CHAPTER 4

Traditional and Moderne

FIG 4.1: A row of semi-detached houses with modern features like suntrap windows and a white rendered finish, yet underneath they are little different from the ones on the same estate featured in FIG 3.1.

During this period the style in which a house was either built or marketed was, in the majority of cases, a traditional form although later Moderne features became fashionable. Although the more expensive properties were actually shaped by these fashions, the vast majority of inter-war houses erected by speculative builders just had the style applied to standard structures. A window, door or certain finish of wall was all that was required for it to be marketed in the chosen style. Some were bristling with decorative features, others displayed virtually none, while many borrowed from different sources to create eclectic compositions which riled critics but entertained buyers.

FIG 4.2: A Traditionalist house dating from 1912 that displays many historic forms like the black and white timber-framed gable, tall red brick chimneys and long mullioned windows, and owes much to the early work of Sir Richard Norman Shaw and Sir Edwin Lutyens.

Before looking at the dominant style of the period it is worth turning briefly back to those that preceded it to understand where the credit for much of it lies, how the inter-war fashions varied from them, and to appreciate the impact the modern style must have made when it first appeared in the suburbs.

Victorian and Edwardian Styles

For much of the 19th and early 20th century the inspiration for the style of houses came from the past. Fashions from the continent and modern materials were generally rejected in favour of traditional forms and detailing. Familiarity and history were dominant in an insular nation fearful of foreign influence. In a time of great change and inventiveness, the home front was seen as a sanctuary from the fast and, to some, frightening pace of modern life.

FIG 4.3: This small house built from local stone in the form of a lodge or gatehouse was designed by C.F.A. Voysey in 1908 for Arthur Simpson, an Arts and Crafts woodcarver. Note the large semi-circular recessed doorway behind the gate, a feature which was copied by speculative builders in the inter-war years.

A fight between camps promoting in one corner the Classical style and in the other the Gothic, dominated mid-Victorian fashion. This became less of an issue to the next generation of architects who stepped out of the ring and into the country as old manors and farmhouses became the source of inspiration. By the turn of the century suburban rustic cottages with oversized steep sloping roofs, Queen Anne houses with red brick and white painted woodwork and pseudo-Tudor, Elizabethan and Jacobean structures with fake timber framing and towering chimneys were the historic styles of choice. For the majority of terraces, which still dominated the housing market at the time, builders dipped into this box of past delights and created eclectic arrangements of detailing upon their standard house forms.

Arts and Crafts and the Garden Suburbs

The most influential group at the time, who were in part to shape domestic architecture, were those working under the banner of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Its origins lie back in the mid-19th century with the work of William Morris and John Ruskin who sought to improve the standard of design and status of the craftsman from being crushed under the wave of industrialisation. These socialist idealists looked back to the art and traditional rural crafts of Medieval England as both an appropriate style and a period of honest workmanship. Their writings and lectures inspired the next generation of designers and architects to embrace vernacular and traditional methods, materials and styles in their work and to keep an honesty in its form and function. Many joined new guilds and societies, which arranged exhibitions and promoted their work, or even established utopian communes based around their Arts and Crafts ideals.

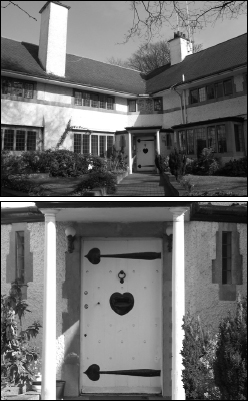

FIG 4.4: Arts and Crafts features like tiled hipped roofs, pebbledashed surfaces and large porches recessed into the building were copied on the mass housing of the 1920s and 1930s.

Many of the new houses copied features from 16th and 17th century houses and incorporated them into their own designs. In the early work of great architects like Sir Richard Norman Shaw and Sir Edwin Lutyens, red brick and timber structures capped by low-slung roofs celebrated the rustic and local forms of ancient houses they sketched in their home counties. In the hands of architects like C.F.A. Voysey and M.H. Baillie Scott these historic sources were adapted into new forms, creating a finished building that was remarkably modern.

FIG 4.5: Annesley Lodge, North London: This house built in 1907 by C.F.A. Voysey was inspired by buildings of the past but readapted features to create modern forms, which influenced architects in the inter-war years. The lower picture shows the door with elongated strap hinges featuring the architect’s favourite heart-shaped motif, as Voysey designed from the whole down to the part.

These leading designers also worked from the whole to the part, planning not only the main structure but also the minutest detail like a door handle or hinge. Although there are many variations in Arts and Crafts houses the general theme which most worked to was the use of local materials that were fit for the purpose, traditional methods of construction, and letting the demands of the interior shape the exterior.

However, the fittest materials usually cost the most so products were very expensive and without mass production could not reach the general public as had been intended. C.R. Ashbee summed it up when the Guild of Handicrafts was being wound up in 1907 by commenting that ‘we have made of a great social movement a narrow, tiresome little aristocracy working with great skill for the very rich’.

FIG 4.6: Simple, spacious houses with a touch of the rustic, including dormer windows and a tile-hung jetty, at Letchworth Garden City.

FIG 4.7: This house from Port Sunlight on the Wirral could sit quite happily within an Edwardian or inter-war estate with its Arts and Crafts decoration, tile hanging, hipped tiled roof, leaded light windows and shallow angled buttresses.

In the Edwardian garden suburbs and at Letchworth Garden City it was the style created by these Arts and Crafts architects that dominated the housing. Cottage-type buildings with low-slung tiled roofs, wooden casement windows and walls finished in traditional coverings like pebbledash, roughcast, pargeting, tile hanging and timber boarding were erected along spacious tree-lined avenues. They were not afraid, however, to bring in cheaper materials from all over the country, which combined with simple decoration kept the costs down but still created rustic homes that enhanced the rural image they were trying to bring to the masses.

The style of houses inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement and which were erected in garden suburbs before the First World War reappeared after it, especially in the 1920s, with roughcast, pebbledash and tile hanging covering the upper storey as popular features.

Mock Tudor

A distinctive style of the inter-war years that sourced its inspiration from the Traditionalist and Arts and Crafts architects of the late Victorian and Edwardian period was the Mock Tudor. Marketed at the time under Tudor, Elizabethan or Jacobean banners, it used elements from all of these periods to create a distinctive ‘Olde English’ style which customers were comfortable with.

The houses were built of brick, (usually a warm red was preferred), with a hipped roof above covered in clay tiles and timberwork finished either in black or left in a natural mid to dark finish. There was often a shallow projection facing the front with timber framing set in the triangular gable at the top and around the structure below. The infill between the timberwork was either herringbone patterned brickwork or a white rendered covering. The first floor of many was jettied out on timber or brick brackets, sometimes with a square or angled bay window below. A simple pitched porch often covered the doorway, again held in place by brackets or a vertical post. The casement windows were divided up into leaded panes, usually in a diamond pattern, and the dark wood front door was often a solid planked type with vertical strips and studs in an early 17th century style.

FIG 4.8: A selection of Mock Tudor houses with the distinctive black and white timberwork, hanging tiles, red brick walls and leaded light windows.

On the cheaper mass housing where the builder could not afford the full works, just a few elements were added to the standard semi. Fake timber framing with rendered infill in the gable, painted in a number of colour combinations as well as black and white, and tile hanging between the ground and first floor bay windows, were often featured.

FIG 4.9: A drawing of a Mock Tudor house showing some of the distinctive features.

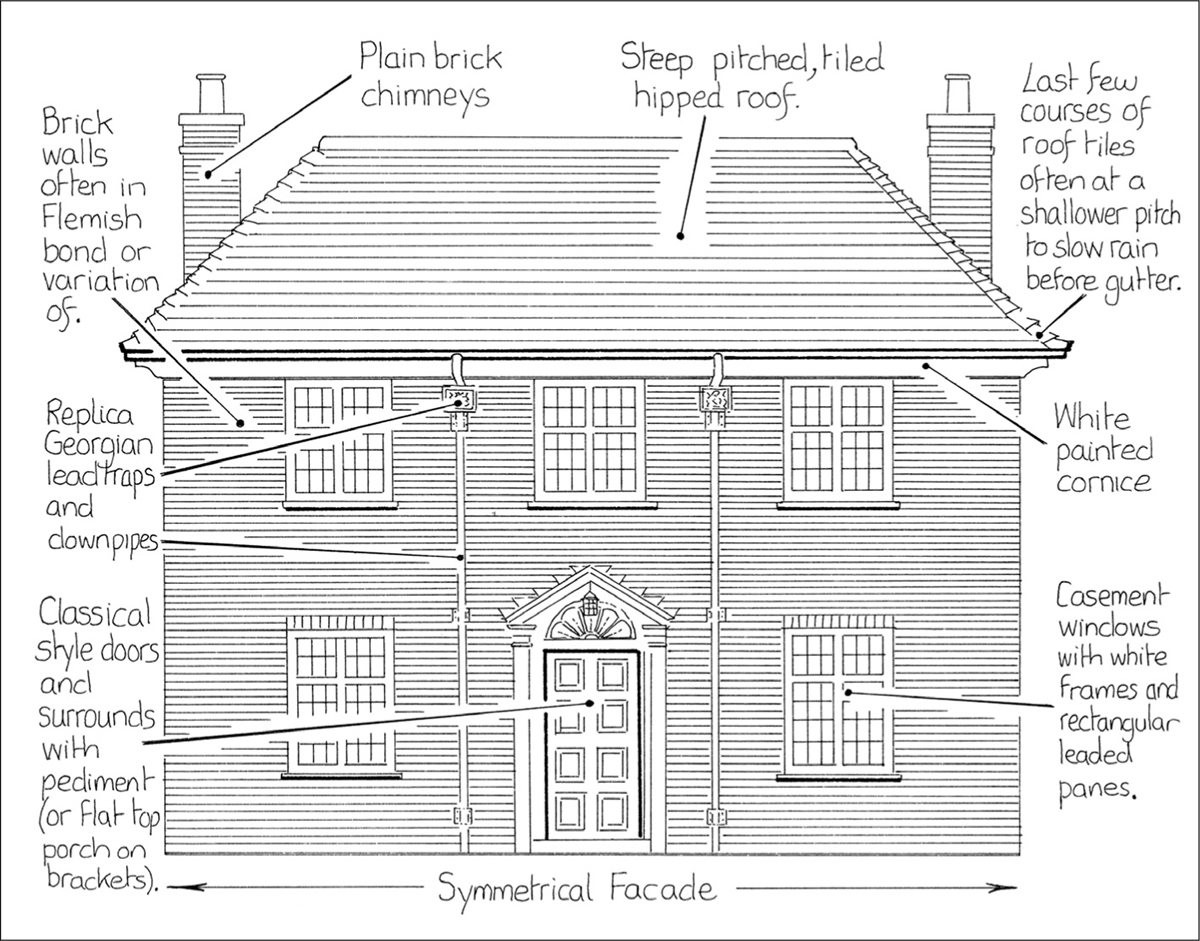

Neo-Georgian

Another popular style which could be found on banks, post offices and public buildings as well as housing was the Neo Georgian. Its origins go back to the late 19th century when, after a period dominated by the Gothic style, architects looked for fresh ideas in the Classical forms of the late 17th and early 18th centuries (William and Mary, or Queen Anne, as much as Georgian). Sir Richard Norman Shaw was one of the first to develop this Classical style later in his career, using the simple symmetrical hipped roof structure for inspiration. Architects like Sir Edwin Lutyens also used this form, based on the more modest house of the lesser gentry rather than the flamboyant Baroque, which at the turn of the century was popular for grand public buildings.

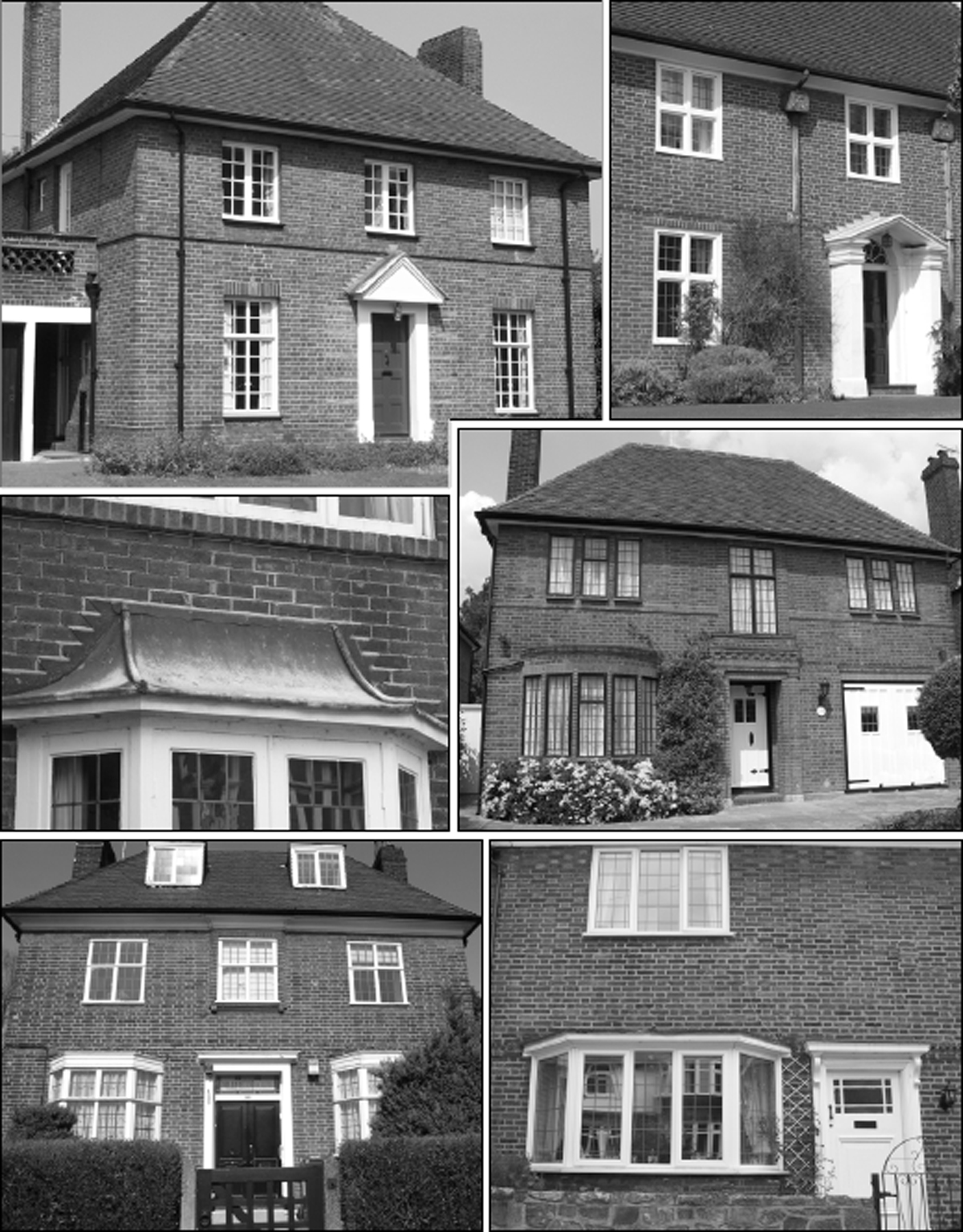

FIG 4.10: A selection of Neo-Georgian houses with distinctive symmetrical facades, twelve or more light sash windows or casements, hipped roofs, and pedimented doorways.

FIG 4.11: A Neo-Georgian house with labels highlighting some of the distinctive features.

After the war a slightly modified version became a favourite style for the more refined property. The facade of the detached or semi was symmetrical, usually in a dark red or brown brick with a hipped, tiled roof. There would have been a distinctive white painted cornice running around under the eaves and white painted casement windows (prewar types usually had sash windows) with rectangular-shaped leaded panes. Original building regulations in the 18th century meant that windows would have been gradually recessed further back behind the outer brick wall, but relaxing of this fire precaution in the 1890s meant that Neo-Georgian windows could be flush with the outer face, and doors could once again be framed by white painted wooden surrounds with a flat storm porch or pediment above.

FIG 4.12: Local authority housing often used the simple style of Neo-Georgian houses with cheaper sash windows to keep costs down, making the style less popular on private houses later in the period.

Due to its simplicity and lack of expensive decoration this style began to find favour for local authority housing. By using cheaper bricks and wooden sash or simple casement windows, a very cost effective house could be built. Due to this, speculative builders concerned that private house buyers wanted something which was clearly a step above council housing used it less in the 1930s. The house with a symmetrical façade, however, was still used but was often finished in white render and decorated with more modern detailing to differentiate itself from cheaper alternatives.

MODERN STYLES

For nearly a century English isolationism and conservatism had kept eyes focused on our past rather than the latest in continental architectural fashion. Then suddenly in the late 1920s, between the mass of traditional Tudor, Elizabethan, Jacobean and Georgian styles, alien forms began to appear, firstly as eccentric individual pieces but later watered down and planted upon the familiar house structure.

This acceptance rather than full embrace of the latest in European and American design may not seem surprising, bearing in mind this was the Jazz Age. However, to the majority whose ideal house was probably some form of rustic cottage and the building societies who funded them, the concept of flat roofs, plain facades, reinforced concrete structures and all that white paint must have been too shocking and risky a purchase.

The origins of modern architecture go back to the beginning of the century and individual designers working under the general umbrella term of Art Nouveau. They were looking at nature for inspiration with sinuous figures and whiplash floral motifs characteristic of the style. In this country its foreign form made little impact on housing except in stained-glass window design and some interior pieces like Tiffany lamps.

FIG 4.13: Art Nouveau was a popular form of decoration in the 1890s and 1900s in either its sinuous and curving form, like the whiplash handles (top) or the more geometric patterns popularised by Charles Rennie Mackintosh as in the glass window (bottom). Art Deco and Modernism were in some ways a step forward from this and a rejection of it.

It was, however, from these shores that much of the inspiration that would drive the next generation of designers would originate. Many of the ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement and William Morris before them were taken up by new groups on the continent, but it was the work of the Glasgow School of Art and Charles Rennie Mackintosh who used stylised geometric rather than sinuous forms from nature, who were most admired. In Vienna, designers, including Josef Hoffman and Adolf Loos, were experimenting with rigid geometric forms and stepped masses. In France the Cubists created abstract images, while in Germany Walter Gropius formed the Bauhaus in 1919, which embraced new materials and used horizontally arranged windows of plain glass. This period after the war saw pioneering art work where any sense of reality in a painting was replaced by bold black grids and rectangles of primary colours. Architects began using new materials and experimenting with their qualities and the potential they gave to free them from the constraints of traditional building.

In 1925 an exhibition that would showcase the work of these and other designers finally opened its doors. The ‘Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes’ in Paris (from which the term Art Deco was coined) was intended not only to display the latest in design from around the world but also to promote French artists and craftsmen who had traditionally been at the forefront of European style. It was a notable turning point in the move away from the highly ornate, romantic, and historic styles of the past to modern methods and materials in construction and decoration. Britain only made a halfhearted representation and the rather conservative America boycotted it, feeling that the country lacked the necessary talented modern designers to meet the exhibition committee’s criteria. Despite this it was the USA, aided by emigrating European designers, which became one of the leading lights of modern design.

In a book this size the various, and detailed, strains of modern architecture have to be crudely condensed and categorized for simplicity and there are many grey areas and similarities between them. Ultra Modern, Modernism or the International Style was at the cutting edge of design, with architects using reinforced concrete construction, horizontally aligned structures and an emphasis on light and health. Moderne was often used here to market the standard semi and detached speculative-built houses which featured elements used by leading architects working in the International style. Art Deco is a more recent phrase used at first to describe similarities in the modern-style decorative arts throughout the period but now a term in common use for any non-traditional forms in the 1920s and 1930s and hence much of the above styles.

Modernism or Ultra Modern

Modernism was to many of its advocates as much a social movement as revolutionary architecture. The designers who preached its gospel envisaged a bright and healthy world for all classes and embraced new materials and forms of construction that would enable them to achieve this. They rid their buildings of decoration and historical references, and looked forward, inspired by the new machine age and products like cars and planes. The shape of their buildings would be controlled by the function required of its interior rather than the need for symmetry in the exterior. The movement’s leading light, the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, famously stated that houses should be ‘machines to live in’.

FIG 4.14: High and Over, Amersham, Bucks: It was a shock in 1930 to the residents of leafy Bucks to find this modern, stark white house rising above the trees. Its Y-shaped plan had living and dining room, library and kitchen on the ground floor and bedrooms above with a sun terrace on the top. It was designed by Amyas Connell for Bernard Ashmole, Professor of Archaeology at London University, using a reinforced concrete structure, although the walls were rendered brick.

In this country Modernism’s impact was limited, the few houses built were for wealthy individuals often viewed by the public as left-wing and liberal idealists. Architects including Wells Coates, Amyas Connell and Berthold Lubetkin were among the few working in this Horizontal or International style, as it was often referred to. When Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933 he closed down the Bauhaus and, fearing persecution, many Modernists fled to England, potentially boosting its cause in this country. Many left in 1936 for America after finding the same prejudices and reluctance for change here, but not before leaving their mark.

Modernist houses pioneered the use of steel-reinforced concrete in housing. The geometric structure was controlled by the use envisaged by the owner or architect, and typically embraced the sun, planning the house with as much glass facing southwards as possible. Dark-coloured window frames created abstract patterns with the white external walls, their position though being determined by the needs of the room they illuminated rather than the arrangement of the facade. In some later examples, internal vertical posts took much of the weight so that the exterior wall spaces could be filled with non-structural materials, mainly horizontal bands of glass.

FIG 4.15: The Isokon Building, Lawn Road Flats, North London: Designed by leading Modernist architect Wells Coates and opened in 1934, this block of apartments in unornamented white concrete could be refered to as an ocean liner in the city, not only with its sleek looks but also in the residents it was designed for. These were intended to be young professionals with few belongings around whom the building was shaped with sun terrace on top and communal restaurant on the ground floor, with service more like a modern hotel than a block of flats.

FIG 4.16: This house in Gidea Park dating from the mid 1930s was designed by Berthold Lubetkin, one of the leading exponents of Modernism in Britain whose most famous work is probably the penguin enclosure at London Zoo. Using reinforced concrete, freed the architect to create new forms and there are few more modern houses than this with its open sun terrace and pierced white walls.

The strong reinforced concrete slab roof meant the flat space on top could be used as a sun lounge area, often with a concrete slab canopy above, in effect another floor, although the English weather limited its use. The inside was open planned with moving partitions, giving the owner flexibility in the use of rooms. New frosted glass and glass bricks were frequently used to increase the light in a room or hall.

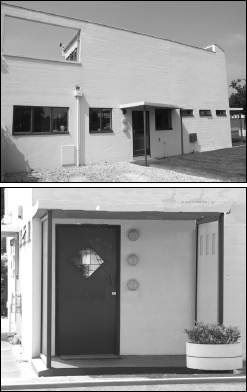

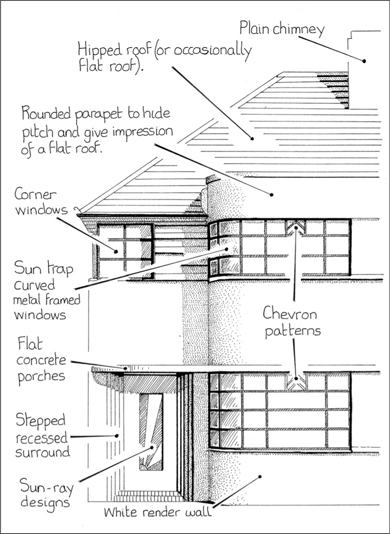

Moderne was a contemporary term originating from America for differing strands of modernism. In England, however, it seems to have been used mainly by speculative builders to market their standard-planned semis and detached houses which had been decorated with some of the more acceptable features from the Modern movement. It is these bright, streamlined suburban houses that are the most familiar face of 1930s modernism, albeit watered down and missing the social point!

Exteriors were usually rendered and coloured white to simulate the concrete structures but the need for regular repair and repainting meant that many were still built in brick. Streamlining became an obsession with designers in the 1930s (although it turned out to be of little actual benefit even on a speeding train like the Mallard) and was incorporated into the Moderne house with metal framed, curved bay windows which caught the sun (suntrap windows) and horizontal glazing bars and decorative bands in the render. Smaller windows in a variety of geometric shapes were popular, as were angular projecting types.

New materials and mass-produced parts appeared in the form of simple metal rails along balconies and around doorways, and pieces of preformed concrete slab for features like porches. Some did have completely flat roofs over the house, the advantage being this could create a sun terrace if there was room, and it saved the builder the cost of erecting a more complicated hipped structure. However, the majority of the public were sceptical and most builders stuck with a tiled roof, perhaps with a raised parapet around it to give the impression from the ground that it was flat. Fearful that the plain facade might also put potential buyers off, extra decorations in the form of Art Deco motifs were often added to enliven it.

FIG 4.17: A Moderne house with labels highlighting some of the distinctive features.

FIG 4.18: Metal-framed windows with horizontal bars were popular on Moderne houses.

FIG 4.19: Houses with Moderne features, including metal-framed suntrap windows, plain horizontal bands, and plain styled doors. Some played safe and used hipped roofs and brick walls but others took the risk of using flat roofs and white rendered or concrete walls.

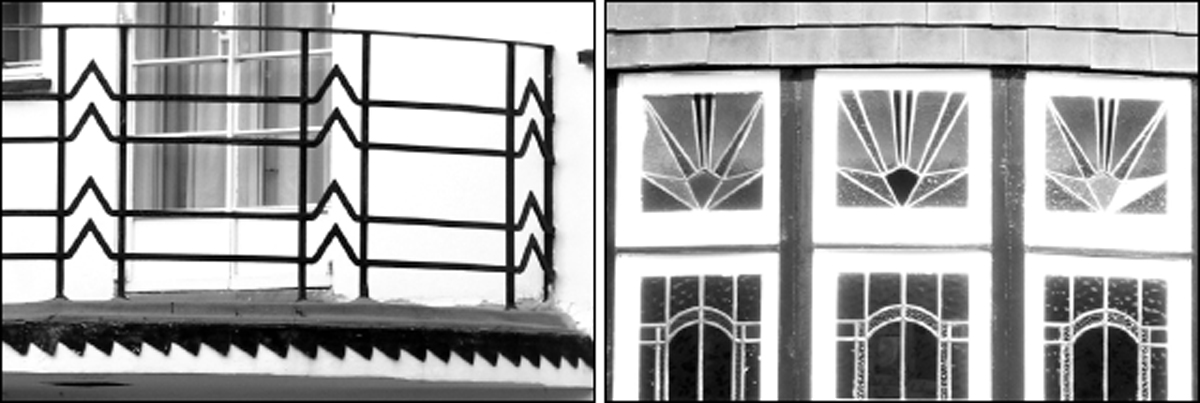

Art Deco is a term that came into popular use from the 1960s after a revival of the famous 1925 Paris exhibition. It was used to describe the wide range of styles in the decorative arts, furniture, interior design and some elements of architecture during the inter-war years. It ranged from luxurious pieces of high craftsmanship to modern forms inspired by ancient history and mass-produced and streamlined features. Factories, cinemas, hotels and bars were often fitted out in this decorative style, which was more readily acceptable to the English.

FIG 4.20: The Hoover Building, Western Avenue, London: This iconic Art Deco factory was designed by Wallace Gilbert and completed in 1932. Its colourful facade of glazed surfaces and chrome detailing has been saved by converting it into a Tesco supermarket.

FIG 4.21: Decorative railings and patterned glass with Art Deco chevron and sunray motifs, which appeared on many Moderne houses.

FIG 4.22: Houses inspired by images of West Coast America featured white rendered walls, green pantiled roofs and Art Deco motifs.

The earlier phase of Art Deco was inspired by a re-evaluation of primitive art and recent archaeological discoveries, especially the unearthing of the mummy of Tutankhamun in 1922. Stylized forms of Ancient Egyptian, Aztec and Chinese structures and decoration are characteristic of the 1920s. In the following decade it was images from the machine age and geometry in nature that became dominant. Chevrons, zig zags, lightning bolts, and the iconic sunray represented a bright and bold future. Streamlined forms inspired by trains, cars and ocean liners appeared on objects in the workplace and house while their simple geometric shapes were more easily reproduced on a mass scale in new material like bakelite.

Few 1930s English suburban houses were built completely in what would be termed Art Deco, it was more typically applied to standard structures with distinctive shaped features and decorative motifs: metal-framed windows with chevron patterns, raised geometric emblems in the light-coloured rendered exterior and the sunray which appeared in window glass, front doors and garden gates. Monumental door surrounds simulating ancient temple entrances (see FIG 1.7) on a minor scale and decorative zig zag and linear patterned railings along parapets and balconies were also popular.

In the later 1930s new houses in what was referred to as Hollywood Moderne emerged, inspired by bright and bold low level housing from America’s West Coast that appeared on the silver screen. Houses, but especially bungalows, were built with white rendered walls, dark coloured window frames and glazed green or blue pantiles. This latter feature is distinctive of the 1930s and appears as a startling splash of colour on many white rendered houses of the age.

Period Details

It is likely that the majority of houses built in this period, especially on the mass market, used only a few elements from these various styles and often a number from different ones together on the same building. The following section simply shows the many types of external features and decoration that might help identify the date or be useful if you are restoring a house to its original state.

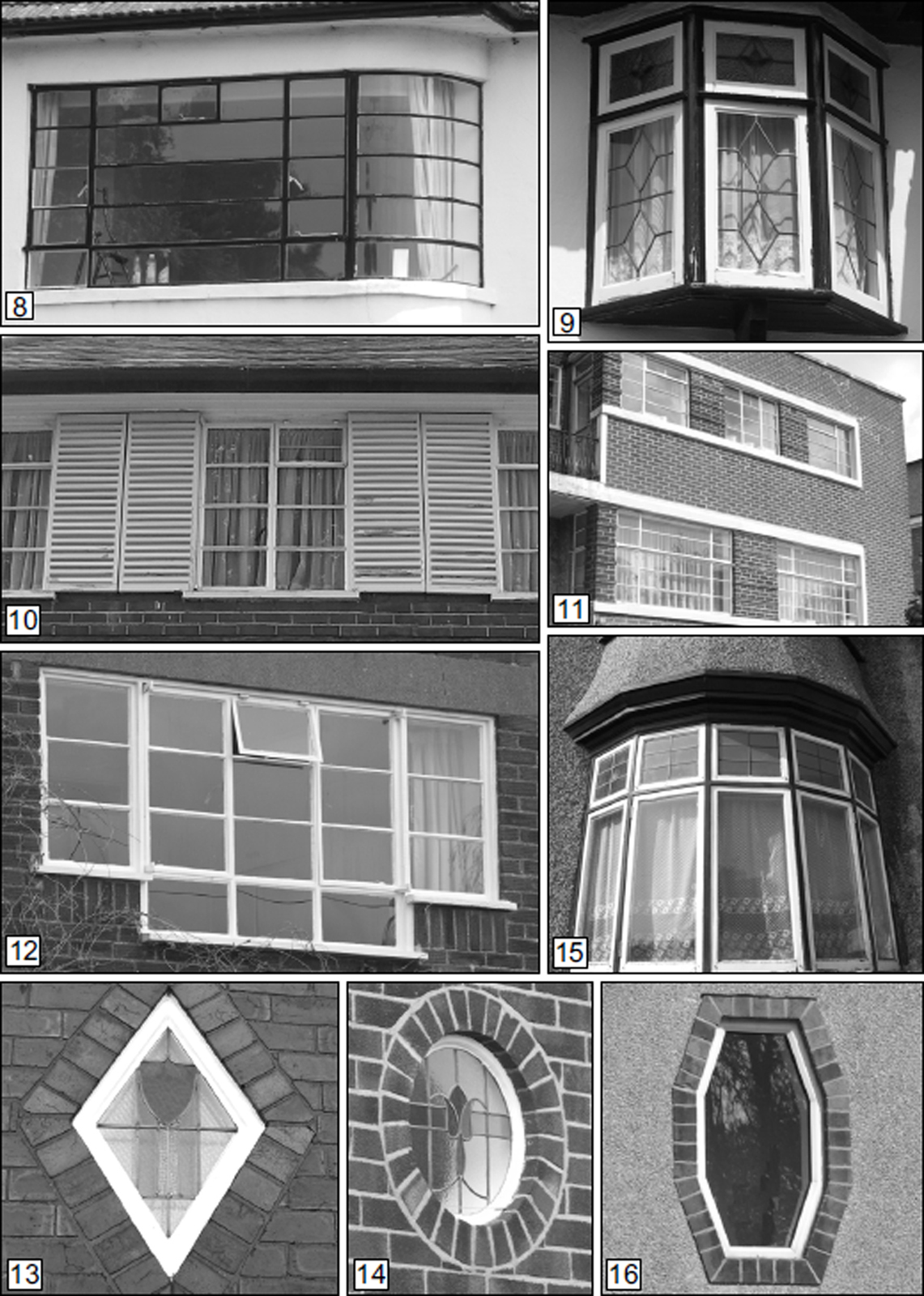

FIG 4.23: Windows: Metal-framed windows were popular although the constant maintenance they required put some off long-term. They typically have long horizontal glazing bars with only a few vertical members in Moderne housing (4, 11, 12) or were divided up by individual leaded panes on Neo-Georgian. Wooden casement windows with a fixed frame and a few opening sections (casements) were found on many speculative-built houses. They usually had a single horizontal bar near the top creating a top row of small windows (15), which were often filled with coloured glass patterns (see FIG 4.24). Sash windows which had dominated good quality housing in the 18th and 19th century were now rare, often relegated to just the cheapest housing or occasionally on some Neo Georgian houses (see FIG 4.12). Small windows in a variety of geometric shapes (6, 13, 14 and 16), eyebrow windows in the roof (5) and dormer windows on some Neo-Georgian houses (7) were popular features in the inter-war years.

FIG 4.24: Stained or Coloured Glass: One of the outstanding features of inter-war housing is the coloured glass patterns in the windows. They can be found in the upper section of front windows (2, 4, 8, 13, 14), in front doors (12) and at the top of the stairs where elaborate designs and rural scenes were often fitted (5). Earlier designs tend to be geometric floral (1, 3, 4, 9, 14) or heraldic shields (8) with more modern Art Deco patterns (11, 12, 13, 16, 17) appearing later.

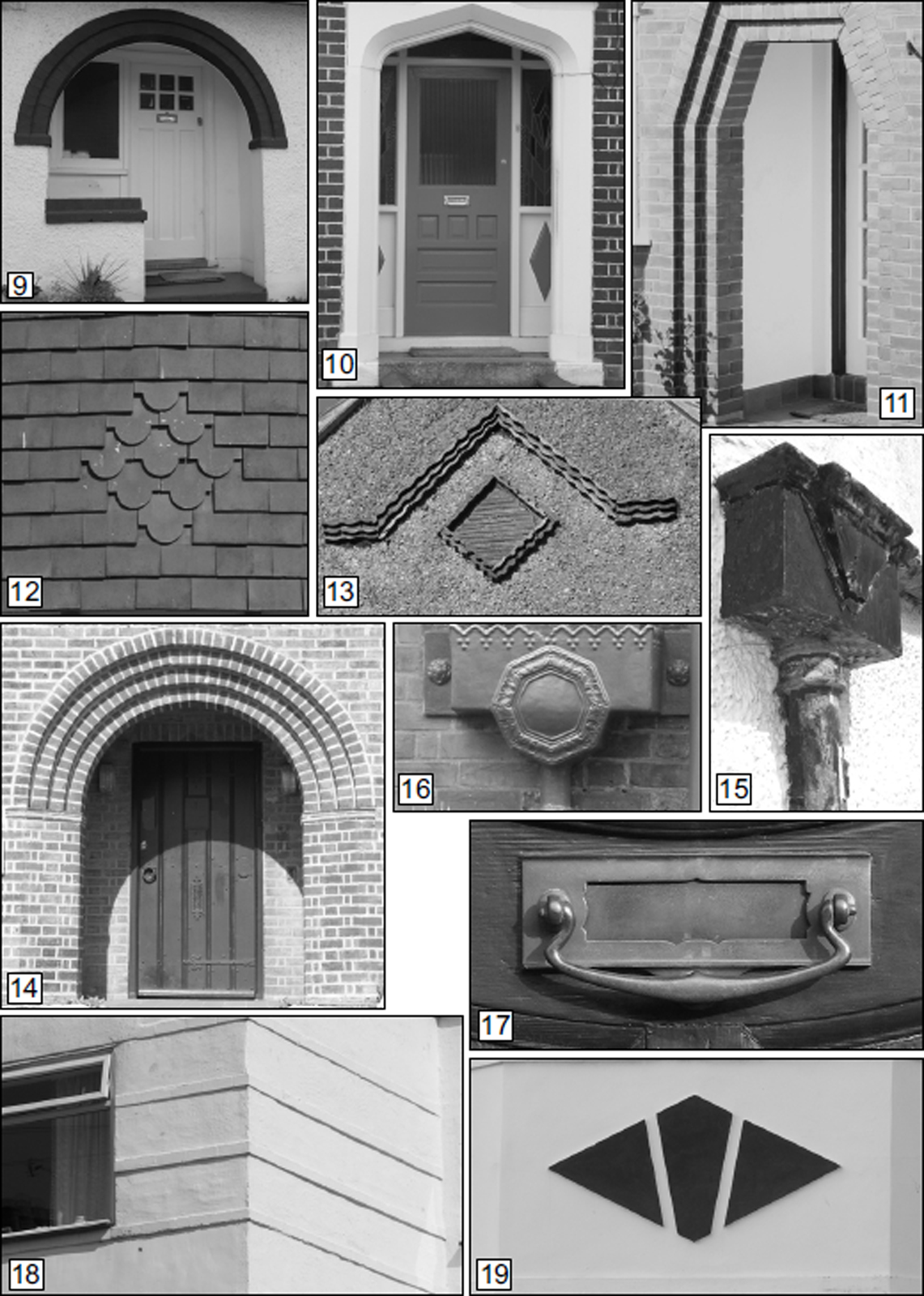

FIG 4.25: Doors: There were a wide variety of designs to match the style of house in either quality hardwoods like oak or cheaper painted or stained softwoods. Tudor-style houses often had solid planked doors with studded vertical strips (2, 4, 13), usually all in stained or natural wood. Classical panelled wooden doors, often painted white, were fitted to better quality Neo-Georgian houses (21). Moderne houses would have simple styles, some with just a vertical glazed panel or a number of horizontal ones stacked upon each other (5, 9, 10, 11, 15, 20). Most houses, however, had a door with a glazed square, round or oval opening in the top third and a number of vertical panels running down the lower two-thirds (3, 7, 14, 17, 18, 22). Maisonettes and flats usually had two or three doors recessed beneath a broad arch to access the separate apartments (8, 16, 19).

FIG 4.26: Gables: Front-facing gables, a distinctive feature of traditional style inter-war houses, were usually finished in a vernacular style. Fake timber framing was either placed in straight vertical lines (4), angled patterns (5, 6) or the popular sunray design (2). Black and white was used on Mock Tudor houses (4) but other colour combinations could be found in the general market (6). Hanging tiles (3, 9), plain render (7) and pargeting (1) – patterns set into the wet cement – were also popular.

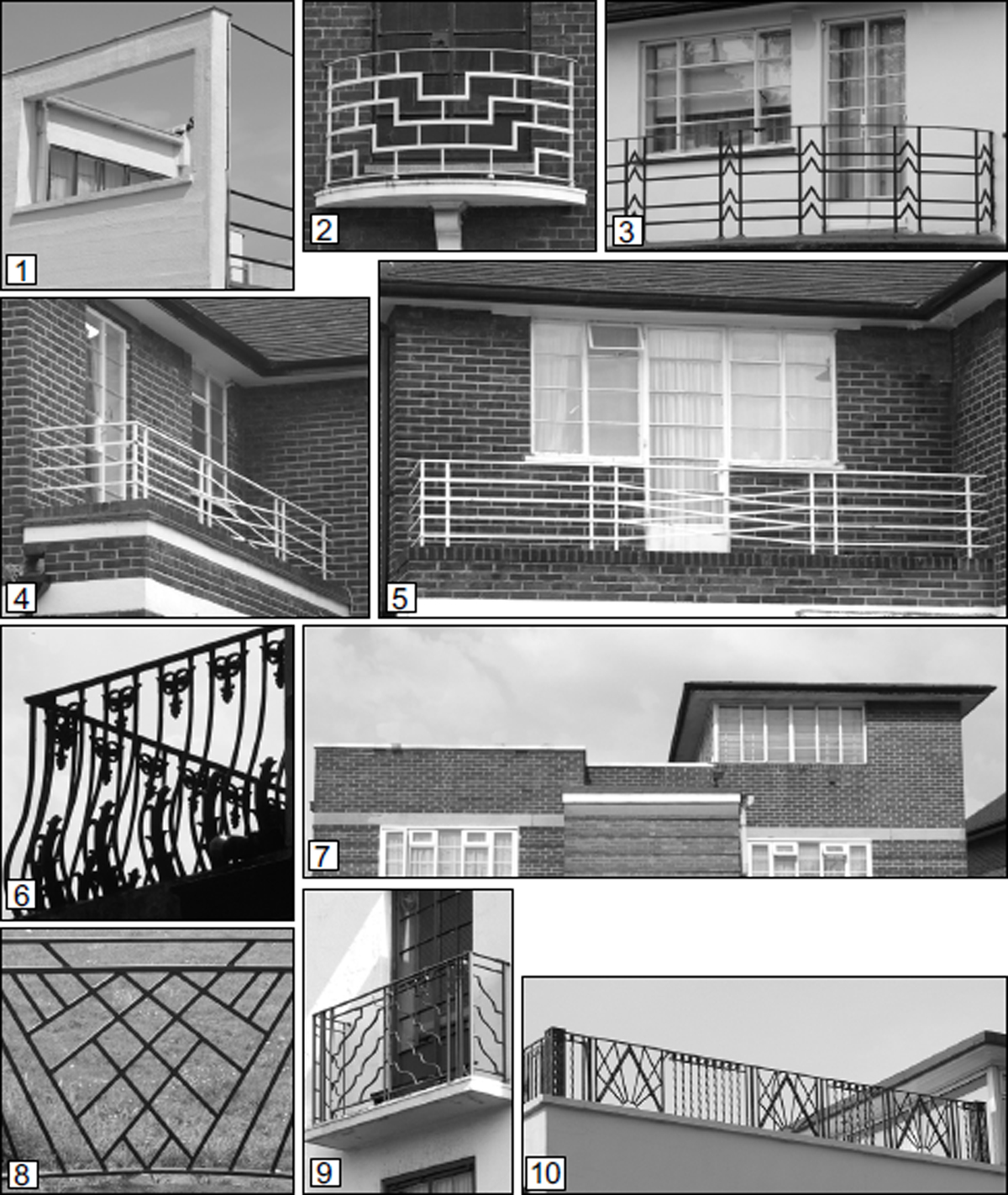

FIG 4.27: Balconies, sunroofs and railings: Balconies, which had come back into fashion in the Edwardian period, remained a popular feature on the inter-war house. Either fitted in front of an upper window or over an extension or bay, they usually had decorated metal railings with Art Deco or Classical motifs, or a wooden or brick balustrade. Balconies and sunroofs on Moderne houses might have just the parapet as a barrier or sometimes metal railings.

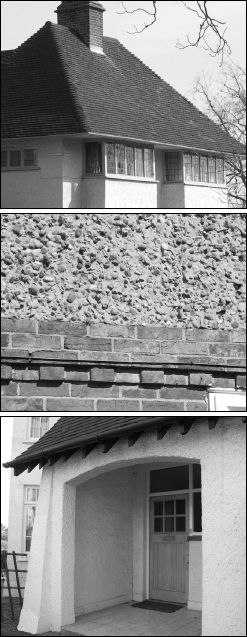

FIG 4.28: Decorative Details: On many houses there were other areas where decoration might appear. Decorative metal rainwater traps were popular (15, 16), some with the date cast into them. The render surface of later houses was often raised to form simple geometric patterns (6, 19), horizontal bands on Moderne houses (18) and Art Deco (2). Raised corners (quoins) were often picked out in red brick (3, 4, 5). Porches were usually recessed under an arch (7, 9) or geometric form on Moderne housing (11) or had receding arches in brick (14).