens chosen purely by lot, with more time and the same degree of openness, be able to put together a constitution that scored just as highly in a referendum?

That question was put on the table a short time later in Ireland. The Convention on the Constitution that began work in January 2013 also drew lessons from earlier democratic experiments. Its conclusions were to involve politicians far more intensively (as in Iceland), but to continue selecting citizens by drawing lots (unlike in Iceland). The Irish also decided that the chances of success and implementation would be greater if they invited politicians to become involved in the process at an early stage. In this they went much further than the people of Iceland. Rather than a handful of them being available to give preliminary advice, they made a conscious decision to bring politicians and citizens together throughout. Sixty-six citizens and thirty-three politicians, from both the Republic and Northern Ireland, including for example Gerry Adams, spent a year in consultation. It might seem strange that a process of citizen participation would ask famous names from political parties to speak, with all their rhetorical talent and knowledge of the issues, but that decision was designed to hasten implementation of the decisions made, reduce the fear of citizen participation among politicians and prevent scornful reactions from political parties at a later stage. The deliberative process can sometimes have a remarkable effect on those taking part, politicians losing their distrust of citizens, just as citizens lose their distrust of politicians. Citizen participation can reinforce mutual trust, although of course there is always the danger that politicians will hold sway. We will have to await analysis of the Irish model, but if the process is properly designed, the disproportionate weight of some participants will be obviated by internal checks and balances, by breaking up into subgroups, for example, and spreading decision-making widely.

The Irish also opted resolutely for the drawing of lots, and their Constitutional Convention built on We the Citizens, a successful project at University College Dublin with citizens chosen by sortition. An independent research bureau put together the random group of sixty-six, taking account of age, sex and origin (Republic or Northern Ireland). The diversity this produced was helpful when it came to discussing such sensitive subjects as gay marriage, the rights of women or the ban on blasphemy in the current constitution. However, they did not do all this alone, as in Ireland, too, participants listened to experts and received input from other citizens (more than a thousand contributions came in on the subject of gay marriage). The decisions made by the convention did not have the force of law, incidentally. The recommendations first had to be passed by the two chambers of the Irish Parliament, then by the government and then in a referendum. There were many locks to pass through, therefore, since in the second phase of citizens’ forums, as in the first, there is a fear that drawing lots may create turbulent waters.

However, on 22 May 2015 the people of Ireland voted in a national referendum in favour of a change to the constitution that would allow gay marriage. The Yes camp received no less than 62% of the votes. The referendum was held after the Constitutional Convention recommended changing the constitution in this respect by a majority of 79%. I can think of no better example of how deliberative democracy can make a difference to practical reality. It was the first time anywhere in the world in modern times that a discussion among citizens chosen by lot led to an adjustment in a country’s constitution.107

So in supposedly Catholic Ireland, the introduction of gay marriage took place in comparative tranquillity, partly because of citizen participation, whereas supposedly libertarian France saw a year of intense political unrest surrounding exactly the same subject. More than 300,000 people joined demonstrations, marching through the streets of Paris. There the citizen was given no say.

I have described in some detail these examples from Canada, the Netherlands, Iceland and Ireland because they represent particularly exciting experiments in democratic innovation. But even though they took place on a large scale and were about essential issues, the mainstream media outside those countries rarely reported on them and as a result much knowledge and experience did not reach a broader international audience. The delay, however, has not stopped others from thinking further ahead. Democracy advances at different rates and while politicians remain hesitant, the media distrustful and citizens uninformed, academics and activists are already way ahead of them. It is their task, as Belgian philosopher Philippe Van Parijs has put it, ‘to be right too soon’.108 When John Stuart Mill argued in the mid nineteenth century that women deserved to be given the vote, his contemporaries said he was mad.

Knowing they could expect condescension or even howls of derision, various authors over past decades have advocated anchoring sortition in democracy institutionally and constitutionally. They were of the view that it should not remain confined to one-off projects but that citizens chosen by lot should become components of the state apparatus. How that could be made possible was a matter for discussion, but a popular proposal was the idea of using the drawing of lots to compile one of the legislative organs. To date more than twenty such scenarios have been put forward.109 Every one of these authors concluded that a randomly composed parliament could make democracy more legitimate and efficient, more legitimate because it would revive the ideal of the equitable distribution of political opportunities and more efficient because the new representatives of the people would not lose themselves in party-political tugs of war, electoral games, media battles or legislative haggling. They would be able to concentrate simply on the common interest. I will look at five of the most important proposals (see Figure 5).110

In 1985 American authors Ernest Callenbach and Michael Phillips suggested transforming the US House of Representatives into a Representative House, the 435 representatives of the people no longer being elected but instead chosen by lot. If such an idea seems to be far-fetched, think again. It would be a mistake to suppose that these authors are fantasists. Ernest Callenbach made his name the year before with his book Ecotopia, which sold a million copies, and many of his audacious insights of those days are now generally accepted. Michael Phillips was a banker who had published books including The Seven Laws of Money and Honest Business. In the 1960s he was the brain behind MasterCard.

The current, purely electoral system was in their view not representative, and too susceptible to corruption, and the power of big money weighed too heavily. Selection by lot could help. Random citizens would be taken from existing lists used for jury service (in the United States these are more inclusive than electoral rolls) to serve as Members of Parliament for three years. Their pay would be in keeping, since there was a need to ensure that poor people wanted to participate, rich people would be willing to interrupt their jobs and those with busy careers could make time. To guarantee continuity, the House would not gather in its entirety on a single day but in instalments, one-third each year. Its powers would be no different from those of the current House: to propose legislation to the Senate and to evaluate legislation proposed by the Senate.

It is striking that Callenbach and Phillips did not advocate doing away with elections altogether. They felt it was useful to have a Senate with elected citizens and a House with citizens chosen purely by lot. Representation had to come about both by electoral and by aleatoric means. ‘We believe that the idea of direct representation is not quixotic. Once it is widely understood, it will have the same overwhelming appeal to fairness and justice that motivated extensions of the suffrage.’111

Their suggestion has been refined over recent years by various authors, and there were proposals for the United Kingdom as well. Anthony Barnett and Peter Carty believed that the House of Lords, the only senate in the Western world in which membership is still hereditary in some cases, must be democratised. Barnett is the founder of the website openDemocracy and he writes regularly for the Guardian while Carty writes for various quality British newspapers (Guardian, Independent, Independent on Sunday, Financial Times and so on). Unlike their American colleagues they want to see the upper house chosen by lot, and not the House of Commons. Nor do they believe that this allotted body should have the right to initiate laws; supervision of legislation coming from the lower house must be sufficient. The new House of Lords, which they rename the House of Peers, would then check that the legislation is clear, effective and constitutional.112 Of course they realised that this was a radical plan, but a democracy does need prospects. They write that the life of every important idea goes through three phases: ‘First it is ignored. Next it is ridiculed. Then it becomes accepted wisdom.’113

Keith Sutherland, a researcher attached to the University of Exeter who identifies himself as a conservative, believes it should be the other way round. The House of Lords should remain the House of Lords with the House of Commons transformed into an allotted chamber, as in the American proposal. He also believes that generous pay is important and follows his British colleagues in proposing not to give the right of initiative to the allotted house. He does wonder whether minimal conditions should be attached regarding age, education and competence. As a conservative he suggests that those eligible should be over forty as the needs of younger members of the population already receive enough attention, he believes, in the mass media, party politics and marketing. Whatever might be thought of that, the bottom line is clear: ‘Sortition is an indispensible component of any system of government that seeks to call itself democratic.’114

In France political scientist Yves Sintomer proposed not replacing the Assemblée or the Sénat with an allotted chamber but instead enriching the system with a new chamber. Members of this ‘Third House’ would be chosen by lot from among volunteer candidates and he too points to the importance of suitable payment and information provision. Staff would be available to support representatives, as is now the case with elected députés. He does not say who should have what rights, but he proposes that the Third Chamber should concern itself with subjects that require long-term planning (ecology, social issues, electoral law and the constitution). This, after all, is the dimension that all too often goes by the board in the current model.115

German professor Hubertus Buchstein also advocates setting up an additional chamber, not at a national but at a supranational level. There is a need for a second European Parliament, he says, this time made up of citizens chosen by lot. He calls it the House of Lots. Its two hundred participants would be selected by sortition from the total adult population of the European Union, spread equitably over the member states, for a term of two and a half years. Participation would be compulsory, short of some unavoidable obstacle, and he too believes that the financial and organisational conditions must be such that no one has any good reason to decline. Unlike the British authors he thinks that the EU’s House of Lots should be able to initiate legislation, as well as having the right to advise and even to veto. These are far-reaching measures, but Buchstein is of the opinion that ‘a deliberative pressure to decide’ is necessary to counter Europe’s democratic deficit.116 Only with deliberative pressure of this kind can the Union hope to achieve efficient and transparent decision-making.

What we notice if we put these various proposals side by side is that first of all they concern very large entities: France, the United Kingdom, the US or the EU. The time has passed when sortition seemed suitable only for city states and mini-states. Second, despite considerable differences of opinion, there is a consensus regarding the term of office (ideally several years) and the remuneration (ideally generous). Third, the unequally distributed competencies of citizens must be obviated by training and by the support of experts, as already happens in parliaments today. Fourth, the body selected by lot must never be seen as separate from an elected body but complementary to it. Fifth, all these proposals advocate using sortition for just one legislative chamber.

In the spring of 2013, the academic periodical Journal of Public Deliberation published a fascinating contribution by American researcher Terrill Bouricius. In a previous life Bouricius had worked for twenty years as an elected politician in the state of Vermont and he asked himself how achievable earlier proposals were. Could the replacement of an elected chamber with an allotted chamber give democracy a new boost by injecting more support and more energy? His question was particularly pertinent. Ideally there would indeed be a European Parliament, based on sortition, that was representative of the entire EU, but how many women running baker’s shops in Lithuanian villages would close their shutters for several years to take their seats in Strasbourg in the House of Lots? How many young engineers in Malta would abandon their promising building projects for three years because Europe had drawn lots and happened to select them? How many unemployed people in the British Midlands would leave pub and friends for years to tinker around with legislation alongside people they’d never met? And even if they wanted to do it, would they be any good? Such a parliament might be more legitimate, because more representative, but would it also be more efficient or would most of those chosen by lot come up with all kinds of excuses for not going, so that the representation of the people again became a task for highly educated men? Strengthening democracy by drawing lots to form an assembly sounds good, but it comes up against countless objections. You want everyone to have a say, but that is to risk new forms of elitism. How can the ideal be reconciled with the practicalities? That was the question with which Bouricius struggled.

He returned to Athenian democracy, studied its workings and asked himself what its modern application would look like. In Athenian democracy sortition was typically used not merely for a single institution but for a whole series, thereby creating a system of checks and balances, one such body keeping an eye on the other. ‘The Council of 500 set the agenda, and prepared preliminary decrees and resolutions for the Assembly to consider, but could not pass laws. The passage of a decree by the People’s Assembly could be over-ruled by a People’s Court, but these Courts could not pass laws themselves.’ The decision-making process was therefore spread across several institutions (see Figure 2B). This might seem to be a bit of a rigmarole, but it had clear advantages:

The Athenian separation of powers between multiple randomly selected bodies and the self-selected attendees of the People’s Assembly achieved three important goals that our modern elected legislatures do not: 1) the legislative bodies were relatively descriptively representative of the citizenry; 2) they were highly resistant to corruption and undue concentration of political power; and 3) the opportunity to participate – and make decisions – was spread broadly throughout the relevant population.117

Working with several allotted bodies (‘multi-body sortition’ as Bouricius calls it) ensured more legitimacy and more efficiency.

How could such a system work today? In Figure 6 I have tried to present Bouricius’ model in diagram form. I have done so based on his article, supplemented by an earlier study and by email correspondence with him and his colleague David Schecter.

In reality, says Bouricius, you require as many as six different organs because there is a need to reconcile conflicting interests, and being an expert in the field of democratic innovation, he knows what a challenge this is. You want sortition to provide a large, representative sample, but you also know that it’s easier to work in small groups. You want rapid rotation to promote participation, but you also know that longer mandates produce better work. You want to let everyone take part who wishes to do so, but you also know that this means highly educated and articulate citizens will be over-represented. You want citizens to be able to consult each other, but you also know that this presents the danger of group thinking, the tendency to be too quick to find a consensus. You want to give as much power as possible to an allotted body, but you also know that some individuals will put too much pressure on the group process, producing arbitrary outcomes.

These five dilemmas are familiar to anyone who has ever worked with alternative forms of consultation. They concern the ideal size of the group, the ideal duration, the ideal selection method, the ideal consultation method and the ideal group dynamic. Well, according to Bouricius there is no ideal, so better just give up the quest for one and set about designing a model that consists of several organs. That way the advantages of various options can reinforce each other and the disadvantages weaken each other.

Instead of giving all the power to a single allotted body, legislative work is best split into a number of phases.

In the first phase the agenda needs to be set. In Bouricius’ system this happens in the Agenda Council, a very broad organ whose members are chosen by lot from those who have put themselves forward (rather in the way the Athenian people’s courts worked). The Agenda Council designates topics but does not develop them further, as it doesn’t have that power. Citizens who don’t belong to this body but want to draw attention to a specific subject can use their right to petition, and if they can collect enough signatures their issue will be dealt with.

In a second phase, all kinds of Interest Panels are brought into play. There may be just a few of them, or there may be a hundred. Interest Panels are groups of twelve citizens that can each propose a bill, or part of a bill. Members are neither elected nor chosen by lot, they simply volunteer to help think about that particular subject. Such a panel may have twelve members who don’t know each other and have no common purpose, but they might equally well be a lobby. This is not a problem as they do not have the last word and must take into account the fact that their proposal will be evaluated by others. Working with Interest Panels ensures that those who have relevant experience can combine their expertise for use in drawing up concrete policy proposals which will help make the system efficient. Imagine traffic safety is on the agenda. Those involved might be neighbourhood organisations, cyclists’ federations, bus conductors, people from the transport sector, parents of children killed in car accidents, motorists’ organisations and so on.

In a third phase, all these proposals are put before a Review Panel, of which there is one for each policy area. Proposals concerning traffic safety, for example, come before the Review Panel that concerns itself with mobility. These panels are best compared with parliamentary committees as they do not have the right to initiate legislation nor to vote on its adoption, merely doing the work in between (as did the Council of 500 in Athens). Using the input received from the Interest Panels, they organise hearings, invite experts and work on developing legislation. All the Review Panels combined, Bouricius proposes, will have 150 members, chosen by lot from among citizens who have put themselves forward, and their job will carry great responsibility. Members take their seats for three years, they work full time and are paid appropriately, receiving an amount comparable to that of a parliamentary salary. They are not all replaced at once, but in phases, fifty seats per working year.

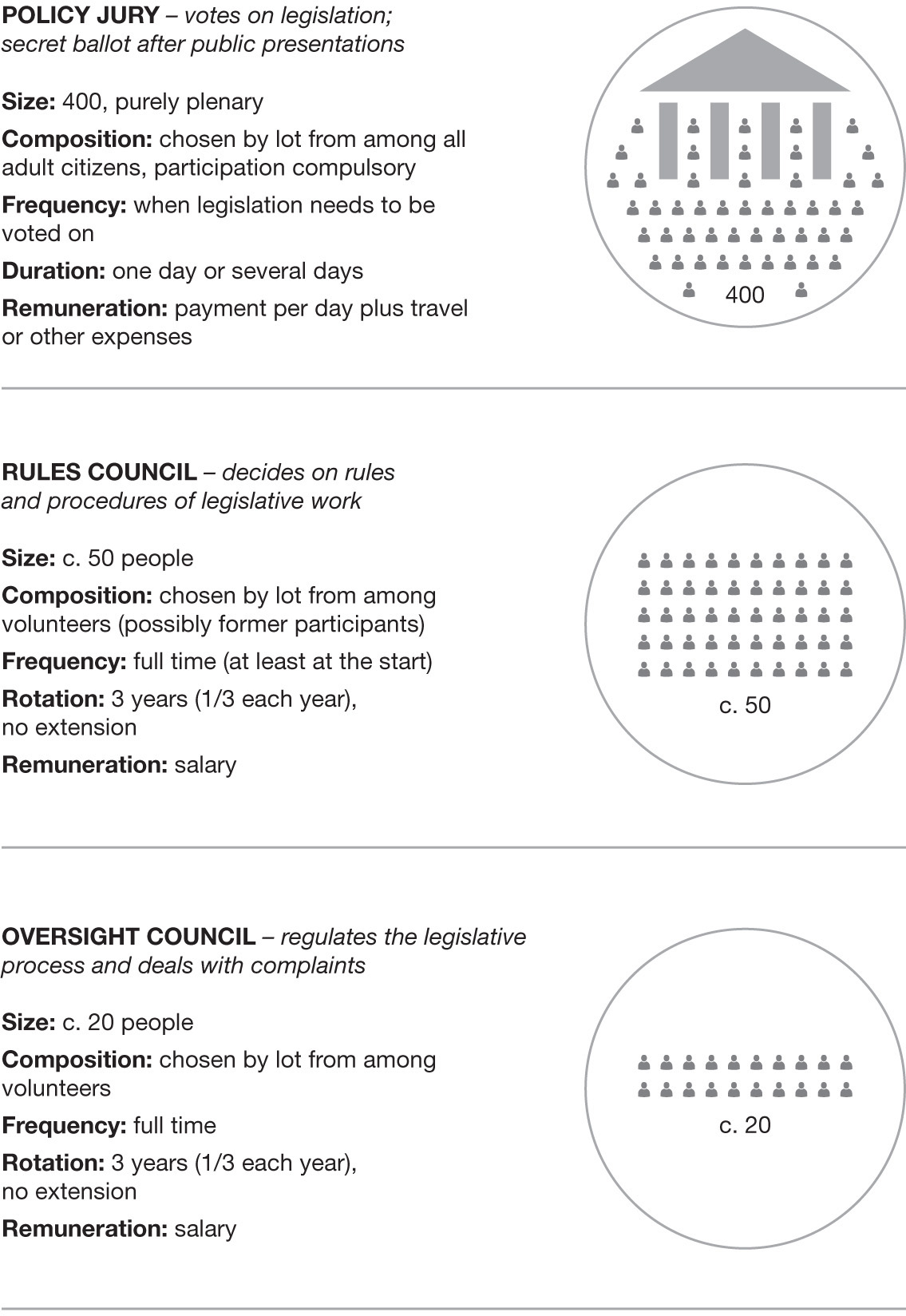

To avoid all power being concentrated in the Review Panels there is a fourth organ, a very important one. Legislation is put before a Policy Jury, the most unusual organ in Bouricius’ plan. It has no permanent members. Every time a vote on a piece of legislation is needed, four hundred citizens are chosen by lot to come together for one day or in certain cases for several days, a week at the most. Crucially, lots are drawn from the entire adult population and not just those who have put themselves forward as candidates, so in this sense it is more like jury service for a criminal trial. To ensure the body is as representative as possible, whoever is chosen has to appear unless he or she has a valid excuse, so for this reason participants are well rewarded for their attendance. The Policy Jury hears the various legislative proposals put together by the Review Panel, listens to a formal presentation of arguments for and against, and then votes on them in a secret ballot. So there is no further discussion, no party discipline, no group pressure, no tactical voting, no political haggling and no back-scratching. Everyone votes according to their conscience, according to what he or she feels best serves the general interest in the long term. To avoid charismatic speakers influencing the mood, the legislative proposals are presented by neutral staff members. Because the verdict is that of a good cross section of society as a whole, the decisions of the Policy Jury have the force of law.

To streamline the process, Terrill Bouricius proposes a further two organs, a Rules Council and an Oversight Council, both again chosen by lot. The first is responsible for developing procedures for the drawing of lots, for hearings and for voting. The second ensures that civil servants follow the correct procedures and deal with any complaints. These two councils therefore have a meta-political function, compiling and safeguarding the rules of the game. The Rules Council could be chosen by lot from among people who have already served in one of the other allotted bodies and who therefore know the ins and outs of the procedures.

What makes this model particularly attractive is its capacity to evolve, as nothing is fixed beforehand. ‘A key factor is that all of this would only be a starting design,’ Bouricius wrote in an email,

but it would evolve as the Rules Council deemed optimal. The one rule I would like to somehow make permanent is that the Rules Council cannot grant themselves more power. Perhaps an initial rule should be that rules changes that affect the Rules Council itself can only go into effect after there has been a 100% turn-over in membership. Also, once the system is in place for a while, I can imagine limiting the lottery pool for the Rules Council to volunteers who have served on some other randomly selected body previously.118

Instead of tracing everything out in minute detail beforehand therefore, he is developing a ‘self-learning system’. One striking thing about this blueprint is how the eternal quest for democracy – for a favourable balance between efficiency and legitimacy – is given shape here in a system based purely on drawing lots. The fact that citizens can voluntarily put their names forward for five of the six organs would definitely help to inject vigour into the system (for the Interest Panels they do not even need to be selected, as anyone who wishes to can take part). But the fact that the ultimate verdict, the last word in the decision-making process, rests with the representative sample of the Policy Jury is essential for legitimacy. In a nutshell: anyone who feels capable of serving society is given the chance to get involved in the discussion, but it is the community as a whole that ultimately decides.

This balance between maintaining support and acting decisively would not have seemed possible in the late eighteenth century. The American and French revolutionaries thought state business too important to be left to the people and by opting for an elected aristocracy they gave priority to efficiency over legitimacy. Nowadays we are paying the price for that. Discontent is rife and the legitimacy of the electoral-representative system is being noisily called into question.

Bouricius’ proposal is exceptionally exciting. It is a stimulating example of how democracy could be set up in a completely different way. It takes its inspiration from ancient Athens but does not simply adopt those procedures wholesale without further thought. It is founded upon recent academic research into deliberative democracy and experiments with the drawing of lots, so it recognises the potential traps of specific formulas. It develops a system of checks and balances to avoid those traps and to prevent any concentration of power, and above all it brings politics back to the citizens. The elitist distinction between governors and governed is abolished completely, returning us to the Aristotelian ideal of having people alternate between ruling and being ruled.

So where do we go from here? Brilliant historical research has been carried out, political philosophers have done wonderful work, we have a mass of inspiring practical examples and several refined proposals are on the table, of which Bouricius’ is particularly promising. What is the next step?

Bouricius’ model is designed to evolve, but it can start to do so only once it becomes a reality, and how the transition from the current system to his system could be effected remains unclear. In an earlier piece, written with his colleague David Schecter, he suggested that the model could be applied ‘in a variety of ways’:

What if we were to see those five possible applications as five steps in a historic transformation? Start hesitantly and end enthusiastically, a process that has in a sense already started. Phase 1 happened in Canada, phase 2 in Ireland and phase 3 has been going on longest. Phases 4 and 5 – yes, those are of course the great challenges and we haven’t got anywhere with them as yet. It’s definitely too soon for the full application of Bouricius’ programme (phase 5). Unless they face the threat of revolution, political parties will not be quick to dissolve themselves overnight in order to make multi-body sortition possible, but the time for phase 4 is approaching.

Democracy is like clay, it’s shaped by its time and the concrete forms it takes are always moulded by historical circumstances. As a type of government to which consultation is central, it is extremely sensitive to the means of communication available. The democracy of ancient Athens was formed in part by the culture of the spoken word, and the electoral-representative democracy of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries thrived in the era of the printed word (the newspaper and other one-direction media such as radio, television and internet 1.0). Today, however, we are in an era of articulacy, of hyper-fast, decentralised communication, which has created new forms of political involvement. What kind of democracy is appropriate to it?120

How should the government deal with all those articulate citizens who stand shouting from the sidelines? First, with pleasure rather than suspicion, because behind all the anger both online and offline lies something positive, namely engagement. It may be a gift wrapped in barbed wire, but indifference would be far worse. Second, by learning to let go, not wanting to do everything on the citizen’s behalf, because the citizen is not a child. At the start of the third millennium, relationships are more horizontal.

Doctors have had to learn to deal with patients who’ve already looked up their symptoms on the internet. At first that seemed problematic, now it turns out to be a blessing because empowerment can assist recovery, and the same applies to politics when authority changes. Once you had authority and were allowed to speak, now you gain authority by speaking. Leadership is no longer a matter of taking decisions on behalf of the people but of setting processes in train along with the people. Treat responsible citizens as ballot fodder and they’ll behave like ballot fodder, but treat them as adults and they’ll behave like adults. The bond between government and the governed is no longer the same as that between parents and children. We are all adults now and politicians would do well to look past the barbed wire, trust the citizens, take their emotions seriously and value their experience. Invite them in, give them power and because it will always be fair, take all their names and draw lots.

I believe the systemic crisis of democracy can be remedied by giving sortition a fresh chance. The drawing of lots is not a miracle cure, not a perfect recipe, any more than elections ever were, but it can correct a number of the faults in the current system. Drawing lots is not irrational, it is arational, a consciously neutral procedure whereby political opportunities can be distributed fairly and discord avoided. The risk of corruption reduces, election fever abates and attention to the common good increases. Citizens chosen by lot may not have the expertise of professional politicians, but they add something vital to the process: freedom. After all, they don’t need to be elected or re-elected.

For this reason it is worthwhile in this phase of history to entrust legislative power not only to elected citizens but to citizens chosen by lot as well. If we can rely on the principle of sortition in the criminal justice system, why not rely on it in the legislative system? It will restore a good deal of peace. Elected citizens (our politicians) will not be driven by commercial and social media alone, they will be flanked by a second assembly to which election fever and viewing figures are totally irrelevant, an assembly where the common interest and the long term still come first, an assembly of citizens in which it is truly possible to have a conversation, not because those citizens are thought to be better than the rest but because circumstances will bring the best in them to the fore.

Democracy is not government by the best in our society, because such a thing is called an aristocracy, elected or not. That is one option, but then let’s change here and now what we call it. Democracy, by contrast, flourishes precisely by allowing a diversity of voices to be heard. It’s all about having an equal say, an equal right to determine what political action is taken. As American philosopher Alex Guerrero put it recently: ‘Each person in a political jurisdiction should have an equal right to participate substantively in determining what political actions will be taken by that political institution.’121 In short, it’s about governing and being governed, about government of the people, for the people and, at last, also by the people.

Yet the water is still deep. ‘Citizens can’t do this!’ ‘Politics is difficult!’ ‘Idiots in power!’ ‘Plebs at the helm, beware!’ And so on. Before going any further we need to take a look at the most common argument against sortition, the supposed incompetence of the non-elected. This criticism has a positive aspect as it proves that many people cherish the quality of their democracy. Woe betide the country where democratic innovation raises no objections, for it is a place where concern has been swallowed by the waves and apathy reigns. Woe betide the country that cannot have a tranquil conversation about the future of democracy, for there hysteria prevails.

The general panic engendered by the idea of sortition shows the degree to which two centuries of the electoral-representative system and hierarchical thinking has succeeded in firmly fixing in people’s minds a belief that affairs of state can be looked after only by exceptional individuals. I’ll address a few of my opponents’ arguments:

Anyone who looks something up on Google Maps these days will find there’s a choice between a map and a satellite image, one better for planning the route, the other for looking at the surroundings. Democracy is just like that. The representation of the people is a map of society, a simplified representation of a complex reality, and because that representation is used to make a rough sketch of the future (and what is politics about if not making a rough sketch of the future?), this map needs to be as detailed as possible, so that topographical map and aerial photograph complement each other. We urgently need to move towards a bi-representative model, a system of representation that is brought about both through voting and by drawing lots. After all, both have their good points, the expertise of professional politicians and the freedom of citizens who do not need re-election. The electoral and aleatoric models therefore go hand in hand.

The bi-representative system is at this point the best remedy for the Democratic Fatigue Syndrome from which so many countries are suffering. Mutual distrust between rulers and ruled will be reduced if their roles are no longer so clearly separated. Citizens who gain access to the governmental level through the drawing of lots will discover the complexity of political dealings, a marvellous training in democracy. Politicians in turn will discover an aspect of the civilian population that they generally underestimate, a capacity for rational, constructive decision-making. They will discover that some laws are accepted more quickly if ordinary people are involved from the beginning, more support making decisive action possible. In short, the bi-representative model is relational therapy for rulers and ruled.

Perhaps this dual system will eventually have to give way to a fully allotted system (Bouricius’ phase 5); after all, democracy is an ongoing process. But at this point the combination of sortition and election is the most effective cure available as it takes what is best about the populist tradition (the desire for more authentic representation) without the dangerous illusion of a monolithic people. It incorporates the best of technocratic tradition (valuing the technical expertise of non-elected professionals) without giving experts the final word, and it also makes use of the best of the tradition of direct democracy (the horizontal culture of participatory consultation) without its anti-parliamentarianism. Finally, it reassesses the best aspects of classic representative democracy (the importance of delegation in making government possible) without the electoral fetishism that always goes along with it. Through this combination of beneficial elements, legitimacy grows and efficiency increases as the more the governed identify with the government, the more those in power can govern decisively. The bi-representative model will steer democracy into calmer waters.

When should the transition start? Now. Where? In Europe. Why? The European Union has an advantage. What? It offers shelter to member states that have the courage to innovate in ways that affect their democratic foundations.

Governmental renovation is always a perilous undertaking. At a local level, cities and municipal councils started to work with citizen participation on a large scale only after being encouraged to do so by their national governments. In its turn, the European Union could think of measures that would stimulate and encourage member states to set up useful pilot projects. After all, the Union was the first to try out random sampling and deliberative democracy on a large scale.122 It was also the Union that chose to name 2013 the Year of the Citizen. What are the high democratic ideals of the Union worth if democracy is crumbling in so many of its member states?

The crisis in the southern member states (Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus) has brought the spectre of a post-democracy closer, while in Hungary and Greece crypto-fascist movements have been more than merely crypto for some time. In Italy and Greece, technocrats have taken over from democratic governments for short periods. In the Netherlands, France and the United Kingdom populism has become a major factor, and in the recent past, Belgium spent a year and a half without a government. And so on.

It would be interesting to try out the bi-representative model for the first time in a country like Belgium. No other member of the European Union has experienced so acutely the symptoms of Democratic Fatigue Syndrome. After the election of 2010, 541 days passed before a governmental team emerged, an absolute world record. Moreover, no other country today offers such a great opportunity to successfully implement sortition. From 2014 onwards, Belgium will no longer have a directly elected Senate. At the federal level, legislative power will henceforth lie exclusively with the parliament, the Chamber of Representatives. Over past decades much national power has been transferred to lower governmental strata: Flanders, Wallonia, Brussels and the German-speaking region.123 To keep the different levels formally in contact with each other, the Senate is now evolving into a chamber of reflection, a meeting place for the various regional powers in the country. The Senate was once a space for the Belgian aristocracy, like the British House of Lords, but now it is more a chamber for regional diversity, like the American Senate. Fifty of the sixty senators have their origins in regional parliaments, the other ten are co-opted. The proportion of elected senators has been reduced systematically. In 1830 the entire Senate was directly elected but today none of its members are elected, which fact opens up opportunities for sortition. Successive changes to the constitution have made the population familiar with the idea that direct elections are no longer an absolute precondition for putting together the national assemblies. If there is one place in the European Union where aleatoric-representative democracy has a chance of being introduced, then it is in the recently reformed Belgian Senate.124

In a bi-representative Belgium, the Senate could consist purely of citizens chosen by lot, while the lower house could continue to accommodate elected citizens. How many senators there should be, how lots should be drawn, what powers such a Senate should have, how long its mandate should last and what remuneration would be reasonable are not questions to answer now. It is more important to think about the gradual introduction of multi-body sortition. With the support of the EU, the national government could first apply sortition to the making of a single law (for example to determine what powers would be retained by the federal state). This would require only a few Interest Panels, a Review Panel, a Citizen Jury, and politicians could decide beforehand what was to be done with the result. Would the advice be binding or non-binding and when would it be given the force of law?

If experiences were to be positive, the use of sortition could be expanded to a specific policy domain, preferably one that is too delicate to be resolved by party politics (Bouricius’ phase 2). In Ireland the Convention on the Constitution looked at gay marriage, women’s rights, blasphemy and electoral law. In Belgium it might be a matter of the environment, asylum and migration, and issues concerning the different linguistic communities. To achieve this it would be necessary to organise an Agenda Council, a Rules Council and an Oversight Council, making citizen consultation a permanent part of the governmental archipelago, the complex of islands that communicate with each other in a new democracy to give shape to the whole.125 In a subsequent phase, politicians would decide whether or not to make citizen participation through sortition permanent and follow up with the necessary arrangements – the Senate could be converted into a legislative organ consisting of a number of different bodies (Bouricius’ phase 4).

Belgium could become the first country in Europe to introduce the bi-representative system in practice. Just as Iceland and Ireland have boldly seized upon the financial-economic crisis of recent years as an opportunity to crowdsource their constitutions, Belgium could seize upon its political crisis of recent years to rejuvenate its democracy. There are other countries too where a pilot phase would seem appropriate, for example Portugal, because of the crisis but also because of its familiarity with participative budgets in what is, all things considered, still a young democracy; Estonia, an even younger democracy that faces a huge problem in the form of the need to decide on the part to be played by the Russian minority; Croatia, the youngest member of the European Union, where active citizenship and good governance are now being actively promoted; the Netherlands, with its experience of an Electoral System Citizens Forum and its long tradition of consultation, and so on. It seems to me in any case sensible to start with relatively small member states.

This proposal is not as futuristic as it may appear at first sight. Citizens chosen by lot already have power and, in a few years from now, opinion polls that use random sampling will have evolved all over Europe from neutral barometers of the political climate into extremely important instruments for allowing political parties to adjust their messages. They do not merely measure the popularity of this or that party, politician or measure. They are becoming political facts in their own right and wield a huge amount of influence, as governments attribute great value to them and decision-makers take account of them. The aim of those who propose sortition is to do no more than to make transparent a process that already exists.

In short, what are we waiting for?