FIG. 5.1. Southeastern Frontier of the Habsburg Empire. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

Harvest of Briars

TURKS, RUSSIANS, AND THE SOUTHEASTERN FRONTIER

I do not find that Your Majesty would be well-served by the possession of these faraway places.

—PRINCE EUGENE OF SAVOY

Russia is almost useless as a friend, but could cause us considerable damage as an enemy.

—WENZEL ANTON VON KAUNITZ

ON ITS SOUTHERN and eastern frontiers, the Habsburg Monarchy contended with two large land empires: a decaying Ottoman Empire, and a rising Russia determined to extend its influence on the Black Sea littorals and Balkan Peninsula. In balancing these forces, Austria faced two interrelated dangers: the possibility of Russia filling Ottoman power vacuums that Austria itself could not fill, and the potential for crises here, if improperly managed, to fetter Austria’s options for handling graver threats in the west. In dealing with these challenges, Austria deployed a range of tools over the course of the eighteenth century. In the first phase (1690s–1730s), it deployed mobile field armies to alleviate Turkish pressure on the Habsburg heartland before the arrival of significant Russian influence. In the second phase (1740s–70s), Austria used appeasement and militarized borders to ensure quiet in the south while focusing on the life-or-death struggles with Frederick the Great. In the third phase (1770s–90s), it used alliances of restraint to check and keep pace with Russian expansion, and recruit its help in comanaging problems to the north. Together, these techniques provided for a slow but largely effective recessional, in which the House of Austria used cost-effective methods to manage Turkish decline and avoid collisions that would have complicated its more important western struggles.

Eastern Dilemmas

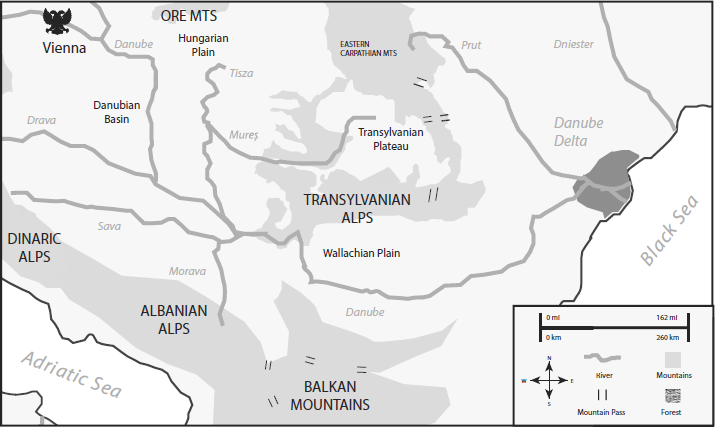

The end of the Great Turkish War in 1699 brought the Habsburg Monarchy into possession of a vast span of territories to the south and east of its historic heartland in Upper and Lower Austria. Under the terms of the Treaty of Karlowitz, the monarchy gained nearly sixty thousand square miles of land, effectively doubling the size of the empire. The new territories stretched to the Sava River in the south and the Carpathians in the east, bringing Slavonia, Croatia, and most of Hungary, including Transylvania but without the Banat, under Habsburg rule (see figure 5.1).1

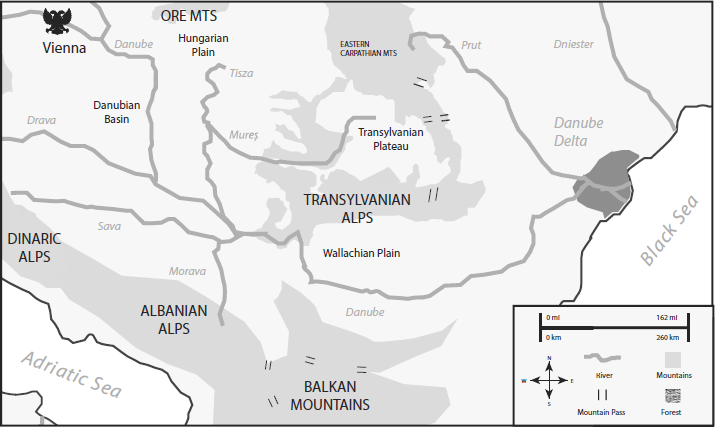

Acquisition of these new lands greatly alleviated the ancient security problem in the south, where since the sixteenth century an expansionist Ottoman Empire had placed unrelenting pressure on the Habsburg core, rendering Royal Hungary and Styria as buffer territories. With the Ottoman frontier so far north, Turkish armies had been able to maraud the borderlands and invade the Erblände itself with little warning. Twice in previous centuries—once in 1529 and again in 1683—large Ottoman siege trains had moved through the gap in the Šar Mountains up the Maritsa, Morava, and Sava River valleys to invest Vienna itself (see figure 5.2).2 Only with great effort and the help of allied armies from across Europe had these attacks been repelled. By placing a generous layer of territory under Habsburg control, Karlowitz effectively removed this problem of surprise invasions while furnishing the monarchy with the nominal size and strategic depth of a first-rank power. Expansion in the southeast, however, created two sets of problems for the Habsburg state—one administrative in nature, and the other geopolitical.

FIG. 5.1. Southeastern Frontier of the Habsburg Empire. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

FIG. 5.2. Ottoman Invasions of the Habsburg Heartland. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

The Eastern Power Gradient

First, Austria faced the question in the Balkans, encountered by most land empires at their height, of where to draw the line of conquest. As noted in chapter 2, the power of an empire can be assessed according to the surface area over which it can exercise control and collect taxes. The frontier historian Lattimore Owen has surmised that historically, land empires eventually hit an “outer limit of desirable expansion,” at which the ability to bring new territories under civil administration is undercut by the costs of projecting military power. Beyond this point, the power gradient, or rate at which military power is eroded by distance, becomes too steep, and the empire faces a “zone of diminishing returns,” where additional gains, rather than strengthening the empire, weaken it. Not expanding to this point deprives an empire of resources and safety, as was the case for Austria in the period before Karlowitz. But going beyond it leads to overstretch and increases the state’s vulnerability. The ability to accurately identify the point of maximal expansion is therefore an important objective for successful empires. Only by doing so can they establish the parameters of an orbis terrarium—what the Chinese called t’ien hsia—that can be sustainably administered through the construction of a defensive perimeter.3

Finding the point of maximal expansion is easier when geographic features demarcate the space in question, and herein lay much of the problem for Austria in the southeast. The Balkans were the only Habsburg frontier to possess relatively weak natural borders. Major mountain ranges lie several hundred miles south of the rivers Sava and Drava, which allowed substantial fluctuation of formal borders according to military realities. To the east, the map would seem to indicate the possibility for expansion to the Black Sea, but the interposition of the Carpathians some 270 miles before the river delta and malarial flood zones on the Wallachian Plain placed obstacles to such enlargement.

The nature of the terrain in the southeast also worsened the effects of the power gradient. At almost 800 miles in length, this was the monarchy’s largest frontier. Unless properly managed, it could easily require large forces to hold down far-flung sectors often separated by rugged terrain with few roads. Units deployed to the south were harder to reposition than in other frontiers. The travel distances from the Balkans to the monarchy’s other frontiers was further and more complicated than movement between the other three. Once deployed, troops were more likely to get bogged down: in the Serbian sector, by seasonal rains, and in Wallachia, by floodplains and fever. The longer a war lasted here, the more troops it was likely to suck in, thereby embroiling the monarchy in protracted fighting. These factors impacted military range, not only by making the radius of effective operations shorter than in more congenial territories of western Europe, but also by creating logistical incentives for Habsburg commanders to tether forces here to predictable supply depots and avenues of retreat.

A further complication was the human makeup of the southeastern territories. The territories that Austria acquired at Karlowitz possessed social, political, and economic traits very different from the rest of the monarchy. Such formal economy as existed bore the stamp of a century and a half of Ottoman rule—artisanal and agricultural, kept local by the underdeveloped infrastructure, and not easily incorporated into the western Habsburg lands.4 As in neighboring frontier spaces under Ottoman and Russian rule, social organization in Hungary was archaic and rustically agrarian, with only five towns with populations greater than twenty thousand.5 Further south, frontier cultures of tribalism and raiding did not readily lend themselves to assimilation by bureaucratic empire. In the eyes of much of the Orthodox population, the Habsburg soldiers and administrators who arrived after Karlowitz brought a liberating but new and alien form of rule; to the Magyar nobility, they had the appearance of foreign interlopers.

In both territorial and human terms, Austrian expansion in the southeast, while necessary for keeping neighboring empires at bay, tended to not significantly add to the monarchy’s economic resource base. Indeed, expansion here brought problems. On the border itself, the long-standing Ghazi tradition of incessant raiding brought low-intensity attacks on a more or less permanent basis, creating a “constant state of emergency” that made “official boundary marks worthless.”6 The presence of a large and churlish Magyar nobility in the historically secessionist territory of Transylvania near the Ottoman border created a continual danger of revolt. These factors amplified the geopolitical “pull” on the monarchy’s southeastern flank, requiring frequent military intervention and ensuring that the army’s attention here would be directed inward as much as outward.

Together, this mixture of large distances, internal difficulties, and low returns on investment made the south a nettlesome place for the exercise of Habsburg power. Despite their formal incorporation into the monarchy from the early eighteenth century onward, it is more accurate to think of these lands as a kind of internalized buffer zone, militarily valuable as a shock absorber but not a net contribution to Habsburg power in anything other than status terms. As Prince Eugene mused to the emperor in the midst of one of his Balkan campaigns, “I do not believe that Your Majesty would be well served by these wretched, distant places, many of which, without lines of communication to the others or revenue, are expensive to maintain and more trouble than they are worth. Potential liabilities, Your Majesty, need not insist on their retention.”7

Balancing Turks and Russians

A second problem for Austria in the southeast was geopolitical in nature: the need to manage relations with two large, neighboring empires, the Ottoman Empire and Russia. Each posed a distinct challenge to the Habsburgs.

In spite of their recent defeat, the Turks remained a potent military force committed to projecting power in, if not pursuing outright mastery of, their northern frontiers. With a heartland in Anatolia, and outlying provinces in Persia, the Balkans, and Northern Africa, the Ottoman Empire enjoyed a significant degree of insulation in the era before modern air and naval power. While they would eventually lag behind the West technologically, the Ottomans at this stage still possessed military capabilities roughly equivalent to their Habsburg and Russian neighbors, with large stores of gunpowder, small arms, and field and siege artillery.8 The decentralized Ottoman military system, or seyfiye, consisted of local forces supplied by fiefdoms backed by a professional army centered on the famous Janissary corps. Rich in cavalry, their armies employed a combination of conventional and irregular battle techniques reflecting their partly Asiatic composition. Through centuries of Balkan warfare they had amassed numerous fortresses along the lower Danube and Black Sea. Slow to mobilize in wartime, the Ottomans suffered from inefficient administration, and were already showing signs of the political instability and court intrigue that would later paralyze the empire and trigger outside intervention. At the time of Karlowitz, however, they remained a resilient and aggressive power capable of fielding large armies and inflicting defeats on western opponents.

As the Turks began their long decline, Russia was emerging as a regional military power. The late seventeenth century saw Russia initiate the concentric expansion from the Muscovy heartland that would eventually make it one of the largest land empires in history.9 As Russian settlers and soldiers pushed east and south into the steppe, they also moved west toward the Baltic-Carpathian-Pontic line.10 At the time of Karlowitz, Russian attention was primarily focused on competition with Sweden over the Baltic and decaying Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. But the Russians looked south as well. Just three years earlier, the czar’s armies had expelled the Turks from the fortress of Azov, signaling Russia’s appearance as a serious military presence on the north shore of the Black Sea. In the years that followed, Russian czar Peter I systematically reformed the Russian state, establishing a modern fleet and professional army on the Western model. Coinciding with a period of population growth and territorial expansion, Peter’s reforms set Russia on the path to deep offensive strikes that would become the defining features of Russian military strategy well into the nineteenth century.11

The combination of Ottoman decline and Russian expansion represented both an opportunity and challenge for Austria. On the one hand, the diminishing strength of the Turks relieved much of the traditional source of security pressure that had existed here prior to 1699. It also created room for a Habsburg territorial enlargement that Russia, a fellow Christian power, could help exploit. At the same time, this process created vacuums that Russia itself might eventually be able to fill.

At the heart of this problem was the growing physical reality of Russian military strength in the region. After defeating Charles XII of Sweden and consolidating Russia’s position in the north, Peter I diverted the bulk of the army to a southerly axis. Following an unsuccessful campaign in 1710–11, Russian forces launched a series of offensive wars that expelled the Turks from their fortresses on the northern rim of the Black Sea, seized Crimea, and began pressing down the sea’s western coastline to Ottoman positions on the Danube. Already by the early eighteenth century, these exploits showed Russia’s potential to conduct large, well-organized expeditions using Western military technology well beyond its traditional periphery and eventually become an ordering presence in Austria’s backyard.

The fact of Russian strength constrained Habsburg strategic options for managing the southeast. The monarchy’s own military limitations and diminishing returns of Balkan conquest meant that Austria was unlikely to be able to fill emerging Turkish vacuums to such an extent as to bar Russia’s expansion, much less win in a sustained contest against Russia. At the same time, Austria could not simply let regional voids be filled by Russia alone. The speed of Russian conquests, if unchecked, could conceivably create a mammoth competitor bordering Austria from Poland to Serbia, thereby blocking future Austrian expansion to the mouth of the Danube. Sustained Russian proximity to the culturally and religiously similar Slavic population of Austria’s Balkan territories was likely to present a greater challenge to Habsburg authority than the common enemy of Islam.12 Should these factors lead to a diminution or ejection of Habsburg strength in the east, it could negatively affect the monarchy’s prestige and strategic depth for dealing with problems in the west.

Eastern Strategies

Habsburg rulers recognized this dilemma. A meeting of the Privy Conference in 1711 concluded that “if the tsar is victorious he could throw himself into Turkish territory as far as the Danube and possibly force his way to Constantinople, an outcome much more menacing in its long-term consequences for Austria than even the most far-reaching Turkish victory.”13 From the early eighteenth century onward, the Habsburgs would debate three broad options for how to deal with this problem: unilateral extension of Habsburg power; cooperation with Russia to eject and supplant the Turks, and comanage the remnants of their rule; and support for the status quo and resistance to Russian encroachments.14 Over the century that followed, all three alternatives would be attempted in different forms and combinations. The viability of each option at given moments in time would be a function of Austria’s power position relative to that of its two eastern neighbors, and how they judged developments on this frontier to rank alongside priorities on the monarchy’s frontiers in the west and north.

The Era of Mobile Field Armies: 1690s–1730s

In the opening decades of the eighteenth century, local conditions favored the first option: seeking to militarily shape the southeastern security environment to Austria’s advantage. At this early stage, Ottoman weakness, as demonstrated by the scale of Habsburg territorial gains in the previous war and recent Turkish defeats at the hands of the Russians, presented an opportunity to consolidate the monarchy’s enlarged position in the southeast. The prospects of gain seemed to outweigh the risks, either from the Ottoman military itself or Russian interference, which was foreseen but still on the horizon, and mainly restricted to the Sea of Azov and Dniester.

The strategy that evolved in response to this environment was shaped primarily by the desire to exploit areas of military advantage that Austria possessed as a result of the previous Turkish war along with its recent contests with Spain and France. Experiences in combat had revealed a considerable Habsburg tactical-technological edge over Turkish forces, rooted in the development of modern Austrian armies using Western equipment and fighting methods. As recently as 1697, Prince Eugene had demonstrated the decisive results that such forces could have against traditionally deployed Ottoman armies by inflicting a crushing defeat on the Turks at the Battle of Zenta that resulted in more than thirty thousand Ottoman casualties.

The early decades of the eighteenth century offered opportunities to repeat this victory. Ottoman forces of this period were equipped in similar fashion to their European rivals; indeed, Ottoman muskets and artillery were in some cases qualitatively superior to those found on the Habsburg side.15 The Habsburg edge lay in the quantity of such weapons and how they were employed tactically. The first was a by-product of advantages in the Austrian system for procuring military technology. Traditionally, the Ottoman Empire had financed its wars through plunder—a system that required continual conquest to support the growth of the military establishment. While possessing the core of a standing army, the system supporting it was unstable and contingent on victory. The development of munitions in the Ottoman Empire was tightly controlled by government, and depended on a combination of arsenals and networks of skilled artisans, the latter of which were organized by guild and dominated by the Janissary corps, an elite but conservative military body that frequently opposed innovation.16

In Austria, by contrast, procurement was tied more heavily to military contractors, who had at their disposal a larger reservoir of artisanal talent, and access to the techniques and resources not only of the Erblände but also neighboring Bohemia and Italy. To this must be added the advantage of greater resources for war in Habsburg lands, which while deficient alongside many western rivals, compared favorably with the Turks. Efforts at bureaucratic centralization, and from 1714 onward, by the monarchy’s acquisition of the Italian and Dutch lands, enabled a larger tax base and more powerful standing army. By the early 1700s, Habsburg revenue was already at least double that of the Ottoman Empire, where an astonishing 80 percent of revenues collected failed to ever reach the Treasury as a result of corruption and rent seeking.17 Of those Ottoman funds raised for defense, a large portion went to the navy, while in Austria virtually all could be concentrated on the upgrading and upkeep of the army.

One result of these financial disparities was that while the quality of Turkish weapons may have been comparable or occasionally superior, Habsburg forces tended to go to war with both more numerous and higher-quality weapons. By the time of the Turkish wars of the early eighteenth century, Habsburg units had transitioned to the flintlock musket (Flinte), which fired faster and more reliably than previous matchlock and wheel lock pieces. The newer muskets also allowed for the widespread use of bayonets, which would not be widely used in Turkish armies for many decades.18 By contrast, Ottoman armies were equipped with a mixture of European and traditional weapons. The total proportion of their armies equipped with modern firearms—the Janissaries, sipahis cavalry regiments, and artillery corps—typically made up only a third of the forces available for a campaign.19 The bulk of the army would consist of private troops raised by the local governor and volunteer forces—both of which bore arms of varied make and quality.20 Although reforms in the late eighteenth century would raise these proportions and standardize weaponry, for most of this period Habsburg forces were proportionally stronger in regular troops, with Janissaries still making up less than a third of the Ottoman Army at Peterwardein in 1716. Those Turkish units that did carry muskets were equipped with an array of different types. “Their weapons,” an Austrian military memo noted, “lack a uniform caliber, causing balls to often get stuck in the breach; as a result, their supply is slow and their fire never lively.”21

Another Austrian advantage was tactical, in how their weapons were used on the battlefield. Individually, Ottoman troops tended to be formidable fighters. As Archduke Charles wrote, “The Turk has a strongly constituted body: he is courageous and bold, and possesses a particular ability in the handling of his own arms. The horses of the Turkish cavalry are good; they possess a particular agility and rapidity.”22 Numerically, they tended to field larger armies than the Habsburgs, composed of different troop types from across the Ottoman Empire, and including everything from stock Anatolians to Persians, Egyptians, and Tatars. Their favored method of war was offensive, forming dense masses that charged headlong with Islamic banners waving and screaming, as Eugene put it, “their cursed yells of Allah! Allah! Allah!”23 Austrian eyewitnesses frequently commented on the unnerving effects that such chants, coming from tens of thousands of advancing Ottoman soldiers, could have on their opponents.24

Despite such ferocity, Turkish armies suffered from a lack of discipline, which in turn undermined tactical handling and fire control. Ottoman attacks, though large, tended to be pell-mell and poorly coordinated. As Eugene said of the chaos in Turkish formations, “The second line [is] in the intervals of the first, and others in the third line [are] in the intervals of the second, and then, also, reserves [are thrown in] and their saphis on the wings.”25 A later Austrian source characterized these assaults as proceeding “without rule or order” (ohne Regel, ohne Ordnung), comparing them to the “pigs-head” (Schweinskopf) formations described in antiquity, in which the bravest fighters inevitably push to the forefront while the mass lingered behind them.26 In a similar vein, Archduke Charles wrote that the Turks “attack in mixed groups of all types of troops, and each isolated man abandons himself to the sentiment of his force.”27

By contrast, by the early eighteenth century, Habsburg armies were drilled to fight based on the western European model, in synchronized fashion by unit. From long experience on European battlefields, the infantry was trained to deliver controlled volleys on command. The resulting discipline translated into a tactical advantage that allowed Austrian armies, if well handled, to sustain rates of fire capable of repelling or even massacring massed charges of the kind favored by the Turks. “As the effort of several Turks acts neither to the same end, nor in the same manner,” Charles noted, “they always fall against an enemy who opposes against them a unified mass acting cohesively. They rout with the same disorder and the same rapidity as they came up.”28

The question of how to maximize these advantages against the Turks was intensely studied by Habsburg military men. In Sulle Battaglie, Montecuccoli advised Austrian commanders to abandon the defensive methods used on western battlefields and adopt an aggressive, tactically offensive mind-set. “If one had to do battle with the Turk,” he wrote,

1. Pike battalions have to be extended frontally, more than has ever been the case before, so that the enemy cannot easily enclose them with his half-moon order.

2. Cavalry is intermingled with the infantry behind and opposite the intervals so that the foe … would be exposed on both sides to the salvoes of the musketry.

3. One should advance directly against the Turk with one’s line of battle, and one should not expect him to attack because, not being well-furnished with short-rage, defensive weapons, he does not readily involve himself in a melee or willingly collide with his adversary…. Using the wings of his half-moon formation, it is also easy for him to approach and retire laterally….

4. Squadrons are constituted more massively than is ordinarily the case.

5. One stations a certain number of battalions and squadrons along the flanks of the battle line in order to guarantee security.29

Prince Eugene would adopt and expand on this template in later years, systematizing fire control, introducing uniform regimental drill, placing greater emphasis on the speed of deployment for plains warfare, and adopting defensive formations to allow small units greater flexibility in movement across broken terrain.30

The overarching goal of Austrian tactics in the south was to bring their greater firepower to bear while making provisions for the safety of flanks, which Turkish cavalry were expert at attacking. To account for Ottoman speed, Austrian commanders were to form their units in square formations not unlike those later used by colonial European forces against indigenous armies in Africa. As Charles observed,

The suppleness and rapidity of their horses permit their cavalry to profit from all openings in front or in flank and penetrate there. To give them no chance of doing it, one should thus form the infantry in square … and not to put into lines anything save the cavalry which is equally rapid as their cavalry…. [Commanders should] form several squares, each one of two or three battalions strength at most. These squares constitute lines of battle as much in march as in position. One forms in the end some of these squares in checkerboard fashion, and from it one derives the great benefit of being able to mutually defend and support each other.31

So great was the risk of Turkish cavalry penetrating the flanks of these squares that Austrian units were to “camp and march always in squares,” and when possible, protect these formations with chevaux-de-frises or so-called Spanish Riders—lances several yards long fitted with boar spears—to provide a thick hedge and keep irregular cavalry at bay while reloading.32 As a further precaution, Austrian forces in the south were typically given a higher complement of cavalry (at times approaching 50 percent of field armies).

EUGENE’S OFFENSIVES

It was with these techniques that Habsburg forces took the field against the Turks in 1716. Leading them was the fifty-two-year-old Prince Eugene of Savoy. Raised among the French nobility and court of Louis XIV, Eugene had been rejected from the French Army and forced to leave Paris after a romantic controversy involving his mother and the king. Small in stature, he was a tenacious, creative, and offensive-minded general whose motto in war was “seize who can.”33 A veteran of the Turkish wars, Eugene’s first combat experience had been as a twenty-year-old volunteer pursuing the Turks alongside the Polish hussars at the siege of Vienna in 1683, for which Leopold I had awarded him a regiment of dragoons. By the time of the 1716 war, Eugene was a seasoned senior field commander who had successfully led the armies of Austria and the Holy Roman Empire in three wars and more than a dozen major battles.

The immediate cause of the war was a conflict between the Ottoman Empire and Venice, the latter of which was bound by defensive alliance to Austria. Strategically, however, the incident offered a rare opportunity to strengthen Habsburg security in the southeast at a moment when Austria’s armies were not tied up in fighting in western theaters. Eugene’s war aims, as outlined by the Privy Conference, were twofold. First, he was to secure Habsburg control of the Danube down to Vidin, thus closing the Banat salient and restricting the Turks to a second line of fortresses at Giugiu-Babadag-Ismail, and by doing so, impose a diplomatic settlement making Wallachia and Moldavia de facto buffer states. As the emperor communicated to him, it was critical to establish these provinces as client states (unser tributär erhalten).34

While tactically offensive, Eugene’s overarching strategic objective was defensive: to round off and buy breathing room for the territories acquired in the previous war. This was particularly important with regard to the final, as-yet-unconquered part of Hungary, the Banat, without which strategic communications between Habsburg possessions in Croatia and Transylvania were severed. In the ensuing campaign, Eugene inflicted crushing defeats on the Turks. Going into the war less than two years after the conclusion of the Spanish succession struggle, he was able to draw on a large reservoir of seasoned veterans from campaigns in Italy and Germany. Using the Danube as a supply artery, he bypassed Belgrade, a major Ottoman fortress holding the key to southeastern lines of communication, and instead chose to seek out and destroy the main Ottoman army. This he intercepted in late summer at Peterwardein under the personal command of the grand vizier, and despite possessing numerically inferior forces, inflicted a decisive defeat from which barely a third of the Turkish Army escaped.35 In the months that followed, he consolidated this victory by taking Ottoman fortresses at Timisoara, in the Banat, and most notably, in Belgrade.

Eugene’s military victories would not have been possible without prior Habs burg diplomacy. The key to his victories was the ability to concentrate Austria’s limited military forces, which had only occurred because Austria did not have to worry about maintaining large troop concentrations on other frontiers while fighting in the south. This was made possible by preparatory diplomacy, which had begun years before the war, when Habsburg diplomats worked to ensure that a war in this theater would not occur until the timing was militarily favorable to the monarchy.

The foundation to this diplomacy had been efforts to prevent the breakout of conflict too early—most notably, at the high point of the Spanish succession war, when Charles XII invaded Saxony with forty thousand troops, raising the threat of intervention to support Silesian Protestants or even alongside Protestant Hungarian rebels against Vienna. With the Erblände naked to attack from this quarter, Joseph I used what amounted to preemptive appeasement at Altranstädt to buy peace with Charles by recognizing Sweden’s candidate to the Polish throne, ceding German land and even making concessions to the Protestants in Silesia in exchange for avoiding Austrian entanglement in the Great Northern War.36 The following year a similar problem loomed in the south, when tensions with the Porte threatened to open a new front in the war after several Ottoman merchants were killed in a border incident at Kecskemet. Faced with the prospect of a Turkish declaration of war at a moment when Habsburg forces were pinned down on the Po and Rhine, Joseph I used a combination of bribery at the sultan’s court and compensation for Turkish damages to buy peace.37 Again in 1709, the passage of Sweden’s Charles XII into Ottoman protection following his defeat by the Russians threatened to bring the Turks into the war. This time Austria responded by rallying its western allies against the Swedes, issuing a war threat to Turkey and creating a new northern corps under Eugene to deter attack.38 In both instances, the Habsburgs were able to avoid war with the Ottomans at an inconvenient moment for their broader strategic interests.

A similar mixture of accommodation and force had been used to ensure that Eugene would not have to worry during his campaigns about problems from the Hungarians. From 1703 to 1711, Magyar kuruc raiders under the rebel prince Rákóczi had waged a relentless irregular war against Austrian positions in Hungary, momentarily even threatening the Habsburg capital.39 In order to concentrate force in the western theater, Austrian diplomats in 1706 brokered a temporary armistice that allowed Eugene to focus attention on his operations in Italy, without granting the scale of constitutional concessions sought by the rebels.40 After achieving victory in the west, the Habsburgs were able to use a “surge” of cavalry into Hungary to defeat the rebels and force a favorable peace. The resulting Treaty of Szatmar (1711) was a showpiece of Habsburg diplomacy, mixing threats (as Joseph I said when threatened by a resumption of kuruc raids, “tell them bluntly that we ‘could do even worse’ ”) and magnanimity with pardons for rebel leaders and a guarantee of Hungary’s historic liberties.41 This peace proved durable. As a result, by the time Eugene began preparing for military operations four years later, he was not troubled by the prospect of Hungarian uprisings along his lines of communication and was even able to employ former kuruc rebels in his army.

These earlier preparations helped make possible a sharp, successful war. Charles VI had explicitly requested that the campaign be short, instructing Eugene to achieve a “quick and glorious peace”—partly to avoid creating an opening for crises (groβe Unruhen) on other frontiers, and partly to ensure that any lands won could be secured rapidly and without foreign interference (ohne Mediation).42 The need for a speedy outcome was heightened by growing signs of conflict in Italy, where Spain’s Philip V sought to take advantage of Austria’s distraction in the Balkans to launch an attack on Sicily. As the Turkish war drew to a close, the Spanish challenge was forcing Eugene to siphon off regiments from the Balkans, leading him to lament that “two wars cannot be waged with one army.”43 While Eugene used the opening of negotiations with the Turks at Passarowitz to consolidate Austria’s new gains in the southeast and free up military resources for the west, Charles struck an agreement with Britain and France renouncing his claims to the Spanish throne in exchange for military cooperation against Philip. These measures helped to avoid a protracted two-front emergency. As negotiations wrapped up with the Ottomans, Charles rejoiced to Eugene that “our hands are now free to deal with those who want to chew on us [elsewhere].”44

The physical scale of Eugene’s victory over the Turks was immense. In the concluding Peace of Passarowitz, Austria absorbed, uti possidetis, all the ground that its armies held at the time that hostilities ceased, or a total of some thirty thousand square miles of new territory. The addition of these large spaces bolstered Habsburg security in the southeast. Per Eugene’s advice to “expand following the lay of the land,” Austria absorbed the Banat, closing the gap between its defenses in Croatia-Slavonia and Transylvania. The war also enhanced the size and status of the monarchy’s regional buffers, placing northern Serbia and Little Wallachia under Habsburg rule, while designating Wallachia, Moldavia, and Poland under Article I as intermediary bodies: “Distinguished and separated as anciently by the Mountains, in such manner that the Limits of the ancient Confines may be unchangeably observed on all sides.”45

Passarowitz was a high-water mark for Habsburg power in the Balkans. But it would not last. In the years that followed, Austria’s ability to shape the southern frontier through unilateral military action evaporated as a result of two changes—one military in nature, the other geopolitical.

First, Eugene died. The extent to which Austria’s spectacular battlefield victories had been the result of the prince’s talents became dramatically apparent when the next Austro-Turkish war broke out in 1737–39.46 The parallels with the 1716–18 war are striking. As before, Habsburg officials favored the timing for military action because of the recent end of a conflict in the west (the Polish succession war) and thus recent relative quiescence on other fronts.47

As their predecessors had done prior to 1716, Habsburg diplomats successfully labored to create the conditions for an exclusive focus on the Balkan frontier before going to war. Also like the previous war, Habsburg forces set out to win a short war using mobile field armies. Echoing its earlier instructions to Eugene, the Privy Conference insisted that “the war last but one campaigning season.”48 And as before, the strategic goal was largely defensive: to consolidate and round off Austria’s holdings along the central Danube axis while expanding Austrian influence in the buffer territories of Wallachia and Moldavia.

Without Eugene at the helm, though, Austria quickly found that it was no longer able to rely on rapid strikes to secure its security objectives in the southeast. Poorly led and suffering from the years of neglected military spending that Eugene had so often predicted would lead to catastrophe, Habsburg forces suffered defeats at Banja Luka and Belgrade. In the ensuing Treaty of Belgrade (1739), Austria was forced to disgorge most of its gains from Passarowitz. While using many of the same tactics as in the previous war, Habsburg generalship was weaker, the army had lost its fighting edge, and the Ottomans themselves had incorporated lessons from past wars, adopting improved technology in both small arms and artillery with the help of foreign military advisers.

The second, far-larger change to conditions in the southeast, however, came as a result of geopolitical developments elsewhere. In the year after the war ended, Austria was invaded from the north by the armies of Frederick II of Prussia, setting off what would become an almost forty-year life-or-death struggle for the Habsburg Monarchy.

The Era of Appeasement: 1740s–70s

With virtually all its military resources pulled northward, Austria would not be able to devote the attention to the Balkans that it had in prior decades. But this did not mean that it had no strategic needs in the southeast or could ignore this frontier. Border raiding continued, and the possibility of a Turkish renewal of hostilities to expand on its recent victories had to be taken into account. Russia, too, continued its expansion down the Black Sea coastline. However bad things might get in the north, these dynamics would have to be monitored—and managed. Above all, Austria needed to avoid a Turkish invasion from the south while its armies were detained in Bohemia. And if possible, it needed to recruit Russia’s active help against Prussia.

For these purposes, the Habsburg Monarchy developed a strategy quite different, but no less effective, than the one it had used to expand offensively under Eugene. Instead of mobile field armies, it would rely on appeasement to engage and placate eastern enemies, undergirded by frontier defenses to deter conflict and keep the Balkan frontier quiet without sacrificing ground in its longer-term regional position.

As we will see in chapter 6, Austria’s fight with Prussia in the years between 1740 and 1779 was a bitter contest that would at one point threaten the very life of the monarchy. The severity and length of these wars not only demanded that Austria deprioritize its southern flank but also be able to redirect as many resources as possible from this sector without compromising security there. To support these goals, Vienna pursued policies of proactive engagement with its rivals in this theater throughout the middle years of the eighteenth century. Collectively, these efforts would amount to an almost forty-year strategy of détente in the Balkans, the key pillars of which were appeasement with the Turks, accommodation with the Hungarians, and a defensive alliance with Russia.

The first of these was especially important. The end to hostilities in the 1739 Turkish war, coming barely a year before Frederick II’s invasion of Silesia, left open the possibility of renewed hostilities with the Porte. Given the recent poor performance of Austrian forces and the lingering tension in many sectors of the border, it was not inconceivable that the Turks, emboldened by their recent recapture of Belgrade, would use Austria’s plight in the north as an opening to seize territory—a prospect that Austria’s enemies, particularly France, actively encouraged through aggressive diplomacy inciting the Turks to attack.

The Habsburg response to this threat was a diplomatic offensive as determined and creative in its use of the arts of persuasion as Eugene’s campaigns had been in the art of force. At the official level, Austrian diplomats worked to remove sources of friction, taking less than two years—an astonishingly short period by Balkan standards—to resolve disputes left over from the previous war. Much as Austrian diplomats had massaged Turkish court politics to keep the Ottomans from entering the Spanish succession war, their successors now used similar techniques on a larger scale to deactivate tensions over a period that would stretch from the first clashes of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1740 to the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763.

The architects of these successes were now-forgotten Austrian diplomats stationed in Constantinople. One was Heinrich Christoph Penkler, who assiduously manipulated court dynamics to avoid war. Acting on Vienna’s admonition that a war with the Turks “would be the worst thing that could happen to our court and therefore we must do all we can to turn aside this misfortune,” Penkler outmaneuvered his French and Prussian counterparts, using intrigue, bribery, and propaganda to discourage Ottoman alignments with Austria’s enemies.49 One example of his techniques was the well-timed leaking of the details of the latest Austro-Russian treaty to defuse the threat of Turkey turning its attention north after putting down a rebellion in its Persian provinces.50 Through these efforts, Penkler was able to not only project a greater image of Austrian strength than actually existed but also successfully solicit an Ottoman condemnation of Frederick II’s invasion and extension of the conditions of peace under the Treaty of Belgrade.51 In a subsequent contest with Prussian diplomats from 1756 to 1762, Penkler’s successor, Josef Peter von Schwachheim, used similar methods to forestall a concerted Prussian attempt at enticing the Turks into a formal alliance.

Austria’s success in Ottoman internal diplomacy was the result of centuries of experience navigating the complex politics of the sultan’s court. Key to this mastery was the cultivation, through bribery and favors, of local intelligence through which to not only divine the sultan’s intentions but assess and manipulate the factions among his chief ministers, too. Using these knowledge networks, Austria was able to construct a kind of “early warning system” that told it when rival diplomats’ efforts at agitation were succeeding, and just as important, when the Ottomans were more concerned with problems on their other frontiers. The ultimate testimony to the success of this diplomacy came from Austria’s archenemy, Frederick, who commented that “the Viennese court knows the Turks better” than their adversaries.52

HUNGARIAN ACCOMMODATION

A renewal of Ottoman hostilities was only one of the ways that Austria’s southeastern frontier could complicate its focus on the north in the wars with Prussia; another was an eruption of problems in Hungary. The destructive impact that Magyar uprisings could have on wider Habsburg interests at times of emergency had been shown in the Spanish succession war, when raids by Rákóczi’s kuruc cavalry had forced the Austrians to construct fortified lines and entrenchments on the outskirts of Vienna and siphon off troops from other fronts to protect the Erblände.53

Conditions were ripe for a repeat of such disturbances at the outset of the War of the Austrian Succession, as Austria faced attacks from Prussia, France, and Bavaria. Her susceptibility to Hungarian trouble on this occasion was arguably even greater than in the Spanish war, since Britain’s initial refusal to provide subsidies and Russia’s distraction with a Swedish war deprived Austria of the extent of allied help that it had enjoyed before.54 The war also came at a sensitive political moment with Maria Theresa’s accession to the throne, which would require ratification and coronation by the Hungarian Diet. The Magyar nobility frequently used such moments of transition to register new demands on and extract fresh concessions from a new monarch. These dynamics gave Hungarians the upper hand at the same time that the external situation created a greater strategic need not only for the Habsburgs to ensure tranquil conditions in Hungary but also to find military resources here to contribute to aid in the overall struggle.

Maria Theresa’s approach to dealing with this dynamic replicated the tactics of earlier Habsburg monarchs in their use of accommodation to dampen the embers of separatism and motivate voluntary Hungarian support. While her armies waged war in Bohemia and her diplomats sought to appease the Turks, Maria Theresa engaged in a personal charm offensive with the Hungarian Diet. In exchange for affirming Hungary’s historic rights and reconfirming Hungary’s separate administrative status within the monarchy, the empress was able to not only secure Hungarian support for succession but also extract promises of four million florins and thirty thousand Hungarian troops under the generalis insurrectio (general levee).

Like her forebears Leopold I and Joseph I, Maria Theresa was careful in these barters not to give away too much constitutional ground, restricting her concessions to provisions that could be rescinded to Hungary’s disadvantage if future circumstances dictated. Through these efforts, she was able to “flip” Hungary from a source of potential military concern to an active contributor to the monarchy’s defense. While a portion of the diet’s troop pledges were never fulfilled, the far more important gain from Maria Theresa’s efforts, from an Austrian strategic perspective, was the successful avoidance of what could have become an additional, internal military front at a time when all of the monarchy’s resources needed to be focused on a supreme crisis elsewhere.

RESTRAINING RUSSIA

While appeasing Turkey and accommodating the Hungarians, Austria needed to find a way to deal with its other potential problem in the east: Russia. Here, it had something to build on. As with the Hungarians and Turks, Austria had worked to lay a foundation for future détentes with Russia in earlier years, forming a bilateral anti-Turkish alliance in 1697 and toying with the idea again in 1710 on the suggestion of Eugene as an expedient for forestalling Swedish-Hungarian flirtations. A new pact was formed in 1726, which led to Habsburg participation in the Austro-Turkish War of 1737–39.

As Austria struggled against Prussia, it now needed such an alliance not to check the Swedes or widen gains against the Turks but rather to prevent Russia from stirring up conflicts in the south that would derail Austria’s overall strategy. More than that, it needed to mobilize Russia as an active military partner against Prussia. This goal was forestalled at the start of the Austrian succession war by conflicts in the Baltic with Sweden that prevented Russia from providing meaningful aid to its ally at the height of crisis.

As we will see, the effort to ensure greater Russian involvement against Prussia would become a driving force for Habsburg diplomacy under Kaunitz, second in importance only to recruiting France out of Frederick’s orbit. The centerpiece was a defensive alliance, constructed by Kaunitz, committing the two empires to mutual aid against attacks by Prussia or Turkey, with a secret clause to repatriate Silesia and territorially weaken Prussia. In the ensuing Seven Years’ War, Russia acted as a reliable Habsburg ally, sending a relief army to link up with Habsburg forces at Kunersdorf in a battle that would set a precedent for later, numerous Russian military interventions on Austria’s behalf, including most notably in 1805 and 1849.

FRONTIER DEFENSES

As impressive as Habsburg diplomacy was at appeasing eastern rivals, the monarchy still needed to be able to show military strength on its southeastern frontier. Even amid the wars of the north, internecine border raids, an ancient feature of the Balkans, continued. More important, the placatory diplomacy that Austria used with neighboring rivals depended for its effectiveness on the assumption that the distracted monarchy was still a military factor in the region. To succeed in its overall strategy of deprioritizing the Balkan frontier, Austria therefore needed to be able to maintain baseline security here, and if diplomacy failed, have the means to deter or defeat attacks.

In both tasks, the Habsburgs were aided by the presence of extensive and well-planned defenses along their empire’s southern and eastern approaches. Their backbone was the Militärgrenze, or Military Border, an integrated defensive system that would eventually stretch across the full length of the frontier, from the Adriatic to the Carpathians. The Military Border had its roots in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, which from the fourteenth century onward had organized the Croatian-Slavonian frontier (the Vojna Krajina) into a series of interdependent forts, supported by a militia portalis under the control of the Ban of Croatia, a Hungarian client.55 As the Ottomans penetrated northward, nearby Austrian lands became comanagers of these defenses, supplying money and troops to ensure their maintenance as Hungary gradually collapsed.

By the late sixteenth century, with most of Hungary in Turkish hands, the remnants of the Military Border formed a ragged bulwark protecting the southern approaches to the Erblände and city of Vienna. “Th[is] system of fortresses,” a military appraisal in 1577 told the emperor, “is the only means by which your Majesty will be able to contain the power and the advance of the enemy, and behind which Your countries and peoples will be secure.”56 Keeping these defenses in good working order was therefore a high priority for the Habsburg state, and the origins of the Hofkriegsrat lay in the need to create an institution capable of ensuring their proper supply and administration.

To defend the Military Border, the Habsburgs continued the practice, begun by the Hungarians, of recruiting soldier-settlers from the displaced Christian populations of nearby Ottoman territories.57 To attract these colonists, the Habsburg Monarchy offered incentives that included land, arms, tax exemptions, and religious tolerance in exchange for military service and loyalty to the emperor. Using these allurements, the Austrians were able to attract large numbers of Orthodox Serbs, Croats, Szeklers, and Wallachs to permanently resettle their families in fortified villages, known as zadruga, on the frontier. Administered directly from the Hofkriegsrat, the zadruga were encouraged to maintain high birth rates and operated according to a strict frontier legal. Self-selecting, motivated, and martial, the Balkan colonists provided a cheap and abundant source of military manpower well versed in the irregular “small war” (Kleinkrieg) techniques of the Balkans. “The Grenzer [are] a warlike people,” one Austrian military observer wrote, “so proud of [their] military status that the men retain their muskets and side arms even when they are attending Holy Mass.”58

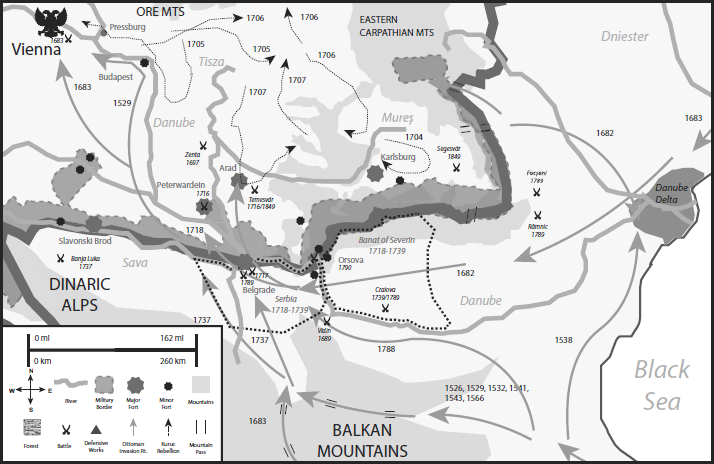

Following the acquisition of new lands in 1699, the Habsburgs expanded the Military Border southward to the new frontier on the Sava, Danube, Tisza, and Maros Rivers. They reorganized it into two main geographic clusters: one along the Slavonian border and centered on the fortresses at Brod and Esseg, and a second along the boundary with Serbia, centered on fortresses at Szeged and Arad on the Tisza-Maros line. In later years, the border would be pushed further eastward into Transylvania following the acquisition of the Banat (see figures 5.3–5.4).59 It would eventually form one of the densest concentrations of military personnel in Europe, with one in ten males under arms by the late seventeenth century, and one in three by the later eighteenth century.60

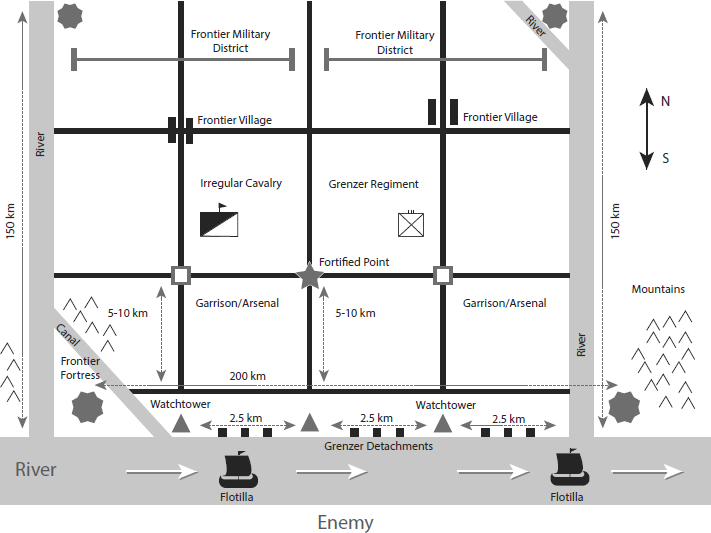

The enlarged Military Border had three main components (see figure 5.5).

Fortresses. At the outer edge stood a line of large fortresses, with a second row some 150 to 200 miles behind them in the interior. The forward fortresses included both updated medieval forts and newer structures, and were usually located at strategic sites on the terrain, such as bends in the river, known invasion routes, or commanding heights above the frontier. They were equipped with heavy artillery capable of dominating the nearby countryside and staffed not by Grenzers but rather German regulars.

FIG. 5.3. Map of the Habsburg Military Border, ca. 1780. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

FIG. 5.4. Detailed Section of Military Frontier. Source: Gabor Timar, Gabor Molnar, Balazs Szekely, Sandor Biszak, Jozsef Varga, and Annamaria Janko, The Map Sheets of the Second Military Survey and their Georeferenced Version (Budapest: Arcanum, 2006).

Watchtowers. Between the forward row of fortresses stood a network of watchtowers, placed at intervals of about a mile and a half. Known as Tschardaks—also called çardaks, ardaci, eardaci, or chartaques—these were two-stories-high wooden huts, usually accompanied by a small trench or palisade to obstruct access to its base. Towers of this kind had a long history as frontier posts going back to antiquity and were not unlike the wooden structures placed at intervals along the Roman limes.61 The Habsburgs had used these for centuries, not only in the south, but occasionally in the west.62 The Tschardaks of the Military Border were guarded at all hours by Grenzer detachments that rotated every few days. A nineteenth-century English traveler described one such post and its guards as follows:

FIG. 5.5. Diagram of the Habsburg Military Border, ca. 1780. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

The sentry-house or Tschardak stood on the height immediately overlooking the sands. It had two divisions, one for the watch-fire, and the other for the soldiers to sleep in. Before this little shed, under the projecting roof, the men had piled their arms. There were six or seven soldiers at the Tschardak, and their dress like their political constitution was half military and half peasant-like. Over the usual peasant’s frock they wore knapsacks, fastened to a leathern strap. Their legs were wrapped in linen or woolen cloths, and their feet covered with those sandals … common to most Eastern Slavonian nations…. No soldiers remain more than seven days together at a sentry post; they are then relieved by six or seven others, who likewise remain a week. Every soldier spends ninety days of the year on guard at these places.63

The spacing of the Tschardaks, never more than a thirty- or forty-five-minute walk apart, meant that if assaulted, a post could depend on rapid support from nearby towers.64 This spacing also allowed for visual communication, mainly through the use of signal fires, which when lit in succession down the length of the frontier could be used to rapidly alert nearby fortresses to an approaching attack.

Logistical infrastructure. A carefully planned support network sustained the Military Border. Connecting the Tschardaks and fortresses were communication roads that ran adjacent to the river and into the interior. Behind the frontier, at intervals of five or ten miles, were strategically located depots and magazines as well as the various zadrugas, sited in easy reach of the border to respond to a crisis. Maintenance of this infrastructure was a high priority well into the nineteenth century. “It is a no less agreeable surprise to the traveler coming from Hungary, or still more from Turkey,” the English traveler wrote, “to observe the good state of the roads and bridges in the Military Frontier.”65

All three components—forts, watchtowers, and infrastructure—were organized into separate districts, each corresponding to a Grenzer regiment, which in turn was split between piquet troops assigned to Tschardaks, and a reserve of infantry and irregular cavalry assembled into mobile frontier units. These were augmented by flotillas of gunboats that patrolled the river between the fortresses.

DETERRENCE AND DEFENSE

The Military Border supported Austria’s goal of safely deprioritizing the southern frontier during the Prussian wars in several ways. First, it dealt effectively with raiding. A permanent feature of Balkan life, border raids varied in scale, and usually involved nighttime attacks across the river to steal livestock, other valuables, and women. These raids were more than simply an irritant. Unchecked, they could pull in army units desperately needed in the north. As both the War of the Spanish Succession and War of the Polish Succession had shown, border incidents could escalate to major crises that threatened to inflame Austro-Turkish relations. By stationing local troops familiar with raiding techniques directly on the frontier, the Military Border provided an effective, inexpensive means of repelling these low-intensity attacks and launching counterraids. Indeed, as late as 1764, the Hofkriegsrat considered 7,000 of such troops to be more than adequate for dealing with “Tatar adventurism” at a moment when it was preparing to deploy 130,000 against Prussia.66

Second, the network of large fortresses around which the border was built helped to deter larger attacks by the main Ottoman army. To be sure, for much of the period of Austria’s wars with Frederick II, the Turks were uninterested in launching an invasion, being detained by internal crises in other parts of their far-flung empire. Habsburg diplomats like Penkler were able to monitor these developments through their intelligence networks. At the same time, attempts by rival diplomats to incite the Turks to open a second front were determined and ongoing. While well informed, Habsburg diplomats could never be sure of the extent to which these efforts were succeeding. The ability to point to Austria’s well-planned and provisioned southern fortresses provided a valuable counterweight to their bribes and blandishments.

Relatedly, the Military Border helped to discourage mischief by the Hungarians. Already in 1672 and 1678, the Grenzers had shown their value in suppressing kuruc revolts.67 In reorganizing the border after Karlowitz, Emperor Leopold had sought to strengthen this function, barring the Magyars from oversight of or participation in border units.68 In the Spanish succession war, the Grenzer had helped to deal with Hungarian insurrections—a role they would play again in 1848–49.69 The presence of loyal troops in situ on the frontier demonstrated that the monarchy had options, even amid the wars in the north, for dealing with local uprisings, thereby placing a stick alongside the carrots that Maria Theresa used to entice the Magyar nobility into helping against Prussia.

The third and perhaps greatest contribution of the border in this era was the aid that it provided to the Habsburg war effort in the north. While holding down the frontier with minimal force, the Grenzers were able to feed large numbers of troops into the battles raging in Bohemia and Moravia for a fraction of the cost that would have been required to field this number of regular units.70 As we will see in chapter 6, the Kleinkrieg raiding techniques of Grenzer troops would prove a crucial component in Austrian military strategy against the Prussians.

The Era of Alliances of Restraint: 1770s–1800s

Austria’s policies of appeasement and accommodation, backed by the defenses of the Military Border, allowed it to manage the southeastern frontier at minimal cost and stay focused on northern crises from the time of Frederick’s first invasion in 1740 until the last standoff with his armies in 1778–79. This approach succeeded in both its principal aims, avoiding the opening of a second front and roping Russia into efforts against Prussia.

During this period, however, geopolitical dynamics in the south had evolved in other ways that were not favorable to Habsburg interests. Most important, Russia continued to grow in strength as a Balkan power. As Austria dealt with Prussia, Russian armies continued their encroachments into Ottoman positions along the coasts of the Black Sea. In 1768, a new czarina, Catherine II, launched Russia’s most ambitious southeastern gambit to date, sending offensive armies across the Dniester that crushed the primary Ottoman fortress at Kotyn and clawed their way down the Moldavian Plain. Within a few months they had captured the capitals of both Moldavia (Jassy) and Wallachia (Bucharest). From here, they then penetrated even deeper into Ottoman territory, eventually reaching positions that were 373 miles from their starting points.

The scale of Russian successes showed the extent of the Ottoman Empire’s decline as well as Russia’s ability to devour large swaths of Balkan territory without Habsburg help. At the war’s end, Austria faced a radically altered situation on its southeastern flank. In place of the old landscape of rickety Ottoman outposts with diminishing military potential and decentralized local rule, there now stood a well-armed and acquisitive Russia, backed by a large military force on the River Bug and fleets at Azov and Crimea, capable of projecting power throughout the Black Sea region. Where Russia had previously been constrained mainly to the northern coastlines of this sea, its offensives down the coastline placed it near the mouth of the Danube and thus astride the main axis of Austria’s traditional path of eastern expansion.

This new reality posed two serious problems for Austria. First, Russian advances threatened the continued existence of regional buffer zones. From the beginning of the century, the maintenance of these intermediary bodies—in the north, Poland, and in the south, Wallachia and Moldavia, or the so-called Danubian Principalities—had been a central objective of Habsburg strategy. Ensuring the independent status of the latter two provinces had been an explicit goal of both Eugene’s 1716 campaign and the unsuccessful 1737 war. The treaties that followed both wars had dealt with the question of their status in their opening paragraphs, with the Karlowitz text stipulating that Wallachia, Moldavia, and nearby Podolia be preserved intact “by observing the ancient boundaries of both sides, [which] shall not be extended on either side.”71

The existence of these buffer territories produced significant strategic advantages for Austria. By ensuring, as Kaunitz later wrote, that Habsburg territories were “not directly adjacent” to the territories of large military rivals, they helped to avoid disagreements that could escalate into war.72 This in turn relieved part of the burden of frontier defense, obviating the need for a large, standing security presence on long stretches of the eastern periphery. As a result, the monarchy could safely concentrate its scarce military resources elsewhere, which as recent events with Prussia had shown was a vital necessity in wartime.

By endangering these spaces, Russian expansion therefore undermined a keystone of Austria’s entire southeastern strategy. While the 1768 war had left the Danubian Principalities nominally intact under Turkish rule, the terms of the concluding treaty (Küçük Kaynarca) granted Russia the ability in the future to intervene here and elsewhere as “protector” to all Christians living in Ottoman territories. Concurrently, Russian inroads in Poland, now in a state of growing internal chaos, were growing.

Second, Russia’s aggressive moves in the east complicated Habsburg strategy at the European level. Austria needed to maintain viable buffers, which meant resisting Russian moves. But it also needed Russia to participate as an active ally against Austria’s archenemy Prussia in the west. The two goals were incompatible. If it chose the latter—the natural choice given the degree of threat posed by Prussia—it would come at the expense of the buffers, which over time could create sources of tension in Austro-Russian relations that could either lead to the loss of Russia as an ally against Prussia or war with Russia itself over the east.

COURTING TURKEY, SPLITTING POLAND

Austria’s initial approach to handling this dilemma was to try to balance against and thus check Russian expansion through alignment with the Ottomans. The fact that Habsburg diplomats were willing to contemplate such a move with the monarchy’s historic Muslim archenemy shows the degree to which they were concerned about Russia’s growing strength as the organizing security problem on the southern frontier. “To save our archenemy,” Kaunitz wrote, “is rather extraordinary, and such decisions can be justified only in truly critical situations, such as self-preservation.”73 While admitting that Habsburg policy would have to strike a careful balance between the two powers, Maria Theresa was unhappy at the thought of striking a deal with a non-Christian state, noting in January 1771,

I have determined that the situation is that the Turks are the aggressors, that the Russians have always demonstrated the greatest respect for us, that they are Christians, that they must deal with an unjust war, all while we are now considering supporting the Turks. All of this and other reasons have convinced me not to engage the Russians…. I must add that I would be even less capable of siding with the Russians in expelling and exterminating the Turks. Both of these points are non-negotiable and, accordingly, one must determine the necessary disciplinary measures [against Russia].74

Tilting toward the Turks to contain the growth of Russian influence, Vienna entered into the so-called Austro-Turkish alliance of July 6, 1771, promising to resist further Russian aggression against the sultan in exchange for monetary and territorial remuneration.75 Much like Kaunitz’s earlier alignment with archenemy France to contain Prussia, the move represented a reversal of long-standing Habsburg policy in order to deal with a near-term threat. To give substance to the new posture, the monarchy deployed forces to the eastern frontier, shifting troops from Italy and the Netherlands to Transylvania, directly across the border from the Russian forces staged in Wallachia.

These moves were ultimately a calculated bluff: Austria had neither the financial nor military strength to sustain a conflict with Russia. Nor, in contrast to its earlier alliance with France, could it hope to obtain much in the way of a lasting strategic benefit from partnership with the teetering Ottoman state against a Russia whose friendship the monarchy needed for sustaining the military competition with Prussia. Within less than a year after it was formed, the Austro-Ottoman treaty was jettisoned as Vienna’s attention turned from the principalities to the adjacent territories of Poland, where by 1771 both Prussia and Russia were actively looking to gain new advantages and territory. To a certain extent, the firmer stance adopted by Austria over the Danubian Principalities, by heightening the danger of a wider European crisis, had contributed to the reorientation of attention northward.

Unlike the principalities, Poland did not involve Ottoman interests, and represented a potential locus for at least short-term cooperation between the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian empires. But the prospect of partitioning the giant territories of the long crisis-plagued commonwealth, by now a subject of active discussion between Frederick II and Catherine II, presented a significant strategic problem for Austria.76 For decades, Austria had sought to maintain the Polish Commonwealth as a buffer state to absorb and reduce conflict on its eastern borders. Over a century earlier, in 1656, it had successfully resisted an attempt by Sweden and Brandenburg as well as Lithuanian and Ukrainian separatists to partition the already internally tumultuous giant.77 Continuing this policy, in the War of the Polish Succession, Austria had worked to prevent the insertion of a Bourbon-backed candidate for the Polish throne and thus forestall the spread of French influence in the region. Throughout these contests, the Habsburg aim was to preserve an eastern glacis in which Austria maintained a vital influence alongside other competing powers while avoiding the extremes of domination by a hostile power, or increased direct responsibility that would be the result of state failure and collapse.

This delicate balancing act, long a mainstay of Austria’s eastern policies, was now threatened by the grim prospect of a partition in which peer competitors Prussia and Russia would obtain not only large swaths of Polish territory and resources but also a more commanding strategic position from which to threaten the monarchy’s northern and eastern frontiers. From a Habsburg perspective, partition was the “least favorable” outcome—a view that Maria Theresa in particular, but initially Joseph II and to a somewhat lesser extent Kaunitz, all shared.78 But the alternatives of either a major European war or Russo-Prussian partition excluding Austria were even more problematic, especially given the monarchy’s financial position. Choosing the least-bad option, in 1772 Austria joined in what would ultimately be the first of three Polish partitions between the three eastern empires. In the first of these, she acquired some 31,600 square miles of territory and 2.65 million inhabitants in the palatinates of Rus, Sandomierz, and Cracow (except for the city itself), which were collectively renamed the Kingdom of Galicia-Lodomeria in commemoration of their earlier, sixteenth-century title and status under the Hungarian Crown.79 In addition, Austria received a portion of the Bukovina—a small but strategic territory that provided a land bridge between Galicia and Transylvania and a promontory from which to monitor future Russian moves on Moldavia.

Once it became clear that Austria would participate in the partition, Habsburg leaders faced the question of how and to what extent to integrate the Polish territories into the monarchy. In keeping with past Austrian practice, Kaunitz preferred to avoid the full incorporation and thus full cost of managing Galicia. Instead, he envisioned the new territory becoming a semi-independent appendage, whose subjects retained a high degree of autonomy and were permitted to show at least nominal obedience in domestic matters to the Polish Diets. Such a Poland would act as both a glacis to future Russian or Prussian expansion and an entry point through which to funnel Austrian influence into the rest of Poland. As a model, Kaunitz looked to the Austrian Netherlands and Duchy of Milan, both of which were administered by the foreign ministry, and neither of which “had any ‘existential’ significance for the Monarchy.”80 By contrast, Joseph II argued forcefully that Galicia should be fully incorporated into Austria’s core territories as an integral component of the Habsburg state.

The disagreement between Kaunitz and Joseph about Galicia’s fate was reflective of the larger debate in Habsburg grand strategy after the end of the Prussian wars—between the desire to maximize security through the maintenance of an expanded army, backed by the resources of a large, consolidated state whose resources were calculatingly leveraged for war, and a more traditionally Habsburg reliance on buffer states, allies, and carefully regulated balances abroad. It also reflected a tension, inherent in the monarchy’s composition, of requiring space, and hence expansion, to be able to keep pace with expanding rivals, but facing steep internal obstacles to fully ingesting and benefiting from the resources obtained through expansion. As we will see, this tension would only grow stronger in later decades with the emergence of nationalism, and the debate between Kaunitz and Joseph about Galicia would play out in more dramatic form in debates between Metternich and Francis I about the fate of Austrian possessions in Italy.

The First Polish Partition demonstrated the growing dilemma facing Austria in the east. It could not merely concede ground to what was becoming an inexorable process of Russian expansion. Yet nor could it resist Russia outright and expect to succeed, given this state’s growing power capabilities and Austria’s critical need for Russian support to deal with the far graver threat of Prussia. In response to this dilemma, Austria’s strategy of the 1770s embraced a third option: to restrain its large eastern neighbor by drawing closer to it.

Elements of such an approach had been present in Austria’s eastern diplomacy for decades; as early as the reign of Joseph I, Habsburg diplomats had seen the idea of allying with Russia in order to monitor and keep pace with its expansion as a core tenet of eastern strategy. The difference, by the reign of Russia’s Catherine II, was the accelerating pace of this expansion and sheer scale of Russian ambitions in regions of strategic interest to Austria.81 The dangers that this expansion could pose, both for Austrian security in the southeast and its broader position in the European balance of power, was made clear by a period of turmoil that ensued after the “unraveling” of its old alliance and the emergence of strained relations with the Russians from 1761 onward.82 In a long memorandum in 1771, Kaunitz weighed the options for how Austria could respond strategically to the steady growth of Russian strength at Turkey’s expense. The document is worth quoting at length:

The main purpose of a solid judgment of important state affairs consists of essentially a true and pure conception of the end purpose, because one must imagine the means that lead to this end purpose. In order to apply this general rule to the current political situation, and to properly judge it from our side, we observed in the war between Russia and the Porte that nothing else is needed, other than the end purpose that we are seeking to achieve, with the means that we have seized thus far, to maintain the status quo against one another, and to find out whether the ultimate purpose we seek would be best for our welfare, and the means that we employed thus far are likewise reasonable for that purpose.

On the one hand, the unpredictable war preparations of the Porte and on the other hand the blind luck of Russian arms have dramatically changed the previous situation and given the Russians such superiority over the Turks that by all accounts is dangerous and must make us think carefully. In this critical situation, we had four potential paths before us:

The first is to put to use the weakness of the Porte and to act against them jointly with Russia.

The second is to take the side of the Porte.

The third is inaction.

The fourth is to attack neither Russia nor the Turks, and instead, as the circumstances permit, to act against both, and thereby to seek to achieve our end goal.

Regarding the last option, merely conceiving of it is sufficient proof of its wrongness. Our hard-won trust and the thereupon grounded solid political credit would be lost at once. We would ruin it for all sides, miss the targeted end goal completely, the threat would increase, and leave us insurmountable consequences.

The third option would leave everything to fate, neither propagating the good nor preventing the terrible, but rather generally the prevailing idea in Europe would be that we, because of Russia’s overpowering strength and unmistakable threat, acted out of fear and hypocrisy. We, at the right time, left behind abandoned our passive behavior, in order to remove the impression of foreboding, which already had started taking root. Nothing remained but to take the Turkish or Russian side. To establish a grounded judgment, obtained from both parties, depends upon an assessment of the following gradations of our own true national interest.

First gradation: ending the current war without both parties maintaining an advantage, although we will keep a few ancillary advantages.

Second gradation: ending the current war on the condition of ancillary advantages for us, established so that Russia has as few advantages as possible.

Third gradation: ending the war such that Russia achieves some vague goals, but simultaneously that we also achieve some of our goals.

If we therefore had, in siding with the Russians, decided against the Porte at the beginning, the immediate consequences thereof would have persisted.83

Kaunitz’s conclusion was that Austria would have been better off “siding with the Russians from the beginning,” as much because of the positive gains it could achieve as from the negative consequences it could avoid. These included both a regional danger—the prospect of Russia achieving a dominant position over the Ottoman Empire—and a broader, European danger—the possibility of heightened Russo-Prussian cooperation at Austria’s expense. The potential for the former was illustrated by the successes scored by Russian armies against Ottoman forces and would be most vividly shown a few years later by the 1774 Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, under which Russia ejected the Turks from their remnant positions on the north coast of the Black Sea and Crimea, and achieved rights of commercial penetration while laying the groundwork for future intervention in Ottoman internal affairs. The Russo-Prussian Treaty of 1764 and coordination between Berlin and Saint Petersburg in the lead-up to the Polish partition both exemplified the latter.

As the 1770s drew to a close, Kaunitz determined that Austria’s best, and indeed only, hope for success was to forge a close and enduring strategic partnership with Russia, and that this should henceforth be a foundational component of Habsburg grand strategy broadly struck. The centerpiece would be a new treaty—the Austro-Russian Treaty of 1781—built around three principle aims.