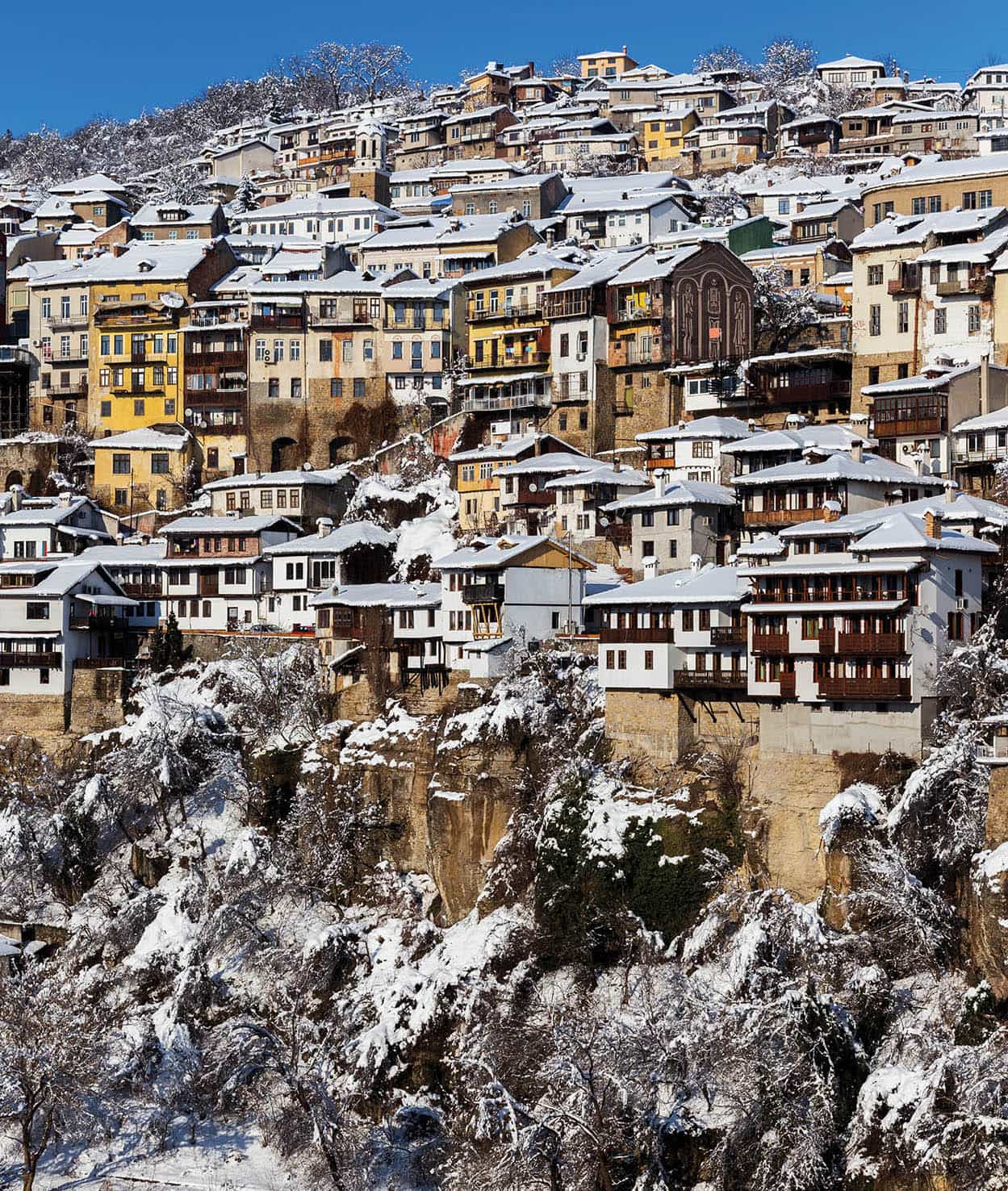

Stefan Stambolov Street in Veliko Tarnovo

Getty Images

The best of Bulgaria comprises the capital, Sofia, and the Rila and Pirin mountains to the south; the historically significant Balkan range that sweeps through the centre of the country; and the Black Sea coast. Using the country’s three largest cities of Sofia, Plovdiv and Varna, as well as the smaller but regionally important Veliko Tarnovo, as bases – all with excellent hotel, restaurants and services – most of the country can be explored quite easily. And wherever you go, you are seldom far from a sight of historical or natural significance.

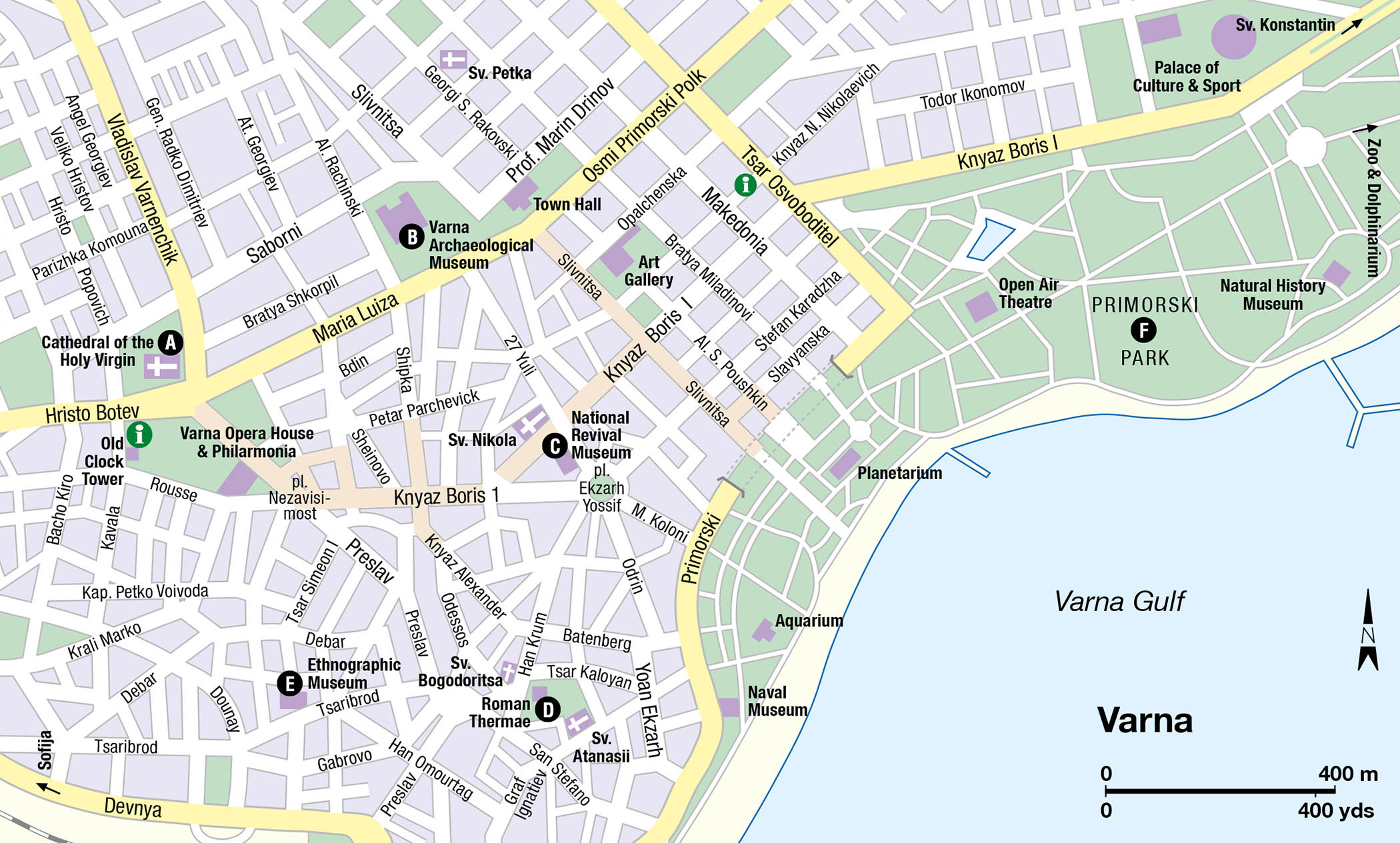

Street names

Some useful terms to know when navigating the streets of Bulgaria’s cities, towns and villages are: bulevard (bul) – boulevard or avenue; ploshtad (pl) – square; and ulitsa (ul) – street. You’ll find that churches are usually named after a saint: sveti/sveta (sv).

Sofia

Overlooked from the south by the 2,290m (7,515ft) high Cerni Vrah, Sofia 1 [map] nestles snugly at an altitude of just under 600m (1,970ft). Home to just under one and a half million people, almost a fifth of the country’s total population, it has a history going back to the Roman settlement of Serdica, but almost all of its important buildings and monuments, like the modern state they help define, are less than 150 years old. Visitors arriving either by road from the airport or by train will be disappointed at their first impressions of the Bulgarian capital. Sofia requires a little perseverance from the visitor, for once through the encirclement of monolithic, dilapidated Soviet-era apartment blocks, the city centre is a gem.

Most sights are contained within the area bordered by boulevards Evlogi Georgiev, Hristo Botev, Slivnitsa and Vasil Levski. This area can be divided into three different (though not distinct) districts: Imperial Sofia, centred on the Nevski Cathedral, St Sofia and the Yellow Brick Road, Byzantine and Ottoman Sofia, around Sveta Nedelya, the Sheraton Hotel and Banya Bashi Mosque, and Modern Sofia, the city’s commercial hub along boulevards Vitosha and Graf Ignatiev.

The magnificently ugly NDK

iStock

Stray dogs

Bulgaria has a large stray dog population. Though the dogs rarely bite, they often bark at passers by, attacking occasionally. It is to be hoped that the authorities will soon rid the country of this problem (in some cities, including Sofia and Plovdiv, they by and large have). Should you be bitten, go to the nearest hospital for a series of rabies injections immediately.

Modern Sofia

Modern central Sofia, which stretches from the inner ring road to ploshtad Sveta Nedelya (St Nedelya Square), is by no means an architectural wonder. The most modern building is the magnificently ugly National Palace of Culture, known by locals and marked on most maps as the NDK. Built in 1981 as a multi-purpose cultural venue, it stands guard at the southern entrance to the city centre – it cannot be missed – without a single redeeming feature.

The area in front of the NDK is known as pl Bulgaria, or Yuzhen Park. It has some decent summer terraces, and often plays host to outdoor events, including rock and pop concerts. Though the fountains are attractive (when they are working), the square is dominated by the enormous, eye-catching (for all the wrong reasons) 1,300 Years of Bulgaria Monument. This folly was conceived in the early 1980s when the Bulgarian Communist Party was reinventing itself as a more nationalist movement. Links with Bulgaria’s glorious past, however tenuous, were encouraged. The monument commemorates the anniversary of the founding of the ‘first unitary Bulgarian state’ in 681, after Khan Asparuh defeated a Byzantine army at the Danube Delta.

Straight ahead you will find Vitosha Boulevard, Sofia’s main shopping street. Vitosha has long been a centre of commerce, and the street is pleasant enough on the eye, with most of the post-World War II buildings being no taller than four or five storeys. Shops, cafés, street traders and surprisingly wide pavements make a stroll along Vitosha a pleasant experience.

Sofia’s synagogue

iStock

At the northern end of Vitosha is the city’s only pedestrian street, Pirotska. Lined with cafés and shops, it is worth exploring for bargains. Running parallel to Pirotska is Ekzarh Yosif, where you will find Sofia’s synagogue A [map], the largest in the Balkans. Built between 1903–09 the synagogue (Mon–Fri 9am–4pm, Sat 10am–2pm except Passover) can accommodate 1,200 worshippers. Today, however, most services are held in the smaller rooms at the front, as Sofia’s Jewish population has dwindled to below 5,000 from around 50,000 before World War II.

At the far end of Pirotska is the city’s largest market, Zhenski Pazar, or women’s market (daily sunrise–sunset). Selling mainly produce, the market also has clothes, craft and bric-a-brac stalls selling good souvenirs, though you may have to hunt through a large amount of tat to find something worthwhile. The real charm of the market is just watching the locals shop.

A better place to look for bargains is Graf Ignatiev Boulevard, which runs at a 45-degree angle from Vitosha to the river. Close to the southern end of Graf Ignatiev is the decrepit-looking Sv Sedmotchislenitsi Church (7am–7pm, services daily 8am and 5pm), dedicated to Sts Cyril and Methodius, the Bulgarian brothers who created the Cyrillic alphabet (click here or click here). Although less than impressive from the outside, the church’s interior is exceptional, with well-preserved frescoes.

Byzantine and Ottoman Sofia

At its northern end, Vitosha Boulevard leads into pl Sv Nedelya B [map], the traditional heart of the city, dominated today by the Sofia Hotel Balkan, though there is much more to its charms than that splendid building alone.

The centrepiece of the square is the church that shares its name, Sv Nedelya (7am–7pm, services daily 8.30am and 5.30pm), which stands on what was the very centre of ancient Serdica. This 19th-century building is the latest in a long line of churches on the site. The outside is not impressive, but the inquisitive visitor is rewarded on entering by some of the finest icons and most colourful murals in the country. On leaving, note the plaque that commemorates (in Bulgarian) the fact that assassins attempted to kill Tsar Boris III here by planting a bomb in the church during a service in 1925.

The Grand Hotel Balkan, behind and to the right of Sv Nedelya, is part of a much larger building; the rear is occupied by the Presidency (entry only by appointment), the offices of Bulgaria’s president. The two guards who ceremoniously stand erect at the modern glass entrance are an anachronism in their ancien regime costumes, but a picture-postcard sight nonetheless.

Directly next to the hotel is TZUM, once the state-run department store selling little of any interest to anyone, today a modern, multi-level shopping centre playing host to a wealth of big brand name stores. Across the road is the ghastly Statue of Sofia, put up in haste on a whim of the mayor in 2001. To the right of TZUM in the centre of a small park is Sofia’s only surviving, working mosque, the Banya Bashi. On the other side of the same square, behind graffiti-strewn hoardings, are the majestic Municipal Baths, first built in 1913 in a style which pays homage to Bulgaria’s Byzantine connections, and which today host the Sofia History Museum (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm). The museum tells the story of the city from ancient times to the 1940s by way of eight excellent exhibitions.

The Halite food market

iStock

Directly opposite the baths is the Halite (daily 6am–8pm), the century-old central food market, which sells all kinds of local food, from meat and fish to cheese and sweets. The lower level has been expertly adapted to incorporate Serdica ruins, where local people make use of a number of food outlets at lunchtime.

Past the entrance to the Presidency is a large courtyard which hides the city’s oldest building, the Sv Georgi Rotunda (Mon–Sun 8am–5pm; donations expected). Built for an unknown purpose in the 4th century, it became a church in the 6th century and is today surrounded by part of Sofia’s visible Roman ruins. Much of what you see on the outside of the rotunda, however, is relatively new, and major restoration work was not always carried out with as much care as it could have been. The Roman ruins look similarly out of context surrounded by red brick. The real glory of the rotunda lies in its interior: three layers of original frescoes can still be seen, the oldest dating back to the 10th century.

Opposite the Presidency is the Archaeological Museum C [map] (Apr–Oct daily 10am–6pm, Nov–Mar Tue–Sun 10am–5.30pm), which is housed in the former Grand Mosque, built in 1494. Many of Bulgaria’s finest treasures from Thracian, Roman and Byzantine times (including two enormous Roman sarcophagi) are displayed here. The golden burial masks and medieval icons are particularly worth seeking out. The monumental building on the other side of the road is the former Communist Party Central Committee Building, from where Bulgaria was run for the best part of 50 years. The building was topped by an enormous red star during the Communist era, and a rather limp flag today tries hard to fill the breach.

Moving further along, the Largo, or Yellow Brick Road (because of the now rather faded yellow cobbles), occupied mainly by foreign embassies and government offices, leads to the Tsar’s Former Palace, today the Ethnographical Museum and National Art Gallery, on the right, opposite the Alexander Battenberg Square. Until 1999, the centrepiece of the square was the stark mausoleum of Georgi Dimitrov, the first Communist leader of Bulgaria who died in 1949. Dimitrov’s remains were removed in 1990, and the building itself demolished nine years later. The southern end of the square has a host of good cafés and restaurants, almost all of which have tables on terraces during the summer, while the outdoor café in front of Bulgaria’s National Theatre on the eastern side is one of the best, trendiest and most expensive places to drink coffee in the city.

Walking back to the Tsar’s Former Palace at the northern end of the square, the two museums now housed inside are worth visiting, depending on what’s on. The National Art Gallery (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm) has no permanent exhibition, and changing exhibitions highlight the works of the country’s leading artists, for which guided tours are available in English, with notice, during the week.

Far more interesting is the Ethnographical Museum (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), where the collection includes a good selection of Bulgarian traditional clothes and costumes, arts, crafts and musical instruments. Children in particular will love it. The small gift shop sells good-value souvenirs.

Sv Nikolai Church

iStock

Turning left out of the palace, the next building on the left is Sv Nikolai (Russian) Church D [map]. Built quickly over the winter of 1912–13 on the whim of a Russian diplomat, it is the loveliest church in the city, as its relatively small size prevents it from being overwhelmed by the ostentation that smothers many other churches. The onion domes that give away its heritage were repainted in gold leaf donated by Mother Russia. The church’s most interesting facet is the crypt (daily 7.30am–6pm), which houses the body of Bishop Serafin, a popular local religious leader who died in 1950, and who was too revered by the local population to be buried in the anonymous grave the recently installed Communist regime wanted.

Imperial Sofia

The Third Kingdom of Bulgaria did not last long. Yet from independence from Turkey in 1878 to the exile of King Simeon II in 1946, regal Bulgaria embarked on a campaign of building and modernising its capital that was at once breathtaking in its speed and impressive in its lasting grandeur.

Of all Sofia’s wonders the Alexander Nevski Cathedral E [map] (daily 7am–7pm, services daily 8am and 5pm, Sun Mass 9.30am), which stands in a square of the same name, remains the most enduring. Its immaculate golden domes, restored to their original splendour with gold leaf donated by the Russian Orthodox Church, still dominate the city’s skyline and glitter in any amount of sunlight; even a dull day can be brightened by their sparkle. Built between 1882 and 1912 in the elaborate neo-Byzantine style of the time, the cathedral is named after St Alexander Nevski, the Russian tsar who led his country to victory over Sweden in 1240. He was the patron saint of Tsar Alexander II, the Russian monarch at the time of the cathedral’s construction.

The Alexander Nevski Crypt F [map] (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), entered down the stairs on the left-hand side of the church’s main doors, is the best museum in Sofia and possibly the top attraction in the country. The collection of Old Bulgarian art on show is outstanding, and there are few museums offering a better selection of iconography anywhere in the world. Highlights include the altar doors from the Pogonovo Monastery, dating from 1620, as well as the doors from the Orlitso Nunnery at the Rila Monastery, paintings executed in 1719. All exhibits have captions in Bulgarian and English, and there is an excellent shop selling fine replicas and other Bulgarian souvenirs.

The city’s oldest church and namesake, Sv Sofia

iStock

In front of the cathedral is Sofia’s oldest church, the Sv Sofia (daily 9am–6pm), which gave the capital its name. Built in the 5th century on the highest point in the city, the church has been destroyed and rebuilt a number of times. The Turks used it as a mosque from the 16th century onwards. The present building dates from the late 19th century, built to replace the previous structure (which had a minaret), which was destroyed in Sofia’s last great earthquake in 1858.

The area between Sv Sofia and the cathedral is dominated by a small but infinitely interesting flea market, the perfect place to buy Todor Zhivkov portraits, Orders of Lenin medals and Hermann Goering fountain pens.

Opposite the cathedral is the Bulgarian Parliament building, while behind is the National Library, with Sofia University next to that on the other side of ul 19 fevruari. The strange statue at the northern end is in fact the much heralded Vasil Levski Monument. This peculiar erection marks the spot where Levski was hanged in 1873 by the Turks for allegedly planning an anti-Ottoman revolt.

Vasil Levski

On his execution in 1873, the Bulgarian revolutionary Vasil Levski became a martyr for the Bulgarian independence movement; today he is remembered as the country’s greatest revolutionary and his name adorns streets, stadiums, monuments and sports teams. Born in 1837, Levski became a professional revolutionary in his early 20s, and quickly became the symbolic leader of the Bulgarian nationalists, travelling in secret around the country to raise funds and find recruits. He was betrayed by Dimitar Obshti, who, when arrested in December 1872, told the Turks all he knew about the Bulgarian revolutionary movement. Levski was arrested and hanged in Sofia the following February; the spot is marked by the Levski Monument.

Sofia’s Outskirts

Sofia offers a number of delights away from the bustle of the centre, in the hills that lead up towards Vitosha National Park. The most important, and an essential stop on a trip to Bulgaria, is Boyana Church G [map] (Tue–Sun 9.30am–5.30pm; additional charge for tours in English and other languages) in the suburb of Boyana, a 20-minute taxi ride (around 12 leva) from the city centre. Listed by Unesco as a World Heritage Cultural Site, Boyana was built over two centuries from around 1050 to 1259, when the frescoes for which it is famed were executed. More than 250 people are depicted on the walls in a style that anticipates the Renaissance. The painter’s identity is unknown.

Armed with a good map you can make your way on foot in about 20 minutes from Boyana to the splendid National History Museum H [map] (Apr–Oct daily 9.30am–6pm, Nov–Mar 9am–5.30pm). Walk back from Boyana to the Daskal Sv Popandreev and follow bul Pushkin to where it meets ul Radev. The huge building on the right-hand side, well hidden behind a tall fence and enormous garden complex, is the Boyana residence, former home of the Communist Party boss Todor Zhivkov. The entrance to the museum, housed in a smaller building, is easily found by taking ul Gabrovnitsa, the first turning on the right as you pass the residence. If you don’t fancy the downhill walk, you won’t have to wait long for a taxi at Boyana, as visitors come and go all the time. You can also take the infrequent bus No. 63 from church to museum.

Thracian amphora at the National History Museum

Balkanpix.com/REX/Shutterstock

Todor Zhivkov

Bulgaria’s former Stalinist leader Todor Zhivkov cut a sorry figure in the 1990s, one far removed from the hated dictator who had terrorised a country for nearly 40 years. Zhivkov assumed leadership of the Bulgarian Communist Party in 1954, having outmanoeuvred his rivals following the death of Georgi Dimitrov in 1949. Zhivkov’s leadership was characterised by slavish loyalty to the Soviet Union, often at the expense of Bulgaria’s own interests.

Of all Zhivkov’s disastrous policies, which contributed to the utter bankruptcy of the economy, it was his treatment of Bulgaria’s Turkish population that secured him a place in the pantheon of the most despised Communist leaders. During the 1970s and 1980s Turks were persecuted mercilessly by Zhivkov’s regime until, in the summer of 1989, hundreds of thousands voted with their feet and headed for Turkey.

Arrested in November 1989 immediately after the regime changed hands, a mockery of a trial in 1990 found Zhivkov guilty of embezzlement and, though he was sentenced to life imprisonment, he spent the years until his death in 1998 under comfortable house arrest.

The National History Museum was relocated to its current Boyana setting in 2000. The move caused a scandal at the time, but the judgement of the city’s authorities has proved to be sound. The museum’s former home in the Palace of Justice in the centre of town was cramped and dark, whereas the present location allows the stunning collection of well over 22,000 exhibits to breathe. The museum is well laid out, and many of the best exhibits have English captions, though maps showing the Bulgarian Empire’s rise and fall are captioned in Bulgarian only. Familiarity with the Cyrillic alphabet (for more information, click here) would help here. Highlights include jewellery dating from 500 BC, the Pangyurishte treasure – 6kg (13lb) of gold commissioned by Thracian King Seuthes III – and much early Christian iconography. Children will enjoy the small play area in the rear of the museum, as well as the MIG fighter jets that are on display at the front.

Getting back to the centre of Sofia from the museum is easy: take trolley bus No. 2 from its terminus at the car dealer-ship directly opposite the museum to pl Makedonia.

Vitosha

The presence of the Vitosha Mountains just 10km (6 miles) from the centre of the city makes Sofia one of the most fortunate capitals in Europe. Access to Vitosha National Park from Sofia is easy: a taxi will cost no more than 10 leva to either the Dragalevtsi chair lift or Simeonovo gondola stations. Public transport to both is surprisingly unreliable outside the ski season (December to April).

Dragalevtsi a charming village offering a number of good places to stay and eat, is most famous for its monastery I [map], built in the mid-14th century. Though little of the monastery remains, the original 14th-century church and a few of the original cloisters – one of which sheltered revolutionary Vasil Levski from the Ottoman secret police in the 1860s – are in good condition, while the gladed setting alone is well worth the 15-minute walk up from the chairlift station. Simeonovo is a less interesting village, notable only for its access to Vitosha via its gondola, which is quicker than the Dragalevtsi chairlift, and during winter queues here are shorter.

Both the Dragalevtsi and Simeonovo lifts terminate at Aleko, the heart of Vitosha, at an altitude of 2,000m (6,560ft). From here a small number of chair and drag lifts radiate out to form a half-decent ski area in winter, though advanced skiers will be bored in a day or two as there are few difficult pistes around Aleko. The hotels up here all rent out ski equipment and can arrange for instruction. Aleko is swamped by Sofians every winter weekend, so it’s best to ski from Monday to Friday. The spring, summer and autumn are different stories entirely. The chairlifts usually operate only at weekends, but with locals usually preferring to walk the well-marked paths, you should never have to wait too long. The tallest peak in the range, Cerni Vrah at 2,290m (7,515ft), can be scaled by the fit in an hour’s hike from Aleko.

Day trips from Sofia

There are several worthwhile attractions in the vicinity of Sofia, but they are scattered to all points of the compass at varying distances from the city. The best solution if you wish to explore the area is to stay in the capital and hire a car, perhaps combining two or three destinations in a day if they are in the same general direction.

The striking Iskar Gorge

Getty Images

North of Sofia

There are several routes leading north from the capital. The most striking follows the 156km (97-mile) Iskar Gorge 2 [map]. Narrow and bumpy in places, it is rarely busy, and there are plenty of places to pull over along the way to admire the views. The most stunning parts of the gorge are between Novi Iskar and Lyutibrod, an area that was almost completely cut off from the rest of Bulgaria until the railway was built in the 1890s. The road came much later. Even today the only settlement of any size is Svoge, situated in one of the remotest and most spectacular parts of the gorge, where the Iskar and Iskrets rivers meet.

Cherepish Monastery

Alamy

The mountains north of Sofia have the greatest concentration of monasteries in the country. The most accessible is the Cherepish Monastery 3 [map], which is located close to where the Iskar Gorge peters out around Lyutibrad. Legend has it that in the 14th century Tsar Ivan Shishman fought and defeated an unnamed enemy here – probably the Turks – before beheading the dead and burying their skulls on the site where the monastery was built shortly afterwards. Locals insist that the very name of the monastery (cherep means ‘scalp’ in Bulgarian) attests to the truth of the myth. Today, the monastery is known more for its 15th-century gospel bound with gold covers and the Festival of the Assumption on 15 August, when it is swamped by day-trippers from Sofia.

More off the beaten track is the Sedemte Prestola Monastery, which lies nestled in wooded hills about 15km (9 miles) along the side valley of the Gabrovnitsa stream (turn off the main gorge route at Eliseina). Built in the 11th century, destroyed and rebuilt in the 18th, the monastery was always a popular refuge for outlaws, bandits and nationalists.

Hristo Botev

The poet Hristo Botev, the most romantic of all Bulgaria’s revolutionaries, was born in Kalofer, near Kazanlak, in 1848 – Europe’s year of revolutions. Exiled to Romania in 1867, after provoking the wrath of the Turkish authorities with his nationalist public speaking, Botev threw himself into literary pursuits, acting as an editor of a number of émigré newspapers, as well as writing increasingly nationalistic poetry. He became de facto leader of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Committee in 1873 after Vasil Levski’s execution, and presided from afar over the disastrous April Revolt of 1876. After the revolt had been crushed, Botev, with 200 supporters, attempted to galvanise Bulgaria’s nationalists in support of a new revolt, only to be killed on 20 May by a Turkish patrol while making his way to the town of Vratsa. His 1875 volume, Songs and Poems, remains the finest work of Bulgarian national poetry.

Further north is the small town of Vratsa, gateway to Vratsa Gorge 4 [map], which begins just 2km (1.2 miles) beyond the city centre and is an excellent day-trip on its own. There are two good museums to visit, the Ethnographical Museum and the History Museum (both Tue–Fri 9am–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 9am–noon and 2–5pm). The Ethnographical Museum has a number of Revival-period houses, and a large warehouse displaying 19th-century Orazov horse-drawn carriages. The History Museum’s highlight is the peerless Rogozen treasure, a stash of silver found in 1985 in nearby Rogozen village, dating from the 5th century BC.

The only other town of note further north is Berkovitsa, once famous for its pottery but now not really worth a visit, though a small Ethnographic Museum does try to keep the city’s heritage alive.

East of Sofia

Known to all Bulgarian schoolchildren as the cradle of the modern Bulgarian state, Koprovshtitsa, 75km (47 miles) east of Sofia, was the site of the ill-fated April Rising of 1876, when a rudimentary force of Bulgarian nationalists sought to spark a nationwide revolt that would finally free Bulgaria from the Turks. Though the rising was ruthlessly suppressed, it did at least raise international awareness of the brutality of the Turkish regime in Bulgaria, and the town has remained a symbol of Bulgarian nationalism and culture. For such reasons it is the host of a national music festival (held every five years, it is next due in August 2020). At an altitude of 1,060m (3,480ft), the town is also a popular mountain resort.

The primary attractions of Koprovshtitsa, however, are its National Revival-period houses, six of which are open to the public as museums (Apr–Oct Tue–Sun 9.30am–5.30pm, Nov–Mar Tue–Sun 9am–5pm). A ticket can be bought which is valid for entry to all six houses (with the exception of the Oslekov House). Guided tours of the houses in English are also available, although you should phone ahead to check.

Kukeri dancer, Pernik

Shutterstock

West of Sofia

Pernik 5 [map], 25km (15 miles) west of Sofia, is one of the best places in Bulgaria to witness the bizarre Kukeri festivals (for more information, click here) for which the country is famed. Over the last weekend of January thousands of men dress in costumes usually made of dead animals – including the heads – designed to evoke fear and scare off evil spirits. Dressed like this, they then spend long hours in a trance-like state dancing and chanting throughout the town. The origins of Kukeri are vague, but the practice is thought to have derived from the religions of the ancient Thracians.

Beyond Pernik, following the same road to Kyustendil, Zemen Monastery 6 [map] has Bulgaria’s best collection of 14th-century frescoes, restored to greatness in the 1970s. The exterior of the monastery is not as lavish as others in Bulgaria and its position, on a hill hidden from the town of Zemen, is one of the most secluded. The meandering Struma river flows through the scenic 25km (15-mile) -long Zemen Gorge; however, the road skirts around the gorge so the only access is on foot (though the railway line does pass through it). The 70m (240ft) -high Skakavitza waterfall near the village of Kamenishka Skakavitza is just one of the highlights.

The Pirin and Rila Mountains

Directly south of Sofia is the small Rila mountain range, known primarily for the Rila Monastery, Bulgaria’s most famous attraction. Further south, stretching towards Greece, are the Pirin Mountains. Both ranges offer decent skiing (at Borovets in the Rila, at Bansko in the Pirin) and serve as good bases for hiking and walking, especially from the spa town of Sandanski.

Blagoevgrad

The largest city in the southwest of the country, Blagoevgrad has a population of around 75,000 and sits at the foot of the Rila Mountains on the banks of the Blagoevgradaksa Bistritsa River. A major spa resort since the 16th century, it has 30 hot springs, some with temperatures of up to 55°C (130°F). A centre of learning since the Rila monks set up a university in the 17th century, it today plays host to four universities and thousands of students who swell the population during term time. Though devoid of real attractions, apart from the fine History Museum (Mon–Fri 9am–noon, 1–5.30pm), Blagoevgrad is a worthy stopping-off point for its cultural mix and access to more interesting parts of the region.

With its annual influx of budding young minds, Blagoevgrad is one of the major cultural centres of Bulgaria. The city supports a chamber opera noted throughout the country, as well as the Pirin Folk Ensemble, Bulgaria’s most popular folk music combo, which can be seen on stage at the American University when not on tour.

Out of town at Stob, a short bus journey from Blagoevgrad on the route to the Rila Monastery, are weirdly shaped natural red rock formations known as the Stob pyramids 7 [map]. A well signposted path and set of steps from the main road makes access to the pyramids straightforward. The Bachinovo Park, just north of the town, is a favourite hiking venue, while further along the same valley is Bodrost, a spa resort and hiking centre that allows access to the Parangalitsa nature reserve and the ancient fortress of Klissoura.

A colourful pedestrian street in Blagoevgrad

Shutterstock

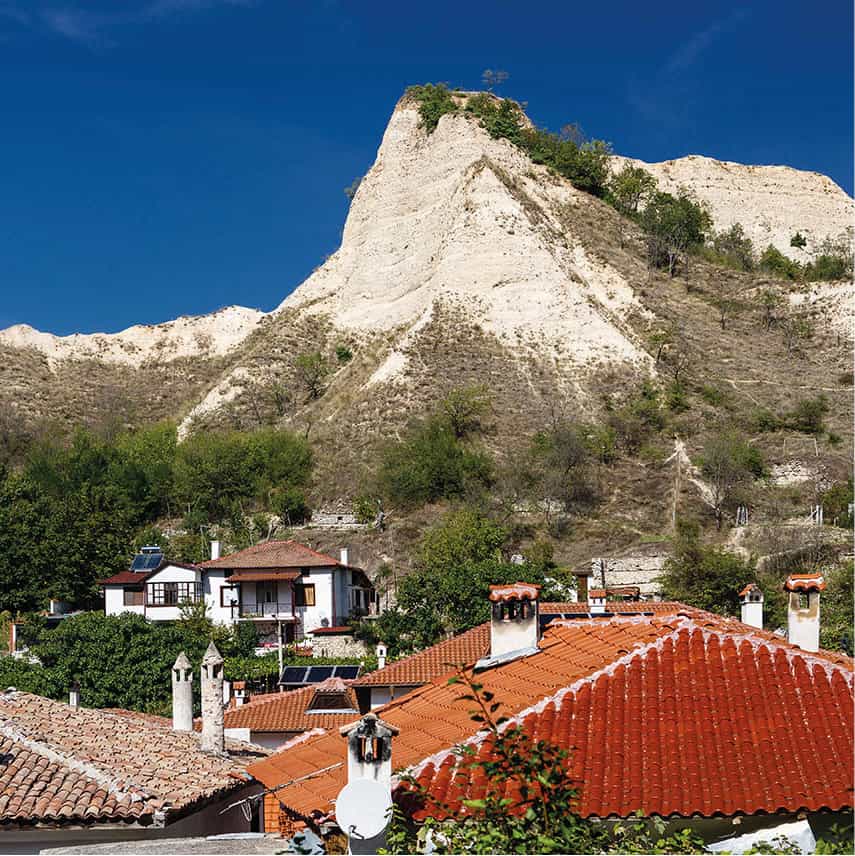

Sandstone crags, Melnik

iStock

South of Blagoevgrad

Close to the Greek border, Sandanski 8 [map] is another spa town, set in the Pirin foothills at an altitude of 240m (787ft). Named after Yane Sandanski, a Macedonian rebel who fought against the Turks, it is located on the site of an old Thracian settlement that made good use of the springs. The Romans built a huge public bath complex, the Askelpion, and the town flourished until the 6th century when it was destroyed and fell into decay. When Bulgaria was fully liberated from Turkey in 1912, the town had a population of around 500. Today it is home to 25,000. The town’s large, if dated, public bath complex remains very popular and is well worth a day’s bathing. Find it behind the cruise-ship-shaped Hotel Sandanski.

To the southeast of Sandanski is Melnik 9 [map], a living museum set gloriously amid steep slopes and crags. Once populated almost exclusively by Greeks, the town is now virtually deserted, never having recovered after being largely destroyed during the Balkan Wars of 1912–13. There remains, however, much to see. A number of Revival-period houses can be visited (opening times vary), while to the south of the town above the river, on the Nikolova Gora – about 30 minutes’ walk uphill – are the Sv Nikola Church and the fearsome remains of a Slav fortress. The views of the town below are stunning.

Melnik is also the gateway to Rozhen Monastery ) [map], which is 6km (4 miles) further on and accessible by bus. The original 13th-century monastery was burnt down; the current structure dates from the 17th century. Most visitors prefer to walk, however, either along the road or by two mountain routes – one taking about two hours, the other three hours; both are well signposted from Melnik. The road is popular because it passes some of Bulgaria’s most spectacular sandstone pyramids, several more than 80m (260ft) tall, cut over thousands of years by the Melnik and Rozhen rivers, with rain doing the rest of the sculptural work. Most are not pyramids at all, but various odd-looking shapes.

Skiers in Bansko

Shutterstock

Bansko

The undisputed winter capital of Bulgaria, Bansko ! [map] is the largest ski resort in the Balkans. Since the local council invested heavily in building a vast network of new ski lifts during the 2000s (including a gondola lift direct from the city centre to the ski area) this sleepy town – whose centre is packed with National Revival-era houses – has become one of the most popular skiing destinations in Europe. Although it shows some signs of over-development (the outskirts of the town are blighted by half-finished, abandoned or simply empty apartment complexes) the snow-sure skiing – almost all slopes are above 1,400m/4,600ft – a great selection of hotels and restaurants, and superb nightlife make Bansko an ideal choice for skiers and non-skiers alike.

There is far more to Bansko than skiing; the town has been a popular destination for many years. Its cobbled streets are lined with fine houses, many of which date from the beginning of the 19th century when the town was an important trading centre on the overland route from the Middle East to the Aegean Sea. Bansko grew rich on the back of commerce, and grand houses, churches, schools and cultural buildings sprang up apace. Although the town’s prosperity suffered towards the end of the century, when the Danube was opened to traffic and the trade route ceased, Bansko was revived in the early 20th century as a weekend holiday destination for Sofians.

Even the planners of the socialist era preserved the atmosphere of Bansko, and the modern areas of the city around the central square, pl Nikola Vaptsarov – named after Nikola Vaptsarov, a revolutionary poet – blend with the old. The most notable sights in Bansko are centred on the older pl Vazrazhdane. The Church of Sv Troitsa is the largest in the region and was completed in 1835, when Bansko’s prosperity was at its height. Large does not always translate as enthralling, however, and the outside of the church is rather bland. The interior is much more interesting, with icons painted by Dimitar Molerov, a leading figure in the Bansko School of Art that flourished at the same time as the town. The stone tower in the courtyard was added 30 years after the church had been completed.

Anyone with an interest in Bulgarian culture or history might like to visit the Neofit Rilski House Museum (Mon–Fri 9am–1pm, 2–5pm), located behind the church at ul Pirin 17. This was the childhood home of Neofit Rilski, a leading member in the Bulgarian cultural revival of the 19th century, who, among other achievements, was a member of the scholarly collective that first translated the New Testament into Bulgarian. The house has been preserved to retain its original appearance; inside photographs explain Rilski’s career. The Icon Museum (Mon–Fri 9am–1pm, 2–5pm) in the Rilski Convent, on the other side of pl Vazrazhdane, is another gem, showcasing the works of Dimitar Molerov and his contemporaries, who produced countless masterpieces for the merchants of the town who patronised the Bansko School.

Church of the Virgin Birth, Rila Monastery

iStock

The Rafail Cross

A unique specimen of the art of woodcarving, the Rafail Cross in Rila Monastery is made from a piece of wood 81cm x 43cm (32in x 17in) in size. It was made in the latter half of the 18th century by a Rila monk, Rafail, who took 12 years to complete it. Interwoven in the miniature carving are 104 religious scenes and 650 small figures: the largest carving is no bigger than a grain of rice. Rafail used fine chisels, small knives and a magnifying glass in his work, and all but lost his sight as a result.

Rila Monastery

Northeast of Blagoevgrad lies the Rila range, and Bulgaria’s most visited attraction. Rila Monastery. The Rila range is the sixth-highest in Europe and the Moussala, at 2,925m (9,600ft), is the highest mountain in the Balkans. The range is home to thousands of small lakes. Samokov is the region’s main town.

Among the peaks, valleys, lakes and forests lies the world-famous Rila Monastery @ [map] (Apr–Oct daily 8.30am–7.30pm, Nov–Mar daily 8.30am–4.30pm), an outstanding example of National Revival-period architecture. It can be seen in a rushed day-trip from Sofia, but a more leisurely visit is recommended, with tours departing from Borovets, Bansko and Blagoevgrad almost every day of the year. There is a regular bus service to the monastery from Blagoevgrad, Dupnitsa and the small village of Rila. Independent travellers with cars can drive to the monastery from Blagoevgrad in less than an hour.

A monastery has stood on this site since St John of Rila (Sveti Ivan Rilski, patron saint of Bulgaria) founded one in the 10th century, but the current structure dates from 1816–47, the original having been all but destroyed by the Turks in the 18th century. The East Wing Museum was completed in 1961.

From the outside the monastery looks like a medieval fortress, and the wonders of the interior are a hidden delight. The most spectacular of the monastery buildings is the Church of the Virgin Birth, with sublime porticos and colonnades. Inside the church, the elaborate icons and use of gold leaf betray the wealth of the monastery builders and the power that the region once had. The Hand of St John of Rila, a relic of the saint, is kept inside the church, though it is rarely on display. Another treasure is the 12th-century Icon of the Virgin, which can usually only be seen on Assumption Day, 15 August.

The elegant Tower of Hreylo looms large beside the church, and is the only part of the original monastery that survives. The Preobrazhenie Chapel on the top floor houses a fine museum of 14th-century murals. Most of the original treasures of the monastery are now housed in the East Wing Museum, including the doors of the Hrelyo Church, icons and the beautiful Rafail Cross (see box).

Something resembling an entire village has now grown up around the monastery to serve the tourists and pilgrims who visit it all year round, including two hotels, the Tsarev Vruh and the Rilets, of which the latter is easily preferable. The monastery also offers the most basic of accommodation in its dormitories.

Borovets ski resort

Shutterstock

Borovets

The largest of Bulgaria’s purpose-built ski resorts, Borovets has been playing host to visitors since the mayor of nearby Samokov built a chalet here for his wife in the 1890s to alleviate her tuberculosis; other wealthy families – including the tsar’s – quickly followed suit. The resort remained an exclusive hideaway of the rich until the 1950s, when the Communist authorities developed it, primarily for the use of party members. The idea of investing heavily in hotels and ski lifts to attract foreign cash was a 1960s’ afterthought. Since then the resort has seen massive development and is today dominated by two enormous hotels, the Rila and the Samokov, almost self-contained resorts in themselves. From the Rila a network of chairlifts and drag lifts branch out to form one of the ski areas, known as the Sitnyakovo, while a fast gondola lift takes skiers up to the second ski area, the Yastrabets, from its terminus just beside the Samokov. In all there are around 55km (35 miles) of piste in Borovets, some of it quite challenging. Snow is reliable from late December to the end of March.

Once the snow has gone, skiers give way to hikers, but this is not the best walking country in Bulgaria. The most interesting and, for the fit, challenging is the walk up to Yastrabets, which takes a good five hours, and from there onwards to the peak of Musala is another hour and a half.

Wherever you stay in Borovets, prices are usually cheaper as part of a package tour. Turning up on spec can be expensive, and at weekends during both the winter (February and March) and summer (July and August) high seasons is risky, as the resort can be full.

Plovdiv and the Rhodope Mountains

Plovdiv, in the Plain of Thrace, is the country’s second-largest city, and perhaps the most picturesque. The Rhodopes, which spread out from the plain in a generally southerly direction, are a meandering range of mountains that offer good hiking and walking. There is skiing, too, at Chepelare and Pamporovo.

Philip of Macedonia founded Plovdiv £ [map] in 342 BC, and named the town Philipopolis after himself. For centuries it was little more than a garrison town, until the Romans developed its potential as a trading halt on the route from Constantinople to Belgrade. Known to the Romans as Trimontium, Plovdiv today has a population of almost 400,000. It is a genuine rival to Sofia in terms of historical importance, and although a Sofian would baulk at the suggestion, given the variety of good hotels, cafés, bars and restaurants, its vibrant cultural scene and access to the Rhodopes, Plovdiv may indeed be a finer place to spend a few days than the capital itself.

The Roman Stadium and the Dzhumaya Mosque

Shutterstock

Downtown Plovdiv

The centre of modern Plovdiv is the megalithic pl Tsentralen, a public square too big for itself and the town, dominated by the Trimontium Princess Hotel, one of the city’s best. Remains of the Roman Forum were discovered when the square was built, and are now preserved in an area next to the post office. The west of the square is bordered by the Tsar Simeon Park, a well-kept but attraction-free garden, popular with courting teenagers.

Leading directly northwards from pl Tsentralen is the pedestrianised Alexander I Boulevard, the major shopping street. The Plovdiv City Art Gallery (Mon–Fri 9am–5.30pm, Sat–Sun 10am–5.30pm) has a small, yet well curated, collection of both 19th-century and contemporary pieces. Look out for the seated statue of Milo: an eccentric who wandered the street for decades and became a symbol of modern Plovdiv.

At its northern end, bul Alexander I reaches pl Dzhumaya, a microcosm of Bulgarian history, containing the impressive ruins of a Roman Stadium and one of the most stunning mosques in the country, the Dzhumaya Dzhamiya (Sat–Thu). One of 53 mosques erected by the Turks in Plovdiv during their 500-year rule of the city, the Dzhamiya was built in the 14th century, during the reign of Murad II (1359–85). Its thick, high walls and 25m (82ft) -high minaret dominating the surrounding area. The area of narrow streets behind the mosque is known as The Trap and has in recent years become a cultural and nightlife hub.

The Roman Amphitheatre

iStock

Old Town

The best way to enter Plovdiv’s Old Town is to follow ul Saborna, which meanders uphill to the Nebet Tepe Citadel from pl Dzhumaya. The first sight that looms on the right (up some steep steps) is the Church of the Virgin Mary (daily 7.30am–7pm) with a strikingly colourful pink and blue clock tower. A short detour from here is the splendid Roman Amphitheatre.

Built in the 2nd century during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, it is the best preserved Roman monument in Bulgaria. It is now used as a venue for operas, plays and concerts almost every evening throughout the summer, most notably the annual Verdi Festival, usually held during the first week of July. Back on ul Saborna you will pass the small Gallery of Fine Arts (Mon–Sat 9am–5.30pm) and the Apteka Hipokrat (daily 10am–5pm), a fascinating – but again, small – pharmaceutical museum. Next comes the House of Zlatyu Boyadzhiev at No. 18 (Mon–Fri 9am–5pm), a gallery dedicated to Zlatyu Boyadzhiev, a talented modern painter whose reputation is tainted by his one-time willingness to please the Communist Party with socialist-realist works depicting idealised, happy peasants.

Two doors further along is the Icon Museum (daily 9am–12.30pm, 1.30–5pm) packed to the rafters with religious art from the surrounding region, while next door is the Church of Ss Konstantin i Elena, the oldest Christian church in Plovdiv, built on what was the wall of the original Macedonian fortress. Some of the icons inside date from the 14th century, although master iconographer Zahari Zograf added many more during the National Revival in the 19th century. Next to the church stands the Hisar Kapiya, the eastern gate of the Macedonian fortress, though little of the gate we see today is original.

From the gate, carry on up the ever steeper hill towards the shabby ruins of the Nebet Tepe Citadel. Plovdiv’s stunning Ethnographical Museum (Tue–Thu, Sat–Sun 9am–noon, 2–5pm) is on the right, at ul Chomarov 2. Set in the large, charming former house of Greek merchant Argir Koyumdzhioglou, the museum collection is good, but it is the house (dating from the 1840s) and gardens that people come to see. Chamber concerts are performed in the gardens in the summer.

Passing back under the Hisar Kapiya, you reach the ornate Museum of National Liberation (Tue–Sun 9am–noon, 2–5pm) in the former home of a wealthy Turkish merchant. The museum is an excellent primer on the Bulgarian National Revival and struggle for liberation, with many exhibits carrying English captions.

Asenovgrad Fortress

Shutterstock

South of Plovdiv – the Central Rhodopes

Assenovgrad $ [map], the first town south of Plovdiv, is famed for its vineyards, but there is little here to keep you, apart from the medieval fortress, a short distance outside of town on the road to Smolyan, and the Bachkovo Monastery, second only to Rila among Bulgaria’s finest religious buildings.

Bachkovo Monastery

Shutterstock

The Fortress of Assenovgrad (Assenova Krepost) has a fabled history of command and conquest, though its remains today are less than worthy of its past. The steep rocky hillside is a perfect position to guard the access to the Plain of Thrace and it was first used as a defensive bulwark by the Thracians, though the first substantial fortress was built during the reign of Tsar Ivan Assen II in the 13th century. The best preserved part is the Petrich Church of the Virgin Mary (Wed–Sun 8am–5pm), dominating the site.

Founded in 1083 by a Byzantine statesman of Georgian origin, the Bachkovo Monastery % [map] (daily 7am–9pm, guides available 10am–4pm), 11km (7 miles) south of Assenovgrad, is a fine collection of well-preserved historic buildings from various eras. Highlights are the refectory, with frescoed walls depicting the monastery’s history, and two churches, Sv Nikolai and the Church of the Virgin Mary, the oldest building in the monastery, dating from 1604. The Church of the Virgin Mary houses the Icon of the Virgin, supposed to have been brought from Georgia in 1310. Every year on St. Mary’s Day, 15 August, it is paraded by thousands of pilgrims in a procession around the monastery.

Chepelare and Pamporovo

An upgraded chair-lift has revolutionised the previously limited skiing at Chepelare, which looks set to become the country’s next boom resort, although most visitors to this region still make a bee-line for Pamporovo, the most developed of Bulgaria’s ski centres. A bus links the two resorts, which share a lift-pass. Pamporovo is great choice for families, it is far more suited to beginners than other Bulgarian resorts. The gentle slopes make for easy skiing (there is, however, one short black run called ‘The Wall’, recognised as the toughest piste in the country), and the ski-schools are excellent. While it offers a great choice of hotels, Pamporovo has nevertheless resisted the temptation to expand bed capacity too much. Lift queues here are short, even at weekends. During the summer Pamporovo is all but deserted, and makes a peaceful destination for gentle walks and fine air.

Church in Shiroka Laka

Getty Images

Bears

Bulgaria is home to approximately 750 brown bears, one of the largest populations in Europe. The majority live in the Rila and Rhodope mountains at an altitude of around 1,100m (3,600ft). Small numbers are hunted each year, though these are usually problem bears identified by the authorities as dangerous to the overall well-being of a group. The high charges paid by hunters also help to fund conservation programmes. Contact with people is extremely rare (about 150 cases each year), of which about a third end with bears attacking humans.

The Western Rhodopes

Heading west from Pamporovo – with a car preferably, as public transport in this remote part of Bulgaria is often non-existent – you enter an area populated almost entirely by a people known as the Pomaks, Bulgarians converted to Islam by the Turks in the 17th century. Though the occasional Christian village is dotted here and there, mosques dominate the landscape.

Shiroka Luka ^ [map], a short distance from Pamporovo, is a village museum often full of package tourists from Pamporovo trying to get a feel of the real Bulgaria. Though short on individual attractions, apart from the Church of the Assumption, which has Zograf frescoes, the village is a delight to amble around, with cobbled streets, large Rhodope houses and picturesque courtyards. It is also a great place to witness the Kukeri festival, which takes place each year on the first Sunday of March (for more information, click here).

Passing through the spa town of Devin, most visitors head straight for the Trigad Gorge, a steep, narrow chasm cut by the lively River Trogradska. At the apex of the gorge the river plunges down into a cave known as the Dyavolskoto Gurlo or Devil’s Throat & [map] (Wed–Sun; guided tours only; charge discretional), one of the most spectacular natural sights in the country. A viewing platform has been positioned over the point where the river goes underground, while the tour of the cave, which is memorable for its sheer size and deafening echo of gushing water, is not for the faint-hearted. The village of Trigrad has little to recommend it, but it has a couple of good hotels that make it a popular base for hiking and caving. The neighbouring village of Yagodina is a major centre for Bulgarian caving.

A short drive or a long hike from Trigrad, heading back towards Devin and turning right shortly before the gorge, is the village of Mugla, which wouldn’t figure on any map were it not for the annual gaidi (bagpipe) festival that takes place here each August.

The Kardzhali pyramids

iStock

The Eastern Rhodopes

The remote Eastern Rhodopes are best accessed via Dimitrovgrad, an hour’s drive from Plovdiv. Along with Kraków’s suburb of Nowa Huta in Poland, Dimitrovgrad shares the distinction of being an entirely planned socialist-realist city. Built in the 1950s, its wide boulevards and monumental apartments blocks are potholed and faded today, but the scale is a testament to the belief once placed in Communism.

Heading south into the mountains the pink Kardzhali pyramids greet visitors to the town of the same name. Just one of many weird rock formations in the once volcanic area, the pyramids (also known as the Svatba Vkamenenata, or Stone Wedding) are said to be a wedding party turned to stone by the gods to punish the bridegroom’s mother for envying the bride’s beauty. Kardzahli is a nice enough town, but the only real sight is the ruined fortress of Perperikon, 20km (13 miles) northeast of town, where archaeologists have unearthed layers of civilisation going back some 7,000 years.

The Eastern Balkans

Characterised by magnificent scenery and endless historical tales of heroism, liberation and derring-do, the Eastern Balkans form what is often described as both the cradle and the nursery of the Bulgarian nation. The magnificent fortress at Veliko Tarnovo defended one of the largest cities in -medieval Europe when it was capital of the Second Bulgarian Kingdom; monasteries were built in abundance – there are more than 40 in the region – and the largely unspoiled area remains today a symbol of national pride and togetherness.

Veliko Tarnovo

The majestic capital of the Second Bulgarian Kingdom, Veliko Tarnovo * [map] is one of the most picturesque cities in Bulgaria, mainly due to its setting on the steep banks of the Yantra River. Offering a good choice of accommodation, it is an excellent base from which to explore the historically significant surrounding area. The exquisite village of Arbanasi is close by, as is the Preobrazhenski Monastery, the finest and best preserved in the region.

At various times called Ternov, Trunov, Turnovgrad or simply Tarnovo, Veliko Tarnovo’s existence has long depended on possession of the imposing citadel that sits atop Tsaravets (daily Apr–Sept 8am–7pm, Oct–Mar 10am–5pm), the highest of the three sacred hills among which the city nestles. The main attraction in Veliko Tarnovo, Tsaravets was first settled by the Thracians, though the first fortifications were probably constructed by the Byzantines in the 6th and 7th centuries. As the Byzantine Empire declined, that first fortress fell into ruins, which were built on in the 10th century by the Slavs, who were responsible for much of the structure that can be seen today. By the 12th century, the city was densely populated. Its position as the cradle of the nation was set in stone in 1187, when the successful rebellion of Peter and Assen against Byzantium was launched from Tsaravets, and Peter proclaimed a new Bulgarian Kingdom. Over the next 200 years the town flourished, until the summer of 1393 when, after a three-month siege, the overwhelmingly powerful Turkish army overran the citadel and set the town alight.

Tsarevets Fortress

iStock

What remains of the fortress today is dominated by its restored southern ramparts and Baldwin’s Tower, while the Bulgarian Patriarchate, with an orange exterior and green domes, towers above the ruins of the Tsar’s Palace, which only hint at the size it must once have been.

A number of other churches surround the Tsaravets, the best preserved being the Church of Peter and Paul – at the foot of Tsaravet’s northern slopes where the Yantra performs one of its many U-turns – and the Church of the 40 Martyrs, slightly further along Mitropolska towards Old Town.

Veliko Tarnovo’s Old Town can become crowded with day-trippers, but it’s usually a relaxed, even sleepy place, perfect for exploring on foot. Unfortunately, administrators of the three museums (Archaeological, National Revival and History; all daily 9am–6pm) in the centre fail to understand that non-Bulgarians may be interested in the country’s history; all captions are in Bulgarian only and there are no guided tours.

Veliko Tarnovo in winter

iStock

From the Old Town, most visitors make their way up ul Jamiyata, which leads to pl Velchova Zavera and the House of the Monkey, so called because a tiny monkey statue sits below the first-floor bay window. The market in pl Samodivska, behind pl Velchova Zavera, is one of the best places in Bulgaria to find handmade pottery (for more information, click here).

From here begins ul Stamboliski, the city’s primary commercial street, with shops, cafés and restaurants, a number of which have small terraces at the back that offer great views of the valley below. The monument in pl Pobornicheski marks the site where revolutionaries Bacho Kiro, Tsanko Dyustabanov and Georgi Izmirliev were hanged by the Turks in 1876. More shops, cafés and restaurants line the route towards pl Nezavisimost, the centre of modern Veliko Tarnovo.

The huge, orange building that dominates the lower part of Veliko Tarnovo is the Boris Denev Art Gallery (Tue–Sat 10am–6pm). The awful monument in front of it is a tribute to the Assen Dynasty, put up in the 1980s as part of the ‘1,300 years of Bulgaria’ celebrations. Surrounding the art gallery is a shaded park with gentle paths perfect for afternoon strolls.

Preobrazhensky Monastery

Shutterstock

Around Veliko Tarnovo

The village-museum of Arbanasi ( [map], a 10-minute drive uphill from Veliko Tarnovo, has more charms per square kilometre than any other village in Bulgaria. A flourishing trade and craft centre from the middle of the 16th century, the village is made up of monumental fortress-style houses and exquisite churches. The best of these is the Church of the Archangels Michael and Gabriel on a small hill above the village’s park, and the Kostantsialev House (Tue−Sun 9am–6pm) on the other side of the park. In all, there are five house-museums and four churches, as well as two rather plain monasteries.

Returning to Veliko Tarnovo and taking the main road for Ruse, the Preobrazhensk Monastery is situated about 6km (4 miles) north of the town. One of many monasteries in the area founded in the 14th century, it flourished during the Second Bulgarian Kingdom only to be burnt by the Turks after they had taken Veliko Tarnovo. Rebuilt in the 19th century during the National Revival, it is a fine example of the era’s architecture and iconography. The central Church of the Transfiguration includes two characteristic frescoes by Zahari Zograf, the Last Judgement and the Wheel of Life. There are two other churches in the monastery, the Church of the Annunciation, with icons by Stanislav Dospevski, and the Church of the Ascension. The bell in the courtyard’s bell tower was a gift from Russia’s Tsar Alexander II.

South of Veliko Tarnovo is the equally remarkable Kilifarevo Monastery. Founded by Teodisil Turnovski as a centre of Hesychasm, a religious doctrine that preached unity with God through isolation, it was another monastery burnt to the ground by the Turks in the late 14th century, only to be refounded and rebuilt in the 19th century. Its impressive central church, the Church of Sv Dimitar, includes a stunning portrait of St John of Rila by Kristu Zahariev.

Memorial to Freedom, Shipka

iStock

South of Veliko Tarnovo

Southwest of Veliko Tarnovo towards Kazanlak is the small town of Dryanovo, another town associated with rebellion and nationalism. Dating back to the 12th century, the town’s Monastery, 4km (2 miles) further on, was the site of an anti-Turkish uprising in 1876, when 220 revolutionaries led by Bacho Kiro held a large Turkish army at bay for nine days before the Turks blew the monastery up and hanged the rebels in Veliko Tarnovo. Most of the monastery’s buildings were fully restored after liberation. Just beyond the monastery is the floodlit Bacho Kiro Cave (daily during the summer, irregular hours), a good opportunity to see stalactites and stalagmites.

Climbing steadily into the Balkans, Gabrovo, gateway to the Shipka Pass, is a former textile town with little to offer except a Museum of Humour and Satire (ul Bryanska 64; Apr–Oct daily 9am–6pm, Nov–Mar Mon–Sat 9am–6pm) and a festival in May in odd-numbered years, the International Biennial of Humour and Satire. The museum and festival are in Gabrovo because it is the traditional butt of most Bulgarian jokes, usually involving meanness and stupidity. Some 8km (5 miles) southeast of the town is Etura (daily 8am–6pm), a craft centre set up to preserve the town’s traditional skills. The complex’s houses, workshops and mills recreate with astonishing realism what life was like in Gabrovo 150 years ago.

South of Gabrovo is the stunning Shipka Pass , [map], equal in majesty to the Iskar Gorge and every bit as deserving of its legendary status among local people. It was here that Alexander the Great won one of his first major victories as Macedonian leader in 335 BC and where – more importantly for Bulgarians – in August 1877 a Bulgarian and Russian force held back 30,000 Turks, thus allowing Pleven to be taken by other Bulgarian and Russian forces. Today, at the 1,326m (4,350ft) summit of Mt Stoletov, you will find the Memorial to Freedom, which is accessible from the road by 894 steps. The memorial houses a small museum (9am–5pm) dedicated to the battle. Beyond the apex of the pass, the village of Shipka is home to the splendid, pink, white and golden-domed Shipka Memorial Church, built in 1902 to commemorate the battle.

Rose Oil

Bulgaria has been one of the world’s leading producers of rose oil since the 18th century, when Turkish traders noticed that the area around Kazanlak (now known as the Valley of the Roses) would be perfect for cultivating the flower. Harvesting the rose is a race against time, as the flower must be picked before 9am, when it is still wet with dew. The harvest must then be rushed to the distillery before the oil has evaporated. Bulgarian steam-distilled rose oil, 100 percent pure, is today recognised as being the finest – and most expensive – in the world, and is used in the production of perfumes, as well as in meditation. The Festival of the Roses is celebrated every June in Kazanlak.

Kazanlak and Stara Zagora

During the first weekend of June each year, the town of Kazanlak holds the Festival of the Roses, an age-old pageant celebrating the rose harvest of the surrounding villages, which together form what Bulgarians refer to as the Valley of the Roses. The roses are in full bloom during the late spring. Kazanlak became rich on its rose oil during the 18th century, and today the Museum of the Rose (daily 9am–5.30pm) in Tyubelto Park tells the story.

The biggest draw in town, however, is the Thracian Tomb, also in Tyubelto Park, dating from the 4th century BC and excavated in 1944. So precious is Bulgaria’s finest surviving example of Thracian art that the tomb is closed to the public. The replica (daily 9am–5pm) next to it is a perfect reproduction of the original in every respect, from the red floors to the stunning frescoes on the domed ceiling.

Situated in the geographical centre of Bulgaria, Stara Zagora is one of the country’s largest cities. Founded as Beroe in the 6th century BC by the Thracians it became the Roman town Augusta Traiana, the Byzantine town Irinopolis and the Turkish town Eski Zaara, before being completely destroyed by the Turks during the war of liberation. After independence it was rebuilt following a grid system devised by the Czech urban planner Lubor Bayer. As with most planned towns, Stara Zagora lacks character and has little to offer the visitor except the Bereketska Mogila Neolithic Dwellings (Tue–Sun 9am–noon, 2–5pm; English guided tours), the largest prehistoric settlement unearthed in Bulgaria. The dwellings date from at least 5500 BC and provide a fascinating insight into the life of the ancient people who lived in them.

Hotel complex in Albena on the Black Sea

Shutterstock

The Black Seas

Of all Bulgaria’s charms as a holiday destination, it is the fantastic beaches and warm waters of the Black Sea that have been attracting tourists the longest. From brash Sunny Beach to chic Albena, from enchanting Balchick to bewitching Nessebur, Bulgaria’s 400km (249 miles) of coastline offer everything: golden sands, rocky coves, nature reserves and delightful fishing villages. The region can be rough around the edges: the transport infrastructure is poor (particularly the roads), customer service can be under par, and many resorts are blighted by construction sites. But for a great-value summer holiday there is nowhere in Europe to match Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast. To get the best of it, spend a week or two at one of the many good hotels in the major beach resorts of Golden Sands or Sunny Beach, but don’t neglect to visit the real gems: little Nessebur and ancient Sozopol.

A town called Stalin

From 1947–56 Varna was officially named Stalin in honour of the Soviet leader. A number of other cities in Eastern Europe, including Brasov in Romania, suffered a similar fate.

Varna

The third-largest city in Bulgaria, Varna ⁄ [map] is part seaport and part beach resort. It has a mish-mash of cultures and architectural styles and a brashness that characterises most Black Sea towns and cities. Most of the thousands of tourists who come here on package tours head straight to the nearby resorts of Golden Sands and Albena, but Varna itself is definitely worth a look: a city of 350,000 that offers a vibrant café and restaurant scene, great museums, a rich cultural heritage and one of the finest operas in Bulgaria. It is also the best place to shop, outside the capital. Like much of the Black Sea coast, however, Varna remains a little tatty around the edges.

Although there was once an ancient Thracian settlement close by, the city dates from the 6th century BC, when Greek colonists founded the little settlement of Odessos, which quickly became an important centre of trade and fishing. Conquered in turn by Alexander the Great and the Romans, the city flourished under both of these empires until Barbarians destroyed it in 586. Repopulated by the Slavs, who gave the town its present name, Varna remained a city on the fringes until the 19th century when it became the most important sea port within the newly independent Bulgaria.

Varna Opera House

iStock

Pl Nezavisimost, Varna’s pedestrianised central square, surrounded on all sides by terraces and cafés in the summer, is dominated by the shocking-pink, 19th-century Varna Opera House and Philharmonia, and the Old Clock Tower, dating from 1880. Across the main boulevard, Hristo Botev, stands the 19th-century Cathedral of the Holy Virgin A [map], more impressive from afar than it is close up. The interior is spectacular – the icons and frescoes took 25 years to complete – but the exterior is in need of repair and you will be asked to make a donation, before being blessed, as you make your way inside. A good market, selling local embroidery and lace along with the usual souvenirs, surrounds the cathedral.

From here, a short walk along the pleasantly wide Maria Luiza Boulevard brings you to the Varna Archaeological Museum B [map] (daily 10am–5pm), the city’s best museum. Set in splendid gardens, it was built as a school during the National Revival. Various exhibits vie for your attention, including miniature models of Palaeolithic pile dwellings, ancient art and jewellery, and various ancient Egyptian, Greek and even Babylonian artefacts.

The awful skyscraper on the other side of the road is the Town Hall. Just north of here, on Rakovski Boulevard, is the Church of Sv Petka, famous for its striped walls and marvellous central cupola. To the south of the Town Hall is the Art Gallery (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm), which houses a fine collection of Bulgarian and foreign art.

From the art gallery, it is a short walk to Knyaz Boris I Boulevard, the city’s main thoroughfare and shopping street, which buzzes from morning until late at night throughout the summer. A short distance along this pedestrianised street is the Sv Nikola Church, which was built in 1866 and contains icons by many of the finest Bulgarian masters, though much of the church is inaccessible at present due to restoration work. Just round the corner is the National Revival Museum C [map] (ul 27 Yuli; Mon–Fri 10am–5pm), a church and Varna’s first Bulgarian school, which became a museum in 1959. The story of the city’s history and liberation is told, in English and Bulgarian, in well-preserved classrooms.

Heading towards the port along Han Krum, the Church of Sv Bogodoritsa looms on the left. This was built in the 17th century according to Turkish rules that limited the height of churches, hence its sunken foundations and afterthought of a tower. On the other side of the road are the Roman Thermae D [map] (Tue–Sat 10am–5pm), built in the 2nd century and abandoned to the Barbarians in the 6th century. After much restoration work, the baths are now one of the city’s most important archaeological sights. Almost adjacent to the Thermae is the Church of Sv Atanasii, a fine example of National Revival architecture. Another classic of the National Revival period houses the Ethnographic Museum E [map] (Apr–Oct daily 10am–5pm, Nov–Mar Tue–Sun 10am–5pm). Exhibits include various Kukeri masks, making this a good opportunity for travellers not fortunate enough to experience a Kukeri festival to see just how bizarre these events are (for more information, click here).

The municipal beach, Primorski Park

Shutterstock

Primorski Park

The huge Primorski Park F [map], stretching from Varna’s port almost to the pleasant, tiny beach resort of Sv Konstantin, took years to lay out and was finally completed in 1908. It is very popular with local people, who flock here to sunbathe on Varna’s excellent municipal beach or attend pop and rock concerts throughout the summer at the open-air theatre. The numerous terraces, pubs and discos lining the beach front are full most nights all summer long.

The park has various attractions, some of dubious quality. Like the park itself, both the Naval Museum (daily 9am–5pm) with naval hardware, at the far western end of the park, and the Aquarium and Black Sea Museum (June−Sept 9am–7pm, Oct−May 9am−5pm) have seen better days, but both remain favourites with children. Also popular with children are the Planetarium (June–Sept 9am–3.30pm, shows every 90 minutes; Oct–May by prior appointment) and the Dolphinarium (shows at 10.30, noon, 3.30pm, 5pm) at the other end of the park. The Zoo (May–Sept daily 8am–8pm, Oct–Apr daily 8.30am–4.30pm) in the middle of the park features a large number of animals including camels, emus and other exotic birds, spiders, snakes, crabs, frogs, geckos and rodents.

Aladzha Monastery

In a forest northwest of Golden Sands are the remains of the rock-hewn Aladzha Monastery (Tue–Sun 9am–6pm), founded in the 14th century and populated by the Hesychast order of monks until the 18th century. There is a small museum that shows how the monastery looked when it was occupied.

The beach and hotels in Golden Sands

Shutterstock

Golden Sands

Known to Bulgarians as Zlatni Pyusatsi, Golden Sands is a sprawling, purpose-built seaside resort 18km (11 miles) north of Varna. A staple of Western European holiday brochures, it is the best known of all the Bulgarian beach resorts. Always make sure you have accommodation booked before arriving, as hotel rack rates are far higher than those offered by online booking companies and tour operators. At busy times the resort can often be full.

Although perhaps not quite golden, the 5km (3-mile) beach is fabulous, sloping gently to the sea, and offering every water sport from parascending and water-skiing to jet-skiing and windsurfing at various points along its length. The resort’s small marina is at the northern end of the resort, beyond which is a nudist beach. There is a water park, Aquapolis, behind the resort on the other side of the main road from Varna to Balchik.

There are more than 70 hotels of all categories in the resort, all now in private hands and fully refurbished. Not all of the resort’s hotels are on the seafront, however, and some are quite a way from the beach. Though there is no real centre to this artificial resort, there is a collection of shops and banks around the Church of St John.

There are plenty of good restaurants and cheap places to eat throughout the resort, and an endless number of bars and discos. Both the Havan and International hotels have casinos. The resort is linked to Varna by numerous taxis (make sure you take a taxi displaying the name and phone number of a taxi company), and by bus numbers 109 and 409. The journey takes about 20 minutes one-way.

Albena

The trendiest, and consequently most expensive, of the Black Sea resorts, Albena, 30km (18 miles) from Varna, is smaller than Golden Sands and a lot younger; until 1970 there wasn’t a hotel in sight. Today the step-pyramid conceptual creations come as something of a pleasant surprise after the straight lines of Golden Sands. The resort is increasingly popular with Bulgaria’s smart set and less frequented by foreign tourists.

The beach itself is wider, whiter and quieter than Golden Sands, though there is less scope for water sports. There is an excellent equestrian centre next to the Malibu Hotel, which offers riding lessons and horse-back excursions into the surrounding countryside.

Balchik

The fact that the small town of Balchik, 15km (10 miles) north of Albena, was made famous by Romania’s Queen Marie, Queen Victoria’s granddaughter, who had her summer residence here, highlights the difficult history of the Dobruja region. Lost to Romania after the Balkan Wars, Balchik and the rest of the Dobruja was only returned to Bulgaria by Hitler in 1940. Since then it has become a popular resort with Bulgarians and Romanians, who find the place a quiet retreat. Balchik is also home to three championship-standard links golf courses.

The main attraction remains the Tenha Yuva complex (8am–5pm, gardens until 9pm in summer) the palace of Queen Marie. The simple palace itself, set on a hilltop overlooking the town, is dominated by a minaret-like tower and betrays Marie, who insisted on designing almost every detail herself, as a rather unsophisticated architect. A number of other buildings are far lovelier, including a stone summer house from where the queen watched the sea. The botanical gardens are home to more than 3,000 rare and exotic plants. Some 4km (2 miles) from Balchik is Tuzlata, a tiny resort famous for its mud treatments. At Dabolka, the Black Sea’s biggest mussel farm serves thousands of huge pots of steaming mussels every day.

Bourgas and Surroundings

The largest town on the southern part of the coast, the important port and industrial city of Bourgas, has little to offer the visitor and, with the far more attractive towns of -Pomorie, Nessebur and Sozopol all close by, it should be used only as a stopping-off point or day trip destination at best.

Pomorie, around 20km (13 miles) northeast of Bourgas, is situated on a slim, rocky peninsula separating the bay of Bourgas from the Black Sea, and has been offering mud treatments for well over 2,000 years. All the town’s hotels double as mud treatment centres, and it is difficult to find a room unless you are booked into one of the clinics. Besides mud, the town is known for salt – and wine; Pamid, Dimyat and Merlots are among the country’s best. Though narrow and often very crowded, the beach is excellent.

Best for seafood

Nessebur, at the centre of the Bulgarian Black Sea’s fishing industry, is the best place on the coast to enjoy seafood.

Old Town marina in the evening, Nessebar

Shutterstock

Nessebur

A further 18km (11 miles) north is Nessebur ¤ [map], which has Bulgaria’s best beach and some of its best preserved 19th-century wooden architecture. Split in two by a slim causeway, Nessebur is famous mainly for its old town, situated on the peninsula that juts awkwardly into the Black Sea. The town’s narrow, cobbled streets, wooden houses and medieval churches make it as much an emblem of Bulgaria as Dubrovnik is of Croatia.

Entering Old Nessebur via its Town Gate, with fortifications dating back to the 6th century on either side, it is possible to imagine how impregnable the town must have been. Once inside, the Archaeological Museum (Dec−Apr and Nov Mon−Fri 9am−5pm, May, Oct and Sept until 6pm, June until 7pm, July−Aug until 8pm; Sat−Sun Mar−May and Oct−Nov 10am−5pm, June 9.30am−2pm and 2.30−7pm, July−Sept 9am−1.30pm and 2−7pm), on the right as you enter, is a good introduction to the town’s history. From there, magnificent churches await exploration; there were once more than 40 on the peninsula and many remain worthy of your time today. Following a roughly clockwise route around the peninsula, the first one that you will see is the 14th-century Church of the Holy Pantocrator, whose exterior marks it out as one of the finest medieval churches in the country. Next is the Church of St John the Baptist, an 11th-century structure caught between the simple designs of the early Christians and the more complex, ornate churches that followed. Following ul Alehoi, the next church you encounter is the 14th-century Church of Archangels Michael and Gabriel, a stunning example of medieval craftsmanship, while next to that is the less impressive Church of Sv Paraskeva of the same era. Further on is the Church of Sv Bogodoritsa, while on the seashore are the ruins of the Basilica, which date from the 5th century.

Inland, in the middle of the endlessly busy central square, pl Mitropolitska, the 5th-century Old Bishopric (Sv Sofia) stands in ruins, while its counterpart, the New Bishopric (Sv Stefan) on ul Rilbarska, is a much-rebuilt church dating from the 11th century. The frescoes date from the 17th century, the pulpit and bishop’s throne from the 18th century. The 14th-century Church of St John Aliturgitus at the end of the same street is the best of Nessebur’s churches. Perched high above the harbour, its bizarre exterior tops anything else in the town.

Sunny Beach

Just north of Nessebur is the lively beach resort of Sunny Beach, (Slanchev Bryag). More than 150 hotels stretch along the narrow 7km (4-mile) beach, making the largest resort on the Black Sea. Having played second fiddle to Golden Sands for some time, Sunny Beach has had a revival and the completion of the Sofia−Burgas motorway has seen it become increasingly popular amongst Bulgarian families. It remains cheaper than the northern resorts, and offers great opportunities for water sports, while boasting some of the best value hotels on the coast. There are numerous restaurants and an endless number of bars and discos.

View over Sozopol’s old town

iStock

Sozopol

Approximately 30km (21 miles) south of Bourgas, Sozopol ‹ [map], just about the last town on the coast, could well be the best. An ancient fishing village on a peninsula, much like Nessebur, Sozopol’s distance from a large package holiday resort means that it does not get the day-trippers that crowd Nessebur, making it a far better place to wander around.

Like Nessebur, Sozopol is divided into old and new parts, Old Sozopol, on the peninsula, being the most popular destination for visitors. The causeway that links the two parts acts as the town’s unofficial centre, and it is always awash with hawkers selling less-than-impressive souvenirs.

The rather ordinary Archaeological Museum (Mon–Fri 10am–5pm) stands on the south of the causeway. To the right is a small park containing two of Sozopol’s Revival-period churches, the Church of Sv Zosim and the Church of Sts Cyril and Methodius, below which is the private Raiski Beach. Old Sozopol is a warren of narrow cobbled streets, wooden houses, churches, cafés, restaurants and souvenir shops. Every September Sozopol hosts the Apollonia Arts Festival, with opera, classical music and theatre, during which the town is swamped with visitors.