When dropped into a glass of cold water, sugar will simply dissolve. Starting at 230°F (110°C), sugar dropped into water will form a soft thread that will not hold a shape and will dissipate.

At these temperatures, syrups are formed, not tactile confections. In some instances, the syrup itself is the finished product. In other instances, the hot syrup is an integral element in the formation of a more complicated pastry component (macaron shell, pâte à bombe, Italian meringue). When combined with proteins (eggs and cream) in making a custard on the stovetop, such as crème anglaise or pastry cream, sugar delays the coagulation of the protein structures and allows the custard thicken properly. Sugar acts as crowd control, fanning out among the protein molecules that want to clump together and congeal. In meringues, sugar stabilizes the mixture by, again, dispersing the proteins and creating that signature shiny-white, stiff meringue.

At this stage of heating, sugar becomes the great enforcer, bullying ingredients into behaving deliciously when things start getting hot.

I love rock candy. It’s pure sugar. That’s it. It doesn’t pretend it’s anything more than an unadulterated cavity maker. Just look at it: Instead of itsy-bitsy granulated morsels that can easily hide, rock candy is a series of gigantic, in-your-face sugar crystals. It’s the badass of candies, and yet it’s beautiful, too. When I am reincarnated—and you know I’m coming back as something sweet—I want to come back as rock candy.

Approach making rock candy as a lab experiment; it’s kind of like shoving toothpicks into an avocado seed, setting it in a jar of water on your windowsill, and waiting months for it to sprout. Rock candy doesn’t take as long as the avocado but it is a week-long process—and well worth the time.

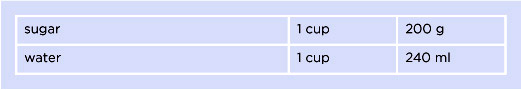

Makes 2 large rock candies or up to 20 miniature rock candies

Dissolve the sugar in the water by gently heating the two in a saucepan over medium-low heat. Once all the sugar has melted, take the syrup off the heat and allow to cool very slowly and completely. Alternatively, place the sugar and water in a microwave-safe container and stir, making sure to saturate the sugar with the water. Microwave for 3 minutes on high. Stir. Nuke for 3 more minutes and stir. The sugar has probably melted by now but make sure, and nuke for a few more minutes. Allow to cool completely. Run the solution through a fine sieve.

Dissolve the sugar in the water by gently heating the two in a saucepan over medium-low heat. Once all the sugar has melted, take the syrup off the heat and allow to cool very slowly and completely. Alternatively, place the sugar and water in a microwave-safe container and stir, making sure to saturate the sugar with the water. Microwave for 3 minutes on high. Stir. Nuke for 3 more minutes and stir. The sugar has probably melted by now but make sure, and nuke for a few more minutes. Allow to cool completely. Run the solution through a fine sieve.

Divide the cooled syrup into two tall glasses. Cut two lengths of cotton or wool cooking string that are just a wee bit shorter than the height of the glasses and dip one into the mixture in each glass. Make sure the strings are saturated. Remove the strings, roll them in extra granulated sugar, and let them dry completely on a piece of wax or parchment paper, at least overnight and for up to 2 days, depending on the humidity. Alternatively, pour the entire batch of syrup in a large, shallow casserole dish and, depending on the size of the vessel, dip as many toothpicks as you can reasonably expect to fit into that surface, allowing for a 2-inch perimeter for each toothpick when it’s suspended in the drink. Remove the toothpicks and let them dry completely, as above, at least overnight and for up to 2 days.

Divide the cooled syrup into two tall glasses. Cut two lengths of cotton or wool cooking string that are just a wee bit shorter than the height of the glasses and dip one into the mixture in each glass. Make sure the strings are saturated. Remove the strings, roll them in extra granulated sugar, and let them dry completely on a piece of wax or parchment paper, at least overnight and for up to 2 days, depending on the humidity. Alternatively, pour the entire batch of syrup in a large, shallow casserole dish and, depending on the size of the vessel, dip as many toothpicks as you can reasonably expect to fit into that surface, allowing for a 2-inch perimeter for each toothpick when it’s suspended in the drink. Remove the toothpicks and let them dry completely, as above, at least overnight and for up to 2 days.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: This is my first warning about sugar and moisture but certainly not my last. Moisture is the bane of sugar work—perfectly executed brittle on a rainy day can turn into a sticky, malleable mess in under an hour. The whole point of heating sugar is to evaporate the moisture hidden within the granules; the hotter the sugar gets, the more moisture is sloughed off. In the case of rock candy, we’re only heating the sugar to melt in water. Plenty of moisture there, right? So what’s the big deal about drying the sugar-saturated string before dipping it back into the drink? Well, it’s a big deal because no sugar granule wants to stick to a soggy string. And you’ll find it virtually impossible to dry your string on a humid day. But unlike brittle or caramel, you can do something to save the day when that sticky little string refuses to dry. Place your sugar-saturated string(s) on a parchment-lined sheet pan and let them dry out in a very low-heat oven, about 200°F (90°C) to 220°F (105°C), for about 20 minutes. Pinch the string with dry hands to make sure it’s no longer tacky to the touch before dipping it back into the sugar mixture. For more rock candy troubleshooting tips, go to www.sugarbabycookbook.com.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: This is my first warning about sugar and moisture but certainly not my last. Moisture is the bane of sugar work—perfectly executed brittle on a rainy day can turn into a sticky, malleable mess in under an hour. The whole point of heating sugar is to evaporate the moisture hidden within the granules; the hotter the sugar gets, the more moisture is sloughed off. In the case of rock candy, we’re only heating the sugar to melt in water. Plenty of moisture there, right? So what’s the big deal about drying the sugar-saturated string before dipping it back into the drink? Well, it’s a big deal because no sugar granule wants to stick to a soggy string. And you’ll find it virtually impossible to dry your string on a humid day. But unlike brittle or caramel, you can do something to save the day when that sticky little string refuses to dry. Place your sugar-saturated string(s) on a parchment-lined sheet pan and let them dry out in a very low-heat oven, about 200°F (90°C) to 220°F (105°C), for about 20 minutes. Pinch the string with dry hands to make sure it’s no longer tacky to the touch before dipping it back into the sugar mixture. For more rock candy troubleshooting tips, go to www.sugarbabycookbook.com.

Resubmerge the now dry strings into the sugar water, weighing each end down with a non-lead fishing weight, a washer, or something equally heavy to keep the string straight. Tie the top end of each string to a pencil placed across the lip of the glass so that the string suspends gently in the liquid. If you’ve chosen the shallow-dish method, secure a piece of parchment or plastic wrap tautly across the top of the dish with a rubber band and poke the toothpicks through so they are suspended in the liquid and held tightly in place by the parchment or plastic.

Resubmerge the now dry strings into the sugar water, weighing each end down with a non-lead fishing weight, a washer, or something equally heavy to keep the string straight. Tie the top end of each string to a pencil placed across the lip of the glass so that the string suspends gently in the liquid. If you’ve chosen the shallow-dish method, secure a piece of parchment or plastic wrap tautly across the top of the dish with a rubber band and poke the toothpicks through so they are suspended in the liquid and held tightly in place by the parchment or plastic.

No matter your method, let your experiment sit for at least 7 days. I usually keep my experiment going for a few weeks for maximum rock-candy goodness, and I’ve found the process is much speedier in the cool, dry winter months. It’s worth gently wiggling your strings or sticks every few days to keep the ends from adhering to the bottom of the glass or dish.

No matter your method, let your experiment sit for at least 7 days. I usually keep my experiment going for a few weeks for maximum rock-candy goodness, and I’ve found the process is much speedier in the cool, dry winter months. It’s worth gently wiggling your strings or sticks every few days to keep the ends from adhering to the bottom of the glass or dish.

Remove the strings or sticks when you’re satisfied with the amount of crystal growth. Store in an airtight container for up to 1 month.

Remove the strings or sticks when you’re satisfied with the amount of crystal growth. Store in an airtight container for up to 1 month.

If you’re feeling particularly fancy, replace the 2 cups (480 ml) water with 2 cups (480 ml) coffee to produce java-infused bonbons.

GF: In the food world, it doesn’t stand for “girlfriend.” It means “gluten free,” girlfriend. And you’ll find that most of the recipes in this book are just that (gluten free, that is, not girlfriends—but if you’re in the market for a girlfriend, making something from this book for a nice lady person might get you closer).

Gluten allergies have become rampant. Allergies in general, for that matter. I can’t remember anyone in elementary school having any food ailment—or if they did, they suffered their gastrointestinal discomforts in silence. But once I started to bake professionally, the litany of allergies for young ones and older folks alike made for a long list of allergen-free treats I had to have on deck. Thankfully, I’ve always had a healthy arsenal of gluten-free desserts on call, not for any particular reason other than I liked them. So whether you’ve got a slight wheat aversion or full-blown celiac disease, know that this book is going to be a very handy guide to allergen-free treats.

How plain and simple is a plain simple syrup? Take a cup of sugar, pour it into a cup of water, heat the mixture until the sugar is dissolved, and voilà! Simple syrup. You may ask yourself, “Why bother?” Well, have you ever wondered how fancy pastry shops keep their cakes so moist? No? Okay, let’s try this: Have you ever wondered how to keep your own cakes moister, longer? If so, then simple syrup is the stuff for you. Once the syrup is cooled, simply brush a bit of it on top of each layer of cake. You don’t want to soak it through and make it soggy; just dip a pastry brush into the syrup and gently apply a small amount.

You may add extracts—lemon, ginger, peppermint, lavender, almond, and the like—to the simple syrup, not only to moisten your cakes but also to heighten their flavors. If you’re so inclined, you can also replace the water with coffee. I use coffee syrup on chocolate cakes, since coffee is a lovely enhancer for cocoa flavor. The list could go on, but you get the idea: This stuff is versatile.

And it’s not just for cakes. At Gesine Confectionary, my former pastry shop in Montpelier, Vermont, we always kept a bottle of simple syrup at the coffee station for sweetening iced coffees or fresh-brewed iced tea. No more stirring and stirring, waiting for those pesky granules to dissolve and infuse your icy drink with sweetness. A couple pumps of plain-and-simple and you’re ready to rumble.

Makes 2 cups (480 ml)

In a microwave-safe container, microwave the sugar and water for 5 minutes. Stir to make sure all the sugar is dissolved. Nuke for a few more minutes, until all the sugar is dissolved into the water. Allow to cool before using.

In a microwave-safe container, microwave the sugar and water for 5 minutes. Stir to make sure all the sugar is dissolved. Nuke for a few more minutes, until all the sugar is dissolved into the water. Allow to cool before using.

If you’re making this on your stovetop, simply heat the water and sugar in a heavy saucepan over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until the sugar is dissolved. Again, cool before using.

If you’re making this on your stovetop, simply heat the water and sugar in a heavy saucepan over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until the sugar is dissolved. Again, cool before using.

The yield can easily be doubled, tripled, or quadrupled, as the ratio is always 1 cup (200 g) sugar to 1 cup (240 ml) liquid. Store in refrigerator until needed.

The yield can easily be doubled, tripled, or quadrupled, as the ratio is always 1 cup (200 g) sugar to 1 cup (240 ml) liquid. Store in refrigerator until needed.

OPTION 1: COFFEE SIMPLE SYRUP

For a delicious variation, replace the water with an equal amount of coffee and follow instructions for simple syrup above.

OPTION 2: LEMON SIMPLE SYRUP

In the summertime, I’ll squeeze piles of lemons and make a pitcher of lemon simple syrup. The ratio remains the same: 1 cup (240 ml) lemon juice to 1 cup (200 g) sugar. One thing I add to the syrup is the rind of the lemon—the quality of the juice is deeply enhanced by cooking with the zest. Using a Microplane, zest the rind into the juice. Heat the zest along with the juice and the sugar according to the instructions for simple syrup above. Allow the zest to steep in the syrup until it’s completely cooled, pour the syrup through a fine sieve to remove any bits of zest, and refrigerate.

I whip out the lemon syrup to make homemade lemonade whenever the summer heat creeps into my bones. The syrup alone tends to be too sweet and concentrated, so I just add water and ice to taste. Often I add sparkling water for a nice fizz. Sometimes I’ll add a few sprigs of mint to jazz it up. And at cocktail hour, a generous splash of vodka will put some swagger into your sunset.

OPTION 3: LIME SIMPLE SYRUP

Follow instructions above for lemon simple syrup, replacing the lemon juice with an equal amount of lime juice and the lemon zest with lime zest. Great in spritzers and margaritas.

OPTION 4: LAVENDER SIMPLE SYRUP

Making lavender syrup is easy—what’s not so easy is keeping the stuff around. Lavender Italian sodas were so popular at our bakery in Montpelier that we had trouble matching supply to demand! Add 4 tablespoons (25 g) crumbled dried lavender to the pot before you start heating the water and sugar according to the instructions above for plain simple syrup. Allow the lavender to steep in the syrup until it’s completely cooled, pour the syrup through a fine sieve to remove any dried lavender bits, and refrigerate.

It takes very little of the syrup to animate a drink; lavender packs a potent punch. A few spoonfuls added to sparkling water make a lovely lavender spritzer that lends a whisper of Provence to my day. My friend Ann makes a sublime lavender martini by combining lavender syrup, lavender liqueur, and vodka. She even rims the glasses with lavender sugar (she mixes dried lavender and granulated sugar in an airtight container and waits patiently until the lavender has infused the sugar with its aromatics). And for a luxurious aperitif, add a squirt of lavender syrup to the bottom of a champagne glass and pour in some bubbly.

OPTION 5: A MELLOW JITTER

(COFFEE SYRUP WITH VODKA)

What we have here is essentially a homemade Kahlúa. This is a delightful way to mellow a caffeine buzz—or to put a little buzz into your vodka mellow. Combine ¼ cup (60 ml) coffee simple syrup with a shot (or two, or three—I’m not your keeper) of vanilla vodka, and pour over ice.

OPTION 6: DOMAINE DE CANTON GIN(GER) FIZZ

Domaine de Canton is a ginger liqueur, and it’s delicious. This is a lemony-sweet cocktail with just a hint of ginger. Warning: This isn’t for the hard-core martini drinker who can’t stand a froufrou libation, but the tonic water does give the drink a hint of bitter to make it an adult beverage built for fun. Into a cocktail shaker filled with ice, pour 2 ounces (60 ml) Hendrick’s Gin, 1 ounce (30 ml) Domaine de Canton ginger liqueur, and 1 ounce (30 ml) lemon simple syrup* (page 22), and shake shake shake! Pour into two Collins glasses filled with crushed ice. Pour 5 ounces (150 ml) tonic water into each glass, give a good stir, and add a lemon wedge to each glass. Cheers!

*If you want an extra ginger kick, add 1 teaspoon (2 g) grated ginger to infuse the lemon syrup while you cook it, and strain the ginger pieces out along with the lemon zest.

OPTION 7: MARGARITA

I don’t know why tequila gets such a bum hangover rap. It’s the nectar of the gods, in my book. A margarita on the rocks, with salt on the rim and a little tequila floater to give it that punch of extra goodness—there’s nothing better on a summer night. In a cocktail shaker filled with ice, combine 2 ounces (60 ml) tequila (Gold Patron, baby!), ½ ounce (15 ml) Cointreau, and 2 ounces (60 ml) lime simple syrup (page 22), and shake shake shake! Gently moisten the lips of two margarita glasses and dunk them, one at a time, in a saucer of coarse kosher salt. Fill each glass with ice and divide the contents of the shaker between them. Add a wedge of lime to each, and if you’re feeling a little racy, top each glass with an extra splash of tequila.

I’ve already told you that you need to get yourself a candy thermometer. Yes, you can do the water method, but I’m advising you: Go get a thermometer—now. There are plenty of options out there; that’s why I have a drawer full of them. There’s the flat, traditional Taylor thermometer with a trusty black handle and a clip on the back. This is the thermometer I use the most. I do have two problems with it, though. The first is that I use it so much that the writing wears off and I can barely read the numbers. The second is that it has a gap at the bottom to keep the working end of the gauge from touching the bottom of the pan. This is a handy feature, as you want to get the temperature reading from sugar itself and not the pot. But sometimes there’s so little sugar syrup in the pot that the wee nubbin that’s meant to be suspended in the drink is hovering just above it. That’s not going to help you. In those cases, I use a digital instant-read candy thermometer. Most are just a long spike with a bulb at one end (containing the working parts) and the temperature display on top. You’ll have to hold the thermometer in the sugar yourself to make sure it doesn’t rest on the bottom of the pot, unless you can find the kind that has a really convenient clip and an adjustable reading display. The good news is that since this is an instant-read, you don’t have to sit over a steaming cauldron and melt your hand off, because it’s pretty fast and usually comes with an alarm that starts beeping when you get close to temperature. I must warn you, though, that the “instant” part is a bit of a misnomer. While the digital does read temperature faster than a traditional candy thermometer, it still takes a few seconds to go through its paces and get to the right mark.

There’s a third option, but I would advise against it: the laser-gun thermometer. I have one of these. It looks like a phaser from a 1980s sci-fimovie. You even pull a trigger, and it has a little button that lets loose a red laser beam so you can see exactly where the temperature is being read on the surface. And therein lies the problem. It reads the surface temperature, and what we want is the temperature in the middle. Surface temperature can be considerably cooler than the interior, and that can throw you off quite a bit in the world of sugar. So save your money and get the old-fashioned kind for a couple of bucks.

I suggest you calibrate your new thermometer by putting it in boiling water—I always do. Boiling water temperature is 212°F (100°C) at sea level (this temp goes down as the elevation goes up). If your thermometer reads the temperature correctly, you’re golden. If it’s slightly off, just keep that in mind and do a little math when you’re working with it. I also check periodically to see if the thermometers I’ve been using for a while are still true. Harry Potter wouldn’t be bubkes without the right wand, and so it goes with the sugar wizard and the thermometer.

This sweet caramelized milk is a nutty-brown delicacy tailor-made for all lactose-tolerant sugar babies—it’s no surprise that many a culture has their own version of and name for the glorious goo. The French (of course!) have their confiture de lait, or “milk jam.” The Argentines have their “sweet milk,” dulce de leche. How the Argentines differ from the French is that they make life incredibly convenient by skipping the whole ingredients list, poking a few holes in a can of sweetened condensed milk, and simmering it over medium-low heat in a water bath for about 3 hours. The hardest parts about this recipe are (1) waiting, and (2) remembering to make sure the can stays submerged in simmering water almost to the top of the can—otherwise it will overheat and just might explode! Oh, and (3) not burning your hand on the can when you get around to opening it. But it’s the Norwegians who had me with their version, Hamar pålegg, or “cold cut from Hamar.” Any Norwegian municipality that considers a milk-caramel spread something akin to a cold cut is my kind of town. Where are my passport and my duffel? I think I’ve just found my new home.

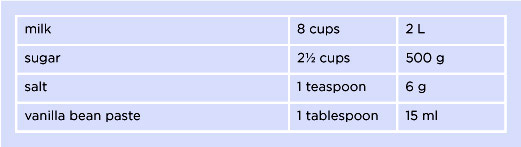

Makes approximately 2 cups (480 ml)

Fill a large stockpot a little more than halfway with water.

Fill a large stockpot a little more than halfway with water.

In a very large heatproof bowl that’s still small enough to rest inside the stockpot, combine all the ingredients and whisk them together well.

In a very large heatproof bowl that’s still small enough to rest inside the stockpot, combine all the ingredients and whisk them together well.

Place the bowl gently in the stockpot so it is surrounded almost three-quarters up the sides by water. Place the stockpot over high heat, gently and constantly stirring the contents of the floating bowl until the sugar has dissolved. Reduce the heat to medium or medium-low until the water is barely simmering.

Place the bowl gently in the stockpot so it is surrounded almost three-quarters up the sides by water. Place the stockpot over high heat, gently and constantly stirring the contents of the floating bowl until the sugar has dissolved. Reduce the heat to medium or medium-low until the water is barely simmering.

Cut a round of wax or parchment paper and place it directly on top of the simmering milk to keep a skin from forming.

Cut a round of wax or parchment paper and place it directly on top of the simmering milk to keep a skin from forming.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: Yes, hot milk forms a skin. We’ve all seen it and wondered how the hell to avoid it. First, let me tell you why it happens. The skin is formed from solid proteins that have congealed as the milk evaporates over heat. This is true of milks with fat, but non-fat milk, since it contains no fat, will not form a skin. The skin won’t disintegrate back if you stir it; you’ll have to skim it off (though this can still leave small bits behind). Constantly stirring the milk keeps the proteins from binding together to form the skin, though in the case of confiture de lait, this would require you to stand over the stove for hours. The solution is to create what’s called a “cartouche,” a parchment cover that sits directly on top of the milk, which slows the evaporation and prevents that pesky lactose epidermis from forming.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: Yes, hot milk forms a skin. We’ve all seen it and wondered how the hell to avoid it. First, let me tell you why it happens. The skin is formed from solid proteins that have congealed as the milk evaporates over heat. This is true of milks with fat, but non-fat milk, since it contains no fat, will not form a skin. The skin won’t disintegrate back if you stir it; you’ll have to skim it off (though this can still leave small bits behind). Constantly stirring the milk keeps the proteins from binding together to form the skin, though in the case of confiture de lait, this would require you to stand over the stove for hours. The solution is to create what’s called a “cartouche,” a parchment cover that sits directly on top of the milk, which slows the evaporation and prevents that pesky lactose epidermis from forming.

Continue to simmer (the lower the heat the better) for a minimum of 3 hours and up to 7 hours, until the milk caramel reduces by half, thickens to the point that it coats the back of a spoon, and is a golden brown. This is an exceedingly long time, and you must monitor the water level in the stockpot, making sure it doesn’t dip below halfway down the bowl containing the evaporating milk. Try setting an alarm to go off every half hour, and check the water level, and let it take as long as it takes.

Continue to simmer (the lower the heat the better) for a minimum of 3 hours and up to 7 hours, until the milk caramel reduces by half, thickens to the point that it coats the back of a spoon, and is a golden brown. This is an exceedingly long time, and you must monitor the water level in the stockpot, making sure it doesn’t dip below halfway down the bowl containing the evaporating milk. Try setting an alarm to go off every half hour, and check the water level, and let it take as long as it takes.

Transfer the mixture to a large, heavy-bottomed saucepan and simmer, stirring constantly, over medium-high heat. (I use a large, heatproof plastic spatula to stir this mixture—it has enough “give” to scrape along the edges, as the caramel thickens more along the sides than in the center.) Stir vigorously and constantly for 15 to 20 minutes, until the caramel thickens to the point that it “ribbons” (when you insert and remove a spoon, a ribbon of caramel appears on the surface and then disappears back into the mixture).

Transfer the mixture to a large, heavy-bottomed saucepan and simmer, stirring constantly, over medium-high heat. (I use a large, heatproof plastic spatula to stir this mixture—it has enough “give” to scrape along the edges, as the caramel thickens more along the sides than in the center.) Stir vigorously and constantly for 15 to 20 minutes, until the caramel thickens to the point that it “ribbons” (when you insert and remove a spoon, a ribbon of caramel appears on the surface and then disappears back into the mixture).

Allow the milk caramel to cool completely. Feel free to use it as a spread or a sauce on just about anything. Personally, I like to fill a pastry bag full of the stuff and squirt it into Salted Dulce de Leche Cupcakes (page 216). It can be stored in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks.

Allow the milk caramel to cool completely. Feel free to use it as a spread or a sauce on just about anything. Personally, I like to fill a pastry bag full of the stuff and squirt it into Salted Dulce de Leche Cupcakes (page 216). It can be stored in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks.

OPTION 1: SWEETENED CONDENSED MILK (DULCE DE LECHE)

With a can opener, puncture two holes into a can of condensed milk, but do not take off the entire lid. You want air to flow freely so that the can doesn’t explode during cooking but you still want to take advantage of a secure lid to keep water from penetrating the caramel.

With a can opener, puncture two holes into a can of condensed milk, but do not take off the entire lid. You want air to flow freely so that the can doesn’t explode during cooking but you still want to take advantage of a secure lid to keep water from penetrating the caramel.

Place the can in a deep saucepan and fill the saucepan with enough water that it reaches three-quarters of the way up the side of the can.

Place the can in a deep saucepan and fill the saucepan with enough water that it reaches three-quarters of the way up the side of the can.

Heat over medium-high heat until the water comes to a simmer.

Heat over medium-high heat until the water comes to a simmer.

For a pourable dulce de leche, cook for 2 hours. For a more firm dulce de leche, cook for at least 4 hours. Keep an eye on the water levels at all times, adding water about every half hour to insure that the can is submerged three-quarters of the way.

For a pourable dulce de leche, cook for 2 hours. For a more firm dulce de leche, cook for at least 4 hours. Keep an eye on the water levels at all times, adding water about every half hour to insure that the can is submerged three-quarters of the way.

OPTION 2: GOAT’S MILK CONFITURE DE LAIT

You may replace the milk in the confiture de lait recipe above with an equal amount of goat’s milk. Aside from the fact that those suffering from lactose intolerance digest goat’s milk more easily, it’s available in both regular and sweetened condensed forms, so you have the choice of making this unsurpassed delicacy either way. Goat’s milk has a distinct musky flavor, and as it evaporates with the sugar, the caramel develops a darker caramel flavor. It’s divine.

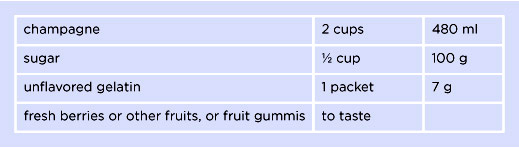

A champagne gelée—ooh la la! Sounds so fancy! If it sounds too fancy for you, how about calling it a sparkling gelée shooter? Because that’s essentially what it is. To make this dessert a presentational triumph, suspend fruits inside the setting gelée. For a more homey kick, replace the champagne with hard apple cider. Either way, it’s a spirited dessert.

Makes 1 large gelée or 6 ramekins

In a medium saucepan over medium heat, combine 1½ cups (360 ml) of the champagne and the sugar. Allow to simmer until the sugar has completely dissolved.

In a medium saucepan over medium heat, combine 1½ cups (360 ml) of the champagne and the sugar. Allow to simmer until the sugar has completely dissolved.

Pour the remaining champagne into a small bowl and sprinkle the gelatin evenly over the liquid. Allow the gelatin to bloom, which usually takes about 1 minute. It should look soggy.

Pour the remaining champagne into a small bowl and sprinkle the gelatin evenly over the liquid. Allow the gelatin to bloom, which usually takes about 1 minute. It should look soggy.

Remove the champagne mixture from the heat, scrape the gelatin mixture into the still-hot champagne, and stir until the gelatin has completely melted.

Remove the champagne mixture from the heat, scrape the gelatin mixture into the still-hot champagne, and stir until the gelatin has completely melted.

Pour the liquid gelée mixture into a 6-cup (48 oz) gelatin mold or divide evenly into 8-ounce ramekins and tap the ramekins firmly on a tabletop to release any air bubbles.

Pour the liquid gelée mixture into a 6-cup (48 oz) gelatin mold or divide evenly into 8-ounce ramekins and tap the ramekins firmly on a tabletop to release any air bubbles.

If you are planning on suspending anything in your gelée such as a heavy fruit or fruit gummis, fill the gelatin mold or each ramekin halfway and allow to set in the refrigerator; this will take up to 1 hour. Leave the remaining gelatin at room temperature. If it solidifies, gently reheat over low heat until it becomes fluid, then cool completely (otherwise, it will melt the set gelatin when you pour it over the first layer). Place your desired ingredient(s) on top of the set gelée, pour the unset gelatin evenly over the suspended ingredient(s), and refrigerate until the second layer is set. If you wish to add something lighter, such as small berries, fill the dish or the ramekins halfway and add the ingredient(s)—they’ll float to the top. Refrigerate until the gelée is set, then fill with the remaining mixture and refrigerate overnight.

If you are planning on suspending anything in your gelée such as a heavy fruit or fruit gummis, fill the gelatin mold or each ramekin halfway and allow to set in the refrigerator; this will take up to 1 hour. Leave the remaining gelatin at room temperature. If it solidifies, gently reheat over low heat until it becomes fluid, then cool completely (otherwise, it will melt the set gelatin when you pour it over the first layer). Place your desired ingredient(s) on top of the set gelée, pour the unset gelatin evenly over the suspended ingredient(s), and refrigerate until the second layer is set. If you wish to add something lighter, such as small berries, fill the dish or the ramekins halfway and add the ingredient(s)—they’ll float to the top. Refrigerate until the gelée is set, then fill with the remaining mixture and refrigerate overnight.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: I have one warning for you: Do not add fresh pineapple, kiwi, figs, guava, papaya, passion fruit, or ginger root to the gelée. All of these otherwise wonderful things contain the enzyme bromelain, which will break down the gelatin and turn the gelée runny. Cooking those fruits to 158°F (70°C) deactivates the bromelain, so canned pineapple and most commercial purées should be okay, since they are typically heat-pasteurized.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: I have one warning for you: Do not add fresh pineapple, kiwi, figs, guava, papaya, passion fruit, or ginger root to the gelée. All of these otherwise wonderful things contain the enzyme bromelain, which will break down the gelatin and turn the gelée runny. Cooking those fruits to 158°F (70°C) deactivates the bromelain, so canned pineapple and most commercial purées should be okay, since they are typically heat-pasteurized.

My mother was formidable. She was German and an opera singer, which translates into loud and occasionally scary—with an accent. So I was a kid who pretty much toed the line for fear of Helga’s wrath. With one exception: when I was in pain. And in the summer of 1981 I was in agony, reeling from the unbearable twinges of an almost-ready-to-drop-but-not-quite-there baby tooth. We were in Germany, visiting my aunt, and one of her neighbors just happened to be a dentist. I hated dentists more than I hated the nagging bicuspid torment—even Mom couldn’t begin to terrify me into the dentist’s chair. So she bribed me. With Italian gelato al limone. As many scoops as I wanted.

So I sat in Dr. Seitz’s pneumatic chair and let him manhandle my tooth. But the nanosecond he wiggled it from its perch, I demanded my gelato. Lemon. Seven scoops.

It was well worth the pain.

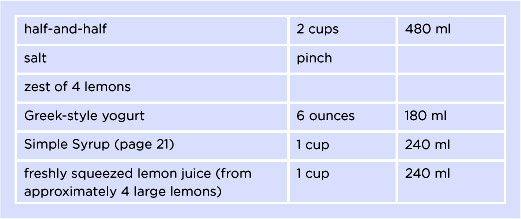

Makes 4 servings

In a large saucepan over medium-low heat, bring the half-and-half and salt to a simmer. Add the lemon zest. Turn off the heat and allow the zest to steep until the half-and-half has cooled completely.

In a large saucepan over medium-low heat, bring the half-and-half and salt to a simmer. Add the lemon zest. Turn off the heat and allow the zest to steep until the half-and-half has cooled completely.

Whisk the yogurt into the half-and-half mixture. Pour the mixture through a sieve into a clean bowl. Stir in the simple syrup and lemon juice. Cover and cool in the refrigerator overnight.

Whisk the yogurt into the half-and-half mixture. Pour the mixture through a sieve into a clean bowl. Stir in the simple syrup and lemon juice. Cover and cool in the refrigerator overnight.

Process the mixture according to the instructions on your handy-dandy ice cream machine. Or to make this more of a granita (Italian-style flavored ice), after the mixture has refrigerated until cool, at least 2 hours or overnight, freeze it for 1 hour in a roasting pan or large bowl. Remove it from the freezer, and using two forks, scrape the mixture to break up the ice. Freeze for 3 to 4 hours longer, until completely frozen. Serve!

Process the mixture according to the instructions on your handy-dandy ice cream machine. Or to make this more of a granita (Italian-style flavored ice), after the mixture has refrigerated until cool, at least 2 hours or overnight, freeze it for 1 hour in a roasting pan or large bowl. Remove it from the freezer, and using two forks, scrape the mixture to break up the ice. Freeze for 3 to 4 hours longer, until completely frozen. Serve!

Crème anglaise is the mother of pastry sauces—if you know your anglaise, you’ve already got a handle on crème pâtissière (pastry cream), sabayon, ice cream, crème brûlée, and pot de crème. Use her as a sauce on a dessert or as the creamy sea in the buoyant beauty Île Flottante (page 174). Dredge slices of brioche in her and fry up the breakfast food that puts the French in toast, pain perdu (page 33). Or just dip a spoon into a bowl of this English cream and enjoy it as the sweetest, most sublime, and most arterially congestive soup you’ve ever savored. This recipe is easily doubled, tripled, or quadrupled. You simply need to find the corresponding pot large enough to hold your batch.

Makes 1¾ to 2 cups (420 to 480 ml)

In a large, heavy saucier over medium heat, bring the half-and-half to a simmer.

In a large, heavy saucier over medium heat, bring the half-and-half to a simmer.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: For cream sauces like crème anglaise or pastry cream, I always use a saucier pan. The sloping sides allow for much easier whisking and help prevent the cream from thickening and hiding in the corners, thereby creating a more consistent sauce.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: For cream sauces like crème anglaise or pastry cream, I always use a saucier pan. The sloping sides allow for much easier whisking and help prevent the cream from thickening and hiding in the corners, thereby creating a more consistent sauce.

Meanwhile, in an electric mixer fitted with the whisk attachment, beat the egg yolks, sugar, vanilla paste, and salt until light and fluffy.

Meanwhile, in an electric mixer fitted with the whisk attachment, beat the egg yolks, sugar, vanilla paste, and salt until light and fluffy.

With the mixer running on medium speed (to reduce any splashing), slowly pour ¼ cup (60 ml) of the hot half-and-half mixture along the side of the bowl into the egg mixture, to temper the eggs. Mix for 30 seconds, then pour the remaining half-and-half mixture very slowly down the side of the bowl into the whisking egg mixture.

With the mixer running on medium speed (to reduce any splashing), slowly pour ¼ cup (60 ml) of the hot half-and-half mixture along the side of the bowl into the egg mixture, to temper the eggs. Mix for 30 seconds, then pour the remaining half-and-half mixture very slowly down the side of the bowl into the whisking egg mixture.

Beat until all the ingredients are well combined. The mixture won’t thicken much at this point; it will be quite watery and probably a little foamy. Transfer the liquid back into the saucier, taking care to scrape down the sides of the mixing bowl.

Beat until all the ingredients are well combined. The mixture won’t thicken much at this point; it will be quite watery and probably a little foamy. Transfer the liquid back into the saucier, taking care to scrape down the sides of the mixing bowl.

Place the saucier over medium-low heat. Whisk constantly and vigorously until the mixture thickens and coats the back of a spoon. You may attach a thermometer to the side of the pan to ensure that the temperature rises above 160°F (71°C) to kill all potential bacteria. However, the thermometer bulb will impede efficient whisking and will allow cream to thicken in that area. So if this allays your fears at all, know that I’ve taken the temperature of a finished anglaise 5 minutes after I’ve transferred it into a container for cooling and the temperature still read above 160°F (71°C).

Place the saucier over medium-low heat. Whisk constantly and vigorously until the mixture thickens and coats the back of a spoon. You may attach a thermometer to the side of the pan to ensure that the temperature rises above 160°F (71°C) to kill all potential bacteria. However, the thermometer bulb will impede efficient whisking and will allow cream to thicken in that area. So if this allays your fears at all, know that I’ve taken the temperature of a finished anglaise 5 minutes after I’ve transferred it into a container for cooling and the temperature still read above 160°F (71°C).

Use immediately or store in an airtight container for up to 2 days.

Use immediately or store in an airtight container for up to 2 days.

OPTION 1: PAIN PERDU

As I said earlier, crème anglaise is the batter that makes pain perdu happen. Get your hands on a loaf of brioche or an equally luscious sweet bread, like challah. (Even better, bake some.) I’ve also used leftover Christmas Panettone (page 197) for the best French/Italian breakfast mash-up I’ve ever eaten.

Simply cut your bread into slices about 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick. Pour the crème anglaise into a shallow pan (I find a pie plate works beautifully). Lay the pieces in the sauce just long enough for the cream to soak in. Flip each slice so that both sides are coated.

Place 2 tablespoons (30 ml) butter in a hot pan and when the butter has melted, fry the cream-soaked pieces of bread over medium to medium-high heat until both sides are golden brown. Enjoy with luscious maple syrup or sprinkled with a touch of confectioners’ sugar for breakfast, or serve with a scoop of ice cream for a delectable dessert.

OPTION 2: FRENCH/AMERICAN BUTTERCREAM

I was teaching a class at King Arthur Flour, demonstrating how to make Italian buttercream, when one of my students asked me, “Have you ever made custard icing? It’s similar but less sweet.” I hadn’t. I’d never even heard of it. I, the woman-child who lives for creamy fillings, had gone my entire life without getting acquainted with what sounded like my frosting soulmate. Of course I made up for lost time by going home and experimenting immediately. And oh. My. Goodness. Where had this stuff been all my life? This is the cake filling I’d been longing for since I learned the word “cake” (in utero, of course). I use it in the Red Sox Nation Tortes (page 201), my alternative to Boston cream pie.

There are a few differences in the base cream from the crème anglaise. First, have 1 pound (455 g) unsalted butter ready at room temperature to transform this cream into a spreadable love fest. Then, replace the yolks with whole eggs and the half-and-half with whole milk, and add ¼ cup (30 g) of cornstarch to the eggs and sugar. Continue as you would with the anglaise: Whip the eggs, sugar, and cornstarch until fluffy, then add the hot milk.

Because we’ve added cornstarch to the mixture, it will thicken far more during the whisking than traditional crème anglaise. You’ll be looking for very thick, smooth custard. Once you’ve gotten the right consistency, transfer the finished custard back into the mixer and beat on high with a paddle attachment until the bowl is cool to the touch. Add your softened (not melted) butter a chunk at a time until it’s all incorporated. You’ll notice the mixture thickening considerably. If you add too soft a butter or you don’t let the cream cool enough, the icing won’t thicken. If you’ve gotten yourself in this situation, just place the bowl in the fridge for 10 to 15 minutes and start mixing again.

OPTION 3: POT DE CRÈME

Pot de crème has to be the most genteel comfort dessert known to humanity. It’s a warm, elegant pudding traditionally cooked and presented in an adorable little ceramic pot with a lid. As in the buttercream above, the egg yolks in the crème anglaise recipe are replaced by whole eggs; otherwise the ingredients remain the same. The difference is that after the crème is heated and thickened to the point of coating the back of your spoon, you divide the mixture among your little pots, making sure to skim off any foam that’s on the surface that might mar the finished product after it’s baked (it should be smooth and glossy when finished). I double the anglaise recipe for 4 portions.

Preheat the oven to 350°F (175°C). Fill your pot de crème pots (or ramekins, if you don’t have the sweet little things) halfway (using only half your anglaise) and place the pots in a large, high-walled, ovenproof pan. (A deep hotel pan is perfect; otherwise I use a large, oblong glass baking dish.) Carefully add hot water to the pan, so that the water reaches halfway up the pot de crème containers but none of the water sloshes into the pots de crème themselves.

Pull an oven rack out as far as it will safely go and still hold the weight of your baking pan, and carefully transfer the pan to the rack. (If you feel confident you can transfer the dish and your little pots into the oven once they are filled, be my guest. I know from experience and unsteady hands that I’ve never managed this without an accident.) Fill each pot de crème with the remaining crème mixture. If you have official pot de crème pots, put the lids on now. If you don’t, cover the entire pan with aluminum foil.

Bake for 25 minutes, or until the custard is set; the time will vary depending on the size of your containers. Serve immediately.

For chocolate pot de crème, add ¼ cup (60 ml) bittersweet chocolate morsels to the crème just as you’ve taken it off the heat. Let the mixture sit for 5 minutes, then whisk until the chocolate is completely melted and incorporated. Divide among the pots as you would for the standard version.

OPTION 4: CRÈME BRÛLÉE

The difference between the base cream in crème anglaise and crème brûlée is that whole eggs replace the yolks, just as in the American buttercream and the pot de crème. The initial procedure is also the same. Whisk until the mixture is thick enough to coat the back of a spoon.

The baking procedure is exactly the same as for pot de crème, only using a shallow ramekin because you want that larger surface area to caramelize the sugar at the end. Bake at 350°F (175°C) for 25 minutes, or until the crème has set. Allow to cool to room temperature and then refrigerate until chilled.

To finish, sprinkle granulated sugar in an even layer over the entire surface of the custard. Caramelize the sugar by gently passing a kitchen torch over the sugar until it starts to brown and bubble, using even strokes and making sure not to burn the sugar, but melting it enough to form a hard outer layer that you have to break through to get to the creamy goodness within.

OPTION 5: OLIVE OIL CREEMEE

Ray and I spent Holy Saturday eating our way through Chicago. We stopped for lunch at the Purple Pig. We settled at the sumptuous marble bar and ordered wine while we perused the pork menu, rubbernecked as the waiters brought around splendid bacon-infused temptations. Despite all these glorious porky delights, it was a Taylor tabletop soft-serve machine that hypnotized me throughout the meal.

A Vermonter by choice, I’ve unabashedly adopted the local obsession with the seasonal soft-serve, the creemee. And most creemees of note are dispensed from a Taylor. The season wouldn’t hit Vermont for a few more months and yet here, sitting directly across from me and taking up a large portion of the bartender’s workstation, was a top-of-the-line and resplendently gleaming soft-serve delivery system. Pork-infused lunch be damned—I wanted dessert, stat.

While Vermont specializes in the delicious and very locally inspired maple creemee, the Purple Pig was feeling its influences from elsewhere: Italy, to be exact. And on that day, I sampled my very first olive oil ice cream. I resolved to bring this wonderful delight back to the Green Mountains and the creemee-loving masses.

For two generous servings of ice cream: Make a double batch of crème anglaise, but in the first step, add ¼ cup (60 ml) olive oil to the half-and-half. Once the sauce has begun to thicken, set the saucepan in a large bowl of ice and continue whisking until the sauce has cooled completely. Add 1 cup (240 ml) whole milk and continue whisking.

Pour the cooled mixture into an ice cream maker and proceed per the manufacturer’s instructions. For a lovely dessert pairing, try a Strawberry Basil Napoleon (page 187)—it will mesh beautifully with the olive oil flavors.

For a chocolate ice cream variation, replace the olive oil with 1/2 cup (40 g) cocoa powder.

Crème caramel is a kissing cousin to crème anglaise, a sexy little custard cooked in a caramel bath and upended so that the amber syrup flows around it to form a pool of luscious sweetness. This dessert minx also goes by the alias “flan.”

Makes 4 servings

PROCEDURE FOR THE CARAMEL

In a heavy-bottomed saucepan over medium heat, combine the sugar, water, and lemon juice, stirring constantly with a wooden spoon. The sugar will melt and caramelize quickly, so keep stirring and adjusting the heat; you want the sugar to melt evenly and to have a golden brown color. Make sure your lighting is very good, because it can be hard to see the exact hue of your caramel.

In a heavy-bottomed saucepan over medium heat, combine the sugar, water, and lemon juice, stirring constantly with a wooden spoon. The sugar will melt and caramelize quickly, so keep stirring and adjusting the heat; you want the sugar to melt evenly and to have a golden brown color. Make sure your lighting is very good, because it can be hard to see the exact hue of your caramel.

When the color reaches a dark amber, immediately remove the saucepan from the heat and gently place it over the ice water to stop the caramelization process. Take care not to splash any water into your caramel.

When the color reaches a dark amber, immediately remove the saucepan from the heat and gently place it over the ice water to stop the caramelization process. Take care not to splash any water into your caramel.

Immediately spoon a small amount of caramel into each of four 8-ounce ramekins and swirl to create an even layer. Set aside.

Immediately spoon a small amount of caramel into each of four 8-ounce ramekins and swirl to create an even layer. Set aside.

PROCEDURE FOR THE CUSTARD

Preheat the oven to 350°F (175°C).

Preheat the oven to 350°F (175°C).

In a large saucepan over medium-low heat, bring the milk, salt, and vanilla paste just to a simmer.

In a large saucepan over medium-low heat, bring the milk, salt, and vanilla paste just to a simmer.

In the bowl of an electric mixer on medium speed, beat the sugar and eggs.

In the bowl of an electric mixer on medium speed, beat the sugar and eggs.

Slowly pour the hot milk mixture along the side of the bowl and into the eggs. Whisk until well combined.

Slowly pour the hot milk mixture along the side of the bowl and into the eggs. Whisk until well combined.

Return the sauce to the saucepan over medium heat and whisk until the mixture thickens to the point that it just coats the back of a spoon.

Return the sauce to the saucepan over medium heat and whisk until the mixture thickens to the point that it just coats the back of a spoon.

Strain the custard mixture. I prefer to strain the custard into a large measuring cup with a spout to make pouring easier.

Strain the custard mixture. I prefer to strain the custard into a large measuring cup with a spout to make pouring easier.

Place the ramekins in a deep baking dish (I use a casserole dish or a deep brownie pan) and place the baking dish on a sheet pan. At this point you can proceed on a kitchen counter-top if you have steady hands, or you can choose to pull an oven rack out far enough to use that as a work surface. In the latter case, you have to work quickly to keep the temperature of the oven from dipping too low. If this is how you choose to proceed, increase the oven temperature to 375°F (190°C), and once you’re done filling the ramekins and the water bath, turn the temperature down to 350°F (175°C).

Place the ramekins in a deep baking dish (I use a casserole dish or a deep brownie pan) and place the baking dish on a sheet pan. At this point you can proceed on a kitchen counter-top if you have steady hands, or you can choose to pull an oven rack out far enough to use that as a work surface. In the latter case, you have to work quickly to keep the temperature of the oven from dipping too low. If this is how you choose to proceed, increase the oven temperature to 375°F (190°C), and once you’re done filling the ramekins and the water bath, turn the temperature down to 350°F (175°C).

Pour the custard mixture evenly into the ramekins, to just below the tops.

Pour the custard mixture evenly into the ramekins, to just below the tops.

Pour hot water in the baking dish to create a bath for the ramekins. The water should reach about three-quarters up the outside of the ramekins. Pour the water slowly so that it doesn’t splash into the custard. Carefully place the baking dish inside the oven.

Pour hot water in the baking dish to create a bath for the ramekins. The water should reach about three-quarters up the outside of the ramekins. Pour the water slowly so that it doesn’t splash into the custard. Carefully place the baking dish inside the oven.

Bake for 30 to 40 minutes, until set.

Bake for 30 to 40 minutes, until set.

Remove from the oven and allow to cool completely at room temperature. You can keep the ramekins in the water bath—they will cool more slowly, but it’s safer than pulling hot ramekins from scalding water with clunky oven mitts. Transfer the ramekins to the refrigerator to chill for several hours.

Remove from the oven and allow to cool completely at room temperature. You can keep the ramekins in the water bath—they will cool more slowly, but it’s safer than pulling hot ramekins from scalding water with clunky oven mitts. Transfer the ramekins to the refrigerator to chill for several hours.

To unmold the crème caramel, slowly and evenly run a very thin paring knife along the inside edge of each ramekin, keeping the knife flat against the edge to keep from cutting into the custard. Place a plate on top of each ramekin and invert the two together so that the ramekin is sitting upside down on the plate. Gently shake the ramekin, keeping it close to the plate, until it slides out.

To unmold the crème caramel, slowly and evenly run a very thin paring knife along the inside edge of each ramekin, keeping the knife flat against the edge to keep from cutting into the custard. Place a plate on top of each ramekin and invert the two together so that the ramekin is sitting upside down on the plate. Gently shake the ramekin, keeping it close to the plate, until it slides out.

Serve with berries and whipped cream.

Serve with berries and whipped cream.

Have you heard about the lady who married the Eiffel Tower? That’s just crazy, right? Everyone knows you don’t marry inanimate objects unless you can eat them. For instance, if I could marry pastry cream, I would. It’s delicious. It’s versatile. It’s gotten me out of baking jams. It’s opened up the world of pastry for me. If you learn one thing, learn to make pastry cream. And learn to make it well. You won’t be disappointed.

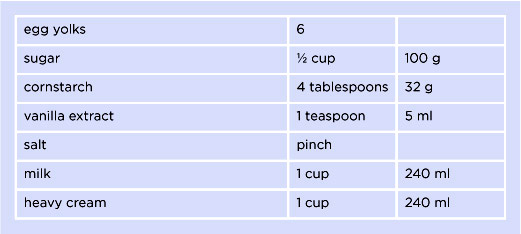

Makes approximately 2¼ cups (540 ml)

Place the egg yolks, sugar, cornstarch, vanilla extract, and salt in the bowl of an electric mixer with a whisk attachment. Beat the mixture on high until light and fluffy.

Place the egg yolks, sugar, cornstarch, vanilla extract, and salt in the bowl of an electric mixer with a whisk attachment. Beat the mixture on high until light and fluffy.

Meanwhile, in a heavy saucier, mix the milk and cream together. Place the saucier over medium-high heat and bring the mixture to a rolling boil.

Meanwhile, in a heavy saucier, mix the milk and cream together. Place the saucier over medium-high heat and bring the mixture to a rolling boil.

Decrease the mixer speed to medium and carefully pour the hot milk mixture down the side of the bowl. You need to lower the speed to prevent splashing, but you must add the milk mixture while the egg mixture is in motion to prevent the hot liquid from scalding the eggs. (Note: Keep the saucier on hand—you’ll need it again. You want it perfectly clean when you transfer the unthickened pastry cream back into it—make sure there’s no browned milk sludge on the bottom of the pan.)

Decrease the mixer speed to medium and carefully pour the hot milk mixture down the side of the bowl. You need to lower the speed to prevent splashing, but you must add the milk mixture while the egg mixture is in motion to prevent the hot liquid from scalding the eggs. (Note: Keep the saucier on hand—you’ll need it again. You want it perfectly clean when you transfer the unthickened pastry cream back into it—make sure there’s no browned milk sludge on the bottom of the pan.)

Once all the milk mixture is incorporated, slowly increase the mixer speed and let it run for about 1 minute. Stop the mixer, scrape down the sides and bottom of the bowl to ensure that all vestiges of egg, cornstarch, and sugar are completely incorporated, and transfer the contents of the mixing bowl to your clean saucier.

Once all the milk mixture is incorporated, slowly increase the mixer speed and let it run for about 1 minute. Stop the mixer, scrape down the sides and bottom of the bowl to ensure that all vestiges of egg, cornstarch, and sugar are completely incorporated, and transfer the contents of the mixing bowl to your clean saucier.

Before you take your liquidy pastry cream back to the stove to thicken, make sure you have a clean bowl and a fine sieve at the ready. You’re going to be pouring the finished mixture through the sieve and into the bowl the moment the mixture is done.

Before you take your liquidy pastry cream back to the stove to thicken, make sure you have a clean bowl and a fine sieve at the ready. You’re going to be pouring the finished mixture through the sieve and into the bowl the moment the mixture is done.

Return to the stove with your saucier. Clip a candy thermometer to the side of the saucier if you’re anxious about the temperature reaching 160°F (71°C)—the official temperature for killing pesky bacteria—but I can assure you it will, and then some.

Return to the stove with your saucier. Clip a candy thermometer to the side of the saucier if you’re anxious about the temperature reaching 160°F (71°C)—the official temperature for killing pesky bacteria—but I can assure you it will, and then some.

Over medium-high heat, vigorously whisk the mixture until it has thickened, 4 to 5 minutes. You may break a sweat, but don’t ever stop whisking, and make sure your whisk is getting to the bottom and along the sides of the saucepan—this stuff can burn easily.

Over medium-high heat, vigorously whisk the mixture until it has thickened, 4 to 5 minutes. You may break a sweat, but don’t ever stop whisking, and make sure your whisk is getting to the bottom and along the sides of the saucepan—this stuff can burn easily.

You’ll notice that you’re stirring for an awful long time before you see much change. But I warn you, it will happen, and all at once. Most often the thickening begins in earnest at the edges of the pan; get to that thickening portion with your whisk and stir it into the thinner portion.

You’ll notice that you’re stirring for an awful long time before you see much change. But I warn you, it will happen, and all at once. Most often the thickening begins in earnest at the edges of the pan; get to that thickening portion with your whisk and stir it into the thinner portion.

Once the pastry cream has thickened enough to coat the back of a spoon and then some—it should be the consistency of mayonnaise—take the saucier off the heat and pour the pastry cream through the sieve into a clean bowl. (You may get lucky and have smooth and luscious pastry cream—if so, feel free to forego the sieving. Otherwise, why not take every precaution to make it super smooth?) Use a rubber spatula to speed the process along by pressing the pastry cream through the sieve. Once you’ve got every last drop in your bowl, give a quick stir for good measure.

Once the pastry cream has thickened enough to coat the back of a spoon and then some—it should be the consistency of mayonnaise—take the saucier off the heat and pour the pastry cream through the sieve into a clean bowl. (You may get lucky and have smooth and luscious pastry cream—if so, feel free to forego the sieving. Otherwise, why not take every precaution to make it super smooth?) Use a rubber spatula to speed the process along by pressing the pastry cream through the sieve. Once you’ve got every last drop in your bowl, give a quick stir for good measure.

Take a piece of plastic wrap that’s larger in diameter than your bowl and place it directly on the surface of the pastry cream. Make sure that every last bit of pastry cream is touching the plastic; otherwise it will form a skin. Transfer the bowl to the refrigerator to cool completely. (While you wait, you can daydream about what you want to create with your gorgeous pastry cream. Pumpkin éclairs, anyone?)

Take a piece of plastic wrap that’s larger in diameter than your bowl and place it directly on the surface of the pastry cream. Make sure that every last bit of pastry cream is touching the plastic; otherwise it will form a skin. Transfer the bowl to the refrigerator to cool completely. (While you wait, you can daydream about what you want to create with your gorgeous pastry cream. Pumpkin éclairs, anyone?)

Once your pastry cream is cool, you’ll notice that it’s considerably thicker than when you saw it last. This is normal. Pastry cream keeps for about 2 days in the refrigerator.

Once your pastry cream is cool, you’ll notice that it’s considerably thicker than when you saw it last. This is normal. Pastry cream keeps for about 2 days in the refrigerator.

OPTION 1: FLAVORS

Pastry cream is unbelievable in its natural state. It’s a damn shame to mess with it—but I do! For an Asian-inspired delicacy, add 4 tablespoons (12 g) matcha (powdered green tea) just after you’ve sieved the stuff and right before you give it a final stir. For a coffee infusion, add 1 tablespoon (3 g) espresso powder to the milk and cream when you first heat it. Or add ½ cup (120 ml) ganache for a gorgeous chocolaty custard, ½ cup (120 ml) lemon curd for a citrus zing, or ½ cup (120 ml) pumpkin purée for a warm autumnal variation. For each of these, stir the flavor addition in during the last step.

You can also experiment with fruit purées and other fruit flavorings. I keep an array of Italian soda flavorings handy—especially banana—for those occasions when I need a splash of unusual yet natural flavor. Add ½ cup (120 ml) purée or Italian soda flavor to the pastry cream just before refrigerating, whisking briskly to distribute the flavor evenly.

OPTION 2: LIGHTENING

Pastry cream is often “lightened,” which is a circuitous way of saying “add whipped cream.” Per 1 cup (240 ml) chilled pastry cream, fold in ½ cup (120 ml) chilled whipped cream for a lighter, airier texture. Conversely, if you like to layer cakes with sweetened whipped cream, consider adding a touch of pastry cream.

OPTION 3: FILLING

Pastry cream is a workhorse. You can use if for so much more than the inside of a cream puff. (But goodness, it sure is tasty in a cream puff.) Take three layers of vanilla cake and smooth chilled pastry cream between them. Top with chocolate ganache, and you’ve made a Boston cream pie. Or fry up a Berliner doughnut and fill the inside with pastry cream. Add ganache to a pastry cream and you have a chocolaty filling for any cake.

Do you like banana cream pie? Coconut cream pie? Chocolate cream pie? Well, hell, any cream pie? Then go make a yummy pie shell and while it’s cooling, make some pastry cream. There are some wonderful flavored syrups: Fabri and Monin are both brands I love—they use natural flavors and their syrups taste phenomenal. Add just enough—about ¼ cup (60 ml)—banana- or coconut-flavored syrup to your pastry cream, and over a layer of bananas or toasted coconut, add 2 cups (480 ml) flavored pastry cream directly to your baked and cooled pie shell. Take an additional 2 cups (480 ml) pastry cream and fold in 1 cup (240 ml) whipped heavy cream; with this you can pipe lovely designs on top of the pastry cream layer. If you have puff pastry on hand, you can make Napoleons with your lightened pastry cream.

OPTION 4: FROZEN CUSTARD

If you want to make frozen custard, follow the instructions for Pastry Cream through step 9. Instead of step 10, pour the mixture through a sieve into a bowl that’s sitting atop another bowl filled with ice and stir until the pastry cream is completely cold. Add 1 cup (240 ml) whole milk and combine well. Transfer the mixture to an ice cream machine and process according to manufacturer’s instructions. Best vanilla-custard ice cream ever!

OPTION 5: BAKE!

That’s right—bake with pastry cream. I add ½ cup (120 ml) to my apple pie filling. Really! It’s phenomenal. If I’m making a strudel, 1 cup (240 ml) pastry cream added to the filling makes it creamy and luxurious. The great thing about pastry cream is that although you can’t use it after 2 days for applications like adding it to whipped cream or as a layer in a cake, you can bake with it for up to 1 week. It lends creaminess to pastries, it can elevate any humdrum pie filling, and it’s what makes bread pudding absolutely divine. So don’t despair if you’ve forgotten the pastry cream in the fridge; it’s got endless uses in your oven.

This is a lazy person’s Bavarian cream, using pastry cream that’s been in the fridge with no other use. This is also very close to something called “diplomat cream.” It’s a fantastic alternative for cake filling, or is delicious served by itself as a quasi-mousse dessert.

Makes 3½ cups (840 ml) filling or 6 dessert servings

Place the purée and water in a small microwavable bowl. Sprinkle the gelatin over the purée and allow it to bloom for several minutes (until it all looks soggy).

Place the purée and water in a small microwavable bowl. Sprinkle the gelatin over the purée and allow it to bloom for several minutes (until it all looks soggy).

Microwave the gelatin for 20 seconds on high and then stir. Continue to microwave in 20-second intervals until the gelatin has dissolved completely.

Microwave the gelatin for 20 seconds on high and then stir. Continue to microwave in 20-second intervals until the gelatin has dissolved completely.

Add a heaping spoon of the whipped cream to the gelatin mixture and stir to temper the gelatin. (Tempering simply means adjusting the gelatin to a cooler temperature so that it doesn’t seize when you add it to the final mixture.)

Add a heaping spoon of the whipped cream to the gelatin mixture and stir to temper the gelatin. (Tempering simply means adjusting the gelatin to a cooler temperature so that it doesn’t seize when you add it to the final mixture.)

In an electric mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, beat the pastry cream until it becomes loose and creamy.

In an electric mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, beat the pastry cream until it becomes loose and creamy.

Using a plastic spatula, fold the remaining whipped cream into the pastry cream. Quickly fold the gelatin mixture into the lightened pastry cream until it is evenly distributed. Use as a filling in a layer cake or divide among 6 serving glasses for individual mousses.

Using a plastic spatula, fold the remaining whipped cream into the pastry cream. Quickly fold the gelatin mixture into the lightened pastry cream until it is evenly distributed. Use as a filling in a layer cake or divide among 6 serving glasses for individual mousses.

Chill individual mousses in the refrigerator overnight before serving. If you are using the Bavarian cream as a cake filling, place the finished product (the assembled cake) in the freezer for a few hours or overnight to allow the gelatin to set completely. Three hours before serving, place it in the refrigerator to thaw.

Chill individual mousses in the refrigerator overnight before serving. If you are using the Bavarian cream as a cake filling, place the finished product (the assembled cake) in the freezer for a few hours or overnight to allow the gelatin to set completely. Three hours before serving, place it in the refrigerator to thaw.

“Curd” is such an unfortunate word. It really does an incredibly delicious treat such a disservice. The English slather the citrusy stuff on scones. I love to add it in between layers of coconut cake, or I’ll fill a sweet tart shell with a few cups of it and top it with meringue for the best lemon tart you’ll ever taste. Another option is to eat it by the spoonful. I won’t judge.

Makes 2½ cups (600 ml)

In a heatproof metal bowl, combine the ½ cup (120 ml) lemon juice, agave nectar, and egg yolks.

In a heatproof metal bowl, combine the ½ cup (120 ml) lemon juice, agave nectar, and egg yolks.

In a separate bowl, sprinkle the gelatin on top of the remaining 2 tablespoons (30 ml) lemon juice until it blooms, or, in other words, looks soggy. Set aside.

In a separate bowl, sprinkle the gelatin on top of the remaining 2 tablespoons (30 ml) lemon juice until it blooms, or, in other words, looks soggy. Set aside.

Place the bowl with egg mixture over a simmering pot of water and whisk until it has thickened enough that it ribbons when you pull out the whisk. Remove from the heat; immediately add the gelatin and whisk until it’s completely melted. Add the butter and zest and whisk until fully incorporated. The temperature will have risen above 160°F (71°C) by this time—I’ve checked—but if you’re nervous, work with a thermometer for your own peace of mind.

Place the bowl with egg mixture over a simmering pot of water and whisk until it has thickened enough that it ribbons when you pull out the whisk. Remove from the heat; immediately add the gelatin and whisk until it’s completely melted. Add the butter and zest and whisk until fully incorporated. The temperature will have risen above 160°F (71°C) by this time—I’ve checked—but if you’re nervous, work with a thermometer for your own peace of mind.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: Like pastry cream, lemon curd takes a good long while to thicken. But it gives you some warning signs that it’s about to turn. First, it starts to get foamy and lightens in color from a deep, egg-yolk yellow to a light, butter yellow. Just keep whisking. Then the foam starts to dissipate. Keep whisking. Then it thickens. STOP!

A Note from the Sugar Baby: Like pastry cream, lemon curd takes a good long while to thicken. But it gives you some warning signs that it’s about to turn. First, it starts to get foamy and lightens in color from a deep, egg-yolk yellow to a light, butter yellow. Just keep whisking. Then the foam starts to dissipate. Keep whisking. Then it thickens. STOP!

Transfer the curd to a bowl. Take a piece of plastic wrap that’s larger in diameter than the bowl and place it directly on the surface of the curd. Make sure the plastic touches the entire surface of the exposed curd; otherwise a skin will form. Refrigerate for a few hours until it’s completely cool. Store in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to a week.

Transfer the curd to a bowl. Take a piece of plastic wrap that’s larger in diameter than the bowl and place it directly on the surface of the curd. Make sure the plastic touches the entire surface of the exposed curd; otherwise a skin will form. Refrigerate for a few hours until it’s completely cool. Store in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to a week.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: You’ll notice I use gelatin, which isn’t a necessary addition to curd if you are planning to use it as a simple spread on scones. However, I like to use it as a filling in pastries, and the addition of gelatin gives me a measure of assurance that the curd will set up firmly so that it stays neatly within the confines of the pastry instead of oozing out.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: You’ll notice I use gelatin, which isn’t a necessary addition to curd if you are planning to use it as a simple spread on scones. However, I like to use it as a filling in pastries, and the addition of gelatin gives me a measure of assurance that the curd will set up firmly so that it stays neatly within the confines of the pastry instead of oozing out.

Making maple syrup is more of a North Country adventure than an actual recipe.

First, get a giant maple tree. Second, tap the tree in April, just as the days get above 40°F (8°C) but making damn sure it falls below 32°F (0°C) at night. Third, hang buckets from the tap and collect sap. Fourth, boil your gallons of syrup down to a thimbleful of syrup and pray you don’t overheat the stuff or it’ll be useless.

That’s sugaring in a nutshell. “Sugaring” is the term used by insane Northern folk who, just as winter breaks, spend their days collecting gallons of sap and boiling those gallons down to just a few cups. To be exact, you need forty to fifty gallons of sap to make one measly gallon of syrup.

Let’s say you manage to collect that much sap. So your ingredients are:

50 gallons of sap

You’ll notice that in a lineup, sap could pass for water. It’s clear, it’s free flowing without a hint of syrupy thickness, and it’s barely sweet. Which leads me to wonder, as I so often do when I think about how food creations came to be, who the hell thought to boil down this innocuous stuff until it became liquid pancake gold?

You do get some sense of the impulse to do something when you first tap a maple in prime sugaring season. Drill a little pilot hole at a slight angle, and a good maple will instantly start oozing sap; you feel compelled to either plug the hole or find something in which to collect the bounty. So now you have to follow some procedure to transform what could very well be water into New England wine.

I was in this very position in the spring of 2010 when my husband, Ray, and I tapped our first maples. We have a handful of two-hundred-plus-year-old trees on our property and, being the good Vermonters we’re trying to be, we had to tap those puppies. The weather wasn’t complying with us when we first drilled our tap holes; it wasn’t warming up sufficiently in the afternoon to heat the tree “just so” in order to get her running. So we went on a short weekend trip and left our beloved friend and native Vermonter Agnes in charge of our peculiar pack of hounds and what seemed to be a dormant pack of maple trees. “Don’t worry much about the sap, Agnes. We’ve barely seen a few drops in the buckets.”

Naturally this kind of flippant statement could only lead to a perfect storm of sap weather, leaving Agnes on a desperate hunt for ever larger buckets in the barn, in the shed, in the stables, and, finally, in the bakery. When we returned to Vermont, and I swear we were only gone three days, Agnes introduced us to the new members of our family: fifty gallons of sap collected in all manner of containers waiting patiently in my bakery cooler. Presenting our liquid offspring, Agnes added, “And you have to boil it off right away because it sours fast. Like milk. Just worse.”

Here’s where the procedure comes in. The rule of thumb in sugaring is that you boil sap until you reach a temperature of exactly 7.1°F (3.9°C) over the boiling point at your particular elevation (or if you have a fancy-schmancy sugar-concentration reader, it’s 66–67 percent sugar concentration). You see, the temperature of boiling water is 212°F (100°C) at sea level; this temperature gets lower, however, as elevation increases and atmospheric pressure decreases. So you may think the correct temperature for perfect maple syrup is 219.1°F (103.9°C)—but where I live, it’s 217°F (102.8°C). I know this because I boiled my first batch to 219.1°F (103.9°C) and as it cooled, it started to form a mountain range of crystals perfectly suitable for a family of sea monkeys but not at all the stuff of maple syrup. Thankfully, I am the Sugar Baby that I am and I just made maple candy with the disaster (after I stopped crying).

In the end, after harvesting about a hundred gallons of sap, we were left with a Nutella jar full of maple syrup. But my oh my, what delicious maple syrup it was.

There’s no cake, no Parisian macaron complete without this luscious stuff, and the varieties are endless—vanilla bean, caramel, blackberry, maple, and more. There are two ways to make the real deal. This is the first way, the Swiss way. The second is the Italian way (page 63). Both results are wonderful—it’s simply a matter of procedural preference. I also believe that Swiss buttercream gives you a bit more assurance in terms of killing any food-borne buggers that could be hiding in your raw egg whites, since you heat the egg whites to 160°F (71°C).

Makes enough to fill and lightly cover 1 (10-inch/25-cm) cake

In the bowl of an electric mixer, add the egg whites, sugar, salt, vanilla bean seeds, and vanilla extract. Place the bowl over a bain-marie (a simmering saucepan of water). Clip on a candy thermometer and whisk constantly until the sugar has completely dissolved (I stick two fingers in and rub to see if I feel any granules) and the temperature has reached 160°F (71°C). Immediately transfer the bowl to the mixer and whisk on high until the mixture holds soft peaks and the bowl no longer feels hot to the touch.

In the bowl of an electric mixer, add the egg whites, sugar, salt, vanilla bean seeds, and vanilla extract. Place the bowl over a bain-marie (a simmering saucepan of water). Clip on a candy thermometer and whisk constantly until the sugar has completely dissolved (I stick two fingers in and rub to see if I feel any granules) and the temperature has reached 160°F (71°C). Immediately transfer the bowl to the mixer and whisk on high until the mixture holds soft peaks and the bowl no longer feels hot to the touch.

A Note from the Sugar Baby: At the end of step 1, you’ve got meringue. The same holds true for Italian meringue, when you’re on the road to making buttercream but you’ve only reached the point of whipping the egg whites and the sugar together to form peaks. If you stopped right now, you could fill a pastry bag, pipe soft white mountains onto the top of a pie, and use a kitchen torch or your broiler to brown the edges of the fluffy cloud of sweet egg white. You can even forget the butter and ice the outside of your cake with this stuff. You can also bake the meringue at 250°F (120°C) for a few hours and come out with crunchy, chewy, airy baked sweetness. I just wanted you to know that you’ve officially made something at this point. This could be a destination, but really it’s only a stop on our journey.