The encodings described above can be fairly effective at disguising the underlying hostname of a web site, but they don’t look like regular URLs and that alone can attract suspicion. A far more convincing URL is something like:

| http://www.oreilly.com@www.craic.com/ |

Even better, combine it with some hexadecimal encoding: http://www.oreilly.com@%77%77%77%2e%63%72%61%69%63%2e%63%6f%6d

The casual user would take this to be a link to http://oreilly.com, but instead it takes you to http://craic.com. The at sign character (@) is the giveaway. As mentioned above, this

separates the hostname and path section to the right from the

username:password section to the left. Here, instead of a valid username

and password, we have the string http://www.oreilly.com. The http://craic.com web server doesn’t use authentication to

restrict access, so this string is simply ignored. As far as the server

is concerned, you can put whatever you want in that section.

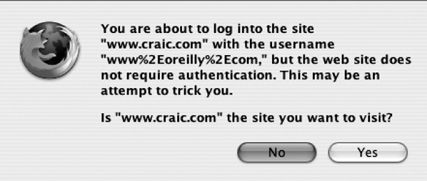

This is such a widespread trick that several browsers now try to catch it before sending the request to the web server. They either report an error or alert the user and ask them if they want to continue. It works in Safari on Mac OS X but generates a “Page cannot be displayed” error in Internet Explorer 6 on Windows. Firefox on Mac OS X warns you that the site does not require authentication and asks you if you want to continue (see Figure 4-1).

An additional twist that is sometimes used with a fake username is

to pad out the part between it and the real hostname with blank

characters. The idea is that when you mouse over the link in your email

client and the target URL appears in the status bar, the padding will

have pushed the hostname far enough to the right that it will no longer

be visible. The casual user will just see the fake hostname. Regular

whitespace characters won’t work in this situation so they typically use

a non-printing ASCII character in hexadecimal format. The Start of Heading (SOH) character is often

used, written in hex as %01, but the

space character (%20) works just as

well and looks more convincing. Here is a real example with 140 padding

characters:

http://www.e-gold.com

%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01

%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01

%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01

%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01

%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01

%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01

%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01%01

@reynsan.netfirms.com/Padding URLs is quite a common form of obfuscation, and it can take various forms, as shown in this example:

http://211.10.155.13/.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../

.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../

.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../

.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../.../../

.../../.../../.../../.../error.htmlThis odd-looking creation uses a directory called ..., with three periods, and then intersperses

it with .. (two periods). The string

.. has a special meaning within a URL

or Unix directory path. It tells the function that is parsing the URL to

step back up one level. In other words, the partial path /.../../ means go down one level into

directory ... and then step back out

of it. It has no effect. So this very long URL ends up being converted

to the much simpler form of http://211.10.155.13/.../error.html.

A similar trick is used in the filenames of email attachments. Viruses are usually distributed as attachments with a .pif file extension. Simply seeing that suffix is a warning sign to many users, so filenames are padded with regular space characters so as to move it off to the right. Here is just one of many examples that looks like a simple text file at first glance.

list_ed_jones.txt .pif