CHAPTER 6

Reception Rooms and Kitchen

FIG 6.1: A notable change in 1930s houses was the shift of emphasis on the central feature in a room from the fireplace to the window or French doors. Light was one of the controlling factors in the design of Modern interiors, as in the example above. However, displays like this in contemporary photographs and room settings show what could have been created at the time rather than what was, and it is likely that most homes were filled with an eclectic mix of traditional furniture, family heirlooms and the latest gadgets.

FIG 6.2: The interiors of speculative-built houses had changed from the Edwardian terrace with its narrow layout (top) to the wider suburban plot with the three principal rooms in each corner (bottom). The dining room and living room had now swapped places and the kitchen had moved into the main body of the building.

The principal reception rooms in a house had changed their roles and positions over time. In the imposing Georgian and early Victorian urban terrace house these main rooms had been raised up on the first floor and at least accessed up steps above a half basement. In the late Victorian and Edwardian house where the service rooms were now sited at the rear rather than below, guests were received and entertained in large ground floor rooms. These usually included the dining room, a male-orientated space with rich colours and dark wood decoration, where the gentlemen would remain after a meal, or move to a separate smoking or billiards room in the largest houses. The ladies would retire to the drawing room, decorated with a lighter feminine touch and often overlooking the rear garden.

More modest middle class houses would imitate this arrangement with a dining room or parlour at the front for special occasions and Sunday family meals and a drawing room for everyday use at the rear. For those further down the social scale, if they were fortunate enough to have a house with two ground floor rooms, the front room was reserved as a parlour and the family were crammed into the rear living room.

During the inter-war years this began to change as the use of rooms became less specific. The largest houses may still have retained a number of extra rooms – perhaps a study, library and a separate dining room for everyday meals. In the average semi or detached suburban house there were just the two main reception rooms. The front one became a multi-purpose living room although many families still locked it up and kept it for special occasions. The dining room moved to the rear and either had a separate kitchen next to it, often accessed through a serving hatch, or in smaller houses contained the kitchen within (a dinette or kitchenette).

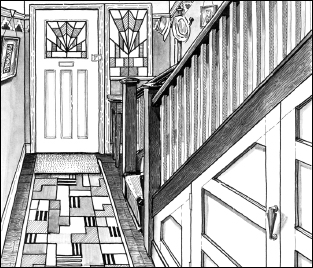

The Hall

One key feature which remained the same was the hall, the larger and more impressive the higher your social standing. With a wider plot much of the extra space gained was spent on enlarging the hall, so they are more open than the rather narrow Edwardian version. This gave the builder the opportunity to fit stairs with a newel post and balustrade with, if possible, a turn at the bottom to emphasize the width of the space and imitate the entrance to a grander house.

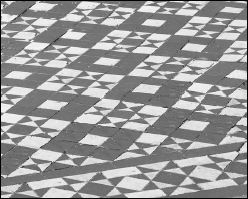

FIG 6.3: Some halls still had geometric tiled floors fitted, as had been the fashion in Edwardian houses. Black and white patterns, as in this example, were popular.

To lighten the hall a window was fitted to one side of the front door (the outer side usually facing the stairs), or in some cases on both sides. This somewhat replaced the fanlight, which was rare as the ceiling heights were now lower, although some were squeezed in as part of the semi-circular porch.

Towards the top of the stairs there was a window on the side wall illuminating the landing. As the privacy of the family going to bed was important this window was always fitted with opaque or coloured glass patterns. If the original has been retained it can be one of the most impressive features in the house with elaborate patterns and rural scenes often featured (see FIG 4.24).

Where room permitted, a coat stand and a small table were positioned, usually in the space at the bottom of the stairs. The table was used more for putting calling cards or other small items on rather than a telephone, which was still a luxury in most middle class homes at this date. The under-stairs space might have a small cupboard accessed from the hall in the lower part but usually most of it was used for a larder or store cupboard accessed from the kitchen, or in some houses a coal store with a door on the outside.

FIG 6.4: A typical hall from a 1930s semi-detached house.

Some hallways were decorated in similar styles to houses before the First World War. There could be a painted embossed paper below a dado rail providing protection for the wall, and geometric patterned floor tiles. In others wallpaper below a picture rail and a carpet runner along either a solid surface or floorboards could be found; fully fitted carpets in the hall and up the stairs were a luxury beyond most pockets in this period.

For those working class families moving from a small rented house where the door opened directly into the front room, the hall of a 1930s semi or terrace must have made a great impression.

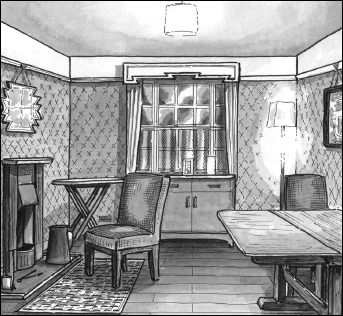

FIG 6.5: A living room from a 1930s semi-detached house with an eclectic mix of modern wallpapers and a radio, traditional furniture and the family piano.

Living Rooms

The term ‘living room’ had formerly been used to describe the everyday back room in smaller houses before the war but was now more widely associated with the one at the front. This general term was more appropriate as it was used by families in different ways. Some kept it traditional, creating the parlour they had always longed for and reserving it for special occasions, while others made it a peaceful sanctuary or study. It is likely that most used it principally as a sitting room but by putting a table here or a writing desk there made it a multi-purpose space.

There would have been a fireplace, generally less ornate and imposing than before, usually with a hanging mirror above (rather than built into an overmantel as had been the fashion before the First World War). Behind this in many homes would have been a back boiler to heat water, which would rise up to a tank on the floor above, usually in an airing cupboard (see Kitchen for alternative arrangements).

FIG 6.6: A living room from a smaller local authority house with a simple cast-iron fireplace and basic furniture. This was still a large step forward for most families moving out of slum dwellings.

Upholstered chairs and settees could be in traditional styles but more often by the 1930s were in distinctively low and boxy forms, most with loose covers for ease of cleaning. The most notable piece of furniture would be the sideboard, which could reflect the latest in fashion with curved corners, a stepped shape and Art Deco-styled handles. Larger houses could have fitted in a cocktail bar or drinks cabinet, while the better-off could afford an early radiogram. There might still be a table and chairs in some if it was to be used for dining on special occasions, a writing desk, which like the sideboard could reflect modern curved forms, and a piano was still a popular fitting.

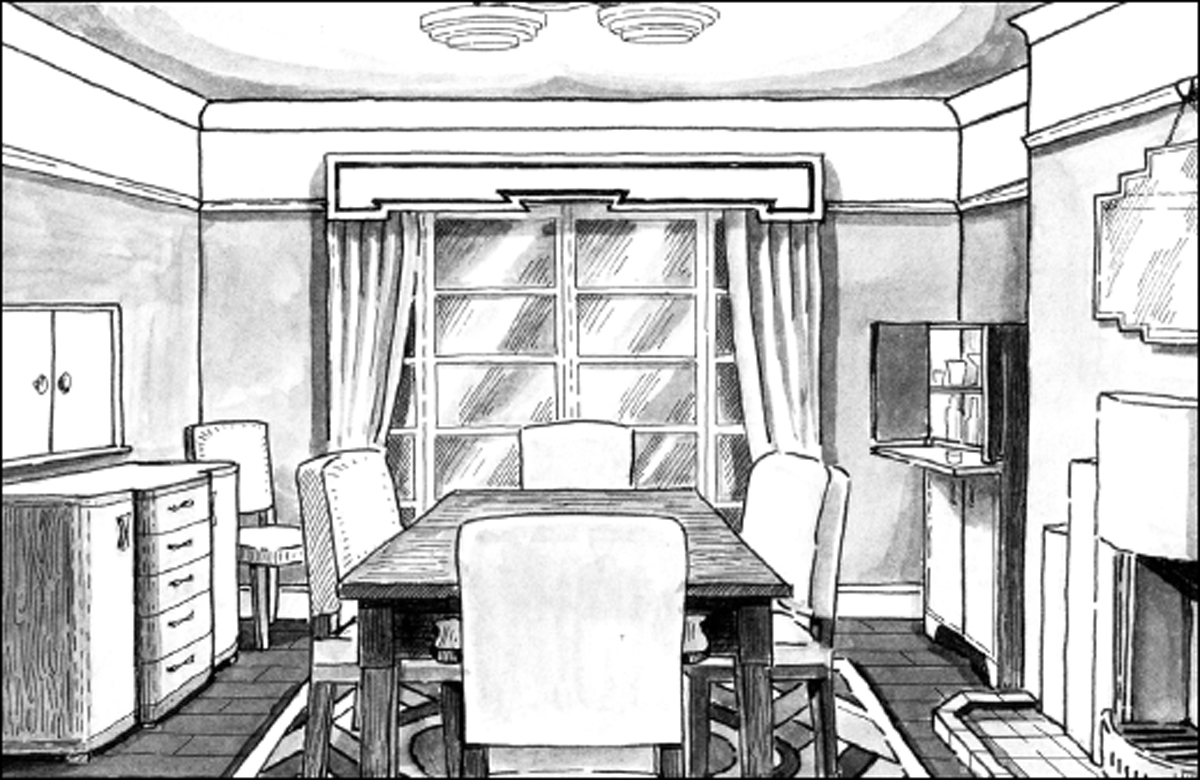

Dining Rooms

The main room at the rear was assigned to the dining room, although in the medium and small house it again could be a flexible space used for many tasks. In the larger houses there would have been a table, chairs, and a cabinet or, in more modern examples, built-in cupboards. This traditionally was a male room and many would have reflected this with strong colours and, in the finest Mock Tudor dining rooms, a beamed ceiling.

In the standard semi or detached house there would have been a table, usually a gate-leg or with pull-out leaves, so it could be closed down and pushed up against a wall if required. There would again be a fireplace and a set of French doors opening out into the garden. As it was next to the kitchen a hatch was a new feature which made passing the food between rooms easier – there was still the habit of fitting separate doors to each room off the hall, so it would have otherwise meant passing through two doors to serve food.

FIG 6.7: Beamed ceilings were often fitted in the large Mock Tudor dining room, and although in this house it is now used as a lounge its original use can be traced by this feature and its location next to the kitchen.

Kitchen

The kitchen, of all rooms, probably witnessed the greatest change from the century before. In the late Victorian and Edwardian middle class home it had to be large and tall enough to house the cast iron ranges used and the heat they produced. These were set within a large fireplace and were notoriously temperamental, dirty and greedy of fuel, so ample coal had to be stored close at hand. There was typically a central table, with a dresser and shelves around the walls for storage. In most larger houses there would have been a separate scullery for washing and cleaning (any water supply in the kitchen was generally used for the cooking process) and a larder and possibly a pantry. Smaller houses before the First World War often had a small range in the rear living room where any cooking was done, and just a separate scullery in a rear extension or as a communal block outside.

FIG 6.8: A dining room from a 1930s semi-detached house, with French doors leading onto the patio.

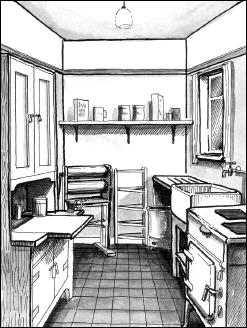

FIG 6.9: Drawing of a kitchen from a larger semi or detached house. Although it is smaller than those before the war, it still manages to squeeze in all the requirements with clever storage and modern appliances, enabling processes like washing to be performed in a small area.

After the First World War some large houses might have continued with the previous layout, but generally the size of kitchen got smaller during this period. Ceiling heights were lowered as ranges were replaced by cleaner, free-standing cookers and new appliances set around the room, as just the lady of the house performed the cooking rather than a number of servants. There would still be a separate scullery for washing and a small larder, though with ample local shops and improved care of foods, including the first refrigerators for the well-off, the need for storage was reduced.

In most modest 1930s suburban semi and detached houses the kitchen was set in the outside corner behind the stairs and next to the dining room and was often no wider than the hall. As both cooking and washing could now take place here, there would have been a large belfast or butler white ceramic sink with a wooden (often teak) drainer to one side, usually just supported by brackets or a post. The space under the drainer was often used to store a copper, a large heated metal vessel used for washing clothes. Either fixed to it or standing nearby would have been a mangle with wooden and later rubberized rollers to wring out the wet clothes.

FIG 6.10: A kitchen from a smaller house which still has most of the requirements for cooking and washing and was a big improvement on the old all-in-one living room which many in this class would have endured in the past.

Improvements in the performance of both gas and electric free-standing cookers meant they were preferred to solid fuel ranges in most new houses. Enamelled surfaces inside and out (mottled black and white at first with colours introduced in the 1930s), glass doors, thermostatic controls and a body raised up on legs made them cleaner and easier to use than older ranges, an important consideration as most families no longer had a cook and maid. In larger houses the new Aga became popular in the 1930s, providing much more efficient performance than older solid fuel cookers and constant hot water in addition.

Smaller houses tended to have a separate boiler in the kitchen, a compact floor-standing model like an Ideal (usually on a red tiled base, some of which can still be found). Most ran on coke or coal with a small flue running up to the chimney from the rear, and access top and front to load it and clean out the ash. They provided hot water for the whole house via a tank upstairs and could also burn a large amount of waste. A cheaper-to-install option was a wall-mounted electric heater (like an Ascot heater), which was positioned above the sink with a separate one in the bathroom.

FIG 6.11: The Aga was introduced in 1929 as an improved, more efficient type of solid fuel range, and was popular in large, remote houses without access to electricity and gas.

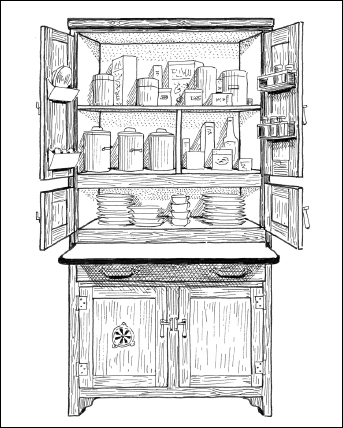

FIG 6.12: Tall, slimline, built-in or free-standing cupboards were a distinctive feature of 1930s kitchens. They were ingenious storage devices and could feature drop-down ironing boards, pull-out tables, and door-mounted spice racks, details that are still regarded as luxuries in today’s fitted kitchen.

Another distinctive feature of 1930s kitchens was a built-in or free-standing cupboard. These were thin wooden structures with a couple of doors and drawers below a small worktop (sometimes with a pull-out or -down table) and two large doors above. Small vents were often fitted in the door where food was stored. They were clever multi-purpose storage areas, some larger more elaborate types even featuring hidden ironing boards and pull-out racks. Most were exposed wood or painted white, though doors could be finished in pale green or blue. Although there was often a small drop-down table for preparing food there would have been few other work surfaces as there were no appliances and gadgets other than perhaps an electric kettle or toaster to make these necessary. The appearance of the room would seem rather disjointed compared with today’s built-in kitchens.

More modern kitchens featured in articles and exhibitions at the time might have begun to appear in part in some later homes. Silver-coloured metal sinks, enamelled work tables, built-in furniture and the latest appliances like washing machines, refrigerators and even water softeners were all available but not widespread at this date.

There was little space for decoration in the kitchen. White glazed wall tiles half way up the wall, occasionally all over, were common, with walls painted in an oil-based paint above. The floor usually had red quarry tiles if solid or could be covered in linoleum if on boards.

Larder

Most houses still had a larder for food storage, which could range from a simple wooden cupboard in a corner to a narrow separate room with stone and wooden shelving and meat hooks. It was important for it to be sited on a side or rear wall out of direct sunlight with a small window for ventilation, covered in gauze to keep flies out. In the standard suburban house it was often positioned beside the back door, under the stairs or just inside from a rear lobby (but separate from a ground floor water closet due to health risks).

In the past, larger houses had cold stone shelves in the larder and ice boxes (cupboards with a side compartment filled with ice to keep the other half cool). Now they had the option of a refrigerator, which grew in popularity after limitations were imposed on preservatives in food, so that by the hot summers of the mid 1930s they could be found in perhaps one in 50 homes. They either operated on a compression system, with a mechanical pump as in modern fridges, or by absorption, relying upon rising heat to set the process of cooling the container under way. They were large bulky items, often raised up on legs with metal cases insulated by cork and having a small internal storage space.

FIG 6.13: Examples of traditional larders from larger houses with tiled floors, wooden and stone shelves, the latter for keeping produce cool when there was no refrigerator.