CHAPTER 3

Structure and Materials

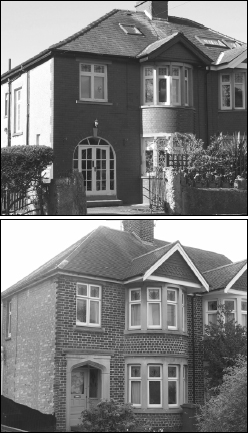

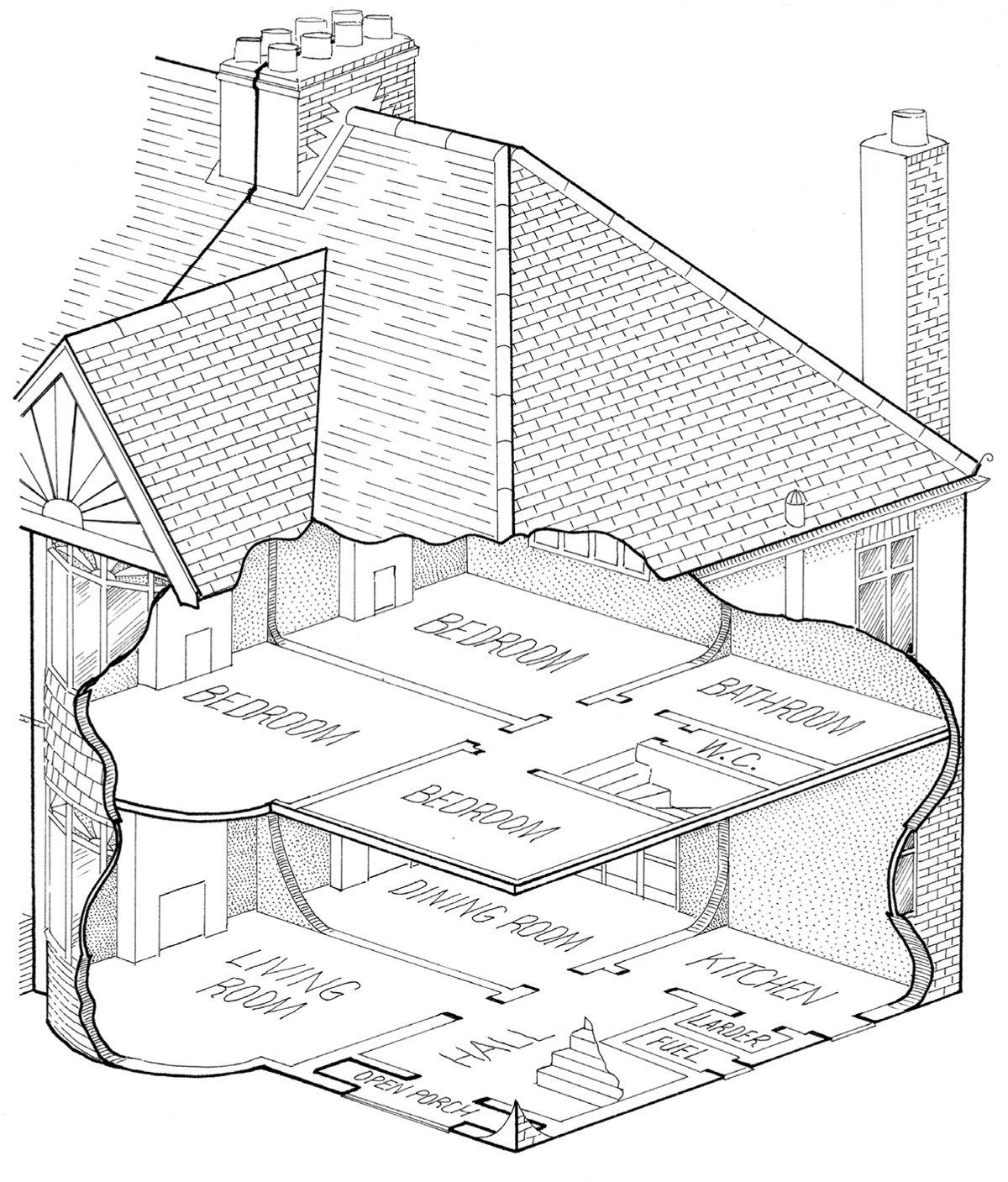

FIG 3.1: A typical detached house from the 1930s, with a brick-built, round bay (bow) window, prominent gable, steep hipped roof and semi-circular porch set into the wall. It is red brick with machine-made tiles on the roof, with some hung from the gable and bay, and wooden casement windows. Its simple plan with a front and rear room, kitchen and three bedrooms above was repeated across the country.

The inter-war housing boom, which peaked in the mid 1930s, saw the construction of more than 4 million homes in Britain so that by 1939 nearly a third of the population lived in post-First World War houses. To achieve the lower costs that made the houses available to a wider customer base and this unprecedented number possible, there were notable changes to the supply of materials and the type of construction.

Standardisation and mass production of materials, the construction process and the design of the house itself had gradually changed the way houses were built over the previous century. The vernacular architecture of the pre-industrial age was made from local materials by local builders, with skills and techniques passed down from generation to generation. As the working population shifted from village to town in the late 18th and 19th centuries a variety of two-room deep, brick or stone terraces with slate roofs could be found in virtually any corner of the country. Further standardisation occurred in the second half of the 19th century as a boom in publishing of architectural papers and magazines made fashionable designs and plans by leading architects available to the local speculative builder.

FIG 3.2: Semi-detached houses, one from Lancaster, the other from Oxford, showing how similar forms of house were found nationwide.

FIG 3.3: Stewartby, Bedfordshire: This village was for workers at the London Brick Company works. This was one of the sites where new extraction machines and conveyor belts increased production as the Fletton bricks produced came to dominate the market.

At the same time mechanisation and foreign imports had reduced the costs of materials and the improving railway network the availability of them. In the wake of the First World War a large number of lorries and vans flooded the market and road haulage firms were established, which as they were not restricted like the railways to published, fixed prices, could easily undercut them, reducing transport costs further. They also delivered direct to site, so cheaper, mass-produced materials were now easier to source for the smaller builder, still the majority in the trade at the time. Technology had even reached the building site itself as new cement mixers and mechanical diggers speeded up the process of construction and reduced the cost of labour. Further savings could be made as many of the parts and details of the house could be ordered ready-made or in kit form out of catalogues from suppliers in this country and across Europe.

FIG 3.4: It was still common at this date for better quality bricks to be used for the front (right) and cheaper bricks down the side (left), hence the difference in this example.

By the inter-war years the appearance and layout of buildings was remarkably similar wherever they were built and although some may mourn the loss of local styles and individuality, the larger and better quality house that could now be afforded by the masses presented an appreciable achievement which had been largely beyond previous generations.

Bricks

The changes in source and appearance of materials were no more clearly seen than in the humble brick. With the repeal of brick tax in the 1850s, the standard-isation of size, and improvements in production, it became the dominant house building material. Although during the 19th century construction elements like timber were often sourced from abroad, the brick was generally supplied locally from small brickworks, which were still a prominent part of the market at the turn of the 20th century. As a result the variations in the clay in that area affected the colour of the final brick so there was still some regionalisation in Victorian housing. Some of the better quality examples were sold nationwide like ‘Nori’ bricks (‘iron’ spelt backwards to demonstrate their strength) from Accrington, and Staffordshire Blue engineering bricks, which were particularly resistant to damp and became popular for damp courses.

One of the main costs affecting the price of bricks is that of firing and in the later 19th century new extraction machines made it economic to reach deeper beds of clays containing particles which when heated aided the combustion, meaning bricks could be fired at lower temperatures and hence cheaper. The mass extraction of these clays, especially the Oxford Clay around Bedford and Peterborough which made cheaper Fletton common bricks, began the decline of the local brickworks.

In the inter-war years the improvements in transport meant large quantities were also coming from abroad, especially the Low Countries. With little variation available, it was the plain red brick and some darker brown varieties that tended to dominate. Most had a flat, smooth surface though there were still speciality bricks produced for the facades of better quality houses and others with pressed patterns in the surface which became popular in the 1930s.

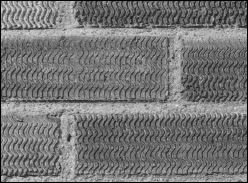

FIG 3.5: Patterns pressed into the face of bricks were popular, especially the waving lines design as in this example.

FIG 3.6: A cut-away view of the side of a house showing the possible construction of floorboards in a front reception room (left) and the kitchen behind it with a solid floor (right). The thick black line through the brickwork marks the approximate position of the damp proof membrane.

The inter-war years mark the transition from traditional methods and materials to modern types. You will find houses built in the same way as those before the First World War, but increasingly more which used new forms similar to those of today. The walls of the house are the most visible evidence of this change.

Foundations of Victorian houses were notoriously shallow with the bricks stepped out at the base for stability and some later ones with concrete footings below. In the inter-war years you are more likely to find deeper trenches a couple of feet down with stronger, reinforced concrete set in the base. A persistent problem with any house is rising damp and in the late Victorian and Edwardian period there had been a variety of methods to combat this. The most common was the insertion of slates between the bricks a few courses above the ground or the use of dark blue/grey engineering bricks, which were virtually impervious to water. It was also common before the First World War to have the ground floor level raised slightly with an air gap below the floorboards ventilated by air-bricks in the outer wall, to further reduce the problem. This continued in the 1920s and into the 1930s though simpler methods with solid floors began to appear, as did the use of engineering bricks for the damp course membrane, or a layer of bitumen felt rather than slate.

FIG 3.7: Air-bricks were positioned in the outside wall to provide a through flow of air under floorboards although solid floors were becoming increasingly common.

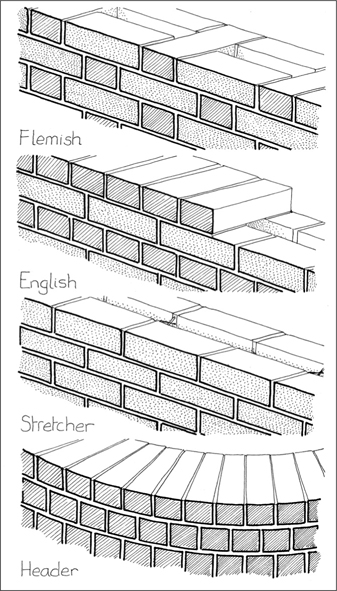

The form of the brick walls above was determined by the pattern used for laying them, known as the bonding. The traditional method was for a solid wall (usually around 9 ins wide, determined by the length of the brick lying across the wall) to be constructed from bricks set either lengthways with the long face showing out (stretcher) or across the wall with the short end facing out (header). The most popular types of bonding were Flemish, with alternate headers and stretchers on each course (a single horizontal line of bricks), and English, with alternate courses of headers and stretchers.

It had long been appreciated, however, that a wall with an inner and outer face of stretchers, which left a gap between them, was better for insulation and damp resistance. This had been used in some regions with either iron ties set in the mortar or the occasional brick set across to hold the two sides together. In the inter-war years this became the dominant method of constructing a wall with twisted steel ties replacing the old types. The mortar between the bricks was even changing from traditional lime and sand mixes to ones using new cements (often called Portland cement as its colour was similar to the grey Portland stone from Dorset).

FIG 3.8: Four common forms of bonding. English and Flemish bond fell from favour as Stretcher bond with a cavity between the faces became the standard form. Header bond was usually found in curved bays to achieve a smooth radius.

The main dividing walls inside the house were still made from brick although these were now cheaper common bricks like Flettons as they would be plastered and not visible. Internal, non-load bearing walls had usually been timber frames with laths (thin horizontal strips of wood) nailed across and covered in plaster. Now these walls could be made from a new wonder material, the breeze-block. It was strong, lightweight, had good insulation properties and was cheap. It was made from coke breeze (small cinders and dust from furnaces, gas works and smelters) mixed with cement and sand. As it was easy to nail fixings to the blocks, they were sometimes used as a layer just above floor height on the inner face of the main wall, so skirting boards were easy to fit.

Floors

Ground floors were either solid or suspended, the former typically used in the kitchen, the latter in the rest of the house. Later houses might have the whole ground floor solid, as are modern houses. Suspended floors were raised above the ground level on joists with air-bricks in the outer walls to ventilate below and reduce problems with damp. Solid floors had this space filled in with hardcore and a concrete layer poured on top with a screed over this (see FIG 3.6).

Roofs

It is surprising in light of the drive to reduce the cost of building houses that the tiled, hipped roof, one with all four sides sloping, was the dominant type in this period. It is harder to construct than a simple pitched roof and the use of tiles increased the pitch and weight so thicker and more numerous rafters were required to support it, making it an expensive option.

FIG 3.9: Four types of roof used in the inter-war years. From top to bottom they are the hipped roof, the pitched roof, the mansard roof (with a double pitch) and the flat concrete roof.

With this standard form, however, the timber used to make the trusses could be supplied in set dimensions, keeping costs down with the wood just cut to length on site. The loft space created within was usually left open with gaps or vents set under the eaves so air could circulate within the void to reduce damp. On larger houses the space might still be used as an attic with dormer windows and occasionally simple flush types inserted to give light.

Machine-made tiles had replaced slate as the most popular form of roof covering. They were made with a nib projecting from the underside so they could be hung over the horizontal battens with the occasional row of nails to hold them tight. The ridge along the top and the hips down the sides were capped with semi-circular tiles, secured in place at the bottom of the sloping hips by vertical hip irons to stop them simply sliding off (a popular alternative for the hips were bonnet tiles: see FIG 3.11 right). S-shaped pantiles and flatter Roman tiles were very popular, especially the former in bright glazed greens and blues, inspired by West Coast American homes featured in Hollywood films. Slate was still common, its lighter weight and larger tile size permitting it to be laid at a shallower pitch (the angle of the roof). Another distinctive type found in this period on cheaper and experimental housing was the diamond-shaped asbestos tile, seen more often on outbuildings and garages in a corrugated sheet.

FIG 3.10: A cut-away view showing the parts of a hipped roof on a semi-detached house.

FIG 3.11: Types of roof covering. From left to right they are machine-made clay tiles, Roman tiles, pantiles, and diamond-shaped asbestos tiles.

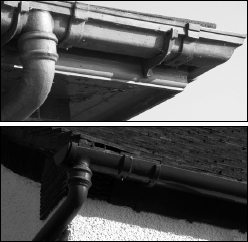

FIG 3.12: Guttering was usually cast iron with either an angular (top) or semi-circular profile (bottom).

Chimneys

Chimney stacks and the pots or caps on top can give a useful clue to where fireplaces originally were within a house. Don’t assume that all rooms originally had one as it was not common in smaller bedrooms in cheaper housing. In Edwardian and some 1920s houses, the stack was built directly above the fireplace, emerging half way down the slope of the roof. In the more common inter-war semi with its hipped roof, it was built up the party wall between each half, shaped like a tuning fork and emerging in the middle of the ridge. As there was often a boiler or range on the rear outer side of this type of house an additional thin single stack was built, but as the top of all chimneys had to terminate above the highest part of the roof (to avoid downdrafts) it resulted in perilously thin chimneys which have often been removed at a later date.

Although the style of chimney would reflect that of the house, most were generally short, stubby and plain with simple terracotta pots on top. More imposing types which had been made popular before the war on Arts and Crafts and Revivalist houses continued to be built on the large Mock Tudor buildings, though, with the rapid spread of electricity in the 1930s, some houses were built without chimneys, relying on new electric heaters and fires.

With the widespread availability of designs through magazines, trade papers and exhibitions, the plan of the inter-war house became very standardized with little if any regional variation. In fact, to a large degree, the rectangular or square plan house with reception and service rooms on the ground floor and bedrooms on the first was similar for most types of speculative-built house with just an increase in the size and number of rooms accordingly. The different styles were applied to these regular structures rather than radically shaping them, as builders with tight margins and in a periodically volatile market used a tried and tested layout they knew their customers would be comfortable with.

Architect-designed detached properties and experimental housing had much more variety, notably with designs focusing on trying to get the most sunlight inside and opportunity to soak it up outside. The obsession with sunshine and fresh air and its link to good health was a constant theme in this period, especially with the more modern-thinking designers.

Houses were also smaller than before the war although the wider plots they were set upon give the opposite impression. The reason for this was partly that families were getting smaller, but also live-in servants were becoming a rarity with the middle classes who before the war would have expected to find room for a general maid and perhaps a cook. The process of cooking and cleaning was being simplified by modern appliances and pre-packaged foods that required little preparation. The upper and middle classes simply didn’t need the specialist service rooms they once had. Ceiling heights were also lower. A room now typically around 7 ft 6 ins high was much cheaper to heat than a Victorian or Edwardian one up to a couple of feet higher.

FIG 3.13: Two houses of similar structure but different styles showing how on the mass housing the decoration was simply applied to standard structures.

Detached houses could vary greatly in layout and size, from the large country residence to the compact suburban unit. Despite the turbulent economy and the pressures upon the owners of many country estates, there was still a strong demand for luxury houses with room not only for the family but guests too. A notable change at the top end of the market was the simplification of the service area. Gone was the complex of rooms and facilities which made the house self-sufficient, now that most food could be bought in and machines did much of the work previously done by staff. At the rear the stable block was being replaced by garages, a feature that by the 1930s was included in most detached houses, either built onto the structure with a bedroom above or as a separate block to the side. At the other end of the scale the small detached house offered little additional room over an average semi, although the increased privacy and status made the extra cost worthwhile to many.

Detached houses permitted the builder more freedom with layout and the style chosen had more of an effect on its plan. Neo-Georgian houses were symmetrical and usually rectangular in plan with the longer side facing the road, while the popular Mock Tudor style was more irregular in layout. Many speculative-built detached houses appeared as no more than an oversized semi with one half chopped off. Y-shaped and angled house plans which had first appeared in the Edwardian period became a popular design, the arms of the house spread open in a welcoming stance.

FIG 3.14: A large detached house in a Neo-Georgian style with a central hall and landing, and the rooms leading off it.

FIG 3.15: Many detached houses were narrow and built on plots barely any larger than that for a semi, but the status and privacy created was worth the extra cost to many.

Semis

Although the iconic inter-war, middle class semi-detached house varied in size it did not so much in structure – a roughly square plan with a two-storey round, bow or splayed bay at the front and on larger examples an extension to the side with a garage below and bedroom above. A notable change in layout which helps distinguish inter-war semis from Edwardian and Victorian types was the position of the front door. Earlier types had them positioned side by side but after the war it was more common and by the 1930s almost universal to have them at the far ends of the front (see FIG 3.17). More modern plans altered the standard layout slightly by putting the entrance at an angle on the corner or half way down the side (see FIG 3.20).

FIG 3.16: A Y-shaped house with its two wings facing the road open in a welcoming stance.

FIG 3.17: A drawing showing one possible arrangement of a medium sized Edwardian semi (top) and a 1930s semi (bottom) showing the position of the front door and its relationship with the rooms behind it. Putting the door at the far side increased privacy, an important consideration for buyers.

FIG 3.18: A cut-away view of a semi-detached house showing a common arrangement of the interior.

With few exceptions the ground floor had a hall leading to a front and rear reception room and a kitchen, while upstairs there were bedrooms positioned around the landing and a separate bathroom and WC. The hall was wider than would have been found in a Victorian house of the same class, which permitted a more elaborate staircase and perhaps a cloakroom, important features in an area designed primarily to impress guests. It was still customary for there to be separate doors leading off the hall or landing to each room and it was rare in the mass market to find other openings between them as had sometimes been fitted between the front and rear reception room in Victorian houses. Now that there was unlikely to be a live-in cook or maid, accommodation did not have to be provided so the roof space which formerly had been bedrooms or a nursery in many pre-war houses was usually void, and if converted this was often done by later owners.

Smaller Semis and Terraces

The smaller private or local authority built semi-detached houses were still set on spacious plots and may not appear much different in size to larger houses. However, they often lose the wide space to the side that could fit a garage or drive and are shorter front to back so more houses could be fitted per acre on an estate. This was also achieved by splitting a semi into maisonettes and with the use of terraces of usually between four and six houses, with at least one tunnel between them accessing the rear.

FIG 3.19: A semi-detached council house dating from the 1930s with a cut-away showing a possible interior layout having a side entrance.

The interior plans dispensed with many of the luxuries featured in middle class semis. The hall was usually just a lobby with stairs leading directly off and there were often only two main rooms downstairs, a living room and a kitchen/scullery behind it. A WC was always fitted, usually on the ground floor off a lobby space or in a small rear extension as regulations demanded a space between it and the cooking area. A bath was also provided but this might be housed in the scullery (either pulled out or hidden under floorboards) so it was near the hot water supply, or in better examples where piped hot water was provided, in a small, separate bathroom often but not always upstairs. The larger semis would have three bedrooms, down to just the one in smaller flats and maisonettes, with a fireplace only in the main bedroom and this would only usually be used when someone was ill.

FIG 3.20: In more modern houses the main door could also be positioned on the front corner (top) or down the side (bottom) creating slightly different ground floor arrangements.

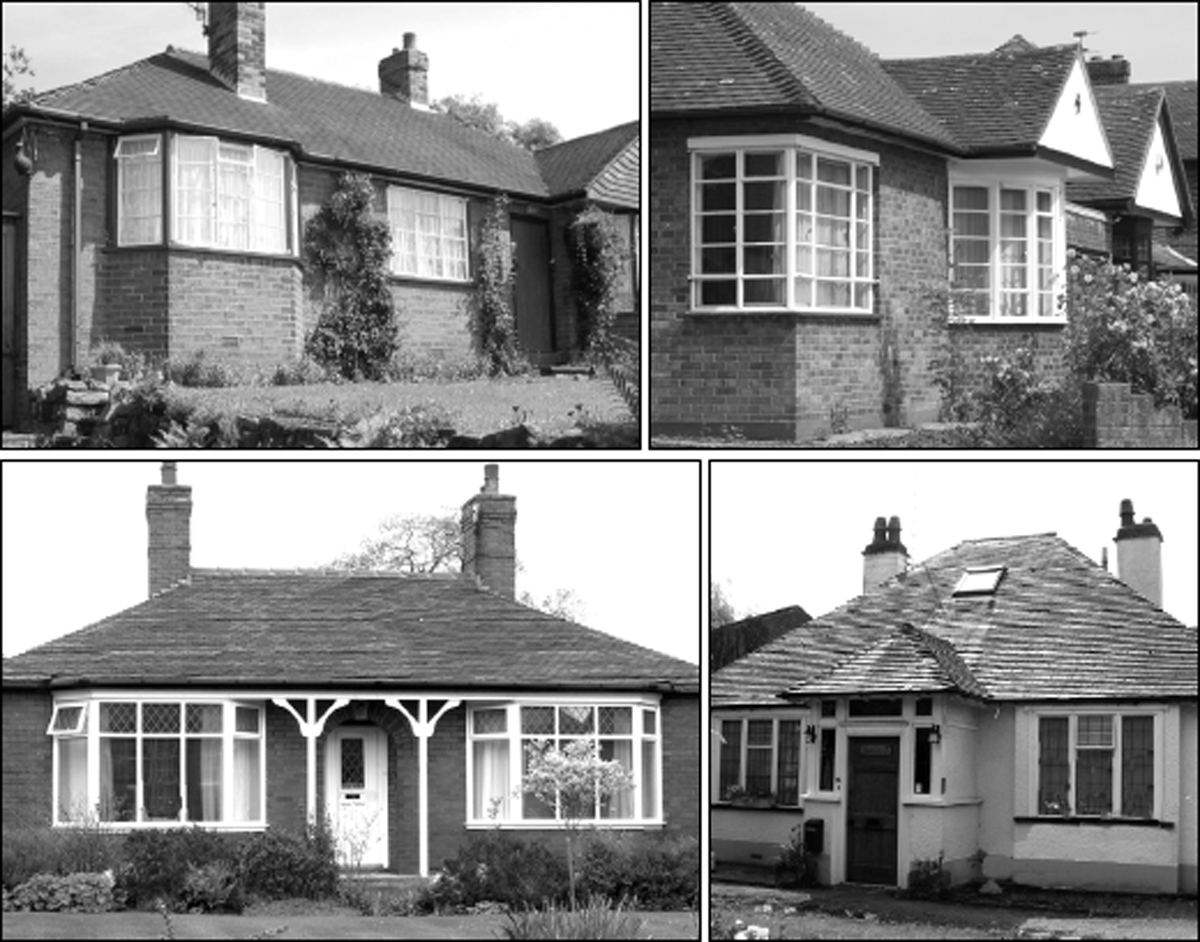

Bungalows

As land was relatively cheap in the new suburbs, the single-storey bungalow came to prominence on estates, especially along the coast where its low profile avoided the worst of the weather. The term is of Hindu origin and described a low building with a veranda used by the British in mid-19th century India. In the late Victorian and Edwardian period the term was used for the simply built or prefabricated chalets that were popular for second homes.

By the inter-war period this type of house was also popular in a permanent form with brick construction, often rendered especially near the seaside as protection against the salt and weather. The roof was usually pitched or hipped with clay tiles, slate or asbestos coverings.

The plans of most were simple with a central front door leading to reception rooms, bedrooms and as with most houses, a small kitchen. In the 1930s more modern designs sited the door down the side, with wider windows at the front to try and capture the most light.

FIG 3.21: Bungalows from the inter-war years.

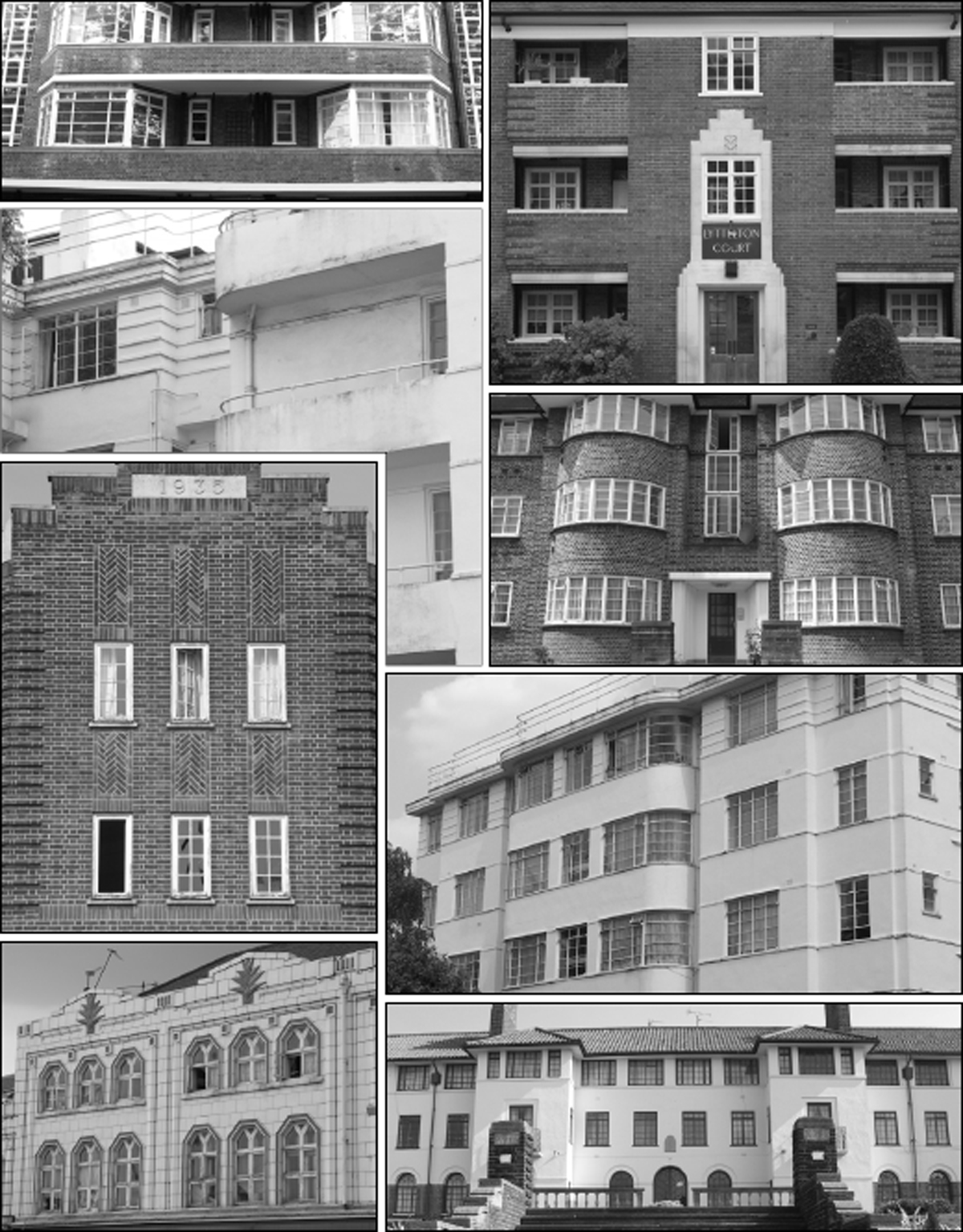

Flats

Flats had never really been popular in England. The first purpose-built structures (as opposed to tall, old houses which had been subdivided at a later date into individual flats) were first erected in the mid to late 19th century in attempts to clear slum areas (famously the Peabody Estate flats in London). By the Edwardian period and more frequently in the inter-war years, local authorities were beginning to use them for the same purpose although these often grim, brick-built structures with dark central courtyards were not a vast step forward despite the improved facilities they provided.

At the same time higher quality, stylish blocks of four to five storeys, often termed ‘Mansions’ or later ‘Courts’, were being erected in cities, especially London. Although they were not radical in design, as they were really just individual houses stacked upon each other, they provided a blank canvas for more ambitious styling than would be seen on the average house. Those built in the 1920s and 1930s have become iconic symbols of the age.

FIG 3.22: Examples of flats from the inter-war years. They could vary from two or three storeys above shops or purpose-built blocks of five or six, but larger, high rise blocks of flats were rare at this date.

Prefabs and Experimental Housing

It had long been understood that the problem of slums and overcrowding in the industrial towns and cities of the world would not be solved until cheaper homes were provided which the poor could afford to rent. In the opening decades of the 20th century competitions were arranged, often in conjunction with new garden suburb developments, to showcase new designs and materials. The Ideal Home Exhibition, which started in 1908, was also an opportunity to give people a glimpse of the future.

FIG 3.23: Black Country Museum, Dudley, West Midlands: A surviving experimental iron house dating from 1925 with a close up of one of the panels used to make the outer skin.

They were trying to reduce costs on two fronts, firstly by the use of cheaper materials and secondly by prefabricating the parts in a factory. This idea of a mass-produced, permanent house also had the advantage of being quick to assemble and did not require so many skilled hands. Early on, structures in timber, concrete, iron and later steel were all experimented with but usually failed to become popular due to problems with their durability, noise and condensation. By the 1930s many of those problems were solved and some of the materials and designs found favour although not until after the Second World War when a shortage of supplies and housing made the use of non-traditional construction widespread.

FIG 3.24: A timber and asbestos constructed chalet with corrugated sheet roof. It has a kitchen, living room and two bedrooms and has survived in almost original condition for 80 years.

Throughout the early 20th century, however, one form of mass-produced house had always been popular, the prefabricated chalet or bungalow, especially in the 1920s when land was cheap but brick-built houses expensive. These basic designs had a quaint appeal and a price tag that made them ideal as a second home along country roads, rivers and the coast. They were usually timber frames clad in materials like asbestos, wire coated in render or wooden planks which were simple to assemble or construct on site. Roofs could be pitched structures covered in corrugated asbestos or more complex hipped types with diamond-shaped tiles or slates.

FIG 3.25: The De la Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex: This startling, simple and graceful modernist building was a revelation when it appeared in this quiet seaside town in 1935. Its welded steel frame took the weight of the structure so the walls could be filled with glass creating light and spacious interiors, as had been requested by the Mayor of Bexhill, Earl de la Warr, after whom it was named. This theme of open planned interiors, sun terraces and large glass windows was to be repeated in a number of notable and revolutionary houses which appeared in some rather startled suburbs in the 1930s.

The one material that was experimented with and used for first public and commercial building and later housing, was reinforced concrete. It enabled the architect to create forms that were impossible in many traditional materials and at a speed and cost which could potentially undercut them. It was in the hands of Modernists that the abilities of the material were put to full effect, where the very structure of the house became the style, and the vertical walls but cosmetic infill. The full impact of these and how they contrasted with the conservative styles of the time are covered in the following chapter.