GARETH FISHER

On May 22, 2010, I was sitting in the guest office (ketang 客堂) of the Temple of Universal Rescue in Beijing (guangji si 廣濟寺) talking to Master Mingyi, the monk on duty that day for receiving questions from visitors to the temple, when a young couple entered the room holding several bound books and small stapled booklets.1 They explained to Mingyi that they were new converts. The previous day had been the fifteenth day of the fourth lunar month, when the temple holds its largest lay-conversion ceremony (guiyi fahui 皈依法會) of the year. As they had been leaving the temple following the ceremony through a large outer courtyard, the couple had been offered much free Buddhist literature. There were the sorts of books and booklets they had with them, as well as homemade handouts typed and photocopied on A4 paper. They had also been offered video recordings of sermons by famous masters and laminated pictures of well-known Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Laying the books and booklets they had brought on the desk in front of Master Mingyi, they explained that they wanted to learn more about their new religion but did not know where to begin. They wanted Mingyi to tell them what to start reading first.

Glancing only briefly at the materials, Mingyi told these new practitioners that they should disregard them all. His first words were that the materials were daoban 盜版 (fake, pirated). He went on to explain that they were not authoritative teachings but examples of a mixture of authentic Buddhist teachings and heterodox religious views. He advised the couple to go to the temple’s bookstore, where they could purchase both authoritative Buddhist scriptures and other introductions to Buddhist teachings that the temple authorities had approved. I do not know whether they followed his advice, but the couple thanked Mingyi and left.

This short meeting between these two new Buddhist practitioners and a temple monk is illustrative of an ordering practice through which lay Buddhists in post-Mao China, while often identifying themselves as followers of a single tradition, are led to embrace different kinds of teachings, particularly with respect to the moral orientations of those teachings. As the number of studies on Buddhist practices in post-Mao China grows, the picture they form of who practices Buddhism in China today and why emerges as one of sharp variation. Some studies, such as Dan Smyer Yü’s recent monograph on Han Chinese converts to Tibetan Buddhism, focus on how upwardly mobile lay Buddhists deeply immersed in a globalizing capitalist culture create spiritual relationships with faraway masters to resolve what they perceive as a “spiritual crisis” (jingshen weiji 精神危機) in contemporary Chinese social life.2 Other studies, such as Zhe Ji’s analysis of Chan summer camps, emphasize how well-educated young people are turning to Buddhist meditation practices as a form of personal ritual that makes little commentary on present-day social affairs.3 I have previously demonstrated how Buddhism appeals to certain socially and economically marginalized residents of Beijing as a refuge in what they see as a morally corrupt world.4 Some studies represent both monastics and laypersons as closely integrated into a market-based world of economic venality and wealth accumulation,5 while others discuss the formation of Buddhist communities that enable their adherents to escape and even to resist the growing influence of consumerism.6 How can we make sense of these different findings? How might we understand what links or separates different practitioners with varying religious orientations, all of whom claim to be practicing Buddhism?

Attempts to conceptually order religious practice in post-Mao China have been offered mostly by sociologists of religion. Of these attempts, the best known is Fenggang Yang’s tripartite division of red, gray, and black forms of religion.7 This typology classifies religious practice in terms of its degree of tolerance by the state, with red forms falling into legal religious practice, gray forms into an area of technical illegality but with little interference from the state, and black forms falling into a forbidden, illegal zone. In adapting Yang’s model to the sociology of Buddhism in post-Mao China, Alison Denton Jones and Sun Yanfei focus on how lay practitioners have pursued practices of Buddhism that fall into the gray and black zones.8 Some of the practitioners whom Jones studied specifically expressed dissatisfaction with legal, temple-based practices of Buddhism, which they felt were tainted by both their association with the official control of the state and monastic interest in obtaining money and influence from wealthy devotees who understood little of the deeper meaning of Buddhist practices.9 Sun and Jones also show how participation in these different politically defined communities relates to different kinds of Buddhist practice.

While the studies of Sun and Jones show important distinctions among persons and groups labeling themselves as “Buddhist” in China today, I suggest that Yang’s model of categorizing religious groups based on the degree of state tolerance for their activities presents an incomplete picture of Buddhist religious diversity in post-Mao China. Unlike most Christian groups, the inspiration for Yang’s model, Buddhist groups and activities are not always coordinated by the centralized local authority of a religious leader such as a priest or minister; even in a legal Buddhist religious site, a wide range of religious gatherings and practices take place that may or may not have any relationship to state-approved religiosity. As a result, it is difficult to discuss meaningful differences in religious orientations among self-identified Buddhists based primarily on an examination of the degree of tolerance shown by the state to Buddhist institutions.

As an alternative way to make sense of Buddhist religious diversity in post-Mao China, this chapter proposes a model that has been used by historians and anthropologists, that of the textual community. The concept of the textual community originates with Brian Stock, who used it to describe new groups that emerged around the critical discussion of religious texts in medieval Europe during an increase in literacy.10 Stock notes that not all members in these groups were themselves literate, but they participated in discursive groups directed by specialist interpreters who were. Writing on the evolution of Sri Lankan Buddhism in the seventeenth century, Anne Blackburn modifies Stock’s framework to argue that, in this Buddhist case, textual communities can sometimes emerge around the interpretation of multiple texts and may generate, in turn, multiple interpretations of those texts.11 Joanne Rappaport uses the concept of textual community to observe how the Páez of Peru use the concept of texts, particularly in ritual, to distinguish themselves from other groups.12

I build on the insights of these scholars to use the model of textual community as a type of discursive community where people belong to particular social (and, in this case, religious) units based on whether they share the reading and discussion of a particular set of texts. I use the term “text” broadly to refer not only to printed matter but also to multimedia materials such as the DVD sermons of famous masters or both textual and streaming visual materials available online. While contemporary Chinese Buddhists possess a much higher degree of literacy than did medieval Europeans or seventeenth-century Sri Lankan Buddhists, their practices also often center on a figure or series of key figures. These key figures, whether monastics or lay preachers, both interpret for them materials that surpass, even slightly, their level of literacy (such as sutras written in literary Chinese) and also help them to digest key messages in the vast corpus of Buddhist materials available in China today. They also serve as gatekeepers who, like Master Mingyi at the Temple of Universal Rescue, direct Buddhist practitioners toward particular texts and teachers and away from others, thus solidifying the boundaries of these discursive groups.

Understanding the religiosity of Chinese Buddhists in terms of their relationship to texts is particularly appropriate in the modern period, where, as the chapters by Jessup and Scott in this volume indicate, Buddhists have used the publication and dissemination of books and periodicals both to position Buddhism within a modern Chinese public sphere and to unite particular groups of Buddhists around a shared set of discourses and under the umbrella of a particular religious authority. Notable cases include the World Buddhist Householder Grove (shijie Fojiao jushilin 世界佛教居士林), studied by Jessup, which published its own periodical, and Taixu 太虛 (1890–1947), who, as Scott shows, used publications such as Awakening Society Collectanea (Jueshe congshu 覺社叢書) and Voice of the Sea Tide (Haichaoyin 海潮音) to unite Buddhist readers under his reformist views.13 Just as advances in print technology such as mechanized movable-type printing enabled Buddhists in the early twentieth century to use written texts to insert Buddhist discourses into an emerging public sphere of literate elites, further advances in technology in the form of the word processor, inexpensive photocopying, and, later, the Internet, along with dramatic increases in literacy rates, have made it possible for even Buddhists of very low socioeconomic status to create and disseminate a wide range of Buddhist-themed publications. An analysis of the different forms of media that post-Mao Buddhists create and distribute along with an ethnographic-based exploration of how those media are exchanged and used can illuminate differences between elite and nonelite forms of Buddhism in the post-Mao period.

The following discussion considers the historical background to the type and availability of Buddhist religious materials in post-Mao China and then delineates three broad types of Buddhist textual communities for this period. These are (1) teaching-centered communities based largely on particular schools of Buddhist thought, such as Chan; (2) master-centered communities, sectarian-type Buddhist movements centering on the spiritual instruction of a particular monastic or lay teacher who usually produces their own closed sets of texts and multimedia materials; and (3) a free-distribution textual community centered on the writing, printing, and distribution of a wide variety of Buddhist texts and multimedia materials on different Buddhist topics that are exchanged and discussed at state-recognized Buddhist temple sites.14 The subsequent discussion points to how differences in the membership of these textual communities is closely connected to differences in social class, which, in turn, are reflected in the various content of the texts themselves and the discussions that surround them. The conclusion of the chapter discusses how examining Buddhist groups in China today as largely nonoverlapping textual communities can help scholars enrich their understanding of how the same “religion” can function very differently for different adherents, especially those who differ in social class, and, furthermore, that, by categorizing religious groups into different textual communities rather than different “religions,” we can find that individual religious groups are often more socially homogeneous than they might first appear.

REBUILDING BUDDHISM IN POST-MAO CHINA

The reading and discussion of religious-themed texts have played a key role in both the global history of Buddhism and the history of religion in China. While the late imperial and Republican periods saw a further enhancement of this role,15 the coming of the Communist period presented challenges to the circulation of Buddhist media, and, during the Cultural Revolution, Buddhist scriptures, commentaries, and other textual materials from hundreds of years of Buddhism’s history in China were destroyed. In the 1980s, many political restrictions on Buddhist practice were lifted, but, like their late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century counterparts who had to recover from the destruction of the Taiping Rebellion, those Buddhists who survived the Cultural Revolution were faced with the significant challenge of obtaining needed scriptures and ritual manuals for their own monastics as well as providing introductory texts to evangelize the religion to a new generation of would-be lay converts.

Initial support for reintroducing these materials came from overseas Chinese, whose Buddhist communities had earlier been established by Chinese missions mostly in the early part of the twentieth century.16 Influential overseas Buddhist leaders such as Jingkong 凈空 (b. 1927), a monk born in Anhui province who later lived in Taiwan, Singapore, and Australia, facilitated the donation of large quantities of Buddhist scriptures as well as his own interpretive texts.17 Buddhists in mainland China added quickly to these collections themselves. Since at least the past dozen years or so, the vast majority of religious materials distributed in mainland Buddhist temples have originated in the People’s Republic.18

While the state has been less restrictive toward religion in the post-Mao era as compared with the Maoist era, it has not permitted a wholesale freedom of access to religious materials. In theory, the government restricts the distribution of religious-themed media to approved religious sites (zongjiao huodong changsuo 宗教活動場所). Legally permitted religious associations are also charged with controlling the content of these distributed materials at their sites. In the Buddhist case, however, such control is mostly nonexistent. Moreover, in spite of government restrictions, Buddhist texts and multimedia materials are also available through other means: the government’s policies of economic liberalization have led to the commercial sale of Buddhist texts, periodicals, and video recordings at bookstores throughout the country, albeit to a lesser extent than that achieved by religious publishing houses operated by elite Buddhists of the Republican era. Another growing area of availability for Buddhist texts and visual materials is the Internet.19 Apart from websites associated with banned groups such as the Falun Gong 法轮功, the Chinese authorities take little interest in regulating Buddhist-related content online.

TEXTUAL COMMUNITIES AND CHINESE BUDDHISMS

Turning to the three broad types of textual communities of Chinese Buddhists in post-Mao China, I begin each section with an exemplary case in order to provide concrete examples of these communities in practice.

Teaching-Centered Communities

In July 2011, I visited, for the first time, Bailin Chan Monastery 柏林禪寺 during its annual Living Chan Summer Camp (shenghuo Chan xialingying 生活禪夏令營), a weeklong retreat for young adults interested in learning about Chan philosophy and experiencing life at a Chan monastery (figure 7.1).20 On my first day, I spoke to a young man (aged nineteen) who was attending the camp after having just finished his first year at university. Like the other campers, he had registered online at the monastery’s website. In the course of this and several other conversations we had over subsequent days, he explained to me how he had become interested in Chan teachings through a combination of online readings from Chan-based websites and introductions to Chan teachings by Jinghui 淨慧 (1933–2013), the former abbot of Bailin Monastery, that he had purchased at a bookstore. As we talked that first day, two other participants in the camp approached us. One was carrying a volume containing a transcript of the previous year’s camp. After further conversations with us, she gave me her copy, saying that I might need it for my research and that she could obtain another one for free from the monastery. She also told me of another Chan text that she had purchased and found important; she later sent me an e-mail saying that she had found a pdf copy of the text for free and attached it to the e-mail.

FIGURE 7.1 Participants in the 2012 Living Chan Summer Camp leave Bailin Monastery, Hebei province, at the camp’s conclusion

Photo by author

The group of participants in the Chan camp I met that summer formed part of a teaching-centered textual community: they shared knowledge of a collection of Chan scriptures, interpretations of Chan teachings by contemporary masters, and periodicals with essays on Chan. They had purchased most of the materials they read at either commercial or temple bookstores. They had obtained other materials online for free and (less commonly) in person at the monasteries. Likewise, the bookstore at Bailin Monastery itself, like the one at the Temple of Universal Rescue, to which Master Mingyi directed the new lay converts from his office, sold copies of Chan classics such as the Biographies of Eminent Monks (Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳) and the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch (Liuzu tan jing 六祖壇經) along with other Chan-themed literature that the campers sometimes bought. The temple also gave away some printed materials for free, such as copies of the proceedings of previous Chan camps and some Chan periodicals. These periodicals, which feature essays by well-known Chan monks and lay practitioners, circulate among a number of prominent Chan monasteries such as Bailin Monastery and Chaoyang Monastery 朝陽寺 outside Beijing, which I visited in 2010. As with the readers of periodicals such as Buddhist Studies Magazine (Foxue congbao 佛學叢報) and Awakening Society Collectanea, discussed by Scott, these Chan periodicals, along with the other Chan literature sold at temples or available online, function to connect geographically dispersed readers interested in Chan teachings within a textual community oriented around a shared set of discourses.21

In addition to taking part in summer camps like the one held at Bailin Monastery, participants in the Chan-centered community sometimes gather to discuss the content of the materials they have read and practice meditation together in student groups based at universities such as Peking University, in a small number of reviving Chan centers such as the Zhenji Chan Forest 真際禪林 in the city of Shijiazhuang, or as part of private meditation groups organized in rented apartments in urban areas. While sharing readings and practices that are centered at these prominent Chan temples, the Chan practitioners rarely exclusively consume the works of a particular master in the manner of the master-centered textual communities. However, they also have little exposure to a wide range of Buddhist-themed literature focusing on Pure Land practices, ritual instruction, and moralistic discourses about the decline of the world in the dharma-ending period (mofa shiqi 末法時期) that are commonly found at many non-Chan temple sites in China such as the outer courtyard of the Temple of Universal Rescue. Indeed, only Chan literature was available at both Chaoyang and Bailin Monasteries, which reflects, on the part of the authorities of those temples, a greater interest in and ability to regulate the content of the materials disseminated at their temples in comparison with the vast majority of Buddhist temples, where a wide range of Buddhist-themed media are brought in from the outside.

As my 2011, 2012, and 2013 fieldwork at Chan centers and Ji’s work reveal, the majority of participants in the Chan textual community are under the age of forty, located in urban areas, and have above-average incomes and well above-average levels of formal education.22 Chan summer camps such as that at Bailin, which restrict participation to adults under thirty and use level of formal education as a major criterion in screening potential applicants, contribute to these trends.23 The content of the materials this textual community reads and discusses is most often focused on spiritual self-improvement aimed at raising the quality of life. Its participants are less likely than those in the other two textual communities to see themselves as part of a collective religious movement. However, of the three, this teaching-centered textual community is the one most closely connected to monastics of government-approved Han Chinese Buddhist temples. As I consistently found in my research, monastics at both Bailin Monastery and the Temple of Universal Rescue took a strong interest in Chan Buddhism. Generally speaking, they were also eager to evangelize all types of Buddhism to the young, affluent, and well educated.

Master-Centered Communities

I originally met Wang Xuan in the outer courtyard of the Temple of Universal Rescue. Looking for guidance following her husband’s extramarital affairs, she had become interested in the teachings of one of the temple’s lay preachers, Teacher Zhang.24 Several years after she had decided to divorce her husband, however, Wang had grown uninterested in the teachings of both lay and monastic teachers at the Temple of Universal Rescue and felt drawn to the teachings of a Taiwan-based teacher, whom I will call Master Yang, a figure she had first heard speak at another Beijing-area temple. She felt that Yang spoke to her interests in how to live a morally upright life and transcend the pursuit of self-interest in a society where petty rivalries are commonplace. She was also interested in practicing meditation, which was part of her master’s practice method. She paid an annual fee of 260 yuan to belong to the master’s group. As a member, she met regularly with a small group of five practitioners in one another’s homes to discuss the master’s teachings. The master (or his surrogates) organized the small groups. After the end of one year, participants would be reassigned to a new group so that, as Wang put it, they would not always hear the same ideas about his teachings. He also provided them with a set curriculum of excerpts from sutras, his exegesis of those sutras, and specific questions for them to think through at the meetings. In 2012, one of Master Yang’s more affluent students purchased two stories of a residential space in the suburbs of Beijing for his students to gather for study sessions, meditation classes, and vegetarian cooking lessons. Wang explained to me that she had not participated in these sessions because they required session fees over and above the annual membership fee that she paid to belong to her master’s group. Wang also had not joined some of the other practitioners from her small group when they had traveled to other parts of China to listen to Master Yang deliver lectures. A single mother with a stable job that provided her with a steady but not lucrative income, Wang could afford to pay for the small group membership but nothing beyond that.

Wang Xuan’s experiences typify those of many of the participants in master-centered textual communities. These communities are focused on individual teachers who are usually monastics but sometimes laypersons. Participants in these communities usually only read teachings that are sanctioned by their masters, often that the masters themselves have written either in print form or online. These communities are thus discrete, closed textual communities.

The master-centered communities have two subtypes: The first and most common are “virtual” in the sense that, as with Wang’s group, the masters and disciples never or rarely meet in person. As the research of Jones and Smyer Yü demonstrates in detail, many of these masters reside in Tibet but maintain significant followings among Han Chinese throughout China.25 Others, like Wang’s master, are in Taiwan or overseas Chinese Buddhist communities. Many of their adherents initially encounter their masters’ teachings online.26 Some eventually travel great distances to meet these masters and learn from them in person.27 Many of the masters’ websites are organized to receive donations, and, as Smyer Yü’s ethnographic findings indicate, practitioners sometimes compete with one another to see who can give the most time and money to their masters.28 Generally speaking, the participants in master-centered textual communities are not connected to groups based in Han Chinese Buddhist temples, or, if like Wang’s group they initially meet at such temples, they soon convene elsewhere, often in private homes or specially designated, rented locations.29 As Smyer Yü’s research shows, the motivations of participants in these communities range from increasing personal wealth to finding spiritual resources in a materialistic world.30 Both Smyer Yü’s and Jones’s research findings stress that followers of Tibet-based virtual masters are sometimes highly affluent, especially in comparison with local Buddhists in the Tibetan areas where their masters are located.31 Wang’s fellow practitioners in her small study group of five included two schoolteachers and a businessperson who worked for a European-Chinese joint-venture company. All three of them were slightly more affluent than herself and could best be described as middle class, by which I mean that they all had at least a senior middle school (gaozhong 高中) education, lived by themselves or with their spouses and children only in individually owned or rented apartment homes with central heating and bathroom facilities, and possessed stable, white-collar jobs. Including Wang, they had better financial resources and higher levels of education than participants in the free-distribution community.

The second type of master-centered textual community involves primarily a personal, face-to-face relationship between master and disciples. While both types are usually connected to masters residing at physical temple sites, in the second type masters primarily or solely interact with their disciples at those sites rather than in a virtual setting. Examples of this type of community include adherents of a Buddha Recitation Hall (nian Fotang 念佛堂), which I will call Mingfa Buddha Hall, on the rural outskirts of a small city in northeastern China where I conducted fieldwork in the summer of 2011. The name “Buddha Hall” normally denotes a single building where sutra-recitation activities take place, usually with no monastics in residence. It is usually less prominent than a temple or monastery. However, Mingfa Buddha Hall is a six-building complex, planned to expand to an eventual eleven buildings, with several resident nuns. It is called a Buddha Hall rather than a temple mainly because its leader is a layperson and possibly because it makes the hall less regulated than a temple would be. The followers of the lay leader, whom I will call Teacher Wang, distribute only their master’s own lectures and video recordings at the Buddha Hall; no outside materials are allowed. Teacher Wang’s Beijing followers, who know about her from occasional lectures she makes in the capital, also distribute her materials as part of a free-distribution textual community at sites like the Temple of Universal Rescue. Once becoming committed to her teachings, however, many of Teacher Wang’s followers do not read or discuss materials other than those that she produces, and some stop going to religious sites other than her Buddha Hall.

Similarly, the lay preacher Teacher Zhang, who once counted Wang Xuan among his students, preached regularly to interested listeners at the Temple of Universal Rescue from the late 1990s for about a decade thereafter. Despite preaching in a setting surrounded by other, competing preachers and the availability of a wide variety of Buddhist texts and video recordings, Teacher Zhang’s followers read only one set of scriptures, the Threefold Lotus Sutra (Fahua sanjing 法华三經) that he had recommended, along with his own interpretive essays on those scriptures. Once his following became large enough, Teacher Zhang stopped preaching in the temple and began to gather followers at his home in the Beijing suburbs and at a nearby vegetarian restaurant. Like Teacher Wang, he also lectured away from Beijing at temples and, occasionally, in hotel ballrooms rented for his preaching.

In comparison with the virtual master–centered communities whose members often (but not always) rely heavily on online participation, members of these place-centered communities feature a mixed range of incomes with some, such as participants at Mingfa Buddha Hall, having very low incomes and levels of education. However, in the case of Teacher Zhang’s group, the shift from gatherings at a registered temple to a home-centered practice located far from any public transportation meant that, for the most part, only members of the group with their own cars could continue to belong. As a result, the socioeconomic status of the typical member rose after Teacher Zhang changed to that home-centered practice.

Free-Distribution Community

Jiang Xiuqin, a retired, widowed lay practitioner in her seventies, lives in a small apartment in the southwestern suburbs of Beijing. Despite having slightly below-average income for a Beijing resident and only a middle-school level of education, Jiang has directed many projects to reproduce and distribute free Buddhist-themed literature in the ten years that I have known her. Highly charismatic and very well read, Jiang often identifies Buddhist texts that she feels are underrepresented at the temples she frequents. She then calls both laypersons and monastics in the suburb where she lives, many of whom she herself originally converted to Buddhism, and asks if they have money and time to spare for a new distribution project. Though each of them typically donates only small amounts, she pools their funds to print copies (usually in the hundreds) of the texts she has selected and lists their names and contributions on the last page (unless they request otherwise). She then deputizes them to distribute the copies of these texts in area temples.

Sometimes Jiang also gives entire stacks of texts to other practitioners who have not participated in funding their printing but who are well known as lay preachers and text distributors. These practitioners have the know-how and stamina to preach on the content of the materials they receive and to discern from conversation which texts are best suited to their potential readers. Their support helps Jiang and her donors to spread the dharma in the most effective way possible. One such preacher-distributor is Luo Baoquan. As is the case with Jiang and most members of the free-distribution textual community, Luo’s socioeconomic status, which I will describe as working class, is lower than that of most of the participants in Wang Xuan’s study group and of many in the other master-centered communities. He has received only a junior middle school (chuzhong 初中) education and lives by himself in a one-room apartment with no bathroom facilities. Luo worked for many years in a local Beijing factory before he was laid off in the late 1990s. Now, surviving on a very low subsistence income but freed from any work responsibilities, Luo spends most of his days preaching on and distributing the Buddhist-themed literature he is given at temples like the Temple of Universal Rescue or the Temple of Divine Light (lingguang si 靈光寺) on the western outskirts of Beijing. Claiming that his work never tires him, Luo receives much praise for his erudition and the selfless generosity of his time, accolades that he, apparently, never met with in his workplace.

This third type of textual community has been the focus of much of my research.32 It is, at present, both larger in numbers of participants and more prevalent than the other two. It is created through the free writing, copying, and distribution of Buddhist-themed texts and multimedia materials. While some of the materials that this textual community consumes come directly from temple publishing houses such as that at Nanputuo Temple 南普陀寺 in Xiamen, Fujian, or overseas foundations like Jingkong’s, much of it is produced (or reproduced) through the efforts of individuals or small groups of practitioners. At some temple sites, such as the Temple of Universal Rescue or Boruo Temple 般若寺 in Changchun, Jilin province, practitioners discuss the content of these materials at the temples where they are distributed in impromptu, informal groups. Both of these temples contain large, open courtyard spaces for these groups to gather. Occasionally, lay preachers or wandering monastics (unaffiliated with the temples where they speak) will preach to interested audiences on their interpretations of these materials and do so sometimes, like Luo Baoquan, while handing them out. In some cases, preachers distribute materials that they themselves have written. Like the members of the World Buddhist Householder Grove described by Jessup, who went out every week to preach to the public, these preachers are motivated by the zeal of spreading the dharma in what they see as a corrupt age. More generally, practitioners in this textual community are motivated to participate in the writing, reproduction, and free distribution of these materials because, in addition to being highly meritorious, they believe that participation in these activities is an important part of conducting themselves as moral persons. This belief is reinforced by communal esteem for those, like Luo, who participate in the distribution of new texts. Deriving a sense of importance from their participation in the writing and distribution of Buddhist-themed materials is particularly important for this group since, unlike the elite householders discussed by Jessup, its members are likely to have relatively low status in society at large.

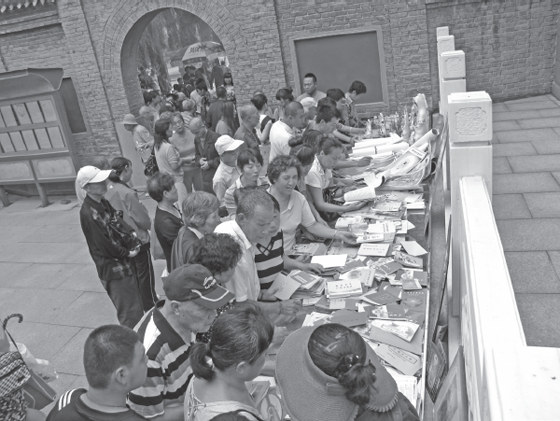

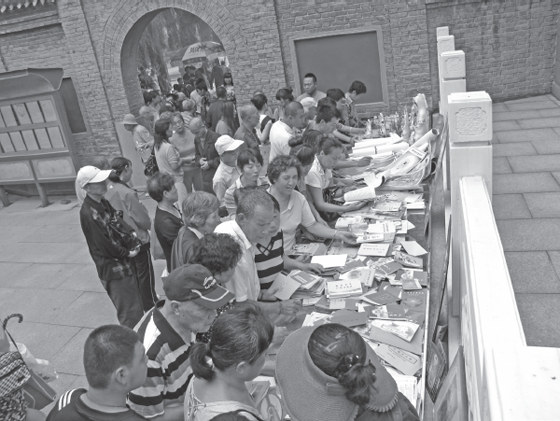

The content of the materials the practitioners in the free-distribution community hand out is varied: some of the materials are guidelines to correct ritual practice or temple etiquette; others contain the words to songs composed from morality books or Buddhist scriptures. Many are important scriptures like the Sutra of Infinite Life (Wu liang shou jing 無量壽經), often with annotated explanations of their meaning written in modern Chinese by contemporary teachers. In fact, contrary to Master Mingyi’s insistence that many of these freely distributed materials represented heterodox teachings, canonical Buddhist scriptures are just as widely available in this textual community as they are in the first two. Other types of materials include introductions to Buddhist teachings and hagiographies of well-known monastics or pious laypersons of the past as well as contemporary times (figure 7.2).

FIGURE 7.2 Participants in the free-distribution textual community browse through texts and images at Boruo Temple, Changchun

Photo by author

There is often a strongly moralistic quality to the materials this community distributes and the discussions created around them. Many of the materials emphasize the passing of human history into the dharma-ending period as part of a progressive moral decline. The texts provide evidence of this decline using contemporary examples that are selected to show a rise in skepticism, cynicism, selfishness, and materialism. One text, titled The Miserable World (Beican shijie 悲慘世界), laments that “present-day people love money as much as life.”33 Another book, called Walking Closer to Buddhism (Zoujin Fojiao 走进佛教), which was very popular at temples in the 1990s and following decade, criticizes present-day people for “sneering at traditional spiritual ideas” and being skeptical that any act could be performed out of genuine kindness.34 Some of the texts urge their readers to participate in a process of moral reform through the spread of Buddhist teachings by advocating the widespread adoption of a vegetarian diet and by showing others by one’s own example that they can live in a morally upright manner even in a decadent age. One book, Staying Forever in the True Teaching (Zheng fa yong zhu 正法永住), tells of a pious devotee to Amitābha who died in her home near Beijing in 1997. It praises her for transcending the small-minded attitude of her daughter-in-law and engaging in simple but worthy acts of kindness by helping a handicapped child, donating money to the building of a temple, and, toward the end of her life, spreading Buddhist teachings to fellow residents in a nursing home.

In spite of the diversity of messages in these texts and materials, I suggest it is more useful to consider this group as a single textual community. This is because, even though its participants present contradictory teachings that often spark disagreement and sometimes contentious debate, the widely varied materials this community shares are potentially accessible to all its members. Discussions of them are not limited to adherents of a particular master, let alone to those who have paid a membership fee. Even practitioners with limited economic resources can contribute to the corpus of materials available at temples so long as they can pay for some basic photocopying. Those that cannot even afford this can still, like Luo Baoquan, take on other roles in the process of circulating Buddhist-themed pamphlets by preaching on the content of materials that they receive for free. Moreover, even the relatively poor can travel throughout the country with surprising ease, purchasing cheap, hard-seat train tickets and using their conversion certificates (guiyi zheng 皈依證) to obtain free room and board at many temples. For this reason, unlike in earlier periods, even cheaply and unprofessionally produced materials often circulate over wide distances, enabling even practitioners with limited financial means to contribute to fostering religious discourses. Practitioners also sometimes add their own content to materials that were originally written and distributed through major publishing centers and then reproduce both the originals and additions just as the traditional distributors of morality texts in imperial and Republican-era China, as well as in contemporary Taiwan, added progressively to the content of original works over time.35 It was to this phenomenon that Master Mingyi referred when he declared that the materials the two newly converted practitioners had collected in the outer courtyard of the Temple of Universal Rescue were “pirated.”

In general, the nature of this textual community is rhizomatic in that there is no single voice that dominates it, with its most structured level of organization being cell-like groups independent of one another that are bound by the individual charisma of local leaders like Jiang Xiuqin.36 In this way, the free-distribution textual community stands in sharp contrast to the first two types of textual communities, which are strongly controlled by centralized authorities. Nevertheless, although active at different temples, its participants are linked as a fluid group that has at least potential access to the same discourses and whose members conceive of themselves as belonging to a single religious community, albeit an “imagined” one.37 The members of this community identify themselves as “[Buddhist] householders” (jushi 居士) or “disciples of the Buddha” (Fojiaotu 佛教徒) distinct from what they see as a predominantly nonbelieving public. This identity contrasts them with participants in the other two types of textual communities, who, while occasionally labeling themselves with the same terms, are more likely to self-identify as adherents of a particular master or as practitioners of a particular teaching such as Chan.

BUDDHIST TEXTUAL COMMUNITIES AND SYSTEMS OF EXCHANGE

Generally speaking, members in each of these three types of textual communities acquire their religious texts through different systems of exchange. Much of the reason why participants engage in different forms of exchange is rooted in their contrasting moral judgments on how religious goods should be given and received and what kinds of relationships, if any, these exchanges should form between the parties involved. These contrasting moral judgments, in turn, are strongly influenced by the different class backgrounds of their members.

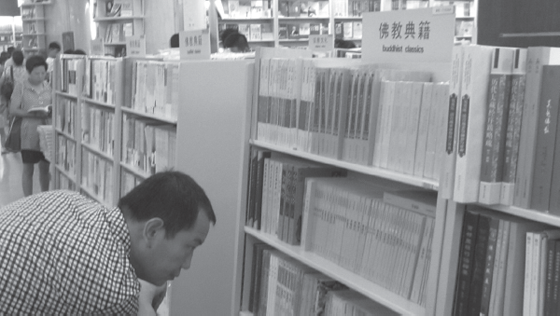

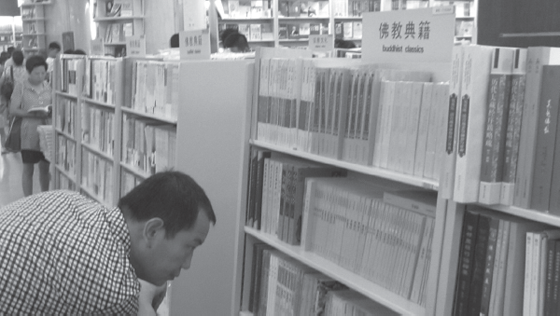

The Chan textual community acquires religious materials at least partly through commodity-based exchange. Most of the participants in this community gain some of their knowledge of Chan through the purchase of Chan-themed books either at temple or commercial bookstores (figure 7.3). In this way, the insights gained from these texts become commodities, but this process of commodification does not make them morally ambiguous. This is because most participants in Chan-based exchange generally accept that it is reasonable to pay for religious materials. For them, it stands to reason that if others have expended time and resources to create an insightful book or DVD, one who benefits from the insights of that book should pay for it just as one would pay for any other thing of value. In this respect, they are similar to practitioners who were willing to purchase Buddhist periodicals and Buddhist-themed books published by commercial presses during the Republican period explored by Scott in this volume. This is because both groups were socialized during periods of modern Chinese history when market-based systems were not regarded as necessarily immoral, albeit also not above moral reproach. The consumers of religious periodicals in the Republican period were raised during the time of a globalizing market economy; members of the present-day Chan-based textual community, most of whom are relatively young, were raised entirely in the post-Mao period, another time when commodity exchange has been considered normal. As a generally affluent group, they have also benefited from a commodity-based economy. For the generations between them, however, who were socialized during the Maoist era, the idea that something of spiritual value can be acquired through monetary purchase sometimes appears more dubious: this generation is well represented in the free-distribution community.

FIGURE 7.3 A gentleman browses the “Buddhist Classics” (Fojiao dianji 佛教典籍) section at the Beijing Books Building (Beijing tushu dalou 北京圖書大樓)

Photo by author

As with all forms of commodity-based exchange, the relationship between the consumers of the Chan-themed books and their purchasers is largely alienable, meaning the purchasing of the texts does not form a social relationship between maker and recipient.38 Similarly, while the participants in the Chan summer camp sometimes form close, personal relationships with their monk-teachers, it is less common for their practice to be directed solely by a close relationship with a single master, as is the case in the second type of textual community.

The master-centered textual communities are centered mostly not around commodity-based exchange but reciprocal gift exchange.39 In entering into a relationship with these masters, adherents are not obligated to buy anything; but they are expected to donate to the masters (and their spiritual projects) to cultivate the masters’ blessings. This pattern of giving is most obvious with the virtual masters, some of whom openly seek donations on their websites, but it also exists at physical sites like Mingfa Buddha Hall, where donation boxes are prominently displayed and volunteers line up outside the entrance to the Main Hall prior to the master’s weekly lecture to receive gifts and cash from her adherents (figure 7.4). In general, the closer one gets to a master, the more intense relationships of gift exchange become. One possible exception to this pattern is the required fee that followers of Master Yang must pay to be his students. Because this fee is fixed, it resembles a required transactional exchange that one would expect to find in a commodity-based exchange system. Nevertheless, Wang Xuan thought of this fee not as a required payment for spiritual services but as a donation to her master that all followers gave to show their commitment to supporting the spread of his teachings. In her case, the relationship between the master and his students was certainly not alienable.40

FIGURE 7.4 Lay volunteers at Mingfa Buddha Hall line up to collect donations from visitors

Photo by author

The third type of textual community, featuring the exchange of free religious media, is a system of religious gift exchange. Here I draw on the work of Jonathan Parry in his discussion of the giving of religious gifts (dāna) to Brahman priests in the Indian holy city of Benares.41 Parry argues that, through their gifts to the priests, donors seek to eliminate their sins. Unlike in reciprocal gift exchange, in religious gift exchange, no relationship is formed between the donor and recipient that compels the return of a gift in any form. Indeed, it is important that the recipient not reciprocate the donor because the donor’s aim is to receive a return gift in the form of merit to expiate his or her sin. Similarly, unlike donors in a reciprocal gift exchange system, who aim to form social relationships through exchange, those who donate Buddhist-themed materials to fuel this textual community do not seek to form social relationships with their recipients but rather to gain merit and perform morally correct social roles by freely donating their materials. However, whereas, according to Parry, the Brahmans in Benares absorbed the sins of their donors, laypersons such as Jiang Xiuqin and Luo Baoquan, who work to distribute Buddhist-themed materials in China, believe that the recipients of those materials will also gain merit since they can advance spiritually by reading or viewing the Buddhist-themed materials and being influenced to commit good deeds themselves. Indeed, it is the good deeds performed by the recipients of the media that make participating in their distribution a meritorious act for the donors. The act of donation provides equal amounts of merit for both parties. Most participants in this community believe that purchasing a religious text, as Master Mingyi encouraged the two new practitioners to do in my opening vignette, is an immoral act because, rather than benefiting its creator or distributor, it denies them the possibility of accumulating merit.

This last example begins to show how and why the three types of textual communities remain largely separate. We can understand why the model of textual community can be useful in understanding this separation when we consider that much of the contrasting moralities of exchange between these groups are reinforced through the texts that each group consumes and the discourses they create through their discussions of those texts. The materials that the third textual community shares stress the meritorious nature of their reproduction and why Buddhist-themed media should be freely distributed and not bought. The texts and videos that master-centered textual communities produce often stress the moral purity and spiritual power of their leaders, which attracts their would-be followers to provide gifts to enter into personal spiritual relationships with them.42 While teaching-centered textual communities do not advocate the development of commodity-based relationships, that fellow practitioners find it morally appropriate to purchase religious materials influences the moral habits of others in the same textual community. Belief in these distinct moralities of exchange then leads the participants in their textual communities to further acquire their religious materials only within those communities, which, in turn, fosters discourses that convince the participants in these textual communities of the correctness of their particular views. In this way, the relationship between the content of the texts and the separated and exclusive nature of the communities that surround these texts is cyclical.

However, that these materials contain different content does not explain how particular practitioners end up in different textual communities in the first place. To understand this, I argue, we must consider more closely the question of social class and how it connects to aspirations of personhood in post-Mao China.

SOCIAL CLASS AND TEXTUAL COMMUNITIES

To be sure, certain random factors sometimes direct a new practitioner into one textual community instead of another. The two new practitioners whom Master Mingyi advised to purchase their Buddhist texts at the temple’s bookstore could easily have not found him in the guest office that day. At any given dharma assembly, they might have run into a charismatic lay preacher encouraging them to read a free pamphlet he was distributing and so have been guided toward the orbit of the third type of textual community. The members of all three textual communities include representatives of both genders, all ages, and all income levels. Nevertheless, the research shows the most salient factor distinguishing participation in these different textual communities is social class.43 There are three elements with which this factor is closely interconnected: (1) access, (2) moralities of exchange, and (3) the relationship between the content of the materials each of the three communities consumes and their outlook on the moral state of post-Mao Chinese society.

1. Access. Both political and economic factors restrict the access of socially and economically marginalized practitioners to certain types of religious materials and the discourses surrounding them. As Smyer Yü notes, the Chinese state’s interest in opening up economic markets creates a space for religion.44 But since not everyone has equal access to the market, the possibility of opening markets does not lead to creating equal access to religious discourses for all. Generally speaking, the less economic power practitioners have, the more likely it is that political restrictions on religious practice will limit their ability to access the types of religious materials that are shared and discussed in the first two types of Buddhist textual communities. As I have shown, teaching-centered textual communities like those based on Chan teachings often generate some of their discourses through the shared reading of texts that must be purchased at bookstores. Practitioners of lesser economic means, such as those who participate in the free-distribution textual community at the Temple of Universal Rescue, often cannot afford to purchase those texts.

Similarly, one of the least-regulated areas of religious discourse in China today is online. In virtual space, both Chan groups and virtual masters are able to spread their teachings with minimal official interference. Participants in the free-distribution textual community often also lack both the funds and know-how to access these online materials. They are therefore often not exposed to the teachings centered on these texts. The master-based communities located in physical sites are also relatively inaccessible to less-affluent practitioners. Less well-off followers of Tibet-based masters cannot afford to visit their temples. Wang Xuan did not frequent the Beijing study center of her Taiwanese master because so many of the activities that the center organized demanded fees. Similarly, Teacher Zhang’s group became less accessible to less-affluent practitioners after he stopped attending the Temple of Universal Rescue and started to host his followers in his suburban apartment home.45 In sum, whereas religious spaces in China today are continuing to open up in both physical and online spaces away from authorized religious sites, access by less-affluent practitioners to these new religious spaces, and the textual communities whose discourses form within them, is limited. For this reason, such practitioners are drawn to the free-distribution community that most often convenes at state-approved religious sites.

2. Moralities of exchange. Many of my research interlocutors in the free-distribution community that convened in the outer courtyard of the Temple of Universal Rescue explained that an important factor that had attracted them to Buddhist teachings, with their emphasis on egalitarianism and the importance of universal compassion, was that they had come to feel alienated by the value placed on the acquisition of money in post-Mao China. For these practitioners, many of whom have limited economic means, it is not difficult to understand how an inability to purchase commodities or to spend cash in cultivating the relationships that many of their fellow Chinese find of value is humiliating. This perceived increase in the need for money to form important relationships was a significant problem for Luo Baoquan, who stated that he had been unable (and unwilling) to provide the gifts that some of his coworkers had given their boss to maintain good relations with him and ensure their continued employment. For older practitioners in particular, who were accustomed to the Maoist-era glorification of the worker and critique of capitalist-derived economic gain, the post-Maoist emphasis on the importance of money in acquiring status sometimes seemed a bewildering development. As I have shown, the requirement of money often excludes less-affluent practitioners from the first two types of textual communities. By contrast, the third type of textual community, which fosters a discourse on the importance of free gifts of Buddhist materials and the free sharing of knowledge and insight among laypersons, is most appealing to this less-prosperous group. Free access to religious materials not only enables less-affluent practitioners to collect religious materials and insights but also spreads the moral teaching that the payment of money for access to texts or teachings represents a moral corruption of true Buddhist principles. Indeed, participants in this textual community often emphasize that any form of discrimination is evidence of a discriminatory heart (fenbie xin 分别心) and a lack of understanding of the interconnected nature of all beings. When economically marginalized practitioners participate in a textual community where these egalitarian discourses are shared and reinforced, they work to reject the idea that they themselves are inadequate and instead learn to find fault with the values of the society around them. Ironically, the political marginalization that restricts their access to religious materials to approved religious sites also makes what is otherwise a looser discursive community centered on the sharing of a highly diverse range of texts and multimedia materials more cohesive by leading like-minded practitioners to gather in relatively discrete places. It is in this way that discussions and preaching emerge around these materials, which, in turn, generates their further composition and dissemination.

3. Moral outlook. In a related manner, practitioners are drawn into textual communities whose moral outlooks correspond to their socioeconomic status. For practitioners experiencing social and economic marginalization, materials emphasizing how the world is passing through a period of moral decline present an appealing message. According to Smyer Yü, a related moral discourse, that of the “spiritual crisis,” is discussed by some of the members of the Tibet-based master-centered communities.46 This discourse suggests that there is a lack of spirituality in Chinese society today because of the materialistic nature of ordinary social relations. But unlike those practitioners who criticize China’s moral decline, proponents of this spiritual crisis perspective perceive more a lack that needs fulfilling than a need for the replacement of an existing system of social relations wherein the flow of capital plays a significant role. This is shown through their readiness to use capital to form gift-based relationships with Tibetan masters. This moral outlook reflects the social position of many of the participants in these master-centered textual communities as deeply embedded in complex relationships of wealth accumulation. For the most part, these adherents seek an outlet away from that material-based social world rather than a complete retreat from it. In this way, they express an “ambivalent modernity” similar to that which Jessup describes in this volume in his analysis of affluent Buddhist householders in 1920s Shanghai who were attracted to Buddhist notions of frugality. However, this ambivalence toward an ethic of wealth accumulation and its effect on the spiritual health of post-Mao China is different from the discourses of moral decline espoused by many of the participants in the free-distribution textual community, who believe themselves marginalized both economically and spiritually by market reforms and whose critique of modernity is unequivocal rather than ambivalent.

The desire for temporary retreat by the more-affluent members of the master-centered communities is sometimes also shared by participants in the first textual community, particularly those who participate in the liminal experience of the Chan summer camps. Mostly, however, the text-driven discourses by members of the Chan textual community make few statements on collective morality, instead emphasizing spiritual self-improvement. This is in keeping with the status of its members as young, relatively affluent people who have, more than previous generations, grown up in an atomized world that stresses individual development over collective moral action.47

CONCLUSION: THE TEXTUAL COMMUNITY AND DIVIDED RELIGION IN POST-MAO CHINA

In examining Buddhist practice in contemporary China based on its division into textual communities, I have, by modifying a methodology developed by George Marcus,48 urged us to follow the book. I have sought to examine the social life of Buddhist-themed literature and multimedia materials in both print and electronic forms, including how and whether different materials connect with one another, and what public discourses are created through their shared reading and discussion in various forums, from the Internet to temple courtyards. I offer this model as an alternative to other frameworks that have been advanced in recent scholarship on religion in post-Mao China, such as a market-based framework49 or the examination of a religious “ecology”50 or “field.”51 These other approaches focus significantly on religion and particular religions like Buddhism as basic categories for social analysis. While their authors carefully present the significant diversities of Buddhist practice that exist in the localities they study, Buddhism is still taken as a starting point for analysis. In this way, these studies imply that, in spite of their differences, different practitioners of Buddhism in a particular region share some fundamental religious orientation. An analysis of religious groups as textual communities, however, suggests that this approach is misleading. As my findings show, different religious practitioners who identify themselves as members of the same religion in China today, even when that identification is a strong one, can have strikingly different life backgrounds, religious goals, and social orientations.

I suggest that a textual-community approach charts important divisions between Buddhist practitioners in China today by detailing the discursive connections and boundaries that inform their religious beliefs and practices. It illuminates why some Buddhist practitioners, such as those who practice at sites like the master-centered Mingfa Buddha Hall, feel a strong kinship with a particular Buddhist place and those who worship there, while others, such as practitioners in the free-distribution community at the Temple of Universal Rescue, share no common religious practice or identity with the majority of other practitioners, who may belong to different types of textual communities and practice different forms of religion, Buddhist and non-Buddhist alike. Conversely, the textual-community approach also reveals why practitioners at Bailin and Chaoyang Monasteries may share a strong kinship with one another while having virtually no association or interest with most other Buddhist temples. As the results of my findings show, a textual-community approach also tells much about how religious practice in post-Mao China is divided by social class; how a religion like Buddhism may seem to interest practitioners from highly diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and yet, in fact, be very much divided along class lines. This is in spite of the fact that members of those different classes may all identify themselves as Buddhist and espouse their different versions of Buddhism as the truth. Finally, I suggest that, as my comparisons with the studies of Scott and Jessup indicate, a textual-community approach need not be limited to the ethnographic study of contemporary religious practitioners but could also be fruitfully applied to a historical analysis of Buddhist-inspired practices at different periods of China’s history.

NOTES

I would like to thank Brooks Jessup, Jan Kiely, David Palmer, Rongdao Lai, Brian Nichols, and Philip Clart for their very helpful suggestions for the completion of this chapter. The field research on which it is based was funded by a Fulbright fellowship from the U.S. Department of State, a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Abroad fellowship, a research fellowship from the College of Arts and Sciences at Syracuse University, and an Emergences grant from the City of Paris distributed through the Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Much of the writing of the chapter was supported by a research fellowship from the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity.

1. Master Mingyi, like the other names used in this chapter, is a pseudonym.

2. Dan Smyer Yü, The Spread of Tibetan Buddhism in China: Charisma, Money, Enlightenment (London: Routledge, 2012).

3. Zhe Ji, “Non-institutional Religious Re-composition among the Chinese Youth,” Social Compass 53, no. 4 (2006): 535–49; Ji Zhe, “Religion, jeunesse et modernité: Le camp d’été, nouvelle pratique rituelle du bouddhisme chinois” [Religion, youth, and modernity: Summer camps and the new rituals of Chinese Buddhism] Social Compass 58, no. 4 (2011): 525–39.

4. Gareth Fisher, From Comrades to Bodhisattvas: Moral Dimensions of Lay Buddhist Practice in Contemporary China (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2014); Fisher, “Morality Books and the Re-growth of Lay Buddhism in China,” in Religion in Contemporary China: Revitalization and Innovation, ed. Adam Yuet Chau, 52–80 (London: Routledge, 2011); Fisher, “Religion as Repertoire: Resourcing the Past in a Beijing Buddhist Temple,” Modern China 38, no. 3 (2012): 346–76.

5. Ji Zhe, “Buddhism in the Reform Era: A Secularized Revival?,” in Chau, Religion in Contemporary China, 32–52; Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism; Robert P. Weller and Yanfei Sun, “The Dynamics of Religious Growth and Change in Contemporary China,” in China Today, China Tomorrow: Domestic Politics, Economy, and Society, ed. Joseph Fewsmith, 29–50 (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2010).

6. Gareth Fisher, “In the Footsteps of the Tourists: Buddhist Revival at Museum/Temple Sites in Beijing,” Social Compass 58, no. 4 (2011): 511–24; Fisher, “Religion as Repertoire”; Fisher, “The Spiritual Land Rush: Merit and Morality in New Chinese Buddhist Temple Construction,” Journal of Asian Studies 67, no. 1 (February 2008): 143–70; Alison Denton Jones, “A Modern Religion? The State, the People, and the Remaking of Buddhism in Urban China Today” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2010).

7. Fenggang Yang, “The Red, Black, and Gray Markets of Religion in China,” Sociological Quarterly 47, no. 1 (2006): 93–122.

8. Jones, “Modern Religion?”; Sun Yanfei, “The Chinese Buddhist Ecology in Post-Mao China: Contours, Types and Dynamics,” Social Compass 58, no. 4 (2011): 498–510. Sun engages Yang’s typology only in a footnote (509), where she asserts her difference from the market-based logic that Yang uses. Nevertheless, Sun’s typology is quite similar to Yang’s in that both categorize types of Buddhist groups in post-Mao China based on their degree of recognition and tolerance by the state.

9. Jones, “Modern Religion?,” 86–88.

10. Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983).

11. Anne M. Blackburn, Buddhist Learning and Textual Practice in Eighteenth-Century Lankan Monastic Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 10–11.

12. Joanne Rappaport, The Politics of Memory: Native Historical Interpretation in the Colombian Andes (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

13. As the work of Philip Clart shows, the creation and dissemination of texts has been a means also for modern spirit-writing groups, based in Taiwan, to create a unifying purpose for their group, disseminate the instructions of their gods, and as a primary source of income in the form of donations for printing that cover other overheads as well. Modern technologies of mass printing help to make the wide dissemination of the texts possible, while modern processes of urbanization make it necessary for groups that lack the traditional support of a rural community to seek alternative sources of funds in the form of the donations for printing. See Philip Clart, “Merit Beyond Measure: Notes on the Moral (and Real) Economy of Religious Publishing in Taiwan,” in The People and the Dao: New Studies in Chinese Religions in Honour of Daniel L. Overmyer, ed. Philip Clart and Paul Crowe, 127–42 (Sankt Augustin, Ger.: Institut Monumenta Serica, 2009).

14. For the sake of concision, I also confine my discussion to religious agents who identify themselves as lay Buddhist practitioners. I do not consider participants in religious activities at Buddhist temples who, by their own suggestion, merely use Buddhist temple spaces to engage in devotional activities to particular Buddhas and bodhisattvas but who have not made a holistic and exclusive commitment to Buddhism as a life-guiding teaching. The concept of a textual community would be much less useful in categorizing the religiosity of these devotees since they are much less likely than self-identified lay Buddhists to order their religious practices around the reading and discussion of texts.

15. Regarding late imperial China, see Evelyn S. Rawski, “Economic and Social Foundations of Late Imperial Culture,” in Popular Culture in Late Imperial China, ed. David Johnson, Andrew J. Nathan, and Evelyn S. Rawski, 3–33 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985). On innovations in Republican China, in addition to chapter 3 in this volume, see Jan Kiely, “Shanghai Public Moralist Nie Qijie and Morality Book Publication Projects in Republican China,” Twentieth-Century China 36, no. 1 (2011): 4–22; Jan Kiely, “Spreading the Dharma with the Mechanized Press: New Buddhist Print Cultures in the Modern Chinese Print Revolution, 1866–1949,” in From Woodblocks to the Internet: Chinese Publishing and Print Culture in Transition, circa 1800 to 2008, ed. Cynthia Brokaw and Christopher A. Reed, 185–210 (Leiden: Brill, 2010); Francesca Tarocco, The Cultural Practices of Modern Chinese Buddhism: Attuning the Dharma (London: Routledge, 2007).

16. Yoshiko Ashiwa and David L. Wank, “The Globalization of Chinese Buddhism: Clergy and Devotee Networks in the Twentieth Century,” International Journal of Asian Studies 2, no. 2 (2005): 217–37; Brian J. Nichols, “History, Material Culture, and Auspicious Events at the Purple Cloud: Buddhist Monasticism at Quanzhou Kaiyuan” (PhD diss., Rice University, 2011), 208.

17. Fisher, “Morality Books,” 57.

19. Jones, “Modern Religion?”; Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism.

20. The camp is designed to introduce Chan concepts and practice to interested adults under the age of thirty. Those selected for the camp attend for free thanks to the generosity of a wealthy lay donor. The campers participate in a rigorous daily schedule that includes sitting-meditation sessions, dharma talks, vegetarian meals, and temple maintenance duties (such as sweeping the grounds). Campers also participate in the sharing of personal experiences and the singing of Buddhist-themed songs, activities that are reminiscent of Christian camps in the West and Buddhist camps organized in the modern period by the Buddha-Light Association (Fo guang shan 佛光山) in Taiwan. The camp began in 1993 and has grown very popular, spawning many other versions throughout China. It was announced during the 2011 camp that only one in six applicants was accepted, with a slightly higher number of women than men.

21. Scott’s chapter shows how Buddhist periodicals of the early twentieth century, even those with brief print runs, played important roles in creating what I would term a textual community of Buddhist practitioners connected over a wide geographic area. In the post-Mao period, however, the Chan periodicals are the only ones I know of that function in a similar way. While many Buddhist periodicals are now produced and sold at both temple and commercial bookstores (the most well known being The Voice of Dharma [Fayin 法音]), I know of no practitioners in any of the textual communities I have studied, nor have I read about any in the work of other scholars, who read them. This is in spite of the fact that the offices of The Voice of Dharma are located inside the Temple of Universal Rescue, where I have conducted most of my ethnographic research. Practitioners in the free-distribution community do not read any publication that must be purchased; members of other textual communities are interested in reading mostly the publications of their respective groups. A publication sanctioned by the Chinese Buddhist Association (Zhongguo Fojiao xiehui 中國佛教協會) that claims to represent a single (effectively nonexistent) imagined community of all Chinese Buddhists does not appeal to them.

22. Ji, “Buddhism in the Reform Era”; Ji, “Religion, jeunesse et modernité.”

23. A senior monk at Bailin Monastery whom I interviewed in 2011 told me that the monastery uses the level of secular education as a major criterion in selecting applicants rather than knowledge of Buddhist teachings and practices. He explained that this was because it was an important goal of the monks who organize the camp to interest young intellectuals in Chan. The vast majority of campers I met were either college graduates or attending college, with many also working toward graduate degrees.

24. Fisher, “Religion as Repertoire,” 364–66.

25. Jones, “Modern Religion?”; Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism.

26. Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism, 77.

29. Sun, “Chinese Buddhist Ecology,” 505.

30. Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism, 16.

31. Jones, “Modern Religion?”; Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism.

32. Fisher, From Comrades to Bodhisattvas, 136–68; Fisher, “Morality Books.”

33. The Miserable World was a thin, paperback book written in simplified Chinese characters that was distributed at the Temple of Universal Rescue in the early years of the present century. Like much of the literature distributed in the courtyard, the versions I collected contained no information concerning authorship, place of publication, or publishing society. It is likely to have been written no earlier than the mid-twentieth century since, in one section, it champions Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) as a role model for living a vegetarian lifestyle.

34. Like The Miserable World, Walking Closer to Buddhism was distributed as a paperback book. Unlike The Miserable World, it was attributed to an author, Fo’en Jushi 佛恩居士 (literally, “Buddha-Kindness Householder[s]”), a name that could refer to either a single or multiple authors. The book was distributed in the mainland in simplified characters from a publishing house at Hongyuan Temple 弘願寺 in Anhui province. The temple and the publishing house are affiliated with the Pure Land Buddhism Foundation (Jingtuzong jijinhui 淨土宗基金会) located in Taipei.

35. Catherine Bell, “‘A Precious Raft to Save the World’: The Interaction of Scriptural Traditions and Printing in a Chinese Morality Book,” Late Imperial China 17, no. 1 (1996): 180; Chun-fang Yü, “A Sutra Promoting the White-Robed Guanyin as Giver of Sons,” in Religions of China in Practice, ed. Donald S. Lopez Jr., 97–105 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995); Kiely, “Shanghai Public Moralist.”

36. I take the concept of rhizomatic from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

37. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1991).

38. Chris A. Gregory, Gifts and Commodities (London: Academic Press, 1982), 100–101. Here and in my subsequent discussions of exchange, I am relying heavily on Gregory’s interpretations of Marcel Mauss’s theories on the features of gift exchange that make it different from commodity-based exchange (Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, trans. W. D. Halls [New York: Norton, 2000]). The distinctions that Gregory makes are the most useful for the purposes of my discussion here. I do concur, however, with scholars who have argued that Mauss’s category of gift exchange is wider than Gregory interprets it in that it also incorporates a category of what I later call religious gift exchange (see Jonathan Parry, “The Gift, the Indian Gift, and the ‘Indian Gift,’” Man 21, no. 3 [1986]: 453–73; James Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 6, no. 4 [2000]: 617–34).

39. I take this to mean an exchange between two parties that is reciprocal, where items in the exchange are inalienable from the donor, and where the primary aim of the exchange is the creation of a meaningful personal tie between the two parties rather than, as would be the case in commodity-based exchange, the acquisition of particular goods or services. Again, I am relying on Gregory’s interpretation of Mauss’s distinction between gift and commodity exchange. I have added the term “reciprocal” to distinguish between the type of gift exchange I am describing in this section and religious gift exchange.

40. Smyer Yü (Spread of Tibetan Buddhism, 114–16) argues that the large wealth that Han Chinese followers of the Tibet-based masters provide represents the incursion of a capitalist commodity-based system into a traditional Tibetan system founded on relationships between Tibetan masters and local laypersons maintained through the giving of gifts. I suggest, however, that the contrast between Tibetan and Han Chinese forms of giving is better represented as a disjuncture between two rival forms of gift exchange: one a traditional Tibetan system of gift exchange centered on relationships of patronage between laypersons and monastics, and the other, represented by the Han Chinese followers, a system of exchange centered on the giving of gifts and favors to form relationships (guanxi 關係) that has become culturally dominant among Han Chinese living in the post-Mao period. This guanxi-based system is fueled by the increasing availability of capital in a nation experiencing significant economic growth; but this is not the same thing as representing a commoditization of the Chinese economy or Chinese society. In the same way, the Han Chinese followers of Tibetan masters are not trying to “buy” access to the Tibetan masters so much as they are trying to enter into inalienable relationships with them by giving gifts of money. They then hope that these strong personal relationships will provide them with access to their masters’ spiritual insights and powers.

42. Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism, 77–80.

43. For detailed discussions of class difference in post-Mao urban China, see Deborah Davis and Feng Wang, eds., Creating Wealth and Poverty in Postsocialist China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009); Amy Hanser, Service Encounters: Class, Gender, and the Market for Social Distinction in Urban China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008); William Hurst, The Chinese Worker After Socialism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

44. Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism, 101.

45. A possible exception to this pattern is Mingfa Buddha Hall, which had many less-affluent practitioners. Even there, however, there was a strong culture of giving and the expectation that, even when having little, one should donate to the master: those practitioners who could not afford to do so often lent their labor to build up the infrastructure of the hall.

46. Smyer Yü, Spread of Tibetan Buddhism, 107–10.

47. Vanessa Fong, Only Hope: Coming of Age Under China’s One-Child Policy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004); Yunxiang Yan, The Individualization of Chinese Society (London: Berg, 2010).

48. George E. Marcus, “Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-sited Ethnography,” in Ethnography Through Thick and Thin, ed. George E. Marcus, 79–104 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

49. Yang, “Red, Black, and Gray Markets”; Fenggang Yang, Religion in China: Survival and Revival Under Communist Rule (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

50. Sun, “Chinese Buddhist Ecology.”

51. Jones, “Modern Religion?”