The Return of the Lion Man

In late August 1939 archaeological excavations of a cave in southern Germany, conducted under the auspices of Heinrich Himmler’s SS Ahnenerbe (Ancestral Heritage Institute), were abruptly terminated by the impending outbreak of the Second World War. Several important discoveries had been made there and the Reichsführer-SS had been due to visit the site in person, before his attention was diverted by preparations for the invasion of Poland. On the very last day of the dig, some carved fragments of mammoth ivory were discovered, prompting SS-Sturmbannführer Robert Wetzel, a professor of anatomy in charge of the dig, to write to SS headquarters in Berlin stating that a “significant discovery” had been made. For reasons that remain mysterious, however, several decades were to elapse before the true significance of this discovery was established.

Following the collapse of Nazi Germany, Wetzel’s findings found their way into the museum at Ulm, a city on the Danube (and birthplace of Einstein) ten miles upstream from the cave, where they languished unnoticed until 1969, when an inventory inspection conducted by young archaeologist Joachim Hahn uncovered a box containing the fragments of mammoth ivory that had struck Wetzel as significant. Together with a couple of students, Hahn eagerly threw himself into a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle and swiftly assembled an extraordinary, upright, two-legged carved figurine with both human and animal characteristics.

Hahn was apparently hip enough to have read the avant-garde writer William Burroughs, for he named the headless figure “der Mugwump,” after the grotesque creatures Burroughs introduced in his deranged cult novel The Naked Lunch.1 Such reading matter reveals just how different a kettle of fish the bearded, pipe-smoking Hahn was to the Nazi ideologue Wetzel, indicating the extraordinary cultural shift that had taken place in post-war Germany in the space of just one generation.

The mugwump was an archaeological sensation, but proved to be merely the start of a reconstruction process that was to last another forty-four years. Several further digs at the cave, not all of them fruitful, produced another seven hundred mostly tiny fragments, and the conclusive assembly completed at the end of 2013 revealed a standing figure, just over a foot tall, of what appears to be a human with a lion’s head, reliably dated as 40,000–43,000 years old, making it the oldest work of figurative art ever discovered anywhere in the world. Let’s pause for a second to consider just how old that is in human terms. That’s twenty times older than Jesus, ten times older than Stonehenge and the Great Pyramid of Giza, and seven times older than the earliest urban civilization in ancient Sumer.

The figurine’s antiquity and the astonishing level of artistry it displays have led many academics to suggest that the Lion Man represents the peak cultural moment in human history: the arrival of the modern mind. Ecce Homo!

What the Lion Man may have meant to its maker is an extraordinarily rich question, but we can safely assume that it had something to do with magic; indeed, various key magical ideas are directly associated with it. Writers often trot out the line that magic is as old as mankind, and if the Lion Man represents the dawn of us as we know us, then it may well be true. So, given his cultural status and the fact that so few people have even heard of him, let’s take a close look at the old thing and see what it can tell us about the way we were relating to everything at the dawn of Homo sapiens as a magician.

Who Made the Lion Man?

The great quantity and variety of similarly ancient artefacts found in the vicinity of the Lion Man, including bone flutes and beautiful animal figurines, provide a context that allows us to build an incomplete but reasonably detailed picture of the kind of lifestyle experienced by its makers. The tools and techniques employed by these people provide archaeologists with the means to define their culture, which they have dubbed “Aurignacian,” after a site at Aurignac in southwest France.

As our understanding of deep history in Europe circa 40,000 BP 2 develops, the term Aurignacian will probably become defunct, but for now it identifies modern humans of the period, who first appeared in eastern Europe and gradually moved westwards along the course of the River Danube and beyond. They were hunter-gatherers identified by their advanced tool-making and highly sophisticated figurative art. Their range extended throughout almost all of sub-glacial Europe and appears to have remained culturally consistent in many respects over a period of 15,000–20,000 years.3 Their numbers seem to have been very small. Indeed, when I met archaeologist Dr. Rob Dinnis on a dig at Kent’s Cavern in Southwest England, where the oldest modern human remains in Northern Europe have been found 4 (dated, like the Lion Man, to circa 40,000 BP), he told me that the human population of Britain—at least the part not buried under hundreds of feet of ice—may have numbered no more than forty at the time. They seem to have ranged far and wide, maintaining contact with other groups, and the Lion Man may have made such journeys with them. Some experts believe that the rapid breakthroughs in tool-making technology, after many thousands of years without progress, indicate the appearance of complex and abstract language. Certainly we see the appearance of complex and abstract art, which can only have been created by a brain as modern and developed as those of humans today.

Anatomy

The anatomy of the Lion Man is very curious. The head is certainly leonine, the body is long like a lion’s, and the limbs are lion-like, with extremities more like paws than hands. The limbs are articulated like a human’s, though, and the creature is standing (or lying) like a human.

The anatomy of the Lion Man allows us not just to recognise its blending of human and leonine characteristics, however, but also to discern precise features that may be suggestive of both its bearing and its function. The figure appears at first glance to be standing, but the configuration of the feet, although less carefully carved and/or incomplete, has led some to suggest that the figure is standing on its toes, levitating, or even in flight, but it is also possible that it is floating or lying on its back. A recent academic paper 5 pays close attention to the very precise carving of the ears, which shows that the carver had a clear understanding of how the muscles of a lion’s ear work, allowing him or her to indicate that the Lion Man is listening attentively.

No such study has yet been made of the Lion Man’s mouth, but if we are allowed to assume that it was carved with the same degree of purpose and accuracy as the ears, then we must conclude that the carving of the upper lip as continuous, like a human’s, rather than split like a lion’s, is both deliberate and suggestive. The mouth is slightly open with one corner cast slightly down and the other slightly up. This not only confers a sense of personality, but it also suggests that the Lion Man is not just listening; it is also talking. What can it tell us?

The Meaning of the Lion Man

What is the Lion Man? Is it simply an extraordinary and powerful piece of art conjured from an individual imagination, or does it have a profound cultural significance shared by the whole tribal group? If so, what did the Lion Man mean to its people? Does it represent a god, a hunting totem, a talking stick, a being encountered in the spirit world, or something else entirely? The search for answers to this enormous question must necessarily be speculative, particularly since our knowledge of human culture at such a vast historical remove is so sparse.

We can thank archaeology for the discovery and reassemblage of the thousand-plus pieces of mammoth ivory to which time had reduced the figurine. The astonishing development of various scientific dating techniques has allowed the accurate dating of the piece to circa 41,000 BC, effectively more than doubling the age that archaeologists might reasonably have guessed at when it was first discovered in 1939. Another far smaller lion-man figure, also carved from mammoth ivory and of similar antiquity, was discovered in another cave in the same region, which is certainly suggestive of a profound cultural significance associated with lions.

Does the Lion Man’s talking mouth suggest that its makers invested it with oracular powers? If the Lion Man was used as an oracle, either directly or through the mediation of a shamanistic medium, to help its makers make important decisions, it would certainly have played a very significant role in the life of its people. Analysis of the ivory fragments that make up the Lion Man indicates that the figurine was much handled over its lifetime, lending weight to the idea that it might have been used as a talking stick, such as are still used by traditional aboriginal tribes and even taken up by the Boy Scouts movement in the twentieth century. Talking sticks represent tribal democracy, allowing whoever is holding the stick to state their opinion on matters of shared concern. A talking stick that has been used for generations bears witness to tribal history, and Lion Man’s maker may have spent many of the hundreds of hours that it took to carve it relating the tribe’s history and ideas to the emerging totem. From a shamanic perspective, the Lion Man would thus resonate the tribe’s entire wisdom tradition, affording it oracular powers that could be tuned into in prayerful, contemplative, or shamanic trance states.

Gender Blender?

Prior to the dating of the Lion Man, some of the oldest known figurative works of art were the so-called Venus 6 figurines, one of which is the Venus of Hohle Fels, believed to be the oldest representation of the human form, which was discovered in a cave just a few miles further up the Danube valley from the Lion Man’s cave. Dated at 35–40,000 years old, it is a classic female fertility figure, squat and round with exaggerated hips, buttocks, and breasts. Also carved from mammoth ivory, instead of a head it has just a short, narrow stump with a hole bored in it, presumably so that it could be worn as a pendant. The figurine, and others like it found in Europe and Siberia, encouraged the idea, particularly popular with New Age feminists, that our ancestors lived in matriarchal tribal groups where Mother Earth, fertility, and child-bearing were honoured above all else and women ruled the roost. The arrival of the almost phallic-shaped Lion Man threatened to undermine the matriarchal myth, and the figurine’s gender was hotly disputed, with the lack of mane, prominence of the belly button and the triangular pudendum claimed as suggestive of femininity. Indeed, from the 1980s until just a few years ago, the figurine became something of a feminist icon, triumphantly renamed the Lion Lady. It was then established that male European cave lions lacked distinctive manes, and the discovery of more fragments and the figurine’s final reassembly in 2012 and 2013 seem to have settled the dispute in favour of a masculine sex, although it may be that a certain androgyny was intended by its maker.

I recently stumbled across an ancient leonine deity that sheds a very interesting light on the Lion Man. Originally depicted as a lion standing upright, he is an apotropaion (protective totem) called Bez 7 and he is the guardian angel/demon of all things connected with maternity—pregnant women, fertility, suckling infants, and the home. His job is to protect the maternal home from all malign influences, including disease, evil spirits, and the “evil eye” (the projection of harmful thoughts by ill-wishers), the former usually agents of the latter. He first appeared nearly five thousand years ago in Old Kingdom Egypt, although some authorities think he may have originated elsewhere and possibly much earlier. Certainly, he appears to have no connection to the more familiar Egyptian pantheon that includes Isis, Set, Osiris, and Thoth. He gradually morphed from a standing lion to a dwarfish human figure wearing a lion skin, and sometimes a priapic ithyphallic figure similar to the Roman wine god Bacchus. He became increasingly associated with music, dance, and sexual pleasure and may even have been used as a sex toy. Essentially, he represents the honouring and protection of the feminine mysteries, particularly in relation to sex, fertility, and motherhood. He was also very much a domestic figure, kept in the house. There were no temples dedicated to him and he was never central to any form of hierarchical religion, but his popularity grew and he travelled (back?) into Europe and the Middle East. Intriguingly Bez is immortalized in the name of the Mediterranean island of Ibiza, synonymous to many with music, dance, and pleasure. It was named after him by Phoenician colonisers in 654 BC.8

It is possible that the Lion Man served the same functions, although maybe not exclusively, as Bez. The miniature Lion Man discovered in the Hohle Fels cave near to the Venus figurine was also apparently designed to be worn as a pendant. The Lion Man and Venus figurines were clearly used by the same tribe at the same point in history when the human population was very low—maybe around 30,000 in the whole of Western Europe. With no need to defend themselves against other tribes, except for the odd family spat, and with everyone in each tribal unit knowing each other intimately,9 only the most natural of hierarchies would have pertained. At this early point in our history we appear to have been honouring the masculine and feminine principles equally. One was begetter and protector, the other bearer and nurturer. We can but speculate on how sex was managed, but the only taboo vital to genetic fitness would have been incest. It is safe to assume, however, that the extraordinarily successful evolution of the species could not have been possible without a natural selection at play that instinctively avoided incest, probably on a biological level through the production of pheromones that attract those less closely related, while repelling near kin. At this stage of the game we are (mercifully) a long, long way from Freud …10 The irony is that the species’ reproductive success would eventually result in population increases that in turn would engender competition, division, and war, all of which tend to result in the marginalisation of women.

So if, like Bez, the Lion Man is a protective totem, what is he protecting the women from, if the men already see themselves as defenders of femininity? Well, one clue is in the figurine itself. The greatest threat to man’s emergence as the dominant species would have been that perfect predator, the King of the Beasts: the lion.

Animal Magic

Archaeologists and anthropologists agree that our Ice Age ancestors used magical techniques to improve their prowess as hunters. A common belief amongst hunter-gatherers is that by eating the flesh of an animal, they form a soul-bond with the species. This connection is enhanced by the ritual wearing of animal skins and jewellery made from teeth and bones. This kind of magic is called sympathetic magic, because it helps foster a sense of kinship between hunter and prey. By identifying with your prey, you can understand it more intimately, helping swing the odds of success in your favour. Cave paintings of prey animals and lions may have served a similar purpose.

Therianthropy

Depictions of beings that combine human and animal features are very rare in Ice Age art. The stunning Chauvet cave paintings discovered in southern France in 1994, also attributed to the Aurignacians, include a remarkable figure, the so-called “Venus and the Sorcerer,” which depicts the pubic area and thighs of a female human. One of the thighs also forms the front leg of a bison, but the bison figure was superimposed later and the image is less clearly a deliberate hybrid than the Lion Man.

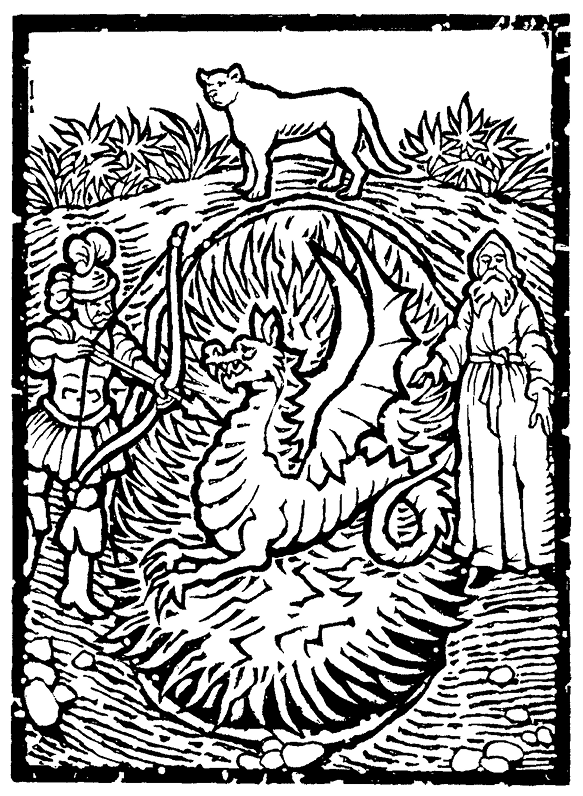

Figure 2: Venus and the Sorcerer art (left)

Figure 3: Sorcerer of Les Trois Frères (right)

The famous “Sorcerer of Les Trois Frères,” dated to around 15,000 BC, is a cave painting that appears to depict a man wearing the antlers and skin of an elk or deer, with an owl’s face and the tail of a fox or wolf. The reason why these two cave paintings are associated with sorcerers is that anthropologists have associated them with the magical art of shape-shifting. Shape-shifting into animal or hybrid form is known as therianthropy. Such abilities are traditionally attributed to shamans or “sorcerers” in various cultures around the world, particularly in Siberia, Africa, and the Americas. European folklore preserves the memory of such traditions in therianthropic tales of werewolves and witches’ familiars. Some of our great wizards were believed to have the ability to shape-shift. Merlin is supposed to have been able to turn himself into the fierce little falcon that bears his name, while the great Renaissance wizard Cornelius Agrippa had a great black dog that could act as its master’s doppelganger.

Meetings with Remarkable Insects

My own experiences of shape-shifting extend beyond the occasional hallucinatory sensation of assuming another form. While travelling in South America in 1988 I met a curandero 11 called Valentino in Otavalo, Ecuador, who assured me that he could cure the recently diagnosed arthritis in my right knee in a week. I was in continuous pain, and bearing in mind that the last thing my doctor had said to me before I left London was “keep taking the pills and when you get back we’ll see how long we can keep you out of a wheelchair for,” I figured that this might represent my only chance of avoiding premature disablement. Four days into the cure, Valentino, my girlfriend, Caddy, and I were sitting cross-legged on the king-size bed in our bamboo cabin in the high cloud forest, chanting jungle icaros.12 Feeling comfortably zorbed out, my attention fell on two bright green half-lozenge shapes on the cabin wall behind Valentino.

Just as I noticed that they were symmetrically arranged like a pair of eyes, they suddenly seemed to project a cold, malevolent intelligence that penetrated me to the core. As my chanting faltered, Caddy shuddered with disgust, her attention caught by a large dull-brown beetle scurrying on the blanket between us. She twitched the blanket and the beetle flipped over onto its back, revealing a metallic emerald belly carapace that was exactly the same size, shape, and colour as the two “eyes” on the wall. My first reaction was one of relief. Phew, they weren’t eyes after all, just beetles. Then I realised that if they had been beetles they would be holding onto the wall with their legs, exposing not their emerald bellies, only their dull-brown backs. My mind reeled and I looked beseechingly at Valentino. He was observing me curiously, but calmly said “grab the beetle, go to the door, throw the beetle out, and come back to the bed.” I immediately did exactly as he said and looked to him again, completely flabbergasted, but hoping he could shed some light on the anomaly. “Sometimes,” he said with a raised eyebrow, “a brujo 13 may choose to enter a space in the form of an insect, in order to disrupt the energy or simply to observe the scene.”

“Like a fly on the wall,” I said, a dawning sense of realisation allowing me to speak at last.

“Precisely so,” said Valentino. I hadn’t even mentioned the eyes.

Chavín de Huántar: The Lair of the Jaguar

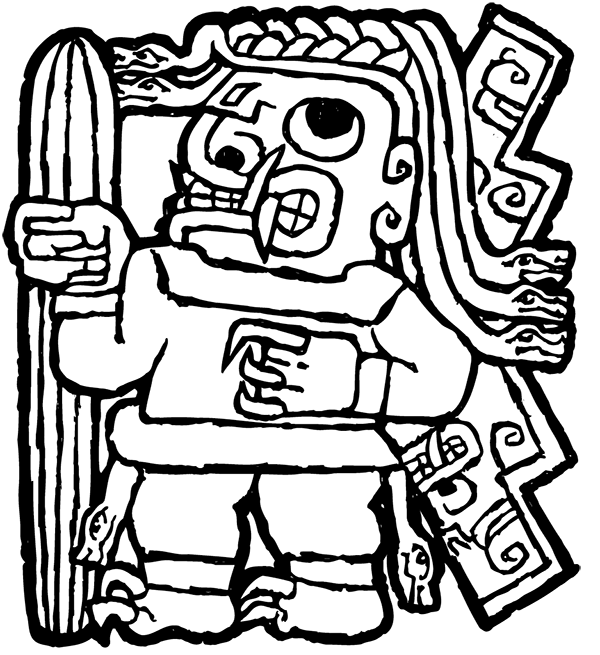

This incident helped make sense of another meeting with a remarkable insect I’d had just a few weeks earlier. We had visited Chavín de Huántar, a remarkable archaeological site 10,000 feet up in the Peruvian Andes, at the confluence of two tributaries of the mighty River Marañón, whose waters joined the Amazon, eventually spilling into the Atlantic Ocean thousands of miles to the east. Built out of blocks of pink granite and black sandstone, the three-thousand-year-old Old Temple houses within its labyrinthine, many-chambered interior a bizarrely carved granite megalith—the Lanzón—depicting a terrifying, highly stylized jaguar-man with snakes for hair. The exterior was studded with ghoulish gargoyles, some feline, some human, and as we arrived at the site in the company of two travelling companions, we were importuned by a couple of small boys trying to sell us little soapstone copies of the gargoyles.

I persuaded them instead to cut us some pieces of San Pedro, a ubiquitous hallucinogenic cactus that the ancient inhabitants appear to have revered, given the carved depictions of the plant on the walls of the complex.

The interior of the building was very cunningly constructed, with water channels tapped from the river, designed, it seems, to mimic the growling or roaring of a jaguar, the apex feline predator of the Americas and apparently the central deity of the Chavín civilization, which covered a good part of the coast-to-mountain area of Peru at the time of the biblical David and Solomon. The carving on the Lanzón is so stylized that I found it hard to visualize the entity it is supposed to represent, but a bas-relief (Figure 4) clearly represents the same entity: an anthropomorphic figure bristling with fangs, claws, and snakes, brandishing a dripping San Pedro cactus. Was it a shape-shifting jaguar shaman, a jaguar god, or death personified? No one knew for sure.

We emerged from the disorientating gloom of the Old Temple and there were the young hustlers waiting for us with four nice lengths of freshly cut San Pedro. We decided to head down to the coast to brew it up. The air was too cold and thin so high in the mountains and we were all feeling a bit queasy from siroche—altitude sickness. The rains had come in and we caught the last bus down to the coast, a terrifying experience at night down precipitous crumbling roads with two blatantly drunk drivers. Arriving safely, miraculously, in the warm morning sunshine of a little coastal town, we bought a large aluminium cooking pot and various other supplies and hitched a ride on a donkey cart up the narrow oasis hugging a river that was starting to swell with the mountain rains we had escaped.

The donkey cart dropped us off at the edge of a granite desert with a granite hill topped by the remains of what appeared to be a huge, crumbling granite fortress.14 We made camp under the shade of two great trees, whose heavily-leaved branches hung to the ground, forming a tent-like space around them. We made a fire, cut the San Pedro into thin slices, and started to brew it up in water. We boiled it for several hours, by which time night had fallen precipitously, plunging the outside world into blackness. Our travelling companions were a couple of surfers: John from Cornwall and Len, a full-blood Maori, who wore an ancient tribal whalebone pendant around his neck. John and Caddy decided to pass on the San Pedro, so Len and I embarked on our journey alone. The San Pedro soup had boiled down to a thin, slimy consistency and tasted unbelievably foul. We choked down as much of it as we could stand and waited. And waited. Caddy and John had fallen asleep. Nothing. Eventually we decided to have a look outside. We parted the curtain of branches and stepped out into a night of such total darkness that we couldn’t even see each other’s faces. We were amazed. No stars, no lights, no nothing; and none of the phosphene visuals that we were expecting from the San Pedro.

Suddenly we heard a sound close by that made us jump. It was a very low, challenging, guttural, masculine, animal-like noise. Alarmed, Len and I tried to identify the animal, if such it was. Horse? No. Donkey? No. Bull? No. Umm … jaguar? Suddenly we heard it again. This time the sound was right next to me and a hideous vision flashed like lightning in my mind.

“Shit, did you see that?” gasped Len.

“A crook-backed stick man with a square head, green lozenge eyes, and red fangs,” I blurted.

“Same!” squeaked Len. We clung to each other like Scoob and Shaggy. But then there was nothing, just the thick, breathy blackness.

A profound strangeness had settled on us though, and after a while, we each started perceiving shadowy figures going about some strange business, not as if they were there with us, but as if we were watching some ancient black-and-white film projected onto a screen by a light too pale to let us clearly make out the action. We each had an awful feeling of dread and the sense that the shadowy figures were bent on something evil. We were becoming convinced that the San Pedro was showing us what really went on inside the Old Temple at Chavín. The priests seemed to be using San Pedro to generate a state of such terror in their victims that they were able to steal their souls at the moment that they tore out their hearts and impaled them on the lozenge-shaped megalith in the Old Temple. A sacrificial terror torture cult! We had to stop comparing notes. It was too appalling.

We retreated back behind the curtain, stoked up the fire, and crawled into our sleeping bags. I prayed for sleep to rescue me from the ghastly horrors in my mind, but no such release came. All was hideous, pointless, soul-destroying horror. I could hear Len, tossing, turning, and groaning, but could offer him no comfort. In the midst of my despair I suddenly noticed a little light come in through the curtain on the other side of the fire, flashing gently. Flash-flash, flash-flash. A firefly. But it was blue! As I questioned its blueness, I was gently engulfed by a blue wave of the deepest, most comforting, redeeming bliss, lifting me out of the abyss of my despair and bearing me lovingly to the Land of Nod where good children are safe and sound forever. The last thing I knew was Len sighing with the same profoundly grateful relief.

We awoke at the same moment. Morning sun was shining through the curtains. John and Caddy were quietly busying about, making breakfast and brewing up coffee, oblivious of the horrors of the night. Len and I looked into each other’s eyes, both seeing a mixture of wonder, awe, and relief. All was well. “Did you see the blue firefly?” asked Len.

What was the blue firefly? I can only speculate. There is one species of blue firefly, the Blue Ghost (Phausis reticulata), but it is confined to the eastern and central United States and it just glows, but doesn’t flash. Twelve years later I encountered a little swarm of blue fireflies during an alchemy seminar with Manfred Junius in northern Bohemia, Czech Republic. It was in the walled garden of Roztěž Castle, former hunting lodge of the splendid Count Sporck, the founder of Czech Freemasonry. At dusk on a damp Summer Solstice evening I was looking for firewood to build a Solstice bonfire. I came through the rickety old door and suddenly there was a blue firefly a few yards away. I was amazed by its miraculously familiar flashing blueness, and suddenly there was a fantasy of them15 flitting and flashing just a couple of feet in front of me. They were the nearest thing to a traditional Victorian flower fairy that I have ever seen, although, in truth, that was more the way I felt them, as it was too dark to see anything of their bodies other than their amazing, gently flashing blue lights. I sensed a wonder and delight in them that touched me so deeply that I burst into tears on the spot. My memory is slightly hazy at this point, but I think that after maybe less than a minute they faded and disappeared. I went back to the lobby of the castle and asked the gate keeper, in German, about the fireflies. He said that fireflies only appear at the end of a long hot summer. This was late June after a cold, wet spring and dismal early summer, so I could not have seen any fireflies. As for blue ones! He laughed and looked at me as if I were stoned, deranged, or having him on. I was certainly neither the former nor the latter.

As for the crook-backed thing that had so spooked Len and me at Sechin Alto, who knows? When Caddy and I met Valentino in Ecuador a few weeks later, he was appalled that I could have been so foolish as to ingest such a powerful and unpredictable planta de poder (power plant) as San Pedro without a guide, particularly specimens gathered from Chavín de Huántar. We concluded my arthritis cure with a San Pedro session that was entirely different from my Chavín experience. Deep in the night, Valentino had fallen asleep in his hammock, tired of the Scottish folk songs that I was singing with clannish gusto. The candles on the altar sputtered and flared occasionally as small moths sacrificed themselves to the flames. I looked up at the rafter of the spacious hut and spotted the largest grasshopper I had ever seen. It was at least six inches long, with a head the size of a crab apple, and it gazed down on me balefully. I recalled the “fly-on-the-wall” incident a few days earlier, but I was feeling so strong and ecstatic that I didn’t feel at all spooked. I did, however, entertain the thought that it might be acting as the eyes and ears of some brujo, so I stared back at it and engaged it in psychic warfare. My technique was unsophisticated, but confident, and I found myself projecting that old English hooligan taunt: “If you think you’re hard enough!” I had to laugh, and at that moment the grasshopper hurled itself at the largest candle, bursting into flames and splashing hot wax all over the altar. The crackling and spitting were loud enough to waken Valentino, who roused himself in time to prevent his entire altar from going up in flames. Having brought everything under control, he gazed at me levelly and pronounced, “Now I see you are cured.” And I was. Nearly thirty years later I’m still not in a wheelchair and I have no problem with my right knee.

Cat People

My suspicion that the jaguar priests of Chavín were conducting a terror cult was sustained by what I later found out about the infamous Leopard Society of West Africa, who terrorized people into believing in the reality of shape-shifting were-leopards by dressing in leopard skins and murdering people with brutal false claws. This terrifying cannibal cult was not extirpated until the mid-twentieth century, and, so a firsthand witness has told me, survives in some aspects even to this day. Lion-man murders have also been committed. In 1948, three women and four men were executed for their part in the “lion-men murders” in the Singida district of Tanganyika. The perpetrators had dressed in lion skins and murdered more than forty natives in ritual slayings that left wounds on their victims resembling the marks of a lion’s claws.

My old friend Mike Jay, intrigued by my Chavín adventures, visited Chavín de Huántar himself a few years later. The piece he wrote, Enter the Jaguar,16 has been published in various journals and remains probably the best English language overview of what may really have been going on there. He convincingly demonstrates that Chavín de Huántar was probably the centre of a psychedelic initiatory cult using DMT, the most powerful plant psychedelic in the world, in addition to San Pedro. The chambers in the temple were for incubating those to be initiated, creating the kind of sensory deprivation which would have been an ideal prelude for the DMT-fuelled encounter with the Lanzón entity at the heart of the labyrinth. The sense of feline transformation under the influence of DMT remains a common element of South American DMT shamanism, and I can attest from my own recent experience that the manifestation can appear extremely real. Far from losing my soul, my belief in its existence was powerfully affirmed.

The Catholic priests of the Spanish conquistadors believed that the frightening imagery of the pre-conquest civilizations proved that they were enslaved by devils, but perhaps in the case of Chavín de Huántar, at least, the gargoyles serve to protect the sacred sanctuary just as they do on Catholic cathedrals. An alien visitor might also find the sacred image of the deity at the heart of the cathedral no less cruel and barbaric than the jaguar totem of Chavín. One of the things that helped Mike unravel the mysteries of Chavín as far as he has was an understanding of the context in which the mystery traditions of Ancient Greece manifested and flourished around the same time. The Mysteries are central to the Western esoteric tradition, and, as we shall see, one of their central deities also has a penchant for dressing up in the skins of ferocious felines.

The Lion Man has many descendants, it seems, but there are still more clues to be derived from his earliest known manifestation before we pick up later traces of his legacy.

Theriomorphism

Theriomorphism, as opposed to therianthropy or shape-shifting, confers the status of a deity onto an animal. This probably began with ancestor worship; many ancient peoples identified particular animals as ancestor figures. Animal gods are often half-human hybrids, usually combining an animal head with a human body, as in the ancient Egyptian pantheon. Like the Lion Man, the ferocious Egyptian warrior goddess Sekhmet is depicted with a lion’s head and a human body, often crowned with a sun disk, which identifies her as a solar goddess. The same goes fors Bastet, originally an Egyptian warrior lioness, but later depicted with the head of a cat. Both these feline goddesses were revered as protectors of the faithful and of the kingdom. And then there is Bez, of course, our little lion man guardian of all things maternal. A possibly even older lion-man deity than Bez is Narasimha (“lion-man”), described in the Upanishads of the Indian Vedic tradition as the god of knowledge and the Lord of Brahma, the creator god. He is associated with heat and fire and sometimes depicted with a sun-like mane. Other solar gods associated with lions include Ra, Mithras,17 and Yaghuth, while in Christianity Jesus is called the Lion of Judah, the same epithet Rastafarians apply to His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie, King of Kings, Emperor of Ethiopia, represented as a crowned lion. In astrology, the zodiac sign of Leo is ruled by the Sun, whose symbol is  , resembling a golden lion’s eye in bright sunlight. The symbol for gold is also

, resembling a golden lion’s eye in bright sunlight. The symbol for gold is also  .

.

In alchemy, the lion corresponds to both the Sun and gold. The primary symbol of the Philosophers’ Stone, the agent that transmutes base metal into gold, is the Red Lion, which happens to be the most common pub name in Britain. The earliest known stamped gold coins feature a lion’s head, while colour photography, revealing the full spectrum of colours made visible by sunlight, was enabled through the use of gold chloride. The lion Aslan in the Narnia series incorporates all these correspondences.

Star Lore

At least as far back as the third millennium BC 18 the Sumerians associated the constellation they called the lion with the sun, and Leo remains ruled by the sun in contemporary astrology. But just how far back in time can we find evidence for animal-related star lore? Some very interesting recent research by Dr. Michael Rappenglück of the University of Munich suggests that some of the cave paintings of Lascaux (circa 17,000 BP) are pictorial images of constellations, a prime example being a depiction of a bull/aurochs incorporating the constellation of Taurus with the Seven Sisters of the Pleiades above its withers. A panel in the cave of La-Tête-du-Lion (circa 21,000 BP) also features a painted bull/aurochs with seven dots. At both sites, the bull’s eye marks the position of Aldebaran, the primary star in the Taurus constellation. French researcher Chantal Jègues-Wolkiewiez has produced compelling evidence to suggest that the whole gallery of paintings in the Great Hall of Lascaux represents an ice age star map,19 depicting the night sky as it would have appeared to the artists some 17,000 years ago, suggesting a continuity of pictorial astronomical associations going back much further than previously thought.

Figure 5: Lascaux cave painting

Interestingly, the name “seven sisters” has been used for the Pleiades in the languages of many ancient cultures, as far apart as Australia, North America, and Siberia, suggesting an ancient common origin at least as old as the Lion Man, unless the aboriginal Australians coincidentally just happened to choose the same name.20 At Chavín de Huántar, the temple of the Jaguar Man, there are many indications of the cultural importance of astronomy, including a large stone with seven concavities configured like the Pleiades.

Apart from the merging of lion and human anatomical characteristics, the Lion Man has one other distinct feature: there are seven parallel lines carved into its left arm. There are many possible explanations for what these could signify, but if the number seven is in itself significant, then it is possible that they represent the Pleiades. Intriguingly, there is a well-established New Age myth generated by many well-known channellers such as Murry Hope, which claims that the ancestors of humanity are inter-galactic lion beings that colonised the Pleiades. Easy though such claims are to dismiss, it is nevertheless interesting that such an idea should surface and find wide acceptance amongst New Agers just at the time when the Lion Man was being re-membered. I first came across the idea of cosmic lion beings at the same time that I was researching the Lion Man, while on a walk with my friend Sabrina in crop circle country in Wiltshire, England. A somewhat eccentric fellow greeted us as we emerged from our car and insisted on telling us a long and garbled tale. We humoured him, while obliging him to maintain our brisk walking pace, and when we reached the summit of the hill we paused, allowing him to catch his breath and, eventually, reach his punch line, which involved a personal encounter with an alien being with a lion’s head! A few days later, Sabrina reported that there was an exhibition in a gallery in nearby Glastonbury that featured several portraits of lion-headed angelic entities. Previewing it online, the quality of the art did not strike me as especially inspired, so I resisted the urge to visit the gallery and question the artist. That may have been a missed opportunity, but when exploring the esoteric it is easy to get lost if you follow every white rabbit down every hole …

The Magnificent Seven

Another significant seven to consider, perhaps the most significant seven of all (along with the seven colours of the rainbow and the seven notes of a musical octave 21 ) are the seven “wandering stars” visible to the human eye. These wanderers are the visible bodies of our solar system that the ancients observed in an endless dance against the backdrop of the fixed stars. The seven wanderers account for one of our constant time cycles, the seven days of the week—Satur(n)day, Sunday, Mo(o)nday, etc.—as well as the pantheons of such diverse cultures as Chaldean, ancient Greek, Hindu, Norse, Mayan, and Roman, after which the planets are still named in Latin tongues.22 The Lion Man’s makers no doubt experienced a mythic relationship with the night skies that had developed over many thousands of years. Joining the star dots to make pictures and weaving myths out of them is a universal, fundamentally human trait and I have spent many nighttime hours on my back beneath stars throbbing with mysterious stories, meanings, and connections. The heavens, as the devil’s doctor Paracelsus the Great might have said, are an open book for those with the eyes to read it.

There is no reason to believe that the Aurignacians did not imbue the wanderers with personalities and even deify them as later cultures did. It may even be that they identified themselves with the wanderers, recognising a connection with their nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle. They may even have mapped the planets’ movements against the skyscape of the stars upon a mythologised landscape below.

As Above, So Below

One lion man associated with the sun and the number seven is an ancient Vedic deity depicted with seven rays emanating from its crown and described by the great esoteric religious syncretist Helena Blavatsky as the “man-lion Singha … the Solar lion … the emblem of the Sun and the Solar cycle.” 23 Given the endlessly observable phenomenon of the wanderers, only those who doubt that the Aurignacians had a fully developed consciousness would deny that the Lion Man could be an anthropomorphic solar deity, the embodiment of the sun or the solar system as a whole. With its human attributes, the Lion Man may even represent an astonishingly early example of the ancient magical notion of the microcosm, which sees man as embodying the whole of the universe, the macrocosm in miniature. This notion is exemplified in the famous “Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus,” an Egyptian alchemical allegory concerning “the operation of the Sun,” which may be a mere two thousand years old, but possibly echoes a primordial wisdom tradition that may be even older than the Lion Man. Isaac Newton’s translation reads, “That which is below is like that which is above & that which is above is like that which is below …” 24

The idea that the earth mirrors the heavens is found in many traditions and civilisations other than the ancient Egyptians, including the Mayans and the aboriginal Australians. Graham Hancock’s bestselling Heaven’s Mirror explores this idea in detail. There is considerable evidence to suggest that the ancient Egyptians were not just conscientious observers of the heavens, but that they understood the precession of the equinoxes and actually built many of their monuments, such as the pyramids at Giza, to reflect the alignments of certain constellations at certain specific points in history. The Mayans and Australian aboriginal tribes were aware of the “Great Year,” as a full processional cycle is known. Indeed it appears to be central to many of the world’s great myth traditions. A Great Year lasts about 25,800 years, which happens to be the same amount of time that separates the Lion Man from the Lascaux cave paintings.

The question, then, is whether our early Aurignacian ancestors were sufficiently intelligent, observant, and imaginative to make the same associations that we find expressed in much later cultures with combined sun-lion-human-planetary imagery. The answer, according to such experts as Dr. Jill Cook, Head of Prehistory at the British Museum, is an emphatic “yes!” The ability to conceive imaginary abstract concepts and express them in art indicates the activity of what Dr. Cook describes as “a complex super brain like our own, with a well-developed pre-frontal cortex powering the capacity to communicate ideas in speech and art.” 25

It seems clear from the evidence that has emerged in recent decades that the people of the Lion Man were as human as we are. This should shift the pernicious perception that our ancestors of the time were lumbering cavemen dragging their women around by the hair. We were clearly sensitive, creative, expressive people who had mastered the art of tribe and, having identified with the lion as an ancestral totem possibly many thousands of years before, were in the process of taking the lion’s crown and wearing it ourselves.

1 Interestingly “mugwump” is derived from a Native American word meaning “kingpin” or “great chief.”

2 BP means “before present” and is widely used amongst archaeologists when referring to the distant past.

3 Which is pretty jaw-dropping if you consider the cultural shift that happened in Germany in the space of just one generation during the period of the Lion Man’s rediscovery and re-membering.

4 A piece of jawbone, including teeth, discovered by my kinsman Arthur Ogilvy in 1927.

5 http://www.historiaorl.com/pirsig-wehrberger-the-lion-man/.

6 This appellation has become controversial because it has its origins in “the Hottentot Venus,” a name under which a black African woman called Sarah Baartman was exhibited in freak shows in early nineteenth century Europe. Her large breasts and enormous buttocks were supposed by white Europeans (often mockingly) to be a perfect expression of a “savage” black African ideal of feminine beauty.

7 More commonly spelled Bes, but as the “s” is pronounced as a “z,” this spelling makes more sense.

8 I wonder if that original Madchester raver, Bez, member of the seminal Happy Mondays and himself synonymous with music, dance, and pleasure, is aware that his favourite island is named after him. He’ll no doubt be back at Glastonbury Festival this year with “Bez’s Acid House,” so I’ll have the chance to ask him …

9 “Dunbar’s Number” posits the ideal number of tribal members as 150 with an upper limit of 250.

10 Instinctive incest avoidance ensured the success of the species. From a Darwinian perspective: the closer to nature, the more natural the selection. The further from nature, the closer to Freudian complexes.

11 Traditional healer.

12 Traditional Amazonian healing songs.

13 Maleficent sorcerer.

14 Thanks to Google Earth, I now know that our camp was on the northern side of Sechin Alto, a vast Chavín architectural complex dating back over 5,000 years.

15 I hereby propose that the collective noun for a bunch of fairies be a “fantasy.”

16 First published in Strange Attractor Journal, Volume 2 (2005), more recently in Entheogens and the Development of Culture (2013).

17 As Chronos leontocephalus (“lion-headed time”), Mithras (or Aion) is depicted as a lion-headed man, often with wings. In this form, he represents eternity. For the great psychologist C. G. Jung (1875–1961) it represented death/rebirth. Interestingly, I recently came across a depiction of a lion-headed Tibetan deity called Simhamukha, which I immediately recognized from a picture on Valentino’s altar in Ecuador.

18 http://www.ancient-wisdom.com/zodiac.htm.

19 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/871930.stm.

20 Cf. Munya Andrews, Seven Sisters of the Pleiades: Stories from Around the World, Spinifex Press, 2004.

21 The word octave refers to the number eight, the eighth note being the repetition of the first note at a higher octave.

22 In English, the names of some of the planetary days have been supplanted by Norse/Germanic gods, such as Odin/Woden for Wednesday, instead of Mercredi. As we will eventually discover, there are direct connections between Odin/Woden and Hermes/Mercury, just as the thunderbolt-wielding Thor replaced his counterpart Zeus/Jove/Jupiter.

23 Blavatsky, 1888.

24 We now know that Newton was obsessed with alchemy; cf. Dobbs, 1975.

25 Jill Cook, Ice Age Art: Arrival of the Modern Mind, British Museum Press, 2013.