Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.1

This excerpt from “Strange Fruit,” made famous by blues singer Billie Holiday, requires little elaboration. Written in 1937 by Abel Meeropol in recognition of the resurgence of racial violence in the early twentieth century, “Strange Fruit” offers a cutting commentary on the risks associated with being African American in the United States. It effectively captures the abiding threat of the post–Civil War rise of white supremacist logic that declared that African Americans were uncivilized and unprepared for the rigors of citizenship. Despite the persistent threat of violence, African Americans pushed back with determination, creating their own institutions within the confines of an increasingly segregated country, engaging in their own debates about the best path forward toward full citizenship, and embracing new sensibilities about race pride, potential, and progress.

This new phase of African American life in the United States was marked by the end of the federal occupation of the South in 1877 and the end of Reconstruction. The era immediately following Reconstruction became known as Redemption because it involved whites’ attempts to reclaim what they thought had been under attack during Reconstruction. Their South needed to be redeemed.

As Republican governments faded with the departure of federal troops, southerners worked to restore white power. The KKK, which had been wiped out by the military soon after its founding, reemerged with a vengeance. Other means of asserting white control were developed. The most effective of these were clearly in evidence when it came to the voting booth.

A range of tactics to limit African American voting power quickly emerged during Redemption: gerrymandering (the reconfiguration of districts to negate the effect of black votes), poll taxes (which required proof of payment on land taxes—something you could not supply if you did not own land), grandfather clauses (which limited voting to those men whose grandfathers had voted, thereby excluding African Americans), and literacy tests (which involved onerous requirements like reciting part of the state constitution from memory).

If those limiting maneuvers weren’t enough, white actors deployed other tactics to cut off access to the vote. In some southern areas it became clear that just registering to vote could be a matter of life or death. Those African American men who managed to register still had to navigate the challenge of actually voting. It was not uncommon for black voters to find someone standing outside the voting booth with a whip, threatening those who voted Republican. The people doing this dirty work were often members of local militias like the Klan. Finally, if all the aforementioned methods of voter suppression failed, there was always the ultimate form of racial harassment: lynching.

Lynching was rare prior to the Civil War because to lynch an enslaved person was to destroy somebody’s property. During Reconstruction, federal military presence mitigated this violence, but once that presence was gone, lynching became a way that the South redeemed itself. Between 1882 and 1901, more than one hundred lynchings per year were recorded nationally, the great majority of them in the South. Between 1882 and 1968, more than five thousand people died in lynchings; at least three-quarters were African American. These statistics represent only recorded lynchings, and actual numbers continue to be revised higher as historians uncover new records of this type of violence.2

Lynchings ranged in scope and method. Most happened under the cover of night and were perpetrated by small groups determined to exact justice on their terms. Some were public and well-documented grotesqueries that were advertised in the local paper. Professional photographers frequently documented the horror, only to amplify it when they sold the reproductions as prints and postcards.3

It was not unusual for victims to be physically assaulted and mutilated while still conscious before being hanged or tied to a post to be burned alive. Even after the lynching, the abuse to the body might not end. Scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois recounted being in Atlanta in 1899 after Sam Hose was lynched. Du Bois was headed to the editorial offices of the Atlanta Constitution to talk about this lynching when he learned that parts of Hose’s body had been cut off and were for sale as souvenirs in a nearby store. The inhumanity of the moment never left Du Bois’s consciousness.4

Like Sam Hose, the majority of lynch victims were African American men accused of rape. The presumption was that a black man who raped a white woman had also violated the sanctity of the South. Typically, language around lynching framed it as a manly act: black brutes were uncivilized rapists, and lynch mobs were protectors of white women and civilization. As historian Gail Bederman has shown, deploying the concept of being civilized was a strategic choice in this era. As the United States was rapidly industrializing, being “civilized” became a way to exercise control in a landscape of changing cultural values. Being civilized, or declaring another group uncivilized, was a way of marking one’s place in the world.5

Ida B. Wells, a black female journalist and civil rights pioneer, tapped into this logic but turned it against itself. Based in Memphis, Tennessee, Wells became an anti-lynching activist after a friend, Thomas Moss, was murdered for opening a store that competed with a nearby white-owned business. Outraged by the injustice, Wells organized boycotts and wrote editorials that excoriated this unabashed racial violence. When she argued that lynching was a manifestation of uncivilized white male behavior, Wells shocked her audiences by turning widespread ideas about race and civilization upside down. Wells further upset common beliefs when her investigations of lynching across the country revealed that in many cases lynch victims were not even accused of rape, but rather theft, rudeness, or assault. Thomas Moss was lynched merely for introducing economic competition into a community. Wells’s editorials and speeches had personal consequences. After she wrote that some white women resorted to claims of rape to cover up their desire for African American men, Wells had to flee Memphis. She would never return.6

Against this backdrop of violence and ideology, other African American reformers were hard at work, determined to improve the life chances of poor blacks. Much of this work flowed through churches, societies, and associations whose members envisioned and fought for communal, long-term gains. These reformers saw it as their duty to uplift the race.

The notion of “uplift” was simultaneously subversive and conservative. At its core, it was an ideology committed to improving the quality of African American life that also aligned with the restrictive gender and class conventions of its era. Its roots can be traced to the American Baptist Home Mission Society, a northern, white-run effort to educate southern African Americans. Its leaders included Henry Morehouse, a white man who coined the phrase “talented tenth” to suggest that 10 percent of black America would uplift the race as a whole.7

The politics of such organizations were fraught. Black religious activity during this era was in flux, as organized religious bodies clashed with grassroots worship. Some African Americans were suspicious of groups like the Home Mission Society, whose white northern members aimed to civilize African Americans through Christian ethics. In 1895, a group of southern blacks, frustrated by the American Baptist Home Mission Society’s edicts, formed their own society, the National Baptist Convention. Created by and for black people, the convention rejected white society’s patronizing attitudes and aimed to establish African American control over black churches, religious practices, and secular activities.

Aligned with this push to uplift the race were various secular black organizations. In 1896, one of the more prominent of these organizations emerged: the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). The NACW’s motto was “Lifting while we climb.” Its members were middle- and upper-class black women who organized campaigns and protests in support of various causes. For example, in an era when cities were hotbeds of disease, NACW members taught proper hygiene to poor black urban residents and waged anti-tuberculosis campaigns. The NACW also engaged in explicit acts of political resistance, like picketing and lobbying in support of anti-lynching legislation. Although its goals were progressive, the organization also had a conservative outlook in that its members considered it their duty to teach lower-class African Americans how to behave respectably. For the women of the NAWC, uplift was a manifestation of the Victorian sense of white middle-class propriety they had grown up with, and they felt they had a special duty to save the race.

Anna Julia Cooper, an educator and the leading black feminist theorist of her day, exemplified the uplift ideology espoused by the NACW. After a successful career as an educator at M Street High School in Washington, DC, the nation’s best black public high school, Cooper pursued graduate studies at the Sorbonne, receiving her doctorate when she was sixty-three. Upon returning to the United States, she established Frelinghuysen University, an institution that provided evening classes for black workers who wanted to improve their employment prospects.

In 1892, while teaching at M Street, Cooper published A Voice from the South. In a key passage, she wrote, “Only the black woman can say where and when I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.”8 African American women, Cooper declared, could say how, when, and where blacks would join society as rightful members. This was the epitome of uplift ideology with all of its best and complicated social biases.

Uplift ideology was not limited to the women’s sphere. Leading black male activists with starkly different political strategies for securing African American freedom argued over the best way to save the race. The most enduring of these debates revolved around accommodation and assimilation, typically represented by Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, respectively.

Born enslaved in 1856, Washington worked in the West Virginia coalfields before and after emancipation. His college training at Hampton Institute focused on vocational education and technical expertise rather than high culture or the liberal arts. This pedagogy made a deep impression on Washington. In 1881, he established the Tuskegee Institute. Located in the town of Tuskegee, Alabama, in the heart of white farming country, the institute succeeded due to Washington’s skill at building coalitions that ostensibly crossed racial lines and class boundaries while also respecting both. Although Tuskegee was not a racial oasis or a site of full social integration, the school eventually became the town’s lifeblood and economic engine. As such, it became a manifestation of Washington’s long-term strategy: through slow, hard work, African Americans would become so economically vital that whites could not help but incorporate them into society.

Washington’s go-slow approach, combined with his ability to interact with white business leaders, made him the darling of philanthropists. These individuals were attracted to Washington’s work largely out of self-interest: they believed that Washington was training a smart, technically adept workforce of docile, second-class citizens. Northern business interests, in particular, donated substantial amounts of money to him.

In 1895, Washington’s ascent accelerated with his address to the Atlanta Cotton Exposition. In that speech he called on white employers to recognize blacks’ native loyalty, but he also exhorted blacks to be patient in their desire for progress. Washington said, “To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the southern white man, who is their next-door neighbor, I would say: ‘Cast down your bucket where you are’—cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded.” He continued, “The wisest among our race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly.” Elaborating, he noted, “In all things that are purely social, we can be as separate as the fingers; yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”9

Between 1895 and his death in 1915, Washington became the most powerful African American in the country, in part because his approach to race management aligned with the emerging legal consensus about the mixing of the races. After the Civil War, state legislatures began to issue laws designed to separate the races. By the mid-1870s, these “Jim Crow” laws regulated public accommodation and transportation. The newly entrenched system pervaded virtually every facet of daily life.

In 1896, the Supreme Court issued the landmark decision Plessy v. Ferguson. The case involved a Louisiana man, Homer Plessy, who bought a rail ticket in 1892. After Plessy took a seat in the whites-only first-class coach and refused to move, he was jailed for breaking a Jim Crow statute. Plessy’s action was intentional: he wanted to challenge segregation laws and assumed he would be successful. Plessy argued that segregation violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution. The Supreme Court disagreed. In an 8–1 decision, the Court held: “We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction on it.”10 In a dissent, Justice John Harlan wrote that “the arbitrary separation of the citizens on the basis of race, while they are on a public highway, is a badge of servitude, wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution.”11 While Harlan’s dissent would eventually become a guiding legal principle, his was a lonely voice on the Court. Plessy remained the law of the land for nearly sixty years.

It is easy to condemn Washington from the convenience of the present, but it is worth considering what was possible for an African American leader in the Deep South. Washington worked in an environment where lynching was omnipresent and the black vote had virtually disappeared. Fully 75 percent of African Americans lived in the former Confederate South. Approximately 50 percent of the southern population was black, but blacks owned just over 10 percent of the farms. Outside of institutes like Tuskegee, there were few schools that offered an agricultural education, and farm production was low. In effect, the southern black population was politically, socially, and economically aggrieved and lived in a state of racial terror. In this context, pursuing economic independence prior to fighting for rights was not an unreasonable strategy.

Yet it was not the only option. Du Bois offered an alternative. (Anna Julia Cooper anticipated many of Du Bois’s ideas in A Voice from the South, but her contributions on this topic have often been obscured.)12 In a memorable critique of Washington, Du Bois wrote, “Manly self-respect is worth more than lands and houses, and a people who voluntarily surrender such respect, or cease striving for it, are not worth civilizing.”13 He rejected Washington’s call to relinquish political power, instead insisting on civil rights and advocating for the education of the talented tenth.

This agenda reflected Du Bois’s experience. Born in 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, he attended Fisk University, studied in Berlin, and received a PhD from Harvard. Du Bois created the field of urban sociology with his 1898 book The Philadelphia Negro and taught at Atlanta University, where he edited a long series of studies of social problems, doing what he could to connect theory, practice, and social reform.

In his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois offered a stinging critique of Washington’s accommodationism. In a chapter titled “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others,” Du Bois argued that the “thinking classes of American Negroes” carried a special burden. They had “a responsibility to themselves, a responsibility to the struggling masses, a responsibility to the darker races of men whose future depends so largely on this American experiment, but especially a responsibility to this nation.” He argued that Washington’s ideology led to “industrial slavery and civic death.”14

Washington’s and Du Bois’s ideologies came into direct conflict in 1905 when Du Bois and other black professionals, including Ida B. Wells, met at Niagara Falls to form an organization dedicated to full citizenship rights for black Americans. Known as the Niagara Movement, the group demanded freedom of speech, full citizenship, male suffrage, the abolition of racial distinctions, and respect for working people. Washington was invited to join but declined to participate, unwilling to risk alienating his white support base.

In 1909, members of the Niagara Movement were asked to attend a national conference on race relations and civil rights. The event was led by white activists, many from abolitionist families, in response to a 1908 race riot and lynching in Springfield, Illinois. The riot began when a white woman accused an African American worker of assaulting and raping her. She later recanted, but it was too late. Mobs attacked African Americans suspected of harboring the accused rapist. The riot occurred on the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, and black citizens were lynched near Lincoln’s home and gravesite. That the Great Emancipator’s memory could be so sullied horrified these white liberals. With a few Niagara Movement representatives, they formed a new organization dedicated to African American civil rights, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Du Bois became the NAACP’s director of research and publicity and editor of its magazine, the Crisis. At its founding and for many years after, he was the sole African American officer. The NAACP focused primarily on legal and intellectual work, and its leaders prioritized assimilation. African Americans, they believed, eventually would integrate into white society—and not vice versa. Other organizations also worked to improve black life via different strategies. Most prominent was the National Urban League, founded in 1911, which focused on finding jobs for African American migrants. The Urban League’s work, in particular, came at a critical time.

At the turn of the twentieth century, black America was overwhelmingly a rural, southern population. That changed as massive numbers of African Americans moved north in the so-called Great Migration, at the time the greatest internal migration in US history. The Great Migration has to be understood as both a demographic shift and a political movement. African Americans with the resources to migrate did so because the political gains of Reconstruction had been systematically stripped away. Their ability to vote had disappeared, state-funded education had become functionally nonexistent, social segregation was increasing, the threat of lynching loomed, and the sharecropping system forced farmers into second-class citizenship and dead-end employment that looked too much like slavery.

Various factors amplified the scale of the Great Migration. Chief among them was the abundance of jobs in the North. Labor agents, employed by the owners of mines, factories, and mills, abetted this process. They traveled south and spoke glowingly of northern life to rural black workers, even offering to pay their train fare north. The Chicago Defender, the era’s most important African American newspaper, also played an important role in the relocation. The Defender circulated broadly throughout the South and encouraged migration by featuring letters to the editor relaying opportunities available in the North and regularly detailing the horrors of southern lynchings.15

In the North, black migrants found a mixed quality of life. Housing was de facto segregated, often poorly maintained, and located in high-crime neighborhoods rife with public health hazards. Migrants frequently encountered hostility from northern blacks who had been there for generations and held the new arrivals in disregard for their dress, customs, and dialect. The new arrivals’ treatment suffered further because their presence increased the competition for jobs. Even as the Urban League devoted significant resources to helping African American migrants, some of the organization’s tactics provided short-term gains that damaged long-term relationships. For example, the Urban League would collaborate with factory owners when their unionized white workers went on strike, securing African Americans as scab laborers, who in turn were vilified by striking workers.

As the Great Migration destabilized southern society, white resistance became increasingly palpable. Its most obvious manifestation was the KKK. Destroyed at the national level during Reconstruction, the Klan crept back during Redemption, and its popularity skyrocketed around 1915, just as the Great Migration reached its peak. This was not a coincidence.

Much of the Klan’s resurgent popularity can be attributed to D. W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation (1915). Based on Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman, the film depicted Reconstruction from an explicitly racist point of view. In its climactic scenes, a newly freed man (a white actor in blackface makeup) stalks a white woman, who avoids being raped only by leaping off a cliff. She dies in her brother’s arms, and he retaliates by lynching her assailant and organizing the Klan in an attempt to maintain social control, protect white womanhood, and redeem the South.

The Birth of a Nation was a runaway hit. It played to sold-out audiences around the country, earning over $10 million in its first release. It also earned the ire of the NAACP, which issued a forty-seven-page pamphlet titled “Fighting a Vicious Film: Protest against ‘The Birth of the Nation,’ ” held rallies at theaters, and famously referred to it as “three miles of filth.”16 Griffith’s film opened conversations about the promise of the American ideal, inviting its supporters to lament their forced sacrifices in the age of dawning black freedom. To its detractors, the movie was further evidence of a long-broken promise.

In 1918, with The Birth of a Nation still in the public’s mind and sixteen months after the United States entered World War I, Du Bois wrote an editorial for the Crisis called “Close Ranks,” in which he called for African Americans to have faith in the nation’s democratic promise: “Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy.” Du Bois argued that by enlisting, African Americans would earn respect that would translate into civil rights after the war. In an era of continuing racial violence, “Close Ranks” angered many black leaders because it admonished blacks to forget their “special grievances.”17

Those grievances took different forms in the North and Midwest than in the South. African American migrants often burdened social service agencies, destabilized the housing market, and exacerbated labor tensions, forming a powder keg that could explode into violence. The East St. Louis riots offer a stark example. On July 2, 1917, striking white workers in local aluminum factories were furious when they were replaced by black scab workers. They started fights that turned into citywide violence. The police looked the other way as dozens of African American citizens were murdered and thousands of black families were left homeless. In response, the NAACP organized a silent march down New York City’s Fifth Avenue. Led by muffled drums, ten thousand men, women, and children marched from Harlem to the heart of Manhattan in dead silence, carrying banners that read, “Mr. President, why not make America safe for democracy?” and “Mother, do lynchers go to heaven?”18 Two years later the marchers received mixed messages in response.

The summer of 1919 is known as the Red Summer, a name evoking the blood that was shed in race riots in twenty-five midwestern and northern cities. The worst riots took place in Chicago in July when Eugene Williams, a young African American boy floating in Lake Michigan, strayed over an unmarked line at a segregated beach. Williams was stoned from the shore and drowned. As news of the murder swept across Chicago, white ethnic street gangs—already angered by housing tensions that had emerged as African American migrants moved into previously white neighborhoods—roved about with the stated purpose of defending their turf. In the ensuing five-day riot, roughly forty people (most African American) were killed, and five thousand were injured. Much as in East St. Louis, police stood by and let white mobs attack. Peace returned only when the Illinois National Guard arrived. Unlike their counterparts in East St. Louis, black Chicagoans responded with militancy, forcefully defending their neighborhoods.

That change in attitude can be understood in a broader sociopolitical context. Around three hundred thousand African Americans fought in World War I. After serving admirably in Europe—and being treated like heroes by locals in England and France—the soldiers returned home expecting justice and full citizenship. Briefly, progress seemed possible. When the 369th Infantry Regiment, known as the Hellfighters, returned in 1919, one million people watched them parade from Lower Manhattan to Harlem. Marching in the opposite direction as had the participants in the NAACP’s silent protest, they received a hero’s welcome.

Yet early optimism proved premature. After several years of decline, lynchings skyrocketed in 1919. Of the eighty-plus lynchings recorded that year, at least ten targeted returning soldiers, most murdered while in uniform. This was social control at its most grotesque. Du Bois realized his grave error in the previous year’s editorial, and in a new column, “Returning Soldiers,” he wrote: “This country of ours, despite all its better souls have done and dreamed, is yet a shameful land. It lynches. It disfranchises its own citizens. It encourages ignorance. It steals from us. It insults us. This is the country to which we, soldiers of democracy, return. . . . We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting.”19

The editorial captured a pervasive mentality among African Americans. Black urban residents were fed up with the racial violence that plagued cities. Across the United States, African Americans still suffered terrible discrimination and had difficulty securing jobs or decent housing. The shocking news of African American soldiers lynched in uniform, coupled with the anger recently voiced by leaders like Du Bois, conveyed the sense that a new political climate had emerged, one in which blacks would insist on having their civil rights—or else.

Although state governments, particularly southern ones, had a well-established history of placing barriers before their black subjects, African Americans’ growing insistence on securing full citizenship did not go unnoticed by the federal government. After World War I, federal surveillance of African Americans grew sharply. The riots of 1917 and 1919 unsettled white politicians, including a young J. Edgar Hoover. In 1919, Hoover became head of the Department of Justice’s new General Intelligence Division. He investigated “liberal activity,” an intentionally vague construct that Hoover leaned on to rationalize infiltrating African American groups across the political spectrum.

Under Hoover’s leadership, a prime early target of surveillance was Marcus Garvey. Born in Jamaica in 1887, Garvey was educated in London. Upon returning to Jamaica in 1914, he organized the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Inspired by Booker T. Washington’s notion of economic self-sufficiency, Garvey aspired to emancipate blacks across the globe through economic empowerment and empire formation. As he wrote in his Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World (1920), “We believe in the freedom of Africa for the Negro people of the world, and by the principle of Europe for the Europeans and Asia for the Asiatics, we also demand Africa for the Africans at home and abroad.”20

In 1916, Garvey moved to Harlem. He published a popular journal, Negro World, which served as the mouthpiece for his nationalist philosophy of racial pride and unity. Garvey’s reputation blossomed, and he soon claimed to have six million followers. There is little doubt that his popularity was connected to his vision: “We have outgrown slavery, but our minds are still enslaved to the thinking of the master race. Now take those kinks out of your mind instead of out of your hair. . . . We have a beautiful history and we shall create another one in the future.”21 When African Americans realized their potential, Garvey believed, they would rise up and anoint him as their leader. In preparation for that moment, Garvey organized parades in which uniformed UNIA members marched in front of him while, in his convertible, Garvey presented himself as a benevolent emperor, bedecked with epaulets, gold buttons, trim, and plumage.22

Garvey’s plans ranged from the realistic to the absurd. If the UNIA laundries, groceries, and other retail operations were the most practical expression of his ideology, the Black Star Steamship Line, launched in 1919, was the most fantastical. Given the enormity of Garvey’s ambitions, the Black Star became the crown jewel of his efforts: a steamship line that would demonstrate black self-sufficiency and nation-building potential. Garvey began selling bonds to raise money for ships that would exemplify black power as they employed all-black crews, took African Americans to Africa, and became a linchpin of the global economy. Initially promising, the project quickly became Garvey’s undoing. While the few ships he was able to secure became powerful symbols of possibility, the enterprise became a business and legal fiasco.

Garvey’s mass popularity, appeals for race pride, and haughty imperialist style worried people like Hoover. In 1923, Hoover indicted Garvey on mail fraud charges related to the Black Star Line, and in 1925 the head of the UNIA was sentenced to five years in prison. Before Garvey’s term could be completed, he was pardoned by President Coolidge on the condition that he return to Jamaica and never return. Garvey accepted the stipulation and was deported in 1927.

The year Garvey was sentenced to prison, Howard University philosopher Alain Locke edited a special issue of the journal Survey Graphic. That journal captured the spirit of a new cultural mentality that was being expressed by African Americans throughout the country. The special edition included poetry, essays, excerpts from plays, and short stories. Locke added material to the edition to produce a book, The New Negro, published in 1926. That book became the bible for this new artistic moment, typically referred to as the Harlem, or New Negro, Renaissance.

Most historians point to African American soldiers’ return in 1919 as the movement’s beginning. There is no consensus about when the movement ended. What there is little debate about, however, is the importance of the New Negro Renaissance as a barometer of a shifted African American cultural sensibility that grew directly out of the dislocations associated with the Great Migration as well as the heightened racial awareness and political impatience that arose after World War I.

While mostly articulated as a moment of cultural discovery, Locke saw the Renaissance as a political movement shrouded in the cloth of culture. Further, he understood culture itself as a political battleground. He believed the Renaissance was a fight for cultural recognition that, once gained, would prove that African Americans deserved freedom and equality. In his introduction to The New Negro, Locke wrote, “For the younger generation is vibrant with a new psychology; the new spirit is awake in the masses, and under the very eyes of the professional observers is transforming what has been a perennial problem into the progressive phases of contemporary Negro life.”23

Although Locke saw culture as a means toward a political end, he also had an expansive view of culture. Unlike the talented tenth leaders who preceded him, Locke found much to praise in the folk culture that was most often connected to the black experience. He was not alone in this: Renaissance artists like poet Sterling A. Brown (Southern Road) and cultural anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston (Mules and Men and Their Eyes Were Watching God) hailed folk heritage, viewing it as the authentic depiction of a rich and complex black life. Editor and novelist Jessie Fauset (There Is Confusion and Plum Bun) also sought to portray black life in all of its honesty. Unlike Brown’s and Hurston’s orientation, however, Fauset focused on upper-class African Americans, even when doing so raised other, painful issues like intraracial class politics and racial passing.24

Celebrations of an authentic, rural folk culture or examinations of the complexities of highbrow black life did not represent the boundaries of African American art in the Renaissance. Experimental, genre-busting literature like Jean Toomer’s Cane sat alongside the militancy of Jamaican poet Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die,” which in turn shared a stage with the work of blues artists like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. Painter Aaron Douglas married African and modernist aesthetics in his work, while sculptor Augusta Savage challenged collectors’ and patrons’ pursuit of the fetishized native in art.25

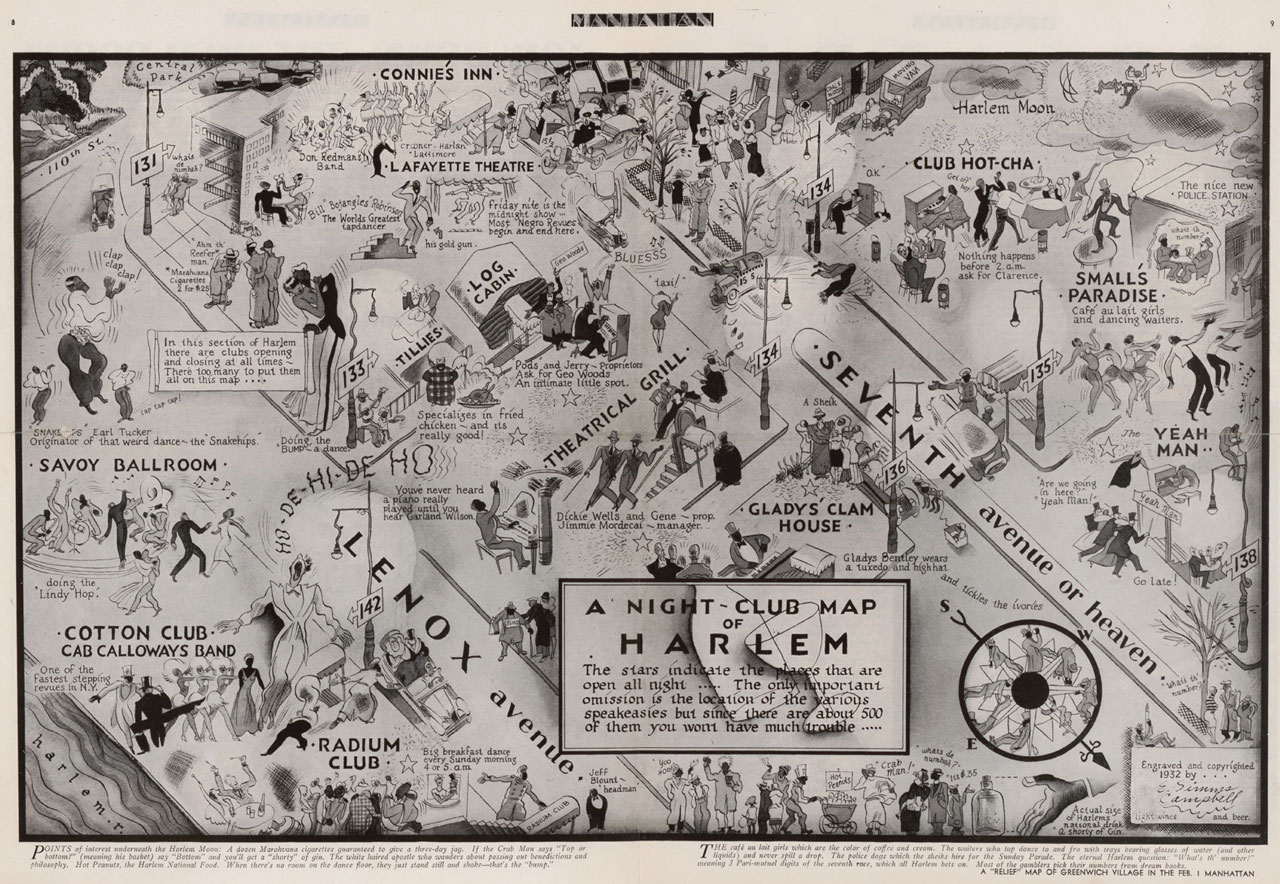

In this regard, Savage was aligned with critics who were troubled by what scholars now call the “white gaze.” The term could refer literally to white audiences at segregated Harlem nightclubs who watched African American performers and participated as onlookers of the social scene or those in Paris, where dancer Josephine Baker mesmerized fans with her notorious and titillating “Banana Dance.” Whether in Harlem or Paris or elsewhere, the white gaze also refers to white fascination with black culture. Prominent patrons like the art collector Albert Barnes praised the “authentic and native talent” of a “primitive race.” As condescending as Barnes’s language sounds, it was meant admiringly: he believed that because blacks were culturally less developed than whites, they were in touch with something mysteriously primal and authentic.

New Negro writer Langston Hughes had a different interpretation of black cultural talent. In his iconic poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” Hughes placed himself (and, by extension, black people across time and space) next to the rivers that cradled civilizations across time: he bathed in the Euphrates, built his home near the Congo, labored by the Nile, and watched the sun set over the Mississippi. “I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins,” he wrote.26

White Americans declared during Redemption and beyond that African Americans deserved nothing more than second-class status because they were so far removed from the blessings of civilization. Hughes and his fellow New Negro artists and intellectuals felt otherwise and were certain that they were perfectly situated to build a brilliant future on the foundation of a remarkable past. This conviction rings clearly in the closing lines of Hughes’s 1926 essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”: “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. . . . We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.”27