CHAPTER 9

The Second World War and the Aftermath

The war on the Home Front between 1939 and 1945 was vastly different from that in the First World War. Not only was the populace more aware of foreign events through radio, cinema and newspapers, but they were also now directly in the firing line as Hitler despatched his air force to break the back of British military and industrial strength in preparation for invasion. The Blitz reached its height between September 1940 and May 1941 when centres of manufacturing such as Coventry, Birmingham and Manchester, coastal ports, including Plymouth, Portsmouth and Southampton, and most notably London, were subjected to nightly bombing raids. Many of those new gardens so treasured by families before the war were now dug up for an Anderson air raid shelter, or inside a Morrison type was fitted under the stairs. A pattern of work, recovery and occasional glimmers of escapism at the cinema (where attendances reached all-time highs) contrasted with blackouts and the haunting wail of air raid sirens.

More than 40,000 died in this intense period, with another 20,000 lost during the remainder of the war, many to the terrifying doodlebug V1 flying bombs and the later and thankfully short-lived V2 rockets. The situation was made worse by the large number of injuries and the destruction of more than 1 in 20 houses, which, added to the slum properties which already needed to be replaced, left post-war Britain with a chronic housing shortage.

As America and the Soviet Union joined the conflict and victory for the new allies began to seem more a matter of when than if, attention turned to reconstruction and social reform. Britain’s people had accepted government control but now expected them to deliver the changes outlined in the Beveridge Report of 1942, which proposed that, if we were to rid the country of disease and squalor, state benefits should be available universally upon a single payment taken from salaries rather than by the patchy system governed by means testing used before the war. Just as the poor state of recruits in the First World War had highlighted to the authorities the true state of the nation’s health, so encounters with the children evacuated from the city slums brought home to the benevolent middle classes the deprivation in which many of them lived. This helped soften public opinion to the proposed radical social changes and was one of the reasons why Labour came to power in July 1945 as they were seen as the party most likely to implement the Report.

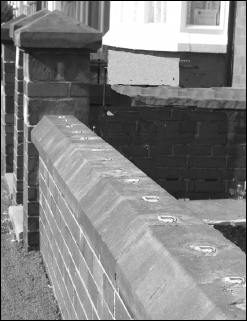

FIG 9.1: Iron railings were ripped out for war production. It is common to see low walls in front of suburban houses with small lead-filled sockets where railings once stood.

The Aftermath

Much of what had been proposed was put into action, if not at the speed expected by voters. The National Health Service came into being in 1948 despite strong resistance to change from many doctors, but the depth of poor health was underestimated as its budget was nearly trebled in the first two years alone. There were few new hospitals in the country and too many out-of-date Victorian buildings. Improved state pensions, family allowances, sickness and unemployment benefits were introduced, although virtual full employment continued for decades to come.

The country, however, was nearly bankrupt. The astronomical cost of fighting the war and the debts incurred meant that even the selling of assets made only a minor dent in the sums owed. Britain was also no longer the major world power it had been at the outbreak of war – the US and USSR had become the dominant forces at each end of the political spectrum.

At home by the late 1940s the public were becoming tired of rationing and austerity – we had won the war after all! The Labour government promoted a Festival of Britain to lift spirits, and despite the plans being mocked by the Conservatives and press alike, the final event in 1951 was a huge success with the public. It is well remembered for the amusements provided, yet its lasting legacy was the promotion of modern design and architecture symbolized by the 300ft pointed but seemingly pointless Skylon. It welcomed in an exciting period of new materials and space-age design, and helped reinforce a growing belief that technology and Modernism could solve problems in society, the most crucial in the eye of the public at the time being housing.

FIG 9.2: The Moorlands Hospital in Leek, Staffs, was typical of the type of outdated Victorian buildings inherited by the fledgling NHS. Like many, this one was formerly a workhouse, dating from 1837, and is still in use as a hospital today.

Post-War Housing

With the loss of such a vast number of houses in wartime bombing raids and the need to demolish others deemed unfit for human habitation, there was a huge and immediate demand for new housing after the war. The problem was intensified by the shortage of raw materials, skilled workers and a slow and tortuous process to approve housing schemes. By the time the Conservatives came to power in 1951 around 800,000 council and 200,000 private houses had been built, the former now with larger accommodation and upstairs toilets. By the mid 1950s output had increased to 300,000 new homes a year (partly due to reducing the size and hence increasing the number of buildings produced) with a shift more towards private housing, and the government making it easier to buy your own home.

Some of the immediate demands for housing in 1945 had been met by prefabs, ‘tin towns’ as sheet-metal types were often referred to, many of them constructed in aircraft factories with empty production lines after the war. Concrete and asbestos were also used as these early post-war council houses had to be quick and cheap to erect and were never intended to last more than a generation (although many are still going strong today some 60 years on).

Private housing picked up in the 1950s but many were built in traditional prewar forms of detached, semis and terraces with reasonably large gardens. They tended, though, to use cheaper materials and forms. Sandy-coloured common bricks were widely used, and simple metal and wood casement windows which appear slightly lower in height were fitted on a generally flat facade as more expensive to construct bays went out of fashion. Gable-end roofs rather than the more complex hipped roof reappeared and, with the advent of central heating and improved electric heaters, chimneys could be rubbed off the drawing board, with just a single flue being required for boilers.

FIG 9.3: Concrete slabs slotted into vertical posts were used in the structure of these houses dating from the 1950s.

FIG 9.4: Many private houses built after the war used similar forms to those before but with lighter, sandy coloured bricks, simple gable ends and flat facades that saved costs and materials.

Economic upturn in the mid 1950s resulted in a consumer boom. Cars, which were still a luxury limited to less than one in ten in 1950, were owned by more than half the population two decades later. The fridge, which had appeared in only the best houses before the war, was widespread by 1970. The biggest change was in the uptake of television, so that nearly 90% of the population had access to one when Neil Armstrong landed on the moon in 1969.

Modernism

The Modernists who had been seen as the extreme and rather eccentric end of architecture before the war were now beginning to influence small and large scale projects. Council and private houses were erected not in the stark white concrete forms of High and Over (FIG 4.14) or the Isokon Building (FIG 4.15), but in a strange British blend of traditional, Scandinavian and European forms. Regular grids of modern-style square block or chalet-style houses with full width windows were Anglicised as well as hanging tiles and painted timber between the floors and brick gable ends!

Local authorities keen to solve the still sizable housing shortage looked for more rapid, large-scale solutions and adopted modernist types of simple concrete structures which were potentially cheap and quick to construct. Early schemes as in Plymouth and Coventry attempted to blend in and complement existing buildings, but by the 1960s as the authorities, architects and town planners grew in confidence some, as in Newcastle, tended to be more ruthless and flatten all that stood before. Large blocks of concrete high-rise flats, which if over five storeys would receive increased subsidies, were a logical use of a limited space. When thoughtfully designed they could prove popular but most were just stacked apartments, erected from sectional pieces of concrete in weeks rather than years and were riddled with problems from the outset. In 1968 four people died as a result of a gas explosion at Ronan Point in London, which ripped out the corner support of one such block, leaving the floors to tumble down like a pack of cards.

Trust in these forms of building was lost as quickly as they had been built and as many Modernists created wackier ideas and sank into a fantasy world, the building fraternity turned back to the more traditional styles of the past.

Conclusion

To glance at today’s housing it would seem that we have come full circle. After all the chances architects had in the 1950s and 1960s to drag the English out of this obsession with comfortable traditional styles, most houses being built today are clad with mock timber-framed gables, hanging tiles and cottage-style windows. The occasional daring dabble with flat roofs, glass walls and concrete structures is viewed with a more appreciative eye perhaps than were similar houses in the 1930s, but most people still prefer pitched roofs, brick walls and some token rustic feature when it comes to parting with their money.

FIG 9.5: Chalet-style houses in straight or staggered lines were modern forms but decorated with more traditional timber cladding and tile hanging.

Some grumble that the modern house is poorly constructed, usually because the floors, stairs and walls in many are flimsier than compared to some in the past and the facade is only made from common bricks with some cheap wood trimming nailed on. This reflects more the demands of the public than short cuts from the builder. A spacious fully fitted kitchen and a luxurious bathroom are more important than exterior detailing to most buyers today. This was not the situation before the war when most effort went into the front elevation and hall, as buyers were more concerned with the status and impression their new home would make on visitors than comforts in the service area. The modern builder also has an ever increasing number of services, interior features and restrictive regulations to cater for in the house which the 1930s speculative builder never had, and far less space to fit it all in as the price of land and limitations on where you can build make it harder to make a profit in what is still a sometimes violently turbulent market.

For these reasons the inter-war house makes an increasingly popular purchase. It was still constructed with many of the good quality materials associated with older houses, and even those at the cheaper end of the market can still have solid walls and floors. The rooms are spacious without being so large that they make heating expensive, as in many Victorian properties with high ceilings. The public face of the house still has a grandeur, style and quality that have been lost in houses since. Perhaps most important of all, they were modern enough to have the standard form of construction, regular sized features and a large plot which means that as most are not yet listed they can be modernised and adapted for almost any size of family.

Now that some of these houses are reaching 80 years of age they are stepping out of the shadows cast by more convenient modern and rustic older housing and are starting to be appreciated as a style in their own right. Large curved bay windows, Mock Tudor timber-framed gables, and Art Deco patterned glass are becoming desirable once again, with even some new houses being erected as direct copies of the 1930s semi! After more than half a century of negative press the inter-war house is finally being appreciated for the sturdy, spacious slightly ambitious home it was always intended to be.