TEN

THE SECRET OF SPACE AND TIME

WE MUST NOW ENTER the most difficult stage of our inquiry into the process whereby we perceive external objects—that is to say, of our inquiry into the nature of human experience of the external world. We must relentlessly pursue this inquiry despite its difficulties, for the world is ever confronting us and silently demanding adequate understanding of its nature.

It is impossible to think of the world, or of anything in the world, without thinking of it as existing in space and time. This, as has been shown, is because the mind itself plays a most important part in predetermining how we shall see the world, compelling us to see it in terms of separate and successive images. Therefore the Indian sages said that thinking itself cannot reach and observe the world’s reality or essence. The scientists who have established the theories of relativity and quantum mechanics have now found themselves in the same plight. They have confessed that it is impossible to reach and observe the subtler phenomena of nature without interfering with these same phenomena in the very process of observation. The moment scientific research entered the mysterious subatomic world of electrons, neutrons, and protons, it had to recognize that the observer himself played a role in determining the phenomena observed by him.

What is immediately seen as the outside thing is really the mental picture. Science has slowly begun to realize this. The older scientific theories of optical illusion, for instance, made it purely physical, attributing it to some physiological disturbance of the retina or to a defect in the muscles of the eye, whereas the later ones introduce a definite mental ingredient. Matter is no longer all that matters! The older theories thought illusion an unimportant abnormality, whereas the later ones find it is bound up with the process of perception from beginning to end.

To mistake the bodily structure for the immaterial consciousness itself and to fall into the old trap of regarding the brain of flesh as the mystery of mind, are natural and pardonable errors in unreflective and uninstructed persons, in those philosophically unsophisticated people who turn in disgust from the first mention of this mentalistic doctrine. That a thing which is touched, seen, and tasted is as internal to the mind as it is external to the body, and that the body is in its own turn just as internal to the mind, irritates their common sense. Only the deepest reflection can show that the sensations derived from the human body itself are really as objective as sensations derived from fountain pens, because they are capable of being observed by mind, the subject. Thus second thought refutes what first impression asserts.

However, it would be quite a mistake to suppose that this teaching asks us to believe that visible objects are not seen outside our own body, that because it describes these objects as mental perceptions they must therefore be placed somewhere inside our body and that the glazed window before which we are seated is no nearer than yonder twinkling star. To attempt to place a house within the bony skull of a man is the futile endeavour of those who have failed to understand this doctrine, which, it need hardly be said, is entirely exempt from any expression of such absurdity. No material object of such a size could possibly exist within the material head of a man. Such impossible and improbable beliefs belong to the annals of lunacy and not to the annals of the hidden philosophy of India. The latter does emphatically agree that we see objects like houses and trees outside our bodies and certainly not inside them, and that all such objects are most undoubtedly seen to be at a distance from us as well as from each other. What it does assert is that the perceptions of the objects being purely mental, and it being impossible to assign any special spatial location to the mind, it is consequently impossible to say that these objects are seen at a distance from the mind itself.

The notion of the body’s existence as separate from mind, from awareness, is the fashionable fallacy entertained by the materialistic. To invest the body with the qualities which should be ascribed to the mind is strangely to misinterpret all experience. We have no right to treat our knowledge of all external objects as mental but that of our own body as material. Such a distinction is illogical and unjustifiable. If it be true to say that everything is known through the mind, it will be true not only of all external objects but also of our own body, with its head, hands, trunk, legs, and feet. These also are necessarily known mentally. There are no grounds whatever for thinking that they come in a different class from that of external objects. We must, therefore, treat the body in exactly the same way in which we treat all other objects and regard our awareness of it solely as the awareness of thought.

Nor must we make the mistake of many novices in this study, and most critics who disdain it, of imagining that the human body is known through the body alone although the objects which are outside it are all mentally known. Our body with its five sense-instruments, the eye, ear, nose, tongue, and skin, exists in precisely the same manner as a brick wall, so far as it exists as an idea of consciousness. We are aware of the sense-instruments themselves because of the sensations derived from them and not otherwise. For the reason that it consists of a certain shape, size, colour, et cetera, which are made known to us by the mind, the entire body—even the physical brain—is as much within the mind, and we are as much dependent upon the mind for awareness of its existence as we are for awareness of a brick wall.

The fact is that most men confuse their skin with their mind. They do not comprehend that the distance that extends from the surface of their body to the nearest thing is emphatically not the distance that extends from the latter to their mind. The cardinal error is to mistake extrabodily existence for extramental existence. Mind unconsciously projects its perceptions into space and then views the things of its own making.

Let us sum up these statements by applying a little analytic treatment, a little corrosive criticism to this word “external.” Nobody has ever seen an object outside the mind, but only outside the body. Putting aside the practical standpoint and speaking philosophically, it is wrong to talk of “external” objects, for even the body is known ultimately as a thought and is therefore mental: thus nothing at all is ever really external. To talk of an object being even outside the body is to talk of it being outside a thought, i.e., outside a mental thing, i.e., outside the mind—which is impossible. Those who use the word “external” ought to define whether they mean external to body or to mind. For if to body, then it has been shown that the body itself is internal to mind, so the objects themselves must also be internal to mind. And if to the mind, then the notion of inside and outside is wholly inapplicable. Hence we may not accurately say anything is external; we may only say it exists. The word contains its own contradiction. It belongs to an irrational and superstitious jargon.

From the first beginnings of consciousness each object is incessantly presented to the mind as being something apart and independent. We not only recognize a thing, but we recognize it as having a particular shape and size and standing at a certain distance away from our own body and from other things. We recognize it to exist in space. We are seeing it spatially. We possess an inveterate conviction, for example, that the wall which we see is situated out there in space and we feel that we dare not desert this conviction without losing our sanity.

But we must begin to face a queer problem. If no sensation can extrude itself beyond the periphery of the body, because every sensation is supposed to be the internal result of the operation of a bodily sense-instrument, why do we perceive the finished thought as a form extended in space? All objects said to be external stand in spatial relation to each other, but how can our ideas of them, which are apparently all that we know, be considered as having positions in space? If it has been shown that our thoughts or observations of these objects really are our experiences of them, why is it that this selfsame experience confutes our reasoning, for it reveals the objects as standing entirely separate from and outside bodies? How can an image which is said to be internal appear to us as an object which is external and which possesses spatial characteristics? How can colours which are scientifically provable as being optical interpretations, i.e., within the eyes, be able to assume the forms of independent outside things? The puzzle in short is how to account for the conversion of a purely mental experience into a seemingly separate and independent one, and for the projection of a purely internal experience into an external one.

To cast some light upon the answers to these questions we must make a lengthy scientific examination of certain aspects of the process of perceiving things through the senses. There exists a certain anomalous functioning of the senses which seems of trivial importance when considered from a practical point of view, but which actually offers unique material for an approach to profounder understanding of the places taken by the senses and the mind in observation of the world. Those peculiar errors of the senses which we call illusion and those mysterious derangements of the mind which we call hallucination provide interesting illustration of a principle whose weighty importance is usually overlooked by the unscientific or nonphilosophical mind. To underrate their instructive value because of their practical pettiness would be a mistake.

The experience of illusion shares certain common elements with constant and habitual experience, although it appears to mock sardonically at it. The psychological act of perception is present in both although the causes differ. The process whereby we become conscious of an illusion cannot be different from the way in which we become conscious of any ordinary thing. As an act of awareness both are indeed the same, even though one is said to be erroneous and the other accurate.

Science has found that the study of what is abnormal sheds new light on what is normal. Disturbances in the psychic process and defects in the physiological mechanism sometimes reveal valuable clues to the working of both or confirm the results previously obtained by scientific examination and pure reflection. Therefore when the mechanism of sensation is disturbed, as in illusions, and the physical stimulus is misconstrued, we get a glimpse of how the mechanism itself operates. Careful and systematic dissection of these abnormal experiences supplies valuable pointers which will help to render the intricate processes of perception more intelligible and light up more revealingly the respective roles played by the observing mind, the observing senses and the observed object. Therefore it is because of its scientific worth in helping to explain sense-experience that the subject of illusion is here taken up.

The Greek intellectuals like Aristotle were troubled about the easy way men could be deceived by their senses, but the Indian sages like Gaudapada not only noted this fact but carried their investigation to the last possible stage. For they were troubled about the easy way men could be deceived by their mind. The full implications of the phenomena of illusions—which every philosophy worth the name is called upon to investigate—require for their grasp a refined subtlety of apprehension which is not often found among Occidentals. The philosophical achievements of the West, although impressive, are surpassed by those of the Orient in the latter’s degree of metaphysical subtlety. Certain philosophical conceptions are not to be found in the Western literature, at least not in the developed form they have in the East. It is India which has proportionately produced the most men whose sharpness of concentration and subtlety of thought have combined with a singular subdual of the desires and egoisms which might weaken their undivided aim to pursue philosophy. Every aspect of illusion and hallucination has been thoroughly dealt with by the Indian sages, for they had a scientific bent of mind and would accept nothing until it had been investigated and verified. Unfortunately the sages disappeared, their knowledge was largely lost, and Indian philosophy degenerated with the lapse of centuries into the empty babbling speculation which it became in other countries.

Illusions are connected with a strange factor in perception which ought long ago to have set inquiring Western minds on the correct track to psychological truth, for it was noticed and deeply pondered on by Indian sages thousands of years ago, but its significance has not received proper attention in the West. And this is that we observe only what we are paying attention to; that amid all the multitude of retinal experiences we unconsciously select those only in which we are interested. Thus we may be reading a book while seated in a room; or we may be in an office at work which is deeply fascinating or of high importance. A clock may twice strike the hour and yet we may not remember hearing its chimes simply because attention has been highly concentrated on the reading or the work. The impressions are actually made on the sense-instrument, the sound waves succeed in striking the tympanums of healthy ears, but owing to the dissociation of attention they are not perceived by us although they are heard by other persons. We may be walking in the street and a passing friend may greet us. Yet if we are plunged in deep reflection we fail to see him and do not return his greeting. We see what we are looking for rather than what we are looking at. Consciousness grades down to dimness or even nothingness where we pay no attention to what we see while it compensatingly vividly lights up the object toward which thought has been surrendered in utter concentration.

When any piece of work is being attended to so completely as to occupy consciousness to the exclusion of all else, events may occur or objects may be present to the gaze and yet escape attention and pass unnoted. They remain outside the field of awareness although inside the field of sense-impression. That which dominates the mind dictates that which shall be perceived: this is one lesson to be learnt. When attention of the sensory faculties is preoccupied by the ideas of internal reverie the path to their external activity is blocked. This is practically illustrated by the case of yogis who are totally plunged in the state of trance or coma and then remain unaware or pain-free when cut with knives or buried beneath the ground. The mental factor of attention plays a powerful role in determining the content of what we perceive. The more the mind is directed to a bodily hurt, the more intense and intolerable does the pain become. On the other hand, the more the mind is occupied with some other event, the less troublesome will the hurt be felt. When thought flags or is totally withdrawn we may be blind to what is actually present before our eyes.

This extraordinary fact should alone have been a plain hint that the functioning of the mind both contributes to and withdraws something from the making of the world we witness. It should have been a warning that the mental factor cannot rightly be left out of any account of sense-experience. For if the mind does not cooperate with the senses there will be no conscious experience of any external object, however much the physical conditions may be fulfiled; or if it cooperates imperfectly, then experience will becomes less clear and less intense in proportion. It is difficult to become aware of the degree of mental interference when our normal state gives no evidence of it. We can hope, however, to do so by watching for abnormal experiences and unusual events which cause rifts in the veil of perception as it were. It has already been pointed out that psychologically it is an error to separate illusions from the accepted facts of normal life. It is from the analytic study of such exceptional deviations from the ordinary course of nature that we gain fresh knowledge of what such course really is. If an illusion is a false sensory impression it is still an impression no matter how it arises.

Let us consider first the class of illusions which belong to nature. The most elementary consideration of this question brings a startling revelation. Take, for example, the simple chair upon which you are sitting. Here is a solid, hard, and tangible object made of a natural material substance, which you call wood. That is the truth about this chair so far as you are concerned. Go, however, to the laboratory of a scientist. Let him take a piece of this wood of which your chair is constructed and submit it to his searching analytic examination. He will successively reduce it to molecules, atoms, electrons, protons, and neutrons. He will tell you finally that the wood consists of nothing more solid than a series of electrical radiations or, in plain language, of electricity. Yet despite such expert instructions and scornful of what irrefutable reason tells you, your five senses will continue to report wood as being something most substantial, the very opposite of whatever you can imagine electrical energy to be.

Does this not mean that you are experiencing an amazing illusion, one that is stranger than any conjurer’s feat? Indeed, the entire planet itself offers us a curious example of great masses of solid, liquid, and gaseous substances which are not really what they seem. For, if scientific investigation has not deceived itself, they are whirling winds of electrical energy, i.e., the lofty mountains, flowing rivers, rolling seas, and green fields are not really constituted as we see them. Their existence is certainly undeniable, but their appearance as “lumps of matter” is fundamentally illusory.

The study of modern scientific geography reveals the extraordinary fact that millions of persons are really walking upon this globe with their heads suspended downward and with their feet clinging to rather than resting on the earth. Such a statement, taken as it stands upon the printed sheet, is so astonishing that so-called common sense, when it is common uninstructed opinion, refuses to believe it, although the acceptance of the proved fact of the globular shape of our planet leaves us with no other alternative but to accept this further finding which is so contradictory to what our eyes tell us. What man would have known this fact if the scientists, through constant probing, had not ascertained it for him and thus discovered that the popular belief about the human bodily relation to the surface of the earth is purely illusory? This simple illustration may help us to grasp why those who insist on accepting the testimony of their immediate sense-impressions as alone being true are unfit for philosophy.

When the full moon rises, glowing redly, near the horizon it assumes the size of an enormous wagon wheel. But see the same moon when it is overhead and it has shrunk to the relative size of a coin. Which appearance are you to take as the correct one? Your eyes are not to be blamed, for the retina records a perfectly accurate image in both cases. The difference occurs because you unconsciously measure the suddenly rising moon on the same scale by which you habitually measure the hills, trees, buildings, or other objects which also occupy the horizon, whereas you ordinarily use quite another scale to measure those which are far overhead. Thus the sun setting behind a familiar full-branched tree will appear tremendously magnified because it fills the space occupied by the branches. You set up a false standard of perception through established habit and then judge the sun’s or moon’s size by it. But where does this error really occur? It is not in the object nor in your eyes. It can only occur in your mind, for it is a mistake of interpretation, i.e., a mental activity. The apparent enlargement of sun or moon is actually present in your idea.

Look at the landscape spread out before you in the morning. Your eyes may see nothing more in the background than a dull mist which fills the horizon. Photograph the mist with the help of a special plate sensitive to infrared rays. The camera will then grasp what the unaided sight cannot, for it will faithfully register the image of a hitherto unseen range of mountains twenty miles away. Similarly a sensitive spectroscope and photographic plate will reveal the existence of stars in apparently empty space even where a powerful telescope fails to reveal them. The fact that such natural illusions do exist and are possible is itself a critique of our knowledge of the world and its validity. If the senses can deceive us in these cases is it not likely that they can deceive us in others which pass unnoticed? These instances should give us ground not so much for distrusting the senses—for they are not directly to blame for these errors—as for distrusting our interpretations of the reports of the senses.

Yes, the senses can delude us. An observer in a rapidly descending aeroplane actually sees the earth rushing upward and a traveller in an express train actually sees telegraph poles moving past him. These are visual errors. But they help to illustrate how the process of vision really works. For they betray an element of judgment, i.e., of mental contribution, in what appears as the finished deliverance of the senses.

Why do the last hundred yards of a four-mile walk seem much longer than the first hundred yards when the impressions made on the senses of sight and touch are still the same as before, still as accurate? The answer is that the tired muscles have suggested a different series of exaggerated sensations, which produce the illusions of magnified movement and lengthened duration. The sensations, we must remember, are mental.

Enter a room which has been somewhat darkened and let the light of a small window fall on a green-coloured coat. Look at it through a piece of red glass. You may be startled to discover that it appears black. Then look at a red garment through blue glass and it also will seem to be black. Fit a green electric bulb and look at a blue coat with your naked eye. It too will appear black! Or fit a red bulb and gaze at a bunch of yellow primroses. The flowers will look strange, for they will look red. And it is a common experience to find that certain shades of cloth which look green in daylight change their colour to brown in artificial light. And santonin, a poisonous drug, if taken in a certain degree, causes many things to appear yellow. The plain implication of such optical illusions is that you must be prepared at least to mistrust not your senses but their working—for they are unable to work without the mind.

When you gaze at a patch of green-coloured cloth for some time and then turn to look at a different patch of grey-coloured cloth, the latter will assume a rose-red tint. The sense-impressions of grey colour cannot have changed. What is wrong is that the mind has misinterpreted them because present sensations are relative to previous ones and affected by them because in forming the images of experience the mind works on what it receives.

You see a magnificent rainbow arched from earth to heaven. But the pilot of an aeroplane passing through it will see nothing at all—a clear instance of relativity!

The lovely colours which touch the sky at dawn and sunset are partly the consequence of drifting dust and hanging vapour scattered in the air. Yet you see neither dust nor vapour and superimpose the colourings upon the space they fill. When waterdrops are large enough to break light up into the spectrum we perceive a beautiful rainbow. When they are assembled as massed clouds they are radiantly white when they reflect the sun’s rays to your eyes, but are dismally grey or black when they are so placed as to be unable to do so. Amid all these alternations of colourful dress and bleak veiling the light certainly does not change its own nature; it remains one and the same, but only appears to be different to different observers at different times. Thus the vast canopy of heaven is frequently a gigantic illusion of colour, teaching the unheeding minds of men to be wary of what they see, to reflect upon the relativity of all things, and to grasp the grand difference between seeming and being.

Look into a tumbler of clean water. Your eyes tell you that it is absolutely pure. Examine the same water under a microscope and you will find it to be swarming with countless animalculae. Lettuce may be thoroughly washed and appear temptingly clean, but here again the microscope finds it to be full of bacteria. In both cases the unaided senses not only fail to tell you the truth, but actually mislead you into illusion.

When a stick is partly immersed in a glass bowl filled with water it will appear to be bent out of position at the place where it touched the surface of the water, so that the lower part will seem to be lifted upward out of its straight course. Here the visual experience gives definitely inaccurate information about the shape of the stick, and will persist in doing so however perfect your eyes and however often the stick is seen.

Here is a wooden telegraph pole. When we apply a measuring rod we find it to be forty feet high. If we walk some distance away from it and view it, it appears somewhat smaller. And if we proceed considerably farther in the same direction and again look at it the height has been brought down to a mere few feet. Is the pole this little stick which is now visible? Is it the object which was so clearly and so convincingly forty feet long when measured? Here are three different heights which the pole appears to possess. Which one represents the real as apart from the apparent height? If we reply that the measured figure is alone correct, then we must explain why a measuring rod should be more privileged than a man and why the mathematical concept, i.e., idea, “forty feet” should be entitled to take precedence of the other idea, “four feet,” which arises when standing a considerable distance away. Nor is this all, for we shall also have to explain why the measuring rod—which is merely a length of wood—should be assigned certitude of length when there is such uncertainty about the telegraph pole, which is also a length of wood. For it is evident that whether we are standing immediately close to the pole or to the rod or whether we are standing at a hundred-yards distance from them, what we see in both cases is only the object as it appears to us.

This point has been covered in our scientific analysis of relativity in an earlier chapter. It raises serious and startling questions. Is the pole one thing and what we see of it another? Do we see things as they really are or only as they appear to us? If the latter, are we doomed to perceive appearances only, never their reality? The answers to these questions now begin to reveal themselves from our study of the perceptive process. For we have begun to learn that what we really see are the images formed by our own mind. Whether formed subconsciously or consciously they are still nothing more than mental images, thoughts. All appearances of poles or rods are but the revelations of our mind. We see our thoughts of things, not the things themselves. The question of what is the reality behind these appearances, what is the real object that gives rise to the thoughts about it, is too advanced to be dealt with here and will be taken up later.

What is true of sight may also be true of other senses. There are illusions of touch, for instance. Take three bowls of water—respectively cold, tepid, and as hot as is bearable. Put your left hand in the hot water and at the same time plunge your right hand in the cold water. Keep both hands immersed for two or three minutes. Then withdraw them quickly, shake off the drops and plunge both hands in the bowl containing lukewarm water. The water will feel cold to your left hand but warm to the right one! The sense of touch in each limb will contradict the other, for it will estimate different temperatures for the same water. That the same water is both hot and cold is not only a clear discrepancy between sense-reports but also an astonishing illustration how present sensations do depend on previous ones and that what we actually feel is partly a projection by memory from past experience.

Let a spade remain outdoors throughout a frosty night. Pick it up next morning. The wooden handle will feel a little cold, but the metal part will feel intensely chill. Touch will therefore yield a striking difference in the temperature of both parts of the same spade. Test them with a thermometer, however, and they will be found to register an equal degree of cold! So much for the dangers of trusting the accuracy of what we actually experience!

THE ILLUSIONS OF GEOMETRY

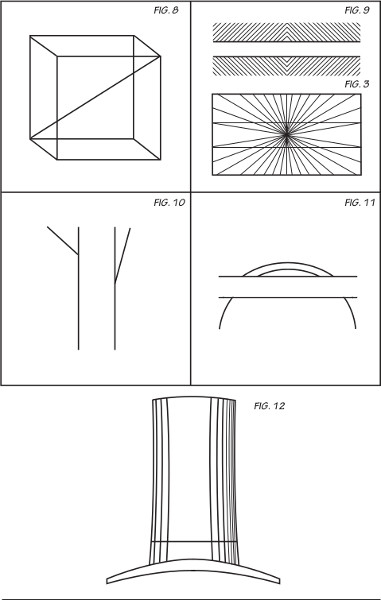

Let us next consider a totally different class of illusions, those which man has artificially created. There are interesting instances of geometrical illusions which are known to students of physics, physiology, and psychology. Figure 1 shows four horizontal lines of apparently unequal length each bounded by short oblique lines that turn inward or outward. Which line do you estimate as the longest? Measure them with a marked ruler and they will all be found quite equal! The top line looks the shortest because the eye locates its end somewhere in the arrowhead and does not follow it to the tip. The other lines also seem unequal because you do not isolate them from the rest of the figures. The retinal images of all four lines must nevertheless be the same size. So if we see the lines as unequal, then the eyes are not to be blamed, but the judgment. This means that a mental factor is at work in what we see and that it is powerful enough to make us see what it chooses, even when, as here, it is itself at fault by making wrong presentation, i.e., by constructing a wrong image.

Figure 2 shows a circle which appears to be unsymmetrical and flattened in four places, i.e., at the corners of the square. Test it with a compass and it will be found perfect! Figure 3 shows two long lines crossing a number of shorter lines and giving the impression of being curved in the middle, where the intersections are closer and more numerous. Actually they are straight and parallel! Here are two lines which are perfectly parallel, yet by the mere insertion of a few cross strokes most observers will find that they yield the impression of being convergent. This is an illusion of direction. Figure 4 apparently shows the outline of an elongated irregular four-sided figure intersected by many parallel lines. But if you accept it as such you will be mistaken, for it is really a perfect square! Figure 5 provides a conundrum. Which of the double lines on the right side of the oblong continues the sloping line on the left side? Most people think it is the upper line. Apply a straight-edged ruler and their error will be clearly shown.

Look steadily at Figure 6. Sometimes it will appear as a flat pattern, an acute-angled intersection of two lines, but sometimes it will recede from sight and appear as a solid object, a right-angled cross lying on the floor, at which you are looking obliquely from above. Close one eye and gaze for a time at Figure 7. Sometimes it will appear as a folded sheet of paper seen from outside and sometimes as if seen from inside with the fold farthest away!

The unshaded illustration in Figure 8 is more ambiguous and complicated than any of the others. A transparent cube confronts you. It will at first show one of its surfaces nearer the eye, but continued attention will suffice to reverse the experience and bring the other surface to the fore. The original surface will then appear to have retreated to the back and to be looked at through the body of the cube. This will convert the flat transparent cube into a solid opaque one. When steadily looked at the cube shifts alternately back and forth into different positions from moment to moment. The consequence is that different corners of the figure will be drawn forward in turn. It is important to note that the reversed interpretation will possess all the force of any ordinary everyday perception. You begin to see not what the artist has drawn in black ink on white paper but what your mind has imagined, i.e., constructed, out of its former experience of similar or related figures. The actual impressions made by these simple lines upon the sensitive retinas of your eyes are perfectly correct, as has been proved in cases where photographs of the retinal images have been taken by ingenious methods and reveal that no change has there occurred. Nevertheless, the figure of which you are aware is not merely a compound of these sensations but an entirely re-created one. That the mind itself can contribute largely to what it perceives is well shown by this experience. The illusory figure which is intermittently seen is the direct consequence of a subconscious mental labour upon the materials proffered by the artist’s drawing, for the latter remains unchanged.

Figure 9 should be held with the book askew. The horizontal lines will hardly look parallel, but they are! And when the illustration in Figure 10 is brought in the field of view the oblique lines will meet exactly at the same point on the right vertical line, although the eyes will almost invariably mislead one into the belief that they will not meet there! The sense-impressions are valid ones, but the judgment which the mind unconsciously passes upon them is not. The impressions of the eyes are free from reproach, but the impressions of the mind are not.

Only a moment’s glance is needed to tell you emphatically that the upper arc in Figure 11 continues the curve which begins and ends below the lower horizontal line. But take a pair of compasses and you will find how deceptive the simple faculty of sight can be. For it is the lower concentric arc which is the true continuation of the curve! Figure 12 is an excellent illustration of an illusion which persists despite its conscious correction after being detected. No matter how often and how long you look at this picture, nor how familiar with it you become, you will hardly avoid seeing it possessed of the same illusory character which it possessed on the day when you first saw it. Here is a picture of a silk top hat whose height appears to be much greater than its width. It is scarcely credible, but measurement will reveal that both vertical and horizontal dimensions are equal! The instruments of vision are not at fault, for the retina records only what it receives. What is at fault is the judgment on the impressions received, i.e., the mind.

It would be a gross error to dismiss all these illusory effects as unimportant geometrical curiosities. They are psychological tutors. They possess profound significance because they provide special clues to elucidating aright the most advanced phases of the process of perception. They demonstrate that the mental interpretation becomes mixed with the physiological impression, and in the consequent confusion it is easy to perceive the projected mental image as superimposed upon the printed figure. We may see as fact what the mind perceives, not necessarily what the senses tell us. How difficult, then, to vindicate the validity of one class of things seen as against another! Thus these fallacies of vision throw light on normal vision itself. When we see a geometrical figure differently from the way it is actually drawn we are actually seeing a production that the mind has transferred from itself to the figure. This is the psychological law lying at the root of illusion.

It is necessary to note a further strange point about the mechanism of these illusions. Continued observation does not lead to better observation. Even when you deliberately continue to fix attention upon them, they are not eliminated. They remain and cannot be removed. They may be illusions but they are obstinate and picturesque illusions. You cannot by taking thought rid yourself of them. No matter how familiar you may become with the same simple diagram, different interpretations of its form fluctuate before your eyes although your reason tells you that it is fixed by printing ink to the white paper! What does this stubborn persistence imply? How are you to account for this strange fact? If it means anything at all it means that errors of sensation, i.e., the results of processes which take place within the observer’s own body and mind may be projected from him so as to appear as physically outside things! For the illusory shapes which the drawings assume have no objective reality outside the mind that perceives them. You must therefore be ready to accept if necessary the startling notion that your visual impressions of the “outsideness” of a thing may be an utterly erroneous interpretation of those impressions. For the tricks of the senses are beginning to appear as triumphs of the mind.

MENTAL PROJECTIONS

We now come to a third class of illusions which may seem simple yet which possesses serious implications. A machine called the vitascope was popular a score of years ago in amusement places. You put a coin in the slot and turned a crank handle, when a brief but plausible moving picture was seen through a little window. The illusion of continuous movement was gained from a series of photographs mounted on cardboard which were brought into view one after another by the mechanical rotation of the handle. A further development of the same illusion is nowadays provided by the cinematograph. Here a series of individual static photographs are thrown upon a screen, but owing to the rapid succession in which they are shown they appear as actually moving pictures.

Where is the continuity of action which the beholder sees in such a picture? Is it in the picture itself? No, that cannot be, for it is only a lengthy series of “stills.” Therefore it must really result from some process that occurs in the eyes and mind of the beholder himself.

If a burning torch is rapidly whirled in the dark in the form of a figure eight an observer who is standing some distance away will actually see the illuminated figure as a steady, unbroken, and complete shape. Thus at a particular fraction of a second when the torch may really be at the crossing point midway in the figure the observer will nevertheless see it elsewhere forming the upper and lower curves of the figure. The explanation of science is that this happens because, as in the case of the cinema picture, the actual appearance of the figure depends on the persistence of the retinal image in the eye beyond the fraction of a moment when it actually caught the figure itself. Science has experimentally ascertained that a sense-impression may persist for a time even after the original stimulus has been withdrawn. The image which results is termed an “afterimage.” The response of the retinal nerve centres outlasts the stimulus itself and thus continues an independent existence of its own.

It is necessary to gaze a little more gravely, to penetrate a little more deeply, into this case. The eye is like a camera and faithfully photographs whatever it sees. It is even superior to a camera, because the necessary adjustments of focus, et cetera, are usually made automatically. It can therefore only actually register, in the case of the figure eight, a series of individual images of points of light. The registrations succeed each other so swiftly that the brain cannot separately take them up quickly enough. Consequently it fuses the multitude of visual impressions into a single sensation and holds to the general image of a scintillating figure eight which is consequently formed. It is the latter that then is taken up by the mind. Thus the mind continues to see what is virtually its own creation.

There are two stages to be noticed here. First, the varied positions of the torch flame as it is swung round are presented to the senses and immediately registered for what they are. Second, the sense-impressions are transmitted by the optic nerve to the brain so rapidly that the latter is unable to cope with them individually. So it uncritically receives them as an apparently continuous figure eight. The latter is then mentally seen and accepted as assuredly real. Nothing but close investigation can eliminate the error and correct the false perception.

It is most important to understand that the figure is physically nonexistent even when it appears to be seen. Where is it really seen? It can only be perceived by the mind as one of its own images, for it is connected with the observer himself, not with the torch. And it is still more important to understand that it is seen outside the observer’s body although it is actually inside his mind. It appears as a “given” presentation to his bodily senses. Yet this illuminated figure is after all only an intellectual construction.

The observer is not conscious at the time of having mentally constructed the figure, nor is he even later conscious of what he has done. Furthermore, even when he has learnt that the figure is merely an optical illusion, nevertheless he continues to see its illusory form. Thus the deception remains despite the fact that it is now understood to be such. Such a feat sounds almost self-contradictory. It is, however, a contradiction of the conceivable, not of the inconceivable, like a round square, nor of the fantastic, like a goat with lion’s head. It remains something which mocks at man’s belief and violently disrupts his conventional idea that what he sees is actually and necessarily just as he sees it. And it hints strongly that what he elsewhere takes to be valid observation may possibly be nothing more than mere credulity.

Consider the case of a still more significant illusion belonging to the same family. How often, at a certain moment of the falling twilight, when the galaxy of stars have not yet appeared, does the lonely wayfarer in Oriental jungles mistake the brown stump of a tree by the pathside for a wild animal crouching to spring upon him?

… In the night, imagining some fear,

How easy is a bush supposed a bear …

says the poet. And how often does a solitary leafless shrub by the roadside with a pair of bare short horizontal branches swaying in the wind as the same lonely traveller approaches it from a little distance away appear to be a menacing brigand waiting in ambush? The traveller will suddenly notice the figure in the dusk and start back in fear, hearing suspicious movements in the innocent rustling sounds, yet he is perceiving nothing more than a contrasted play of failing light and growing darkness acting as a background for the imaginary figure of a living man superimposed upon an inanimate shrub.

Insufficient or diverted attention, mental preoccupation or incorrect judgment, defective sight or dimness of light, may be said to explain why he sees a brigand and not a bush. This, however, does not explain the deeper significance of the illusion, which is why he should see externally an image which is existent either in the senses or in the mind. For it certainly cannot be said to rest in the object itself. Nor can it rest in the eyes alone, for they are, after all, only a natural photographic apparatus. They can record only what is physically present. It can therefore only be an imposition of imagination upon the object. It is here, when the interpreting faculty of the mind gets to work on the accurate data supplied by the senses, that the possibility of false interpretation enters and it is thus that illusions are created. Psychologically, it is impossible to distinguish a wrong image from a right one, because both are intimate personal experiences. Hence we may believe that we have observed something when, however, we have done nothing of the kind. Memories that burgeon out of the past or personal expectations of what should happen may incline us to expect to see the same thing again, even when it is not there. Under such mental preoccupation we tend to assume its presence. Thus the eyes are deceived because the idea is faulty.

If the illusion is produced by the man’s own mind, then its substratum is not to be sought in the swaying bush but in himself. The brigand in the bush is ultimately peculiar to himself; it is a part of himself. When it is closely analysed the illusory thing ceases to be external and becomes internal to his mind. The mind has put itself into a frame of vivid expectancy and intense anticipation, which has moulded through morbid fear or cowardly timidity the very image that it perceives. The impressions of the bush which it has received may provide the slightest resemblance to a brigand, but that is enough for the mind to seize and work it up into an illusory percept which falsifies the act of seeing not because fear and suspicion fill the man’s physical eyes but because they fill his mind. The misinterpretation of scene and sound is mental. The force of suggestion in the brigand illusion is so powerful as to superimpose a mental creation upon the physical thing registered by the sense-instrument. The image which should be the normal consequence of such registration is displaced by another which takes its place as the perceived object. Thus a fiction of the imagination displaces part of a physical fact; the form of the bush is merged in the form of the brigand.

These statements provoke an interrogation. What is the practical difference between a genuine brigand who is somewhere seen and this illusory brigand? In both cases the terrified traveller really believes he has seen a brigand. Yet in one case he has only seen a bush which does duty for a robber. His eyes can only have recorded the impressions of a bush, for a camera placed in the same spot and using the new kind of films which are ultrasensitive to images even in darkness would have photographed a bush and nothing more. The eye, we know, is really constructed like a camera. The image of the brigand must therefore have existed somewhere else if it never existed in the eyes themselves. And the only other medium wherein it could have existed is the mind. The mind, therefore, must possess the amazing power to fabricate images which strikingly resemble ordinary percepts as well as the astonishing capacity to throw them seemingly outward into space.

Shall we raise our eyebrows in astonishment at these provocative paragraphs or shall we merely dismiss them with a tremendous sneer? Shall we hesitate to admit that the mind possesses the power to put forth and retract images that are seen externally to the body? For this would indicate that men unconsciously possess a kind of magical power. But is it not heresy to declare this? Well, let us be bold and admit that we do not know what limits to set to the faculties of the mind; it is an ineluctable mystery, and stranger things have been recorded in the annals of abnormal psychology which stagger the unfamiliar and perpetually puzzle the researcher. Or if this is not to our taste let us agree to call the possibility of objectifying a mental picture, not a mental power but a mental defect! That will not, however, remove the fact that it is universally shared, and therefore we must all be prepared to suspect the presentations of both sense and mind. This is the startling implication of the impregnable logic of these facts. For it opens up the strangest possibilities. If a single illusory object may thus be perceived, why should not a worldwide range of illusory objects also be perceivable within self?

We must try to assimilate these luminous discoveries to our world-outlook and to our view of man himself. We must become courageous iconoclasts and refuse to remain intellectual idolators. We need not fear to follow up such thoughts to their logical conclusions if we are to winnow out some wisdom from these studies. Is not the immutable stability of the earth but a deceptive show, a flagrant error of sensation, a visual and tactual experience which reason boldly denies, for it is easy to prove that the globe is in perpetual movement?

There are two kinds of illusions, those which deceive us about what we do physically see and those which deceive us into seeing something that is not founded on any physical stimulus at all. The second kind is called hallucination and is an error of thought alone, whereas the first is an error caused by imposing a mental image upon a physical object.

Sensations suggest the presence of an external object, but when sensations arise in the absence of such an object, then we have a case of hallucination. Hallucination of the higher senses, i.e., sight and hearing, are the most common. A hallucination might be termed an illusion that has no physically objective basis. Illusion approaches the degree of hallucination when there is physically nothing at all present to the bodily senses to justify it. If a man vividly sees something where there is nothing to justify what he has seen he is under a hallucination, whereas if there is some physical thing to afford a basis, however slight, for his perception, then he is under an illusion.

It is common to regard hallucinations as occurring only among the mentally deranged and the cerebrally diseased. This self-flattering error arises because it is in such circles that the most striking and the most distressing forms of hallucination exist. But aside from these pathological cases it is nevertheless true that everyday experience in politics, business, and society shows that numerous individuals who are apparently normal and sane in every other respect fall under private hallucinations of their own at some time or other of their life.

The roots of false perception and illusory sensation lie precisely where the roots of right perception and normal sensation lie—in the mind. From the standpoint of psychology there is no antithesis between the hallucinations of madmen and the illusions of the sane. Both are so closely related at bottom that the one class passes by imperceptible degrees into the other. Hallucination is the strong conviction that something is present when it is not. The insane, the delirious, and the feverish are attacked by wild beasts or hear strange voices which obviously exist only in the patients’ own imaginations. The fact that hallucinations may arise out of such abnormal sources as disease, exhaustion, and drugs does not diminish their value for helping to understand the normal processes of perception.

There was once a painter who after a first sitting could call up the face, form, and dress of his sitters with such vivid accuracy that he would glance from time to time at the imagined sitter in order to compare him or her with the picture while he worked. In the end he became convinced that these imagined persons were as real as the flesh-and-blood ones. So a sapient civilization rewarded his remarkable development of the imaginative faculty with a long stretch in a madhouse. He was certainly suffering from hallucinations, but his case was full of instruction for the humble. For a mental process like this that ran off the usual track made it possible to approach the study of mental workings to a degree that would otherwise be impossible.

The significance of such a hallucination lies in its indication that the mind, without any extraneous aid, possesses a power to project convincing images which have no corresponding physical stimulus and which are then taken for perceptions. Such images also possess the capacity to recur or even to persist. The mistake in identity made by maniacs who fancy themselves to be Napoleon, et cetera, reveals the power of a dominant idea to create wrong sensory impressions. When the mind is dominated by a fixed preconception of this kind the likelihood of falling victim to illusion or hallucination is increased. We begin to see what we expect to see. The hallucination has a reality not less cogent than that of physically based experience. Yet if we are willing to be patient and without prejudice while we make a deeper analysis than habit usually permits, examination will show that the same characteristics may be found in all other mental images, whether they be the reproductions of fancy or the products of dream. For fancied objects will be hard to the touch of a fancied finger, and dream landscapes will be coloured and lined to dream eyes. If, however, we set up the wrong standard and demand that fancied things should submit to physical tests we are mixing our planes of reference and confusing our standards of dimension. We must be fair. For the reply to such unfairness could be a demand that our physical things be tested by dream standards! The sense of externality in our view of the physical world seems inexpugnable. But close the eyes, shut the doors of all outer sense organs in sleep, and lo!—in dream you will find a world as vividly external as your physical one. This betrays the mental character of the feeling of externality. The existence of abstract reverie and the experience of dream provide evidence of this power to project mental pictures into space and impregnate them with the force of reality. We must make it perfectly plain to ourselves that the processes of consciousness are so amazing that mental images may appear objectively to the body. Hypnotism proves this, dream illustrates it, and the phenomena of illusions demonstrate it completely.

The difference in content between a hallucination and a dream is, from the psychological standpoint, nonexistent. Consider for a moment how imagery that has no objective basis at all develops during dreams, abnormal states like hypnosis, and insanity into actual perceptions that are in no way different and in no way distinguishable from those seen in the case of physically based ones. A hypnotized person may readily observe what the hypnotist suggests to him as being present, while on the other hand he may fail to observe an object confronting him if a contrary suggestion is given by the operator. If it be suggested that he is sniffing pepper he may begin to sneeze violently, even though no pepper is actually there. And mystics who concentrate excessively on a particular image during meditation find in time that it takes on the vivid immediacy and colourful actuality of a physically stimulated percept.

It is the revolutionary lesson of hallucination and of illusion that things and persons seen standing outside one’s body and yet having only mental existence are seen as objectively as things and persons having a physical existence. We need this lesson badly, for we are all equipped by nature and heredity with a bias which falsely believes that everything seen outside the body must therefore be outside the mind and that the products of pure consciousness are only to be experienced internally to the body, i.e., within the head. It would be well to give such an outworn doctrine a valedictory dismissal.

We have learnt that a group of images can appear within the field of consciousness and yet appear as though they were outside oneself. It has been sufficiently shown that the mind can certainly throw its pictures outside the body—the analysis of illusions alone has yielded this startling fact. Illusion shows that we can perceive what is not in our physically derived sensation of an object, while inattentive mind-wandering shows that we cannot perceive all that our physically derived sensations tell us about an object. Ordinarily the transformation of mere sense-impressions into full percepts is instantaneous, and therefore indistinguishable to self-observation. The entire physiological and psychological movement occurs with such kaleidoscopic quickness that nobody is able to detect the two stages. This is one of the important reasons why the study of errors of sense and hallucinations of mind is such a tremendous help in throwing light upon the manner in which sense and mind combine to construct our experience. For they open a gap, as it were, in this movement and enable us to observe something of what is really happening. It is an error to regard them as extraordinary perception. They are not. They are normal perception operating as it always operates by an act of mental creation.

Let us attempt to assess the valuable lessons which we may draw from illusions. The richest of all the broad veins of gold in this neglected mine of study are twofold. First is the striking proof thus offered that the whole of perceptual life can be a mental construct. For the apparently abnormal experience of illusion demonstrates how the acceptedly normal experience of everyday life is not something solely and passively received by the senses from an outside world but something which still more is formed, arranged, and imprinted by the mind from its own inner store. It is itself the main source of its own experiences. Each perceived thing is indeed known only as a mental one. And this is true even of such hard and heavy things as the thousand-ton statue of Rameses II, which lies prostrate and broken on the desert’s edge, as it is true of such soft and delicate things as the winter snow which lies thickly on the Himalayan passes. For the empire of mind extends over all that is seen, heard, touched, tasted, or smelt.

The varying causes of illusory appearances may be trifling or important, may be flaws in the mechanism of perception or images brought up from the past, but this does not reduce the significance of the point. The arisal of the spectacle of such externally perceived objects is a mysterious and meaningful event. It must be understood. And it can only be understood when understood as a mental experience, a pictorial and creative effort of mind. The inner working of illusion, which is said to be abnormal, becomes a guide to the inner working of sense-awareness, which is admittedly normal.

We may now understand that illusions and hallucinations are ultimately mental in character merely because all sensations and all perceptions are mental in character. There is no difference in the ultimate origin of both, for although one seems subjective and the other seems objective they arise alike from the same source—mind.

The second noteworthy lesson from hallucinations and illusions is their bringing things into awareness that are seen to be extended in three dimensions of space, lit, shaded, and coloured, and are nevertheless nothing but ideas, mental pictures. Where have we seen the illusion? It has been seen outside the body. Where is the illusion found to be when we thoroughly investigate it? Inside the mind. The conclusion can only be that ideas can be projected so as to appear outside the body and that the common belief that ideas are only to be seen within one’s head is a false belief. So far as any illusion is an act of perceiving something, it stands on the same footing as the ordinary and authentic perception of everyday life. But if the former has now been shown to be a mental act, then we must conclude the latter to be mental likewise. The final conclusion is that the analysis of illusion verifies the primary character of the mind’s contribution in the knowledge of external things and vindicates the doctrine that ideas can be objectified into space-relations with the body.

THE MAKING OF SPACE AND TIME

Our earlier inquiry into Relativity revealed that much of the fixity of space and time was fancied, for they were found to vary with different observers. Man thinks he is experiencing real space when he looks out at his external environment and sees one thing here and another thing there and so on. If that is so, why does he see the sun as the size of a silver coin? And why does he still perceive that the sun rises and sets daily when reason denies it and proves its denial? It is clear that he is not aware of the real dimensions of the sun in space, and therefore either cannot be experiencing space as it is or else is experiencing space as he unconsciously thinks it is. The paradox is that although he never meets with such an unchanging space in experience he is constantly subject to the belief that he does. It is a pure illusion but one which binds the mind more tightly than it ever knows.

The three-dimensional world which stands behind his reflected image in a glass mirror is purely illusory. He knows that it is illusion and yet his knowledge cannot get rid of it, do what he will. Hence something may be immediately “given” in his experience and yet its existence may be only apparent and not real. Similarly the philosophic attitude which labels its percepts of external things as mental does not change them in the philosophic experience. They still remain as they are, i.e., external and extended in space, and remain so throughout a lifetime.

Let it be clear therefore without the possibility of misunderstanding that the hidden teaching does not deny in any way whatsoever that a world of objects is set out in space beyond our bodies. The fact itself is indisputable, the notion of it is universal, and none but a lunatic would set himself up to question it, but the form in which it is maintained is not. All these things—the objects, the spaces, and the bodies—may still exist as they appear and yet be known only as phases of consciousness. If sight tells us that an object has distance in the field of vision, reason explains that the distance is a mental construction.

When we reflect that a stereoscope shows flat surfaced photographs in all the depth, solidity, relief, and perspective of the natural scenes, we have to grant that it is not more miraculous for us to perceive the actual scenes themselves as projected at a distance from our bodies and outside them in space. For not only are two slightly different drawings or pictures made to appear as a single and complete one but their flatness totally disappears and what is portrayed upon them is made to appear in perfect relief, actual depth, and natural solidity. Thus the stereoscope produces the illusion of a single picture when actually two separate and distinct pictures have been placed in the apparatus and are both being gazed at. We do not explain this strange fusion by explaining that the two lenses of the stereoscope, like the two eyes of the human head, being set in different positions, reveal different aspects of the same object and the two resultant pictures coalesce into one. This is certainly the beginning of the process but not the end. Such a case of plane illusion which appears to have depth when there is only length and breadth alone indicates that the mind cooperates in vision and is finally responsible for what is seen. For the work of uniting the two pictures is a constructive and creative one. Therefore it is done by the mind. The final integrated percept is fully mental. Its manufacture may be a subconscious one but it is certainly a mental one.

Mind puts forth its own constructions. All these analytic processes which make sensation possible and all these synthetic workings which present us with an external object are ultimately of the nature of mind itself. Perceptions have all the spatial qualities and all the spatial relations, all the solidity and all the resistance to touch, all the coloured surfaces and all the lines, angles, or curves when they appear before the mind, that we believe the outside objects to have. Nevertheless it is unavoidable human habit to objectify and spatialize its images and solely attribute them to a nonmental, i.e., material, basis.

To understand the final phases of the perceptive process let it first be noted that we never directly see the real size of an object because only the image which it produces on the retina of the eye is reported to the brain. Look at a lofty telegraph pole, for instance, through a pair of spectacles while standing some distance away. Give part of your attention to the lens of the spectacles and part to the pole. You will then become aware of the fact that the pole stretches across half their diameter and no more—that is, less than three-quarters of an inch. This is the image on your lens. Let us suppose that the pole is about forty feet high. Do you see a forty-foot image? No, you actually see upon the spectacle lenses an image which is one six-hundredth its size. Now remember that the pair of spectacles are simply like projected portions of the eyes but slightly larger than the eyes themselves. What appears to be seen as though it were in the lenses of the spectacles is very little larger in size than the image which appears on the retina of the eye. It is quite impossible for the optic nerve to report to the brain and hence to the mind any dimension larger than the dimensions of the retina itself. The mind never learns directly the size of the external pole but only the size of its greatly shrunken image. The up and down, right and left movements of the eyes produce muscular sensations of the pole’s distance, position, and direction. The image of the scene pictured on the retina is a spatial one, i.e., it has length and breadth. But no such spatial picture can itself be conveyed to the brain by the optic nerve, but only “the telegraphic code” vibration concerning it. Therefore the mind has somehow to imagine, construct, and project such a picture as well as the space needed for its background. This it does and then an image arises. The space, the space-properties, and the space-relations of the pole are therefore purely mental creations.

The flow of sensation is uninterrupted. We are continuously giving birth to numerous thoughts, for that is the essential meaning of human experience, and the mind must discriminate one from another. Every perception of an object must be different from every other if it is to be perceived at all. The mind must determine a separate form for all its images. This it does by spatializing them, by spreading them out, by setting up each image in space dimensions of length, height, and breadth. Consciousness could not operate otherwise in the form of perception unless it did this, for failure to do so would mean that no image could exist separately and therefore could not exist at all.

No object could ever be visible to us unless it appeared to be outside us in space. For in no other manner could it be formed into a distinct separate thing apart from the seer. If the object were in the inside of the eye it could not be seen at all. Therefore it must appear to be existent beyond the eye if the eye is to function like a photographic camera at all. Any object to be visible must be visible as separately individualized and independent of the eye which beholds it. We have already learnt, however, that all sense-function is performed only mediately by the sense-instruments and immediately by the mind. If therefore the mind is to possess the power to perceive any particular object it is compelled to form such perception by externalizing the object and thus extending it in space. Mind must set out all perceptions in space, i.e., localize them, and it must project them outside the body and thus finally perceive the entire result as an extended and external object. The space, however, is not really a property of the perceived object; it is a property of the mind itself and is bestowed by the mind upon the object.

A striking illustration of such working is provided by the cases of persons born totally blind and afterward cured in later life through surgical operation. During the first period after the restoration of their sight they are unable to judge size, shape, or distance without making the most ludicrous errors. Objects appear to be so close to the eye as almost to touch it. Neither externality nor distance take on proper meaning, for although the eyes have been put in good order the ideas supplied by memory or association, which enter into the formation of ideas of space, are lacking. One blind man who was operated on and recovered his sight thought at first that all objects “touched his eyes.” He could not judge the smallest distance, could not tell whether a wall was one inch or ten yards away from him, and could not understand that things were outside each other.

Precisely the same necessities apply to the mind’s need of setting up images in time. It is forced to put them into sequence, to make them succeed each other, in order to put them into existence at all. Everything crowded together in one point and one moment would be equivalent to nothing appearing. Hence the need of time, which mind accordingly makes for itself. Thought becomes possible only through the mind making it take its passage through time. Time is the very form of thought.

Why is it that despite the fact that we are travelling through space at a speed of not less than one thousand miles an hour—a motion easily determinable by the earth’s relation to other heavenly bodies—we feel no sensation of this enormous velocity at all? Why is it that the passenger in an aeroplane who shuts his eyes can hardly realize a sense of journeying and notices its movement only to the degree that it proceeds more slowly and not more quickly? The answer is that the world of time is entirely based on relativity, which is ultimately mental. Time is so elastic that it is a completely variable relation and its power over us is due to the peculiar way in which the mind naturally works, to the manner in which thought manufactures the arbitrary distinctions between slow and fast, present and future.

The distance, the size, and the shape of a fountain pen appear to be outside us. In the case of distance it will be found that sight is unable to determine by itself without the aid of judgment, i.e., without the aid of mind, the relative distances at which objects are placed from the eyes and from one another. The impression of the pen is mental, hence inside us, but we think of it as being outside us. We refer the perception of it outward to space, projecting its qualities to points or areas external to the body; we think of it as existing at a distance from us, although the sensation which constitutes the first conscious knowledge of it occurs within ourselves. Thus the appearance of its spatiality is mind-born.

When we say that the pen is outside us we are saying something about its position in relation to the eyes but nothing about its position in relation to the mind. We are reckoning its distance and direction by setting up the body as the spatial centre and confusing that with the mind. Ordinarily we locate the mind somewhat indefinitely in the head, but never dream that the picture of the pen which is presented to our eyes may actually be immaterial, i.e., mental. This is because we become aware of our own body and feel that we are spatially situated inside it. This feeling plays a central part in space perceptions and arises chiefly because of passive sensations of touch originating in the surface of the body, together with sensations of pressure received through the muscles, and also through sensations of sight. We are not immediately aware that it is the mind which has brought into being this field of touch, pressure, and sight. The qualities are transferred externally to the body and thus given an objective existence.

It is said that a thing must be there in the external world because the eye tells us so, because the ear informs us so, and because the touch so reveals it. But here a most important question must be asked. Where are these three senses? Where are eye, ear, and skin? Are they not where the thing itself is because they interact with it? Do they not occupy the same world as the table that is seen and touched? This cannot be denied. But if that is so then they are part of the external world themselves. Therefore to argue that we know a thing is outside because our senses tell us so is to argue that it must be outside because our senses themselves are outside. But this brings us back to the starting point. For if everything is outside, then the term “external” loses all meaning. There is then no “outside” at all. We may only say that the world is there and that the senses are there but we may not say that they are external to the mind.

From this we may deduce that the old notion that the body is a sort of perishable box containing a permanent soul inside is fit only for children. The newer notion that it is itself an idea within consciousness is more in consonance with modern science.

The situation of a thing and the period of time during which it is situated—these are the twin moulds in which must perforce be thrown our entire knowledge of all things. Thus space and time are the mind’s very modes of arranging conscious experience. No other modes are possible if we are to become aware of anything—whether it be a vastly distant star or our own fingertip. The mind, by making its images conform to the laws of space and time, anticipates the very form of all its possible experiences of the external world. The images are not produced by experience, but themselves produce our experience. This is the iconoclastic but clear truth.

When the true nature of perception is placed in a clear light it will be seen how doubly we may be deceived by the very senses which pretend to reveal the external world to us. For they may not only distort the thing they have to report, as in the case of illusions, but also deceive us into thinking that our direct experience of that thing in space and time is physical and not mental. It is now possible to understand why the revelation of Einstein mentioned in the previous chapter, although but a partial and limited one, was nevertheless on the right track. He found that space was a variable relation and showed why it must be so, but he never attempted to explain how it was so or how it came to exist for us.

Thus the clusters of sensations which constitute the things we view are automatically and inevitably moulded by the mind into space-time form. In short, so long as we continue to experience the world we must perforce experience it as an appearance in space and as an event in time. This is a predetermined condition of human existence and applies to everyone, and nobody, not even the philosopher, can escape from this condition. The very principle which accounts for our knowledge of the existence of this world accounts also for its space-time characteristics. They are but necessary factors in the formation of our sensations. We are ourselves its source. Our faith in the objective character of space and time relative to mind is, however, so strongly inborn and inherited that its validity passes unquestioned. Only a tremendously bold effort of inquiry can ever bring us to repudiate this belief. Cowardice is not caution. Truth wants no timid friends.

For practical purposes we believe, and we cannot but believe, that the printed book which lies so plainly before us is perceived outside ourselves but inside space. The very constitution of human awareness tells us so with an irresistible authority that cannot for a moment be denied. Any other assertion runs contrary to common sense. Yet we have previously proved that space is a constituent of the mind, that without its presence the mind would refuse to function. In short, space dwells within the mind. This leads us inexorably to the next conclusion. If the book exists in space, and if space exists within the mind, then the book can exist nowhere else except in the mind itself. That which we are perforce compelled by Nature to see as the printed page outside us, i.e., as the seeming not-self, is none other than a perception of the self itself, a refraction of its own light, a presentation of the mind to its own sight.

People think that the mind must dwell only within the confines of the skull. But if the mind is the secret manufactory of space, how can it be itself tied to spatial limits? How can it be limited to this or that point in space? How can it be placed only in each man’s head? We shall look in vain for a plummet which shall fathom the mind’s depth or a rod which shall measure its breadth and length.

There confronting us is a world of hard realities, a panoramic procession of solid objects and substantial things. He who comes, like Socrates, to persuade us to call into question their “outsideness,” which seems so certain and so irrefutable, has no easy task. He is quite unwelcome, for even were his queer ideas to be true they are most distasteful. They appear to remove the very ground from beneath our feet. There are inherent properties in such ideas which render them chemically repulsive to the crowd mentality, which flies from truth to take refuge in self-deception. Hence philosophy has kept them hidden in the past for the benefit of a truth-loving few. The fact that every surrounding thing is known only as an integral mental construction rather than as an outside material one, that it is seen as an image produced in the mind, will appear to be a miracle to untutored people and utterly beyond belief, just as popular uneducated thought naturally and inevitably assumes that the earth is flat and that the sun revolves around our planet. It holds firmly to such an opinion and deems the contrary statement that antipodean lands exist and that the earth circles the sun to be sheer madness. How then has it been possible to establish this startling astronomical truth among men? It has been possible only by supplying them with certain related facts, and then by persuading them to use their reasoning powers courageously upon those facts until deeper significance stood revealed. Precisely the same problem confronts us in the popular belief that every material thing exists outside, apart, and separate from the mind. Philosophy refutes this naive overwhelming belief and removes this misapprehension, but it can do so only if men will look at the facts it offers and then study them deeply and impartially with inexorable logic to the very end. Without such absolute rationality it could never hope to triumph over such a powerful and primeval instinct of the human race like materialism, which is not truth but rather a travesty of truth.

Our knowledge of the outer world and our perception of things in space and time are the forms taken by our mental processes. We need to absorb this hard truth here ascertained that what is inside the mind can be seen outside the body. The case for it is unanswered and unanswerable. Its position is unassailable. All counterarguments, all contrary views, can be met and mastered. For it is not merely the odd notion of amiable cranks but as certain and as proven as any other verified fact in the armoury of science. Therefore this shall be the truth which shall take a new incarnation for tomorrow.