Historical Experiences of Development:

Large Firms and Extreme Wealth

Three big firms—BASF, Bayer, and Hoechst (now Aventis)—established the chemicals industry in Germany at the end of the 19th century, initially specializing in synthetic dyes. Synthetic dyes had just been invented, by the Englishman William Perkin, to serve the large textile industry. Britain was rich in coal, the main input in dye production, and had an early start on the new product. Given the innovation, resources, and market, it should have dominated the market. However, in the 1880s the Germans built large plants that could produce 300 to 400 dyes, compared with the 30 to 40 the British could produce. They also invested in organization and marketing (Bayer, for example, developed a salesforce to work with more than 20,000 customers worldwide). By 1913 two-thirds of the 160,000 tons of dyes produced globally came from these three firms. Similar strategies allowed German companies to dominate pharmaceuticals and other chemicals as well (Chandler 1992, Wegenroth 1997).

The development of the German chemicals industry is the story of a few individuals and their large investments—investments that allowed German firms to control trade in electrical equipment, steel, and office machinery at the expense of smaller British firms. In considering the German experience, as well as the experiences of the United States and other industrial countries, historian Alfred Chandler (1992, 11) writes, “For the past century large managerial enterprises have been engines of economic growth and transformation in modern economies.” The same could be written of the recent growth surges in emerging markets.

German industrialists from the period included Werner von Siemens and Johann Georg Halske of Siemens AG, Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler of Daimler Benz, Walther Rathenau of AEG, Friedrich Bayer of Bayer Aspirin, Friedrich Engelhorn of BASF, August Thyssen and Friedrich Krupp of Thyssen-Krupp Steel, and Wilhelm von Finck of Allianz. All their companies thrive to this day, and although some fortunes were squeezed during the economic crisis of the 1920s and World War II, many of their descendants remain among Germany’s richest people.

The story of the dramatic rise of these industrial titans in Germany illustrates how the Industrial Revolution was inextricably tied to large firms and wealthy industrialists. This chapter examines that history in the United States and Europe and documents similar experiences in the Asian countries that have industrialized more recently. Mega firms and rich industrialists were an essential contributor to the dramatic growth in these economies. Despite their ties to the government, they faced stiff competition in their industrial sectors and emerged on top by dint of factors that went far beyond any favoritism they might have enjoyed. In contrast, attempts to succeed by big firms that were not tied to wealthy individuals have fallen short, as have attempts by countries to grow with wealth but without big firms. An extreme example of the first failure can be found in communism, which experimented with big firms supported by the state but lacking market pressure for the allocation of resources and rewards for the allocation of talent. Communism failed to engender growth because the state directed resources to designated industries and companies rather than to the most efficient or successful firms, while the firms that were successful did not own their profits and hence could not reinvest them. The second failure (wealth without big firms) occurred in a number of other countries when state control or capture of the investment process strangled competition and discouraged innovation and investment. In these instances, wealth accrued not to the owners of the most economically effective firms but to the firms most politically connected. A firm reliant on favoritism within a country may do well domestically, but the record shows that it rarely is able to compete globally.

Big Firms and Big Money during Industrialization

In 1790 Samuel Slater built the first factory in the United States, a textile factory in Rhode Island. By the end of the 19th century, 40 percent of industrial establishments were factories, employing 20 percent of the American workforce. The period of industrialization that followed transformed the country, with the development of industrial centers, factory jobs, and extreme wealth.

The economic development of Indianapolis is a good example of US industrialization. In 1850 less than 5 percent of the city’s workforce worked in large factories; the share had risen to nearly 60 percent just 30 years later. Factories paid 10 to 25 percent more than small shops, with the largest factories paying the most (Robinson and Briggs 1991). The shift from small-scale production to manufacturing enriched company founders and created the middle-class worker that embodies development.

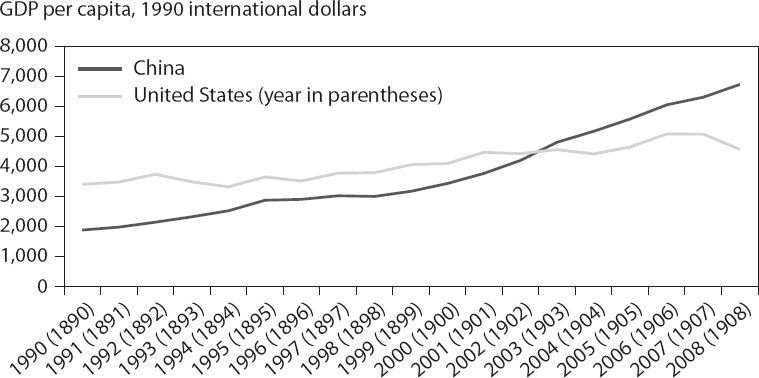

Figure 4.1 Per capita income in BRICS relative to the United States at similar stages of development

Source: Maddison Project, 2013, www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm.

Emerging markets are at a similar stage of development. Per capita income in the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) is in the range of that in the United States in 1840–1929 (figure 4.1). Brazil was at the stage of development the United States was during World War I, at the beginning of the period, in 1996; Russia and South Africa were at the level of the United States around the turn of the century; India is at about the level of the United States in 1845; and China is about the level of the United States around 1880. In recent decades growth in the BRICS has been similar to or more rapid than growth in the United States between 1840 and 1927 (lower panel).

Figure 4.2 Growth in China, 1990–2008, versus growth in the United States, 1890–1908

Source: Maddison Project, 2013, www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm.

The ease of accessing rich global markets has allowed the BRICS to grow rapidly. Figure 4.2 depicts the growth surge the United States experienced around the turn of the 20th century. It compares changes in US per capita GDP from 1890 to 1908 with China’s growth at the turn of the 21st century. China’s growth in recent years has been phenomenal even compared with US growth at a similar stage of development. Per capita GDP in China more than tripled over these 18 years—a far larger increase than the 50 percent increase in the United States over a similar period. An important reason why China has grown more rapidly is that lower transportation and trade costs allow large firms to easily access markets both within their borders and abroad, facilitating rapid growth.

Big Business, Big Money during US Industrialization

Industrialization in the United States created extreme wealth. Many household names, such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, grew rich during this time. New technologies and scale economies made large firms many times more competitive than small firms, contributing enormously to productivity growth; falling trade costs allowed these firms to compete globally.

In the tobacco industry, the invention of two machines in the 1880s—one that produced cigarettes and one that packed them—made James B. Duke’s American Tobacco company immediately competitive in Europe and Asia, where Imperial Tobacco of Britain had dominated. In food and beverages, high-speed canning and (later) bottling changed production possibilities, leading to the rise of Heinz, Campbell Soup, California Packing (Del Monte), Anheuser-Busch, and Coca-Cola. New machinery to make paper from wood led to the creation of the International Paper Company. Andrew Carnegie combined coke ovens, blast furnaces, and rolling and shaping mills into one massive company that reduced the price of steel from $68 per ton in 1880 to $18 in 1898. John D. Rockefeller’s dominance in oil came in the 1870s, when he built the nation’s largest refinery, cutting the cost of a gallon of kerosene in half. (Chapter 3 in Chandler, Amatori, and Hikino 1997 discusses these and other examples.)

The increasing concentration of production eventually culminated in the development of antitrust laws, but when these men started their businesses, the industries they were active in were contestable. An important driver of cost saving in steel was competition, not just with US producers but with British firms as well. Rockefeller focused on enhancing productivity to compete internationally. The reduction in cost from building large refineries allowed Standard Oil to undercut Russian and East Indian oil in global markets.

Even services, such as ocean voyages, proved open to entry. The US government heavily subsidized shipping magnate Edward Collins to build steamships that could compete with the British and deliver overseas mail. Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had experience in steamship traffic on the Hudson River, offered to deliver the mail for less. He focused on sturdy, reliable ships and volume, offering innovations such as third-class fares. His improvements and lower costs ultimately forced the Collins (subsidized) line to exit the business (Folsom 1987).

Many of the large companies created in this period—such as General Electric, Exxon and Mobil, Ford, Heinz, Coca-Cola, and US Steel—are still around today. Many of the descendants of the founders remain extremely wealthy.

Robber Barons versus Emerging-Market Tycoons

How do the 28 richest American “robber barons” compare with the 28 richest self-made men of the 1950s and the self-made billionaires in today’s emerging markets? Resources account for the largest share in all periods except 2001 (table 4.1). An important difference is the greater significance of tradables and finance among emerging-market billionaires. The higher share of wealth via tradables is a positive indicator for current wealth, since this sector is by definition competitive.

Table 4.1 Industries of the 28 richest individuals in the United States and emerging markets (percent)

Sources: Data from Josephson (1934); Lundberg (1968); and Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Growth without Large Firms

The mammoth enterprises (businesses with more than 5,000 employees) that developed in the United States and Germany around the turn of the century are household names. Similar patterns are evident in Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland.

The smallest European economies were different. Denmark and Norway had only one or two large firms as other countries were industrializing (Schröter 1997). Denmark had just one large firm, Carlsberg (beer). Norway had two, Norsk Hydro (fertilizer) and Statoil (oil). Did these economies buck the trend of large firms and rich entrepreneurs? If so, how did they develop?

Two important features set these countries apart. First, both Denmark and Norway are very small, with homogeneous populations that numbered just above 2 million in 1900. Second, both countries have relatively educated populations and invested in research to make agriculture more efficient. The early part of their development was connected to feeding Europe; they were not direct beneficiaries of the industrial movement but gained from strong demand for agricultural products by their neighbors. The tradition of open trade that they embraced, which began with agriculture, allowed them to follow a more standard path in the long run.

Denmark initially specialized in agriculture, especially dairy products. Its only large firm at the turn of the century was Carlsberg. One explanation for Denmark’s success during the industrialization of much of the rest of Europe is that it benefited from spillovers from trade, climate, and location. As Europe grew richer, the demand for high-quality animal products rose, and Denmark (and Norway) were there to fill the gap. They had the right climate and location to export high-quality perishable goods.

Once the structure of agriculture changed and it could no longer employ the Danish population, the superrich and their firms eventually helped the country modernize. Today Denmark has a slightly higher billionaire density given its per capita income than would be predicted based on cross-country data. Danish billionaires are associated with big companies—Lego, Bestseller, JYSK, Coloplast, ECCO—that benefit from international trade (as opposed to finance or resources).

While Norway’s development was similar to Denmark’s, at least one big company played an important role in its early development. Norway’s first large firm, Norsk Hydro, was founded by Sam Hyde, a Norwegian industrialist and engineer, and financed by the Wallenberg family of Sweden, the Swedish version of the Rockefellers. The company developed energy and fertilizer using a revolutionary technique developed by the Norwegian scientist Kristian Birkeland. Norsk Hydro provided the fertilizer that shaped Norway’s emergence as an agricultural powerhouse. It remains on the Forbes Global 2000 list to this day, and the Wallenbergs remain one of Sweden’s richest families (though most of their $6.4 billion fortune is tied up in foundations). Norway later developed large shipping and oil companies. Today it has the expected density of extreme wealth given its stage of development.

These countries took a somewhat unusual path. Growth was initially fueled by global demand, small-scale agricultural production, and trade. They later took the more traditional path of using large-scale enterprises to modernize.

Big Firms and Big Money in Asia

The United States, Germany, and other European industrializers were not alone in undergoing a transformation toward large firms. Asian economies have witnessed a similar process.

Business and Wealth in Japan

Before World War II, wealth in Japan was dominated by zaibatsu—large conglomerates controlled by single families. The four largest were Mitsui (finance and trade), Sumitomo (mining), Mitsubishi (shipping), and Yasuda (banking and insurance). As new industries developed, these business groups expanded. Mitsubishi, for example, moved from shipping into related sectors, including coal, shipbuilding, iron, and marine insurance.

Japanese industrial development was transformed after World War II, when Occupation forces dissolved or reorganized nearly all of the zaibatsu. The new system of informal business groups (keiretsu) maintained a similar structure to the zaibatsu, though ownership was less concentrated. The rise of large private enterprise had already taken hold and continued to thrive. A small number of families retained a significant hold on the economy, although their stakes in the companies were not the majority stakes of the zaibatsu. The keiretsu firms represented just 0.1 percent of all Japanese companies, but their revenues accounted for 25 percent of postwar GDP (Pempel 1998). The biggest change in the shift to the keiretsu was who the rich were: Of the 100 richest people in 1954, not a single one was among the richest in 1944 (Morikawa 1997).

Other Asian Successes

In Korea the chaebol (conglomerates) created firms such as Samsung, Hyundai, and Daewoo. In 1973 the top 30 chaebol accounted for less than 10 percent of GDP; by the mid-1980s they held one-third of GDP (Ahn 2010). The families behind industrialization remain in control of the largest firms. Today Samsung’s revenue alone is nearly 20 percent of GDP.

Between 1975 and 1990, Korea went from being a poor country with annual per capita income of $3,000 to an upper-middle-income country with per capita income of $8,000 a year (measured in 1990 international dollars). To put this extraordinary growth in context, in 1975 income in South Korea was about equal to income in Nicaragua; the country was sandwiched between North Korea and Namibia in terms of level of development. Despite few natural resources, by 1990 South Korea ranked in the top third of countries. In 1975 per capita income was just 19 percent of US per capita income; by 1990 it had risen to 38 percent, and in 2008 it was over 60 percent.

Singapore grew thanks to a combination of domestic and foreign investment. Now one of the richest countries in the world, at independence in 1965 the tiny island of 3 million people had a real per capita income that was barely above that of Guatemala and lower than that of Jamaica. Just seven years later, one-quarter of Singapore’s manufacturing firms were either foreign owned or joint ventures.

The importance of foreign investment in Singapore’s takeoff separates it from the national industrialists of Germany, the United States, and Japan. Foreign multinationals have the expertise and capital to build large, efficient plants almost overnight, transforming a country’s productivity frontier. In Singapore large foreign multinationals built a domestic industry that supported rapid investment. The excellent business climate fostered by its founder, Lee Kuan Yew, who encouraged foreign investment and promoted education and infrastructure improvements (while limiting civil liberties), allowed a small country with no natural resources except its location to grow economically at one of the fastest rates in history. Its probusiness climate encouraged one large company after another to choose Singapore as a hub.

Foreign investment generated a new dynamic in which domestic business investment was drawn to complementary industries that required local knowledge. This combination of foreign and domestic enterprises supported the growth of commerce, building the logistics industry that made Singapore so attractive as a business destination.

Chang Yun Chung, for example, cofounded Pacific International Lines in 1967, after Singapore split from Malaysia. The company is now one of the largest shipping companies in the world, with a fleet of 180 ships. Another shipping magnate, Lim Oon Kuin, began by delivering diesel fuel to fishermen. From there he moved into shipping and logistics.

Today the density of the superrich in Singapore is among the highest in the world. As in other countries, extreme wealth in Singapore came with growth.

China’s Mega Firms

Development in China is following a pattern similar to that of earlier modernizers. In 2014 China was home to the world’s 3 largest public companies and 5 of the top 10.1 As elsewhere, development in China has come with large firms and large fortunes.

Table 4.2 shows the number of top 500 largest firms by country. The big gainers from 1962 to 1993 were Japan and Korea, at the expense of the United States and the United Kingdom. From 1993 to 2014, China and Russia were the main gainers, at the expense of Japan and the United States.

Table 4.2 shows an extraordinary gain in the number of mega firms in China from 1993–2014, similar to the expansion in Japan from 1962 to 1993. Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Song (2014) examine why large firms and the individuals behind them have supported development in China, despite what in the West might be considered cronyism or state capitalism. They argue that local governments, which hand out favors, compete with one another, effectively putting incentives in the right place. One example they give is the East Hope Group, owned by billionaire Liu Yongxing. The group expanded from agribusiness to aluminum with help from the local government of Sanmenxia, a city in Henan Province with large bauxite deposits. A state-owned firm had the exclusive right to purchase bauxite, but the Hope Group managed to negotiate a deal with local officials to obtain bauxite, despite resistance from the incumbent monopoly. Hope began producing aluminum in 2005, and other private firms followed; by 2008 the market share of the state-owned firm had fallen to 50 percent. Ultimately, the market proved contestable, open to entry.

Table 4.2 Number of top 500 largest firms, by country, 1962, 1993, and 2014

Note: For 1962 and 1993, the top 500 companies are ranked by sales. For 2014 companies are ranked based on additional metrics. See the 2014 Fortune 500 list for explanation of the methodology used in 2014.

Sources: Data for 1962 and 1993: Chandler, Amatori, and Hikino (1997); data for 2014: Fortune 500 list.

In the automotive sector, competition developed between Shanghai-GM and Chery (a company based in the city of Wuhu). Working through local government officials, Chery eventually managed to get a license from the central government to make cars for the province, which then turned into a license to sell throughout China. The company is now one of the largest car producers in China. “Competition between local governments may have played a central role in allowing new firms to emerge and challenge incumbent firms. This is important for technical progress and long-run growth,” according to Bai, Hsieh, and Song (2014, 7).

China is a large enough country that competition can come from within, as municipalities compete. Most developing-country firms, however, require the push and pull of global markets to grow. The push from openness provides incentives to innovate and use resources efficiently. A car producer capable of competing with European and American firms, as the Japanese and later Korean firms did, must use new technologies. Foreign markets offer a much bigger market, which facilitates rapid growth. For these companies the incentive to grow large comes from the prospect of tapping global markets that are accessible if a firm is good enough.

Contested versus Uncontested Wealth

In many cases money and large firms do not go beyond borders, as happened with the Ben Ali–connected firms in Tunisia or the Marcos-connected firms in the Philippines. These firms are less likely to produce the type of wealth that lands owners on the Forbes World’s Billionaires List. The experiences of the United States, Japan, South Korea, and China show that big business, even with some cronyism, still promotes economic growth, provided markets are contestable. The main constraint to growth through big business is when the firms compete in protected domestic markets.

Argentina during the turn of the 19th century is an example of a country that appeared ready to take off. With real per capita income similar to France and between Sweden and Germany, an influx of foreign investment, and labor, Argentina was primed to grow. But the boost from railways and transportation that allowed the United States to become a manufacturing center never materialized in Argentina. One explanation is that import-substitution policies incentivized business to focus on supplying the small Argentine market. Inward-looking policies delayed industrialization because the market was too small for firms to benefit from returns to scale and the lack of competition meant that there was less competitive pressure on resource allocation. As a result, the industrial development of Argentina remained incomplete, and as of 1929 the largest firms remained in food, tobacco, and some textiles but little manufacturing (Barbero 1997).

The importance of competition cannot be overstated. To see how the orientation, size, and global reach of the firms associated with extreme wealth matters, it is informative to compare Chile and Tunisia, two small middle-income countries with populations of less than 20 million. In 1985 the two countries were at a similar stage of development, with per capita income of $1,000 to $1,500. In 2014 the average Chilean, with a per capita income of $15,230, was more than three times as rich as the average Tunisian.2 Chile had a dozen billionaires in 2014; Tunisia had none.

Horst Paulmann, the second-richest person in Chile, founded Cencosud, one of Latin America’s biggest retail chains. He opened the first hypermarket (more than 5,000 square feet) in 1976, moving into Argentina in the 1980s as the company pioneered retail globalization in the region. Cencosud is now the fourth-largest grocery chain in Latin America. It owns 645 supermarkets in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru and competes with global companies like Walmart and Carrefour, as well as other Latin American chains. The company controls 11 percent of the Chilean grocery market.3

The largest Tunisian retail chains operate under licenses from French chains. The largest, Casino, is owned by Marouane Mabrouk, who is married to the youngest daughter of former president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.4 The second-largest, Carrefour, is owned by the Ulysse Trading and Industrial Companies (UTIC), the conglomerate by Taoufik Chaibi, whose nephew is married to Ben Ali’s second daughter. Together these companies control two-thirds of the Tunisian market. These franchises enriched their owners, but they failed to create innovative businesses that spread globally or create billions in wealth for their owners.

What the Tunisian experience highlights is that the emergence of large firms is critical for growth but not sufficient. Three ingredients are needed: entrepreneurs, mega firms, and competition. Government connections are not necessarily detrimental to growth, as long as firms are forced to compete globally. Bob Rijkers, Caroline Freund, and Antonio Nucifora (2014) show that President Ben Ali and his extended family controlled a large share of Tunisia’s private sector—so much so that 21 percent of all corporate profits accrued to them.5 The family was most prominent in nontradable sectors, such as telecommunications, transportation, retail, and hotels, where they benefited from monopoly power and used the regulatory environment to reap profits. Instead of creating a business-friendly climate in Tunisia, they used the investment code as a get-rich-quick tool to protect their domestic interests. Ben Ali signed decrees limiting domestic and foreign entry into sectors where family firms were prominent. One example is the failed entry of McDonald’s into Tunisia. The company was reportedly refused access when it rebuffed a request from Ben Ali’s family members for the lucrative franchise and instead requested competitive bidding. This type of concentration in large domestically oriented firms with little competition from foreign direct investment reduces competition. Firms in such markets lack the incentive and innovation necessary to compete in global markets. They become large in domestic markets, not globally competitive.

In the late 1990s, similar problems of uncompetitive crony capitalism arose in some East Asian countries, where corporate wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few families, to the detriment of development (Claessens, Djankov, and Lang 2000). About 17 percent of the total value of listed corporate assets in Indonesia and the Philippines was controlled by a single family (the Suharto family in Indonesia, the Marcos family in the Philippines), with 10 families controlling half of all corporate assets in each country. The Suharto family controlled 417 listed and unlisted companies, through business groups led by children, other relatives, and business partners, many of whom also held or had held government offices. Imelda Marcos, the widow of former Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos, described her family’s economic power as follows: “We practically own everything in the Philippines, from electricity, telecommunications, airlines, banking, beer and tobacco, newspaper publishing, television stations, shipping, oil and mining, hotels and beach resorts down to coconut milling, small farms, real estate, and insurance.”6 Like the Ben Ali clan, the Marcos family focused on domestically consumed sectors, a clear indication that wealth was not being created in contestable markets.

Big Firms without Wealth Creation

In Argentina, Tunisia, the Philippines, and Indonesia, wealth was created without globally competitive firms. At the opposite extreme was the Soviet Union, which created mega firms without wealth.

For a brief period, when the best firms were nationalized, the system seemed to work. State trusts were created from the most successful of the nationalized companies in the early 1920s. At first firms performed well, as the least productive factories were shuttered. The problem was that only 20 percent of the profits of each trust were retained as reserve capital; 80 percent was remitted to the state budget, constraining growth by the best-performing firms. From the 1920s to the 1970s, centralized investment as a share of total investment increased from 45 to 71 percent. The best companies were not allowed to thrive, as there was neither incentive nor ability to expand production (Yudanov 1997). The worst companies were not closed but subsidized by the better companies.

The state-owned behemoths did not grow through the same process as the emerging-market giants. Rather than flowing to the most productive firms, capital and labor were simply directed to certain firms. This allocation of resources did not create wealth or spur growth.

Effects of Wealth on the Economy

The theme of this book is that development depends on big business and a competitive environment, one outcome of which is the creation of enormous personal fortunes. A problem is that competition can get hijacked along the way by the power money creates, stalling the process. Once created, a powerful business class will seek to protect its interests. To the extent that doing so involves erecting barriers to entry or eliciting subsidies, consumers will suffer; to the extent that it involves protecting property rights or promoting democracy, citizens will benefit.

Restriction of Competition

Once large firms and fortunes are created, company founders may seek government interventions to maintain market share or growth. When the national champions are large exporters, global competition naturally tames the most egregious demands. In countries where the biggest firms compete on global markets, foreign competition limits the effectiveness of the most costly government policies. For example, restricting trade or creating domestic entry barriers are costly because they reduce competition and raise consumer prices, but these policies are ineffective in promoting a large exporting firm that competes with foreign firms on the global market. The policies sought by the business community are most welfare reducing when the main market of the largest firms is the domestic one. The concern about preserving competition once large companies are created is therefore especially relevant in large economies like the BRICS, where many firms are primarily dependent on local consumers and may therefore benefit from barriers to entry.

One such example can be found in the Chinese insurance sector, where not surprisingly the customer base is domestic. Close government and business relations in China allowed Ping An Insurance to protect its monopoly power, enriching a political leader and his family. After the Asian financial crisis, large financial companies in China were broken up, in a process overseen by Wen Jiabao, China’s vice premier at the time. Ping An Insurance resisted, “humbly requesting that the vice premier lead and coordinate the matter from a higher level.”7 The company remained intact and is now one of China’s largest financial services company, bigger than AIG, Metlife, or Prudential. The Wen family is estimated to have made more than $2 billion on its shares in Ping An as of 2007.8

In the United States, the robber barons also attempted to maintain monopoly power, but the government ultimately stepped in. The Chinese government is similarly responding. China’s antimonopoly law, adopted in 2007, was long in the making. Pressure from foreign governments, accession to the World Trade Organization, and the Chinese reform agenda have all been credited with its development. External observers have found the new law to be compatible with laws in the West and note that it is being enforced (Mariniello 2013). The main concern about Chinese competition policy is that it will be used aggressively against foreign firms operating in China, not that it will fail to discipline Chinese monopoly power, which unfortunately will also limit competition.

The process of private businesses in China growing large, misbehaving, and eventually being regulated is not very different from developments in the United States during the late 19th century. In order to control markets, large firms in industries like railroad and oil colluded on prices or quantities, but firms always attempted to cheat to corner the market. One way around this problem was to create trusts, conglomerates that had large stakes in all of the leading firms in the same industry. Trusts effectively ruled the market, stopping entry of new unconnected firms and setting prices.

Consumers in the United States were outraged, as the media reported price increases on a number of commodities. Congress took action in 1890, passing the Sherman Antitrust Act. The law took many years to be implemented, but it remains in use as an important tool to prevent anticompetitive behavior. In large countries, and in sectors that are inherently noncompetitive, creating and implementing competition law becomes increasingly important as countries develop.

Protection of Property Rights

Attempts by business to protect their interests are not always bad for the economy. The desire to safeguard wealth can lead to better protection of property rights and better polity, because a powerful state always has means to expropriate.

In the Middle Ages, a new class of large-scale industrialists promoted institutional reform by demanding property rights and legal protection. Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson (2005) show that between 1500 and 1800, the European countries that traded most with the New World grew fastest and that when institutions were adaptable, the trading countries had the most rapid institutional development and growth. They argue that Atlantic trade created a powerful commercial class, which demanded property rights to protect its business interests. As long as there were significant checks on the monarchy, institutions adapted. They compare England and the Netherlands, where commercial interests developed outside of the Crown and pressed for protection of their businesses, with Portugal and Spain, where they did not.

Supporting this view, Saumitra Jha (2015) uses detailed data on the assets of members of England’s parliaments in 1628 and 1640–60. He finds that moderates who held shares in major companies abroad were more likely to support revolutionary reforms. Jha argues that the economic opportunity created by overseas investment was critical in consolidating the parliamentary majority for reform. Business interests and openness to trade and investment played an important role in institutional development.

Influence over the Political System

How the rich are likely to influence politics in emerging markets remains unclear. The rich may have different political preferences from the rest of the population and succeed in effecting change that is bad for the majority. But they may also act in the interests of the people. In autocracies, for example, the preferences of the new rich may be closer to those of the population than to the leadership.

While the issue of the excessive political influence of businesspeople is beyond the scope of this book, one common theme that emerges from the literature on the subject is that the rich use their money and influence to get their interests served by government, often at the expense of the rest of the population.9 Much of the literature focuses on the United States, where campaign stops at the summer homes of the rich are a national pastime and wealth seems to be playing a bigger and bigger role in government.

In contrast, in emerging markets, many of which are not well-established democracies, elites may help rein in a powerful leader. The superrich sometimes take extreme risks to promote democracy (examples include Mikhail Khodorkovsky of Russia and Wang Gongquan of China, both of whom spent time in prison and lost their fortunes). Before billionaires from China dominated the list of the richest people from emerging markets, the conventional wisdom was that the government prevented any one person from getting too rich because the associated power might threaten the government’s control. It remains to be seen in which, if any, direction Jack Ma, Robin Li, or Ma Huateng will push the Chinese government.

US history is, of course, not absent elites who did great things. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe were all part of the slave-owning planter aristocracy when they started the revolution. Madison wrote the Constitution.

Indeed, a body of literature shows that it is the elites who tend to promote political change. Connections to government officials are useful. But given that other wealthy people can exploit their connections (to the detriment of competitors), the wealthy class may prefer rules and accountability. Alessandro Lizzeri and Nicola Persico (2004) argue that British elites favored democracy (broader franchise) precisely because it offered better incentives to politicians—less pork-barrel politics.

Since Seymour Lipset (1959), a large body of literature has found a strong link between economic development and democracy. It is hard therefore to argue that large-scale private business, which has been an integral part of successful development, is inimical to democracy. South Korea developed the chaebol first and democracy later. Carlos Slim bought Telmex from the government before Mexico democratized. In Eastern Europe big business and democracy have for the most part grown up together. Evelyne Huber, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and John Stephens (1993), who examine democratization in the advanced countries and Latin America, argue that economic development promotes democracy precisely because of the growing capitalist class. Capitalist transformation is important because it enlarges the working and middle classes and facilitates self-organization. The transition from a landed upper class to an industrial upper class with a thriving middle class and urbanization promotes a democratic shift. Huber, Rueschemeyer, and Stephens interpret the data to mean that an agricultural elite is in general bad for democracy; big business is not. From this perspective, it is not surprising that the Middle East and North Africa, the least democratized region in the world, is also the least globally integrated region and one in which big business is least developed.

The political ramifications of growing wealth in emerging markets are worth watching, and they will not all be negative. The rise of company founders competing in global markets is a positive sign, because they are likely to be more connected to citizens and global values than to specific government officials, especially compared with billionaires associated with resource-related or inherited wealth.

Takeaways

The vast majority of countries never experience high rates of growth for a long enough stretch of time to become rich. The few that have accomplished this feat in the past two centuries did so with the help of private ownership, large firms, and competition. Crony capitalist systems have created big business, wealth, and growth only when the largest firms compete in global markets.

Big money, big business, competition, and development all work together. Highly concentrated wealth without globally competitive large firms (as in Tunisia) has not led to growth, and large firms that did not create wealth (as in the Soviet Union) did not spur development.

1. Liyan Chen, “The World’s Largest Companies: China Takes over the Top Three Spots,” Forbes, May 7, 2014.

2. Calculated using gross national income per capita in current US dollars.

3. “Top Grocery Retailers in Latin America,” Agriculture and Agrifood Canada, August, 2012.

4. “Corruption in Tunisia Part III: Political Implications,” WikiLeaks, October 12, 2011.

5. Ishac Diwan, Philip Keefer, and Marc Schiffbauer (2014) find similar results in Egypt for Mubarak cronies before the 2011 revolution.

6. Tony Tassel, “Mrs. Marcos in Legal Fight to Get $13bn,” Financial Times, December 8, 1998.

7. David Barbosa, “Lobbying, a Windfall and a Leader’s Family,” New York Times, November 24, 2012.

8. Ibid.

9. Darrell West (2014) finds that billionaires have sought public office in 13 countries, 7 of them emerging markets (India, Georgia, Lebanon, the Philippines, Russia, Thailand, and Ukraine). Once in office, they pursue policies that are very specific to their interests. The most striking example is Georgia’s Boris Ivanishvili, who, having made his fortune in Russia, made it his mission to eliminate the anti-Russian sentiment that was prevalent in the previous regime. West discusses the behind-the-scenes influence of the superrich in detail, with a focus on the United States and campaign contributions. John Kampfner (2014) notes that the elite of 2,000 years ago are similar to today’s superrich, some of whom are hypercompetitive, paranoid, and consumed with the desire to be remembered. As a result, they tend to interfere in politics. Kevin Phillips (2002) shows how the rich have worked with the politically powerful throughout US history, supporting their joint interests.