CHAPTER 1

Glamour and the Depression

FIG 1.1: Northgate, Chester: A visit to the cinema was an opportunity to escape from the grind of everyday life and with the advent of ‘Talkies’ the number of cinemas in the country boomed with around 5,000 by the end of the 1930s. Unlike many other buildings, modernity and foreign style was acceptable, especially with Odeon Cinemas, as in this example from Chester. These startling plain, geometric compositions contrast dramatically with the historic styles that dominated Victorian and Edwardian architecture, as used in the shops on the left of the picture.

The two decades between the World Wars project distinct and conflicting images. There are the glamorous Hollywood films, flamboyant dance crazes, and distinctive popular fiction like Agatha Christie’s Poirot. They create an image of luxury, style, glamour and wealth in this vibrant and fast Jazz Age. In contrast, however, the history we are taught in school tells of the Depression, the General Strike and the Jarrow March. Photographs of rundown industrial towns, dole queues and slum dwellings give an impression of decline and economic constraints. How can these two extremes exist alongside each other? What were those inter-war years really like for the middle and working classes who would live in and own the types of house which we will be covering in this book?

FIG 1.2: The Cenotaph, Whitehall, London: War memorials, from Sir Edwin Lutyens’ Cenotaph in Whitehall (above) to the humble stone cross in every village or hamlet, focused the grief of the nation and would remind future generations how the distant catastrophe had touched even the smallest community. The style often used, as with many other public buildings, had moved on from the ornate baroque and gothic structures of the previous generation to a more simple, starkly geometric form of classical architecture.

The Great War 1914-1918

Life in the period 1918 to 1939 was affected both politically and economically by the First World War, known before the second conflict as the Great War, which began on 4 August 1914.

There was no shortage of volunteers in the early months of the conflict, although as the war sank into an economically sapping stalemate and the casualty list lengthened, the quality of those signing up dropped markedly and a large proportion had to be rejected on health grounds. The honest working class Tommy was simply not fit enough!

Unlike the Second World War, this conflict passed by with little direct effect at home, although the Zeppelin bombing raids were a foretaste of the wars to come. Its most notable legacy on the domestic front was how those who were unable to fight, especially women, filled in for the absent men on duty in France. Towards the end of the war, there were restrictions and rationing but these were nothing compared to the suffering endured by the Germans at home, as the blockade by the British Navy virtually starved the German homeland into submission.

After the Armistice on 11 November 1918, there could be no return to the situation before the conflict. Things had changed, the world was not quite the same place and Britain was no longer at the economic centre of it.

Industry and the Economy in the 1920s and 1930s

Along with the other European nations, we had borrowed heavily through the war and sold foreign assets. America had bankrolled us and now with its industrial and financial might it enjoyed a boom during the 1920s. New factories were mass-producing goods and skyscrapers soared into the sky in competition with each other, forming iconic images which told the world the USA was the bigger, better, new kid on the block! The Wall Street Crash of October 1929 brought it back down to earth and the ripples from the impact radiated around the globe, sending economies into further depression.

The British economy suffered a roller-coaster ride during the inter-war years, starting with an initial boom on the expectation of a return to normality and then quickly sinking with the realisation that old markets were not there any more. Countries which had previously bought manufactured goods from us had either found other sources during the war and did not return to Britain after it, or simply did not have the money available. This loss of foreign business, coupled with the investment many companies had made on an expectation of a return to pre-war levels of demand, caused a dramatic downturn that resulted in rising unemployment by 1921. Although there was a gradual pick-up through the 1920s, the effects of the Wall Street Crash hindered exports and yet again the economy suffered.

However, this depression resulted in low prices for raw materials and food, which along with dropping interest rates meant that those Britons in work had more money left over at the end of the day. By spending it on their houses, new cars, electrical goods and clothing they helped fuel a consumer boom that softened the worst effects of global depression.

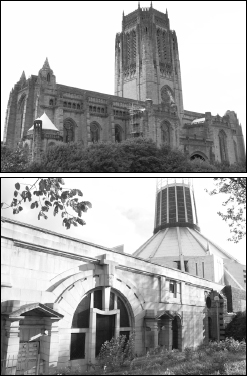

FIG 1.3: Despite the constraints upon the public purse after the First World War, there were still building projects on an imperial scale like the Anglican (top) and Roman Catholic (bottom) cathedrals in Liverpool. The former was completed in this period but work on the latter, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens to be the largest in Christendom, was cut short by the Second World War. The familiar concrete ‘wigwam’ was erected later upon the foundations of the earlier building, the crypt of which can be seen in the foreground of the bottom picture.

FIG 1.4: The Chrysler Building, New York, USA: With the relative freedom for companies to develop in the mid and late 1920s, America became dominant in world finance and business. Nowhere was this more visible than in the craze for erecting the tallest skyscrapers, one of the most iconic being the Chrysler Building, which for a matter of months became the tallest in the world.

Despite this turbulent economy and the National Debt, Britain as a country became more wealthy per head of population. Wages, which had risen dramatically during the First World War, never returned to pre-war levels and in 1939 were nearly twice as high as in 1914. Due to new state subsidies this apparent wealth was spread more evenly across the classes than before, yet even at the outbreak of the Second World War more than four-fifths of the nation’s capital was controlled by one-twentieth of its population!

The economic well-being of the individual was heavily dependent on whether they were in work or not and, in this period, there were stark differences between the regions and old and new industries. Victorian and Edwardian success had been built on the back of cotton mills, iron and steel works, shipbuilding yards and coal mines, which because of the climate, geology and geography of the land tended to be concentrated in the North of England and South Wales. With the decline in exports, improved foreign competition and new technology, these staple industries declined and had to restructure to survive. The ones that really suffered were the workers as the number of jobs in these trades were nearly halved through this period and, despite prominent displays of unity with the General Strike of 1926 and the Jarrow March ten years later, their situation rarely improved. The new curse of long-term unemployment had arrived, with thousands of men with skills that were no longer needed who lived in areas where there was little alternative employment, and resulted in many families falling into poverty.

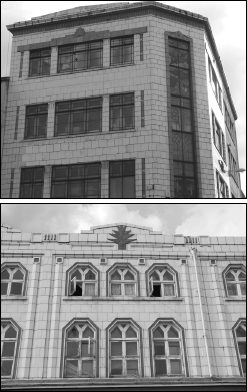

FIG 1.5: New shops in the latest Art Deco style were built along high streets in most towns and cities, especially department stores where a room or entire house could be fitted out by the one shop. These two examples, the lower one showing flats, commonly built above small shops, are finished in glazed white tiles with green highlights, a popular combination of colours. The tall vertical window in the top example has a wonderful stained-glass design.

FIG 1.6: New industries required new factories, no longer towering high with floors of clanking machines stacked above each other but now spread out over spacious suburban sites with symmetrical horizontal frontages and improved conditions for staff.

On the other side of the coin, however, were the new industries based on technology. The motor car, aeroplane, electrical goods, energy supply, chemical, drug and engineering industries boomed in this period, doubling the number of people employed. As the number of manual workers dropped, so the number of white-collar workers rose to replace them, reflecting the shift to more science-based light industry. There were increasing numbers of managers, administrators, consultants, engineers, and accountants with, at a lower level, clerks, assistants and typists, many of whom in the previous generation would have gone into domestic service or the mills. The sales of these new products helped the retail sector, with new department stores and national chains appearing on the high street, which resulted in the recruiting of more sales assistants and shop managers.

The problem, though, was that most of this new work was in the South and Midlands, with around 50% of the new factories built in the first half of the 1930s being sited within Greater London alone.

Although there was some natural redeployment between areas, there was little help from the government and what schemes there were had limited success. It is for these reasons that the majority of private houses covered in this book will be found in the suburbs and along the main arterial roads of midland and southern towns and cities.

Society in the 1920s and 1930s

For those in employment during the inter-war years, life could be a significant improvement over that of previous generations, with more freedom, better health and spare income. Electoral reforms meant that all men over 21 could vote, although some archaic voting practices based on house ownership and university seats remained, as could women for the first time (only the over 30s at first, but the age limit was lowered to 21 by 1928).

The health of the nation took a step forward as improved medicines and health services as well as new, more spacious and cleaner housing helped towards a drop in death rates, especially infant mortality. Some of this was due to government action after it had been realised that the poor condition of recruits in the latter stages of the First World War had seriously affected our military efficiency. Much was also due, though, to the realisation that diet had a more significant effect on health than previously thought and to families spending more on a wider variety of food. At the same time, new methods of contraception and family planning reduced the birth rate as couples began to limit the number of children they would have from an average of three before the war to around two a decade or so later.

With fewer children, there was more money in the average family pocket at the end of the day. This increase in real incomes was also enhanced by a lower cost of living as everyday goods, food and mortgages became cheaper. It was also easier to get credit, with hire purchase schemes enabling many middle class families to have their first car, better furniture and the latest electrical goods. There was more money to spend in the expanding range of high street shops, too. Popular buys included vacuum cleaners, off-the-peg clothing and radios.

FIG 1.7: Many factories, offices and public buildings were built in a style that resembled structures from the Ancient World. These Art Deco forms, which were popular in the inter-war years, owed much to new archaeological discoveries in Egypt and Central America, most notable of which was the unearthing of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

Shorter working hours (falling to around 48 hours a week) and paid holidays for more people meant that a break away at the seaside became a reality. There were booming resorts around the coast, some with the first holiday camps for the masses and others offering more exclusive locations for the middle classes, although shorter weekend breaks were still more common than a whole week off. Days in the countryside were available to all with trains, buses and cars taking millions out of the towns and cities to go rambling, hill walking or cycling.

There was a greater variety of entertainment closer to home. With the introduction of the ‘Talkies’, cinema attendance continued to grow and around 2,000 new cinemas were built in this period. Many were luxurious, with the latest modern styling and fittings influenced by American taste, as was much of the consumer culture. Now more people had Saturday afternoons off, football and other sports benefited with increased crowds and larger stadiums. At home, for the first time, you could be entertained not by a family member banging out familiar tunes on the piano but by professional entertainers, comedians and musicians through the new wonder of radio. With the establishment of the BBC, sales of radio sets boomed with around 9 million by 1939. This also meant news could travel to the masses rapidly so, whereas most people had had to rely on newspapers to discover we had gone to war in August 1914, nearly everyone was listening to, or aware of, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s fateful words 25 years later.

FIG 1.8: Office blocks like this example by Sir Edwin Lutyens in Manchester, with a stone-clad, steel-frame construction, stepped masses and plain sides, owed much to structures from the Ancient World as well as the Classical Orders and were a distinct style of the inter-war years.

The principal beneficiaries of this improved standard of living were the middle classes. With a greater number of technical and administrative jobs in the new and old industries there was an increasing number of people who would regard themselves as part of this social group. Most of the new private houses built in this period were aimed at these new middle class families.

The more potent image of the age, however, records the plight of those working class families who were unable to benefit from this prosperity, principally due to unemployment or large family size. The insecurity of working class life, the loss of income through sickness or retirement and the limited state support available left many families in poverty. They were often squeezed into tiny, decaying Victorian houses which, crammed into narrow streets, were unable or unfit to be modernised and hence descended into slums. There were, however, the first serious large-scale attempts at remedying this persistent problem as the government raised taxes to help finance working class housing schemes.

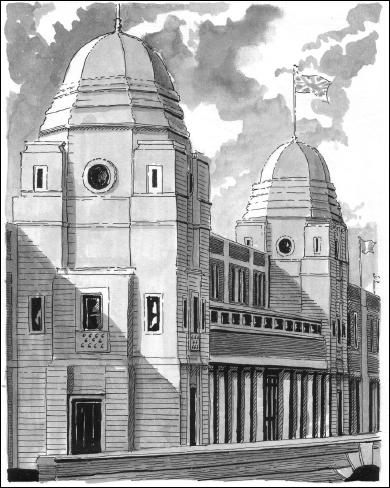

FIG 1.9: Wembley Stadium, North London: This most famous of football stadiums staged its first game in 1923, the ‘White Horse’ Cup Final, which was packed to the rafters, reflecting the growing popularity of the game. The structure was built as the centrepiece of the British Empire Exhibition, with pavilions reflecting the styles of the individual colonies set out around it. The event was a great success with the public but did not have such a long-term influence as the International Exhibition held in Paris the following year. On the site of the stadium had previously stood Watkin’s Folly, a British version of the Eiffel Tower set to be even taller than its French counterpart. It was the brainchild of Sir Edward Watkin, the chairman of the Metropolitan Railway, but after problems with the foundations and a lack of public interest when it reached its first 200ft stage, work came to an end and it was finally demolished in 1907. The railway company had more success with other building projects as their lines spread out of North London, and worked with builders to develop the fields around their stations, creating a ribbon of development still known today as Metroland.

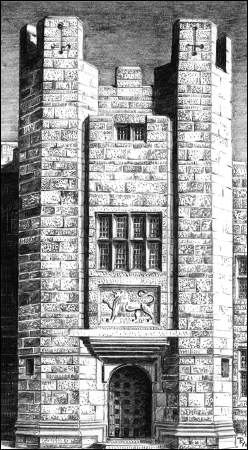

FIG 1.10: Castle Drogo, Devon: Regarded as the last great country house built in England. It was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens in 1910–11 but was not completed until 1930 and then on a much reduced scale. Lutyens was probably our greatest architect of the last hundred years and created very individual designs in traditional and later more modern classical forms (see also FIG 1.2 and FIG 1.8).

Those same taxes hit the upper classes the hardest, especially families with large, landed estates. The aristocracy had always invested in property, relying upon the rents they could charge for those using it, but, with the Agricultural Depression of the late 19th century, land values plummeted and incomes were reduced. At the same time new taxes and death duties further sapped their wealth and even before the First World War country houses were being sold off and demolished.

A further problem after the war was the loss of male heirs. One of the benefits of good living is good health and most people from this class were willing recruits and fit enough for the front line, where they invariably were made into officers. Unfortunately in this position they were also the first over the top when the call came and hence took the full brunt of enemy gunfire.

The loss of the next generation coupled with further increases in taxes to help pay for the war forced many more families to reduce their accommodation, and try to find other uses for their estates or sell up completely. Huge country houses which were expensive to heat and maintain had little appeal other than for private schools so many ended up being demolished in a wave of destruction which lasted into the 1950s and 1960s.

Despite this loss of the nation’s heritage, it was appropriate that for the first time the state was directing the nation’s wealth to building houses for the masses, and it is these suburban private and council estates which will be the subject of the next chapter.