Awe and Wonder

I wind through a torchlit path and encounter two serene figures lying with eyes closed, a man and woman, painted and gaily dressed, covered in flowers. Who are they? Why are they here? I enter the circle and quickly find myself decorating panels with paint using potato print blocks. The task is a collective joy, and I help a child add their part. It is strangely mysterious and yet fun. I am led to experiences, and voices speak of the frailty of all the grove surrounding me. Together we all call to the Gods of wild nature, and they come, bearing gifts! As our voices raise in song into the night, our work is revealed. Though the Gods are leaving us, and our time here is done, we truly know They Will Remain!

They Will Remain Ritual

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed.”

Albert Einstein

Awe is that sense of magic we experience from encounters with the mysterious. Using all our ritual tools, we want participants to leave having had that feeling of wonder. It can come in many forms: expanding our knowledge of the natural world, the sacred nature of ourselves, our community, or our relationship with things beyond ourselves. The heart of community ritual is found in creating a place to experience these emotions that increase our well-being. In this chapter, we explore some techniques to take the ritual journey directly to wonderment.

Guided Meditation

The aim of a guided meditation is to fully allow each person to make their own unique mental journey. When done well, participants encounter a profound multisensory vision.

It is difficult to incorporate an intense guided meditation like this into large group ritual. The technique requires an inner quiet and comfort for each participant, and they all must be willing to embrace the process in order for it to work. A completely developed guided meditation that can be the primary focus of a ritual is best done with groups of less than fifty. Work indoors where comfort, the climate, lighting, and intrusions can be tightly controlled.

More often, an abbreviated meditation and a compressed induction process are used to briefly create this kind of personal experience as part of a larger ritual outline. For large groups the purpose might be to encounter one place, concept, symbol, or deity, and use each participant’s response to frame and enhance the balance of their experience. Participants might visit the Underworld, the Tree of Life, or encounter, say, a goddess of the hearth like the Greek Hestia. Then later in the ritual they might interact with a symbol or prop representing the Underworld, or the Tree of Life, or a costumed character representing Hestia.

Multiple voices simultaneously guiding induction, with participants divided into smaller groups, is one technique you might use to be effective with a larger group. Have your participants slowly walk in a circle, on a labyrinth or down a path, with the meditation delivered in segments as they move past. The judicious additions of ambient sounds and smells can provide more layers of sensory involvement. With a community ritual, we also need to be able to structure meditation so that whatever we individually experience, the journey will support the intent.

Before you write, consider the purpose of your meditation and define the result you are looking for. It helps to visualize the meditation repeatedly in detail, from beginning to end, making note of any significant symbols or events you want to include. Think carefully about what visual, sensory, and symbolic touchstones your words will provide and how they tie together with the ritual purpose. The entire journey will eventually develop to the point where you can begin writing. A guided meditation should be thoroughly composed. Even experienced leaders do not attempt to improvise when the details of the voyage can be so important.

Guided meditations usually follow a recognizable structure. You will prepare participants to be receptive to the alpha state 28 by getting comfortable and relaxing. Begin with gentle directives: “Close your eyes, and take a deep cleansing breath.” A technique commonly used to begin is to ask the listener to visualize entering a cave, building, or opening under a tree. As they walk down a staircase, steep path, or ladder, reinforce and deepen their relaxation with each step.

As the meditation begins, describe in very general terms what the participant encounters. You want to encourage use of the senses to engage participants’ imaginations so they are immersed in the experience, while letting them fill in the details. If you describe encountering a doorway, ask participants to note what it looks like, what may be written on it, or what it sounds like when they open it, and what they notice about the room. A meditation can also be a story, one with characters and a simple plot. Continue to reinforce relaxation occasionally and remind everyone they are safe and secure as you progress.

Participants should be restored to normal waking consciousness gently and gradually. Guide the listener back to the starting place of the meditation. Have them return to the doorway or stairs (whatever they encountered at the beginning), counting them back to a wakeful state as they move toward the entrance. Carefully help them reclaim their awareness and enter back into the world around them. Keep some salt handy—if anyone has difficulty returning, help them place a small amount on their tongue while sitting on the ground.

Some simple tips to help you get started and avoid common mistakes:

- • Make sure everyone can hear you.

- • If you are reading it, be conscious of your paper rustling. Any ambient noises can be very distracting.

- • Be aware that people will race past your voice if you take a long time to describe the next step. For example, if you say “the water ahead,” they may have already turned the lake you want them to see into a river.

- • Speak in brief phrases with a relaxing cadence, ending phrases with a lowered pitch.

- • Give general descriptions and then allow or ask them to fill in the symbolic details: “What sounds do you hear?” “Do you see anything near the large tree in your view?”

- • Keep the whole meditation in the same “person.” Use either “you” or “we” consistently.

- • Avoid references to time. Each will be sensing time at their own speed and will be jarred when you say time-defining words like “now,” “immediately,” or “suddenly.”

- • Phrases that are unconditional and undemanding work best: “Allow yourself to … ,” “Pause here until you have heard what may be offered,” “Something may be drawing your attention.”

- • Before returning, add an instruction to remember what they have experienced. This can be really helpful for some participants.

- • Allow enough time for everyone to be comfortably returned, and check in with each individual before moving on with your ritual.

The ability to write and deliver a guided meditation is a skill that you need to practice to develop. Start out by recording yourself for critical listening. There are many resources available to develop the skill of leading a guided meditation. If you wish to include this in your toolbox, practice on small groups of friends and get their criticism after each session. You may think what you offer flows seamlessly, but they will let you know where you lost them at every turn!

Invocation and Evocation

Your community may be blessed with people who can welcome a sacred presence or deity itself to enter or speak through them to a community. This is a skill that you don’t just choose to develop for the occasion of a community ritual. Both invocation and evocation take time, talent, and work to develop fully. We will call people who have this ability “spirit workers.”

Invocation is the calling of a spiritual essence into oneself. For invocation to take place, each spirit worker and each specific deity will have requirements. These might include personal purification, prayers, supplication, or offerings to the deity, and specific words or an incantation to initiate the possession. When an invocation is taking place, the spirit worker opens herself or himself to be literally taken over or “ridden” by the god form and may interact as a deity with your ritual participants.

Nels: In the “Ritual to Enki, the Father” (see chapter Seven), I was helped by a spirit worker, Breighton, who had already worked with Enki in the past. He was willing to attempt a sustained invocation during the ritual in order to speak personally to most participants as Enki. In preparation he offered devotion and prayers for several weeks to enhance his relationship. During the course of the ritual, whenever his god connection started to wane, I would pause the interaction, offer Enki’s favorite scent (copal incense), and asperge the feet of all the men around the circle with water sprinkled from a leafy branch. This allowed Breighton to maintain his invocation for nearly an hour.

Evocation is to “call forth,” the summoning of the spiritual essence of a god form. The deity’s words or actions are expressed through the spirit worker, who remains fully aware of themselves. The term “aspecting” is also used to describe the manifestation of a particular characteristic or god form in this manner. People disagree about what actually happens during aspecting. Some see this as having the deity enter into them. It may be tapping into their own divine relationship. It is usually observed as a heightened trance state.

Asked to design the annual ritual opening of the drum area at Pagan Spirit Gathering, we chose a deity pair we were familiar with and had worked with in the past, Inanna and Dumuzi. At about the middle of the ritual, we were called to enter as god and goddess. We had planned an interaction where Dumuzi unsuccessfully courted Inanna with strawberries in the South, and then whipped cream was added in the West. In the North came bread, and finally, in the East, honey was added. The honey finally won Inanna’s heart and they kissed. They then proceeded to give honeyed bread and strawberries and cream to the several hundred energy-raising, dancing participants. Evocation worked here in part because of our past relationship with the deities, the time in private to evoke their essences before entering, and a basic script to follow without words. Even though we have little real acting ability, the evocation of these familiar deities was perceived as powerful and authentic.

When invocation and evocation are successful, the authenticity of the experience is immediately felt by participants. These two methods are differentiated because they provide distinctly different experiences. Because deity is allowed to take possession of a spirit worker in invocation, we have to let go of any scripting for the ritual. An invoked deity will do, speak, and act as it pleases, and the connection can be lost at any time. That possible interruption needs to be incorporated into the planning.

During invocation, a deity might speak either to participants individually or to the group as a whole. The deity might act out a story or express emotions relating to your ritual purpose. Some specific devotional rituals are solely designed to provide a community with deity interaction.

During evocation, the spirit worker will have awareness and more control over what happens. The actual “summoning” uses words that are designed to resonate with the human subconscious, and speak specifically to the deity who is being called forth. Once the evocation is successful, the spirit worker can offer the essence of what the deity intends to communicate.

Bacchus, Dionysus, or Pan might be chosen for a celebration. Diana and Inanna have “warrior” and strength associations. Pele is the fire goddess of volcanoes of the Hawaiian islands and would work to support transformation themes. A devotional ritual can accommodate more education for your participants about the deity’s nature before aspecting takes place. Deities who are commonly known and resonate with the ritual purpose are most often the best choice.

You should only attempt either of these methods with the help of a skilled spirit worker. These techniques are only appropriate within a sacred context, where spiritual possession will be accepted. Both of these interactions are more likely to be welcomed in a community where they have been experienced before.

Interactive Iconography

Ritual uses the language of symbols, metaphor, and allegory. Say your ritual theme has transformation as its goal. Plant a seed, crack an egg, pour water, pop a balloon—all these actions demonstrate change. You can show your participants what transformation looks like, or you can make it possible for them to use their hands and do it themselves. Doing trumps observing every time. When each person is given the opportunity to effect that change, on a subliminal level they know for a fact they have that power. When we experience this in ritual, it integrates the memory of transformation and our capacity to create change.

Your ritual intent can be symbolically translated by using one well-designed prop as a focal point. How could this be added to, written upon, or somehow touched by everyone? Whether a shrine, special gateway, or the main prop focal point, you can provide writing or drawing tools, strips of cloth, ribbons, string, stick matches, feathers, or almost any item to decorate it. For devotional rituals you might include an opportunity for each participant to add a written prayer or symbolic addition as a demonstration of connection to the deity. Allowing participants to add their own pieces to a ritual element gives them a sense of ownership of the ritual intent. Touching something forges an energetic connection to it. This connection endures long after that direct touch is severed.

Example

In the ritual “They Will Remain,” we used two life-sized pieces of clear acrylic framed in wood with stake legs supporting them to make two low tables. Participants used carved potato printing blocks and paint to stamp on the sheets. (We also had a bucket of water and towel if they made a mess of their hands.) We had precut the adhesive film that Plexiglas comes with into male and female outlines and removed that portion of the film. The potato block designs had specific patterns on them (flowers for Flora, seed and leaf images for Jack in the Green). Later in the ritual we removed the film outside the figure outlines, revealing the male and female images fully painted. They were then mounted vertically on poles to form a gateway to exit the ritual. This echoed the two earthy deity figures who were invoked and called into the circle, and then exited the ritual.

Gifts

A great way to embed the intent of your ritual into your participants’ consciousness is to have them be given, make, or in some way personalize an individual token. If this is something they then take home, it will become a direct reminder of the experience. We are handed items daily that have no meaning, which we toss as soon as we see a trash can. How do we make this item memorable? If we incorporate a symbolic focal point into the ritual, the gift can be a lasting representation of this larger image. If you create a tree to represent your community as a focal point, you might use a small disk of wood with a tree image burned into it as a gift. Many ritual intents include a reference to beginning a new path based on the ritual experience. Cement this intent within participants by giving them a seed. Use an acorn, sunflower seed, pomegranate, popcorn, or any garden seed as a gift to remember their new start. Add writing, carving, a container (such as a bag), or color marking to make it more personal and connected with the ritual moment.

Example

You may have created a prop to interact with, add to, or decorate. Design it so later in the ritual a piece of it can be disconnected and given to each participant as a gift. You might use a plant or tree prop (replicated, handcrafted, created in ritual, or artificial) to interact with. Later, remove the leaves and present them as a gift of remembrance or symbolic reference to participants.

A gift is something given. Seems simple enough, but to be effective, how it is given is critical. It could be something each person receives upon entering the ritual space. This works well if participants don’t need their hands free. Will they be clapping? Joining hands? In that case, a gift that is worn, like a bead strung on a cord, works better. A gift necklace is in contact with the person and their awareness through the balance of the ritual. We have offered clay bead necklaces for many years, which are made in advance using press molds (see chapter Twelve). The first ritual then includes the giving of this gift to every participant, to be worn throughout the coming week. We have found people wearing and treasuring this gift years later, as a reminder of that week’s experience.

Rather than simply putting your gifts on a table at the entrance or exit of your ritual, have a person actually bestow them. The giver can imbue them with relevance through their manner. If they are handed out like a high school worksheet, they will be received with that much significance! A common stone can be a gift, and the right presenter with dramatic technique can make it seem like the most important, magical stone ever received. Personal interaction such as intentional eye contact, a special touch, an anointment, and even a kiss can become the “wrapping” that binds the ritual purpose to each participant’s awareness.

If the gifts you provide are all unique, a random draw by participants works to make them feel the one they receive is meant for them. If you use this method, make them draw without seeing the individual items, from a bag or a raised basket or bowl. If you allow participants a visual choice, invariably some will want to take a minute to dig through every gift and find their preference, slowing the process.

Having participants pass or give gifts to each other can be powerfully bonding. This is a technique suitable to support a fellowship ritual. Modeling by ritual team members is a good way to use this technique. There is a risk in that process: the community-building aspect of participant giving can easily be diluted by a casual or insincere approach. Often in producing community ritual, the role of passing something out is assigned moments before the ritual. Communicating the importance of the manner in which every role is expressed is necessary, and particularly in giving of gifts.

Written affirmations can be a gift your people give to another participant. Writing materials for a large group take a lot of management and planning to successfully work without bogging down a ritual. To streamline the process, offer another activity at the same time, maybe a song or chant. We all think our handwriting is perfectly legible, but it often isn’t to others—something to consider if this is to serve as a gift.

Before closing the ritual, somehow connect the token to the emotions that the ritual has generated. Once linked to the subconscious, every encounter with this symbol will help them re-experience it. We do this by ‘‘energizing” the gift to anchor these feelings to take home and use in individual transformation. Have participants pass their gift through a small flame, dance with it, anoint it with holy water, or toss it in the air! This group act, charging a gift with intention, can easily become the ecstatic portion of your ritual.

In “Ritual to Enki, the Father,” a pierced clay disk with a male figure embossed on the surface was incorporated into the two scrolls forming the “ME” (laws of the gods of Sumer) prop. Seventy-five disks were laid on edge and then surrounded with metal screen and paper to create the scroll-tube look. During the energy-raising portion of the ritual, the ME was added to the fire, and after completion, the discs were unwrapped and given with a cord by Enki to each participant as the ritual ended. This connection of the group energy, deity, and the gift cemented its importance to the ritual experience.

Charging, or energizing, can be a mystical, metaphysical act, harnessing and focusing the will upon a ritual symbol. This is great if you work with a community that has a common experience and belief in that power to energize by will alone. Energizing is also a simple and verifiable experience. Take a room of quiet people and get them all clapping, and the energy of the room is completely different. It has changed from passive to active.

A brief period where ritual participants hold, look at, or engage a ritual symbol or gift is appropriate to establish your focus. For them to really take it all home, most people need something a little more active! Write a chant or find a suitable song to help integrate the gift with your intention. The more creative you are at integrating and making connected and relevant this energizing of the gift with your ritual intent, the more successful and memorable it will be.

Altars and Shrines

In a religious context, an altar is any structure upon which offerings, devotion, or sacrifices are made. Permanent altars are usually found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. In community ritual, altars can have a very practical purpose: a place to keep whatever physical tools, props, or devices you will need to have access to. There is no requirement for a ritual to have an altar. Many rituals have other focal points, and the tools that team members need can be carried in pockets, bags, or baskets.

When you do include one or more altars or shrines, you must recognize them as a focal point for participants. If you acknowledge the four cardinal directions as forces to aid or protect you, an altar, shrine, banner, person, or some physical object is useful to mark them. Each direction has hundreds of natural and symbolic correspondences that can be incorporated. Because of their religious origins, the altar itself and the area around it are seen as endowed with greater holiness. It is a mistake to place an altar without care or attention to detail. For whatever the purpose, it becomes a focal point, and if it appears unimportant to you, that casual concern will get transferred to an assessment of the balance of your ceremony.

Altars do not have to be elaborate to be beautiful additions and support your ritual theme. A handsome cloth can cover a rusty TV tray table or an overturned storage tote and provide just what you need with thoughtful and well-placed decoration. In a ritual working with the nature of the year’s 13 moons, we divided the large group into 13 smaller groups to have a personal experience with each moon. Most moons had their own interactive altar, and on the main central table all that was present was a large-scale hourglass prop, used to both regulate smaller groups moving from station to station and to symbolize the passage of time.

However you include an altar, treat it as a sacred focal point. A powerful altar is a representation, a microcosm, of your ritual intent. Every item present should be carefully chosen and placed so when the participant looks at the altar, they can understand the reason behind it.

A shrine demonstrates devotion to a deity, ancestor, hero, or similar figure of awe and respect. Since it is specifically designed to honor, it is usually larger and more involved than an altar. A shrine should be well thought out to include every aspect and sensory addition that the focus of the shrine would want. Shrines furnish a place or method for visitors to express their devotion. Classic offerings you might provide are lit candles or incense, food, water, wine, flowers, coins, a bell to ring, or a guest book for any personal mark or writing. You could have participants each create a small prayer or message to add. This can be written on paper, cloth, or bark or offered for burning to a fire or candle.

Shrines serve as a tangible form to express what might be happening inside us. A community can, through this act of creation, move past strong emotion, especially to help heal the pain of loss or tragedy. Shrines help us remember, reflect, grieve, and honor the losses that individually overwhelm us in the moment. Making and adding to a shrine can itself be a ritual. Shrine building lends itself to the spontaneous creativity of many hands. Often all that is needed is a pile of supplies, a basic support structure, and permission to play, and an incredible sacred space will appear!

Keep in mind that both altars and shrines are tools. They’re meant to help you, not become an obligation or burden to your team or the ritual. In most community rituals, they are set up before and taken down after the ceremony. In those cases where you have a secure outside or reserved inside location, structuring in participant access to a shrine or altar can be a great way to create engagement before you even gather, and long after the ritual ends. You might design an element of a shrine to be preserved and portable and arrange further public display and interaction with it. The pentacle constructed of brooms during the Veterans’ Pentacle Rights Ritual (described in chapter FOUR) was displayed as an interactive shrine in several locations over the next year. Visitors added their own ribbons as offerings and prayers.

Ritual Props and Decorations

The ritual experience is magic. When community ritual helps people view and experience themselves and others in a different way, it opens a doorway for participants to transform themselves. This can be in deeply profound and personally immediate ways, or in perceiving themselves as truly spiritual beings, alive within a spiritual world.

A ritual prop (from the theatrical term “property”) is an object used by ritualistas to further the intent or experience of a ritual. Your props should also be part of your site decoration, but not all decorations are props. The difference between a decoration and a prop is use. If the item is not touched or symbolically interacted with by a ritual performer or participant, it is a ritual decoration. Ritual decorations will support your ritual through one of our perceptual senses. A shrine that is only a visible support for ritual is a decoration; when participants make an offering or somehow energize, engage, or contribute to it, it becomes a prop.

Props and decorations are not essential, but they can be really useful. Unlike a repeated theatrical performance, community rituals are usually a one-time event, and often props are destroyed or have only this one use. Why then would we go to the effort and expense to add these to a community ritual? The answer is within the nature of the ritual experience.

Many of us have been raised with skepticism. We have been disillusioned by our experiences and may come to a group ritual with the attitude of “I’ll believe it when I see it” rather than from the mystical place of “When I believe it, I will see it.” That is to be expected. Props and decorations bring to ritual a sensory experience that can reinforce our unspoken beliefs, so we begin to see it with our own new eyes.

Ritual props can help us suspend disbelief, shedding the common perceptions, laws of nature, and foundational truths we live by. We can then be open to magical and mystical perception of our world and ourselves. The power of symbology to engage the subconscious can be integrated into most props and decorations. One of the best gateways we have seen in an outdoor ritual was also one of the simplest. It was a 7-foot-tall vulva-shaped doorway made of bent saplings tied together at the top. Hanging from it was a child’s globe of the earth, like a clitoris. It was used for a ritual to connect with the essence of Gaea, and made a perfect symbolic entryway for this ritual, literally and symbolically entering the womb of Mother Earth.

How you integrate props and decorations into your community ritual is often limited by time, energy, funding, and personal commitment. Since we rarely have unlimited amounts of any of these, we need to prioritize which areas of our ritual will benefit most from the support props offer. Look again to your ritual intent: what did you come up with?

For a celebratory intent, you may want decorations that are visually exciting. Design a gateway adorned with flowers or bright colors, a seasonally decorated altar, or a boundary laid in pebbles, sunflower seeds, or cornmeal. Oversized, exaggerated ritual tools or costumes make a statement seen by all. Display a robust feast to create a feeling of bounty or celebration.

For a rite of passage, focus prop design on the transformation. Use a physically or visually challenging entry. Set up a pictorial history altar documenting the passage. Design a prop that changes shape or viewpoint during the ritual, something that transforms itself to echo the particular nature of the rite being celebrated. The symbolism of the seed or an egg can be easily adapted into functional props in a rite of passage.

For guided meditation rituals, auditory props can be really effective. Create a mini-waterfall, add nature sound effects (crickets, frogs, birds, rustling, or wind noises), provide a relaxing atmosphere, or offer comforting smells. A labyrinth pattern of movement laid on the ground either as a pure walking experience or with altars or other personal props along the route is effective in these types of rituals. One of the best gateways we have used is the gong gate.29 This is a pair of decorated 2-inch PVC supports slid over fence posts. Hung from these is a series of lengths of metal pipe cut to sound a pentatonic scale. Participants walk through the gate as these gongs are played with soft mallets, surrounding them with sound.

Rituals that deal with highly emotional or confrontational internal themes can incorporate the visually ominous, calling up cultural archetypes and stereotypical images to stimulate emotions. Imagine what death, sorrow, fear, pure joy, or elation might look or sound or feel like. Classic images of death are skulls, bones, and decomposition. Imagine an improvised tent that isolates participants for a moment in complete blackness. What is it like to emerge from the darkness of the womb to the light of day? How can you symbolically recreate that transition?

For a sense of mystery, we have used characters dressed in black leotards with outlines of white bones traced upon them. We decorated their faces and gave them black gloves with small round mirrors hot-glued to the palms. These characters surrounded the ritual area, dancing up to participants and offering their reflection. Well-designed props need no explanation. Their symbolism should be obvious or their mystery part of the intended design.

Illusion

Nels: As a prop-building enthusiast, my greatest joy is designing props that create a magical space for personal growth or transformation. I have come up with amazing props to “launch” people into a state where the intent of the ritual can take place. There are illusions from the stage, the circus, and even chemistry class to draw from.

Classic magic-show illusions can be adapted to the ritual stage. Imagine receiving a gift in ritual that magically appeared from behind your ear. Sleight of hand is difficult for an amateur to master, and these skills need to be convincing if you attempt to use them! Mirrored illusions, magical appearances, and mid-air suspension of items require planning and the audience’s directional viewpoint. The physical transformation of one prop into another makes a powerful statement of change. Flash paper that seemingly burns from nowhere and disappears may be an old trick, but it still works. We used a “true mirror” in ritual to allow participants to see how they really look to others. It is a device with multiple mirrors that shows you your image exactly as others view you, rather than a reversed reflection.

The elemental forces of nature, displayed in an innovative way, can help generate within the participant that suspension of disbelief which is essential to wonderment. Many of your most effective prop designs can be inspired by the amazing properties of the physical world. Remember that foaming volcano you built in elementary school? How about two cans and a waxed string stretched between them as a telephone? The arc of static electricity moving between two poles. The echo of voices in a large canyon. Magnetism can make items move or form shapes without any apparent cause. Even the simple explosion of popcorn can be fascinating! Chemical additions to flames can magically add unique colors. The myriad forms of combustion and fire trickery, when in an outside space and safely presented, touch some of our deepest fascinations.

It is critical to design prop interactions to flow smoothly and quickly with large groups of participants. You may need multiple paths so several people can have an individual experience at the same time. Thorough testing and rehearsal are needed to ensure that all props work and are safe, the timing is well understood, and the actions will not slow the whole ritual down.

As with every part of ritual, effectively executed is best. Fantastic props or illusions that don’t quite make it have the opposite effect on the mind. It is easy to get distracted and over-emphasize props in your efforts; they are just so much fun! Keep their use in perspective with the overall flow of your ritual. One really well-designed prop is more memorable than five that drain your effort and don’t quite fit the ritual or move participants to better experiencing your intent. Sometimes your prop ideas are all so exciting, you are tempted to include them all. Resist, and save some to adapt for your next ritual!

Ritual: They Will Remain

Location: Sacred Harvest Festival, 2006

© Judith Olson Linde and Nels Linde

Ritual context

This ritual uses a standard opening which we have often used for a series of rituals with a unifying theme. The standard ritual opening supports the overall theme but is repeated in each of an arc of rituals. This has the effect of creating a unifying element between the rituals and evoking the feelings experienced in the previous one. It also has the advantage of allowing us to put increased effort into refining one good opening, and then having it ready for the next ritual in advance. It allows participants to focus on the rite knowing already how the space is made sacred. The entire series of rituals was written in rhyme. This ritual is a great example of participants creating an iconic prop, connecting it with live deity figures, and seeing the prop transformed during the ritual.

Ritual intent

Reawaken our awareness of the forces of the natural world. Where do we fit, what do we face? Male and female, an inspiration, gift, and magical resource. Join in, lend a hand, build a shared vision.

Ritual description

Maybe not within our lifetimes, but quite possibly in those of our children, the “beauty of the green earth” may have been paved over completely, the “white moon amongst the stars” might be just another venue for advertisement, the “mystery of the waters” might be how we can find any clean enough to drink, and the “secret desire within the heart” may be to get back to the way it was. In my despair I try to keep perspective, I try to remember that the forces of nature are beyond our control, that only life can generate more of itself, and that without constant tending, the trappings of civilization would be swallowed up by Gaia’s regenerative force. This ritual is about being touched by the archetypes of that force, and a reminder that “When we are gone, they will remain.”

Ritual setup and supplies

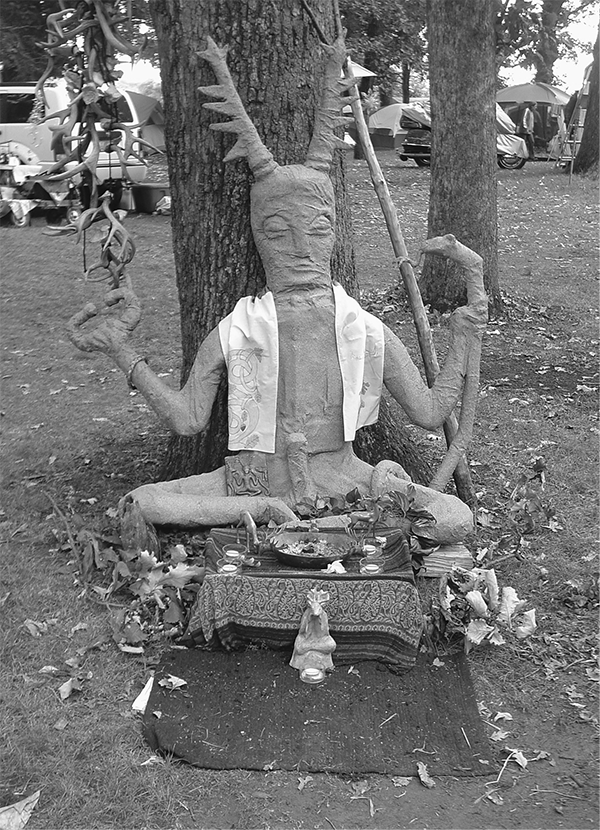

Two 2 x 6-foot panels of acrylic, with the clear protective sheet cut out to form a resist mask of silhouetted figures with arms raised (masculine on one panel, feminine on the other). Each panel has a wooden 2 x 2-inch grooved edge as a stiffener. They have two pipe flanges on each edge for later vertical mounting. Each panel is supported on the north side of the ritual circle with 1 x 4 x 24-inch notched stake supports, three on each side. Panels are parallel and about five feet apart. The panels are designed to be removed and then inserted and held vertically in metal rod stakes forming an exit gateway. Several bottles of craft paint: pastel pinks, blues, and white for Flora; greens and browns for Jack Green. Several stamps cut from potatoes: for the Jack designs; acorn, leaf, lizard, handprints; for the Flora designs; spiral, dragonfly, butterfly, flower bud. Metal pie pans for paints. Four elemental altars on the circle, with supplies for the altar experiences: North, a small stone; East, a bowl of fairy dust glitter; South, a tiki torch; West, a bowl of water, a sponge, and a stone with a hole through it. Each altar team set a division, a small separation, in front of their altar to allow a bit of privacy for each festivant’s passing. Cots for the deities to lie in state. Acorns and flower petals.

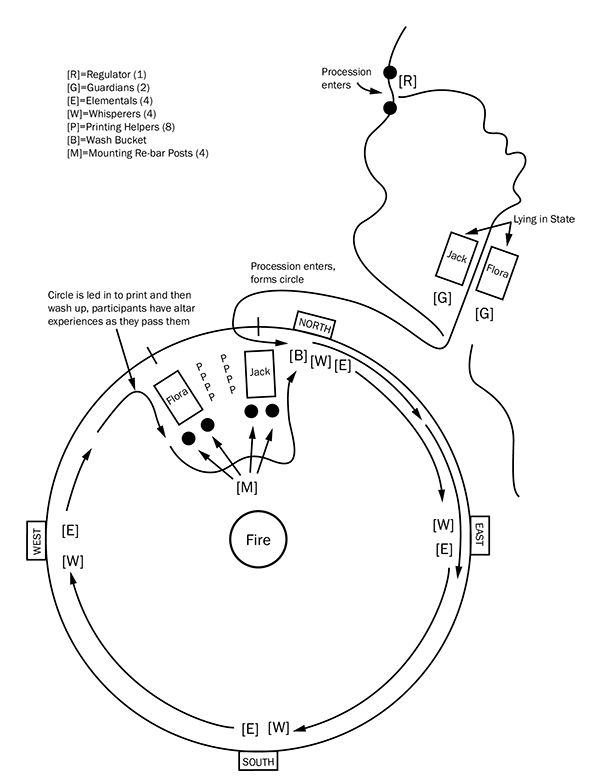

Diagram key

- • [R] = Regulator/Greeter (1)

- • [G] = Guardians (2)

- • [E] = Elemental experiences (4)

- • [W] = Whisperers (4)

- • [P] = Printing helpers (8)

- • [B] = Wash bucket

- • [M] = Mounting rebar poles for exit gateway (4)

Team members

Regulator/Greeter; Flower Face; Jack Green; four elementals with potato fork (N), broom (E), scythe (W), and staff (S); two guardians; Ritualista 1 and Ritualista 2; eight block-printing helpers; hand washer; choir. (Four altar experience helpers were recruited in ritual.)

Ritual script

The festivants processed to a woods path where each was greeted by the Regulator and warned: “Touch not what you see on the journey.” Festivants walked the wooded path that led to the East ritual area gate.

Flower Face and Jack Green were the god and goddess of the wood. They were in costume, painted, and covered in flower petals and acorns, and were lying in state on cots along the path. Guardians were in place protecting them.

Standard folk ritual opening

The festivants entered through the gate and formed a circle. Four elemental team members wandered around outside the circle as if no one was there. They carried a potato fork (N), broom (E), scythe (W), and staff (S). Entering the circle, they took their respective places in front of altars, facing into the circle. Ritualista 1 entered the circle with a rhyming chant:

“In a clearing on a moonlit [cloudy, twilight] night, illuminated by firelight,

Assembled here we circle round, to see what blessings can be found

In the company of other folk, and what magic we may invoke.”

Ritualista 1 paused at each direction and signaled with a tambourine, saying a simple rhyming call:

(East) “Where the moon rises and dawn breaks the day, on scented breeze newness wafting our way.”

(South) “To the South lie the sands of fire, choices made, the loin’s desire.”

(West) “In the West the misty shore, rainbow’s end, the ocean’s roar.”

(North) “To the North the mountains of stone, caves of my ancestors, antler, bone.”

As Ritualista 1 mentioned each direction, each elemental team member turned to their altar, lit their candle, blew a kiss to their direction, and then turned back toward the inside of the circle. Rotating slowly in the center with her arms out, the Ritualista continued:

“The Lord and the Lady are present here too, and spirit, as always, within each of you.”

Ritualista 1 walked the circle, saying:

“What they call progress in our day is watching nature slip away.

As every hour more acres fall to industry and shopping mall.

Whooping crane flies the open field, a vision of wonder to me revealed.

Her habitat shrinks every day. How long can it go on this way?

All life is programmed to succeed, from man to whale to tiny weed.

And if unbalanced would indeed replace all other life on earth,

Man’s vanity is Gaia’s curse.”

Ritualista 2 continued:

“Yes, but Gaia lives, and rules this land with balance, wisdom, and steady hand.

The blight for us seems evermore; for her it’s just an open sore.

Her fecund power fills the night with verdant bounty and savage might.

When we have need she shares with us. Now, take her seed and plant it thus.”

Ritualista 2 demonstrated printing the panels with the potato stamps and paint, and then, beginning just left of North, the participants were led into the circle to paint/print the panels. Quiet percussion accompanied this work.

Prop activity detail

The two panels were arranged in parallel between the gate and the central fire. Between the panels were eight assistants, paired up back to back, four to each panel. They each held a pie pan with a different color paint and a potato stamp. The line of participants, drawn from the circle at the North, moved south toward the central fire outside the Flower Face panel, and then back north along the outside of the Jack Green panel. Participants added one or more prints for each panel. If a participant was too enthusiastic or meticulous, they were told, “Less is more.”

The festivants then all proceeded around the circle deosil (clockwise) and at each altar had an encounter. After completing their printing, the participants continued in a line to the experience at the Earth altar. The Earth team member took each person one by one and whispered an elemental wisdom riddle:

Earth: “Some things you cannot change, you can only feel.”

The Earth helper (spontaneously recruited from the circle) held the participant’s foot and dropped a small stone on it. The participant was sent deosil to the next altar, and the Earth team member took the next in line from the completed printing circuit.

Air: “Some are here for a moment and then gone.” The Air helper put fairy dust glitter on the participant’s hand and blew it away (not toward their eyes).

Fire: “Some are bright and affect us forever.” The Fire helper took the participant’s hand and waved it through the tiki torch flame (high enough to be warm but not burn).

Water: “Some move through us without us knowing.” The Water helper poured water from a wet sponge through the hole in the stone onto the participant’s hand.

The festivants rotated around the circle until they passed the four altars, then continued around again, following the line of festivants until all had completed the four altar and printing experiences as they passed them, and were back in their original positions around the circle.

Ritualista 2: “We invoke and call Flora and Jack in the Green to come to us from their wooded home.”

Ritualista 2 led all in chant as Flora appeared out of the forest and entered the circle: “Flora, green lady, gold berry, petal maid, rise again … come to us.”

At the end of the chant, Ritualista 1 said: “She blossoms from primordial mud.

First seed, then root, then stem and bud.”

He then began the chant to Jack Green: “Woods wise, green man, horned one, Jack, rise again … come to us.”

Jack Green appeared from the forest and entered the circle. The chant ended and Ritualista 1 said: “Honey of love, from the dark he is born, to rise with the sap and sleep with the corn.”

Flora and Jack Green went round the circle with baskets and handed out flower petals and acorns, respectively, to add to each person’s “folk magic” pouch (received as a gift in an earlier ritual). While this was happening, the ritual guardians raised and moved the panels to their vertical exit gate positions, insert the mounting rods through the panel brackets and into the earth. The print helpers removed the panel-printing support stakes and all printing and washing supplies.

These activities were accompanied by the song “When We Are Gone,” by Anne Hill and Starhawk. When the gifts were all given, the song ended, and Flora and Jack Green together removed the masks from the panels to reveal the male and female silhouettes, and then stood facing each other. For the ritual exit, they created an archway by touching hands as children do in the game “London Bridge Is Falling Down.”

Ritualista 1: “We’ve gathered in the moonlight, in our home under the trees.

We cast our sacred circle and shared the mysteries.

Remember the healing of the fire, the trust of tribe and kin.

Remember the touch of nature’s core, the power you have within.”

Ritualista 1 took up a combined basket of acorns and flowers and walked once around the circle, tossing a few at each altar as the candles were extinguished by the elemental team members and they blew a kiss to each direction. She ended at the North and exited through the gateway created by Flora and Jack Green, followed by the elemental team members, who aided in the festivants’ departure from the circle.