FIG. 7.1. Western Frontier of the Habsburg Empire. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

Teufelfranzosen

FRANCE AND THE WESTERN FRONTIER

If we weigh the comparative strengths of Austria and France, we find on the one hand a population of 25 million, of which about half is paralyzed by differing constitutions and, on the other, a France with unhindered access to 40 million, over which it has imposed an iron conscription law … that knows no exemptions—a system, in short, of the kind that Your Majesty would never be able to implement in our lands.

—ARCHDUKE CHARLES

Only one escape is left to us: to conserve our strength for better days, to work for our preservation with gentler means—and not to look back.

—METTERNICH

ALONG ITS WESTERN FRONTIERS, the Habsburg dynasty was locked for most of its existence in an unequal contest with the military superstate of France. More advanced than the Ottomans and bigger than Prussia, France was capable of fielding large modern armies and elaborate alliances to threaten the Erblände from multiple sides. In conflicts with France, Austria was not able to count on the military-technological advantage that it enjoyed against the Turks, or the greater size and resources that gave it an edge against Prussia. Instead, Austria learned over time to contain French power through the defensive use of space, building extensive buffer zones to offset France’s advantages in offensive capabilities. Habsburg strategy on the western frontier evolved through three phases. In wars with the Bourbon kings, successive Habsburg monarchs cultivated the smaller states of the German Reich and northern Italy as clients, committed to sharing the burden of defense through local armies and tutelary fortresses in wartime. Against Napoleon, these buffers collapsed, forcing Austria to use strategies of delay and accommodation similar to those employed against Frederick II to wear down and outlast a stronger military opponent. And in the peace that followed, Austria restored and expanded its traditional western security system, using confederated buffers and frontier fortresses to deter renewed French revisionism.

Playground of Empires

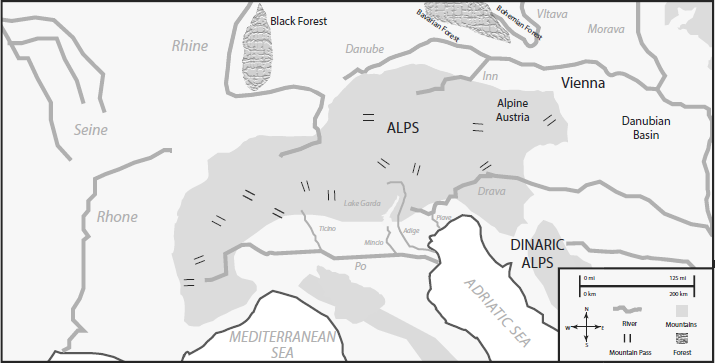

The western frontier of the Habsburg Monarchy ran across the middle mass of the European continent from the English Channel to the Mediterranean (see figure 7.1). At its epicenter lay the lands directly above and below the Alps, including the states of southern Germany and northern Italy that had formed the ancient heartland of Charlemagne’s empire. Despite their separation by mountains, these territories represented a more or less contiguous zone of agriculturally fertile, mineral-rich provinces capable of sustaining high population densities, tax revenue, and the early development of industry. From the Middle Ages on, the states of this region had shared the characteristic of political fragmentation, forming weakly organized clusters of small polities that were susceptible to domination and influence by outside powers.

The central location and political tractability of these lands endowed them with great geopolitical importance for neighboring Great Powers. By the fourteenth century, an intense competition had formed over control of them between the Habsburgs and the Capetian dynasty of France, with its Valois and Bourbon branches, that would persist for almost five centuries. Both dynasties sought to impose some degree of primacy over the weak polities of Germany and Italy, but in any event to prevent them from falling under the other’s sway. The stakes for both empires were high. A France that could expand beyond the Rhine was capable of dominating Europe; one that could not face the prospect of confinement in the continent’s westernmost corner and remaining perpetually on the defensive against the combined strength of Germany. An Austria that could retain a deciding influence over Germany and Italy could add depth and wealth to its small Alpine core; one that could not be reduced to the status of a marginal power and sequestered to Europe’s eastern rim.

FIG. 7.1. Western Frontier of the Habsburg Empire. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

A Different Kind of Enemy

In this high-stakes competition, Austria faced a rival that was qualitatively different from its other competitors. France developed the resources and military-technological tools of a Great Power earlier than any Western state.1 Its kings achieved early mastery over the nobility, building a centralized military state that was backed by the resources of a large, defensible, and well-proportioned landmass rich in natural wealth. To this was added a culturally and linguistically homogeneous population that numbered twenty million by 1700—larger than any other European power including Russia.2 Drawing on these resources, France could assemble large, advanced armies, supported by an ample treasury and the latest Western warfare methods. Despite possessing a comparable landmass, Austria was usually unable to compete with France on equal military terms.3

One French advantage was geography. Located at the westernmost tip of the European peninsula, it was flanked by the sea on three sides and screened by mountains across its landward frontier. Combined with its numerous population, these physical traits presented a secure geopolitical base that gave France a natural offensive orientation in its behavior. As a nineteenth-century Austrian military appraisal put it,

Bounded by oceans to its West and to its North…. [France] has but one defensive line and one direction of war. [It has] a coherent national identity—characteristics shared by no other major power, except Russia. This alone gives her position advantageous for war and lessens the pains of any potential defeat or setback. It is impossible to imagine breaking up France, even if it were defeated in an attempt to destroy and divide the rest of Europe.4

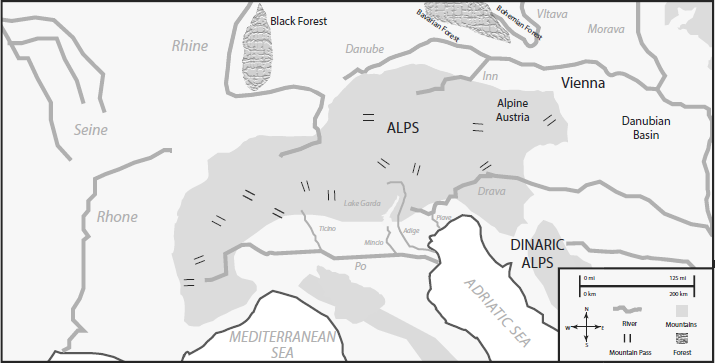

These characteristics represented a significant advantage in strategic competition. In wars with Austria, France’s geography was conducive to launching two-pronged offensives into the Danube River Basin. France benefited from the topographic arrangement of the Alps, whose east-west spine enabled an invader approaching from the west to enter the Erblände along two separate avenues while screening a substantial portion of its own forces—and ultimate intentions. Europe’s rivers amplified this effect (see figure 7.2). North of the Alps, the Rhine Valley’s near intersection with the Danube allowed for the swift eastward movement of troops from the French interior and supplies directly into the Habsburg heartland. As Venturini wrote of this section of frontier,

FIG. 7.2. French Invasions of Austria, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

The long border is throughout only beneficial for the French…. The assertion of mountains … [means that] the French always have free rein there, a safe Rhine crossing, and the most commodious positions to attack the Austrian front on the right flank. They have the same advantages on the Upper Rhine through the formation of their power in Switzerland. Thus, the Austrian Army is in the highly disadvantageous position of defending a completely surrounded unfortified border against a strong enemy, operating from an extremely strong eccentric base.5

To the south, France’s Rhone River has a similar effect, aiding movement to the headwaters of Italy’s River Po Valley, down which armies could march through fertile plains to the thirty-mile-wide “Ljubljana Gap” through the Karawanken Alps of modern-day Slovenia and an open road to Vienna.6 These two paths—one through Germany and the other through Italy—created a Rhine-Po dilemma for Austria in the west, enabling invaders to approach on a dual axis in the assurance that defenders would not know until late in the game where their main blow would fall, by which point it would be too late to quickly shift forces from one front to the other.

Another French strength was alliances. As a state that combined the attributes of a maritime and continental power, France needed allies to support prolonged landward advances. An old dynasty, the Valois and their offshoots were skilled in collecting clients and advancing succession-based claims that formed the template for expansion until the late eighteenth century. Partly through this tradition, France developed a sophisticated diplomatic culture that treated alliances as an integral component of security policy. In the west, France’s famous Pactes de Familie effectively sealed off its southern frontier and enlisted Spain as a virtual proxy in contests on the European mainland. In Germany, France cultivated those German states that chafed at Habsburg dominion, particularly Bavaria, but occasionally Brandenburg and Saxony. Further east, it organized military alliances with second-rank states located on the opposite side of its rivals—so-called alliances de revers. As early as the eighth century, the Carolingian kings had used such formulas to court the Abbasid Caliphate to harass the flanks of the Byzantine Empire. In the sixteenth century, it formed alliances with the still-extant kingdoms of Poland and Hungary, the latter of which would persist through patronage to renegade Magyar princes and offer France a ready base of opposition to the Habsburgs inside their own borders. Similar alliances would be nurtured with Sweden, Saxony-Poland, and the Ottoman Empire as counters to Russian expansion and tourniquets to Austria well into the eighteenth century.

France’s combination of large armies, favorable geography, and alliances set it apart from other Habsburg rivals. Where the Ottomans often had numerical superiority and the Prussians frequently possessed a technological-tactical edge, France had both. Its facility with alliances differentiated it both from the Ottomans, who rarely attempted to coordinate with Western powers, and Prussia, which until Bismarck showed only a marginal aptitude for sustaining alliances. Where both the Ottoman Empire and Prussia had to use great exertions of diplomacy to trigger crises in theaters other than their own, France could pose threats to two separate frontiers merely by virtue of its geographic location. Together, these military, diplomatic, and geographic factors made it a full-spectrum peer competitor whose advantages were rendered all the more lethal by the fractious, harried, and resource-constrained state in which the Habsburg Monarchy usually found itself.

Building Blocks of Western Strategy

To understand the strategies that Austria developed to deal with the French threat, it is first necessary to understand what it could not do. The Bourbon wars made it plain that the monarchy could not dominate France militarily. Nor did it have the option of absorbing all or most of the territories to its west, as a more powerful empire might have attempted. France’s alacrity as an offensive land power along with the high strategic-economic value of the German and Italian lands meant that Austria could not depend on a few fortresses and low-intensity border defenses of the kind it was able to employ across the barren expanses of the southeast. And while periods of détente and even alliance might be possible, conflicts between the two states often involved fundamental misalignments of strategic interest, foreclosing the option of a prolonged condominium of the kind that Austria developed with Russia.

Despite these limitations, Austria did possess certain advantages that over time would provide the building blocks for an effective strategy to counter French strength. Unlike on its northern or southern frontiers, Austria’s western approaches were populated by scores of smaller and weaker states. Over previous centuries, the Habsburgs had amassed considerable influence over these states in their status as Holy Roman emperors. The Reich itself was not a powerful offensive military tool; as noted in chapter 6, by the eighteenth century it was a shadow of its former medieval glory. The Reich’s influence in Italy was weak, with the region north of the Papal States existing under the nominal jurisdiction at best of the emperor.

Nevertheless, the Habsburgs’ status in both sets of lands, seemingly irrelevant in hard-power terms, conveyed a moral authority and sets of levers for political influence among the small states of middle Europe that the Bourbon kings, for all their military strength, could not match.7 This status provided a seemingly symbolic yet decisive edge in the battle for political influence among the smaller states of central Europe. Building on this foundation, the Habsburgs constructed a security system that by the early decades of the eighteenth century would consist of three interrelated pillars: a protective belt of buffer states, a network of fortresses, and antihegemonic coalitions.

WESTERN BUFFERS: THE REICHSBARRIERE

At the heart of Habsburg strategy in the west was the concept, initially inchoate but increasingly formal with the passage of time, of a series of obstacles—political, military, and spatial—to block eastward French expansion and organize the intervening territories under a Habsburg aegis. The overarching aim was to create a defensive bulwark, or Reichsbarriere as the Austrians called it, across the length of the western Habsburg frontier, from Switzerland to the English Channel. In the north this barrier was anchored on the Austrian Netherlands, which acted as a point d’appui for Austrian armies to threaten France in the rear, and in the south on the Alps, which provided a natural wall below the Rhine Valley.8 Between these points, the Habsburgs organized a line of buffer states, under the auspices of the Reich, which continued in a more loosely organized format into the territories of northern Italy.

In engineering a Habsburg tilt among the states of this line, the Habsburgs enjoyed two advantages. One was fear. While German states were nominal vassals to the Habsburg throne, by the end of the Thirty Years’ War this was no longer a sufficient force to congeal them into an anti-French bloc. What could unite them behind a common strategic purpose, at least for short periods, was the threat of attack by an outside, non-Germanic power. The acquisitive militarism of the French state under the Bourbon kings presented such a threat, made all the more adhesive by Louis XIV’s habit of targeting weaker states for coercion.

Successive Habsburg monarchs harnessed German fears of the Bourbons to Austrian strategic needs, renovating the old collective defense mechanisms of the Reich for use against outside aggressors for the first time since before the Reformation.9 They focused in particular on organizing defensive clusters among the small states that lined France’s frontiers and principal invasion routes. In 1702, Leopold I worked with the princes of the Reich’s most exposed members to form the Nördlingen Association, a subgrouping of states whose purpose was to defend against attack from the west (see table 7.1).10 Within the Reich, the Nördlingen states helped to counterbalance opposition from northern or pro-French states to ensure the passage of a Reichskrieg—the equivalent of Article 5 in NATO—while lending credibility to Austria as a security patron in the eyes of its larger external allies.11 Once war was declared, the group provided a mechanism for pooling defense resources well above the Reich average, often committing troops at triple the strength required by the diet while less exposed.

Similar though less formalized dynamics existed in Italy. Long a Habsburg stronghold, Italy’s position in the wider Austrian orbit was reaffirmed in the Spanish succession war, with portions of Lombardy, including the duchies of Mantua and Milan, coming into Austrian possession in 1711. Between these territories and the Erblände sat Venetia, through which Austria brokered rights of passage for troops and supplies via the Brenner Pass in wartime. To the west lay the kingdom of Sardinia, an independent polity with a history of vassalage to Spain that shared the Nördlingen states’ proximity to and therefore fear of stronger powers immediately beyond its borders. Straddling the mountains, Sardinia looked with apprehension on the expansion of Bourbon strength.12 As in Germany, this anxiety provided an opening for Austria to cultivate close security links, and eventually, a glacis to French or Spanish reentry into the peninsula.

TABLE 7.1. The Nördlingen Association’s Military Manpower, circa 1702

Kreis |

Contingent |

Franconia |

8,000 |

Swabia |

10,800 |

Upper Rhine |

3,000 |

Electoral Rhine |

6,500 |

Austria |

16,000 |

Westphalia |

9,180 |

Total |

53,480 |

Sources: Lünig, ed., Corpus iuris militaris, 1:402–7; Hoffmann, ed., Quellen zum Verfassungsorganismus, 269–71.

Another factor that aided the Habsburg Monarchy’s efforts to build a western buffer system, paradoxically, was its own weakness. Where early eighteenth-century France appeared strong and predatory to Europe’s smaller states, Austria was already by this point widely seen as being unable to mount the attempts at continental primacy that it had attempted in its heyday of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Capable of undertaking significant military efforts, it nevertheless posed no threat of hegemony. Indeed, its primary goal as an ancient, weak power was a stable territorial status quo. This aligned well with small states’ interests in self-preservation. Not surprisingly, Austria’s greatest base of support in the western buffers were those states that had the most to lose from revisionism: in Germany, the smaller principalities and archbishoprics—Salzburg, Passau, the imperial knights, and southern free cities; and in Italy, the small states of Lombardy and Sardinian satellite, which preferred a distant Viennese paternalism to centralized Bourbon rule.13 In both sets of territories, a basic bargain presented itself: small-state fealty and contributions to collective defense in exchange for benign Habsburg domination and protection.

The Habsburgs actively promoted this bargain, using the largesse of the emperor’s office—jobs in the imperial administration, bribes, and other favors—to reward loyal princes and punish disloyalty. At the same time, the Reich machinery limited imperial power through various checks and balances, including an electoral college that ratified major decisions and a diet that decided on declarations of Reichskrieg and, ultimately, electoral confirmation of new emperors. However formulaic, these rule sets helped to make Austrian hegemony more palatable to client states by wrapping it in the arcana of rules and procedures.

Habsburg monarchs were conscious of the strength that came from restraint in such a setting, and often cultivated a reputation for moderation in victory and leniency in dealings with wayward princes. An example, as we have seen, was Maria Theresa’s extension of generous terms to the Bavarian Füssens in 1745. Such magnanimity could be alternated with acts of brutality. But ultimately, Habsburg rule was built on the foundation of a soft hegemony. This stemmed not from altruism but rather necessity; attempting a more coercive approach would simply not have worked given the often-tentative state of Habsburg military and financial power. In showing well-timed mercy, the dynasty was most likely to cultivate a voluntary willingness of states to remain loyal in future crises.

These measures did not make either Germany or Italy into uniformly pro-Habsburg domains. By definition, the nature of a buffer zone is that the states therein do not fall under the exclusive sway of either flanking power. Midsize members of the Reich frequently chafed at Habsburg dominance as a barrier to their own territorial growth and influence. Most notably, as we have seen, there was Bavaria, which in addition to bearing traces of the old Wittelsbach-Habsburg rivalry, was encircled by Habsburg possessions or allies, and therefore felt as much a menace from Austria as Sardinia or the Nördlingen states felt from France. Noting this dynamic, Eugene said of the Bavarians, “Geography prevented them from being men of honor.”14 Saxony too, while more consistently in the Habsburg orbit, often oscillated between Austria and its enemies. France encouraged these dynamics—in Italy, by playing Sardinian court politics and stoking discontent in Lombardy; and in Germany, by impeding efforts at a unified Reich military policy and fanning opposition to the emperor.15 In both regions, Versailles dispensed bribes on a stupendous scale and exploited local factionalism. Above all it sought to nurture rival claimants to the imperial title, either by building German support for a Bourbon candidacy or backing that of a lesser German house hostile to the Habsburgs.

French efforts notwithstanding, armed opposition by the German princes to the Habsburgs was the exception rather than the rule. While French money could always find a fissure to exploit, more frequently than not, intrabuffer tensions were kept within bounds, taking the form of simmering discord rather than active revisionism. This was in part due to the fact that even the Habsburgs’ German rivals derived a benefit from its weak hegemony, which was bearable, and in any event, usually preferable to a new and unknown foreign ascendancy. The Reich’s rickety rule-making structures further channeled these currents into constitutional cul-de-sacs that tended to support continuation of the status quo. While Bavarian and certainly Prussian opposition could be formidable at times, the structures of the Reich gave Austrian diplomats options for managing these dynamics that they otherwise would have lacked. Even at the high point of its power, France never succeeded in building a permanent fifth column in Reich politics, and was only able to pull Sardinia fully into its sphere after the emergence of nationalist aspirations in the mid-nineteenth century.16

TUTELARY FORTRESSES

Habsburg success in organizing buffer regions enabled Austria to do something Great Powers are rarely able to do in such spaces: maintain a military presence on the territory of intermediary states. The Bourbon wars demonstrated the utility that forward force deployments, and particularly fortresses, could have in both Germany and Italy. In the Spanish succession war, France employed the Lines of Brabant, a 130-mile-long network of strongholds and entrenchments from Antwerp to Meuse, to slow the advance of allied forces under the command of John Churchill, First Duke of Marlborough (1650–1722) in the Low Countries. By contrast, Austria’s fortifications in the west were initially meager, prompting Eugene to complain about the absence of even an “entrenched camp” here and make repeated pleas to build forts in the west “to form a barrier against France, which might deter her from attacking us.”17

Through the Reich, however, Austria had access to the fortresses of fellow German states. Such defenses, particularly those along the Rhine that sat near the embarkation points of French armies, had proven effective at arresting the progress of French offensives early in their advance. Closer to Austria’s borders, Ludwig of Baden’s Stollhofen Line, while bypassed, fired imaginations about the potential for more fully developed defensive positions to block the gap between the Black Forest and Rhine that formed the favored entry point for French armies into Austria.18 The rapid French reduction of Ulm, Regensburg, Menningen, and Neuburg, and subsequent enemy advance into the Tyrol, illustrated the dangers that could materialize for Austria when this crucial route through southern Germany was unhindered.19

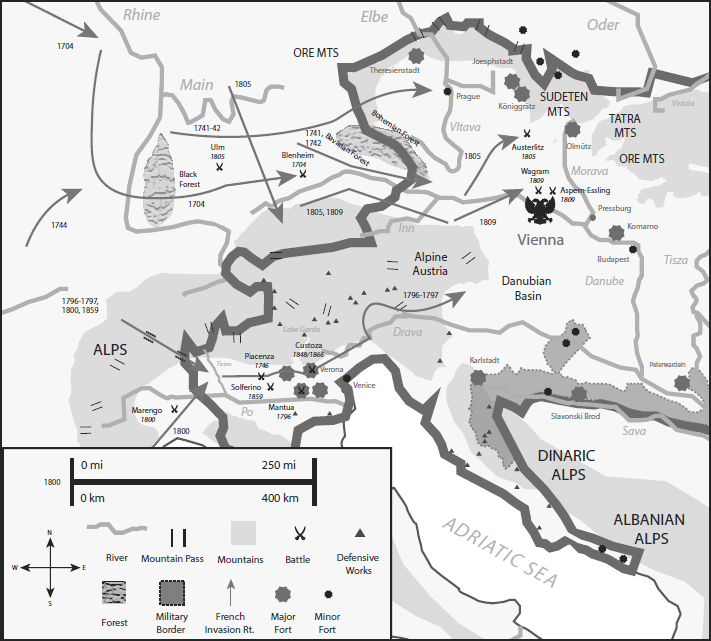

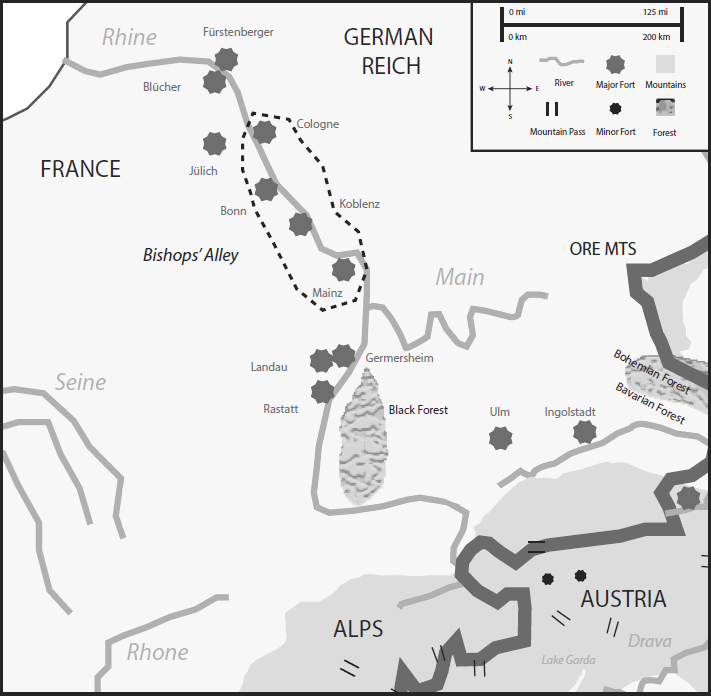

Through the use of Reich forts during the Bourbon wars, the Habsburg Army gradually developed a concept of western security in which the ability to place force beyond Austria’s borders, on the soil of acquired territories or friendly states, was seen as the key to the defense of the Erblände. Under the terms of a Reichskrieg, Austrian armies could transverse and operate from friendly Reich territory. When war was on the horizon, Vienna often negotiated terms with individual states allowing for sustained deployments or shared garrisoning of strategically important points on their territory. In Germany, these included the fortresses of Mannheim and Philipsburg on the Middle Rhine; Mainz, Coblenz, Bonn, and Cologne (the so-called Bishop’s Alley) on the Lower Rhine; and Kehl, Villingen, Freudenstadt, Heidelberg, Mannheim, Frankenthal, and Freiburg on the Danube (see figure 7.3).20

FIG. 7.3. The Rhineland Fortresses. Source: Center for European Policy Analysis, 2017.

Similarly, Austria had access to numerous frontier fortresses in Italy. Victory in the Spanish succession war brought possession of Fuentes, located near the mouth of the Adda; Pizzighettone, near Lake Garda; and the swamp fortress of Mantua guarding the Tyrolean passes.21 Security arrangements with Venetia provided access to Peschiera, an island fortress at the intersection of the Mincio and Lake Garda, and to the west, the alliance with Sardinia informally incorporated the fortress at Turin and numerous smaller sites lining the Alpine passes.

While the main purpose of Habsburg buffer forts was defensive, their presence also expanded offensive options in wartime. Using the Rhine forts, Habsburg and Reich armies could converge on the Mosel Valley, the point of the French frontier with the fewest obstacles to Paris. Especially notable in this regard were the forts of Bishop’s Alley and the strongholds at Mannheim and Philipsburg.22 Used in conjunction with the Austrian Netherlands and Habsburg positions in Italy, these fortress networks provided a means of projecting power along the full length of the French frontier and achieving concentration early in a conflict.

Once an invader got beyond the intervening spaces of the Reich, an effective defense was harder to mount. As the Allied armies would find in World War II, the physical orientation of the Rhine tributaries tends to speed invading armies while complicating internal coordination between defending forces.23 Using these rivers and picking off Reich members en route, a French invasion could penetrate southern Germany and swiftly reach Austrian soil. This reality intertwined the strategic fate of the Habsburg home territories with the territory of neighboring states, amplifying the importance of developing forward infrastructure on sites that were both militarily defensible and politically reliable.

ANTIHEGEMONIC COALITIONS

The same weakness that made Austria a tolerable patron to Europe’s middle states aided its efforts to recruit Great Power allies against France. From the perspective of Europe’s larger states, a France that was strong enough to break into the Netherlands and expand east of the Rhine and Alps was a France that would be hard to materially counterbalance on a long-term basis. The Habsburg Monarchy offered a force sufficiently strong to check this expansion without threatening to replace France as a danger to the European balance of power. In the east, Austria was an insurance policy against Ottoman decay devolving into vacuums that would invite predation by neighboring states. In the west, its client states and position in the Low Countries made it a natural barrier to French expansion on both a north-south and east-west axis.

In this combination of vulnerability and indispensability lay part of the origins of Austria’s role as a geopolitical “necessity”—the “hinge upon which the fate of Europe must depend,” as the British diplomat Castlereagh would later say.24 In the age-old geopolitical pattern whereby large status quo powers support weaker states to guard against the rise of new hegemons, Austria was a hybrid, possessing the attributes of a Great Power, but through its internal complexities and exposed geography, the security dilemmas of a smaller state.

As an ally, Austria possessed certain attributes that stronger powers needed to manage the continent. One was location. Britain’s wealth and naval power allowed it to provide subsidies, blockades, and small expeditionary forces, but it needed Austria as an onshore organizer of land armies. Russia was rich in military manpower yet distant from contests with western rivals, which unless impeded by Austria, would have the strength to contemplate eastward expansion. Another Habsburg strength, mentioned above, was legitimacy. Going back to the sixteenth century, Austrian diplomacy had developed a culture of playing to the dynasty’s status as a bulwark against the Turks to enlist the help of other European states. After the Treaty of Westphalia, the Habsburgs built on this tradition, positioning themselves as the defender of the sanctity of European treaties. Invoking legitimacy, the monarchy became the guardian of treaty-based rights in the European states system. In the context of French military expansion, this positioned Austria to attract the patronage of other status quo–minded powers that stood to lose from force-based revisionism.

WESTERN TIME MANAGEMENT

The elements in Austria’s western defenses worked together to give it greater control over sequencing in western conflicts. Buffer systems stalled invaders and won time to organize forces and recruit allies. Fortresses toughened middle-state terrain and ameliorated the Rhine-Po dilemma by enabling small forces on either side of the Alps to hold out until field armies could be shifted to the critical front. Allies heightened the effect by pressuring France’s rearward approaches and providing relief armies to campaign on the Lower Rhine and Mosel—the points at which France was most vulnerable and the logistical reach of Austrian armies was most constrained. This in turn enabled Austria to safely deprioritize the front in Germany in the assurance that Reich armies (which faced jurisdictional obstacles to operating south of the Alps) and western allies could cover the north while it focused its own forces elsewhere. These various props allowed the monarchy to adopt an essentially “radial” approach to western crises, stripping to the bone Austrian deployments in the Rhine theater and concentrating troops elsewhere—sometimes in Hungary, but usually in Italy, where the richest territories were most likely to be won by Vienna in the war.25

This approach to managing the west could fail. In the War of the Polish Succession, Austria was shorn of support from England and Holland, and lost ground in Italy. In the War of the Austrian Succession, the Reich failed to rally, and allied help was weaker than in the Spanish succession war, forcing Austria to bear the brunt of multiple fronts on its own. Support from the maritime powers tended to focus on the Austrian Netherlands, but resist Habsburg expenditures of subsidies or effort on Hungary. Russian aid too, as we have seen, could be slow to materialize and often came at the cost of a pound of flesh in the east. Yet by and large, the system held, partly through Austrian diplomacy, but mainly because Europe’s powers had few options but to sustain a central wedge to limit the growth of French strength, and Austria was the only game in town. From the beginning of Louis XIV’s reign until the rise of Frederick the Great, Austria fought five wars against France, in all of which it was on the side with a greater number of allies, and in all but one of which it arguably came out on the better side of the ledger. In this period, Austria’s western toolbox enabled it to offset most of France’s offensive power advantages at a financial and human cost that was manageable for itself.

System Collapse: The Napoleonic Wars

As we saw in a previous chapter, the emergence of Prussia brought a coda to Austro-French rivalry in the middle decades of the eighteenth century, providing the basis for Kaunitz’s successful courtship of Versailles. This interlude was shattered in 1789 with the outbreak of the French Revolution. Its aftermath marked the reactivation of France as a predatory power, igniting wars in which France would resume the multiaxis military expansion it had begun under Louis XIV.

In their first encounters with the new republic, the Austrians sought to use traditional methods to contain the threat. As in the past, Vienna rallied its buffer allies, mustering imperial forces and deploying the army to advanced posts on client state territory. It also enlisted extraregional allies, showing dexterity in the resumption of alliance ties with Britain after decades of lapse, and converting erstwhile enemy Prussia into a partner in a move as bold as Kaunitz’s early French and Ottoman flips. As the diplomatic wheels turned to align the bulk of Europe in Austria’s corner, the army prepared for an offensive use of Reich fortresses in a plan of operations that would have been recognizable to Eugene, amassing forces in forward positions at Coblenz for a concentric push from the Austrian Netherlands and Lower Rhine.

In the war that followed, Austria’s plan and the century-old security system it embodied failed catastrophically. Ejecting allied armies from its frontiers, France invaded Austria’s German and Italian buffers, imposing a peace at Campo Formio under which the monarchy ceded Belgium and lost control of large sections of northern Italy and the Rhineland.

The scale of Austria’s defeat showed that the new French Republic was a more formidable threat than the Bourbons had been. Most noticeably, it was capable of generating larger armies. While France had always been able to sustain sizable forces, the republic’s practice of placing all unmarried men eighteen to twenty-five under arms allowed it to put three-quarters of a million troops in the field—an astonishing half million of which were deployed for combat service.26 In some early battles, Austrian forces faced opponents with a three-to-one numerical advantage. Animating French forces was an offensive geist very different from contemporary armies. Aggressive and mobile, they moved fast, unencumbered by supply trains. On the battlefield, they attacked in fat columns screened by skirmishers and supported by lighter, more maneuverable cannons, formed into large batteries.

THE NEW THREAT

Early campaigns against the French Republic were a foretaste of a new form of warfare for which Austria with its linear tactics and attritional approach to warfare was ill prepared. The man who would perfect these techniques was Napoleon. Born to parents of impoverished nobility on the island of Corsica, Napoleon was a junior artillery officer when the wars of the revolution broke out. After bold campaigns in Italy and Egypt, he was named consul in 1799, and in 1804, declared himself emperor of a new French Empire that would wage more than two decades of almost continual war against the armies of the Habsburg Monarchy.

In Napoleon, the Habsburgs were confronted with a very different kind of enemy than anything they had seen before. Unlike the Bourbon armies of the past, Napoleon formed his forces into large formations—divisions and corps rather than just regiments—that were able to operate as separate, self-contained armies in the field. Combining mass and mobility, the new French armies moved swiftly across Europe, ignoring many of the strategic and tactical considerations that had dominated warfare in the past. Where Louis XIV, Frederick, and the Turks had all to varying degrees relied on large supply trains that tied them to depots, Napoleon’s armies lived off the land, marching as the crow flies. Where Frederick had prioritized the reduction of fortresses, Napoleon bypassed them, only besieging two in his entire career.27 Where the Bourbons and Frederick had used attrition to achieve a peace on favorable terms, Napoleon sought the destruction of the enemy army.

Austrian strategy contributed indirectly to Napoleon’s successes. Faced with the dilemma of French forces being able to approach from both north and south of the Alps, Habsburg commanders dispersed their armies at the frontier in hopes of detecting and intercepting the enemy before it could reach the Erblände. The early phases of the War of the First Coalition found the army strung across a three-hundred-mile front from Switzerland to the Rhine. Fast-moving French armies, to a greater degree than in the past, could exploit the Rhine-Po dilemma. In 1800, they moved in parallel down both river valleys, occupying the Swiss passes to block Austrian movement between the two fronts. While Austrian units struggled to concentrate, Napoleon delivered the decisive blow in Italy. From this experience, the Austrians concluded that they needed to prioritize Italy. In 1805, they placed the main army there, allowing Napoleon to blitz down the Danube while defeating weaker Austrian forces at Ulm and Austerlitz.

As dangerous as Napoleon’s military behavior were his political moves. In his early campaigns in Italy and Germany, Napoleon revealed that he was motivated by a politically based strategy that targeted the weak spot of the enemy’s underlying strategic or political system. In Austria’s case, this weak spot, or “joint,” as B. H. Liddell Hart called it, was the monarchy’s numerous buffer states.28 Segmenting client state armies from the Austrians and defeating them in detail, he then treated generously with their governments to undermine loyalty to Vienna. In doing so, Napoleon took what had previously been a basic strength of the Habsburgs—numerous small clients—and turned it into a weakness.29 His aim was to permanently cleave these states from Austria and adhere them to France in a “rampart of republics” spanning Italy and Germany.30 In 1806, Napoleon formalized this arrangement by abolishing the Holy Roman Empire, the linchpin of the Habsburg buffer system, and replacing it with the new, French-dominated Confederation of the Rhine. He outlined his strategic intentions for this new body in a conversation with Metternich shortly after its creation:

I will tell you my secret. In Germany the small people want to be protected against the great people; the great wish to govern according to their own fancy; now, as I only want from the [German] federation men and money, and as it is the great and not the small who can provide me with both, I leave the former alone in peace, and the second have only to settle themselves as best they may!31

Grasping the underlying logic of Austria’s traditional client state model—guaranteeing the weak against the ambitions of the strong—Napoleon did the opposite, rewarding the strong at the expense of the weak to buy the former’s loyalties, and armies, for France. Where the Bourbons had wanted merely to divide Germany and diminish its value as an Austrian glacis, Napoleon sought to undo the mechanics of Habsburg primacy and unite the remnants into an offensive tool.

The scale of Napoleon’s ambitions made his threat to Austria not just territorial but also existential. Unlike in competitions against the Bourbons, Austria could not undo Napoleon’s wartime gains at the peace table. Initially, Habsburg diplomats had tried to use Napoleon’s defeats to continue the long practice of “rounding off” Austrian territories. But as the conflict widened, Napoleon cut more and more deeply into the political fabric of Austria’s buffers—and eventually, its home territories. At Pressburg in 1805, Napoleon took Dalmatia, gave Istria to a new Kingdom of Italy, and ceded Tyrol and Voralberg to France’s German clients, allowing the French Army to occupy bases directly overlooking Austrian territory.32 At Tilsit in 1807, he went even further, forming a new Polish state, the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, and forcing Austrian recognition of an enlarged Kingdom of Westphalia.33

By 1808, France and its surrogates confronted the monarchy on three sides in Italy, Germany, and Poland. As Metternich commented, any war with France from this point on “would begin at the same time on the banks of the Inn and the Wieliczka”—frontier rivers some four hundred miles apart.34 These changes spelled an end to the old Habsburg buffer system, and with it, the ability to conduct wars on Austria’s terms. This in turn put stress on the remaining component of Austria’s western system: extraregional allies. Successive military defeats undercut the logic of antihegemonic coalitions at the same time that they depleted Austrian resources for continued resistance. Prussia, an early and enthusiastic member of the anti-French coalitions, vacillated between policies of opposition and neutrality. Britain, though the most determined to outlast Napoleon, could do little to help Austria on land. As Archduke Charles wrote in 1804,

Britain always needs to keep a part of its regular army at home. The past war proved that victory is not to be expected of English troops on the continent. The mercantilist England is further unlikely to consider continental politics as its true purpose. The history of the past 150 years has proved as much…. Except for Marlborough, no Englishman ever found a way to pursue their maritime superiority on the Danube.35

By contrast, Russia possessed the greatest land power reserves for sustaining a prolonged struggle. In 1800 and 1805, Austria replicated the pattern of military coordination from the Seven Years’ War, at one point brokering the intervention of large Russian formations, under Suvorov as far west as Italy. The fundamental problem in such an arrangement was that as Napoleon pressed deep into the Habsburg home area, any Russian relief armies would place as great a burden on these lands as the enemy. As Charles noted, such allies

are good for little more than diversions [and] are of no consequence to the defense of the core territory. Even if another power were to allow 100,000–120,000 men to operate on Austrian soil, it should be kept in mind that the frontier provinces, Inner Austria and Tyrol, would not be able to sustain such a force. Importing such a mass of troops, if not entirely impossible, would be too expensive for Your Majesty’s finances.36

Moreover, as in the wars against Frederick, large distances and conflicting military cultures beset Austro-Russian military cooperation. Where a linkup between the two armies at Kunersdorf in 1759 had given Frederick II a severe defeat, similar coordination at Austerlitz in 1805 ended in Napoleon’s greatest victory. In all these alliances, the underlying challenge from an Austrian perspective was that its allies’ money, ships, or armies were too far away to make a difference at a sufficiently early point in each new war, leaving it to bear the brunt and expense of French aggression.

While facing unprecedented new external challenges, Austria also had to contend with its old internal problems, which grew more pronounced as the wars with Napoleon dragged on. By the twelfth year of war, the monarchy was bankrupt, forcing the military budget to be cut by more than half.37 Despite British subsidies, debts mounted, pressuring state finances and increasing the tax and inflationary burdens on the populace. Domestic strains emerged with a severity not seen since the early eighteenth century. As in the Austrian succession war, the Hungarian Diet voted a larger than usual revenue and military contribution for the war effort, which, as in that war, it failed to deliver. Previewing tactics they would employ again later, the Magyar nobility used the state of emergency to hand the dynasty a list of demands for fresh constitutional concessions. The diet refused conscription, and when the French attacked in 1805, commanders of the Magyar militia, or insurrectio, informed the invaders that Hungary “was neutral and would not fight.”38 Over time, the wars also steadily eroded the monarchy’s material base for waging war, whittling away the troop reserves at the same time that France accumulated new territories and clients through conquest.

RESISTANCE AND RECUEILLEMENT: 1808–12

By 1808, little remained of the security system with which Austria had once managed its westward frontier. Its Italian and German buffers gone, the monarchy could no longer intercept French armies before they reached Austrian soil. Without the help of the Reichsarmee operating on the Rhine and Mosel, it could no longer outsource management of the German theater to allies while concentrating its own forces south of the Alps. With the Reich dissolved and the Italian states converted to French clients, the challenge of anticipating and countering dual-pronged enemy thrusts had become pronounced. Lacking their early warning system, Habsburg forces would in any future campaign be confined to a restricted space—the Austrian home area—on which a French attack could fall suddenly, from two directions.

Faced with these straitened circumstances, Habsburg leaders debated two strategic options: to adjust to the French hegemony by accommodating Napoleon or fight a new war. Archduke Charles favored the former course. The foreign minister, Count Johann Philipp von Stadion-Warthausen (1763–1824), advocated the latter, reasoning that Napoleon had “not changed his hostile sentiments toward us and is only awaiting the right moment to prove it by deeds.”39 In the period since Austria’s last defeat, Stadion had pursued a policy of recueillement, avoiding any direct challenges to France in order to rebuild the monarchy’s finances and army until an opportunity presented itself to use them to restore the monarchy’s geopolitical position. By 1808, Stadion believed this opportunity had arrived and that Austria should “seek self-defense by taking the offensive” rather than letting the enemy attack on its terms, on the basis of its new advanced positions in Germany and Italy.40

The clenching argument for Austria to act at this particular moment was put forward by one of Stadion’s subordinates, Count (later Prince) Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, then serving as ambassador to France. In a series of three memorandums, Metternich outlined the case for war. All three concentrated on the factor of timing. In the first, he argued that deteriorating French public support for Napoleon meant that in any new war, the French emperor would be distracted at home. The second asserted that Russia, despite its tacit 1807 alliance with France, would not attack Austria; “Alexander,” Metternich wrote, “is not someone the French can enflame against us; to the contrary, he desires an intimate bond with us, which he believes we may yet reach through persistence.”41 In the third memo, Metternich made his strongest strategic argument: Napoleon’s army was absorbed in and depleted by its attempt to subjugate Spain:

The war against Spain divulges a great secret—namely, that Napoleon has but one army, his Grande Armee…. The questions to consider [are]:

(1) What are the total forces of France and her allies at this present moment?

(2) After deducting from the whole of these forces the number of men employed in the conquest of Spain, what number of effective troops could Napoleon bring against us?

(3) What resources has Napoleon for carrying on the war against Spain and against us at the same time? [emphasis added] …

The summary of the military position appears to me to be the following: (a) Napoleon can fight us now with 206,000 men, of whom 107,000 are French, 99,000 confederate and allies. (b) His reserves can after a time only be composed of conscripts below the age for service…. Thus the forces of Austria, so inferior to those of France before the insurrection in Spain, will be at least equal to them immediately after that event.42

Against France’s divided forces, Austria’s generals believed that through expanded conscription and the organization of militia units in politically reliable parts of the monarchy they could field the largest army in the monarchy’s history—some 550,000 troops.43 In addition, Stadion was convinced that the German popular sentiment recently stirred by Napoleon’s conquest of Prussia could be harnessed to Austria’s cause, and with early victories, Russia and Prussia might be convinced to enter as allies.

THE 1809 WAR

Given these favorable conditions, Stadion and the emperor, Francis II (I), judged that the moment for war was better than it would be again at any time in the foreseeable future. Leading Habsburg forces in the coming campaign was the emperor’s younger brother, Archduke Charles. In 1809, Charles was thirty-seven years old and in the prime of his military career.44 Unlike most of Austria’s senior generals, he had shown the ability to hold his own against the French, delivering victories in Holland, Italy, and Switzerland. In 1805, he had been with the main army in Italy when Napoleon entered Austria through Germany. Epileptic and cerebral, Charles was a cautious commander who prioritized retention of key points of terrain and protection of communication lines over defeating the enemy (see chapter 4). Surveying Austria’s financial and troop shortages, Charles had misgivings about the campaign’s timing, which would later be validated.

When war was declared, Napoleon quickly shifted attention and resources from Spain to the Danube, while Austria mobilized fewer troops than expected.45 Neither German popular sentiment nor Russian and Prussian help materialized. As in the past, the dilemmas of Austria’s multivector geography hurt it. With part of the army deployed in Italy, the army had to choose between concentrating the main force in Bohemia, whence to strike into Germany, or the River Inn, to cover the capital. Ultimately choosing the latter, Charles also had to siphon off units to cover the Tyrol, Dalmatia, and Poland.46

When the French invaded, Charles adopted a strategy not unlike that used by Daun against Frederick. Rather than trying to intercept Napoleon outside Vienna and seek a decisive battle on the right side of the Danube, he used Austria’s rivers to delay and wear down the stronger enemy forces. Charles’s chief of staff, Maximilian Freiherr von Wimpffen, outlined the strategy in a memorandum of May 17:

If the French lose the battle, … they risk everything and us only a little. If we were to cross the Danube now, it would be the opposite: the Austrian emperor would not even be able to negotiate anymore before the monarchy were conquered. Fabius saved Rome, and Daun saved Austria not in haste, but through delay [nicht durch Eile, sondern durch Zaudern]. We must emulate their example and prosecute the war according to our patterns, befitting the state of our armed forces. Our supports are close, whereas the enemy is far from his. In holding the left bank of the Danube, we are defending the greater part of the monarchy. We would lose tremendously by crossing to the other side. Our army can reinforce itself from its depots, whereas Napoleon only expects another 12,000 Saxons…. We require the resources of the left Dabune bank for our armed forces, whereas the right side could not provide as such. If we make use of this quiet hour [Schäferstunde], we can prepare everything for quickly seizing the right moment.47

The ensuing campaign showed the influence of earlier Habsburg commanders in Charles’s thinking. Preparing for a protracted war in the Austrian countryside like that which the Prussians had brought to Moravia a generation earlier, Charles anticipated the alienating effects that French requisitions of supply would have on the local population, instructing his own commanders to prevent similar behavior among their troops under threat of “severe punishments” (strenge Strafen).48 Forming defensive positions behind the Danube, Charles emulated Prince Eugene at Zenta, destroying the enemy in detail as it attempted to cross and re-form ranks on the other side.49 The strategy worked: with Austrian armies en route from Italy to threaten the French rear, and the danger of Russian or Prussian entry looming, Napoleon felt a time pressure not unlike that felt by Frederick in his Moravia campaigns. Attacking across the river, he suffered the first significant defeat of his career, at Aspern-Essling, on May 21–22. While Montecuccoli would have admired Charles’s dispositions along the Danube, his attachment to the precepts of attritional warfare prevented the Austrian Army for not the last time in its history from capitalizing on victory.50 After the battle, Napoleon quickly recovered his equilibrium to defeat the Austrians at Wagram and force the monarchy to sue for peace.

In the peace negotiations that followed, Austria lost a swath of valuable home territories to France and its allies: Salzburg to Bavaria, West Galicia to the Duchy of Warsaw, East Galicia to Russia, and southern Carinthia, Croatia, Istria, Dalmatia, and the port of Trieste to France. Altogether, the peace of Schönbrünn carved 32,000 square miles and 3.5 million inhabitants out of the Habsburg Monarchy, while levying a large indemnity and restricting the Habsburg Army to 150,000 troops. Together with previous territorial losses, the new status quo sheared Austria of a substantial portion of its economic and manpower base for conducting future wars. Geopolitically, it was now encircled by Napoleon and his proxies in Italy, Germany, Poland, and Croatia, making France the only opponent in Austria’s history to attain a standing military presence on four Habsburg frontiers simultaneously.

ACCOMMODATING NAPOLEON

After the 1809 war, Austria found itself in the position of a shrinking second-rate power wedged between the French and Russian empires. With Metternich at the helm, Austria now adopted a strategy of accommodation. The monarchy’s only hope for survival, Metternich wrote, was “to tack, to efface ourselves, to come to terms with the Victor. Only thus may we perhaps preserve our existence till the day of general deliverance.”51

A new policy along these lines would seem to be diametrically opposed to the course of isolated resistance that Austria had pursued in the lead-up to the 1809 campaign. But there was more continuity than change in Austrian strategy, for Metternich’s goal, like that of Stadion, was to achieve a period of recueillement in which to play for time and gather strength. To do so he now embraced the first of the two strategic options that Vienna had been debating since Pressburg and Tilsit: cohabitation with the enemy. This was not the first time Austria had to accommodate a stronger foe to survive. Habsburg monarchs had long used temporary peace arrangements to improve the monarchy’s circumstances before returning to deal with an enemy from a position of strength. One example was Joseph I’s dealings with the Ottomans and Hungarians ahead of Eugene’s campaigns, Maria Theresa’s acquiescence to the Convention of Kleinschnellendorf another.

Metternich proceeded on a similar logic, but on a larger scale. Where Austria had often used tactical reprieves to gain positional advantages over enemies for short periods, Metternich faced the possibility of a long domination by a revolutionary opponent who had already demonstrated his capacity to dismantle the ancien régime. Where Stadion had aimed to break this hegemony and restore Austria’s position in Germany and Italy, Metternich sought to come to terms with the hegemon in a prolonged marriage of convenience until a new day, however distant, dawned. If unsuccessful, Austria could face a gradual diminution between a Russian-dominated Balkans and French-dominated central Europe—in short, everything that its strategies had worked to avoid for more than a century. If Austria misplayed its hand, it was not unimaginable that it could be carved up among the mosaic of Napoleon’s Germanic client kingdoms.

Austria needed to stave off extinction while keeping an eye on how its moves would position it after the war. To this end, Metternich became an obliging, if duplicitous, handmaiden to the new order. To bond the two states more closely together, he brokered the marriage of Marie Louise (1791–1847), Emperor Francis’s eldest daughter by his second wife, to Napoleon. Coming less than a year after Austria’s 1809 defeat, the move was humiliating for the Habsburgs, entailing the unification of an eight-hundred-year-old dynasty with a self-made general who represented the negation of the social order that the monarchy embodied. Nevertheless, the marriage served Metternich’s goals, buying time by placating Napoleon and enhancing Austria’s position relative to Russia.

In spring 1812, Metternich’s policy reached its culmination when Austria entered into a formal military alliance with France, providing thirty thousand troops to assist, albeit indirectly, in Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. The desperation of Austria’s position is illustrated in the fact that Metternich was willing to bandwagon with a revisionist power, even if largely symbolically, in an attack on a power that represented the linchpin of Austria’s long-term security interests. Joining in the invasion aided in Austria’s game of keeping its head down as Napoleon’s gambles exhausted French strength. In his diplomacy, Metternich was waging a larger geopolitical game of Fabian evasion and attrition like that which Charles and Daun had used on the battlefield, paralleling the moves of a stronger opponent and avoiding actions that would overplay Austria’s hand.

System Restoration: 1813–14 and the Metternich System

With Napoleon’s defeat in Russia, the opening for which Metternich had waited intermittently since 1805 appeared. Unlike in 1809, circumstances now overwhelmingly favored military action.52 The scale of the disaster made France militarily weaker than it had been at any point since 1792. The series of recueillements undertaken by Stadion and Metternich had accomplished their purpose of giving Austria time to recuperate. As in the interlude between wars with Frederick II, Austria had used its post-1809 reprieve to mobilize internal capabilities, tending militia cadres and leveraging the resources of the Military Border. As a result, by the time war again broke out, the monarchy possessed a veteran core around which to quickly assemble armies that would number 160,000 by April 1813, 479,000 by August, and eventually reach 568,000.53

As in the Prussian wars, the Austrians had learned from their defeats at the hands of the French, forming postwar commissions to study lessons learned, and revamp tactics and doctrine—first in 1798–99, and again in 1801–4 and 1807. Also as in the Prussian wars, the responsibility for military strategy was centralized and eventually filled with better talent. Charles was given combined authority for the Hofkriegsrat and new Militär-Hof-Commission ahead of the 1805 and 1809 campaigns, and a young officer, Radetzky, was installed as chief of the quartermaster of the General Staff.54 And as in previous wars, protracted emergency prompted a tighter interweaving of diplomatic and military goals, with Stadion and Metternich, like Kaunitz, exercising decisive influence on overall strategy.

External factors also favored action. Where Russia had been ponderous and distant in the earlier campaigns, and neutral when Austria was losing in 1809, it was now bringing its large resources fully into play. Prussia too was entering the scales with a rebuilt army backed by patriotic fervor. Britain, committed as always, now raked in a harvest of easy gains on French peripheries rendered vulnerable by Napoleon’s eastern gambit. With this alignment of forces, Austria could now, after four years of self-abasement, reenter the military competition with prospects of success.

At the same time, with the other powers mobilized and Austria still occupying its truncated post-Schöbrunn form, the monarchy was in a weak position to shape the coming contest. In particular, the growth of Russia as a military factor in European affairs, both through its acquisitions at Tilsit and the steady westward trek of its enlarged land armies, threatened to supplant French hegemony with de facto Russian dominance. To counter this prospect, Metternich adopted a strategy centered on restraining the growth of Russian influence in Europe.55 Its objectives were to retain France as a factor of balance against Russia, regain Austria’s lost buffers, and engage the German states, most of which were now French allies, as factors of stability.

These goals, already coagulating before Napoleon’s defeat, would guide Habsburg grand strategy throughout the coming 1813–14 campaign and well into the postwar period. Where Metternich had previously used accommodation to avoid unfavorable military outcomes, he now employed the army to avoid unfavorable diplomatic outcomes. He held two military cards with which to influence outcomes. One was control over the timing of when the Habsburg Army would enter the war. Rather than rushing into the conflict, Metternich delayed, remaining France’s nominal ally and shifting to neutrality before entering the coalition. Withstanding pressure from the Russian and Prussian monarchs, he continued on this path until events on the battlefield ensured that Austria’s entry would carry the greatest diplomatic impact. As Metternich later wrote,

The Emperor left it to me to fix the moment which I thought most suitable to announce to the belligerent powers that Austria had given up her neutrality, and to invite them to recognize her armed mediation as the most fitting attitude. Napoleon’s victories at Lützen and Bautzen were the signs that told me that the hour had come.56

Metternich’s characterizations of his actions and motivations as recounted in his memoirs have to be read cautiously, as these were written with the benefit of hindsight and desire to cast his own role in the most positive light. Paul Schroeder has convincingly argued that Metternich’s real reason for delaying Austrian entry into the war was in fact to “give peace a chance” at a moment when Emperor Francis was averse to military action.57

Nevertheless, it is also clear that Metternich understood that delaying Austrian entry until Napoleon had won new battles would improve his negotiating position vis-à-vis Russian and Prussian allies who would now be less confident in their own margin of strength, and thus more keenly aware of their need for Austrian assistance. Delaying also helped to establish Austria as an independent force early in the campaign, wearing down both the French and Russian armies while leaving open as long as possible the potential for a negotiated peace in which Austria, as the mediating power, would have held the scales between the two forces.

Once committed to the war, Austria had a second card to play: determining where its army would be deployed. In this, Metternich benefited from his and Stadion’s earlier policies of recueillement. Out of a total coalition force of 570,000, Austria’s troops made up 300,000, rendering it the largest military force in the alliance and the essential factor for taking the fight against France, which was capable of fielding 410,000 troops.58 On the reasoning that “the power placing 300,000 men in the field is the first power, the others are auxiliaries,” Metternich insisted on an Austrian general, Prince Felix Schwarzenberg, being named commander in chief of the allied forces.

In the field, Metternich used Austria’s alliance leadership to advance his goal of avoiding a weakening of France that could fuel the growth of Russian power. Rather than advancing directly across the Rhine to deliver a decisive defeat on the recoiling French, he sought to slow and redirect operations to Austria’s advantage.59 Prussian military writers would long criticize Schwarzenberg’s attritional plans as laggardly. As Delbrück complained a century later, “The Austrians refused to move out and either intentionally or unintentionally clothed this reluctance with strategic considerations. They based their stand on the fact that neither Eugene nor Marlborough, both of whom were also great commanders, had ever directed their operations against Paris.”60

From an Austrian strategic perspective, however, Schwarzenberg’s actions conformed to Metternich’s method of “always negotiating but negotiating only while advancing.”61 Militarily, they were a triumph of attritional warfare, using numerous allied armies to apply a tourniquet that steadily deprived Napoleon of the benefit of interior lines while denying him the opportunity for decisive battle that would have played to advantage. Politically, the campaign maximized Austria’s opportunities to consolidate its old buffers and create openings for a negotiated settlement with France as a counterbalance to Russia. Had the armies moved more quickly into France and the disoriented French army capitulated in 1813, as was likely, Russian influence over the resulting political configuration would have been greater and the odds of a postwar equilibrium smaller. By buying Austrian diplomacy a few extra months, Schwarzenberg helped to ensure that Metternich would not only have a stronger position vis-à-vis the allies but would be able to count whatever new French government came into being as an Austrian ally, too.62

POST-NAPOLEONIC WESTERN SECURITY

Through his eleventh-hour maneuverings, Metternich positioned Austria to exercise a decisive influence over the postwar peace settlement. As we will see in the next chapter, the congress method he helped to engineer would mark the apogee of Habsburg diplomatic achievement. The fact that this system developed a pan-European character has tended to obscure its significance at the regional level vis-à-vis France specifically. For the purposes of this chapter, it is worth noting that the security system that Austria put in place after the Napoleonic Wars to secure the western frontier was a reinstatement of the basic principles that had guided Habsburg strategy against the Bourbons, but it was adapted to reflect the recent lessons.

As before, Austrian security in the west was rooted in the maintenance of buffers. The wars with Napoleon highlighted the importance of these intermediary bodies while revealing their susceptibility to subversion by an outside power. This problem had both a military and political dimension. Militarily, Napoleon’s armies had pried apart the patron-client link at its vulnerable “joint” (the client); politically, he had been able to exploit internal dynamics in client state groupings by inverting the Habsburgs’ traditional balancing of larger and smaller members while introducing a powerful new force of nationalism. Together, these methods represented a far more effective threat than anything the Bourbons had ever attempted through bribery and manipulation of middle-state courts. They had led to the death of the old German Reich; if used again in the future, such methods could conceivably lead to a lasting breakdown in Austria’s western buffer-state system, placing the burden of security on the army alone.

In its postwar actions, Austria moved to address both dimensions of this problem. In Germany, Metternich worked to retain a confederated format, allowing the old Reich to remain dead, and devising in its place a reorganized and streamlined German Bund.63 In Italy, he sought to inject a greater degree of confederation than had existed in the past by grouping Austria’s territories into a new Italian League modeled on the Bund.64 While the latter failed, in both cases Metternich’s aim was to enhance the political viscosity of Austria’s buffers and improve serviceability as a geopolitical hedge. The number of states in Germany was reduced from three hundred under the Reich to thirty-nine in the German Bund. The new Article 47 committing members, if attacked, to come to one another’s aid replaced the messy Reichskrieg process. While shedding the title of Holy Roman emperor, Metternich ensured that Austria retained its leadership role as president of a new Federal Diet. Where Austria had cemented its primacy in the old Reich by being a protector of the smallest and most vulnerable states, it now was able, by championing sovereignty against not only France but Prussia and the force of nationalism as well, to expand its support base to include most of the new states in the German Bund, including old enemies like Bavaria. These changes allowed Austria to emerge from the war not only with its German buffer intact but also more geopolitically reliable than it had perhaps ever been.

Similarly, the Napoleonic Wars affected how the Austrian military thought about securing the western frontier. On a fundamental level, they reinforced the long-standing conviction that the monarchy’s ability to defend itself here was inextricably linked to the fate of the intervening space between itself and France. The wars had shown more clearly than ever that Austria’s western defense began on the Rhine and Po Rivers. By the time a foe reached the Habsburg border, the game was largely over. Should the territory of frontline states in these regions fall swiftly to an attacker, either because of their own underdeveloped defenses or because reinforcements could not reach them in time, the chances of waging a successful defensive campaign shrunk dramatically.

To address this problem, Vienna worked to enhance the ability of Austrian forces to maintain forward positions in Italy and Germany. Where past Habsburg defense policy had always been based to some extent on western networks of fortresses, it now sought to dramatically increase the size and number of fixed defenses in these territories while deepening their integration into the monarchy’s defense policy. Altogether in the postwar period, Austria’s military planners envisioned seventeen fortresses to ring-fence the French frontier. In Germany, they worked with the Bund to eventually develop five large forts—Mainz, Landau, and Luxemburg, and later, Ulm and Rastatt—tied together by smaller installations held by frontier member states and backed by an Austrian garrison in the federal city of Frankfurt.65 In Italy, Austria expanded its old defensive positions near Lake Garda into a defensive complex—the famous “quadrilateral”—linking Mantua, Peschiera, Legnago, and Verona, while brokering rights to garrison the papal fortresses of Ferrara and Comacchio along with the Parmesan Piacenza.66 Together, these defensive clusters were intended to alleviate the Po-Rhine dilemma by bogging down French offensives and buying time for reinforcement as needed, north or south of the Alps.

As important as the physical location and extent of these fortifications was the Austrian system for garrisoning and financing them. As in the past, the monarchy could not, in its parlous postwar financial position, afford to sustain extensive, permanent deployments and infrastructure in the west on its own. To defray the costs of the new defenses, Austria looked partly to its defeated foe, levying a seven-hundred-million-franc war indemnity, of which sixty million would go directly to the construction of the new Rhine fortresses. In addition, it looked to the buffer states themselves to share in the burden of defense, setting up a fund in the German Bund, endowed by member contributions, earmarked for the development and maintenance of western forts.67 The burden of manning these posts would be spread among Bund members, which were now required to maintain, train, and outfit forces within the fortresses as well as a wider, revised Bund corps system on a fixed, proportional basis according to population.68

As a collective security infrastructure, the Bund’s forts represented a considerable improvement over the old tutelary fortress model. Operationally, the standing military agreements of the new German Bund were more dependable than reliance on a Reichskrieg declaration, which even if successful, tended to place disproportionate risks and costs on the shoulders of the Reich’s most exposed states. The Bund format provided the Austrian military with what, in today’s terms, would be the equivalent of thirty-nine separate status of forces agreements (SOFAs) in one fell swoop. In essence, they transformed Germany into a giant-size version of the old Nördlingen Association, ensuring higher and more evenly spread defense contributions while committing even the least exposed members to the defense of the whole on a more predictable basis.

To underwrite Austria’s expanded forward defenses, Metternich also updated the third pillar to its traditional western security system: Great Power alliances, brokering extensive new agreements committing other European powers to the maintenance of treaty rights, to be upheld through frequent conferences. For the western frontier specifically, he backed this with a formalized mechanism—the Quadruple Alliance—committing Britain, Prussia, and Russia to mutual defense in the event of a reemergence of the French military threat. As with changes to the Austrian buffer system, this grouping represented the continuation of a long-standing Habsburg policy approach while evolving it into a more predictable format.

The Quadruple Alliance represented an improvement on the method of recruiting outside powers into the comanagement of Austria’s German position through ad hoc military expeditions to the Mosel Valley and a more stable security mechanism than periodic, Kaunitzian détentes at the bilateral level. Rather than relying on last-minute antihegemonic groupings, the new setup made containment of France a systemwide responsibility, formally tying Austria’s western security needs to the interests and resources of the Great Powers. While implicitly recognizing the public benefit that all states derived from prevention of hegemonic wars, the new alliance system disproportionately benefited the continent’s central power, Austria, ensuring that the burdens for its maintenance would be borne by several powers and not just by itself.

Viewed panoramically, Austria’s long competition with France is the story of a relatively weak power outmaneuvering and outlasting a stronger rival. At no point in these wars, with the debatable exception of the campaign of 1814, can Austria be said to have been a stronger military power than France. Its defense establishment was usually smaller, its internal composition always more fragile, and its finances more tentative. And yet Austria has to be judged the winner in the majority of these contests. In a period of about a century and a half, it checked the northward and eastward expansion of Louis XIV, recruited his successors into the joint containment of Prussia, staunched the Jacobin tide, and organized or participated in six military coalitions against the republic and Napoleon, emerging as the arbiter of the European balance and presiding over the dismemberment of a French Empire that stretched from the Atlantic to Poland.

Austria’s greatest asset in these contests, paradoxically, was its own weakness. At face value, the sprawling nature of Habsburg western interests presented an unmanageable set of security liabilities. But France’s comparative strength across this large space, by making it a threat to other states, presented a natural base of resistance to French expansion that with moderate effort, Austria could usually harness to its own security needs. The tools that Austria used for this purpose—the Reich, its Italian satellites, maritime alliances, and the anti-Napoleonic coalitions—varied in format, but all essentially involved the co-optation of other states on the basis of shared fear to manage a threat that while mutual, ultimately posed a disproportionate risk to the continent’s central empire—Austria. In this sense, the monarchy’s exposure to Europe’s seismic core made it a surety on the stability of the continent.

The groupings that Austria organized gave it a reservoir of troops to even the odds against French military power. The wrinkle, so to speak, in all these arrangements was time. Contests on the western frontier ultimately came down to which could be brought to bear more quickly: France’s advantage in offensive military capabilities or Austria’s advantage in alliances. The latter are, by nature, slower to activate. For this reason, Austria usually lost the opening rounds of its wars with France, experiencing repeated losses in the Low Countries and seeing Rhine fortresses fall in the early stages of the Bourbon wars. Improvements in the speed of warfare brought by Napoleon were in this sense the culmination in a centuries-long arms race between offensive armies and defensive alliances.

It is in the mitigation of this French time advantage rather than efforts to equalize troop contests per se that Austria’s western security system achieved its defining contribution. The recruitment of Italian and German buffer states, initially a purely dynastic impulse, provided a medium that, as competition evolved, became more crucial for survival. The addition of fortresses enhanced buffer-state value, interposing a series of longitudinal barriers that compensated for the latitudinal layout of the Alps. In the Bourbon wars, buffer fortress complexes allowed the monarchy to toggle its own forces between frontiers, offsetting France’s advantage as a three-front aggressor. When this system broke down in the Napoleonic Wars, Austria developed a backup strategy that was, again, focused on time, alternating between seasons of accommodation and short bursts of resistance that avoided overwhelming it financially, while drawing out the wider contest until its core advantages in allies and legitimacy could be brought to bear. At the end of these wars, Austria invested its postwar windfall to lock in a lasting time advantage, effectively closing off southern Germany and northern Italy as French military highways.

This progression of Habsburg techniques underscores the political as opposed to military nature of Austria’s overall western strategy. Arrangements with other states had a higher geopolitical value if already in place before a conflict began. The more regularized the grouping, the more effective, both in absorbing the initial French military advances and reducing the standing defense costs that Austria would have to bear. There is a clear evolution in Habsburg strategy of seeking increasingly regularized alliance formats, both with weaker clients and Great Powers, from Joseph I’s renewal of the Reichskrieg format and Leopold’s encouragement of the Nördlingen Association, to Thugut’s and Stadion’s coalitions, and ultimately, Metternich’s Bund and congress system. In these groupings, the military value of buffers, measured in the predictability of Austrian forward military deployments, increased in proportion to the viscosity of the underlying political arrangements.