![]()

AS Virginians nourished an increasing contempt for blacks and Indians, they began to raise the status of lower-class whites. The two movements were complementary. The status of poor whites rose not merely in relation to blacks but also in relation to their white superiors. Virginia had always been advertised as a place where the poor would be redeemed from poverty. And during the 1630s, 1640s, and 1650s it may actually have served that purpose, though more met death than success. With the decline in mortality and rise in population the numbers of poor freemen grew too large, and the scruff and scum of England became the rabble of Virginia. But as Indians and Africans began to man the large plantations and the annual increment of freedmen fell off, the economic prospects of the paleface poor began to improve.

This is not to say that poverty disappeared from white Virginia with the introduction of slavery. A class of homeless men continued to drift about the colony, cheating the tax collectors and worrying the authorities. They crop up from time to time in petitions against them from the proper people of different counties. Accomack, which had complained earlier, joined with Lancaster and Gloucester in 1699 to request “that a law may be made to punish Vagrant Vagabond and Idle Persons and to assess the Wages of Common Labourers.”1 In 1710 Henrico County proposed a workhouse for them.2 But the assembly apparently did not consider the problem worth acting on until 1723, when it passed an act modeled after the Elizabethan poor law. The preamble noted that “divers Idle and disorderly persons, having no visible Estates or Employments and who are able to work, frequently stroll from One County to another, neglecting to labour and, either failing altogether to List themselves as Tythables, or by their Idle and disorderly Life [render] themselves incapable of paying their Levies when listed.” The act, which was renewed and enlarged from time to time thereafter, empowered county courts to convey vagrants to the parish they came from and to bind them out as servants on wages by the year. If the vagrant were “of such ill repute that no one will receive him or her into Service,” then thirty-nine lashes took the place of servitude.3

The law was probably prompted by the immigration of convicts during the preceding five years. Parliament in 1717 had authorized English criminal courts to contract for transportation to the colonies of convicted felons, to serve for terms of seven or fourteen years, depending on the seriousness of their crime; and a year later the infamous Jonathan Forward began a long and profitable career of carrying convicts to Virginia and Maryland, collecting from the British government a fee of £5 sterling for each of them and from the planters as much as they would pay, usually averaging £8 to £10. Virginia tried to protect herself by an act requiring both the importer and the purchaser to give bonds for the good behavior of these dubious immigrants and to register with the county court their names and the crimes for which they were transported. But the Privy Council disallowed the law, and the demand for labor in Virginia insured a ready market.4

Though it can be estimated that some twenty thousand convicts were carried to Virginia and Maryland during the rest of the century, and though they undoubtedly included some habitual criminals,5 the unredeemable were not so many but that they could be dealt with by traditional methods: the law that confined them to their parish and empowered the courts to put them to work was more effective in Virginia than in England because of Virginia’s unlimited demand for labor and the close supervision of plantation labor by overseers. Those whom no one would venture to employ could be disposed of by that other traditional method, the military expedition. When recruits were needed to fight the French or the Spanish or the Indians, Virginians knew where to find them. In 1736 they shipped off a batch to Georgia to guard the frontiers; in 1741 they recruited several hundred for the English expedition against Cartagena.6 And when George Washington began his military career in 1754 by attacking the French in the Ohio Valley, he was leading, by his own statement, a company composed of “those loose, Idle Persons that are quite destitute of House and Home.”7 Indeed, the Virginia assembly in ordering the troops raised had specified that military and naval officers could impress only such “able-bodied men as do not follow or exercise any lawful calling or employment, or have not some other lawfull and sufficient support and maintenance.” And lest there be any doubt, the law added that no one was to be impressed who had a right to vote in elections to the House of Burgesses.8

Virginia parishes acknowledged the same responsibility that rested on English parishes to care for the destitute who were physically incapable of supporting themselves. But the numbers involved in Virginia were minuscule by comparison with England, because the conversion to slave labor transferred from the parish to the plantation the responsibility for the unproductive and unemployable elements of the laboring class: the aged, the disabled, and the young.9 Though a master could extract as much labor from his slaves as he could drive them to, he must feed and clothe them whether they could work or not. And society did not allow him to shift the responsibility. The laws against manumission had as an object not only the limitation of the free black population but the restraint of masters who might be tempted to free a slave when he became too decrepit to work, whether the cause were age, accident, or abuse. Slavery, more effectively than the Elizabethan Statute of Artificers, made the master responsible for the workman and relieved society at large of most of its restive poor.

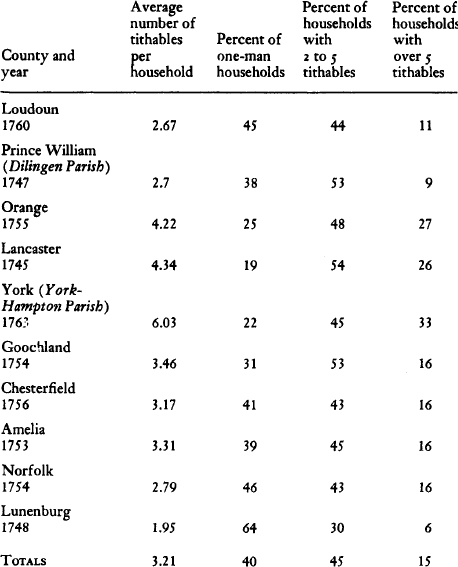

As the ranks of the free ceased to swell so rapidly, the number of losers among them declined; and in the eighteenth century as the rich grew richer, so did the poor. The most concrete evidence comes from the tithable records. As noted earlier, the most pronounced trend in these records during the third quarter of the seventeenth century was the increase in the number of one-man households, without servants or slaves. After leveling off in the last quarter of the century, the trend was in the opposite direction. In Lancaster (the only county for which both seventeenth- and eighteenth-century lists survive) 13 percent of the households had only one man in 1653, 32 percent in 1675, 38 percent in 1699, and 19 percent in 1745. If we compare surviving seventeenth-century records (see table in chapter 11) with surviving eighteenth-century records (see table below), it would appear that one-man households were decreasing, while large households with more than five tithables were increasing. The gap between the very rich and the not-so-rich had widened, but there were more of the rich and fewer of the not-so-rich.10

The same trend is observable in other figures. During the first half of the eighteenth century, while big planters were building the great mansions of tidewater Virginia and accumulating vast numbers of slaves, the moderately successful small farmer was also gaining a larger place even in this richest area of the colony. Property holdings in the tidewater declined in average size per owner from 417 acres in 1704 to 336 acres in 1750, while the number of property owners increased by 66 percent.11

Tithables per Household

Wills proved in court also point to improved circumstances for the small man. A study covering the period 1660–1719 in four counties (Isle of Wight, Norfolk, Surry, and Westmoreland) divides the testators into lower, middle, and upper class on the basis of the value of property devised. In each county lower-class testators decreased, while middle- and upper-class testators increased.12 A more detailed study embracing the whole Chesapeake region shows a similar growth in the value of testators’ estates from 1720 to the 1760s. The number of persons with estates valued at,£ 100 or less constituted 70 percent of those found around 1720. In the 1760s such persons accounted for only 41.4 percent, with a corresponding increase in those valued over £100.13

The figures of tithables, landholdings, and estate values do not mean that the small man was disappearing from Virginia. On the contrary, small planters continued to make up the great majority of the free population.14 But the figures do suggest that the small man was not as small as he had been and that the chances of becoming bigger had increased since the seventeenth century.

The change did not come entirely from forces arising within the colony. During the second quarter of the eighteenth century a marked growth in the world market for tobacco lent stability to its price and improved the position of the small man at the same time that it improved the position of the large man. Tobacco production advanced in this period even more rapidly in the poorer regions on the south side of the James and in the piedmont than it did in the richer York River area.15 But Virginia had enjoyed large economic opportunities during part of the seventeenth century without giving the small man a comparable benefit. The difference this time was slavery.

It would be difficult to argue that the introduction of slavery brought direct economic benefits to free labor in Virginia. Since the tobacco crop expanded along with the expansion of the slave population, slavery could scarcely have contributed to any improvement in the prices the small planter got for what he grew. And though the reduction in the annual increment of freedmen did reduce the competition among them for land and for whatever places society might have available, the avarice of their superiors could well have resulted in squeezing out small men as they were squeezed out of Barbados in the preceding century. Instead—and I believe partly because of slavery—they were allowed not only to prosper but also to acquire social, psychological, and political advantages that turned the thrust of exploitation away from them and aligned them with the exploiters.

The fear of a servile insurrection alone was sufficient to make slaveowners court the favor of all other whites in a common contempt for persons of dark complexion. But as men tend to believe their own propaganda, Virginia’s ruling class, having proclaimed that all white men were superior to black, went on to offer their social (but white) inferiors a number of benefits previously denied them. To give the remaining white servants a better start in life, the assembly in 1705 required masters to provide servants, at the conclusion of their term, with ten bushels of Indian corn, thirty shillings in money, and “a well fixed musket or fuzee, of the value of twenty shillings, at least,” a somewhat more useful, if not more generous, provision than the three barrels of corn and suit of clothes previously required by “the custom of the country.” Women servants under the new act were to get fifteen bushels of corn and forty shillings in money. In addition, at the insistence of the English government, servants on becoming free were entitled to fifty acres of land, even though they had not paid for their own transportation.16

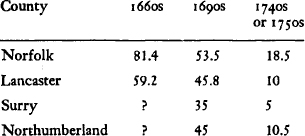

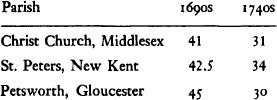

For men already free the assembly made what was probably its most welcome gesture by drastically reducing the poll tax. The annual levy paid by every free man in Virginia, for himself and his servants, was in three parts: public, county, and parish. The first and sharpest reduction came in the public levy, the amount collected for support of the colony government. From 1660 to 1686 the average annual public levy was 45 pounds of tobacco per person; from 1687 to 1700 it was 11 pounds; and from 1701 to 1750 it was 4.6 pounds.17 The reduction was made possible in part by the increase (as tobacco production rose) in revenue from the two-shilling-per-hogshead export duty on tobacco and in part by the income from new duties imposed on the importation of liquors, servants, and slaves. Parish and county levies did not drop as dramatically as the public levy; but they too were reduced, especially in years when the public revenues yielded a large enough surplus to pay the burgesses, a major expense that had hitherto been paid by county levies. As the tables below indicate, the total burden of direct taxes borne by a Virginian in the eighteenth century seldom amounted to half that paid by his counterpart in the seventeenth century.18 He may still have paid the difference indirectly through the customs duties, but he did not feel the pain as his forebears had.

As the small man’s economic position improved, he was also enjoying the benefits of a shift in social and political attitudes that coincided with the rise of slavery. The shift seems to have begun with the efforts of the crown, after Bacon’s Rebellion, to restrain the covetousness of Virginia’s provincial magnates. Those efforts, as we have seen, were largely unsuccessful and initiated a power struggle between the royal governors of Virginia and the assembly. After Effingham’s departure the struggle continued, as successive govemors strove to effect royal policies, many of them designed to benefit both the crown and the ordinary planter at the expense of the big men who continued to dominate the scene. But the 1690S saw a radical change in the character of the conflict. New personalities and new tactics on both sides combined with a crucial change in the intellectual climate to transform Virginia politics in unexpected ways. While the assembly was generating measures to align white men of every rank against colored men of every tint, and while magnates were tilting with governors, it became imperative for everyone who aimed at power to court the good will of the small freemen who made up the bulk of the voting population. The end result was to bring the small man, not into political office, but into a position that allowed him to affect politics as never before.

Average Annual Combined County and Public Levy in Four Counties in the 1660s, 1690s, and 1740s or 1750s

Average Annual Parish Levy in Three Parishes in the 1690s and 1740s

The change in intellectual climate originated in England. Effingham’s departure from Virginia coincided with England’s Revolution of 1688, when James II was deposed because of his attempts to magnify the executive power and William of Orange was invited to take his place. The result of that revolution, whatever else it did, was to shift the balance of power between king and Parliament in the direction of Parliament. The king did not become a cipher. William did not accept the throne in order to sink it. And the philosopher of the revolution, John Locke, who did not fancy legislative tyranny more than any other kind, recommended for the executive a strong and independent role in the government. But Locke made it clear to Englishmen that the legislature must be supreme and that the executive must be limited by the laws that the legislative branch enacted.19 In fact, the legislature had not only determined who should sit on the throne in 1688, but in 1701 it transferred the line of succession from the House of Stuart to the House of Hanover. Even affirmations of loyalty to King William or Queen Anne or King George could thus mean acknowledgment of the supremacy of Parliament, while Jacobitism, that is, loyalty to the Stuarts, meant rebellion against the lawful government.

The colonists readily gave their allegiance to the new king, presumably acquiescing thereby in the supremacy of Parliament over him. But Parliament made no attempt to exercise its new supremacy in America for many decades. English colonial policy after the Revolution of 1688, as before, emanated from the executive branch, and the precise relationship of the British legislature to the colonies was not defined. The primary impact of the revolution on England’s relations with her colonies was not in the mechanics of government but in the frame of mind it induced in the Englishmen who directed colonial policy.20 In the colonies, as we noted earlier, James II had attempted to tighten his hold by dismissing the representative assemblies of the northern colonies and consolidating them into a single province. During the revolution the colonists had tumbled this Dominion of New England, in which all powers were vested in the provincial executive, just as Englishmen had put an end to James’s efforts to magnify the power of the executive in England. When William became king, he could scarcely have attempted to repudiate the revolution by restoring the Dominion or by subordinating the colonial legislatures to the colonial executive powers, even though the governors were the conduit through which British control of the colonies still flowed. Moreover, in 1696, to bring some order into the direction of colonial affairs, William established the Board of Trade and appointed John Locke himself as one of the eight working members.21 The revolution thus created in both England and the colonies a psychological environment in which legislative powers held a presumptive advantage over executive prerogatives.

It was not at first clear how the change would affect the distribution of power in Virginia, for legislative and executive powers were mingled there, as in other colonies. The council not only advised and consented to the governor’s actions, including his vetoes of legislative measures, but also served as the upper house of the legislature and as the supreme court of the colony. For a governor to try to control his council, as all governors tried to do, might henceforth be interpreted as a sinister effort to subordinate the legislative to the executive power and to concentrate too much power in a single unchecked executive.

In this uncertain atmosphere there emerged on the political scene in Virginia a man who knew how to manipulate people and politics with a skill no previous Virginian had shown. James Blair had been a young Scottish clergyman in 1681 when, along with eighty others, he had refused to take an oath that would have acknowledged the Catholic James II, upon his accession, as head of the Scottish church. Blair was therefore ejected from his benefice and made his way to London, where he was befriended by Henry Compton, Bishop of London. In 1685 the bishop sent him to Virginia, recommended to the church of Varina Parish in Henrico County. Soon after establishing himself there, Blair displayed his prowess in social diplomacy. Virginia ministers did not rank high in the colony’s social scale, partly because of the insecurity of their position. Since they could be dismissed at the whim of their vestries, planters of large means were reluctant to match their daughters with them. Blair had no estate of his own, and it thus suggests something of his native ability that within two years he won the hand of Sarah Harrison, daughter of the biggest man in Surry County and one of the biggest in the colony, despite the fact that she was already pledged to another. The marriage placed him at once in the top circle of Virginia gentry, the only clergyman who had ever attained such a place.22

Blair’s superior, the Bishop of London, also recognized his talents and in 1689 appointed him as his commissary or agent in Virginia, with authority over the rest of the Virginia clergy. In this position Blair found that his efforts to raise the moral standards of his colleagues came to little, because the Virginia clergy at the time contained a high proportion of misfits, drunkards, and libertines who had come to the colonies because no parish in England would have them.23 Perceiving that this situation might be remedied by educating native Virginians, whose families and reputations would be known in advance, Blair proposed the establishment of a college, went to England to secure backing, got it, and returned in 1693 to found the College of William and Mary.

There can be no doubt of Blair’s abilities. His letters, written in support of whatever cause he argued, were always couched in convincing terms. And he generally got what he wanted, because he had the ability to make the most outrageous charges against his enemies seem plausible. His enemies included, successively, nearly every governor of Virginia for the fifty years that followed his return to the colony in 1693. That enmity, more than any other single factor, dictated the style of Virginia politics during those years.

Sir Edmund Andros, who became governor during Blair’s absence, was the first to tangle with him. Blair had been on good terms with Andros’ immediate predecessor, Francis Nicholson—probably because the two had had too brief a time to become acquainted—and he had carried to England Nicholson’s recommendation that a clergymen be appointed to the council. There was not much doubt about which clergyman was meant, and in 1694 Andros received instructions from the king to swear the Scotsman in as a councillor.24 By then Blair was already nettled because Andros was insufficiently zealous in support of the new college and of the clergy. Before long the council was treated to what the clerk recorded as “undecent reflections reiterated and asserted with passion by Mr. James Blair.”25 Andros responded by suspending Blair from the council. Blair wrote letters to England and was rewarded with an order from the king, restoring him to his seat.26 For the next year he sat in it and found some reason to quarrel with the governor at nearly every meeting. At the same time he was building a coalition of supporters and feeling out the weak points of his adversary.

It was not difficult to devise a line of attack. Sir Edmund Andros, a military man whose sympathies lay entirely on the side of royal prerogative as opposed to Parliamentary power, had been James II’s choice for governor of the Dominion of New England. He had angered the New Englanders by telling them that they had no more rights than slaves; and they had seized him and shipped him back to England when William took the throne. Although William had exonerated him and sent him to Virginia, he was nevertheless vulnerable, in the post-revolutionary atmosphere, to the charge of seeking excessive, arbitrary powers. In 1697 Blair took off for London again, ready with a convincing case against the governor. He not only enlisted the support of his patron, the Bishop of London, but went directly to the man who could speak most effectively against arbitrary government. Blair presented John Locke at the Board of Trade with a detailed criticism of the political structure that supplied Virginia’s governors with dangerous, uncontrollable, arbitrary powers, powers that Andros in particular, he said, had been all too ready to use.27

Not surprisingly, a conspicuous example of arbitrary power in Blair’s demonstration was the governor’s ability to suspend from office a councillor who displeased him. But Blair did not confine himself to personal grievances. He mapped out the avenues by which all the most lucrative offices in Virginia accrued to a few big men. The governor’s control of the council was almost absolute, as Blair put the case, because by his influence in the selection of the royally appointed councillors and his power of suspending them he could confer or deny access to the excessive rewards that lay open to the council.28 There may have been something of the dog in the manger about Blair, for as the bishop’s commissary he could scarcely have expected to hold many more offices beyond that of councillor. And those who supported him may have been moved by a feeling that they had not had a large enough share of the spoils. Nevertheless, whatever his motivation, Blair’s analysis was not without merit; and with the assistance of Locke and the bishop, he persuaded the Board of Trade to arrange for the recall of Andros and the reappointment of his own presumably reliable friend, ex-Governor Francis Nicholson. Included in Nicholson’s instructions, along with other provisions derived from Blair’s indictment, was a prohibition against councillors’ also holding office as collectors.29 Stripped of their largest fringe benefit, councillors would have less incentive to dance to whatever tune a governor called. Henceforth governors would have to win their support in other ways—or look for support elsewhere.

Although Blair was not at once appointed to Nicholson’s council, he probably expected to play the role of Richelieu in the new regime. And he was in an excellent position to manage it. The importance of family connections, which had never been negligible in Virginia politics, was magnified by the new independence of the council; and Blair had plenty of family. He had acquired a new set of political allies during his absence in England by the marriage of his wife’s sister to Philip Ludwell II, the son of the man who had outwitted so many previous governors. The younger Ludwell had already stepped into his father’s shoes, and the family had other marital connections that carried a heavy weight in politics. When Blair rejoined the council in 1701, his father-in-law, Benjamin Harrison II, was already a member, and Colonel Lewis Burwell of Gloucester, whose daughter was married to Benjamin Harrison III, was another member. So was Robert “King” Carter, whose daughter was married to Burwell’s son. In the following year, when Burwell retired from the council, Philip Ludwell II and William Bassett, another Burwell relative, were appointed.30 With this array of relatives beside him and with his consummate skill in manipulating people, Blair could count on a good deal of backing in any political dispute. And disputes were not long in coming, for Blair quickly began to see in Nicholson another Andros, an enemy of the college and of the clergy, and a tyrant in the making.

Nicholson, for his part, did not fancy Blair as an éminence grise in his administration. Nicholson had a forthright disposition and a violent temper that frequently crops up in the records. Like Andros he was a military man, with the military man’s assumption that people ought to do what he told them to. When Blair crossed him, he fought back hard and effectively, by tactics that Andros had not attempted. He tried to forge a marital alliance of his own with Lucy Burwell, daughter of the councillor, with whom he fell genuinely in love. When she spurned him, Nicholson blamed Blair and the whole Blair connection.31 Indeed, he apparently concluded that the first gentlemen of Virginia were all a parcel of rogues and that the councillors in particular “had got their estates by cheating the people,” an opinion that may have held more than a grain of truth.32 In this situation, with a hot-tempered governor tackling an alliance of Virginia’s top families, the small planters were drawn into the fray by both sides and emerged as a force in Virginia politics.

Since most of the evidence that survives about the battle was written by Blair and his friends, it must be treated with caution. As they described him, Nicholson was a would-be despot, grasping for power by means of a standing army recruited from the lowest ranks. Nicholson, according to Blair, proposed to “take all the servants as Cromwell took the apprentices of London into his army, and indeed he has upon many occasions to my knowledge preached up the doctrine that all the servants are kidnapped and have a good action against their masters.” Blair went on to claim that he had heard Nicholson say that once he had got “an army well fleshed in blood and accustomed to booty there would be no disbanding of them again if they were commanded by a man that understood his business….” And in case anyone missed the point, Blair added, “Several persons have told me they have heard him say Bacon was a fool and understood not his business.”33 A rebellion against the ruling Virginians conducted by the governor himself, and a governor experienced in arms, with a legitimate army at his back, would be formidable indeed.

Actually Nicholson may only have been trying to carry out instructions from the Board of Trade directing him to see that all planters and all Christian servants be armed in preparation for attacks by the French and Indians in the impending war. The House of Burgesses explained why it would be dangerous to arm Virginia’s servants, but Nicholson apparently kept trying, for the records show the council again demurring to the proposal two years later.34 According to Blair, the governor was bent on arming the servants in order to forward his own sinister purposes.

Blair’s suspicions of the governor seemed to be substantiated when Nicholson reorganized the militia so that it could better cope with the expected French attack. In order to build a more effective, disciplined force, he had the militia in every county select one-fifth of their number, “young, brisk, fit, and able,” to form elite companies.35 According to Blair, the men of these companies were not merely the “youngest and briskest” but also “the most indigent men of the Country,” and Nicholson allowed them to pick their own officers. “Now I could not but think with terror,” said Blair, “how quickly an indigent army under such indigent officers with the help of the Servants and Bankrupts and other men in uneasy and discontented circumstances (upon all which I have heard him reckon) so well arm’d and Countenanced by a shew of authority could make all the rest of Virginia submit.”36 When the governor held a giant festival at Williamsburg to celebrate the accession of Queen Anne, it looked like part of the same sinister strategy, for Nicholson brought his militia companies in for a free feast and as much liquor as they could hold—and this in June when industrious planters were busy with their crops.37

The question of, who should and should not be armed in Virginia was only one issue in the struggle between the governor and the council. Behind the accusations against Nicholson seems to have been the conviction of the councillors that he intended to bypass them and rest his regime directly on his popularity with the people at large. In a petition for his recall the council charged that he not only sought to gain “the good opinion of the Comon people but allso to beget in them such jealousies and distrusts of the Council, as might render them incapable to withstand his arbitrary designs.”38 Nicholson was apparently appealing to the small planters for help against the barons who threatened to best him as they bested Andros. If he could win the small planters, Nicholson might get into the assembly a set of burgesses who would consistently support him in issues that the council opposed. With governor and burgesses aligned together, the councillors might find themselves taking a back seat. To keep that from happening, they had to discredit Nicholson with both the voters in Virginia and the government in England. And James Blair had found the way.

In crying up the threat of Nicholson’s plans for an army, Blair had a point that would count strongly against the governor among the men in England who had supported the Revolution of 1688. John Locke’s patron, the Earl of Shaftesbury, had been one of the first to expound the dangers of a standing army; and he had done so in defense of the House of Lords, a body corresponding in part at least to the council in Virginia. A monarch, Shaftesbury had argued, who did not rule through his nobility, must rule through an army. “If you will not have one,” he told the peers in 1675, “you must have t’other.” Rule through the Lords meant liberty, rule through an army meant tyranny. Hence “Your Lordships and the People have the same cause, and the same Enemies.” The people must therefore recognize every attack on the Lords as a move toward military rule and tyranny. The argument was easily extended to include the House of Commons along with the House of Lords, and after 1688 opposition to a standing army became a hallmark of belief in the principles of the revolution.39

Thus Blair and his friends could win support in England by making it appear that Nicholson was seeking to subvert English liberty (that is, the supremacy of the legislative branch) both by debasing the council and by building an elite corps—a standing army. The two obviously went together. If Virginians were not yet sufficiently versed in the principles that made this diagnosis plausible in England, they needed no instruction in the dangers of arming the indigent. If Nicholson did indeed seek to arm not only the indigent but also the Christian servants, he was being singularly obtuse about the colony’s history and traditional psychology. And he had clearly overreached himself if he persisted (as the records seem to indicate) after the burgesses had explained their objections:

The Christian Servants in this Country for the most part consists of the Worser Sort of the people of Europe And since the Peace [of Ryswick, 1697] hath been concluded Such Numbers of Irish and other Nations have been brought in of which a great many have been Soldiers in the late Warrs That according to our present Circumstances we can hardly governe them and if they were fitted with Armes and had the Opertunity of meeting together by Musters We have just reason to feare they may rise upon us.40

Whether or not Nicholson actually did threaten the planters with arming the servants, Blair and the council tried their best to fan suspicions. They knew that the small planters feared a servile insurrection as much as the large planters did, because the Christian servants whom Nicholson was supposed to arm belonged mainly to the small planters, who could not afford slaves.41 And if Blair’s suggestive description of Nicholson’s “indigent army” under “indigent officers” brought to mind such men as the colony got rid of later by military expeditions—the shiftless, troublesome crowd of men traditionally feared by the rest of the population—then too the small planters as well as the large would feel uneasy about the new elite corps of militia. Nicholson’s appeal to the common people for support would be demolished if his opponents could establish the idea that the governor wanted to rule them through his indigent army. Blair tried to get the idea across. He reported that Nicholson proposed to “Govern the Country without assemblies.” The governor, said Blair, gave his opinion of English liberties with the expression, “Magna Charta, Magna F——a,” and threatened to hang his opponents with Magna Charta about their necks.42

It was an accusation to shock Englishmen, but at the time it was probably more effective in England than in Virginia. A governor who courted the indigent masses was distinctly out of step with post-revolutionary thought and post-revolutionary politics in England, where the legislature was the center of power and legislators and the property owners who elected them were the men to court. If it could be shown that Nicholson’s tactics had alienated the assembly, it would be prima facie evidence that he was unfit to govern. And in 1702 the assembly gave signs of alienation. When Nicholson, on orders from the king, asked the burgesses for money to assist New York against French invasion, they refused to comply. In England the refusal seemed to confirm the charges against the governor.43

One anonymous English friend chided him on his imprudence and suggested a more suitable strategy. It would not do, the writer said, to “speak so much of the Prerogative and so little of the law, and in truth the course must be steered now very evenly between Prerogative and Property, and with a due respect to the latter as well as the former, or our English Parliaments, such sure is the universal disposition of the nation, will vent their indignation.” It was said, he heard, “that by your rough and Naballike Treatment of both Councill and Assemblies you have lost all interest in them, and that this has already appeared in that you could not get them to comply with the instructions about New York.” And the writer went on to censure his friend for gathering so many common people in the extravagant celebration at Williamsburg, where one witness declared that “he saw 500 drunk for one sober.” The common people, the writer advised, “are never more innocent and usefull than when asunder, and when assembled in a mob are wicked and mad.”44

With the way prepared by letters detailing Nicholson’s reckless appeal to the mob, Blair sailed for England in 1703, and by the spring of 1705 he had secured the governor’s recall, just as he secured the recall of Andros seven years earlier.

It is not impossible that some of Blair’s charges against Nicholson were valid. Nicholson’s bluff manner, his violent temper, and his military cast of mind lent substance to them. But there was probably some justice also in the comment of one of the governor’s friends that Blair and his crowd were simply disgruntled by the governor’s refusal to let them run the colony as they chose. When he would not, “they Left no stone unturned to perplex the affaires of Government, setting up for Liberty and property men but ware soone discovered.”45 “Liberty and property men” in contemporary political parlance meant champions of legislative supremacy, and on that, their own chosen ground, Nicholson proved able to best his opponents—at least in Virginia. Frustrated in the council by Blair, he had turned to the burgesses and competed with the council to influence elections to the House. In the election of 1703 he seems to have outdone them in lining up votes, for the burgesses elected that year for the most part supported him against the council in subsequent sessions. He was even able to get from them in the session of 1705 a resolution denying the allegations of the council against him. But his vindication came too late to save him from Blair’s persuasive talents in England.46

It seems unlikely that the burgesses and voters would have backed the governor if they actually thought he had curried favor with the despised and feared part of the population. Although men in England may have believed the councillors’ accusation, Virginians apparently knew better. Nicholson’s success with the burgesses argues that his appeal was not to the shiftless and shifting indigents of Virginia but to small planters, men who expressed through their votes their satisfaction with a governor who was willing to court them instead of their lordly neighbors. Under Nicholson a new excitement had appeared in elections to the House of Burgesses. The governor had injected a new element into the political game. The ordinary planters had begun to sense their importance. If huge holdings of land were concentrated in the hands of a few, and if the colony still had a portion of landless rovers, there was still enough land to give the majority of men a little, enough to enable them to vote. Suddenly they found that their votes mattered. The men who wished to rule Virginia could no longer do it without heed for them.

After Nicholson’s departure and the death (within a year) of his successor, the council was able for a time to resume its dominance of the government, but Nicholson’s struggle for the support of the assembly was a lesson not lost on Blair and his friends: control of Virginia would ultimately depend on control of the House of Burgesses. Not that the burgesses had been a negligible factor till now. The Ludwells and Beverleys had used them effectively on many occasions, as we have seen, in thwarting a Jeffreys or an Effingham. But henceforth it might be necessary to go beyond the burgesses to the voters who put them in office. Elections would have to be managed to see that the right people got in.

That a change was coming over Virginia politics was apparent as early as 1699, when the first assembly under Nicholson passed a law forbidding candidates to do what they had probably just been doing, to “give, present or allow, to any person or persons haveing voice or vote in such election any money, meat, drink or provision, or make any present, gift, reward, or entertainment … in order to procure the vote or votes of such person or persons for his or their election to be a burgess or burgesses.”47 It is, of course, no sign of democracy when candidates buy votes, whether with liquor, gold, or promises. But when people’s votes are sought and bought, it is at least a sign that they matter.

They had probably begun to matter before Nicholson started his contest with the council for their votes. Before the end of the seventeenth century there were more big men than the council or the House of Burgesses had room for, and the law against treating suggests that the voters were already being courted by rival aspirants to public office. That in itself should have given them ideas. When the king’s governor himself contended with local magnates for their votes, the small planters could scarcely fail to feel their stature rising. And they were reminded of it at every election. In spite of the law, which remained on the books throughout the colonial period, candidates continued to “swill the planters with bumbo” in hot pursuit of their votes. The election contests meant more than a few free drinks for the small planter. They sharpened his political intelligence and placed him closer than ever before to the seats of power.

The small man’s new position was exhibited (and exaggerated) in the laments of the royal governor who succeeded Nicholson and continued to challenge the Virginia barons for control of the colony. Alexander Spotswood, another British military officer, who held the governor’s chair from 1710 to 1723 (when James Blair again made a successful trip to England), had instructions that would have brought benefits to the small man, if successfully carried out, for they would have eliminated the accumulation of land by men who had no intention of cultivating it themselves. He was to see that all land grants required the owner of a tract to cultivate three acres for every fifty in it. Failure would result in its reversion to the crown.48 Spotswood assumed that his principal opposition would come from the powerful gentlemen who sat on the council and who had been busy gobbling up land. He was not entirely mistaken, for he later found that Blair had a majority of the members in his camp, and any effort to change the situation was blocked by a clause in his instructions that required the consent of a majority of the council for dismissal of a member.49 But Spotswood’s greatest difficulty came from the burgesses. To his dismay, he discovered at the first election after his arrival “a new and unaccountable humour which hath obtained in several Countys of excluding the Gentlemen from being Burgesses, and choosing only persons of mean figure and character.”50

Spotswood was right about the new humor of the voters but probably not about the quality of the men they elected. The new burgesses were, as usual, an affluent lot of landowners looking out for their own interests.51 But they were also men who knew how to please the men who elected them.52 It was a time of low tobacco prices, and as the burgesses gauged public opinion, taxes concerned the voters more than land. Accordingly these tribunes of the people could safely agree to a long and complicated law that seemed to comply with the governor’s instructions (but which put all existing grants beyond question, no matter what errors might have been committed in the surveying and patenting of them). But when he asked for money to raise troops against another impending French and Indian attack, they declined.53 Spotswood blamed his failures on the ignorance and plebeian character of the assemblymen, who strove “to recommend themselves to the populace upon a received opinion among them, that he is the best Patriot that most violently opposes all Overtures for raising money.”54 At the next election in 1712 the new turn in politics was even more evident. “The Mob of this Country,” wrote Spotswood, “finding themselves able to carry whom they please, have generally chosen representatives of their own Class, who as their principal Recommendation have declared their resolution to raise no Tax on the people, let the occasion be what it will.”55

Although Spotswood underestimated the social quality of the men elected, he was not mistaken about the tenor of their politics. And he was ready with a solution. The trouble came, he believed, from “a defect in the Constitution, which allows to every one, tho’ but just out of the Condition of a Servant, and that can but purchase half an acre of Land, an equal Vote with the Men of the best Estate in the Country.”56 As long as this situation prevailed, he was sure, “the meaner sort of People will ever carry the Elections, and the humour generally runs to choose such men as are their most familiar Companions, who very eagerly seek to be Burgesses merely for the lucre of the Salary, and who, for fear of not being chosen again, dare in Assembly do nothing that may be disrelished out of the House by the Comon People.”57 But when Spotswood proposed to the men of best estate, sitting on the council, that they remedy the evil by raising the qualifications for voting, some discreetly thought it was not a proper time for such a move, and others frankly declared themselves satisfied with the situation.58

When Spotswood tried to outwit the “vulgar mob” by tampering with their representatives after the election, he in effect cut himself out of the political game. In 1713 he inveigled the burgesses into passing a measure that was unpopular with the small planter. The act provided for tobacco inspection and the destruction of tobacco that did not meet standards, and it created forty inspectors who were to receive fees that were estimated at £250 annually.59 Twenty-five burgesses were rewarded with these plums, and Spotswood had already found other government offices for four more. A majority of the burgesses were thus in his debt, and during the rest of the session the measures he proposed went through easily.60 But populist politics were already too strongly entrenched to be defeated by such crude tactics.

Queen Anne died in 1714, and the accession of a new monarch required new elections. The Virginia councillors, perceiving Spotswood’s vulnerability with the people, campaigned for candidates who opposed him and the “court party” they accused him of forming. The result was not even close. Only seventeen members of the former House were reelected, and only two of them had accepted inspectorships.61 It was nearly a clean sweep of Spotswood’s supporters, a conclusive victory for the vulgar mob and for the councillors who had busied themselves in the campaign. Spotswood later complained that he had been “branded by Mr. Ludwell and his Adherents (who set themselves up for Patriots of the People,) for endeavouring to oppress the people by extending the Prerogative of the Crown.”62 But Spotswood and every other governor who tried to carry out British policy lent validity to the charge by wrapping themselves in the royal prerogative when challenging actions of the legislature. Prerogative after 1688 was a dubious weapon. For a dozen years Spotswood used it to no avail in the effort to free his administration from the grip that the Blairs, Burwells, and Ludwells held on Virginia politics. In 1722 he finally gave up trying to carry out his instructions from England and joined his opponents. It was too late to retrieve his career as governor, for they had already succeeded in arranging his recall. But before he left office he made up for lost opportunities by cultivating the men who had opposed him and by sealing their friendship in a flood of huge land grants in the west for them and for himself.63 The requirement for cultivating three acres out of fifty was quietly ignored.

It will be evident, in spite of Spotswood’s accusations, that the new politics did not really constitute a surrender to the mob but a new triumph for the men who had dominated Virginia from the beginning. Some of the measures that Spotswood sponsored, on instruction from England, were designed to clip the wings of the Virginia barons and to favor the small man. But the burgesses would have none of them. In every popular contest Spotswood lost. How, then, did Virginia gentlemen persuade the voters to return the right kind of people to the House of Burgesses? How could patricians win in populist politics? The question can lead us again to the paradox which has underlain our story, the union of freedom and slavery in Virginia and America.

1 Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1695–1702, 158.

2 H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1702/3–1705, 170501706, 1710–1712 (Richmond, 1912), 270.

3 Waverly K. Winfree, The Laws of Virginia: Being a Supplement to Hening’s The Statutes at Large, 1700–1750 (Richmond, 1971), 253; Hening, IV, 208–14; VI, 29–33; Howard Mackey, “The Operation of the English Old Poor Law in Colonial Virginia,” VMHB, LXXIII (1965), 29–40.

4 Winfree, Laws of Virginia, 217–22; Jones, Present State of Virginia, 87, 210–12; Smith, Colonists in Bondage, 119–21.

5 Smith, Colonists in Bondage, 116–17, 311, 325. Given the severity of English penal laws, it seems likely that many were not habitual criminals.

6 VMHB, XXXVI (1928), 216–17; WMQ, 1st ser., XV (1907), 224; Jones, Present State of Virginia, 87, 210–12; Fairfax Harrison, “When the Convicts Came,” VMHB, XXX (1922), 250–60; John W. Shy, “A New Look at Colonial Militia,” WMQ, 3rd ser., XX (1963), 175–85. Another recourse was the royal navy. When warships in Virginia waters needed seamen, the council authorized the captains to impress “vagrant and idle persons and such as have no visible Estate nor Imployment.” Executive Journals, III, 213, 215 (1709), 531 (1720). See also ibid., I, 49.

7 R. A. Brock, ed., The Official Records of Robert Dinwiddie, Virginia Historical Society, Collections, n.s., III and IV (Richmond, 1883–84), I, 92.

8 Hening, V, 95, 96; VI, 438–39; Executive Journals, III, 213, 531.

9 Mackey, “Operation of the English Old Poor Law,” 30.

10 The figures are drawn from miscellaneous lists and records of tithables in the Virginia State Library and from Tyler’s Quarterly Historical and Genealogical Magazine, VII (1926), 179–85. The counties are listed roughly from north to south. The decline in the number of one-man households may have resulted not only from the decrease in the annual numbers of new freedmen but also from an increase in native-born children over fifteen who remained with their parents on family farms. But native-born sons reaching adulthood and setting up on their own would also be responsible for many of the one-man households. And sons of small planters would probably have started from a somewhat more secure economic base than newly freed servants.

11 D. Alan Williams, “The Small Farmer in Eighteenth-Century Virginia Politics,” Agricultural History, XLIII (1969), 91–101.

12 James W. Deen, Jr., “Patterns of Testation: Four Tidewater Counties in Colonial Virginia,” American Journal of Legal History, XVI (1972), 154–76.

13 Aubrey C. Land, “The Tobacco Staple and the Planter’s Problems: Technology, Labor, and Crops,” Agricultural History, XLIII (1969), 69–81, esp. 78–79. In 1766 John Wayles noted that in the preceding twenty-five years, “many Estates have increased more than tenfold.” J. M. Hemphill, ed., “John Wayles Rates his Neighbours,” VMHB, LXVI (1958), 302–6.

14 Aubrey C. Land, “Economic Base and Social Structure: The Northern Chesapeake in the Eighteenth Century,” Journal of Economic History, XXV (1965), 639–54; “Economic Behavior in a Planting Society: The Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake,” Journal of Southern History, XXXIII (1967), 469–85, esp. 472–73; Brown and Brown, Virginia, 1705–1786, 32–62.

15 Jacob M. Price, “The Economic Growth of the Chesapeake and the European Market, 1697–1775,” Journal of Economic History, XXIV (1964), 496–511; Price, France and the Chesapeake: A History of the French Tobacco Monopoly, 1674–1791, and of Its Relationships to the British and American Tobacco Trades (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1973), I, 266; Brown and Brown, Virginia, 1705–1786, 7–31.

16 Hening, III, 304, 451. The value of freedom clothes had probably amounted in most cases to somewhat less than the 40 shillings equivalent thus required, though the Norfolk County court in 1657 awarded 250 pounds of tobacco as a substitute for freedom clothes. Norfolk IV, 110. In similar cases the Northampton court in 1651 awarded 200 pounds in lieu of freedom clothes and in 1672, when the price of tobacco was down to a penny a pound or less, 400 pounds, and in 1675, 450 pounds in lieu of both corn and clothes. Northampton IV, 160a; X, 166; XII, 47. A York inventory of 1648 valued ten servants’ suits at 1,000 pounds. York II, 390.

17 Figures derived from Norfolk IV and VI; Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1659/60–1963; Hening, II–VI; Winfree, Laws of Virginia.

18 Figures for county and public levies derived from Norfolk IV, VI, XI–XIV; Lancaster III, IV, VI, VII, XI, XII; Surry IV, V, VIII–X; Northumberland XIII, XIV; figures for parish levies from C. G. Chamberlayne, ed., The Vestry Book of Christ Church Parish, Middlesex County, Virginia, 1663–1767 (Richmond, 1927); The Vestry Book and Register of St. Peter’s Parish, New Kent and James City Counties, Virginia, 1684–1786 (Richmond, 1937); The Vestry Book of Petsworth Parish, Gloucester County, Virginia (Richmond, 1933). George Mason in 1753 estimated that the total of public, county, and parish levies, one year with another, did not amount to more than eight shillings sterling per poll. Robert A. Rutland, ed., The Papers of George Mason, 1725–1792 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1970), I, 29.

19 John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, Peter Laslett, ed., (Cambridge, 1964), 375–87.

20 The best study of the effects of the Revolution in the colonies is Lovejoy, The Glorious Revolution in America.

21 Peter Laslett, “John Locke, the Great Recoinage, and the Origins of the Board of Trade: 1695–1698,” WMQ, 3rd ser., XIV (1957), 370–402.

22 Parke Rouse, Jr., James Blair of Virginia (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1971), 3–44.

23 William S. Perry, ed., Historical Collections Relating to the American Colonial Church. Vol. 1: Virginia (Hartford 1870), 30, 38.

24 Rouse, Blair, 83; Executive Journals, I, 315.

25 Ibid., I, 324.

26 Ibid., I, 352.

27 Some preliminary drafts and documents prepared by Blair are in Ms. Locke e 9 in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. One of these is printed in Michael Kammen, ed., “Virginia at the Close of the Seventeenth Century: An Appraisal by James Blair and John Locke,” VMHB, LXXIV (1966), 141–69. A larger version, emended by Henry Hartwell (another disgruntled councillor) and Edward Chilton (formerly clerk of the council), was published as The Present State of Virginia and the College, cited several times above.

28 In one of the documents in Ms. Locke e 9, Blair put the case more succinctly than in the published versions: “Sir: If you wud know how many places in Virginia are held by the same men, it is but proposeing the following Questions to anyone who knows the Country.

1. What are tne names of the present Council of Virginia?

2. Who make the house of peers in Virginia?

3. Who are the Lords Lieutenants of the severall Counties in Virginia?

4. Who are the Judges of the Court of Common Pleas?

Who are the Judges in Chancery?

Who are the Judges of the Court of Kings Bench?

And soe for Exchequer Admiralty Spirituality.

5. Who are the Naval Officers in Virginia?

6. Who are the Collectors of the Revenue?

7. Who sell the Kings Quitrents?

8. Who buy the Kings Quitrents?

9. Who is Secretary of Virginia?

10.Who is Auditor of Virginia?

11.Who are the Escheators in Virginia?”

29 VMHB, IV (1896–97), 52; Executive Journals, I, 440. The wording of the instructions is not altogether clear on this point, but the words were interpreted, and apparently intended, to convey such a prohibition.

30 Ibid., II, 274; Rouse, Blair, 133, 267–68.

31 Ibid., 135; Perry, Historical Collections, I, 102.

32 Charges against Nicholson brought by members of the council, VHMB, III (1895–96), 373-–82, esp. 376; Perry, Historical Collections, I, 98.

33 Perry, Historical Collections, I, 107, 109–10.

34 Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1695–1702, 188; Executive Journals, II, 184.

35 Ibid., II, 174.

36 Perry, Historical Collections, I, III.

37 Ibid., 71.

38 VMHB, III (1895–96), 377.

39 J. G. A. Pocock, “Machiavelli, Harrington, and English Political Ideologies in the Eighteenth Century,” WMQ, 3rd. ser., XXII (1965), 549–83, esp. 558.

40 Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1695–1702, 188.

41 Ibid.

42 Perry, Historical Collections, I, 106, 109.

43 Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1695–1702, 245–46, 259–60, 313–16; Perry, Historical Collections, I, 70–71.

44 Ibid.

45 Robert Quary to William Blathwayt, Sept. 2, 1702. Alderman Library, Charlottesville.

46 Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1702–1712, 107–8. D. Alan Williams, “Political Alignments in Colonial Virginia Politics, 1698–1750” (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University, 1959), 48–76. This excellent dissertation is the most perceptive study of Virginia politics during these years. Many of the documents in the dispute between Nicholson and Blair have been printed in VMHB, VIII (1900–1901), 46–64, 126–46, 260–78, 366–85, and in Perry, Historical Collections, I, passim. They demonstrate that Nicholson’s following in Virginia was not inconsiderable, even among the clergy.

47 Hening, III, 173.

48 Leonard W. Labaree, ed., Royal Instructions to British Colonial Governors, 1670–1776 (New York, 1935), I, 589–90.

49 Ibid., I, 60; Spotswood, Official Letters, II, 154–55; Williams, “Political Alignments,” 171; Rouse, Blair, 194–97. On the council’s attitude to the instructions on land see Executive Journals III, 194–95, 221.

50 Spotswood, Official Letters, I, 19. On the growth in power of the House of Burgesses during and after Spotswood’s time see Jack P. Greene, The Quest for Power: The Lower Houses of Assembly in the Southern Royal Colonies, 1689–1776 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1963).

51 Williams, “Political Alignments,” 126–27.

52 Cf. John C. Rainbolt, “The Alteration in the Relationship between Leadership and Constituents in Virginia, 1660 to 1720,” WMQ 3rd ser., XXVII (1970), 411–34.

53 Hening, III, 517–35; IV, 37–42; Williams, “Political Alignments,” 129–30, 144–45; Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1702–1712, 340–49.

54 Spotswood, Official Letters, I, 140.

55 1bid., II, 1–2.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid., 11, 124.

58 Executive Journals, III, 392.

59 Winfree, Laws of Virginia, 75–90; Williams, “Political Alignments,” 142–44; Spotswood, Official Letters, II, 49.

60 Williams, “Political Alignments,” 149–58.

61 Ibid., 159–63.

62 Spotswood, Official Letters, II, 152.

63 Executive Journals, III, 538–41, 546–48, 551.