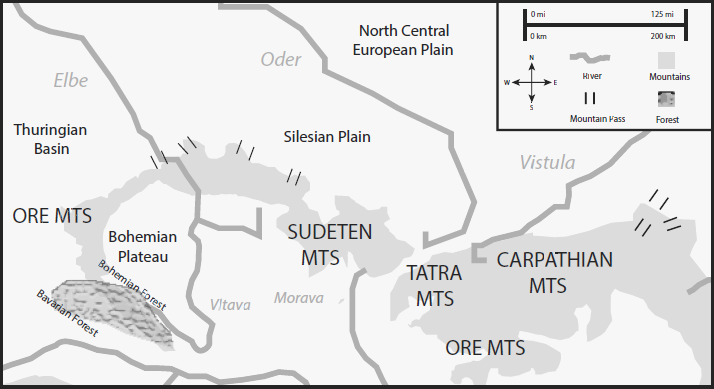

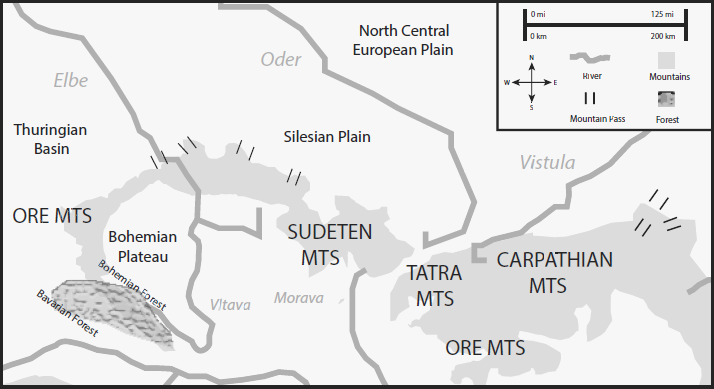

FIG. 6.1. Northern Frontier of the Habsburg Empire. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

“The Monster”

PRUSSIA AND THE NORTHWESTERN FRONTIER

The king of France only gnaws at the edges of those countries that border on it…. [T]he king of Prussia proceeds directly to the heart.

—PRINCE SALM

Fuck the Austrians.

—KING FREDERICK II OF PRUSSIA

ON ITS NORTHWESTERN FRONTIER, the Habsburg Monarchy contended for most of its history with the military Kingdom of Prussia. Though a member of the German Reich and titular supplicant to the Habsburg Holy Roman emperor, Prussia possessed predatory ambitions and a military machine with which to realize them. Under Frederick II (“the Great”), Prussia launched a series of wars against the Habsburg lands that would span four decades and bring the monarchy to the brink of collapse. Though physically larger than Prussia, Austria was rarely able to defeat Frederick’s armies in the field. Instead, it used strategies of attrition, centered on terrain and time management, to draw out the contests and mobilize advantages in population, resources, and allies. First, in the period of greatest crisis, 1740–48, Austria used tactics of delay to separate, wear down, and repel the numerically superior armies of Frederick and his allies. Second, from 1748 to 1763, Austria engineered allied coalitions and reorganized its field army to offset Prussian advantages and force Frederick onto the strategic defensive. Third, from 1764 to 1779, it built fortifications to deter Prussia and finally seal off the northern frontier. Together, these techniques enabled Austria to survive repeated invasions, contain the threat from Prussia, and reincorporate it into the Habsburg-led German system.

At the same time that the Habsburgs were expanding eastward under the Treaty of Karlowitz, they were in the midst of a period of retrenchment in the west. For centuries, the foundation of Habsburg power had been the dynasty’s status as elective leaders of the Holy Roman Empire, or German Reich—an amalgam of kingdoms, principalities, and bishoprics that had endured since its creation by Charlemagne in the eighth century. Since the mid-fifteenth century, the Habsburgs had maintained primacy among the princes of the Reich as their elective emperor, using German resources to extend their power and influence across Europe. In the Thirty Years’ War, imperial armies had fought the combined forces of northern Europe to a standstill, bleeding Germany white and exhausting Habsburg resources.

The end of the war diminished Habsburg power in Germany. The concluding Treaty of Westphalia recognized French and Swedish influence in the affairs of the Reich, and strengthened the sovereignty of its members. More important, the war demonstrated the dynasty’s inability to dominate Germany by force of arms. Afterward, the Habsburgs retained their status as emperors. But the body over which they presided was much changed from its earlier medieval form, now containing wealthy and willful states less constrained than before by German patriotism or loyalty to the emperor, and more conscious of their prerogatives and interests as separate states.

Among the Protestant states that emerged from the Thirty Years’ War was the northern German electorate of Brandenburg-Prussia. Formed through a series of mergers between the Margraviate of Brandenburg, historic seat of the Hohenzollerns, and Duchy of Prussia, former Teutonic vassal to the Kingdom of Poland, the electorate had emerged by the late seventeenth century as the leader of the group of Protestant states, or corpus evangelicorum, within the Reich.1 At face value, Prussia was unimpressive, with a population of 2.25 million in 1740 compared to more than 20 million for Austria. No more prosperous in commerce than its neighbors, it was, if anything, less well endowed for agriculture as a result of the sandy soils of the Baltic region. Indeed, entering the eighteenth century, Prussia possessed few of the attributes that normally explain the rise of a state to Great Power status.

Sparta of the Baltic

What set Prussia apart was its army. To mobilize resources for the incessant warfare engulfing their realm, the electors broke the power of the estates, effectively destroying constitutionalism and laying the foundation for a military-bureaucratic state at an earlier point than any European power except France.2 Under Frederick William I, the “Great Elector,” Prussia spent the middle decades of the seventeenth century creating a strong central government and standing army. In 1701, Frederick William’s son, Elector Frederick III, was able to leverage these strengths to extract consent from Habsburg emperor Leopold I for Prussia to attain the status of a kingdom and its rulers the title of “kings in Prussia.” Under his son, Frederick William I, Prussia became the militarized state with which its name would later become synonymous.

Known as the “Soldier King,” the dour and frugal Frederick William worked to systematically harness the energies of the Prussian state to the task of future war.3 A conservative Junker class provided the substrate for a loyal Officer Corps. A small and scattered but largely homogeneous population, bolstered by immigration from other Protestant states and additional military recruits from abroad, provided the basis for an efficient professional army. In the twenty-seven years of Frederick William’s reign, the Prussian Army would double in size from 40,000 to 80,000 troops, eventually absorbing 1 in 28 male subjects and an estimated 90 percent of the Prussian nobility.4 Maintenance of such a large force required that a high proportion of the state budget (about three-quarters of yearly revenue) be devoted to war. The result was a disproportionate degree of resource mobilization for a country Prussia’s size, with the army as a proportion of the population eventually hitting 7.2 percent compared to 1.2 to 1.6 percent for Austria.5 “It has been calculated,” as Rodney Gothelf writes, “that if other European powers had structured their military along the same lines as Prussia in 1740, then Austria would have an army of 600,000 men and France an army of 750,000.”6

Compared to larger states like France or Austria, Prussia faced the significant geographic disadvantage of being an archipelago of disconnected lands. The territories comprising the Prussian state—what Voltaire called the “border strips”—stretched from the Rhineland in the west through the main Elbe possessions of Brandenburg and Pomerania to the Polish lands in the east. “The consequent problems of self-defense,” writes H. M. Scott, “in the face of hostile and predatory neighbors, were considerable: the furthermost border of East Prussia lay some 750 miles from the Rhineland possessions.”7 In earlier times, Prussia’s central position had made it a highway for invading armies and would again become a significant military liability later in its history. But by the mid-eighteenth century, as Prussia’s military capabilities peaked, the kingdom’s surrounding geography presented it with a target-rich environment for expansion: to the west and south lay a mosaic of weaker German states—Hanover, Braunschweig, Münster, and Saxony; to the east the inert giant of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. A garrison state surrounded by less warlike polities, Prussia was poised to expand. The military machine assembled by Frederick William represented a powerful and largely unchecked tool for shaping the kingdom’s surrounding landscape, should a leader emerge who was inclined to use it for this purpose.

Naked Frontier

One potential target was the Habsburg Monarchy. Though physically larger and more populous than Prussia, Austria’s circumstances in the mid-eighteenth century could hardly have been less favorable for dealing with a major military threat from this direction. Of all Austria’s frontiers, Bohemia was at this time the weakest (see figure 6.1). Unlike in the south, where large expanses of poor territory gave Austria time to prepare for an attack, in the north the threat was a stone’s throw from its richest territories. Unlike in Italy and southern Germany, where numerous buffer states separated Austria from France, in the north there was only one—Saxony—whose coverage of the frontier was partial. To the east, the Oder River valley provided a direct route deep into Habsburg territory. And while mountains sheltered most of the Czech lands, the territory of Silesia, one of the monarchy’s wealthiest provinces, sat exposed on a plain north of the mountains. Once in Silesia, an enemy would have little difficulty transiting the numerous, well-marked mountain passes to strike at the heart of the Erblände, feeding off the fattest Habsburg lands along the way (see figure 6.2).

FIG. 6.1. Northern Frontier of the Habsburg Empire. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

FIG. 6.2. Prussian Invasions of the Habsburg Empire. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

Austria had weak military options for dealing with a threat from the north. Following the death of Eugene, its army had fallen into neglect, suffering defeats in the War of the Polish Succession and then the catastrophic Turkish War of 1737–39. At the end of these wars, Habsburg finances were depleted, and its army was at half strength and scattered across the empire.8 Unlike in the south, Austria’s defenses were virtually naked in the north. The four forts in Silesia at Glogau, Brieg, Breslau, and Glatz were aging and dilapidated.9 The passes were unguarded, Bohemia and Moravia lacked major fortresses, and there were few depots or magazines. A 1736 review of defenses in the area noted these inadequacies but was ignored.10 Nor were Austria’s alliances in good repair. Britain was distracted and weary from its recent war with Spain. Russia was consumed by internal turmoil following the death of czarina Anna.11

Then there was the succession problem. Habsburg relations with allies and foes alike were dominated by the question of the Pragmatic Sanction, a legal instrument created by Emperor Charles VI to ensure the eventual succession of his daughter, Maria Theresa. Under Salic law, the code that had determined European rights of succession since the sixth century, women were barred from princely inheritance. Without male heirs, Charles VI needed to engineer an agreement from other courts to respect the coronation of his daughter when he died and not launch a succession struggle of the kind that perennially wracked Europe. For more than two decades, Habsburg diplomacy was consumed by this quest. Led by Bartenstein, Charles VI’s chief diplomat, these efforts succeeded in winning acceptance from all the major powers of Europe including, notably, Frederick I of Prussia.

Despite Bartenstein’s success, the matter of the succession hung in the air in the years leading up to Charles VI’s death. It was especially problematic within the German Reich, where two members—Saxony and Bavaria—had been the only states in Europe that did not consent to the Pragmatic Sanction. Saxony’s elector, Frederick Augustus II, was married to one of the daughters of Charles VI’s elder brother, Joseph I, and the Bavarian elector, Charles, was married to another. On this basis, both saw for their offspring claims to the Habsburg lands. With the Bavarians, there was the added dimension of a centuries-long rivalry between their ruling house, the Witelsbachs, and the Habsburgs for the title of emperor. Elective rather than hereditary, this title was not covered by the Pragmatic Sanction and therefore vulnerable to contestation after the succession.

These dynamics weakened Austria’s ability to use the Reich as a political tool. Under normal circumstances, it would have provided a natural mechanism to aid in the task of containing Prussian ambition. A federative body in which Prussia was a vassal to the emperor, the Reich offered the Habsburg monarchs levers for influencing and disciplining wayward princelings. One was the Reichshofrat, or Aulic Council, a judicial body through which the emperor could bribe and cajole members involved in territorial feuds.12 The Reich also supplied some military tools. By declaring a Reichskrieg, a collective defense provision not unlike the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) Article 5, the Habsburg emperor could call on the German states to provide military contingents and fulfill financial quotas in support of a war effort. Even in the Reich’s reduced post-Westphalian state, it had proven useful in this role, offering a major addition to Habsburg military power in the war against Bourbon France earlier in the century. Such arrangements, however, were designed to counter threats from outside powers, not from a fellow German power. Such influence as Austria possessed for rallying the military aid of Reich states would be impeded by the inevitable struggles over the title of emperor.

Frederick Strikes

It was in this volatile climate that a new Prussian king came to the throne in 1740. Frederick II was twenty-eight when he succeeded his father. As a youth, there was little to indicate the military prowess of the future Frederick the Great. Frederick’s bent was philosophical and musical; he played the flute, wrote poetry, and corresponded with Voltaire. But his nature was stamped for war. Frederick’s Enlightenment proclivities masked a militaristic, caustic, and controlling personality; he worked feverishly, wrote vulgar doggerel to mock his enemies, and carried a vial of poison around his neck in case he failed in battle.13 Misogynistic and atheistic, he referred to Christianity as an “old metaphysical fiction” and preferred the company of men.14 It would be hard to imagine a ruler more different from the conservative, pious, and often-temporizing monarchs of the Habsburg Empire.

From his father, Frederick inherited a well-drilled army of ninety thousand and budget surplus of eight million taler.15 In Silesia, he saw a vulnerable and valuable prize that, if taken, would enrich his small kingdom and round off its southern frontiers. Rich in metals, and home to a third of Habsburg industry and annual tax revenue, Silesia was one of the richest territories in Europe. Frederick was scornful of the Habsburg Army’s ability to hold these territories. As a younger man he had accompanied Eugene of Savoy to the siege of Phillipsburg and been appalled by the laggardly comportment of Austrian troops. Contemptuous of the Habsburgs as a dynasty and eager to expand his realm, he had no compunctions about seizing their lands or even, if circumstances permitted, dismembering their realm altogether.

When Charles VI died on October 20, 1740, Frederick was ready to strike. In addition to a march-ready army, the Prussian king had made secret overtures to France to arrange the opening of a second front against Austria in the west once the war begun. On December 16, without a declaration of war and disregarding his father’s consent to the Pragmatic Sanction, Frederick led twenty-seven thousand troops across the Austrian frontier into Silesia. The invasion marked the beginning of nearly forty years of running conflict and crisis that would see the Habsburg heartland repeatedly invaded, involve fighting on every Habsburg frontier except the Balkans, and eventually engulf all of Europe and much of the known world. For the House of Habsburg, these wars would be as desperate as the Turkish invasion of the previous century, longer than all of Austria’s previous eighteenth-century wars combined, and more threatening to its existence than anything it would face until the revolutions of the mid-nineteenth century.

Survival and Strategy

The Habsburg ruler who bore the brunt of these wars was Maria Theresa.16 The dynasty’s only female monarch, she was twenty-three years old when her father died in winter 1740. Like Frederick, Maria Theresa had little prior experience in affairs of state and even less exposure to the military. Also like Frederick, she was drawn to the rationalist ideas of the Enlightenment, and would become perhaps the boldest and most successful state reformer in Habsburg history. But unlike Frederick, Maria Theresa was deeply religious and familial, eventually producing eleven children. Intelligent, resolute, and hearty in physical constitution, she later described the daunting scene she found on taking the throne, “without money, without credit, without army, without experience … without counsel.”17 In the years that followed she would be animated by a hatred of Frederick, whom she called “the Monster,” and as determined to retake Silesia as he was to keep it.

From the outset, the main problem facing Maria Theresa was the military superiority of her enemy. A revisionist-minded ruler with a powerful army, Frederick possessed the advantage of the strategic initiative and, it quickly became apparent, tactical dominance on the battlefield as well. His forces, and in particular his infantry, outmatched hers in almost every regard—leadership, logistics, discipline, speed, and offensive spirit. Under Frederick’s gifted command, Prussian armies were virtually unbeatable in the early phases of the conflict. And while Habsburg fighting skills would improve substantially over time, eventually surpassing the Prussians in cavalry and especially artillery, Frederick would prove capable of inflicting defeats on larger Austrian armies all the way into the 1760s.

In formulating a response to the Prussian challenge, Maria Theresa did not have the benefit of a sustained period of reflection or preexisting strategic framework of the kind that her predecessors had in dealing with the Turks. The enemy was present, active, and powerful; the threat was existential. The methods that Maria Theresa and her advisers developed for handling this problem were initially reactive, aimed purely at survival. Yet they would congeal over time into a coherent set of strategies specifically tailored to the Prussian threat. Viewed collectively, they were rooted in the premise, familiar to weak states throughout history, that the best way to defeat an unbeatable enemy is to avoid fighting on their terms. Unable to overpower Frederick on the battlefield, Maria Theresa would try to outlast him. The essence of her approach was the defensive use of time, both on the battlefield, by employing terrain to deny combat until conditions were favorable, and in diplomacy, to avoid bearing the full brunt of war until Austria’s alliances and military manpower could be mobilized.

This basic template would endure throughout the long contest with Prussia and can be broken into three phases. In the first war (1740–48), Austria fought to preserve itself using delay, sequencing, and harassment. In the second war (1748–63), Austria sought to recuperate and retake Silesia using restructured alliances and a reformed army. And in the third war (1764–79), Austria used preventive strategies to seal off the frontier and deter future attacks.

Preservative Strategies: Stagger and Delay (1740–48)

In the opening phases of the War of the Austrian Succession, Habsburg strategy was defined less by what could be achieved than by what must be avoided.18 Maria Theresa’s aims can be understood as the inverse of Frederick’s. Opportunistically revisionist, Frederick sought a short and decisive conquest of Silesia, fought on his terms, and concluded by diplomatic ratification, and to support this goal, a wider conflict that by bringing other invaders into Austria, would increase his bargaining position and the pressure to cede Silesia. Maria Theresa needed the opposite: time to mobilize her resources and “turn off” other threats to focus on her greatest threat. Over the course of the eight-year conflict, Maria Theresa crafted strategic tools, some rough and ready, and others derived from prior Habsburg military and diplomatic culture and prior experience, to achieve both goals and manipulate the timing of the contest to its advantage.

BUYING TIME TO MOBILIZE

Austria’s opening moves were dictated by the imperative of warding off existential threats to the Erblände while setting in motion a mobilization of resources that would take time to bear results. By 1741, four invading armies sat on Austrian soil and the situation was desperate; as one minister wrote, “The Turks seemed … already in Hungary, the Hungarians already in arms, the Saxons in Bohemia and the Bavarians approaching the gates of Vienna” (see figure 6.3)19

While dispatching armies to the north, Maria Theresa reached out to traditional allies—England, Holland, and Russia—to organize military pressure on Frederick’s flanks, and get subsidies flowing to fund the scale of mobilization that would be needed to get Austria’s scattered and poorly equipped regiments onto the field. In rallying this coalition, the empress concentrated on those powers that had reasons to fear Prussian ambition. This included in particular the states closest to the revisionist powers: Hannover, and through it, its patron Britain; Saxony, Prussia’s weaker southern neighbor; the Dutch, sandwiched between France and Prussia; and Piedmont, vulnerable to both Spain and France. Such a collection of states, like all coalitions in war, would be difficult to coordinate and hold together. But much as Austrian diplomats had used fear of French hegemony to align otherwise status quo–minded states behind the monarchy in the wars with Louis XIV, fear of Prussian strength now provided a powerful glue for a defensive coalition.

As she rallied allies, Maria Theresa also moved in the opening stages of the war to mobilize the monarchy’s own armies and resources. Because the enemy occupied Silesia along with most of Bohemia and Moravia, these efforts would need to be focused on Austria proper and the territories to the south and east. That meant Hungary. This was a challenge, given the dynasty’s long-standing difficulties organizing regiments and munitions from the Magyar nobility. In addition, Maria Theresa still needed to win the formal ratification of her succession from the Hungarian Diet. But above all, it was imperative that Austria avoid a Hungarian uprising so as to take advantage of the crisis in the west—a crisis of the kind that had distracted Habsburg attention and resources during the Spanish succession war.

FIG. 6.3. Austria under Attack, ca. 1741–42. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

Against the odds, Maria Theresa accomplished all these goals. Weak as the monarch may have been amid the Prussian invasion, she still had two levers with the Hungarians: constitutional concessions and Magyar pride. Traveling to Pressburg, Maria Theresa appealed directly to the Hungarian Diet. From start to finish, the trip was a public relations coup. Arriving by the Danube on a boat festooned in Hungarian red, white, and green, the young empress used her presumed frailty to charm the Magyar magnates and excite their sense of duty. For months prior to the trip, and though pregnant, Maria Theresa had practiced her equestrian skills in anticipation of the coronation ceremony, which required her to ride to the top of a hill to receive the Crown of Saint Stephen. She also brought constitutional concessions, widening the kingdom’s tax exemptions and confirming Hungary’s separate administrative treatment in Habsburg government.20 Her methods worked.21 The Hungarians not only approved her succession but also called a generalis insurrectio, promising more than thirty thousand troops, mostly cavalry, and four million florins for the war effort. While many of these pledges would never be met in full, Maria Theresa’s diplomacy had accomplished something more valuable: prevention of a Magyar revolt through the duration of the Prussian wars.

More effective for Habsburg needs was Maria Theresa’s mobilization of the hardy regiments of the Military Border. As we have seen, the Grenzers were not conventional soldiers in the European mold but rather irregular fighters trained in the methods of Kleinkrieg—raiding, harassment, and guerrilla hit-and-run tactics. Use of such soldiers on western battlefields had not been attempted on a large scale. But for Maria Theresa, these troops represented an untapped manpower pool that was numerous, loyal, and as events would prove, terrifyingly skillful. In the years that followed, the Military Border would contribute large numbers of troops to the Austrian armies in the west: 45,000 in the Austrian succession war (out of a total Habsburg Army of 140,000), and 50,000 in the Seven Years’ War, all for about a fifth of the cost that would have been required to field similar numbers of regular units.22

DIVIDING ENEMIES

Maria Theresa also employed what would become a signature Habsburg technique of the wars with Prussia: sequencing the conflict to avoid fighting all her enemies at once. Austria had used such methods to juggle between fronts in Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, and Hungary in the War of the Spanish Succession (see chapter 7). In the opening war with Frederick, it faced a similarly dispersed set of challenges. In addition to France, Prussia was joined in its invasion by the armies of Bavaria and Saxony. As the conflict widened, Spain became involved as an enemy of Austria as well as smaller Italian players, Genoa and Naples. Altogether, before the war ended, Austria faced active fronts in Bohemia, Moravia, Upper Austria, the Rhine, and Italy.

If Austria tried to fight all these enemies simultaneously, it would lose. The monarchy was particularly susceptible to exhaustion in the early phases of the conflict, when its allies had not yet taken the field and its own forces were still assembling. To survive, it needed to find ways to concentrate scarce resources until the balance of power had begun to swing in its favor. Maria Theresa did this in several ways.

First, she worked to prevent new enemies from coming into the war. One technique that Austria had learned in the Spanish succession war, as discussed in chapter 5, was to proactively appease threats that had not yet entered an existing conflict. Engagement with the Hungarians was done with this in mind. Similarly, Maria Theresa worked to ensure quiet relations with the Ottoman Empire. Repeating methods used earlier in the century by Joseph I, Maria Theresa sought to tamp down tensions with the Turks, ordering her diplomats to wrap up outstanding issues from the recent war and employing bribery in the sultan’s court to ensure that the Porte did not enter the war on Prussia’s side.

Second, Maria Theresa sought to prioritize among the various enemies that had already entered the war. Among these, Prussia represented the ultimate danger, but also the one that Austria was least prepared to fight at this stage. Maria Theresa therefore sought a temporary peace, or recueillement, to recover strength and concentrate elsewhere. Early on in the conflict, she had instructed her diplomats to seek a cease-fire with the Prussians for precisely this purpose. Frederick himself, who wanted a short war to grab Silesia, eventually provided the opening. Using this urge to their advantage, Austrian diplomats brokered the Convention of Kleinschnellendorf, a temporary peace that allowed their armies to disengage in the north. That their purpose was to concentrate against other foes can be seen in the fact that Maria Theresa rejected Frederick’s offer of a “general pacification” in the conflict.23 The Austrian Empress wanted the war to go on, only on her and not her enemies’ terms. That she intended to resume the contest with Frederick once she had dealt with other foes is illustrated by the fact that her diplomats would not cede permanent ground to the Prussians in the convention, ultimately only consenting to a loss of parts of Silesia, and vaguely.

Third, with this cease-fire in place, Maria Theresa prioritized the gravest danger: a Franco-Bavarian threat to Upper Austria and the capital. In the Spanish succession war, Austria had been able to safely deprioritize the Erblände when threatened by kuruc forces from the east, relying on hastily erected defenses to keep the raiders at bay while focusing on economically valuable lands in Italy.24 But a threat from conventional European armies was a different matter. In late 1741, such a threat existed in the form of a Franco-Bavarian army that had moved in force into Upper Austria and captured Linz. With the north quieted by the cease-fire, Maria Theresa massed Austria’s forces against this threat, sending reinforcements from Hungary while shifting troops from Silesia and Italy. Launching a winter offensive unusual for Austrian armies in the eighteenth century, the monarch took the enemy off guard, pushing them out of Austria and across the Bavarian frontier.25 While the move came at the expense of temporarily ceding Silesia to Prussia and weakened Austrian positions in Italy, it consolidated Austria’s position on home territory and instilled confidence in the monarchy’s foreign allies.

With her concentration of force in Upper Austria, the empress had placed Bavaria, the smallest member of Frederick’s coalition, on the defensive, forcing its units to return home from their deployments in Bohemia. She now moved Austrian forces into Bavaria, including large numbers of Croats and other Military Border units, which savaged not only the enemy army but the civilian population, too. Militarily, the move chiseled off a target that the Habsburg Army could handle, depriving Frederick of an ally once the war in the north was resumed. Politically, it dealt a severe blow to the home base of the elector of Bavaria, the Habsburgs’ main rival in Germany who became Holy Roman emperor following the succession. By making this move early in the conflict, Maria Theresa sent a message to the other Reich states about Austria’s continued military potency, increasing the likelihood that they would side with her as the war progressed.

GUERRILLA WAR

Maria Theresa’s effort to sequence the war to Austria’s advantage was made possible not just by diplomatic cease-fires but also by guerrilla war. While concentrating against the Bavarians, the empress had to find ways of ensuring that the large enemy forces still in Bohemia and Moravia were not neglected altogether. The main method that she used to preoccupy them was Kleinkrieg, the practice of irregular warfare imported from Austria’s southern frontier. Maria Theresa had a wild assortment of troops available for this task that included Hungarian hussars and other frontier light cavalry as well as large numbers of Croat, Serb, and Hajduk irregular infantry. Known collectively as Pandurs, these forces comprised not only regimented Grenzers of the kind organized in the Military Border’s administrative districts but also numerous free corps raised specifically for the war. The latter often consisted of rogue elements—bandits, criminals, and adventurers—assembled from the hard-scrabble Balkan countryside.26

The fighting techniques used by these troops were quite different from the linear warfare of the period on which Frederick had based his military machine. Kleinkrieg was a savage form of warfare similar to that practiced by the Cossacks, Comanches, and other tribal irregulars found in the world’s frontier regions. A contemporary observer described them as

fierce to the highest degree; they live among mountains and forests, are inured to hardships from their infancy, and live more by hunting and fishing than by the milder arts of manufacture and cultivating the ground. Every enemy with whom they are at war, have complained of their want of generosity after a battle, and of their rapine and barbarity when stationed in a country with whom their Sovereign is at war.27

The Prussians feared the Pandurs. As one of Frederick’s officers wrote, “They are always hidden behind trees like thieves and robbers and never show themselves in the open field, as is proper for brave soldiers”28 Frederick told his generals that they could do little to harm Prussian units in the field, but that “it is a different question in the woods and mountains. In that kind of terrain the Croats throw themselves to the ground and hide behind the rocks and trees. This means that you cannot see where they are firing from, and you have no means of of repaying them for the casualties they inflict on you.”29

Deployed against the Prussians and French in Bohemia, the Pandurs targeted supply lines, depots, baggage trains, and isolated detachments. Such methods hit the weak spot of eighteenth-century armies: the logistical arteries supporting armies in the field. Their raids were especially effective against Frederick’s army in Moravia in winter, when the Prussians needed to forage for provisions. Pandur units mercilessly stalked Prussian detachments in the countryside, wearing down their numbers, munitions, and morale. Frederick complained, “We are going to be flooded with Hungarians, and with the most cursed brood that God has created.”30

Resistance by the local population augmented Pandur raiding. Resentful of the heavy-handed Prussian occupation, Moravian peasants were encouraged by Vienna to fight, and in turn, equipped with weapons and instructors from the Austrian Army.31 Together, the Pandurs and local insurgents harassed the Prussians, allowing Austria to concentrate the bulk of its regular army elsewhere. When Frederick finally left Moravia, his forces were weakened and demoralized for the next phase of the conflict.

When Austria did engage the Prussians on a large scale, it looked for ways to magnify the strategic effects of its irregular forces on the enemy. The moment came in 1744, when Frederick ended the temporary peace and invaded Bohemia yet again with eighty thousand troops. This time he quickly took Prague and penetrated south to threaten Vienna while the main Habsburg Army was deployed on the Rhine against the French. Redirecting her forces, Maria Theresa now had much larger and more experienced armies than earlier in the war. Prince Charles of Lorraine and his lieutenant, Field Marshal Count Traun, commanded these forces.

Traun was a capable officer who had won distinction in the War of the Polish Succession at the siege of Capua, where he held out for seven months with six thousand troops against a Franco-Spanish force of twenty thousand.32 The strategy that Lorraine and Traun employed against Frederick sought to deplete Prussian strength rather than confront it directly. With Bavaria neutralized and French armies pushed back into Germany, Austria would be able to concentrate significant numbers against Frederick in Bohemia once its forces had been collected from their far-flung stations. Learning from its earlier guerrilla methods in Moravia, Austria’s commanders believed that if they could deny Frederick the possibility of provisioning from the countryside, he would have to quit Habsburg territory. As Lorraine wrote to his brother, if Frederick persisted in driving so hard into the province, it would be easy to starve him out; “I believe God has blinded him, because his movements are those of a madman.”33 Frederick himself quickly saw the difficulty of his position, finding that despite the strength of his armies, he was unable to subdue the land, whose entire population “from the high nobility, to the city mayors and general public spirit are devoted to the House of Austria.”34

With the populace on their side and reinforcements converging from the west, the Austrians played for time, harrying and exhausting Frederick’s forces. Exploiting Frederick’s weaknesses, they avoided pitched battle and made careful use of the terrain, skirting enemy columns along major rivers and selecting strong defensive locations for encampment. In these movements, Traun reflected Montecuccoli’s admonition that “even limited battle should be sought only when one has superior numbers and troops of better quality.”35 In today’s terms, Traun’s methods resembled what would be called a “logistical persisting” defense—the practice of creating an inhospitable environment in which an invader can neither sustainably victual themselves nor bring the defender to decisive engagement.36 Accompanied by swarms of Pandurs, Traun’s forces chipped away at Frederick’s rearguards and flanks until Lorraine arrived with the main army, by which point the Prussians had been sufficiently depleted and were able to be driven out of the province without a major battle.

Recuperative Strategies: Allies, Artillery, and Revenge (1748–63)

Austria survived the war of succession but at an enormous cost, spending eight times its annual revenue on the war, losing hundreds of thousands of lives, and seeing its richest province consumed by Prussia.37 As the war drew to a close, the writing was on the wall: if the House of Habsburg wanted to endure, it would need to be better prepared for the next phase of the war. Even before hostilities ended, Maria Theresa had already begun to make provisions for the future. She was assisted in these tasks by Kaunitz, who would come to exercise a dominating influence over Habsburg diplomacy for almost forty years from the time of his appointment as state chancellor in 1753 until the start of the French wars at century’s end.38 A member of the old Moravian nobility, Kaunitz had served during the previous war as an envoy in Italy and the Austrian Netherlands, and later as the chief Habsburg representative at the concluding peace of Aix-la-Chapelle. Eccentrically brilliant—“individualist, hedonist, humanist, and hypochondriac,” as Franz A. J. Szabo describes him—Kaunitz brought talents to Habsburg statecraft not seen since Bartenstein that would only be surpassed decades later, perhaps, by Metternich.39 He formed a close bond with Maria Theresa similar in some ways to the relationship between Disraeli and Queen Victoria, holding, as one historian put it, “power like that of a demonic seducer” in matters big and small.40

Using this influence, Kaunitz would decisively shape Habsburg diplomatic and military strategy as the monarchy prepared for the inevitable renewal of hostilities with Frederick II. His signature contribution was to engineer a seismic shift in Austria’s alliances, away from the centuries-old enmity toward France and dependence on England, the latter of which had proven to be a demanding and not altogether reliable paymaster in the previous war, toward closer ties with France and Russia. As early as 1749, Kaunitz had begun to argue for a move in this direction on the premise that Prussia was likely to remain the greatest security threat facing the monarchy for the foreseeable future. In France, Kaunitz saw a power that shared Austria’s status quo orientation and was likely to feel threatened by Frederick’s restless territorial ambitions.

Together with the continent’s other large land power, Russia, Kaunitz correctly identified France as the state that, unlike sea-bound Britain, would be best positioned to help Austria militarily in a future crisis. At Aix-la-Chapelle, he laid the foundation for this landward reorientation of Habsburg diplomacy by deprioritizing the Austrian Netherlands in favor of a strengthened position in Italy, thus reducing Austria’s reliance on the Royal Navy.41 As ambassador to France from 1750 to 1752, he labored to engineer a rapprochement with Versailles, which finally bore fruit in the so-called Diplomatic Revolution of 1756—a defensive alliance providing mutual aid against Prussia. As a makeweight to these arrangements, he brokered a renewal of the 1746 treaty with Russia “ ‘to make war against the King of Prussia’ in order to reconquer Silesia and Glatz and place him in a position whereby he could no longer disturb the peace.”42

At the same time, Kaunitz worked to restore confidence in Habsburg power among the Reich states. Maria Theresa had this goal in mind in the late phases of the succession struggle when she treated generously with those members that had sided against Austria. At the Treaty of Füssen in 1745, she had given the Bavarians, still recovering from despoliation by the Pandurs, new territory while occupying key towns as “hostages” to guarantee their support for the reelection of a Habsburg as Holy Roman emperor.43 By dealing with Bavaria and Saxony magnanimously, Maria Theresa had strengthened Reich support for the monarchy as, in the words of one Austrian memo, “neither an all-powerful nor an all-too-powerful” hegemon.44

Maria Theresa also worked systematically to strengthen Austrian domestic capabilities for war.45 Acting under the dictum that “it is better to rely on one’s own strength than to beg for foreign money and thereby remain in eternal subordination,” Maria Theresa and her advisers, above all Kaunitz and the able Count Haugwitz, undertook a wholesale reorganization of the Habsburg state and economy. In 1748, the year the war ended, she succeeded in the long-running battle to curb the Estates’ power, introducing requirements for higher and more predictable contributions to the budget.46 She launched a comprehensive census, tallying the properties of rich and poor alike, and streamlining tax collection. Maria Theresa also slimmed government to cut waste, eliminating redundant institutions and subjugating provincial bodies to Vienna. To staff this rationalized bureaucracy, she expanded the political elite, issuing new patents of nobility and pardoning nobles who had been disloyal in the war. She worked to abolish remaining vestiges of feudalism, reducing the work obligations of the peasantry and transferring their regular labor quota—the hated Robot—into fixed cash payments.47 These changes not only made revenue flows larger and more predictable in wartime but also increased the loyalty of the populace to the Crown. These reforms had a grand strategic purpose: to bring greater military capabilities to bear, on a more durable and predictable basis, for sustaining the contest with Frederick the Great and ensuring that Austria would be more likely to succeed in its next installment. The result, as one historian has written, was a “revolutionary metamorphosis” in the Habsburg Monarchy—brought about by “a coherent masterplan” executed over the span of nearly fifty years—that was aimed at “increase[ing] the state’s authority, resources and organizational capacity.”48

Inevitably, Maria Theresa’s reforms also reached deeply into the Habsburg military, beginning at the level of command and control.49 The Hofkriegsrat was overhauled in an effort to create a leaner institution focused on its core function of war planning. The number of staff members was cut, and the functions for military law and logistics were decoupled into separate institutions. The latter became the function of a new military commissariat, charged with bringing order to the chaotic supply system that had crippled Austrian forces in the early stages of the last war, alongside the new Corps of Engineers.50 A new military academy was created at Wiener Neustadt as well as a finishing school for officers and revamped engineering academy. At the rank-and-file level, the army was expanded to create the basis for a standing force of 108,000 troops. Maria Theresa worked to increase Hungarian military contributions, merging Magyar and non-Magyar units, and making the army an outlet for Hungarian social mobility.51 She also sought to more systematically leverage the full manpower potential of the Military Border. The previous war had shown the enormous potential that the Grenzers held for warfare in places other than the frontier. Halfway through it, Vienna had begun to look for ways to maximize its contributions. Under Prince Joseph Sachsen-Hildburghausen, a new military code was introduced, and the unpredictable free corps was replaced by larger and more standardized formations.52 Importantly, these organizational changes were made without attempting to alter the indigenous warfare methods of the Grenzers.

While expanding the size of the army, Maria Theresa also sought to improve its quality. Recent battlefield experiences offered abundant lessons in tactics and technology. To absorb these, the Military Reform Commission was created and given the task of systematically preparing the forces for future conflict.53 Chaired by Lorraine, it was composed of officers with combat experience from the recent war, including Field Marshal Daun, a talented disciple of Traun who had assisted in the successful relocation of the army from the Rhine in the 1744 campaign, and Prince Joseph Wenzel von Liechtenstein, who had led Austrian forces to victory in Italy. Within a year of its creation the commission produced a standardized drill manual. The first of its kind for Austrian forces, the new Regulament simplified infantry movements and tactics on the Prussian model, implementing changes that would remain in place until 1805.54 To learn the Regulament and improve tactics, the army formed large exercise camps in Bohemia to retrain, drill, and equip large formations.55

In the technological realm, the Austrians devoted particular attention and resources to improving the artillery. For armies of this period, the artillery represented the most labor- and capital-intensive weaponry to develop, requiring large-scale state investment, advanced metallurgy, and industry to produce. In their collisions with Prussian forces in the 1740s, Austrian armies had found that they lagged dangerously behind in this technology. Overcoming this disadvantage became the focus of a major modernization effort after the war. Achieving “catch-up” in artillery was not a quick or easy task, requiring not only the development of the weapons themselves but also the cultivation of specialized technical skills and a supporting military body to sustain them.

The effort to improve the artillery was led by Prince Liechtenstein. A member of one of the wealthiest families in Europe, Liechtenstein had almost been killed by Prussian artillery at the Battle of Chotusitz in 1742. Drawing heavily on his own wealth, the prince funded ballistic experiments and created a new artillery corps headquarters in Bohemia.56 Altogether, Liechtenstein spent ten million florins on the project, eventually producing a new class of improved guns in 1753.57 His efforts essentially comprised a private research and development facility that moved more quickly than would otherwise have likely been possible. A measure of Liechtenstein’s success can be seen by comparing Austria’s artillery in its first and second wars with Frederick’s. In the first, it possessed 800 artillerists. In the second, it had 3,100 men servicing 768 guns, supported by specialized fusilier, munitions, and mining detachments.58 From one of the Habsburg Army’s most neglected elements, the artillery would become its corps d’elite with a claim to being “18th-century Austria’s major contribution to the art of war.”59

By reforming alliances and expanding the army, Maria Theresa and Kaunitz sought to position the Habsburg Monarchy for renewed war with Prussia. The goal was partly offensive in the sense that they were preparing to initiate a conflict to retake Silesia. Like Carthage after the loss of Spain to Rome and France after Prussia’s seizure of Alsace-Lorraine, Austria’s leaders were animated by the desire to repatriate a province that was not only economically valuable but symbolized their monarchy’s strength and influence in the balance of power as well. Viewed more broadly, however, her efforts were based on the correct assumption that Frederick would continue to launch revisionist wars in search of more territory. While the immediate aim was to take back Silesia, Austria’s leaders wished to substantially reduce Prussia’s potential as a long-term threat to their state. Kaunitz envisioned “a post-war environment without the evil of ‘remaining armed beyond our means and burdening loyal subjects with still more taxes rather than granting relief from their burdens.”’60 In this sense, Maria Theresa’s aims were preventive in nature, intended to restore lost balance and preclude future disruptions on the scale that Austria had narrowly survived in the 1740s.

To achieve this goal, Maria Theresa and Kaunitz pursued a strategy of two parts. First, they would seek to field a larger number of allies than Austria had possessed in the previous war to take the offensive against Frederick. By allying with France and Russia, Austria would be able to exploit Prussia’s own interstitial geography, thus shifting the economic burden of war away from the Habsburg home territories and onto Prussia itself. In addition to Russia and France, Austrian diplomacy succeeded in bringing Saxony, which had changed sides in the previous war, and traditional enemy Bavaria on board as allies. Second, as a by-product of these alliances, Austria’s leaders sought to achieve a greater concentration of force for the Habsburg Army than it had in the previous war. The absence of threats from France and Bavaria would enable Austrian forces to concentrate on one unified front against Prussia. Prewar treaties aimed at pacifying the Ottoman and Italian fronts further supported this goal. Paradoxically, the loss of Silesia allowed the army to develop improved forward positions on the defensive terrain around Bohemia’s rivers. Here, Austrian commanders planned to concentrate the monarchy’s now-enlarged forces.61

Anticipating Maria Theresa’s intentions, Frederick launched a preemptive strike into Bohemia in August 1756.62 Frederick’s war aims were similar in some ways to those of the previous war, except that now he had to anticipate moves by the two large powers to Prussia’s east and west—Russia and France—that Kaunitz had recruited as Austrian allies. To avoid subjecting Prussia to a multifront war of the kind he had previously inflicted on Austria, Frederick needed to achieve a fast knockout punch against his chief adversary, thereby discouraging French and Russian action altogether, or if this failed, be in a position to pivot his forces against the other two armies from a central position.63 To this end, he envisioned a fall campaign in 1756 to neutralize the Habsburg buffer state of Saxony, followed by a penetration into Bohemia the following year, where his forces would be provisioned at his hosts’ expense in order to “disorder the finances of Vienna and perhaps render that court more reasonable.”64

After a rapid conquest of Saxony, Frederick crossed the frontier into Austria in April 1757. As in the last war, he entered through the familiar mountain passes, this time bringing seventy thousand troops, more than double the size of his first invasion. As in the last war, he advanced on a line offering multiple objectives in order to pin down Austrian forces in the empire’s richest province, Bohemia, while threatening to raid Moravia or move in force against Vienna. And as in the last war, Frederick scored early successes against the Habsburg forces that he encountered, foiling an attempted linkup of Austrian and Saxon forces at Lobowitz in 1756, and defeating the Austrian Army outside Prague under its commander in chief, Lorraine, who despite numerous defeats at Prussian hands in the previous war retained a prominent political place in the Habsburg Army as Maria Theresa’s brother-in-law.

Notwithstanding these similarities with the previous war, Frederick quickly saw that he was dealing with a very different Austrian Army than the one he had encountered in the past. From the outset, Habsburg forces managed to use enhanced logistics and planning to achieve higher force concentrations in forward theaters than in the previous war, with thirty-two thousand troops in Bohemia and twenty-two thousand in Moravia by the time the Prussians entered Austrian territory. This positioning allowed Austria to contest Frederick more effectively from an earlier point in the campaign, preventing both the easy utilization of Habsburg resources and speedy knockout punch that Frederick depended on for his overall strategy.

At the tactical level, too, Austrian forces showed the benefits of Maria Theresa’s reforms, inflicting higher costs on Prussian forces even in battles where they were forced to retire from the field. In his initial encounter with Austrian forces near the border at Lobowitz, Frederick was intercepted by a large force under Field Marshal Maximilian Ulysses Browne, who had commanded Austria’s Silesia garrisons in the first invasion of 1740. In a foretaste of coming battles, Frederick found that Browne had positioned his army behind defensive terrain at a bend in the Elbe with his flanks anchored on mountains and marshes. While eventually yielding ground, Browne mauled the Prussian invaders and gave pause to their king. As one Prussian officer noted afterward, “Frederick did not come up against the same kind of Austrians he had beaten in four battles in a row…. He faced an army which during ten years of peace had attained a greater mastery of the arts of war.”65

In the campaigns that followed, Austrian forces deployed tools and techniques that equalized or negated many of the advantages the Prussians had become accustomed to enjoying in the previous war. The Habsburg infantry was steadier and better drilled, and did not break as easily when pressed. The Croat irregulars still harassed the Prussian flanks and supply lines in the old style, but in addition were now more numerous and better integrated into the Austrian battle order during pitched combat, inflicting casualties on advancing Prussian units before they could make contact with the main Austrian lines. Perhaps most noticeably, the Austrian artillery was more abundant, better handled, and technically superior to that of the Prussians. “Your Majesty himself is willing to concede,” one of Frederick’s lieutenants wrote to the king, “that the Austrian artillery is superior to ours, that their heavy guns are better served, and that they are more effective at long range—both from the quality of their powder and the weight of their charges.”66 As the late nineteenth-century German military writer Hans Delbrück, certainly no fan of the Austrians, later conceded,

The principal change in this arm—that is, the huge increase of heavy artillery—originated not with the Prussians but with the Austrians, who sought and found in these heavy guns their protection against the aggressive spirit of the Prussians. Frederick then reluctantly agreed with the necessity of following the Austrians along this path. At Mollwitz [in 1740] the Austrian Army had 19 cannon, one to every thousand men, while the Prussians had 53, or 2–1/2 for every thousand men. At Torgau [in 1760] the Austrians had 360 cannon, or 7 for every thousand men, and the Prussians had 276, or 6 per thousand men.67

Improved artillery tilted the advantage to the defensive, in Austria’s favor. Where Prussian offensive tactics required light, mobile guns that sacrificed range in order to keep pace with advancing units, Austria’s investments had gone in the opposite direction, developing heavier, longer-range pieces that could hit the Prussians’ main advantage—the infantry—at a greater distance than Prussian artillery could return fire. By placing large batteries of these heavier guns behind defensive terrain, the Austrians forced Frederick to fight on unfavorable terms in one encounter after another, subjecting his army to attrition on the battlefield while Austrian irregulars subjected it to logistical attrition off the battlefield. Frederick acknowledged the change in Austrian fighting capabilities, noting that his adversaries had become “masters of the defensive as a result of their campcraft, their march tactics, and their artillery fire.”68

Habsburg command and control had improved as well. In 1756, a new ministerial council was created to coordinate Austrian strategy in the conflict. This “war cabinet” operated in parallel with the Privy Conference and a third conference concerned with purely military matters.69 While these bodies inevitably had some degree of overlap, the creation of the war cabinet enhanced the monarchy’s ability to conceive and pursue a coherent grand strategy by combining in one place the components necessary for considering means and ends in all aspects of Habsburg power—military, diplomatic, and economic. The effect was heightened by the dominating presence of Kaunitz, who maintained close correspondence with Austria’s field commanders, and often intervened in military deliberations about when and where to offer battle.70

Reversals at the start of the war also prompted refinements in Habsburg planning at the operational level. In 1757, the foundation was laid for a professional General Staff, with a separate reporting structure from that of the civilian-dominated Hofkriegsrat.71 These changes, together with the improved education for military officers and heightened emphasis on maps and planning, had an unmistakable effect on the army’s performance in the field. Perhaps the highest praise came from Frederick himself, who commented positively on the altered behavior of Austrian generals and, in particular, their enhanced application of terrain-based defensive planning. “The changes in procedure of the Austrian generals,” he wrote, resulted in defensive positions with “flanks like a citadel, … protected from the front by swamps and impassible ground—in short, by every conceivable obstacle terrain could afford,” which made the act of attack “almost the same as storming a fortress.”72

KOLIN

Few officers in the Austrian Army better personified Habsburg military improvements than Count Daun, a subordinate to Lorraine who would later become senior commander of the Austrian forces in the war.73 An understudy of Field Marshal Traun, Daun had come of age in the army of Prince Eugene, under whom he had served at Peterwardin and, as one contemporary wrote, “learned the first rudiments of the art of war.” Drawn from the impoverished German nobility of Bohemia, Daun had a stolid and cerebral personality well matched to the culture of the Habsburg military, being “so conversant in maps … [that] there was not a village either in Germany, Hungary, [or] Bohemia … but he knew its longitude and latitude.”74 In the period between the wars, Daun had put these skills to good use as a member of the Military Reform Commission that had systematically studied the Austrian Army’s failures in an attempt to improve its future performance.

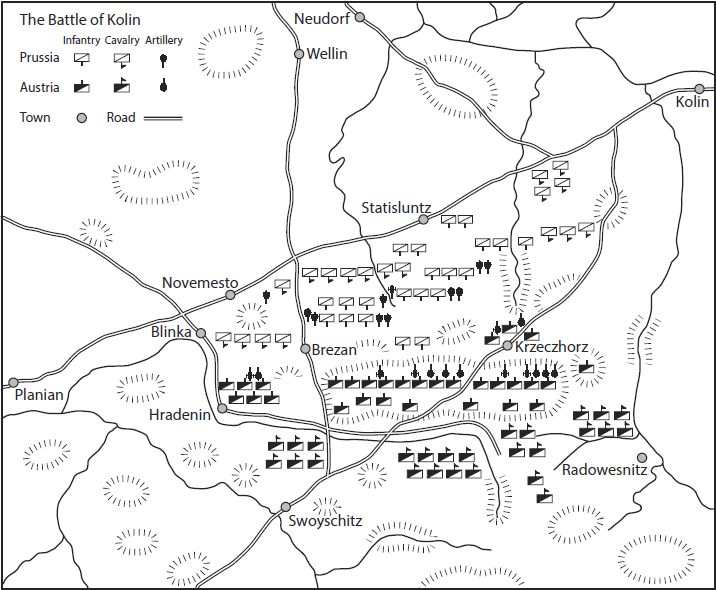

FIG. 6.4. Battle of Kolin, June 18, 1757. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

At Kolin in June 1757, Daun handed Frederick the first major defeat of his career.75 Unable to reach Lorraine’s main force at Prague, Daun collected Austrian remnants from the battle, amassing a force of forty-four thousand troops east of the city that forced Frederick to split his army and move out against him with thirty-two thousand. Like Browne at Lobowitz, Daun took up a strong defensive position that made maximum use of the local terrain. Placing his main force south of the village of Kolin, he anchored its rear and flanks on nearby rivers and forests (see figure 6.4). Advancing up the slopes at the Austrian lines, Frederick’s forces found themselves confronted by massed Austrian infantry and the concentrated fire of Daun’s entrenched artillery. Thrown into retreat, they were harrassed by large bodies of Croat infantry and hussars, and driven from the field.

So severe was Frederick’s loss at Kolin that he was forced to lift the siege of Prague, give up his invasion of Bohemia, and retreat back across the border. At this stage in the war, Austria was able to finally contemplate a major offensive campaign, pushing Prussian forces back into Saxony and Silesia with a view to moving the war onto Frederick’s home territory. At the same time, many of the fruits of Kaunitz’s earlier alliance diplomacy were beginning to materialize. In the north, Russian forces invaded East Prussia; in the west, a Reichsarmee composed of units from the smaller German states, which had unanimously declared war on Prussia earlier that year, linked up with French forces to threaten Frederick’s position in southern Germany.

It would be hard to imagine a fuller reversal of Austria’s earlier military fortunes or more dramatically different strategic state of affairs to that which had confronted the monarchy at an analogous point in the earlier succession war than in the months after Kolin. It was at this moment, when Prussian fortunes seemed at their nadir, that Frederick pulled off a string of stunning battlefield victories transforming the strategic situation to his advantage. At Rossbach in Saxony in November 1757, the Prussian king inflicted a crushing defeat on the Franco-German army, which outnumbered him two to one, effectively forcing France out of the war as an Austrian military ally. A month later at Leuthen, he decimated the main force that Lorraine and Daun had led into Silesia after the successful operations following Kolin, wiping out the gains of earlier Austrian victories and forcing a Habsburg retreat into Bohemia.

FABIUS AND HANNIBAL

After the catastrophe of Leuthen, Maria Theresa replaced Lorraine, who by now had suffered repeated defeats at Frederick’s hands, with the younger and more talented Daun. As the war progressed, however, Habsburg grand strategy was handicapped by a mismatch between the ends that Austria sought to accomplish and the means at its disposal. Even in its enhanced state, the Habsburg Army remained an essentially defensive tool being harnessed to a strategic objective—the reduction of Prussia—that was ultimately offensive. Austria could use its reformed armies to go beyond the mainly reactive “preservative” strategies of the previous war and frequently defeat Frederick in battle. But the makeup of its forces and mind-set of its top generals did not naturally lend themselves to carrying an aggressive war beyond Habsburg territory, into the Prussia heartland, on the scale that would be required for achieving Vienna’s full strategic aims of recovering Silesia and diminishing Prussia’s position in Germany.

This tension in Habsburg strategy became more apparent from 1758 onward, as Daun and Frederick maneuvered their armies along the monarchy’s northern frontiers. At Hochkirch in October, Daun defeated Frederick’s forces in a surprise attack that cost the Prussian king a third of his forces, several generals, and most of his artillery. After the battle, though, Daun refused to capitalize on his victory by pursuing Frederick, preferring instead to keep his army in place to recuperate its strength. Similar caution had prevented Austrian forces from reaping the full benefits of the victory at Kolin the previous year, followed by a daring but small hussar raid on Berlin that while psychologically satisfying, had done nothing to improve Austria’s overall strategic position. After Hochkirch, Kaunitz implored Daun to move boldly and seize the rest of Saxony in order to place Frederick at a disadvantage at the start of the following year’s campaigning season.76 Despite this pressure, Daun remained cautious, thus giving Frederick the breathing space to rebuild his forces over the winter.

Daun’s dilatory behavior was rooted in an inherently defensive philosophy of war pervasive among Habsburg commanders of the period. In words that Montecuccoli would have recognized, Daun believed that Austrian generals “should offer battle [only] when you find that the advantage you gain from victory will be greater, in proportion, than the damage you will sustain if you retreat or are beaten.”77 And elsewhere he wrote, “God knows that I am no coward, but I will never set my hand to anything which I judge impossible, or to the disadvantage of Your Majesty’s service.”78 Modeling himself on the Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus, who had hounded the stronger armies of Hannibal while avoiding battle, Daun believed that Austria’s chief advantages lay in terrain-based delay and denial. Rather than risking the army in head-on attacks against Frederick, he preferred to shadow the enemy and take up defensive positions that, if attacked, would place Prussian forces at a disadvantage.

Daun persisted in these methods despite intense pressure from the Hofkriegsrat. As a result, Frederick was able to remain active in the field and continue to wage war largely on his terms even after absorbing large losses in troops and resources. Repeated ideas and plans for offensive thrusts or moving against Berlin were rejected.79 While Daun would be subjected to criticism, the reality was that the Habsburg Army as an institution remained a defensive tool, with a cautious culture and conservative leadership that could not easily be brought to bolder uses. As Frederick had commented about himself many years earlier, “A Fabius can always turn into a Hannibal; but I do not believe that a Hannibal is capable of following the conduct of a Fabius.”80 Daun’s behavior showed that the opposite was also true: a Fabius such as himself could not so easily turn into a Hannibal, even when the political object of war demanded it. Even in victory, more often than not Austria’s commanders reverted to what they knew best: self-conservation through deliberation and maneuver.

The mismatch between Austrian means and ends was also visible in the diplomatic realm in Kaunitz’s attempts to corral and motivate an effective international coalition against Frederick. Defensive alliances are easier to organize and sustain than offensive ones. Where Austria had been successful in marshaling friends among the numerous states that felt threatened by Prussia’s growing power and ambition, it was a different matter entirely to hold this group together and keep its members focused on common strategic objectives through what turned out to be many years of bitter warfare marked by frequent defeats and setbacks.

Historically, Austrian efforts at managing groups of allies had usually involved the states of the German Reich, which were both smaller than the monarchy and bound to a certain extent to Austrian leadership by historical custom and established structures. In large wars, Austria was more often a subordinate and financial supplicant to another Great Power—usually England. In assuming the role of offensive alliance manager therefore, Austria, for all of Kaunitz’s immense talent, was attempting an enterprise in many ways beyond its means as a state. Austria lacked the financial heft to provide the subsidies that were essential to keeping allies in play through a long war, and lacked the offensive army to keep allies inspired by a vision of imminent victory. As with its military reforms, Austria’s ability to fully realize the advantages gained by its alliance formulations before the war was to a certain degree hobbled by its composition as a Great Power. In both the military and diplomatic realms, the monarchy’s geopolitical position necessitated the development of strategy for security and survival while placing natural limits on how far such strategies could be taken in practice.

CAGING FREDERICK

Even with these limitations, Austria’s army and allies eventually brought Frederick to heel. Converging Habsburg, Russian, and Swedish armies forced the Prussians onto the defensive in their own territory. While Frederick still retained much of the initiative through his characteristic daring and genius, the multidirectional pressures bearing down on his small kingdom effectively negated the strategic effects of even large Prussian victories. Unlike in the previous war, Austrian strategy succeeded in forcing Frederick to do less fighting on Austrian soil and more on his own. When in 1758 he had attempted to revert to his preferred strategy of predation on the Habsburg lands, the presence of active enemies on his flanks prevented a long stay; bogged down by the Habsburg fortress at Olmütz and with his supply columns hounded by Croats, he was forced to withdraw—this time, never to return. Within a year, Daun’s talented lieutenant, Ernst Gideon von Laudon, achieved the long-sought strategic convergence with the Russian Army at Kunersdorf in 1759, where the two empires combined forces to beat Frederick in a battle that almost destroyed the Prussian Army as a fighting force.

While the war continued on for a little more than three additional years, both Austria and Prussia were materially exhausted. By 1763, the military situation in central Europe was at a virtual stalemate, with Prussia in possession of the northern portions of Saxony and Silesia, and Austria holding the south, including the Saxon capital of Dresden and Silesian county of Glatz, the latter forming a small but crucial toehold in the lands lost to Frederick. The concluding Treaty of Hubertusburg, signed in February 1763 by Austria, Prussia, and Saxony, largely reinstated the status quo ante bellum. Under the treaty, a more or less even swap was agreed on: Prussia gave up Saxony and Austria gave up Glatz.

Assessed according to Maria Theresa’s central aim—regaining Silesia—the war must be judged a failure. But as an installment in the wider contest with Frederick that had begun in 1740, the balance sheet of Austrian grand strategy is more positive. Seen in this light, Austria’s overarching need was to stabilize its position as a central European power broadly and put a stop specifically to the periodic Frederickian bursts of predatory revisionism targeting the Habsburg lands. In this goal, Maria Theresa largely succeeded. Her reformed armies not only fought the theretofore-undefeated Prussian “monster” to a standstill but together with Kaunitz’s alliances, drained the lifeblood of his kingdom. While Silesia was lost for good, the loss of Saxony, a crucial and indeed the only northern Habsburg buffer state whose absorption by Prussia would have converted Frederick’s kingdom into a more formidable state, thereby holding profoundly negative long-term implications for Austria’s security, was prevented.

As important, Austria emerged from the conflict with its prestige as a Great Power restored. Within the European balance of power, Austria had restored its status as a powerful and permanent player capable of assembling coalitions to safeguard continental stability. In Germany, Frederick reaffirmed Prussia’s status as a vassal to the Habsburg emperors—a symbolic but nevertheless significant concession for shoring up Habsburg influence in Germany. Compared to Austria’s desperate circumstances in 1740, at the start of Frederick’s ravaging reign, its situation in 1763 could not have been more different. The turnaround in the monarchy’s fortunes was the result of the determined efforts that Maria Theresa and her subordinates—above all, Kaunitz—had made to fully organize and leverage Austria’s capabilities as a Great Power, and harness them to a set of political objectives for the renewed security of the state—in short, because they had pursued an effective grand strategy.

Preventive Strategies: Forts, Rivers, and Deterrence (1764–79)

After the Seven Years’ War, Austria’s rulers again turned their attention to contemplations of future strategy. Twenty-three years of almost-continuous warfare had taken a toll on the monarchy. The latest installment alone had cost more than three hundred thousand Austrian casualties, the state was burdened by heavy debts, and large swaths of the northern countryside were still recovering from years of occupation, pillage, and depleted labor at harvest time. The question facing Austria’s leaders was how to avoid all this happening again.

The man who would grapple with this question more than any other was Joseph II, Holy Roman emperor and coregent alongside his mother, Maria Theresa, in 1765, and sole monarch from 1780 on.81 Joseph was a creature of the Prussian wars. Maria Theresa had been pregnant with him while she practiced horse riding ahead of her trip to the Hungarian Diet at the start of the first Silesian War. Raised amid the turmoil of constant invasion, Joseph took an interest in military affairs from a young age and was enamored with Frederick. Like the Prussian king, he was an absolutist monarch committed to building a strong central state grounded in toleration and enlightened administration. Intelligent and impulsive, he chafed at his mother’s baroque religiosity and continuing control in matters of state.

Joseph believed that Habsburg security could be put on a stronger longterm footing by applying the tools of reason: logic, deliberation, and planning. He took long rides across the monarchy’s frontiers, accompanied by his generals, examining every detail of topography. In the north, Joseph visited the battlefields of the recent wars with Frederick, and devoted close study to the hills and rivers of northern Bohemia that with Silesia gone, now made up the northern frontier. In Vienna, he composed countless memorandums and commissions to debate the question of how the frontier should be secured against yet another Prussian invasion.

Joseph’s collaborator in these exercises was Field Marshal Count Franz Moritz von Lacy (1725–1801), a talented protégé of Field Marshal Daun who served as the first head of the Austrian General Staff and president of the Hofkriegsrat in the years after Daun’s death. The central lesson that both Joseph and Lacy took from the Prussian wars was that a lack of preparation not only made Austria’s defense more difficult but also invited such attacks to begin with. These wars, Joseph wrote, “proved quite clearly the necessity of preparing sound arrangements for the future.”82 One important ingredient in being better prepared was the deployment of a larger standing army. Maria Theresa’s expansion of the military between the wars had helped to shorten Frederick’s campaigns in Bohemia and prevent the loss of new territory. “During the previous campaign,” a report by senior generals after the war argued, “it became clear that unless we maintain equally large bodies of troops at the border to what the enemy is able to deploy, the enemy can come and go without hindrance.”83

To deal with the Prussian threat in the future, Austria’s generals estimated they would need 140,000 troops—three times more than on the Turkish frontier, and not counting whatever troops would be needed in Italy, Germany, and Galicia. One report stated,

The situation in Bohemia and Moravia requires that the King of Prussia be opposed by no fewer than his own numbers, meaning 130 to 140,000 men at any time. Against the Turks, at least 40 to 50,000 troops will need to be stationed in the Banat and positioned around the Danube…. In order to ensure just the minimum of defense against both sides, the War-President thus recommends at least 200,000 men to be kept in the field…. [But] one ought to then consider the aforementioned restrictions in the case of a two-front war which would require a force of 310,000 men, including garrisons.84

Meeting these demands on a standing basis would not be easy. At the time the estimates were produced, Austrian forces in the north already fell short of the desired number by sixty thousand men. Filling the gap would be expensive. Already in 1763, the military budget had been raised to seventeen million florins, and an additional five million was sought.85 Joseph was an advocate of both a larger force and larger budget, but also understood the financial burdens that these preparations would bring. “We must try always to combine the necessary security with the country’s welfare,” he wrote to his brother, “and ensure that the former protects the latter as cheaply as possible.”86

Even if it could afford a larger army, that alone would not buy security against Prussia. Larger forces in 1756 had not deterred Frederick’s invasion, which had only been ejected with difficulty. Once deployed to the north, Austria’s field armies had to worry about guarding multiple invasion routes while keeping an eye on other frontiers. As Maria Theresa observed,

[Frederick] has the advantage of interior lines, while we need to cover double the distance to get into position. He owns forts, which we lack. We have to protect very large areas and are exposed to all manner of invasions and insurrections…. One knows the Prussian machinations … that he leaves no means untried to rush us and fall upon our necks.87

With Silesia in Prussian hands, an invading force could enter through mountain passes from more than one direction, forcing Austrian commanders to parcel out their strength, as one general put it, without “the faintest idea of Prussian intentions.”88 Recent experience had shown that this could all happen at short notice, and by the time the army reacted, Frederick was already on the path to Vienna. Once lodged in Bohemia, he could linger while the army chased him, feeding his forces on Austria’s fattest provinces; as Maria Theresa put it, “This monster stretches out his campaigns … until everything is sorted and saved.”89

THE ELBE FORTRESSES

To deter future Prussian invasions, Joseph and Lacy envisioned the construction of a series of fortresses across the northern half of Bohemia. “As a principle,” Lacy explained, “fortifications are absolutely necessary for security of the country.”90 The absence of such defenses was believed to have encouraged Frederick’s attacks, while forcing the army to “rely upon the establishment of rearward strongholds and magazines, which make the transport of supplies difficult, costly, and burdensome for the country.”91 As long as no such fortifications existed, Joseph and Lacy believed, Frederick would not be deterred from attacking. As Lacy worried in 1767, “Given that we did not commence construction [of forts] immediately after our most recent war, the King of Prussia [may not] wait for completion of such a project, [but rather] act on his aggressive intent before being faced with a new bulwark.”92

The potential for well-sited fortresses to strengthen Bohemia’s defenses had been demonstrated by the ease with which the entrenched camp at Olmütz had thwarted Frederick’s last attempted invasion in 1758. Local terrain, too, favored such fixed defenses. As Daun and Lacy had found in recent campaigns, the shape of the Elbe River, with its numerous elbows and tributaries, was ideal for protecting the flanks of a prepared defensive position. The river’s course just south of the base of the mountains, set back somewhat from the main ingresses, allowed a defender located at its center to quickly pivot eastward or westward, and thus cover a broad section of frontier.