4 FULL CITY TO DARK FRENCH

COFFEE ROASTING AND ESPRESSO

Roasting is one key to the transformation of the tasteless, raw seeds of an obscure tree from the horn of Africa into the rich, resonant beverage we know as coffee. The flavor nuances imparted to coffee by roasting are particularly important in espresso cuisine, because the dark styles of roast used in espresso tend to mute taste characteristics inherent in the bean itself and replace them with characteristics generated by the roast.

ROASTING CHEMISTRY

The green coffee bean, like all the other nuts, kernels, and beans we consume, is composed of fats, proteins, fiber, and miscellaneous chemical compounds. The aroma and flavor that make coffee so distinctive are present only potentially until the heat of roasting simultaneously forces much of the moisture out of the bean and draws out of the base matter of the bean fragrant little beads of a volatile, oily substance variously called coffee essence, coffee oil, or coffeol. This substance is not properly an oil, since it dissolves in water. It also evaporates easily, quickly absorbs other less desirable flavors, and generally proves to be as fragile a substance as it is tasty. Without it, there’s no coffee, only sour brown water and caffeine, yet it constitutes only 0.5 percent of the weight of the bean.

The roasted bean is, in a sense, simply a dry package for this oil. In medium- or American-roast coffee, the oil gathers in little pockets throughout the heart of the bean. As the bean is held in the roaster for longer periods or at higher temperatures, as it is with some darker espresso blends, more moisture is lost, and the oil develops further and begins to rise to the surface of the bean, giving darker-roasted beans their characteristic slick-to-oily appearance. Beneath the oil, the hard matter of the bean begins to contribute the slightly bitter flavor characteristic of the darkest roasts of coffees. Eventually, the bean turns to near charcoal and tastes definitively burned. This ultimately roasted coffee, variously called dark French, heavy roast, Neapolitan, or occasionally Italian, has an unmistakable charcoal tang.

Dark roasts also contain considerably less acid and somewhat less caffeine than lighter roasts; these substances go up the chimney with the roasting smoke. Consequently, dark roasts used in the espresso cuisine display less of the dry snap or bite coffee people call “acidy” and tend to be sweeter rather than brisk.

ROAST STYLE AND ESPRESSO

The espresso brewing method is so efficient at extracting flavor from coffee that it tends to exaggerate flavor characteristics. Qualities that may be exhilarating or agreeable in other brewing methods can turn into irritating distractions when subject to the amplification of espresso brewing. The espresso method rewards deep, sweet, subtle flavor characteristics rather than those that are extreme or idiosyncratic.

Consequently, the best roasts for espresso brewing are those that are a bit darker than the American norm, but not too dark. Coffees roasted to the light through medium end of the spectrum typically are too acidy and bright, and tend to taste sharp or sour as espresso. On the other hand, extremely dark, almost black roasts come across as thin, watery, and charred.

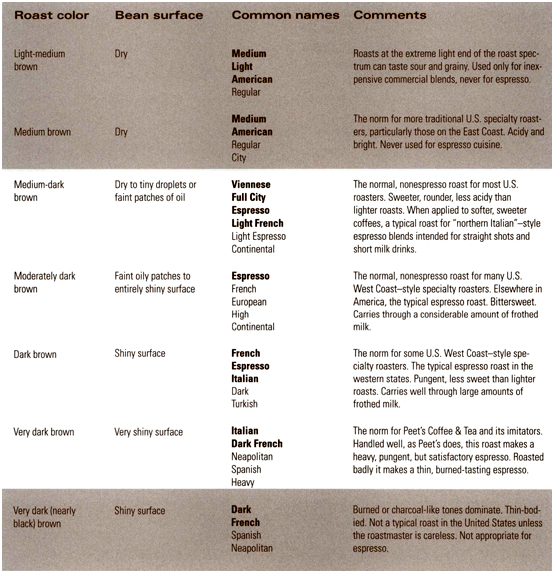

Roasting Terminology

The common terms for roasts among most coffee sellers are the standard American or medium roast (medium brown in color; bright and acidy tasting); Viennese, light French, or full city (slightly darker in color than American; smoother and less acidy with the merest undertone of dark bittersweetness); Italian, espresso, or continental (medium-dark brown in color with oily patches on the surface of the bean; only the slightest acidy tones, with the bittersweet tang distinct); Italian, espresso, or French (dark brown in color; surface of the bean covered with oil; all acidy notes gone and the bittersweetness dominant); and French, dark French, or Neapolitan (nearly black in color; very oily surface; charcoal or burned tones dominate; thin-bodied in the cup).

Of course, the “standard” medium roast varies greatly by region and by roaster. The West Coast traditionally prefers a darker standard than the East Coast, with the Midwest appropriately somewhere between. As for roasters, all vary the roast slightly to bring out what they regard as the unique characteristics of each coffee, but this perfect moment varies according to the philosophy of the roaster. To roasters who adhere to the dark end of the spectrum, lighter-roasted coffees taste too acidy and almost sour; to those who adhere to the light end, darker-roasted coffees taste muted or charred.

Roasting Philosophy and Espresso

A similar difference in philosophy prevails among roasters in regard to espresso coffees. Some prefer to roast their espresso blends less darkly, some more. Some prefer to stop the roasting at the point where the natural sweetness and acidy tones of the coffee are still discernible and the dark-roasted bittersweetness is just beginning to develop, with only patches of oil flecking the still dry surface of the bean. Others prefer a darker roast in which the characteristic bittersweetness of the dark roast completely dominates any remaining acidy tones, and the bean is distinctly dark brown in color and shiny with oil.

It is best to learn to associate flavor with the color and appearance of the bean rather than with name alone, but for reference almost everything you need to know about the names of roasts is condensed in chart form here, with the roast styles used in espresso cuisine indicated.

ONLY BY TASTING

Only by tasting a variety of dark-roasted blends from a variety of coffee roasters can you determine whether you prefer your espresso coffee roasted in a style that leans toward the lighter end of the espresso spectrum, with some of the acidy notes still discernible, or toward the darker end, where the bittersweet tones completely dominate. You may even find that you prefer a distinctly acidy style or (particularly if you liked the coffee you tasted in northern France) a very dark, almost black, charred-tasting style.

Your choice will be complicated because different blends of raw beans respond differently to the impact of the roast. Espresso blends in the classic northern Italian style, like the famous Illy Caffè, combine coffees from Brazil that are naturally sweet, low-acid, and full-bodied. These Brazil beans need only a moderately dark roast to muffle their already mild acidity and develop their inherent sweetness. On the other hand, many West Coast American espresso blends are heavy with powerful, high-grown, brightly acidy beans from Central America that literally need to be tamed by a roast sufficiently dark enough to mute their powerful acidity. For more information on beans and blending see Chapter 5 and Chapter 6.

Furthermore, two dark-roasted coffees may look the same but taste radically different depending on how tactfully the roast was handled. The trick to roasting coffee dark without losing flavor is moderating the temperature inside the roasting chamber toward the end of the roast so the sugars in the bean caramelize rather than burn. Coffees in which the sugars have been burned taste thin, bitter, and carbony, hardly positive characteristics for espresso. If you taste an espresso with those characteristics, try a coffee from a different roasting company.

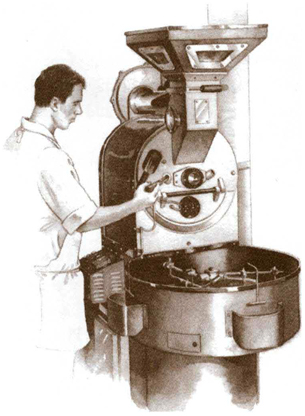

A drum roaster of the kind often used in smaller specialty coffee-roasting establishments.

The best coffee companies roast each component of a blend separately to develop what the roastmaster feels are the optimum qualities that each coffee can bring to the final blend. Consequently, many espresso blends have a mottled look. This is a sign of quality, not of carelessness, particularly when the differences in color among the beans are subtle rather than dramatic.

ROASTING YOUR OWN

After all of the preceding about how complex properly roasting an espresso coffee can be, the idea of encouraging readers to roast their own espresso coffee at home may seem as misplaced as encouraging someone to climb mountains after showing them a film of the doomed Everest expedition.

However, roasting small batches of coffee at home is much easier than roasting very large quantities of coffee in very large, industrial machines. Think of the difference between cooking for yourself and managing the kitchen for a large restaurant. The small scale of home roasting makes everything much easier. In fact, home coffee roasting probably ranks somewhere between cooking pasta al dente and poaching eggs in order of culinary difficulty.

Home coffee roasting provides the espresso aficionado with several advantages: definitively fresher coffee, less expensive coffee, and above all the opportunity to make unlimited personal experiments with roast and blend.

There are many ways to roast coffee at home. I outline most of them in my book Home Coffee Roasting: Romance & Revival, St. Martin’s Press. But for the novice, the easiest way to start is to buy a small home coffee roaster that works on the fluid-bed principle: the beans are simultaneously heated and agitated by a column of hot air jetting up through the roasting chamber, much like small electric popcorn poppers heat and agitate popping corn.

At this writing three such devices are on the market: the Fresh Roast Coffee Bean Roaster, the Hearthware Precision Coffee Roaster, and the Hearthware Gourmet Coffee Roaster. They retail for $100 to $140. All are simple to use, although they roast a relatively small volume of beans per session. All incorporate a glass roasting chamber, enabling you to observe the changing color of the beans; a chaff collector at the top or back of the roasting chamber to prevent the brown flakes that roasting liberates from coffee beans from blowing around the kitchen; and an adjustable timer, which controls the length of the roast by automatically triggering a cooling cycle. The controls for all three roasters also allow the user to manually override the timer to fine-tune the darkness of the roast, an essential feature.

The only trick with these devices is to learn when to stop the roast to get the darkness of roast and hence the taste you prefer. The longer the green beans roast, the darker the color and the deeper and less bright the taste. Because batches of green coffee beans differ from one another in density and moisture content, it is impossible for the manufacturers (or for me) to specify an exact setting or number of minutes to roast for espresso. Start with the “Dark” setting, taste the result, and fine-tune the setting from there for subsequent batches. With most coffees, there is an optimum moment when the rich bittersweetness that we treasure in espresso peaks, after which the flavor becomes progressively thinner and more burned tasting. This moment comes typically when the beans reach a dark brown, the brown that in furniture stains is called “walnut,” and when the roasting smoke smells sweet and full.

The best starting point for fine-tuning the degree of roast is to put a handful of beans roasted to the color you prefer for espresso on the counter next to the machine, start the roast at the maximum dark setting, watch the raw beans through the glass as they gradually roast until they are just slightly lighter than your sample beans, then manually override the cooling cycle by advancing the timing dial or by pushing the appropriate button.

With some particularly dense or moist beans you may need to turn the timing dial back to prolong the roast so as to achieve the darkness of roast you favor. One of the three currently available fluid-bed devices, the Fresh Roast, has a switch that slightly increases the heat in the roasting chamber to facilitate achieving darker roasts. When using the Fresh Roast for espresso, start your roasting experiments by placing this switch on the “Dark” setting.

Once you have determined the right length of time to roast a given batch of beans to the style you prefer, you should be able to set the timer and walk away. However, every time you buy a new batch of green beans you probably will need to hover over the roaster once again to determine the appropriate setting. Decaffeinated beans, which start out brown and may roast very quickly, require particularly careful attention.

All home roasting machines come with order forms for green beans. There also are sites on the Internet through which you can order green beans, including very exotic origins. See Sources.

As I indicated earlier, the most careful of espresso roasters roasts each component of a blend separately to best bring out its unique contribution to the total effect of the combined coffees, but for home roasting you may wish to combine the coffees of your blend before roasting. Freshly roasted coffee is at its best if it is allowed to rest for about twenty-four hours after roasting, permitting the recently volatilized oils to stabilize. If you’re impatient or needy, however, grind immediately and enjoy.

Common appliances of the nineteenth century: home coffee roasters designed to fit inside the burner of coal or wood stoves.

Final Precautions

Coffee roasting produces smoke. This smoke presents two problems: it can set off smoke alarms if not ventilated, and however pleasant it smells during roasting, it clings and becomes cloying over the long run. Always set up your home roasting machine under the hood of your range and turn on the fan. In clement weather you can roast out of doors on porch or patio.

A second precaution: always use exactly the volume of beans recommended by the manufacturer of your roasting device. Too many or too few beans may not agitate properly and may roast unevenly.

See the following Espresso Break for more on roasting, and Chapters 5 and 6 for more on choosing and blending beans for espresso.

ESPRESSO BREAK

ROAST NAMES AND TASTES

Attaching names to coffee roasts is one of those exercises in communication that are as futile as they are inevitable. Exactly at what point does a drizzle become rain? When does light French roast become Italian roast? One roaster’s terminology may be totally different from another’s, and in an absolute sense, there are as many shades and nuances of roast as there are batches of coffee that emerge from a roasting machine.

Given that pessimistic introduction, I here present most of the names used in the United States to describe styles of roast, arranged so as to roughly correspond to descriptions of the appearance of the beans and associated taste characteristics. Some names appear in more than one category. Such overlap is necessary because one roaster’s French may be another one’s Italian. Starbucks has contributed to the confusion by assigning its own publicist-invented names to roast styles. In Starbucks-speak the medium-brown category is Milder Dimensions, the medium-dark is Lively Impressions, the moderately dark is Rich Traditions, and the dark Bold Expressions.

The highlighted categories all describe roasts suitable for espresso. Choosing from among them is a matter of personal taste. Roasts that are too light for espresso (light brown through medium brown) produce espresso that tastes sharp and shallow; roasts that are too dark (very dark brown) produce a cup that is burned and thin. In general, tall, milky drinks require a darker, more pungent-tasting roast to carry flavor through the milk. Straight espresso, on the other hand, is best produced from blends of naturally sweet beans brought to a relatively moderate roast (medium-dark brown).

Also be reminded that the taste of a roast is influenced by the origin or blend of the green beans subject to the roasting (see Chapters 5 and 6), and by the method and handling of the roast.